The Elements of Thought

How we think….

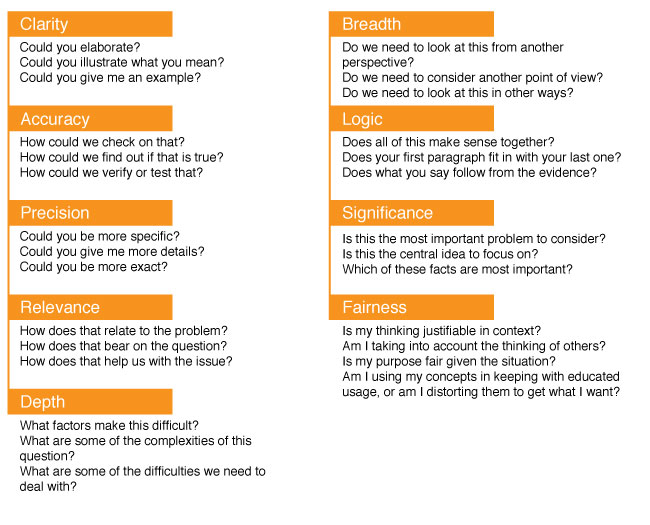

The Intellectual Standards

We all have a system to break down how we understand things, how the world looks to us, how we make sense of the world. The ways we think are called the Elements of Thought .

But once we have thought about something, how do we know if we’re right? How do we know if our thinking is any good?

Unfortunately, most of the time we don’t think well. We tend to favor decisions and ideas that favor us, put our own group over other groups. We are…ego-centric and socio-centric. So, we need to force ourselves to look at things the way they truly are. So, to assess the quality of our thinking, we use the Intellectual Standards .

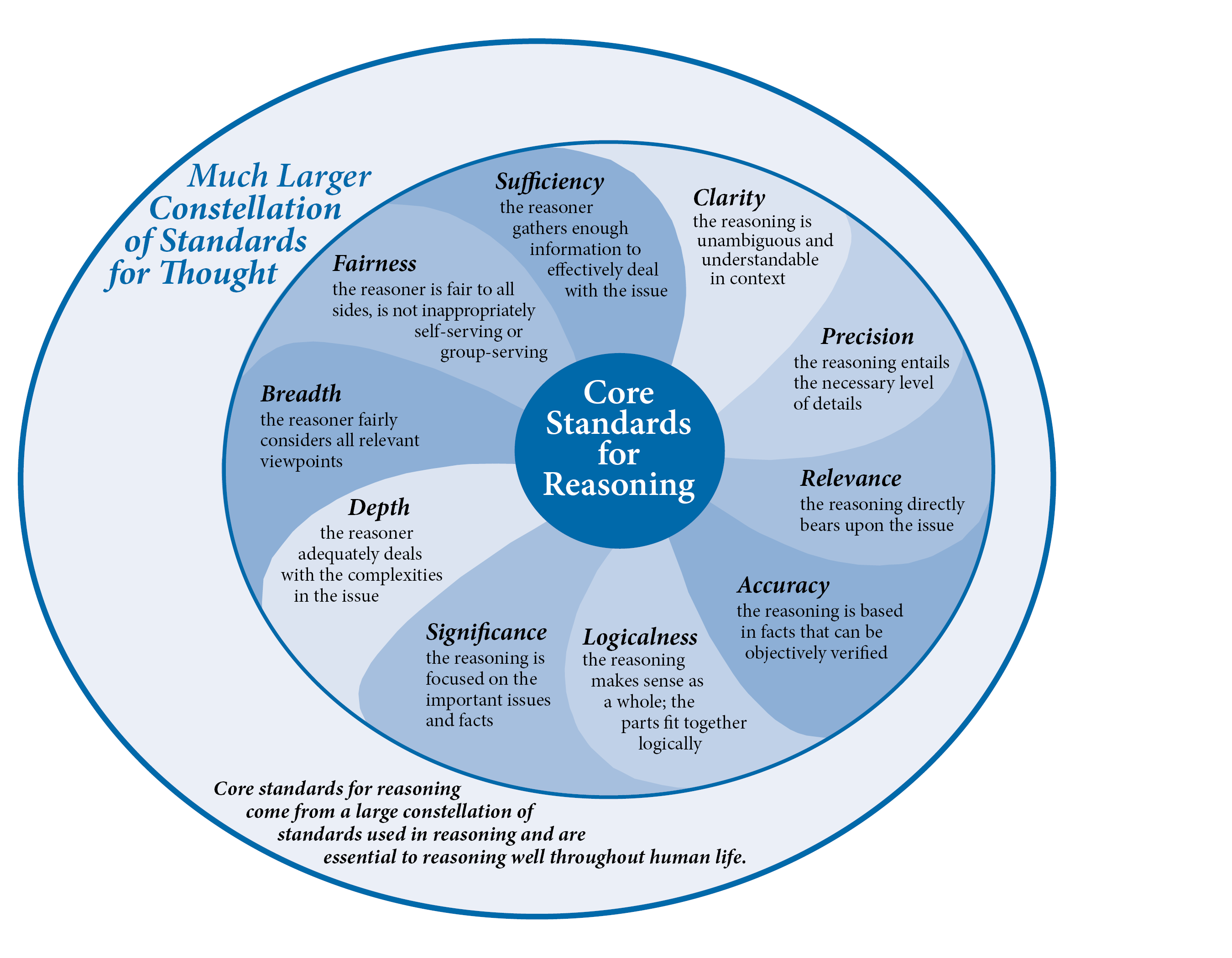

There are nine Intellectual Standards we use to assess thinking: Clarity , Accuracy , Precision , Relevance , Depth , Breadth , Logic , Significance , and Fairness . Let’s check them out one-by-one.

Clarity forces the thinking to be explained well so that it is easy to understand. When thinking is easy to follow, it has Clarity.

Accuracy makes sure that all information is correct and free from error. If the thinking is reliable, then it has Accuracy.

Precision goes one step further than Accuracy. It demands that the words and data used are exact. If no more details could be added, then it has Precision.

Relevance means that everything included is important, that each part makes a difference. If something is focused on what needs to be said, there is Relevance.

Depth makes the argument thorough. It forces us to explore the complexities. If an argument includes all the nuances necessary to make the point, it has Depth.

Breadth demands that additional viewpoints are taken into account. Are all perspectives considered? When all sides of an argument are discussed, then we find Breadth.

Logical means that an argument is reasonable, the thinking is consistent and the conclusions follow from the evidence. When something makes sense step-by-step, then it is Logical.

Significance compels us to include the most important ideas. We don’t want to leave out crucial facts that would help to make a point. When everything that is essential is included, then we find Significance.

Fairness means that the argument is balanced and free from bias. It pushes us to be impartial and evenhanded toward other positions. When an argument is objective, there is Fairness.

There are more Intellectual Standards, but if you use these nine to assess thinking, then you’re on your way to thinking like a pro.

Share this:

3 thoughts on “ the intellectual standards ”.

Pingback: Los 7 estándares universales del pensamiento – Inteligencia artificial 7 semestre

Pingback: What We're Reading and Watching: July 2017 - Center for Critical Thinking

Pingback: Capella University Susan Career Adjustment Goals Paper | Scholarly Script

Comments are closed.

