Undergraduate Program

Philosophy studies many of humanity’s fundamental questions, to reflect on these questions and answer them in a systematic, explicit, and rigorous way—relying on careful argumentation, and drawing from outside fields as diverse as economics, literature, religion, law, mathematics, the physical sciences, and psychology. While most of the tradition of philosophy is Western, the department seeks to connect with non-Western traditions like Islam and Buddhism.

The Bachelor of Liberal Arts degree is designed for industry professionals with years of work experience who wish to complete their degrees part time, both on campus and online, without disruption to their employment. Our typical student is over 30, has previously completed one or two years of college, and works full time.

The graduate program in philosophy at Harvard offers students the opportunity to work and to develop their ideas in a stimulating and supportive community of fellow doctoral students, faculty members, and visiting scholars. Among the special strengths of the department are moral and political philosophy, aesthetics, epistemology, philosophy of logic, philosophy of language, the history of analytic philosophy, ancient philosophy, Kant, and Wittgenstein.

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code - DO NOT REMOVE

Site name and logo, harvard divinity school.

- Prospective Students

- Give to HDS

- PhD Program

The Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program is jointly offered by HDS and the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Find detailed information about PhD fields of study and program requirements on the Committee on the Study of Religion website.

With a focus on global religions, religion and culture, and forces that shape religious traditions and thought, the PhD prepares students for advanced research and scholarship in religion and theological studies.

Resources for the study of religion at Harvard are vast. We offer courses in the whole range of religious traditions from the ancient Zoroastrian tradition to modern Christian liberation movements, Islamic and Jewish philosophies, Buddhist social movements, and Hindu arts and culture. Some of us work primarily as historians, others as scholars of texts, others as anthropologists, although the boundaries of these methodologies are never firm. Some of us are adherents of a religious tradition; others are not at all religious. The Study of Religion is exciting and challenging precisely because of the conversations that take place across the complexities of disciplines, traditions, and intellectual commitments.

- Master of Divinity (MDiv) Program

- Master of Religion and Public Life (MRPL) Program

- Master of Theological Studies (MTS) Program

- Master of Theology (ThM) Program

- Dual Degrees

- Nondegree Programs

- Ministry Studies

- Professional and Lifelong Learning

- Finding Courses

- Academic Advising

Applicants to the PhD program must have completed a four-year Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree. A professional degree in architecture, landscape architecture, or urban planning is recommended but not necessary. For students planning to pursue the Architectural Technology track within the PhD program, a background in architecture and/or engineering is required. For more information, please contact Professor Ali Malkawi .

The deadline to apply for admission to the PhD program in the 2025-26 academic year will be December 15, 2024.

To be eligible for admission, applicants must also show evidence of promising academic work in their field of interest or in closely related fields.

Students from outside the United States must demonstrate an excellent command of spoken and written English. Applicants who are non-native English speakers can demonstrate English proficiency in one of three ways:

- Receiving an undergraduate degree from an academic institution where English is the primary language of instruction.

- Earning a minimum score of 80 on the internet based test (iBT) of the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL)*

- Earning a minimum score of 6.5 on the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) Academic test.*

A master’s degree or other graduate degree is not accepted as proof of English proficiency. More details about English proficiency can be found on the Harvard Griffin GSAS website.

Applicants from underrepresented and historically marginalized communities are particularly welcome and highly encouraged to apply. Attend a virtual information session to learn more.

All applicants must indicate a proposed major area of study at the time of their initial application. These proposed areas of study should be congruent with the interests and expertise of at least one Graduate School of Design faculty member associated with the PhD program.

All applicants are required to submit a GRE score as part of an application to the PhD program. Additionally, applications must include the following:

- Unofficial transcript(s).

- Three letters of recommendation.

- A statement of purpose that gives the admissions committee a clear sense of the student’s intellectual interests and strengths and conveys their research interests and qualifications.

- A short personal statement.

- A writing sample or samples (totalling no more than 20 pages, not including references). This can be a paper written for a course, journal article, and/or thesis excerpt. The writing sample should preferably focus on a subject related to architecture, landscape architecture, or urban planning.

- Please note that unless a specific justification is provided by the applicant, design portfolios are not typically considered as part of the application.

Applications to the PhD program in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning are received through the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. For more information on the application process, requirements, and its timeline, visit their website .

If you have additional questions, please contact Margaret Moore de Chicojay , the PhD program administrator and a key point of contact for incoming and current students.

Harvard Griffin GSAS and Harvard GSD do not discriminate against applicants or students on the basis of race, color, national origin, ancestry or any other protected classification.

- Utility Menu

- Department Intranet

The Concentration

Welcome to the Philosophy Concentration!

Most of the students who choose to pursue a concentration in philosophy did not have any background in philosophy when they entered Harvard. And those students who have had encounters with philosophy tend to find that academic philosophy at the college level is quite different from what has come before. In other words, you're not at any disadvantage if you're coming to philosophy completely fresh.

To prepare students to succeed in the concentration, our introductory courses (numbered between 1 and 90) are designed to introduce students both to the topic of the course and the skills of writing philosophy papers and reading philosophical texts. We also offer writing support through our Department Writing Fellow . Because philosophical writing is so distinctive, students do not need to complete an Expos class before taking our classes . We will teach you philosophical writing in our classes. There is no requirement that you take an introductory course.

The philosophy concentration is non-linear . There is no set sequence of courses that students need, or even should, follow as they make their way through the concentration. Very few of our courses have explicit pre-requisites, so students can take courses in whatever order makes sense to them, given their intellectual goals and interests.

Very broadly speaking, the undergraduate curriculum falls into three parts. We offer introductory level courses, numbered between 1 and 90; tutorials, numbered 97 and 98; and more advanced courses for undergraduates and beginning graduate students, numbered 101-199. There are also two special courses, PHIL 91r and PHIL 99.

The department offers several options for those interested in philosophy: a primary concentration in Philosophy (including Honors eligibility); the Mind, Brain, and Behavior Track; and Joint Concentrations between philosophy and other disciplines.

If you're considering a joint concentration with philosophy, we strongly encourage you to talk to us about it early. Generally, we advise students that their intellectual interests need not be mirrored precisely by their choice of concentration or other aspects of the institution of the College. In practice, that means that students need not think of requiring "permission" to do interdisciplinary work by pursuing a joint concentration. By its nature, philosophy is interdisciplinary, and students interested in philosophical topics are encouraged to take classes in other disciplines that enrich their experience. We recognize this interdisciplinarity through the mechanism of so-called "related courses" in the different concentration tracks: courses from outside the philosophy department that a student can petition to count towards the philosophy concentration. We also value this interdisciplinarity in our students' theses. Students who draw on intellectual resources from outside philosophy as part of writing their honors thesis face no disadvantage in how their theses are evaluated.

Below you will find a detailed description of the requirements for each of our concentration and secondary offerings. As you'll see, all of the pathways include distribution requirements within subareas of philosophy. Our courses fall into four such subareas. Here's a brief description of each, together with the abbreviation we use in our listing of which courses fit into which subareas.

- Logic ("Logic"): courses in logic.

- Contemporary Metaphysics and Epistemology ("M&E"): courses in contemporary metaphysics and epistemology, broadly construed, so as to include philosophy of language, science, and mind.

- Moral and Political Philosophy and Aesthetics ("M/P/A"): courses in ethics, moral and political philosophy, and aesthetics.

- History (“History”): courses covering texts from historical (typically, pre-20th century) periods of philosophy.

If you have any questions about our concentration pathways or courses, please come to see any of us in the Office of Undergraduate Studies ( link to Google Calendar ).

