- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What are civil rights?

- Where do civil rights come from?

- What was the civil rights movement in the U.S.?

- When did the American civil rights movement start?

- What is Coretta Scott King best known for?

Civil Rights Act

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Archives - Civil Rights Act (1964)

- United States Senate - Civil Rights Act of 1964

- National Park Service - Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Academia - The Origins and Legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Constitutional Rights Foundation - The Civil Rights Act of 1964

- The History Learning Site - 1964 Civil Rights Act

- Miller Center - The Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Khan Academy - The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Civil Rights Act - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Civil Rights Act - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

What did the Civil Rights Act of 1964 do?

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was intended to end discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in the United States. The act gave federal law enforcement agencies the power to prevent racial discrimination in employment, voting, and the use of public facilities.

Who signed the Civil Rights Act into law?

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law on July 2, 1964, by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Who had proposed the Civil Rights Act?

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been proposed by U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

Recent News

Civil Rights Act , (1964), comprehensive U.S. legislation intended to end discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin. It is often called the most important U.S. law on civil rights since Reconstruction (1865–77) and is a hallmark of the American civil rights movement . Title I of the act guarantees equal voting rights by removing registration requirements and procedures biased against minorities and the underprivileged. Title II prohibits segregation or discrimination in places of public accommodation involved in interstate commerce . Title VII bans discrimination by trade unions, schools, or employers involved in interstate commerce or doing business with the federal government. The latter section also applies to discrimination on the basis of sex and established a government agency, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), to enforce these provisions. In 2020 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that firing an employee for being gay , lesbian, or transgender is illegal under Title VII’s prohibition of sex discrimination ( Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia ). The act also calls for the desegregation of public schools (Title IV), broadens the duties of the Civil Rights Commission (Title V), and assures nondiscrimination in the distribution of funds under federally assisted programs (Title VI).

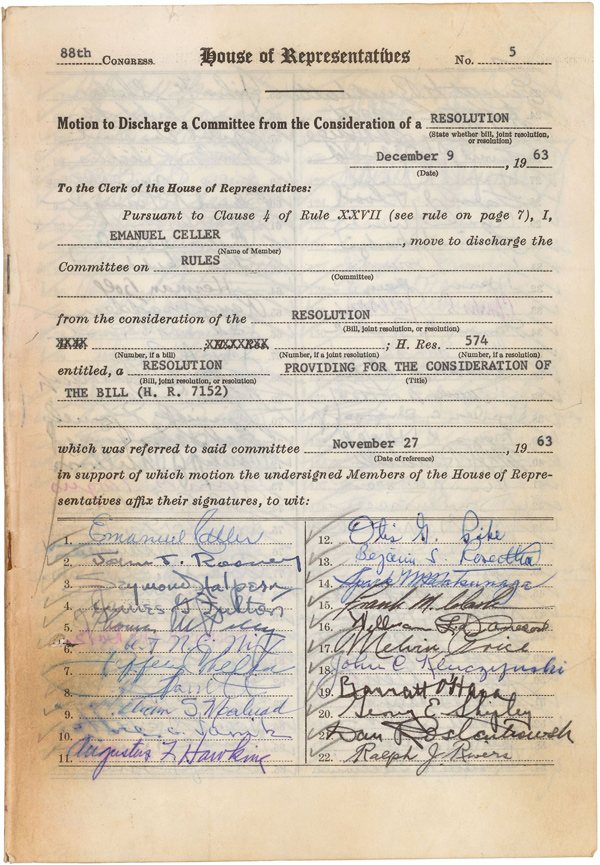

The Civil Rights Act was a highly controversial issue in the United States as soon as it was proposed by Pres. John F. Kennedy in 1963. Although Kennedy was unable to secure passage of the bill in Congress, a stronger version was eventually passed with the urging of his successor, Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson , who signed the bill into law on July 2, 1964, following one of the longest debates in Senate history. White groups opposed to integration with African Americans responded to the act with a significant backlash that took the form of protests, increased support for pro-segregation candidates for public office, and some racial violence. The constitutionality of the act was immediately challenged and was upheld by the Supreme Court in the test case Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. (1964). The act gave federal law enforcement agencies the power to prevent racial discrimination in employment, voting, and the use of public facilities.

The 50th anniversary of the act was celebrated in April 2014 with an event at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin , Texas . Speakers included U.S. Pres. Barack Obama and former presidents Jimmy Carter , Bill Clinton , and George W. Bush . The U.S. Congress marked the anniversary by posthumously awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to civil rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr. , and Coretta Scott King .

Civil Rights Act of 1964

July 2, 1964

In an 11 June 1963 speech broadcast live on national television and radio, President John F. Kennedy unveiled plans to pursue a comprehensive civil rights bill in Congress, stating, “This nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free” (“President Kennedy’s Radio-TV Address,” 970). King congratulated Kennedy on his speech, calling it “one of the most eloquent, profound and unequivocal pleas for justice and the freedom of all men ever made by any president” (King, 11 June 1963).

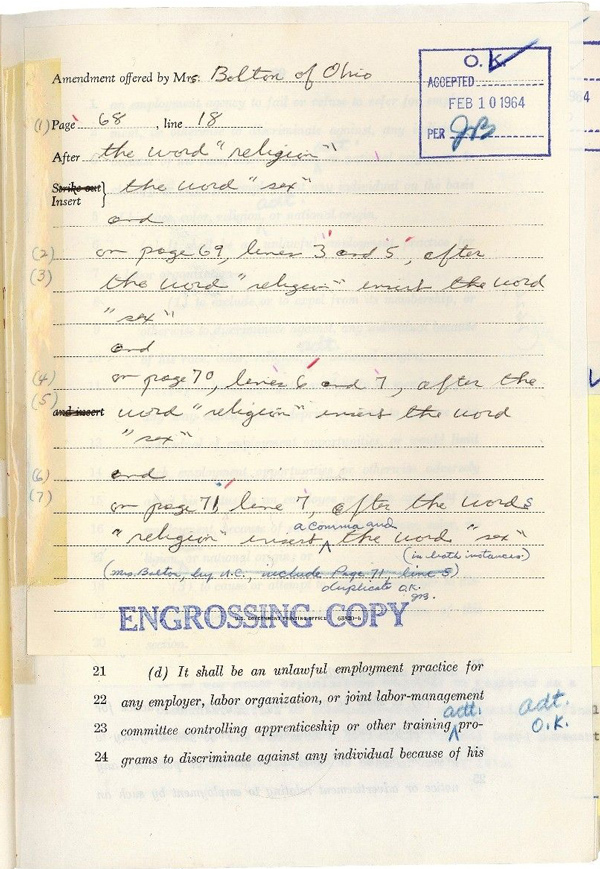

The earlier Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first law addressing the legal rights of African Americans passed by Congress since Reconstruction, had established the Civil Rights division of the Justice Department and the U.S. Civil Rights Commission to investigate claims of racial discrimination. Before the 1957 bill was passed Congress had, however, removed a provision that would have empowered the Justice Department to enforce the Brown v. Board of Education decision. A. Philip Randolph and other civil rights leaders continued to press the major political parties and presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy to enact such legislation and to outlaw segregation. The civil rights legislation that Kennedy introduced to Congress on 19 June 1963 addressed these issues, and King advocated for its passage.

In an article published after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that posed the question, “What next?” King wrote, “The hundreds of thousands who marched in Washington marched to level barriers. They summed up everything in a word—NOW. What is the content of NOW? Everything, not some things, in the President’s civil rights bill is part of NOW” (King, “In a Word—Now”).

