- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Join Our Team

Case Study – Thoroughgood Elementary

Thoroughgood Elementary

Designing a neighborhood school for the 21st century.

The new Thoroughgood Elementary School will enable students to learn, explore, discover, and play in an open and collaborative environment. The partnership between the architect’s team of designers and engineers, Virginia Beach City Public Schools administration and school board, faculty and staff, students, parents, and community members has promoted a 21st century school design supportive of non-traditional and diverse learning methods for students Pre-K through 5th grade.

This project replaces a sixty-two year old aging and over-crowded elementary school facility. The overall design is custom and tailored to reflect future forward educational instruction, contribute to the VBCPS system’s wide sustainability goals as a net zero ready facility. The new 91,913 SF school will initially house 725 students. The design features exposed elements of construction and energy efficiency as teaching tools to facilitate learning through demonstration; it redefines the ideas of traditional educational spaces to promote collaboration and learning everywhere and finally the design reveals the positive effects of identifying, respecting and integrating the site’s existing attributes and characteristics.

The new Thoroughgood Elementary School is deeply rooted in its community and is supportive of its core values and culture. These values are revealed in each design element beginning with how one approaches the site and experiences the entry, moves through the special shaped spaces in each area of the building, enjoys the natural light and air everywhere, and enjoys the natural textures and cheery colors. It is a bright, fresh and stimulating environment inside and out for learning and sparking young minds!

The two story wing houses Grades 2-3 on the first floor, Grades 4-5 on the second floor and is nestled into the forested area at the rear of the site. This building siting effect has a two-fold impact: one is external and the other internal.

- From the street view, the building never really presents a 2 story feel to the dominantly one story residential neighborhood aiding, in the appropriateness of scale to its surroundings.

- Internally, whether you are on the 1st or the 2nd floor, you always feel like you are in a treehouse. It is a super positive natural “green” effect where the outside feels like it is on the inside all the time.

All the classrooms in this area of the building are designed to be interchangeable with these 4 grade levels to accommodate the ebb and flow of age group demographics. This 2 story zone of the building is all classrooms and the same planning principles are the drivers organizing natural light and transparency from room to room, multi-tasking of spaces and shared classroom space for special learning activities. The accent colors on the floors and walls are themed after earth, wind, water and fire and enhance the feel of openness and vibrancy as you move through the corridors.

The upper level commons area features several unique spatial relationships. It looks down into the gym and is accessed by an open central stair or elevator. An extraordinary Maker Space Lab is open to and looks down into the 2 story learning commons volume and has direct access to a rooftop outdoor classroom which is partially decked and partially planted.

Creating a transparent environment enables students to feel more comfortable and less confined, encourages more communication between faculty and staff, and allows visibility for teachers to keep a close eye on their surroundings. The key to this design strategy was connectivity.

- Materiality, color + form guide your eye from room to room

- Natural light from all directions is a constant

- Portable furnishings offer infinite flexibility and are interchangeable amongst spaces

- Visibility to the outside is everywhere

- Writing surfaces for lessons and messaging occur throughout

- Art + music access the courtyard directly

The integration of nature and increased natural daylighting has been proven to enhance academic performance, decrease disciplinary issues, lower stress levels, encourage curiosity, and enhance occupants’ ability to focus on tasks.

Thoroughgood Elementary is one of the last true neighborhood schools in Hampton Roads. Respecting the goals of the stakeholders, the school naturally blends into the neighborhood and reflects the surrounding community’s culture. The entry was carefully designed to be distinct and welcoming to all who walk, bike, bus, or ride to school with a history walk as a nod to the historical namesake of Adam Thoroughgood, one of the founding colonists and community leaders of the 1600s.

Parent drop-off, faculty and visitor parking, and the bus loop are clearly delineated and separated with independent entry points for safe circulation.

A critical component to the design and construction of the new school was a tree preservation exercise to retain the beautiful century old canopies and forested area at the rear of the site. Designing the parent drop off and bus loop to weave through the trees was a part of this preservation plan. The new school was positioned and thoughtfully shaped to preserve and enhance the site’s character and capture the existing natural attributes. The final result is a new school which feels as if it were always there.

Learning activity areas on site:

- Outdoor reading areas

- Legacy garden

- Outdoor dining

- Storm water features

- Outdoor classroom

- Art gallery + music patio

- Multiple hard play courts + grass play fields

- Forested fitness area

Sustainability Moment

Rainwater Cisterns Collection and retention of rainwater in rainwater cisterns will be used as “greywater” for restroom fixtures. Annual collection of 500,000 gallons exceeds the 180,000 gallon annual usage that is estimated for the school.

Stormwater Retention 87,215 cubic feet of underground storage was added to mitigate any large rain events. These retention areas are used to keep water on site and slowly release water so the city’s systems are not overwhelmed. This retains 78% of stormwater runoff in a 100-year storm event.

The ability to closely interact and collaborate with all stakeholders throughout building design, interior programming, and site development allows us to learn about the inner workings of our client, just as it allows our clients to learn about the inner workings of design and architecture. We have found these collaborative and idea sharing moments within a project to be special and memorable for the entire team. It creates a bond of understanding, effectively creating a better design than we could not have imagined from a singular vision.

Additional Photos

John Lewis Elementary School: A Case Study

Washington, dc.

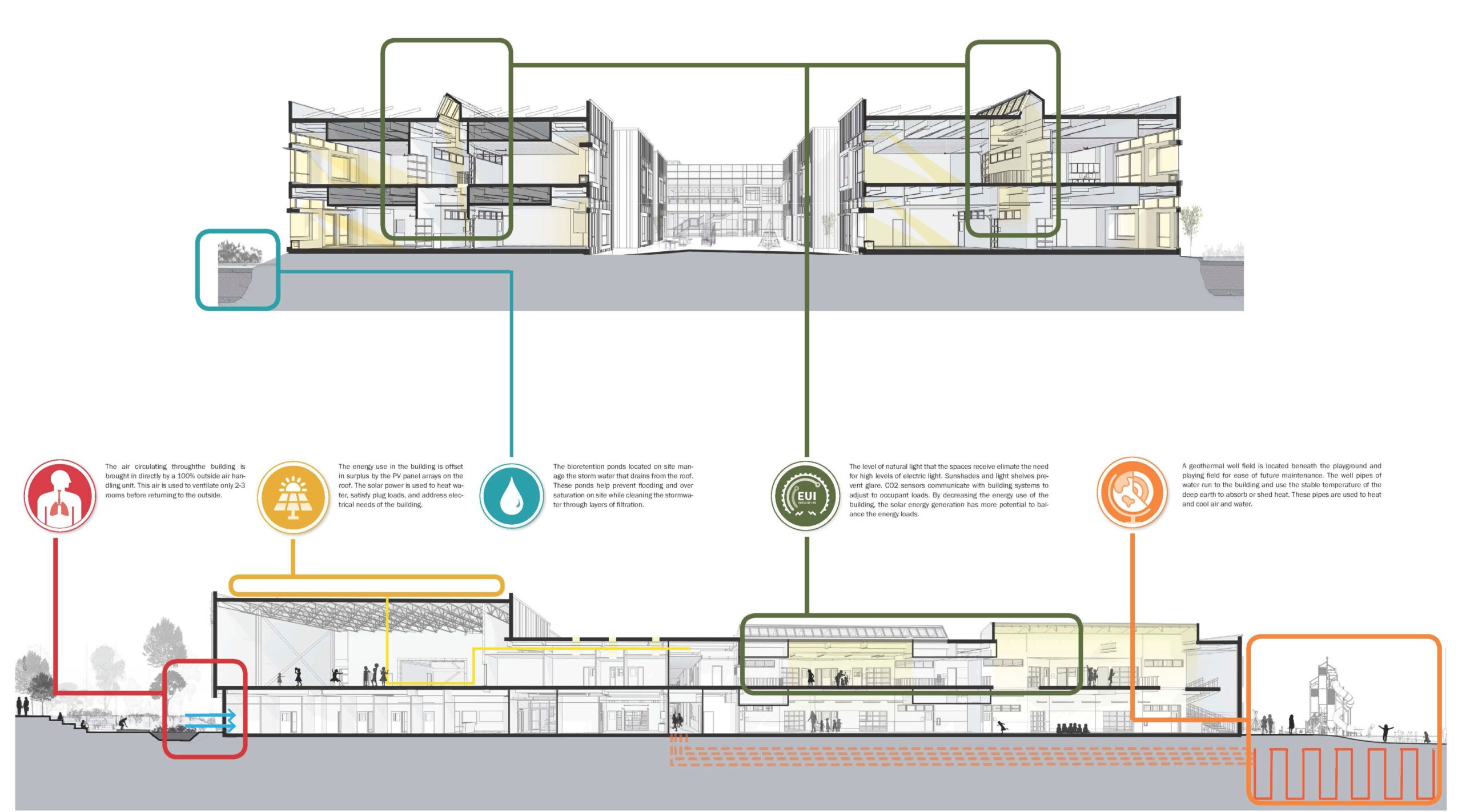

John Lewis Elementary School was designed to be the first school in the District of Columbia to achieve Net Zero Energy (NZE). The project is also the only school in the world to hold Platinum certifications in both LEED for Schools and WELL, setting a new benchmark. Through these approaches, the environment is designed to improve student and teacher performance, health, and well-being as well as reduce the building’s life-cycle costs.

Project Facts

Associate architect:, sustainability :.

- Video: John Lewis featured in "Exploring Your Health: Curing Our Classrooms," Spectrum News, Aug. 7, 2024

- Book Feature: "Creating the Regenerative School," 2024, Oro Editions

- "World's first K-12 school to achieve both LEED for Schools Platinum and WELL Platinum," Building Design + Construction, May 7, 2024

- "Schools in Virginia and Washington, D.C., blaze a trail for net zero energy," USGBC+, Fall 2023

- "From Net Zero to Net Positive in K-12 Schools," PE Insights, reposted in Building Design + Construction

- "Two new DC public schools model net zero education," Optimist Daily, Jan. 3, 2023

- John Lewis among "Five Buildings that Pushed Sustainable Design Forward" in 2022, Metropolis magazine,

- "This Hyper-Sustainable Elementary School Is the First of its Kind," Metropolis magazine, July 2022

- "Cause for Optimism Amid the Chaos," Collaborative of High Performance Schools, June 2022

- "How Public Schools Are Going Net Zero," Bloomberg CityLab

- Insights Post: "Zero for the Win: Perkins Eastman is setting the standard for net-zero energy in K-12 Education"

- "Learning Curve: A Tale of Two Schools in Pursuit of Net-Zero Energy," The Narrative, a Perkins Eastman magazine

- 2023 American Architecture Award, The Chicago Athenaeum

- 2023 Education-K-12 Winner: Planet Positive Awards, Metropolis magazine

- 2023 Popular Choice Award for Primary and High Schools, Architizer A+ Awards

- 2023 Winner: K-12 Education, IIDA MidAtlantic Premiere Design Awards

- 2023 AIANY Merit Award in Architecture

- 2022 Best of Year Award for Early Education, Interior Design magazine

- 2022 Sustainable & Resilient Design Award + Honorable Mention for Excellence in Design, AIA Baltimore

- 2022 Shortlist: Completed Buildings-Schools and Special Prize-Use of Color, World Architecture Festival

- 2022 Finalist - Spaces and Places in Innovation by Design Awards, Fast Company magazine

- 2022 Award of Excellence, AIA Northern Virginia Design Awards

- 2022 Award of Merit: K-12 Education, ENR Mid-Atlantic Regional Best Projects

- 2022 Silver Citation-Common Areas: The American School & University Educational Interiors Showcase Awards

- 2022 Award of Merit, AIA Education Facility Design Awards

- 2022 Award in Architecture, AIA|DC Chapter Design Awards

- 2022 Citation of Excellence, Learning by Design, Education Facilities Design Awards

The project’s design principles focus on civic presence, community connectivity, and—most importantly—student experience and wellness to create a high-performance, 21st-century learning environment.

