Behaviorism as a Theory of Personality: A Critical Look

This paper explores the theory of behaviorism and evaluates its effectiveness as a theory of personality. It takes into consideration all aspects of the behaviorism theory, including Pavlov's classical conditioning and Skinner's operant conditioning. Additional research in this field by scientists such as Thorndike is also included. As a result of this critical look at behaviorism, its weaknesses as a comprehensive personality theory are revealed. At the same time, its merits when restricted to certain areas of psychology and treatment of disorders are discussed.

For as long as human beings can remember, they have always been interested in what makes them who they are and what aspects of their being set each of them apart from others of their species. The answer according to behaviorists is nothing more than the world in which they grew up. Behaviorism is the theory that human nature can be fully understood by the laws inherent in the natural environment. As one of the oldest theories of personality, behaviorism dates back to Descartes, who introduced the idea of a stimulus and called the person a machine dependent on external events whose soul was the ghost in the machine. Behaviorism takes this idea to another level. Although most theories operate to some degree on the assumption that humans have some sort of free will and are moral thinking entities, behaviorism refuses to acknowledge the internal workings of persons. In the mind of the behaviorist, persons are nothing more than simple mediators between behavior and the environment (Skinner, 1993, p 428). The dismissal of the internal workings of human beings leads to one problem opponents have with the behavioral theory. This, along with its incapability of explaining the human phenomenon of language and memory, build a convincing case against behaviorism as a comprehensive theory. Yet although these criticisms indicate its comprehensive failure, they do not deny that behaviorism and its ideas have much to teach the world about the particular behaviors expressed by humankind. The Theory of Behaviorism Classical Conditioning The Pavlovian experiment. While studying digestive reflexes in dogs, Russian scientist, Pavlov, made the discovery that led to the real beginnings of behavioral theory. He could reliably predict that dogs would salivate when food was placed in the mouth through a reflex called the "salivary reflex" in digestion. Yet he soon realized that, after time, the salivary reflex occurred even before the food was offered. Because the sound of the door and the sight of the attendant carrying the food "had repeatedly and reliably preceded the delivery of food to the mouth in the past," the dogs had transferred the reflex to these events (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, p. 21). Thus, the dogs began salivating simply at the door's sound and the attendant's presence. Pavlov continued experimenting with the dogs using a tone to signal for food. He found that the results matched and the dogs had begun to salivate with the tone and without food (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, pp. 20-24). What Pavlov discovered was first order conditioning. In this process, a neutral stimulus that causes no natural response in an organism is associated with an unconditioned stimulus, an event that automatically or naturally causes a response. This usually temporal association causes the response to the unconditioned stimulus, the unconditioned response, to transfer to the neutral stimulus. The unconditioned stimulus no longer needs to be there for the response to occur in the presence of the formerly neutral stimulus. Given that this response is not natural and has to be learned, the response is now a conditioned response and the neutral stimulus is now a conditioned stimulus. In Pavlov's experiment the tone was the neutral stimulus that was associated with the unconditioned stimulus of food. The unconditioned response of salivation became a conditioned response to the newly conditioned stimulus of the tone (Beecroft, 1966, pp. 8-10). Second order conditioning. When another neutral stimulus is introduced and associated with the conditioned stimulus, even further conditioning takes place. The conditioned response trained to occur only after the conditioned stimulus now transfers to the neutral stimulus making it another conditioned stimulus. Now the second conditioned stimulus can cause the response without both the first conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus. Thus, many new conditioned responses can be learned (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, p 48). When second order or even first order conditioning occur with frightening unconditioned stimuli, phobias or irrational fears develop. In a study performed by Watson and Rayner (1920), an intense fear of rats was generated in a little boy named Albert. Whenever Albert would reach for a rat, the researchers would make a loud noise and scare him. Through classical conditioning, Albert associated rats with the loud fearful noise and transferred his fear with the noise to fear of rats. He then went further and associated rats, which are furry, to all furry objects. Due to second order conditioning, little Albert formed an irrational fear of all furry objects (Mischel, 1993, pp. 298-299). Modern classical conditioning. Whereas Pavlov and most of his contemporaries saw classical conditioning as learning that comes from exposing an organism to associations of environmental events, modern classical conditioning theorists, like R. A. Rescorla, prefer to define it in more specific terms. Rescorla emphasizes the fact that contiguity or a temporal relationship between the unconditioned stimulus and the conditioned stimulus is not enough for Pavlovian conditioning to occur. Instead, the conditioned stimulus must relate some information about the unconditioned stimulus (Rescorla, 1988, pp. 151-153). The importance of this distinction can be seen in the experimental work done by Kamin (1969) and his blocking effect. In his experiment, rats were exposed to a tone followed by a shock. Following Pavlovian conditioning principles, the tone became a conditioned response. Yet, when the same rats were exposed to a tone and a light followed by a shock, no conditioning occurred with the light. This was because the tone had already related the information of the shock's arrival. So, any information the light would have given would have been useless. Even though the light was associated temporally with the shock, there was no conditioning because there was no information related (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, p. 53). Operant Conditioning Thorndike's law of effect. Although evidence of classical conditioning was there, E. L. Thorndike did not believe that it was comprehensive because most behavior in the natural environment was not simple enough to be explained by Pavlov's theory. He conducted an experiment where he put a cat in a cage with a latch on the door and a piece of salmon outside of the cage. After first trying to reach through the cage and then scratching at the bars of the cage, the cat finally hit the latch on the door and the door opened. With the repetition of this experiment, the amount of time and effort spent on the futile activities of reaching and scratching by the cats became less and the releasing of the latch occurred sooner. Thorndike's analysis of this behavior was that the behavior that produced the desired effect became dominant and therefore, occurred faster in the next experiments. He argued that more complicated behavior was influenced by anticipated results, not by a triggering stimulus as Pavlov had supposed. This idea became known as the law of effect, and it provided the basis for Skinner's operant conditioning analysis of behavior (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, pp. 24-26). Skinner's positive and negative reinforcement. Although Thorndike developed the basic law of effect, Skinner took this law and constructed a research program around it. He based this program on the experiments he had conducted in his study of punishment and reward. According to Skinner, the behavior caused by the law of effect was called operant conditioning because the behavior of an organism changed or operated on the environment. There were no real environmental stimuli forcing a response from an organism as in classical conditioning. Operant conditioning consists of two important elements, the operant or response and the consequence. If the consequence is favorable or positively reinforcing, then the likelihood of another similar response is more than if the consequence is punishing (Mischel, 1993, pp. 304-308). For instance, in Skinner's experiment a rat was put into a box with a lever. Each time the lever was depressed, food was released. As a result, the rat learned to press the lever to receive favorable consequences. However, when the food was replaced with shocks, the lever depressing stopped almost immediately due to punishing consequences. Similar results were produced by stopping the positive reinforcement of food altogether in a process called extinction, but the operant conditioned response decreased at a much slower rate than when punishment was used. This kind of operant conditioning occurs in the rewarding or punishing discipline action taken towards a child (Schwartz, 1982, pp. 27-53). Discriminative stimuli. The effect stimuli have on an operant response is different than in Pavlovian conditioning because the stimuli do not cause the response. They simply guide the response towards a positive or negative consequence. These operant response stimuli are called discriminative stimuli because they discriminate between the good and the bad consequences and indicate what response will be the most fruitful. For instance, a red stoplight indicates that one should step on the brakes. Although there is nothing that naturally forces humans to stop at a red light, they do stop. This is because the red indicates that if they do not, negative consequences will follow (Schwartz & Lacey, 1982, pp. 30-31). Avoidance theory. Although it is not always the case with discriminative stimuli, the red stop light stimuli and the appropriate stop response are also an example of the behavior known as avoidance-escape behavior. Put simply, the stimulus indicates that a negative consequence will follow if an action is not carried out, so the action is carried out. This may seem confusing given that extinction occurs in the sudden absence of any positive reinforcement. However, as shown in the experiments done by Rescorla and Solomon (1967), this is not the case. An animal was placed on one side of a partitioned box and trained to jump over the partition to avoid a shock. When the shock was removed, the animal retained its conditioned jumping behavior. Apparently in avoidant behavior, the escape or absence of reinforcement occurs because of a response. The animals in the box learned to expect shock if they did not respond or no shock if they did. Thus, the extinction occurred because they continued to respond to supposedly eliminate the shock (Schwartz & Lacey, 1982, 87-90). Schedules of reinforcement. Another exception to the extinction rule is an operant conditioned response that has been conditioned by intermittent schedules of reinforcement. There are four types of intermittent schedules: fixed interval schedules that reinforce a response after a certain fixed amount of time, variable interval schedules that reinforce a response after an amount of time that varies from reinforcement to reinforcement, fixed ratio schedules that reinforce a response after a certain fixed number of responses have been made, and varied ratio schedules