Why Columbus Day Is Worth Defending and Celebrating

Among the federal holidays, Columbus Day has become one of the least honored, partially due to controversy about misdeeds associated with colonization. In fact, Columbus never set foot on or came close to any territory that later became part of the continental United States.

The history of Christopher Columbus is actually less messy and more consequential than many of the other heroes of our national holidays. There is not only a great deal to celebrate in Columbus, but the man embodied a range of attributes that are necessary to solving many of our contemporary problems and even saving our country from further decline and collapse resulting from group think, corruption and abuse of power.

The American story began with the seafaring discovery momentum created by Columbus’s feat of sailing from Europe some 4,000 miles south and west across the Atlantic Ocean in the late 15 th century. His quest was twofold: to find a western passage to the Spice Islands and India, and second, to carry the good news of Jesus the savior to people in new parts of the world.

Columbus had grown up in a working-class family and his life was one of hardship, punctuated by near death and failures that would have been the demise of most ordinary people. If he had not been a man of character and determination with deep faith in God, self-confidence to ignore critics, and go against the crowd and remain steadfast in his vision and his calling, he never could have accomplished what he did, which was of course the discovery of the New World of the Western Hemisphere.

Columbus left voluminous writings that bear witness to what motivated him to do what he did. Born and raised in Genoa, Italy, he was the consummate self-made man who shipped out at an early age. Experiencing the militant face of Islam at the eastern end of the Mediterranean that created a blockade to Europe’s important overland trade with the Orient, he knew that finding a western sea route would have far-reaching benefits.

Columbus faced death when the Flemish-flagged ship on which he was crew was attacked and sunk off the coast of Portugal. But for a seafarer with his ambition and vision, as fate would have it, there was no better place to wash up than on the shore of Portugal, a nation that had developed the world’s most advanced tools of navigation and map-making. In Portugal, Columbus’s exposure to celestial navigation further confirmed his confidence to sail west across the Atlantic and find a trade route to India and the Spice Islands. By his late 30s he felt “called,” writing in his diary, “It was the Lord who put into my mind, [and] I could feel his hand upon me…that it would be possible to sail from here to the Indies.”

Recognizing that such an undertaking would need state sponsorship, Columbus and his brother spent the next six years traipsing across Europe seeking support from sovereignties of the leading maritime countries, only to find rejection and ridicule. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain had turned down Columbus several times. But because of his seafaring skills, conviction in his vision of a westward passage, and his bravery and willingness to lead an armed flotilla to rescue the Holy Sepulcher from Muslim hands in the eastern Mediterranean, they had a change of heart toward Columbus.

Few years in history have been punctuated by such pivotal events as what happened in 1492. It was in that year that Christendom—still suffering from the loss of Constantinople to the Muslim Turks 40 years prior—drove Islam out of Spain and Europe with Isabella and Ferdinand playing the pivotal role. They then decided to support Christian expansion and back the exploration and evangelistic expedition of Columbus.

In his first voyage of three ships—the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria—after being at sea for nearly two months Columbus faced an anxious crew, who believed landfall should have been made by week four or five. The situation became mutinous with threats to heave Columbus overboard if he did not agree to their demands to turn back. Recognizing that he could hardly restrain let alone punish his mutinous crew given that there were 40 of them against only one of him, Columbus turned to God. In a letter that has been preserved among his personal historical records, Columbus wrote that God inspired him to make a deal with his Spanish crew and stake his life on it. He asked for three more days, and if land was not sighted, the crew could do with him as they wished.

As fate would have it, in the early morning hours of the third day on October 12, under the light of the moon and the stars, the lookout from the ship Pinta, gave the long-awaited signal of sighting land. Assuming it was an island to the east of India or perhaps China, Columbus had no idea that he was about to discover a new part of the world—the outskirts of a massive continent—far from the Orient.

Today’s “woke” culture, which has held Columbus accountable for the chain of disasters that followed in his wake in the Caribbean and South America is not only unfair to him, but it overlooks the essence of the man. Not of Spanish culture, Columbus was at heart a simple but ambitious individualist—a seafaring explorer and evangelist. He had neither interest in founding colonies nor was he an effective leader and administrator of strong-headed hidalgos that undertook setting up colonial outposts at the behest of Isabella.

Columbus’s perseverance and courage in his transatlantic feat in crossing a vast ocean inspired successors from northern Europe who had been transformed by the Protestant Reformation with the ideas of equality and freedom. They would set out to pursue a new life in a new world, ultimately establishing 13 different colonies in coastal North America.

Suffering injustice from Great Britain, those colonists reluctantly banded together to fight for independence. Over the six years of the Revolutionary War they lost more battles than they won. But like the course of Columbus, George Washington’s persistence, courage and faith in God empowered an underequipped and underfunded colonial army to get to final victory and achieve independence. That in turn enabled the founding of a new nation, unlike any other—one based on the revolutionary idea that people’s life, liberty and pursuit of happiness were inviolable because those rights came from God and not man or the state.

Seen from the big picture, Columbus Day is worth keeping and honoring for the simple reason that it celebrates beliefs and qualities of character that are foundational to America. It could even be said that Columbus Day is the holiday that commemorates the human character, attitudes and choice of action that made the other American holidays possible.

- cancel culture

- Christopher Columbus

- Columbus Day

- western culture

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Columbus Day 2024

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 31, 2024 | Original: January 4, 2010

Columbus Day is a U.S. holiday that commemorates the landing of Christopher Columbus in the Americas in 1492, and Columbus Day 2024 occurs on Monday, October 14. It was unofficially celebrated in a number of cities and states as early as the 18th century, but did not become a federal holiday until 1937.

For many, the holiday is a way of both honoring Columbus’ achievements and celebrating Italian-American heritage. But throughout its history, Columbus Day and the man who inspired it have generated controversy, and many alternatives to the holiday have proposed since the 1970s including Indigenous Peoples' Day , now celebrated in many U.S. states and cities.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an Italian-born explorer who set sail in August 1492, bound for Asia with backing from the Spanish monarchs King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella aboard the ships the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.

Columbus intended to chart a western sea route to China, India and the fabled gold and spice islands of Asia. Instead, on October 12, 1492, he landed in the Bahamas, becoming the first European to explore the Americas since the Vikings established colonies in Greenland and Newfoundland during the 10th century.

