Trending Today

Spending Too Much Time on Homework Linked to Lower Test Scores

A new study suggests the benefits to homework peak at an hour a day. After that, test scores decline.

Samantha Larson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/58/e3587081-d161-4c6e-b4f9-a94b3520c60d/homework.jpg)

Polls show that American public high school teachers assign their students an average of 3.5 hours of homework a day . According to a recent study from the University of Oviedo in Spain, that’s far too much.

While doing some homework does indeed lead to higher test performance, the researchers found the benefits to hitting the books peak at about an hour a day. In surveying the homework habits of 7,725 adolescents, this study suggests that for students who average more than 100 minutes a day on homework, test scores start to decline. The relationship between spending time on homework and scoring well on a test is not linear, but curved.

This study builds upon previous research that suggests spending too much time on homework leads to higher stress, health problems and even social alienation. Which, paradoxically, means the most studious of students are in fact engaging in behavior that is counterproductive to doing well in school.

Because the adolescents surveyed in the new study were only tested once, the researchers point out that their results only indicate the correlation between test scores and homework, not necessarily causation. Co-author Javier Suarez-Alvarez thinks the most important findings have less to do with the amount of homework than with how that homework is done.

From Education Week :

Students who did homework more frequently – i.e., every day – tended to do better on the test than those who did it less frequently, the researchers found. And even more important was how much help students received on their homework – those who did it on their own preformed better than those who had parental involvement. (The study controlled for factors such as gender and socioeconomic status.)

“Once individual effort and autonomous working is considered, the time spent [on homework] becomes irrelevant,” Suarez-Alvarez says. After they get their daily hour of homework in, maybe students should just throw the rest of it to the dog.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Samantha Larson | | READ MORE

Samantha Larson is a freelance writer who particularly likes to cover science, the environment, and adventure. For more of her work, visit SamanthaLarson.com