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- Manage subscriptions

1 Introduction to Critical Thinking

I. what is c ritical t hinking [1].

Critical thinking is the ability to think clearly and rationally about what to do or what to believe. It includes the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking. Someone with critical thinking skills is able to do the following:

- Understand the logical connections between ideas.

- Identify, construct, and evaluate arguments.

- Detect inconsistencies and common mistakes in reasoning.

- Solve problems systematically.

- Identify the relevance and importance of ideas.

- Reflect on the justification of one’s own beliefs and values.

Critical thinking is not simply a matter of accumulating information. A person with a good memory and who knows a lot of facts is not necessarily good at critical thinking. Critical thinkers are able to deduce consequences from what they know, make use of information to solve problems, and to seek relevant sources of information to inform themselves.

Critical thinking should not be confused with being argumentative or being critical of other people. Although critical thinking skills can be used in exposing fallacies and bad reasoning, critical thinking can also play an important role in cooperative reasoning and constructive tasks. Critical thinking can help us acquire knowledge, improve our theories, and strengthen arguments. We can also use critical thinking to enhance work processes and improve social institutions.

Some people believe that critical thinking hinders creativity because critical thinking requires following the rules of logic and rationality, whereas creativity might require breaking those rules. This is a misconception. Critical thinking is quite compatible with thinking “out-of-the-box,” challenging consensus views, and pursuing less popular approaches. If anything, critical thinking is an essential part of creativity because we need critical thinking to evaluate and improve our creative ideas.

II. The I mportance of C ritical T hinking

Critical thinking is a domain-general thinking skill. The ability to think clearly and rationally is important whatever we choose to do. If you work in education, research, finance, management or the legal profession, then critical thinking is obviously important. But critical thinking skills are not restricted to a particular subject area. Being able to think well and solve problems systematically is an asset for any career.

Critical thinking is very important in the new knowledge economy. The global knowledge economy is driven by information and technology. One has to be able to deal with changes quickly and effectively. The new economy places increasing demands on flexible intellectual skills, and the ability to analyze information and integrate diverse sources of knowledge in solving problems. Good critical thinking promotes such thinking skills, and is very important in the fast-changing workplace.

Critical thinking enhances language and presentation skills. Thinking clearly and systematically can improve the way we express our ideas. In learning how to analyze the logical structure of texts, critical thinking also improves comprehension abilities.

Critical thinking promotes creativity. To come up with a creative solution to a problem involves not just having new ideas. It must also be the case that the new ideas being generated are useful and relevant to the task at hand. Critical thinking plays a crucial role in evaluating new ideas, selecting the best ones and modifying them if necessary.

Critical thinking is crucial for self-reflection. In order to live a meaningful life and to structure our lives accordingly, we need to justify and reflect on our values and decisions. Critical thinking provides the tools for this process of self-evaluation.

Good critical thinking is the foundation of science and democracy. Science requires the critical use of reason in experimentation and theory confirmation. The proper functioning of a liberal democracy requires citizens who can think critically about social issues to inform their judgments about proper governance and to overcome biases and prejudice.

Critical thinking is a metacognitive skill . What this means is that it is a higher-level cognitive skill that involves thinking about thinking. We have to be aware of the good principles of reasoning, and be reflective about our own reasoning. In addition, we often need to make a conscious effort to improve ourselves, avoid biases, and maintain objectivity. This is notoriously hard to do. We are all able to think but to think well often requires a long period of training. The mastery of critical thinking is similar to the mastery of many other skills. There are three important components: theory, practice, and attitude.

III. Improv ing O ur T hinking S kills

If we want to think correctly, we need to follow the correct rules of reasoning. Knowledge of theory includes knowledge of these rules. These are the basic principles of critical thinking, such as the laws of logic, and the methods of scientific reasoning, etc.

Also, it would be useful to know something about what not to do if we want to reason correctly. This means we should have some basic knowledge of the mistakes that people make. First, this requires some knowledge of typical fallacies. Second, psychologists have discovered persistent biases and limitations in human reasoning. An awareness of these empirical findings will alert us to potential problems.

However, merely knowing the principles that distinguish good and bad reasoning is not enough. We might study in the classroom about how to swim, and learn about the basic theory, such as the fact that one should not breathe underwater. But unless we can apply such theoretical knowledge through constant practice, we might not actually be able to swim.

Similarly, to be good at critical thinking skills it is necessary to internalize the theoretical principles so that we can actually apply them in daily life. There are at least two ways to do this. One is to perform lots of quality exercises. These exercises don’t just include practicing in the classroom or receiving tutorials; they also include engaging in discussions and debates with other people in our daily lives, where the principles of critical thinking can be applied. The second method is to think more deeply about the principles that we have acquired. In the human mind, memory and understanding are acquired through making connections between ideas.

Good critical thinking skills require more than just knowledge and practice. Persistent practice can bring about improvements only if one has the right kind of motivation and attitude. The following attitudes are not uncommon, but they are obstacles to critical thinking:

- I prefer being given the correct answers rather than figuring them out myself.

- I don’t like to think a lot about my decisions as I rely only on gut feelings.

- I don’t usually review the mistakes I have made.

- I don’t like to be criticized.

To improve our thinking we have to recognize the importance of reflecting on the reasons for belief and action. We should also be willing to engage in debate, break old habits, and deal with linguistic complexities and abstract concepts.

The California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory is a psychological test that is used to measure whether people are disposed to think critically. It measures the seven different thinking habits listed below, and it is useful to ask ourselves to what extent they describe the way we think:

- Truth-Seeking—Do you try to understand how things really are? Are you interested in finding out the truth?

- Open-Mindedness—How receptive are you to new ideas, even when you do not intuitively agree with them? Do you give new concepts a fair hearing?

- Analyticity—Do you try to understand the reasons behind things? Do you act impulsively or do you evaluate the pros and cons of your decisions?

- Systematicity—Are you systematic in your thinking? Do you break down a complex problem into parts?

- Confidence in Reasoning—Do you always defer to other people? How confident are you in your own judgment? Do you have reasons for your confidence? Do you have a way to evaluate your own thinking?

- Inquisitiveness—Are you curious about unfamiliar topics and resolving complicated problems? Will you chase down an answer until you find it?

- Maturity of Judgment—Do you jump to conclusions? Do you try to see things from different perspectives? Do you take other people’s experiences into account?

Finally, as mentioned earlier, psychologists have discovered over the years that human reasoning can be easily affected by a variety of cognitive biases. For example, people tend to be over-confident of their abilities and focus too much on evidence that supports their pre-existing opinions. We should be alert to these biases in our attitudes towards our own thinking.

IV. Defining Critical Thinking

There are many different definitions of critical thinking. Here we list some of the well-known ones. You might notice that they all emphasize the importance of clarity and rationality. Here we will look at some well-known definitions in chronological order.

1) Many people trace the importance of critical thinking in education to the early twentieth-century American philosopher John Dewey. But Dewey did not make very extensive use of the term “critical thinking.” Instead, in his book How We Think (1910), he argued for the importance of what he called “reflective thinking”:

…[when] the ground or basis for a belief is deliberately sought and its adequacy to support the belief examined. This process is called reflective thought; it alone is truly educative in value…

Active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends, constitutes reflective thought.

There is however one passage from How We Think where Dewey explicitly uses the term “critical thinking”:

The essence of critical thinking is suspended judgment; and the essence of this suspense is inquiry to determine the nature of the problem before proceeding to attempts at its solution. This, more than any other thing, transforms mere inference into tested inference, suggested conclusions into proof.

