- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2020

Case report: acute abdominal pain in a 37-year-old patient and the consequences for his family

- Elisabeth Niemeyer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1530-3720 1 ,

- Hamid Mofid 2 ,

- Carsten Zornig 3 ,

- Eike-Christian Burandt 4 ,

- Alexander Stein 1 ,

- Andreas Block 1 na1 &

- Alexander E. Volk 5 na1

BMC Gastroenterology volume 20 , Article number: 129 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2445 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is a rare condition that accounts for approximately 1–3% of all gastric cancer cases. Due to its rapid and invasive growth pattern, it is associated with a very poor prognosis. As a result, comprehensive genetic testing is imperative in patients who meet the current testing criteria in order to identify relatives at risk. This case report illustrates the substantial benefit of genetic testing in the family of a patient diagnosed with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.

Case presentation

A 37-year-old patient was admitted to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain. Following explorative laparoscopy, locally advanced diffuse gastric cancer was diagnosed. The indication for genetic testing of CDH1 was given due to the patient’s young age. A germline mutation in CDH1 was identified in the index patient. As a result, several family members underwent genetic testing. The patient’s father, brother and one aunt were identified as carriers of the familial CDH1 mutation and subsequently received gastrectomy. In both the father and the aunt, histology of the surgical specimen revealed a diffuse growing adenocarcinoma after an unremarkable preoperative gastroscopy.

Awareness and recognition of a potential hereditary diffuse gastric cancer can provide a substantial health benefit not only for the patient but especially for affected family members.

Peer Review reports

Gastric cancer is the fifth most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the third most deadly cancer in males worldwide [ 1 ]. Gastric adenocarcinoma can be classified according to Lauren’s criteria, which define two major histological subtypes: intestinal and diffuse type adenocarcinoma [ 2 ]. These two subtypes have a variety of distinct clinical and molecular pattern. While the more common intestinal type of adenocarcinoma has a stronger association with Helicobacter pylori infection and dietary risk factors, diffuse gastric cancer more often has a genetic etiology [ 3 ]. Intestinal type of gastric cancer is frequently preceded by long-standing, precancerous, ulcerous lesions and is easily detectible by gastroscopy [ 4 ]. In contrast, diffuse gastric cancer typically develops within the submucosa with small foci of signet cells dispersed throughout the tissue, often not easily detected by routine upper endoscopy and can be missed in superficial biopsies [ 5 ]. Diffuse gastric cancer is typically associated with an aggressive growth pattern and poor prognosis [ 3 ].

Germline mutations in the CDH1 gene, encoding E-cadherin, are associated with an autosomal-dominant inherited susceptibility for diffuse gastric cancer (hereditary diffuse gastric cancer/HDGC [Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®/OMIM entry #137215). Mutations in CDH1 can be identified in up to 54% of HDGC cases by sequence analysis and gene-targeted analysis for deletion and duplication [ 6 ] Although rare, other genetic causes of HDGC are still under investigation, including mutations in the CTNNA1 gene and mutations in other genes [ 7 ]. Invasion of carcinomas into surrounding tissues and their eventual metastasis requires the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Downregulation or dysfunction of E-cadherin is the hallmark event in EMT, as E-cadherin deficient cells lose their ability to adhere to each other and gain individual cell motility [ 8 ]. In the case of HDGC, E-cadherin deficiency leads to a diffuse growth pattern of cancer cells throughout the submucosa. The gastric mucosa is intact and appears normal during gastric endoscopy even in late disease [ 5 ]. Loss of expression of E-cadherin in immunohistochemistry may be an indicator for a CDH1 -associated gastric cancer. The cumulative life time risk for carriers of a pathogenic variant in CDH1 to develop gastric cancer is 70% for men and 56% for women [ 5 , 7 ]. Women carrying a CDH1 mutation also have an increased risk for breast cancer, especially lobular breast cancer (42% lifetime risk with an average age of onset of 53 years [ 6 ]). It is still unresolved whether CDH1 -mutation carriers also have an increased risk of colon cancer [ 5 ].

A 37-year-old male (Fig. 1 , III.2) was referred to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain and fever. Physical examination showed signs of an acute peritonitis and lab tests revealed elevated inflammation markers (C-reactive protein). CT-scan showed a pneumoperitoneum and an emergency exploratory laparoscopy was performed. Since the site of the perforation could not be detected by laparoscopic approach, the procedure had to be converted to an open laparotomy. A gastric perforation (2 mm in diameter) was found, excised and sutured. Unexpectedly, the surgeons noted a rigid thickened stomach wall (consistent with linitis plastica) during operation. Furthermore, a tumor mass invading the minor omentum and the mesentery was found. Intra-surgical frozen section analysis confirmed the initial suspicion and revealed diffuse growing gastric cancer with signet cells. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with a diffuse gastric cancer (pT4bN3M1).

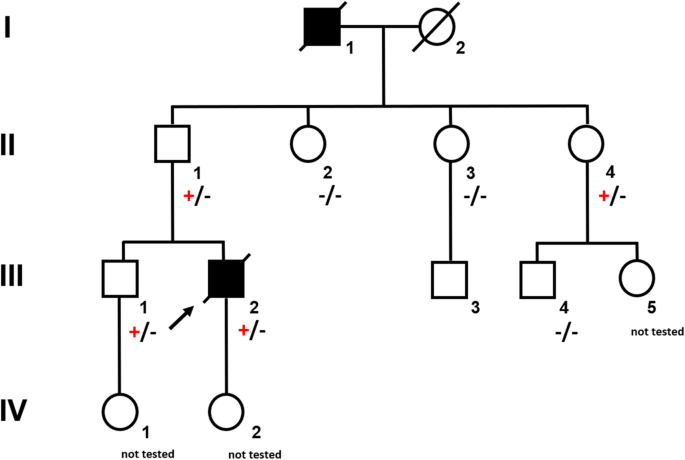

Pedigree of a large German family segregating autosomal dominant CDH1 -associated gastric cancer. Circles represent females and squares males. Filled symbols indicate clinically affected individuals and a plus sign carriers of the CDH1 mutation c.1137G > A

