Think, But How?

What Is a Sound Argument?

Have you ever wanted to disagree with someone’s argument, but you couldn’t find any flaw in it? It’s possible you were facing a sound argument.

An argument is a series of statements that try to prove a point. The statement that the arguer tries to prove is called the conclusion . The statements that try to prove the conclusion are called premises.

Here’s a sample argument:

Premise 1: If it is raining, then the street is wet. Premise 2: It is raining. Conclusion: Therefore, the street is wet.

Above is an example of a series of statements that counts as an argument since it has a premise and conclusion. That’s all it takes for something to be an argument : it needs to have a premise and a conclusion.

A sound argument proves the arguer’s point by providing decisive evidence for the truth of their conclusion.

A sound argument has two features:

The argument has a valid form, and

All the premises are true.

I’m going to talk about these points in order. To understand the valid form, we need to understand the logical form of an argument and the logical form of a statement.

What Is an Argument’s Logical Form?

When we say an argument is valid, we are talking about an argument’s logical form. I wrote about valid arguments and logical forms in this piece here in detail.

Logical forms are like math formulas. Each comprises variables and operators. For example, the math formula “x + x = 2x” comprises a variable ‘x’ and an operator ‘+’. If we were to plug in the value 1 for x, then we would get “1+1 = 2.” Logical forms are similar. The difference is that instead of mathematical operators, logical forms use logical operators, and instead of variables that are filled in with numbers, the variables of logical forms are filled in with statements.

How do you get at the form of an argument? An argument is a series of statements, so to get at the form of an argument, you need to get at the form of the statements that compose it.

The Logical Form of a Statement

Here are a couple of examples of statements: “It is raining.”; “The street is wet.”

Statements can be combined using logical operators such as the following:

Either… or…

… if and only if…

When we combine two or more statements using logical operators, the result is a compound statement.

For example, the statements, “It is raining,” and, “The street is wet,” can be combined by the logical operator ‘and’ to make a compound statement as follows: “It is raining, and the street is wet.” Or they can be combined using ‘if…then…’ as follows: “If it is raining, then the street is wet.”

Here are more examples of statements formed with logical operators: “It is not raining,” “James is tall, or Adam is fast,” “ Either you can go straight, or you can make a right,” “Shawn can win the race if and only if he enters it.”

Now that we understand the logical form of a statement, let’s talk about the logical form of an argument. An argument is composed of statements. The premises and the conclusion of an argument are all statements. So if you want to know the logical form of an argument, you start by identifying the logical form of the statements composing it.

Here’s an example of an argument:

Premise 1: All mammals are animals. Premise 2: All dogs are mammals. Conclusion: Therefore, all dogs are animals.

Here’s the form of the argument:

All M are A All D are M Therefore, all D are A

Logicians have a name for this form of argument. It is a valid deductive argument called a categorical syllogism.

Now, an argument’s form is valid if and only if the truth of the argument’s premises guarantees the truth of its conclusion. If we plug in true premises, in other words, a valid form guarantees a true conclusion.

A valid form is similar to an accurate math formula. For example, in mathematics, if you want to get the area of a circle, you will first get the formula to calculate the area of a circle. In this case, the formula will be “A = π (r)^2.” At this point, all you need to do is plug in the radius r of the circle in the formula to get an accurate result. If you get the accurate radius, then you are guaranteed an accurate area.

The categorical syllogism is a valid form because if the two premises are true then the conclusion has to be true. In other words, if premises 1 and 2 are true, then the conclusion (All dogs are animals) has to be true–it’s impossible for it to be false.

Now that we’ve talked about forms of statements and arguments, let’s talk about what it means for an argument to be a sound argument.

What makes a valid argument into a sound argument?

Now that we understand what a valid argument is, it is easier to understand a sound argument. An argument is sound if and only if it is a valid argument and all the premises are true. Examples of sound arguments include categorical syllogisms whose premises are all true.

In order to determine whether an argument is sound, you need to ask the following two questions.

1. Does this argument have a valid form?

2. Are all the premises true?

Once the answer to both 1 and 2 is yes, then you know it’s a sound argument.

The following argument is another example of categorical syllogism:

Premise 1: All men are mortal. Premise 2: Socrates is a man. Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Let’s look at the above example with two questions in mind to determine whether this argument is sound.

Does this argument has a valid form? Yes. The above form is called a categorical syllogism, and it is a valid form. Logicians have compiled a list of time-tested valid argument forms such as Modus ponens, Modus tollens, and Disjunctive syllogism. Categorical syllogism is one of the most popular forms, and it is a valid form because if the two premises are true then the conclusion has to be true.

Are all the premises true? Yes. Both of the premises above are true. Premises are statements. Statements can be either true or false. A statement is true when the world matches the statement. If I were to say, “2 plus 2 is 4,” then this statement is true since it matches how the world is. If I were to say, “2 plus 2 is 5,” then this statement is false since it doesn’t match how the world is.

If you can’t determine whether the premises are true or false, you can choose to withhold judgment. Withholding judgment means you don’t make a decision to accept or reject a claim . For example, suppose you don’t have decisive evidence for or against this claim: “There is life outside of the earth.” You don’t have to make a decision about whether or not the claim is true. You can withhold your judgment till you get more evidence for or against the claim.

If the answer to questions 1 and 2 is yes, then you know that the above argument is sound. You know that the argument actually proves its point. It actually proves that the conclusion is true.

However, if the answer to question 1 is yes, and you’re withholding judgment about question 2, then at least you know that the argument is a valid argument even if you don’t know whether the argument is sound.

Summary and Conclusion of Sound Argument

An argument is a series of statements that try to prove a point. The statement that the arguer tries to prove is called the conclusion. The statements that try to prove the conclusion are called premises.

Arguments are not true or false. Statements are true or false.

When we say an argument is valid, we are talking about the form of an argument.

An argument is valid if and only if the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion.

Validity is a feature of deductive arguments not inductive arguments.

Logicians have tests for logical consequence and methods for constructing valid deductive arguments.

An argument is sound if and only if it is a valid argument and all the premises are true.

Unsound arguments either don’t have a valid form or they have at least one false premise.

If the premises of an argument are false, then the argument doesn’t prove anything. An argument with even a single false premise doesn’t prove anything.

Knowing how to identify sound arguments is essential to developing critical thinking skills .

Not all invalid forms are fallacies . Inductive arguments are invalid arguments, but they aren’t fallacies. If inductive arguments have true premises, they still give us some reason to think their conclusions are true. They just don’t prove their conclusions. An inductive argument with true premises can still have a false conclusion; it’s just that the conclusion is probably true. An inductive argument with true premises is sometimes called a cogent argument.

Ready for more?

An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better by

Get full access to An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

VALID AND SOUND ARGUMENTS

9.1 VALIDITY AND SOUNDNESS

Validity is a most important concept in critical thinking. A valid argument is one where the conclusion follows logically from the premises. But what does it mean? Here is the official definition:

An argument is valid if and only if there is no logically possible situation in which the premises are true and the conclusion is false.

