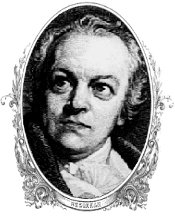

William Blake

(1757-1827)

Who Was William Blake?

William Blake began writing at an early age and claimed to have had his first vision, of a tree full of angels, at age 10. He studied engraving and grew to love Gothic art, which he incorporated into his own unique works. A misunderstood poet, artist and visionary throughout much of his life, Blake found admirers late in life and has been vastly influential since his death in 1827.

Early Years

William Blake was born on November 28, 1757, in the Soho district of London, England. He only briefly attended school, being chiefly educated at home by his mother. The Bible had an early, profound influence on Blake, and it would remain a lifetime source of inspiration, coloring his life and works with intense spirituality.

At an early age, Blake began experiencing visions, and his friend and journalist Henry Crabb Robinson wrote that Blake saw God's head appear in a window when Blake was 4 years old. He also allegedly saw the prophet Ezekiel under a tree and had a vision of "a tree filled with angels." Blake's visions would have a lasting effect on the art and writings that he produced.

The Young Artist

Blake's artistic ability became evident in his youth, and by age 10, he was enrolled at Henry Pars' drawing school, where he sketched the human figure by copying from plaster casts of ancient statues. At age 14, he apprenticed with an engraver. Blake's master was the engraver to the London Society of Antiquaries, and Blake was sent to Westminster Abbey to make drawings of tombs and monuments, where his lifelong love of gothic art was seeded.

The Maturing Artist

In 1779, at age 21, Blake completed his seven-year apprenticeship and became a journeyman copy engraver, working on projects for book and print publishers. Also preparing himself for a career as a painter, that same year, he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Art's Schools of Design, where he began exhibiting his own works in 1780. Blake's artistic energies branched out at this point, and he privately published his Poetical Sketches (1783), a collection of poems that he had written over the previous 14 years.

In August 1782, Blake married Catherine Sophia Boucher, who was illiterate. Blake taught her how to read, write, draw and color (his designs and prints). He also helped her to experience visions, as he did. Catherine believed explicitly in her husband's visions and his genius, and supported him in everything he did, right up to his death 45 years later.

One of the most traumatic events of Blake's life occurred in 1787, when his beloved brother, Robert, died from tuberculosis at age 24. At the moment of Robert's death, Blake allegedly saw his spirit ascend through the ceiling, joyously; the moment, which entered into Blake's psyche, greatly influenced his later poetry. The following year, Robert appeared to Blake in a vision and presented him with a new method of printing his works, which Blake called "illuminated printing." Once incorporated, this method allowed Blake to control every aspect of the production of his art.

While Blake was an established engraver, soon he began receiving commissions to paint watercolors, and he painted scenes from the works of Milton, Dante , Shakespeare and the Bible.

The Move to Felpham and Charges of Sedition

In 1800, Blake accepted an invitation from poet William Hayley to move to the little seaside village of Felpham and work as his protégé. While the relationship between Hayley and Blake began to sour, Blake ran into trouble of a different stripe: In August 1803, Blake found a soldier, John Schofield, on the property and demanded that he leave. After Schofield refused and an argument ensued, Blake removed him by force. Schofield accused Blake of assault and, worse, of sedition, claiming that he had damned the king.

The punishments for sedition in England at the time (during the Napoleonic Wars) were severe. Blake anguished, uncertain of his fate. Hayley hired a lawyer on Blake's behalf, and he was acquitted in January 1804, by which time Blake and Catherine had moved back to London.

Later Years

In 1804, Blake began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804-20), his most ambitious work to date. He also began showing more work at exhibitions (including Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims and Satan Calling Up His Legions ), but these works were met with silence, and the one published review was absurdly negative; the reviewer called the exhibit a display of "nonsense, unintelligibleness and egregious vanity," and referred to Blake as "an unfortunate lunatic."

Blake was devastated by the review and lack of attention to his works, and, subsequently, he withdrew more and more from any attempt at success. From 1809 to 1818, he engraved few plates (there is no record of Blake producing any commercial engravings from 1806 to 1813). He also sank deeper into poverty, obscurity and paranoia.

In 1819, however, Blake began sketching a series of "visionary heads," claiming that the historical and imaginary figures that he depicted actually appeared and sat for him. By 1825, Blake had sketched more than 100 of them, including those of Solomon and Merlin the magician and those included in "The Man Who Built the Pyramids" and "Harold Killed at the Battle of Hastings"; along with the most famous visionary head, that included in Blake's "The Ghost of a Flea."

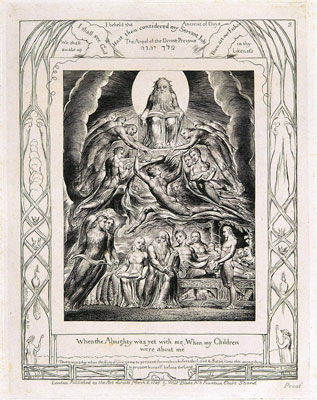

Remaining artistically busy, between 1823 and 1825, Blake engraved 21 designs for an illustrated Book of Job (from the Bible) and Dante's Inferno . In 1824, he began a series of 102 watercolor illustrations of Dante — a project that would be cut short by Blake's death in 1827.

Death and Legacy

In the final years of his life, Blake suffered from recurring bouts of an undiagnosed disease that he called "that sickness to which there is no name." He died on August 12, 1827, leaving unfinished watercolor illustrations to Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress and an illuminated manuscript of the Bible's Book of Genesis. In death, as in life, Blake received short shrift from observers, and obituaries tended to underscore his personal idiosyncrasies at the expense of his artistic accomplishments. The Literary Chronicle , for example, described him as "one of those ingenious persons ... whose eccentricities were still more remarkable than their professional abilities."

Unappreciated in life, Blake has since become a giant in literary and artistic circles, and his visionary approach to art and writing has not only spawned countless, spellbound speculations about Blake, they have inspired a vast array of artists and writers.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: William Blake

- Birth Year: 1757

- Birth date: November 28, 1757

- Birth City: London, England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: William Blake was a 19th-century writer and artist who is regarded as a seminal figure of the Romantic Age. His writings have influenced countless writers and artists through the ages.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Christianity

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Royal Academy of Art's Schools of Design

- Death Year: 1827

- Death date: August 12, 1827

- Death City: London, England

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: William Blake Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/william-blake

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 27, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- I am under the direction of messengers from Heaven daily and nightly.

- The vision of Christ that thou dost see is my vision's greatest enemy. Both read the Bible day and night, but thou readst black where I read white.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous British People

Stephen Hawking

Gordon Ramsay

Kiefer Sutherland

Amy Winehouse

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Biography Online

Biography William Blake

“Tyger, Tyger, burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”

– William Blake – The Tyger (from Songs of Experience )

Short Bio of William Blake

William Blake was born in London 28 November 1757, where he spent most of his life. His father was a successful London hosier and attracted by the Religious teachings of Emmanuel Swedenborg. Blake was first educated at home, chiefly by his mother. Blake remained very close to his mother and wrote a lot of poetry about her. Poems such as Cradle Song illustrate Blake’s fond memories for his upbringing by his mother:

Sweet dreams, form a shade O’er my lovely infant’s head; Sweet dreams of pleasant streams By happy, silent, moony beams. Sweet sleep, with soft down Weave thy brows an infant crown. Sweep sleep, Angel mild, Hover o’er my happy child.

– William Blake

His parents were broadly sympathetic with his artistic temperament and they encouraged him to collect Italian prints. He found work as an engraver, joining the trade at an early age. He found the early apprenticeship rather boring, but the skills he learnt proved useful throughout his artistic life. He became very skilled as an engraver and after completing his apprenticeship in 1779, he set up as an independent artist. He received many commissions and became well known as a skilled artist. Throughout his life, Blake was innovative and his willingness to depict the spirit world in physical form was criticised by elements of the press.

In 1791, Blake fell in love with Catherine Boucher, an illiterate and poor woman from Battersea across the Thames. The marriage proved a real meeting of mind and spirit. Blake taught his wife to read and write, and freely shared his inner and outer experiences. Catherine became a devoted wife and an uncompromising supporter of Blake’s artistic genius.