As you'll see, our different concentration tracks include distribution requirements within philosophy. A list of which subareas of philosophy each of the courses we offer satisfies is available below, as well.

- List of Past Courses with Subareas

Philosophy Basic Requirements: 11 courses (44 credits)

- Contemporary metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of science, philosophy of mind, philosophy of language.

- Contemporary ethics, political philosophy, aesthetics.

- History of philosophy.

- Tutorials: Two courses. See item 2 below.

- Five additional courses in philosophy.

- Tutorial I: PHIL 97, group tutorials at the introductory level on different philosophical topics, required. Letter-graded. A one-semester course typically taken in the spring of the sophomore year.

- Tutorial II: PHIL 98, group tutorials at the advanced level on different philosophical topics, required. Letter-graded. A one-semester course typically taken fall or spring of the junior year. Under exceptional circumstances, and with permission of the Director of Undergraduate Studies, a student may substitute a 100-level course in philosophy to meet this requirement.

- Thesis: None.

- General Examination: None.

- Philosophy courses may include courses listed under Philosophy in the course search in courses.my.harvard.edu.

- Pass/fail: All courses counted for the concentration must be letter-graded or Sat/Unsat.

- No more than four courses numbered lower than 91 may be counted for the concentration.

Requirements for Honors Eligibility (Thesis): 11 courses (44 credits)

- Two courses in the history of philosophy.

- Tutorials: Four courses. See item 2 below.

- Two additional courses in philosophy.

- Same as Basic Requirements .

- Senior Tutorial: PHIL 99, individual supervision of senior thesis. Permission of the Director of Undergraduate Studies is required for enrollment. Graded SAT/UNSAT. Honors candidates ordinarily enroll in both fall and spring terms. Enrolled students who fail to submit a thesis when due must, to receive a grade above UNSAT for the course, submit a substantial paper no later than the beginning of the spring term Reading Period.

- Thesis: Required of all senior honors candidates. Due at the Tutorial Office on the Friday after spring recess. No more than 20,000 words (approximately 65 pages). Oral examination on the thesis, by two readers, during the first week of spring Reading Period.

- Other information: Same as Basic Requirements .

Requirements for Honors Eligibility (Non-Thesis): 12 courses (48 credits)

Students who earn honors through this track are only eligible to graduate with honors, not with high or highest honors.

- Tutorials: Two courses courses. See item 2 below.

- Seven additional courses in Philosophy.

- Courses in the first year are weighted normally.

- Courses in the second year are weighted with a multiplier of 1.2.

- Courses in the third year are weighted with a multiplier of 1.4.

- Courses in the fourth year are weighted with multiplier of 1.5.

Mind, Brain, and Behavior Track: 15 courses (60 credits)

Students interested in studying philosophical questions that arise in connection with the sciences of mind, brain, and behavior may pursue a program of study affiliated with the University-wide Mind/Brain/Behavior (MBB) Initiative , which allows them to participate in a variety of related activities. MBB track programs must be approved on an individual basis by the Philosophy MBB advisor . Further information can be obtained from the Undergraduate Coordinator .

- PSY 1 (previously SLS 20).

- Molecular and Cellular Biology 80.

- Junior year seminar in Mind, Brain, and Behavior.

- Philosophy 156.

- One course in logic.

- Two further courses in contemporary metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of science, philosophy of mind, or philosophy of language.

- Two courses drawn from ethics/political philosophy/aesethetics or the history of philosophy in any combination.

- Two further MBB-listed courses from outside the Philosophy department, to be selected in consultation with the MBB adviser.

- Tutorial I: Same as Basic Requirements .

- Tutorial II: Same as Basic Requirements.

- Senior Tutorial: Same as Requirements for Honors Eligibility .

Joint Concentrations: Philosophy as Primary Concentration

8 courses in Philosophy (36 credits)

- One course in each of the four areas (see item 1.a. of Basic Requirements )

- Four additional courses in philosophy; tutorials count toward this requirement.

- At least four courses in the other field. Many departments require more; consult the Head Tutor or DUS of the other field.

- Tutorial I: Same as Basic Requirements

- Tutorial II: Same as Basic Requirements

- Thesis: Required as for honors eligibility in Philosophy but must relate to both fields. Oral examination by twoo readers, one from each department.

- General examination: None required in Philosophy.

- No more than two courses numbered lower than 91may be counted for the concentration.

- Other requirements are the same as Basic Requirements

Joint Concentrations: Another Field as Primary Concentration

6 courses in Philosophy (24 credits)

- One course in three of the four areas (see item 1.a. of Basic Requirements)

- Three additional courses in philosophy; tutorial counts toward this requirement.

- Tutorial: Tutorial I (PHIL 97), usually taken in the junior year.

- Thesis: Required. Must relate to both fields. Directed in the primary field; one reader from Philosophy.

- General Examination: None required in Philosophy.

- No more than two courses numbered lower than 91 may be counted for the concentration.

- Other requirements are the same as Basic Requirements .

Secondary Field Requirements

Requirements: 6 courses (24 credits), general philosophy.

A selection of courses from across the discipline.

- PHIL 97: Tutorial I.

- History of Philosophy.

- Contemporary Moral and Political Philosophy and Aesthetics.

- Contemporary Metaphysics and Epistemology, broadly construed.

- One other course in Philosophy. An introductory course in the Department (numbered below 91) is preferred, but in consultation with the Director of Undergraduate Studies, students may elect to forego taking an introductory course.

- One other Philosophy course.

Value Theory

Examination of historical and contemporary theories about the basis and content of such moral and political concepts as the good, obligation, justice, equality, rights, and freedom. This also includes issues in aesthetics.

- Three courses in contemporary moral and political philosophy and aesthetics, as categorized on the Philosophy Department website.

- One other course in Philosophy. An introductory course in the department in contemporary moral and political philosophy or aesthetics (numbered below 91) is preferred, but in consultation with the Director of Undergraduate Studies, students may elect to forego taking an introductory course.

Contemporary Metaphysics and Epistemology

Examination of issues in Metaphysics and Epistemology, broadly construed, so as to also include philosophy of language, science, and mind.

- Two courses in metaphysics and epistemology, broadly construed, as categorized on the Philosophy Department website.

- One other course in philosophy. An introductory course in the department in metaphysics and epistemology, broadly construed (numbered below 91) is preferred, but in consultation with the Director of Undergraduate Studies, students may elect to forego taking an introductory course.

History of Philosophy

- Three courses in the history of philosophy, as categorized on the Philosophy Department website.

- One other course in Philosophy. An introductory course in the department in the history of philosophy (numbered below 91) is preferred, but in consultation with the Director of Undergraduate Studies, students may elect to forego taking an introductory course.

Declaring a Concentration

Ned Hall (DUS): [email protected]

Seth Robertson (Assistant DUS): [email protected]

Luke Ciancarelli (Undergraduate Studies Fellow): [email protected]

You can sign up for appointments by following this link . After the meeting, we will approve your concentration declaration request in my.harvard.

If you are declaring a joint or double concentration, you should also follow the declaration instructions for your other field. Double concentrations also require that students submit two signed copies of the Double Concentration Form , one for each concentration.

PhD in Population Health Sciences

Prepare for a high-impact career tackling public health problems from air pollution to obesity to global health equity to the social determinants of health.

The PhD in population health sciences is a multidisciplinary research degree that will prepare you for a career focused on challenges and solutions that affect the lives of millions around the globe. Collaborating with colleagues from diverse personal and professional backgrounds and conducting field and/or laboratory research projects of your own design, you will gain the deep expertise and powerful analytical and quantitative tools needed to tackle a wide range of complex, large-scale public health problems.