2) The Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (1980) is a well-known psychological test of critical thinking ability. The authors of this test define critical thinking as:

…a composite of attitudes, knowledge and skills. This composite includes: (1) attitudes of inquiry that involve an ability to recognize the existence of problems and an acceptance of the general need for evidence in support of what is asserted to be true; (2) knowledge of the nature of valid inferences, abstractions, and generalizations in which the weight or accuracy of different kinds of evidence are logically determined; and (3) skills in employing and applying the above attitudes and knowledge.

3) A very well-known and influential definition of critical thinking comes from philosopher and professor Robert Ennis in his work “A Taxonomy of Critical Thinking Dispositions and Abilities” (1987):

Critical thinking is reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.

4) The following definition comes from a statement written in 1987 by the philosophers Michael Scriven and Richard Paul for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking (link), an organization promoting critical thinking in the US:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue, assumptions, concepts, empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions, implications and consequences, objections from alternative viewpoints, and frame of reference.

The following excerpt from Peter A. Facione’s “Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction” (1990) is quoted from a report written for the American Philosophical Association:

We understand critical thinking to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, CT is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one’s personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, CT is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fairminded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus, educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing CT skills with nurturing those dispositions which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society.

V. Two F eatures of C ritical T hinking

A. how not what .

Critical thinking is concerned not with what you believe, but rather how or why you believe it. Most classes, such as those on biology or chemistry, teach you what to believe about a subject matter. In contrast, critical thinking is not particularly interested in what the world is, in fact, like. Rather, critical thinking will teach you how to form beliefs and how to think. It is interested in the type of reasoning you use when you form your beliefs, and concerns itself with whether you have good reasons to believe what you believe. Therefore, this class isn’t a class on the psychology of reasoning, which brings us to the second important feature of critical thinking.

B. Ought N ot Is ( or Normative N ot Descriptive )

There is a difference between normative and descriptive theories. Descriptive theories, such as those provided by physics, provide a picture of how the world factually behaves and operates. In contrast, normative theories, such as those provided by ethics or political philosophy, provide a picture of how the world should be. Rather than ask question such as why something is the way it is, normative theories ask how something should be. In this course, we will be interested in normative theories that govern our thinking and reasoning. Therefore, we will not be interested in how we actually reason, but rather focus on how we ought to reason.

In the introduction to this course we considered a selection task with cards that must be flipped in order to check the validity of a rule. We noted that many people fail to identify all the cards required to check the rule. This is how people do in fact reason (descriptive). We then noted that you must flip over two cards. This is how people ought to reason (normative).

- Section I-IV are taken from http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ and are in use under the creative commons license. Some modifications have been made to the original content. ↵

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Standards of Critical Thinking

Thinking towards truth..

Posted June 11, 2012 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Cognition?

- Take our Mental Processing Test

- Find a therapist near me

What is critical thinking? According to my favorite critical thinking text , it is disciplined thinking that is governed by clear intellectual standards.

This involves identifying and analyzing arguments and truth claims, discovering and overcoming prejudices and biases, developing your own reasons and arguments in favor of what you believe, considering objections to your beliefs, and making rational choices about what to do based on your beliefs.

Clarity is an important standard of critical thought. Clarity of communication is one aspect of this. We must be clear in how we communicate our thoughts, beliefs, and reasons for those beliefs.

Careful attention to language is essential here. For example, when we talk about morality , one person may have in mind the conventional morality of a particular community, while another may be thinking of certain transcultural standards of morality. Defining our terms can greatly aid us in the quest for clarity.

Clarity of thought is important as well; this means that we clearly understand what we believe, and why we believe it.

Precision involves working hard at getting the issue under consideration before our minds in a particular way. One way to do this is to ask the following questions: What is the problem at issue? What are the possible answers? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each answer?

Accuracy is unquestionably essential to critical thinking. In order to get at or closer to the truth, critical thinkers seek accurate and adequate information. They want the facts because they need the right information before they can move forward and analyze it.

Relevance means that the information and ideas discussed must be logically relevant to the issue being discussed. Many pundits and politicians are great at distracting us away from this.

Consistency is a key aspect of critical thinking. Our beliefs should be consistent. We shouldn’t hold beliefs that are contradictory. If we find that we do hold contradictory beliefs, then one or both of those beliefs are false. For example, I would likely contradict myself if I believed both that " Racism is always immoral" and "Morality is entirely relative." This is a logical inconsistency.

There is another form of inconsistency, called practical inconsistency, which involves saying you believe one thing while doing another. For example, if I say that I believe my family is more important than my work, but I tend to sacrifice their interests for the sake of my work, then I am being practically inconsistent.

The last three standards are logical correctness, completeness, and fairness. Logical correctness means that one is engaging in correct reasoning from what we believe in a given instance to the conclusions that follow from those beliefs. Completeness means that we engage in deep and thorough thinking and evaluation, avoiding shallow and superficial thought and criticism. Fairness involves seeking to be open-minded, impartial, and free of biases and preconceptions that distort our thinking.

Like any skill or set of skills, getting better at critical thinking requires practice. Anyone wanting to grow in this area might think through these standards and apply them to an editorial in the newspaper or on the web, a blog post, or even their own beliefs. Doing so can be a useful and often meaningful exercise.

Michael W. Austin, Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Video Series

- Information Literacy

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking defined, assistive technologies, critical thinking & information literacy.

- Meta-cognitive Awareness Inventory

Research Help

Library Terms

Multilingual Glossary for Today’s Library Users - Definitions

Universal design for learning.

- Reference Information

- Find books and E-books

- Find articles

- Statistical Sources

- Evaluate Information

- Cite sources

- Writing Style Manuals

- Fake News and Information Literacy

Critical Thinking can be thought of in terms of

- Reasonable thinking

- Reflective thinking

- Evaluative thinking

- Mindful thought

- Intellectually-disciplined thought

Critical Thinking as Defined by the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, 1987

A statement by Michael Scriven & Richard Paul, presented at the 8th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform, Summer 1987.

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.

- Critically Thinking

You’ve done some great work so far, thumbs up! Now we are going to look at information access and evaluation, another important skill for your research skills toolbox.

Information has many facets, and it’s important to understand how these components contribute to writing your research paper. sometimes, you are looking for snippets of information that capture your thoughts or ideas. but when you access and evaluate resources you need to think deeply and critically about the resource you want to use to support your argument in your writing assignment., information resources come in a variety of formats, such as books, e-books, scholarly and peer reviewed articles, articles from trade magazines, newspapers, and, depending on your topic, streaming videos; audio files or blog posts . but one thing they have in common is that they have identifiable attributes for you to consider. these attributes help you to determine if the resource is relevant to your topic., so what are these facets.

- The date the source was published or created.

- If the article is not been published recently, you must ask yourself why you want to use it as a source. Is the material dated? Or does it offer some insight that warrants being cited (i.e., is it a classic in the field? a neglected contribution to the literature?)

- Is this part of a larger source?

- For example, is it a chapter in a book or e-book? Article in a journal or newspaper?

- What about that source tells you this?