Following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, King continued to press for the bill as did newly inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson . In his 4 January 1964 column in the New York Amsterdam News , King maintained that the legislation was “the order of the day at the great March on Washington last summer. The Negro and his compatriots for self-respect and human dignity will not be denied” (King, “A Look to 1964”).

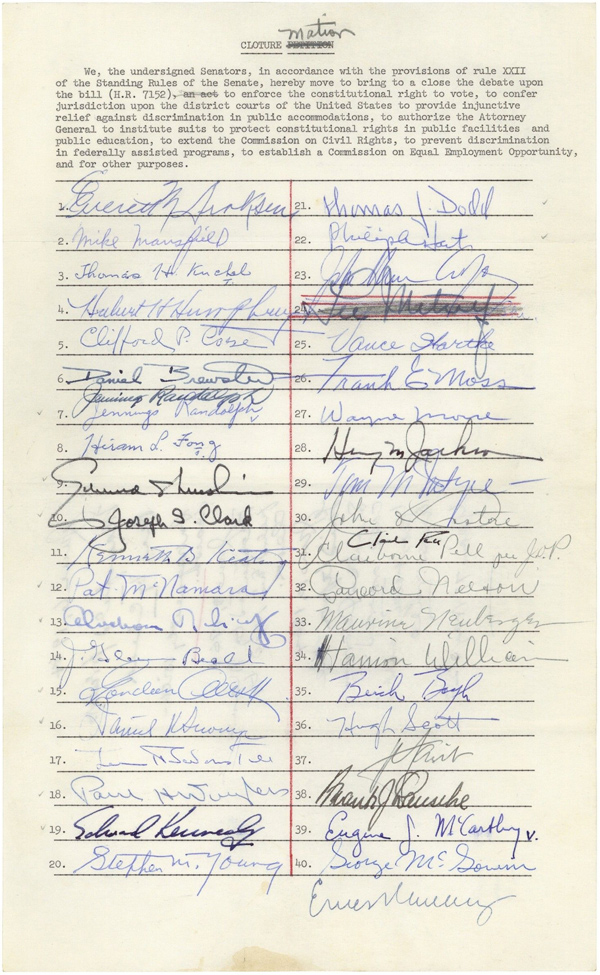

The bill passed the House of Representatives in mid-February 1964, but became mired in the Senate due to a filibuster by southern senators that lasted 75 days. When the bill finally passed the Senate, King hailed it as one that would “bring practical relief to the Negro in the South, and will give the Negro in the North a psychological boost that he sorely needs” (King, 19 June 1964). On 2 July 1964, Johnson signed the new Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law with King and other civil rights leaders present. The law’s provisions created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to address race and sex discrimination in employment and a Community Relations Service to help local communities solve racial disputes; authorized federal intervention to ensure the desegregation of schools, parks, swimming pools, and other public facilities; and restricted the use of literacy tests as a requirement for voter registration.

Carson et al., ed., Eyes on the Prize , 1991.

Kennedy, “President Kennedy’s Radio-TV Address on Civil Rights,” Congressional Quarterly (14 June 1963): 970–971.

King, “In a Word—Now,” New York Times Magazine , 29 September 1963.

King, “A Look to 1964,” New York Amsterdam News , 4 January 1964.

King, Statement on the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 19 June 1964, MLKJP-GAMK .

King to Kennedy, 11 June 1963, JFKWHCSF-MBJFK .

Kotz, Judgment Days , 2005.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most comprehensive civil rights legislation ever enacted by Congress. It contained extensive measures to dismantle Jim Crow segregation and combat racial discrimination.

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965 removed barriers to black enfranchisement in the South, banning poll taxes, literacy tests, and other measures that effectively prevented African Americans from voting.

- Segregationists attempted to prevent the implementation of federal civil rights legislation at the local level.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

Popular resistance to civil rights legislation, the voting rights act of 1965, what do you think.

- Paul S. Boyer, Promises to Keep: The United States since World War II (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 237.

- See Clay Risen, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2014); and Todd Purdum, An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014).

- See Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

- John Hope Franklin & Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans , 9th Edition (New York: McGraw Hill, 2011), 545.

- See David J. Garrow, Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015).

- See Ari Berman, Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2015).

- See Gary May, Bending Toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Intro Essay: The Civil Rights Movement

To what extent did founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice become a reality for african americans during the civil rights movement.

- I can explain the importance of local and federal actions in the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

- I can compare the goals and methods of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLS), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Malcolm X and Black Nationalism, and Black Power.

- I can explain challenges African Americans continued to face despite victories for equality and justice during the civil rights movement.

Essential Vocabulary

| The movement of millions of Black Americans from the rural South to cities in the South, Midwest, and North that occurred during the first half of the twentieth century | |

| A civil rights organization founded in 1909 with the goal of ending racial discrimination against Black Americans | |

| A civil rights organization founded in 1957 to coordinate nonviolent protest activities | |

| A student-led civil rights organization founded in 1960 | |

| A school of thought that advocated Black pride, self-sufficiency, and separatism rather than integration | |

| An action designed to prolong debate and to delay or prevent a vote on a bill | |

| A 1964 voter registration drive led by Black and white volunteers | |

| A movement emerging in the mid-1960s that sought to empower Black Americans rather than seek integration into white society | |

| A political organization founded in 1966 to challenge police brutality against the African American community in Oakland, California |

Continuing the Heroic Struggle for Equality: The Civil Rights Movement

The struggle to make the promises of the Declaration of Independence a reality for Black Americans reached a climax after World War II. The activists of the civil rights movement directly confronted segregation and demanded equal civil rights at the local level with physical and moral courage and perseverance. They simultaneously pursued a national strategy of systematically filing lawsuits in federal courts, lobbying Congress, and pressuring presidents to change the laws. The civil rights movement encountered significant resistance, however, and suffered violence in the quest for equality.

During the middle of the twentieth century, several Black writers grappled with the central contradictions between the nation’s ideals and its realities, and the place of Black Americans in their country. Richard Wright explored a raw confrontation with racism in Native Son (1940), while Ralph Ellison led readers through a search for identity beyond a racialized category in his novel Invisible Man (1952), as part of the Black quest for identity. The novel also offered hope in the power of the sacred principles of the Founding documents. Playwright Lorraine Hansberry wrote A Raisin in the Sun , first performed in 1959, about the dreams deferred for Black Americans and questions about assimilation. Novelist and essayist James Baldwin described Blacks’ estrangement from U.S. society and themselves while caught in a racial nightmare of injustice in The Fire Next Time (1963) and other works.

World War II wrought great changes in U.S. society. Black soldiers fought for a “double V for victory,” hoping to triumph over fascism abroad and racism at home. Many received a hostile reception, such as Medgar Evers who was blocked from voting at gunpoint by five armed whites. Blacks continued the Great Migration to southern and northern cities for wartime industrial work. After the war, in 1947, Jackie Robinson endured racial taunts on the field and segregation off it as he broke the color barrier in professional baseball and began a Hall of Fame career. The following year, President Harry Truman issued executive orders desegregating the military and banning discrimination in the civil service. Meanwhile, Thurgood Marshall and his legal team at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) meticulously prepared legal challenges to discrimination, continuing a decades-long effort.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund brought lawsuits against segregated schools in different states that were consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , 1954. The Supreme Court unanimously decided that “separate but equal” was “inherently unequal.” Brown II followed a year after, as the court ordered that the integration of schools should be pursued “with all deliberate speed.” Throughout the South, angry whites responded with a campaign of “massive resistance” and refused to comply with the order, while many parents sent their children to all-white private schools. Middle-class whites who opposed integration joined local chapters of citizens’ councils and used propaganda, economic pressure, and even violence to achieve their ends.