The new building replaces an obsolete, brutalist, open-plan building, but it intentionally retained its best aspects—flexible space and ease of communication—while providing better adjacencies, daylighting, acoustics, security, and outdoor space to boost wellness and building performance, with the ultimate goal being improved educational outcomes.

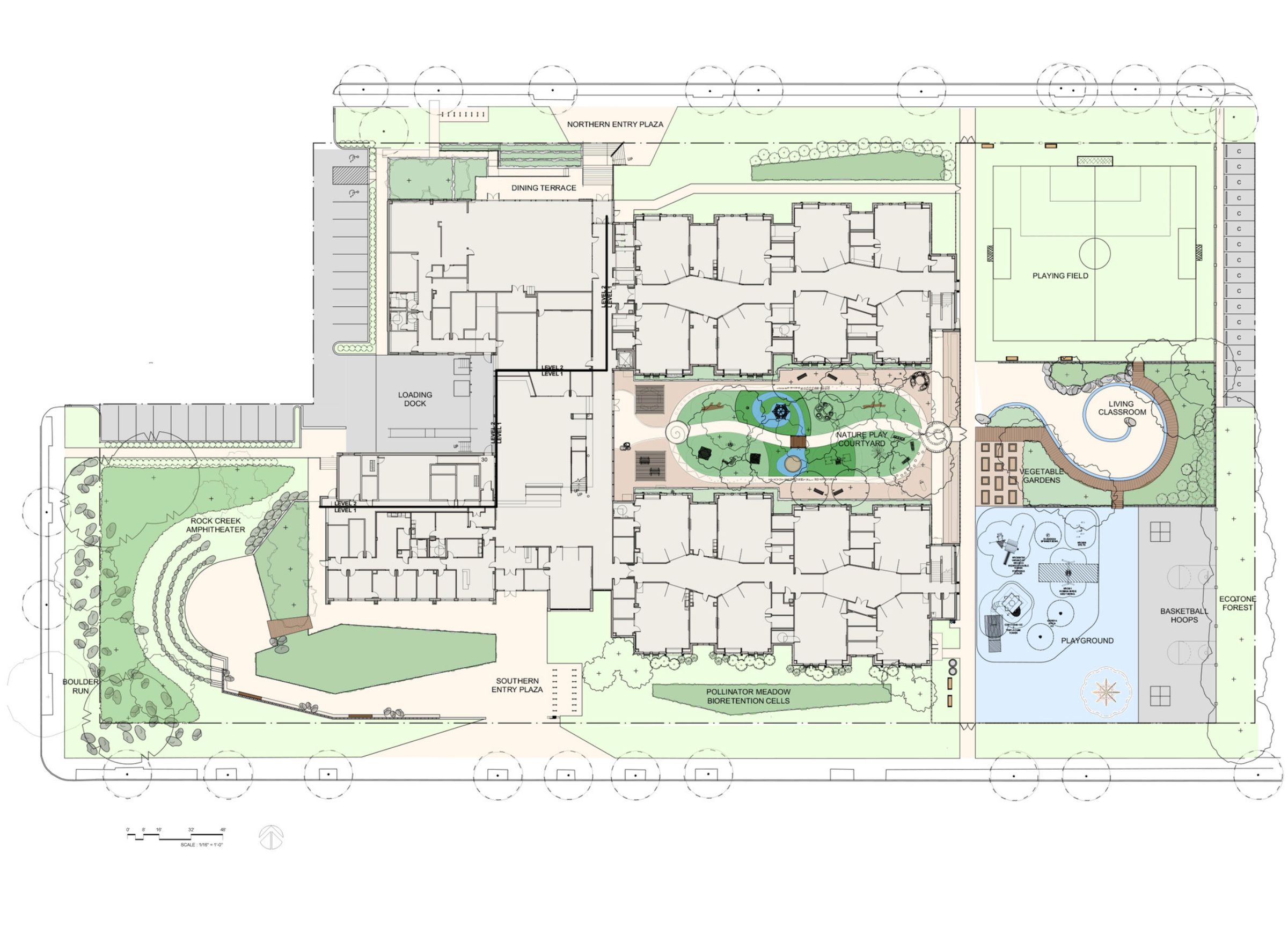

The building is surrounded by green space intended to delight and educate, including a amphitheater, pollinator meadow, vegetable gardens, a living classroom, and, of course, playgrounds.

The design emphasizes outdoor recreation and connections with the natural world, known to improve student health and academic achievement. The landscape design embeds natural systems with dynamic play and learning spaces to blur the walls of the classroom. A treasured place for the community, certain school amenities are accessible after-hours and on weekends.

The building reads inside and out as a series of intimate, child-scaled houses that foster collaboration and strong relationships inside and feel at home in the adjacent residential neighborhood.

The school’s “civic presence” features a large photovoltaic array to inspire the entire community to embrace sustainable design.

The school honors its proximity to Rock Creek Park, DC’s largest and most famous park, through interior and exterior textures, materials, and environmental quality. This inspiration is prominently displayed in the library, where discovery zones and reading nooks encourage learning, socialization, and engagement for all students, and a large-scale mural by a beloved local artist is the backdrop to a “treehouse” maker-space.

The cafeteria achieves a similar “treehouse” effect with green baffles in the ceiling and a wall of windows looking out to the leafy neighborhood.

A high-performance dashboard tracks the building’s energy consumption, showcases the building’s sustainability features, and links to the school’s curriculum to address topics such as social and environmental justice, climate change, and water conservation. Through this interactive, online dashboard, students and teachers can continuously discover how they interact with the building, and how the building and campus in turn influence and are influenced by the larger environment.

Pre- and post-occupancy evaluations of the school will complement the students’ ongoing exploration of performance. At its one-year anniversary of the school’s 2021 opening, our interviews for the post-occupancy evaluation will engage students, faculty, and administrators, as well as use on-site measurements to assess the success of the design.

The building is paired with Benjamin Banneker Academic High School , concurrently designed, which is also targeting NZE. The excess energy expected to be generated at John Lewis will help Banneker also achieve NZE. This multi-site approach broadens the perspective from a single building to the District’s entire inventory, encouraging an approach to radical citywide energy conservation.

Perkins Eastman DC (PEDC) was the prime architect on this project. Perkins Eastman’s expert sustainability and interior design teams collaborated with PEDC to create this exciting high performance learning environment.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Children’s learning for sustainability in social studies education: a case study from taiwanese elementary school.

- Minghsin University of Science and Technology, Hsinchu, Taiwan

Introduction: The primary aim of social studies education is to convey knowledge about cultural and social systems while fostering inquiry, participation, practice, reflection, and innovation. Social studies education plays a pivotal role in raising awareness about various ethnic groups, societies, localities, countries, and the world at large. Furthermore, it instills in students a sense of responsibility, leading them to embrace diversity, value human rights, and promote global sustainability. The current elementary social studies curriculum in Taiwan strongly aligns with these principles and is a vehicle for sustainable development in society.

Methods: The researcher used qualitative research methods and adopted a case study design to review the pedagogical design of the elementary social studies curriculum in Taiwan as a means of sustainability education and enriching children’s cultural learning in the context of sustainability. Children’s learning related to sustainability in an elementary school was investigated, and a social studies teaching design was developed. Finally, the developed teaching approach was implemented in a classroom setting.

Results and discussion: The study yielded the following findings: (1) The social studies curriculum development in Taiwan is connected to the pulse of life, a sense of care for local communities, and cultivation of local thinking. (2) This social studies curriculum adopts a child-centered and problem-oriented approach and integrates students’ interests and the local environment into the learning process. (3) It effectively enhances students’ sustainability-related competencies and skills. These findings offer valuable insights for teachers and can enable them to shape the direction of their social studies courses and cultivate children’s concept of sustainable development for their living environment.

1 Introduction

In Taiwan, the Curriculum Guidelines of the 12-Year Basic Education introduced herein adopt the vision of developing talent in every student—nurture by nature, and promoting life-long learning. In addition, the guidelines cater to the specific needs of all individuals, take into account the diverse cultures and differences between ethnic groups, and pay attention to socially vulnerable groups. The goal is to provide adequate education that elicits students’ enjoyment and confidence in learning. This facilitates raising students’ thirst for learning and courage to innovate creation, prompting them to fulfill their civic responsibilities and develop the wisdom for symbioses, and helping them engage in lifelong learning and develop excellent social adaptability. Accordingly, the vision of a more prosperous society with higher quality of life among individuals can be achieved ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ; Wang and Shih, 2022 ).

Seeking the “common good” in curriculum development can improve quality of life by promoting harmony and wellbeing. A curriculum based on seeking the common good can encourage students to care for others, participate in activities, protect for the natural environment, self-reflect, and develop sustainable practices for the society ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ). The goal of social studies education is to transmit knowledge of cultural and social systems and cultivate inquiry, participation, practice, reflection, and innovation. Social studies education promotes seeking the common good and instills social practices in students. Social studies education raises awareness of ethnic groups, societies, localities, countries, and the world and imbues students with a sense of responsibility, enabling them to recognize diversity, value human rights, and promote global sustainability ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ). Taiwan’s current elementary social studies curriculum promotes these aforementioned principles, all of which relate to sustainable development for our society.

This study conducted a comprehensive review of the elementary social studies curriculum in Taiwan, focusing on its role as a platform for sustainability education and its fostering of children’s cultural learning related to sustainability. The design of a cultural course centered on the town of Beigang was employed as an example; the aim of such a course is to ensure that children are proactive, engage with their environment, and ultimately seek the common good in society in Taiwan.

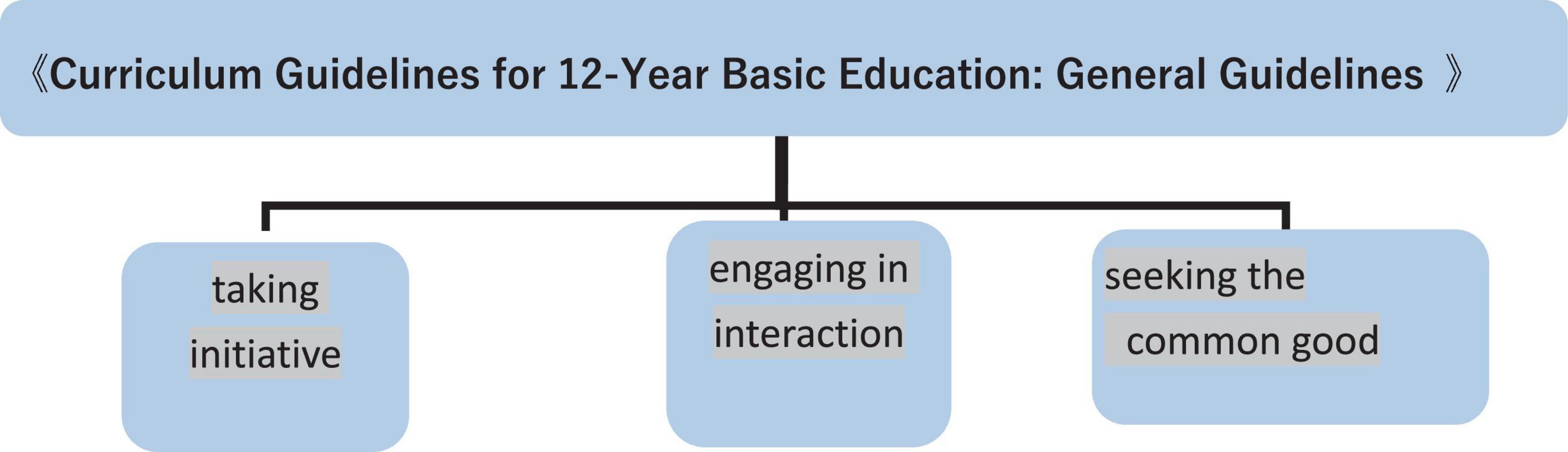

2 Theoretical perspective: the Curriculum Guidelines for 12-Year Basic Education: general guidelines

Taiwan’s 12-Year Basic Education was first implemented in August 2014, and the Ministry of Education announced the Curriculum Guidelines for 12-Year Basic Education: general guidelines in November 2014. The New Curriculum reflects the idea that the 12-year basic education curriculum guidelines should be based on the principle of holistic education, incorporating the ideas of “taking initiative,” “engaging in interaction,” and “seeking the common good” ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ; Shih et al., 2020 ; Wang and Shih, 2022 ). The idea of Curriculum Guidelines for 12-Year Basic Education: general guidelines is illustrated in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. The idea of Curriculum Guidelines for 12-Year Basic Education: general guidelines (source: Ministry of Education, 2014 ).