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

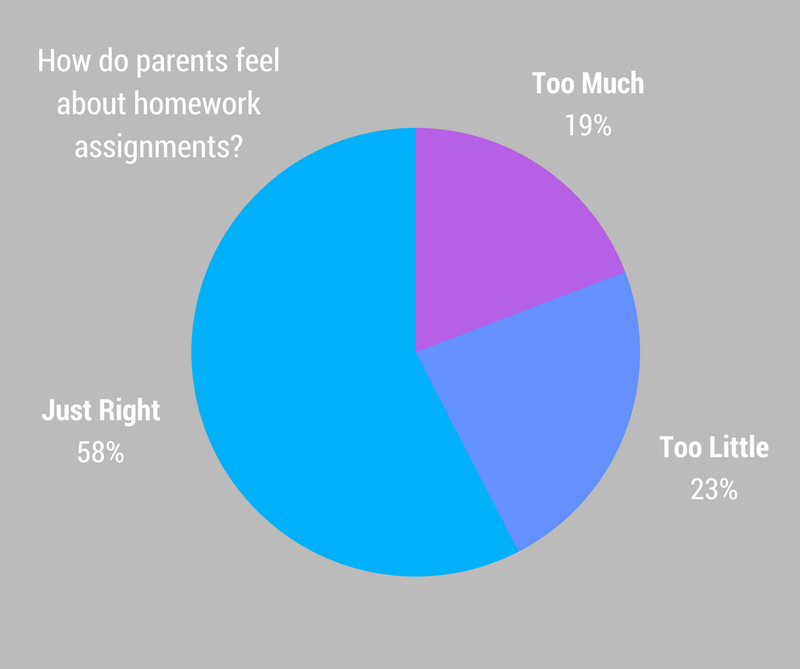

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

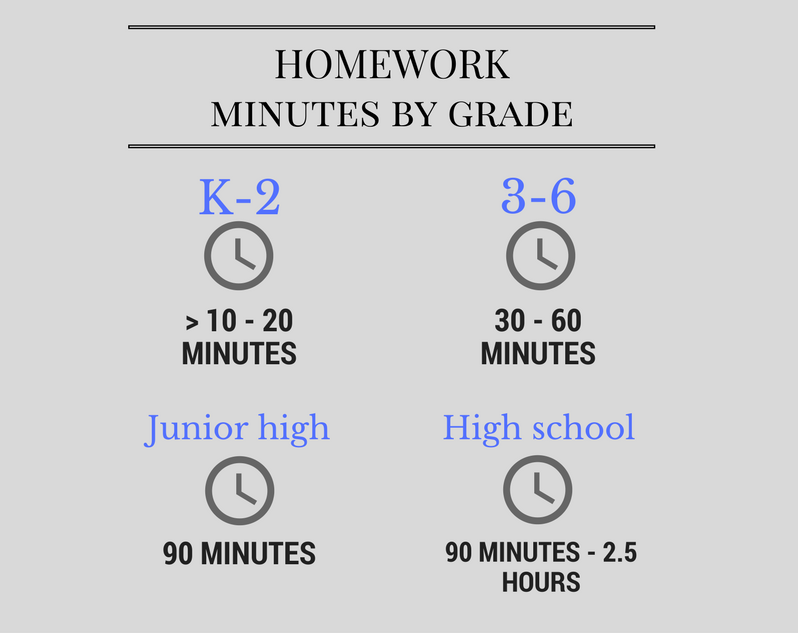

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Study: Homework Doesn’t Mean Better Grades, But Maybe Better Standardized Test Scores

Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at UVA's Curry School of Education

The time students spend on math and science homework doesn’t necessarily mean better grades, but it could lead to better performance on standardized tests, a new study finds.

“When Is Homework Worth The Time?” was recently published by lead investigator Adam Maltese, assistant professor of science education at Indiana University, and co-authors Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education , and Xitao Fan, dean of education at the University of Macau. Maltese is a Curry alumnus, and Fan is a former Curry faculty member.

The authors examined survey and transcript data of more than 18,000 10th-grade students to uncover explanations for academic performance. The data focused on individual classes, examining student outcomes through the transcripts from two nationwide samples collected in 1990 and 2002 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

Contrary to much published research, a regression analysis of time spent on homework and the final class grade found no substantive difference in grades between students who complete homework and those who do not. But the analysis found a positive association between student performance on standardized tests and the time they spent on homework.

“Our results hint that maybe homework is not being used as well as it could be,” Maltese said.

Tai said that homework assignments cannot replace good teaching.

“I believe that this finding is the end result of a chain of unfortunate educational decisions, beginning with the content coverage requirements that push too much information into too little time to learn it in the classroom,” Tai said. “The overflow typically results in more homework assignments. However, students spending more time on something that is not easy to understand or needs to be explained by a teacher does not help these students learn and, in fact, may confuse them.

“The results from this study imply that homework should be purposeful,” he added, “and that the purpose must be understood by both the teacher and the students.”

The authors suggest that factors such as class participation and attendance may mitigate the association of homework to stronger grade performance. They also indicate the types of homework assignments typically given may work better toward standardized test preparation than for retaining knowledge of class material.

Maltese said the genesis for the study was a concern about whether a traditional and ubiquitous educational practice, such as homework, is associated with students achieving at a higher level in math and science. Many media reports about education compare U.S. students unfavorably to high-achieving math and science students from across the world. The 2007 documentary film “Two Million Minutes” compared two Indiana students to students in India and China, taking particular note of how much more time the Indian and Chinese students spent on studying or completing homework.

“We’re not trying to say that all homework is bad,” Maltese said. “It’s expected that students are going to do homework. This is more of an argument that it should be quality over quantity. So in math, rather than doing the same types of problems over and over again, maybe it should involve having students analyze new types of problems or data. In science, maybe the students should write concept summaries instead of just reading a chapter and answering the questions at the end.”

This issue is particularly relevant given that the time spent on homework reported by most students translates into the equivalent of 100 to 180 50-minute class periods of extra learning time each year.

The authors conclude that given current policy initiatives to improve science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, education, more evaluation is needed about how to use homework time more effectively. They suggest more research be done on the form and function of homework assignments.

“In today’s current educational environment, with all the activities taking up children’s time both in school and out of school, the purpose of each homework assignment must be clear and targeted,” Tai said. “With homework, more is not better.”

Media Contact

Rebecca P. Arrington

Office of University Communications

[email protected] (434) 924-7189

Article Information

November 20, 2012

/content/study-homework-doesn-t-mean-better-grades-maybe-better-standardized-test-scores

Study: Too much homework can lower test scores

Piling on the homework doesn’t help kids do better in school. In fact, it can lower their test scores, the Huffington Post reports. That’s the conclusion of a group of Australian researchers, who have taken the aggregate results of several recent studies investigating the relationship between time spent on homework and students’ academic performance. According to Richard Walker, an educational psychologist at Sydney University, data shows that in countries where more time is spent on homework, students score lower on a standardized test called the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA. The same correlation is also seen when comparing homework time and test performance at schools within countries. Past studies have also demonstrated this basic trend…

Click here for the full story

Sign up for our K-12 newsletter

- Recent Posts

- ‘Buyer’s remorse’ dogging Common Core rollout - October 30, 2014

- Calif. law targets social media monitoring of students - October 2, 2014

- Elementary world language instruction - September 25, 2014

Want to share a great resource? Let us know at [email protected] .