A wave of violence and intimidation followed. In 1955, teenager Emmett Till was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he was lynched after being falsely accused of whistling at a white woman. Though an all-white jury quickly acquitted the two men accused of killing him, Till’s murder was reported nationally and raised awareness of the injustices taking place in Mississippi.

In Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks (who was a secretary of the Montgomery NAACP) was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated bus. Her willingness to confront segregation led to a direct-action movement for equality. The local Women’s Political Council organized the city’s Black residents into a boycott of the bus system, which was then led by the Montgomery Improvement Association. Black churches and ministers, including Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, provided a source of strength. Despite arrests, armed mobs, and church bombings, the boycott lasted until a federal court desegregated the city buses. In the wake of the boycott, the leading ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) , which became a key civil rights organization.

Rosa Parks is shown here in 1955 with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the background. The Montgomery bus boycott was an important victory in the civil rights movement.

In 1957, nine Black families decided to send their children to Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Governor Orval Faubus used the National Guard to prevent their entry, and one student, Elizabeth Eckford, faced an angry crowd of whites alone and barely escaped. President Eisenhower was compelled to respond and sent in 1,200 paratroops from the 101st Airborne to protect the Black students. They continued to be harassed, but most finished the school year and integrated the school.

That year, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act that created a civil rights division in the Justice Department and provided minimal protections for the right to vote. The bill had been watered down because of an expected filibuster by southern senators, who had recently signed the Southern Manifesto, a document pledging their resistance to Supreme Court decisions such as Brown .

In 1960, four Black college students were refused lunch service at a local Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, and they spontaneously staged a “sit-in” the following day. Their resistance to the indignities of segregation was copied by thousands of others of young Blacks across the South, launching another wave of direct, nonviolent confrontation with segregation. Ella Baker invited several participants to a Raleigh conference where they formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and issued a Statement of Purpose. The group represented a more youthful and daring effort that later broke with King and his strategy of nonviolence.

In contrast, Malcolm X became a leading spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (NOI) who represented Black separatism as an alternative to integration, which he deemed an unworthy goal. He advocated revolutionary violence as a means of Black self-defense and rejected nonviolence. He later changed his views, breaking with the NOI and embracing a Black nationalism that had more common ground with King’s nonviolent views. Malcolm X had reached out to establish ties with other Black activists before being gunned down by assassins who were members of the NOI later in 1965.

In 1961, members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) rode segregated buses in order to integrate interstate travel. These Black and white Freedom Riders traveled into the Deep South, where mobs beat them with bats and pipes in bus stations and firebombed their buses. A cautious Kennedy administration reluctantly intervened to protect the Freedom Riders with federal marshals, who were also victimized by violent white mobs.

Malcolm X was a charismatic speaker and gifted organizer. He argued that Black pride, identity, and independence were more important than integration with whites.

King was moved to act. He confronted segregation with the hope of exposing injustice and brutality against nonviolent protestors and arousing the conscience of the nation to achieve a just rule of law. The first planned civil rights campaign was initiated by SNCC and taken over mid-campaign by King and SCLC. It failed because Albany, Georgia’s Police Chief Laurie Pritchett studied King’s tactics and responded to the demonstrations with restraint. In 1963, King shifted the movement to Birmingham, Alabama, where Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor unleashed his officers to attack civil rights protestors with fire hoses and police dogs. Authorities arrested thousands, including many young people who joined the marches. King wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail” after his own arrest and provided the moral justification for the movement to break unjust laws. National and international audiences were shocked by the violent images shown in newspapers and on the television news. President Kennedy addressed the nation and asked, “whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities . . . [If a Black person]cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?” The president then submitted a civil rights bill to Congress.

In late August 1963, more than 250,000 people joined the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in solidarity for equal rights. From the Lincoln Memorial steps, King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. He stated, “I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

After Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, President Lyndon Johnson pushed his agenda through Congress. In the early summer of 1964, a 3-month filibuster by southern senators was finally defeated, and both houses passed the historical civil rights bill. President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, banning segregation in public accommodations.

Activists in the civil rights movement then focused on campaigns for the right to vote. During the summer of 1964, several civil rights organizations combined their efforts during the “ Freedom Summer ” to register Blacks to vote with the help of young white college students. They endured terror and intimidation as dozens of churches and homes were burned and workers were killed, including an incident in which Black advocate James Chaney and two white students, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were murdered in Mississippi.

In August 1963, peaceful protesters gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial to draw attention to the inequalities and indignities African Americans suffered 100 years after emancipation. Leaders of the march are shown in the image on the bottom, with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the center.

That summer, Fannie Lou Hamer helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as civil rights delegates to replace the rival white delegation opposed to civil rights at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. Hamer was a veteran of attempts to register other Blacks to vote and endured severe beatings for her efforts. A proposed compromise of giving two seats to the MFDP satisfied neither those delegates nor the white delegation, which walked out. Cracks were opening up in the Democratic electoral coalition over civil rights, especially in the South.

Fannie Lou Hamer testified about the violence she and others endured when trying to register to vote at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Her televised testimony exposed the realities of continued violence against Blacks trying to exercise their constitutional rights.

In early 1965, the SCLC and SNCC joined forces to register voters in Selma and draw attention to the fight for Black suffrage. On March 7, marchers planned to walk peacefully from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. However, mounted state troopers and police blocked the Edmund Pettus Bridge and then rampaged through the marchers, indiscriminately beating them. SNCC leader John Lewis suffered a fractured skull, and 5 women were clubbed unconscious. Seventy people were hospitalized for injuries during “Bloody Sunday.” The scenes again shocked television viewers and newspaper readers.

The images of state troopers, local police, and local people brutally attacking peaceful protestors on “Bloody Sunday” shocked people across the country and world. Two weeks later, protestors of all ages and races continued the protest. By the time they reached the state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, their ranks had swelled to about 25,000 people.

Two days later, King led a symbolic march to the bridge but then turned around. Many younger and more militant activists were alienated and felt that King had sold out to white authorities. The tension revealed the widening division between older civil rights advocates and those younger, more radical supporters who were frustrated at the slow pace of change and the routine violence inflicted upon peaceful protesters. Nevertheless, starting on March 21, with the help of a federal judge who refused Governor George Wallace’s request to ban the march, Blacks triumphantly walked to Montgomery. On August 6, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act protecting the rights to register and vote after a Senate filibuster ended and the bill passed Congress.

The Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act did not alter the fact that most Black Americans still suffered racism, were denied equal economic opportunities, and lived in segregated neighborhoods. While King and other leaders did seek to raise their issues among northerners, frustrations often boiled over into urban riots during the mid-1960s. Police brutality and other racial incidents often triggered days of violence in which hundreds were injured or killed. There were mass arrests and widespread property damage from arson and looting in Los Angeles, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland, Chicago, and dozens of other cities. A presidential National Advisory Commission of Civil Disorders issued the Kerner Report, which analyzed the causes of urban unrest, noting the impact of racism on the inequalities and injustices suffered by Black Americans.