- Article in a newspaper or trade magazine

- Book Review

- Scholarly and peer reviewed article

There are a number of questions you should ask of these different formats. If your source is from a periodical, is that source considered credible, for example, a major newspaper such as the New York Times or Washington Post ? If your source is from a trade magazine, does it offer a skewed perspective, based on its position in industry or ideology? Does it show bias? If from a website, where does the site get its facts? Does it cite scholarly articles, clearly indicate its sources? Have other credible sources questioned its objectivity?

- What do you know about the author ? ( Where they work , what they do , other sources they’ve created, their relationship to the subject or topic?

- What else might you find out about the author/s?

Once you identify these aspects, you need to ask some critical questions to evaluate your sources.

- What is your source about? What is the author’s argument? If you can’t tell from the information that’s been provided, context or clues within the source will help you make a reasonable guess.

- What would you say about the language used in the source? Is it difficult to understand or fairly simple?

- Who do you think is the audience for your source? Why?

- What about the visuals in your source? For example, are the images used to support the message , provide evidence , or give you information about the author ? Are there images that distract ?

- Remember that the PGCC Library Databases have been vetted by Teaching and Library faculty to ensure that the content meets the curriculum plan of the college. If you are using articles from a PGCC Library Database, you will never have to pay to access the article.

Now we are going to look at an article obtained from a library database about BLACKLIVESMATTER and see if we can consider access and evaluation of the article based on the criteria above. This article is from PsycArticles, a PROQUEST database.

The article title is : “Participation in Black Lives Matter and deferred action for childhood arrivals: Modern activism among Black and Latino college students”

What do we know about the author/authors?

If you click on the Hyperlink for the Author’s name, you’ll find other articles that have been published by the author.

The article is published in the Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. If you click on the name of the Journal you will find out information about the journal.

The 9.3 (Sep 2016): 203-215; indicates that it is Volume 9; Issue 3 dated September 2016: pages 203-215.

How can we tell that this is a scholarly and peer reviewed article? What components of this article indicate that this is a research paper?

If you look at these components, you will find that they meet the test of a scholarly and peer reviewed research article. The article uses technical terminology, and it follows a standard research format—it has an abstract, a review of the literature, methodology, results, conclusion, and references.

So, after looking at this article, you have concluded that this is a peer-reviewed research article. Next you’ll need to evaluate the source. You’ll want to consider what this source is about . From reading the abstract above, can you consider through what lens or perspective might this author be writing?

First, look at the language in the article. Is it clear, concise and easily readable ? Based on the language, who do you think the AUDIENCE is for this source? Students? Researchers? Is it for the average reader or for someone who might want to write a research paper?

Now let’s look at the article’s presentation of data. You will find four tables that report on the study: Study Variables by Race; BLM and DACA involvement by Race, Ethnicity and Gender; Average level of political activism; Predicting BLM and DACA Involvement . Do these tables help you understand the impact of study better? Why or Why not?

Now let’s return to the language of the article and see if we can tell if this article pro-BLACKLIVESMATTERS or not? How can you tell? Are there clues in how the abstract is written that help you to infer the author’s position ? For example, does this statement from the article give you a perspective as to the direction of the article, “ Two 21st century sociopolitical movements that have emerged to counteract racial/ethnic marginalization in the United States are BLM and advocacy for DACA legislation. BLM activists seek legislative changes to decrease the negative (and often life threatening) effects of discriminatory practices in our justice and political systems ”.

Your analysis of the author’s attitude involves you interpreting the article’s tone—in the preceding sentence, the author does not use language to undermine BLM—it doesn’t say “claims to” or “reportedly” or “seemingly” in describing the impact of the movement. It does not use charged political rhetoric to suggest BLM’s worsens marginalization or to undercut its assertions about the level of discrimination.

Then you have judge the usefulness of the source:

If you are writing about the influence of the BLACKLIVESMATTER movement and activism , is this article good for your paper ? Why or Why not?

Let’s look at the abstract, where the article claims that “ Political activism is one way racially/ethnically marginalized youth can combat institutional discrimination and seek legislative change toward equality and justice. In the current study, we examine participation in #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) and advocacy for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) as political activism popular among youth.”

First, determine whether the article may provide evidence to support your argument. This involves paying close attention to the article’s thesis and to its supporting evidence. What do you think the article is saying overall ? What is the takeaway ? How does it relate to your own argument? This involves considerable reflection on your part.

For example, does this statement argue your topic? “Finally, scholars suggest that experiencing racial/ethnic discrimination likely contributes to greater participation in political activism as a mechanism to mitigate future instances of discrimination (Hope & Jagers, 2014; Hope & Spencer, in press)”. That really depends on what your thesis is. You may find that this conclusion is too broad, and you may then refine your own position. In an engagement with scholarly articles, you may be forced to think more clearly about your own position.

Secondly , you must determine how much research has been done on this topic. Where does this article fit in the overall field of scholarship? You can’t simply assume that one article has vanquished all others from the field of intellectual battle. In this analysis, you must examine the article’s limitations: What wasn’t included or what was missing from the article? Have you seen other articles that challenge the author’s perspective? Do you want—for example—to see evidence of political activism actually leading to change? Or is the article’s claim too weak? After all, the sentence above simply says it’s one way to seek change, not the most effective.

Remember, research is a process. You want to find the best scholarly articles not only to support your own claims, but to challenge your assumptions and help refine your conclusions. As we’ve seen, that involves determining whether an article appears in a respectable scholarly journal—as citing weak and unprofessional sources destroys your credibility and offers no real challenge. Instead, you should exercise your analytical and argumentative skills on the best scholarship available.

Accessibility Masterlist

This MasterList, edited by Gregg Vanderheiden Ph.D., is designed to serve as a resource for researchers, developers, students, and others interested in understanding or developing products that incorporate one or more of these features.

Each feature or approach is then listed below along with applicable disabilities to each feature are marked with the following icons:

- B - Blindness (For our purposes, blindness is defined as no or very low vision - such that text cannot be read at any magnification)

- LV - Low Vision

- CLL - Cognitive, Language, and Learning Disabilities (including low literacy)

- PHY - Physical Disabilities

- D/HOH - Deaf and Hard of Hearing

- American Sign Language Dictionary

Search and compare thousands of words and phrases in American Sign Language (ASL). The largest collection of free video signs online.

Braille Translator

Brailletranslator.org is a simple way to convert text to braille notation. This supports nearly all Grade Two braille contractions.

- Braille Translator

Voyant Tools (Corpus Analysis)

Voyant Tools is an open-source, web-based application for performing text analysis. It supports scholarly reading and interpretation of texts or corpus, particularly by scholars in the digital humanities, but also by students and the general public. It can be used to analyze online texts or ones uploaded by users. (Source: Wikipedia )

- Voyant Tools (Corpus Analysis)

Critical Thinking & Information Literacy - Parallel Processes

- Realize the task

- Explore, formulate, question, make connections

- Search and find

- Collect and organize

- Analyze, evaluate, interpret

- Apply understanding

- Communicate, present, share

Did you know that you can request a RESEARCH CONSULTATION appointment? This is a one-on-one assistance with your research related need.

Whether it's in-person, e-mail , phone, chat or text to 301-637-4609, you can ask a librarian for research help.

It's important to understand library terms in order for you to do your research. If you have questions about the terminology used in the tutorial you can check this Glossary of Library Terms.

Abstract : A summary or brief description of the content of another long work. An abstract is often provided along with the citation to a work.