“Love seeketh not itself to please, Nor for itself hath any care, But for another gives its ease, And builds a heaven in hell’s despair.”

– Songs of Experience, The Clod and the Pebble, st. 1

Mystical experiences and poetry

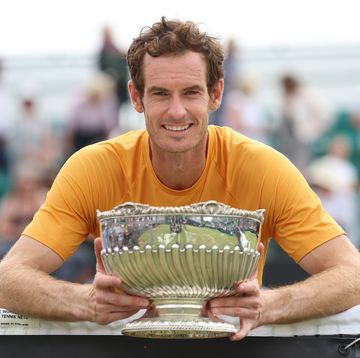

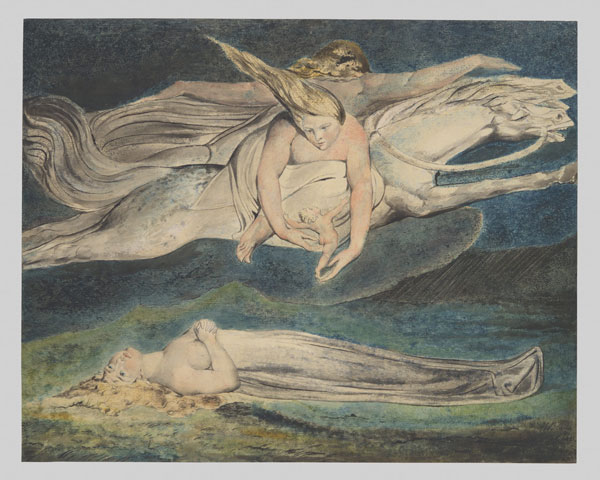

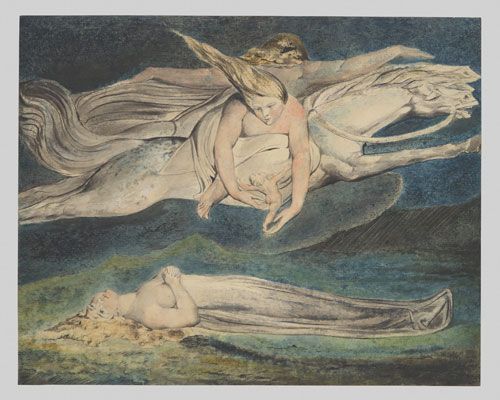

‘Pity’ by William Blake

As a young boy, Blake recalls having a most revealing vision of seeing angels in the trees. These mystical visions returned throughout his life, leaving a profound mark on his poetry and outlook.

“I am not ashamed, afraid, or averse to tell you what Ought to be Told: That I am under the direction of Messengers from Heaven, Daily & Nightly; but the nature of such things is not, as some suppose, without trouble or care.” – Letters of William Blake

William Blake was also particularly sensitive to cruelty. His heart wept at the sight of man’s inhumanity to other men and children. In many ways he was also of radical temperament, rebelling against the prevailing orthodoxy of the day. His anger and frustration at the world can be seen in his collection of poems “ Songs of Experience ”

“How can the bird that is born for joy Sit in a cage and sing? How can a child, when fears annoy, But droop his tender wing, And forget his youthful spring!”

– William Blake: The Schoolboy

As well as writing poetry that revealed and exposed the harsh realities of life, William Blake never lost touch with his heavenly visions. Like a true seer, he could see beyond the ordinary world and glimpse another possibility.

“To see a world in a grain of sand And heaven in a wild flower Hold infinity in the palm of your hand And eternity in an hour.”

This poem from Auguries of Innocence is one of the most loved poems in the English language. Within four short lines, he gives an impression of the infinite in the finite, and the eternal in the transient.

One of Blake’s greatest poems – popularly referred to as ‘Jerusalem’ – was the preface to his epic work “Milton: A poem in two books”. This hymn was inspired by the story that Jesus travelled to Glastonbury, England – in the years before his documented life in the Gospels. To Blake, Jerusalem was a metaphor for creating Heaven on earth and transforming all that is ugly about modern life ‘dark satanic mills’ into ‘England’s green and pleasant land.” Jerusalem, set to music by Hubert Parry in 1916, is often seen as England’s unofficial national anthem.

On one occasion he got into trouble with the authorities for forcing a soldier to leave his back garden. It was in the period of the Napoleonic Wars where the government were cracking down on any perceived lack of patriotism. In this climate, he was arrested for sedition and faced the possibility of jail. Blake defended himself and despite the prejudices of those who disliked Blake’s anti-military attitude, he was able to gain an acquittal.

Religion of Blake

Outwardly Blake was a member of the Church of England, where he was christened, married and buried. However, his faith and spiritual experience was much deeper and more unconventional than orthodox religion. He considered himself a sincere Christian but was frequently critical of organised religion.

“And now let me finish with assuring you that, Tho I have been very unhappy, I am so no longer. I am again. Emerged into the light of day; I still & shall to Eternity Embrace Christianity and Adore him who is the Express image of God” – Letters of Blake

For the last few decades of his life, he never attended formal worship but saw religion as an inner experience to be held in private. Throughout his life, he experienced mystical experiences and visions of heavenly angels. These experiences informed his poetry, art and outlook on life. It made Blake see beyond conventional piety and value human goodness and kindness. He was a strong opponent of slavery and supported the idea of equality of man.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite.” – Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–1793)

Blake read the Bible and admired the New Testament, he was less enamoured of the judgements and restrictions found in the Old Testament. He was also influenced by the teaching of Emanuel Swedenborg, a charismatic preacher who saw the Bible as the literal word of God. Although Blake was, at times, enthusiastic about Swedenborg, he never became a member of his church, preferring to retain his intellectual and spiritual independence.

Blake died on August 12 1827. Eyewitnesses report that his death was a ‘glorious affair’. After falling ill, Blake sang hymns and prepared himself to depart. He was buried in an unmarked grave in a public cemetery and Bunhill Fields. After his death, his influence steadily grew through the Pre-Raphaelites and later noted poets such as T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats.

The esteemed poet, William Wordsworth , said on the death of Blake:

“There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott.”

The Art of William Blake

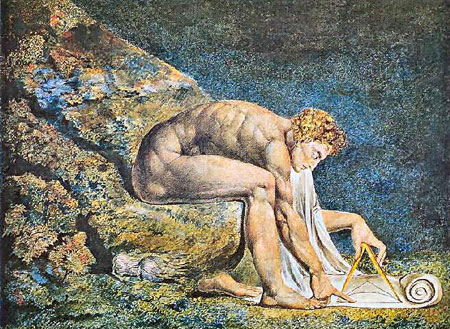

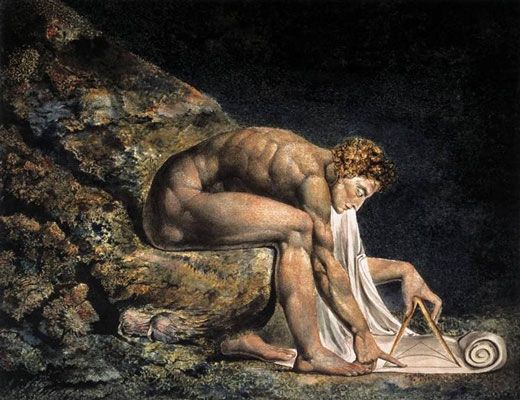

Newton by Blake

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of William Blake” , Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net , 1st June. 2006. Page updated 23rd Jan 2020.

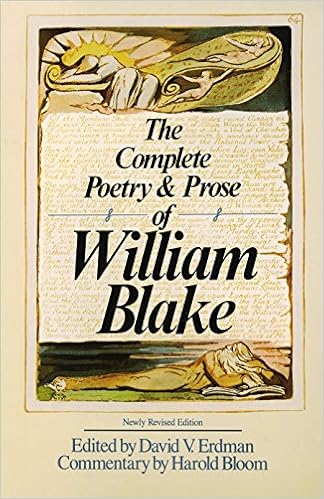

The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake

- The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake at Amazon.com

- The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake at Amazon.co.uk

To See a World in a Grain of Sand

Related pages

William Blake links

- Quotes of William Blake

- William Blake Biography

- William Blake Poetry

Poems & Poets

William Blake

Poet, painter, engraver, and visionary William Blake worked to bring about a change both in the social order and in the minds of men. Though in his lifetime his work was largely neglected or dismissed, he is now considered one of the leading lights of English poetry, and his work has only grown in popularity. In his Life of William Blake (1863) Alexander Gilchrist warned his readers that Blake “neither wrote nor drew for the many, hardly for work’y-day men at all, rather for children and angels; himself ‘a divine child,’ whose playthings were sun, moon, and stars, the heavens and the earth.” Yet Blake himself believed that his writings were of national importance and that they could be understood by a majority of his peers. Far from being an isolated mystic, Blake lived and worked in the teeming metropolis of London at a time of great social and political change that profoundly influenced his writing. In addition to being considered one of the most visionary of English poets and one of the great progenitors of English Romanticism, his visual artwork is highly regarded around the world.

