ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCHES AND STUDIES (ARS)

The romanian journal anthropological researches and studies (issn 2360-3445; issn-l 2360-3445) is an annual journal and publishes:.

- fundamental and applied research, clinical field research;

- reviews and updates;

- case reports;

- information on scientific meetings.

- bio-medical anthropology: auxology, behavioral ecology, epidemiology, nutrition, physical activity, sport , sexual-reproductive health, population biology, psychology, psychiatry, etc.

- socio-cultural anthropology: topics based on the behavioral categories (economic, political, linguistic etc.), on human relations (gender, family, nation, etc.), on values (ethical, aesthetic, philosophical, religious, etc.), as well as on methodology.

Priority will be given to articles that explore medical topics, or highlight aspects related to human physical and mental health. ARS encourages its contributors to emphasize the impact that the main topic presented in their papers could have on physical and mental health at individual and/or social scale.

Keywords: bio-medical anthropology, socio-cultural anthropology, medicine, psychology, sociology.

How to submit

Follow the Authors Guidlines and then send to one of these addresses:

Andreea-Cătălina FORȚU, cultural anthropology, sociology, qualitative research methods, psychology, e-mail: [email protected]

Maria-Miana DINA, biomedical anthropology, medicine, psychology, e-mail: [email protected]

Flavia-Elena CIURBEA, biomedical anthropology, medicine, psychology, e-mail: [email protected]

Cristina-Ana STAN, biomedical anthropology, medicine, psychology, e-mail: [email protected]

2012 - 2015

- No. 1, 2012 (Abstracts)

- No. 3, 2014 (Abstracts)

- No. 4, 2014

- No. 5, 2015 (Abstracts)

- No. 5, 2015

- No. 6, 2016

- No. 7, 2017

- No. 8, 2018

- No. 9, 2019

- No. 10, 2020

- No. 11, 2021

- No. 12, 2022

- No. 13, 2023

- No. 14, 2024

- No. 15, 2025

- Call for Papers

This is an open access journal

As a result of its commitment to the aim of promoting the broadest dissemination of scientific information to the largest audience, the ARS Journal opted for an Open Access policy, allowing interested readers to easily and freely access the latest anthropological research findings and also giving the authors the opportunity to raise their visibility by multiplying the standard distribution channels. Not only that the journal is indexed in a multitude of free access bibliographic databases, but the authors themselves are free to post a copy of their final papers on their personal website or institutional repository.

Starting with 2024 in order to maintain free open access, long-term archiving and indexing (such as DOAJ, Crossref), a publishing fee of 100 euros/paper will be requested upon final acceptance following the review process. See section Evaluation Phases, at the end.

As a condition for publishing the articles, all authors of the accepted papers will be required to sign a CC BY-NC License Agreement in accordance with the ‘Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial License CC BY-NC’. For further information, see AUTHORS GUIDELINES .

Starting in 2016, Anthropological Researches and Studies has been committed for preservation in the Portico archive. Portico is a community-supported, not-for-profit digital preservation service committed to ensuring that scholarly content published in electronic form remains accessible for the long term.

The ARS journal subscribes to the principles and international standards for editors, reviewers, and authors of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). In order to protect the dignity, rights, and welfare of all research participants, it also adheres to the ethical values, norms, and procedures for biological and medical research with human beings as stipulated by the Declaration of Helsinki, the Oviedo Convention, etc…

- bio-medical anthropology: auxology, behavioral ecology, epidemiology, nutrition, physical activity, sport , sexual-reproductive health, population biology, psychology, psychiatry, etc.

Priority will be given to articles that explore medical topics, or highlight aspects related to human physical and mental health. ARS encourages its contributors to emphasize the impact that the main topic presented in their papers could have on physical and mental health at individual and/or social scale.

Keywords: bio-medical anthropology, socio-cultural anthropology, medicine, psychology, sociology.

Follow the Authors Guidelines and then submit your manuscript using the form on this page:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Anthropology articles from across Nature Portfolio

Anthropology is the study of humans, their close relatives and their cultural environment. Subfields of anthropology deal with hominin evolution and the comparative study of extant and past cultures.

Humans have evolved to digest starch more easily since the advent of farming

The region of the human genome that harbours genes encoding amylase enzymes, which are crucial for starch digestion, shows extensive structural diversity. Amylase genes have been duplicated and deleted several times in human history, and structures that contain duplicated versions of the genes were favoured by natural selection after the advent of agriculture.

Ancient equine genomes reveal dawn of horse domestication

An analysis of ancient genomes reveals an explosive geographical and demographic spread of modern domestic horses about 4,200 years ago. The findings counter the idea that horses accompanied and mobilized the mass migration of humans from the Eurasian steppes about 5,000 years ago.

Spatial bias in the fossil record affects understanding of human evolution

Using modern mammals as analogues, we investigate how spatial bias in the early human fossil record probably influences understanding of human evolution. Our results suggest that the environmental and fossil records from palaeoanthropological hotspots are probably missing aspects of environmental and anatomical variation.

Related Subjects

- Archaeology

- Biological anthropology

- Social anthropology

Latest Research and Reviews

Chronometric data and stratigraphic evidence support discontinuity between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens in the Italian Peninsula

Here, the authors present 74 radiocarbon and 31 luminescence age determinations from four sites in southern Italy. They use these data to suggest that Neanderthal disappearance in the region predated the appearance of early modern humans, a previously unclear chronology

- Marine Frouin

- Francesco Boschin

Unveiling the female experience through adult mortality and survivorship in Milan over the last 2000 years

- Lucie Biehler-Gomez

- Samantha Yaussy

- Cristina Cattaneo

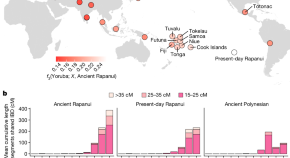

Ancient Rapanui genomes reveal resilience and pre-European contact with the Americas

An analysis of 15 ancient genomes from individuals dating to AD 1670–1950 from Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) addresses questions about the population history of the island.

- J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar

- Bárbara Sousa da Mota

- Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas

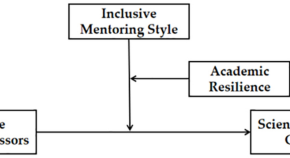

Three-way interaction effect of hindrance research stressors, inclusive mentoring style, and academic resilience on research creativity among doctoral students from China

- Chunlei Liu

- Xiaoqing Gao

Infrastructure and the evolution of settlement space: a study from a spatial anthropological perspective on the Pearl River Delta

- Jianqiang Yin

- Jingzhao Feng

An open dataset for oracle bone character recognition and decipherment

- Pengjie Wang

- Kaile Zhang

- Yuliang Liu

News and Comment

Underwater bridge gives clues to ancient human arrival

Dating mineral deposits in a flooded cave reveals that humans reached Mallorca over 5,000 years ago.

A wise doorman’s hidden treasures

- Tilmann Heil

Tropical archaeology expands the urban frame of reference

Urban archaeology in the humid tropics advances a new and diversified ontology of urban spatial forms, functions and processes that enriches and expands the frame of reference for what cities were in the past, what they are in the present and what they can be in the future.

- Christian Isendahl

- Vernon L. Scarborough

Covert racism in AI chatbots, precise Stone Age engineering, and the science of paper cuts

We round up some recent stories from the Nature Briefing .

- Benjamin Thompson

- Elizabeth Gibney

- Emily Bates

Stone Age builders had engineering savvy, finds study of 6,000-year-old monument

A survey of the Dolmen of Menga suggests that the stone tomb’s Neolithic builders had an understanding of science.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Anthropology and research methodology.