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

" * " indicates required fields

eSchool News uses cookies to improve your experience. Visit our Privacy Policy for more information.

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

- Health A to Z

- Alternative Medicine

- Blood Disorders

- Bone and Joint

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Child Health

- Coronavirus

- Dental Care

- Digestive System

- Disabilities

- Drug Center

- Ear, Nose, and Throat

- Environmental Health

- Exercise And Fitness

- First Aid and Emergencies

- General Health

- Health Technology

- Hearing Loss

- Hypertension

- Infectious Disease

- LGBTQ Health

- Liver Health

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Pain Management

- Public Health

- Pulmonology

- Senior Health

- Sexual Health

- Skin Health

- Women's Health

- News For Medical Professionals

- Our Products

- Consumer News

- Physician's Briefing

- HealthDay TV

- Wellness Library

- HealthDay Living

- Conference Coverage

- Custom Products

- Health Writing

- Health Editing

- Video Production

- Medical Review

Too Much Homework May Hurt Teens' Test Scores

THURSDAY, March 26, 2015 (HealthDay News) -- More isn't necessarily better for teens when it comes to homework, a new study finds.

About an hour a day is ideal, and doing homework alone and regularly yielded the best results, Spanish researchers report.

"The conclusion is that when it comes to homework, how is more important than how much," wrote study co-author Javier Suarez-Alvarez, from the University of Oviedo. "Once individual effort and autonomous working is considered, the time spent becomes irrelevant."

The team looked at more than 7,700 male and female students, average age 14, in Spain. The teens were asked about their homework habits, and their performance in math and science was assessed using a standardized test.

The students spent an average of one to two hours a day doing homework in all subjects. Those whose teachers regularly assigned homework scored nearly 50 points higher on the standardized test, and those who did their math homework on their own scored 54 points higher than those who frequently or always had help. The findings were similar for science homework.

On average, teachers assigned just over 70 minutes of homework per day. Students showed small gains in math and science when they did between 70 and 90 minutes of homework, but their test results began to decline when they had more than 90 minutes of homework.

The study was published recently in the Journal of Educational Psychology .

While doing 70 to 90 minutes of homework yielded a slight improvement, "that small gain requires two hours more homework per week, which is a large time investment for such small gains," Suarez-Alvarez said in a journal news release.

"For that reason, assigning more than 70 minutes of homework per day does not seem very efficient," he added.

More information

The American Academy of Pediatrics has more about homework .

Related Stories

Too Much Homework Is Bad for Kids

Piling on the homework doesn't help kids do better in school. In fact, it can lower their test scores.

That's the conclusion of a group of Australian researchers, who have taken the aggregate results of several recent studies investigating the relationship between time spent on homework and students' academic performance.

According to Richard Walker, an educational psychologist at Sydney University, data shows that in countries where more time is spent on homework, students score lower on a standardized test called the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA. The same correlation is also seen when comparing homework time and test performance at schools within countries. Past studies have also demonstrated this basic trend.

Inundating children with hours of homework each night is detrimental, the research suggests, while an hour or two per week usually doesn't impact test scores one way or the other. However, homework only bolsters students' academic performance during their last three years of grade school. "There is little benefit for most students until senior high school (grades 10-12)," Walker told Life's Little Mysteries .

The research is detailed in his new book, "Reforming Homework: Practices, Learning and Policies" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

The same basic finding holds true across the globe, including in the U.S., according to Gerald LeTendre of Pennsylvania State University. He and his colleagues have found that teachers typically give take-home assignments that are unhelpful busy work. Assigning homework "appeared to be a remedial strategy (a consequence of not covering topics in class, exercises for students struggling, a way to supplement poor quality educational settings), and not an advancement strategy (work designed to accelerate, improve or get students to excel)," LeTendre wrote in an email. [ Kids Believe Literally Everything They Read Online, Even Tree Octopuses ]

This type of remedial homework tends to produce marginally lower test scores compared with children who are not given the work. Even the helpful, advancing kind of assignments ought to be limited; Harris Cooper, a professor of education at Duke University, has recommended that students be given no more than 10 to 15 minutes of homework per night in second grade, with an increase of no more than 10 to 15 minutes in each successive year.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most homework's neutral or negative impact on students' academic performance implies there are better ways for them to spend their after school hours than completing worksheets. So, what should they be doing? According to LeTendre, learning to play a musical instrument or participating in clubs and sports all seem beneficial , but there's no one answer that applies to everyone.