Focusing on one of five complementary fields of study at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and drawing on courses, resources, and faculty from the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, you will become well-versed in a wide variety of disciplines while gaining specialized knowledge in your chosen area of study.

As a population health sciences graduate, you will be prepared for a career in research, academics, or practice, tackling complex diseases and health problems that affect entire populations. Those interested in pursuing research may go on to work at a government agency or international organization, or in the private sector at a consulting, biotech, or pharmaceutical firm. Others may choose to pursue practice or on-the-ground interventions. Those interested in academics may become a faculty member in a college, university, medical school, research institute, or school of public health.

The PhD in population health sciences is a four-year program based at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in the world-renowned Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. The degree will prepare you to apply diverse approaches to solving difficult public health research issues in your choice of one of five primary fields of study:

- Environmental health

- Epidemiology

- Social and behavioral sciences

- Global health and population

In your first semester, you and your faculty adviser will design a degree plan to guide you through the program’s interdisciplinary requirements and core courses, as well as those in your chosen field of study. After successfully completing the preliminary qualifying examination, usually at the end of your second year, you will finalize your general research topics and identify a dissertation adviser who will mentor you through the dissertation process and help you nominate a dissertation advisory committee.

All population health sciences students are trained in pedagogy and teaching and are required to work as a teaching fellow and/or research assistant to ensure they gain meaningful teaching and research experience before graduation. Students also attend a special weekly evening seminar that features prominent lecturers, grant-writing modules, feedback dinners, and training opportunities.

All students, including international students, who maintain satisfactory progress (B+ or above) receive a multiyear funding package, which includes tuition, fees , and a competitive stipend.

WHO SHOULD APPLY?

Anyone with a distinguished undergraduate record and a demonstrated enthusiasm for the rigorous pursuit of scientific public health knowledge is encouraged to apply. Although a previous graduate degree is not required, applicants should have successfully completed coursework in introductory statistics or quantitative methods. Preference will be given to applicants who have either some relevant work experience or graduate-level work in their desired primary field of study.

APPLICATION PROCESS

Like all PhD (doctor of philosophy) programs at the School, the PhD in population health sciences is offered under the aegis of the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS). Applications are processed through the Harvard Griffin GSAS online application system located at gsas.harvard.edu/admissions/apply.

OUR COMMUNITY: COMMITTED, ACCOMPLISHED, COLLABORATIVE

As a PhD in population health sciences candidate, you will be part of a diverse and accomplished group of students with a broad range of research and other interests. The opportunity to learn from each other and to share ideas both inside and outside the classroom will be one of the most rewarding and productive parts of the program for any successful candidate. The program in population health sciences provides these opportunities by sponsoring an informal curriculum of seminars, a dedicated student gathering and study area, and events that will enhance your knowledge, foster interaction with your peers, and encourage you to cooperatively evaluate scientific literature, while providing a supportive, collaborative community within which to pursue your degree.

As members of both the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences communities, students have access to the Cambridge and Longwood Medical Area campuses. Students also qualify for affordable transportation options, access to numerous lectures and academic seminars, and a wealth of services to support their academic and personal needs on both sides of the Charles River.

LEARN MORE Population Health Sciences Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health www.hsph.harvard.edu/phdphs

A Theory of (Climate) Justice

Britta Clark draws on the insights of philosophy to navigate the ethics of efforts to mitigate global warming

Share this page

The summer of 2024 in the Northern Hemisphere continues to break records for extreme heat. Several US cities have experienced new record-high temperatures this year, and according to a report by the European Union’s Copernicus Programme, the June just past was the hottest ever recorded on Earth, narrowly beating a global temperature record set in June 2023. But while climate change poses challenges to all of humanity, the crisis affects different populations unequally, depending on location, infrastructure, and access to housing and air conditioning. New technologies could help mitigate the effects of climate change, though their full impact is still being tested.

In these circumstances, what would it mean to work toward justice and equity in responding to the climate crisis? And, as researchers develop the technologies of the future, how should this concern for justice impact humanity’s actions in the present?

As a PhD candidate in philosophy at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), Britta Clark applies her discipline’s methods to reach a new understanding of the ethical and political issues raised by the climate crisis—and humanity’s response to it. Addressing the potential role of technologies like carbon removal and solar geoengineering, Clark expands existing notions of success in mitigating the effects of climate change to include considerations of justice and equity.

Helping a Friend

Carbon dioxide removal technologies pull carbon from the ambient air and then sequester it, typically burying the element deep underground. Solar geoengineering envisions shooting aerosols, usually sulfate aerosols, into the stratosphere to temporarily abate climate change impacts by reflecting some of the sun’s rays back into space and away from Earth. To illustrate the ethical dilemmas that accompany the deployment of these new technologies, Clark offers an analogy.

“Imagine you have a big task to perform,” she says. “Say, you have to shovel your driveway in the winter. And you know that maybe, later in the afternoon, you'll have this set of technologies that will maybe make the challenge of shoveling your driveway a little bit easier. You’re fairly certain but not totally certain. There’s a chance that the new technology might make things more difficult, adding more snow to your driveway. What should you do with that information?”

Clark argues that mainstream answers to that question––in terms of the climate response––take a narrow view of success. Specifically, when policymakers focus on economic metrics, they ignore other possibilities for a fair climate future. Continuing the analogy of snow removal as climate change mitigation, Clark explains, “The standard economic models will tell you, ‘Well, it's going to be easier to shovel your driveway later, with the new technology, so you should slow down.’” In other words, Clark says, economists have calculated that it is financially optimal to wait for these technologies to help us meet climate goals––and, according to this view, to move more slowly in current climate preservation efforts, like reducing carbon emissions.

We know that climate change will impact already disadvantaged people the most, but in mainstream discussions, there’s been less focus on the relationship between fairness and . . . emerging [climate] technologies. —Britta Clark

“But that's not the only response you could have,” Clark continues. “You might also say, ‘It's going be easier to shovel my driveway later, so I should get started now. And then later, I can go help a friend.’” In terms of climate change, well-resourced nations could potentially use their wealth to speed up their own response and then provide assistance to other countries. Clark says that “helping a friend” is an option that should not be ignored as we consider how to use climate technologies––and that economic models limit our thinking by closing off certain possibilities that may actually deserve careful consideration.

“We know that climate change will impact already disadvantaged people the most,” she says, “but in mainstream discussions, there’s been less focus on the relationship between fairness and these emerging technologies.”

Clark argues that a view informed by moral and political philosophy also helps us identify errors in common ways of thinking about new technologies. “Although most proponents of carbon removal are quick to say that the technology is not a substitute for reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” Clark explains, “in practice, economic models do substitute carbon removal for emissions reductions in all those circumstances where doing so is supposedly cheaper. In other words, the models tell us we can shovel the driveway a bit slower.” But Clark argues that we should also consider the possibility that humanity should raise its standards in the climate change response. “Just because there’s the potential that a technology could enable us to meet our goals at lower costs,” she says, “doesn't mean that that is the only possible role of the technology. We also could raise the ambitiousness of our climate goals.”

By approaching these issues from the perspective of philosophy, Clark hopes to “open up our thinking beyond what the economic models assume” and to consider more broadly the ways we could understand the role of new technologies. To do this, Clark critically analyzes climate debates––identifying their underlying assumptions––and then formulates and tests out principles of what justice and morality could look like in the current situation. She also specifically considers the issue of intergenerational justice or what moral responsibilities we have toward Earth’s future generations.