To put it differently, whenever we have a valid argument, if the premises are all true, then the conclusion must also be true. What this implies is that if you use only valid arguments in your reasoning, as long as you start with true premises, you will never end up with a false conclusion. Here is an example of a valid argument:

This simple argument is obviously valid since it is impossible for the conclusion to be false when the premise is true. However, notice that the validity of the argument can be determined without knowing whether the premise and the conclusion are actually true or not. Validity is about the logical connection between the premises and the conclusion. We might not know how old Marilyn actually is, but it is clear the conclusion follows logically from the premise. The simple argument above will remain valid even if Marilyn is just a baby, in which case the premise and the conclusion are both false. Consider this argument also:

Again the argument is valid—if the ...

Get An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

Pursuing Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

Chapter 2 arguments.

The fundamental tool of the critical thinker is the argument. For a good example of what we are not talking about, consider a bit from a famous sketch by Monty Python’s Flying Circus : 3

2.1 Identifying Arguments

People often use “argument” to refer to a dispute or quarrel between people. In critical thinking, an argument is defined as

A set of statements, one of which is the conclusion and the others are the premises.

There are three important things to remember here:

- Arguments contain statements.

- They have a conclusion.

- They have at least one premise

Arguments contain statements, or declarative sentences. Statements, unlike questions or commands, have a truth value. Statements assert that the world is a particular way; questions do not. For example, if someone asked you what you did after dinner yesterday evening, you wouldn’t accuse them of lying. When the world is the way that the statement says that it is, we say that the statement is true. If the statement is not true, it is false.

One of the statements in the argument is called the conclusion. The conclusion is the statement that is intended to be proved. Consider the following argument:

Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I. Susan did well in Calculus I. So, Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Here the conclusion is that Susan should do well in Calculus II. The other two sentences are premises. Premises are the reasons offered for believing that the conclusion is true.

2.1.1 Standard Form

Now, to make the argument easier to evaluate, we will put it into what is called “standard form.” To put an argument in standard form, write each premise on a separate, numbered line. Draw a line underneath the last premise, the write the conclusion underneath the line.

- Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I.

- Susan did well in Calculus I.

- Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Now that we have the argument in standard form, we can talk about premise 1, premise 2, and all clearly be referring to the same thing.

2.1.2 Indicator Words

Unfortunately, when people present arguments, they rarely put them in standard form. So, we have to decide which statement is intended to be the conclusion, and which are the premises. Don’t make the mistake of assuming that the conclusion comes at the end. The conclusion is often at the beginning of the passage, but could even be in the middle. A better way to identify premises and conclusions is to look for indicator words. Indicator words are words that signal that statement following the indicator is a premise or conclusion. The example above used a common indicator word for a conclusion, ‘so.’ The other common conclusion indicator, as you can probably guess, is ‘therefore.’ This table lists the indicator words you might encounter.

| Therefore | Since |

| So | Because |

| Thus | For |

| Hence | Is implied by |

| Consequently | For the reason that |

| Implies that | |

| It follows that |

Each argument will likely use only one indicator word or phrase. When the conlusion is at the end, it will generally be preceded by a conclusion indicator. Everything else, then, is a premise. When the conclusion comes at the beginning, the next sentence will usually be introduced by a premise indicator. All of the following sentences will also be premises.

For example, here’s our previous argument rewritten to use a premise indicator:

Susan should do well in Calculus II, because Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I, and Susan did well in Calculus I.

Sometimes, an argument will contain no indicator words at all. In that case, the best thing to do is to determine which of the premises would logically follow from the others. If there is one, then it is the conclusion. Here is an example:

Spot is a mammal. All dogs are mammals, and Spot is a dog.

The first sentence logically follows from the others, so it is the conclusion. When using this method, we are forced to assume that the person giving the argument is rational and logical, which might not be true.

2.1.3 Non-Arguments

One thing that complicates our task of identifying arguments is that there are many passages that, although they look like arguments, are not arguments. The most common types are:

- Explanations

- Mere asssertions

- Conditional statements

- Loosely connected statements

Explanations can be tricky, because they often use one of our indicator words. Consider this passage:

Abraham Lincoln died because he was shot.

If this were an argument, then the conclusion would be that Abraham Lincoln died, since the other statement is introduced by a premise indicator. If this is an argument, though, it’s a strange one. Do you really think that someone would be trying to prove that Abraham Lincoln died? Surely everyone knows that he is dead. On the other hand, there might be people who don’t know how he died. This passage does not attempt to prove that something is true, but instead attempts to explain why it is true. To determine if a passage is an explanation or an argument, first find the statement that looks like the conclusion. Next, ask yourself if everyone likely already believes that statement to be true. If the answer to that question is yes, then the passage is an explanation.

Mere assertions are obviously not arguments. If a professor tells you simply that you will not get an A in her course this semester, she has not given you an argument. This is because she hasn’t given you any reasons to believe that the statement is true. If there are no premises, then there is no argument.

Conditional statements are sentences that have the form “If…, then….” A conditional statement asserts that if something is true, then something else would be true also. For example, imagine you are told, “If you have the winning lottery ticket, then you will win ten million dollars.” What is being claimed to be true, that you have the winning lottery ticket, or that you will win ten million dollars? Neither. The only thing claimed is the entire conditional. Conditionals can be premises, and they can be conclusions. They can be parts of arguments, but that cannot, on their own, be arguments themselves.

Finally, consider this passage:

I woke up this morning, then took a shower and got dressed. After breakfast, I worked on chapter 2 of the critical thinking text. I then took a break and drank some more coffee….

This might be a description of my day, but it’s not an argument. There’s nothing in the passage that plays the role of a premise or a conclusion. The passage doesn’t attempt to prove anything. Remember that arguments need a conclusion, there must be something that is the statement to be proved. Lacking that, it simply isn’t an argument, no matter how much it looks like one.

2.2 Evaluating Arguments

The first step in evaluating an argument is to determine what kind of argument it is. We initially categorize arguments as either deductive or inductive, defined roughly in terms of their goals. In deductive arguments, the truth of the premises is intended to absolutely establish the truth of the conclusion. For inductive arguments, the truth of the premises is only intended to establish the probable truth of the conclusion. We’ll focus on deductive arguments first, then examine inductive arguments in later chapters.

Once we have established that an argument is deductive, we then ask if it is valid. To say that an argument is valid is to claim that there is a very special logical relationship between the premises and the conclusion, such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Another way to state this is

An argument is valid if and only if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An argument is invalid if and only if it is not valid.

Note that claiming that an argument is valid is not the same as claiming that it has a true conclusion, nor is it to claim that the argument has true premises. Claiming that an argument is valid is claiming nothing more that the premises, if they were true , would be enough to make the conclusion true. For example, is the following argument valid or not?

- If pigs fly, then an increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

- An increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

The argument is indeed valid. If the two premises were true, then the conclusion would have to be true also. What about this argument?

- All dogs are mammals

- Spot is a mammal.

- Spot is a dog.