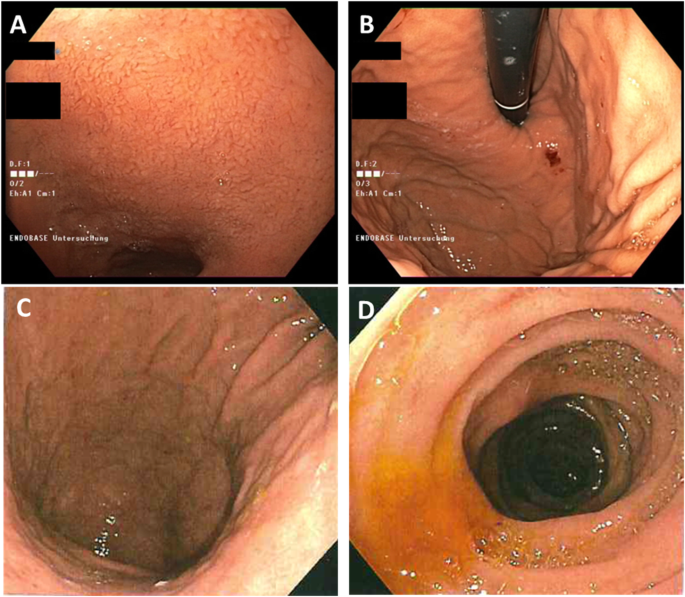

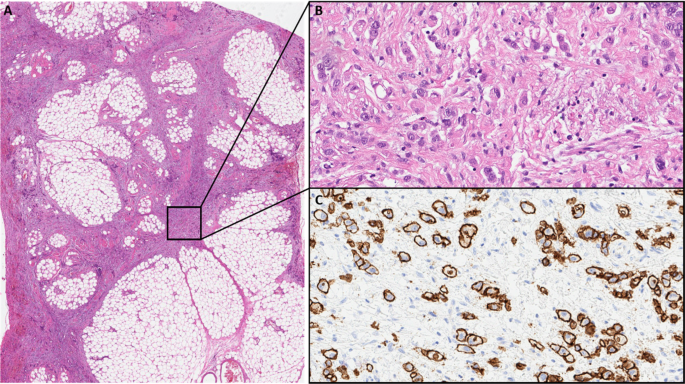

The young age at diagnosis and histological subtype prompted the surgeon to refer the patient and his family to genetic counselling. Evaluation of the family history revealed that the patient’s paternal grandfather (Fig. 1 , I.1) died of abdominal cancer at the age of 40. No other family members suffered from cancer, especially not the father (61 years old; Fig. 1 , II.1). Both the father and the healthy older brother (Fig. 1 III.1) underwent elective gastroscopies. In both patients, endoscopy showed an unremarkable mucosa (Fig. 2 c/d, data for brother not shown). Multiple random “button hole biopsies” were taken during gastroscopy and diffuse growing malignant cells could be detected in one out of three of the biopsies taken from the father. Genetic testing revealed the heterozygous germline mutation c.1137G > A of CDH1. This genetic alteration affects the last exonic nucleotide at the canonical splice donor site leading to impaired splicing and consequently to a dysfunctional E-cadherin molecule (Human Gene Mutation Database/HGMD® No. CS0060517). As this mutation has already been described in other HDGC patients, the diagnosis of HDGC in the father and also in the index patient carrying the same mutation was confirmed. Surprisingly, despite the presence of a CDH1 mutation, E-cadherin expression could still be immunohistochemically detected in tumor tissue with a monoclonal antibody raised against E-cadherin (Fig. 3 , Agilent Dako FLEX Monoclonal Mouse Anti-Human E-Cadherin, Clone NCH-38).

Endoscopic images of the paternal aunt ( a/b ) and the father ( c/d ) showing normal appearance of the gastric mucosa despite later confirmed signet cell adenocarcinoma in the submucosa

a Low power view of perigastric fat infiltrated by the gastric cancer (HE). b High power view showing diffuse growing isolated cancer cells (HE). c High power view of an E-cadherin immunohistochemistry stain with Antibody: Agilent Dako FLEX Monoclonal Mouse Anti-Human E-Cadherin, Clone NCH-38 showing strong membranous positivity of the cancer cells. With knowledge of the molecular data the E-cadherin antibody most probably detects a non-functional E-cadherin protein

With identification of a pathogenic CDH1 mutation, index patient’s healthy brother (38 years old; Fig. 1 III.1) as well as the three paternal aunts (53-, 56-, 58- years old, respectively, Fig. 1 , II.2, II.3, II.4) had an a-priori risk of 50% to also carry the CDH1 mutation. Ultimately, all four relatives underwent predictive testing after genetic counselling. While the mutation was detected in the brother and one aunt (Fig. 1 , II.4), two aunts did not inherit the mutation. As a result, his brother and his aunt underwent prophylactic gastrectomy. While no malignant cells were found in the histologic examination of the brother’s stomach, a diffuse growing adenocarcinoma was detected during histologic workup in the stomach of the aunt. Despite a macroscopically unremarkable appearance of the surgical specimen, two isolated cancer foci of signet cells located 7 mm from one another were detected in the upper third of the lamina propria of the cardiac region. Similar to the index patient’s father /herbrother, this diffuse gastric cancer was not macroscopically detectable during gastroscopy (Fig. 2 a/b) before gastrectomy was performed, not even after retrospectively analyzing the affected sites in the endoscopic images. Further staging showed no involvement of lymph nodes or distant metastasis in her case (pT1a pN0 (0/16) cM0).

The father, brother and aunt recovered well after their surgeries. Unfortunately, the condition of the index patient worsened quickly due to perioperative complications. Systemic chemotherapy could not be administered due to his poor general condition. He died 2.5 months after diagnosis.

Discussion and conclusions

Given that monogenic factors are rare and account only for 1–3% of gastric cancers, awareness among health care professionals is of utmost importance. Regardless of the family history, a personal history of a diffuse gastric cancer under the age of 40 qualifies for genetic testing of the CDH1 gene following the latest International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) consensus guidelines. Furthermore, a CDH1 mutation should be suspected if two or more family members have been diagnosed with diffuse gastric cancer at any age or in a family if two family members were diagnosed with diffuse gastric cancer or lobular breast cancer with one diagnosis before the age of 50 years (Table 1 , [ 5 ]). In our family, the young age of the index patient and the family history with abdominal cancer of the paternal grandfather lead to genetic testing and the identification of the causal CDH1 mutation in the family. With the identification of the underlying genetic defect, all family members had the chance to learn about their exact individual risks. First degree relatives of a mutation carrier have a 50% chance to inherit the mutation. Extensive genetic counseling and discussion of the clinical management is especially important when detecting a mutation by predictive testing in healthy relatives. If a family member has not inherited the mutation, he and his progeny have no increased risk to develop gastric cancer. On the other hand, if the pathogenetic mutation is detected, the individual is faced with the cancer risks previously mentioned. As diffuse gastric cancer is difficult to detect at an early and treatable stage, mutation carriers may either choose prophylactic gastroscopy or endoscopic surveillance according to the Cambridge protocol [ 9 ]. This protocol recommends targeted biopsies of any suspicious lesion in the gastric mucosa as well as a minimum of 6 random biopsies taken from each anatomic area of the stomach (antrum, transitional zone, body, fundus, cardia) and should begin 5–10 years prior to the diagnosis of the youngest family member [ 9 , 10 ]. Current recommendations suggest prophylactic gastrectomy in healthy CDH1 mutation carriers rather than endoscopic surveillance [ 5 ]. The estimated risk for diffuse gastric cancer is 1% by the age of 20 years and around 4% by the age of 30 years [ 10 ]. Therefore, most authors recommend offering a gastrectomy to CDH1 mutation carriers between ages 20 and 30 [ 5 , 10 ]. The mortality rate of gastrectomy itself is less than 1% but it has a high morbidity for nutritional, metabolic and psychological well-being. Most patients report rapid intestinal transit, reflux, dumping syndrome and diarrhea after surgery. After gastrectomy patients need life-long vitamin supplementation. In our family, all mutation carriers chose to undergo gastrectomy, and gastric cancer was diagnosed at an early stage in two individuals. In both cases, preoperative endoscopy failed to detect the cancer. However, in random biopsies taken from endoscopically normal gastric mucosa, cancer cells were detected. Considering the overall small tumor size in both patients, the detection of tumor cells through random biopsies was a very fortunate incident for our family and underlines the need for taking a minimum of 30 deep biopsies as recommended in the Cambridge protocol. Despite advanced endoscopic techniques, the overall detection rate through preoperative endoscopic biopsies is low. In 87.9% of CDH1 -mutation carriers, foci of signet cells were initially detected after prophylactic gastrectomy [ 11 ].