that reinforce a response after varied numbers of responses are made. As strange as it may seem, maintenance of behavior is actually increased on these intermittent schedules as opposed to continuously reinforced behavior. This is due to the fact that with these occasional reinforcement patterns, the extinction of reinforcement takes a long time to recognize. As soon as it is recognized though, another reinforcement occurs and the extinction of the reinforcement now takes even longer to recognize. Thus, intermittent schedules keep the organism "guessing" as to when the reinforcement will occur and will reinforce the behavior without the actual reinforcement taking place (Schwartz & Lacey, 1982, pp. 91-101). Natural selection by consequences. In an attempt to convince his critics of the validity of his theory of operant conditioning, Skinner drew some interesting parallels between his theory and Darwin's theory of natural selection. According to Skinner, operant conditioning is nothing more than "a second kind of selection by consequences" (Skinner, 1984b, p. 477). He pointed out that although natural selection was necessary for the survival of the species, operant conditioning was necessary for an individual to learn. Also, evolutionary advances occurred because species with these advantages were more efficient in passing on the advantage, and operant conditioning occurs because certain reinforcements have affected the individual in a more efficient manner. Skinner goes on to draw the parallel between the evolution of living beings from molecules without the concept of life and the initiation of operant behavior from the environment without the concept of an independent mind. Finally, Skinner mentions how species adapt to the environment in the same way an individual adapts to a situation. By comparing these two theories, Skinner hoped to show that like the theory of natural selection, his contemporaries should accept the theory of operant behavior (Skinner, 1984b, pp. 477-481). The Validity of Behaviorism Criticisms of the Behaviorist Theory Contradictions with the ideas of Darwin's natural selection. Whereas Darwin's theory has been widely accepted by most scientists, behaviorism is constantly coming under fire from critics. Indeed, this is why Skinner chooses to align his theory with Darwin's, to give credibility to his own. However, as B. Dahlbom (1984) points out, some ideas in Darwinism contradict Skinner's operant conditioning. Darwin believes humans are constantly improving themselves to gain better self-control. Yet, "to increase self-control means to increase liberty" or fee-will, something Skinner's very theory denies exists (Dahlbom, 1984, p. 486). Thus, the very base on which Skinner has formed his theory is a direct contradiction of Darwin's ideas (Dahlbom, 1984, pp. 484-486). At the same time, as W. Wyrwicka (1984) shows, Skinner compares the positive reinforcement drive inherent in operant conditioning with Darwin's proposal of the natural selection drive inherent in nature. According to Wyrwicka, the natural selection drive is dependent on what is necessary for the survival of the species, and "the consequences of operant behavior are not so much survival as sensory gratification" (Wyrwicka, 1984, p. 502). Given that what is most pleasurable to the senses is not always what is best for the survival of one's genes, often these two drives contradict each other. For example, smoking crack and participating in dangerous sports are two popular activities despite the hazards they pose to one's life. Obviously, Darwinism is more accepted than operant conditioning. By contradicting Darwin's ideas, Skinner's operant conditioning theory loses much of the support Skinner hoped to gain with his parallels (Wyrwicka, 1984, pp. 501-502). Failure to show adequate generalizability in human behavior. Although many experiments have been done showing evidence of both Pavlovian conditioning and operant conditioning, all of these experiments have been based on animals and their behavior. K. Boulding (1984) questions Skinner's application of principles of animal behavior to the much more complex human behavior. In using animals as substitutes for humans in the exploration of human behavior, Skinner is making the big assumption that general laws relating to the behavior of animals can be applied to describe the complex relations in the human world. If this assumption proves false, then the entire foundation upon which behaviorism rests will come crashing down. More experiments with human participants must be done to prove the validity of this theory (Boulding, 1984 pp. 483-484). Inability to explain the development of human language. Although Skinner's ideas on operant conditioning are able to explain phobias and neurosis, they are sadly lacking in applicability to the more complex human behaviors of language and memory. The theory's inability to explain the language phenomenon has in fact drawn a large number of critics to dismiss the theory. Although Skinner has responded to the criticism, his arguments remain weak and relatively unproven. Whereas public objective stimuli act as operational stimuli for the verbal responses, private stimuli or concepts such as "I'm hungry" are harder to explain. According to Skinner, the acquisition of verbal responses for private stimuli can be explained in four ways. First, he claims that private stimuli and the community do not need a connection. As long as there are some sort of public stimuli that can be associated with the private stimuli, a child can learn. Also, the public can deduce the private stimuli through nonverbal signs, such as groaning and facial expressions. However this association of public and private events can often be misinterpreted. His third theory that certain public and private stimuli are identical gives a very short list of identical stimuli, and his final theory that private stimuli can be generalized to public stimuli with coinciding characteristics gives very inaccurate results (Skinner, 1984a, pp. 511-517). M. E. P. Seligman offers an interesting alternative to Skinner's weak explanation of language. He explains that although operational and classical conditioning are important, there is a third principle involved in determining the behavior of an organism. This is the genetic preparedness of an organism to associate certain stimuli or reinforcers to responses. An organism brings with it to an experiment certain equipment and tendencies decided by genetics, which cause certain conditioned stimuli and unconditioned stimuli to be more or less associable. Therefore, the organism is more or less prepared by evolution to relate the two stimuli. Seligman classifies these tendencies towards association into three categories: Prepared or easily able to associate two stimuli, unprepared or somewhat difficult to associate two stimuli , and contraprepared or unable to associate two stimuli. The problem with behaviorists, he argues, is that they have mainly concentrated their experiments on unprepared sets of stimuli such as lights and shock. They provide the small amount of input needed for the unprepared association to take place and then create laws that generalize unprepared behavior to all types behavior. Thus, although the behaviorist laws may hold true for the unprepared sets of stimuli tested in labs, they have trouble explaining behaviors that are prepared (Seligman, 1970, pp. 406-408). In order to prove his theory, Seligman gives an example of an experiment conducted by Rozin and Garcia (1971) in which rats were fed saccharine tasting water while bright light flashed and noise sounded. At the same time, the rats were treated with X-ray radiation to cause nausea and illness. When the rats became ill a few hours later, they acquired an aversion to saccharine tasting water but not to light or noise. According to Seligman (1970), evolution had prepared the rats to associate taste with illness, but had contraprepared the association between noise/light and illness (pp. 411-412). When Seligman's theory of preparedness is applied to the language problem, it gives a plausible solution. Language is simply composed of well-prepared stimuli that are easily able to create relationships between verbal words and ideas or objects. In fact, they are so easy that often there is extremely little input needed for the associations to be made. But if this theory is taken as the truth, which it cannot be without further research, then this implies that there is a genetic factor that along with the environment creates personality. This rejects the comprehensive behaviorism theory so espoused by Skinner and his collaborators (Seligman, 1970, pp. 416-417). Applications of a Valid Behaviorist Theory The evidence shown, particularly that of language, points to the failure of behaviorism as a comprehensive theory. However, there is nothing that denies behaviorism is valid when limited to certain areas of psychology. Given that numerous experiments have shown there is merit in the behaviorist theory, certain ideas of this theory can be used in the treatment of disorders. With the ideas of behaviorism, vast improvements can be made in the treatment of neurosis and phobias. Rather than focusing on the root of the problem like a traditional psychopathologist, a behaviorist could focus on eliminating the symptom by bringing classical and operant conditioning into play. By reinforcing the extinction of the symptom, the psychopathological illness of the patient could be eliminated (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, pp. 194-196). Vast improvements could also be made in the areas of treating alcoholism and nicotine addiction. Using Pavlovian principles, addiction occurs because of both the pleasurable physiological effects of nicotine and alcohol, unconditioned stimuli, and the taste of nicotine and alcohol, conditioned stimuli. When one stops ingesting the substance, as in traditional treatment procedures, it is extremely easy to become addicted again. After all, "simply not presenting a conditioned stimulus does not eliminate the relation between it and the unconditioned stimuli" (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, p. 197). With just one use, the taste and unconditioned pleasurable effects become associated with each other again. However, if the taste of nicotine or alcohol, the conditioned response, is paired with a new unpleasant effect such as nausea and vomiting, the result will be a negative aversion to the substances in question. Such was the case when both an old alcoholic man and a young chain smoking adolescent were given apomorphine paired with alcohol and nicotine, respectively. The drug apomorphine induced severe feelings of nausea and vomiting which caused both of them to give up these addictive substances for life. This process is called counterconditioning and has had remarkable success in curing addictions (Schwartz & Lacy, 1982, pp. 196-200). Conclusion: On the Theory of Behaviorism The criticisms posed by this paper have long plagued the theory of behaviorism and prevented it from being truly acceptable by most scientists. In fact, today there are very few scientists who believe that the behaviorist theory is as comprehensive as it was once thought to be. In spite of the holes in the theory, there can be no doubt as to the usefulness of the research done in the field of behaviorism. One cannot totally dismiss the effect the environment has on behavior nor the role it plays in developing personality as shown through this research. Indeed, when the theory of behaviorism is applied to combat certain disorders, the results have shown it to be remarkably effective. Therefore, although comprehensive behaviorism must be abandoned, its ideas cannot be ignored when applied to certain situations.