Blake was born on November 28, 1757. Unlike many well-known writers of his day, Blake was born into a family of moderate means. His father, James, was a hosier, and the family lived at 28 Broad Street in London in an unpretentious but “respectable” neighborhood. In all, seven children were born to James and Catherine Wright Blake, but only five survived infancy. Blake seems to have been closest to his youngest brother, Robert, who died young.

By all accounts Blake had a pleasant and peaceful childhood, made even more pleasant by skipping any formal schooling. As a young boy he wandered the streets of London and could easily escape to the surrounding countryside. Even at an early age, however, his unique mental powers would prove disquieting. According to Gilchrist, on one ramble he was startled to “see a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars.” His parents were not amused at such a story, and only his mother’s pleadings prevented him from receiving a beating. His parents did, however, encourage his artistic talents, and the young Blake was enrolled at the age of 10 in Pars’ drawing school. The expense of continued formal training in art was a prohibitive, and the family decided that at the age of 14 William would be apprenticed to a master engraver. At first his father took him to William Ryland, a highly respected engraver. William, however, resisted the arrangement telling his father, “I do not like the man’s face: it looks as if he will live to be hanged!” The grim prophecy was to come true 12 years later. Instead of Ryland the family settled on a lesser-known engraver, James Basire. Basire seems to have been a good master, and Blake was a good student of the craft.

At the age of 21, Blake left Basire’s apprenticeship and enrolled for a time in the newly formed Royal Academy. He earned his living as a journeyman engraver. Booksellers employed him to engrave illustrations for publications ranging from novels such as Don Quixote to serials such as Ladies’ Magazine .

One incident at this time affected Blake deeply. In June of 1780 riots broke out in London incited by the anti-Catholic preaching of Lord George Gordon and by resistance to continued war against the American colonists. Houses, churches, and prisons were burned by uncontrollable mobs bent on destruction. On one evening, whether by design or by accident, Blake found himself at the front of the mob that burned Newgate prison. These images of violent destruction and unbridled revolution gave Blake powerful material for works such as Europe (1794) and America (1793).

Not all of the young man’s interests were confined to art and politics. After one ill-fated romance, Blake met Catherine Boucher. After a year’s courtship the couple were married on August 18, 1782. The parish registry shows that Catherine, like many women of her class, could not sign her own name. Blake soon taught her to read and to write, and under Blake’s tutoring she also became an accomplished draftsman, helping him in the execution of his designs. By all accounts the marriage was a successful one, but no children were born to the Blakes.

Blake’s friend John Flaxman introduced Blake to the bluestocking Harriet Mathew, wife of the Rev. Henry Mathew, whose drawing room was often a meeting place for artists and musicians. There Blake gained favor by reciting and even singing his early poems. Thanks to the support of Flaxman and Mrs. Mathew, a thin volume of poems was published under the title Poetical Sketches (1783). Many of these poems are imitations of classical models, much like the sketches of models of antiquity the young artist made to learn his trade. Even here, however, one sees signs of Blake’s protest against war and the tyranny of kings. Only about 50 copies of Poetical Sketches are known to have been printed. Blake’s financial enterprises also did not fare well. In 1784, after his father’s death, Blake used part of the money he inherited to set up shop as a printseller with his friend James Parker. The Blakes moved to 27 Broad Street, next door to the family home and close to Blake’s brothers. The business did not do well, however, and the Blakes soon moved out.

Of more concern to Blake was the deteriorating health of his favorite brother, Robert. Blake tended to his brother in his illness and according to Gilchrist watched the spirit of his brother escape his body in his death: “At the last solemn moment, the visionary eyes beheld the released spirit ascend heaven ward through the matter-of-fact ceiling, ‘clapping its hands for joy.’"

Blake always felt the spirit of Robert lived with him. He even announced that it was Robert who informed him how to illustrate his poems in “illuminated writing.” Blake’s technique was to produce his text and design on a copper plate with an impervious liquid. The plate was then dipped in acid so that the text and design remained in relief. That plate could be used to print on paper, and the final copy would be then hand colored.

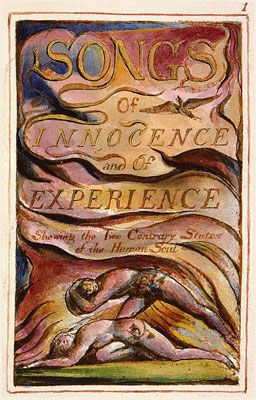

After experimenting with this method in a series of aphorisms entitled There is No Natural Religion and All Religions are One (1788?), Blake designed the series of plates for the poems entitled Songs of Innocence and dated the title page 1789. Blake continued to experiment with the process of illuminated writing and in 1794 combined the early poems with companion poems entitled Songs of Experience . The title page of the combined set announces that the poems show “the two Contrary States of the Human Soul.”

The introductory poems to each series display Blake’s dual image of the poet as both a “piper” and a “Bard.” As man goes through various stages of innocence and experience in the poems, the poet also is in different stages of innocence and experience. The pleasant lyrical aspect of poetry is shown in the role of the “piper” while the more somber prophetic nature of poetry is displayed by the stern Bard.

The dual role played by the poet is Blake’s interpretation of the ancient dictum that poetry should both delight and instruct. More important, for Blake the poet speaks both from the personal experience of his own vision and from the “inherited” tradition of ancient Bards and prophets who carried the Holy Word to the nations.

The two states of innocence and experience are not always clearly separate in the poems, and one can see signs of both states in many poems. The companion poems titled “Holy Thursday” are on the same subject, the forced marching of poor children to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. The speaker in the state of innocence approves warmly of the progression of children:

’Twas on a Holy Thursday their innocent faces clean The children walking two & two in red & blue & green Grey headed beadles walkd before with wands as white as snow Till into the high dome of Pauls they like Thames waters flow[.]

The brutal irony is that in this world of truly “innocent” children there are evil men who repress the children, round them up like herd of cattle, and force them to show their piety. In this state of innocence, experience is very much present.

If experience has a way of creeping into the world of innocence, innocence also has a way of creeping into experience. The golden land where the “sun does shine” and the “rain does fall” is a land of bountiful goodness and innocence. But even here in this blessed land, there are children starving. The sharp contrast between the two conditions makes the social commentary all the more striking and supplies the energy of the poem.

The storming of the Bastille in Paris in 1789 and the agonies of the French Revolution sent shock waves through England. Some hoped for a corresponding outbreak of liberty in England while others feared a breakdown of the social order. In much of his writing Blake argues against the monarchy. In his early Tiriel (written circa 1789) Blake traces the fall of a tyrannical king.

Politics was surely often the topic of conversation at the publisher Joseph Johnson’s house, where Blake was often invited. There Blake met important literary and political figures such as William Godwin, Joseph Priestly, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Thomas Paine. According to one legend Blake is even said to have saved Paine’s life by warning him of his impending arrest. Whether or not that is true, it is clear that Blake was familiar with some of the leading radical thinkers of his day.

In The French Revolution Blake celebrates the rise of democracy in France and the fall of the monarchy. King Louis represents a monarchy that is old and dying. The sick king is lethargic and unable to act: “From my window I see the old mountains of France, like aged men, fading away.” The “voice of the people” demands the removal of the king’s troops from Paris, and their departure at the end of the first book signals the triumph of democracy.