- Graciela Batallán Graciela Batallán Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA)

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.354

- Published online: 30 September 2019

This article provides a reflection on “qualitative” research methodology and their study within the university and other educational levels and invites dialogue between paradigms and currents of thought that are identified with teaching and the methods of producing empirical information. From a critical perspective, together with the positivism of the social sciences, it argues that the node of this teaching is the process of constructing the object of study, a process that confirms the centrality of the researcher.

In accordance with a theoretical-methodological focus that distinguishes the specificity of the object of the social sciences in its linguistic construction, and considering the capacity for agency of the temporarily situated actors, the researcher (also a social agent), in addition to taking on the scope and historicity of the concepts used to problematize the relationships being investigated, needs to analyze the reflexivity of his/her language, which is inscribed in the assumptions that guide his/her inquiry. In this way, research training embodies a pedagogical problematic, whereby addressing the aforementioned centrality of the construction of the object goes hand in hand with the pedagogical problematization of everyday speech.

Research-in-action training constitutes the future researcher as a critical intellectual, in search of a reliable (or true) knowledge that will incorporate him/her into the scientific framework.

- qualitative methods

- ethnographic historical focus

- the centrality of the researcher/objectivity

- critical pedagogy

A version of this article is available in its original language.

The methodological debate, circumscribed to the question of methods within the social sciences, has put the focus on the confrontation between quantitative and qualitative methods. Between this contrasting pair, the first naturally monopolize almost all of the established scientific criteria, such as generalization and objectivity, derived from the positivist paradigm. The second, qualitative methods, while also tacitly adhering to the same paradigm, are pushed to the back and considered to be exploratory or heuristic stages within research processes, and they are granted less legitimacy within institutionalized instances of university training and other educational contexts. In fact, the positivist paradigm, still widely used, grants scientific legitimacy to the statistical samples associated with quantitative methodological approaches, despite the fact that the positivist paradigm and the hypothetical-deductive research framework that facilitates quantitative research have been widely debunked within theoretical-epistemological debates.

Meanwhile, the enunciation of qualitative methods generally identifies the methodological approach with techniques of “gathering” information used in fieldwork, without referencing its epistemological foundations. In this sense we can say that the dichotomy between quantitative and qualitative methods does not generate a robust discussion, and in fact results in minimal recognition of, even devalues, the intellectual production generated by qualitative methods.

With the goal of consolidating reflections on the field of knowledge production within social sciences and social science education, this article works to relocate the axis of analysis from methods or technical-methodological approaches to the construction of the research object by explaining the ways in which the different elements that constitute the research object are linked. In this way, this article accounts for the internal articulations between the (ontological, conceptual, and epistemological) dimensions that intervene in methodological research approaches.

The body of the article is divided into two parts: the first addresses the general ways in which qualitative methods are framed, bearing in mind that teaching qualitative research grew out of documentarian training, that is to say, producers of primary sources, social agents who give meaning to social action, based on the first theoretical/conceptual tradition of anthropology, particularly participant observation (PO) as its characteristic approach. This section also addresses central points of debate and rupture within anthropology as a discipline and other social sciences.

In the second part, I organize the characteristics of the historical-ethnographic approach for empirical research and teaching, with the goal of generating an alternative to the traditional position. Additionally, I broaden the theoretical-epistemological references with the contributions of more contemporary social science research, with particular emphasis on Latin American contributions to this field of specialization.

Qualitative Research Methods and Scientific Criteria

As a first step, it is necessary to explain that research methodology is a specialist area within social sciences, tied to the production of knowledge. In general terms, the research creates and/or disputes the theory, generating—together with its growth and revision—a contribution to the social debate in question. It is a critical activity as it unmasks the static appearance of the given by providing elements for the analysis and explanation of relevant social problems.

As is the case for all specializations, research methodology is imbricated in the power dynamics of a field within the scientific community, which operates in the present, with institutionally manufactured knowledge. In this way, “the community” is cultivated through pressures and resistances that foster controversy through the hegemony of different approaches. The scientific criteria of the research, which are at the center of the debate, demonstrate, explicitly or implicitly, the ways in which new knowledges must account for its arguments and if these new knowledges are legitimated within a specific disciplinary tradition or if they are at odds with it.

In this sense, science as an institution demands that its members make explicit the scientific criteria (the scientific ideal) that they employ in their research, that they express this within the knowledge they accumulate and that they present it in their theoretical positioning, as well as in their justification for their chosen methodologies on which their empirical research weaves its arguments.

Within these criteria, research must answer to the axiom of objectivity, which—even when called into question—takes for granted that new knowledge production is “real,” “truthful,” or “trustworthy,” in contrast to manifestos of denunciation or fictional essays or literature.

The definition of qualitative methods is consubstantial with the centrality of the researcher in the production of information (the data); thus, the scientific criteria cannot be grounded in approaches or methods (which are necessarily influenced by this centrality), but, rather, should correspond to the analysis of the phenomena being studied. In the common sense of science, this displacement grants qualitative methods a sort of “little brother” status in the field of empirical research within the social sciences. The faith invested in the standardized instruments of quantitative approaches (which enable the illusion of statistical generalizations on a macro-social level) is detached from the qualitative approaches, which are stigmatized for lacking objectivity and whose neutrality is compromised as a result of the inevitable subjectivity of the researcher.

This unresolvable question is transferred to the teaching of social science research methodologies, and the relevant materials are divided between subjects that teach quantitative methods (generally Methodology A) and subjects that teach qualitative methods (generally Methodology B). However, teaching qualitative methods (because they are directly anchored in the world of experience) require that students be trained as field researchers, which is to say, as producers of primary sources or first-hand documents. Through this process (documenting the meaning given to the action of the research subjects), this teaching is necessarily concerned with the reliable production of information and the rigor with which principles and rules in relation to ethics are adopted. Examples of the latter include respect for the textuality and the expressions and voices documented, and a lack of coercion or affective, emotional manipulation of interview subjects.

This demonstrates that within its formative goal—beyond the ethical/moral dimension of the documentarian’s role—a safeguard for objectivity is present within the documentation, that is to say, processes that ensure the document is authentic and impartial with respect to the perspective, judgement, or emotion of the researcher are in place. This precaution corresponds to the field of scientific production, in its work to produce documents that are considered scientific. Even within currents of methodological anarchy (Feyerabend, 1974 ) or postmodern skepticism regarding the existence of criteria to determine truth, this issue remains relevant within the scientific community, within which—eventually—it is debated.

These findings reinforce the outlined perspective: scientific criteria are (or should be) determined in accordance with their object of knowledge that, of course, will be different between the social sciences and the physical-natural sciences, adopted as the parameters that determine “science.” Nevertheless, the positivist canon of unified science naturally invites arguments about the scientific nature of qualitative research, especially in the culturalist tradition of anthropology.

PO in the Origin of Qualitative Methods

PO within anthropology is, without a doubt, the principal antecedent to qualitative research methodologies. Its development and consolidation established ethnography as a method associated with fieldwork carried out in order to study communities without a written language (outside of civilization), which were an object of scientific interest during the colonial expansion of the countries of Central Europe at the beginning of the 20th century . The term itself, ethnography, also refers to the descriptive literary genre that was the hallmark of the first disciplinary tradition.

It’s important to point out that the study of “other cultures” and the methods associated with this endeavor arose amid the clamor of the debate between the development of functionalist theory and hegemonic evolutionism, a strong force within the science field (Stocking, 1993 ). Although other precedents already existed, Bronislaw Malinowski ( 1884–1942 ) is credited with the systematization of fieldwork as a method for his research on the preliterate communities that used simple technologies in Melanesia (Malinowski, 1986 ).

