- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

Writing Tips: How Writers Can Use Punctuation To Great Effect

posted on March 23, 2018

Commas are my personal nemesis. Those tiny little marks on a page can completely change the sense of a sentence, as per the fantastic book, Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss.

But how do we make the most of punctuation? Rachel Stout from New York Book Editors explains in today's article.

When it comes to grammar and the correct way to do things, I worry more about punctuation than anything else when writing.

Other rules — splitting infinitives, knowing the difference between further and farther or when to use the active voice versus passive — don’t weigh as heavily on my mind. I can just look those up quickly and move on, comfortable with what I’ve written.

But punctuation is not as easily referenced. In a grammar book or online, how do I describe my various clauses and intended meaning so that punctuation can correctly be assessed?

Most of my time is spent evaluating or editing manuscripts, so I can tell you that punctuation rules are some of the most commonly ignored rules in writing.

Either writers admit to me up front that they have no idea whether or not they’ve used way too many commas (answer: yes), improperly used quotation marks (answer: maybe, let me see) or used too few semicolons (answer: almost certainly no).

Understanding how and when to use common punctuation marks (meaning I’m not really interested in discussing interrobangs at the moment, or ever) will not only make you a more sophisticated and practiced writer, but it will give you the ultimate tool: knowing how and when to break those rules and use punctuation to imply feeling and tone in a way that mere word choice cannot.

Breaking punctuation rules is only effective if you’re breaking the rule on purpose.

The words, the flow, the insinuation of pause and of inflection becomes apparent in this case, and instead of mumbo jumbo, the result is something more like Molly Bloom’s “yes I said yes I will Yes,” which closes out an entire punctuation-less chapter that is full of feeling, emotion, swirling thoughts and contradictions, ending on this note of pure bliss at the close of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

“yes I said yes I will Yes” is famous not because the words chosen are anything special, but because no matter whether you’re familiar with the rest of the story, that final paragraph stirs something inside of you when you read it.

The rush of feeling, of teetering on the edge of choice and love and passion and self-doubt is so familiar, so utterly human that it’s palpable without explanation. The careful non-use of punctuation causes the reader to go ever faster, flying through the words, which again themselves aren’t of utmost importance here.

It’s the flying, the racing, the rush of getting everything in because there are no periods or commas to indicate a stop or a pause, nothing to slow the reader down or to shift course. The words themselves are chosen purposefully to accompany the punctuation (or lack thereof), making its use the most important thing in the passage.

How to get there, though? We know that punctuation can change the literal meaning of a sentence. Too many serial comma debates have ended with someone laying down the trump card stating the irrefutable difference between “I love my parents, Beyoncé, and Benedict Cumberbatch” and “I love my parents, Beyoncé and Benedict Cumberbatch” to deny that.

Cormac McCarthy, for example, has been quoted as saying, “I believe in periods, capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it,” and anyone who's read anything of McCarthy’s knows how much effect the starkness of the words and sparseness of punctuation adds to the depth and breadth of his work.

Where in Joyce’s chapter, the lack of punctuation results in a huge rush of intense emotion, McCarthy’s novels are quieter, though still deep in feeling. Neither author could have achieved that if they were writing without knowledge of the rules of punctuation. They were successful because they wrote in spite of them.

The first thing to note when using punctuation creatively is that there are still limitations . Not all punctuation marks can be played around with. You’ll have the best results with commas, periods, quotation marks and dashes.

Semicolons, however, don’t have the same elasticity. Colons and parentheses can be hugely effective when used intentionally, but my advice is to use them sparingly. They cause such an interruption in reading that the pause or aside should be worth it. The aside an em-dash indicates is usually not as drastic as it fits better within the flow of the sentence.

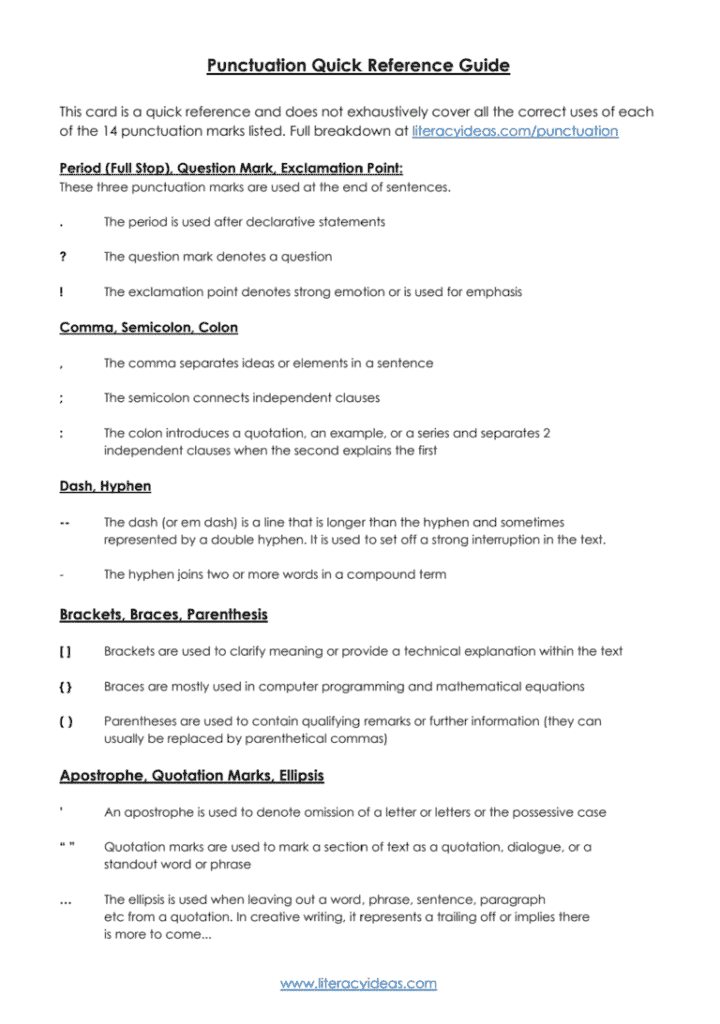

Let’s get the basics of each mark down so we can figure out how to manipulate them. When I say basics, I truly mean basics because of course pages can be written about each, but for our purposes, the basic rules will suffice.

First up, the one with the most rules, even at the basic level: the comma.

Comma Rules and Uses

Separating items in a series.

Commas are used to separate items in a series of three or more nouns or two or more coordinate adjectives. Whether or not you decide to use the serial, or Oxford, comma before the final “and” or “or” in the list is up to you.

- Example (Nouns): I went to the store and bought apples, bananas, bread and milk.

- Example (Coordinate adjectives): The bright, shining sun was warm that day.

(Note: Adjectives are coordinate if you can change their order and the meaning remains the same. If you cannot, they are not coordinate and should not be separated by commas)

Surrounding nonessential appositives

An appositive is the word or phrase that describes or adds additional information about a noun in the sentence. Only nonessential appositives are surrounded by commas. An essential appositive is a word or phrase that if removed, changes the meaning of the sentence. Essential appositives are not offset with commas. If the appositive only adds to the sentence, but does not affect its meaning, then commas are used.

- Example (Essential): Fleetwood Mac’s song Landslide has been covered by many other artists.

Here, “Landslide” is the appositive, but without it, the sentence would not have the same meaning, so we don’t use commas.

- Example (Nonessential): The house where I grew up, a blue bungalow with red shutters, has been repainted.

Here, “a blue bungalow with red shutters” is the appositive and without it, the sentence would retain its meaning: “The house where I grew up has been repainted.” This is why the appositive is offset with commas.

Before a coordinating conjunction

There are many sub-rules here, but at the most basic level, when you are connecting two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction, you should use a comma. An independent clause is a portion of a sentence that could stand on its own and a coordinating conjunction is one of the following: and, nor, for, but, so, or, yet.

- Example: I hate eating apples, but I love eating apple pie.

After an introductory phrase

Usually, an adverbial phrase, the part of the sentence that sets up or introduces its subject and verb is the introductory phrase. (Hint: I started the previous sentence with an introductory phrase offset by a comma!) Sometimes a comma is not used, especially if the introductory phrase is made up of three words or less. (Hint: I did not offset the introductory word in that sentence, and it is grammatically okay).

- Example: After seeing the movie, we all went out for ice cream.

Breaking the Rules

So we know James Joyce doesn’t always love commas, and Cormac McCarthy certainly isn’t a fan. Gertrude Stein didn’t use them much, either, and she did okay for herself.

The most effective thing a comma does in a sentence is to create a pause. It’s a visual breathing mark or break in a sentence that can either go unnoticed or stand out.

Adding a comma where one might not necessarily be required should be an intentional choice—a moment where you are asking the reader to stop, sit up and notice. Maybe you want to call attention to the first part of a sentence or you want to make them pause awkwardly to show awkwardness in a scene.

Maybe you want to not use commas at all in dialogue to indicate a lilted accent or rushed way or speaking, or a child who doesn’t yet have a grasp on his or her own cadence, but you’ll have correct comma usage throughout all narrative portions of the text.

The best hint here? Read your work aloud as it is written, and then read it aloud as you intend it to sound. Are they different? If so, add or subtract the commas—the pauses, the emphases—where desired.