Peer Commentary Behaviorism: More Than a Failure to Follow in Darwin's Footsteps Alissa D. Eischens Northwestern University In "Behaviorism as a Theory of Personality: A Critical Look," Naik raises many valid arguments against the merits of behavioral theory as a theory of personality. On the whole, I am in agreement with Naik's rejection of behaviorism as a comprehensive theory. Like Naik, I believe that behaviorism's rejection of mental processes invalidate its ability to adequately explain human behavior and personality. By touching upon the problems behaviorism has in explaining language and memory, Naik makes a good argument against behaviorism's ability to account for the complexities of human behavior. I also agree wholeheartedly with Naik's proposal concerning the inadequacy of animal experiments' application to human behavior. I too feel that human behavior is too complex to be explained solely through animal models. Naik's criticism citing the Seligman (1970) article is valid in that behaviorism has largely tried to apply unprepared stimuli experiments to behavior in general. Naik also makes a good argument for the use of behavioral techniques in curing addiction. Although I reiterate that I am in agreement with Naik's general argument, I believe some of the article's arguments could be stronger. Using Skinner's desire to align himself with Darwin may not be invalid; however, just because Skinner fails to gain acceptance in Darwinesque fashion does not immediately render his theory invalid. Surely, Skinner probably hoped to gain the acceptance Darwin's theory has enjoyed in the scientific community. But even though his theory has not gained such widespread acceptance, I do not believe that Skinner tried to ride Darwin's proverbial coattails. Instead, Skinner's comparison to Darwin's theory should be seen more as illustrative rather than as a basis for proving the theory's worth. Skinner tries to pick up where Darwin left off; I do not think Skinner relied as heavily on the acceptance of Darwinian theory as Naik suggests. I also take exception to the argument Naik makes using the Wyrwicka (1984) article for support. Positive reinforcement is not solely concerned with sensory gratification. Positive reinforcement can play an important role in social relationships, and given that humans are social beings, successful relationships can be very important. Finally, I have trouble accepting behaviorism's effectiveness as a treatment for psychopathology. Perhaps if examples had been provided to elucidate this idea I would be more accepting. However, psychopathology by its very name implies the inner workings of the brain, something Naik has asserted that behaviorism denies. Therefore, I fail to see how behavioral techniques could cure psychopathological disorders. Perhaps people with these disorders could be conditioned to act contrary to their problems, but I do not believe conditioning would eliminate the roots of those problems. I believe that Naik has made a cogent argument against behaviorism as a comprehensive theory, with the exceptions I have noted. Rather than focusing on the Darwinian aspect of Skinner's theory, Naik would do well to go into further depth concerning behaviorism's denial of the mind and inability to explain language, where I believe the true roots of behaviorism's failure lie.

Peer Commentary Accepting an Invalid Theory and Flaws in the Flaws of Behaviorism Nathan C. Popkins Northwestern University Naik's assessment of behaviorism, in the broader sense, is both correct and logical. There are definite problems with the theory of behaviorism, with its infamous "black box" (which Naik addresses indirectly in her discussion on the failure of behaviorism to explain the development of language), and the attempts by behaviorists to extrapolate animal behavior to humans. However, Naik also devotes a lengthy section of her paper to the applications of what she calls a "valid" behaviorist theory. Naik's explanation of the failure of behaviorism to explain the development of human language (not the broader "black box," but specifically the development of language) cites a potentially flawed argument that is easiest to refute by counterexample. The sections of Naik's paper on the flaws of behaviorism and on the applications of a valid behaviorist theory betray her conclusion. Naik's conclusion is that behaviorism is an invalid theory in personality because of the flaws inherent in behaviorist theory. The correlation between Naik's criticisms of behaviorism and her conclusion is obvious: Behaviorism is not a "great" or valid theory in personality. This is a logical conclusion given the cited flaws in the theory. The problem in the logic of Naik's paper stems from her description of the applications of behaviorism. According to Naik, these applications validate behaviorism. Naik cites examples of the applications of behaviorism. These are not theoretical uses for behaviorist theory, but applications that are proven effective and are currently in use. Naik claims that although behaviorism fails to meet the criteria of greatness in the broad sense, behaviorism can still be valid in certain situations. Essentially, this is like claiming that behaviorism is not a great theory, except for the times that it is a great theory. The second major shortcoming in Naik's paper (though no fault of her own) is the citation of a common argument against behaviorism that involves the failure of behaviorism to describe the development of language. This does not refer to the process of an infant learning to talk (as behaviorism is actually a very convenient way of describing this process) but rather the original development of language in the human race. This argument is basically based on the concept that the very first humans to attempt to develop a language (this was, in all likelihood, not an active attempt, but rather something that just sort of happened) had no previous examples on which to base their actions and speech. In other words, they had no behavior after which to pattern their own. In this argument, however, counterexample can be used to show that, to an extent, this is untrue. Naik's example of the phrase, "I'm hungry," is very useful for illustrating this phenomenon of the development of language. Imagine, before language had developed, a group of early humans are about to eat. One of these humans makes a noise, then begins to eat. The original noise is of no consequence whatsoever. However, this random action has established a precedent. According to behaviorism, a repetition of this noise by the other humans before eating would make sense. It is only logical to assume that this noise, after several iterations, would just naturally come to mean, "I'm hungry," or, "Let's eat." Through this behavioristic process, it is not difficult to imagine how language would proceed to develop. Naik cites the major accepted flaws in behaviorism. If these are relevant, her conclusion that behaviorism is not a valid theory in personality is correct. However, she also needs to look for another possible explanation for what she calls applications of a valid behaviorist theory.