Clark’s project requires extensive knowledge from outside her main field of philosophy. As her advisor, Associate Professor of Philosophy Lucas Stanczyk, explains, “Thinking about the ethical dimensions of climate change is difficult because it requires plural subject-matter expertise, hard-won philosophical insight, and a duly cynical orientation towards the politics. Britta Clark’s research brings all of these virtues to bear on urgent ethical questions at the intersection of science, technology, and climate change.”

Harvard via the Green Mountains and New Zealand

Britta Clark’s deep interest in the environment dates back to her childhood. Growing up in a town surrounded by Vermont’s Green Mountain National Forest led her to value time spent outdoors in natural environments––and, eventually, to become invested in environmental education and protection efforts. “I’m still pretty involved in a small nature center there, the Blueberry Hill Outdoor Center,” says Clark, “and with organizing trail workdays, events, and doing some conservation work.”

As an undergraduate at Bates College, Clark became drawn to the interdisciplinary humanities field of environmental studies, which allowed her to pursue interests in the philosophical, historical, and cultural issues associated with environmentalism. This experience led her to then pursue a master’s degree in philosophy as a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Otago in New Zealand, where she focused on analyzing relationships between humans and nature.

Studying overseas broadened Clark’s perspective because of the high value given to Indigenous traditional knowledge and practices. “If you told someone in the US to think of rivers as being people, for example, they might say that sounds insane––but people are much more willing to entertain ideas like that in New Zealand, just because they’re more accustomed and exposed to them,” Clark says.

Over time, Clark realized climate change was a very human problem and wanted to devote more of her intellectual energy to thinking about policy debates, leading her to her eventual PhD research area––and to Harvard’s Department of Philosophy. “In general, I was very impressed by both the philosophical rigor and the willingness to speak to policy-related issues in Harvard’s department. It seemed like a group of people who wanted to do really good philosophical work on relevant, current issues,” she says.

Needful Questions

Following her graduation in fall 2024, Clark plans to stay at the University as a postdoctoral researcher in the Harvard Solar Geoengineering Research Program, a group of mostly scientists and engineers studying climate mitigation technologies. She looks forward to learning from their experiences––and to giving a voice to new ways of thinking that flow from an ethical, philosophical, and humanities-based perspective.

Beyond Harvard, Clark hopes her work will inspire new ways of thinking about our response to climate change, allowing policymakers, scientists, and citizens to imagine a wider range of possible futures. Professor of Philosophy Gina Schouten, a member of Clark’s dissertation advising committee, says this contribution to the discussion on climate change is badly needed.

[Britta’s] work is theoretically innovative but primarily oriented toward practical, needful questions such as, ‘Which technological strategies should we pursue, how, and why?’ —Professor Gina Schouten

“Britta’s dissertation project develops and defends an actionable normative theory that can guide decision-makers with respect to climate policy in our unjust circumstances,” Schouten says. “ Her work is theoretically innovative but primarily oriented toward practical, needful questions such as, ‘Which technological strategies should we pursue, how, and why?’”

Clark’s hope is that her work can bring increased clarity to these debates and open up possibilities foreclosed by standard ways of thinking about new technologies. “You often hear people say, ‘We know what we need to do about climate change––we just need the political will to do it,’” she says. “But once we think about all the different ways that we could transition away from fossil fuels, and which technologies we could use to make that transition, it becomes clear that there are tons of remaining ethical questions in this area.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join our newsletter, subscribe to colloquy podcast, connect with us, related news.

Stormquake: How Old Seismograms Could Reveal the Future of Hurricanes

Hurricanes are growing threats in the age of climate change, but incomplete records hinder our understanding of how they evolve. Graduating Harvard Griffin GSAS student Thomas Lee tries to bridge this gap.

Cold Facts about Global Warming

Research by PhD student Kara Hartig could help forecasters predict weather patterns as climate change makes them more extreme.

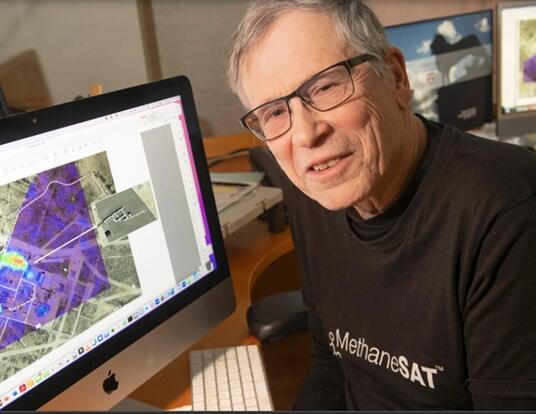

New Satellite Will Combat Climate Change

Its development overseen by Professor Steven Wofsy, PhD '71, MethaneSAT entered Earth’s orbit aboard a SpaceX rocket launched on Monday. It could soon play a key role in combating climate change.

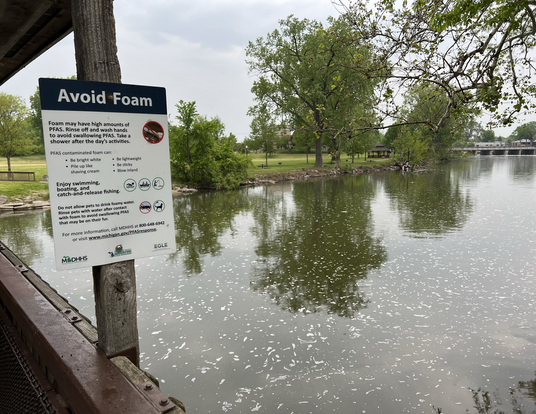

Before ‘Forever’

With her 2024 Harvard Horizons project, PhD student Heidi Pickard seeks to uncover the prevalence of the precursors of toxic 'forever chemicals' in our water and food and assess their impact on the environment and health.

Get the Reddit app

This subreddit is for anyone who is going through the process of getting into graduate school, and for those who've been there and have advice to give.

Advice we needed - PhD: Philosophy (words of wisdom)

I didn't know this existed, and now that I know it exists, I'm putting it here. I feel that this advice applies to most other humanities programs. A friend of mine shared this with me (she's currently in the PhD program at Rutgers in a field other than philosophy), and I feel this stuff is really helpful.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Advice for applying to PhD Programs in Philosophy Alex Guerrero Rutgers University – New Brunswick (October 2021)

Here is some advice for applying to PhD programs in Philosophy.

A significant caveat: I’m the Director of Grad Admissions at Rutgers, a program that focuses on ‘analytic’ philosophical approaches, and the advice sometimes is specific to applicants looking at those kinds of programs.

This originally appeared on Twitter as a mega-thread, but that was super hard to read and follow, so here it is written out.

In Spring 2021, I offered to give personalized feedback to people who applied to the Philosophy PhD program at Rutgers and were not admitted. I have now sent 103 such replies. I apologize if I missed your request. If this general advice isn’t helpful, and you still would appreciate personal feedback, please send me an email.

What follows are some general thoughts about the Big 4 components of your PhD application: (1) grades/transcript, (2) personal statement, (3) letters of recommendation, and (4) writing sample. I begin by providing some general context regarding the process, and I conclude by briefly talking about a few other things, such as GREs, etc.

General context about the application pool. This past year, we received almost 400 applications. We are looking to enroll 5-7 people, and typically admit 10-14 people in order to hit that target. Those are absurd numbers. It’s much more competitive than law school, or med school, or anything else. From what I’ve heard, other programs range from 150 applicants up to around 300-400. It’s very competitive everywhere.