In addition, women carrying a CDH1 mutation have an increased risk for lobular breast cancer. There is insufficient evidence for a risk-reducing mastectomy, although it might be discussed in individual cases based on the family history [ 12 ]. Compared to non-lobular breast cancers, there is a reduced sensitivity to detect lobular breast cancer by mammography [ 13 ]. Extrapolated from the data for high-risk hereditary breast cancer, surveillance programs for early detection include e.g. bilateral MRIs beginning at the age of 30 years [ 12 ]. Following the recommendation of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (GC-HBOC), our patient was offered annual MRIs and ultrasound of the breast until the age of 70 years. Although it is still unclear whether colon cancer is part of the CDH1- related tumor spectrum, we recommended colonoscopies more frequently and at a younger age for all mutation carriers (every 3 years starting at age 40) compared to our current national guidelines (every 5 years starting at age 50).

The diagnosis of diffuse gastric cancer with signet cells will likely prompt the pathologist to an immediate histopathological workup including immunohistochemistry for E-cadherin. However, these steps should be taken with great caution. As the CDH 1 gene is a tumor suppressor gene, the inactivation of both alleles is necessary for tumor initiation. The inactivation of the second allele in mutation carriers occurs mainly by hypermethylation of the CDH1 promotor [ 14 ]. While hypermethylation itself will result in a silencing of the respective allele and ultimately to a loss of its protein, some mutations give rise to a translated but non-functional protein. Currently, more than 180 pathogenic germline mutations in the CDH1 gene are listed in HGMD® Professional (2019.4). Most of these are truncating mutations which are predicted to elicit nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [ 15 ], which would again result in a loss of the protein. Around 20% of all the published pathogenic alleles are missense mutations which are more prone to result in non-functional, but translated and therefore potentially immunohistochemically detectable protein. The latter could result in an erroneous exclusion of a CDH1 -associated disease. The mutation identified in our family was shown before in another publication to escape nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and lead to aberrantly spliced RNA [ 16 ]. Indeed, E-cadherin expression was immunohistochemically detected in the histopathological workup in the surgical specimen of our index patient and could have led to the misinterpretation of a non- CDH1- associated diffuse gastric cancer. Given this assumption, no genetic testing would have been performed, and the underlying genetic cause would not have been unraveled. In the case of our family, this again would have hindered predictive testing for relatives at risk and the identification of two mutation carriers and three non-mutation carriers. Considering the poor prognosis of patients suffering from invasive diffuse gastric cancer, the patient’s father, brother and aunt (and potentially their progeny) had a major benefit from this genetic testing. The index patient’s child and the brother’s child (Fig. 1 , IV. 2, IV. 1) were infants at the time of genetic counseling. Predictive testing in individuals at risk younger than 18 years is a controversial issue. Rare cases of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer in individuals before the age of 18 have been reported [ 17 , 18 ]. It has therefore been suggested to offer predictive testing to individuals before the age of 18 on a case by case basis [ 5 ]. The IGCLC has agreed that genetic testing of minors at risk should consider the earliest age of cancer onset in the respective family as well as their physical and psychological resources.

In our case, we decided to evaluate future recommendations for clinical management for families affected by hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and offer genetic counseling to the minors involved in their teens. Because of an independent but severe medical illness, the aunt (III.) and her husband as the legal guardians, decided not to test their daughter. With regard to prenatal testing, there are a number of ethical issues as well as legal provisions to be addressed, especially if testing is being considered for the purpose of pregnancy termination rather than early detection and surveillance. This sensitive issue was thoroughly discussed with the brother of the index patient. The German national legal framework allows invasive prenatal testing in case of a potential treatment during pregnancy or childhood (not applicable in case of CDH1 -associated diffuse gastric cancer) or in case of an expected disease manifestation before the age of 18 years (subject of interpretation in case of CDH1 -associated diffuse gastric cancer, see above). During consultation the family ruled out invasive prenatal testing for further family planning due to ethical reasons, although preimplantation genetic diagnosis was an option the family would consider in the future.

In this case of a young patient with sudden death, awareness and recognition of a CDH1-associated hereditary diffuse gastric cancer facilitated the detection of one additional case of early gastric cancer in a family member and most likely prevented two more relatives (and potentially their progeny) from developing gastric cancer, which has a poor prognosis. Therefore, a family history leading to the suspicion of a hereditary cause of diffuse gastric cancer should prompt genetic counseling and low-threshold genetic testing of the CDH1 gene despite histological expression of E-cadherin.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations.

Computed tomography

Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer

International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium

(messenger) Ribonucleic Acid

Rawla P, et al. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(1):26–38.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric cancer: diffuse and so-called intestinal type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:331–49.

Article Google Scholar

Junli MA, et al. Lauren classification and individualized chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(5):2959–64.

Lee JY, et al. The characteristics and prognosis of diffuse-type early gastric cancer diagnosed during health check-ups. Gut Liver. 2017;11(6):807–12.

van der Post RS, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical guidelines with an emphasis on germline CDH1 mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 2015;52:361–74.

Kaurah P, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Seattle: GeneReviews®, University of Washington; 2002. 1993-2020. [last updated 2018 Mar 22].

Google Scholar

Weren RDA, et al. Role of germline aberrations affecting CTNNA1, MAP3K6 and MYD88 in gastric cancer susceptibility. J Med Genet. 2018;55:669–74.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sánchez-Tilló E, et al. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and induces an EMT by recruiting the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1. Oncogene. 2010;2010(29):3490–500.

Fitzgerald RC, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet. 2010;47(7):436–44.

Shenoy S. CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation and gastric cancer: genetics, molecular mechanisms and guidelines for management. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10477–86.

Rocha JP, et al. Pathological features of total gastrectomy specimens from asymptomatic hereditary diffuse gastric cancer patients and implications for clinical management. Histopathology. 2018;73(6):878–86.

Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M, Buys SS, Farmer M, Friedman S, Garber JE, Kauff ND, Khan S, Klein C, Kohlmann W, Kurian A, Litton JK, Madlensky L, Merajver SD, Offit K, Pal T, Reiser G, Shannon K, Swisher E, Vinayak S, Voian NC, Weitzel JN, Wick MJ, Wiesner GL, Dwyer M, Darlow S. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian, Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(1):9-20. Retrieved Apr 27, 2020, from http://www.jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/15/1/article-p9.xml .

Porter AJ, et al. Mammographic and ultrasound features of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2014;58:1–10.

Grady W, et al. Methylation of the CDH1 promoter as the second genetic hit in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;26:16–7.

Krempely K, et al. A novel de novo CDH1 germline variant aids in the classification of carboxy-terminal E-cadherin alterations predicted to escape nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2018;4(4):1–8.