The Curriculum Guidelines of the 12-Year Basic Education was developed based on the spirit of holistic education, adopting the concepts of taking initiative, engaging in interaction, and seeking the common good to encourage students to become spontaneous and motivated learners. The curriculum also urges that schools be active in encouraging students to become motivated and passionate learners, leading students to appropriately develop the ability to interact with themselves, others, society, and nature. Schools should assist students in applying their learned knowledge, experiencing the meaning of life, and developing the willingness to become engaged in sustainable development of society, nature, and culture, facilitating the attainment of reciprocity and the common good in their society.

The theoretical perspective of this study is based on the concept of the Curriculum Guidelines for 12-Year Basic Education: general guidelines, including the concepts of taking initiative, engaging in interaction, and seeking the common good. The concepts of taking initiative, engaging in interaction, and seeking the common good for philosophical foundation of the curriculum in Taiwan. Based on the above-mentioned educational concepts, the cultural curriculum of Beigang is designed. Children can proactively protect Taiwan’s cultural and natural heritage and the cultural landscape that embodies the collective memory and history of the people on the land in the future. Seeking the common good for people in Taiwan.

2.1 The practice of the new curriculum is based on “core competency”

The practice of the New Curriculum is based on “core competency” as its main axis and consists of three dimensions: “autonomous action,” “communication and interaction,” and “social participation” ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ). In August 2019, the New Curriculum was formally implemented in Taiwan’s education system.

To implement the ideas and goals of 12-Year Basic Education, core competencies are used as the basis of curriculum development to ensure continuity between educational stages, bridging between domains, and integration between subjects. Core competencies are primarily adopted in the general domains and subjects of elementary school ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ).

The Meaning of “core competency” in social studies refers to the knowledge, ability, and attitude that students should possess for everyday life and challenges. When students face uncertain or complex situations, they can apply their subject knowledge through thinking and exploration, situational analysis, and questions or hypotheses. Ultimately, students can apply comprehensive learning strategies that are suitable for solving problems in their everyday life ( Ministry of Education, 2014 , 2018 ).

2.2 The goals in social studies

The curriculum outline for social studies (hereinafter, “Social Studies Outline”) is rooted in “maximizing students’ talent” and developing lifelong learning, as described by the Curriculum Guidelines of 12-Year Basic Education. According to the general outline, humanities and social sciences are core subjects that should be taught step by step. The curriculum mainly focuses on interests and inquiry regarding the three subjects of history, geography, and civics and society. The curriculum has the following goals ( Ministry of Education, 2014 , 2018 ):

Consider the diverse backgrounds and life experiences of students (e.g., culture, ethnicity, physical location, gender, and physical and mental characteristics) and promote career exploration and development to establish an independent learning space ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Consider the regional, ethnic, and school characteristics for curriculum development ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Establish vertical and horizontal integration within the studies through the following strategies ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ):

Have studies/subjects at each educational stage be guided by civic literacy and the themes of exploration and practical activities that provide space for collaboration on various subjects and issues in the social studies ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Prioritize real-world experience, accounting for the development of knowledge, positive attitudes, and practical skills for subjects at each learning stage ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Divide the learning content in a meaningful way that avoids unnecessary repetition because of the sequential development of learning stages and the need for complementary cooperation among subjects in the social studies ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Strengthen the vertical connection among elementary schools, junior high schools, and senior high schools and account for the horizontal connections between the characteristics of senior high schools, in accordance with the common principles of basic education ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

2.3 Course objectives of social studies

To teach the civic literacy that students require for their future and careers in the social studies curriculum. The goals of the curriculum are as follows ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ):

Develop an understanding of each subject and the qualities of self-discipline, autonomy, self-improvement, and self- realization ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Improve the quality of independent thinking, value judgments, rational decision-making, and innovation ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Develop the civic practices required in a democratic society, such as communication and social interaction, teamwork, problem- solving, and social participation ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Enhance the exploration and knowledge of history, geography, and civics, and other social disciplines ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Develop the ability to perform interdisciplinary analysis, speculate, integrate concepts, evaluate problems, and provide constructive criticism ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

Cultivate awareness of ethnic groups, societies, localities, countries, and the world and instill a sense of responsibility that includes the recognition of diversity, value of human rights, and concern for global sustainability ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

2.4 Key learning connotation of social studies

The key learning connotations include learning performance and learning content, both of which provide a framework for curriculum design, teaching material development, textbook review, and learning assessment. Learning performance and learning content can have various correspondences. At this learning stage, these aspects can be flexibly combined according to the characteristics of the social studies ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

2.4.1 Learning performance

Learning performance in the social studies is based on cognitive processes, affective attitudes, and practical skills. Learning performance comprises a common framework of understanding and speculation, attitudes and values, and practice and participation, which can be adjusted according to the educational stage and subject ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

2.4.2 Learning content

Learning content emphasizes the knowledge connotations of the studies/subject. The social studies curriculum outlines the basic learning content for each stage and subject and prioritizes vertical coherence between stages to avoid unnecessary repetition. Teachers, schools, local governments, and publishing houses can make adjustments after integrating learning content and performance according to their needs to promote effective teaching and adaptive learning ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

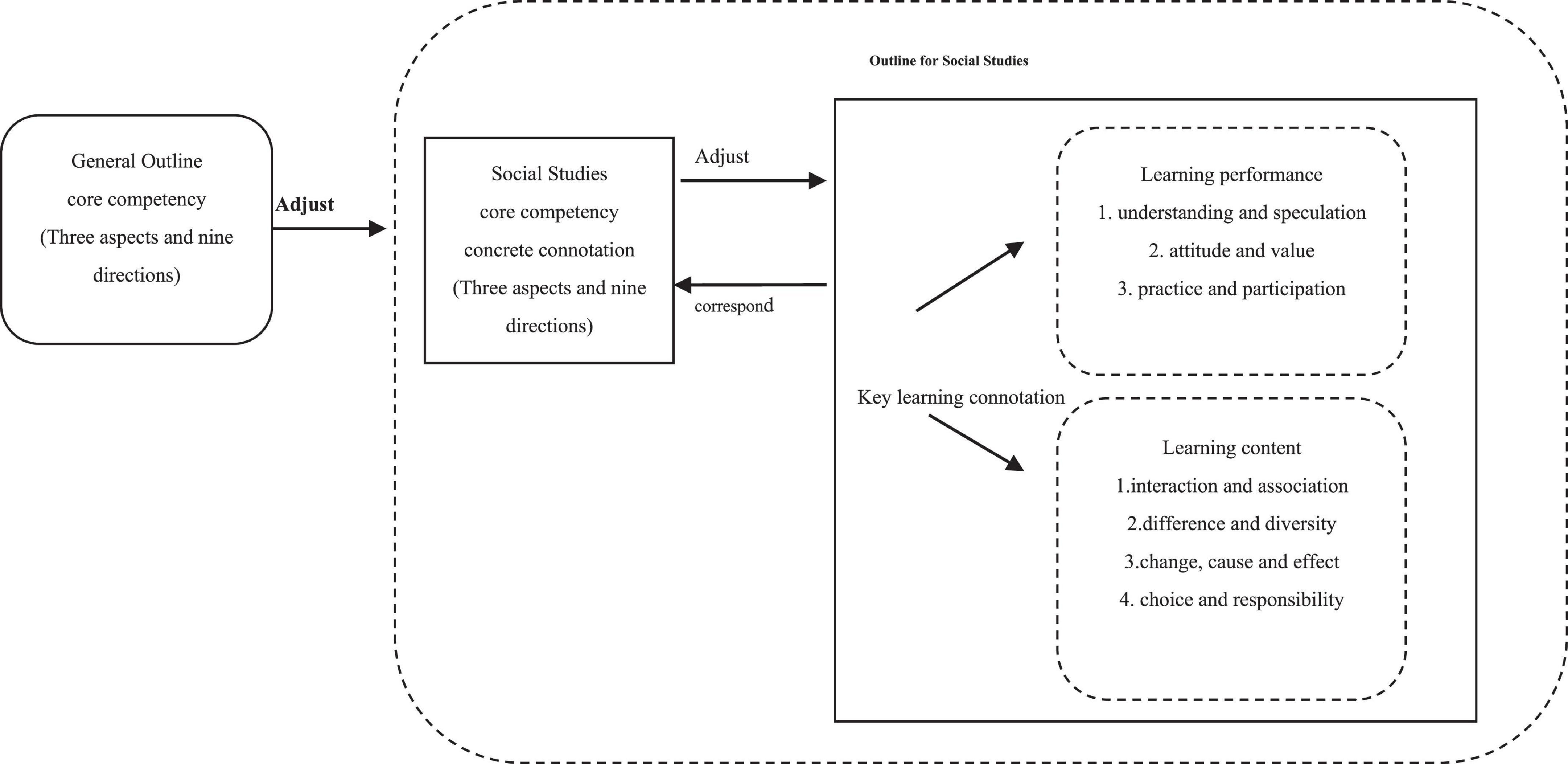

2.5 Relationship between the general outline and the social studies outline

The relationship between the general outline and social studies outline is presented in Figure 2 .

Figure 2. The relationship between the general outline and social studies outline (source: Ministry of Education, 2014 , 2018 ; Chan, 2020 ).

The general outline shares three aspects with the social studies outline. First, key learning connotations include both learning performance and learning content. Second, learning performance is based on understanding and speculation, attitudes and values, and practice and participation. Finally, the learning content is aimed at teaching students about interaction and association; difference and diversity; change, cause, and effect; and choice and responsibility ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ).