Our process. The Director of Graduate Admissions makes an initial cut from the full pool (380) down to around 100 applications. That’s the first big cut. I’ve now been in that role for several years, and although my process isn’t perfectly precise, I typically make this cut by looking at (1) grades/transcript, then (2) personal statement, then (3) letters of recommendation—in that order. I rarely do more than glance at (4) writing samples at this stage.

The 100 or so remaining files are then reviewed by members of a graduate admissions committee, newly constituted each year. Each member of the 5-person admissions committee (4 people plus me) is assigned 20-25 files to read closely, with each committee member recommending 4-7 people to the final pool for discussion by the full committee.

The committee is composed of people working in a wide range of subfields, and files are typically assigned to committee members based on their expertise. The full 5-person committee then meets to discuss the 25-30 files that make it to the final pool, and to decide who in that final pool should be admitted, wait-listed, and rejected.

The applicant pool. It’s very strong. Every year, we see files with stellar grades in philosophy from fancy places like Harvard, Oxford, Princeton, Stanford, and so on. And we see files from people who got stellar grades at big public schools, SLACs, leading international institutions, and so on. Few people apply to graduate school if they have not excelled in philosophy wherever they happen to be.

There are also the many students who have also done high-level work as graduate students in terminal MA programs, or at other PhD programs. Each year the pool has dozens of people who have already published in significant professional philosophy journals.

Given all of that, it’s helpful if you have some sense of yourself as either a “paper perfect” applicant or someone who is a bit outside of that box. Paper perfect applicants will have near- perfect grades (3.8 or 3.9 or above, straight firsts, etc.) from elite institutions, with superlative letters from fancy well known people, they will work on perfect fit topics (more on that later), and maybe even have significant publications or professional philosophy accomplishments already. Honestly, there are probably 25-50 “paper perfect” applicants each cycle.

Some of those paper perfect applicants get in everywhere. But many do not. Some struggle to get in anywhere. And many who are not “paper perfect” do very well. This is interesting. And probably confounding. I expect much of it turns on the writing sample. More on that later.

For each thing I say, I can imagine—and have probably seen—exceptions. We regularly admit people with imperfect grades, or from schools that I know nothing about. We often don’t know the letter writers of successful applicants. The writing samples are usually excellent, though. Still, there are many general things that can be said. I hope some of them might be helpful.

(1) Grades/Transcript

For most applicants, the single best evidence we have of your ability, effort, and potential as a philosopher comes from your record as a student, particularly in philosophy courses. There are cases in which a person starts slow, or has a rough patch, or finds themselves as a student only late in the game, but it is hard to overcome a troubling transcript.

The big problems: (a) very little philosophy coursework, (b) a difficult to discern amount of philosophy coursework, (c) few philosophy courses that are like the courses one might take from Rutgers faculty, (d) multiple grades in philosophy courses that were B+ or below, or (e) a downward trend in philosophy course performance.

With (b), you can sometimes help us out by listing the philosophy courses, their instructors, and maybe even what you covered somewhere. This is particularly true for non-US transcripts, where it is sometimes opaque what the applicant studied.

On (d) and (e), we know there are reasons that people might have a rough semester or two, and it does help to address those directly in your personal statement, an additional document, or via your letter writers (if you can talk to them about it). But it is hard to get into a competitive PhD program with a B-average in philosophy courses, unless those have been supplanted by later philosophy coursework somewhere, or unless there is some significant explanation provided, as well as signs of exceptional promise elsewhere in the application.

With (a), (c), (d), and (e), if people are serious about getting into a competitive PhD program and they are having trouble on that front, I typically recommend that they consider a funded terminal MA program.

There are many excellent MA programs in philosophy, and you can learn more about those programs and funding here ( https://fundedphilma.weebly.com/ ) and here ( https://www.philosophicalgourmet.com/m-a-programs-in-philosophy/ ). Many do very well at placing people into top PhD programs, and they can be a very good way of addressing (a)-(e). They allow you to focus on philosophy. Most graduate school grades are in the A range. The professors will help you engage material at greater length and depth. You can take courses in areas like those you might study in graduate school. And so on.

(2) Personal Statement

The personal statement serves a very specific function in the application; it tells those reading the application (a) what topics you want to focus on in graduate school and (b) why we should expect you to flourish if you focus on those topics in our program. Those reading the personal statement will also be thinking about our program is a good fit given what you say in (a), which is a part of assessing (b).

It is also nice to get a little window into who you are, particularly if how you came to the topics you are interested in is relevant to (b) why we should expect you to flourish in working on these topics. Maybe you bring something distinctive to them, based on your education or life experience.

But the personal statement is not a place to try to convince us that you love philosophy (we assume you do!), or that you have been aiming toward a Philosophy PhD your whole life (surprising! implausible?), or that you can’t imagine doing anything else (depressing!).

Also, I have 400 of these to read. Don’t make it hard to figure out what topics you want to work on. Indeed, I would start the personal statement by saying: “My main philosophical interests are X, Y, and Z.”

X, Y, and Z should be relatively broad, even just established subfields of philosophy (e.g., political philosophy, moral philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology, etc.). Avoid being excessively narrow; it makes you seem somewhat philosophically incurious if you seem like you only have an interest in one super-specific thing.

Ideally, at least 2/3 of the areas you mention should be things that our program is strong in, so that the fit is clear. Be wary of listing things that we have no coverage of at all. It will make it seem like you would be happier somewhere else. If you list such areas, you should reveal awareness that we don’t focus on those areas.

After identifying your interests, the rest of the personal statement should be aimed at making the case that you will flourish if you work on those topics. This often involves detailing work you’ve already done in those areas—classes taken, papers or theses written, relevant empirical fields you’ve studied, etc. This is where we can see if you seem to know something about what you are getting yourself into.

A peek behind the scenes... The personal statement helps us to categorize you. That informs who I will assign to read your application. If you say ‘metaphysics’ I will give you to one of the metaphysics people on the committee. It also helps us with class balance. We can’t enroll 7 people all of whom work on philosophy of language (or whatever). This is bad for advising purposes and for job market purposes on the other side.

Many of us like to think of ourselves as philosophers, not just philosophers of mind, or language, or ethicists, or whatever. But there are still these practical purposes. You will end up writing dissertations on a particular topic, not all of philosophy. But it is nice to see people with somewhat broad and interesting X, Y, and Zs, as long as the fit is there.

Some people like to help explain why they will flourish working on a topic at Rutgers by mentioning some names of those of us at Rutgers who work on that topic, how they have read and liked that work, etc. Should you name names? I’m of two minds about this.

The case for doing it: it reveals knowledge of the department (congratulations, you can use the World Wide Web), it makes fit with the department clear, and for most of us, we still feel a little positive buzz when we see our name listed.

The case against doing it: we already know who is on our faculty, there is the danger of leaving off someone relevant (who might be on the committee! yikes!), there is the danger of including someone who no longer wants anything to do with that topic (or, at other departments only of course, someone who no one should want to work with), the positive buzz thing is kind of icky and it shouldn’t work even if it does.

So, the choice is yours. If you are going to name names, do your homework. (Look at who has been advising students from the placement page. Look at the websites of professors to see what they are working on now, not just 20 years ago.)

If you don’t name names, you should still think about how what you are discussing fits with our program. Some people say something generic like “Rutgers would be an excellent place to pursue these interests, given the Philosophy Department’s strengths and coverage of these areas.” But you don’t need to do that.

(3) Letters of Recommendation

Admission committee members vary widely in how much attention they pay to letters of recommendation. A few basics. You should have 3 letters from philosophy instructors. Ideally, they should all be philosophy professors . Go with people who know you and your philosophy work well. That is more important than that they are big names. Big names don’t hurt, but only if they are really in your corner.