In this case, both of the premises are true and the conclusion is true. The question to ask, though, is whether the premises absolutely guarantee that the conclusion is true. The answer here is no. The two premises could be true and the conclusion false if Spot were a cat, whale, etc.

Neither of these arguments are good. The second fails because it is invalid. The two premises don’t prove that the conclusion is true. The first argument is valid, however. So, the premises would prove that the conclusion is true, if those premises were themselves true. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, I guess, considering what would be dropping from the sky) pigs don’t fly.

These examples give us two important ways that deductive arguments can fail. The can fail because they are invalid, or because they have at least one false premise. Of course, these are not mutually exclusive, an argument can be both invalid and have a false premise.

If the argument is valid, and has all true premises, then it is a sound argument. Sound arguments always have true conclusions.

A deductively valid argument with all true premises.

Inductive arguments are never valid, since the premises only establish the probable truth of the conclusion. So, we evaluate inductive arguments according to their strength. A strong inductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises really do make the conclusion probably true. An argument is weak if the truth of the premises fail to establish the probable truth of the conclusion.

There is a significant difference between valid/invalid and strong/weak. If an argument is not valid, then it is invalid. The two categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. There can be no such thing as an argument being more valid than another valid argument. Validity is all or nothing. Inductive strength, however, is on a continuum. A strong inductive argument can be made stronger with the addition of another premise. More evidence can raise the probability of the conclusion. A valid argument cannot be made more valid with an additional premise. Why not? If the argument is valid, then the premises were enough to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Adding another premise won’t give any more guarantee of truth than was already there. If it could, then the guarantee wasn’t absolute before, and the original argument wasn’t valid in the first place.

2.3 Counterexamples

One way to prove an argument to be invalid is to use a counterexample. A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises are true and the conclusion false. Consider the argument above:

By pointing out that Spot could have been a cat, I have told a story in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is false.

Here’s another one:

- If it is raining, then the sidewalks are wet.

- The sidewalks are wet.

- It is raining.

The sprinklers might have been on. If so, then the sidewalks would be wet, even if it weren’t raining.

Counterexamples can be very useful for demonstrating invalidity. Keep in mind, though, that validity can never be proved with the counterexample method. If the argument is valid, then it will be impossible to give a counterexample to it. If you can’t come up with a counterexample, however, that does not prove the argument to be valid. It may only mean that you’re not creative enough.

- An argument is a set of statements; one is the conclusion, the rest are premises.

- The conclusion is the statement that the argument is trying to prove.

- The premises are the reasons offered for believing the conclusion to be true.

- Explanations, conditional sentences, and mere assertions are not arguments.

- Deductive reasoning attempts to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion.

- Inductive reasoning attempts to show that the conclusion is probably true.

- In a valid argument, it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- In an invalid argument, it is possible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- A sound argument is valid and has all true premises.

- An inductively strong argument is one in which the truth of the premises makes the the truth of the conclusion probable.

- An inductively weak argument is one in which the truth of the premises do not make the conclusion probably true.

- A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises of an argument are true and the conclusion is false. Counterexamples can be used to prove that arguments are deductively invalid.

( Cleese and Chapman 1980 ) . ↩︎

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Validity and Soundness

1.7 soundness.

A good argument is not only valid, but also sound. Soundness is defined in terms of validity, so since we have already defined validity, we can now rely on it to define soundness. A sound argument is a valid argument that has all true premises. That means that the conclusion of a sound argument will always be true. Why? Because if an argument is valid, the premises transmit truth to the conclusion on the assumption of the truth of the premises. But if the premises are actually true, as they are in a sound argument, then since all sound arguments are valid, we know that the conclusion of a sound argument is true. Compare the last two Obama examples from the previous section. While the first argument was sound, the second argument was not sound, although it was valid. The relationship between soundness and validity is easy to specify: all sound arguments are valid arguments, but not all valid arguments are sound arguments.

Although soundness is what any argument should aim for, we will not be talking much about soundness in this book. The reason for this is that the only difference between a valid argument and a sound argument is that a sound argument has all true premises. But how do we determine whether the premises of an argument are actually true? Well, there are lots of ways to do that, including using Google to look up an answer, studying the relevant subjects in school, consulting experts on the relevant topics, and so on. But none of these activities have anything to do with logic, per se. The relevant disciplines to consult if you want to know whether a particular statement is true is almost never logic! For example, logic has nothing to say regarding whether or not protozoa are animals or whether there are predators that aren’t in the animal kingdom. In order to learn whether those statements are true, we’d have to consult biology, not logic. Since this is a logic textbook, however, it is best to leave the question of what is empirically true or false to the relevant disciplines that study those topics. And that is why the issue of soundness, while crucial for any good argument, is outside the purview of logic.

1.8 Deductive vs. Inductive arguments

The concepts of validity and soundness that we have introduced apply only to the class of what are called “deductive arguments”. A deductive argument is an argument whose conclusion is supposed to follow from its premises with absolute certainty, thus leaving no possibility that the conclusion doesn’t follow from the premises. For a deductive argument to fail to do this is for it to fail as a deductive argument. In contrast, an inductive argument is an argument whose conclusion is supposed to follow from its premises with a high level of probability, which means that although it is possible that the conclusion doesn’t follow from its premises, it is unlikely that this is the case. Here is an example of an inductive argument:

Tweets is a healthy, normally functioning bird and since most healthy, normally functioning birds fly, Tweets probably flies.

Notice that the conclusion, Tweets probably flies, contains the word “probably.” This is a clear indicator that the argument is supposed to be inductive, not deductive. Here is the argument in standard form:

- Tweets is a healthy, normally functioning bird

- Most healthy, normally functioning birds fly

- Therefore, Tweets probably flies

Given the information provided by the premises, the conclusion does seem to be well supported. That is, the premises do give us a strong reason for accepting the conclusion. This is true even though we can imagine a scenario in which the premises are true and yet the conclusion is false. For example, suppose that we added the following premise:

Tweets is 6 ft tall and can run 30 mph.

Were we to add that premise, the conclusion would no longer be supported by the premises, since any bird that is 6 ft tall and can run 30 mph, is not a kind of bird that can fly. That information leads us to believe that Tweets is an ostrich or emu, which are not kinds of birds that can fly. As this example shows, inductive arguments are defeasible arguments since by adding further information or premises to the argument, we can overturn (defeat) the verdict that the conclusion is well-supported by the premises. Inductive arguments whose premises give us a strong, even if defeasible, reason for accepting the conclusion are called, unsurprisingly, strong inductive arguments . In contrast, an inductive argument that does not provide a strong reason for accepting the conclusion are called weak inductive arguments .

Whereas strong inductive arguments are defeasible, valid deductive arguments aren’t. Suppose that instead of saying that most birds fly, premise 2 said that all birds fly.

- Tweets is a healthy, normally function bird.

- All healthy, normally functioning birds can fly.

- Therefore, Tweets can fly.