Later that October, Columbus sighted Cuba and believed it was mainland China; in December the expedition found Hispaniola, which he thought might be Japan. There, he established Spain’s first colony in the Americas with 39 of his men.

In March 1493, Columbus returned to Spain in triumph, bearing gold, spices and “Indian” captives. The explorer crossed the Atlantic several more times before his death in 1506.

Did you know? Contrary to popular belief, most educated Europeans in Columbus' day understood that the world was round, but they did not yet know that the Pacific Ocean existed. As a result, Columbus and his contemporaries assumed that only the Atlantic lay between Europe and the riches of the East Indies.

Columbus Day in the United States

The first Columbus Day celebration took place in 1792, when New York’s Columbian Order—better known as Tammany Hall —held an event to commemorate the historic landing’s 300th anniversary. Taking pride in Columbus’ birthplace and faith, Italian and Catholic communities in various parts of the country began organizing annual religious ceremonies and parades in his honor.

In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison issued a proclamation encouraging Americans to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage with patriotic festivities, writing, “On that day let the people, so far as possible, cease from toil and devote themselves to such exercises as may best express honor to the discoverer and their appreciation of the great achievements of the four completed centuries of American life.”

HISTORY Vault: Columbus: The Lost Voyage

Ten years after his famous 1492 voyage, Christopher Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed Columbus Day a national holiday, largely as a result of intense lobbying by the Knights of Columbus, an influential Catholic fraternal organization.

Columbus Day is observed on the second Monday of October. While Columbus Day is a federal government holiday meaning all federal offices are closed, not all states grant it as a day off from work.

Columbus Day Alternatives

Controversy over Columbus Day dates back to the 19th century, when anti-immigrant groups in the United States rejected the holiday because of its association with Catholicism.

In recent decades, Native Americans and other groups have protested the celebration of an event that resulted in the colonization of the Americas, the beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade and the deaths of millions from murder and disease.

European settlers brought a host of infectious diseases, including smallpox and influenza that decimated Indigenous populations. Warfare between Native Americans and European colonists claimed many lives as well.

Indigenous Peoples' Day

The image of Christopher Columbus as an intrepid hero has also been called into question. Upon arriving in the Bahamas, the explorer and his men forced the native peoples they found there into slavery . Later, while serving as the governor of Hispaniola, he allegedly imposed barbaric forms of punishment, including torture.

In many Latin American nations, the anniversary of Columbus’ landing has traditionally been observed as the Dìa de la Raza (“Day of the Race”), a celebration of Hispanic culture’s diverse roots. In 2002, Venezuela renamed the holiday Dìa de la Resistencia Indìgena (“Day of Indigenous Resistance”) to recognize native peoples and their experience.

Since 1991, nearly 200 U.S. cities, several universities and a growing number of states have adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day , a holiday that celebrates the history and contributions of Native Americans, alongside Columbus Day. While the Biden administration has officially recognized Indigenous Peoples' Day since 2021 , it is not yet a federal holiday.

What Is Indigenous Peoples’ Day?

Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebrates the history and contributions of Native Americans and, while not yet a federal holiday, it has been federally recognized since 2021.

Why Columbus Day Courts Controversy

Christopher Columbus undoubtedly changed the world. But was it for the better?

Christopher Columbus: How The Explorer’s Legend Grew—and Then Drew Fire

Columbus's famed voyage to the New World was celebrated by Italian‑Americans, in particular, as a pathway to their own acceptance in America.

When Is Columbus Day?

Columbus Day was originally observed every October 12, but was changed to the second Monday in October beginning in 1971.

In some parts of the United States, Columbus Day has evolved into a celebration of Italian-American heritage. Local groups host parades and street fairs featuring colorful costumes, music and Italian food. In places that use the day to honor indigenous peoples, activities include pow-wows, traditional dance events and lessons about Native American culture .

The Voyages of Christopher Columbus: Timeline

- 1451 Columbus is born

- 1492–1493 Columbus sails to the Americas

- 1493–1496 Columbus returns to Hispaniola

- 1498–1500 Columbus seeks a strait to India

- 1502–1504 Columbus's last voyage

- 1506 Columbus dies

Christopher Columbus is born in the Republic of Genoa. He begins sailing in his teens and survives a shipwreck off the coast of Portugal in 1476. In 1484, he seeks aid from Portugal’s King John II for a voyage to cross the Atlantic Ocean and reach Asia from the east, but the king declines to fund it.

After securing funding from Spain’s King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella, Columbus makes his first voyage to the Americas with three ships—the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . In October 1492, his expedition makes landfall in the modern-day country of The Bahamas. Columbus establishes a settlement on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

In November 1943, Columbus returns to the settlement on Hispaniola to find the Europeans he left there dead. During this second voyage, which lasts over two years, Columbus’ expedition establishes an “encomienda” system. Under this system, Spanish subjects seize land and force Native people to work on it. More

In the summer of 1498, Columbus—still believing he’s reached Asia from the east—sets out on this third voyage with the goal of finding a strait from present-day Cuba to India. He makes his first landfall in South America and plants a Spanish flag in present-day Venezuela. After failing to find the strait, he returns to Hispaniola, where Spanish authorities arrest him for the brutal way he runs the colony there. In 1500, Columbus returns to Spain in chains. More

The Spanish government strips Columbus of his titles but still frees him and finances one last voyage , although it forbids him return to Hispaniola. Still in search of a strait to India, Columbus makes it as far as modern-day Panama, which straddles the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In his return journey, his ships become beached in present-day Jamaica and he and his crew live as castaways for a year before rescue. More

On May 20, 1506, Columbus dies in Valladolid, Spain at age 54, still asserting that he reached the eastern part of Asia by sailing across the Atlantic. Despite the fact that the Spanish government pays him a tenth of the gold he looted in the Americas, Columbus spends the last part of his life petitioning the crown for more recognition.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Your kid can’t name three branches of government? He’s not alone.

‘We have the most motivated people, the best athletes. How far can we take this?’