Peer Commentary Behaviorism: A More Inclusive Approach Timothy Tasker Northwestern University In "Behaviorism as a Theory of Personality: A Critical Look," Naik takes a close look at the field of personality known as behaviorism. This is accomplished in an effective manner with a substantial base of support. However, more importantly, Naik's portrayal of behaviorism lacks some key concepts that I shall discuss later in this review. First, let us start with the strong points this author puts forth. Contrary to popular belief, behaviorism was not developed by Pavlov, but by Descartes much earlier in France. This factual information concerning the origin of behaviorism has been reflected effectively in the paper by Naik. The ideas put forth are quite solid and one is hard pressed to argue with the evidence cited or the arguments made. I feel that the acceptance of the limitations of behaviorism is of great credit to the author. Naik does not blindly support behaviorism, but can find the limitatons inherent here and finds that parts of this theory are more applicable than ideas contained in this theory. What I find most convincing is the choice of theorists that have been cited. Naik chose to reflect the vast number of ideas and amount of research contained in the theory of behaviorism by citing a varied group of authors. All of these have their own separate ideas as to what is important to behaviorism, and their contributions to the theory as it stands today are effectively noted. As a result of writing the paper in a chronological sequence, Naik has given us an evolution of behaviorism. The ideas submitted by one researcher are built upon well in the next section by citing the work of another. What we end up with is a structure that, however unstable the materials with which it was built, was built up pragmatically. The problems that are intrinsic here are more a result of this theory's inability to withstand the criticisms others have put forth. The faults for which I do hold Naik accountable are the lack of inclusive information that has been well documented throughout the development of the theory of behaviorism. There is a blatant neglect of the ideas of generalization, discrimination, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. The idea of generalization was touched upon in this article, but not paid the full respects that it deserves. Naik noted the famous experiment of baby Albert and his eventual aversion to all furry objects/animals. This can be fully explined by generalization. When an organism is presented with a stimulus that will cause some degree of a response, the response will be found, under certain conditions, to be "generalized" for other similar stimuli. In other words, when baby Albert eventully developed an aversion for all furry objects, specifically a cat, the principle that explains his aversion to the cat is generalization. Although Naik discussed its existence, I believe that it is necessary to name and further evaluate this principle that behaviorists deem so important. Discrimination is another important factor that I believe has been dealt with in an incorrect manner by this article. Discrimination is essentially the idea that opposes generalization. It can be seen when an organism will respond to a certain stimulus, but fails to produce the same response when presented with a similar stimulus. A good example of this that could have been suggested is a pet that at first may respond to all noises, then learns to respond only to the human voice, and will then respond solely to the voice of its owner. For humans, discrimination is key for our survival. We need to constantly screen out stimuli and discriminate between like stimuli for us to be effective and survive. The last factor of this theory that I feel has been unattended to is the principle of extinction. When Naik discusses the varying schedules of reinforcement, she hints at the existence of the extinction principle. Extinction is the idea that organisms will show a rapid decrease in their response to a stimulus if the response is not rewarded or is rewarded less frequently than when introduced. According to this idea an organism will eventually lose or "forget" its response to a conditioned stimulus if the reinforcement is not provided. The exception to the extinction principle can be seen in spontaneous recovery. When the organism is not presented with the conditioned stimulus for quite some time and then the stimulus is suddenly presented, the organism will generally respond accordingly. In Naik's article this idea is nowhere to be found. I find fault with the article overall for its non-inclusiveness.

Author Response Concepts Need Clarification, Not Renovation Payal Naik Northwestern University I would like to thank the peer commentators for their valuable suggestions and critiques. A perfect paper is an extremely rare thing, and if anything, the words of my reviewers have shown me that my paper has plenty of flaws. Yet, at the same time, I feel that these flaws are not due to problems with the content or ideology of my paper but rather a lack of clarification or explanation of my ideas. Thus, taking into account the suggestions of my peers, I will attempt to clarify what my paper is saying. In her commentary, Eischens explains Skinner's comparison of Darwin's natural selection and his own selection by consequences as illustrative and not a fundamental part of his theory. Yet, by mentioning his comparison in my paper, I was not attempting to show this comparison to be a fundamental part of the theory, but rather to point out that there are contradictions between the two theories. These contradictions hinder the acceptability of behaviorism because Darwinism has already been accepted as fact and any contradictions are therefore false. By bringing Darwinism and behaviorism together, Skinner is simply making the contradiction obvious. Also, Eischens states that psychopathology "by its very name implies the inner workings of the brain" and thus cannot be treated with a behaviorist approach. This is a very good point and I must confess that as it stands in my paper, it is a major flaw. Instead of claiming behaviorism can treat psychopathological problems, I should assert that behaviorism can treat symptoms that have been associated with psychopathological problems in the past. After all, behaviorists only want to eliminate the problem and do not care about discovering the source. On the other hand, Popkins seems to argue in favor of behaviorism and its uses. He states that by showing the success in the application of behaviorism, I am proving the validity of behaviorism. Yet, although I agree that these applications prove that behaviorism is sometimes valid in our present world, a comprehensive behavioristic theory has not been validated. In effect, I am saying that comprehensive behaviorism is not a great theory because it fails to answer some key concepts. One of these concepts is language. Popkins also feels that behaviorism can account for the development of language. I am not saying that it does not account for the development of language but rather that it does not account for the easy conditioning of language. However, if behaviorism is combined with a theory on genetic preparedness, these key concepts are answered and the applications still hold true. Tasker focuses on the lack of an explanation of certain concepts included in the theory of behaviorism. These include generalization, discrimination, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. I can only say that I did in fact include generalization, discrimination, and extinction. Although I agree that I make these explanations brief, these concepts are not essential to my argument. Thus, the compact ideas have no real consequence on the paper. If I included the full explanations for them, I would just be adding unnecessary details, and the majority of the paper would be devoted to the explanation of the theory and not the criticism. Once again, I would like to reiterate that the suggestions of the peer commentators are greatly appreciated. Their criticisms have pinpointed some of the weaknesses in my paper. However, whereas they have stated that these flaws stem from the content of the paper, I believe that the problem is in lack of clarification and proper communication of my ideas. Nevertheless, I still stand by the validity of my paper and the concepts and criticism it contains.