This is a valid argument and since it is a valid argument, there are no further premises that we could add that could overturn the argument’s validity. (True, premise 2 is false, but as we’ve seen that is irrelevant to determining whether an argument is valid.) Even if we were to add the premise that Tweets is 6 ft tall and can run 30 mph, it doesn’t overturn the validity of the argument. As soon as we use the universal generalization , “ all healthy, normally function birds can fly,” then when we assume that premise is true and add that Tweets is a healthy, normally functioning bird, it has to follow from those premises that Tweets can fly. This is true even if we add that Tweets is 6 ft tall because then what we have to imagine (in applying our informal test of validity) is a world in which all birds, including those that are 6 ft tall and can run 30 mph, can fly.

Although inductive arguments are an important class of argument that are commonly used every day in many contexts, logic texts tend not to spend as much time with them since we have no agreed upon standard of evaluating them. In contrast, there is an agreed upon standard of evaluation of deductive arguments. We have already seen what that is; it is the concept of validity. In chapter 2 we will learn some precise, formal methods of evaluating deductive arguments. There are no such agreed upon formal methods of evaluation for inductive arguments. This is an area of ongoing research in philosophy. In chapter 3 we will revisit inductive arguments and consider some ways to evaluate inductive arguments.

1.9 Arguments with missing premises

Quite often, an argument will not explicitly state a premise that we can see is needed in order for the argument to be valid. In such a case, we can supply the premise(s) needed in order so make the argument valid. Making missing premises explicit is a central part of reconstructing arguments in standard form. We have already dealt in part with this in the section on paraphrasing, but now that we have introduced the concept of validity, we have a useful tool for knowing when to supply missing premises in our reconstruction of an argument. In some cases, the missing premise will be fairly obvious, as in the following:

Gary is a convicted sex-offender, so Gary is not allowed to work with children.

The premise and conclusion of this argument are straightforward:

- Gary is a convicted sex-offender

- Therefore, Gary is not allowed to work with children (from 1)

However, as stated, the argument is invalid. (Before reading on, see if you can provide a counterexample for this argument. That is, come up with an imaginary scenario in which the premise is true and yet the conclusion is false.) Here is just one counterexample (there could be many): Gary is a convicted sex-offender but the country in which he lives does not restrict convicted sex-offenders from working with children. I don’t know whether there are any such countries, although I suspect there are (and it doesn’t matter for the purpose of validity whether there are or aren’t). In any case, it seems clear that this argument is relying upon a premise that isn’t explicitly stated. We can and should state that premise explicitly in our reconstruction of the standard form argument. But what is the argument’s missing premise? The obvious one is that no sex-offenders are allowed to work with children, but we could also use a more carefully statement like this one:

Where Gary lives , no convicted sex-offenders are allowed to work with children.

It should be obvious why this is a more “careful” statement. It is more careful because it is not so universal in scope, which means that it is easier for the statement to be made true. By relativizing the statement that sex-offenders are not allowed to work with children to the place where Gary lives, we leave open the possibility that other places in the world don’t have this same restriction. So even if there are other places in the world where convicted sex-offenders are allowed to work with children, our statements could still be true since in this place (the place where Gary lives) they aren’t. (For more on strong and weak statements, see section 1.10). So here is the argument in standard form:

- Gary is a convicted sex-offender.

- Where Gary lives, no convicted sex-offenders are allowed to work with children.

- Therefore, Gary is not allowed to work with children. (from 1-2)

This argument is now valid: there is no way for the conclusion to be false, assuming the truth of the premises. This was a fairly simple example where the missing premise needed to make the argument valid was relatively easy to see. As we can see from this example, a missing premise is a premise that the argument needs in order to be as strong as possible. Typically, this means supplying the statement(s) that are needed to make the argument valid. But in addition to making the argument valid, we want to make the argument plausible. This is called “the principle of charity.” The principle of charity states that when reconstructing an argument, you should try to make that argument (whether inductive or deductive) as strong as possible. When it comes to supplying missing premises, this means supplying the most plausible premises needed in order to make the argument either valid (for deductive arguments) or inductively strong (for inductive arguments).

Although in the last example figuring out the missing premise was relatively easy to do, it is not always so easy. Here is an argument whose missing premises are not as easy to determine:

Since children who are raised by gay couples often have psychological and emotional problems, the state should discourage gay couples from raising children.

The conclusion of this argument, that the state should not allow gay marriage, is apparently supported by a single premise, which should be recognizable from the occurrence of the premise indicator, “since.” Thus, our initial reconstruction of the standard form argument looks like this:

- Children who are raised by gay couples often have psychological and emotional problems.

- Therefore, the state should discourage gay couples from raising children.

However, as it stands, this argument is invalid because it depends on certain missing premises. The conclusion of this argument is a normative statement—a statement about whether something ought to be true , relative to some standard of evaluation. Normative statements can be contrasted with descriptive statements, which are simply factual claims about what is true . For example, “Russia does not allow gay couples to raise children” is a descriptive statement. That is, it is simply a claim about what is in fact the case in Russia today. In contrast, “Russia should not allow gay couples to raise children” is a normative statement since it is not a claim about what is true, but what ought to be true, relative to some standard of evaluation (for example, a moral or legal standard). An important idea within philosophy, which is often traced back to the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), is that statements about what ought to be the case (i.e., normative statements) can never be derived from statements about what is the case (i.e., descriptive statements). This is known within philosophy as the is-ought gap. The problem with the above argument is that it attempts to infer a normative statement from a purely descriptive statement, violating the is-ought gap. We can see the problem by constructing a counterexample. Suppose that in society x it is true that children raised by gay couples have psychological problems. However, suppose that in that society people do not accept that the state should do what it can to decrease harm to children. In this case, the conclusion, that the state should discourage gay couples from raising children, does not follow. Thus, we can see that the argument depends on a missing or assumed premise that is not explicitly stated. That missing premise must be a normative statement, in order that we can infer the conclusion, which is also a normative statement. There is an important general lesson here: Many times an argument with a normative conclusion will depend on a normative premise which is not explicitly stated . The missing normative premise of this particular argument seems to be something like this:

- The state should always do what it can to decrease harm to children.

Notice that this is a normative statement, which is indicated by the use of the word “should.” There are many other words that can be used to capture normative statements such as: good, bad, and ought. Thus, we can reconstruct the argument, filling in the missing normative premise like this:

- Therefore, the state should discourage gay couples from raising children. (from 1-2)

However, although the argument is now in better shape, it is still invalid because it is still possible for the premises to be true and yet the conclusion false. In order to show this, we just have to imagine a scenario in which both the premises are true and yet the conclusion is false. Here is one counterexample to the argument (there are many). Suppose that while it is true that children of gay couples often have psychological and emotional problems, the rate of psychological problems in children raised by gay couples is actually lower than in children raised by heterosexual couples. In this case, even if it were true that the state should always do what it can to decrease harm to children, it does not follow that the state should discourage gay couples from raising children. In fact, in the scenario I’ve described, just the opposite would seem to follow: the state should discourage heterosexual couples from raising children.