His meticulous description of their ways of life worked to refute arguments about the inferiority attributed to these peoples. The work of ethnographic documentation of the period was concerned with demonstrating the logic (rationality) of these peoples, or other ways of life with similar diverse worldviews, such as that within countries whose economic and political organization were referred to as currently primitive .

The methodological approach of fieldwork and an assumption of otherness in its research subjects defined anthropology’s identity as a discipline within the social sciences, at the same time that the field’s arguments, based in empirical research, contributed to the breakdown in the belief in normalcy, represented by Western civilization as the highest stage for the development of humanity.

The complexity of the organization of primitive cultures documented in primary sources, and the documented evidence of their particular rationality, legitimated the existence of human diversity (cultural relativism), which centers the moral-ethical dimension of the debate and anti-racist positions. The strength of these arguments, documented by empirical, anthropological research, led to their adoption within the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The specificity of the object of ethnographic research in the classical period, the ethos (the valued traditions) of the preliterate communities, was used in order to document the subject’s language in situ, their routines, the emphasis placed on interaction: “the imponderables of real life” (Malinowski, 1986 , p. 37) and “the vitality of the act” (Malinowski, 1986 , p. 40). In this way, the interpretation and analysis of ways of life adopt the hermeneutic tradition for the study of the social phenomena present in the work of Wilhelm Dilthey ( 1833–1911 ), which argues—in its characterization of the Sciences of the Spirit—that the specificity of the historical-cultural phenomena is the meaning that those that live it, give it (Dilthey, 1949 ). This axiom establishes the foundation of fieldwork as a research method. To understand language is to understand the codes of behavior that inform it (culture). The researcher documents what is said and what is done in context, translating the interpretation of the natives in order to make it understandable to readers, scientists of the Western world. Their labor is that of interpreter and translator for a culture designated as an “other.” From the point of view of functionalist theory that informs the fieldwork canon, the so-called native point of view refers to a shared cultural framework.

The journey of the researcher to exotic worlds, their long-term stay in the place (the field), and the emotional work of making the strange familiar through empathy, lays the foundations of the functionalist methodological canon, in which PO is the favored approach. Even so, as its name suggests, participant observation is simultaneously a convergence and a contradiction between paradigms. The comprehensive approach generated by the participation of the researcher in the social world in which he is immersed works to establish communication free of constraints, built on trust, with the goal of documenting and contextualizing the meaning given to speech and gestures by the peoples studied. In turn, observation of “the fixed and immutable” (which responds to the split between structure and meaning) maintains positivist science’s pretension of objectivity. In this methodological approach, external observation acts as a permanent contrast to the understanding of meaning, obtained through the participation/interlocution of the researcher with the agents (Batallán & García, 1992 ).

PO, as a general framework that encompasses several different techniques (open interviews, genealogies, biographies, etc.), managed, during the first years of the discipline’s development, to be legitimized by the scientific community by incorporating the anthropologist as a scientifically supported witness. In the first ethnologies’ insistence on objectivity, the first-person testimony of the researcher/author functioned as a safeguard for the scientificity of anthropological knowledge. The strong criticism of fieldwork as a myth, initiated within the discipline, paid special attention to ethnographic descriptions and rhetoric. Ironically, Clifford Geertz ( 1989 ) noted that this was more owing to the masterful writing of anthropologists/authors than to the truth of the lives being described. Furthermore, the successful persuasion of readers was possible not only because of the literary effect of ethnography as a genre, but also because the scientific assessment itself produced in the readers a meta-recognition that made the field researcher a legitimate and indisputable authority (Batallán, 1995 ).

From this critique until the present day, the methodological problem thus described still exists, now that the qualitative (ethnographic) methods cannot respond to the positivist model which demands distance between the researcher and the subjects that constitute the relationships being studied. It is interesting to note that the same thing did not happen with quantitative methods, despite that fact that they did also not fully comply with scientific criteria. While it is assumed that qualitative instruments of measurement (questionnaires, surveys, etc.) avoid the subjectivity of the researcher, authors such as Aaron Cicourel ( 1982 ) demonstrate that these guarantee valid results through the extension of the results, but do not guarantee the reliability of the information, given that—being predetermined questions with mostly closed answers—the answers obtained violate this criteria, which is consubstantial with open communication. Nevertheless, its prevalence overcomes its non-compliance as a criteria for scientificity.

The interest in qualitative methods, the in-depth, intensive knowledge that these methods enable in relation to the specificity of social phenomena, are recognized and recommended for specific case studies, or studies of small, specific worlds. In any case, within present-day industrialized societies, qualitative methods (outside the discipline of anthropology) are used in “exploratory” stages of research, which lend the research a heuristic value that, nevertheless, does not quite manage to re-establish the legitimacy that it originally had, when the objects of study were “ others ,” strange, different in terms of their language, traditions, and way of life from the central societies of European capitalism and expansion.

Empirical Research Methods and the Breakdown of the Concept of Culture

The changes produced in the content and the scope of the concept of culture, according to debates within the scientific community, are particularly important with regard to their connection to reflections on carrying out and teaching qualitative methods, because culture as a concept allows for the inclusion or the exclusion of the action of the subjects and its meaning from the analysis. Despite common-sense assumptions (scientific and social) that take for granted a consensus on culture, indiscriminate use of the term does not always accompany the theoretical changes that connect it to the methodological dimension of the research. Its uncritical use corresponds, in the same sense, to the PO as a privileged methodology, and the territorialized environment of an empirical field.

The idea of culture was identified for the first time between the 15th and 16th centuries as a concept tied to the care and cultivation of the land; it later became synonymous with human development and only in the 19th century did philosophers of the Enlightenment use it as an equivalent for civilization. This rationalist, secular definition of culture was taken up by evolutionary anthropologists of the era—modeled by Herbert Spencer ( 1820–1903 )—in order to support a model of social Darwinism with clear racist implications. At the same time that evolutionism was prominent, the Romantic movement emerged as a reaction that situated “national cultures” and their traditions as a barrier to the idea of universal progress. The “local cultures,” closely tied to the land, asserted their right to be recognized as unique peoples and communities. The German philosopher Johann Herder ( 1744–1803 ) attacked the philosophical concept of progress of the Enlightenment that culminated in a civilized European culture proposing to speak for cultures , despite the evident coexistence of diverse cultures.

The functionalist theory, in its North American initiation represented by Franz Boas ( 1858–1942 ), was rooted in German Romanticism, and expanded the critique of culture as a universal concept. The typification of the ways of life of the original peoples in the North American south are expressed through memorable holistic descriptions, such as those of the Culture and Personality School developed by his students Ruth Benedict ( 1887–1948 ) and Margaret Mead ( 1901–1978 ).

On the epistemological level, empiricist naturalism was the foundation of culturalism , which maintains that direct documentation of the ways of life documented by fieldwork will, in and of itself, supply the information necessary to justify the analysis. This current, still in force in the teaching of research methodologies, provides the concept of culture with an explanatory scope regarding social interaction.

Despite the fact that with the consolidation of European capitalist expansion, pure cultures (not contaminated by the West) ceased to exist, ethnographic studies maintained, methodologically, the validity of the territorial empirical reference as the base and/or synonym for a people or culture, and difference as an object and definition of anthropological studies in accordance with the earliest iteration of the field. The confrontation between “them” (the preliterate societies as a coherent whole) and “us” (Western society and its conception of a unified science) was sustained by the holistic conceptualization of culture on the theoretical plane.