Period Rules and Uses

Ending a declarative sentence: This one doesn’t need too much explaining (I hope!). A period goes at the end of a sentence to indicate, well, its end, unless the sentence is a question or exclamation.

That’s pretty much the only hard and fast rule to using a period, which makes it a much simpler mark than the comma we just barreled through, but there is sometimes confusion as to where a period should be placed in conjunction with other punctuation marks, so here’s a quick overview:

With quotation marks: In American English, the period always goes inside the closing quotation marks. In British English, the period goes outside. After an abbreviation: If you’ve ended a sentence with an abbreviation, like “etc.,” there is no need to add a second period. With parentheses: If the parenthetical statement is its own independent clause placed in between two other full sentences, then the full sentence, including its period, goes inside the parentheses. If the statement is included in the middle of or at the end of another independent clause, the period goes at the end of the non-parenthetical statement and thus, outside of the parentheses.

- Example: I’m good at grammar. (At least I think I am.) A more accurate statement might be: I’m getting the hang of it.

- Example: I’m a grammar pro (and I don’t give myself enough credit).

Because the period is universally simple, it’s difficult to misuse! However, I like to think about the British term for a period when thinking about how best to use it to enhance my writing: the full stop.

Where a comma is a pause, a period is a full stop. Short, fragmented writing, where each phrase, independent clause or not, is separated by a period can indicate so many things. Depression, stilted thinking, disbelief, the inability to comprehend, shock—the list goes on.

Think about any moment in life where you’ve been so overcome by emotion or new information that it’s near impossible to form a complete thought. Using periods to end a sentence fragment, to bring it to a “full stop,” can indicate that numbness or that inability to process.

Of course, the opposite usage is the run-on sentence. Run-on sentences are tricky because so often they are written without intent, but used intentionally, they can indicate a different side of emotional overwhelm .

Instead of being at a loss for words, or indicating a full stop, run-on sentences indicate a racing mind, a fast-paced scene, or a glut of activity and conversation.

Here, our friend the comma comes back into play. Using a comma splice, which is to say using a comma instead of a period, should be done sparingly. If used intentionally and in the right tone, a comma splice can carry the tone of a passage.

See how clearly the image and voice of Holden Caufield becomes through this run-on sentence full of comma splices from J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

You can just see the teenager pretending to be apathetic about lame (and probably phony) things like caring about personal history and family.

Quotation Mark Rules and Uses

To show dialogue: The placement of punctuation inside and outside of quotation marks and whether or not to use single or double quotes vacillates between British and American English as well as between scholars in each school, so I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty here. What you do need to know, is that the most common use of quotation marks in fiction is to indicate dialogue, or someone speaking.

They are not used to indicate a thought, even when a narrator is recalling the idea of what someone said. They are used when recalling the exact words that someone said.

- Example (recalling an idea): John remembered that Susie had told him to put his pants on when he left the house.

- Example (recalling exact words): John remembered Susie’s words so clearly. “If you forget to put your pants on, the neighbors will be angry!” He’d better put them on, he thought to himself.

Note: I threw in a bonus non-quoted thought in that last one!

To show a new person speaking: The rulebooks will tell you that when a new speaker speaks, whether in a conversation between two people or with a narrative paragraph being broken into by a speaker, a new paragraph is necessary. With each new paragraph and each line of dialogue, you must indent.

The most forgiven rules in creative fiction and memoir are those that accompany dialogue, and thus, quotation marks. However, and I’ll keep repeating myself here, it must be done with intention .

It’s very clear when an author is not aware of the rules of where to place punctuation within or outside of quotation marks (though remember, it varies between British and American), or if they are not clear on how to indicate dialogue at all. Usually, these writers are inconsistent with how they indicate or punctuate dialogue.

Consistency is what matters with quotation marks and dialogue. Do you want everything in one line, no quotation marks at all, ala Frank McCourt in Angela’s Ashes? Take a look at how colloquial, familiar, and conversational this feels:

Dad is out looking for a job again and sometimes he comes home with the smell of whiskey, singing all the songs he can about suffering Ireland. Ma gets angry and says Ireland can kiss her arse. He says that’s nice language to be using in front of the children and she says never mind the language, food on the table is what she wants, not suffering Ireland.

On top of the conversational tone and the speed with which you begin to race through the sentence, the perspective here is limited, a little rough around the edges. That’s because at this moment, the narrator is a small child and thus, takes in everything about the world in a particular way.

Using or not using quotes, indenting, breaking paragraphs and all the other rules surrounding dialogue affect style as much as tone.

How do you want the words to look on the page? Many paragraph breaks can achieve the same stilted or at-a-loss feeling as fragmented sentences separated by periods can. The same read aloud test can be used here.

Em-Dashes, Colons, and Parentheses Rules

I’m lumping all of these together because they all achieve a similar goal in creative writing: to indicate an aside, amplify a portion of a sentence or thought, or to offer an alternative point of view.

If you don’t know which to use, my rule of thumb is to always go em-dash, though as I said at the start of this post, you’ve got to be careful not to go overboard.

Using a colon: Unless you’re formatting a list, the only time to use a colon is after an already complete thought. What comes after the colon usually amplifies or expands upon the first portion, but doesn’t indicate much of a pause.

- Example: Sarah has two favorite foods: pizza and ice cream.

Using parentheses: Em-dashes have eclipsed parentheses when used to separate explanatory or qualifying remarks from the rest of the sentence. Using either is correct, but only parentheses can be used to offset a complete sentence or thought, usually as an aside.

Using em-dashes: Aside from replacing parentheses when used within a complete sentence, the em-dash can also set off appositives like commas, indicate a switch in focus, or bring focus to a list connected to a clause.

- Example (replacing parentheses): Mary always said she was an expert in fencing—she’s really not.

- Example (setting off appositives): All three of my dogs—Fluffy, Bumper and Duke—have different personalities.

- Example (switch in focus): And now I will tell you my greatest secret—actually, no, I’ve changed my mind.

- Example (bring focus to a list): Sunscreen, towel, book—everything is packed for the beach!

Here’s where you can have the most fun, in my opinion.

As long as you don’t overuse them, it’s very difficult to misuse a colon, parentheses or em-dash.

Do you want your narrator interjecting his or her own thoughts all the time in a distinctive voice or take on life? Em-dash, em-dash, em-dash!

Do you want to formally and distinctively expand upon a thought, or make that expansion seem like an awaited reveal or an extremely important detail? Use a colon!

Are we getting a whispered aside, an alternative viewpoint, or something special that only the reader gets to know and not others in the story? Do you want to tell a story within a story? Parentheses can achieve that for you!

I often see these three punctuation marks as the playful ones, the marks that can really bring a liveliness to your writing and showcase the voice of a particular character or narrator. Use them sparingly, yes, but play around and see how adding a few em-dashes into your narrative might bring out a new side to your story that even you were unaware was there.

Thanks for going on this whirlwind Punctuation 101 with me. I know it can be exhausting to get down, but once you’ve got the basics firm in your toolbox, you can begin to play with them, alter them to your whim and intentionally manipulate punctuation to change the tone or impact your writing has.

Do you have a favorite punctuation mark? Do you have a favorite author who flagrantly bucks the rules? Please leave your thoughts below and join the conversation.

New York Book Editors are a team of professional editors who have worked with some of the biggest names in the industry as well as offering services to indie authors. They provide in-depth manuscript reviews, manuscript critique, comprehensive edit, proposal edit, copyediting and ghostwriting.

Reader Interactions

March 23, 2018 at 3:13 am

I like breaking the rules when it comes to grammar from time to time. Of course, I keep my writing flow simple and to the point.

I’m talking about writing for a blog here. If we’re talking about writing a book or something it’s a different story.

I don’t think most blog readers really care about how good your grammar is as long as it is okay and they can understand the information you are trying to get across.

But, it is always a good idea to learn the proper grammar and use of a comma. I love commas, they do change the way you deliver information.

Thank you for sharing all of these tips and useful information! 🙂

Have a wonderful weekend! 😀

March 23, 2018 at 3:30 pm

Breaking the rules is the best part about having rules!

March 23, 2018 at 8:23 am

Now *that* is a guide! It covers almost everything people will need, each point is clear, but laid out so it’s genuinely fun. This goes straight into my Perennial Recommendations list– thank you, Rachel!

One rule of thumb I’d like to add, for one extra-common mistake I keep seeing:

If you write the characters endquote-period-lowercase, always change it to endquote-comma-lowercase. Also, if the word after an endquote is a name or other capitalized proper noun, imagine it as a simple pronoun to decide whether it would be lowercase, and if it would be, use the comma as above. Some lines with their corrections, and some that don’t need changing, are:

“Here’s one example.” he said. –> “Here’s one example,” he said. “Another example.” John said. –> “Another example,” John said. “There’s no change needed here.” John had little else to say. “And no change needed needed when it ends without a tag.”

March 23, 2018 at 3:23 pm

Rachel here! Thanks for your note and even MORE for you addition. I thought about adding in a note about that, but then realized I’d be taking up almost the whole thing with commas, so I’m glad you commented!

March 23, 2018 at 3:24 pm

Hah, KEN! I read John in your examples and ran with it. – Rachel

March 24, 2018 at 11:07 am

“John” does a lot of my examples. As for myself, I’v e been called worse things. 🙂

March 24, 2018 at 11:58 pm

I’m obsessed with punctuation, with commas in particular, and sloppy use of the latter can turn me off even a very good book. Thanks for featuring this useful article!