On the title page for book one of The French Revolution Blake announces that it is “A Poem in Seven Books,” but none of the other books has been found. Johnson never published the poem, perhaps because of fear of prosecution, or perhaps because Blake himself withdrew it from publication. Johnson did have cause to be nervous. Erdman points out that in the same year booksellers were thrown in jail for selling the works of Thomas Paine.

In America (1793) Blake also addresses the idea of revolution–less as a commentary on the actual revolution in America as a commentary on universal principles that are at work in any revolution. The figure of Orc represents all revolutions:

The fiery joy, that Urizen perverted to ten commands, What night he led the starry hosts thro’ the wide wilderness, That stony law I stamp to dust; and scatter religion abroad To the four winds as a torn book, & none shall gather the leaves.

The same force that causes the colonists to rebel against King George is the force that overthrows the perverted rules and restrictions of established religions.

The revolution in America suggests to Blake a similar revolution in England. In the poem the king, like the ancient pharaohs of Egypt, sends pestilence to America to punish the rebels, but the colonists are able to redirect the forces of destruction to England. Erdman suggests that Blake is thinking of the riots in England during the war and the chaotic condition of the English troops, many of whom deserted. Writing this poem in the 1790s, Blake also surely imagined the possible effect of the French Revolution on England.

Another product of the radical 1790s is The Marriage of Heaven and Hell . Written and etched between 1790 and 1793, Blake’s poem brutally satirizes oppressive authority in church and state.

The powerful opening of the poem suggests a world of violence: “Rintrah roars & shakes his fires in the burden’d air / Hungry clouds swag on the deep.” The fire and smoke suggest a battlefield and the chaos of revolution. The cause of that chaos is analyzed at the beginning of the poem. The world has been turned upside down. The “just man” has been turned away from the institutions of church and state, and in his place are fools and hypocrites who preach law and order but create chaos. Those who proclaim restrictive moral rules and oppressive laws as “goodness” are in themselves evil. Hence to counteract this repression, Blake announces that he is of the “Devil’s Party” that will advocate freedom and energy and gratified desire.

The “Proverbs of Hell” are clearly designed to shock the reader out of his commonplace notion of what is good and what is evil:

Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion. The pride of the peacock is the glory of God. The lust of the goat is the bounty of God. The wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God. The nakedness of woman is the work of God.

It is the oppressive nature of church and state that has created the repulsive prisons and brothels. Sexual energy is not an inherent evil, but the repression of that energy is. The preachers of morality fail to understand that God is in all things, including the sexual nature of men and women.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell contains many of the basic religious ideas developed in the major prophecies. Blake analyzes the development of organized religion as a perversion of ancient visions: “The ancient Poets animated all sensible objects with Gods or Geniuses, calling them by the names and adorning them with the properties of woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, and whatever their enlarged & Numerous senses could perceive.” Ancient man created those gods to express his vision of the spiritual properties that he perceived in the physical world. The gods began to take on a life of their own separate from man: “Till a system was formed, which some took advantage of, & enslav’d the vulgar by attempting to realize or abstract the mental deities from their objects: thus began Priesthood.” The “system” or organized religion keeps man from perceiving the spiritual in the physical. The gods are seen as separate from man, and an elite race of priests is developed to approach the gods: “Thus men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast.” Instead of looking for God on remote altars, Blake warns, man should look within.

In August of 1790 Blake moved from his house on Poland Street across the Thames to the area known as Lambeth. The Blakes lived in the house for 10 years, and the surrounding neighborhood often becomes mythologized in his poetry. Felpham was a “lovely vale,” a place of trees and open meadows, but it also contained signs of human cruelty, such as the house for orphans. At his home Blake kept busy not only with his illuminated poetry but also with the daily chore of making money. During the 1790s Blake earned fame as an engraver and was glad to receive numerous commissions.

One story told by Blake’s friend Thomas Butts shows how much the Blakes enjoyed the pastoral surroundings of Lambeth. At the end of Blake’s garden was a small summer house, and coming to call on the Blakes one day Butts was shocked to find the couple stark naked: “Come in!” cried Blake; “it’s only Adam and Eve you know!” The Blakes were reciting passages from Paradise Lost , apparently “in character."Sexual freedom is addressed in Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), also written during the Lambeth period.

Between 1793 and 1795 Blake produced a remarkable collection of illuminated works that have come to be known as the “Minor Prophecies.” In Europe (1794), The First Book of Urizen (1794), The Book of Los (1795), The Song of Los (1795), and The Book of Ahania (1795) Blake develops the major outlines of his universal mythology. In these poems Blake examines the fall of man. In Blake’s mythology man and God were once united, but man separated himself from God and became weaker and weaker as he became further divided.

The narrative of the universal mythology is interwoven with the historical events of Blake’s own time. The execution of King Louis XVI in 1793 led to an inevitable reaction, and England soon declared war on France. England’s participation in the war against France and its attempt to quell the revolutionary spirit is addressed in Europe . The very force of that repression, however, will cause its opposite to appear in the revolutionary figure of Orc: “And in the vineyards of reds France appear’d the light of his fury.”

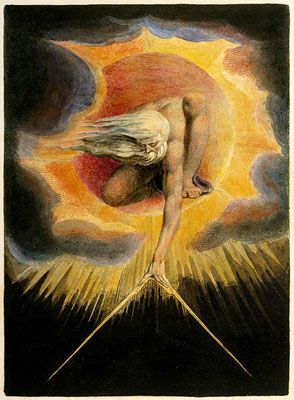

The causes of that repression are examined in The First Book of Urizen . The word Urizen suggests “your reason” and also “horizon.” He represents that part of the mind that constantly defines and limits human thought and action. In the frontispiece to the poem he is pictured as an aged man hunched over a massive book writing with both hands in other books. Behind him stand the tablets of the 10 commandments, and Urizen is surely writing other “thou shalt nots” for others to follow. His twisted anatomical position shows the perversity of what should be the “human form divine."

The poem traces the birth of Urizen as a separate part of the human mind. He insists on laws for all to follow:

One command, one joy, one desire One curse, one weight, one measure, One King, one God, one Law.

Urizen’s repressive laws bring only further chaos and destruction. Appalled by the chaos he himself created, Urizen fashions a world apart.

The process of separation continues as the character of Los is divided from Urizen. Los, the “Eternal Prophet,” represents another power of the human mind. Los forges the creative aspects of the mind into works of art. Like Urizen he is a limiter, but the limitations he creates are productive and necessary. In the poem Los forms “nets and gins” to bring an end to Urizen’s continual chaotic separation.

Los is horrified by the figure of the bound Urizen and is separated by his pity, “for Pity divides the Soul.” Los undergoes a separation into a male and female form. His female form is called Enitharmon, and her creation is viewed with horror:

Eternity shudder’d when they saw Man begetting his likeness On his own divided image.

This separation into separate sexual identities is yet another sign of man’s fall. The “Eternals” contain both male and female forms within themselves, but man is divided and weak.

Enitharmon gives birth to the fiery Orc, whose violent birth gives some hope for radical change in a fallen world, but Orc is bound in chains by Los, now a victim of jealousy. Enitharmon bears an “enormous race,” but it is a race of men and women who are weak and divided and who have lost sight of eternity.

In his fallen state man has limited senses and fails to perceive the infinite. Divided from God and caught by the narrow traps of religion, he sees God only as a crude lawgiver who must be obeyed.

The Book of Los also examines man’s fall and the binding of Urizen, but from the perspective of Los, whose task it is to place a limit on the chaotic separation begun by Urizen. The decayed world is again one of ignorance where there is “no light from the fires.” From this chaos the bare outlines of the human form begin to appear:

Many ages of groans, till there grew Branchy forms organizing the Human Into finite inflexible organs.

The human senses are pale imitations of the true senses that allow one to perceive eternity. Urizen’s world where man now lives is spoken of as an “illusion” because it masks the spiritual world that is everywhere present.

In The Song of Los , Los sings of the decayed state of man, where the arbitrary laws of Urizen have become institutionalized:

Thus the terrible race of Los & Enitharmon gave Laws & Religions to the sons of Har, binding them more And more to Earth, closing and restraining, Till a Philosophy of five Senses was complete. Urizen wept & gave it into the hands of Newton & Locke.

The “philosophy of the five senses” espoused by scientists and philosophers argues that the world and the mind are like industrial machines operating by fixed laws but devoid of imagination, creativity, or any spiritual life. Blake condemns this materialistic view of the world espoused in the writings of Newton and Locke.