"These after-school activities have much more diffuse goals than single subject test scores," he wrote. "When I talk to parents … they want their kids to be well-rounded, creative, happy individuals — not just kids who ace the tests."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @ nattyover . Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @ llmysteries , then join us on Facebook .

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket grounded for 2nd time in 2 months following explosive landing failure

Ancient Egyptians used so much copper, they polluted the harbor near the pyramids, study finds

James Webb telescope spots 6 enormous 'rogue planets' tumbling through space without a star

Most Popular

- 2 Ancient Egyptians used so much copper, they polluted the harbor near the pyramids, study finds

- 3 James Webb telescope spots 6 enormous 'rogue planets' tumbling through space without a star

- 4 T. rex relative with giant, protruding eyebrows discovered in Kyrgyzstan

- 5 'Everything we found shattered our expectations': Archaeologists discover 1st astronomical observatory from ancient Egypt

Analyzing ‘the homework gap’ among high school students

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, michael hansen and michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies diana quintero diana quintero former senior research analyst, brown center on education policy - the brookings institution, ph.d. student - vanderbilt university.

August 10, 2017

Researchers have struggled for decades to identify a causal, or even correlational, relationship between time spent in school and improved learning outcomes for students. Some studies have focused on the length of a school year while others have focused on hours in a day and others on hours in the week .

In this blog post, we will look at time spent outside of school–specifically time spent doing homework–among different racial and socio-economic groups. We will use data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) to shed light on those differences and then attempt to explain those gaps, using ATUS data and other evidence.

What we know about out-of-school time

Measuring the relationship between out-of-school time and outcomes like test scores can be difficult. Researchers are primarily confounded by an inability to determine what compels students to choose homework during their time off over other activities. Are those who spend more time on homework just extra motivated? Or are they struggling students who need to work harder to keep up? What role do social expectations from parents or peers play?

Previous studies have examined the impact of this outside time use on educational outcomes for students. A 2007 study using data from Berea College in Kentucky identified a causal relationship between hours spent studying and a student’s academic performance through an interesting measure. The researchers took advantage of randomly assigned college roommates, paying attention to those who came to campus with a video game console in tow. They hypothesized students randomly assigned to a roommate without a video game console would study more, since all other factors remained equal. That hypothesis held up, and that group also received significantly higher grades, demonstrating the causal relationship.

Other research has relied on data collected through the American Time Use Survey, a study of how Americans spend their time, and shown the existence of a gender gap and a parental education gap in homework time. Other studies have looked at the relationship between holding a job and student’s time use in discretionary activities , like sleep, media consumption, and time spent on homework. We are curious about out-of-school differences in homework time by race and income.

Descriptive statistics of time use

We began with a general sample of 2,575 full-time high school students between the ages of 15 and 18 from the ATUS, restricting the sample to their answers about time spent on homework during weekdays and school months (September to May). Among all high school students surveyed (those that reported completing their homework and those that did not), the time allocated to complete homework amounted to less than an hour per day, despite the fact that high school teachers report they assign an average of 3.5 hours of homework per day.

To explore racial or income-based differences, in Figure 1, we plot the minutes that students reporting spending on homework separately by their racial/ethnic group and family income. We observed a time gap between racial groups, with Asian students spending the most time on homework (nearly two hours a day). Similarly, we observe a time gap by the students’ family income.

We can also use ATUS data to isolate when students do homework by race and by income. In Figure 2, we plot the percentage of high school students in each racial and income group doing homework by the time of day. Percentages remain low during the school day and then expectedly increase when students get home, with more Asian students doing more homework and working later into the night than other racial groups. Low-income students reported doing less homework per hour than their non-low-income peers.

Initial attempts to explain the homework gap

We hypothesized that these racial and income-based time gaps could potentially be explained by other factors, like work, time spent caring for others, and parental education. We tested these hypotheses by separating groups based on particular characteristics and comparing the average number of minutes per day spent on homework amongst the comparison groups.