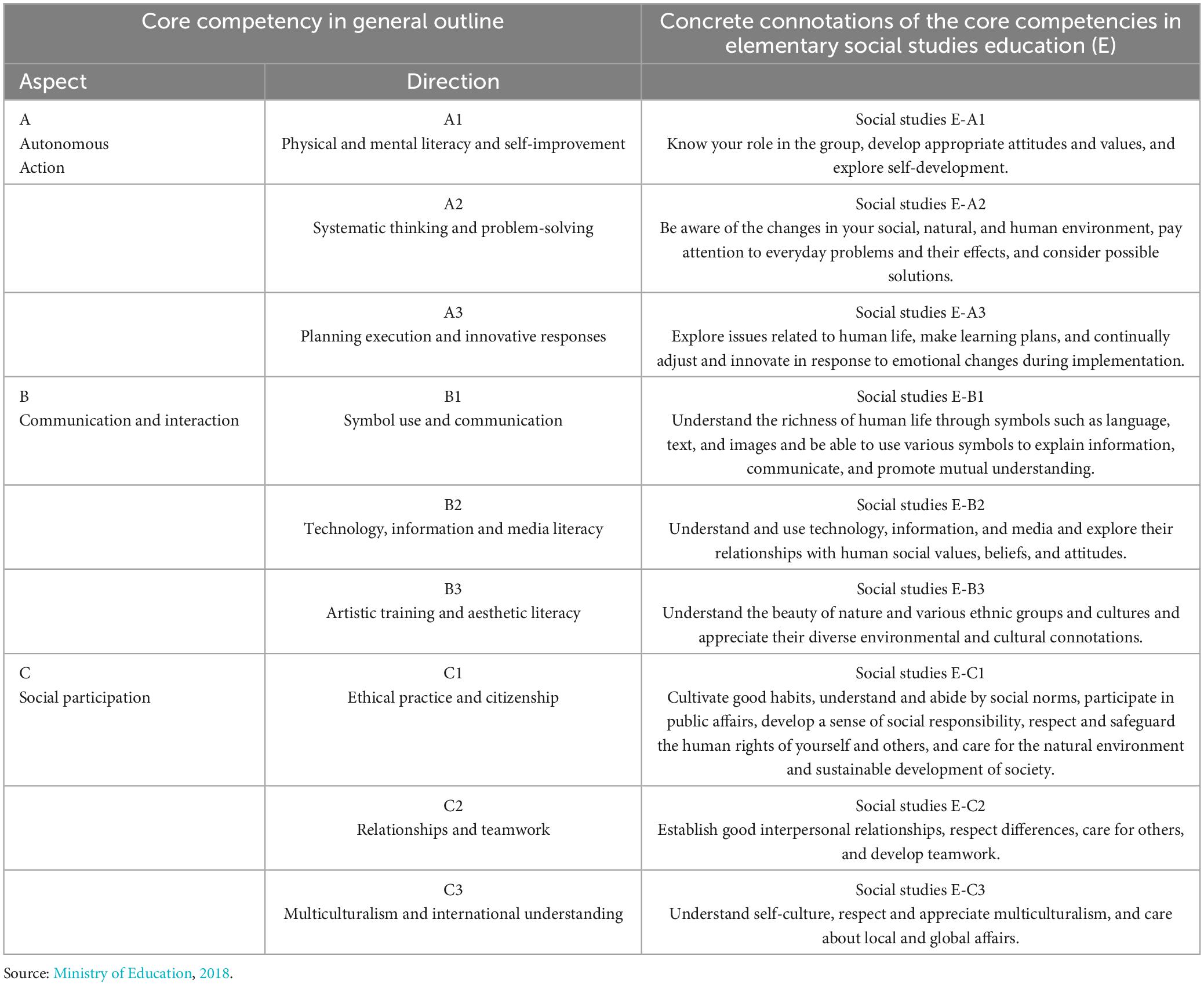

2.6 Concrete connotations of core competencies in elementary social studies

The concept of core competencies in 12-Year Basic Education emphasizes lifelong learning. These competences are divided into three broad dimensions, namely, autonomous action, communication and interaction, and social participation. Each dimension involves three items. Specifically, spontaneity entails physical and mental wellness and self-advancement; logical thinking and problem solving; and planning, execution, innovation and adaptation. Communication and interaction entails semiotics and expression; information and technology literacy and media literacy; and artistic appreciation and aesthetic literacy. Finally, social participation entails moral praxis and citizenship; interpersonal relationships and teamwork; and cultural and global understanding ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ).

The concrete connotations of the core competencies in social studies listed in Table 1 .

Table 1. Concrete connotations of core competencies in social studies.

2.7 Considering this local study is of global importance–Sustainable Development Goals and teaching design for children’s cultural learning for sustainability

Sustainability is a much debated concept. Environmental sustainability refers to the responsible and balanced management of natural resources and ecosystems to ensure their long-term health and resilience while meeting the needs of current and future generations ( James, 2024 ; Malin et al., 2024 ).

In 1962, the American biologist Rachel Carson published the book Silent Spring, which revealed the dangers of DDT pesticides in times of rapid industrial development. In 1970, the United States became the first country to establish laws regarding environmental education. Over the following 10 years, United Nations (UN) conferences focused on the environment and sustainability. The purpose of environmental education is not only to solve environmental problems but also to emphasize intergenerational justice as the core of sustainable development ( Yeh, 2017 ; Chen, 2023 ; Feng, 2023 ).

In 1987, the UN World Commission on Environment and Development published the Brundtland Report, also known as Our Common Future, which defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present generation without jeopardizing the ability of the next generation to meet their needs.” The Brundtland Report highlighted the necessity of sustainable development to balance the economy, society, and the environment and sparked many initiatives promoting education on sustainable development. For example, the UN’s decade of education for sustainable development (2005–2014) plan proposed taking action through education to instill skills of critical thinking, communication, coordination, and conflict resolution in students. Moreover, the plan emphasized the goal of educating global citizens who can respect the lives and cultures of others ( Yeh, 2017 ; Chen, 2023 ; Feng, 2023 ).

The term “sustainability” is known to be a solution to environmental and social problems. Sustainability is defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” It emphasizes “social, economic and environmental sustainability and the interaction of these three elements” ( Huang and Cheng, 2022 ). In education, education for sustainable development is a term used by the United Nations and is defined as education that encourages changes in knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to enable a more sustainable and just society for all ( Zhang et al., 2023 ).

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is UNESCO’s education sector response to the urgent and dramatic challenges the planet faces. In 2015, the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were passed by the UN Assembly, 195 nations agreed with the UN that they can change the world for the better. This will be accomplished by bringing together their respective governments, businesses, media, institutions of higher education, and local NGOs to improve the lives of the people in their country by the year 2030. The Global Challenge for Government Transparency: The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030 Agenda. Here’s the 2030 Agenda: (1) eliminate poverty; (2) erase hunger; (3) establish good health and wellbeing; (4) provide quality education; (5) enforce gender equality; (6) improve clean water and sanitation; (7) grow affordable and clean energy; (8) create decent work and economic growth; (9) increase industry, innovation, and infrastructure; (10) reduce inequality; (11) mobilize sustainable cities and communities; (12) influence responsible consumption and production; (13) organize climate action; (14) develop life below water; (15) advance life on land; (16) guarantee peace, justice, and strong institutions; (17) build partnerships for the goal ( Yeh, 2017 ; New Jersey Minority Educational Development, 2023 ; UNESCO, 2023 ).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a widely accepted framework for promoting sustainable development. SDG4 goal 4.7 pursues the “sustainability” of education to promote sustainable development for country ( Sánchez-Carracedo et al., 2021 ). SDG11 pursues “sustainable cities and communities” in efforts to make them inclusive, safe, and resilient. SDG 11.4 protects countries’ cultural and natural heritage and the cultural landscape that embodies the collective memory and history of the people on the land.

This study designed teaching activities aimed at helping children to understand, visit, see, and care for Beigang; actively protect Taiwan’s culture and heritage; and respect the people’s collective memory and history. It is hoped that such teaching practice can inspire children to care about their living environment and promote the sustainable development of their living environment. This local study is of global importance. The discussion draws meaningful connections with other research studies ( Farhana et al., 2017 ; Huang and Cheng, 2022 ).

3 Proposed teaching design for children’s cultural learning for sustainability at elementary school in Taiwan

Beigang’s Township, formerly known as “Ponkan (笨港),” is in the southwest of Yunlin County, Taiwan. Beigang is a small town with a rich history; it is a center of Mazu belief, one of the three major towns in Yunlin, and the gateway to the Yunlin coast. Beigang is also the political and economic center of Yunlin and is a key town for transportation, sightseeing, culture, medical care, and education. The old street features several historic sites that have a long and prosperous history.

3.1 The proposed course design has the following goals

Strengthen children’s understanding and connection with Beigang’s history and culture.

Teach children about Beigang’s cultural characteristics.

Enable children to identify with their hometown-Beigang.

Assist children with applying knowledge in practical situations.

Children will be taught Beigang’s local characteristics through the proposed course design, which can promote the public welfare. The proposed course design also applies the concepts of “taking initiative,” “engaging in interaction,” and “seeking the common good” from the Curriculum Guidelines of 12-year Basic Education and develops courses that cultivate students’ educational competencies.

This course considered the regional, ethnic, and school characteristics for curriculum development, and prioritize real-world experience. This course improved the quality of independent thinking, value judgments, rational decision-making, innovation, and social participation ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ). Enhance the exploration and knowledge of history, and geography. Cultivate children’s awareness of ethnic groups, societies, localities, countries, and the world and instill a sense of responsibility that includes the recognition of diversity, value of human rights, and concern for global sustainability ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ; Shih, 2020 ).

3.2 Tips for designing teaching activities

Lesson plan structure: understand Beigang, visit Beigang, see Beigang, care Beigang.

Analysis on teacher preparation and materials: hold a meeting to discuss incorporating the key points into each subject.

Student preparation: help students develop the ability to discuss, think critically, and brainstorm ideas during the course.

3.3 Teaching process

Phase 1: Getting to understand Beigang.

Phase 2: Visiting Beigang. Combine off-campus teaching and tours of historical sites.

Phase 3: Seeing Beigang. Introduce the geography and natural scenery of Beigang.

Phase 4: Caring for Beigang. Introduce the beauty and future of Beigang.