Although man is in a fallen state, the end of the poem points to the regeneration that is to come:

Orc, raging in European darkness, Arose like a pillar of fire above the Alps, Like a serpent of fiery flame!

The coming of Orc is likened not only to the fires of revolution sweeping Europe, but also to the final apocalypse when the “Grave shrieks with delight."

The separation of man is also examined in The Book of Ahania , which Blake later incorporated in Vala, or The Four Zoas . In The Book of Ahania Urizen is further divided into male and female forms. Urizen is repulsed by his feminine shadow that is called Ahania:

He groan’d anguish’d, & called her Sin, Kissing her and weeping over her; Then hid her in darkness, in silence, Jealous, tho’ she was invisible.

“Ahania” is only a “sin” in that she is given that name. Urizen, the lawgiver, can not accept the liberating aspects of sexual pleasure. At the end of the poem, Ahania laments the lost pleasures of eternity:

Where is my golden palace? Where my ivory bed? Where the joy of my morning hour? Where the sons of eternity singing.

The physical pleasures of sexual union are celebrated as an entrance to a spiritual state. The physical union of man and woman is sign of the spiritual union that is to come.

The Four Zoas is subtitled “The Torments of Love and Jealousy in the Death and Judgement of Albion the Ancient Man,” and the poem develops Blake’s myth of Albion, who represents both the country of England and the unification of all men. Albion is composed of “Four Mighty Ones": Tharmas, Urthona, Urizen, and Luvah. Originally, in Eden, these four exist in the unity of “The Universal Brotherhood.” At this early time all parts of man lived in perfect harmony, but now they are fallen into warring camps. The poem traces the changes in Albion:

His fall into Division & his Resurrection to Unity: His fall into the Generation of decay & death, & his Regeneration by the Resurrection from the dead.

The poem begins with Tharmas and examines the fall of each aspect of man’s identity. The poem progresses from disunity toward unity as each Zoa moves toward final unification.

In the apocalyptic “Night the Ninth,” the evils of oppression are overturned in the turmoil of the Last Judgment: “The thrones of Kings are shaken, they have lost their robes & crowns/ The poor smite their oppressors, they awake up to the harvest.”

As dead men are rejuvenated, Christ, the “Lamb of God,” is brought back to life and sheds the evils of institutionalized religions:

Thus shall the male & female live the life of Eternity, Because the Lamb of God Creates himself a bride & wife That we his Children evermore may live in Jerusalem Which now descendeth out of heaven, a City, yet a Woman Mother of myriads redeem’d & born in her spiritual palaces, By a New Spiritual birth Regenerated from Death.

Very little of Blake’s poetry of the 1790s was known to the general public. His reputation as an artist was mixed. Response to his art ranged from praise to derision, but he did gain some fame as an engraver. His commissions did not produce much in the way of income, but Blake never seems to have been discouraged. In 1799 Blake wrote to George Cumberland, “I laugh at Fortune & Go on & on."

Because of his monetary woes, Blake often had to depend on the benevolence of patrons of the arts. This sometimes led to heated exchanges between the independent artist and the wealthy patron. Dr. John Trusler was one such patron whom Blake failed to please. Dr. Trusler was a clergyman, a student of medicine, a bookseller, and the author of such works as Hogarth Moralized (1768), The Way to be Rich and Respectable (1750?), and A Sure Way to Lengthen Life with Vigor (circa 1819). Blake found himself unable to follow the clergyman’s wishes: “I attempted every morning for a fortnight together to follow your Dictate, but when I found my attempts were in vain, resolv’d to shew an independence which I know will please an Author better than slavishly following the track of another, however admirable that track may be. At any rate, my Excuse must be: I could not do otherwise; it was out of my power!” Dr. Trusler was not convinced and replied that he found Blake’s “Fancy” to be located in the “World of Spirits” and not in this world. Dr. Trusler was not the only patron that tried to make Blake conform to popular tastes; for example, Blake’s stormy relation to his erstwhile friend and patron William Hayley directly affected the writing of the epics Milton and Jerusalem .

Blake left Felpham in 1803 and returned to London. In April of that year he wrote to Butts that he was overjoyed to return to the city: “That I can alone carry on my visionary studies in London unannoy’d, & that I may converse with my friends in Eternity, See Visions, Dream Dreams & Prophecy & Speak Parables unobserv’d & at liberty from the Doubts of other Mortals.” In the same letter Blake refers to his epic poem Milton , composed while at Felpham: “But none can know the Spiritual Acts of my three years ‘Slumber on the banks of the Ocean, unless he has seen them in the Spirit, or unless he should read My long Poem descriptive of those Acts."

In his “slumber on the banks of the Ocean,” Blake, surrounded by financial worries and hounded by a patron who could not appreciate his art, reflected on the value of visionary poetry. Milton , which Blake started to engrave in 1804 (probably finishing in 1808), is a poem that constantly draws attention to itself as a work of literature. Its ostensible subject is the poet John Milton , but the author, William Blake, also creates a character for himself in his own poem. Blake examines the entire range of mental activity involved in the art of poetry from the initial inspiration of the poet to the reception of his vision by the reader of the poem. Milton examines as part of its subject the very nature of poetry: what it means to be a poet, what a poem is, and what it means to be a reader of poetry.

In the preface to the poem, Blake issues a battle cry to his readers to reject what is merely fashionable in art:

Rouze up, O Young Men of the New Age! set your foreheads against the ignorant Hirelings! For we have Hirelings in the Camp, the Court & the University, who would, if they could, for ever depress Mental & prolong Corporeal War. Painters! on you I call. Sculptors! Architects! suffer not the fashionable Fools to depress your powers by the prices they pretend to give for contemptible works, or the expensive advertizing boasts that they make of such works; believe Christ & his Apostles that there is a Class of men whose whole delight is in Destroying. We do not want either Greek or Roman Models if we are but just & true to our own imaginations, those Worlds of Eternity in which we shall live for ever in Jesus our Lord.

In attacking the “ignorant Hirelings” in the “Camp, the Court & the University,” Blake repeats a familiar dissenting cry against established figures in English society. Blake’s insistence on being “just & true to our own Imaginations” places a special burden on the reader of his poem. For as he makes clear, Blake demands the exercise of the creative imagination from his own readers.

In the well-known lyric that follows, Blake asks for a continuation of Christ’s vision in modern-day England:

I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England’s green & pleasant Land.

The poet-prophet must lead the reader away from man’s fallen state and toward a revitalized state where man can perceive eternity.

"Book the First” contains a poem-within-a-poem, a “Bard’s Prophetic Song.” The Bard’s Song describes man’s fall from a state of vision. We see man’s fall in the ruined form of Albion as a representative of all men and in the fall of Palamabron from his proper position as prophet to a nation. Interwoven into this narrative are the Bard’s addresses to the reader, challenges to the reader’s senses, descriptions of contemporary events and locations in England, and references to the life of William Blake. Blake is at pains to show us that his mythology is not something far removed from us but is part of our day to day life. Blake describes the reader’s own fall from vision and the possibility of regaining those faculties necessary for vision.

The climax of the Bard’s Song is the Bard’s sudden vision of the “Holy Lamb of God": “Glory! Glory! to the Holy lamb of God: / I touch the heavens as an instrument to glorify the Lord.” At the end of the Bard’s Song, his spirit is incorporated into that of the poet Milton. Blake portrays Milton as a great but flawed poet who must unify the separated elements of his own identity before he can reclaim his powers of vision and become a true poet, casting off “all that is not inspiration."

As Milton is presented as a man in the process of becoming a poet, Blake presents himself as a character in the poem undergoing the transformation necessary to become a poet. Only Milton believes in the vision of the Bard’s Song, and the Bard takes “refuge in Milton’s bosom.” As Blake realizes the insignificance of this “Vegetable World,” Los merges with Blake, and he arises in “fury and strength.” This ongoing belief in the hidden powers of the mind heals divisions and increases powers of perception. The Bard, Milton, Los, and Blake begin to merge into a powerful bardic union. Yet it is but one stage in a greater drive toward the unification of all men in a “Universal Brotherhood."