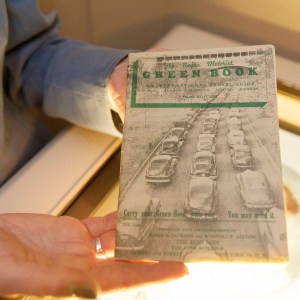

Harvard Library acquires copy of ‘Green Book’

A day of reckoning.

In June, a damaged Christopher Columbus statue in Boston’s North End neighborhood was removed. On Oct. 6, Boston Mayor Martin Walsh announced that the statue would not return to its original location in the area’s waterfront park.

AP file photo/Steven Senne

Harvard Staff Writer

Pushing to end myth of Columbus and honor history of Indigenous peoples

Celebrated by Italian immigrants in the United States since 1792, Columbus Day became a federal holiday in 1937 to commemorate the “arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas.” The explorer’s reputation has darkened in recent years as scholars have focused more attention on the killings and other atrocities he committed against Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. This year, amid a national reckoning on racial injustice, protesters have toppled and beheaded statues of Columbus in various cities, while pressure grows to abolish the national holiday and replace it with one that celebrates the people who populated the Americas long before the explorer “sailed the ocean blue.” The Gazette asked some members of the Harvard community, “Is this the end of Columbus Day, and how can America best replace it?”

Citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin Program Director, Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development

In the fourth grade, I came home from school and my dad asked me what I learned. I excitedly told him Mrs. Brennan taught us, “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” As an Oneida citizen and a national leader in American Indian education, I can’t imagine what must have run through his mind, but the next day he drove to my (predominantly white and affluent) school and called an emergency meeting with my teacher. That day, she revised her lesson plan.

For Native people in the U.S., Columbus Day represents a celebration of genocide and dispossession. The irony is that Columbus didn’t discover anything. Not only was he lost, thinking he had landed in India, but there is significant evidence of trans-oceanic contact prior to 1492. The day celebrates a fictionalized and sanitized version of colonialism, whitewashing generations of brutality that many Europeans brought to these shores.

In cities across the country there is a growing awareness of our collective and violent history — and of the legacies that reverberate in our justice, health, and educational systems. Statues of Christopher Columbus are crashing down and calls to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day ring out. For me, it is not as simple as replacing one vacation day on the calendar with another. If these calls are sincere, any change to Indigenous Peoples’ Day must be backed up by action and an active recognition of the continued survival and resilience of Indigenous peoples.

Investment in civics education needs to be made in partnership with tribal nations to teach the true history of the U.S. and to ensure every American knows that today, tribal nations are solving universal challenges and pioneering innovations that can change and enhance the world.

America could learn a lot from its first peoples. But it must start with the truth.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Joseph P. Gone, Ph.D. ’92

Professor of Anthropology and of Global Health and Social Medicine Faculty Director, Harvard University Native American Program

Recent responses to police shootings and killings of unarmed Black people in the U.S. have forced a national reckoning over America’s monstrous racial legacy. One consequence has been a radical rethinking of who we choose to publicly commemorate through statues, monuments, and celebrations. In this light, public observance of Columbus Day must end. For this nation’s over 5 million American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian citizens, Columbus’ voyages to the so-called New World inaugurated a long history of exploitation, enslavement, eradication, and erasure (and he himself initiated and sanctioned such actions).

Thus, to commemorate Columbus is to commemorate European colonization of Indigenous peoples. Instead of recalling and recounting those tawdry tales, let us instead cite and celebrate a most improbable outcome of this history: Indigenous survivance. Stories of Indigenous survival, resilience, and resistance remain in short supply in mainstream America, but not because they do not exist; rather, they have been eclipsed through a nationalist project of Indigenous erasure. We can change this by replacing the October federal holiday with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. The city of Cambridge has already done so, and while Harvard has adopted no formal policy that officially recognizes Columbus Day, neither has it uniformly struck Columbus Day from its academic calendars or formally recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day on a University-wide basis. The time of reckoning is at hand. Let us demonstrate together our collective solidarity with Indigenous peoples by abandoning public commemoration of Columbus in exchange for celebrating Indigenous survivance.

Jaidyn Probst ’23

Lower Sioux Indian Community

For Indigenous people in America, the fact that many institutions and governments still recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day under a different name (Columbus Day) is painful. It is only contributing to the continued erasure of Native peoples. There should be no reason to celebrate a man who only brought disease, genocide, and various assault to Native communities. He shouldn’t be a figure who is upheld in modern society. Quite frankly, he discovered nothing, so what is there to celebrate? America can best replace this day by acknowledging it universally as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Not only does this holiday allow the country to educate itself on the loaded history surrounding the holiday, it also celebrates the perseverance and power that Native communities continue to have in the world. Far too often, Native people are talked about as a thing of the past, and by designating the day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, it gives Indigenous people a break from having to constantly defend our existence to society. Not only is it a celebration of our people, it is also a celebration of our culture, our food, and our art.

Photo by Marilyn Heiman

Robert Anderson

Bois Forte Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Oneida Indian Nation Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School

It’s time for Columbus Day to go away and be replaced by Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a national holiday. That shift would require people to think about the fact that this country was founded on taking over territory that belonged to the Indigenous peoples who are still here and whose ancestors lived here for thousands of years and had their own societies, their own culture, and their own political institutions.

It’s important to acknowledge the Indigenous roots of this country we call the United States. We also have to respect the fact that modern-day Indian tribes in the United States are governments; they have sovereignty; they have land; and we still have the right to independence within the U.S. This is a territory where my ancestors lived, and I appreciate the fact that people in some areas understand they’re living on land that belonged to somebody else and still belongs to them in many ways.

Calling it Indigenous Peoples’ Day would draw attention to a fact that is so overlooked. I have taught Indian law for 12 years at the Harvard Law School, and many students come up to me to say, “We were never taught this in grade school or high school,” or even in college in many instances. They’re amazed to understand how the colonial process worked. I tell my students that this is a very uncomfortable part of U.S. history, a very rotten understory that people don’t like to look at. The Black Lives Matter movement is a great analog because some people want to ignore the fact that police act in ways that are racially discriminatory. In the same way, the majority in the United States prefer not to think about the fact that most of this country was forcibly taken away from the Indigenous populations. It’s something that people like to keep it in the closet or sweep under the rug. The time for a reckoning with the unjust treatment of Native American people is overdue.