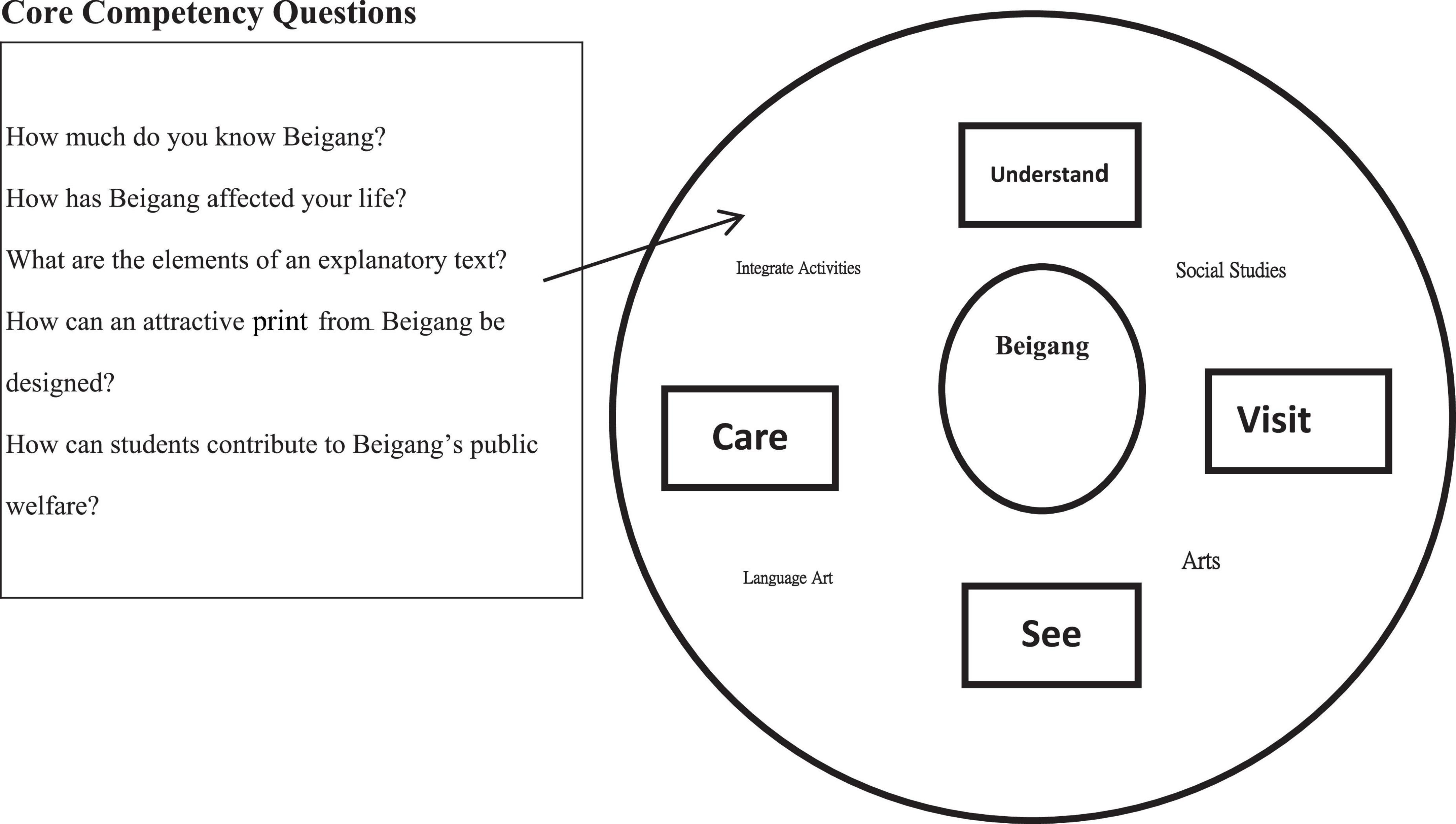

3.4 Core competency questions, major domain, and subdomains

The researcher first considered questions on core competencies and then considered questions regarding the major domain and subdomains. The major domain was social studies, and the subdomains were integrative activities, language arts, and arts. The core competency questions were as follows:

(1) How much do you know Beigang?

(2) How has Beigang affected your life?

(3) What are the elements of an explanatory text?

(4) How can an attractive postcard from Beigang be designed?

(5) How can students contribute to Beigang’s public welfare?

The core competency questions, major domain, and subdomains are presented in Figure 3 .

Figure 3. The core competency questions, major domain, and subdomains (source: developed in this study).

4 Research method

4.1 documentary analysis method.

This study employed the documentary analysis method, which involves the use of documents as the primary data source. Documentary analysis is a qualitative research approach in which the researcher interprets documents to derive meaningful insights on a particular topic ( Wang and Shih, 2022 , 2023 ). In this study, the researcher applied the documentary analysis method to analyze issues related to social studies education in Taiwan’s elementary schools. Additionally, the principle of the curriculum outline for social studies was analyzed. Finally, the researcher used analytical and interpretive skills to establish connections with the objectives of the United Nations’ SDGs.

4.2 Case study

Qualitative case studies enable researchers to investigate complex phenomena by identifying relevant factors and observing their interaction. Case studies involve diverse methods of data collection—such as observation, interviews, surveys, and document analysis—along with comprehensive descriptions provided by the study participants ( Shih, 2022 ). In the present study, data were collected through semistructured interviews that followed a predefined outline. The interviewees were both teachers and students, and they shared their perspectives and insights regarding the social studies curriculum.

4.3 Elementary school selected for the case study

The elementary school featured in this case study is located in Yunlin County, Taiwan, and was established in 1927. The school is guided by a set of educational principles that revolve around a humanistic spirit, diverse and dynamic teaching management, the fostering of warm teacher–student friendships, and the promotion of a vibrant and wholesome childhood experience for its students.

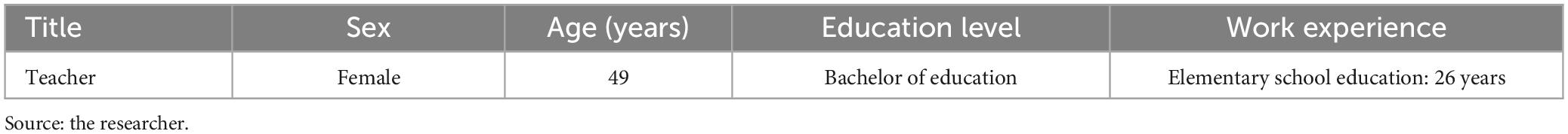

4.4 Data collection

The primary data source in this study was interview transcripts, and the collected data were systematically coded using self-developed categories. The researcher visited the elementary school to conduct semistructured interviews with the teacher and students on 16 June 2023. All the interviewees had been actively involved in the planning and design of the social studies course. During the interviews, the interviewees freely expressed their opinions regarding the course. Prior to their participation, the interviewees were informed about the study’s objectives, and they provided their informed consent. Consent letters and interview outlines were shared with the interviewees, including the teachers and the students’ parents ( Shih, 2022 ). Each interview session lasted approximately 1 h. The demographic details of the interviewees are presented in Tables 2 – 4 outlines the interview coding method.

Table 2. Coordinator of the social studies curriculum.

Table 3. Participants of the social studies curriculum.

Table 4. Interview codes.

The codes correspond to the interviewees and dates. For example, “Coordinator interview, A20190612” corresponds to the interview with the elementary school teacher who serves as the coordinator of the social studies program; this interview was conducted on 16 June 2023. “Student interview 1, A20230616” corresponds to the interview with student 1, a participant, conducted on 16 June 2023.

4.5 Course design: Beigang

4.5.1 tiâu-thian kiong (朝天宮).

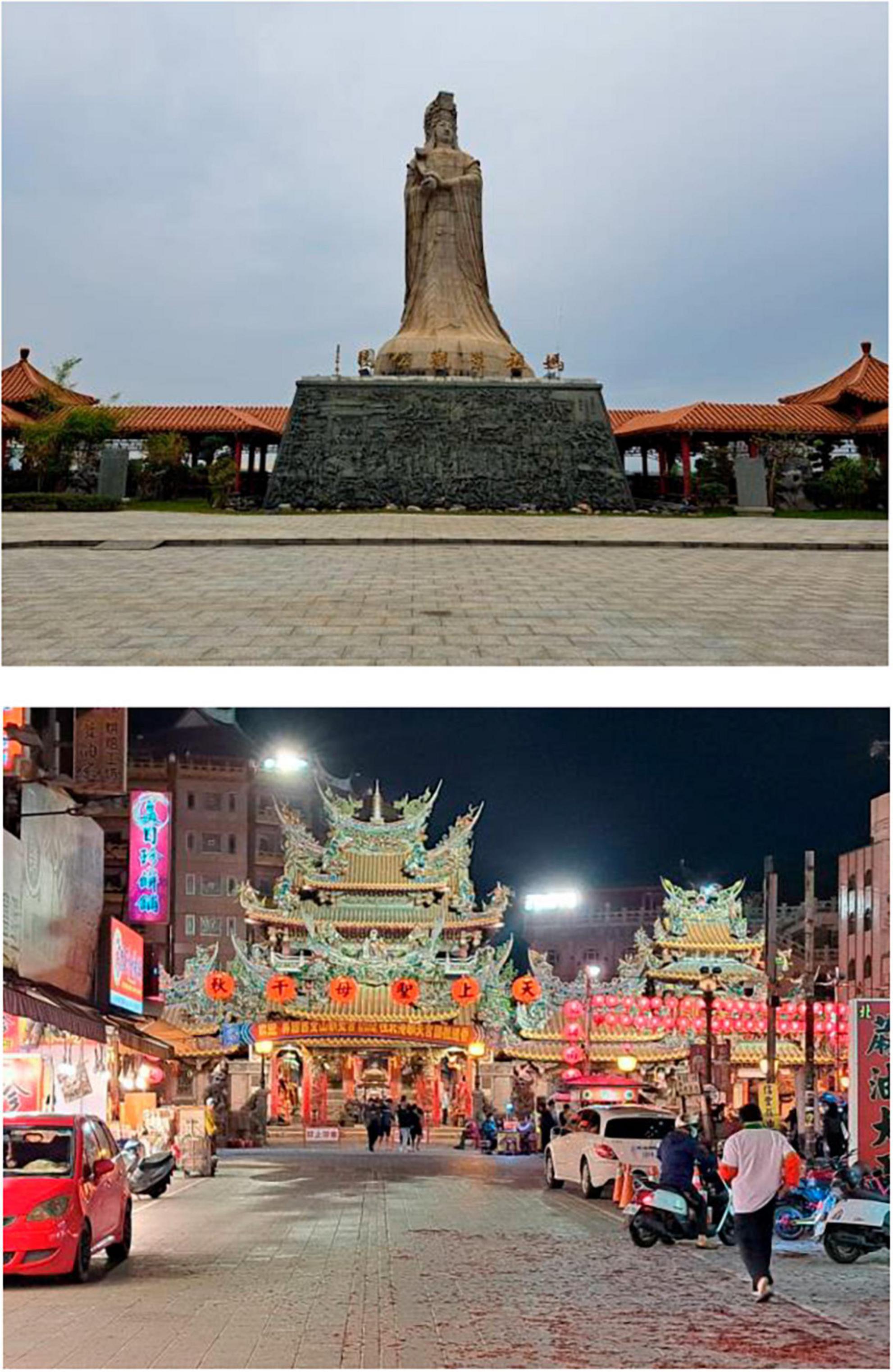

Tiângthian esign, which locals call má tsóo king (媽祖宮), is the most famous landmark in Beigang Township ( Figure 4 ). Established in 1694 AD during the Kangxi period of the Qing dynasty. Tiownship. Estab serves as the main temple for more than 300 Mazu temples across the country. The Tiemples across is dedicated to many gods, such as Mazu and Guanyin. The beam frames and wood carvings in the temple were all created by famous craftsmen. The stone statues of the Dragon Kings of the Four Seas perched along the stone railings outside the temple exemplify the religious and artistic masterpieces of the temple. The Tie frames and welcomes worshippers throughout the year. The liveliest times to visit are during the Lantern Festival on the 15th day of the first month of the lunar calendar and Mazu’s birthday on March 23. Mazu’s birthday, visitors come to Beigang from across the world, and the entire city is shrouded in a festive atmosphere.

Figure 4. Beigang Tiâu-thian Kiong.

4.5.2 Beigang Daughter Bridge (北港女兒橋)

The Beigang Daughter Bridge was constructed from Taiwan’s oldest iron bridge, the Beigang–Fuxing Iron Bridge ( Figure 5 ). The small train that once operated over the bridge is no longer in service; however, the dragon-shaped bridge has become a hotspot for photos and social media check-ins. In the evenings, people can enjoy the sunset while walking over the Beigang River Head.

Figure 5. Beigang Daughter Bridge.

4.5.3 Beigang Cultural Center (北港文化中心)

To learn more about Mazu rituals, a visit to the Beigang Cultural Center is a must. The center describes the process of circumambulation and the roles of participants in the ritual, such as the leader of the procession (bao ma zai) (報馬仔), costume makers (zhuang yi tuan) (莊儀團) and ritual band (kai lu gu) (開路鼓). The cultural center hosts many other temporary exhibitions.