In the second book of Milton Blake initiates the reader into the order of poets and prophets. Blake continues the process begun in book one of taking the reader through different stages in the growth of a poet.

Turning the outside world upside down is a preliminary stage in an extensive examination of man’s internal world. A searching inquiry into the self is a necessary stage in the development of the poet. Milton is told he must first look within: “Judge then of thy Own Self: thy Eternal Lineaments explore, / What is Eternal & what Changeable, & what Annihilable.” Central to the process of judging the self is a confrontation with that destructive part of man’s identity Blake calls the Selfhood, which blocks “the human center of creativity.” Only by annihilating the Selfhood, Blake believes, can one hope to participate in the visionary experience of the poem.

The Selfhood places two powerful forces to block our path: the socially accepted values of “love” and “reason.” In its purest state love is given freely with no restrictions and no thought of return. In its fallen state love is reduced to a form of trade: “Thy love depends on him thou lovest, & on his dear loves / Depend thy pleasures, which thou hast cut off by jealousy.” “Female love” is given only in exchange for love received. It is bartering in human emotions and is not love at all. When Milton denounces his own Selfhood, he gives up “Female love” and loves freely and openly.

As Blake attacks accepted notions of love, he also forces the reader to question the value society places on reason. In his struggle with Urizen, who represents man’s limited power of reason, Milton seeks to cast off the deadening effect of the reasoning power and free the mind for the power of the imagination.

Destroying the Selfhood allows Milton to unite with others. He descends upon Blake’s path and continues the process of uniting with Blake that had begun in book one. This union is also a reflection of Blake’s encounter with Los that is described in book one and illustrated in book two.

The apex of Blake’s vision is the brief image of the Throne of God. In Revelation, John’s vision of the Throne of God is a prelude to the apocalypse itself. Similarly Blake’s vision of the throne is also a prelude to the coming apocalypse. Blake’s vision is abruptly cut off as the Four Zoas sound the Four Trumpets, signaling the call to judgment of the peoples of the earth. The trumpets bring to a halt Blake’s vision, as he falls to the ground and returns to his mortal state. The apocalypse is still to come.

The author falls before the vision of the Throne of God and the awful sound of the coming apocalypse. However, the author’s vision does not fall with him to the ground. In the very next line after Blake describes his faint, we see his vision soar: “Immediately the lark mounted with a loud trill from Felpham’s Vale.” We have seen the lark as the messenger of Los and the carrier of inspiration. Its sudden flight here demonstrates that the vision of the poem continues. It is up to the reader to follow the flight of the lark to the Gate of Los and continue the vision of Milton .

Before Blake could leave Felpham and return to London, an incident occurred that was very disturbing to him and possibly even dangerous. Without Blake’s knowledge, his gardener had invited a soldier by the name of John Scofield into his garden to help with the work. Blake seeing the soldier and thinking he had no business being there promptly tossed him out.

What made this incident so serious was that the soldier swore before a magistrate that Blake had said “Damn the King” and had uttered seditious words. Blake denied the charge, but he was forced to post bail and appear in court. Blake left Felpham at the end of September 1803 and settled in a new residence on South Molton Street in London. His trial was set for the following January at Chichester. The soldier’s testimony was shown to be false, and the jury acquitted Blake.

Blake’s radical political views made him fear persecution, and he wondered if Scofield had been a government agent sent to entrap him. In any event Blake forever damned the soldier by attacking him in the epic poem Jerusalem .

Jerusalem is in many ways Blake’s major achievement. It is an epic poem consisting of 100 illuminated plates. Blake dated the title page 1804, but he seems to have worked on the poem for a considerable length of time after that date. In Jerusalem he develops his mythology to explore man’s fall and redemption. As the narrative begins, man is apart from God and split into separate identities. As the poem progresses man’s split identities are unified, and man is reunited with the divinity that is within him.

In chapter one Blake announces the purpose of his “great task": To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes Of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought, into Eternity Ever expanding in the Bosom of God, the Human Imagination.

It is sometimes easy to get lost in the complex mythology of Blake’s poetry and forget that he is describing not outside events but a “Mental Fight” that takes place in the mind. Much of Jerusalem is devoted to the idea of awakening the human senses, so that the reader can perceive the spiritual world that is everywhere present.

At the beginning of the poem, Jesus addresses the fallen Albion: “’I am not a God afar off, I am a brother and friend; ‘Within your bosoms I reside, and you reside in me.’” In his fallen state Albion rejects this close union with God and dismisses Jesus as the “Phantom of the overheated brain!” Driven by jealousy Albion hides his emanation, Jerusalem. Separation from God leads to further separation into countless male and female forms creating endless division and dispute.

Blake describes the fallen state of man by describing the present day. Interwoven into the mythology are references to present-day London. In chapter two the “disease of Albion” leads to further separation and decay. As the human body is a limited form of its divine origin, the cities of England are limited representations of the Universal Brotherhood of Man. Fortunately for man, there is “a limit of contraction,” and the fall must come to an end.

Caught by the errors of sin and vengeance, Albion gives up hope and dies. The flawed religions of moral law cannot save him: “The Visions of Eternity, by reason of narrowed perceptions, / Are become weak Visions of Time & Space, fix’d into furrows of death.” Our limited senses make us think of our lives as bounded by time and space apart from eternity. In such a framework physical death marks the end of existence. But there is also a limit to death, and Albion’s body is preserved by the Savior.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God “put his head to the window”; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels. Although his parents tried to discourage him from “lying,” they did observe that he was different from his peers and did not force him to attend a conventional school. Instead, he learned to read and write at home. At age ten, Blake expressed a wish to become a painter; so, his parents sent him to drawing school. Two years later, Blake began writing poetry. When he turned fourteen, he apprenticed with an engraver because art school proved too costly. One of Blake’s assignments as apprentice was to sketch the tombs at Westminster Abbey, exposing him to a variety of Gothic styles from which he would draw inspiration throughout his career. After his seven-year term ended, he studied briefly at the Royal Academy.

In 1782, Blake married an illiterate woman named Catherine Boucher. Blake taught her to read and write, and also instructed her in draftsmanship. Later, she helped him print the illuminated poetry for which he is remembered today; the couple had no children. In 1784, Blake set up a print shop with friend and former fellow apprentice, James Parker; but this venture failed after several years. For the remainder of his life, Blake made a meager living as an engraver and illustrator for books and magazines. In addition to his wife, Blake also began training his younger brother, Robert, in drawing, painting, and engraving. Robert fell ill during the winter of 1787, having probably succumbed to consumption. As Robert died, Blake saw his brother’s spirit rise up through the ceiling, “clapping its hands for joy.” He believed that Robert’s spirit continued to visit him and later claimed that in a dream Robert taught him the printing method that he used in Songs of Innocence and other “illuminated” works.

Blake’s first printed work, Poetical Sketches (1783), is a collection of apprentice verse, mostly imitating classical models. The poems protest against war, tyranny, and King George III’s treatment of the American colonies. He published his most popular collection, Songs of Innocence , in 1789 and followed it, in 1794, with Songs of Experience . Some readers interpret Songs of Innocence in a straightforward fashion, considering it primarily a children’s book, but others have found hints at parody or critique in its seemingly naive and simple lyrics. Both books of Songs were printed in an illustrated format reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts. The text and illustrations were printed from copper plates, and each picture was finished by hand in watercolors.

Blake was a nonconformist who associated with some of the leading radical thinkers of his day, including Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft. In defiance of eighteenth-century Neoclassical conventions, he privileged imagination over reason in the creation of both his poetry and images, asserting that ideal forms should be constructed not from observations of nature but from inner visions. He declared in one poem, “I must create a system or be enslaved by another man’s.” Works such as “The French Revolution” (1791), “America, a Prophecy” (1793), “Visions of the Daughters of Albion” (1793), and “Europe, a Prophecy” (1794) express his opposition to the English monarchy, and to eighteenth-century political and social tyranny in general. Theological tyranny is the subject of The Book of Urizen (1794). In the prose work The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93), he satirized the oppressive authority of both church and state, as well as the works of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish philosopher whose ideas once attracted his interest.