Photo by Jillian Cheney

Anna Kate Cannon ’21

Co-president of Natives at Harvard College

There is some hope this year for a recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day to replace Columbus Day, primarily because there has been this huge reckoning with race propelled by the Black Lives Matter movement. A lot of changes that are happening now we owe to Black Lives Matter protesters. It has really forced a lot of people in power and a lot of regular American citizens to reckon with the fact that our country has very racist origins and structures in place today.

But I am much more hopeful for change at the state level than I am at the national level. As a co-president of Natives at Harvard College, I’d like to see the University recognize solely Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead of celebrating both Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Columbus Day. Every year, we get together in front of Matthews Hall, and we put on this big celebration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day. But we’ve always said that our gathering is part celebration of Indigenous people and part protest against commemorating Columbus Day.

Given the current situation and what we know about Columbus, we shouldn’t celebrate him. Many people know that Columbus never actually set foot in the U.S. Even celebrating Columbus as the one who discovered America is completely false. It is time to recognize the full and true history of the United States, which was founded on the stealing of Native lands and the deaths and disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples, who populated North America and the rest of the continent. We’re taught very early, in elementary school, that America’s claim to this continent’s land was entirely legitimate, and that the people who were here were not “civilized” and their societies were not “advanced enough.” This is part of the myth of America, the idea that the settlers deserved this land. But the truth is that Indigenous people were here before the settlers. Having a day to commemorate them would be a big step in recognizing the contributions of Indigenous people to this country’s history.

Photo by Alex Zak

Joseph R. Zordan ’26

Bad River Ojibwe Ph.D. Student in History of Art and Architecture

Even if Columbus Day were to reach its end in name, the things it represents— the doctrine of discovery, manifest destiny, etc. — are foundational to the myth that is America. The specter of Columbus will not be exorcised so easily from the land. But that doesn’t make the move to rename this day Indigenous Peoples’ Day meaningless. With each year I’ve been moved by the grace and dignity that we, as Indigenous people, have given ourselves on that day.

After centuries of the United States and Canadian governments attempting to make our culture, lives, and sovereignty illegible or nonexistent, we are still able to find one another wherever we go. I have been heartened too by the non-Indigenous people who have joined us in celebration, reflection, and reckoning with the difficult histories of colonialism and genocide. If we are to heal, to find a way to live here together, these processes are indispensable. While renaming Columbus Day to honor Indigenous peoples will not do this alone, I believe it has created a new space to allow for such connections and work to begin.

Share this article

More like this.

For Native Americans, COVID-19 is ‘the worst of both worlds at the same time’

Must we allow symbols of racism on public land?

Choctaw Nation’s Burrage thrives at Harvard

Another long-overdue reckoning for America

You might like.

Efforts launched to turn around plummeting student scores in U.S. history, civics, amid declining citizen engagement across nation

Six members of Team USA train at Newell Boat House for 2024 Paralympics in Paris

Rare original copy of Jim Crow-era travel guide ‘key document in Black history’

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Examining new weight-loss drugs, pediatric bariatric patients

Researcher says study found variation in practices, discusses safety concerns overall for younger users

Shingles may increase risk of cognitive decline

Availability of vaccine offers opportunity to reduce burden of shingles and possible dementia

Columbus Day is not a holiday the U.S. — and Italian Americans — should celebrate

As an Italian American tyke, I was proud to celebrate Columbus Day. It didn’t merit the attention that St. Patrick’s Day got in my Catholic school, with the Irish dancing, shamrocks and green cupcakes. But it still mattered. One of my ancestors discovered America. How cool was that?

It’s difficult to give up the myths that shaped the Italian story in the Americas. But these myths are holding us back.

Turns out the Irish had the better role model. No matter how you look at it, Columbus is not somebody we Italians should honor. And we should quit our efforts to salvage a holiday that brings us no glory while reinforcing the pain of the descendants of the people he exploited.

The historical record that has emerged over time is quite clear . Although Columbus was a skilled navigator, he mistakenly thought he could find a fast route to India and China by sailing West , and convinced the Spanish monarchs to bankroll his expedition.

Instead, he landed in the Bahamas and encountered the Taino people . When he met them, he wrote in his journal that these peaceful Indigenous people had the makings of “ good servants ” and put them to work mining gold — and facing amputation or death if they came up short. (Columbus was personally entitled to 10 percent of the booty; the rest went to Spain.) Later, he would ship thousands of Taino back to Spain to be sold into slavery, while the diseases the explorers brought decimated the tribe.

Opinion It's the beginning of fall. Here's why this season is secretly awful.

Even by the norms of the day, Columbus was excessive. As governor of the West Indies, he imposed such brutal punishments on anyone who got in his way — including the Spanish colonists who tried to defy or belittle him — he was sacked by his royal backers and returned to Spain.

Clinging to the need to honor Columbus goes beyond venerating one person. It also means keeping faith with a Eurocentric view of the world that exalts white male explorers who “discovered” continents that were inhabited by “uncivilized” barbarians.

Indeed, extolling Columbus helped the U.S. create an image of itself as exceptional. As his myth grew, he became the model for American daring and persistence against all odds, someone whose explorations had been blessed by Divine Providence. His voyage to America opened the door to the founding of the United States, thus was blessed by God, too.

How intertwined Columbus is with this American vision is evident in the number of monuments to him; according to researchers at the Monument Lab, he ranks third behind Lincoln and Washington . (The controversy over what to do with all those statues likely will play out for years.)

Italians weren’t even the focus of America’s original glorification of the explorer. It was only when Italian Americans were being lynched and the Italian government got upset that the Italian immigrants’ quest to honor Columbus and associate their heritage with him dovetailed with efforts to defuse a diplomatic controversy.

Opinion We want to hear what you THINK. Please submit a letter to the editor.

In 1891, 11 Sicilian immigrants were lynched in New Orleans after a mob blamed them for killing the city’s police chief, even though a jury hadn’t convicted them. Sicilians were targeted for lynching in part because they worked the same jobs as African Americans and often lived in their communities, leading Southerners to consider them more Black than white.

The New Orleans lynching was roundly praised. Rising political star Teddy Roosevelt called it “a rather good thing.” A New York Times headline was jubilant : “Chief Hennessy avenged. Eleven of his Italian assassins lynched by a mob.”