Gradually, the research object shifted both toward populations, communities, or groups situated at the margins of the urban centers of power, and toward the study of sectors of society that do not respond to prevailing parameters of established normalcy. Little by little, the movement toward decolonization impacted North American anthropology, which worked to rid itself of the colonialist halo that was associated with the discipline until the mid- 20th century . Despite these changes, the pattern shaped by the culture-observation participant-field trilogy only recently began to break down owing to the effects that the so-called linguistic turn , reactivated by philosophy, produced more generally within the social sciences (Austin, 1982 ; Gadamer, 1988 ; Ricoeur, 1984 ; Winch, 1971 ; Wittgestein, 1988 ). A key text that illustrates this reconfiguration is Thick Description by Clifford Geertz ( 1987 ), in which the author establishes, for the first time, a critical relationship between revisions to the concept of culture and the methodology of fieldwork.

His argument points out that culture is not a coherent pattern, nor is it overdetermined by behaviors. Rather, he presents culture as a public code (an active document), which can only be understood and analyzed through social interaction, in which “the flow of behaviors find meaning” (Geertz, 1987 , p. 32). This perspective limits observation as a method for studying symbolic phenomena, as it is only possible to understand (interpret) the meaning of symbolic phenomena through dialogue and conversation. In this way, he laid the groundwork for future critiques of the canon, that his students would develop throughout the 1980s. Geertz would say—with respect to the connection between this idea and territoriality—that “there are no typical villages” and that “the object of study, is not the place of story,” and “we don’t study villages, rather, we study in villages” (Geertz, 1987 , p. 33). Taking up Gilbert Ryle’s term, thick description , he characterizes ethnography, employing the same example of the wink that Ryle employs, by demonstrating that we can only know what a gesture means if we are in dialogue with those who share its meaning. Drawing from semiotics, he outlines a critique of knowledge, with a nod to the culturalist tradition, in order to argue that “we do not try to become natives ourselves” (Geertz, 1987 , p. 27) but rather to communicate with them . Methodologically speaking, he emphasizes the role of the researcher as the interpreter of social interactions, recognizing through Hans-Georg Gadamer ( 1988 ), that we bring to the research object our own preconceptions and pre-understanding, and that we undergo the process of understanding through “inferences and implications” (Geertz, 1987 , p. 22).

The argument that Geertz used regarding culture as a concept is close to Weber’s theory of action, in that it presents culture as being formed by significant overlapping structures that respond to the informal logics of real life: “man lives within networks that he himself has woven” (Geertz, 1987 , p. 20). The methodological derivative of this idea works to document these actions in social settings, which are the specific contexts of the research processes.

Despite the breakdown in the definition of culture that this reflection produced—owing to Durkheimian thinking—, culture being formerly understood as an unalterable entity, it was not enough to argue for the capacity for agency in research subjects, given that the perspective of the actor was subordinated within the cultural framework. This persistence is derived from the functionalist rationality that reasons that while the actors are interpreters, they act as such within their culture, which they acquired through processes of socialization (enculturation), together with the language in which that culture is already expressed (Batallán & García, 1992 ).

While essentialist theories of culture have receded within the academic environment together with the systemic perspective of functionalism, the limitations of this theory reappear in the ethnographic writings of the same author Geertz and also in some Marxist critiques of the field. The weight of the explanatory theory of culture and its holistic, integral effect on social groups, endures, for example, in its routine use within educational research when scholars talk about school cultures, youth culture, or even the greater or lesser cultural capital of students as determining factors of their habitus, as suggested by the works of Pierre Bourdieu (Batallán, 2007 ). This explanatory scope attributed to the theory of culture—while contradicting the general theoretical bodies in which it is employed—is reinforced by the tautological reasoning of its content, which masks social action and its heterogeneity, thus enabling an analysis of social conflict limited to “culture clash.”

As we will see in the section “ The Historical-Ethnographic Focus of Research and Teaching ,” the recognition of the turning point produced by critiques of traditional theories of culture and the subsequent contributions these made to the idea of the field and other rules of fieldwork some of the representatives of the movement referred to as postmodernism in the United States (Clifford, 1991 , 1995 ; Marcus & Fisher, 2000 ; Rosaldo, 1991 ), enabled the development of a new research focus, based on reflections first carried out by the anthropologist Elsie Rockwell ( 1980 ) in a study of educational processes in Mexico. This approach, which synthesized aspects of Gramscian Marxism and structuralist revision in the same theoretical body (Heller, 1976 ; Samuels, 1984 ; Thompson, 1981 ; Williams, 1981 ; Willis, 1985 , 1988 ), recovered fruitful aspects of traditional fieldwork and Geertzian contributions, in an effort to displace functionalist hegemony in Latin American anthropological research, especially in the educational field.

The Historical-Ethnographic Focus of Research and Teaching

Returning to the goals outlined in at the beginning of this article—the work of shifting the focus from a debate over methods (approaches) to an analysis of the construction of the research object—the historical-ethnographic approach departs from functionalism and other iterations of positivism, joining current schools of thought that are developing a social science that is relational, reflective, critical, and emancipatory (Corcuff, 1998 ; Giddens, 1987 ; Rancière, 2012 ).

Since the late 1980s, this focus has grown in precision and complexity, having been debated and corroborated within working groups, congress symposiums, conferences, and academic meetings, all oriented toward methodological issues within social sciences and education, both in university environments and in teacher-training institutions in Argentina and in other Latin American countries (Batallán, 1998 ). 1 From its beginning to the present day, with more or less emphasis, the historical expansion and nuancing of the sociopolitical processes at work within educational contexts have been incorporated as the explanatory dimensions of these processes.

The introduction of ethnography into educational research was a response to ignorance regarding the everyday routines and conditions within schools, beyond what had traditionally been researched by the educational sciences, which focused primarily on teaching and learning. Ethnographic research in this area specialized in documenting the “undocumented” through: (a) intensive fieldwork with prolonged residence within the community being studied; (b) a critique of empiricism based on the theoretical construction of the research within the field; and (c) the importance, on a methodological level, of the centrality of the researcher in the production of knowledge (Rockwell, 1986 ). The theory of everyday life, which guides the focus and understands everyday life as a moment of general social reproduction, changed the functionalist perspective that conceived of it as made up of routine, non-incidental practices, set apart by their genericity (Heller, 1976 ). This theoretical-conceptual synthesis is added to critiques of theories of culture, which the Mexican anthropologist narrows and to which she adds nuances. According to Rockwell, culture as a concept is not explanatory; for her, educational ethnographic research describes “the everyday manifestations of processes of production and social reproduction, and the everyday reflection of social subjects about their world” (Rockwell, 1980 , p. 8). She adds that subjects construct their activities through consideration of their socio-temporal contexts and their lived experiences (local knowledge).

As a result of the reflections and research produced by an interdisciplinary team of researchers and educators, formed in the mid-1980s in Argentina, the approach has acquired epistemological and theoretical consistency as well as empirical research knowledge. The academic production of this team was combined with the proposal as originally outlined, while also integrating pedagogical developments used to train teachers during the previous decade in Argentina and Chile (Batallán, 1983 , 1989 , 2007 ; Vera, 1988 ; Vera & Argumedo, 1978 ). 2

The epistemological foundation of this approach was significantly influenced by the development of Anthony Giddens’s Theory of Structuration ( 1995 ). Its argumentation of structuration theory provides an adequate synthesis to sustain, along with the specificity of the social sciences, the overlap between structure and action in the analysis of social phenomena, thereby avoiding the dichotomy between explanation and understanding , which is implicit in the debate over methods and their legitimacy (García, 1994 ).