Frustration among young Black Americans led to the rise of a more militant strain of advocacy. In 1966, activist James Meredith was on a solo march in Mississippi to raise awareness about Black voter registration when he was shot and wounded. Though Meredith recovered, this event typified the violence that led some young Black Americans to espouse a more military strain of advocacy. On June 16, SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael and members of the Black Panther Party continued Meredith’s march while he recovered from his wounds, chanting, “We want Black Power .” Black Power leaders and members of the Black Panther Party offered a different vision for equality and justice. They advocated self-reliance and self-empowerment, a celebration of Black culture, and armed self-defense. They used aggressive rhetoric to project a more radical strategy for racial progress, including sympathy for revolutionary socialism and rejection of capitalism. While its legacy is debated, the Black Power movement raised many important questions about the place of Black Americans in the United States, beyond the civil rights movement.

After World War II, Black Americans confronted the iniquities and indignities of segregation to end almost a century of Jim Crow. Undeterred, they turned the public’s eyes to the injustice they faced and called on the country to live up to the promises of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and to continue the fight against inequality and discrimination.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- What factors helped to create the modern civil rights movement?

- How was the quest for civil rights a combination of federal and local actions?

- What were the goals and methods of different activists and groups of the civil rights movement? Complete the table below to reference throughout your analysis of the primary source documents.

| Martin Luther King, Jr., and SCLC | SNCC | Malcolm X | Black Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | | | |||||

|

| |||||

The drama of the mid-twentieth century emerged on a foundation of earlier struggles. Two are particularly notable: the NAACP’s campaign against lynching, and the NAACP’s legal campaign against segregated education, which culminated in the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision.

The NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign of the 1930s combined widespread publicity about the causes and costs of lynching, a successful drive to defeat Supreme Court nominee John J. Parker for his white supremacist and anti-union views and then defeat senators who voted for confirmation, and a skillful effort to lobby Congress and the Roosevelt administration to pass a federal anti-lynching law. Southern senators filibustered, but they could not prevent the formation of a national consensus against lynching; by 1938 the number of lynchings declined steeply. Other organizations, such as the left-wing National Negro Congress, fought lynching, too, but the NAACP emerged from the campaign as the most influential civil rights organization in national politics and maintained that position through the mid-1950s.

Houston was unabashed: lawyers were either social engineers or they were parasites. He desired equal access to education, but he also was concerned with the type of society blacks were trying to integrate. He was among those who surveyed American society and saw racial inequality and the ruling powers that promoted racism to divide black workers from white workers. Because he believed that racial violence in Depression-era America was so pervasive as to make mass direct action untenable, he emphasized the redress of grievances through the courts.

The designers of the Brown strategy developed a potent combination of gradualism in legal matters and advocacy of far-reaching change in other political arenas. Through the 1930s and much of the 1940s, the NAACP initiated suits that dismantled aspects of the edifice of segregated education, each building on the precedent of the previous one. Not until the late 1940s did the NAACP believe it politically feasible to challenge directly the constitutionality of “separate but equal” education itself. Concurrently, civil rights organizations backed efforts to radically alter the balance of power between employers and workers in the United States. They paid special attention to forming an alliance with organized labor, whose history of racial exclusion angered blacks. In the 1930s, the National Negro Congress brought blacks into the newly formed United Steel Workers, and the union paid attention to the particular demands of African Americans. The NAACP assisted the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the largest black labor organization of its day. In the 1940s, the United Auto Workers, with NAACP encouragement, made overtures to black workers. The NAACP’s successful fight against the Democratic white primary in the South was more than a bid for inclusion; it was a stiff challenge to what was in fact a regional one-party dictatorship. Recognizing the interdependence of domestic and foreign affairs, the NAACP’s program in the 1920s and 1930s promoted solidarity with Haitians who were trying to end the American military occupation and with colonized blacks elsewhere in the Caribbean and in Africa. African Americans’ support for WWII and the battle against the Master Race ideology abroad was matched by equal determination to eradicate it in America, too. In the post-war years blacks supported the decolonization of Africa and Asia.

The Cold War and McCarthyism put a hold on such expansive conceptions of civil/human rights. Critics of our domestic and foreign policies who exceeded narrowly defined boundaries were labeled un-American and thus sequestered from Americans’ consciousness. In a supreme irony, the Supreme Court rendered the Brown decision and then the government suppressed the very critique of American society that animated many of Brown ’s architects.

White southern resistance to Brown was formidable and the slow pace of change stimulated impatience especially among younger African Americans as the 1960s began. They concluded that they could not wait for change—they had to make it. And the Montgomery Bus Boycott , which lasted the entire year of 1956, had demonstrated that mass direct action could indeed work. The four college students from Greensboro who sat at the Woolworth lunch counter set off a decade of activity and organizing that would kill Jim Crow.

Elimination of segregation in public accommodations and the removal of “Whites Only” and “Colored Only” signs was no mean feat. Yet from the very first sit-in, Ella Baker , the grassroots leader whose activism dated from the 1930s and who was advisor to the students who founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), pointed out that the struggle was “concerned with something much bigger than a hamburger or even a giant-sized Coke.” Far more was at stake for these activists than changing the hearts of whites. When the sit-ins swept Atlanta in 1960, protesters’ demands included jobs, health care, reform of the police and criminal justice system, education, and the vote. (See: “An Appeal for Human Rights.” ) Demonstrations in Birmingham in 1963 under the leadership of Fred Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which was affiliated with the SCLC, demanded not only an end to segregation in downtown stores but also jobs for African Americans in those businesses and municipal government. The 1963 March on Washington, most often remembered as the event at which Dr. King proclaimed his dream, was a demonstration for “Jobs and Justice.”

Movement activists from SNCC and CORE asked sharp questions about the exclusive nature of American democracy and advocated solutions to the disfranchisement and violation of the human rights of African Americans, including Dr. King’s nonviolent populism, Robert Williams’ “armed self-reliance,” and Malcolm X’s incisive critiques of worldwide white supremacy, among others. (See: Dr. King, “Where Do We Go from Here?” ; Robert F. Williams, “Negroes with Guns” ; and Malcolm X, “Not just an American problem, but a world problem.” ) What they proposed was breathtakingly radical, especially in light of today’s political discourse and the simplistic ways it prefers to remember the freedom struggle. King called for a guaranteed annual income, redistribution of the national wealth to meet human needs, and an end to a war to colonize the Vietnamese. Malcolm X proposed to internationalize the black American freedom struggle and to link it with liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Thus the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s was not concerned exclusively with interracial cooperation or segregation and discrimination as a character issue. Rather, as in earlier decades, the prize was a redefinition of American society and a redistribution of social and economic power.

Guiding Student Discussion

Students discussing the Civil Rights Movement will often direct their attention to individuals’ motives. For example, they will question whether President Kennedy sincerely believed in racial equality when he supported civil rights or only did so out of political expediency. Or they may ask how whites could be so cruel as to attack peaceful and dignified demonstrators. They may also express awe at Martin Luther King’s forbearance and calls for integration while showing discomfort with Black Power’s separatism and proclamations of self-defense. But a focus on the character and moral fiber of leading individuals overlooks the movement’s attempts to change the ways in which political, social, and economic power are exercised. Leading productive discussions that consider broader issues will likely have to involve debunking some conventional wisdom about the Civil Rights Movement. Guiding students to discuss the extent to which nonviolence and racial integration were considered within the movement to be hallowed goals can lead them to greater insights.

Nonviolence and passive resistance were prominent tactics of protesters and organizations. (See: SNCC Statement of Purpose and Jo Ann Gibson Robinson’s memoir, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It. ) But they were not the only ones, and the number of protesters who were ideologically committed to them was relatively small. Although the name of one of the important civil rights organizations was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, its members soon concluded that advocating nonviolence as a principle was irrelevant to most African Americans they were trying to reach. Movement participants in Mississippi, for example, did not decide beforehand to engage in violence, but self-defense was simply considered common sense. If some SNCC members in Mississippi were convinced pacifists in the face of escalating violence, they nevertheless enjoyed the protection of local people who shared their goals but were not yet ready to beat their swords into ploughshares.