March 30, 2018 at 4:02 pm

I think I overdo commas. That’s what I’m trying to improve.

April 18, 2018 at 7:42 am

Rachel, thank you for this excellent exposition. It’s remarkable to me how many writers I’ve encountered who believe that some punctuation marks should simply never be used. This is a view I’ve never shared. It’s not enough to say, for example, that em-dashes are pointless because commas or parentheses can fulfill the same function (an actual argument one of my writing colleagues once made). False. Em-dashes can be used in ways to achieve emotional effects that commas can’t (as your examples show). And I totally agree with your overriding principle: understanding the how and the when of punctuation, so that you know how to deviate with intention.

May 12, 2018 at 7:58 am

You say, “With quotation marks: In American English, the period always goes inside the closing quotation marks. In British English, the period goes outside.”

My understanding is the in British English, where you put the quotation marks depends on how much of the sentence that the period ends is inside the quotation marks. So, if the whole sentence is a quote, you punctuate the same as in American English. But if only the last two words, or an short phrase within the sentence is at the end, then the quote goes inside the period because the end quote doesn’t cover the entire thing that the period covers. And the reason that Americans don’t want to do it the British way, is that you have to think about where the quote begins to know how to punctuate the end of the sentence.

I think a sentence where the last word is in quotes and you put the end quote outside the period doesn’t really make sense and the British rules make more sense. If they always put the quote inside the period, even when the beginning quote started at the beginning of the sentence, then their rules would also not make sense, I think. The quote really should end after the quoted material with whatever punctuation comes within the quoted material inside the end quote, don’t you think.

There might be a reader who is more of an expert on British English that can tell you if my understanding is really correct.

Thank you for this article. I found it fascinating!

May 13, 2018 at 1:21 am

I think it’s important to recognize that there is never an exactly right answer to many of these questions, as style and usage changes over time and place. There are many variations.

September 12, 2019 at 4:27 pm

It would *surpris!ing* if writers didn’t sometimes utilize! the graphic potential of the medium

September 2, 2020 at 3:11 pm

Which is the correct use of comma with quotation marks – in American English?

1. Tolle calls this emotional part of the Ego the “pain body,” the aspect of the Ego…

2. Tolle calls this emotional part of the Ego the “pain body”, the aspect of the Ego…

December 31, 2020 at 12:19 pm

What about colons instead of commas before a quote? example: The man stood up, said: “Why are you so short?” I’ve read a few stories that use this form of punctuation, which is what I used in my novel. However, I’ve heard some who say that it ruins the flow, like a speed bump. I think it sounds fine–but I wrote it :0)

March 14, 2024 at 3:53 pm

When using three periods to indicatexa pause, often in dialogue, isit … or. . . With spaces? Thanks!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Connect with me on social media

Sign up for your free author blueprint.

Thanks for visiting The Creative Penn!

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

6 Unbreakable Dialogue Punctuation Rules All Writers Must Know

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

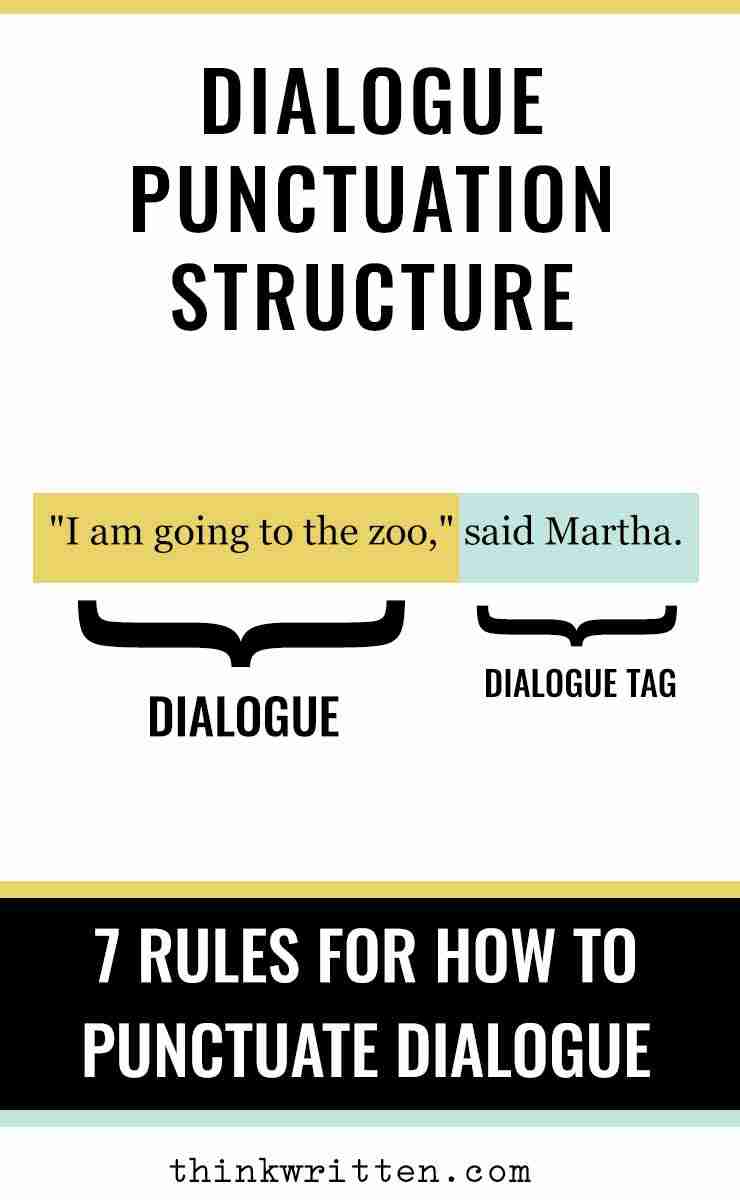

Dialogue punctuation is a critical part of written speech that allows readers to understand when characters start and stop speaking. By following the proper punctuation rules — for example, that punctuation marks almost always fall within the quotation marks — a writer can ensure that their characters’ voices flow off the page with minimal distraction.

This post’ll show you how to format your dialogue to publishing standards.

6 essential dialogue punctuation rules:

1. Always put commas and periods inside the quote

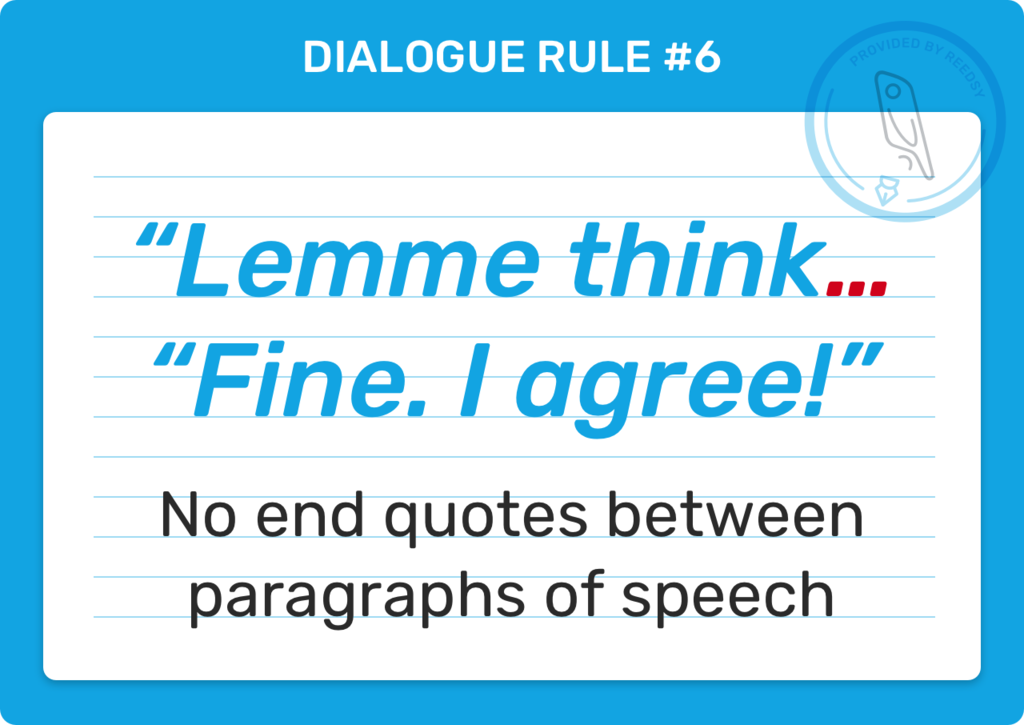

2. use double quote marks for dialogue (if you’re in america), 3. start a new paragraph every time the speaker changes , 4. use dashes and ellipses to cut sentences off, 5. deploy single quote marks used for quotes within dialogue, 6. don’t use end quotes between paragraphs of speech .

The misplacement of periods and commas is the most common mistake writers make when punctuating dialogue. But it’s pretty simple, once you get the hang of it. You should always have the period inside the quote when completing a spoken sentence.

Example: “It’s time to pay the piper.”

As you’ll know, the most common way to indicate speech is to write dialogue in quotation marks and attribute it to a speaker with dialogue tags, such as he said , she said, or Margaret replied, or chirped Hiroko . This is what we call “attribution” when you're punctuating dialogue.

