- Open access

- Published: 27 June 2011

The case study approach

- Sarah Crowe 1 ,

- Kathrin Cresswell 2 ,

- Ann Robertson 2 ,

- Guro Huby 3 ,

- Anthony Avery 1 &

- Aziz Sheikh 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 11 , Article number: 100 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

796k Accesses

1111 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 – 7 ].

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables 2 , 3 and 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 – 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables 2 and 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)

The decision on how to select the case(s) to study is a very important one that merits some reflection. In an intrinsic case study, the case is selected on its own merits[ 8 ]. The case is selected not because it is representative of other cases, but because of its uniqueness, which is of genuine interest to the researchers. This was, for example, the case in our study of the recruitment of minority ethnic participants into asthma research (Table 1 ) as our earlier work had demonstrated the marginalisation of minority ethnic people with asthma, despite evidence of disproportionate asthma morbidity[ 14 , 15 ]. In another example of an intrinsic case study, Hellstrom et al.[ 16 ] studied an elderly married couple living with dementia to explore how dementia had impacted on their understanding of home, their everyday life and their relationships.

For an instrumental case study, selecting a "typical" case can work well[ 8 ]. In contrast to the intrinsic case study, the particular case which is chosen is of less importance than selecting a case that allows the researcher to investigate an issue or phenomenon. For example, in order to gain an understanding of doctors' responses to health policy initiatives, Som undertook an instrumental case study interviewing clinicians who had a range of responsibilities for clinical governance in one NHS acute hospital trust[ 17 ]. Sampling a "deviant" or "atypical" case may however prove even more informative, potentially enabling the researcher to identify causal processes, generate hypotheses and develop theory.

In collective or multiple case studies, a number of cases are carefully selected. This offers the advantage of allowing comparisons to be made across several cases and/or replication. Choosing a "typical" case may enable the findings to be generalised to theory (i.e. analytical generalisation) or to test theory by replicating the findings in a second or even a third case (i.e. replication logic)[ 1 ]. Yin suggests two or three literal replications (i.e. predicting similar results) if the theory is straightforward and five or more if the theory is more subtle. However, critics might argue that selecting 'cases' in this way is insufficiently reflexive and ill-suited to the complexities of contemporary healthcare organisations.

The selected case study site(s) should allow the research team access to the group of individuals, the organisation, the processes or whatever else constitutes the chosen unit of analysis for the study. Access is therefore a central consideration; the researcher needs to come to know the case study site(s) well and to work cooperatively with them. Selected cases need to be not only interesting but also hospitable to the inquiry [ 8 ] if they are to be informative and answer the research question(s). Case study sites may also be pre-selected for the researcher, with decisions being influenced by key stakeholders. For example, our selection of case study sites in the evaluation of the implementation and adoption of electronic health record systems (see Table 3 ) was heavily influenced by NHS Connecting for Health, the government agency that was responsible for overseeing the National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT)[ 5 ]. This prominent stakeholder had already selected the NHS sites (through a competitive bidding process) to be early adopters of the electronic health record systems and had negotiated contracts that detailed the deployment timelines.

It is also important to consider in advance the likely burden and risks associated with participation for those who (or the site(s) which) comprise the case study. Of particular importance is the obligation for the researcher to think through the ethical implications of the study (e.g. the risk of inadvertently breaching anonymity or confidentiality) and to ensure that potential participants/participating sites are provided with sufficient information to make an informed choice about joining the study. The outcome of providing this information might be that the emotive burden associated with participation, or the organisational disruption associated with supporting the fieldwork, is considered so high that the individuals or sites decide against participation.

In our example of evaluating implementations of electronic health record systems, given the restricted number of early adopter sites available to us, we sought purposively to select a diverse range of implementation cases among those that were available[ 5 ]. We chose a mixture of teaching, non-teaching and Foundation Trust hospitals, and examples of each of the three electronic health record systems procured centrally by the NPfIT. At one recruited site, it quickly became apparent that access was problematic because of competing demands on that organisation. Recognising the importance of full access and co-operative working for generating rich data, the research team decided not to pursue work at that site and instead to focus on other recruited sites.

Collecting the data

In order to develop a thorough understanding of the case, the case study approach usually involves the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative (e.g. questionnaires, audits and analysis of routinely collected healthcare data) and more commonly qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups and observations). The use of multiple sources of data (data triangulation) has been advocated as a way of increasing the internal validity of a study (i.e. the extent to which the method is appropriate to answer the research question)[ 8 , 18 – 21 ]. An underlying assumption is that data collected in different ways should lead to similar conclusions, and approaching the same issue from different angles can help develop a holistic picture of the phenomenon (Table 2 )[ 4 ].

Brazier and colleagues used a mixed-methods case study approach to investigate the impact of a cancer care programme[ 22 ]. Here, quantitative measures were collected with questionnaires before, and five months after, the start of the intervention which did not yield any statistically significant results. Qualitative interviews with patients however helped provide an insight into potentially beneficial process-related aspects of the programme, such as greater, perceived patient involvement in care. The authors reported how this case study approach provided a number of contextual factors likely to influence the effectiveness of the intervention and which were not likely to have been obtained from quantitative methods alone.

In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed (e.g. the nature of different cancer care programmes), before considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (e.g. to explore why one programme is more effective than another). It is important that data sources from different cases are, where possible, broadly comparable for this purpose even though they may vary in nature and depth.

Analysing, interpreting and reporting case studies

Making sense and offering a coherent interpretation of the typically disparate sources of data (whether qualitative alone or together with quantitative) is far from straightforward. Repeated reviewing and sorting of the voluminous and detail-rich data are integral to the process of analysis. In collective case studies, it is helpful to analyse data relating to the individual component cases first, before making comparisons across cases. Attention needs to be paid to variations within each case and, where relevant, the relationship between different causes, effects and outcomes[ 23 ]. Data will need to be organised and coded to allow the key issues, both derived from the literature and emerging from the dataset, to be easily retrieved at a later stage. An initial coding frame can help capture these issues and can be applied systematically to the whole dataset with the aid of a qualitative data analysis software package.