The Italian government was not so sanguine. It broke off diplomatic relations with the U.S. and demanded (and received) reparations. To further make up for the incident, President Benjamin Harrison in 1892 proclaimed a one-time holiday to observe the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of the New World. Harrison didn’t single out Italians, however, but rather extolled Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.”

Nevertheless, that proclamation ultimately set the stage for a federal Columbus Day holiday , created in 1934. The holiday “was central to the process through which Italian-Americans were fully ratified as white during the 20th century,” observed New York Times editorial writer Brent Staples .

So why should we keep referring to Columbus as an Italian hero? History already is moving us to a better place. Indigenous Peoples’ Day now replaces Columbus Day in 14 states, the District of Columbia and more than 130 communities.

I’m not the only Italian American on board with ditching the holiday. Last month, Italians for Indigenous Peoples’ Day testified before Massachusetts state legislators and urged them to replace the Columbus Day holiday.

Tellingly, the holiday’s defenders don’t even appear to acknowledge Columbus’ record of atrocities. Ignoring all the historical documents that show otherwise, Basil Russo , head of the Conference of Presidents of Major Italian American Organizations, continues to portray Columbus as a “good Christian” who treated Indigenous peoples “with respect and compassion.”

It’s difficult to give up the myths that shaped the Italian story in the Americas. But these myths are holding us back. They’re preventing us from creating a more honest Italian narrative, one that shines a light on the lives of our immigrant parents and grandparents and their heroism, and gives us better ways to celebrate our heritage.

Opinion I already miss the freedom Zoom gave me

If I were to nominate a new role model for Italians, it would be Mother Frances Cabrini, an Italian immigrant who in 1946 became the first U.S. citizen to be named a saint. Cabrini, like many immigrants, faced many obstacles and a lack of resources when she arrived, but persevered to help immigrants across the country. It was her work in the American West that prompted Colorado to designate the first Monday in October as Cabrini Day , replacing the state observance of the Columbus Day holiday.

For decades, the leaders of the American Indian Movement of Colorado had tried , unsuccessfully, to secure a state Indigenous Peoples Day. But they were gracious about the Cabrini holiday. They praised the saint as “the opposite of Columbus.”

Why can’t we Italians see how much richer our history is than the story of one directionally challenged explorer who spent most of his life outside Italy? Columbus never found the route to China and India he was seeking. We shouldn’t make our own wrong turn by continuing to honor his memory.

- 'The Many Saints of Newark' is a 'Sopranos' prequel Italian Americans don't need

- We should celebrate Mother's Day the way the Italians do

- Fall is upon us. Here's why this season is secretly awful.

Celia Viggo Wexler is the author of “Catholic Women Confront Their Church: Stories of Hurt and Hope.”

1492: Columbus in American Memory

Columbus Day is here again — bringing both celebrations and denunciations of the man whose name the holiday bears. And it’s not just the holiday: Christopher Columbus’s name has been worked into numerous cities across the United States, the names of ships and universities — even a space shuttle. And from an early age, schoolchildren learn about the voyages of the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa María, and the man who “discovered” the American continent. But many Americans have also questioned Columbus’s legacy. Should we venerate a man who symbolizes European colonization, and who inaugurated the decimation of native populations that would continue for centuries?

So on this episode of BackStory , Peter, Ed, and Brian explore the controversial Columbian legacy, diving into current debates, and looking back on how earlier generations have understood America’s purported discoverer. When and why did we begin to revere the Italian explorer? Who has seized on his legacy, and who has contested it?

ED: This is BackStory. I’m Ed Ayers.

It was 521 years ago this week that Christopher Columbus came ashore in the Bahamas. And ever since, people have been struggling to define just what that event meant. For the first 300 years, he was only one in a sea of European explorers. But in the early decades of US history, a bestselling biography helped elevate Columbus above the rest.

ROLENA ADORNO: So what emerges is this sole heroic figure who has to work against the interests of others.

ED: These days, Columbus has been taken down more than a few notches. In some high school history classrooms this fall, in fact, he’s even being put on trial for mass murder.

STUDENT AS QUEEN ISABELLA: We gave him money for spices and gold. We didn’t give it for him to shed blood and kill all those people.

ED: Today on BackStory, Christopher Columbus’s long and twisted journey through history.

PETER: Major funding for BackStory is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and an anonymous donor.

ED: From the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, this is BackStory with the American Backstory hosts.

BRIAN: Welcome to the show. I’m Brian Balogh, and I’m here with Ed Ayers.

ED: Hi, Brian.

BRIAN: And Peter Onuf’s with us.

PETER: Hey, Brian.

DAN RATHER: 500 years ago today, Christopher Columbus landed on a Caribbean island thinking he was off the coast of Asia. He found–

BRIAN: This is a CBS News report from October 12, 1992. Columbus Day.

DAN RATHER: Was he a genius, a tyrant, or both? As John Blackstone reports, the argument is gaining momentum today.

BRIAN: Ground zero for that argument was San Francisco. Columbus Day was a big deal for the city’s Italian American community. They’d been celebrating it since 1869. There was a parade with floats and marching bands and local politicians mugging for the crowd. Italian American girls competed to be crowned Queen Isabella.

PETER: And of course, there was also Christopher Columbus. Each year a reenactor represented the great navigator himself, complete with sword and gold cross. And for the 500th anniversary, the coordinating committee had something special planned. Columbus would arrive not by plane, train, or automobile, but by boat, just like in olden times.

JOHN BLACKSTONE: Joseph Cervetto was all dressed up and ready to wade ashore triumphantly as part of the festivities in San Francisco yesterday.

BRIAN: But when Cervetto’s boat got close to shore on the big day, his crew noticed a problem. There was a crowd of around 4,000 protesters lining the waterfront. They were part of a coalition led in part by the American Indian movement, and they held signs with slogans like, “End 500 years of racism!” and “No to slavery and genocide.” They were there to stop Columbus from landing.

PETER: One of those protesters was a man named Sam Diener. He was on shore handing out pamphlets and he remembers other protesters bobbing out into the bay in boats. He called it a peace navy.