Insert a comma inside the quotation marks when the speaker is attributed after the dialogue.

Example: “Come closer so I can see you,” said the old man.

If the speaker is attributed before the dialogue, there is a comma outside the quotation marks.

Example: Aleela whimpered, “I don’t want to. I’m scared.”

If the utterance (to use a fancy linguistics term for dialogue 🤓) ends in a question mark or exclamation point, they would also be placed inside the quotation marks.

Exception: When it’s not direct dialogue.

You might see editors occasionally place a period outside the quotation marks. In those cases, the period is not used for spoken dialogue but for quoting sentence fragments, or perhaps when styling the title of a short story.

Mark’s favorite short story was “The Gift of the Magi”.

My father forced us to go camping, insisting that it would “build character”.

Now that we’ve covered the #1 rule of dialogue punctuation, let’s dig into some of the more nuanced points.

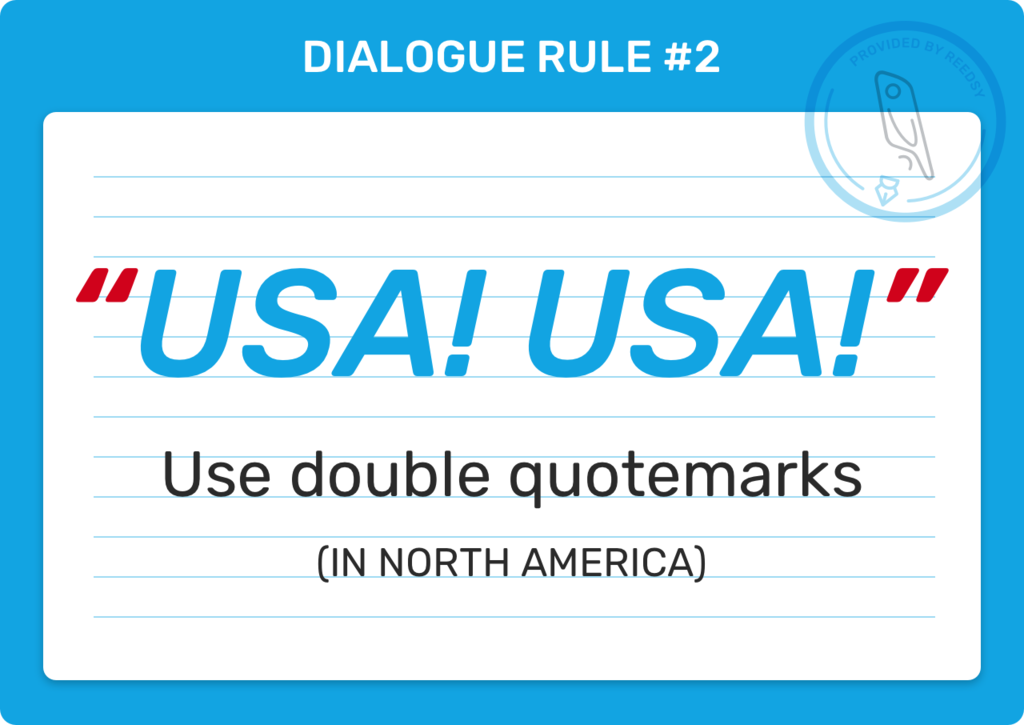

In American English, direct speech is normally represented with double quotation marks.

Example : “Hey, Billy! I’m driving to the drug store for a soda and Charleston Chew. Wanna come?” said Chad

In British and Commonwealth English, single quotation marks are the standard.

Example: ‘I say, old bean,’ the wicketkeeper said, ‘Thomas really hit us for six. Let’s pull up stumps and retire to the pavilion for tea.’

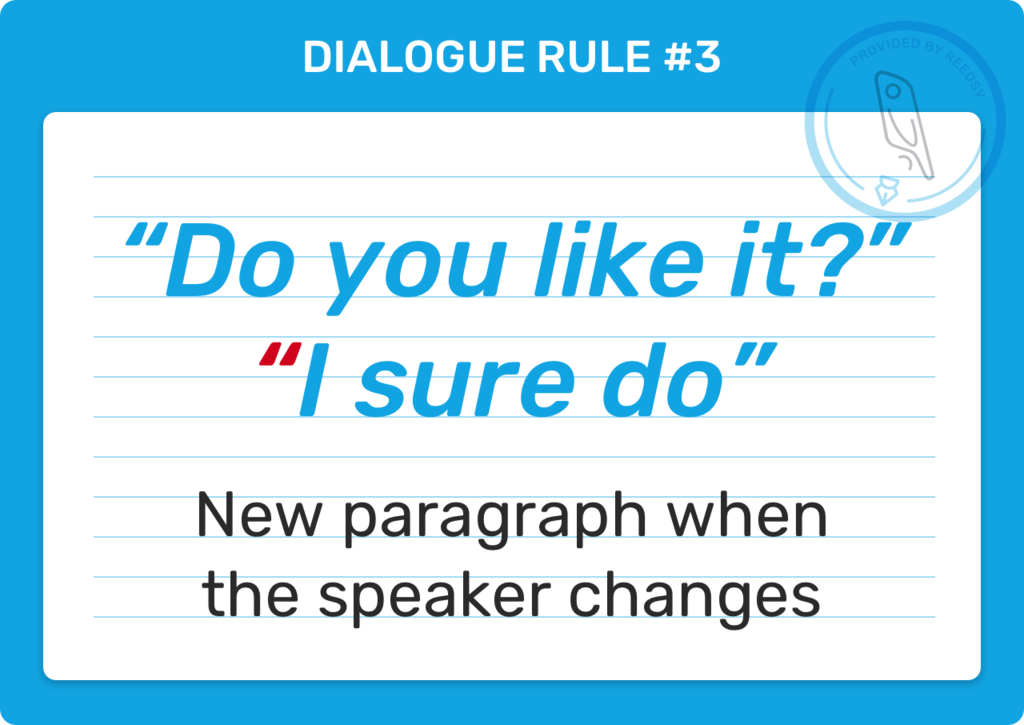

This is one of the most fundamental rules of organizing dialogue. To make it easier for readers to follow what’s happening, start a new paragraph every time the speaker changes, even if you use dialogue tags.

“What do you think you’re doing?” asked the policeman. “Oh, nothing, officer. Just looking for my hat,” I replied.

The new paragraph doesn’t always have to start with direct quotes. Whenever the focus moves from one speaker to the other, that’s when you start a new paragraph. Here’s an alternative to the example above:

“What do you think you’re doing?” asked the policeman. I scrambled for an answer. “Oh, nothing, officer. Just looking for my hat.”

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

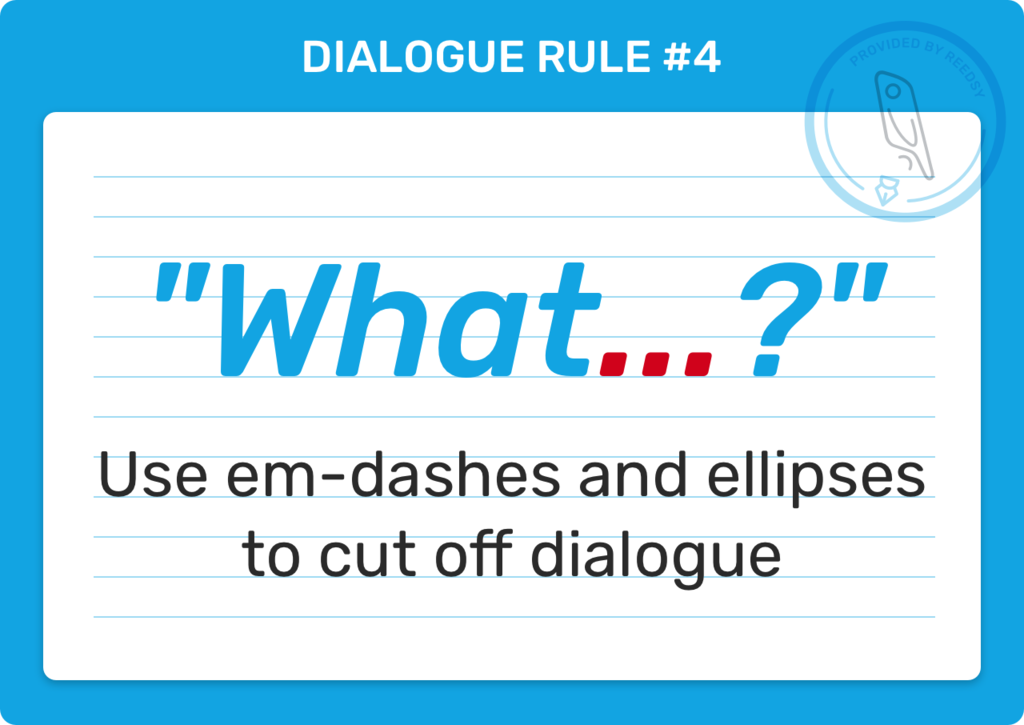

So far, all of the examples we’ve shown you are of characters speaking in full, complete sentences. But as we all know, people don’t always get to the end of their thoughts before their either trail off or are interrupted by others. Here’s how you can show that on the page.