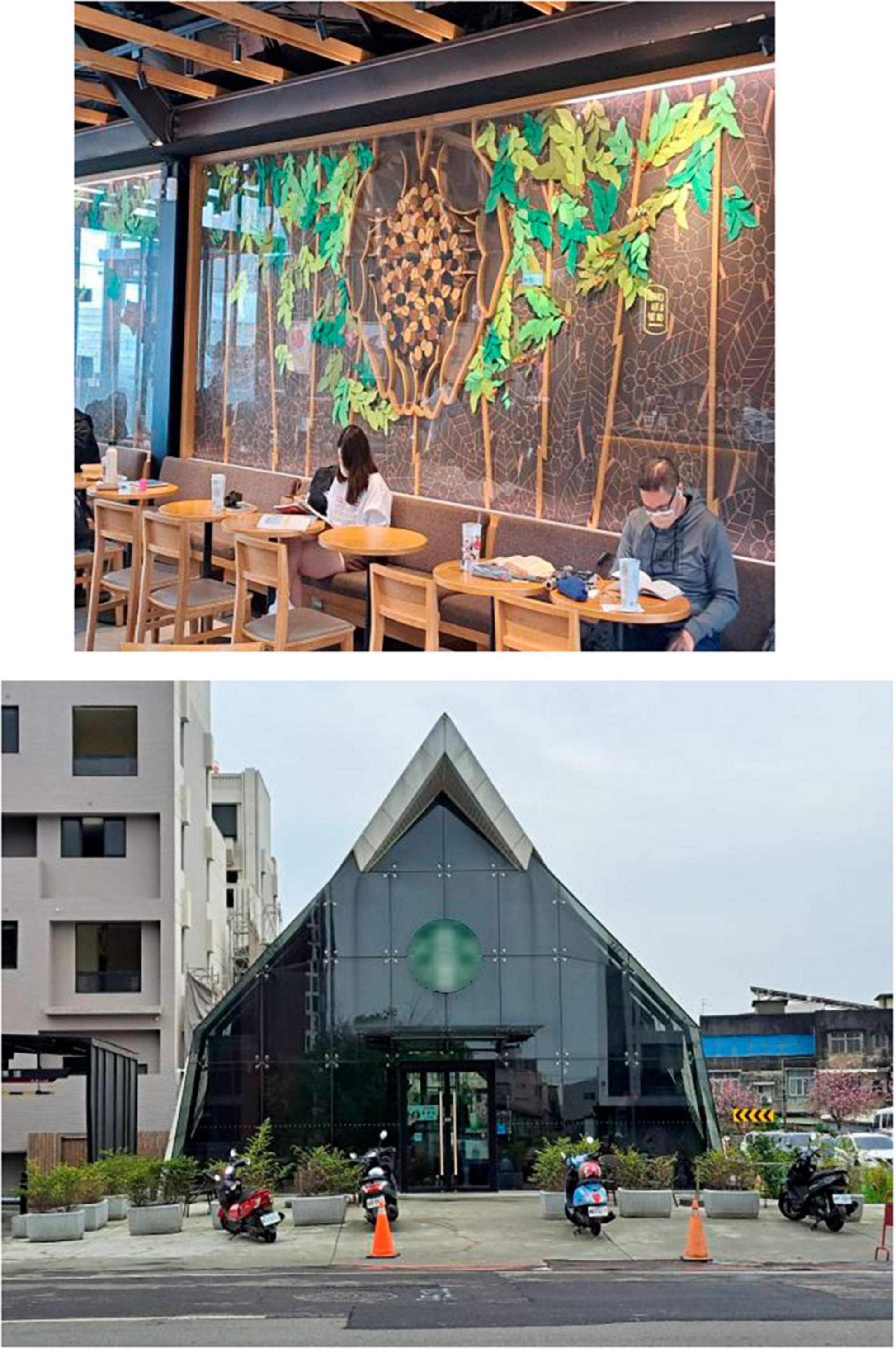

4.5.4 Beigang Starbucks (北港星巴克)

The first Starbucks store in Beigang is on Huanan Road (Provincial Highway 19), the main road entering and leaving Beigang ( Figure 6 ). The architecture of the store reflects the religious characteristics of the town; religious imagery is present from the exterior and interior walls to the grille ceiling. Through the simple reddish-brown tones that resemble temple interiors, the pious, solemn architectural style exudes history and local sentiment.

Figure 6. Beigang Starbucks.

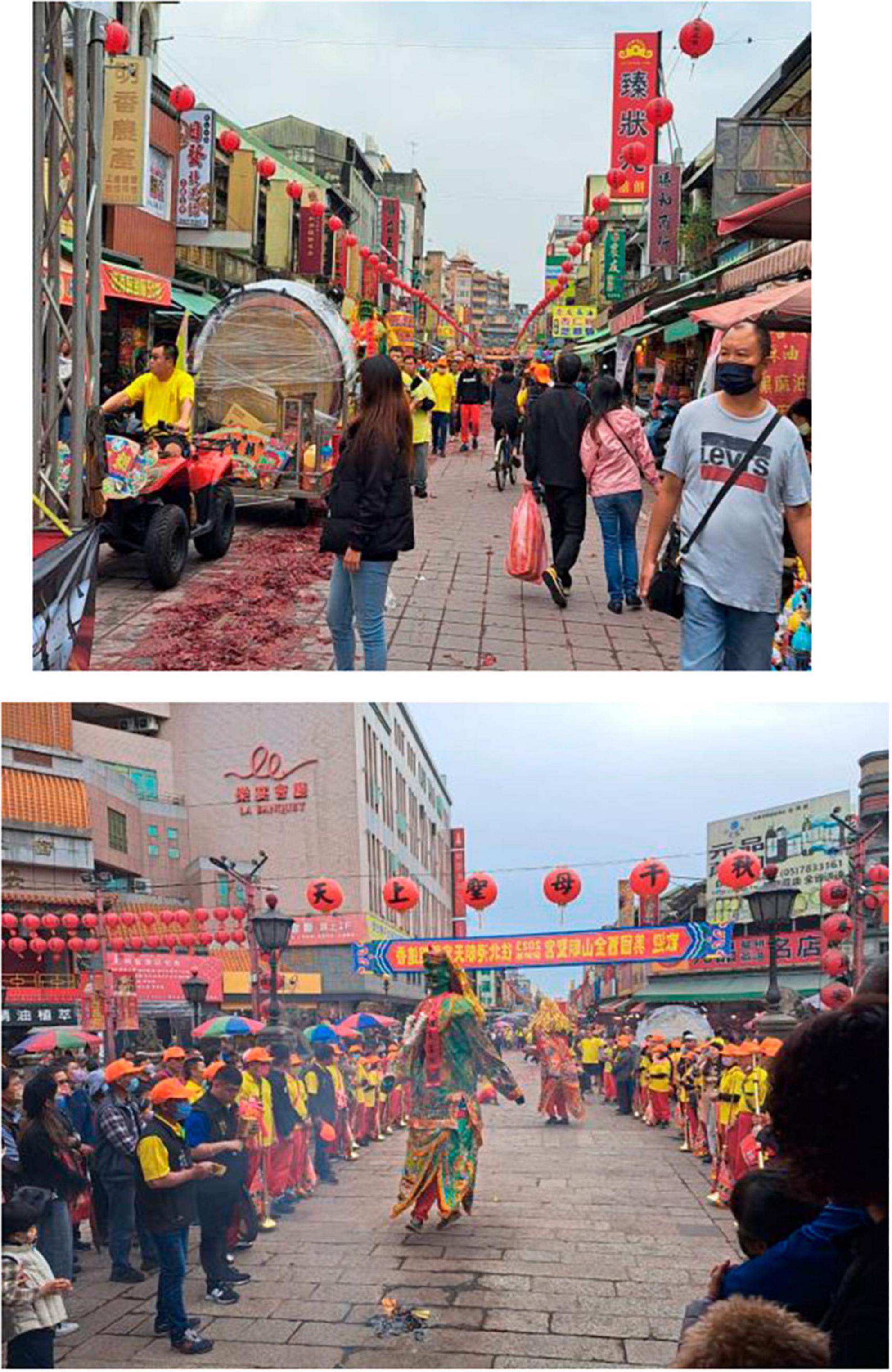

4.5.5 Beigang Old Street (北港老街)

Beigang Old Street, located south of Tiâu-thian Kiong, has local flair ( Figure 7 ). Baroque buildings line both sides of the street, and the shops sell local treats and produce that are popular among tourists. Pilgrimage groups from across Taiwan are a common sight. The street is lively, and the atmosphere is truly unique and worth experiencing.

Figure 7. Beigang Old Street.

4.6 Limitation

This research is a case study, and this curriculum is only implemented in one school in Taiwan, so the validity of extrapolation to other case schools will be limited.

5.1 Curriculum development connected to the pulse of life, a sense of care for local communities, and cultivation of local thinking

The social studies curriculum is intricately connected to the pulse of life, a sense of care for local communities, and cultivation of local thinking. The approach employed in the curriculum aims to enable children to not only connect with their own country and culture but also embrace the role of being a global citizen ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ). Student 2 stated the following:

Beigang Old Street (北港老街) is so vibrant and filled with people. I like Beigang Old Street. I see many ancient buildings on the street, and I feel a need to protect them (Student interview 2, C20230616).

Student 4 expressed the following:

I like Tiâu-thian Kiong (朝天宮). My grandma used to take me to worship there. She has passed away. Whenever I visit Tiâu-thian Kiong, I miss my grandma. For me, Tiâu-thian Kiong symbolizes my grandma (Student interview 4, D20230616).

5.2 Child-centered and problem-oriented curriculum that integrates students’ interests and the local environment into the learning process