SAM DIENER: This motley collection of canoes and kayaks and sailboats with signs and banners, and folks crisscrossing the bay ready to greet any ship that came in with the Columbus actor.

JOHN BLACKSTONE: The welcoming party was so unfriendly that Columbus just waved from way out beyond the breakwater and kept on sailing.

MALE SPEAKER: Maybe next year he might show up.

SAM DIENER: There was an announcement that came out that the folks who were organizing the Columbus landing had decided not to run the gauntlet of the peace navy and not to land at Aquatic Park after all. And a big cheer came from the crowd. And basically at that point, people hugged each other and congratulated each other, and we dispersed.

PETER: Unfortunately, the day didn’t end so peacefully. After Columbus turned around, most of the protesters, like Sam, went their separate ways. But a few hundred headed over to the official parade, which wound through a heavily Italian part of town. According to news reports, that’s when things got out of hand.

BRIAN: Some protesters threw raw eggs at parade floats. Others shouted, “Mass murdering pig!” at the Columbus reenactor, who had– yep– finally made it to land. A few even threw Molotov cocktails.

Some paraders fought back, leading to fights in the street. In the end, police arrested 40 demonstrators for disrupting the parade and inciting riot.

PETER: National newspapers and TV networks picked up the story. It was the first major Columbus Day protest to get this kind of widespread coverage. And for many Americans, it was their first real exposure to the idea of Columbus as a villain.

SAM DIENER: I remember also going home on the bus talking with this older Italian American woman who was just befuddled and confused and a little bit hurt by all these protests. And she was like, why are you protesting Columbus? Are you anti-Italian? What is this? And it disturbed her.

And that was interesting to me to encounter a previous generation’s view of Columbus. And what Columbus for her meant was about her Italian pride, not having ever been exposed to the idea that Columbus committed horrible crimes.

PETER: For the rest of the hour today on BackStory, we’re going to look at the ways this one man has meant so many things to so many different people. From his transformation into the figure of Columbia way back in the founding period to the celebration of his origins by immigrants a century later, we’ll look at the ways generations of Americans have discovered, and rediscovered, Columbus.

ED: But before we consider Columbus’s legacy, we thought we should spend a few minutes considering what the man himself actually did. To do that, I sat down with Tony Horwitz. A few years ago, he dug into the story of Columbus’s voyages for a book he was writing. And he found that a lot of the things we think we know about Columbus just aren’t true.

Like the one for example, about how everybody else in 1492 thought the world was flat? Well actually, the idea that the Earth was round had been taken seriously since Aristotle. For centuries.

TONY HORWITZ: Columbus’s great vision was not that the world was round, but that it was small.

ED: [LAUGHS]

TONY HORWITZ: Columbus, drawing largely on scriptural sources in various mystical texts, felt that it was a matter of weeks to sail from Spain to the Indies, as it was known then. He was really looking for China and Japan and the riches of Asia. And that was a smaller distance than it actually is. It’s about 12,000 miles.

TONY HORWITZ: And he thought it was only a few thousand. So really, he succeeded because he was so desperately wrong.

ED: Wow, that’s fascinating. So Columbus’s great contribution, ironically, does not grow out of being an early Enlightenment thinker, but rather of being a one of a kind mystical thinker.

TONY HORWITZ: Yeah. To me, Columbus really represents more the end of medieval thinking, rather than an early Enlightenment figure.

He was also at the right place at the right moment and found a willing ear in Queen Isabella in particular, who was very pious. Part of what he promised was that the riches he discovered would be used to fund a crusade really, to reclaim Jerusalem for Christians. So I think he appealed to her partly on religious grounds.

ED: Tony, can you recreate for us what that moment of first contact with the native peoples looked like?

TONY HORWITZ: Columbus’s first landfall in the Americas is at the eastern edge of the Bahamas. It’s a peaceful encounter. He talks about the beauty of the landscape. He describes the people, who he finds very attractive and needless to say, have a lot of strange customs, one of which is smoking this leaf that they call tobacco.

There’s also a wonderful moment when he’s fed a strange creature. It was probably an iguana. And in this journal– I am not making this up– he writes, “tastes like chicken.”

TONY HORWITZ: I have to believe that’s the earliest such reference to that. One really disturbing note is he almost instantly writes of how these people are so childlike and willing that they could easily be turned into servants of the crown. By which he really means slaves.

He’s searching for gold and spice, and the islanders say something, which he clearly doesn’t understand, that suggests to him that just over the horizon he will find what he’s looking for. They were probably trying to get rid of him. And he sails off quite quickly to Cuba. And really, everywhere he lands, this somewhat comic scene repeats itself, where Columbus communicates what they’re after and islanders say, not here, but if you keep sailing, you’ll find it at the next place.

ED: So that sounds like a glorious, if unfulfilled voyage. He goes back home and he’s welcomed with celebration, I’m assuming. And then what happens?

TONY HORWITZ: Columbus returns to Spain with parrots and jewelry and other interesting items from his voyage, including about 10 natives, and is commissioned to embark on a second voyage with an enormous fleet and 1,200 men. And he tours much of the rest of the Caribbean and gradually becomes something of a failure.

He was, by all accounts, a great mariner and navigator. But he was hopeless on land and very poor as an administrator. So when his initial discoveries lead to the creation of a settlement, his fortunes really begin to go downhill. He sails off whenever there’s troubled to find other places, leaving incompetents in command– often family members.

And after his third voyage to America, he’s actually arrested and brought back to Spain in chains on charges of mismanagement and incompetence and brutality. And though he’s freed after six weeks, he really is a disgraced or distrusted man within Spain. And he has one more voyage, which is even more disastrous, and ends his days as really a very sad, broken figure.

ED: Well, I don’t want to hear that!

TONY HORWITZ: [LAUGHS]

ED: That’s not American! I mean, it’s a Horatio Alger in reverse, right?

TONY HORWITZ: Yeah.

ED: That he starts out successful, but then he can’t actually deliver on it. And this was widely recognized at the time? I mean, was he famous and then forgotten?

TONY HORWITZ: He is certainly famous in his day. Some of his letters and reports of his voyages get around Europe very quickly.

But one of the great ironies of Columbus’s story is that while he makes all these great discoveries, he doesn’t understand himself what he’s done. He continues to believe, apparently to his dying day, that he had reached Asia. And others were a little more clear-eyed and began to see that what he and his men were describing was not Asia. It really was a new world.