Em-dashes to interrupt

When a speaking character is cut off, either by another person or a sudden event, use an em-dash inside the quotation marks. These are the longest dashes and can be typed by hitting alt-shift-dash on your keyboard (or option-shift-dash for Mac users).

“Captain, we only have twenty seconds before—” A deafening explosion ripped through the ship’s hull. It was already too late.

“Ali, please tell me what’s going—” “There’s no use talking!” he barked.

You can also overlap dialogue to show one character speaking over another.

Mathieu put his feet up as the lecturer continued. "Current estimates indicate that a human mission will land on Mars within the next decade—" "Fat chance." "—with colonization efforts following soon thereafter."

Sometime people won’t finish their sentences, and it’s not because they’ve been interrupted. If this is the case, you’ll want to…

Trail off with ellipses

You can indicate the speaker trailing off with ellipses (. . .) inside the quotation marks.

Velasquez patted each of her pockets. “I swear I had my keys . . .”

Ellipses can also suggest a small pause between two people speaking.

Dawei was in shock. “I can’t believe it . . .” “Yeah, me neither,” Lan Lan whispered.

💡Pro tip: The Chicago Manual of Style requires a space between each period of the ellipses. Most word processors will automatically detect the dot-dot-dot and re-style them for you — but if you want to be exact, manually enter the spaces in between the three periods.

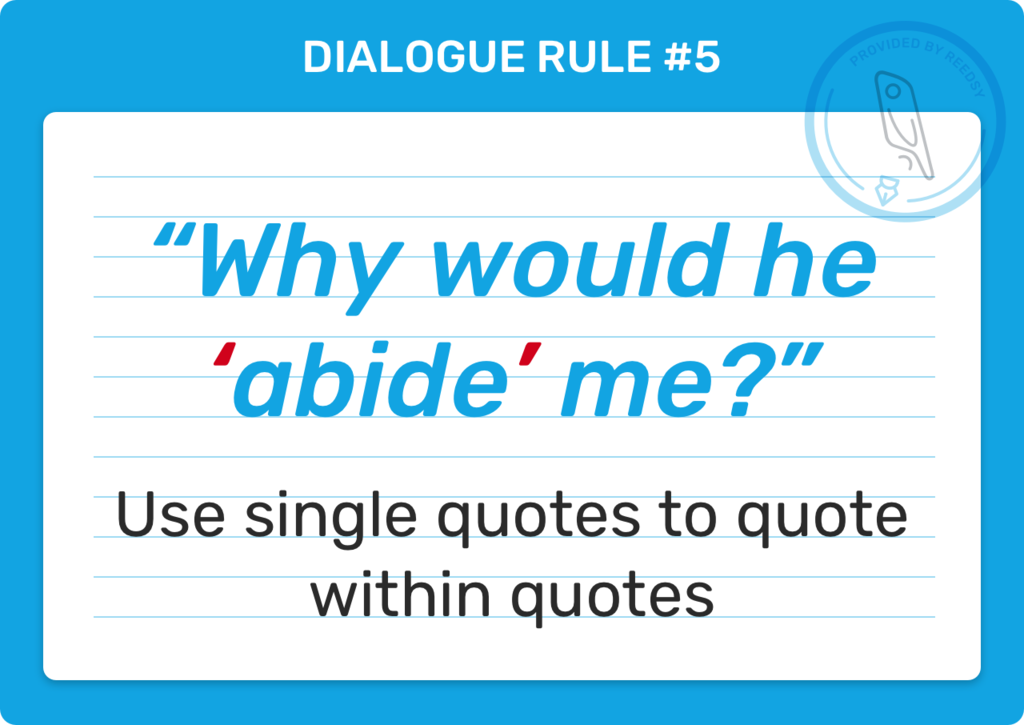

In the course of natural speech, people will often directly quote what other people have said. If this is the case, use single quotation marks within the doubles and follow the usual rules of punctuating dialogue.

“What did Randy say to you?” Beattie asked. “He told me, ‘I got a surprise for you,’ and then he life. Strange, huh?”

But what if a character is quoting another person, who is also quoting another person? In complex cases like this (which thankfully aren’t that common), you will alternate double quotation marks with single quotes.

“I asked Gennadi if he thinks I’m getting the promotion and he said, ‘The boss pulled me aside and asked, “Is Sergei going planning to stay on next year?”’”

The punctuation at the end is a double quote mark, followed by a single quote mark, followed by another double quote. It closes off:

- What the boss said,

- What Gennadi said, and

- What Sergei, the speaker, said.

Quoting quotes within quotes can get messy, so consider focusing on indirect speech. Simply relate the gist of what someone said:

“I pressed Gennadi on my promotion. He said the boss pulled him aside and asked him if I was leaving next year.”

In all the examples above, each character has said fewer than 10 or 20 words at a time. But if a character speaks more than a few sentences at a time, to deliver a speech for example, you can split their speech into multiple paragraphs. To do this:

- Start each subsequent paragraph with an opening quotation mark; and

- ONLY use a closing quotation mark on the final paragraph.

"Would you like to hear my plan?" the professor said, lighting his oak pipe with a match. "The first stage involves undermining the dean's credibility: a small student protesst here, a little harassment rumor there. It all starts to add up. "Stage two involves the board of trustees, with whom I've been ingratiating myself for the past two semesters."

Notice how the first paragraph doesn't end with an end quote? This indicates that the same person is speaking in the next paragraph. You can always break up any extended speech with action beats to avoid pages and pages of uninterrupted monologue.

Want to see a great example of action beats breaking up a monologue? Check out this example from Sherlock Holmes.

Hopefully, these guidelines have clarified a few things about punctuating dialogue. In the next parts of this guide, you’ll see these rules in action as we dive into dialogue tags and look at some more dialogue examples here .

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Catch your errors

Polish your writing in Reedsy Studio, 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- All Editing

- Manuscript Assessment

- Developmental editing: use our editors to perfect your book

- Copy Editing

- Agent Submission Pack: perfect your query letter & synopsis

- Short Story Review: get insightful & actionable feedback

- Our Editors

- All Courses

- Ultimate Novel Writing Course

- Path to Publication: Navigate the world of traditional publishing

- Simply Self-Publish: The Ultimate Self-Pub Course for Indies

- Good To Great

- Self-Edit Your Novel: Edit Your Own Manuscript

- Jumpstart Your Novel: How To Start Writing A Book

- Creativity For Writers: How To Find Inspiration

- Edit Your Novel the Professional Way

- All Mentoring

- Agent One-to-Ones

- First 500 Novel Competition

- London Festival of Writing

- Online Events

- Getting Published Month

- Build Your Book Month

- Meet the Team

- Work with us

- Success Stories

- Novel writing

- Publishing industry

- Self-publishing

- Success stories

- Writing Tips

- Featured Posts

- Get started for free

- About Membership

- Upcoming Events

- Video Courses

Novel writing ,

Punctuation for writers: tips & advice.

By Harry Bingham

Punctuation matters. Correct punctuation tells the reader how to read the words you have on the page: where to put the pauses, how to make sense of your sentences.

It’s not too much to say that bad punctuation will kill a book. It’ll get rejected by agents and readers alike. Trying to sell a badly punctuated manuscript is like going on a date wearing last week’s jogging pants.

The underlying problem is the same in both cases. The badly punctuated manuscript and the dirty jogging bottoms both say, “I don’t care.” I don’t care about you, my hot date. I don’t care about you, my precious reader.

Any sane date will just make their excuses and leave. A reader will do the same – and quite right too.

So here goes with a quick guide to the major punctuation marks. In each case, we’ll talk about:

- The basic rule

- The most common punctuation errors that writers make

- More advanced ways to use the tool

Most of you reading this will know the basic rules. Even so, it’s likely that you’ll be committing at least some of the errors some of the time (a few of them are very common indeed.) And pretty much everyone will get at least something from thinking about how to use punctuation marks in a more sophisticated, writerly way.

The Period, Or Full Stop (.)

OK, you know when to use this little beast. You use it at the end of sentences, so long as those sentences aren’t questions or exclamations (in which case you’d use the “?” or “!” instead.)

Easy, right?

The Most Common Error

One of the most prevalent errors in manuscripts written by first time writers is the so-called run-on sentence. It looks something like this:

She was a breath of fresh air in our little town, she came into school on her first day with a bunch of garden flowers for the teacher and home-made candy for us, her schoolmates, it should have looked cheesy, but we fell in love with her on the spot.

The error here is simple. The writer is using commas (“,”) where they should be using periods. The result is like someone just gabbling in your face, yadda-yadda-yadda, without giving you a chance to draw a breath or reflect.

The solution is simple. You chop the sentence up with periods, to produce this:

She was a breath of fresh air in our little town. She came into school on her first day with a bunch of garden flowers for the teacher and home-made candy for us, her schoolmates. It should have looked cheesy, but we fell in love with her on the spot.

Phew! That’s a mile better already. Notice that there’s still a comma dividing two of the sentences (“It should have looked cheesy” and “we fell in love with her.”)

The grammar-reason why that comma is OK is that you have “but” – a conjunction, a connector word – joining the two sentences. In a way, though, I’d prefer you to forget about the grammar and just listen to the rhythms. Say the first snippet out loud, then the second one. If it feels right, it is right. That’s pretty much all the grammar you are ever going to need.