But even if we suppose that the rate of psychological problems in children of gay couples is higher than in children of heterosexual couples, the conclusion still doesn’t seem to follow. For example, it could be that the reason that children of gay couples have higher rates of psychological problems is that in a society that is not yet accepting of gay couples, children of gay couples will face more teasing, bullying and general lack of acceptance than children of heterosexual couples. If this were true, then the harm to these children isn’t so much due to the fact that their parents are gay as it is to the fact that their community does not accept them. In that case, the state should not necessarily discourage gay couples from raising children. Here is an analogy: At one point in our country’s history (if not still today) it is plausible that the children of black Americans suffered more psychologically and emotionally than the children of white Americans. But for the government to discourage black Americans from raising children would have been unjust, since it is likely that if there was a higher incidence of psychological and emotional problems in black Americans, then it was due to unjust and unequal conditions, not to the black parents, per se. So, to return to our example, the state should only discourage gay couples from raising children if they know that the higher incidence of psychological problems in children of gay couples isn’t the result of any kind of injustice, but is due to the simple fact that the parents are gay.

Thus, one way of making the argument (at least closer to) valid would be to add the following two missing premises:

A. The rate of psychological problems in children of gay couples is higher than in children of heterosexual couples.

B. The higher incidence of psychological problems in children of gay couples is not due to any kind of injustice in society, but to the fact that the parents are gay.

So the reconstructed standard form argument would look like this:

- The rate of psychological problems in children of gay couples is higher than in children of heterosexual couples.

- The higher incidence of psychological problems in children of gay couples is not due to any kind of injustice in society, but to the fact that the parents are gay.

- Therefore, the state should discourage gay couples from raising children. (from 1-4)

In this argument, premises 2-4 are the missing or assumed premises. Their addition makes the argument much stronger, but making them explicit enables us to clearly see what assumptions the argument relies on in order for the argument to be valid. This is useful since we can now clearly see which premises of the argument we may challenge as false. Arguably, premise 4 is false, since the state shouldn’t always do what it can to decrease harm to children. Rather, it should only do so as long as such an action didn’t violate other rights that the state has to protect or create larger harms elsewhere.

The important lesson from this example is that supplying the missing premises of an argument is not always a simple matter. In the example above, I have used the principle of charity to supply missing premises. Mastering this skill is truly an art (rather than a science) since there is never just one correct way of doing it (cf. section 1.5) and because it requires a lot of skilled practice.

Exercise 6: Supply the missing premise or premises needed in order to make the following arguments valid. Try to make the premises as plausible as possible while making the argument valid (which is to apply the principle of charity).

- Ed rides horses. Therefore, Ed is a cowboy.

- Tom was driving over the speed limit. Therefore, Tom was doing something wrong.

- If it is raining then the ground is wet. Therefore, the ground must be wet.

- All elves drink Guinness, which is why Olaf drinks Guinness.

- Mark didn’t invite me to homecoming. Instead, he invited his friend Alexia. So he must like Alexia more than me.

- The watch must be broken because every time I have looked at it, the hands have been in the same place.

- Olaf drank too much Guinness and fell out of his second story apartment window. Therefore, drinking too much Guinness caused Olaf to injure himself.

- Mark jumped into the air. Therefore, Mark landed back on the ground.

- In 2009 in the United States, the net worth of the median white household was $113,149 a year, whereas the net worth of the median black household was $5,677. Therefore, as of 2009, the United States was still a racist nation.

- The temperature of the water is 212 degrees Fahrenheit. Therefore, the water is boiling.

- Capital punishment sometimes takes innocent lives, such as the lives of individuals who were later found to be not guilty. Therefore, we should not allow capital punishment.

- Allowing immigrants to migrate to the U.S. will take working class jobs away from working class folks. Therefore, we should not allow immigrants to migrate to the U.S.

- Prostitution is a fair economic exchange between two consenting adults. Therefore, prostitution should be allowed.

- Colleges are more interested in making money off of their football athletes than in educating them. Therefore, college football ought to be banned.

- Edward received an F in college Algebra. Therefore, Edward should have studied more.

A Brief Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by Southern Alberta Institution of Technology (SAIT) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

2 Logic and the Study of Arguments

If we want to study how we ought to reason (normative) we should start by looking at the primary way that we do reason (descriptive): through the use of arguments. In order to develop a theory of good reasoning, we will start with an account of what an argument is and then proceed to talk about what constitutes a “good” argument.

I. Arguments

- Arguments are a set of statements (premises and conclusion).

- The premises provide evidence, reasons, and grounds for the conclusion.

- The conclusion is what is being argued for.

- An argument attempts to draw some logical connection between the premises and the conclusion.

- And in doing so, the argument expresses an inference: a process of reasoning from the truth of the premises to the truth of the conclusion.

Example : The world will end on August 6, 2045. I know this because my dad told me so and my dad is smart.

In this instance, the conclusion is the first sentence (“The world will end…”); the premises (however dubious) are revealed in the second sentence (“I know this because…”).

II. Statements

Conclusions and premises are articulated in the form of statements . Statements are sentences that can be determined to possess or lack truth. Some examples of true-or-false statements can be found below. (Notice that while some statements are categorically true or false, others may or may not be true depending on when they are made or who is making them.)

Examples of sentences that are statements:

- It is below 40°F outside.

- Oklahoma is north of Texas.

- The Denver Broncos will make it to the Super Bowl.

- Russell Westbrook is the best point guard in the league.

- I like broccoli.

- I shouldn’t eat French fries.

- Time travel is possible.

- If time travel is possible, then you can be your own father or mother.

However, there are many sentences that cannot so easily be determined to be true or false. For this reason, these sentences identified below are not considered statements.

- Questions: “What time is it?”

- Commands: “Do your homework.”

- Requests: “Please clean the kitchen.”

- Proposals: “Let’s go to the museum tomorrow.”

Question: Why are arguments only made up of statements?

First, we only believe statements . It doesn’t make sense to talk about believing questions, commands, requests or proposals. Contrast sentences on the left that are not statements with sentences on the right that are statements:

| Non-statements | Statements |

| What time is it? Do your homework. | The time is 11:00 a.m. My teacher wants me to do my homework. |

It would be non-sensical to say that we believe the non-statements (e.g. “I believe what time is it?”). But it makes perfect sense to say that we believe the statements (e.g. “I believe the time is 11 a.m.”). If conclusions are the statements being argued for, then they are also ideas we are being persuaded to believe. Therefore, only statements can be conclusions.

Second, only statements can provide reasons to believe.

- Q: Why should I believe that it is 11:00 a.m.? A: Because the clock says it is 11a.m.

- Q: Why should I believe that we are going to the museum tomorrow? A: Because today we are making plans to go.

Sentences that cannot be true or false cannot provide reasons to believe. So, if premises are meant to provide reasons to believe, then only statements can be premises.

III. Representing Arguments

As we concern ourselves with arguments, we will want to represent our arguments in some way, indicating which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. We shall represent arguments in two ways. For both ways, we will number the premises.