References Beecroft, R. S. (1966). Method in classical conditioning. In R. S. Beecroft, Classical conditioning (pp. 8-26). Goleta, CA: Psychonomic Press. Boulding, K. E. (1984). B. F. Skinner: A dissident view. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7, 483-484. Dahlbom, B. (1984). Skinner, selection, and self-control. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7, 484-486. Kamin, L. J. (1969). Predictability, surprise, attention and conditioning. In B. A. Campbell & R. M. Church (Eds.), Punishment and aversive behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Mischel, W. (1993). Behavioral conceptions. In W. Mischel, Introduction to personality (pp. 295-316). New York: Harcourt Brace. Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovlian conditioning: It's not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43, 151-160. Rescorla, R. A., & Solomon, R. L. (1967). Two-process learning theory: Relations between Pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychological Review, 74, 151-182. Rozin, P., & Garcia, J. (1971). Specific hungers and poison avoidance as adaptive specializations of learning. Psychological Review, 78, 459-486. Schwartz, B., & Lacey, H. (1982). Behaviorism, science, and human nature. New York: Norton. Seligman, M. E. P. (1970). On the generality of the laws of learning. Psychological Review, 77, 406-418. Skinner, B. F. (1931). The concept of the reflex in the description of behavior. Journal of General Psychology, 5, 427-458. Skinner, B. F. (1984a). Operational analysis of psychological terms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7, 511-517. Skinner, B. F. (1984b). Selection by consequences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7, 477-481. Wyrwicka, W. (1984). Natural selection and operant behavior. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7, 501-502.

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Groundwork

- 1.1. Research

- 1.2. Knowing

- 1.3. Theories

- 1.4. Ethics

- 2. Paradigms

- 2.1. Inferential Statistics

- 2.2. Sampling

- 2.3. Qualitative Rigor

- 2.4. Design-Based Research

- 2.5. Mixed Methods

- 3. Learning Theories

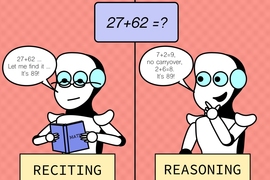

- 3.1. Behaviorism

- 3.2. Cognitivism

- 3.3. Constructivism

- 3.4. Socioculturalism

- 3.5. Connectivism

- Appendix A. Supplements

- Appendix B. Example Studies

- Example Study #1. Public comment sentiment on educational videos

- Example Study #2. Effects of open textbook adoption on teachers' open practices

- Appendix C. Historical Readings

- Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848)

- On the Origin of Species (1859)

- Science and the Savages (1905)

- Theories of Knowledge (1916)

- Theories of Morals (1916)

- Translations

Behaviorism

Choose a sign-in option.

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Behaviorism is an area of psychological study that focuses on observing and analyzing how controlled environmental changes affect behavior. The goal of behavioristic teaching methods is to manipulate the environment of a subject — a human or an animal — in an effort to change the subject’s observable behavior. From a behaviorist perspective, learning is defined entirely by this change in the subject’s observable behavior. The role of the subject in the learning process is to be acted upon by the environment; the subject forms associations between stimuli and changes behavior based on those associations. The role of the teacher is to manipulate the environment in an effort to encourage the desired behavioral changes. The principles of behaviorism were not formed overnight but evolved over time from the work of multiple psychologists. As psychologists’ understanding of learning has evolved over time, some principles of behaviorism have been discarded or replaced, while others continue to be accepted and practiced.

History of Behaviorism

A basic understanding of behaviorism can be gained by examining the history of four of the most influential psychologists who contributed to the behaviorism: Ivan Pavlov, Edward Thorndike, John B. Watson, and B.F. Skinner. These four did not each develop principles of behaviorism in isolation, but rather built upon each other’s work.

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov is perhaps most well-known for his work in conditioning dogs to salivate at the sound of a tone after pairing food with the sound over time. Pavlov’s research is regarded as the first to explore the theory of classical conditioning: that stimuli cause responses and that the brain can associate stimuli together to learn new responses. His research also studied how certain parameters — such as the time between two stimuli being presented — affected these associations in the brain. His exploration of the stimulus-response model, the associations formed in the brain, and the effects of certain parameters on developing new behaviors became a foundation of future experiments in the study of human and animal behavior (Hauser, 1997).

In his most famous experiment, Pavlov started out studying how much saliva different breeds of dogs produced for digestion. However, he soon noticed that the dogs would start salivating even before the food was provided. Subsequently he realized that the dogs associated the sound of him walking down the stairs with the arrival of food. He went on to test this theory by playing a tone when feeding the dogs, and over time the dogs learned to salivate at the sound of a tone even if there was no food present. The dogs learned a new response to a familiar stimulus via stimulus association. Pavlov called this learned response a conditional reflex. Pavlov performed several variations of this experiment, looking at how far apart he could play the tone before the dogs no longer associated the sound with food; or if applying randomization — playing the tone sometimes when feeding the dogs but not others — had any effect on the end results (Pavlov, 1927).

Pavlov’s work with conditional reflexes was extremely influential in the field of behaviorism. His experiments demonstrate three major tenets of the field of behaviorism:

- Behavior is learned from the environment. The dogs learned to salivate at the sound of a tone after their environment presented the tone along with food multiple times.

- Behavior must be observable. Pavlov concluded that learning was taking place because he observed the dogs salivating in response to the sound of a tone.

- All behaviors are a product of the formula stimulus-response. The sound of a tone caused no response until it was associated with the presentation of food, to which the dogs naturally responded with increased saliva production.

These principles formed a foundation of behaviorism on which future scientists would build.

Edward Thorndike

Edward Lee Thorndike is regarded as the first to study operant conditioning, or learning from consequences of behaviors. He demonstrated this principle by studying how long it took different animals to push a lever in order to receive food as a reward for solving a puzzle. He also pioneered the law of effect, which presents a theory about how behavior is learned and reinforced.

One experiment Thorndike conducted was called the puzzle box experiment, which is similar to the classic “rat in the maze” experiment. For this experiment, Thorndike placed a cat in a box with a piece of food on the outside of the box and timed how long it took the cat to push the lever to open the box and to get the food. The first two or three times each cat was placed in the box there was little difference in how long it took to open the box, but subsequent experiments showed a marked decrease in time as each cat learned that the same lever would consistently open the box.

A second major contribution Thorndike made to the field is his work in pioneering the law of effect. This law states that behavior followed by positive results is likely to be repeated and that any behavior with negative results will slowly cease over time. Thorndike’s puzzle box experiments supported this belief: animals were conditioned to frequently perform tasks that led to rewards.

Thorndike’s two major theories are the basis for much of the field of behaviorism and psychology studies of animals to this day. His results that animals can learn to press levers and buttons to receive food underpin many different types of animal studies exploring other behaviors and created the modern framework for the assumed similarities between animal responses and human responses (Engelhart, 1970).

In addition to his work with animals, Thorndike founded the field of educational psychology and wrote one of the first books on the subject, Educational Psychology, in 1903. Much of his later career was spent overhauling the field of teaching by applying his ideas about the law of effect and challenging former theories on generalized learning and punishment in the classroom. His theories and work have been taught in teaching colleges across the world.