Giddens adds pragmatism, philosophy of language, symbolic interactionism, and ethnomethodology to the foundations of Marxist theory (Gadamer, 1988 ; Garfinkel, 2006 ; Schütz, 1974 ; Winch, 1971 ). His primary original contribution was a contribution to the theory of the subject in the social sciences, theorizing individual agency, or rather, considering the ability of subjects “to act differently,” and avoiding overdetermined structural analysis of social processes (Althusser, 1974 ; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1982 ). The notion of agency as an individual capability thus implies freedom and a recognition of the mediation between structure and action.

Regarding this theoretical facet, there is no division between objectivity and subjectivity (according to the prior distinction between structure or individual action), as agents “make things happen” through interaction, in a dialectic in which the structure is present within the conditions given by the action, although it is permanently changed by the undesired effects of the action.

At the methodological level, and given the linguistic construction of social life, analysis of empirical research accounts for the fact that social phenomena are symbolically pre-structured. For this reason, the path to their understanding must consider the tension that exists between analytical categories of science (derived from the theories, concepts, and the debates they generate) that the researcher brings to the process, as well as the categories of interpretation that the agents bring to these phenomena. To this logic, which Giddens referred to as double hermeneutics , is added the reflection that, although the agents are interpreters of their own world, they are still subjective interpreters of action (Batallán & García, 1988 ). In this way, such an approach corroborates the heterogeneity of social life, as opposed to the integrative perspective derived from a holistic theorization of culture.

The Centrality of the Researcher and the Performativity of Language

The epistemological foundation, regarding the performativity of language in social life, makes it possible to revise the axiom concerned with the centrality of the researcher emphasized within the earliest traditions of fieldwork. Within the new framework, it acquires a dimension that transcends the physical presence of the researcher in the place (the field). From this perspective, the aforementioned connection between the dimensions that constitute the approach is evident, because the centrality of the researcher ceases to refer to his or her psychological condition (testimonial) and is instead understood as part of the problem under study.

Theories addressing the recursive nature of language generate reflection during the pedagogical process of teaching research methodologies, therein allowing us to analyze the social roots of common speech as expressed through the prejudices (productive or unproductive) that are necessarily activated in the cognitive activity of confronting that which we desire to know. The student, at the same time, inherits interpretations and evaluations of long-established practices from institutions. For this reason, he/she must—as a future social scientist—recognize the reflexive effect of his/her language. This goes hand in hand with learning to utilize conceptual tools in order to acquire specific knowledge about the relationships being studied, with the goal of producing knowledge that aspires to be true, or at least reliable and verified.

Pedagogical accompaniment is a specific technique for teaching this methodological-theoretical approach. The advantage of this approach is that it gives the researcher’s trainee the opportunity to change his/her initial perspective by recognizing the tensions and the contrast between the interpretations of the subjects that embody the relationships under study.

The reflexivity of the researchers’ language (or its performative effect) (Austin, 1982 ; Garfinkel, 2006 ), by way of the description that he himself makes, becomes the starting point for the permanent modification of his assumptions (or hypothesis), with respect to the relationships being studied (Gouldner, 1979 ).

The research process begins by formulating a research question. In order to formulate a research question the researcher must recognize what he does not know (Gadamer, 1988 ) and acknowledge the need to corroborate this ignorance with the outside world. As anticipated, the researcher’s assumptions guide the research questions and direct the inquiry, in a process of perpetual revision. For the researcher trainee, this task is one of problematizing epistemophilic obstacle (Pichon-Rivière, 1989 ) which is unlocked by the pedagogical modality employed, in the same formative trajectory.

The teacher-coordinators in workshop spaces (“practice” in traditional pedagogy) assist with the formulation and reworking of the questions freely generated by the students. The study of common speech and its roots is also carried out with respect to the concepts that contain the articulation of the research question/problems: the analytic categories that the researcher works with, and thus, need to be questioned (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1995 ). It is through these different exercises that the desire for knowledge is awakened within the student. The concepts, and their historicity and scope, are central to this process, as has been demonstrated through the concept of culture that we discussed in the section “ Empirical Research Methods and the Breakdown of the Concept of Culture ” and that has continued to incorporate new critiques and contributions (Benhabib, 2006 ; Crehan, 2004 ; Ortner, 1984 ; Rockwell, 2009 ).

Given that, for the historical ethnographic focus, knowing is to understand the implicit logic within social action, beyond singular behaviors and their evaluation or assessment on the part of the observer, this logic also, in order to find its explanation, needs to develop historically, taking into consideration the heterogeneity (plural perspective) and the conflict inherent in social processes. In this sense, students are able to understand that professional research is a long-term activity that does not end with the construction of the object, nor with fieldwork.

Professional development, in this way, serves a dual role: on one hand, documenting the interpretations of the agents about their social work through the understanding of keys and codes of their daily speech, translated by the researcher according to the contexts in which they were enunciated. On the other hand, it allows the researcher to broaden his perspective, to confront his prejudices and analytic categories with the informal logic of real life, which is expressed by the interpretations and knowledge of his subjects.

The specificity of knowledge of social life reveals a positivist fallacy about the division between the subject that investigates and the object (the relationships under study), thus introducing students to the complexity inherent in the search for objectivity within the social sciences. As I have already stated, the pursuit of objectivity is the tacit dividing line between the activity of the sciences (also the social sciences) and literature or fiction, and affirms the need and the importance for rigorous training for researchers within the field (ethnographers). In order to understand the scope of this search, which might seem contradictory and has generated various criticisms, it is necessary to think through the legitimacy of dialogical and co-participatory research approaches (Batallán, Dente, & Ritta, 2017 ; Mannheim & Tedlock, 1995 ).

In pedagogical monitoring, the theme of objectivity in empirical social research becomes nodal because within this process it is possible to trace, in everyday language, the influence of the idea that the necessary information (the facts) are there and can be recognized. In contrast, this strong prejudice is revised, as nothing is ever “given” (as the etymology of the term data suggests), rather, information is produced in the tension between the analytical categories of the researcher and the categories the agents see as significant.

This production of information has its correlation in the feedback from teachers regarding the ways of speaking, presenting themselves, being, and asking in the empirical field. Once again, during the review of an interview, for example, the play of the assumptions of the researcher or the distrust of the interaction makes evident in situ the understanding of the abstract concept of objectivity, guiding the students toward the construction of a fluid dialogue. Dialogical communication is not associated with the technique of the guided interview, but rather with Gadamer’s model of the conversation , in which the exchange fosters the development of meaning. As of now, pre-written questionnaires are excluded in this training.

During the course of the workshops, through the different projects and exercises, the illusion of neutral observation is unmasked in order to demonstrate that this process is never direct but in fact is always mediated by the assumptions and understandings of the observer. In group analysis about these exercises the performative force of language regarding the concept of objectivity is exposed, in the sense that it is translated into a neutral language within the description, in order to approximate a scientific observation. Of course, the persistence of this idea does not invalidate the need for rigorous training in the technique of observational documentation with descriptive goals.

In short, teaching research methodology is a constant process in which the researcher’s questions necessitate analysis of the reflexivity of his or her language, both in terms of theoretical concepts and of the everyday speech he/she shares with others. It is also teaching a craft, in that the student is a documentarian in training, a producer of primary sources of information. The gradual construction of the research object is the result of systematic inquiry tied to a theoretical-epistemological pattern, that in the case of a historical-ethnographic focus is grounded in criticisms of culture as a concept and the revision of the idea of the field as a physical place, and proposes to incorporate the theory of everyday life as knowledge of the uses and activities that mediate between the particular and specific and social relations in general.

To Conclude

- Every researcher is a potential agent of social transformation, in that the production of knowledge through research is a critical activity.

-Teaching research methodology is not simply practical instruction in fieldwork techniques, although neither is it purely abstract reflection on a philosophical level.