In order to identify the conclusion, we will either label the conclusion with a (c) or (conclusion). Or we will mark the conclusion with the ∴ symbol

Example Argument:

There will be a war in the next year. I know this because there has been a massive buildup in weapons. And every time there is a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war. My guru said the world will end on August 6, 2045.

- There has been a massive buildup in weapons.

- Every time there has been a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war.

(c) There will be a war in the next year.

∴ There will be a war in the next year.

Of course, arguments do not come labeled as such. And so we must be able to look at a passage and identify whether the passage contains an argument and if it does, we should also be identify which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. This is harder than you might think!

There is no argument here. There is no statement being argued for. There are no statements being used as reasons to believe. This is simply a report of information.

The following are also not arguments:

Advice: Be good to your friends; your friends will be good to you.

Warnings: No lifeguard on duty. Be careful.

Associated claims: Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to the dark side.

When you have an argument, the passage will express some process of reasoning. There will be statements presented that serve to help the speaker building a case for the conclusion.

IV. How to L ook for A rguments [1]

How do we identify arguments in real life? There are no easy, mechanical rules, and we usually have to rely on the context in order to determine which are the premises and the conclusions. But sometimes the job can be made easier by the presence of certain premise or conclusion indicators. For example, if a person makes a statement, and then adds “this is because …,” then it is quite likely that the first statement is presented as a conclusion, supported by the statements that come afterward. Other words in English that might be used to indicate the premises to follow include:

- firstly, secondly, …

- for, as, after all

- assuming that, in view of the fact that

- follows from, as shown / indicated by

- may be inferred / deduced / derived from

Of course whether such words are used to indicate premises or not depends on the context. For example, “since” has a very different function in a statement like “I have been here since noon,” unlike “X is an even number since X is divisible by 4.” In the first instance (“since noon”) “since” means “from.” In the second instance, “since” means “because.”

Conclusions, on the other hand, are often preceded by words like:

- therefore, so, it follows that

- hence, consequently

- suggests / proves / demonstrates that

- entails, implies

Here are some examples of passages that do not contain arguments.

1. When people sweat a lot they tend to drink more water. [Just a single statement, not enough to make an argument.]

2. Once upon a time there was a prince and a princess. They lived happily together and one day they decided to have a baby. But the baby grew up to be a nasty and cruel person and they regret it very much. [A chronological description of facts composed of statements but no premise or conclusion.]

3. Can you come to the meeting tomorrow? [A question that does not contain an argument.]

Do these passages contain arguments? If so, what are their conclusions?

- Cutting the interest rate will have no effect on the stock market this time around, as people have been expecting a rate cut all along. This factor has already been reflected in the market.

- So it is raining heavily and this building might collapse. But I don’t really care.

- Virgin would then dominate the rail system. Is that something the government should worry about? Not necessarily. The industry is regulated, and one powerful company might at least offer a more coherent schedule of services than the present arrangement has produced. The reason the industry was broken up into more than 100 companies at privatization was not operational, but political: the Conservative government thought it would thus be harder to renationalize (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- Bill will pay the ransom. After all, he loves his wife and children and would do everything to save them.

- All of Russia’s problems of human rights and democracy come back to three things: the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. None works as well as it should. Parliament passes laws in a hurry, and has neither the ability nor the will to call high officials to account. State officials abuse human rights (either on their own, or on orders from on high) and work with remarkable slowness and disorganization. The courts almost completely fail in their role as the ultimate safeguard of freedom and order (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- Most mornings, Park Chang Woo arrives at a train station in central Seoul, South Korea’s capital. But he is not commuter. He is unemployed and goes there to kill time. Around him, dozens of jobless people pass their days drinking soju, a local version of vodka. For the moment, middle-aged Mr. Park would rather read a newspaper. He used to be a bricklayer for a small construction company in Pusan, a southern port city. But three years ago the country’s financial crisis cost him that job, so he came to Seoul, leaving his wife and two children behind. Still looking for work, he has little hope of going home any time soon (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- For a long time, astronomers suspected that Europa, one of Jupiter’s many moons, might harbour a watery ocean beneath its ice-covered surface. They were right. Now the technique used earlier this year to demonstrate the existence of the Europan ocean has been employed to detect an ocean on another Jovian satellite, Ganymede, according to work announced at the recent American Geo-physical Union meeting in San Francisco (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- There are no hard numbers, but the evidence from Asia’s expatriate community is unequivocal. Three years after its handover from Britain to China, Hong Kong is unlearning English. The city’s gweilos (Cantonese for “ghost men”) must go to ever greater lengths to catch the oldest taxi driver available to maximize their chances of comprehension. Hotel managers are complaining that they can no longer find enough English-speakers to act as receptionists. Departing tourists, polled at the airport, voice growing frustration at not being understood (The Economist 1/20/2001).

V. Evaluating Arguments

Q: What does it mean for an argument to be good? What are the different ways in which arguments can be good? Good arguments:

- Are persuasive.

- Have premises that provide good evidence for the conclusion.

- Contain premises that are true.

- Reach a true conclusion.

- Provide the audience good reasons for accepting the conclusion.

The focus of logic is primarily about one type of goodness: The logical relationship between premises and conclusion.

An argument is good in this sense if the premises provide good evidence for the conclusion. But what does it mean for premises to provide good evidence? We need some new concepts to capture this idea of premises providing good logical support. In order to do so, we will first need to distinguish between two types of argument.

VI. Two Types of Arguments

The two main types of arguments are called deductive and inductive arguments. We differentiate them in terms of the type of support that the premises are meant to provide for the conclusion.

Deductive Arguments are arguments in which the premises are meant to provide conclusive logical support for the conclusion.

1. All humans are mortal

2. Socrates is a human.

∴ Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

1. No student in this class will fail.

2. Mary is a student in this class.

∴ Therefore, Mary will not fail.

1. A intersects lines B and C.

2. Lines A and B form a 90-degree angle

3. Lines A and C form a 90-degree angle.

∴ B and C are parallel lines.

Inductive arguments are, by their very nature, risky arguments.

Arguments in which premises provide probable support for the conclusion.

Statistical Examples:

1. Ten percent of all customers in this restaurant order soda.

2. John is a customer.

∴ John will not order Soda..

1. Some students work on campus.

2. Bill is a student.

∴ Bill works on campus.

1. Vegas has the Carolina Panthers as a six-point favorite for the super bowl.

∴ Carolina will win the Super Bowl.

VII. Good Deductive Arguments

The First Type of Goodness: Premises play their function – they provide conclusive logical support.

Deductive and inductive arguments have different aims. Deductive argument attempt to provide conclusive support or reasons; inductive argument attempt to provide probable reasons or support. So we must evaluate these two types of arguments.

Deductive arguments attempt to be valid.

To put validity in another way: if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

It is very important to note that validity has nothing to do with whether or not the premises are, in fact, true and whether or not the conclusion is in fact true; it merely has to do with a certain conditional claim. If the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

Q: What does this mean?

- The validity of an argument does not depend upon the actual world. Rather, it depends upon the world described by the premises.

- First, consider the world described by the premises. In this world, is it logically possible for the conclusion to be false? That is, can you even imagine a world in which the conclusion is false?