John B. Watson

John Broadus Watson was a pioneering psychologist who is generally considered to be the first to combine the multiple facets of the field under the umbrella of behaviorism. The foundation of Watson’s behaviorism is that consciousness — introspective thoughts and feelings — can neither be observed nor controlled via scientific methods and therefore should be ignored when analyzing behavior. He asserted that psychology should be purely objective, focusing solely on predicting and controlling observable behavior, thus removing any interpretation of conscious experience. Thus, according to Watson, learning is a change in observable behavior. In his 1913 article “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It”, Watson defined behaviorism as “a purely objective experimental branch of natural science” that “recognizes no dividing line between man and brute.” The sole focus of Watson’s behaviorism is observing and predicting how subjects outwardly respond to external stimuli.

John Watson is remembered as the first psychologist to use human test subjects in experiments on classical conditioning. He is famous for the Little Albert experiment, in which he applied Pavlov’s ideas of classical conditioning to teach an infant to be afraid of a rat. Prior to the experiment, the nine-month-old infant Albert was exposed to several unfamiliar stimuli: a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, a monkey, masks with and without hair, cotton wool, burning newspapers, etc. He showed no fear in response. Through some further experimentation, researchers discovered that Albert responded with fear when they struck a steel bar with a hammer to produce a shap noise.

During the experiment, Albert was presented with the white rat that had previously produced no fear response. Whenever Albert touched the rat, the steel bar was struck, and Albert fell forward and began to whimper. Albert learned to become hesitant around the rat and was afraid to touch it. Eventually, the sight of the rat caused Albert to whimper and crawl away. Watson concluded that Albert had learned to be afraid of the rat (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

By today’s standards, the Little Albert experiment is considered both unethical and scientifically inconclusive. Critics have said that the experiment “reveals little evidence either that Albert developed a rat phobia or even that animals consistently evoked his fear (or anxiety) during Watson’s experiment” (Harris, 1997). However, the experiment provides insight into Watson’s definition of behaviorism — he taught Albert by controlling Albert’s environment, and the change in Albert’s behavior led researchers to conclude that learning had occurred.

B. F. Skinner

Skinner was a psychologist who continued to influence the development of behaviorism. His most important contributions were introducing the idea of radical behaviorism and defining operant conditioning.

Unlike Watson, Skinner believed that internal processes such as thoughts and emotions should be considered when analyzing behavior. The inclusion of thoughts and actions with behaviors is radical behaviorism. He believed that internal processes, like observable behavior, can be controlled by environmental variables and thus can be analyzed scientifically. The application of the principles of radical behaviorism is known as applied behavior analysis.

In 1938, Skinner published The Behavior of Organisms, a book that introduces the principles of operant conditioning and their application to human and animal behavior. The core concept of operant conditioning is the relationship between reinforcement and punishment, similar to Thorndike’s law of effect: Rewarded behaviors are more likely to be repeated, while punished behaviors are less likely to be repeated. Skinner expounded on Thorndike’s law of effect by breaking down reinforcement and punishment into five discrete categories (cf. Fig. 1):

- Positive reinforcement is adding a positive stimulus to encourage behavior.

- Escape is removing a negative stimulus to encourage behavior.

- Active avoidance is preventing a negative stimulus to encourage behavior.

- Positive punishment is adding a negative stimulus to discourage behavior.

- Negative punishment is removing a positive stimulus to discourage behavior.

Reinforcement encourages behavior, while punishment discourages behavior. Those who use operant conditioning use reinforcement and punishment in an effort to modify the subject’s behavior.

Figure 1. An overview of the five categories of operant conditioning.

Positive and negative reinforcements can be given according to different types of schedules. Skinner developed five schedules of reinforcement:

- Continuous reinforcement is applied when the learner receives reinforcement after every specific action performed. For example, a teacher may reward a student with a sticker for each meaningful comment the student makes.

- Fixed interval reinforcement is applied when the learner receives reinforcement after a fixed amount of time has passed. For example, a teacher may give out stickers each Friday to students who made comments throughout the week.

- Variable interval reinforcement is applied when the learner receives reinforcement after a random amount of time has passed. For example, a teacher may give out stickers on a random day each week to students who have actively participated in classroom discussion.

- Fixed ratio reinforcement is applied when the learner receives reinforcement after the behavior occurs a set number of times. For example, a teacher may reward a student with a sticker after the student contributes five meaningful comments.

- Variable ratio reinforcement is applied when the learner receives reinforcement after the behavior occurs a random number of times. For example, a teacher may reward a student with a sticker after the student contributes three to ten meaningful comments.

Skinner experimented using different reinforcement schedules in order to analyze which schedules were most effective in various situations. In general, he found that ratio schedules are more resistant to extinction than interval schedules, and variable schedules are more resistant than fixed schedules, making the variable ratio reinforcement schedule the most effective.

Skinner was a strong supporter of education and influenced various principles on the manners of educating. He believed there were two reasons for education: to teach both verbal and nonverbal behavior and to interest students in continually acquiring more knowledge. Based on his concept of reinforcement, Skinner taught that students learn best when taught by positive reinforcement and that students should be engaged in the process, not simply passive listeners. He hypothesized that students who are taught via punishment learn only how to avoid punishment. Although Skinner’s doubtful view on punishment is important to the discipline in education, finding other ways to discipline are very difficult, so punishment is still a big part in the education system.

Skinner points out that teachers need to be better educated in teaching and learning strategies (Skinner, 1968). He addresses the main reasons why learning is not successful. This biggest reasons teachers fail to educate their students are because they are only teaching through showing and they are not reinforcing their students enough. Skinner gave examples of steps teachers should take to teach properly. A few of these steps include the following:

- Ensure the learner clearly understands the action or performance.

- Separate the task into small steps starting at simple and working up to complex.

- Let the learner perform each step, reinforcing correct actions.

- Regulate so that the learner is always successful until finally the goal is reached.

- Change to random reinforcement to maintain the learner’s performance (Skinner, 1968).

Criticisms and Limitations

While there are elements of behaviorism that are still accepted and practiced, there are criticisms and limitations of behaviorism. Principles of behaviorism can help us to understand how humans are affected by associated stimuli, rewards, and punishments, but behaviorism may oversimplify the complexity of human learning. Behaviorism assumes humans are like animals, ignores the internal cognitive processes that underlie behavior, and focuses solely on changes in observable behavior.

From a behaviorist perspective, the role of the learner is to be acted upon by the teacher-controlled environment. The teacher’s role is to manipulate the environment to shape behavior. Thus, the student is not an agent in the learning process, but rather an animal that instinctively reacts to the environment. The teacher provides input (stimuli) and expects predictable output (the desired change in behavior). More recent learning theories, such as constructivism, focus much more on the role of the student in actively constructing knowledge.

Behaviorism also ignores internal cognitive processes, such as thoughts and feelings. Skinner’s radical behaviorism takes some of these processes into account insofar as they can be measured but does not really try to understand or explain the depth of human emotion. Without the desire to understand the reason behind the behavior, the behavior is not understood in a deeper context and reduces learning to the stimulus-response model. The behavior is observed, but the underlying cognitive processes that cause the behavior are not understood. The thoughts, emotions, conscious state, social interactions, prior knowledge, past experiences, and moral code of the student are not taken into account. In reality, these elements are all variables that need to be accounted for if human behavior is to be predicted and understood accurately. Newer learning theories, such as cognitivism, focus more on the roles of emotion, social interaction, prior knowledge, and personal experience in the learning process.