-Pursuing objectivity in empirical research and in the social sciences is a necessary objective, but its criteria must correspond to the ontological specificity of its object. Within this specificity, a central criterion (which is also ethical in nature) is to integrate and problematize the language of the researcher—who is also a socially and historically anchored agent—before initiating his/her work.

-The dialogical approaches and participants are points of contrast between the assumptions of the researcher and the collaborative production of knowledge; nevertheless, the researcher is always an author responsible for what he/she produces as an intellectual worker.

- The material produced in the field, when the analytical categories inscribed in the research problem and the research subjects’ categories of interpretation are compared with one another, is the basis of a pattern of interpretation and analysis that should be accompanied by studying theoretically framed, coherent, secondary documentation.

-When training students to be researchers, the purpose of critical pedagogy is that, both at the level of theoretical learning and when learning in the field, students should take ownership of the social responsibility for their intellectual authorship, as well as the indirect, but effective, impact of the results of their work within border social debate.

-The false problem inscribed in the qualitative-quantitative dichotomy, associated with the legitimacy of the knowledge produced by each approach, can only be disarticulated by shifting the axis of the debate toward the construction of the research object in the social sciences, which requires, together with permanent conceptual and linguistic reflection, dialogical criteria and participants for its support.

- Althusser, L. (1974). Ideología y aparatos ideológicos del Estado . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Nueva Visión.

- Austin, J. L. (1982). Cómo hacer cosas con palabras . Barcelona, Spain: Paidós.

- Batallán, G. (1983). Taller de educadores. Capacitación mediante la investigación. Síntesis de Fundamentos. In Serie documentos e Informes de Investigación Nº 8- . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales FLACSO/PBA.

- Batallán, G. (1989). Talleres de educadores. Capacitación por la investigación de la práctica. In Cuadernos de Formación Docente N° 5 Problemas de la investigación participante y la transformación escolar . Rosario, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

- Batallán, G. (1995). Autor y actores en antropología: Tradición y ética en el trabajo de campo. Revista de la Academia , 1 , 97–106.

- Batallán, G. (1998). La apropiación de la etnografía por la investigación educacional: Reflexiones sobre su uso reciente en Argentina y Chile. Revista del Instituto de Ciencias de la Educación , 14 , 3–11.

- Batallán, G. (2007). Docentes de Infancia: Antropología del trabajo en la escuela primaria . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós.

- Batallán, G. , Dente, L. , & Ritta, L. (2017). Anthropology, participation and the democratization of knowledge: Participatory research using video with youth living in extreme poverty. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education , 30 (5), 464–473.

- Batallán, G. , & García, J. F. (1988). Trabajo docente, democratización y conocimiento: Problemas de la investigación participante y la transformación de la escuela. Cuadernos de Formación Docente , 5 , 27–43.

- Batallán, G. , & García, J. F. (1992). Antropología y participación: Contribución al debate metodológico. Publicar en Antropología y Ciencias Sociales , 1 (1), 79–89.

- Benhabib, S. (2006). Las reivindicaciones de la cultura: Igualdad y diversidad en la era global . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Katz Ediciones.

- Bourdieu, P. , & Passeron, J. C. (1982). La reproducción: Elementos para una teoría del sistema de enseñanza . Barcelona, Spain: Laia.

- Bourdieu, P. , & Wacquant, L. (1995). Respuestas: Por una antropología reflexiva . Mexico D.F., Mexico: Grijalbo.

- Cicourel, A. (1982). El método y la medida en sociología . Madrid, Spain: Editorial Nacional.

- Clifford, J. (1991). Sobre la autoridad etnográfica. In C. Reynoso (Ed.). El surgimiento de la antropología posmoderna (pp. 141–170). México D.F., Mexico: Gedisa.

- Clifford, J. (1995). Dilemas de la cultura: Antropología, literatura y arte en la perspectiva posmoderna . Barcelona, Spain: Gedisa.

- Corcuff, P. (1998). Las nuevas sociologías: Construcciones de la realidad social . Madrid, Spain: Alianza Editorial.

- Crehan, K. (2004). Gramsci, cultura y antropología . Barcelona, Spain: Bellaterra.

- Dilthey, W. (1949). Introducción a las ciencias del espíritu . México D.F., Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Feyerabend, P. (1974). Contra el método . Barcelona, Spain: Ariel.

- Gadamer, H. G. (1988). Verdad y método . Salamanca, Spain: Sígueme.

- García, J. F. (1994). El problema de la unidad de comprender y explicar en ciencias sociales. In J. F. García , La racionalidad en política y en ciencias sociales (pp. 93–126). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Centro Editor de América Latina.

- Garfinkel, H. (2006). Estudios en etnometodología . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Anthropos.

- Geertz, C. (1987). La interpretación de las culturas . Barcelona, Spain: Gedisa.

- Geertz, C. (1989). El antropólogo como autor . Barcelona, Spain: Paidós.

- Giddens, A. (1984). Profiles and critiques in social theory . Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Giddens, A. (1987). Las nuevas reglas del método sociológico . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu.

- Giddens, A. (1995). La constitución de la sociedad: Bases para una teoría de la estructuración . Buenos Aires, Spain: Amorrortu.

- Gouldner, A. (1979). La crisis de la sociología occidental . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu.

- Heller, A. (1976). Sociología de la vida cotidiana . Madrid, Spain: Península.

- Heller, A. (1985). Historia y vida cotidiana . México D.F., Mexico: Grijalbo.

- Heller, A. , & Fehér, F. (1988). Políticas de la postmodernidad: Ensayos de crítica cultural . Barcelona, Spain: Península.

- Malinowski, B. (1986). Los argonautas del Pacifico Occidental . Barcelona, Spain: Planeta Agostini.

- Mannheim, B. , & Tedlock, D. (1995). The dialogic emergence of culture . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Marcus, G. , & Fisher, M. (2000). La antropología como crítica cultural . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu.

- Ortner, S. (1984). Theory in anthropology since the sixties. Comparative Studies in Society and History , 26 (1), 126–166.

- Pichon-Rivière, E. (1989). El proceso grupal . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Nueva Visión.

- Rancière, J. (2012). El método de la igualdad . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Nueva Visión.

- Ricoeur, P. (1984). Educación y política . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Docencia.

- Ricoeur, P. (2005). Sobre la traducción . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós.

- Rockwell, E. (1980). Antropología y participación: Problemas del concepto de cultura . México D.F., Mexico: DIE.

- Rockwell, E. (1986). La relevancia de la etnografía para la transformación de la escuela. In Memorias del Tercer Seminario Nacional de Investigaciones en Educación . Bogotá, Columbia: Centro de Investigación de la Universidad Pedagógica e Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior.

- Rockwell, E. (2009). La experiencia etnográfica: Historia y cultura en los procesos educativos . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós.

- Rosaldo, R. (1991). Cultura y verdad: Nueva propuesta de análisis social . México D.F., Mexico: Grijalbo.

- Samuels, R. (1984). Desprofesionalizar la historia. Debats , 10 , 57–71.

- Schütz, A. (1974). El problema de la realidad social . Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu.

- Stocking, G. (1993). La magia del etnógrafo: El trabajo de campo en la antropología británica desde Taylor a Malinowski. In H. Velasco Maillo , F. García Castaño , & A. Díaz de Rada (Eds.), Lecturas de antropología para educadores: El ámbito de la antropología de la educación y de la etnografía escolar (pp. 43–95). Madrid, Spain: Trotta.

- Thompson, E. (1981). Miseria de la teoría . Barcelona, Spain: Crítica.

- Vera, R. (1988). Metodología de la investigación docente: La investigación protagónica. Cuadernos PIIE. N 2, Santiago de Chile, Chile.