Armed self-defense had been an essential component of the black freedom struggle, and it was not confined to the fringe. Returning soldiers fought back against white mobs during the Red Summer of 1919. In 1946, World War Two veterans likewise protected black communities in places like Columbia, Tennessee, the site of a bloody race riot. Their self-defense undoubtedly brought national attention to the oppressive conditions of African Americans; the NAACP’s nationwide campaign prompted President Truman to appoint a civil rights commission that produced To Secure These Rights , a landmark report that called for the elimination of segregation. Army veteran Robert F. Williams, who was a proponent of what he called “armed self-reliance,” headed a thriving branch of the NAACP in Monroe, North Carolina, in the early 1950s. The poet Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” dramatically captures the spirit of self-defense and violence.

Often, deciding whether violence is “good” or “bad,” necessary or ill-conceived depends on one’s perspective and which point of view runs through history books. Students should be encouraged to consider why activists may have considered violence a necessary part of their work and what role it played in their overall programs. Are violence and nonviolence necessarily antithetical, or can they be complementary? For example the Black Panther Party may be best remembered by images of members clad in leather and carrying rifles, but they also challenged widespread police brutality, advocated reform of the criminal justice system, and established community survival programs, including medical clinics, schools, and their signature breakfast program. One question that can lead to an extended discussion is to ask students what the difference is between people who rioted in the 1960s and advocated violence and the participants in the Boston Tea Party at the outset of the American Revolution. Both groups wanted out from oppression, both saw that violence could be efficacious, and both were excoriated by the rulers of their day. Teachers and students can then explore reasons why those Boston hooligans are celebrated in American history and whether the same standards should be applied to those who used arms in the 1960s.

An important goal of the Civil Rights Movement was the elimination of segregation. But if students, who are now a generation or more removed from Jim Crow, are asked to define segregation, they are likely to point out examples of individual racial separation such as blacks and whites eating at different cafeteria tables and the existence of black and white houses of worship. Like most of our political leaders and public opinion, they place King’s injunction to judge people by the content of their character and not the color of their skin exclusively in the context of personal relationships and interactions. Yet segregation was a social, political, and economic system that placed African Americans in an inferior position, disfranchised them, and was enforced by custom, law, and official and vigilante violence.

The discussion of segregation should be expanded beyond expressions of personal preferences. One way to do this is to distinguish between black and white students hanging out in different parts of a school and a law mandating racially separate schools, or between black and white students eating separately and a laws or customs excluding African Americans from restaurants and other public facilities. Put another way, the civil rights movement was not fought merely to ensure that students of different backgrounds could become acquainted with each other. The goal of an integrated and multicultural America is not achieved simply by proximity. Schools, the economy, and other social institutions needed to be reformed to meet the needs for all. This was the larger and widely understood meaning of the goal of ending Jim Crow, and it is argued forcefully by James Farmer in “Integration or Desegregation.”

A guided discussion should point out that many of the approaches to ending segregation did not embrace integration or assimilation, and students should become aware of the appeal of separatism. W. E. B. Du Bois believed in what is today called multiculturalism. But by the mid-1930s he concluded that the Great Depression, virulent racism, and the unreliability of white progressive reformers who had previously expressed sympathy for civil rights rendered an integrated America a distant dream. In an important article, “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?” Du Bois argued for the strengthening of black pride and the fortification of separate black schools and other important institutions. Black communities across the country were in severe distress; it was counterproductive, he argued, to sacrifice black schoolchildren at the altar of integration and to get them into previously all-white schools, where they would be shunned and worse. It was far better to invest in strengthening black-controlled education to meet black communities’ needs. If, in the future, integration became a possibility, African Americans would be positioned to enter that new arrangement on equal terms. Du Bois’ argument found echoes in the 1960s writing of Stokely Carmichael ( “Toward Black Liberation” ) and Malcolm X ( “The Ballot or the Bullet” ).

Scholars Debate

Any brief discussion of historical literature on the Civil Rights Movement is bound to be incomplete. The books offered—a biography, a study of the black freedom struggle in Memphis, a brief study of the Brown decision, and a debate over the unfolding of the movement—were selected for their accessibility variety, and usefulness to teaching, as well as the soundness of their scholarship.

Walter White: Mr. NAACP , by Kenneth Robert Janken, is a biography of one of the most well known civil rights figure of the first half of the twentieth century. White made a name for himself as the NAACP’s risk-taking investigator of lynchings, riots, and other racial violence in the years after World War I. He was a formidable persuader and was influential in the halls of power, counting Eleanor Roosevelt, senators, representatives, cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, union leaders, Hollywood moguls, and diplomats among his circle of friends. His style of work depended upon rallying enlightened elites, and he favored a placing effort into developing a civil rights bureaucracy over local and mass-oriented organizations. Walter White was an expert in the practice of “brokerage politics”: During decades when the majority of African Americans were legally disfranchised, White led the organization that gave them an effective voice, representing them and interpreting their demands and desires (as he understood them) to those in power. Two examples of this were highlighted in the first part of this essay: the anti-lynching crusade, and the lobbying of President Truman, which resulted in To Secure These Rights . A third example is his essential role in producing Marian Anderson’s iconic 1939 Easter Sunday concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which drew the avid support of President Roosevelt and members of his administration, the Congress, and the Supreme Court. His style of leadership was, before the emergence of direct mass action in the years after White’s death in 1955, the dominant one in the Civil Rights Movement.

There are many excellent books that study the development of the Civil Rights Movement in one locality or state. An excellent addition to the collection of local studies is Battling the Plantation Mentality , by Laurie B. Green, which focuses on Memphis and the surrounding rural areas of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi between the late 1930s and 1968, when Martin Luther King was assassinated there. Like the best of the local studies, this book presents an expanded definition of civil rights that encompasses not only desegregation of public facilities and the attainment of legal rights but also economic and political equality. Central to this were efforts by African Americans to define themselves and shake off the cultural impositions and mores of Jim Crow. During WWII, unionized black men went on strike in the defense industry to upgrade their job classifications. Part of their grievances revolved around wages and working conditions, but black workers took issue, too, with employers’ and the government’s reasoning that only low status jobs were open to blacks because they were less intelligent and capable. In 1955, six black female employees at a white-owned restaurant objected to the owner’s new method of attracting customers as degrading and redolent of the plantation: placing one of them outside dressed as a mammy doll to ring a dinner bell. When the workers tried to walk off the job, the owner had them arrested, which gave rise to local protest. In 1960, black Memphis activists helped support black sharecroppers in surrounding counties who were evicted from their homes when they initiated voter registration drives. The 1968 sanitation workers strike mushroomed into a mass community protest both because of wage issues and the strikers’ determination to break the perception of their being dependent, epitomized in their slogan “I Am a Man.” This book also shows that not everyone was able to cast off the plantation mentality, as black workers and energetic students at LeMoyne College confronted established black leaders whose positions and status depended on white elites’ sufferance.

Brown v. Board of Education: A Brief History with Documents , edited by Waldo E. Martin, Jr., contains an insightful 40-page essay that places both the NAACP’s legal strategy and 1954 Brown decision in multiple contexts, including alternate approaches to incorporating African American citizens into the American nation, and the impact of World War II and the Cold War on the road to Brown . The accompanying documents affirm the longstanding black freedom struggle, including demands for integrated schools in Boston in 1849, continuing with protests against the separate but equal ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896, and important items from the NAACP’s cases leading up to Brown . The documents are prefaced by detailed head notes and provocative discussion questions.