In 1800, Blake moved to the seacoast town of Felpham, where he lived and worked until 1803 under the patronage of William Hayley. He taught himself Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Italian, so that he could read classical works in their original language. In Felpham, Blake experienced profound spiritual insights that prepared him for his mature work, the great visionary epics written and etched between about 1804 and 1820. Milton (1804–08); Vala, or The Four Zoas (1797; rewritten after 1800); and Jerusalem (1804–20) have neither traditional plot, characters, rhyme, nor meter. They envision a new and higher kind of innocence—the human spirit triumphing over reason.

Blake believed that his poetry could be read and understood by common people, but he was determined not to sacrifice his vision in order to become popular. In 1808, he exhibited some of his watercolors at the Royal Academy and, in May 1809, he exhibited his works at his brother James’s house. Some of those who saw the exhibit praised Blake’s artistry, but others thought the paintings “hideous” and more than a few called him insane. Blake’s poetry was not well known by the general public, but he was mentioned in A Biographical Dictionary of the Living Authors of Great Britain and Ireland , published in 1816. Samuel Taylor Coleridge , who had been lent a copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience , considered Blake a “man of Genius,” and William Wordsworth made his own copies of several songs. Charles Lamb sent a copy of “The Chimney Sweeper” from Songs of Innocence to James Montgomery for his Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing Boys’ Album (1824), and Robert Southey (who, like Wordsworth, considered Blake insane) attended Blake’s exhibition and included the “Mad Song” from Poetical Sketches in his miscellany, The Doctor (1834–37).

Blake’s final years, spent in great poverty, were cheered by the admiring friendship of a group of younger artists who called themselves “the Ancients.” In 1818, he met John Linnell, a young artist who helped him financially and also helped to create new interest in his work. It was Linnell who, in 1825, commissioned him to design illustrations for Dante ’s Divine Comedy , the cycle of drawings that Blake worked on until his death in 1827.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for “common speech” within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

Walt Whitman

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. While she was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. She died in Amherst in 1886, and the first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

William Blake

British Poet, Painter, and Printmaker

Summary of William Blake

Though he is perhaps still better-known as a poet than an artist, in many ways William Blake's life and work provide the template for our contemporary understanding of what a modern artist is and does. Overlooked by his peers, and sidelined by the academic institutions of his day, his work was championed by a small, zealous group of supporters. His lack of commercial success meant that Blake lived his life in relative poverty, a life in thrall to a highly individual, sometimes iconoclastic, imaginative vision. Through his prints, paintings, and poems, Blake constructed a mythical universe of an intricacy and depth to match Dante's Divine Comedy , but which, liked Dante's, bore the imprint of contemporary culture and politics. When Blake died, in a small house in London in 1827, he was poor and somewhat anonymous; today, we can recognize him as a prototype for the avant-garde artists of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whose creative spirit stands at odds with the prevailing mood of their culture.

Accomplishments

- Blake was perhaps the quintessential Romantic artist. Like his peers in the world of Romantic literature - Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelly - Blake stressed the primacy of individual imagination and inspiration to the creative process, rejecting the Neoclassical emphasis on formal precision which had defined much 18th-century painting and poetry. Above all else, Blake scorned the contemporary culture of Enlightenment and industrialization, which stood for a mechanization and intellectual reductivism which he deplored. Blake felt that imaginative insight was the only way to cast off the veil thrown over reality by rational thought, claiming that "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite."

- Blake is unique amongst the artists of his day, and rare amongst artists of any era, in his integration of writing and painting into a single creative process, and in his use of innovative production techniques to combine image and text in single compositions. Celebrated for his visual output, Blake is also recognized as one of the most radical poets of the early Romantic period, combining a highly wrought, Miltonic style with grand, Gothic themes. Moreover, through original techniques such as his "illuminated printing" Blake was able to adapt his craft to meet the demands of his creativity.

- Blake's spiritual vision was central to his creativity, and was crucially and uniquely informed by a complex, imaginative pantheon of his own making, populated by deities such as Urizen, Los, Enitharmion, and Orc. Grand allegorical narratives illustrated with Blake's own designs, were played out in this universe, which might seem to have existed in a space apart from reality. However, in his epic poem sequences, Blake imagined the fate of the human world, in the era of the French and American Revolutions, as hinging on these sequences, determined by the battles between reason and imagination, lust and piety, order and revolution, which his protagonists represented.

Important Art by William Blake

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Songs of Innocence and Experience , a collection of poems written and illustrated by Blake, demonstrates his equal mastery of poetry and art. Blake printed the collection himself, using an innovative technique which he called 'illuminated printing: first, printing plates were produced by adding text and image - back-to-front, and simultaneously - to copper sheets, using an ink impervious to the nitric acid which was then used to erode the spaces between the lines. After an initial printing, detail was added to individual editions of the book using watercolors. Prone as he was to visions, Blake claimed that this method had been suggested to him by the spirit of his dead brother, Robert. Songs of Innocence was initially published on its own in 1789. Its partner-work, Songs of Experience , followed in 1794 in the wake of the French Revolution, the more worldly and troubling themes of this second volume reflecting Blake's increasing engagement with the politically turbulent era. The cover of Songs of Innocence and Experience includes the subtitle "The Two Contrary States of the Human Soul," a reference to the opposing essences which Blake took to animate the universe, depicted throughout the collection through a range of contrasting images and tropes. Beneath this caption are a man and woman, presumably Adam and Eve, whose bodies mirror each other, but are connected by Adam's leg, another indication of the dualities at work in the book. The use of vibrant color, and the intensity and fluidity of Blake's lines, creates a sense of drama complemented by the figures' anguished appearance. At the same time, the dance-like orientation of their bodies creates an almost childlike sense of play, which jars with the lofty nature of the project. Unappreciated during his lifetime, Blake's illuminated books are now ranked amongst the greatest achievements of Romantic art. They indicate his artisanal approach to his craft - influential on the 'cottage industries' of subsequent printer-poets such as William Morris - and his hatred of the printing press and mechanization in general. The question underlying this collection is how a benevolent God could allow space for both good and evil - or rather, innocence and experience - in the universe, these two necessary and opposing forces summed up by the contrasting images of the lamb and "the tyger", the subjects of the two best-known poems in the sequence. The influence of Blake's "tyger", in particular, its eyes "burning bright,/ In the forests of the night", echoes down through literary and artistic history, seeping into popular culture in a myriad of ways.

Pen and watercolor - Various editions

The Ancient of Days

The Ancient of Days , one of Blake's most recognizable works, portrays a bearded, godlike figure kneeling on a flaming disk, measuring out a dark void with a golden compass. This figure is Urizen, a fictional deity invented by Blake who forms parts of the artist's complex mythology, embodying the spirit of reason and law: two concepts with a very vexed position in Blake's moral universe. Urizen features as a character in several of Blake's illuminated long poems, including Europe: A Prophecy , for which this illustration was created. There, and here, Urizen is a repressive force, impeding the positive power of imagination. This piece can thus be read in light of a famous line from another of Blake's long works, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell : "The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction." In many ways, Blake is the exemplar for our modern conception of the Romantic artist. He prized imagination above all else, describing it not as "a state" but as the essence of "human existence itself." Thus, as The Ancient of Days implies, he disdained attempts to rationally curtail or control the power of imagination. This is also clear from the annotated version of Sir Joshua Reynold's Discourses on Art (1769-91) which he produced around this time. Blake was highly critical of Reynolds, an older and more established artist who, as President of the Royal Academy of Arts, embodied what Blake saw as the formulaic and stultifying ideals of the academy; his teeming marginalia to Reynold's treatise serves in some ways as a conscious affront to these ideals. But if The Ancient of Days also encapsulates the rational spirit Blake was wary of, the undeniable majesty of the figure also reflects his belief in human beings' visionary power, just as his famous and beautiful line from Auguries of Innocence compels the reader "To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/ And Eternity in an hour". With his oppositional critiques of the art establishment, Blake set the stage for artists later in the nineteenth century, like the French painters Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, who deliberately set about to challenge academic paradigms. The Ancient of Days sums up something of the spirit Blake was opposing, but also of the spirit he was endorsing. It is also known to have been one of his favorite images, an example of his early work, but also one of his last works, as he painted a copy of it in bed shortly before his death.