The Framework approach is a practical approach, comprising of five stages (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) , to managing and analysing large datasets particularly if time is limited, as was the case in our study of recruitment of South Asians into asthma research (Table 1 )[ 3 , 24 ]. Theoretical frameworks may also play an important role in integrating different sources of data and examining emerging themes. For example, we drew on a socio-technical framework to help explain the connections between different elements - technology; people; and the organisational settings within which they worked - in our study of the introduction of electronic health record systems (Table 3 )[ 5 ]. Our study of patient safety in undergraduate curricula drew on an evaluation-based approach to design and analysis, which emphasised the importance of the academic, organisational and practice contexts through which students learn (Table 4 )[ 6 ].

Case study findings can have implications both for theory development and theory testing. They may establish, strengthen or weaken historical explanations of a case and, in certain circumstances, allow theoretical (as opposed to statistical) generalisation beyond the particular cases studied[ 12 ]. These theoretical lenses should not, however, constitute a strait-jacket and the cases should not be "forced to fit" the particular theoretical framework that is being employed.

When reporting findings, it is important to provide the reader with enough contextual information to understand the processes that were followed and how the conclusions were reached. In a collective case study, researchers may choose to present the findings from individual cases separately before amalgamating across cases. Care must be taken to ensure the anonymity of both case sites and individual participants (if agreed in advance) by allocating appropriate codes or withholding descriptors. In the example given in Table 3 , we decided against providing detailed information on the NHS sites and individual participants in order to avoid the risk of inadvertent disclosure of identities[ 5 , 25 ].

What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided?

The case study approach is, as with all research, not without its limitations. When investigating the formal and informal ways undergraduate students learn about patient safety (Table 4 ), for example, we rapidly accumulated a large quantity of data. The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted on the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources. This highlights a more general point of the importance of avoiding the temptation to collect as much data as possible; adequate time also needs to be set aside for data analysis and interpretation of what are often highly complex datasets.

Case study research has sometimes been criticised for lacking scientific rigour and providing little basis for generalisation (i.e. producing findings that may be transferable to other settings)[ 1 ]. There are several ways to address these concerns, including: the use of theoretical sampling (i.e. drawing on a particular conceptual framework); respondent validation (i.e. participants checking emerging findings and the researcher's interpretation, and providing an opinion as to whether they feel these are accurate); and transparency throughout the research process (see Table 8 )[ 8 , 18 – 21 , 23 , 26 ]. Transparency can be achieved by describing in detail the steps involved in case selection, data collection, the reasons for the particular methods chosen, and the researcher's background and level of involvement (i.e. being explicit about how the researcher has influenced data collection and interpretation). Seeking potential, alternative explanations, and being explicit about how interpretations and conclusions were reached, help readers to judge the trustworthiness of the case study report. Stake provides a critique checklist for a case study report (Table 9 )[ 8 ].

Conclusions

The case study approach allows, amongst other things, critical events, interventions, policy developments and programme-based service reforms to be studied in detail in a real-life context. It should therefore be considered when an experimental design is either inappropriate to answer the research questions posed or impossible to undertake. Considering the frequency with which implementations of innovations are now taking place in healthcare settings and how well the case study approach lends itself to in-depth, complex health service research, we believe this approach should be more widely considered by researchers. Though inherently challenging, the research case study can, if carefully conceptualised and thoughtfully undertaken and reported, yield powerful insights into many important aspects of health and healthcare delivery.

Yin RK: Case study research, design and method. 2009, London: Sage Publications Ltd., 4

Google Scholar

Keen J, Packwood T: Qualitative research; case study evaluation. BMJ. 1995, 311: 444-446.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge M, Car J, et al: Facilitating the Recruitment of Minority Ethnic People into Research: Qualitative Case Study of South Asians and Asthma. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (10): 1-11.

Article Google Scholar

Pinnock H, Huby G, Powell A, Kielmann T, Price D, Williams S, et al: The process of planning, development and implementation of a General Practitioner with a Special Interest service in Primary Care Organisations in England and Wales: a comparative prospective case study. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). 2008, [ http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/99-final-report.pdf ]

Robertson A, Cresswell K, Takian A, Petrakaki D, Crowe S, Cornford T, et al: Prospective evaluation of the implementation and adoption of NHS Connecting for Health's national electronic health record in secondary care in England: interim findings. BMJ. 2010, 41: c4564-

Pearson P, Steven A, Howe A, Sheikh A, Ashcroft D, Smith P, the Patient Safety Education Study Group: Learning about patient safety: organisational context and culture in the education of healthcare professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010, 15: 4-10. 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009052.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

van Harten WH, Casparie TF, Fisscher OA: The evaluation of the introduction of a quality management system: a process-oriented case study in a large rehabilitation hospital. Health Policy. 2002, 60 (1): 17-37. 10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00187-7.

Stake RE: The art of case study research. 1995, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Sheikh A, Smeeth L, Ashcroft R: Randomised controlled trials in primary care: scope and application. Br J Gen Pract. 2002, 52 (482): 746-51.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

King G, Keohane R, Verba S: Designing Social Inquiry. 1996, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Doolin B: Information technology as disciplinary technology: being critical in interpretative research on information systems. Journal of Information Technology. 1998, 13: 301-311. 10.1057/jit.1998.8.

George AL, Bennett A: Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. 2005, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Eccles M, the Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG): Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implementation Science. 2006, 1: 1-8. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Levy M, Fletcher M, Barnes G, Durham SR, Sheikh A: Ethnic variations in UK asthma frequency, morbidity, and health-service use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9456): 312-7.

Sheikh A, Panesar SS, Lasserson T, Netuveli G: Recruitment of ethnic minorities to asthma studies. Thorax. 2004, 59 (7): 634-

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U: 'We do things together': A case study of 'couplehood' in dementia. Dementia. 2005, 4: 7-22. 10.1177/1471301205049188.

Som CV: Nothing seems to have changed, nothing seems to be changing and perhaps nothing will change in the NHS: doctors' response to clinical governance. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2005, 18: 463-477. 10.1108/09513550510608903.

Lincoln Y, Guba E: Naturalistic inquiry. 1985, Newbury Park: Sage Publications

Barbour RS: Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?. BMJ. 2001, 322: 1115-1117. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

Mays N, Pope C: Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000, 320: 50-52. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50.