Frebourg T, et al. Cleft lip/palate and CDH1/E-cadherin mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. J Med Genet. 2006;43(2):138–42.

Wickremeratne T, et al. Prophylactic gastrectomy in a 16-year-old. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(3):353–6.

Guilford P, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–5.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all family members for the participation in this study.

Author information

Andreas Block and Alexander E. Volk contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, University Cancer Center Hamburg, University Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Elisabeth Niemeyer, Alexander Stein & Andreas Block

Department of Surgery, Regio Klinikum Pinneberg, Pinneberg, Germany

Hamid Mofid

Israelitisches Krankenhaus, Hamburg, Germany

Carsten Zornig

Institute of Pathology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Eike-Christian Burandt

Institute of Human Genetics, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Alexander E. Volk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MH and CZ were the referring physicians and surgeons of the patients. EB performed pathologic workup. AEV performed genetic counseling and testing. AB, AS and EN performed genetic counseling and was involved in the oncological treatment. EN, AB and AEV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elisabeth Niemeyer .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All participants were referred for routine diagnostic testing and genetic counseling. All participants gave their written informed consent for genetic testing. This study is in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). A copy of the consent form is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Consent for publication

All participants and their relatives gave written consent for publication of their personal and clinical details along with medical images.

Competing interests

Additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Niemeyer, E., Mofid, H., Zornig, C. et al. Case report: acute abdominal pain in a 37-year-old patient and the consequences for his family. BMC Gastroenterol 20 , 129 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01283-2

Download citation

Received : 03 September 2019

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 03 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01283-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer

- CDH1 germline mutation

- Prophylactic gastrectomy

BMC Gastroenterology

ISSN: 1471-230X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review

- Nina Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Jia Chen 3 ,

- Wenjun Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5398-8508 4 , 5 ,

- Zhengkun Shi 1 ,

- Huaping Yang 1 ,

- Peng Liu 6 ,

- Xiao Wei 7 ,

- Xiangling Dong 6 ,

- Chen Wang 3 ,

- Ling Mao 8 &

- Xianhong Li 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 1247 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2945 Accesses

36 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Case management (CM) is widely utilized to improve health outcomes of cancer patients, enhance their experience of health care, and reduce the cost of care. While numbers of systematic reviews are available on the effectiveness of CM for cancer patients, they often arrive at discordant conclusions that may confuse or mislead the future case management development for cancer patients and relevant policy making. We aimed to summarize the existing systematic reviews on the effectiveness of CM in health-related outcomes and health care utilization outcomes for cancer patient care, and highlight the consistent and contradictory findings.

An umbrella review was conducted followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review methodology. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus for reviews published up to July 8th, 2022. Quality of each review was appraised with the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. A narrative synthesis was performed, the corrected covered area was calculated as a measure of overlap for the primary studies in each review. The results were reported followed the Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews checklist.

Eight systematic reviews were included. Average quality of the reviews was high. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (corrected covered area = 4.5%). No universal tools were used to measure the effect of CM on each outcome. Summarized results revealed that CM were more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ quality of life, self-efficacy, survivor status, and satisfaction. Rare significant effect was reported on cost and length of stay.

Conclusions

CM showed mixed effects in cancer patient care. Future research should use standard guidelines to clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation. More primary studies are needed using high-quality well-powered designs to provide solid evidence on the effectiveness of CM. Case managers should consider applying validated and reliable tools to evaluate effect of CM in multifaced outcomes of cancer patient care.

Peer Review reports

Cancer ranks as one of the leading causes of premature death among population around 30–69 years old across 134 countries [ 1 ], and the global incidence of cancer is about to reach 30.2 million new cases and 25.7 million deaths by 2040 [ 2 ]. Earlier detection and diagnosis, and development of diverse cancer treatments have increased the survival rate of cancer patients. According to Quaresma et al. [ 3 ], the cancer survival in the UK has doubled over the last 40 years alongside the advancement in cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, number of challenges exist in the current cancer care all over the world. Many cancer patients oftentimes receive a series of long-running and exhausting multi-modal treatments and experience descent in psychological, physical and social functioning, which have a significant negative impact on their quality of life (QoL) [ 4 , 5 ]. In addition, the significant healthcare spending and productivity losses of cancer patients lead to a heavy patient economic burden, which is another substantial issue with cancer care [ 6 ]. A systematic approach is needed to mobilize and deliver appropriate resources, provide accessible, safe, and well-coordinated care for cancer patients received stressful treatments and shouldered heavy economic burden [ 7 ].

Case management (CM) is defined by the Case Management Society of America (CMSA) as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” (P. 11) [ 8 ]. According to the definition, CM is designed to use resources effectively to improve the quality of treatments, patient care services, and QoL of patients while reducing the relevant healthcare costs.

With the worldwide utilization of CM in cancer patient care, studies examining the effect of CM in improving patient-related outcomes or healthcare service use outcomes have been skyrocketing. Numbers of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published to synthesis the effectiveness of CM in recent years and often arrive at discordant conclusions. For example, Joo et al. [ 9 ] retrieved and synthesised results from nine experimental studies and found that CM effectively improved patients’ QoL and symptom management. While Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported equivocal effect on both QoL and symptom management. Chan et al. [ 11 ] reported that four of the five randomized controlled trials showed insignificant impact of CM on patients’ QoL. The inconsistent evidence on the impact of CM may confuse or mislead the future case management development and relevant policy making. Considering the exist of several systematic reviews and research synthesis available to inform the application of case management for cancer patient care improvement, umbrella review could now be undertaken to compare and contrast published reviews and to highlight the consistent or contradictory findings around the effect of CM on manifold aspects of cancer patient care [ 12 ]. Thus, the current review was conducted to 1) synthesis systematic reviews that assess the effects of CM on cancer patient outcomes (e.g., QoL, functioning status, symptom management, satisfaction, etc.) and health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay, treatment received compliance, etc.), 2) summarize measurement used in evaluating patient outcomes and health care utilization outcomes.

This umbrella review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review (UR) methodology [ 12 ] and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of systematic reviews (PRIO) checklist (see Additional file 1 ) [ 13 ]. This review has been registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7YQAP ).

Study searching methods

We performed literature search in five databases including MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus from inception to July 2022. Ethical approval and patient consent were not necessary since all analyses were based on previously published articles. The searching strategies in all five databases were developed with the help of a health science librarian. See Additional file 2 for the searching strategy and results in MEDLINE (Ovid). The studies were selected using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals diagnosed with any type of cancer at any cancer stages (early to advanced). Reviews targeted on people with no specified cancer diagnose were excluded.

Intervention

Case management interventions targeted on cancer patients. Case management is defined as a “collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” [ 8 ]. Only reviews in which the effectiveness of CM as defined above was analyzed separately from other interventions were considered.

Individuals in comparison groups received “treatment as usual” (TAU). TAU may include various interventions called “standard of care,” “usual care,” or “standard treatment,” but generally refers to treatment as it is commonly provided. Only studies that compared case management with “TAU” were selected.

Patient outcomes (e.g., quality of life, symptom management, functioning status), health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay), etc.