Watercolor etching - Private Collection

This piece, like Songs of Innocence and Experience , was made using Blake's illuminated printing technique. It seems to portray two cherubim, one of whom holds a baby, on white horses in a darkened sky, jumping over a prostrated female figure. The image is generally understood as an interpretation of a passage from Shakespeare's Macbeth : "And pity, like a naked new-born babe,/ Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubin, hors'd/ Upon the sightless couriers of the air,/ Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye". Blake's use of blues and greens, contrasting with the whites of the figures, grants the work a nocturnal, dreamlike quality. Indeed, some scholars have questioned the extent to which the piece draws on Shakespeare's verse, suggesting instead that it might depict figures from Blake's own imaginative pantheon, as its visionary intensity seems to imply. The figure turning away from the viewer might be the god Urizen, for example, the face leaning down from the horse that of Los, an oppositional force to Urizen but also his prophet on earth, who has taken on the female form of Pity - often embodied in the character of his partner, Enitharmion - to enact Urizen's will. The woman below might be Eve, fulfilling the biblical prophecy that "in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children" by generating the miniaturized male figure cradled in Los's arms. By this reading, Pity represents the fall of man, in particular the moment when he becomes aware of his sexuality, and his subjugation to God. Through mythological and literary-inspired works such as Pity , Blake would exert an immense influence on the course of post-Romantic art, including on the Pre-Raphaelites, who often drew on literary and Shakespearean themes, as in John Everett Millais's Ophelia (1851) and John William Waterhouse's Miranda (1916). The hallucinatory quality of works such as Pity , meanwhile, along with their apparent deep allegorical significance, would have a profound effect on movements such as Symbolism and Surrealism.

Relief etching, printed in color and finished with pen and ink and watercolor - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Isaac Newton

In this, perhaps Blake's most famous visual artwork, the mathematician and physicist Isaac Newton is shown drawing on a scroll on the ground with a large compass. He sits on a rock surrounded by darkness, hunched over and entirely consumed by his thoughts. This engraving was developed from the tenth plate of Blake's early illustrated treatise There is No Natural Religion , which shows a man kneeling on the floor with a compass and features the caption "He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God. He who sees the Ratio only, sees himself only". For Blake, Newton was the living embodiment of rationality and scientific enquiry, a mode of intelligence which he saw as reductive, sterile, and ultimately blinding. Isaac Newton is clearly a critical visual allegory, therefore, the sharp angles and straight lines used to mark out Newton's body emphasizing the repressive spirit of reason, while the organic textures of the rock, apparently covered in algae and living organisms, represent the world of nature, where the spirit of human imagination finds its true mirror. The deep, consuming black surrounding Newton, generally taken to represent the bottom of the sea or outer space, indicates his ignorance of this world, his distance from the Platonic light of truth. The compass is a symbol of geometry and rational order, a tool and emblem of the stultifying materialism of the Enlightenment. Blake's scorn for the scientific worldview, which also gave rise to his famous depiction of the god Urizen in The Ancient of Days - another figure who tries to measure out the universe with a compass - is summed up by his assertion that "Art is the Tree of Life. Science is the Tree of Death". Blake's Isaac Newton has been the subject of numerous reproductions, homages, and reinterpretations, and the figure of Newton himself is probably Blake's best-known visual image, perhaps because it sums up his creative credo so perfectly. The image is also famous because it has proved so fascinating to subsequent artists. In 1995, the British pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi created a large number of bronze sculptures inspired by Blake's work, including a huge sculptural homage to Blake's Newton - though both curvier and more machine-like than its predecessor - which now sits outside the British Library in London.

Engraving - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

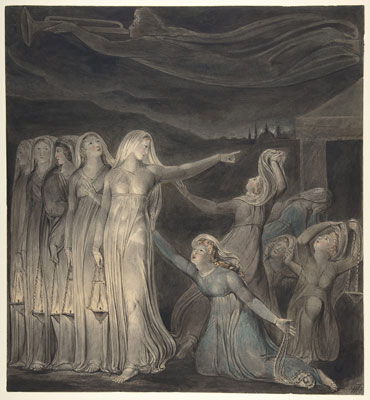

The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins

The painting, finished in pen and ink, illustrates a passage from the Bible, a prophecy described in the Gospel of Matthew as having been used by Jesus to advise the faithful on spiritual vigilance, describing how "A trumpeting angel flying overhead signifies that the moment of judgment has arrived". Blake contrasts the elegant and wise virgins on the left, prepared for the trumpet's call from the angel above, with the foolish virgins on the right, who fall over their feet in agitation and fear. The Parable was commissioned by Blake's patron and friend Thomas Butts, one of a huge number of tempera and watercolor paintings completed by Blake at Butt's behest between 1800 and 1806, all depicting Biblical scenes. Though his own faith was anything but conformist, Blake had a profound respect for the Bible, considering it to be the greatest work of poetry in human history, and the basis of all true art. He often used it as a source of inspiration, and believed that its allegories and parables could serve as a wellspring for creative spirit opposing the rational, Neoclassical principles of the 18th century. The message of Matthew's passage is enhanced here by strong tonal contrasts, the graceful luminosity of the wise women contrasted with the ignominious darkness surrounding them. Works such as The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins were influenced by various Renaissance artists who had explored similar, Biblical themes, and whose work Blake had devoured as a child. Leonardo da Vinci's The Adoration of the Magi (1481-82), The Annunciation (c. 1474), and The Last Supper (c. 1495-98) are good examples of such works, as are Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel frescoes (c. 1508-12), and Fra Angelico's The Madonna of Humility (1430). By not only entering into dialogue with these pieces, but by putting his own gloss on the moral and emotional dynamics of the scene, Blake expressed the ambition of his religious vision.

Watercolor, pen and black ink over graphite - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

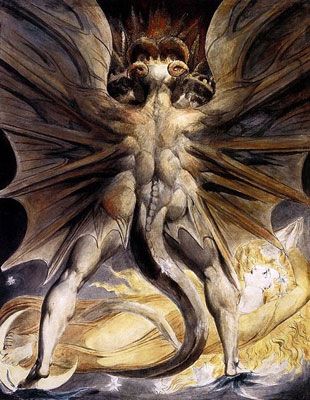

The Great Red Dragon and The Woman Clothed in Sun

This ink and watercolor work depicts a hybrid creature, half human half dragon, spreading its wings over a woman enveloped in sunlight. It belongs to a body of works known as "The Great Red Dragon Paintings", created during 1805-10, a period when Thomas Butts commissioned Blake to create over a hundred Biblical illustrations. The Dragon paintings represent scenes from the Book of Revelation, inspired mainly by the book's apocalyptic description of "a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads". The Great Red Dragon is an example of Blake's mature artistic style, expressing the vividness of his mythological imagination in its dramatic use of color, and its sinuously expressive lines. The poet Kathleen Raine explains that Blake's linear style is characteristic of religious art: "Blake insists that the 'spirits', whether of men or gods, should be 'organized', within a 'determinate and bounding form'." This work also bears out Blake's claim that "Art can never exist without Naked Beauty display'd". Even in the portrayal of a destructive and aggressive subject, beauty, in particular the beauty of the human body, always plays a fundamental and central role in Blake's art: indeed, there is something of the human vigor and strength of Milton's Satan in the central, winged form. Like Blake's Newton, his Great Red Dragon is an image which has permeated artistic and popular culture, particularly during the 20th century. Famously, the main character of Thomas Harris's 1981 novel Red Dragon obsesses over Blake's beast, believing that he can become the dragon himself by emulating its brutal power. The sequels to Harris's novel, Silence of the Lambs (1988) and Hannibal (1999) - adapted, like Red Dragon , into successful films - ensured the cultural resonance of Blake's monstrous but enticingly human creation.

Ink, watercolor and graphite on paper - The Brooklyn Museum, New York

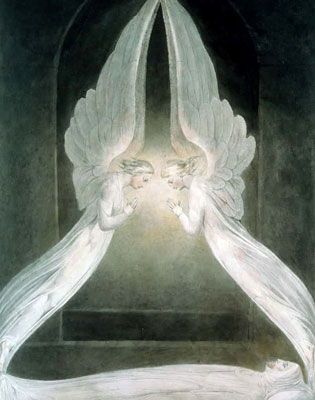

The Angels Hovering Over the Body of Christ in the Sepulchre