Another limitation to behaviorism is that learning is only defined as a change in observable behavior. Behaviorism operates on the premise that knowledge is only valuable if it results in modified behavior. Many believe that the purpose of learning and education is much more than teaching everyone to conform to a specific set of behaviors. For instance, Foshay (1991) argues that “the one continuing purpose of education, since ancient times, has been to bring people to as full as realization as possible of what it is to be a human being” (p. 277). Behaviorism’s focus on behavior alone may not achieve the purpose of education, because humans are more than just their behavior.

Behaviorism is a study of how controlled changes to a subject’s environment affect the subject’s observable behavior. Teachers control the environment and use a system of rewards and punishments in an effort to encourage the desired behaviors in the subject. Learners are acted upon by their environment, forming associations between stimuli and changing behavior based on those associations.

There are principles of behaviorism that are still accepted and practiced today, such as the use of rewards and punishments to shape behavior. However, behaviorism may oversimplify the complexity of human learning; downplay the role of the student in the learning process; disregard emotion, thoughts, and inner processes; and view humans as being as simple as animals.

Engelhart, M. D. (1970). [Review of Measurement and evaluation in psychology and education]. Journal of Educational Measurement, 7(1), 53–55. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1433880

Foshay, A. W. (1991). The curriculum matrix: Transcendence and mathematics. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 6(4), 277-293. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/journals/jcs/jcs_1991summer_foshay.pdf

Harris, B. (1979). Whatever happened to Little Albert? American Psychologist, 34(2), 151-160. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/8144115/Whatever_happened_to_Little_Albert

Hauser, L. (1997). Behaviorism. In J. Fieser & D. Bradley (Eds.), Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/behavior/

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex (G. V. Anrep, Trans.). London, England: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms. New York, NY: Appleton-Century. Retrieved from http://s-f-walker.org.uk/pubsebooks/pdfs/The%20Behavior%20of%20Organisms%20-%20BF%20Skinner.pdf

Skinner, B. F. (1968). The technology of teaching. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Thorndike/Animal/chap5.htm

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20(2), 158-177. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/views.htm

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1-14. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm

This content is provided to you freely by EdTech Books.

Access it online or download it at https://edtechbooks.org/education_research/behaviorismt .

BEHAVIOURISM: ITS IMPLICATION TO EDUCATION

- December 2019

- Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Christine Souribio

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.37(1); 2014 May

Did John B. Watson Really “Found” Behaviorism?

John c. malone.

Department of Psychology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996-0900 USA

Developments culminating in the nineteenth century, along with the predictable collapse of introspective psychology, meant that the rise of behavioral psychology was inevitable. In 1913, John B. Watson was an established scientist with impeccable credentials who acted as a strong and combative promoter of a natural science approach to psychology when just such an advocate was needed. He never claimed to have founded “behavior psychology” and, despite the acclaim and criticism attending his portrayal as the original behaviorist, he was more an exemplar of a movement than a founder. Many influential writers had already characterized psychology, including so-called mental activity, as behavior, offered many applications, and rejected metaphysical dualism. Among others, William Carpenter, Alexander Bain, and (early) Sigmund Freud held views compatible with twentieth-century behaviorism. Thus, though Watson was the first to argue specifically for psychology as a natural science, behaviorism in both theory and practice had clear roots long before 1913. If behaviorism really needs a “founder,” Edward Thorndike might seem more deserving, because of his great influence and promotion of an objective psychology, but he was not a true behaviorist for several important reasons. Watson deserves the fame he has received, since he first made a strong case for a natural science (behaviorist) approach and, importantly, he made people pay attention to it.

John B. Watson’s Contribution: Was Behaviorism Really “Founded”?

The origin of behaviorism has long been linked to John B. Watson, about whom much has been written and many talks given, especially during 2013, the centennial of his well-known Columbia lecture, “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It.” I want to commemorate that event and argue that Watson provided an important impetus to behaviorism, but that many others had prepared the way. Todd’s ( 1994 ) report suggests that recent textbook presentations lead the reader to assume that Watson actually created behaviorism and one might further conclude that his absence would have meant that psychology during the rest of the twentieth century would have been far different. In fact, Watson might well have taken a different path in life. For example, he could have gone into medicine and devoted his energies to the study of endocrinology or otorhinolaryngology. What if Watson had gone to medical school after graduating with a master’s degree from Furman University at the age of 21? In 1916, he hinted that it had been a possibility, perhaps later regretted, when he gave an example of a “Freudian slip” in an article praising Freud’s findings and therapy:

Only a moment ago it was necessary for me to call a man on the telephone. I said: "This is Dr. John B. Watson, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital," instead of Johns Hopkins University. One skilled in analysis could easily read in this slight slip the wish that I had gone into medicine instead of into psychology (even this analysis, though, would be far from complete). (p. 479)

Many decades later, his son, James, testified that his dad was embarrassed because he lacked a medical degree (Hannush 1987 , p. 146), while Watson himself wrote, “I think the only fly in the ointment was my inability, for financial reasons, to finish with my medical education” ( 1936 , p. 275). He wrote as if he would have continued on the behavioral course that he had taken and that a medical degree would have enabled him to work with medical people and avoid some of the “insolence of some of the youthful and inferior members of the profession” ( 1936 , p. 275). Skinner ( 1959 ) also supposed that Watson would have become a psychologist in any event. But in the 1916 quotation, Watson did write, “medicine instead of psychology,” suggesting that he might have drastically changed the course of his life and his work. That could have meant no 1913 epochal lecture and a different future for psychology. Or would John B. Watson’s absence from twentieth-century psychology really have made a difference? Did he really “found” behaviorism or would history have played out essentially as it did?

Why Is John B. Watson Considered the Founder of Behaviorism?

Given the many past and present tributes to John B. Watson, we might fairly ask why he is uniquely revered as the father of behavior analysis. He was so honored at the 2013 conference of the Association of Behavior Analysis International, but why was that? Why, for example, was Edward Thorndike not the honoree? Watson’s real academic career as a psychologist dealing with human behavior lasted only 12 years, from 1908 to 1920, coinciding with his time at Johns Hopkins University. He gave talks and wrote popular books and articles after that, but his autobiography in 1936 pretty much ended his scholarly career, although he did continue to contribute to current practices in business: marketing, management, and (maybe) advertising (Coon 1994 ; DiClemente and Hantula 2000 , 2003 ). But he clearly viewed that as business, and Watson said that being in business was very different from having an academic job (Buckley 1989 , p. 177).

As for behavioral research with humans, though he published little other than the “Little Albert” study that Todd ( 1994 , p. 102) contends has become the “baby-frightening experiment,” that serves mainly as introductory textbook lore. We might also count some data on “handedness” included informally in Behaviorism (Watson 1930 , pp. 131–133), as well as similar brief data presentations on other topics appearing here and there in his other reports (e.g., his 1920 work with Karl Lashley on venereal disease education). Mary Cover Jones ( 1924 ) did publish results of her work carried out under his direction but, like “Albert’s” data, that also dealt with acquired fears in children, this time their removal. Altogether, that seems an unimpressive record of research involving humans and certainly one reason that the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis shows almost no references to Watson! We might ask again, “Why is Watson celebrated as the founder of behaviorism?”

The answer may be simple. Watson was an attractive, strong, scientifically accomplished, and forceful speaker and an engaging writer at a time when anyone who could be called a proto-behaviorist was anxious to get along with the few other psychologists in the world. So such people, like Knight Dunlap (e.g., 1912 ), seemed weak, tentative, mealy mouthed, and ineffectual. On the other hand, Watson was articulate and combative, a real fighter who publicly dismissed the accumulated psychology of his time as rubbish. And he was a full professor at Johns Hopkins University at the age of 29, editor of Psychological Review , and the object of universal scholarly respect, if not adoration (e.g., Jastrow 1929 ). 1 Further, Watson had a message that seemed easy to understand, and that called for action , rather than quiet discussion and polite debate.