Acute care hospitals and primary care settings (e.g., long-term care, nursing homes, community care services). Hospital was defined as any department of internal medicine or surgery as well as unspecified hospital settings.

Study design

Systematic review/meta-analysis that only included quantitative studies. We excluded studies full-texts unavailable online.

Study selection

All retrieved studies were imported into Covidence systematic review software [ 14 ] and the duplicates were removed. Then, titles and abstracts were independently assessed by two researchers (XW and XD) according to the inclusion criteria. After that, the full texts of the selected abstracts were obtained and reviewed by the same two researchers (XW and XD) independently. The reference list of included studies was reviewed and searched for additional studies. Any disagreement between the two researchers were resolved through consultation with a senior researcher (PL).

Quality appraisal for included reviews

Two reviewers (NW and LM) independently assessed the methodological quality of the individual studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [ 15 ]. The tool aims to determine the extent to which the review has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis [ 15 ]. It consists of 11 criteria scored as yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. We adopted a scoring system used in previously published systematic reviews [ 16 , 17 ]. For each article, a rating score was derived by taking the number obtained in the quality rating and dividing it by the total number of possible points allowed, giving each manuscript a total quality rating between 0 and 1. Studies were then classified as low (0–0.25), low-moderate (0.26–0.50), moderate (0.51–0.75), or high (0.76–1.0).

Data extraction

We developed the data extraction form based on the research questions, and extracted following information: characteristics of included reviews such as publication year range, whether conducted meta-analysis or not, type of cancer patients, age of population, type and number of primary studies included; intervention names, components, and duration; outcomes and evaluation tools used; author’s conclusions and interpretations. Two researchers (NW and LM) extracted data independently from all included articles into an Excel spreadsheet and another researcher (XL) verified it for accuracy.

Data synthesis

We were unable to statistically pool outcomes due to the heterogeneity of outcomes of the included reviews. Therefore, we conducted a narrative synthesis [ 18 ] of the numerical data of individual studies outcomes. The studies were summarized and synthesised by two reviewers (NW and ZS) independently and double checked by a third author (HY). Following the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we used a summary table to present clear, specific, and structured results from the selected reviews, and then synthesised these results to identify broad conclusions. To summarized information about the interventions we coded data into features, components and delivery strategies, and inductively developed themes within each domain as they emerged from the studies. As suggested by Li and colleagues [ 19 ], we grouped outcomes into: global QoL of patients, functional status (i.e. physical, cognitive, emotional, role, social), symptom management, cost, hospital (re)admission, length of stay, treatment received compliance, provision of timely treatment.

For clarity the term ‘primary studies’ refers to the articles found within the included reviews. As several primary studies are included in more than one review, the overall results and conclusions of an overview can be biased. To assess this bias, the degree of overlap between reviews was calculated with the Corrected Covered Area (CCA) method. The details of the CCA calculation have been described by Pieper and colleagues [ 20 ] elsewhere. A CCA score of less than 5% is regarded as a slight overlap, 5–9.9% as moderate overlap, 10–14.9% as high overlap and over 15% as a very high level of overlap. This measure has been validated in which the number of overlapped primary publications has a strong correlation with the CCA [ 21 ].

Search outcome

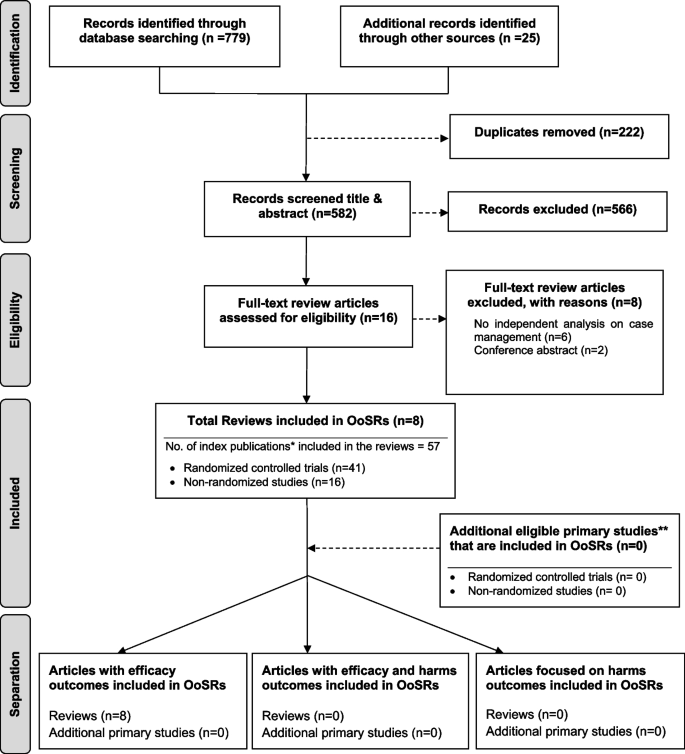

As shown in Fig. 1 , our search strategy generated 804 potentially relevant records. Upon removing the duplicates, 582 studies screened by title and abstract, 16 were identified for full text screening. We excluded eight of the 16 studies for the following reasons: no independent analysis on the effect of case management ( n = 6), or conference abstract ( n = 2). The eight remaining systematic reviews were selected and assessed for methodological quality. In total, all the eight reviews included 57 primary studies, among which 12 were duplicated included in two or three reviews. Forty-one of the 57 primary studies were randomized controlled trials (see Additional file 3 for included primary studies).

Flow chart for umbrella review. *Index publication is the first occurrence of a primary publication in the included reviews. **Additional eligible primary studies that had not been initially indentified by the search of the relevant reviews or obtained by updating the search of the included reviews

Methodological quality assessment

The quality assessment scores are presented in Table 1 . Only one review was rated as moderate because not clarify whether two or more reviewers independently assessed the quality of included primary studies, and did not report the methods to minimize errors in data extraction or publication bias. The other seven reviews were rated as high quality. Despite rated as strong, the seven reviews still companied with one or two issues on the assessment of heterogeneity, search strategy, and recommendations for policy and/or practice.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 presents a descriptive summary of characteristics of the eight systematic reviews [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The eight reviews aimed to identify evidence of the effectiveness of CM on cancer patients. Three of the studies were a systematic review with meta-analysis [ 10 , 25 , 26 ]. Five of the eight reviews adhered to the PRISMA statement [ 11 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], two adopted Cochrane systematic review methodology [ 9 , 10 ].

The eight reviews were published between 2008 and 2021, the primary studies in the reviews were published between 1983 and 2018. The number of primary studies regarding to CM included in each review ranged from three to 20. Five of the eight reviews included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the remaining reviews included a combination of study designs that involved RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental studies (e.g., cohort study). The age of review participants ranged from 7 to 97 years and mean ages range from 48.63 to 66.31 years, which covers populations from children to elders. The total number of participants in each review ranged from 327 to 9601. Seven of the eight reviews included primary studies targeted on multiple types of cancer including breast, lung, colorectal, cervical, ovarian, prostate, gastric, hepatocellular, etc. Most of the primary studies included in the eight reviews were conducted in the United States, and there were also studies conducted in Canada, Australia, Europe (i.e., Germany, UK, Turkey, Switzerland, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Netherlands) and East Asia (i.e., Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia).