Annotated bibliography: a bibliography in which a brief explanatory or evaluate note is added to each reference or citation. An annotation can be helpful to the researcher in evaluating whether the source is relevant to a given topic or line of inquiry.

Archives : 1. A space which houses historical or public records. 2. The historical or public records themselves, which are generally non-circulating materials such as collections of personal papers, rare books, Ephemera, etc.

Article : A brief work—generally between 1 and 35 pages in length—on a topic. Often published as part of a journal, magazine, or newspaper.

Author : The person(s) or organization(s) that wrote or compiled a document. Looking for information under its author's name is one option in searching.

Bibliography : A list containing citations to the resources used in writing a research paper or other document. See also Reference.

Book : A relatively lengthy work, often on a single topic. May be in print or electronic.

Boolean operator : A word—such as AND, OR, or NOT—that commands a computer to combine search terms. Helps to narrow (AND, NOT) or broaden (OR) searches.

Call number : A group of letters and/or numbers that identifies a specific item in a library and provides a way for organizing library holdings. Three major types of call numbers are Dewey Decimal, Library of Congress, and Superintendent of Documents.

Catalog : A database (either online or on paper cards) listing and describing the books, journals, government documents, audiovisual and other materials held by a library. Various search terms allow you to look for items in the catalog.

Check-out : To borrow an item from a library for a fixed period of time in order to read, listen to, or view it. Check-out periods vary by library. Items are checked out at the circulation desk.

Circulation : The place in the library, often a desk, where you check out, renew, and return library materials. You may also place a hold, report an item missing from the shelves, or pay late fees or fines there.

Citation : A reference to a book, magazine or journal article, or other work containing all the information necessary to identify and locate that work. A citation to a book includes its author's name, title, publisher and place of publication, and date of publication.

Controlled vocabulary : Standardized terms used in searching a specific database.

Course reserve : Select books, articles, videotapes, or other materials that instructors want students to read or view for a particular course. These materials are usually kept in one area of the library and circulate for only a short period of time. See also Electronic reserve.

Descriptor : A word that describes the subject of an article or book; used in many computer databases.

Dissertation : An extended written treatment of a subject (like a book) submitted by a graduate student as a requirement for a doctorate.

DOI : Acronym for Digital Object Identifier. It is a unique alphanumeric string assigned by the publisher to a digital object.

E-book (or Electronic book) : An electronic version of a book that can be read on a computer or mobile device.

Editor : A person or group responsible for compiling the writings of others into a single information source. Looking for information under the editor's name is one option in searching.

Electronic reserve (or E-reserve) : An electronic version of a course reserve that is read on a computer display screen. See also Course reserve.

Encyclopedia : A work containing information on all branches of knowledge or treating comprehensively a particular branch of knowledge (such as history or chemistry). Often has entries or articles arranged alphabetically.

Hold : A request to have an item saved (put aside) to be picked up later. Holds can generally, be placed on any regularly circulating library material in-person or online.

Holdings : The materials owned by a library.

Index : 1. A list of names or topics—usually found at the end of a publication—that directs you to the pages where those names or topics are discussed within the publication. 2. A printed or electronic publication that provides references to periodical articles or books by their subject, author, or other search terms.

Interlibrary services/loan : A service that allows you to borrow materials from other libraries through your own library. See also Document delivery.

Journal : A publication, issued on a regular basis, which contains scholarly research published as articles, papers, research reports, or technical reports. See also Periodical.

Limits/limiters : Options used in searching that restrict your results to only information resources meeting certain other, non-subject-related, criteria. Limiting options vary by database, but common options include limiting results to materials available full-text in the database, to scholarly publications, to materials written in a particular language, to materials available in a particular location, or to materials published at a specific time.

Magazine : A publication, issued on a regular basis, containing popular articles, written and illustrated in a less technical manner than the articles found in a journal.

Microform : A reduced sized photographic reproduction of printed information on reel to reel film (microfilm) or film cards (microfiche) or opaque pages that can be read with a microform reader/printer.

Newspaper : A publication containing information about varied topics that are pertinent to general information, a geographic area, or a specific subject matter (i.e. business, culture, education). Often published daily.

Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC) : A computerized database that can be searched in various ways— such as by keyword, author, title, subject, or call number— to find out what resources a library owns. OPAC’s will supply listings of the title, call number, author, location, and description of any items matching one's search. Also referred to as “library catalog ” or “online catalog.”

PDF : A file format developed by Adobe Acrobat® that allows files to be transmitted from one computer to another while retaining their original appearance both on-screen and when printed. An acronym for Portable Document Format.

Peer-reviewed journal : Peer review is a process by which editors have experts in a field review books or articles submitted for publication by the experts’ peers. Peer review helps to ensure the quality of an information source. A peer-reviewed journal is also called a refereed journal or scholarly journal.

Periodical : An information source published in multiple parts at regular intervals (daily, weekly, monthly, biannually). Journals, magazines, and newspapers are all periodicals. See also Serial.

Plagiarism : Using the words or ideas of others without acknowledging the original source.

Primary source : An original record of events, such as a diary, a newspaper article, a public record, or scientific documentation.

Print : The written symbols of a language as portrayed on paper. Information sources may be either print or electronic.

Publisher : An entity or company that produces and issues books, journals, newspapers, or other publications.

Recall : A request for the return of library material before the due date.

Refereed journal: See Peer-reviewed journal.

Reference : 1. A service that helps people find needed information. 2. Sometimes "reference" refers to reference collections, such as encyclopedias, indexes, handbooks, directories, etc. 3. A citation to a work is also known as a reference.

Renewal : An extension of the loan period for library materials.

Reserve : 1. A service providing special, often short-term, access to course-related materials (book or article readings, lecture notes, sample tests) or to other materials (CD-ROMs, audio-visual materials, current newspapers or magazines). 2. Also the physical location—often a service desk or room—within a library where materials on reserve are kept. Materials can also be made available electronically. See also Course reserve, Electronic reserve.

Scholarly journal : See Peer-reviewed journal.

Search statement/Search Query : Words entered into the search box of a database or search engine when looking for information. Words relating to an information source's author, editor, title, subject heading or keyword serve as search terms. Search terms can be combined by using Boolean operators and can also be used with limits/limiters.

Secondary sources : Materials such as books and journal articles that analyze primary sources. Secondary sources usually provide evaluation or interpretation of data or evidence found in original research or documents such as historical manuscripts or memoirs.

Serial : Publications such as journals, magazines, and newspapers that are generally published multiple times per year, month, or week. Serials usually have number volumes and issues.

Stacks : Shelves in the library where materials—typically books—are stored. Books in the stacks are normally arranged by call number. May be referred to as “book stacks.”

Style manual : An information source providing guidelines for people who are writing research papers. A style manual outlines specific formats for arranging research papers and citing the sources that are used in writing the paper.

Subject heading : Descriptions of an information source’s content assigned to make finding information easier. See also Controlled vocabulary, Descriptors.

Title : The name of a book, article, or other information sources. Upload: To transfer information from a computer system or a personal computer to another computer system or a larger computer system.

Virtual reference: A service allowing library users to ask questions through email, text message, or live-chat as opposed to coming to the reference desk at the library and asking a question in person. Also referred to as “online reference” or “e-reference.”

Multilingual Glossary for Today’s Library Users

If English is not your first language, then this resource will help you navigate the definitions of library terms in the following languages: English, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, French, Spanish, Arabic, and Vietnamese.