And as a result, it was others who began to build on those discoveries and even take credit for them. So that he became more and more lost really, in his own mind.

At one point, he even decides that the world isn’t round. He thinks he’s sailing uphill, and that the world is actually shaped more like a pear with a nipple where he thinks the Garden of Eden lies. So he really loses his way, and in some ways, seems to lose his mind in the course of these four voyages.

ED: Tony Horwitz is the author of A Voyage Long and Strange, among many other books. We have posted a link to an excerpt from that book at backstoryradio.org.

BRIAN: It’s time for a quick break. When we get back, the man who made Columbus into an all-American hero.

PETER: You’re listening to BackStory, and we’ll be back in a minute.

BRIAN: This is BackStory. I’m Brian Balogh.

ED: I’m Ed Ayers.

PETER: And I’m Peter Onuf. We’re marking Columbus Day with a look back at the many makeovers Christopher Columbus has undergone throughout American history.

BRIAN: We have a question from one of our listeners that came in on our website. It’s from Shane Carter, who teaches history. And Shane says that each year his students become fascinated by the other Spanish sailors who made their way to North America after Christopher Columbus in the 1500s.

People like Cabeza de Vaca and Vasquez de Coronado. Both those guys explored vast stretches of the current day Southwest. And then of course, there was Hernando de Soto, who traveled over what’s now the Southeast, and was the first known European to cross the Mississippi.

Shane writes that– and now I’m going to quote– “In order for the US to claim any kind of connection to Columbus, we seem to need to ignore 100 plus years of history.” So what do you think, Peter, Ed? Why does Columbus loom so much larger in our national mythology than these Spanish guys? After all, they actually made it to our land mass.

ED: When you really do think about it, it is remarkable how little enduring memorialization there is of de Soto, who would’ve covered more of what’s now British North America then anybody, right? Until Lewis and Clark.

PETER: Yeah.

ED: And we have no memory of him at all! So I think that Shane’s question’s an excellent one. And I wonder if it has something to do with Columbus’s uncertain ethnic origins. The fact that he’s kind of Italian, kind of Spanish. He’s kind of pa-European.

PETER: Well, he’s Italian, but he’s for sale. [LAUGHS] And whoever would sponsor him will get the advantage of his enterprise. So that idea that he’s up for grabs makes him a kind of European, a generic European. And that’s the way he sells himself.

I mean, this is a step– we had steps on the moon for mankind. Well, this is a step into the New World for Christendom, for Europe. And so he’s the beginning of everything in this age of the penetration of the New World. And then other national traditions that become increasingly clearly national traditions build on that beginning.

ED: Well, and it’s not just a national tradition in general. And Shane’s question is, how about these guys from Spain?

PETER: They’re the ones who actually come to what becomes the United States. But they come of course, in the name of the king of Spain. And here we get into dueling imperial histories.

What is the United States’ claim to North America? It’s not based on Spanish discoveries. It’s based first on English discoveries, English settlements.

And if you acknowledge the discoverers and you say they yeah, they were there, they planted the flag, it’s theirs! No. The British insist that it’s open space. It’s terra nullius. So in a way, the mapping of the New World leads to our interpretation of its history.

I think what’s interesting is you’ll get more interest in these figures– Coronado, de Soto, de Vaca, and so forth– now as we begin to understand the multi-imperial origins of the United States. And now that there’s a large Hispanic population, then these figures become important and Columbus fades away.

ED: OK. So what we will expect now is the Hispanicization of discovery, right?

PETER: You are so right.

ED: You know, Brian, I think you’re probably on the cutting edge of historical reclamation. I think listeners to our shows know that you are proud native of Southern Florida. Was there any sense of this sort of Spanish era in your childhood?

BRIAN: You bet there was, Ed. I went to Ponce de Leon Junior High School in Coral Gables, Florida.

PETER: Oh, that’s why you’re so youthful!

BRIAN: Eternally! And even before that, in elementary school, the history curriculum emphasized de Soto far more than Christopher Columbus. We were very proud of those Spanish explorers and conquistadors. And I’m not going to tell you about my toreador pants.

PETER: Well, you wouldn’t have been proud if you were a little bit older than you are now and were born in the 19th century. It’s only in the 20th century that new regional traditions emerged in the United States to reinforce the notion of the United States as a great power. The California missions, the southwest border lands, all became Spanish in the national imagination in the 20th century, long after they really were Spanish in any sense of the word.

ED: Yeah, after we’d actually established that we owned all that.

ED: Sure, put an adobe house here or there, right?

PETER: That’s exactly true! It’s a tourist scam! Think of Santa Fe. It’s make believe. It’s Disneyland before its time.

ED: So it sounds like to me that Shane makes a really good point, that we do ignore this 100 years ’cause we’re not exactly sure what to do with it. Precisely because it does have historical content, it’s like, oh man, that opens up a lot of issues. Let’s just go from Columbus to the Puritans and forget all that stuff that happened in between.

PETER: [LAUGHS]

ED: Well, if you’re just joining us, this is BackStory and we’re talking about the ways Americans have told and retold the story of Christopher Columbus in the years since 1492.

BRIAN: If it was Columbus’s ambiguous origins that made him available for the taking, it was more than 300 years before somebody in America actually seized on that opportunity. That somebody was Washington Irving, better known today as the author of “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” But in the 1820s, Irving’s Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, the first English language biography of the explorer, was a best seller. And it formed the basis for the Columbus that a lot of people would recognize today.

PETER: I sat down with Rolena Adorno, a professor of Spanish at Yale University. She told me that it was a visit to Spain that led Irving to chronicle Columbus’s story.

ROLENA ADORNO: When he was there, it was suggested to him that he produce a translation of the great body of documents associated with Christopher Columbus that were just being published at the time. In Spanish, of course. And he took a look at this massive corpus and realized that a translation would be more than a lifelong task for him. So he turned instead to, in fact, write a narrative of the life of Columbus.

PETER: Rolena, what about this portrait that Irving gives us of Columbus would you say was new?