- Vera, R. , & Argumedo, M. (1978). Talleres de educadores como técnica de perfeccionamiento operativo con apoyo de medios de comunicación social . Cuadernos N° 2. Centro de Investigaciones Educativas (CIE), Buenos Aires.

- Williams, R. (1981). Cultura y sociología de la comunicación y del arte . Barcelona, Spain: Paidós.

- Willis, P. (1985). Notas sobre método. In Dialogando Nº 2. Cualitativas de la Realidad Escolar.

- Willis, P. (1988). Aprendiendo a trabajar . Madrid, Spain: Akal.

- Winch, P. (1971). Ciencia social y filosofía . Buenos Aires, Spain: Amorrortu.

- Wittgestein, L. (1988) Investigaciones filosóficas . México D.F., México: Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas-UNAM.

1. The creation of the Latin American Network for Qualitative Research of Real Education is noteworthy. It was formed with the support of the Canadian parliament in 1980 and with the participation of researchers from Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela, Colombia, and Uruguay, who, while living under dictatorships, or directly after recent dictatorships in their respective countries had been overthrown, participated in a first seminar in Mexico and developed further academic meetings after the initial gathering. The activity of the Network and its publication RINCUARE lasted three years, fostering the formation and development of the approach in national universities and non governmental organizations (NGOs) within the aforementioned countries.

2. The focus was a lectureship focused on “Methodology and Techniques of Field Research” in the Anthropological Science Department of the College of Philosophy and Literature at the University of Buenos Aires (1987–2013), as well as subjects/classes and seminars geared toward master’s and doctorate students at the University of Buenos Aires and elsewhere. It is also present in the research projects developed since 1994 to the present day, by the Secretariat of Scientific Research of the University of Buenos Aires (UBACyT) under my direction and the co-direction of Silvana Campanini.

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 16 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Character limit 500 /500

- This journal

Current Anthropology

Front Cover

Front matter, futurities rethought: on the political imminences of runaway nature.

- Adriana Petryna

The impacts of climate change are accelerating worldwide, but emergency agencies and political bodies are not always equipped to anticipate where, when, or how severe the next unnatural disaster will be. Amid megafire seasons, for example, scientists are revising models of fire behavior that were calibrated to natures that increasingly diverge from known baselines and trends. Emergency responders’ trust in patterns has become an occupational hazard. At these edges of knowledge, struggles to maintain responsive capacity in disrupted ecologies are at play; a larger reckoning with runaway climate change as a relational problem space is in order. Rather than making me resort to despair about the world’s “end,” such labors redirect my attention toward horizons of expectation in which knowledges are still actionable, not obsolete, and where capacities for future interventions are viable and not denied. These activities, enmeshed in a rubric of horizon work, shift expert authority and promote critical realignments across political, activist, and Indigenous spheres.

Is Mnemonics an End in Itself? Sensory Mnemonic Learning of the Qur’ān in Southwestern Morocco

- Romain Simenel

Are mnemonic devices an end in themselves as regards meaning? Do memorization techniques serve only memory, or do they have longer-term effects on other aspects of the mind? If so, what are those effects, and what is the role of the body? These are a few questions that are suggested by the ethnographic study of Qur’ān memorization in southwestern Morocco. In the Sous, a Berber region that is known throughout the Maghreb for the Sufi masters it has produced, children, from the age of five, are sent to madrasas each day, where they learn the Qur’ān “by heart.” To do so, they make use of a variety of mnemonic techniques that draw on their imagination as they are guided by the prosody of recitation. The Qur’ānic wooden tablet serves as the medium of the sensorial experience of learning the sacred text, providing the child with space for creativity and reflection. This article proposes to retrace the process of Qu’rān memorization from the recitation of the alphabet to the learning of chanting and writing the sacred text; it will highlight the effects of mnemonics on the acquisition of cultural abilities related to Sufi practices and on metamemory in a bilingual context.

Taiwanese Prehistory: Migration, Trade, and the Maritime Economic Mode

- Chin-yung Chao and

- Timothy Earle

In a previous Current Anthropology article considering the Scandinavian Bronze Age (Ling, Earle, and Kristiansen 2018 ), a model was proposed to explain the concentration of metal wealth and social stratification under conditions of low population density. This model is now considered to help understand anomalies in the archaeological sequence of eastern Taiwan during the Neolithic and Early Metal Ages. In contrast to Taiwan’s agriculturally richer western coast, evidence of complexity arose unexpectedly early on the east despite its more limited agricultural soils and lower populations. We propose that these outcomes resulted from a maritime economy, in which local agricultural surpluses finance distant voyaging that an emergent elite might control. Travels carried a substantial amount of rare nephrite from Taiwan’s eastern coast to Island Southeast Asia and the South China Sea. Subsequently, metals and glass technologies were introduced from there into Taiwan. This trade and technological transfer were earliest on the eastern coast, perhaps unexpected because it was more removed from the Chinese mainland, a likely source for cultural transfers. We propose that eastern coast Taiwanese populations developed an entrepreneurial raiding-trading political economy, perhaps involving slaves, that would explain these anomalies. Predating specialized merchant trading, a raiding-trading complex, not unlike later piracy, may have provided broadscale maritime interactions partially responsible for patterned developments of political complexity in this region of the world.

Checking Facts by a Bot: Crowdsourced Facts and Intergenerational Care in Posttruth Taiwan

- Mei-chun Lee

From the discussion of “posttruth” in 2016 to the “infodemic” in 2020, online rumors seem to have become more rampant, harmful, and harder to be debunked. This article examines Cofacts, a Taiwan-based fact-checking service that combines a chatbot and a database of fact-checked responses provided by volunteers to help debunk rumors circulated on the messaging app LINE. I argue that Cofacts’s crowdsourcing approach joins what Donna Haraway calls embodied objectivity that insists on “the particularity and embodiment of all vision” to challenge the conventional fact-checking practice that presumes singularity, disembodied objectivity, and authority. Underpinning Cofacts’s fight against online rumors is the intergenerational conflicts that are ingrained in different life experiences, beliefs and values, and expectations of what a good life is. By taking up a technological solution that emphasizes openness, Cofacts opens a space for digital natives to contest what fact is and claim the power of speaking from their parents and the patriarchal society on the one hand and to forge new connections of care and reinitiate conversations that have been barred by the invisible walls of chat rooms and the widening gap of values and beliefs between generations on the other hand.

Econography: Observing Expert Capitalism

- Daromir Rudnyckyj

In recent years anthropologists have increasingly conducted fieldwork among economic agents and on financial practices that would have seemed foreign to our predecessors of just a generation ago. This work can be broadly categorized as the analysis of expert capitalism. Expert capitalism is the knowledge-intensive, abstract, and often technical pursuit of profit. Anthropologists conducting such research have produced germinal insights regarding the contingent factors that make up expert capitalism, the key role of representations, language, and narrative in constituting the object referred to as an economy, and the unstated assumptions that frame the actions of expert capitalists. However, there have been as yet few systematic reflections regarding how to conceptualize expert capitalist fields and objects in such a way as to make them amenable to empirical, anthropological analysis. This article seeks to develop the anthropological documentation and analysis of expert capitalism by outlining a set of strategies useful in facilitating such research. These strategies fall under the rubrics of (1) mesoanalysis, (2) institutionalization, (3) reflexive practice and problematization, (4) subjectification, and (5) representations as economic facts. The article concludes that, taken together, these strategies constitute what might be termed econography: a mode of analysis suited to analysis of and writing about expert capitalism.