More Advanced Ways To Use The Tool

Back at school, you were probably told to avoid sentence fragments – the name given to sentences that lack a main verb. (Like this one, for example.)

That’s rather old-fashioned advice in some ways, and it’s certainly unhelpful advice to offer when it comes to writing fiction or creative non-fiction.

Take my own work. My narrator is jerky, tough, awkward, abrupt. Her voice is all those things too, and the consequence is that her prose makes use of a lot of sentence fragments. For instance:

There’s a woman at the wheel. Forties, maybe. Blonde. Shoulder-length hair held back in a grip. Blue woollen coat worn over a dark jumper. I kick the door. Hard. I’m wearing boots and kick hard enough to dent the panel.

Pretty clearly here, the periods are dividing my language up into units of meaning, not into sentences. The words Blonde and Hard are just words, after all. They’re not even attempting to be complete sentences.

Equally clearly, my narrator’s language forces that kind of punctuation on the manuscript. If you wanted to follow the “period = end of sentence” rule, you’d have to rewrite the text so it looked something like this:

There’s a woman at the wheel. She is in her forties, maybe. Her blonde, shoulder-length hair is held back in a grip. She wears a blue woollen coat worn over a dark jumper. [and so on]

That’s not just differently punctuated. It has a different tone, a different mood. It’s perfectly fine writing … but it’s not what I wanted. The “correct” punctuation ends up destroying the voice I worked hard to create.

As a rough, rough guide, literary fiction will tend to have relatively few sentence fragments, while crime thrillers and the like will have many more.

But fiction is much more supple than that general rule suggests. So yes, my character is tough. Yes, she uses lots of sentences fragments in approved noir style. But she also reflects on philosophy, quotes poetry, introspects extensive, and so on. In the end, you build from the character to the voice to the punctuation. It makes no sense to try building the other way.

The Exclamation Mark (!)

An exclamation mark (or point) marks an exclamation, denotes shouting, or otherwise gives emphasis to a sentence. It’s like a shouty form of a period.

But watch out! You think you know how to use the exclamation mark, but …

The most common error is to use the exclamation mark!

It’s fine in emails. It’s OK-ish in blog posts. But in novels? Avoid it. As Scott Fitzgerald remarked, “An exclamation mark is like laughing at your own jokes.” It’s like you’re trying to make your punctuation compensate for a failure of your actual writing.

If you want a rough rule of thumb, you can use one or maximum two exclamation marks per 100,000 words of prose. If you have zero, that’s just fine. And never, ever have a double or treble exclamation mark in your text. What’s fine on Twitter, looks just awful on the printed page.

More Advanced Ways To (Not) Use The Tool

So if I (like most pro authors) hate the exclamation mark, what do you do instead? After all, there may be occasions where you feel your work actually needs the emphasis.

But consider these alternatives:

#1 “Go get it.” #2 “Go get it!” #3 “Go get it,” he ordered her, sharply.

Those options are ranked in approximate order of shoutiness. The first option doesn’t feel especially emphatic. The addition of the exclamation mark adds a little force. The third option adds even more, via a highly coloured verb and adverb combo.

But neither of the last two options is great. And the issue here is simply this: t he actual bit of underlying dialogue is fairly colourless , and that’s not going to change, no matter how many toppings you put on. In other words, if you started out with option #1 and found yourself thinking, “Hmm, this feels a little bland, so let’s get out the heavy-duty punctuation,” that should be a signal that you need to rewrite things.

So a better option than either #1, #2 or #3 above would be:

#4 “Go get it. Get it now. Give it to me. Never take it again.”

You’re not using anything more than a common old period there, and you’re not resorting to ordering sharply, yelling loudly, yodelling wildly or exclaiming defiantly . But because your dialogue is now unmistakeably emphatic, it’s fine on its own.

If the burger tastes great, you don’t need the relish.

The Ellipsis (…)

An ellipsis is a bit of a slippery brute.

What it does is mark the fact that some words are missing. So, in dialogue, for example, people will often trail off, rather than actually complete a sentence.

That much is easy – but how do you actually write it? Three dots is pretty much universal, but do you have spaces between them? Do you have a space before and after the ellipsis? And if you have the ellipsis at the start of a sentence, do you have a period (to denote the end of the previous sentence), then a space, then the ellipsis? That option sounds technically correct, but also rather fussy.

The good news for you is that none of this really matters. Different style authorities advise different things, with some variation between British and American usage.

And in the end, who really cares? Your editor won’t. Your agent won’t. Your reader won’t. It’s just not a big deal. I’d suggest, in general, that you use three dots without spacing in between, but with a space before and after. Like so:

“Oh, Jen, if you really think that, then we should … I mean, maybe this was never meant to be.”

As with exclamation marks, the primary error is to overuse these little beasts. What works fine in an email, quickly looks annoying on the printed page.

But whereas I’d advise you to hunt the exclamation mark almost to extinction, you can let the ellipsis breathe, just a little. One ellipsis per chapter is probably too many, but you’d have to be quite a fussy ready to object to half a dozen, or even a dozen, over the course of a full length novel.

As with the exclamation mark, the best way to use the ellipsis is to let it nudge you into querying your own writing. If you feel yourself wanting to use the ellipsis, just check that it’s not your writing that needs to change. In nine out of ten cases, adjusting your text will be a better option than using the ellipsis.

The Semi-Colon ( ; )

The semi-colon is a divider, the way commas and periods are dividers. The comma is the lightest of these in weight: it inserts the shortest of pauses. The period inserts the maximum pause. The semi-colon lives somewhere in between. Here’s an example of all three in action:

It never normally rained, but the weather that day was awful. (comma = minimal pause) It never normally rained; my mother didn’t even own an umbrella (semi-colon = mid-weight pause) It never normally rained. That day, though, there was a deluge. (period = strongest pause)

And look: you can live without the semi-colon completely. Personally, I quite like semi-colons, but my narrator, Fiona Griffiths, never uses them, so in about 750,000 words of published Fiona Griffiths’ novels, there’s only one semi-colon – and that enters the text via a direct quote from Wikipedia.

Short message: if the semi-colon scares you, it’s fine to leave it well alone.

There are no common errors with semi-colons, except maybe overuse by people thinking they’re fancy.

Thinking of semi-colons as a middle-weight pause is technically correct, but it misses something, nevertheless. A better way to conceive of the mark is this: You need a semi-colon when you have two sentences, and the second one corrects or modifies the meaning of the first .

So take those examples above. We used a semi-colon in this context:

It never normally rained; my mother didn’t even own an umbrella.

The first sentence is, in effect, adjusted by the second. The semi-colon tells us to read the second sentence as a kind of comment on the first one: “look, here’s just how much it never rained.”

Or, if you want a slightly more grown-up example, here’s William Faulkner in The Sound and the Fury :

Clocks slay time… time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life.

But you can get too hung up on these things. Arguably, sentences that speak about each other shouldn’t need any punctuation to get their point across. The text itself should handle the communication just fine. So there’ll be plenty of writers (including my narrator) who’d agree with Kurt Vonnegut’s lesson in creative writing:

First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college.

And who cares if you’ve been to college, right?

Parenthesis

Brackets () | Dashes – – | Commas ,,

There are three types of parenthesis you can use. They are:

- Commas : The comma, always a useful creature, can be used to separate one clause from the rest.

- Dashes : The dash – a more forceful beast – can be used in much the same way.

- Brackets : The bracket (perfectly fine in non-fiction) is relatively rare in fiction.

But these three are not equivalent, and not equally common.

I just opened up my Word document that contains the entire Fiona Griffiths series, and checked to see how many of each punctuation mark I used. In about 650,000 words of text, I used:

- 39,000 commas, of which, admittedly, many thousand wouldn’t be parenthetical.

- 5,000 dashes, though most of these were actually hyphens, as in “short-tempered”. So I’m going to guess maybe only 1,000 actual dashes.

- 100 brackets , of which many were things like “in Paragraph 22(c)”, where the use of the bracket isn’t really a parenthesis in the normal way.

There are two common errors when it comes to parenthesis. The first error is not to use anything to mark off a clause from the rest of a sentence resulting in (often, but not always) a sentence that is just plain hard to read. For example:

The comma always a useful creature can be used to separate one clause from the rest.

Tucking commas in around the useful-creature clause makes the meaning pop right out.

The second error is kind of the opposite. It’s as though writers get worried that commas aren’t emphatic enough, so they start clamping their text inside brackets, like this:

She couldn’t get enough of him (understandable, given her past), so she tried to find reasons why he couldn’t leave.

And that feels heavy-handed. A simple rewrite releases the sentence and lets it breathe:

Understandably, given her tangled past, she couldn’t get enough of him and she tried to find reasons why he couldn’t leave.

There’s more flow there. Less sense of an author forcing information at you. The no-brackets alternative seems much more natural to fiction. The with-brackets version is better suited to the information-delivery task of non-fiction.

More Advanced Ways To Use Parenthesis

The real trick with parenthesis – and with commas particularly – is to learn to feel the weight of a sentence.

In most cases, commas will cover your parenthetical needs. If you need to rewrite something to make it work, then rewrite it. If you need the greater weight of dashes, then go for it, but recognise that you are, in a small way, pulling on the handbrake mid-sentence. If that’s what you want, fine. In many cases, there’ll be better options.