CM interventions

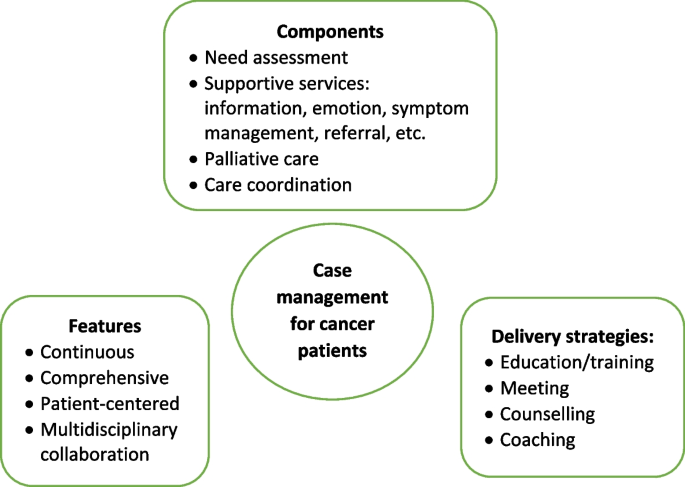

As shown in Table 2 , three studies reviewed trials of nurse-led CM interventions [ 9 , 25 , 26 ], two reviewed CM-like interventions that not termed as ‘CM’ while meet the CM definition by the CMSA [ 8 , 23 , 24 ]. Only one study reviewed CM focus solely on skill-training or symptom management [ 19 ]. All studies reviewed trials that facilitated the CM in a multidisciplinary collaboration approach. The duration of CM ranged from 4 days to 5 years. We presented the feature, components and delivery strategies of CM interventions for cancer patients in Fig. 2 by summarizing descriptions in each review. Congruent with the components defined by CMSA [ 8 ], all CM interventions included patient assessment, supportive services such as information and emotion support, care coordination by conducting education, consultation, and in-person, telephone or online coaching for regular follow-up. One critical component of CM interventions for cancer patients is the provision of palliative care. Control groups (CGs) of all studies reviewed in the reviews received usual treatment of care.

Features, components, and delivery strategies of case management for cancer patient care

Corrected Covered Area (CCA)

Table 3 presents the CCA for each outcome and as a whole. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (CCA = 4.5%). In addition, no overlapping of primary studies was found for six of the 16 outcomes, including self-efficacy, psychological function, hospital (re)admissions, length of stay, and provision of timely treatment. Only one outcome (i.e., symptom management) showed slight overlap (0.7%). The CCA for other five outcomes (i.e., global QoL, physical function, role function, patient satisfaction, cost) evaluated by more than 2 reviews were between 5 to 9.9%, indicated a moderate overlap. The CCA for survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance were over 10%.

Measurement used

Table 4 presents the quantitative measurement used in primary studies. As shown in Table 4 , studies investigated global QoL using different QoL-related scales, among which Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) (used in 15 primary studies) were most frequently applied, followed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) (used in 11 primary studies), and short form health survey (i.e., SF-8, SF-12, SF-36) (used in 10 primary studies). Different types of FACT tool were used according to the cancer types. For example, FACT-G was used for general cancer patients assessment, and FACT-B was used to evaluate breast cancer-related QoL. For the assessment of overall symptom management, SF-36 and Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) were used most frequently (used in four primary studies each). Different dimensions of SF-36 were also applied to evaluate other outcomes such as physical, emotional, and social function. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was the top employed tool in measuring the psychological function of patients. Patients’ sick leave days and the number of patients return to work were top employed metrics to evaluate the role function of patients. No unified tools were utilized to assess patient satisfaction towards the CM and majority of the primary studies used self-developed questionnaires.

Effect of CM on patient and health care utilization outcomes

The main outcomes from the seven systematic reviews are presented and summarized in Table 5 . Seven of the eight reviews reported the effects of case management on patients’ global QoL and showed mixed findings. Around half (49%, 19/39) of the primary studies included in the seven reviews reported significant positive impact of CM on global QoL. As for the functional status, there was a strong concordance among primary studies regarding the effectiveness of CM in improving cognitive function (e.g., uncertainty, health perceptions) (89%, 8/9); Equivocal effects were reported on psychological (e.g., patient anxiety, depression), physical (e.g., arm function), role function (e.g., sick leave days, patients returning to work), emotional (e.g., mood) and social function (e.g., social support) [ 9 , 11 , 26 ]. The findings regard to symptom management were more positive, with 75% (18/24) primary studies included in seven reviews revealed significant positive impact of CM on symptom severity and symptom distress decrease of pain, nausea, fatigue, discomfort, etc. Three of the four primary studies in two reviews [ 9 , 11 ] showed no significant influence of CM on patients’ self-efficacy. Wulff et al. [ 23 ] and Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported mixed findings on the impact of CM on survivor status, with four of the six primary studies reported significant positive impact. The effect of CM on patient satisfaction was reported in five reviews and showed mixed results.

Of the eleven primary studies reported cost, only one controlled before-and-after study in Joo et al.’s [ 9 ] review reported significant impact on monthly cancer-related medical costs. The evidence concerning patients’ length of stay yielded no significant findings. Overall significant positive effect was reported on hospital (re)admission (e.g., inpatient and ICU admission rate), treatment received compliance (e.g., therapy acceptance or completion rate), and provision of timely treatment.

This umbrella review is the first to summarize the results of systematic reviews that synthesised the evidence on the effectiveness of CM on cancer patient outcomes and relevant health care utilization. Most reviews (7/8) showed a high methodological quality. Different tools were used to measure the effect of CM on the same outcome. The evidence regards to the effectiveness of CM is mixed. The summarized results revealed that CM was more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ global QoL, psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function, self-efficacy, survivor status, and patient satisfaction.

No universal tools were used to measure improvement of each outcome in the CM group compared with the control group, making it challenging to conduct a meta-analysis of studies results [ 22 , 27 ]. This is a common issue faced the included reviews. Five of the eight reviews failed to conduct meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity [ 9 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 ]. Joo and Huber [ 22 ] conducted a review of reviews on the effect of CM on health care utilization outcome of chronic illness patients, they recognized the same problem and suggested using valid and standardized tools to minimize the differences in measurements. Despite various tools used, our review showed that FACT, EORTC QLQ-C30, and short form health survey (i.e., SF 36, SF 12, and SF 8) were most frequently applied to measure the effect of CM on the global QoL of cancer patients. These tools were also used in evaluating specific dimensions of QoL such as psychological, physical, emotional, and social function. This aligned with previous reviews [ 28 , 29 ] that found FACT and EORTC QLQ-C30 were the most common and well developed QoL instruments in cancer patients. FACT-G is considered appropriate for use with any types of cancer patients [ 30 ]. It is a 27-item tool that includes four primary QoL domains: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being [ 31 ]. Other versions of FACT (FACT-B [ 32 ], FACT-L [ 33 ] and FACT-E [ 34 ]) for specific type of cancer patients were developed by incorporating the four dimensions of FACT-G with additional cancer type-specific questions. EORTC QLQ-C30 was another type of QoL assessment tools for cancer patients specifically. It was developed by Aaronson et al. [ 35 ] and contains four domains: physical, emotional, cognitive and social functions, and a higher score indicates better QoL. The Short Form Health Survey is the most commonly used measure in evaluating QoL domains of patients suffering from a wide range of medical conditions [ 36 ]. Research found it provides reliable and valid indication of general health among cancer patients [ 37 , 38 ].