Mason J: Qualitative researching. 2002, London: Sage

Brazier A, Cooke K, Moravan V: Using Mixed Methods for Evaluating an Integrative Approach to Cancer Care: A Case Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008, 7: 5-17. 10.1177/1534735407313395.

Miles MB, Huberman M: Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 1994, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 2

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N: Analysing qualitative data. Qualitative research in health care. BMJ. 2000, 320: 114-116. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114.

Cresswell KM, Worth A, Sheikh A: Actor-Network Theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010, 10 (1): 67-10.1186/1472-6947-10-67.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Malterud K: Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001, 358: 483-488. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Yin R: Case study research: design and methods. 1994, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing, 2

Yin R: Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999, 34: 1209-1224.

Green J, Thorogood N: Qualitative methods for health research. 2009, Los Angeles: Sage, 2

Howcroft D, Trauth E: Handbook of Critical Information Systems Research, Theory and Application. 2005, Cheltenham, UK: Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar

Book Google Scholar

Blakie N: Approaches to Social Enquiry. 1993, Cambridge: Polity Press

Doolin B: Power and resistance in the implementation of a medical management information system. Info Systems J. 2004, 14: 343-362. 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2004.00176.x.

Bloomfield BP, Best A: Management consultants: systems development, power and the translation of problems. Sociological Review. 1992, 40: 533-560.

Shanks G, Parr A: Positivist, single case study research in information systems: A critical analysis. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems. 2003, Naples

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/100/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants and colleagues who contributed to the individual case studies that we have drawn on. This work received no direct funding, but it has been informed by projects funded by Asthma UK, the NHS Service Delivery Organisation, NHS Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme, and Patient Safety Research Portfolio. We would also like to thank the expert reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. Our thanks are also due to Dr. Allison Worth who commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Primary Care, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Sarah Crowe & Anthony Avery

Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Kathrin Cresswell, Ann Robertson & Aziz Sheikh

School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sarah Crowe .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AS conceived this article. SC, KC and AR wrote this paper with GH, AA and AS all commenting on various drafts. SC and AS are guarantors.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A. et al. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 11 , 100 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2010

Accepted : 27 June 2011

Published : 27 June 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case Study Approach

- Electronic Health Record System

- Case Study Design

- Case Study Site

- Case Study Report

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: November 2006

Case Studies: why are they important?

- Julie Solomon 1

Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine volume 3 , page 579 ( 2006 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

9 Citations

Metrics details

Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine is a journal designed to lighten the reading load for busy doctors; why, then, does it include Case Studies? Isn't the case study just a bit of light reading? It depends on what it is designed to do. So, what is the role of the Case Study?

Case Studies should act as instructive examples to people who might encounter similar problems. Ideally, in medicine, Case Studies should detail a particular medical case, describing the background of the patient and any clues the physician picked up (or should have, with hindsight). They should discuss investigations undertaken in order to determine a diagnosis or differentiate between possible diagnoses, and should indicate the course of treatment the patient underwent as a result. As a whole, then, Case Studies should be an informative and useful part of every physician's medical education, both during training and on a continuing basis.

It's debatable whether they always achieve this aim. Many journals publish what are often close to anecdotal reports (if they publish articles on individual cases at all), rather than detailed descriptions of a case; furthermore, the cases described are often esoteric or the conditions present on such an infrequent basis that a physician working outside a teaching-hospital environment would be hard-pressed to apply their new knowledge. It would be difficult, therefore, to say whether any conclusions could confidently be drawn by readers as a result of these reports. Most physicians would probably want to do some extra research—either in the literature or by canvassing opinions of colleagues.

By proposing, peer-reviewing and reading the Case Studies, you and your fellow physicians could gain a broader understanding of clinical diagnoses, treatments and outcomes.

In this light, then, Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine Case Studies have a specific aim: to help established physicians as well as trainees to improve patient care, without adding to their workload. Rather than being merely anecdotal, they include the etiology, diagnosis and management of a case. Importantly, they give an indication of the decision-making process, so that other physicians can apply lateral thinking to their own cases. Decisions on which of a range of treatment options to follow might involve input from the patient, or might be purely objective, but ideally a Case Study should outline why a particular course was followed. Readers should not have to resort to the Internet or to out-of-date textbooks to find basic background information explaining the reasons for approaching the case in that way; the reasons should be fully explained in the article itself.

Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine Case Studies represent an opportunity to spread the benefit of knowledge across the physical boundaries imposed by looking at one case, in one place, at one time. It's not so that fingers can be pointed at 'incorrect' treatment but instead so that geographical differences in practice can be highlighted, for example, or clearer descriptions be reached to explain a case more completely and accurately.

By proposing, peer-reviewing and reading the Case Studies, you and your fellow physicians could gain a broader understanding of clinical diagnoses, treatments and outcomes. So, we're inviting you to contribute to the further education of your colleagues. Will you meet the challenge?

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Assistant Publisher of the Nature Clinical Practice journals,

Julie Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Solomon, J. Case Studies: why are they important?. Nat Rev Cardiol 3 , 579 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio0704

Download citation

Issue Date : November 2006

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio0704

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Learning together for better health using an evidence-based Learning Health System framework: a case study in stroke

- Helena Teede 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Dominique A. Cadilhac 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Tara Purvis 3 ,

- Monique F. Kilkenny 3 , 4 ,

- Bruce C.V. Campbell 4 , 5 , 6 ,

- Coralie English 7 ,

- Alison Johnson 2 ,

- Emily Callander 1 ,

- Rohan S. Grimley 8 , 9 ,

- Christopher Levi 10 ,

- Sandy Middleton 11 , 12 ,

- Kelvin Hill 13 &

- Joanne Enticott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4480-5690 1

BMC Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 198 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1281 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

In the context of expanding digital health tools, the health system is ready for Learning Health System (LHS) models. These models, with proper governance and stakeholder engagement, enable the integration of digital infrastructure to provide feedback to all relevant parties including clinicians and consumers on performance against best practice standards, as well as fostering innovation and aligning healthcare with patient needs. The LHS literature primarily includes opinion or consensus-based frameworks and lacks validation or evidence of benefit. Our aim was to outline a rigorously codesigned, evidence-based LHS framework and present a national case study of an LHS-aligned national stroke program that has delivered clinical benefit.