- Multilingual Glossary for Today’s Library Users - Definitions The Glossary provides terms an ESL speaker might find useful and a listing of the terms that are most likely to be used in a library.

- Multilingual Glossary for Today’s Library Users - Language Table Here is a list of definitions that you can also find the translation in English, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, French, Spanish, Arabic, and Vietnamese.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

- UDL Core Apps

- Universal Design for Learning Research Guide

- << Previous: Information Literacy

- Next: Reference Information >>

- Last Updated: Jul 20, 2023 1:57 PM

- URL: https://pgcc.libguides.com/c.php?g=631064

Designorate

Design thinking, innovation, user experience and healthcare design

How to Apply Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

The critical thinking framework provides an efficient method for designers, design students, and researchers to evaluate arguments and ideas through rational reasoning. As a result, we eliminate biases, distractions, and similar factors that negatively affect our decisions and judgments. We can use critical thinking to escape our current mindsets to reach innovative outcomes.

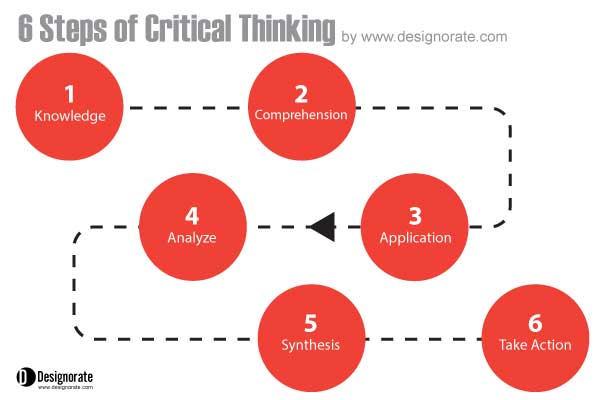

The critical thinking framework is based on three main stages; observe the problem to build rational knowledge, ask questions to analyze and evaluate data, and find answers to the questions that can be formulated into a solution. These stages are translated into six steps ( 6 Steps for Effective Critical Thinking ):

- Knowledge – Define the main topic that needs to be covered

- Comprehension – Understand the issue through researching the topic

- Application – Analyze the data and link between the collected data

- Analysis – Solve the problem, or the issue investigated

- Synthesis – Turn the solution into an implementable action plan

- Evaluate – test and evaluate the solution

Based on the above, the essential part of the critical thinking framework represents building clear, coherent reasoning for the problem, which will help ensure that the topic is addressed in the critical thinking stages.

Related articles:

- Guide for Critical Thinking for Designers

- 6 Steps for Effective Critical Thinking

- The Six Hats of Critical Thinking and How to Use Them

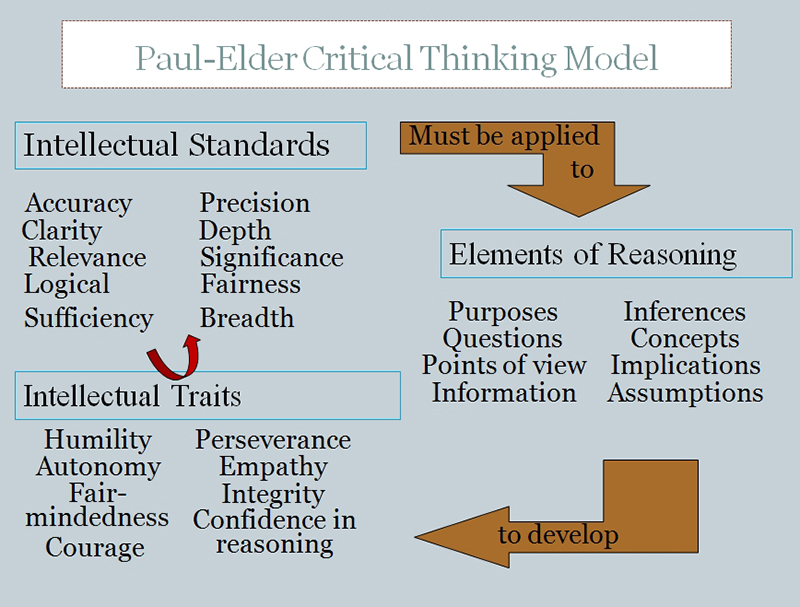

The Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

In 2001, Paul and Elder introduced the critical thinking framework that helps students to master their thinking dimensions through identifying the thinking parts and evaluating the usage of these parts. The framework aims to improve our reasoning by identifying its different elements through three main elements; elements of reasoning, intellectual standards, and intellectual traits.

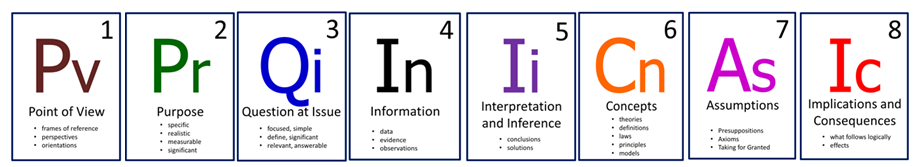

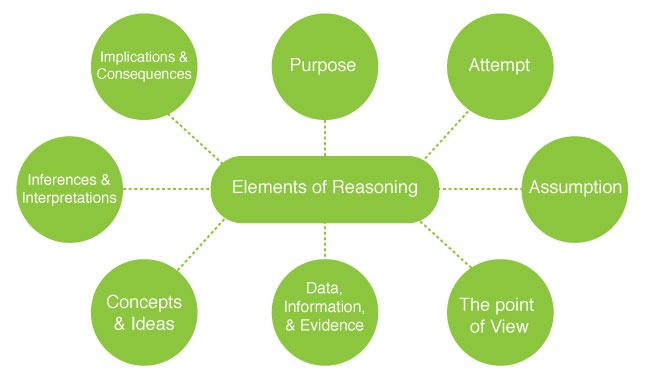

Elements of Reasoning

Whenever we have a topic or argument to discuss, we tend to use a number of thinking models to understand the topic at hand (i.e. Using Inductive Reasoning in User Experience Research ). These parts are known as the elements of thought or reasoning. Our minds may use these parts over the course to think about the idea:

Purpose – This part of our thinking includes defining the topic’s goal or objective. For example, the goal may involve solving a problem or achieving a target. Attempt – This part includes the attempts that previously addressed the topic or attempts to solve a problem. Assumption – Before solving a problem, we don’t have much information about the topic. Therefore, we build assumptions to act as the base of our research about the issue. We usually start with inductive inferences. Then, we use the research data to validate these assumptions. For example, we assume that all apples are red and start to research the different types of trees to know that some apples are green and some are red. The point of View includes the personal perspective we take while thinking about the topic. For instance, we can think about the product from the consumer perspective rather than the business perspective. Data, Information, and Evidence – Here, we cover the data and information related to the topic. Also, here we have all the supportive evidence. Concepts and Ideas – We have all the principles, models, and theories related to the topic. For example, this part may include all the views associated with applying a specific solution. Inferences and Interpretations – The last part includes the concluded solutions based on the previous factors. The conclusion may consist of the suggested solution to a specific problem. Implications and Consequences – All the reasons must lead to consequences resulting from implementing the results of the reasoning process.