QoL is the most frequently evaluated outcome in our review with 39 primary studies in seven reviews reported the global QoL of cancer patients. Joo et al. [ 9 ] found that CM interventions improved QoL of cancer patients. Yin and colleagues [ 24 ] revealed that cancer patients achieved better physical and psychological condition through symptom management, needs assessment, direct referrals, and other services in CM. However, summarized results in our review show that the CM had equivocal effect on cancer patients’ global QoL and dimensions including psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function. Cognitive function is the only dimension showed positive change. Despite CM interventions share similar definitions and principles [ 8 ]. It is hard to foresee which aspect(s) of CM interventions contribute to certain effects due to their comprehensiveness [ 24 ]. Yin et al. [ 24 ] argued that the control group may receive a higher quality treatment than planned usual care since all the participants were not blinded and they have been informed about the aim of the study. Indicating a more rigorous design and evaluation is needed to avoid this information bias.

In the meantime, included reviews claimed that few primary studies reported enough details about CM interventions, including model used [ 10 , 11 ], dose and intensity [ 9 , 19 , 24 ], interventionist qualifications [ 11 ], protocol or manual used [ 9 , 23 ], and fidelity [ 23 ]. Particularly, the COVID-19 pandemic has considerable influence on the care delivery for cancer patients. For example, the more frequently utilization of remote patient monitoring technologies that incorporate community resources, primary care and allied health disciplines, as well as clinics to keep cancer patients away from acute care hospitals as much as possible [ 39 ]. Many of these changes have been integrated within routine case management for cancer care during the pandemic [ 39 ]. It is well-needed to report how those CM intervention were conducted follow standard reporting guidelines, in order to provide recommendation for future research.

Our review showed that CM is likely to improve the symptom management. Eighteen of the 24 included primary studies reported positive effect of CM on symptom management, including decrease symptom distress or severity of fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting. The same positive effect on symptom management was also revealed in other types of patients. Joo and colleagues [ 40 ] found that CM reduced substance use and significantly influenced abstinence rates among populations experienced substance disorders. Reviews by Stokes et al. [ 27 ] and Welch et al. [ 41 ] revealed positive effect on symptom release among people with long-term conditions and diabetes patients, respectively. The multidisciplinary collaboration approach adopted [ 10 ], and availability of professional support post-hospitalization [ 9 , 41 ] in CM might contribute to the improvement of symptom management. Specifically, multidisciplinary team involves physicians, nurses, and aligned healthcare professionals provides throughout and multifaced symptom assessment and management [ 10 ]. In addition, CM programs continuously follow up and advocate for patients’ concerns [ 8 ]. Specifically, case managers are available to patients 24 hours a day by phone call even after discharged, providing opportunity for immediate professional guidance on symptom management [ 9 ].

As for other patient outcomes, there is insufficient evidence of effect on self-efficacy and survivor status of cancer patients. Only three and four primary studies in total reported these two outcomes, respectively. Eleven primary studies in five reviews reported patient satisfaction and showed mixed results. Inconsistent results were found in a review of reviews by Buja et al. [ 7 ] which concluded strong evidence of CM improving satisfaction of patients with long term condition. In agreement with Joo and Huber’s [ 25 ] review, we found that CM favorably affect healthcare utilization outcomes such as treatment received compliance, hospital (re)admission, and provision of timely treatment. While the strength of the evidence was limited either by the high level of primary studies overlapping (CCA) (i.e., treatment received compliance, CCA = 13.3%) or the small number of studies reported certain outcomes (i.e., hospital admission, provision of timely treatment). Notably, the summarized results from included reviews conclude that despite theoretical benefits [ 8 ], in practice there is only slight evidence of benefits on reduction in the cost of care for cancer patients participated in CM interventions.

We provide some recommendations for future research based on the summarized results: 1) Future research should clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation, including theoretical underpinnings, dose and intensity, interventionist qualifications, protocol or manual used, fidelity, etc. In that way these details can be included in future systematic reviews, and effectiveness of individual elements of the intervention can be examined [ 27 ]. We recommend use standard guidelines to help organize the CM intervention reporting. For example, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDeiR) is one of the most popular guidelines that could be used to report the full breadth of CM interventions: from intervention rationale to assessments of treatment adherence and fidelity [ 42 ]. 2) More rigorous trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of CM. 3) Studies should also explore the barriers to and facilitators of CM implementation across various types of cancer patients at different stages, providing evidence for conducting successful CM implementation in the future.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted an umbrella review instead of a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of review outcomes. Although an umbrella review can only show the tendency or direction of the effect of CM rather than providing the magnitude or significance level of influence [ 12 ], the current evidence on the effect of CM in cancer patients was comprehensively summarized. There were some challenges when conducting the review. First, the quality of the umbrella reviews was greatly affected by the quality of the original reviews [ 12 ]. In this study, we confirmed that the quality of the original reviews were mostly high as assessed by the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [ 15 ]. Second, if the primary studies were included in several reviews, they may produce bias related to overlapping effects [ 20 ]. By calculating the CCA, we showed that 75% (12/16) of the individual outcomes had no to moderate overlapping of primary studies between included reviews, revealing that these results from each review were relatively independent. Cautious are needed on the summarized evidence regards to the effect of CM on survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance because of the high overlapping (CCA > 10) between the reviews reported those outcomes.

There are limitations in our review. The first limitation concerns that the searching was limited to English-language articles and did not access unpublished papers. Second, as suggested by the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we did not assess the quality of evidence from included reviews, it increased the uncertainty of the review findings.

Effective CM aims to influence the health care delivery system in improving the health outcomes of cancer patients, enhancing their experience of health care, and reducing the cost of care. Our review found mixed effects of CM reported in cancer patient care. The summarized results revealed that CM was likely to improve symptom management for cancer patients. We also found CM has the tendency to enhance cancer patients’ experience of health care such as reducing hospital (re)admission rates, improving treatment received compliance and provision of timely treatment. Only slight evidence of benefits was reported on reducing the cost of care for cancer patients. Overall, more rigorous designed primary studies are needed to demonstrate the effects of CM on cancer patients and explore the elements of effective CM interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

Corrected Covered Area

Control groups

- Case management

Case Management Society of America

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Breast Cancer

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Esophagus

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- General

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-Lung

- Quality of life

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Joanna Briggs Institute

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Randomized controlled trials

Symptom Distress Scale

Medical Outcomes Study 8-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 12-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey

Treatment as usual

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global cancer observatory: Cancer today: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today .

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global Cancer observatory: Cancer tomorrow: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow .

Quaresma M, Coleman MP, Rachet B. 40-year trends in an index of survival for all cancers combined and survival adjusted for age and sex for each cancer in England and Wales, 1971-2011: a population-based study. Lancet. 2015;385:1206–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61396-9 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–67. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468 .