Current core components of a LHS involve capturing evidence from communities and stakeholders (quadrant 1), integrating evidence from research findings (quadrant 2), leveraging evidence from data and practice (quadrant 3), and generating evidence from implementation (quadrant 4) for iterative system-level improvement. The Australian Stroke program was selected as the case study as it provides an exemplar of how an iterative LHS works in practice at a national level encompassing and integrating evidence from all four LHS quadrants. Using this case study, we demonstrate how to apply evidence-based processes to healthcare improvement and embed real-world research for optimising healthcare improvement. We emphasize the transition from research as an endpoint, to research as an enabler and a solution for impact in healthcare improvement.

Conclusions

The Australian Stroke program has nationally improved stroke care since 2007, showcasing the value of integrated LHS-aligned approaches for tangible impact on outcomes. This LHS case study is a practical example for other health conditions and settings to follow suit.

Peer Review reports

Internationally, health systems are facing a crisis, driven by an ageing population, increasing complexity, multi-morbidity, rapidly advancing health technology and rising costs that threaten sustainability and mandate transformation and improvement [ 1 , 2 ]. Although research has generated solutions to healthcare challenges, and the advent of big data and digital health holds great promise, entrenched siloes and poor integration of knowledge generation, knowledge implementation and healthcare delivery between stakeholders, curtails momentum towards, and consistent attainment of, evidence-and value-based care [ 3 ]. This is compounded by the short supply of research and innovation leadership within the healthcare sector, and poorly integrated and often inaccessible health data systems, which have crippled the potential to deliver on digital-driven innovation [ 4 ]. Current approaches to healthcare improvement are also often isolated with limited sustainability, scale-up and impact [ 5 ].

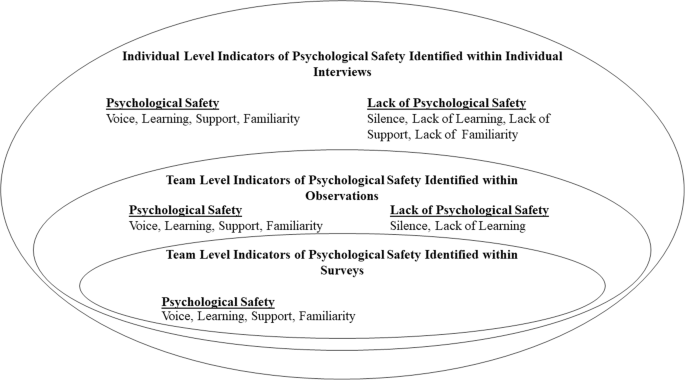

Evidence suggests that integration and partnership across academic and healthcare delivery stakeholders are key to progress, including those with lived experience and their families (referred to here as consumers and community), diverse disciplines (both research and clinical), policy makers and funders. Utilization of evidence from research and evidence from practice including data from routine care, supported by implementation research, are key to sustainably embedding improvement and optimising health care and outcomes. A strategy to achieve this integration is through the Learning Health System (LHS) (Fig. 1 ) [ 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Although there are numerous publications on LHS approaches [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ], many focus on research perspectives and data, most do not demonstrate tangible healthcare improvement or better health outcomes. [ 6 ]

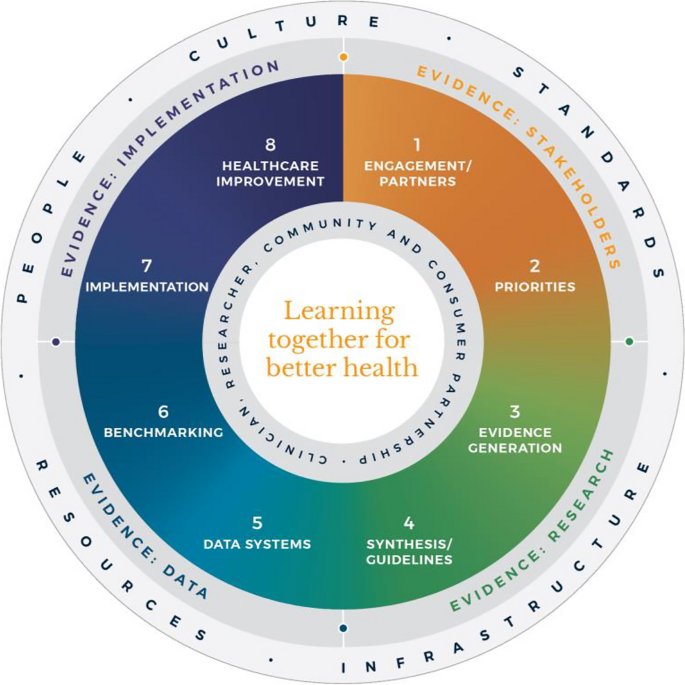

Monash Learning Health System: The Learn Together for Better Health Framework developed by Monash Partners and Monash University (from Enticott et al. 2021 [ 7 ]). Four evidence quadrants: Q1 (orange) is evidence from stakeholders; Q2 (green) is evidence from research; Q3 (light blue) is evidence from data; and, Q4 (dark blue) is evidence from implementation and healthcare improvement

In developed nations, it has been estimated that 60% of care provided aligns with the evidence base, 30% is low value and 10% is potentially harmful [ 13 ]. In some areas, clinical advances have been rapid and research and evidence have paved the way for dramatic improvement in outcomes, mandating rapid implementation of evidence into healthcare (e.g. polio and COVID-19 vaccines). However, healthcare improvement is challenging and slow [ 5 ]. Health systems are highly complex in their design, networks and interacting components, and change is difficult to enact, sustain and scale up. [ 3 ] New effective strategies are needed to meet community needs and deliver evidence-based and value-based care, which reorients care from serving the provider, services and system, towards serving community needs, based on evidence and quality. It goes beyond cost to encompass patient and provider experience, quality care and outcomes, efficiency and sustainability [ 2 , 6 ].