Intellectual Standards

The above reasoning parts require a good quality benchmark to achieve its goals and ensure the accuracy of results. The intellectual standards are nine factors that can evaluate the equality of the reason parts mentioned above. These standards include clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, significance, and fairness. Based on these standards, we can ask ourselves questions to evaluate the parts above. The below table provides examples of the questions that we can ask to assess the equality of our ideas.

The below two videos include Dr. Richard Paul’s lectures about the standards of thought and critical thinking.

Intellectual Traits

As a result of the application for the above reasoning parts and validating them using intellectual standards, The below characteristics are expected to evolve, known as the intellectual traits:

Intellectual Humility

This trait develops one’s ability to perceive the known limitation and the circumstances that may cause biases and self-deceptively. It depends on recognizing that one claims what one’s knows.

Intellectual Courage

Courage represents developing a consciousness to address ideas fairly regardless of its point of View or our negative emotions about it. Also, it helps us develop our ability to evaluate ideas regardless of our presumptions and perceptions about them.

Intellectual Empathy

Empathy is related to developing the ability to put ourselves in others’ shoes to understand them. Also, it forms how we can see the parts of reasoning of the others, such as the viewpoints, assumptions, and ideas.

Intellectual Integrity

This part is related to developing the ability to integrate with other intellectual reasoning and avoid the confusion of our reasoning. Unlike empathy, integrity focuses on the ability to others’ reasoning for the topic and integrate with it.

Intellectual Perseverance

Perseverance develops the need to have a proper insight about the situation regardless of the barriers faced against it, such as difficulties, frustration, and obstacles. This helps us to build rational reasoning despite what is standing against it.

Confidence in Reason

By applying the reasoning parts and encouraging people to develop their reasons, they build confidence in their reason and rational thinking.

Fair-mindedness

This trait develops the ability to start with a fair look at all the reasoning and traits of all the viewpoints, putting aside one’s feelings, raises, and interests.

The critical thinking framework can help us address topics and problems more rationally, contributing to building a clear understanding of topics. This can be achieved through having clear reasoning about the addressed topics. The Paul-Eder Critical Thinking Framework was introduced in 2001 to improve the critical thinking process by understanding the parts of the reasons and providing a method to evaluate it. You can learn more about the framework through the Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking published by the Foundation of Critical Thinking.

Understanding the thinking elements and how to evaluate our reasoning related to each part, we can improve our thoughts through time. Additionally, seven main advantages (intellectual traits) can be achieved.

Paul-Elder’s critical thinking framework identifies the thinking parts through eight elements of reasoning (purpose, attempt, assumption, point of view, data, concepts and ideas, and inference and interpretation). Nine benchmarks are used to evaluate the application of the above elements (clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, significance and fairness).

What are the critical thinking framework elements?

Define the main topic that needs to be covered

Understand the issue through researching the topic

Analyze the data and link between the collected data

Solve the problem, or the issue investigated

Turn the solution into an implementable action plan

Test and evaluate the solution

The application of the Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework is based on identifying eight elements of reasoning: Purpose, Attempt, Assumption, Point of View, Data and Evidence, Concepts and Ideas, Inferences and Interpretations and Implications and Consequences.

Wait, Join my Newsletters!

As always, I try to come to you with design ideas, tips, and tools for design and creative thinking. Subscribe to my newsletters to receive new updated design tools and tips!

Dr Rafiq Elmansy

As an academic and author, I've had the privilege of shaping the design landscape. I teach design at the University of Leeds and am the Programme Leader for the MA Design, focusing on design thinking, design for health, and behavioural design. I've developed and taught several innovative programmes at Wrexham Glyndwr University, Northumbria University, and The American University in Cairo. I'm also a published book author and the proud founder of Designorate.com, a platform that has been instrumental in fostering design innovation. My expertise in design has been recognised by prestigious organizations. I'm a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA), the Design Research Society (FDRS), and an Adobe Education Leader. Over the course of 20 years, I've had the privilege of working with esteemed clients such as the UN, World Bank, Adobe, and Schneider, contributing to their design strategies. For more than 12 years, I collaborated closely with the Adobe team, playing a key role in the development of many Adobe applications.

You May Also Like

Critical Thinking as a Catalyst of Change in Design

The Role of Storytelling in the Design Process

SCAMPER Technique Examples and Applications

30+ Distance Learning Tools And Advices for Design Educators

Creative Thinking: Inspired Lessons from Leonardo Da Vinci’s

The Six Systems Thinking Steps to Solve Complex Problems

3 thoughts on “ how to apply paul-elder critical thinking framework ”.

it was really helpfull

Thank you for this helpful distillation, as well as including the videos.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sign me up for the newsletter!

- Head of School

- Lower School Principal

- Middle School Principal

- Upper School Principal

- Arts Director

- Athletic Director

- College Counseling Director

- Libraries Director

- Parent Association President

- Horizons Director

- Culture & Community Director

Breadth vs. depth: What’s the best way to learn?

An inch deep and a mile wide? Or a mile deep and an inch wide?

One of the ongoing debates in education revolves around the question of breadth versus depth. Is it better to expose students to many concepts (breadth) or to foster a deeper exploration into fewer topics (depth)? Not surprisingly, consensus has not been reached, but certainly the trend in the past decade is towards deeper learning.

In recent years the Mastery Transcript Consortium (MTC), about which I have written in previous articles , has received widespread attention and has helped direct conversation towards mastery-based or competency-based curriculum. This curricular movement emphasizes depth of learning such that students reach certain competency levels as established by their teachers. Those who espouse this model argue that students develop better long-term learning strategies and critical thinking if they are allowed to go deeper into fewer total topics, especially when given some freedom to pursue areas of interest and passion. When educators strive for depth over breadth, the argument goes, they increase both student agency (the means by which students control their own learning) and engagement.

One of my go-to sources for the latest in educational research is Edutopia, the vast website sponsored by George Lucas of Star Wars fame. In a December article , one of Edutopia’s contributors, Emily Kaplan, touted the advantages of mastery in the context of student-directed learning: “Ultimately, the shift [in education ] . . . is less about specific practices and more about a shift in priorities: away from immediate outcomes and toward a messier, unfinished, and deeper form of understanding.”

Deep learning at CA

In Colorado Academy’s Upper School , you will see more evidence in all classrooms and all disciplines of “messier” learning than you might have seen in past years. More often now, teachers and students team up to learn content areas in a more open-ended, exploratory way. In this model, the process and the journey are just as important as the end results. As a result, we see more collaboration (students working in pairs or teams) and more self-reflection, as students ask themselves why and how they are doing what they are doing.

But we all know mastery or even competency are tricky goals to achieve. What exactly do we mean by mastery, and how do we know a student has achieved it? Setting those benchmarks clearly and providing consistent, meaningful feedback are essential. That takes extensive work on the teacher’s part on the front end, as well as during the process, and typically involves the development of detailed learning rubrics.

So the tension between depth and breadth, as well as the corollary debate of teacher-directed instruction versus student-directed learning, remains. I would like to think Colorado Academy continues to find that “sweet spot” in the middle, being responsive to both ends of that spectrum.

We know that exposure to many topics is important, especially in the early grades of high school, when students’ brains are still developing. In Grades 9 and 10, a learner’s capacity for depth, higher order thinking, and a love of process over product are still very much works in progress. In many cases, they also have not solidified their foundational skills well enough to go in-depth into very many areas. Still, that doesn’t mean we should rely on direct instruction entirely or that we shouldn’t help students move in the direction of competency-based learning through greater student-led exploration.