Oh, and though I personally never read my text out loud, lots of authors swear by it – and any hiccups or awkwardness as you read is a huge clue that your punctuation or your text (or both) are at fault.

Hyphens And Dashes

The hyphen, the en dash, and the em dash

We can’t quite leave a post about punctuation without talking about the various dashes available to you. Specifics in one second, but first, a public annoucement:

The specifics don’t really matter.

Yes, a lot of writers (especially those college-educated brutes that got Vonnegut all riled up) care a lot about their en dashes and their em dashes. But if you’ve never spent a moment caring about them in the past, you don’t have to worry that you’ve been doing something very wrong. You haven’t. Any “errors” on this scale will bother almost nobody – neither readers, nor agents.

So, here’s what hyphens and dashes are and how to use them.

The hyphen is on your keyboard as a minus sign.

You use it to connect words, as for example:

The hot-headed wood-cutter tip-toed past the one-eyed she-wolf.

Apart from a slight anxiety about whether a hyphen is needed in a particular context (is it woodcutter or wood-cutter ?), it’s hard to get these little fellows wrong. Oh, and although everyone will have a house-style defining when to use hyphens, everyone’s style guide will be a bit different, so there’s often not a clear right and wrong here anyway.

The En Dash

The en dash is so called because it is a dash approximately the same width as the letter N. And it doesn’t live on your keyboard anywhere: you have to give it life and breath all by yourself. You do this by hitting Ctrl and the minus sign at the same time, to give yourself something that looks like this:

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

As that example suggests, it’s used mostly for dates, or for things that feel much the same, for example: Washington–New York (in the context of a flight timetable, for example.)

The Em Dash

The em dash is so called because … well, you’re going to have to guess which letter-width it’s named after.

You create this little critter in Word by hitting Ctrl-Alt-minus.

And the em dash performs the following functions:

- It marks an interruption in dialogue. “The buried treasure,” he said, as he lay dying, “the treasure can be found just to the right of the old—”

- It marks a parenthesis in the middle of a sentence. The em dash—more forceful than commas—marks out a parenthesis in the middle of a sentence.

- But it can also mark out a parenthesis at the end of a sentence. He was allergic to fruit, sunshine, exercise and soap—or so he always insisted. (The “so he always insisted” part is the parenthesis here. If you were using brackets, that whole end chunk would be enclosed in brackets.)

- It can be used as a slightly informal colon. The result of that informal colon—often a little hint of comedy, or something of a “ta-daa” quality.

- It marks deleted or redacted words. The accuser, Ms — —, struck a defiant tone in court.

Best practice is generally to use the em dash without a space before or after, but that’s one of those things that doesn’t actually matter. Newspapers tend to use spaces and British usage is much more tolerant of spacing and lots of people just don’t know the rules anyway.

That’s it from me. Beautiful punctuation is often a sign of careful writing and a beautifully readable book.

About the author

Harry has written a variety of books over the years, notching up multiple six-figure deals and relationships with each of the world’s three largest trade publishers. His work has been critically acclaimed across the globe, has been adapted for TV, and is currently the subject of a major new screen deal. He’s also written non-fiction, short stories, and has worked as ghost/editor on a number of exciting projects. Harry also self-publishes some of his work, and loves doing so. His Fiona Griffiths series in particular has done really well in the US, where it’s been self-published since 2015. View his website , his Amazon profile , his Twitter . He's been reviewed in Kirkus, the Boston Globe , USA Today , The Seattle Times , The Washington Post , Library Journal , Publishers Weekly , CulturMag (Germany), Frankfurter Allgemeine , The Daily Mail , The Sunday Times , The Daily Telegraph , The Guardian , and many other places besides. His work has appeared on TV, via Bonafide . And go take a look at what he thinks about Blick Rothenberg . You might also want to watch our " Blick Rothenberg - The Truth " video, if you want to know how badly an accountancy firm can behave.

Most popular posts in...

Advice on getting an agent.

- How to get a literary agent

- Literary Agent Fees

- How To Meet Literary Agents

- Tips To Find A Literary Agent

- Literary agent etiquette

- UK Literary Agents

- US Literary Agents

Help with getting published

- How to get a book published

- How long does it take to sell a book?

- Tips to meet publishers

- What authors really think of publishers

- Getting the book deal you really want

- 7 Years to Publication

Get to know us for free

- Join our bustling online writing community

- Make writing friends and find beta readers

- Take part in exclusive community events

- Get our super useful newsletters with the latest writing and publishing insights

Or select from our premium membership deals:

Premium annual – most popular.

per month, minimum 12-month term

Or pay up front, total cost £150

Premium Flex

Cancel anytime

Paid monthly

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cfduid | 1 month | The cookie is used by cdn services like CloudFare to identify individual clients behind a shared IP address and apply security settings on a per-client basis. It does not correspond to any user ID in the web application and does not store any personally identifiable information. |

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| JSESSIONID | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. | |

| PHPSESSID | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. | |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by CloudFare. The cookie is used to support Cloudfare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| GCLB | 12 hours | This cookie is known as Google Cloud Load Balancer set by the provider Google. This cookie is used for external HTTPS load balancing of the cloud infrastructure with Google. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | This cookie is used to a profile based on user's interest and display personalized ads to the users. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description |

| _hjid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Hotjar. This cookie is set when the customer first lands on a page with the Hotjar script. It is used to persist the random user ID, unique to that site on the browser. This ensures that behavior in subsequent visits to the same site will be attributed to the same user ID. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_cookie_expiry | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_landing | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_visit | 3 months | No description |

| CONSENT | 16 years 8 months 4 days 9 hours | No description |

| InfusionsoftTrackingCookie | 1 year | No description |

| m | 2 years | No description |

8 Essential Rules for Punctuating Dialogue - article

Dialogue is a critical component to a great book: it drives action; it reveals character; and it relays facts and information. Writing realistic, compelling dialogue takes skill and practice—and so does punctuating it correctly. Dialogue has its own set of rules that can be tricky to keep straight. Here are eight essential rules for punctuating dialogue correctly, so that your text communicates clearly and appears polished and professional.

1. Use a comma to introduce text

When writing dialogue, place a comma before your opening quote. There is, however, an exception to this rule: no comma is needed when you introduce text using a conjunction, such as that or whether .

She said, "It's all in the details."

He told me that "there are 1,008 different reasons to write."

2. Use a comma when a dialogue tag follows a quote

While your character may have just spoken a complete sentence, you may not need to end it with a period. When dialogue is followed by a tag (for example, he said, asked, replied ), then use a comma before the closing quote when you would normally use a period. If no tag follows the text, end the dialogue with punctuation to end the spoken sentence. This rule applies only to periods. You should not omit other punctuation that adds meaning or clarity to the sentence, such as an exclamation point or question mark.

"Let go of your fears," he replied.

"Write from your heart," she stated. "It's the best way to reach the reader."

"When is the best time to write?" she asked.

"Now!" he answered.

3. Periods and commas fall within closing quotations

When closing a quotation, a period or comma always falls within the quotation, not outside of it.

"All of these rules are starting to make sense."

"It's a matter of practice," he said.

She explained, "You just need to understand each rule."

4. Question marks, exclamation points, and dashes fall inside or outside closing quotations

In dialogue, question marks, exclamation points, and em dashes typically fall within closing quotation marks. However, it depends on the usage and meaning. These punctuation marks may fall outside of the closing quotation mark in some cases.

"Four!" he shouted, as he whacked the ball off the tee.

Congratulations to "the man who has it all"!

"Are you joining us today?" she asked.

Which book contains the phrase, "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times"?

She said, "I can do this"— and that's when she began her career in writing.

5. Use single quotes when using quotes within dialogue

Use a pair of single quotes nested within doubles to indicate quoted text within dialogue. Note that there is no added space in between the closing single and double quotation mark.

"When doling out dessert, my grandmother always said, 'You may have a cookie for each hand.'"

He said, "I've heard that this one is 'the phone for the next generation,' but I'm not sold on it yet."

6. Use capitalization to indicate the end of the sentence

When writing dialogue, only capitalize the first letter of a word to indicate the end of the sentence. There may be times when you end the quote with punctuation that would normally require the next word to be capitalized, such as an exclamation point or question mark. But unless the sentence is truly over, use a lowercase letter to follow this punctuation.

"He's here! He's here!" she screamed.

"Would you like to answer the door?" she asked.

"What do you mean," he said to Jenna, "by asking me to dinner?"

7. Use paragraph breaks to indicate a change in speaker

In dialogue, a new paragraph is used each time there's a change in speaker. This helps with clarity and can eliminate the need to add tags after each line of dialogue. Here's an example from A Tale of Two Cities :

"You know the Old Bailey well, no doubt?" said one of the oldest of clerks to Jerry the messenger.

"Ye-es, sir," returned Jerry, in something of a dogged manner. "I do know the Bailey."

"Just so. And you know Mr. Lorry?"

"I know Mr. Lorry, sir, much better than I know the Bailey. Much better," said Jerry, not unlike a reluctant witness at the establishment in question, "than I, as a honest tradesman, wish to know the Bailey."

8. When in doubt, look it up

The rules for punctuating dialogue are established for the sake of clarity. Follow the rules, and you can communicate your message clearly to your reader. You can find more details and examples to special cases in The Chicago Manual of Style . Also, rely on a good copy editor to help you catch any errors in dialogue punctuation you may have missed.