The costs of stroke care are expected to rise rapidly in the next decades, unless improvements in stroke care to reduce the disabling effects of strokes can be successfully developed and implemented [ 14 ]. Here, we briefly describe the Monash LHS framework (Fig. 1 ) [ 2 , 6 , 7 ] and outline an exemplar case in order to demonstrate how to apply evidence-based processes to healthcare improvement and embed real-world research for optimising healthcare. The Australian LHS exemplar in stroke care has driven nationwide improvement in stroke care since 2007.

An evidence-based Learning Health System framework

In Australia, members of this author group (HT, AJ, JE) have rigorously co-developed an evidence-based LHS framework, known simply as the Monash LHS [ 7 ]. The Monash LHS was designed to support sustainable, iterative and continuous robust benefit of improved clinical outcomes. It was created with national engagement in order to be applicable to Australian settings. Through this rigorous approach, core LHS principles and components have been established (Fig. 1 ). Evidence shows that people/workforce, culture, standards, governance and resources were all key to an effective LHS [ 2 , 6 ]. Culture is vital including trust, transparency, partnership and co-design. Key processes include legally compliant data sharing, linkage and governance, resources, and infrastructure [ 4 ]. The Monash LHS integrates disparate and often siloed stakeholders, infrastructure and expertise to ‘Learn Together for Better Health’ [ 7 ] (Fig. 1 ). This integrates (i) evidence from community and stakeholders including priority areas and outcomes; (ii) evidence from research and guidelines; (iii) evidence from practice (from data) with advanced analytics and benchmarking; and (iv) evidence from implementation science and health economics. Importantly, it starts with the problem and priorities of key stakeholders including the community, health professionals and services and creates an iterative learning system to address these. The following case study was chosen as it is an exemplar of how a Monash LHS-aligned national stroke program has delivered clinical benefit.

Australian Stroke Learning Health System

Internationally, the application of LHS approaches in stroke has resulted in improved stroke care and outcomes [ 12 ]. For example, in Canada a sustained decrease in 30-day in-hospital mortality has been found commensurate with an increase in resources to establish the multifactorial stroke system intervention for stroke treatment and prevention [ 15 ]. Arguably, with rapid advances in evidence and in the context of an ageing population with high cost and care burden and substantive impacts on quality of life, stroke is an area with a need for rapid research translation into evidence-based and value-based healthcare improvement. However, a recent systematic review found that the existing literature had few comprehensive examples of LHS adoption [ 12 ]. Although healthcare improvement systems and approaches were described, less is known about patient-clinician and stakeholder engagement, governance and culture, or embedding of data informatics into everyday practice to inform and drive improvement [ 12 ]. For example, in a recent review of quality improvement collaborations, it was found that although clinical processes in stroke care are improved, their short-term nature means there is uncertainty about sustainability and impacts on patient outcomes [ 16 ]. Table 1 provides the main features of the Australian Stroke LHS based on the four core domains and eight elements of the Learning Together for Better Health Framework described in Fig. 1 . The features are further expanded on in the following sections.

Evidence from stakeholders (LHS quadrant 1, Fig. 1 )

Engagement, partners and priorities.

Within the stroke field, there have been various support mechanisms to facilitate an LHS approach including partnership and broad stakeholder engagement that includes clinical networks and policy makers from different jurisdictions. Since 2008, the Australian Stroke Coalition has been co-led by the Stroke Foundation, a charitable consumer advocacy organisation, and Stroke Society of Australasia a professional society with membership covering academics and multidisciplinary clinician networks, that are collectively working to improve stroke care ( https://australianstrokecoalition.org.au/ ). Surveys, focus groups and workshops have been used for identifying priorities from stakeholders. Recent agreed priorities have been to improve stroke care and strengthen the voice for stroke care at a national ( https://strokefoundation.org.au/ ) and international level ( https://www.world-stroke.org/news-and-blog/news/world-stroke-organization-tackle-gaps-in-access-to-quality-stroke-care ), as well as reduce duplication amongst stakeholders. This activity is built on a foundation and culture of research and innovation embedded within the stroke ‘community of practice’. Consumers, as people with lived experience of stroke are important members of the Australian Stroke Coalition, as well as representatives from different clinical colleges. Consumers also provide critical input to a range of LHS activities via the Stroke Foundation Consumer Council, Stroke Living Guidelines committees, and the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR) Steering Committee (described below).

Evidence from research (LHS quadrant 2, Fig. 1 )

Advancement of the evidence for stroke interventions and synthesis into clinical guidelines.

To implement best practice, it is crucial to distil the large volume of scientific and trial literature into actionable recommendations for clinicians to use in practice [ 24 ]. The first Australian clinical guidelines for acute stroke were produced in 2003 following the increasing evidence emerging for prevention interventions (e.g. carotid endarterectomy, blood pressure lowering), acute medical treatments (intravenous thrombolysis, aspirin within 48 h of ischemic stroke), and optimised hospital management (care in dedicated stroke units by a specialised and coordinated multidisciplinary team) [ 25 ]. Importantly, a number of the innovations were developed, researched and proven effective by key opinion leaders embedded in the Australian stroke care community. In 2005, the clinical guidelines for Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery [ 26 ] were produced, with subsequent merged guidelines periodically updated. However, the traditional process of periodic guideline updates is challenging for end users when new research can render recommendations redundant and this lack of currency erodes stakeholder trust [ 27 ]. In response to this challenge the Stroke Foundation and Cochrane Australia entered a pioneering project to produce the first electronic ‘living’ guidelines globally [ 20 ]. Major shifts in the evidence for reperfusion therapies (e.g. extended time-window intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular clot retrieval), among other advances, were able to be converted into new recommendations, approved by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council within a few months of publication. Feedback on this process confirmed the increased use and trust in the guidelines by clinicians. The process informed other living guidelines programs, including the successful COVID-19 clinical guidelines [ 28 ].

However, best practice clinical guideline recommendations are necessary but insufficient for healthcare improvement and nesting these within an LHS with stakeholder partnership, enables implementation via a range of proven methods, including audit and feedback strategies [ 29 ].