Students who work predictably reported spending less time on educational activities, so if working disproportionately affected particular racial or income groups, then work could help explain the time gap. Students who worked allocated on average 20 minutes less for homework than their counterparts who did not work. Though low-income students worked more hours than their peers, they largely maintained a similar level of homework time by reducing their leisure or extracurricular activities. Therefore, the time gap on homework changed only slightly with the inclusion of work as a factor.

We also incorporated time spent taking care of others in the household. Though a greater percentage of low-income students take care of other household members, we found that this does not have a statistically significant effect on homework because students reduce leisure, rather than homework, in an attempt to help their families. Therefore, this variable again does not explain the time gaps.

Finally, we considered parental education, since parents with more education have been shown to encourage their children to value school more and have the resources to ensure homework is completed more easily. Our analysis showed students with at least one parent with any post-secondary degree (associate or above) reported spending more time on homework than their counterparts whose parents do not hold a degree; however, gaps by race still existed, even holding parental education constant. Turning to income levels, we found that parental education is more correlated with homework time among low-income students, reducing the time gap between income groups to only eight minutes.

Societal explanations

Our analysis of ATUS could not fully explain this gap in time spent on homework, especially among racial groups. Instead, we believe that viewing homework as an outcome of the culture of the school and the expectations of teachers, rather than an outcome of a student’s effort, may provide some reasons for its persistence.

Many studies, including recent research , have shown that teachers perceive students of color as academically inferior to their white peers. A 2016 study by Seth Gershenson et al. showed that this expectations gap can also depend on the race of the teacher. In a country where minority students make up nearly half of all public school students, yet minority teachers comprise just 18 percent of the teacher workforce, these differences in expectations matter.

Students of color are also less likely to attend high schools that offer advanced courses (including Advanced Placement courses) that would likely assign more homework, and thus access to rigorous courses may partially explain the gaps as well.

Research shows a similar, if less well-documented, gap by income, with teachers reporting lower expectations and dimmer futures for their low-income students. Low-income students and students of color may be assigned less homework based on lower expectations for their success, thus preventing them from learning as much and creating a self-fulfilling prophecy .

In conclusion, these analyses of time use revealed a substantial gap in homework by race and by income group that could not be entirely explained by work, taking care of others, or parental education. Additionally, differences in educational achievement, especially as measured on standardized tests, have been well-documented by race and by income . These gaps deserve our attention, but we should be wary of blaming disadvantaged groups. Time use is an outcome reflecting multiple factors, not simply motivation, and a greater understanding of that should help raise expectations–and therefore, educational achievement–all around.

Sarah Novicoff contributed to this post.

Related Content

Michael Hansen, Diana Quintero

October 5, 2016

Sarah Novicoff, Matthew A. Kraft

November 15, 2022

September 10, 2015

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Lydia Wilbard

August 29, 2024

Zachary Billot, Annie Vong, Nicole Dias Del Valle, Emily Markovich Morris

August 26, 2024

Brian A. Jacob, Cristina Stanojevich

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Heavier Homework Load Linked to Lower Math, Science Performance, Study Says

- Share article

The optimal amount of homework for 13-year-old students is about an hour a day, a study published earlier this month in the Journal of Educational Psychology suggests. And spending too much time on homework is linked to a decrease in academic performance.

Researchers from the University of Oviedo administered surveys to 7,725 Spanish secondary school students, asking about how many days per week they did homework, how much time they spent on it, how much effort they put in, and how much help they received. The students also took a test with 24 math and 24 science questions.

Students who did homework more frequently—i.e., every day—tended to do better on the test than those who did it less frequently, the researchers found. And even more important was how much help students received on their homework—those who did it on their own performed better than those who had parental involvement. (The study controlled for factors such as gender and socioeconomic status.)

The researchers also found that prior knowledge—measured by previous letter grades—was a better predictor of test performance than any homework factor.

Regarding the amount of time students spent on homework, the results were a bit more complicated.

Overall, students spent on average between one and two hours a day doing homework from all subjects.

Those who spent about 90 to 100 minutes a day on homework scored highest on the assessment—however, they didn’t outperform their peers who spent less time on homework by much. The researchers therefore determined that going from 70 minutes of homework a day to 90 minutes a day is not an efficient use of time. “That small gain requires two hours more homework per week, which is a large time investment for such small gains,” they wrote. “For that reason, assigning more than 70 minutes homework per day does not seem very efficient, as the expectation of improved results is very low.”

And after 90 to 100 minutes of homework, they found, test scores declined. The relationship between minutes of homework and test scores is not linear, but curved.