- E. Claire</a> likes this" data-format="<span class="count"><span class="icon"></span>{count}</span>" data-configuration="Format=%3Cspan%20class%3D%22count%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22icon%22%3E%3C%2Fspan%3E%7Bcount%7D%3C%2Fspan%3E&IncludeTip=true&LikeTypeId=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000" >

Top Comments

You have given petty good tips on punctuation which is not known by many students. I am preparing my own articles now and your tips and tutorials are helpful in framing my sentences with good grammar.

intresting im only 11 yrs old and im intrested

- olivia</a> likes this" data-format="{count}" data-configuration="Format=%7Bcount%7D&IncludeTip=true&LikeTypeId=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000" >

I often have doubts, especially when I need to use punctuation in my gothic narratives, where there are sounds and screams which I have to render by text and then incorporate the general idea of fear and awe. I was a business writer a couple of years ago, so it's a drastic change for me in fiction

Quite helpful, thank you!

© Copyright 2018 Author Learning Center. All Rights Reserved

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Punctuating and Formatting Dialogue in Fiction

4-minute read

- 8th February 2019

Dialogue – i.e., the words spoken by characters in a story – is a vital part of fiction . And to make sure your story is easy to read, you need to present the dialogue clearly. So to make sure your writing is perfect, check out our guide to punctuating and formatting dialogue in fiction.

1. Basic Punctuation and Dialogue Tags

The most important thing about dialogue in fiction is to use quote marks . These are sometimes even known as “speech marks,” as they indicate that someone has said something. All you need to do in this respect is place spoken dialogue within quote marks:

“ That is the biggest horse I have ever seen, ” said Craig.

In American English, as shown above, we use double quotes marks for dialogue. You may also have noticed some words outside the quote marks here. This is a dialogue tag . You can use dialogue tags to show who is speaking in a passage of dialogue (in this case, someone called “Craig”).

2. Quotes within Dialogue

If a character in your story is quoting someone else in their speech, use single quotation marks to enclose the quote within the main speech marks. Take the following line of dialogue, for example:

“He called me an ‘ arrogant fool ’ when I said I’d seen bigger horses.”

Here, we have single quote marks around the words “arrogant fool.” This shows us that the speaker is quoting someone while they are speaking.

3. New Speaker, New Paragraph

A good guideline when formatting dialogue is “new speaker, new paragraph.” This means that when someone new starts speaking, you set the dialogue on a new line. For instance:

Craig stared at the massive horse. “So huge,” he muttered to himself. “What are you doing?” asked Shannon, emerging from the farmhouse. “I’m watching this massive horse,” Craig said. “I can see that,” Shannon said. “But you’ve been here for six hours, Craig.”

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

In the passage above, we have dialogue from two characters. As such, we use line breaks to help the reader keep track of who is speaking, beginning a new line each time the speaker changes.

4. Formatting Long Speeches

One passage of dialogue may require multiple paragraphs. For instance, a character may be telling another character a story within a story as part of your narrative, which could involve them speaking at length. And when this happens, it may not be obvious how to punctuate the dialogue.

The answer here is to use a quotation mark at the start of each paragraph when formatting dialogue. However, you will only use a closing quotation mark when the character finally finishes speaking:

Craig sighed. “I’ve always been obsessed with horses,” he explained. “When I was a child, I spent weekends on my grandparents’ farm. But all they had were miniature ponies. And they told me that all horses were the same size. They said the ones I saw on television looked bigger because they hired tiny actors to ride them. And I believed it.

“Or, I did until I was eighteen, anyway. That’s when I met Clayton Moore, the guy who played the Lone Ranger on TV. And he was over six feet tall, so I knew that Silver couldn’t have been as small as the ponies on my grandparents’ farm! It had all been a lie! I felt so betrayed. And ever since then, I have been looking for the biggest horse I can find.”

In the passage above, for instance, we do not use a closing quotation mark at the end of the first paragraph because it is only half way through Craig’s dialogue. At the end of the second paragraph, however, we use a speech mark to show that Craig has finished speaking.

5. Ellipses and Dashes

Finally, you can use ellipses and dashes to indicate interruptions in dialogue. And while there are no strict rules about how this works, we suggest the following guidelines:

- Use ellipses to show that speech has trailed off (e.g., “I don’t know why you have a problem with…” Craig said, before falling into silence ).

- Use an en dash or em dash to indicate speech that ends suddenly (e.g., “You need to take th–” Shannon began, before the horse neighed loudly ).

This will help your reader tell the difference between dialogue that trails off and dialogue that is suddenly interrupted.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template (2024)

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Northern Illinois University Effective Writing Practices Tutorial

- Make a Gift

- MyScholarships

- Huskie Link

- Anywhere Apps

- Huskies Get Hired

- Student Email

- Password Self-Service

- Quick Links

Punctuation

Punctuation fills our writing with silent intonation. We pause, stop, emphasize, or question using a comma, a period, an exclamation point or a question mark. Correct punctuation adds clarity and precision to writing; it allows the writer to stop, pause, or give emphasis to certain parts of the sentence.

This section of the tutorial covers the most general uses of punctuation marks. Special attention is given to the most common mistakes that occur when punctuation does not follow standard written English conventions. The guidelines and examples given here do not offer a comprehensive analysis of all punctuation uses, rather a quick overview of some of the most frequent punctuation mistakes students make in writing. The section also covers the use of apostrophes and capital letters; these do not directly refer to punctuation but more to mechanics and spelling. However, just as with punctuation marks, knowledge of their proper use is intrinsic to good writing.

Take the Quick Self-Test to identify the common punctuation mistakes you may encounter in your writing. Follow the links included in the answers to the quiz questions to learn more about how to correct or avoid each punctuation mistake. If you prefer, you may review the entire punctuation section.

Quick Self-Test

Review Punctuation

- Capitalization

- Parentheses

- Comma Splice

- Run-on Sentences

- Sentence Fragments

- Organization

Home » Blog » Punctuation Guide » Punctuation Rules: A Comprehensive Guide

Punctuation Rules: A Comprehensive Guide

Punctuation rules are really the backbone in written communication, and yet many of us largely take them for granted. Imagine, if you will, a road without signs. Very odd, isn’t it? Writing in which proper punctuation is absent is quite similar to that. Punctuation marks serve to inform the reader about pauses, stops, and the emotional feelings that the writing is trying to convey. This ensures that the sentences communicate what you intended, and therefore are easily comprehensible.

Below is a comprehensive guide on key punctuation marks, discussion of common pitfalls, and best practice tips to ensure that you get it right.

Key Punctuation Marks and Punctuation Rules

One of the most basic marks of punctuation, the period indicates that a declarative or imperative sentence has come to an end. It tells the reader that a thought or statement is at its end too. Periods are important for clarity; without them, sentences can turn into long, rambling thoughts and strings of ideas that can confuse readers. Sentences break up complex ideas into manageable chunks.

Wrong: The sun set the sky turned dark.

Correct: The sun set. The sky turned dark.

Periods also indicate abbreviations (Dr., Mr., etc.). Modern usage often dispenses with them in these cases, though. The only exceptions are very formal writing, with this usage rarely seen in electronic media. Knowing when and where a period belongs is very important to the sense of your sentences.

One of the most flexible punctuation marks is a comma; correct usage greatly impacts the readability of text. A comma might separate elements of a list, connect independent clauses using a conjunction, or set off introductory elements. But more often than not, commas aren’t used correctly. This either confuses or changes the intended meaning.

List: I bought apples, oranges, and bananas.

Introductory element: After the movie, we went to dinner.

Joining clauses: She wanted to go to the park, but it started raining.

Another critical use of commas is in non-essential clauses. These are phrases that offer information, but you can omit them without altering the basic meaning of a sentence.

Incorrect: My brother who lives in New York is visiting.

Correct: My brother, who lives in New York, is visiting.

Correct use of commas can make your writing more exact and clear to follow, thus avoiding misunderstandings.

The colon introduces lists, quotations, explanations, or examples. It indicates that what’s written before it is explained in greater detail by what follows. You should always precede a colon with an independent sentence.

List: You’ll need to bring the following items: a tent, sleeping bag, and flashlight.

Quotation: She said it best: “Practice makes perfect.”

You can also place colons after salutations in formal letters, for example “Dear Sir/Madam:”. In titles, they can separate a main title from a subtitle, for example, “Punctuation Rules: A Comprehensive Guide.” In every respect, it would denote that the sequence of what proceeds from it is related to or is a direct result of a previous statement.

Semicolon (;)

The semicolon is a mighty, if misunderstood, punctuation mark. It joins two very closely related independent clauses. It suggests that they could stand alone as sentences, but are also more closely connected in meaning than a period would suggest. In other words, it’s a mark that signals a pause longer than a comma but shorter than a period.

Incorrect: She loves reading, she spends hours in the library.

Correct: She loves reading; she spends hours in the library.

You can also use semicolons in complex lists where the items themselves have commas. This helps avoid confusion.

We visited Los Angeles, California; Portland, Oregon; and Seattle, Washington.

Question Mark (?)

The question mark is very simple in principle: you should use it at the end of a direct question. However, you shouldn’t use it after any sort of indirect questions or those statements that imply a question.

Direct question: Are you coming to the party?

Indirect question: I wonder if he is coming to the party.