Evidence from data and practice (LHS quadrant 3, Fig. 1 )

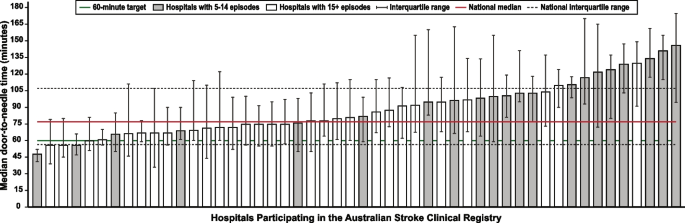

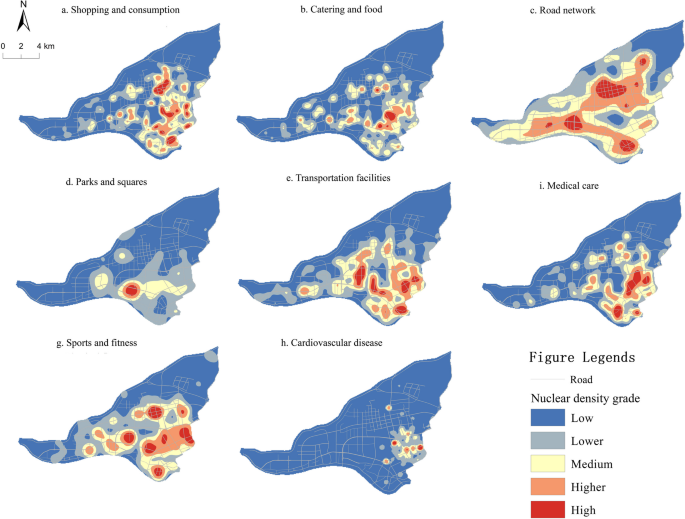

Data systems and benchmarking : revealing the disparities in care between health services. A national system for standardized stroke data collection was established as the National Stroke Audit program in 2007 by the Stroke Foundation [ 30 ] following various state-level programs (e.g. New South Wales Audit) [ 31 ] to identify evidence-practice gaps and prioritise improvement efforts to increase access to stroke units and other acute treatments [ 32 ]. The Audit program alternates each year between acute (commencing in 2007) and rehabilitation in-patient services (commencing in 2008). The Audit program provides a ‘deep dive’ on the majority of recommendations in the clinical guidelines whereby participating hospitals provide audits of up to 40 consecutive patient medical records and respond to a survey about organizational resources to manage stroke. In 2009, the AuSCR was established to provide information on patients managed in acute hospitals based on a small subset of quality processes of care linked to benchmarked reports of performance (Fig. 2 ) [ 33 ]. In this way, the continuous collection of high-priority processes of stroke care could be regularly collected and reviewed to guide improvement to care [ 34 ]. Plus clinical quality registry programs within Australia have shown a meaningful return on investment attributed to enhanced survival, improvements in quality of life and avoided costs of treatment or hospital stay [ 35 ].

Example performance report from the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry: average door-to-needle time in providing intravenous thrombolysis by different hospitals in 2021 [ 36 ]. Each bar in the figure represents a single hospital

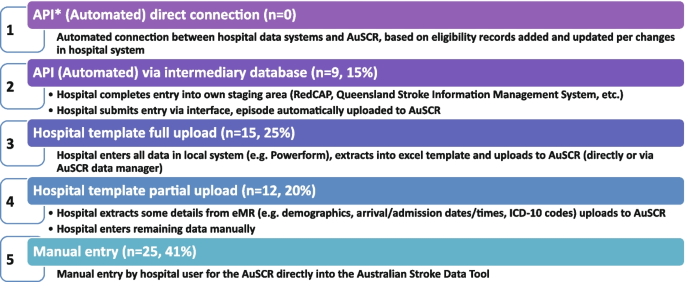

The Australian Stroke Coalition endorsed the creation of an integrated technological solution for collecting data through a single portal for multiple programs in 2013. In 2015, the Stroke Foundation, AuSCR consortium, and other relevant groups cooperated to design an integrated data management platform (the Australian Stroke Data Tool) to reduce duplication of effort for hospital staff in the collection of overlapping variables in the same patients [ 19 ]. Importantly, a national data dictionary then provided the common data definitions to facilitate standardized data capture. Another important feature of AuSCR is the collection of patient-reported outcome surveys between 90 and 180 days after stroke, and annual linkage with national death records to ascertain survival status [ 33 ]. To support a LHS approach, hospitals that participate in AuSCR have access to a range of real-time performance reports. In efforts to minimize the burden of data collection in the AuSCR, interoperability approaches to import data directly from hospital or state-level managed stroke databases have been established (Fig. 3 ); however, the application has been variable and 41% of hospitals still manually enter all their data.

Current status of automated data importing solutions in the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry, 2022, with ‘ n ’ representing the number of hospitals. AuSCR, Australian Stroke Clinical Registry; AuSDaT, Australian Stroke Data Tool; API, Application Programming Interface; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; RedCAP, Research Electronic Data Capture; eMR, electronic medical records

For acute stroke care, the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care facilitated the co-design (clinicians, academics, consumers) and publication of the national Acute Stroke Clinical Care Standard in 2015 [ 17 ], and subsequent review [ 18 ]. The indicator set for the Acute Stroke Standard then informed the expansion of the minimum dataset for AuSCR so that hospitals could routinely track their performance. The national Audit program enabled hospitals not involved in the AuSCR to assess their performance every two years against the Acute Stroke Standard. Complementing these efforts, the Stroke Foundation, working with the sector, developed the Acute and Rehabilitation Stroke Services Frameworks to outline the principles, essential elements, models of care and staffing recommendations for stroke services ( https://informme.org.au/guidelines/national-stroke-services-frameworks ). The Frameworks are intended to guide where stroke services should be developed, and monitor their uptake with the organizational survey component of the Audit program.

Evidence from implementation and healthcare improvement (LHS quadrant 4, Fig. 1 )

Research to better utilize and augment data from registries through linkage [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] and to ensure presentation of hospital or service level data are understood by clinicians has ensured advancement in the field for the Australian Stroke LHS [ 41 ]. Importantly, greater insights into whole patient journeys, before and after a stroke, can now enable exploration of value-based care. The LHS and stroke data platform have enabled focused and time-limited projects to create a better understanding of the quality of care in acute or rehabilitation settings [ 22 , 42 , 43 ]. Within stroke, all the elements of an LHS culminate into the ready availability of benchmarked performance data and support for implementation of strategies to address gaps in care.