“The key is that the optimum time is about 60 or 70 minutes [of homework] a day,” Javier Suarez-Alvarez, co-lead researcher on the study, said in an interview.

The study does, of course, come with some caveats. As the researchers note, the results are not causal; they only show a correlation between homework and test scores. Also, the survey did not distinguish between math and science homework. Suarez-Alvarez said the study also brings up questions about how factors like “academic intelligence, self-concept, and self-esteem” play into academic performance.

Even so, the study offers some insights that middle school teachers may find helpful. “Our data indicate that it is not necessary to assign huge quantities of homework, but it is important that assignment is systematic and regular, with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning,” the researchers write.

Or as Suarez-Alvarez put it, “Maybe it’s more important how they do the homework than how much.”

Chart: From “Adolescents’ Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices,” Journal of Educational Psychology , March 16, 2015.

A version of this news article first appeared in the Curriculum Matters blog.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Color Scheme

- Use system setting

- Light theme

Excessive screen time linked to lower student test scores

Are children getting too much screen time?

That question is getting more scrutiny in the wake of recent national standardized tests that showed a decline in reading comprehension among fourth- and eighth-graders.

In Spokane and the rest of the nation, educators have noticed.

“In some ways these devices enhance learning,” said Lisa Laurier, a professor at Whitworth University who specializes in elementary education. “But sometimes the negatives outweigh the positives.”

One study found children ages 8 to 12 are spending an average of five hours a day looking at screens that have nothing to do with their schoolwork.

Laurier said she worries about the long-term effects of heavy screen time, such as the overstimulation of young minds by flashing images.

“You end up with children who seem distracted, who lose their ability to concentrate,” said Laurier, who also worries some school districts are over-reliant on tablets because federal grants make them cheaper than printed materials.

Meanwhile, local officials say they’re working hard to strike an instructional balance.

“Our district on the whole is very mindful of how we distribute these materials,” said Scott Kerwein, director of technology and information at Spokane Public Schools.

Kerwein, who also serves as a teacher counselor, said the addition of screens allows one group of students in a given classroom to work semi-independently while a teacher works one-on-one with other students.

“We know that tech is going to be part of student life now and moving forward,” said Brian Coddington, the district’s director of communications and public relations. “We’re trying to make sure that we help teachers find ways to be selective.”

Everyone agrees on two main points: screens are here to stay and children must be guided toward a balance.

Even as the National Assessment of Educational Progress – often called “the nation’s report card” – was released late last month, independent analysis showed some troubling trends.

The nonprofit Common Sense Media’s annual census of children’s media use, released the same week as the NAEP, found that 94 percent of English/language arts teachers surveyed said they used digital programs for core curriculum activities several times a month.

Using screens for class instruction and homework comes on top of the average of five hours a day.

That too raises a question about communication between parents and teachers: Do they compare notes? And do they have time to do so?

One thing is certain, according to the NAEP data: Locally and nationally, students have lost ground since the 2017 tests on both main reading content areas: literary experience, such as fiction analysis, and reading for information, such as finding evidence to support an argument.

Both grades declined significantly in both areas from 2017 to 2019, but the drop was larger for literary skills. In fact, eighth-graders perform worse now than they did in 2009 in literary experience.

An Education Week analysis of the NAEP data showed a relationship between high-screen and digital-device use and lower proficiency on the test.

For example, students who used digital devices for reading fewer than 30 minutes a day scored on average 8 scale points higher than those who used computers in language arts for longer periods of time.

These light digital users scored 26 scale points higher than the students who spent the longest reading periods on digital devices, four hours or more a day.

To put that into context, one year of school equals roughly 12 points on the NAEP’s 500-point scale.

However, according to Laurier, there’s even more to worry about as children spend hours in front of laptops, tablets and smartphones.

“What we’re seeing,” Laurier said, “is that the brain is starting to develop behaviors that look like ADHD.”

Flashing lights, on-screen movements and the constant shifting of images may contribute to greater distractions and loss of ability to concentrate.

And while the internet and videos offer opportunities to develop background on academic materials, annotation is more difficult on a screen.

“That limits kids to some extent … and comprehension is impaired,” Laurier said.

Returning to the ranch: Roy’s stroke survival story

Thanks to a persistent wife, a fast-acting care team, and a serendipitous day off, Roy Hallmark has returned to life on his rural Priest Lake ranch after suffering a stroke.

Advertisement

Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 January 2021

- Volume 50 , pages 631–651, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Melissa Holland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8349-7168 1 ,

- McKenzie Courtney 2 ,

- James Vergara 3 ,

- Danielle McIntyre 4 ,

- Samantha Nix 5 ,

- Allison Marion 6 &

- Gagan Shergill 1

20k Accesses

17 Citations

127 Altmetric

16 Mentions

Explore all metrics

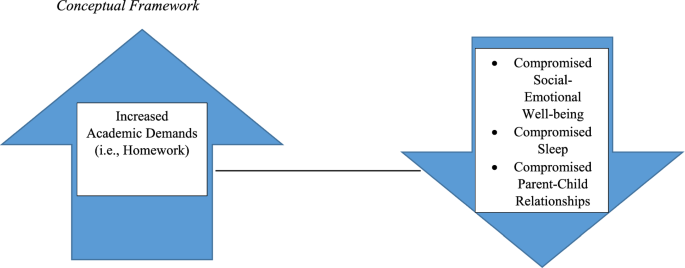

Increasing academic demands, including larger amounts of assigned homework, is correlated with various challenges for children. While homework stress in middle and high school has been studied, research evidence is scant concerning the effects of homework on elementary-aged children.

The objective of this study was to understand rater perception of the purpose of homework, the existence of homework policy, and the relationship, if any, between homework and the emotional health, sleep habits, and parent–child relationships for children in grades 3–6.

Survey research was conducted in the schools examining student ( n = 397), parent ( n = 442), and teacher ( n = 28) perception of homework, including purpose, existing policy, and the childrens’ social and emotional well-being.

Preliminary findings from teacher, parent, and student surveys suggest the presence of modest impact of homework in the area of emotional health (namely, student report of boredom and frustration ), parent–child relationships (with over 25% of the parent and child samples reporting homework always or often interferes with family time and creates a power struggle ), and sleep (36.8% of the children surveyed reported they sometimes get less sleep) in grades 3–6. Additionally, findings suggest misperceptions surrounding the existence of homework policies among parents and teachers, the reasons teachers cite assigning homework, and a disconnect between child-reported and teacher reported emotional impact of homework.

Conclusions

Preliminary findings suggest homework modestly impacts child well-being in various domains in grades 3–6, including sleep, emotional health, and parent/child relationships. School districts, educators, and parents must continue to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support children’s overall well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding the Quality of Effective Homework

Relationships between perceived parental involvement in homework, student homework behaviors, and academic achievement: differences among elementary, junior high, and high school students.

Collaboration between School and Home to Improve Subjective Well-being: A New Chinese Children’s Subjective Well-being Scale

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s social-emotional health is moving to the forefront of attention in schools, as depression, anxiety, and suicide rates are on the rise (Bitsko et al. 2018 ; Child Mind Institute 2016 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Perou et al. 2013 ). This comes at a time when there are also intense academic demands, including an increased focus on academic achievement via grades, standardized test scores, and larger amounts of assigned homework (Pope 2010 ). This interplay between the rise in anxiety and depression and scholastic demands has been postulated upon frequently in the literature, and though some research has looked at homework stress as it relates to middle and high school students (Cech 2008 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Kackar et al. 2011 ; Katz et al. 2012 ), research evidence is scant as to the effects of academic stress on the social and emotional health of elementary children.

Literature Review

The following review of the literature highlights areas that are most pertinent to the child, including homework as it relates to achievement, the achievement gap, mental health, sleep, and parent–child relationships. Areas of educational policy, teacher training, homework policy, and parent-teacher communication around homework are also explored.

Homework and Achievement

With the authorization of No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards, teachers have felt added pressures to keep up with the tougher standards movement (Tokarski 2011 ). Additionally, teachers report homework is necessary in order to complete state-mandated material (Holte 2015 ). Misconceptions on the effectiveness of homework and student achievement have led many teachers to increase the amount of homework assigned. However, there has been little evidence to support this trend. In fact, there is a significant body of research demonstrating the lack of correlation between homework and student success, particularly at the elementary level. In a meta-analysis examining homework, grades, and standardized test scores, Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) found little correlation between the amount of homework assigned and achievement in elementary school, and only a moderate correlation in middle school. In third grade and below, there was a negative correlation found between the variables ( r = − 0.04). Other studies, too, have evidenced no relationship, and even a negative relationship in some grades, between the amount of time spent on homework and academic achievement (Horsley and Walker 2013 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ). High levels of homework in competitive high schools were found to hinder learning, full academic engagement, and well-being (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Ironically, research suggests that reducing academic pressures can actually increase children’s academic success and cognitive abilities (American Psychological Association [APA] 2014 ).

International comparison studies of achievement show that national achievement is higher in countries that assign less homework (Baines and Slutsky 2009 ; Güven and Akçay 2019 ). In fact, in a recent international study conducted by Güven and Akçay ( 2019 ), there was no relationship found between math homework frequency and student achievement for fourth grade students in the majority of the countries studied, including the United States. Similarly, additional homework in science, English, and history was found to have little to no impact on respective test scores in later grades (Eren and Henderson 2011 ). In the 2015 “Programme of International Student Assessment” results, Korea and Finland are ranked among the top countries in reading, mathematics, and writing, yet these countries are among those that assign the least amount of homework (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2016 ).

Homework and Mental Wellness

Academic stress has been found to play a role in the mental well-being of children. In a study conducted by Conner et al. ( 2009 ), students reported feeling overwhelmed and burdened by their exceeding homework loads, even when they viewed homework as meaningful. Academic stress, specifically the amount of homework assigned, has been identified as a common risk factor for children’s increased anxiety levels (APA 2009 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Leung et al. 2010 ), in addition to somatic complaints and sleep disturbance (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Stress also negatively impacts cognition, including memory, executive functioning, motor skills, and immune response (Westheimer et al. 2011 ). Consequently, excessive stress impacts one’s ability to think critically, recall information, and make decisions (Carrion and Wong 2012 ).

Homework and Sleep

Sleep, including quantity and quality, is one life domain commonly impacted by homework and stress. Zhou et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors in school-aged children, with findings suggesting that staying up late to study was one of the leading risk factors most associated with severe tiredness and depression. According to the National Sleep Foundation ( 2017 ), the recommended amount of sleep for elementary school-aged children is 9 – 11 h per night; however, approximately 70% of youth do not get these recommended hours. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), elementary-aged children also acknowledge lack of sleep. Perfect et al. ( 2014 ) found that sleep problems predict lower grades and negative student attitudes toward teachers and school. Eide and Showalter ( 2012 ) conducted a national study that examined the relationship between optimum amounts of sleep and student performance on standardized tests, with results indicating significant correlations ( r = 0.285–0.593) between sleep and student performance. Therefore, sleep is not only impacted by academic stress and homework, but lack of sleep can also impact academic functioning.

Homework and the Achievement Gap

Homework creates increasing achievement variability among privileged learners and those who are not. For example, learners with more resources, increased parental education, and family support are likely to have higher achievement on homework (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; Moore et al. 2018 ; Ndebele 2015 ; OECD 2016 ). Learners coming from a lower socioeconomic status may not have access to quiet, well-lit environments, computers, and books necessary to complete their homework (Cooper 2001 ; Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Additionally, many homework assignments require materials that may be limited for some families, including supplies for projects, technology, and transportation. Based on the research to date, the phrase “the homework gap” has been coined to describe those learners who lack the resources necessary to complete assigned homework (Moore et al. 2018 ).

Parent–Teacher Communication Around Homework

Communication between caregivers and teachers is essential. Unfortunately, research suggests parents and teachers often have limited communication regarding homework assignments. Markow et al. ( 2007 ) found most parents (73%) report communicating with their child’s teacher regarding homework assignments less than once a month. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) indicated children in primary grades spend substantially more time on homework than predicted by educators. For example, they found first grade students had three times more homework than the National Education Association’s recommendation of up to 20 min of homework per night for first graders. While the same homework assignment may take some learners 30 min to complete, it may take others up to 2 or 3 h. However, until parents and teachers have better communication around homework, including time completion and learning styles for individual learners, these misperceptions and disparities will likely persist.

Parent–Child Relationships and Homework

Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) defined homework as a “double-edged sword” when it comes to the parent–child relationship. While some parental support can be construed as beneficial, parental support can also be experienced as intrusive or detrimental. When examining parental homework styles, a controlling approach was negatively associated with student effort and emotions toward homework (Trautwein et al. 2009 ). Research suggests that homework is a primary source of stress, power struggle, and disagreement among families (Cameron and Bartel 2009 ), with many families struggling with nightly homework battles, including serious arguments between parents and their children over homework (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). Often, parents are not only held accountable for monitoring homework completion, they may also be accountable for teaching, re-teaching, and providing materials. This is particularly challenging due to the economic and educational diversity of families. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) found that as parents’ personal perceptions of their abilities to assist their children with homework declined, family-related stressors increased.

Teacher Training