How it works in my classes

A simple example from my own practice helps illustrate this idea. I currently teach the Ninth Grade English course called Coming of Age in the World. One of the books we read in that course is Persepolis , Marjane’s Satrapi illustrated memoir about growing up during the Iranian revolution.

In teaching this work, I have to provide students a good deal of historical context for them to make sense of it. Equipped with that foundational background and the common experience of reading the book, students can then be set loose to explore a research topic of their choice that relates to the events described in the book. By then, I am actually more concerned with how they follow the process of writing a short research paper and the skills they build up in doing so than I am with the content of their papers. I am trying to strike that balance between content and skill-building, between depth and breadth.

Lessons like this one capture the best of both sides of the spectrum and encourage students’ ability to think critically and self-direct within limited parameters. I see this happening across disciplines in the Upper School labs and classrooms. Colorado Academy will continue to engage in the best educational practices we know, while always giving a certain amount of supported, individualized freedom to all our students.

| | |

- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul and Elder, 2001). The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought

According to Paul and Elder (1997), there are two essential dimensions of thinking that students need to master in order to learn how to upgrade their thinking. They need to be able to identify the "parts" of their thinking, and they need to be able to assess their use of these parts of thinking.

Elements of Thought (reasoning)

The "parts" or elements of thinking are as follows:

- All reasoning has a purpose

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem

- All reasoning is based on assumptions

- All reasoning is done from some point of view

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences

Universal Intellectual Standards

The intellectual standards that are to these elements are used to determine the quality of reasoning. Good critical thinking requires having a command of these standards. According to Paul and Elder (1997 ,2006), the ultimate goal is for the standards of reasoning to become infused in all thinking so as to become the guide to better and better reasoning. The intellectual standards include:

Intellectual Traits

Consistent application of the standards of thinking to the elements of thinking result in the development of intellectual traits of:

- Intellectual Humility

- Intellectual Courage

- Intellectual Empathy

- Intellectual Autonomy

- Intellectual Integrity

- Intellectual Perseverance

- Confidence in Reason

- Fair-mindedness

Characteristics of a Well-Cultivated Critical Thinker

Habitual utilization of the intellectual traits produce a well-cultivated critical thinker who is able to:

- Raise vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gather and assess relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2010). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

Published on May 30, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Critical thinking is the ability to effectively analyze information and form a judgment .

To think critically, you must be aware of your own biases and assumptions when encountering information, and apply consistent standards when evaluating sources .

Critical thinking skills help you to:

- Identify credible sources

- Evaluate and respond to arguments

- Assess alternative viewpoints

- Test hypotheses against relevant criteria

Table of contents

Why is critical thinking important, critical thinking examples, how to think critically, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about critical thinking.

Critical thinking is important for making judgments about sources of information and forming your own arguments. It emphasizes a rational, objective, and self-aware approach that can help you to identify credible sources and strengthen your conclusions.

Critical thinking is important in all disciplines and throughout all stages of the research process . The types of evidence used in the sciences and in the humanities may differ, but critical thinking skills are relevant to both.

In academic writing , critical thinking can help you to determine whether a source:

- Is free from research bias

- Provides evidence to support its research findings

- Considers alternative viewpoints

Outside of academia, critical thinking goes hand in hand with information literacy to help you form opinions rationally and engage independently and critically with popular media.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Critical thinking can help you to identify reliable sources of information that you can cite in your research paper . It can also guide your own research methods and inform your own arguments.

Outside of academia, critical thinking can help you to be aware of both your own and others’ biases and assumptions.

Academic examples

However, when you compare the findings of the study with other current research, you determine that the results seem improbable. You analyze the paper again, consulting the sources it cites.

You notice that the research was funded by the pharmaceutical company that created the treatment. Because of this, you view its results skeptically and determine that more independent research is necessary to confirm or refute them. Example: Poor critical thinking in an academic context You’re researching a paper on the impact wireless technology has had on developing countries that previously did not have large-scale communications infrastructure. You read an article that seems to confirm your hypothesis: the impact is mainly positive. Rather than evaluating the research methodology, you accept the findings uncritically.

Nonacademic examples

However, you decide to compare this review article with consumer reviews on a different site. You find that these reviews are not as positive. Some customers have had problems installing the alarm, and some have noted that it activates for no apparent reason.

You revisit the original review article. You notice that the words “sponsored content” appear in small print under the article title. Based on this, you conclude that the review is advertising and is therefore not an unbiased source. Example: Poor critical thinking in a nonacademic context You support a candidate in an upcoming election. You visit an online news site affiliated with their political party and read an article that criticizes their opponent. The article claims that the opponent is inexperienced in politics. You accept this without evidence, because it fits your preconceptions about the opponent.

There is no single way to think critically. How you engage with information will depend on the type of source you’re using and the information you need.

However, you can engage with sources in a systematic and critical way by asking certain questions when you encounter information. Like the CRAAP test , these questions focus on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

When encountering information, ask:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert in their field?

- What do they say? Is their argument clear? Can you summarize it?

- When did they say this? Is the source current?

- Where is the information published? Is it an academic article? Is it peer-reviewed ?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence? Does it rely on opinion, speculation, or appeals to emotion ? Do they address alternative arguments?

Critical thinking also involves being aware of your own biases, not only those of others. When you make an argument or draw your own conclusions, you can ask similar questions about your own writing:

- Am I only considering evidence that supports my preconceptions?

- Is my argument expressed clearly and backed up with credible sources?

- Would I be convinced by this argument coming from someone else?

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Critical thinking skills include the ability to:

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search, interpret, and recall information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing values, opinions, or beliefs. It refers to the ability to recollect information best when it amplifies what we already believe. Relatedly, we tend to forget information that contradicts our opinions.

Although selective recall is a component of confirmation bias, it should not be confused with recall bias.

On the other hand, recall bias refers to the differences in the ability between study participants to recall past events when self-reporting is used. This difference in accuracy or completeness of recollection is not related to beliefs or opinions. Rather, recall bias relates to other factors, such as the length of the recall period, age, and the characteristics of the disease under investigation.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/critical-thinking/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, student guide: information literacy | meaning & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Defining Critical Thinking

|

| ||

|

Foundation for Critical Thinking Press, 2008)

Teacher’s College, Columbia University, 1941) | ||

| | ||

COMMENTS

There are nine Intellectual Standards we use to assess thinking: Clarity, Accuracy, Precision, Relevance, Depth, Breadth, Logic, Significance, and Fairness. Let's check them out one-by-one. Clarity forces the thinking to be explained well so that it is easy to understand. When thinking is easy to follow, it has Clarity.

Critical Thinking as Defined by the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, 1987 ... accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue ...

Universal intellectual standards are standards which must be applied to thinking whenever one is interested in checking the quality of reasoning about a problem, issue, or situation. To think critically entails having command of these standards. To help students learn them, teachers should pose questions which probe student thinking; questions ...

lectual StandardsWe postulate that there are at least nine intellectual standards important to skilled reasoning. in everyday life. These are clarity, precision, accuracy, relevance, depth, breadth, logicalness, significa. ce, and fairness. It is unin-telligible to claim that any instance of reasoning is both sound and yet in violation o.