Yan AF, Stevens P, Holt C, Walker A, Ng A, McManus P, et al. Culture, identity, strength and spirituality: a qualitative study to understand experiences of African American women breast cancer survivors and recommendations for intervention development. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28:e13013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13013 .

Article Google Scholar

Yabroff K, Mariotto A, Tangka F. Annual report to the nation on the status of Cancer, part II: patient economic burden associated with Cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1670–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab192 .

Buja A, Francesconi P, Bellini I, Barletta V, Girardi G, Braga M, et al. Health and health service usage outcomes of case management for patients with long-term conditions: a review of reviews. Prim Heal Care Res Dev. 2020;21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000080 .

Case Management Society of America. CMSA’s standards of practice for case management, Revised 2016. 2016. http://www.naylornetwork.com/cmsatoday/articles/index-v3.asp?aid=400028&issueID=53653 .

Google Scholar

Joo JY, Liu MF. Effectiveness of nurse-led case Management in Cancer Care: systematic review. Clin Nurs Res. 2019;28:968–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818773285 .

Aubin M, Giguère A, Martin M, Verreault R, Fitch MI, Kazanjian A, et al. Interventions to improve continuity of care in the follow-up of patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:1–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007672.pub2 .

Chan RJ, Teleni L, McDonald S, Kelly J, Mahony J, Ernst K, et al. Breast cancer nursing interventions and clinical effectiveness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:276–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002120 .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-11 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, Ntzani E, Haidich AB. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.002 .

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review sofware. Covidence. 2016. https://get.covidence.org/systematic-review-software?campaignid=15030045989&adgroupid=130408703002&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvc7KuJDO-QIVh97ICh1BeQKnEAAYASAAEgI4APD_BwE .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Heal. 2015;13:132–40 http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html .

Gifford W, Rowan M, Dick P, Modanloo S, Benoit M, Al AZ, et al. Interventions to improve cancer survivorship among indigenous peoples and communities : a systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:7029–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06216-7 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gifford W, Squires J, Angus D, Ashley L, Brosseau L, Craik J, et al. Managerial leadership for research use in nursing and allied health care professions : a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0817-7 .

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods Programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf .

Li Q, Lin Y, Liu X, Xu Y. A systematic review on patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors of randomised clinical trials: direction for future research. Psychooncology. 2014;23:721–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3504 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007 .

Choi J, Lee M, Lee JK, Kang D, Choi JY. Correlates associated with participation in physical activity among adults: a systematic review of reviews and update. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4255-2 .

Joo JY, Huber DL. Case management effectiveness on health care utilization outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41:111–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918762135 .

Wulff CN, Thygesen M, Søndergaard J, Vedsted P. Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–7 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/8/227 .

Yin YN, Wang Y, Jiang NJ, Long DR. Can case management improve cancer patients quality of life?: a systematic review following PRISMA. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022448 .

Wu YL, Padmalatha KMS, Yu T, Lin YH, Ku HC, Tsai YT, et al. Is nurse-led case management effective in improving treatment outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;00:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14874 .

McQueen J, McFeely G. Case management for return to work for individuals living with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24:203–10. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.5.203 .

Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, Checkland K, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Effectiveness of case management for “at risk” patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132340 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, Lauzier S, Théberge V. Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: an updated systematic review (2001-2009). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:178–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq508 .

Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:1–31 https://jeccr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-9966-27-32 .

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 .

Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The F unctional a ssessment of C hronic I llness T herapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 .

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy- breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–86. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.3.974 .

Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-F .

Darling G, Eton DT, Sulman J, Casson AG, Cella D. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22055 .

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 .

Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to score version two of the SF-36® health survey. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000.

Treanor C, Donnelly M. A methodological review of the short form health survey 36 (SF-36) and its derivatives among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:339–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0785-6 .

Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312116671725 .

Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Joseph R, Hart NH, Milley K, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2021:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01128-1 .

Joo J, Huber D. Community-based case management effectiveness in populations that abuse substances. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:536–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12201 .

Welch G, Garb J, Zagarins S, Lendel I, Gabbay RA. Nurse diabetes case management interventions and blood glucose control: results of a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.026 .

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Dual (co-)authorship

We declared that no author has authored one or more of the included systematic reviews.

This study was supported by 1) Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Nursing (2017TP1004, PI: Jia Chen), Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department, 2) Changsha Natural Science Foundation (kq2202365, PI: Nina Wang) Changsha Science and Technology Department, and 3) Management research foundation of Xiangya Hospital (2021GL12, PI: Nina Wang).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Nina Wang, Zhengkun Shi & Huaping Yang

National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, Xiangya Hospital, Changsha, China

Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

Jia Chen, Chen Wang & Xianhong Li

School of Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Wenjun Chen

Center for Research on Health and Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Intensive Care Unit of Cardiovascular Surgery Department, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Peng Liu & Xiangling Dong

The 956th Army Hospital, Linzhi, China

School of Nursing, Changsha Medical University, Changsha, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the production of this review. NW and WC conceptualized and designed the study and are the guarantor of the paper. JC and ZS conducted the literature search. PL, XW and XD were involved in the study screening. NW, LM and XL participated in the quality appraisal and data extraction. NW, ZS and HY conducted the data analysis. NW drafted the manuscript. WC and XL revised the manuscript. All authors participated in the review of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wenjun Chen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2..

Searching strategies.

Additional file 3.

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, N., Chen, J., Chen, W. et al. The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res 22 , 1247 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Download citation

Received : 04 April 2022

Accepted : 21 September 2022

Published : 14 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cancer patients

- Umbrella review

- Health care

- Outcome assessment

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 64, Issue 7

- A case of small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy followed by photodynamic therapy

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Department of Internal Medicine; College of Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital and Cancer Research Institute, Jungku, Daejeon, South Korea

- Professor J O Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital and Cancer Research Institute, 640 Daesadong, Jungku, Daejeon 301-721, South Korea; jokim{at}cnu.ac.kr

Here, we present the case of a 51-year-old man with limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC) who received concurrent chemoradiotherapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT). The patient was diagnosed as having LS-SCLC with an endobronchial mass in the left main bronchus. Following concurrent chemoradiotherapy, a mass remaining in the left lingular division was treated with PDT. Clinical and histological data indicate that the patient has remained in complete response for 2 years without further treatment. This patient represents a rare case of complete response in LS-SCLC treated with PDT.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2008.112912

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

A case report of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with long-term survival for over 11 years

Editor(s): NA.,

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital, 5-11-13, Sugano, Ichikawa, Chiba, Japan.

∗Correspondence: Tatsu Matsuzaki, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital, 5-11-13, Sugano, Ichikawa, Chiba 272-8513, Japan (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Abbreviations: CBDCA = carboplatin, CDDP = cisplatin, CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen, DTX = docetaxel, ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR-TKI = epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer, OS = overall survival, PD = progressive disease, PEM = pemetrexed, PFS = progression-free survival, RC = re-challenge chemotherapy, RR = response rate, UICC = Union of International Cancer Control.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The Ethics Committee of our hospital approved the study and provided permission to publish the results.

The patient provided written informed consent and has provided consent for publication of the case.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Rationale: