Social Institutions in Sociology: Definition & Examples

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- A social institution is a group or organization that has specific roles, norms, and expectations, which functions to meet the social needs of society. The family, government, religion, education, and media are all examples of social institutions.

- Social institutions are interdependent and continually interact and influence one another in everyday society. For example, some religious institutions believe they should have control over governmental and educational institutions.

- Social institutions can have both manifest and latent functions . Manifest functions are those that are explicitly stated, while latent functions are not.

- Each social institution plays a vital role in the functioning of society and the lives of the people that inhabit them.

What Are Social Institutions?

Social institutions are the organizations in society that influence how society is structured and functions. They include family, media, education, and the government.

A social institution is an established practice, tradition, behavior, or system of roles and relationships that is considered a normative structure or arrangement within a society.

Bogardus – “A social institution is a structure of society that is organized to meet the needs of people chiefly through well-established procedures.”

H. E. Barnes – “Social institutions are the social structure & machinery through which human society organizes, directs & executes the multifarious activities required to society for human need.”

Broadly, they are patterns of behavior grouped around the central needs of human beings in a society. One such example of an institution is marriage, where multiple people commit to follow certain rules and acquire a familial legal status about each other (Miller, 2007).

Social institutions have several key characteristics:

- They are enduring and stable.

- They serve a purpose, ideally providing better chances for human survival and flourishing.

- They have roles that need to be filled.

- Governing the behavior and expectations of sets of individuals within a given community.

- The rules that govern them are usually ingrained in the basic cultural values of a society, as each institution consists of a complex cluster of social norms .

They also serve general functions, including:

- Allocating resources

- Creating meaning

- Maintaining order

- Growing society and its influence

Examples (and Functions)

The five major social institutions in sociology are family, education, religion, government (political), and the economy.

The family is one of the most important social institutions. It is considered a “building block” of society because it is the primary unit through which socialization occurs.

It is a social unit created by blood, marriage, or adoption, and can be described as nuclear, consisting of two parents and their children, or extended, encompassing other relatives. Although families differ widely around the world, families across cultures share certain common concerns in their everyday lives (Little & McGivern, 2020).

As a social institution, the family serves numerous, multifaceted functions. The family socializes its members by teaching them values, beliefs, and norms.

It also provides emotional support and economic stability. Sometimes, the family may even be a caretaker if one of its members is sick or disabled (Little & McGivern, 2020).

Historically, the family has been the central social institution of Western societies. However, more recently, as sociologists have observed, other social institutions have replaced the family in providing key functions, as family sizes have shrunk and provided more distant ties.

For example, modern schools have, in part, taken on the role of socializing children, and workplaces can provide shared meaning.

- Functions of The Family (Marxism)

- Functionalist Perspective of the Family

E. Durkheim – “Education can be conceived as the socialization of the younger generation. It is a continuous effort to impose on the child ways of seeing, feeling and acting which he could not arrived at spontaneously.”

John J. Macionis – “Education is the social institution through which society provides its members with important knowledge, including basic facts, jobs, skills & cultural norms & values .”

As a social institution, education helps to socialize children and young adults by teaching them the norms, values, and beliefs of their culture. It also transmits cultural heritage from one generation to the next. Education also provides people with the skills and knowledge they need to function in society.

Education may also help to reduce crime rates by providing people with alternatives to criminal activity. These are the “manifest” or openly stated functions and intended goals of education as a social institution (Meyer, 1977).

Education, sociologists have argued, also has a number of latent, or hidden and unstated functions. This can include courtship, the development of social networks, improving the ability for students to work in groups, the creation of a generation gap, and political and social integration (Little & McGivern, 2020).

Although every country in the world is equipped with some form of education system, these systems, as well as the values and teaching philosophies of those who run the systems, vary greatly. Generally, a country”s wealth is directly proportional to the quality of its educational system.

For example, in poor countries, education may be seen as a luxury that only the wealthy can afford, while in rich countries, education is more accessible to a wider range of people.

This is because, in poorer countries, money is often spent on more pressing needs such as food and shelter, diminishing financial and time investments in education (Little & McGivern, 2016).

Religion is another social institution that plays a significant role in society. It is an organized system of beliefs and practices designed to fill the human need for meaning and purpose (Durkheim, 1915).

According to Durkheim, “Religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden.”

According to Ogburn, “Religion is an attitude towards superhuman powers.”

Religion can be used to instill moral values and socialize individuals into a community. Religion plays a significant role in shaping the way people view themselves and the world around them.

It can provide comfort and security to those in need. Large religions may also provide a basis for community support, establishing institutions of their own, such as hospitals and schools.

Additionally, it can be used as a form of political control or as a source of conflict. Different sociologists have commented on the broad-scale societal effects of religion.

Max Weber , for example, believed that religion could be a force for social change, while Karl Marx viewed religion as a tool used by capitalist societies to perpetuate inequality (Little & McGivern, 2016).

The government is another social institution that plays a vital role in society. It is responsible for maintaining order, protecting citizens from harm, and providing for the common good.

The government does this through various sub-institutions and agencies, such as the police, the military, and the courts. These legal institutions regulate society and prevent crime by enforcing laws and policies.

The government also provides social services, such as education and healthcare, ensuring the general welfare of a country or region”s citizens (Little & McGivern, 2016).

The economy is a social institution that is responsible for the production and distribution of goods and services. It is also responsible for the exchange of money and other resources.

The economy is often divided into three sectors: the primary sector, the secondary sector, and the tertiary sector (Little & McGivern, 2016).

The primary sector includes all industries that are concerned with the extraction and production of natural resources, such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining.

The secondary sector includes all industries that are concerned with the processing of raw materials into finished products, such as manufacturing and construction.

The tertiary sector includes all industries that provide services to individuals and businesses, such as education, healthcare, and tourism (Little & McGivern, 2016).

Barnes, H. E. (1942). Social institutions. New York , 29.

Bogardus, E. S. (1922). A history of social thought . University of Southern California Press.

Bogardus, E. S. (1960). development of social thought .

Durkheim, E. (2006). Durkheim: Essays on morals and education (Vol. 1). Taylor & Francis.

Durkheim, E. (2016). The elementary forms of religious life. In Social Theory Re-Wired (pp. 52-67). Routledge.

Little, W., McGivern, R., & Kerins, N. (2016). Introduction to sociology-2nd Canadian edition . BC Campus.

Macionis, J. J., & Plummer, K. (2005). Sociology: A global introduction . Pearson Education.

Meyer, J. W. (1977). The effects of education as an institution . American Journal of Sociology , 83 (1), 55-77.

Ogburn, W. F. (1937). The influence of inventions on American social institutions in the future. American Journal of Sociology , 43 (3), 365-376.

Miller, S. (2007). Social institutions In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Schotter, A. (2008). The economic theory of social institutions. Cambridge Books .

Weber, M. (1936). Social actions .

What are Social Institutions in Sociology?

In sociology, social institutions are established norms and subsystems that support each society’s survival. These institutions are a key part of the structure of society. They include the family, education, religion, and economic and political institutions.

These institutions are not just physical structures or organizations but also the norms and rules that govern our behavior and attitudes, shaping our social interactions and society at large.

What is the role of a social institution?

Each social institution serves a specific role and function in society, and they work together to maintain the overall stability and survival of society.

For instance, the family institution is responsible for societal roles related to birth, upbringing, and socialization. The educational institution imparts knowledge and skills to individuals so they can contribute productively to society.

7.2 Education as a Social Institution

When you consider your COVID education story, it is likely that your education journey was interrupted in some way. You might have turned to YouTube to teach your second grader math. You might have needed a break and learned the latest dance step on Tik-Tok. All of us learn differently, and use many methods to figure things out.

The two minute video in figure 7.3 shows some of the ways that the Martu people of Australia hunt with fire. As you watch, please consider the following questions:

- Who is doing the hunting? Does this surprise you?

- What is the indigenous teaching around hunting and land stewardship?

- Using your imagination, how might this practice of hunting and stewardship be learned?

Figure 7.3. Fire Hunting in Australia [YouTube Video] (time: 2:01).

Traditionally, learning involves storytelling and practice. For the Martu people in Australia, the practices of hunting are taught by stories and experience. In this video, we see hunting practices using fire practiced by women who are hunting monitor lizards (figure 7.3). The women use controlled burns to catch and kill the lizards. In addition, the fire itself makes the landscape more useful for lizard habitat.

As a young person, you might learn about hunting by listening to the stories the hunters tell about the hunt that happened today. Or you might help skin the animals once they were caught. Today, the Martu also have access to schools, and can learn to read and write (Scelza n.d.), in addition to learning through lived experience..

When sociologists look at learning they are more likely to focus on the institution and inequality, in addition to interactions that may happen in the classroom. In this basic sociological definition education is a social institution through which members of a society are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms (Conerly et al. 2021). In this view, students learn not just reading and writing, but how to follow directions, and how to participate in social activities, even things as simple as standing in line.

As we’ve seen in other chapters in this book, education can be a driver of social change and a means of maintaining a status quo that does not serve everyone well. On one hand, education can be a cause of social change. For example, teaching girls to read and write is a component in decreasing poverty in many countries. In other circumstances education serves to reproduce structures of inequality. In the United States, families who are poor receive less access to quality education. How then are we to make sense of this complicated social institution?

7.2.1 Education and the Rise of Democracy

When we think about education as an institution, we consider the function that it serves in our society. According to the U.S. founding fathers, education served the function of creating responsible citizens. Like other revolutionaries of the time, they argued that if people could read and write, they could also decide for themselves. This idea of government serving at the will of the people, which was revolutionary at the time, depended on the people to make informed choices. In other words,

For America’s founders, public education was essential to keeping the republic. Thomas Jefferson famously proclaimed that of all the arguments for education, “none is more important, none more legitimate, than that of rendering the people safe, as they are the ultimate guardians of their own liberty.” (Neem 2019)

Creating a system of formal public education also served the function of stabilizing a new nation. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10 percent of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban and Wagoner 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.

Free, compulsory education, of course, applied only to primary and secondary schools. Until the mid-1900s, very few people went to college, and those who did typically came from fairly wealthy families. After World War II, however, college enrollments soared, and today more people are attending college than ever before, even though college attendance is still related to social class, as we shall discuss later in this chapter.

An important theme emerges from this brief history: Until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not White and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

7.2.2 Pierrre Bourdieu: The Reproduction of Economic Inequality through Cultural and Social Capital

Functionalist sociologists focus on the purpose that education serves. As we learned in the last section, literacy can support democracy. Conflict sociologists, on the other hand, look at what maintains unequal social power. They particularly use social class as part of their analysis.

When we apply this lens to education, we see that the fulfillment of one’s education is closely linked to social class. Students of low socioeconomic status are generally not afforded the same opportunities as students of higher status, no matter how great their academic ability or desire to learn. Picture a student from a working-class home who wants to do well in school. On a Monday, he’s assigned a paper that’s due Friday. Monday evening, he has to babysit his younger sister while his divorced mother works. Tuesday and Wednesday, he works stocking shelves after school until 10:00 p.m. By Thursday, the only day he might have available to work on that assignment, he’s so exhausted he can’t bring himself to start the paper. His mother, though she’d like to help him, is so tired herself that she isn’t able to give him the encouragement or support he needs. And since English is her second language, she has difficulty with some of his educational materials. They also lack a computer and printer at home, which most of his classmates have, so they have to rely on the public library or school system for access to technology. As this story shows, many students from working-class families have to contend with helping out at home, contributing financially to the family, poor study environments and a lack of support from their families. This is a difficult match with education systems that adhere to a traditional curriculum that is more easily understood and completed by students of higher social classes.

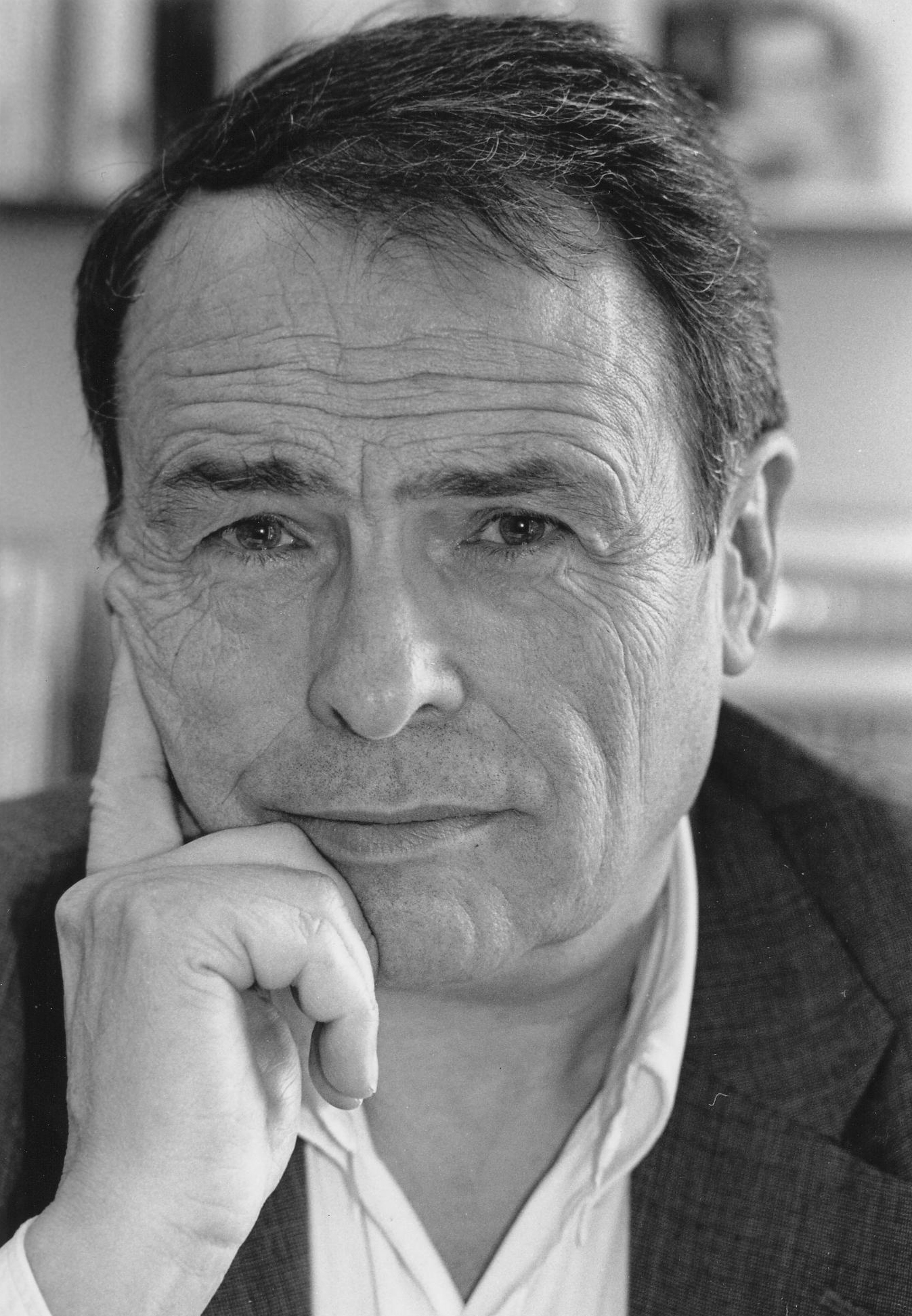

Figure 7.4. Photo of Pierre Bourdieu

Such a situation leads to maintaining social class across generations, extensively studied by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (figure 7.4). He researched how cultural capital , or cultural knowledge that serves (metaphorically) as currency that helps us navigate a culture, alters the experiences and opportunities available to French students from different social classes. His results from France have been applied also to students in other countries. Members of the upper and middle classes have more cultural capital than do families of lower-class status. As a result, the educational system maintains a cycle in which the dominant culture’s values are rewarded. Instruction and tests cater to the dominant culture and leave others struggling to identify with values and competencies outside their social class. For example, there has been a great deal of discussion over what standardized tests such as the SAT really measure. Many argue that the tests group students by cultural ability rather than by natural intelligence.

The cycle of rewarding those who possess cultural capital is found in formal educational curricula as well as in the hidden curriculum, which refers to the type of nonacademic knowledge that students learn through informal learning and cultural transmission. This hidden curriculum reinforces the positions of those with higher cultural capital and serves to bestow status unequally.

Conflict theorists point to tracking , a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities. While educators may believe that students do better in tracked classes because they are with students of similar ability and may have access to more individual attention from teachers, conflict theorists feel that tracking leads to self-fulfilling prophecies in which students live up (or down) to teacher and societal expectations ( Education Week 2004).

To conflict theorists, schools play the role of training working-class students to accept and retain their position as lower members of society. They argue that this role is fulfilled through the disparity of resources available to students in richer and poorer neighborhoods as well as through testing (Lauen and Tyson 2008).

IQ tests have been attacked for being biased—for testing cultural knowledge rather than actual intelligence. For example, a test item may ask students what instruments belong in an orchestra. To correctly answer this question requires certain cultural knowledge—knowledge most often held by more affluent people who typically have more exposure to orchestral music. Though experts in testing claim that bias has been eliminated from tests, conflict theorists maintain that this is impossible. These tests, to conflict theorists, are another way in which education does not provide opportunities, but instead maintains an established configuration of power.

7.2.3 Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools

As you might remember from Chapter 1 , though, we need to employ a more powerful equity lens to explore the institution of education. Already we see that even though our early politicians agreed that education was a requirement for country-building, many people were excluded. We notice that the institution serves the function of maintaining existing social classes. As we use our equity lens more powerfully, we see that the institution of education sometimes supports violent and oppressive social change. For this, we look at the history of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada, once described by the governments that funded them as Indian Residential Schools .

By establishing boarding schools for Indigenous children, colonizers committed genocide , the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. This is a strong claim, so let’s look at the evidence. In May 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report . The report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 Federal Indian Boarding Schools run between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws which required Indian parents to send their children to these boarding schools ( Newland 2022: 35). The explicit intention of the schools was to disrupt the families and the cultures of Indigenous people. Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022: 38). Because students were required to learn English and agriculture and punished if they spoke their Indigenous languages and practiced their own religious and spiritual practices, families and cultures were indeed destroyed.

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior, first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary.

Deb Haaland (figure 7.5), the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, describes this history in the following way:

>Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland also recounts the suffering in her own family. She writes: “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian, and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). The 2022 U.S. Federal report documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021).

Figure 7.6. Photo of the Chemawa Indian School, Salem Oregon, no date.

The U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children to attend Indian Residential Schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition n.d.). Oregon shares this painful history. Historian Eva Guggemos and volunteer historian SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University combed the historical record for the Forest Grove Indian Training School in Forest Grove, which became the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (figure 7.6). They found that at least 270 children had died while at these schools. Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases.

Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural hegemony , achieving authority, dominance, and influence of one group, nation, or society over another group, nation, or society; typically through cultural, economic, or political means. In this case, the colonizers valued their own White, European culture, and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in figure 7.7 and 7.8 tell a story of change and assimilation.

Figure 7.7. Caption from website: A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.”

Figure 7.8 Caption from Website: Seven months later — the students pictured are probably the Spokane students who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief. A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck. Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse. The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures. (Francis 2019)

The function of education in the case of Indian Boarding Schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. Education functioned to purposefully disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to Indian education were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. This is a concrete example of land grabbing, a practice you learned about in Chapter 4 . Jefferson wrote,

>To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21).

By removing people from the land, and children from families, the US Government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, an indirect but purposeful function of education.

7.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Institution

“Education as a Social Institution” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Education and the Rise of Democracy, partially based on Social Problems Continuity and Change – An Overview of Education https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_social-problems-continuity-and-change/s14-01-an-overview-of-education-in-th.html University of Minnesota Licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 lightly edited

Pierre Bourdeau: Credentialism/Cultural Capital

Introduction to Sociology 3e – Theoretical Perspectives on Education

CC-BY 4.0 lightly edited

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/16-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-education

Figure 7.3. Figure Hunting In Australia. https://youtu.be/j8zb44roDTM

Figure 7.4. Pierre Bourdieu Bernard Lambert, own work, CC-BY-SA 4.0 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Bourdieu#/media/File:Pierre_Bourdieu_(1).jpg

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deb_Haaland_official_portrait,_116th_congress_2.jpg U.S. House Office of Photography 2019 Public Domain

Figure 7.6. Chemawa Indian School https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/or0051.photos.130102p/resource/ Public Domain

Figure 7.7. https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain

Figure 7.8. . https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain

Social Change in Societies Copyright © by Aimee Samara Krouskop. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Science, Tech, Math ›

- Social Sciences ›

- Sociology ›

The Sociology of Education

Studying the Relationships Between Education and Society

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

The sociology of education is a diverse and vibrant subfield that features theory and research focused on how education as a social institution is affected by and affects other social institutions and the social structure overall, and how various social forces shape the policies, practices, and outcomes of schooling .

While education is typically viewed in most societies as a pathway to personal development, success, and social mobility, and as a cornerstone of democracy, sociologists who study education take a critical view of these assumptions to study how the institution actually operates within society. They consider what other social functions education might have, like for example socialization into gender and class roles, and what other social outcomes contemporary educational institutions might produce, like reproducing class and racial hierarchies, among others.

Theoretical Approaches within the Sociology of Education

Classical French sociologist Émile Durkheim was one of the first sociologists to consider the social function of education. He believed that moral education was necessary for society to exist because it provided the basis for the social solidarity that held society together. By writing about education in this way, Durkheim established the functionalist perspective on education . This perspective champions the work of socialization that takes place within the educational institution, including the teaching of society’s culture, including moral values, ethics, politics, religious beliefs, habits, and norms. According to this view, the socializing function of education also serves to promote social control and to curb deviant behavior.

The symbolic interaction approach to studying education focuses on interactions during the schooling process and the outcomes of those interactions. For instance, interactions between students and teachers, and social forces that shape those interactions like race, class, and gender, create expectations on both parts. Teachers expect certain behaviors from certain students, and those expectations, when communicated to students through interaction, can actually produce those very behaviors. This is called the “teacher expectancy effect.” For example, if a white teacher expects a Black student to perform below average on a math test when compared to white students, over time the teacher may act in ways that encourage Black students to underperform.

Stemming from Marx's theory of the relationship between workers and capitalism, the conflict theory approach to education examines the way educational institutions and the hierarchy of degree levels contribute to the reproduction of hierarchies and inequalities in society. This approach recognizes that schooling reflects class, racial, and gender stratification, and tends to reproduce it. For example, sociologists have documented in many different settings how "tracking" of students based on class, race, and gender effectively sorts students into classes of laborers and managers/entrepreneurs, which reproduces the already existing class structure rather than producing social mobility.

Sociologists who work from this perspective also assert that educational institutions and school curricula are products of the dominant worldviews, beliefs, and values of the majority, which typically produces educational experiences that marginalize and disadvantage those in the minority in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability, among other things. By operating in this fashion, the educational institution is involved in the work of reproducing power, domination, oppression, and inequality within society . It is for this reason that there have long been campaigns across the U.S. to include ethnic studies courses in middle schools and high schools, in order to balance a curriculum otherwise structured by a white, colonialist worldview. In fact, sociologists have found that providing ethnic studies courses to students of color who are on the brink of failing out or dropping out of high school effectively re-engages and inspires them, raises their overall grade point average and improves their academic performance overall.

Notable Sociological Studies of Education

- Learning to Labour , 1977, by Paul Willis. An ethnographic study set in England focused on the reproduction of the working class within the school system.

- Preparing for Power: America's Elite Boarding Schools , 1987, by Cookson and Persell . An ethnographic study set at elite boarding schools in the U.S. focused on the reproduction of the social and economic elite.

- Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity , 2003, by Julie Bettie. An ethnographic study of how gender, race, and class intersect within the schooling experience to leave some without the cultural capital necessary for social mobility within society.

- Academic Profiling: Latinos, Asian Americans, and the Achievement Gap , 2013, by Gilda Ochoa. An ethnographic study within a California high school of how race, class, and gender intersect to produce the "achievement gap" between Latinos and Asian Americans.

- Applied and Clinical Sociology

- All About Marxist Sociology

- Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

- A Brief Biography of Pierre Bourdieu

- Robert K. Merton

- Introduction to Sociology

- Full-Text Sociology Journals Online

- A Biography of Erving Goffman

- The Sociology of Gender

- Famous Sociologists

- Anthony Giddens: Biography of British Sociologist

- The Sociology of Consumption

- Definition and Overview of Grounded Theory

- Juergen Habermas

- Conducting Case Study Research in Sociology

- Biography of Patricia Hill Collins, Esteemed Sociologist

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

16.3 Education in the United States

Learning objectives.

- Summarize social class, gender, and racial and ethnic differences in educational attainment.

- Describe the impact that education has on income.

- Discuss how education affects social and moral attitudes.

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. About 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through 8, 16 million in high school, and 19 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 2-year and 4-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

About 65% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For these reasons, educational attainment depends heavily on family income and race and ethnicity.

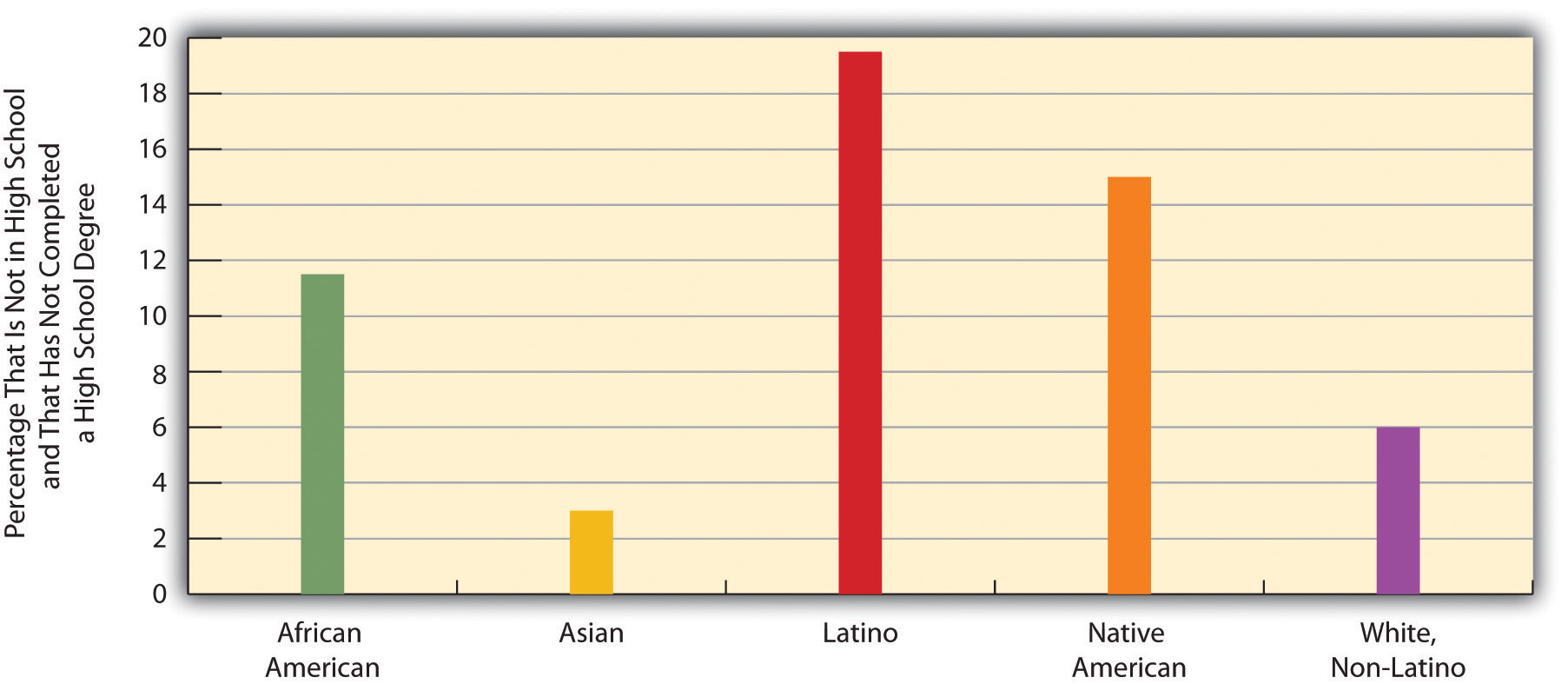

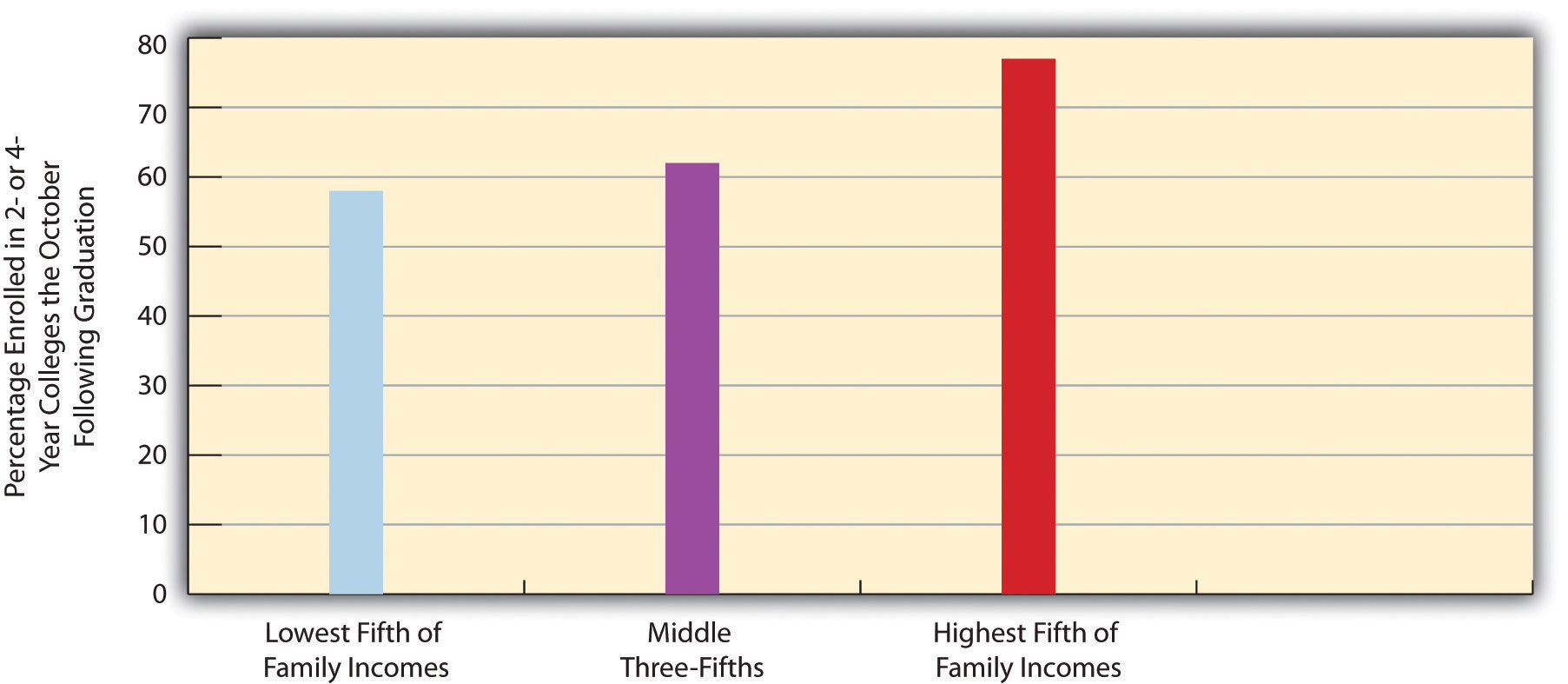

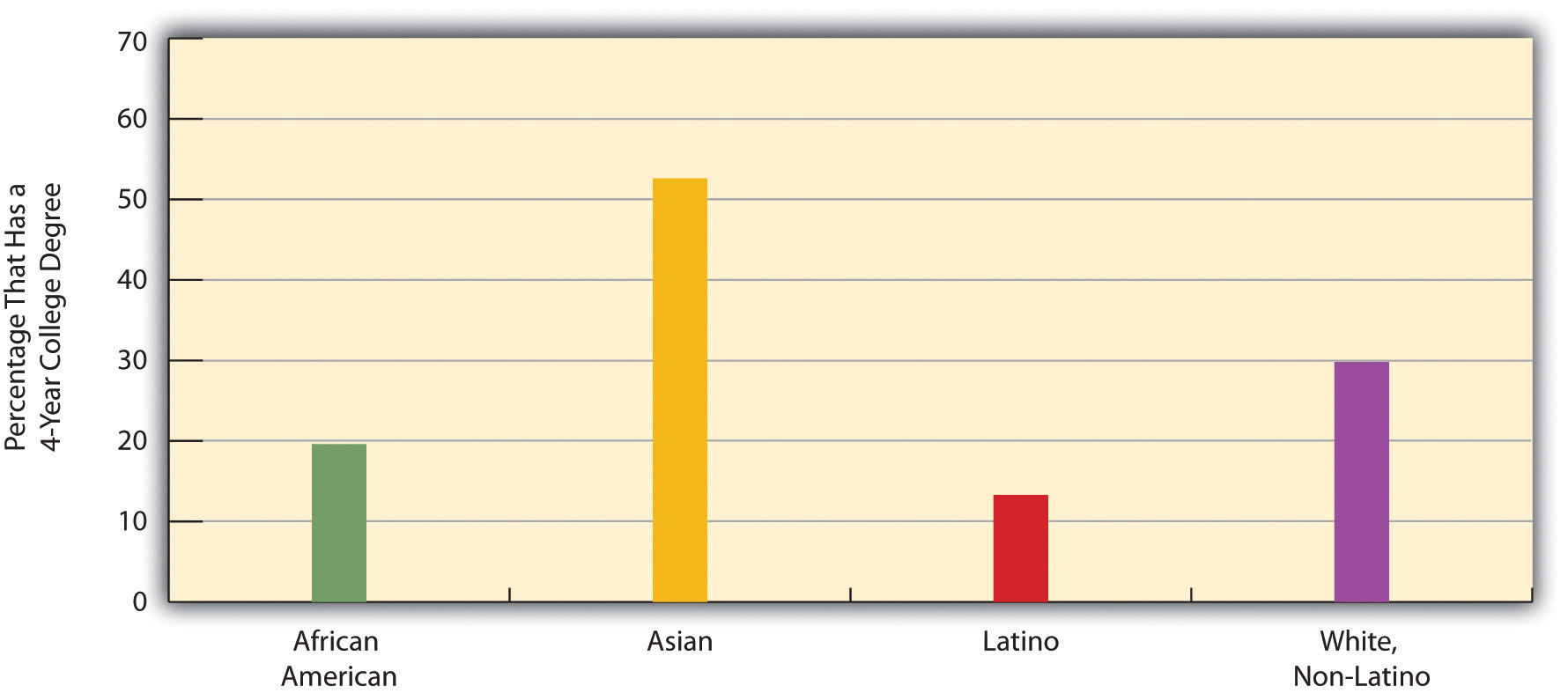

Figure 16.2 “Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007” shows how race and ethnicity affect dropping out of high school. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites. One way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation. As Figure 16.3 “Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007” shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. For race/ethnicity, it is useful to see the percentage of persons 25 or older who have at least a 4-year college degree. As Figure 16.4 “Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008” shows, this percentage varies significantly, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree.

Figure 16.2 Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007

Source: Data from Planty, M., Hussar, W., Snyder, T., Kena, G., KewalRamani, A., Kemp, J.,…Nachazel, T. (2009). The condition of education 2009 (NCES 2009-081). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Figure 16.3 Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007

Figure 16.4 Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab .

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).

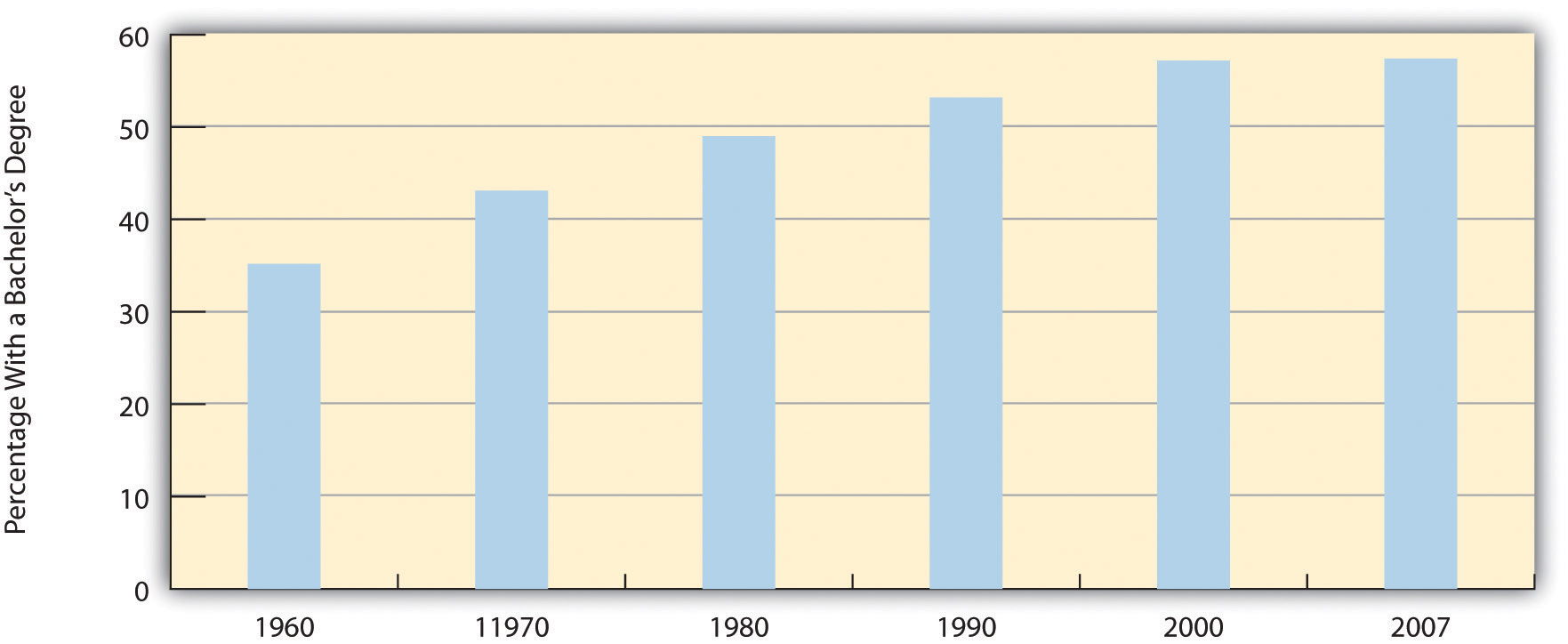

Does gender affect educational attainment? The answer is yes, but perhaps not in the way you expect. If we do not take age into account, slightly more men than women have a college degree: 30.1% of men and 28.8% of women. This difference reflects the fact that women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college. But now there is a gender difference in the other direction: women now earn more than 57% of all bachelor’s degrees, up from just 35% in 1960 (see Figure 16.5 “Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007” ).

Figure 16.5 Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007

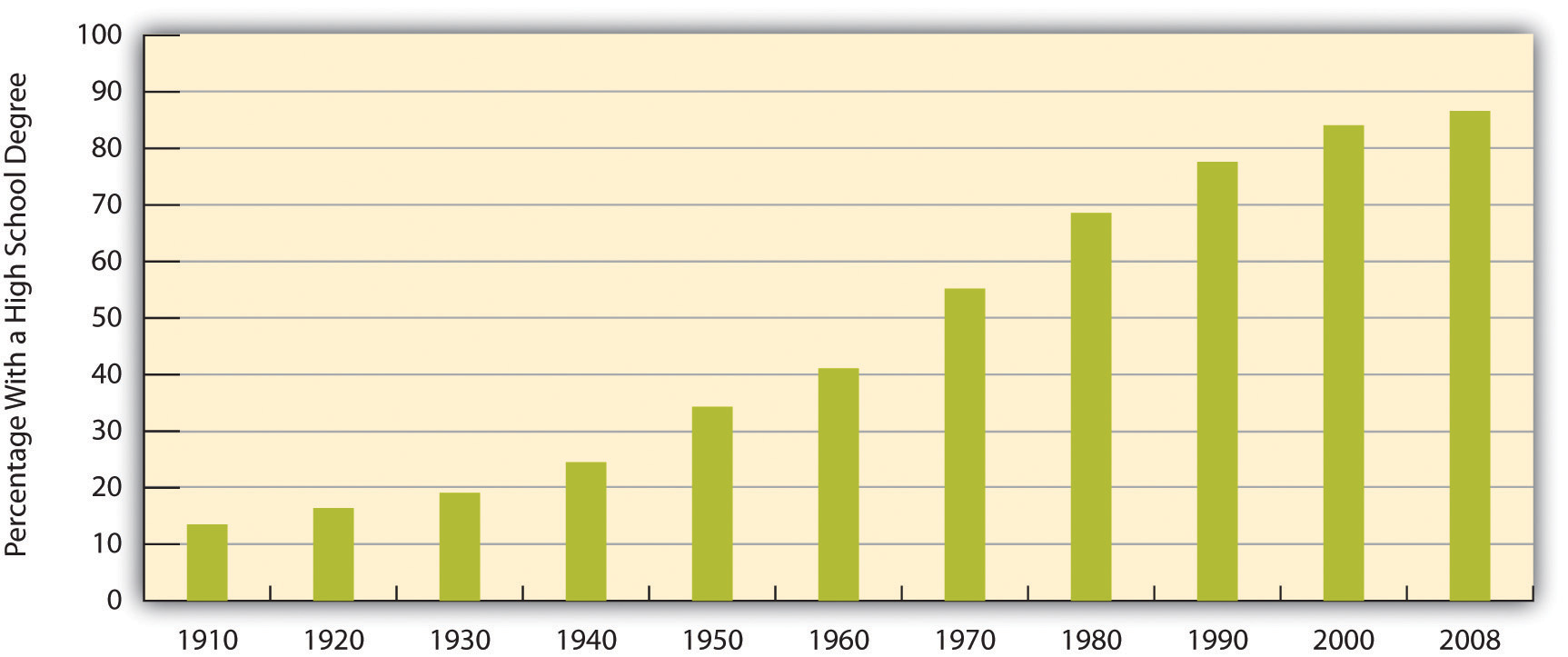

The Difference Education Makes: Income

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential society (Collins, 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. Over the years the ante has been upped considerably, as in earlier generations a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with (see Figure 16.6 “Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008” ). With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then, too, today’s technological and knowledge-based postindustrial society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

Figure 16.6 Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008

Source: Data from Snyder, T. D., Dillow, S. A., & Hoffman, C. M. (2009). Digest of education statistics 2008 . Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

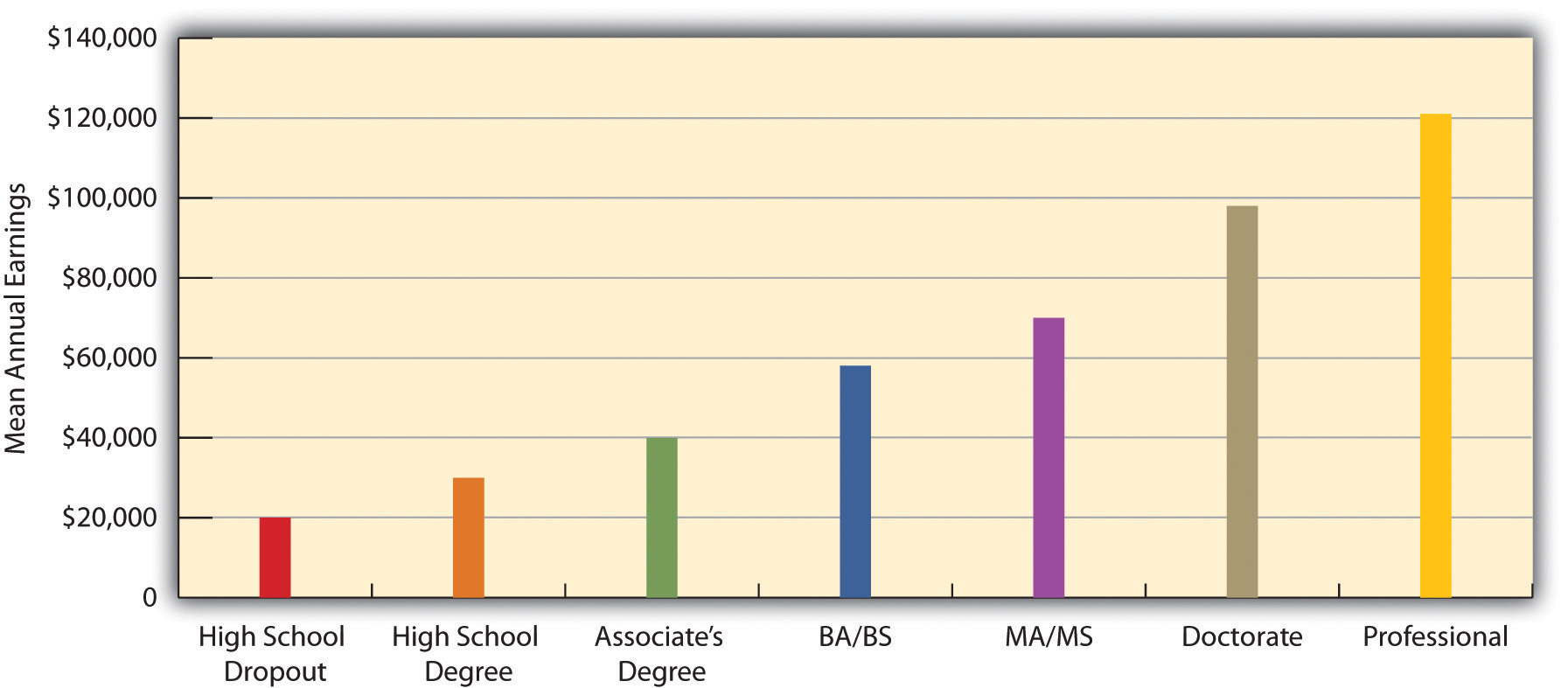

A credential society also means that people with more educational attainment achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see Figure 16.7 “Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007” ). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

On the average, college graduates have much higher annual earnings than high school graduates. How much does this consequence affect why you decided to go to college?

Merrimack College – Commencement 2012 – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 16.7 Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007

The Difference Education Makes: Attitudes

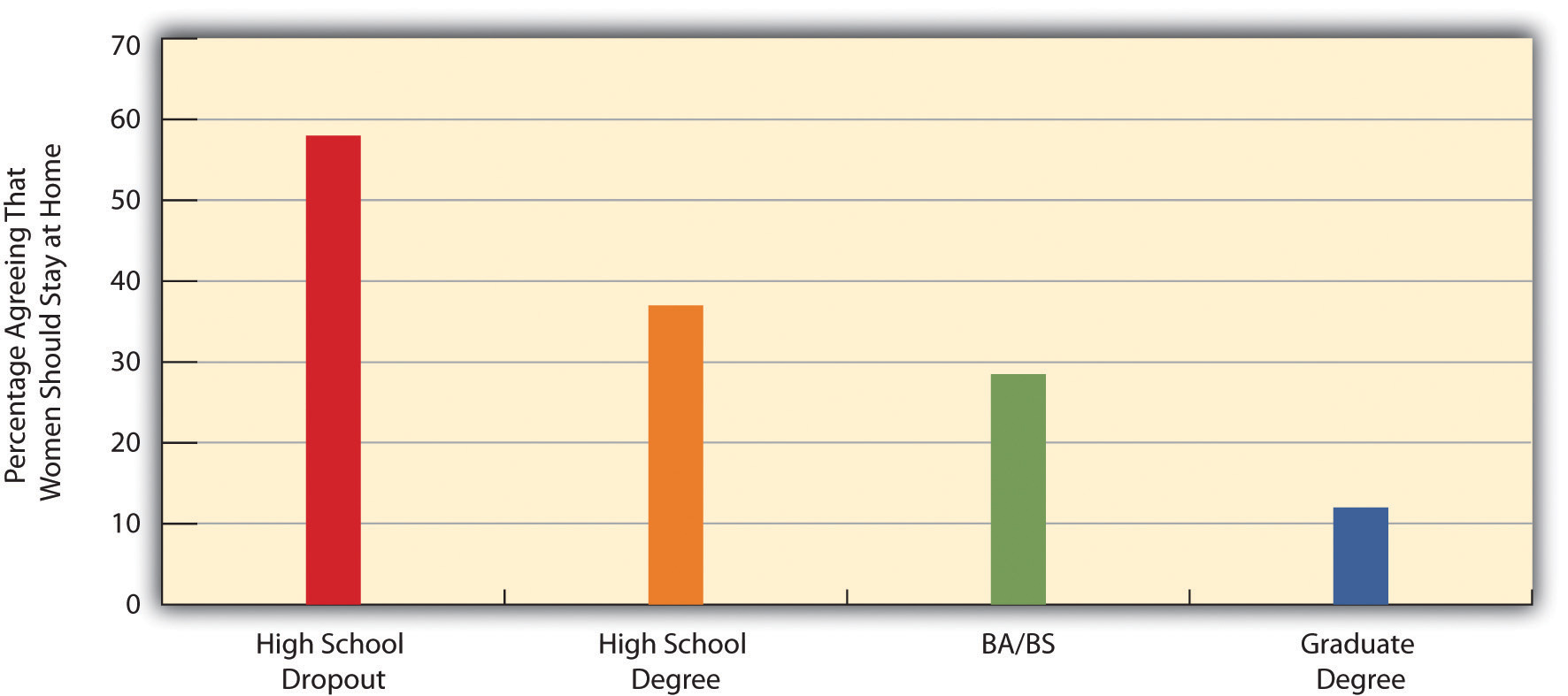

Education also makes a difference for our attitudes. Researchers use different strategies to determine this effect. They compare adults with different levels of education; they compare college seniors with first-year college students; and sometimes they even study a group of students when they begin college and again when they are about to graduate. However they do so, they typically find that education leads us to be more tolerant and even approving of nontraditional beliefs and behaviors and less likely to hold various kinds of prejudices (McClelland & Linnander, 2006; Moore & Ovadia, 2006). Racial prejudice and sexism, two types of belief explored in previous chapters, all reduce with education. Education has these effects because the material we learn in classes and the experiences we undergo with greater schooling all teach us new things and challenge traditional ways of thinking and acting.

We see evidence of education’s effect in Figure 16.8 “Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”” , which depicts the relationship in the General Social Survey between education and agreement with the statement that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” College-educated respondents are much less likely than those without a high school degree to agree with this statement.

Figure 16.8 Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

Key Takeaways

- Social class, race and ethnicity, and gender all influence the degree of educational attainment.

- Education has a significant impact both on income and on social and cultural attitudes. Higher levels of education are associated with higher incomes and with less conservative beliefs on social and cultural issues.

For Your Review

- Do you think the government should take steps to try to reduce racial and ethnic differences in education, or do you think it should take a hands-off approach? Explain your answer.

- Why do you think lower levels of education are associated with more conservative beliefs on social and cultural issues? What is it about education that often leads to less conservative beliefs on these issues?

Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2009). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Collins, R. (1979). The credential society: An historical sociology of education and stratification . New York, NY: Academic Press.

McClelland, K., & Linnander, E. (2006). The role of contact and information in racial attitude change among white college students. Sociological Inquiry, 76 (1), 81–115.

Moore, L. M., & Ovadia, S. (2006). Accounting for spatial variation in tolerance: The effects of education and religion. Social Forces, 84 (4), 2205–2222.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab .

Yeung, W.-J. J., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (2009). The black-white test score gap and early home environment. Social Science Research, 38 (2), 412–437.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

IMAGES

VIDEO