Reflection Questions:

- If you cannot, then why not?

- If you can, then provide an example of a valid argument.

You should convince yourself that validity is not just about the actual truth or falsity of the premises and conclusion. Rather, validity only has to do with a certain logical relationship between the truth of the premise and the truth of the conclusion. So the only possible combination that is ruled out by a valid argument is a set of true premises and false conclusion.

Let’s go back to example #1. Here are the premises:

1. All humans are mortal.

If both of these premises are true, then every human that we find must be a mortal. And this means, that it must be the case that if Socrates is a human, that Socrates is mortal.

Reflection Questions about Invalid Arguments:

- Can you have an invalid argument with a true premise?

- Can you have an invalid argument with true premises and a true conclusion?

The s econd type of goodness for deductive arguments: The premises provide us the right reasons to accept the conclusion.

Soundness V ersus V alidity:

Our original argument is a sound one:

∴ Socrates is mortal.

Question: Can a sound argument have a false conclusion?

VIII. From Deductive Arguments to Inductive Arguments

Question: What happens if we mix around the premises and conclusion?

2. Socrates is mortal.

∴ Socrates is a human.

1. Socrates is mortal

∴ All humans are mortal.

Are these valid deductive arguments?

NO, but they are common inductive arguments.

Other examples :

Suppose that there are two opaque glass jars with different color marbles in them.

1. All the marbles in jar #1 are blue.

2. This marble is blue.

∴ This marble came from jar #1.

1. This marble came from jar #2.

2. This marble is red.

∴ All the marbles in jar #2 are red.

While this is a very risky argument, what if we drew 100 marbles from jar #2 and found that they were all red? Would this affect the second argument’s validity?

IX. Inductive Arguments:

The aim of an inductive argument is different from the aim of deductive argument because the type of reasons we are trying to provide are different. Therefore, the function of the premises is different in deductive and inductive arguments. And again, we can split up goodness into two types when considering inductive arguments:

- The premises provide the right logical support.

- The premises provide the right type of reason.

Logical S upport:

Remember that for inductive arguments, the premises are intended to provide probable support for the conclusion. Thus, we shall begin by discussing a fairly rough, coarse-grained way of talking about probable support by introducing the notions of strong and weak inductive arguments.

A strong inductive argument:

- The vast majority of Europeans speak at least two languages.

- Sam is a European.

∴ Sam speaks two languages.

Weak inductive argument:

- This quarter is a fair coin.

∴ Therefore, the next coin flip will land heads.

- At least one dog in this town has rabies.

- Fido is a dog that lives in this town.

∴ Fido has rabies.

The R ight T ype of R easons. As we noted above, the right type of reasons are true statements. So what happens when we get an inductive argument that is good in the first sense (right type of logical support) and good in the second sense (the right type of reasons)? Corresponding to the notion of soundness for deductive arguments, we call inductive arguments that are good in both senses cogent arguments.

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a strong inductive argument?

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a cogent inductive argument?

|

|

|

| True | True |

| True | False |

| False | True |

| False | False |

X. Steps for Evaluating Arguments:

- Read a passage and assess whether or not it contains an argument.

- If it does contain an argument, then identify the conclusion and premises.

- If yes, then assess it for soundness.

- If not, then treat it as an inductive argument (step 3).

- If the inductive argument is strong, then is it cogent?

XI. Evaluating Real – World Arguments

An important part of evaluating arguments is not to represent the arguments of others in a deliberately weak way.

For example, suppose that I state the following:

All humans are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.

Is this valid? Not as it stands. But clearly, I believe that Socrates is a human being. Or I thought that was assumed in the conversation. That premise was clearly an implicit one.

So one of the things we can do in the evaluation of argument is to take an argument as it is stated, and represent it in a way such that it is a valid deductive argument or a strong inductive one. In doing so, we are making explicit what one would have to assume to provide a good argument (in the sense that the premises provide good – conclusive or probable – reason to accept the conclusion).

The teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair because Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- The teacher’s policy on extra credit is fair only if everyone gets a chance to receive extra credit.

Therefore, the teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair.

Valid argument

Sally didn’t train very hard so she didn’t win the race.

- Sally didn’t train very hard.

- If you don’t train hard, you won’t win the race.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win the race.

Strong (not valid):

- If you won the race, you trained hard.

- Those who don’t train hard are likely not to win.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win.

Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury. However, universities have no obligations to pay similar compensation to student athletes if they are hurt while playing sports. So, universities are not doing what they should.

- Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury that prevents them working.

- Student athletes are just like ordinary workers except that their job is to play sports.

- So if student athletes are injured while playing sports, they should also be provided worker’s compensation benefits.

- Universities have no obligations to provide injured student athletes compensation.

Therefore, universities are not doing what they should.

Deductively valid argument

If Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system in his first term as president, then the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- In Obama’s first term as president, both the House and Senate were under Democratic control.

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican-controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

- Obama’s first term as president will be much easier than the next president’s term in terms of passing legislation.

Therefore, the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

Strong inductive argument

Sam is weaker than John. Sam is slower than John. So Sam’s time on the obstacle will be slower than John’s.

- Sam is weaker than John.

- Sam is slower than John.

- A person’s strength and speed inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

XII. Diagramming Arguments

All the arguments we’ve dealt with – except for the last two – have been fairly simple in that the premises always provided direct support for the conclusion. But in many arguments, such as the last one, there are often arguments within arguments.

Obama example :

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

∴ The next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

It’s clear that premises #2 and #3 are used in support of #4. And #1 in combination with #4 provides support for the conclusion.

When we diagram arguments, the aim is to represent the logical relationships between premises and conclusion. More specifically, we want to identify what each premise supports and how.

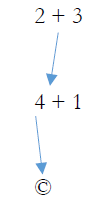

This represents that 2+3 together provide support for 4

This represents that 4+1 together provide support for 5

When we say that 2+3 together or 4+1 together support some statement, we mean that the logical support of these statements are dependent upon each other. Without the other, these statements would not provide evidence for the conclusion. In order to identify when statements are dependent upon one another, we simply underline the set that are logically dependent upon one another for their evidential support. Every argument has a single conclusion, which the premises support; therefore, every argument diagram should point to the conclusion (c).

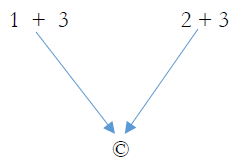

Sam Example:

- Sam is less flexible than John.

- A person’s strength and flexibility inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

∴ Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

In some cases, different sets of premises provide evidence for the conclusion independently of one another. In the argument above, there are two logically independent arguments for the conclusion that Sam’s time will be slower than John’s. That Sam is weaker than John and that being weaker correlates with a slower time provide evidence for the conclusion that Sam will be slower than John. Completely independent of this argument is the fact that Sam is less flexible and that being less flexible corresponds with a slower time. The diagram above represent these logical relations by showing that #1 and #3 dependently provide support for #4. Independent of that argument, #2 and #3 also dependently provide support for #4. Therefore, there are two logically independent sets of premises that provide support for the conclusion.