Implementation research to grow the evidence base for effective improvement interventions has also been a key pillar in the Australian context. These include multi-component implementation interventions to achieve behaviour change for particular aspects of stroke care, [ 22 , 23 , 44 , 45 ] and real-world approaches to augmenting access to hyperacute interventions in stroke through the use of technology and telehealth [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. The evidence from these studies feeds into the living guidelines program and the data collection systems, such as the Audit program or AuSCR, which are then amended to ensure data aligns to recommended care. For example, the use of ‘hyperacute aspirin within the first 48 h of ischemic stroke’ was modified to be ‘hyperacute antiplatelet…’ to incorporate new evidence that other medications or combinations are appropriate to use. Additionally, new datasets have been developed to align with evidence such as the Fever, Sugar, and Swallow variables [ 42 ]. Evidence on improvements in access to best practice care from the acute Audit program [ 50 ] and AuSCR is emerging [ 36 ]. For example, between 2007 and 2017, the odds of receiving intravenous thrombolysis after ischemic stroke increased by 16% 9OR 1.06 95% CI 1.13–1.18) and being managed in a stroke unit by 18% (OR 1.18 95% CI 1.17–1.20). Over this period, the median length of hospital stay for all patients decreased from 6.3 days in 2007 to 5.0 days in 2017 [ 51 ]. When considering the number of additional patients who would receive treatment in 2017 in comparison to 2007 it was estimated that without this additional treatment, over 17,000 healthy years of life would be lost in 2017 (17,786 disability-adjusted life years) [ 51 ]. There is evidence on the cost-effectiveness of different system-focussed strategies to augment treatment access for acute ischemic stroke (e.g. Victorian Stroke Telemedicine program [ 52 ] and Melbourne Mobile Stroke Unit ambulance [ 53 ]). Reciprocally, evidence from the national Rehabilitation Audit, where the LHS approach has been less complete or embedded, has shown fewer areas of healthcare improvement over time [ 51 , 54 ].

Within the field of stroke in Australia, there is indirect evidence that the collective efforts that align to establishing the components of a LHS have had an impact. Overall, the age-standardised rate of stroke events has reduced by 27% between 2001 and 2020, from 169 to 124 events per 100,000 population. Substantial declines in mortality rates have been reported since 1980. Commensurate with national clinical guidelines being updated in 2007 and the first National Stroke Audit being undertaken in 2007, the mortality rates for men (37.4 deaths per 100,000) and women (36.1 deaths per 100,0000 has declined to 23.8 and 23.9 per 100,000, respectively in 2021 [ 55 ].

Underpinning the LHS with the integration of the four quadrants of evidence from stakeholders, research and guidelines, practice and implementation, and core LHS principles have been addressed. Leadership and governance have been important, and programs have been established to augment workforce training and capacity building in best practice professional development. Medical practitioners are able to undertake courses and mentoring through the Australasian Stroke Academy ( http://www.strokeacademy.com.au/ ) while nurses (and other health professionals) can access teaching modules in stroke care from the Acute Stroke Nurses Education Network ( https://asnen.org/ ). The Association of Neurovascular Clinicians offers distance-accessible education and certification to develop stroke expertise for interdisciplinary professionals, including advanced stroke co-ordinator certification ( www.anvc.org ). Consumer initiative interventions are also used in the design of the AuSCR Public Summary Annual reports (available at https://auscr.com.au/about/annual-reports/ ) and consumer-related resources related to the Living Guidelines ( https://enableme.org.au/resources ).

The important success factors and lessons from stroke as a national exemplar LHS in Australia include leadership, culture, workforce and resources integrated with (1) established and broad partnerships across the academic-clinical sector divide and stakeholder engagement; (2) the living guidelines program; (3) national data infrastructure, including a national data dictionary that provides the common data framework to support standardized data capture; (4) various implementation strategies including benchmarking and feedback as well as engagement strategies targeting different levels of the health system; and (5) implementation and improvement research to advance stroke systems of care and reduce unwarranted variation in practice (Fig. 1 ). Priority opportunities now include the advancement of interoperability with electronic medical records as an area all clinical quality registry’s programs needs to be addressed, as well as providing more dynamic and interactive data dashboards tailored to the need of clinicians and health service executives.

There is a clear mandate to optimise healthcare improvement with big data offering major opportunities for change. However, we have lacked the approaches to capture evidence from the community and stakeholders, to integrate evidence from research, to capture and leverage data or evidence from practice and to generate and build on evidence from implementation using iterative system-level improvement. The LHS provides this opportunity and is shown to deliver impact. Here, we have outlined the process applied to generate an evidence-based LHS and provide a leading exemplar in stroke care. This highlights the value of moving from single-focus isolated approaches/initiatives to healthcare improvement and the benefit of integration to deliver demonstrable outcomes for our funders and key stakeholders — our community. This work provides insight into strategies that can both apply evidence-based processes to healthcare improvement as well as implementing evidence-based practices into care, moving beyond research as an endpoint, to research as an enabler, underpinning delivery of better healthcare.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

Australian Stroke Clinical Registry

Confidence interval

- Learning Health System

World Health Organization. Delivering quality health services . OECD Publishing; 2018.

Enticott J, Braaf S, Johnson A, Jones A, Teede HJ. Leaders’ perspectives on learning health systems: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1087.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Melder A, Robinson T, McLoughlin I, Iedema R, Teede H. An overview of healthcare improvement: Unpacking the complexity for clinicians and managers in a learning health system. Intern Med J. 2020;50:1174–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Alberto IRI, Alberto NRI, Ghosh AK, Jain B, Jayakumar S, Martinez-Martin N, et al. The impact of commercial health datasets on medical research and health-care algorithms. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5:e288–94.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dixon-Woods M. How to improve healthcare improvement—an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods. BMJ. 2019;367: l5514.

Enticott J, Johnson A, Teede H. Learning health systems using data to drive healthcare improvement and impact: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:200.

Enticott JC, Melder A, Johnson A, Jones A, Shaw T, Keech W, et al. A learning health system framework to operationalize health data to improve quality care: An Australian perspective. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:730021.