Debating the Civil Rights Movement , by Steven F. Lawson and Charles Payne, is likewise focused on instruction and discussion. This essay has largely focused on the development of the Civil Rights Movement from the standpoint of African American resistance to segregation and the formation organizations to fight for racial, economic, social, and political equality. One area it does not explore is how the federal government helped to shape the movement. Steven Lawson traces the federal response to African Americans’ demands for civil rights and concludes that it was legislation, judicial decisions, and executive actions between 1945 and 1968 that was most responsible for the nation’s advance toward racial equality. Charles Payne vigorously disagrees, focusing instead on the protracted grassroots organizing as the motive force for whatever incomplete change occurred during those years. Each essay runs about forty pages, followed by smart selections of documents that support their cases.

Kenneth R. Janken is Professor of African and Afro-American Studies and Director of Experiential Education, Office of Undergraduate Curricula at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of White: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP and Rayford W. Logan and the Dilemma of the African American Intellectual . He was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 2000-01.

Illustration credits

To cite this essay: Janken, Kenneth R. “The Civil Rights Movement: 1919-1960s.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. DATE YOU ACCESSED ESSAY. <https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1917beyond/essays/crm.htm>

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search

TeacherServe® Home Page National Humanities Center 7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535 Copyright © National Humanities Center. All rights reserved. Revised: April 2010 nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Public Opinion on Civil Rights: Reflections on the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Likely the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ushered in a new era in American civil rights as discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin was outlawed. By signing the law into effect on July 2, 1964, President Johnson also paved the way for additional school desegregation and the prohibition of discrimination in public places and within federal agencies. Public opinion polls held in the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research archives reveal changing attitudes about race in the U.S., exposing how divisive racial issues were at the time, how much improvement there has been since the Act – and how very far the country still has to go.

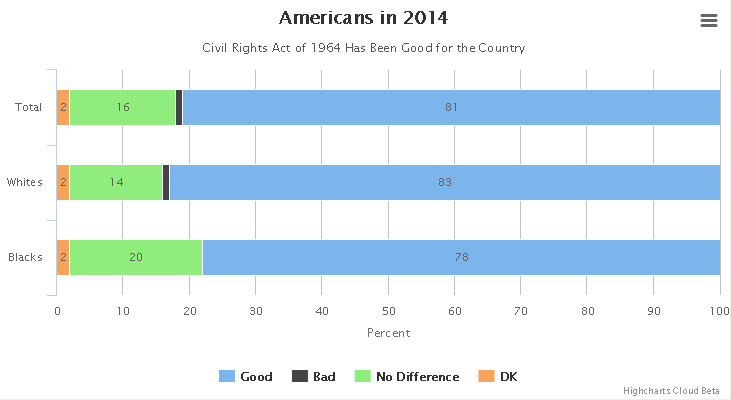

Civil Rights Today

The effects of the Civil Rights Act, and improvements in race relations more generally, are apparent in a March 2014 CBS poll, which finds that 8 in 10 Americans think the act has had a positive effect on the country and only 1% thinking it has been negative. Additionally, the poll also found that 60% of whites and 55% of blacks think that the state of race relations in America is good.

However, these fairly positive assessments are relatively new. The U.S. public has been asked o give their overall assessment of race relations in the U.S. regularly since 1990. A low of 24% of whites and 21% of blacks said race relations were generally good in 1992, the year of the Rodney King riots. Not until the year 2000 did a majority of either whites or blacks say race relations were generally good. Public opinion toward minority civil rights was even more unfavorable in the past. According to Paul Herrnson, a Professor of Political Science at the University of Connecticut, “Issues related to race relations and civil rights challenged Americans prior to and during the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, throughout the Civil War period and the sixties, and they continue today. Despite the progress that has been made, many have yet to fully embrace the notion that all Americans are entitled to the same civil rights and liberties.”

Source: CBS News Poll March 2014: “Overall, do you think passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was mostly good for the country, or mostly bad for the country, or don’t you think it made much difference?”

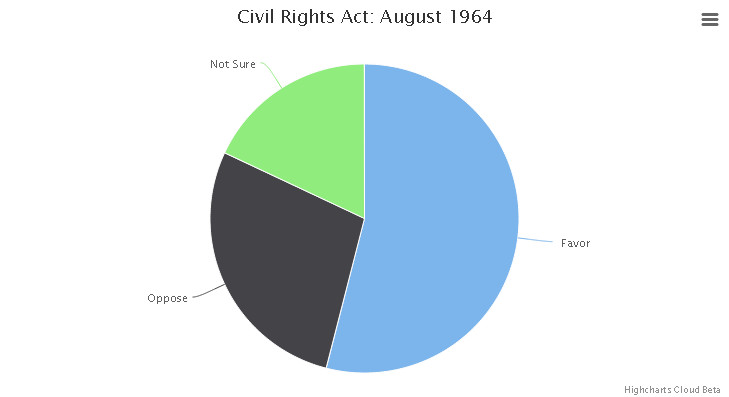

1960s Climate for the Passage of the Civil Rights Act

Race relations in the first half of the 1960s were toxic in many parts of the country. These years saw numerous sit-ins, marches, protests, and riots in the deep south from Greensboro, North Carolina to Birmingham, Alabama as well as forced integration at the University of Mississippi and racial violence by white supremacist leagues in Neshoba County, Mississippi. In 1963, the March on Washington saw the now famous “I Have a Dream” speech be given by Martin Luther King Jr. and in the following year, the poll tax was abolished through the 24th Amendment. A sign of the times, in 1963, a Gallup poll found that 78% of white people would leave their neighborhood if many black families moved in. When it comes to MLK’s march on Washington, 60% had an unfavorable view of the march, stating that they felt it would cause violence and would not accomplish anything.

Source: Harris Survey August 1964: “Looking back on it now, would you say that you approve or disapprove of the civil rights bill that was passed by Congress last month?”

In the months leading up to the bill being signed on July 2, there was support for the act, but still a third opposed the bill. One month after its passage, when the implementation phase began, support was just more than 50%, with nearly 1 in five voicing uncertainty about the bill. The civil rights movement itself was viewed with suspicion by many Americans. In 1965, in the midst of the Cold War, a plurality of Americans believed that civil rights organizations had been infiltrated by communists, with almost a fifth of the country unsure as to whether or not they had been compromised.

Source: Institute for International Social Research and the Gallup Organization, Hopes and Fears September 1964: “Most of the organizations pushing for civil rights have been infiltrated by the communists and are now dominated by communist trouble-makers. Do you agree with the statement or not?”

The legacy of the Civil Rights Act: 1980s and 1900s

An examination of the legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 indicates that it has taken several decades for the Act’s effects to be fully felt. The 1980s saw that new generations of Americans believed that the Civil Rights Act had indeed worked. Ninety-two percent of respondents in a 1984 Attitudes and Opinions of Black Americans Poll stated that the civil rights movement had improved the lives of the black community.

However, this is not to say that this period was without some controversy in civil rights. The drumbeat for school integration through busing began in the 1970s and the issue persisted through the 1990s. While support increased nationally from 19% in 1972 to 35% in 1996, the issue reflects a fragile state of race relations at the time as well as a significant divide between the races, something that a quarter of a century did not solve. Eight-six percent of whites were opposed to busing in the early 1970s and by 1996 that had shifted to two-thirds opposed. Among black respondents a majority in nearly every year favored busing and only 39% opposed in 1996.