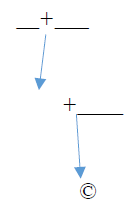

Try diagramming the following argument for yourself. The structure of the argument has been provided below:

- All humans are mortal

- Socrates is human

- So Socrates is mortal.

- If you feed a mortal person poison, he will die.

∴ Therefore, Socrates has been fed poison, so he will die.

- This section is taken from http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ and is in use under creative commons license. Some modifications have been made to the original content. ↵

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Wrestling with Philosophy

Official Website for Amitabha Palmer

Critical Thinking: Defining an Argument, Premises, and Conclusions

Defining an Argument Argument: vas is das? For most of us when we hear the word ‘argument’ we think of something we’d rather avoid. As it is commonly understood, an argument involves some sort of unpleasant confrontation (well, maybe not always unpleasant–it can feel pretty good when you win!). While this is one notion of ‘argument,’ it’s (generally) not what the term refers to in philosophy. In philosophy what we mean by argument is “ a set of reasons offered in support of a claim.” An argument, in this narrower sense, also generally implies some sort of structure . For now we’ll ignore the more particular structural aspects and focus on the two primary elements that make up an argument: premises and conclusions. Lets talk about conclusions first because their definition is pretty simple. A conclusion is the final assertion that is supported with evidence and reasons. What’s important is the relationship between premises and conclusions. The premises are independent reasons and evidence that support the conclusion. In an argument, the conclusion should follow from the premises. Lets consider a simple example: Reason (1): Everyone thought Miley Cyrus’ performance was a travesty. Reason (2): Some people thought her performance was offensive. Conclusion: Therefore, some people thought her performance was both a travesty and offensive. Notice that so long as we accept reason 1 and reason 2 as true, then we must also accept the conclusion. This is what we mean by “the conclusion ‘follows’ from the premises.” Lets examine premises a little more closely. A premise is any reason or evidence that supports the conclusion of the argument. In the context of arguments we can use ‘reasons’, ‘evidence’, and ‘premises’ interchangeably. For example, if my conclusion is that dogs are better pets than cats, I might offer the following reasons: (P1) dogs are generally more affectionate than cats and (P2) dogs are more responsive to their owners’ commands than cats. From my two premises, I infer my conclusion that (C) dogs are better pets than cats.

Lets return to the definition of an argument. Notice that in the definition, I’ve said that arguments are a set of reasons. While this isn’t always true, generally, a good argument will generally have more than one premise. Heuristics for Identifying Premises and Conclusions Now that we know what each concept is, lets look at how to identify each one as we might encounter them “in nature” (e.g., in an article, in a conversation, in a meme, in a homework exercise, etc…). First I’ll explain each heuristic, then I’ll apply them to some examples. Identifying conclusions: The easiest way to go about decomposing arguments is to first try to find the conclusion. This is a good strategy because there is usually only one conclusion so, if we can identify it, it means the rest of the passage are premises. For this reason, most of the heuristics focus on finding the conclusion. Heuristic 1: Look for the most controversial statement in the argument. The conclusion will generally be the most controversial statement in the argument. If you think about it, this makes sense. Typically arguments proceed by moving from assertions (i.e., premises) the audience agrees with then showing how these assertions imply something that the audience might not have previously agreed with. Heuristic 2: The conclusion is usually a statement that takes a position on an issue . By implication, the premises will be reasons that support the position on the issue (i.e., the conclusion). A good way to apply this heuristic is to ask “what is the arguer trying to get me to believe?”. The answer to this question is generally going to be the conclusion. Heuristic 3: The conclusion is usually ( but not always ) the first or last statement of the argument. Heuristic 4: The “because” test. Use this method you’re having trouble figuring which of 2 statements is the conclusion. The “because” test helps you figure out which statement is supporting which. Recall that the premise(s) always supports the conclusion. This method is best explained by using an example. Suppose you encounter an argument that goes something like this: It’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit. It tastes delicious. Also, lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer Suppose you’re having trouble deciding what the conclusion it. You’ve eliminated “it tastes delicious” as a candidate but you still have to choose between “it’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit” and “lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer”. To use the because test, read one statement after the other but insert the word “because” between the two and see what makes more sense. Lets try the two possibilities: A: It’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit because lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer. B: Lots of facebook posts say that amazonian jungle fruit cures cancer because it’s a good idea to eat lots of it. Which makes more sense? Which is providing support for which? The answer is A. Lots of facebook posts saying something is a reason (i.e. premise) to believe that it’s a good idea to eat amazonian jungle fruit–despite the fact that it’s not a very good reason… Identifying the Premises Heuristic 1: Identifying the premises once you’ve identified the conclusion is cake. Whatever isn’t contained in the conclusion is either a premise or “filler” (i.e., not relevant to the argument). We will explore the distinguishing between filler and relevant premises a bit later, so don’t worry about that distinction for now. Example 1 Gun availability should be regulated. Put simply, if your fellow citizens have easy access to guns, they’re more likely to kill you than if they don’t have access. Interestingly, this turned out to be true not just for the twenty-six developed countries analyzed, but on a State-to-State level too. http://listverse.com/2013/04/21/10-arguments-for-gun-control/

Ok, lets try heuristic #1. What’s the most controversial statement? For most Americans, it is probably that “gun availability should be regulated.” This is probably the conclusion. Just for fun lets try out the other heuristics. Heuristic #2 says we should find a statement that takes a position on an issue. Hmmm… the issue seems to be gun control, and the arguer takes a position. Both heuristics converge on “gun availability should be regulated.” Heuristic #3 says the conclusion will usually be the first or last statement. Guess what? Same result as the other heuristics. Heuristic #4. A: Gun availability should be regulated because people with easy access to guns are more likely to kill you. Or B: People with easy access to guns are more likely to kill you because gun availability should be regulated. A is the winner. The conclusion in this argument is well established. It follows that what’s left over are premises (support for the conclusion): (P1) If your fellow citizens have easy access to guns, they’re more likely to kill you than if they don’t have access. (P2) Studies show that P1 is true, not just for the twenty-six developed countries analyzed, but on a State-to-State level too. (C) G un availability should be regulated. Example 2 If you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns. This means only “bad” guys would have guns, while good people would by definition be at a disadvantage. Gun control is a bad idea. Heuristic #1: What’s the most controversial statement? Probably “gun control is a bad idea.” Heuristic #2: Which statement takes a position on an issue? “Gun control is a bad idea.” Heuristic #3: “Gun control is a bad idea” is last and also passed heuristic 1 and 2. Probably a good bet as the conclusion. Heuristic #4: A: If you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns because gun control is a bad idea.

B: Gun control is a bad idea because if you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Published by philosophami

Philosopher, judoka, coach, traveller, hiker, dancer, and dog-lover. View all posts by philosophami

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Critiquing Arguments

How To Tell When Arguments Are Valid or Sound

- Belief Systems

- Key Figures in Atheism

- M.A., Princeton University

- B.A., University of Pennsylvania