Some people were double majors or took lots of courses in some nearby field. They sometimes want to get letters from non-philosophers. I would counsel against that, unless it is someone who sometimes publishes in philosophy journals, or co-authors with philosophers, or teaches philosophy.

We won’t trust that your Nobel Prize-winning chemistry professor knows what it takes to flourish in philosophy. They can say generic things about you being smart, responsible, etc., but that won’t help that much. It would be better to have an upper-level philosophy grad student who taught you, ran a discussion section, and graded your work, if you don’t have a philosophy professor. They won’t have as big a comparison class, but they at least know a lot about philosophy.

To get strong letters, you need to have interacted with your professors both in print and in person. They should have read and commented on your written work, and you should have talked philosophy with them—at least in class, but ideally also sometimes outside of class, while working on a paper, etc.

Depending on the kind of institution and program you are in, this might require some extra work on your part. I always thought going to office hours was for other people and didn’t do it. That’s a mistake. Especially once you are in upper-level, smaller seminars with a professor, you should take the time to talk to them, get feedback on your work, revise your work for them, etc.

Also, your letter writers should know your plans. After you take a class with them, talk to them about graduate school. Get their advice, provide them with all of your materials— grades/transcript, personal statement, CV, writing sample—well in advance of their letter being due. Meet with them to talk about your materials and plans. Ask for feedback on your materials.

A good letter writer is someone who is invested in your project of going to graduate school, who knows you and wants to help you take that step. If they seem highly skeptical in your interactions with them, they might not be the right letter writer for you.

(You might think about why they are skeptical, although also remember that they will have their own biases etc., so don’t let one person get you down, particularly if your grades and other ‘objective’ measures are strong.)

If you don’t have at least 3 fairly high-level philosophy courses (a thesis-writing course would count) in which you have received A-range grades and have come to know the professor well, it will be difficult to do well with PhD program admissions.

If you came to philosophy late, or came to the academic path late, you might consider first attending one of the many excellent MA programs in philosophy. You can learn more about those programs and funding here ( https://fundedphilma.weebly.com/ ) and here ( https://www.philosophicalgourmet.com/m-a-programs-in-philosophy/ ). These programs are great for building relationships with professors, working closely with them, getting in depth into philosophical ideas, and so on. All that makes for much stronger letters.

In my experience, the main role that letters end up playing is in the end stages, where the champions of a particular applicant might point to particularly glowing letters as an additional oomph in favor of their candidate, and opponents of an applicant might point to less than glowing letters as a red flag.

Often, their main value is in helping to put the applicant’s achievements in context beyond what we can see on the page: to give a fuller sense of how much the applicant did on their own, how diligent they are in sticking with something hard, what other difficulties and obstacles they might have faced, etc.

But when you read enough of these letters, you learn to take all of them with several grains of salt. Some people are always over the top, others are always muted, others seem to kind of blow the task off. And even the strongest letters can’t compensate for an underwhelming writing sample.

(4) Writing Sample

Although usually the last thing to get very careful attention in reading files, the writing sample is the thing that makes the biggest difference at the end. We routinely reject “paper perfect” applicants with ‘eh’ writing samples in favor of applicants with imperfections in the grades or letters, but who have fantastic writing samples. So, what makes for a fantastic writing sample?

People differ in what they care about most, but clarity, thoughtful engagement with relevant literature, and argumentative quality are three necessary components. The other main characteristics that elevate writing samples from fine to fantastic are creativity, ambition, and topical fit. I’ll come to those in a moment.

Let me begin by saying some possibly controversial things about how good philosophy comes into existence. I’ll begin by describing a method that rarely works. First, start with an interest in some topic that has been discussed a lot by philosophers. Second, read everything on that topic, over a long time, keeping kind of neutral notes on the views throughout. Third, try to think of something new to say. Disaster!

Maybe some people can do it that way, but it’s very hard to find your voice and keep your passion and energy throughout that process. Instead, you learn about the 18 moves that have been made, the 14 positions in logical space that have been occupied (like tanks running over flowers), and you can maybe spot another 2 or 3 that haven’t been occupied. You can write a paper that takes up one of those, but often you aren’t really excited about that position, it’s just kind of left over. And maybe for a reason...

Much better: start with something that is bugging you or disturbing you. Maybe it’s an actual thing in the world that is happening. Maybe it’s an idea that was presented in a class that just seems wrong somehow. Maybe it’s some text or topic that seems philosophically interesting, but which no one is talking about. Maybe it’s just a way of looking at things that comes to you from who knows where, while your mind wanders around (like flowers growing over tanks).

Follow those things. Pull them apart, see what’s going on inside. Write about them. Try to sort out what is bothering you. Write about that. Sometimes you’ll figure it out. Other times the problem remains, but you understand it better. Write that up. Don’t read or research all that much yet. Try to present things clearly, even argumentatively, so that someone outside your mind can join you in your disturbance or your intrigue.

With this animated, emotionally engaged, somewhat analyzed view on the issue or topic, start looking for what else might be out there. Sometimes you will be the first. Often, others will also have been disturbed or interested by the thing. Read what they’ve said but read argumentatively—bounce what they are saying off what you’ve come to think about the topic. Note places of agreement and disagreement. Work through their ideas, but only after you already have some of your own.

Go back to what you’ve written, and bring in these other ideas and voices, without giving them primacy or letting them dominate. Make sure to give credit where credit is due, but paraphrase and cite, don’t just directly quote. Keep the focus on the philosophical idea or problem, not the game of who said what about what (I mean, unless that is your game).

When it works out, the thing that emerges is often an interesting bit of philosophy. There might be other ways to “do philosophy”—maybe it depends a lot on the person.

But I find, especially for people starting out in generating ideas and papers, the puzzlement-first method [start with puzzled emotion or annoyance in response to a thing, do some thinking, do some writing, do some reading, do some more writing] works better than the topic-first method [start with a topic, read a ton, try to think of some new thing to say, write that thing up]. Follow your gut about what is interesting to you.

Some of this method depends on immersing yourself in the right waters, perhaps. Sit in on classes, have conversations with people, read twitter threads and blog posts, read the news, dig into some other academic field a little, engage with art or popular culture, read some random stuff, maybe even read some philosophy—and throughout, notice what interests and puzzles you, and follow those leads.

Writing the writing sample should be fun and exciting (and maddening and frustrating, on occasion). If it’s not, something has gone wrong. OK, back to what one hopes will emerge from all of this. A clear, appropriately scholarly, well-argued, creative, ambitious writing sample. A little more about each of those.

Clarity: it should be easy to read and understand your writing sample. Ideally, it should be easy for even non-specialists to read your writing sample. If it is somewhat technical in places, at least make the philosophical problem(s) and payoff evident. Explain jargon and technical terms. Polish the sentence-level writing. Make the organizational structure of the paper clear. Your prose can be powerful and interesting, but don’t let the writing obscure the meaning. Don’t send us 84 numbered paragraphs. You’re not Wittgenstein (probably). Don’t send us a genre- bending historical fiction/philosophy/autobiography mashup. You’re not Anazldúa (probably). For our program, we need something that looks like high-level analytic philosophy. It can be about anything. (But a caveat on topic in a moment.)

Engagement with literature: a big difference between a fantastic, standout writing sample and an ‘eh’ writing sample that reads like a competent term paper is that the ‘eh’ samples often engage only with one or two very prominent papers on a topic (such as one might be assigned in a seminar...). Standout writing samples will go in depth into a philosophical issue, figuring out what is out there that is relevant and engaging with that work in a way that reveals a sophisticated level of understanding.