Source: National Opinion Research Center, General Social Survey 1972-1996: “In general, do you favor or oppose the busing of Negro and white school children from one school district to another?”

Race Relations over Time

The 1990s saw the issue of civil rights once again bubble to the surface of American society as race riots erupted in Los Angeles over the Rodney King incident in which white police officers were acquitted after being videotaped beating a black man. President Bush signed a new civil rights act into effect in 1991 which shored up measures to prevent discrimination in the workplace. This act coincided with a Gallup Poll in June 1991 finding that 58% believed the black community had been helped by civil rights legislation. As the thirty year anniversary approached of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a Gallup/ CNN / USA Today Poll in 1993 found that 65% believed the civil rights movement had had a significant impact on American society. By 2008, the Pew Research Center found 53% of whites and 59% of Black Americans saying that “the civil rights movement is still having a major impact on American society.”

Source: CBS News/New York Times, May 1990-March 2014: “Do you think race relations in the United States are generally good or generally bad?”

Polls on the state of race relations in the country, as a whole, suggest that things have been improving since the general question was first asked in May 1990, albeit not a steady incline. Those who claim relations are bad have declined substantially since a high point in 1992 at 68%, during the Rodney King riots. Looking at these surveys by race, the trend indicates that whites and blacks alike believe race relations have been improving over the last twenty years. However, there still exists a gap between the races with whites believing there to be a better state of race relations than blacks. In 2011 there was a 30 point gap between the two groups, but by 2014 the margin had narrowed to its closest point since 1992. As of March 2014, 60% of whites and 55% of blacks believe race relations to be good. According to Herrnson, “Although things have been trending in a positive direction, the evidence suggests that change comes slowly and public opinion is sensitive to politics and other events.”

Employment Opportunities

Polls measuring opinion on employment opportunities for whites and blacks over time document the different views of the races. The Gallup Organization has periodically asked a question comparing the opportunities that blacks have at attaining jobs compared to whites. The results over time show an even greater gap than exists on the general view of race relations in the country—since 1978 blacks have consistently been much more likely to say they do not have the same opportunities as whites than the general public.

Source: Gallup Organization, 1978-2011: “In general, do you think blacks have as good a chance as white people in your community to get any kind of job for which they are qualified, or don’t you think they have as good a chance?”

In the latter part of the 2000s, America once again questioned whether it was ready for a black president. With Barack Obama running on behalf of the Democratic Party, the time appeared to be right, and public opinion data backed up this sentiment. Support for voting for a black candidate had been steadily rising for several decades and in 2008, history was made. With public opinion surveys conducted since 1996 reporting 9 in 10 Americans would vote for a black candidate if they were qualified, Barack Obama won the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections in what many have considered a significant step forward in race relations. An outcome that would have been simply impossible in 1964 when the Civil Rights Act was first passed had now become a reality.

On the eve of the 50th anniversary of the act, surveys conducted in March 2014 by CBS News found that 52% of America believes that we can totally eliminate racial prejudice and discrimination in the long run and that 78% think the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is an important historical event. But perhaps most tellingly, CBS News found that 84% of whites and 83% of blacks believed that the act had made life better for blacks in the United States, while only 2% thought it had made life worse. These statistics serve to reaffirm the legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Far from forgotten or relegated to the history books, the act is remembered for the hope and change it brought to a country gripped by racial tensions.

- Roper Center iPOLL Databank Surveys including polling data from CBS News, CNN, Gallup Organization, Pew Research Center, New York Times, Institute for International Social Research, USA Today

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/civil-rights-act/

Date Published: July 2, 2014

Join Our Newsletter

Sign up for the Data Dive newsletter with quarterly news, data stories and more. Read our updated privacy policy here.

Debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- June 11, 1963

- March 18, 1964

Introduction

Spurred by protests and violence in Birmingham and elsewhere, as well as growing signs of Black militancy, President Kennedy decided to submit a civil rights law to Congress. On June 11, 1963, he gave the speech excerpted below to explain to the American people the need for the law and to ask for their support. On the day Kennedy gave the speech, Governor George Wallace (1919–1998) of Alabama made a show of blocking a Black student from registering at the University of Alabama. It was also the day that a white supremacist shot Medgar Evers (1925–1963), the head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people in Mississippi.

On June 19, Kennedy sent the civil rights bill to Congress. Opponents objected to various provisions, including equal access to public accommodations, but also to what they felt was its unconstitutional extension of federal power (Debate on the Civil Rights Act). Supporters organized a March on Washington in August 1963, at which Martin Luther King gave his now famous “ I Have a Dream” speech . Opposition in Congress was sufficient, however, to prevent passage of the law (Debate on the Civil Rights Act). When Lyndon Johnson became president following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, he pushed for the new law, in part as a memorial to Kennedy. The law was passed July 2, 1964. Following a civil rights law passed in 1957, it was only the second such law to pass Congress since 1875. The bill had wide reach, for example requiring equal access provisions in all public accommodations, excluding only private clubs. In both its provisions and its use of federal power, the law achieved many of the objectives laid out in President Truman’s 1947 report on civil rights .

A motel in Atlanta, Georgia challenged the constitutionality of the public accommodation portion of the bill. The case, Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States , reached the Supreme Court, which decided in December 1964 that the provision was a constitutional exercise of the federal government’s power to regulate interstate commerce. Attorneys General from Florida and Virginia had filed briefs urging that the lower court decision affirming the law be reversed, while attorneys general from California, Massachusetts and New York had filed briefs urging that it be upheld.

Source: John F. Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights,” June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, White House Audio Collections, 1961–1963, WH-194-001. Available online from Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project , https://goo.gl/2Pb6gt; Originally Broadcast on CBS Reports: Filibuster—Birth Struggle of a Law, March 18, 1964. Available at The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom , Library of Congress, https://goo.gl/HoS9YC .

President John F. Kennedy, Report to the American People on Civil Rights, June 11, 1963

Good evening, my fellow citizens:

This afternoon, following a series of threats and defiant statements, the presence of Alabama National Guardsmen was required on the University of Alabama to carry out the final and unequivocal order of the United States District Court of the Northern District of Alabama. That order called for the admission of two clearly qualified young Alabama residents who happened to have been born Negro.

That they were admitted peacefully on the campus is due in good measure to the conduct of the students of the University of Alabama, who met their responsibilities in a constructive way.

I hope that every American, regardless of where he lives, will stop and examine his conscience about this and other related incidents. This Nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds. It was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.

Today we are committed to a worldwide struggle to promote and protect the rights of all who wish to be free. And when Americans are sent to Vietnam or West Berlin, we do not ask for whites only. It ought to be possible, therefore, for American students of any color to attend any public institution they select without having to be backed up by troops.

It ought to be possible for American consumers of any color to receive equal service in places of public accommodation, such as hotels and restaurants and theaters and retail stores, without being forced to resort to demonstrations in the street, and it ought to be possible for American citizens of any color to register and to vote in a free election without interference or fear of reprisal.

It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color. In short, every American ought to have the right to be treated as he would wish to be treated, as one would wish his children to be treated. But this is not the case.

The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the Nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day, one-third as much chance of completing college, one-third as much chance of becoming a professional man, twice as much chance of becoming unemployed, about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year, a life expectancy which is 7 years shorter, and the prospects of earning only half as much.