Dammery G, Ellis LA, Churruca K, Mahadeva J, Lopez F, Carrigan A, et al. The journey to a learning health system in primary care: A qualitative case study utilising an embedded research approach. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24:22.

Foley T, Horwitz L, Zahran R. The learning healthcare project: Realising the potential of learning health systems. 2021. Available from https://learninghealthcareproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/LHS2021report.pdf . Accessed Jan 2024.

Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2013.

Google Scholar

Zurynski Y, Smith CL, Vedovi A, Ellis LA, Knaggs G, Meulenbroeks I, et al. Mapping the learning health system: A scoping review of current evidence - a white paper. 2020:63

Cadilhac DA, Bravata DM, Bettger J, Mikulik R, Norrving B, Uvere E, et al. Stroke learning health systems: A topical narrative review with case examples. Stroke. 2023;54:1148–59.

Braithwaite J, Glasziou P, Westbrook J. The three numbers you need to know about healthcare: The 60–30-10 challenge. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–8.

Article Google Scholar

King D, Wittenberg R, Patel A, Quayyum Z, Berdunov V, Knapp M. The future incidence, prevalence and costs of stroke in the UK. Age Ageing. 2020;49:277–82.

Ganesh A, Lindsay P, Fang J, Kapral MK, Cote R, Joiner I, et al. Integrated systems of stroke care and reduction in 30-day mortality: A retrospective analysis. Neurology. 2016;86:898–904.

Lowther HJ, Harrison J, Hill JE, Gaskins NJ, Lazo KC, Clegg AJ, et al. The effectiveness of quality improvement collaboratives in improving stroke care and the facilitators and barriers to their implementation: A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16:16.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Acute stroke clinical care standard. 2015. Available from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/clinical-care-standards/acute-stroke-clinical-care-standard . Accessed Jan 2024.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Acute stroke clinical care standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2019. Available from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/acute-stroke-clinical-care-standard-evidence-sources . Accessed Jan 2024.

Ryan O, Ghuliani J, Grabsch B, Hill K, G CC, Breen S, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of the Australian Stroke Data Tool (AuSDaT): Comprehensive data capturing for multiple uses. Health Inf Manag. 2022:18333583221117184.

English C, Bayley M, Hill K, Langhorne P, Molag M, Ranta A, et al. Bringing stroke clinical guidelines to life. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:337–9.

English C, Hill K, Cadilhac DA, Hackett ML, Lannin NA, Middleton S, et al. Living clinical guidelines for stroke: Updates, challenges and opportunities. Med J Aust. 2022;216:510–4.

Cadilhac DA, Grimley R, Kilkenny MF, Andrew NE, Lannin NA, Hill K, et al. Multicenter, prospective, controlled, before-and-after, quality improvement study (Stroke123) of acute stroke care. Stroke. 2019;50:1525–30.

Cadilhac DA, Marion V, Andrew NE, Breen SJ, Grabsch B, Purvis T, et al. A stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial to improve adherence to evidence-based practices for acute stroke management. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2022.

Elliott J, Lawrence R, Minx JC, Oladapo OT, Ravaud P, Jeppesen BT, et al. Decision makers need constantly updated evidence synthesis. Nature. 2021;600:383–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

National Stroke Foundation. National guidelines for acute stroke management. Melbourne: National Stroke Foundation; 2003.

National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Melbourne: National Stroke Foundation; 2005.

Phan TG, Thrift A, Cadilhac D, Srikanth V. A plea for the use of systematic review methodology when writing guidelines and timely publication of guidelines. Intern Med J . 2012;42:1369–1371; author reply 1371–1362

Tendal B, Vogel JP, McDonald S, Norris S, Cumpston M, White H, et al. Weekly updates of national living evidence-based guidelines: Methods for the Australian living guidelines for care of people with COVID-19. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;131:11–21.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Harris D, Cadilhac D, Hankey GJ, Hillier S, Kilkenny M, Lalor E. National stroke audit: The Australian experience. Clin Audit. 2010;2:25–31.

Cadilhac DA, Purvis T, Kilkenny MF, Longworth M, Mohr K, Pollack M, et al. Evaluation of rural stroke services: Does implementation of coordinators and pathways improve care in rural hospitals? Stroke. 2013;44:2848–53.

Cadilhac DA, Moss KM, Price CJ, Lannin NA, Lim JY, Anderson CS. Pathways to enhancing the quality of stroke care through national data monitoring systems for hospitals. Med J Aust. 2013;199:650–1.

Cadilhac DA, Lannin NA, Anderson CS, Levi CR, Faux S, Price C, et al. Protocol and pilot data for establishing the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Int J Stroke. 2010;5:217–26.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young J, Odgaard-Jensen J, French S, et al. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2012

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Economic evaluation of clinical quality registries. Final report. . 2016:79

Cadilhac DA, Dalli LL, Morrison J, Lester M, Paice K, Moss K, et al. The Australian Stroke Clinical Registry annual report 2021. Melbourne; 2022. Available from https://auscr.com.au/about/annual-reports/ . Accessed 6 May 2024.

Kilkenny MF, Kim J, Andrew NE, Sundararajan V, Thrift AG, Katzenellenbogen JM, et al. Maximising data value and avoiding data waste: A validation study in stroke research. Med J Aust. 2019;210:27–31.

Eliakundu AL, Smith K, Kilkenny MF, Kim J, Bagot KL, Andrew E, et al. Linking data from the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry with ambulance and emergency administrative data in Victoria. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221102200.

PubMed Google Scholar

Andrew NE, Kim J, Cadilhac DA, Sundararajan V, Thrift AG, Churilov L, et al. Protocol for evaluation of enhanced models of primary care in the management of stroke and other chronic disease (PRECISE): A data linkage healthcare evaluation study. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2019;4:1097.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mosalski S, Shiner CT, Lannin NA, Cadilhac DA, Faux SG, Kim J, et al. Increased relative functional gain and improved stroke outcomes: A linked registry study of the impact of rehabilitation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30: 106015.

Ryan OF, Hancock SL, Marion V, Kelly P, Kilkenny MF, Clissold B, et al. Feedback of aggregate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) data to clinicians and hospital end users: Findings from an Australian codesign workshop process. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e055999.