Not many paid attention in 1913 and for several years thereafter (Samelson 1994 ), but as 1920 approached, behaviorism was taking hold, partly because authoritative people like future Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell 2 and Harvard neorealist philosopher Ralph Barton Perry generally supported Watson’s program. Others, like Walter Hunter at Brown, welcomed Watson’s revolution and tried to explain behaviorism to many uncomprehending readers (Hunter 1922 ). A few years later, Woodworth referred to “the outbreak of behaviorism in 1912–14” ( 1931 , p. 45) and described it as a “youth movement” (p. 59). But he quoted the New York Times opinion, that Behaviorism “marks an epoch in the intellectual history of man,” as well as the Tribune , which hailed it “as the most important book ever written” ( 1931 , p. 92).

Watson the teacher directly inspired one future APA president who never took a traditional psychology course. Karl Lashley, who many consider the greatest neuropsychologist of our time, took a seminar with Watson and became a lifelong correspondent and ally. As Lashley put it in 1958, “Anyone who knows American psychology today knows that its value derives from biology and from Watson” (Beach 1961 , p. 171). Watson’s career has been discussed many times and it need not be repeated here. But what if the story of his promotion of behaviorism were only a dream—what if Watson had chosen a different career? Would behaviorism have never arisen?

Would Watson’s Absence Have Made a Real Difference?

If he had gone to medical school and followed a path not directly relevant to psychology, there would have been no 1913 behavioral “manifesto.” Would it follow that there would then be no Bertrand Russell’s ( 1921 ) report on Watson’s behaviorism for Skinner to read 3 and thus The Behavior of Organisms might never have been written? Perhaps applied behavior analysis would not exist and therapy would be wholly based on “Positive Psychology” or “Self-Actualization.” Worse, could the advertising industry possibly have shriveled to the point that we are merely informed of the virtues of products, rather than persuaded that we want them? 4 If this scenario seems plausible to us, then we do believe that Watson did possess the “superman-ic” power that Joseph Jastrow ( 1929 , p. 457) accused him of thinking that he had. But it is almost certain that such a scenario would not have occurred and that behaviorism would have emerged pretty much as it did. That is because Watson probably did not really alter history very much. He did what he wrote a nervous system does: It just “speeds up” the message, but the message still gets through without it ( 1930 , p. 50).

Watson Was an Exemplar, Not a Founder

Morris ( 2014 ) documented Watson’s contribution to modern applied behavior analysis in an interesting and thorough way. He relied on an article by Baer, Wolf, and Risley published in 1968, the first year of publication of The Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis , titled “Some Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis.” Those dimensions were “application,” “behavioral basis,” “analysis,” and several others, 5 each of which Morris showed to be compatible with Watson’s behaviorism as he presented it in 1913 and as he developed it later. This is not to say that Watson directly influenced applied behavior analysis, but his fundamental argument for a natural science approach influenced the neobehaviorisms, including those of Hull and Skinner, that followed and those eventually led to applied behavior analysis. But Watson’s was not the only voice arguing for an applied behavioral approach.

His work presaged both basic behavioral research and applied behavior analysis largely because his own views reflected those of his predecessors, some existing long before he was born. It is true that Watson was the strongest and most vocal possible advocate for applied behavioral methods and that he wrote “there was never a worse misnomer” than “practical” or “applied” psychology, since that is the only kind there is ( 1914 , p. 12). This despite the fact that actual examples of human application were absent from Behavior ( 1914 ) and pretty scarce in the rest of his writings, unless anecdotal illustrations count. No matter, because Watson was not alone and given the contributions of others, especially during the late nineteenth century, he was dispensable, serving not as an originator, but as a “crystallizer,” the label he used to describe himself (Burnham 1968 , p. 150; Watson 1919 , p. vii).

What Does it Mean to be a “Predecessor” of Behaviorism?

“Behaviorism” long ago lost whatever simple and specific definition it had. Watson coined the term in 1913, referred to “behavior psychology” in 1919 (p. viii), and titled his 1924 popular book Behaviorism . There are many adjectives that have been attached since, from “applied” to “cognitive” to “metaphysical” to “neo” to name only a few, so that “behavioral” is almost as vague a descriptor as is “cognitive.” These classificatory schemes are not relevant here, so I leave “behavioral” operationally defined in much the way that Watson used it. 6

By behaviorism, I mean the general philosophy and practice advocated by Watson after 1924, adopted by Skinner ( 1945 ), and often classified as “radical” behaviorism (Malone 2009 ; Moore 2008 ; Morris et al. 2013 ). As a philosophy, radical behaviorism is independent of any particular learning theory, so that habit, operant, respondent, reinforcement, and other terms specific to particular learning theories are irrelevant. What characteristics define such a behaviorist? First, such behaviorists do not explain behavior by means of (usually vacuous) underlying biological mechanisms as in, “The fMRI shows that impulse control depends on supraorbital frontal cortex suppressing limbic cortex.” 7 Such behaviorists also do not explain by means of trait names, as in “The ability to recall long sequences of numbers is due to exceptional memory.” Such intervening variables and hypothetical constructs are not acceptable because they merely name the activities to be explained. Real explanations depend on showing relations between past and present environments and behavior. Mathematical applications are often helpful, and descriptive vocabulary can include words like “habit,” as well as mental terms as long as they are recognized as verbs, like “seeing,” meaning that they are behavior. Given these simple criteria, which reduce to the single criterion of sticking to relations between environment and behavior, we need only add the proviso that the explanation can usefully be applied, if only in principle. For example, Herrnstein’s ( 1958 ) matching law has many applications, but decades passed after its introduction before this was widely recognized.

Given these criteria, a host of historical figures proposed what are clear behavior analytic applications, though we must forgive them for their failure to use modern jargon. As a single ancient example, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics provides specific advice on living one’s life and on raising one’s children, a pretty behavioral doctrine recently advocated by writers as different as J. R. Kantor (e.g., 1963 ), Ayn Rand ( 1982 ), and Howard Rachlin (e.g., 1994 ). For example, Aristotle stressed the importance of establishing habits in children and that doing so requires coercion, since a child is not initially affected by the consequences of virtuous action (i.e., natural consequences). Habit change always requires action, not just verbal commitments, and intelligence, honesty, ambition, and other trait names are meaningful only as patterns of action extended over time. Many readers would be surprised at just how behavioral Aristotle’s writings can be, especially evident in the Nicomachean Ethics (e.g., in Loomis, 1943 ). Watson may well have read it, given his years studying Greek at Furman.

Many other proto-applied behavior analytic figures could be mentioned, but I will comment on four who are salient and relatively recent. These are William Carpenter, Alexander Bain, Sigmund Freud (perhaps surprisingly), and especially, the relentless enemy of mentalism, Edward Thorndike. They and too many others to include provided more than enough behavioral impetus to inspire Skinner, and through him, the behavior analysts who followed, whether Watson had played a part or not. Consider the case for these relatively recent progenitors of behaviorism and for their specific contributions. First, consider the writings of William Carpenter and Alexander Bain, which appeared in many editions, were known to most educated people, and were very influential.

Nineteenth-Century Anticipations of Behavior Analysis

William carpenter’s mental physiology.