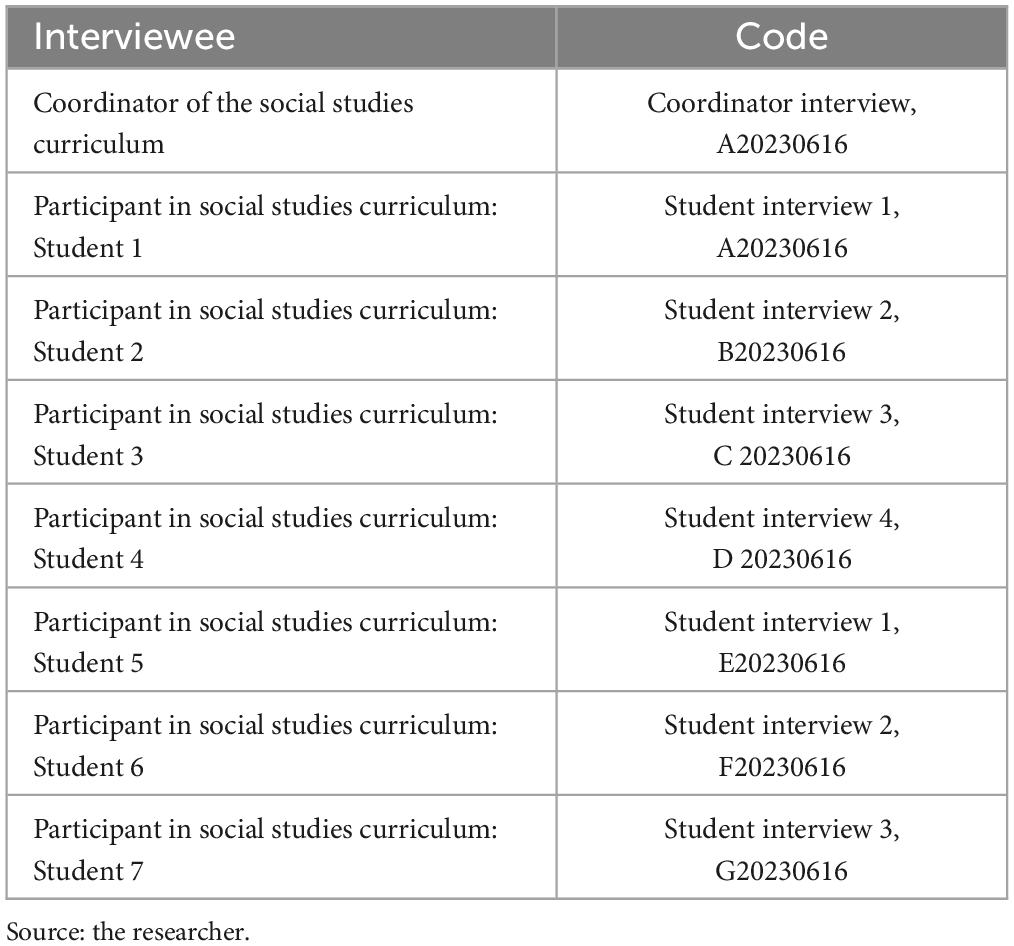

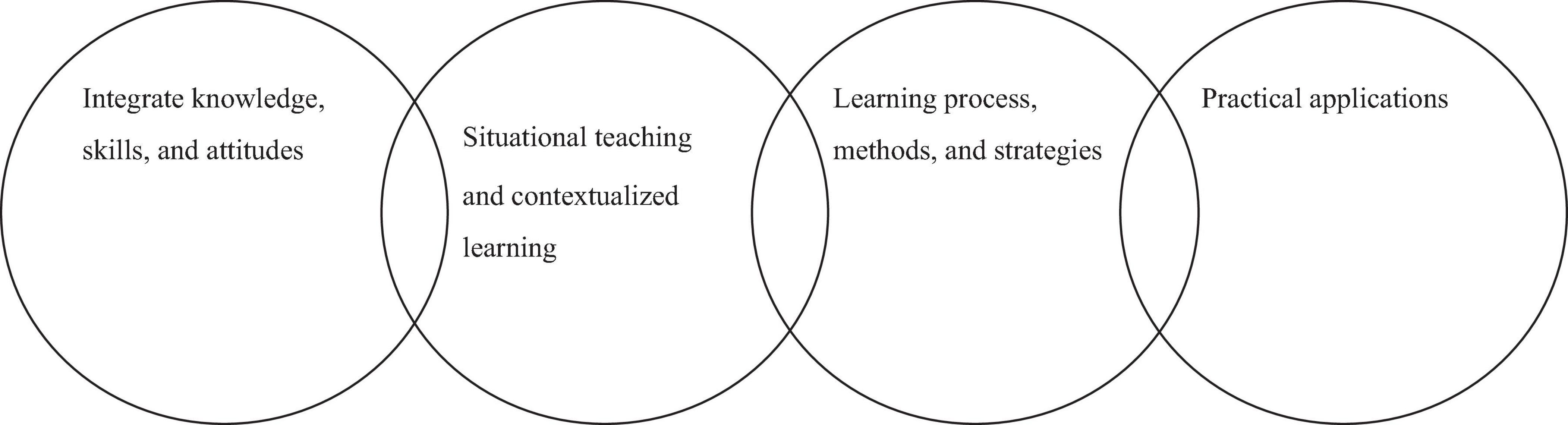

This social studies curriculum is designed to be child-centered and problem-oriented and to integrate students’ interests and the local environment into the learning process. This approach equips students with the skills to observe, investigate, collect data, create diagrams and thematic maps, write reports, inquire, and acquire other practical competencies ( Ministry of Education, 2018 ). Therefore, teachers must adopt a competency-oriented curriculum design and teaching approach. To illustrate competency-oriented curriculum design and teaching, Fan (2016) introduced a concept map containing four interconnected circles ( Figure 3 ). Competency-oriented curricula and teaching seamlessly integrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes, emphasizing that learning should not be solely centered on knowledge acquisition. Additionally, learning should be situational and contextualized, and the learning content should include appropriate real-life experiences, events, situations, and contexts. Furthermore, curriculum planning and teaching must combine learning content with scientific inquiry, placing substantial emphasis on learning processes, strategies, and methods. This approach can help cultivate self-learning and life-long learning. Finally, classroom activities should give students opportunities to apply their knowledge and develop transferrable skills that can be effectively employed in real-world scenarios ( Fan, 2016 ). The concept map of competency-oriented curricula and teaching in social studies is displayed in Figure 8 .

Figure 8. The concept map of competency-oriented curricula and teaching in social studies (source: Fan, 2016 ).

The aim of the design of the course investigated in this study was to synthesize children’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes and to emphasize the importance of situational teaching, contextualized learning, and the practical application of knowledge. The cultural course enables students visiting Beigang to learn about the town’s cultural landscape, interact and communicate with people, and participate in sustainable development in their hometown. Through this educational experience, children can learn how to be sensitive, caring, introspective, and respectful toward their hometown and contribute to the creation of a better living environment. The course fosters children’s cultural learning to the benefit of the sustainability of their hometown.

The teacher asked the following questions:

Let’s review Beigang again.

Where are you from?

Do you love your hometown?

How can you contribute to the sustainable development of your hometown?

Student 5 stated the following:

I love my hometown, Beigang. I want to keep Beigang beautiful forever (Student interview 5, E20230616).

Student 6 expressed the following:

I love Beigang, my hometown. I’m going to the Beigang Sports Park to help plant trees so that there will be more and more trees. Then, the air in Beigang will get better and better, and the people living in Beigang will become healthier (Student interview 6, F20230616).

Student 7 stated the following:

I love my hometown, Beigang. I’m going to the Beigang Fruit and Vegetable Market to help remove trash. I want Beigang to become cleaner (Student interview 7, G20230616).

5.3 Improving students’ competencies and skills in the context of sustainability

The pursuit of sustainable development, in alignment with the United Nations’ SDGs, is a top priority in both the internal and external policies of the Union. As acknowledged by the UN 2030 Agenda, a commitment to sustainable development is reflected through the endorsement of 17 universal SDGs and related targets. These goals aim to strike a balance across all dimensions of sustainable growth, such as economic, environmental, and social considerations ( Fleaca et al., 2023 ).

Education on sustainability should be capable of cultivating the mindset and skills to meet the complex sustainability challenges faced in the 21st century. The critical roles of teachers in this context were thoroughly analyzed in this study, and the findings underscore the importance of teachers in cultivating students’ sustainability competencies and skills ( Chatpinyakoop et al., 2022 ; Fleaca et al., 2023 ). Therefore, the design of the social studies course aims to foster the development of students’ sustainability competencies and skills in the context of sustainability.

The teacher gave the following description:

“Course design: Beigang” increases the awareness of the changes in students’ social, natural, and human environments. Moreover, it equips students to be able to pay attention to everyday problems and the effects of these problems on their lives as well as to consider possible solutions. For example, the Beigang Daughter Bridge (北港女兒橋) was constructed from Taiwan’s oldest iron bridge, the Beigang–Fuxing Iron Bridge. The small train that once operated over the bridge is no longer in service; however, the dragon-shaped bridge has become a hotspot for photos and social media check-ins. The original old railway has been redesigned and become a new tourist attraction. The teacher described the transformation of the bridge, and the students experienced the renewal of the bridge and pledged to take good care of it (Coordinator interview, A20230616).

Student 1 stated the following:

I like Matsu. Matsu blesses those who live in Beigang. I want to protect Tiâu-thian Kiong (朝天宮). Mazu lives in Tiâu-thian Kiong, and if Tiâu-thian Kiong were to be destroyed, Matsu would have nowhere to live (Student interview 1, A20230616).

Student 3 expressed the following:

Beigang Old Street (北港老街) is so vibrant and filled with people. I like Beigang Old Street. I see many ancient buildings on the street, and I feel a need to protect them (Student interview 3, C20230616).

6 Discussion

6.1 a social studies curriculum should adapt to social problems and focus on students’ life experiences, and cultivate caring in students in curriculum.

Children are surrounded by many influential role models in society—for example, parents, siblings, teachers, friends, and TV characters—and their learning occurs through being explicitly taught by others, through direct observation, and through participation in activities. These are students’ life experiences ( Farhana et al., 2017 ; Ye and Shih, 2021 ). A social studies curriculum should adapt to social problems and focus on students’ life experiences, and cultivate caring in students in curriculum. After all, children learn to care for those around them through life experiences ( Hung et al., 2021 ; Shih et al., 2022 ; Shih, 2024 ).

6.2 This curriculum overcomes the shortcomings of knowledge-based learning

Teachers and students often spend excessive time mastering and memorizing content. Moreover, previous curricula were bloated and failed to instill in students the key skills and core literacies required to face a changing world. Therefore, the 12-Year Basic Education Curriculum focuses on literacy, is based on both learning content and learning performance, emphasizes active inquiry and practice, and hopes to prevent excessive memorization. Therefore, this curriculum overcomes the shortcomings of knowledge-based learning by providing a high-quality educational experience, and campus sustainability ( Ministry of Education, 2014 , 2018 , 2019 ; Hung et al., 2020 ; Washington-Ottombre, 2024 ).

6.3 Select appropriate themes, and at least one inquiry activity should be designed for each unit

In order to implement and link up the exploration and practice courses that are valued at the junior and senior high school stages, the key points of implementation in the new curriculum in the social studies are to standardize the “compilation and selection of textbooks for elementary schools or the compilation of textbooks for textbooks and the design of integrated curriculum in fields.” In addition to selecting appropriate themes to develop comprehensive teaching materials, at least “one inquiry activity should be designed for each unit, and each semester should integrate the content learned in the semester, and at least one theme inquiry and practice unit should be planned.” Therefore, at the elementary school site, different from traditional teaching methods and habits, guide students to explore and practice in the social field, and then cultivate children’s core literacy ( Ministry of Education, 2014 ; Yu, 2023 ).

7 Conclusion and implication

7.1 conclusion.

The findings of this study were as follows: (1) The social studies curriculum development in Taiwan is connected to the pulse of life, a sense of care for local communities, and cultivation of local thinking. (2) This social studies curriculum adopts a child-centered and problem-oriented approach and integrates students’ interests and the local environment into the learning process. (3) It effectively enhances students’ sustainability-related competencies and skills.

These findings offer valuable insights for teachers and can enable them to shape the direction of their social studies courses and cultivate children’s concept of sustainable development. In addition, the sustainability competences are systems thinking competence, futures thinking competence, values thinking competence, collaboration competence and action-oriented competence ( Marjo and Ratinen, 2024 ). In values thinking competence, this study effectively enhances students’ sustainability-related competencies and skills. The existing sustainability competencies’ frameworks are linked to social studies curriculum and the learning outcomes that were sought in this case study.

In the end, ensuring a fair and decent livelihood for all people, regenerating nature and enabling biodiversity to thrive, have never been more important for sustainable development ( Bianchi et al., 2022 ). In addition, hundreds of sustainability programs have emerged at schools around the world over the past 2 decades. A prime question for employers, students, educators, and program administrators is what competencies these programs develop in students ( Brundiers et al., 2021 ). In this study, Taiwanese children can protect cultural and natural heritage and the cultural landscape that embodies the collective memory and history of the people on the land in the sustainable future.

7.2 Implication

In the 21st century, the world has become more globalized. Globalization has decreased distinctions between countries and has increased interdependency among countries ( Wang and Shih, 2023 ). However, one of the biggest challenges that globalization poses to blurr the unique local cultural characteristics. in recent years, awareness of local culture, which is based on cultural transmission with respect to language, history, geography, knowledge, customs, art, and an appreciation of the value of local identity and traditional culture, has become a priority. Local culture has become a crucial part of education in Taiwan, and they help children better appreciate the culture styles behind their everyday lives ( Shih, 2022 ). This local study is of global importance.