Tracking Mortgage Pathways in Zagreb: Everyday Economics of Debt, Housing Wealth, and Debtors’ Agency in a European Semiperiphery

- Marek Mikuš

Drawing on a case study of mortgage debt in Zagreb, Croatia, this article argues that the anthropology of household debt should engage more deeply with its economic implications and uses for debtors. It contributes novel insights from an understudied Eastern European setting to the Anglophone-centric debates on housing wealth and the financialization of subjectivity. The original mortgage pathways approach uses repeat interviews to track individual and household trajectories of mortgage debt. These processes are constituted by interactions between mortgagors and other actors, structural and conjunctural conditions, social norms, contingencies, and mortgages themselves. While mortgagors embraced the norm of housing wealth accumulation, their homeownership had layered meanings shaped by norms regulating reproduction and kinship and local structural and conjunctural conditions. At the same time, some individuals employed mortgages for profit-making strategies, and personal and public experiences with predatory lending stimulated a widespread prudent and active approach to mortgages. Thus, instead of an across-the-board financialization of subjectivity or its opposite, “domestication” of finance, there was an uneven interpenetration between the financial rationality of mortgages and mortgagors’ prudent rationality that combined instrumental reasoning and value-based goals. Mortgages entail certain intrinsic effects, but their materialization is not exempt from the variability and dynamism of debt processes.

Fit to Protect: Race, Vulnerability, and the Risk Politics of California Firefighting

- Melissa Burch

- Supplemental Material

Anthropologists have long understood that a society’s ideas about who or what is risky depend on how meaning and worth are attributed to objects, people, and processes in a given place and time. However, until recently, little consideration has been given to the ways race and other hierarchical relations of power and difference shape how risk is constructed and deployed in social life. This article explores how race and criminal status intersect to shape the perception and management of risk and vulnerability in the United States by chronicling the lived experience of one young African American man who was prevented from obtaining an emergency medical technician (EMT) license because of his felony convictions. His pursuit of the EMT license and a career in firefighting exposes how risk, as a purportedly value-neutral concept, builds on racialized ideas about threat and vulnerability and further entrenches racialized social exclusion. Whereas many have decried racism as an unfortunate by-product of actuarial practices, I argue that racism and antiblackness are among risk’s core animating logics. Challenges to risk evaluations must therefore go beyond politics of deservedness, rehabilitation, and inclusion to confront the foundational premises of risk head-on.

Thought Collectives, Fascism, and Truth: Ludwik Fleck and My Father in Buchenwald, April 11, 1945

- Sharon Kaufman

Polish physician and sociologist of science Ludwik Fleck was a prisoner in Buchenwald on April 11, 1945, the day my father, a US army physician, arrived there with the liberating troops. My father was exposed to Nazi brutality as a young Jew living in Vienna in the 1920s. Fleck was from Lvov, an epicenter of Nazi persecution. For both, a paramount question was what kind of medicine could be practiced in a world of deliberate extermination. Did they meet? My father’s late-life memoir notes that “the inmates who were physicians immediately proceeded to make use of their skills to help their fellow inmates.” That piqued my interest in how Fleck’s socioscientific insights, described in Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact , emerged from his prewar experience of Nazi terror, when his scientific work, sociological-philosophical background, and observations of the prevailing fascism coalesced. This shaped his awareness of how collective thinking—by a nation, race, party, or class—produces facts and how politics and prejudice get entangled in scientific work. This essay explores Fleck’s legacy and how both physicians offered resistance and reprisal to fascism, compelling concerns in view of today’s increasing tolerance for fascism, racism, antisemitism, and “alternative” truths.

Book and Film Reviews

Eating the last cannibal.

- Uday Yerramadasu

Of all published articles, the following were the most read within the past 12 months .

Is It Good to Cooperate?: Testing the Theory of Morality-as-Cooperation in 60 Societies

- Oliver Scott Curry ,

- Daniel Austin Mullins , and

- Harvey Whitehouse

Brain Development and Physical Aggression: How a Small Gender Difference Grows into a Violence Problem

Running in tarahumara (rarámuri) culture: persistence hunting, footracing, dancing, work, and the fallacy of the athletic savage.

- Daniel E. Lieberman ,

- Mickey Mahaffey ,

- Silvino Cubesare Quimare ,

- Nicholas B. Holowka ,

- Ian J. Wallace , and

- Aaron L. Baggish

The Potentiality Principle from Aristotle to Abortion

- Lynn M. Morgan

An Anthropology of Structural Violence

- Paul Farmer

The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution

- Leslie C. Aiello and

- Peter Wheeler

Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology: An Introduction to Supplement 20

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing ,

- Andrew S. Mathews , and

- Nils Bubandt

The Osteological Paradox: Problems of Inferring Prehistoric Health from Skeletal Samples [and Comments and Reply]

- James W. Wood ,

- George R. Milner ,

- Henry C. Harpending ,

- Kenneth M. Weiss ,

- Mark N. Cohen ,

- Leslie E. Eisenberg ,

- Dale L. Hutchinson ,

- Rimantas Jankauskas ,

- Gintautas Cesnys ,

- Gintautas Česnys ,

- M. Anne Katzenberg ,

- John R. Lukacs ,

- Janet W. McGrath ,

- Eric Abella Roth ,

- Douglas H. Ubelaker , and

- Richard G. Wilkinson

Download the E-book

Nonsubscribers: Purchase the e-book of this issue

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

Frequency: 6 issues/year ISSN: 0011-3204 E-ISSN: 1537-5382 2023 JCR Impact Factor*: 2.1 Ranked #18 out of 139 “Anthropology” journals 2023 CiteScore*: 5.6 Ranked #15 out of 502 “Anthropology” journals

Established more than sixty years ago, Current Anthropology is the leading broad-based journal in the field. It seeks to publish the best theoretical and empirical research across all subfields of the discipline, ranging from the origins of the human species to the interpretation of the complexities of modern life.

View content coverage periods and institutional full-run subscription rates for Current Anthropology .

*Journal Impact Factor™ 2023 courtesy of the Journal Citation Reports ( JCR )™ (Clarivate 2024). Scopus CiteScore (Elsevier B.V.). Retrieved June 2024 from scopus.com/sources .

- Caroline Schuster and Catherine Frieman appointed co-editors of Current Anthropology June 6, 2024

- Feathers, Cognition and Global Consumerism in Colonial Amazonia April 30, 2024

- The SAPIENS Podcast Named Finalist at the 16th Annual Shorty Awards April 24, 2024

Read the Current Anthropology article cited in Big Think

Read the Current Anthropology article cited in the Society for Linguistic Anthropology blog

Read the Current Anthropology article cited in AEON

- Utility Menu

- Internal Resources

- EDIB Committee

"Anthropology is the study of what makes us human"

- American Anthropological Association

Undergraduate Program

Graduate Program

Concentrate in anthropology.

The study of anthropology prepares students to address global concerns through a contextualized study of society, culture, and civilization, and can lead to careers in global health and medicine, law, government, museums, education, the arts, cultural and environmental management, business and entrepreneurship, among other fields, not to mention academia.

- Pursue an Undergraduate Degree

- Meet Our Undergraduate Alumni

Harvard Anthropology Professor Gabriella Coleman Discusses Evolution of Hacking on Cybercrime Magazine Podcast

Harvard Anthropology Professor Peter Manuelian Awarded NEH Grant

Harvard anthropology professor arthur kleinman shares photos of summer 2024 travels, harvard anthropology seminar series (social): danilyn rutherford, wenner-gren foundation, harvard anthropology seminar series (arch): andreana (andree) cunningham, boston university, harvard anthropology seminar series (arch): eslem ben arous, cenieh spain | marie curie postdoctoral fellow, what is anthropology.