This kind of research is hard to do and takes time. PhilPapers.org, the SEP, and Philosophy Compass are all your friend in this. Use Google Scholar to see what newer papers cite the big papers on the topic—and read those papers. Depending on where you are, The Philosophical Underclass FB group might be your friend.

This is also where it can be extremely useful to get feedback on your writing sample from your professors or grad students you know. They can point you to relevant issues to dig into more.

Argumentative quality: we are a squarely (ha ha in every sense) analytic philosophy department. I am into philosophy presented in many ways, some of which isn’t explicitly argumentative. But I wouldn’t recommend that for your writing sample.

Your writing sample should make an interesting or surprising argument for an interesting or surprising conclusion. It should be clear what your conclusion is and how you are arguing for it. I like explicitly stated arguments in premise-conclusion format, but you don’t have to be that mechanical about it. But you might think about why you are departing from that choice.

A significant part of argumentative quality comes in setting up the argument(s), making the case for the more controversial premises, and considering the philosophical implications of the conclusion(s). You should also present and respond to plausible objections to what you are arguing!

We are looking for your ability to engage with philosophical issues with subtlety and creativity. It’s OK if you don’t have an answer for everything! Better to acknowledge that than to just plow over a concern as if it’s not there or as if you don’t see it.

If you are a “paper perfect” applicant and you have a writing sample that does well by clarity, command and engagement of relevant literature, and argumentative quality, you are likely to do fairly well in the application process. But there are at least three more very important dimensions of writing sample quality that make a huge difference at the very end stages—even for “paper perfect” applicants: creativity, ambition, and topical fit.

Creativity and ambition: I’m going to put these two together, since they so often go together. The most common advice I give to applicants is to have a writing sample that is bold, creative, and ambitious. Do something new. Write about a topic that very few others have taken up or that has been neglected. Make an interesting argument for a weird new idea. Write about something that you are genuinely excited about. Write something you can imagine almost any philosopher getting excited about.

Sure, easier said than done. But we see a lot of perfectly competent writing samples that focus on an article or two by a philosopher or two on some narrow or well-trodden topic, competently reconstruct the views presented in those articles, raise a fine but unsurprising objection to the view, and call it a day. Papers like this get published in philosophy journals all the time.

But it’s hard to stand out with a writing sample like that. It’s hard to imagine anyone on the hiring committee saying—“this is awesome; this is my person!” It’s hard to feel confident that the person writing it will come up with an interesting, compelling dissertation project in 2 or 3 years. It’s much easier to feel that way if there’s already an interesting new idea, topic, approach, argument right there in front of you.

(This concern is amplified when the debate is an old and well-trodden one. We see a surprising number of writing samples that discuss something like Chalmers and Block on consciousness (or BonJour and Sosa on internalism v. externalism, or Rawls and Nozick on justice), state their views, and maybe make a few small points about their views. Some of these might be A term papers. But it is hard to see any spark there.)

Of course, there is risk with creativity and ambition. Don’t sacrifice clarity, engagement with relevant literature, or argumentative quality. Wild manifestos aren’t the way to go. Again: it’s a tough assignment. We know. That’s one reason it’s so impressive when someone pulls it off. Good term papers for classes often won’t cut it. If you don’t know what to write about, you might try something like the method I describe above.

Here’s an issue that goes beyond the philosophical quality of the writing sample and into something more practical. Topical fit: people often ask, is it OK if I say that I want to work on X and Y, but then send a writing sample on A, something completely different, and something that I don’t want to work on. My response: well, it’s not ideal, but if it’s the best thing you have, and you can’t come up with something else in time...

Here’s why it’s not ideal. Many admissions committees will have a distribution of subfield specialization. For example, there might be a history person, language/logic person, epistemology/mind person, value theory person, and a metaphysics person.

At many places, to the extent possible, files are given to specialists based on the expressed area interests of the applicants. If you say you want to work on metaphysics and language, either the metaphysics or language person is likely to get your file at the initial close read stage, and both will be given some deference in their assessment of your writing sample at the final stage. Most of the files we look at will be in our area, until the very final stage, when we all read everything. Sometimes we will ask for another reader on a writing sample if it is way out of our area and we have an expert on the faculty in that area, but that doesn’t always happen.

If your file is assigned to a specialist on X, because you say you want to work on X, but your writing sample is on A, it might be hard for that specialist to be as excited about your writing sample—at least when compared to some super-interesting writing sample in area X from some other applicant. You need people to be in your corner! If you say you’re a value theory person but then send in something on Descartes’s theory of mind, it’s going to be tricky to generate the same enthusiasm.

This point might not apply everywhere, and it depends on the mechanics of the process. But I suspect it is significant in many places. It also might be more pronounced when the mismatch is across bigger gulfs: value theory v. non-value theory, history v. contemporary, etc.

(An aside regarding topic: avoid topics that were hot a long time ago (when your profs may have studied the subject). One tell: the papers you are citing are all from the 1990s. It’s hard for anyone to get excited about incredibly well-trodden debates from a while ago. If you do have something new to say on one of these topics, that’s awesome, but you should be very clear about that up front, and really show that you know all the recent relevant literature, not just the big- name things from 20 or 30 years ago.)

As I hope is clear, the writing sample is the hardest part of the application, and it is the thing that you should spend the most time on. You should expect to spend several months (at least) on the writing sample, and to revise it significantly multiple times.

You should get feedback from at least 2 or 3 people—ideally your letter writers, but also possibly other professors or grad students you know well enough to ask. They can help with clarity and argumentation, identifying relevant literature for you to engage with, and raising objections for you to consider in the paper.

(5) GRE, where to apply, and more

The use of the GRE is in flux at many places, both because of the pandemic, and because of questions about its relevance to anything we should care about in doing graduate admissions. At the moment, Rutgers Philosophy is not requiring the GRE.

In general, for schools that require them, high GRE scores can help a person get a second look at the early stages (particularly helpful for people from programs likely to be unknown to admissions committees), middling GRE scores will make almost no difference either way, and very low GRE scores might raise a red flag. But that red flag can be lowered again by some kind of explanation somewhere, or by countervailing evidence.

How to decide where to apply? When you are clear on your areas of interest, look to see where the authors of important papers in those areas are teaching. Look at important journals in those areas, go to see who is on the editorial board of those journals, and figure out where they are teaching. Depending on the area, use the PGR specialty rankings or the Pluralists’ Guide to get a sense of what programs are worth looking at more closely. Talk to your professors or TAs, if they seem clued in.

Once you have a long list of programs to look at, visit departmental placement pages. Browse through faculty and grad student websites. Check out the APDA surveys on graduate satisfaction. If things still look promising, consider applying. You will get a lot more information later when you see where you have been admitted, go on in-person visits or talk to current grad students, and so on.

Important note: many programs offer fee waivers on the basis of financial hardship or being a member of a demographic group that is underrepresented in philosophy. Look into those if that applies to your situation.

There is a lot of luck involved throughout the process. I wish good luck to all of you (although that kind of defeats the point, given the nature of grad admissions; interpret it more generally so that it applies to whatever path you end up on).

By continuing, you agree to our User Agreement and acknowledge that you understand the Privacy Policy .

Enter the 6-digit code from your authenticator app

You’ve set up two-factor authentication for this account.

Enter a 6-digit backup code

Create your username and password.

Reddit is anonymous, so your username is what you’ll go by here. Choose wisely—because once you get a name, you can’t change it.