Finally, the growing international significance of education for sustainable development (ESD), and is a matter of global importance, the requirements and needs of people differ according to their regional circumstances ( de Haan, 2006 , 2010 ). To create a more sustainable world and to engage with issues related to sustainability as described in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), individuals must become sustainability change-makers. They require the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that empower them to contribute to sustainable development ( UNESCO, 2017 ).

The trend toward the standardization of education raises the question of why teachers should focus on local contexts ( Smith and Sobel, 2010 ). Historically, before the advent of common schools, education grounded in local concerns and experiences was the norm, playing a crucial role in transitioning from childhood to adulthood. However, in modern schooling, children often experience a growing disconnect between their community lives and classroom experiences ( Smith and Sobel, 2010 ). Hence, elementary teachers in Taiwan are recommended to focus on actively incorporating local cultural elements into the classroom. This approach aims to bridge the gap between children’s community experiences and their educational environment. This study is of local importance in Taiwan.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardians/next of kin, for participation in this study and for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

Y-HS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., and Cabrera Giraldez, M. (2022). GreenComp The European Sustainability Competence Framework , eds Y. Punie and M. Bacigalupo (Luxembourg: European Union).

Google Scholar

Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G., Cohen, M., Diaz, L., and Doucette-Remington, S. (2021). Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustainability Sci. 16, 13–29. doi: 10.1007/s11625-020-00838-2

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chan, P. J. (2020). “Literacy-oriented curriculum and teaching in social studies,” in Teaching materials and methods in social studies in elementary school , ed. Chen and Chan (Taipei City: Wunan), 31–46.

Chatpinyakoop, C., Hallinger, P., and Showanasai, P. (2022). Developing capacities to lead change for sustainability: a quasi-experimental study of simulation-based learning. Sustainability 14:10563.

Chen, W. Z. (2023). After 50 Years, Scholars Published a Book Review “Rachel Carson – The Pioneer Who Created a New World of Environmental Protection with His Pen”. Available Online at: https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/57638398

de Haan, G. (2006). The BLK ‘21’ programme in Germany: a ‘Gestaltungskompetenz’-based model for education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 12, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/13504620500526362

de Haan, G. (2010). The development of ESD-related competencies in supportive institutional frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 56, 315–328. doi: 10.1007/s11159-010-9157-9

Fan, H. H. (2016). Core competencies and the twelve-year national basic education curriculum outline: a guide to “national core competencies: the DNA of the twelve-year national education curriculum reform. Educational Pulse 5.

Farhana, B., Winberg, M., and Vinterek, M. (2017). Children’s learning for a sustainable society: influences from home and Preschool. Educ. Inq. 8, 151–172. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2017.1290915

Feng, D. Y. (2023). Understanding SDGs, Pulsating with the World. Available Online at: www.sdec.ntpc.edu.tw/p/405-1000-1672,c228.php?Lang=zh-tw (accessed December 2, 2023).

Fleaca, B., Fleaca, E., and Maiduc, S. (2023). Framing teaching for sustainability in the case of business engineering education: process-centric models and good practices. Sustainability 15:2035. doi: 10.3390/su15032035

Huang, H., and Cheng, E. W. L. (2022). Sustainability education in china: lessons learnt from the teaching of geography. Sustainability 14:513.

Hung, L. C., Liu, M. H., and Chen, L. H. (2020). Analysis of cross-curricular activities in social studies textbooks for junior high schools: a competence-oriented design perspective. J. Textbook Res. 13, 1–32. doi: 10.6481/JTR.202012_13(3).01

Hung, L. C., Liu, M. H., and Chen, L. H. (2021). Content analysis on inquiry tasks in Taiwan’s elementary social studies textbooks from the perspective of inquiry-based design. J. Textb. Res. 14, 43–77. doi: 10.6481/JTR.202112_14(3).02

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

James, N. (2024). Urbanization and its impact on environmental sustainability. J. Appl. Geogr. Stud. 3, 54–66. doi: 10.47941/jags.1624

Malin, B., Pettersson, K., and Westberg, L. (2024). Tracing sustainability meanings in rosendal: interrogating an unjust urban sustainability discourse and introducing alternative perspectives. Local Environ. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2023.2300956

Marjo, V., and Ratinen, I. (2024). Sustainability competences in primary school education – a systematic literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 30, 56–67. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2023.2170984

Ministry of Education (2014). Curriculum Guidelines 12-year Basic Education: General Guidelines. Taipei: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2018). 12-year Basic Education Curriculum Outline–National Primary and Secondary Schools and Senior High Schools-Social Studies. Taipei: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2019). 12-year Basic Education Curriculum Outline–National Primary and Secondary Schools and Senior High Schools-Social Studies (Course Manual). Taipei: Ministry of Education.

New Jersey Minority Educational Development (2023). The Global Challenge for Government Transparency: The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2030 Agenda. Available Online at: https://worldtop20.org/global-movement/ (accessed December 2, 2023).

Sánchez-Carracedo, F., Moreno-Pino, F., Romero-Portillo, D., and Sureda, B. (2021). Education for sustainable development in Spanish university education degrees. Sustainability 13:1467. doi: 10.3390/su13031467

Shih, Y. H. (2020). Learning content of ‘multiculturalism’ for children in Taiwan’s elementary schools. Policy Futures Educ. 18, 1044–1057. doi: 10.1177/1478210320911251

Shih, Y. H. (2022). Designing culturally responsive education strategies to cultivate young children’s cultural identities: a case study of the development of a preschool local culture curriculum. Children 9:1789. doi: 10.3390/children9121789

Shih, Y. H. (2024). Case study of intergenerational learning courses implemented in a preschool: perceptions of young children and senior citizens. Educ. Gerontol. 50, 11–26. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2023.2216089

Shih, Y. H., Chen, S. F., and Ye, Y. H. (2020). Taiwan’s “white paper on teacher education”: vision and strategies. Universal J. Educ. Res. 8, 5257–5264.

Shih, Y. H., Wu, C. C., and Chung, C. F. (2022). Implementing intergenerational learning in a preschool: a case study from Taiwan. Educ. Gerontol. 48, 565–585. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2022.2053035

Smith, G. A., and Sobel, D. (2010). Place- and Community-Based Education in Schools. New York: Routledge.

UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2023). Education for Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO.

Wang, R. J., and Shih, Y. H. (2022). Improving the quality of teacher education for sustainable development of Taiwan’s education system: a systematic review on the research issues of teacher education after the implementation of 12-year national basic education. Front. Psychol. 13:921839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921839

Wang, R. J., and Shih, Y. H. (2023). What are universities pursuing? a review of the quacquarelli symonds world university rankings of Taiwanese universities (2021–2023). Front. Educ. 8:1185817. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1185817

Washington-Ottombre, C. (2024). Campus sustainability, organizational learning and sustainability reporting: an empirical analysis. Int. J. Sustainab. High. Educ. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-12-2022-0396 Online ahead of Print.

Ye, Y. H., and Shih, Y. H. (2021). Development of John Dewey’s educational philosophy and its implications for children’s education. Policy Futures Educ. 19, 877–890. doi: 10.1177/1478210320987678

Yeh, S. C. (2017). Exploring the developmental discourse of environmental education and education for sustainable development. J. Environ. Educ. Res. 13, 67–109.

Yu (2023). [Society] When Exploration and Practice Meet the New Curriculum of Elementary School Social Studies.

Zhang, Y., Sun, S., Ji, Y., and Li, Y. (2023). The consensus of global teaching evaluation systems under a sustainable development perspective. Sustainability 15:818.

Keywords : children, social studies, sustainability, the curriculum outline for social studies, the Curriculum Guidelines of the 12-Year Basic Education

Citation: Shih Y-H (2024) Children’s learning for sustainability in social studies education: a case study from Taiwanese elementary school. Front. Educ. 9:1353420. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1353420

Received: 10 December 2023; Accepted: 29 February 2024; Published: 16 April 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Shih. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi-Huang Shih, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- < Previous

Home > ETD > 1466

Electronic Theses and Dissertations

A case study that examines the community school model in elementary school settings in west tennessee.

LaWanda Michelle Clark

Document Type

Dissertation

Degree Name

Doctor of Education

Leadership and Policy Studies

Concentration

Educational Leadership

Committee Chair

Reginald Green

Committee Member

Charissee Gulosino

DeAnna Owens

If schools are to succeed, children must be provided with more than a school can accomplish alone (Barbour et al., 2010). The need to involve community in the education process to offer services that make students successful and to have these services within the school building are all critical aspects of the community school model (Dryfoos, 1994; Dryfoos et al., 2005; Kronick, 2002, 2005). Literature suggest that school and community collaboration is not a foreign concept. Parents and neighborhoods working together to enhance academics and strengthen the community can be traced back to the reform era of the early twentieth century. More is accomplished when schools, families and communities work together to promote and improve schools (Epstein, 2010). Community schools have the capacity to do more of what is needed to ensure young people's success. Unlike traditional public schools, community schools link school and community resources as an integral part of their design and operation (Blank et al., 2003). As a result of a powerful and supportive learning environment, students, families, schools, and communities become proponents for community schools that emphasize the importance of school functioning, economic competitiveness, student well-being, and community health and development (Sanders, 2006). There is a lack of current awareness, despite the research, on the processes and outcomes of the school and community partnership. This narrative utilizes community school's authentic experiences from multiple sites. The researcher attempts to better comprehend the processes and outcomes of the community school model. This qualitative case study is designed to examine the operational processes and outcomes of the community school model in an elementary setting that was used to resuscitate the diminishing phenomena of school and community collaboration. The researcher strives to the develop and understanding of the perceptions of parents, schools, teachers and community partners regarding the capacity of school and community collaboration. The evidence for this qualitative case study is collected from face-to-face interviews, open-ended survey questions, non-participatory site observations and document reviews. An analysis of the data, which involves recognizing categories or themes in the responses of the research participants, is conducted. As a result o the analysis, the account of live experiences, is used to provide a detail account of the processes and outcomes of the school and community partnership.

Data is provided by the student.

Library Comment

Dissertation or thesis originally submitted to the local University of Memphis Electronic Theses & dissertation (ETD) Repository.

Recommended Citation

Clark, LaWanda Michelle, "A Case Study that Examines the Community School Model in Elementary School Settings in West Tennessee" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations . 1466. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/1466

Since October 06, 2021

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- McWherter Library

- Music Library

- Health Sciences Library

- Lambuth Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Successful technology integration in an elementary school: A case study

Clearly, something special is happening at Peakview Elementary School. Peakview is a new school that is implementing a number of organizational and teaching strategies advocated by the school restructuring reform movement. Among those strategies is the infusion of more than 80 networked microcomputers and related technology and software. This evaluation study examined the impact of the technology on the school community. Using a variety of data collection instruments (e.g., classroom observation, surveys and interviews of school personnel and students), we found consistent evidence that technology plays an essential role in facilitating the school's goals. The technology is positively affecting student learning and attitudes. Teachers are using the technology to adapt to individual students' needs and interests, and to increase the amount and quality of cooperative learning activities. Students use the technology extensively for research and writing activities, as well as for instructional support in a variety of subject areas. Technology has changed the way teachers work, both instructionally and professionally, resulting in a net increase of hours and at the same time greater productivity, effectiveness, and satisfaction. A number of implementation factors are identified as contributing to the success of Peakview's use of technology. These factors form the basis of a set of recommendations for implementing technology successfully in other schools.

Related Papers

Computers & Education

Nikleia Eteokleous