This is not a sectional issue. Difficulties over segregation and discrimination exist in every city, in every State of the Union, producing in many cities a rising tide of discontent that threatens the public safety. Nor is this a partisan issue. In a time of domestic crisis men of good will and generosity should be able to unite regardless of party or politics. This is not even a legal or legislative issue alone. It is better to settle these matters in the courts than on the streets, and new laws are needed at every level, but law alone cannot make men see right.

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?

One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it, and we cherish our freedom here at home, but are we to say to the world, and much more importantly, to each other that this is a land of the free except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens except Negroes; that we have no class or cast system, no ghettoes, no master race except with respect to Negroes?

Now the time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise. The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or state or legislative body can prudently choose to ignore them.

The fires of frustration and discord are burning in every city, North and South, where legal remedies are not at hand. Redress is sought in the streets, in demonstrations, parades, and protests which create tensions and threaten violence and threaten lives.

We face, therefore, a moral crisis as a country and as a people. It cannot be met by repressive police action. It cannot be left to increased demonstrations in the streets. It cannot be quieted by token moves or talk. It is a time to act in the Congress, in your State and local legislative body and, above all, in all of our daily lives. . . .

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law. The Federal judiciary has upheld that proposition in a series of forthright cases. The executive branch has adopted that proposition in the conduct of its affairs, including the employment of Federal personnel, the use of Federal facilities, and the sale of federally financed housing.

But there are other necessary measures which only the Congress can provide, and they must be provided at this session. The old code of equity law under which we live commands for every wrong a remedy, but in too many communities, in too many parts of the country, wrongs are inflicted on Negro citizens and there are no remedies at law. Unless the Congress acts, their only remedy is in the street.

I am, therefore, asking the Congress to enact legislation giving all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public—hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments.

This seems to me to be an elementary right. Its denial is an arbitrary indignity that no American in 1963 should have to endure, but many do. . . .

I am also asking Congress to authorize the Federal Government to participate more fully in lawsuits designed to end segregation in public education. We have succeeded in persuading many districts to desegregate voluntarily. Dozens have admitted Negroes without violence. Today a Negro is attending a state-supported institution in every one of our 50 States, but the pace is very slow. . . .

Other features will be also requested, including greater protection for the right to vote. But legislation, I repeat, cannot solve this problem alone. It must be solved in the homes of every American in every community across our country.

In this respect, I want to pay tribute to those citizens North and South who have been working in their communities to make life better for all. They are acting not out of a sense of legal duty but out of a sense of human decency.

Like our soldiers and sailors in all parts of the world, they are meeting freedom’s challenge on the firing line, and I salute them for their honor and their courage.

My fellow Americans, this is a problem which faces us all—in every city of the North as well as the South. Today there are Negroes unemployed, two or three times as many compared to whites, inadequate in education, moving into the large cities, unable to find work, young people particularly out of work without hope, denied equal rights, denied the opportunity to eat at a restaurant or lunch counter or go to a movie theater, denied the right to a decent education, denied almost today the right to attend a state university even though qualified. It seems to me that these are matters which concern us all, not merely Presidents or Congressmen or Governors, but every citizen of the United States.

This is one country. It has become one country because all of us and all the people who came here had an equal chance to develop their talents. . . .

Therefore, I am asking for your help in making it easier for us to move ahead and to provide the kind of equality of treatment which we would want ourselves; to give a chance for every child to be educated to the limit of his talents.

As I have said before, not every child has an equal talent or an equal ability or an equal motivation, but they should have the equal right to develop their talent and their ability and their motivation, to make something of themselves.

We have a right to expect that the Negro community will be responsible, will uphold the law, but they have a right to expect that the law will be fair, that the Constitution will be color blind, as Justice Harlan said at the turn of the century. [1]

This is what we are talking about and this is a matter which concerns this country and what it stands for, and in meeting it I ask the support of all our citizens.

Thank you very much.

Senator Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) and Senator Strom Thurmond (D–SC), Debate on the Civil Rights Act, March 18, 1964 [2]

Senator Hubert Humphry:

We simply have to face up to this question: Are we as a nation now ready to guarantee equal protection of the laws as declared in our Constitution to every American regardless of his race, his color, or his creed? The time has arrived for this nation to create a framework of law in which we can resolve our problems honorably and peacefully. Each American knows that the promises of freedom and equal treatment found in the Constitution and the laws of this country are not being fulfilled for millions of our Negro citizens and for some other minority groups. Deep in our heart we know, we know that such denials of civil rights, which we have heard about, which we have witnessed, are still taking place today. And we know that as long as freedom and equality is denied to anyone, it in a sense weakens all of us. There is indisputable evidence that fellow Americans who happen to be Negro have been denied the right to vote in a flagrant fashion. And we know that fellow Americans who happen to be Negro have been denied equal access to places of public accommodation, denied in their travels the chance for a place to rest and to eat and to relax. We know that one decade after the Supreme Court’s decision declaring school segregation to be unconstitutional that less than two percent of the Southern school districts are desegregated. And we know that Negroes do not enjoy equal employment opportunities. Frequently, they are the last to be hired and the first to be fired. Now the time has come for us to correct these evils, and the civil rights bill before the Senate is designed for that purpose. It is moderate, it is reasonable, it is well designed. It was passed by the House 290 to 130. It is bi-partisan, and I think it will help give us the means to help secure, for example, the right to vote for all of our people, and it will give us the means to make possible the admittance to school rooms of children regardless of their race. And it will make sure that no American will have to suffer the indignity of being refused service at a public place. This passage of the civil rights bill, to me, is one of the great moral challenges of our time. This is not a partisan issue, this is not a sectional issue, this is, in essence, a national issue, and it is a moral issue. And it must be won by the American people.

Senator Strom Thurmond:

Mr. Sevareid [3] and my colleague, Senator Humphry: This bill, in order to bestow preferential rights on a favored few, who vote in block, would sacrifice the Constitutional rights of every citizen, and would concentrate in the national government arbitrary powers, unchained by laws, to suppress the liberty of all. This bill makes a shambles of Constitutional guarantees and the Bill of Rights. It permits a man to be jailed and fined without a jury trial. It empowers the national government to tell each citizen who must be allowed to enter upon and use his property without any compensation or due process of law as guaranteed by the Constitution. This bill would take away the rights of individuals and give to government the power to decide who is to be hired, fired and promoted in private businesses. This bill would take away the right of individuals and give to government the power to abolish the seniority rule in labor unions and in apprenticeship programs. This bill would abandon the principle of a government of laws in favor of a government of men. It would give the power in government to government bureaucrats to decide what is discrimination. This bill would open wide the door for political favoritism with federal funds. It would vest the power in various bureaucrats to give or withhold grants, loans, and contracts on the basis of who, in the bureaucrats’ discretion, is guilty of the undefined crime of discrimination. It is because of these and other radical departures from our Constitutional system that the attempt is being made to railroad this bill through Congress without following normal procedures. [4] It was only after lawless riots and demonstrations sprang up all over the country that the administration, after two years in office, sent this bill to Congress where it has been made even worse. This bill is intended to appease those waging a vicious campaign of civil disobedience. The leaders of the demonstrations have already stated that passage of the bill will not stop the mobs. Submitting to intimidation will only encourage further mob violence to gain preferential treatment. The issue is whether the Senate will pay the high cost of sacrificing a precious portion of each and every individual’s Constitutional rights in a vain effort to satisfy the demands of the mob. The choice is between law and anarchy. What shall rule these United States: the Constitution or the mob?

- 1. Kennedy referred to Justice John Marshall Harlan’s (1833-1911) dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In that case, the majority of the court ruled that separate facilities for whites and blacks could be considered equal; Harlan dissented, on the grounds that the law should not recognize race.