Reset your password

Enter your email address or username and we’ll send you a link to reset your password

Check your inbox

An email with a link to reset your password was sent to the email address associated with your account

Choose a Reddit account to continue

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

Quick Access

- Find Your Programmes

- Targeted Taught Postgraduate Programmes Fellowships Scheme (TPG)

- Research PhD - Full-time & Part-time

- Research MPhil - Full-time & Part-time

Sept 2025 Entry

The Department of Applied Social Sciences (APSS) is committed to serving the community through the dynamic integration of education, research and service through its applied social science research. APSS’s position as a large social sciences department with diverse areas of interest and expertise under one roof, and its location within a health and social science faculty, offers an advantageous position in inter-disciplinary research networks and initiatives. APSS research is characterised by:

A strong emphasis on social needs and policy relevant research;

A commitment to enhancing social betterment and improving the well-being of individuals, children, families and disadvantaged groups in our community;

A preference for collaborative work with partnering institutions in Hong Kong, China and the region; and

A commitment to developing theories of indigenous knowledge and practices.

As the hub of social sciences research in Asia, the Department houses four centres and networks to advance research collaboration with academic institutions, non-governmental organisations, the private sector, and government departments locally, in mainland China and overseas.

Please visit our website for more information about APSS.

Family, Child, Youth, and Ageing Studies

Active ageing; elder abuse; elder care

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3694 | ||

| 2766 5733 | ||

| 3400 3681 | ||

| 2766 4670 | ||

| 2766 5686 | ||

| 2766 5015 |

Child development; child abuse

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5709 | ||

| 2766 5760 | ||

| 2766 4695 |

Family studies; family violence; family therapy; marriage; parent education

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5709 | ||

| 2766 5652 | ||

| 2766 7944 | ||

| 2766 5733 | ||

| 2766 4859 | ||

| 2766 5787 | ||

| 3400 3672 |

Positive youth development; youth leadership; career development; guidance and counselling

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5652 | ||

| 3400 3018 | ||

| 2766 7944 | ||

| 2766 4859 | ||

| 2766 5787 | ||

| 2766 5786 | ||

| 2766 7827 | ||

| 2766 5741 |

Youth deviant behaviours; youth and drug; youth and gambling; addiction prevention

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3018 | ||

| 2766 5652 | ||

| 3400 3021 | ||

| 2766 5760 | ||

| 2766 4859 | ||

| 2766 5787 | ||

| 2766 4670 |

Psychology, Mental Health and Health

Applied neuropsychology; social cognition; biological psychology

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3475 | ||

| 2766 7746 | ||

| 2766 5710 |

Culture and mental health; mental health policy and service

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3696 | ||

| 3400 3689 | ||

| 2766 5769 | ||

| 2766 7747 | ||

| 3400 3676 | ||

| 2766 5787 | ||

| 2766 7744 | ||

| 2766 5015 | ||

| 2766 7740 |

Educational psychology; developmental psychology; psychopathology

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3475 | ||

| 2766 5652 | ||

| 2766 5755 | ||

| 2766 4859 | ||

| 2766 5787 |

Environmental psychology; community psychology

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5710 |

Public health; medical anthropology and sociology

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5733 | ||

| 2766 7747 |

Social psychology; cultural psychology

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3696 | ||

| 2766 5710 | ||

| 2766 7744 | ||

| 2766 7740 |

Social Policy, Social Welfare and Community Development

Disaster management and risk reduction

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 3400 3681 | ||

| 2766 5786 |

Housing policy; health policy; labour and welfare policy; ageing and family policy; comparative social policy

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3694 | ||

| 2766 5653 | ||

| 2766 5632 | ||

| 3400 3676 | ||

| 2766 5686 | ||

| 2766 5705 |

Quality of life; social indicators; social stratification; social exclusion/inclusion

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5652 | ||

| 3400 3689 | ||

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5653 | ||

| 2766 4859 | ||

| 2766 5740 |

Third-sector development; social enterprise; social economy; social innovation

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 3400 3676 | ||

| 3400 3492 | ||

| 2766 5790 |

Social Theory, China and Global Social Development

Culture, social technology and digital studies

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5738 | ||

| 3400 3692 | ||

| 2766 4670 | ||

| 2766 5705 | ||

| 2766 5722 |

Gender/sexuality; race/ethnicity and labor studies

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5743 | ||

| 2766 5705 | ||

| 3400 3672 | ||

| 2766 5740 | ||

| 2766 5744 |

Globalisation, migration and social development

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5738 | ||

| 2766 5743 | ||

| 3400 3676 | ||

| 2766 5748 | ||

| 2766 5744 | ||

| 2766 4656 | ||

| 2766 5790 |

Social theory and social philosophy

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5738 | ||

| 3400 3692 | ||

| 2766 5740 | ||

| 2766 5722 |

Urbanisation, rural-urban relations and local governance

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 3400 3689 | ||

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5725 | ||

| 3400 3494 | ||

| 2766 5748 | ||

| 2766 4656 |

Social Work and Human Service Management

Human services management; information-knowledge management

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 5738 | ||

| 3400 3492 |

Indigenization of social work practice; social work education; social work values and ethics

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5786 |

Practice research; program evaluation

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 4553 | ||

| 2766 5769 | ||

| 2766 5786 | ||

| 2766 5750 | ||

| 2766 5015 |

Social work supervision; social work practice

| Supervisor | Tel | |

| 2766 7944 | ||

| 3400 3021 | ||

| 2766 5769 |

The following research centre and research facilities are our platforms for hosting and advancing research collaborations with academic institutions, NGOs, the private sector and government departments locally, overseas and in the Chinese mainland.

Centre for Social Policy and Social Entrepreneurship

China and Global Development Network

Peking University -- The Hong Kong Polytechnic University China Social Work Research Centre

Mental Health Research Centre

Professional Practice and Assessment Centre

Yan Oi Tong Au Suet Ming Child Development Centre

Research Centre for Gerontology and Family Studies

Research Laboratory - Research equipment such as electroencephalography (EEG) for collecting neurological data, BIOPAC system for collecting physiological data like skin conductance, heart rate, and respiration, and Virtual Reality facilities for collecting behavioral data in immersive environments

For enquiries about the programmes, please contact us .

Compulsory - Two Academic Referee's Reports are required.

Compulsory - A standard form must be used for the submission of research proposal. Please click here to download the form.

Compulsory – Please upload all academic qualifications including Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree (if any) according to the University’s admission requirements , also refer to the ‘ Procedures – Guidelines for Submitting Supporting Documents ’ to follow the submission requirements.

Optional

Publications, awards, professional-related community service/qualification (licenses), etc.

Please provide an official letter/document issued by corresponding University to indicate that your Master's degree study contains a significant research component, such as a dissertation.

Haemodynamic and Vascular Disorders

Immunity and Infection

Metabolic and Ocular Disorders

Neuroimaging and Neuropathology

Translational Research in Neuroscience

Translational Research in Musculoskeletal and Sports Science

Translational Research in Better Ageing and Longevity

Translational Research in Primary Healthcare

Healthy Ageing through Innovations

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support

Palliative Care in Cancer Trajectory and Survivorship

Primary Health Care

Ageing Eye Research

Myopia Research

- PolyU Main Site

- Academic Registry (AR)

- Global Engagement Office (GEO)

- Graduate School (GS)

- Office of Undergraduate Studies (OUS)

- Student Affairs Office (SAO)

- Hong Kong Community College (HKCC)

- School of Professional Education and Executive Development (SPEED)

- School Nominations Direct Admission Scheme (SNDAS)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Admissions. The Department of Philosophy typically receives over 400 applications each year. We ordinarily matriculate an entering class of five to six doctoral students. Although the number of qualified applicants exceeds the number of offers the department can make, we invite all who would like to study Philosophy at Harvard to apply.