ROLENA ADORNO: What Irving made perfectly clear was to create Columbus as a self-made man. And that’s an expression we get from a speech on the floor of the US Senate sometime during this same period. That is to say the individual who against all odds, with a visionary hope of his own, and full confidence that he can realize that vision, forges ahead, leaving anything and everybody who doesn’t want to go with him behind. It’s the frontier spirit.

PETER: Right. Irving’s Columbus then gives us a window into American cultural history of the period, or how Americans were beginning to think about themselves as they constructed their back story.

ROLENA ADORNO: Exactly. Exactly. It’s a Columbus who is somebody in a foreign land. It is someone who is going to create his own destiny, and that of an entire new world. And of course, in the United States this was so resonant in that period.

Remember, we’re in the period between the War of 1812. We are not yet into the era that will become the onset of the US Civil War. So it is a great time of expanding westward. And Columbus is a, shall I say, prototype of that adventure. So I think that’s always the resonance for this Columbus, this pioneering, entrepreneurial Columbus.

PETER: Rolena, we are terrible skeptics and cynics these days. It’s hard for us to read Washington Irving and believe that he believed what he was saying. Was he not aware of what seems like such blatant, romantic, over the top distortion?

ROLENA ADORNO: I think he was aware of that distortion. And the way I think that he was aware of it is by whitewashing Columbus himself. And putting the guilt for greed, exploitation of all sorts on the back of King Ferdinand and those seditious expeditionaries that were with him and those who followed.

These are Washington Irving’s words. He says that Columbus was, “continually outraged in his dignity, and braved in the exercise of his command, foiled in his plans by the seditions of turbulent and ruthless men.”

PETER: Whoa.

ROLENA ADORNO: And I must add, why is he doing this? He’s doing this of course, because even in Irving’s day, the fatal flaw was what led to the enslavement of a continent of peoples. So the way Irving casts this is that no, it was Columbus who had the heroic vision. And it was the others, not Columbus, who are responsible for all of the indignities that he suffered, not to mention the exploitation that the native peoples of the Americas suffered.

PETER: I’m wondering if the heroic Columbus doesn’t have an afterlife? We’ve beaten him down in the academy, but that sense of boy’s own adventure, enterprise, all that stuff. And it survived in school textbooks, didn’t it, well into the 20th century?

ROLENA ADORNO: It certainly did. Yes, as a kind of model of conduct. And so that image lived on and on.

And you may well imagine that when it was excerpted or when popular versions or textbook versions were made, they highlighted exactly the characteristics that we’ve been talking about. The sole individual, visionary in outlook, practical in approach, ready to conquer new worlds, ready to extend new frontiers, ready to do well for himself while claiming to do good for others.

PETER: Rolena Adorno is the Sterling Professor of Spanish and chair of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Yale University.

ED: And so it was Washington Irving who gave Christopher Columbus his heroic stature in America. But it was another group of Americans who really get credit for getting the statues of Christopher Columbus built. That would be the associations of Italian and Irish immigrants, who first started celebrating Columbus in local parades in the 1860s. And those same groups, over the next several decades, successfully made the case for state and even national holidays in honor of the explorer.

PETER: The Irish latched on to Columbus because, like them, he was a Catholic. The Italians focused more on his roots in their homeland. But both groups recognized in Columbus an opportunity to lay claim to America’s very first founding father. And in so doing, to overcome their status as second class citizens and prove that they too belonged in America.

BRIAN: But there were other immigrants in the late 19th century who weren’t so keen on the Italian navigator. One of them was a Norwegian American scholar named Rasmus Bjorn Anderson. In 1874, Anderson published a book called America Not Discovered By Columbus.

JOANNE MANCINI: It’s one of those books where you can tell the thesis from the title.

BRIAN: This is Joanne Mancini, a historian in Ireland who’s written about how Anderson set out to tell a new story about the beginning of America, a story that would appeal to East Coast elites threatened by the wave of Catholic immigration. Instead of beginning in 1492, Anderson’s story started with the Vikings in the late 900s. Not only had they made it to the New World, he argued, they had sailed into Massachusetts Bay itself. Hence the town of Woods Hole, allegedly named with the Viking word for hill. Hence the supposed Viking skeleton unearthed in Massachusetts a few decades earlier.

Anderson sent copies of his book to luminaries like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and President Rutherford B. Hayes. And Joanne Mancini says it caught on.

JOANNE MANCINI: And after this point, there was a bit of another Viking craze where various people in New England really embraced the idea of Viking discovery. And so for example, there was a successful movement to have a statue of Leif Ericson in Boston, which was put up in 1887. And I think actually that there was a period where people found that every time they uncovered a rock and it had scratchings on it, that this had to be runic inscriptions.

BRIAN: [LAUGHS] And what was the appeal to those New Englanders? What about Anderson’s book might have been more attractive than the Columbus story as a founding story?

JOANNE MANCINI: Well, I mean there are a couple different things. And it depends on what perspective you take on it. But on the one hand, I think he was trying to appeal to certain understandings that the native born elite would have had about themselves.

So for example, he emphasized that these Norse settlers had institutions which were in a way, the predecessor institutions of American institutions. And so he emphasized that they were free men who assembled in what he called “open parliaments of the people”, referring to something which actually existed, which were these Scandinavian assemblies. And so he was appealing to their understanding of themselves politically.

But he was also appealing to the racial sensibilities of the day. He was suggesting that Americans of British descent were actually descended from the Northmen through the Norman conquest and through the Norse incursions into Britain. And he was also, I suppose, trying to establish to Americans that modern day Scandinavians were connected to this and that there was a link between the two peoples.

BRIAN: Right, so freedom loving people who passed that through their blood and through their cultural heritage.

JOANNE MANCINI: Very much. And through their religion as well. He was very careful to provide a contrast actually, between the Vikings and Columbus, whom he described as “subservient to inquisition.”

And he told a whole story about how this party of Vikings was led by Leif Ericson, the son of Erik the Red, and that one of the people who accompanied him was Leif’s brother, Thorvald Ericson. And so in Anderson’s book, he presents the story that Thorvald was killed by Indians in North America, crosses are erected on his grave, and that he sheds Christian blood. It’s a way for him to almost invert the history that people would have known, and indeed that people were still experiencing at the time about conquest, where most of the violence would have been perpetrated by Europeans against Indians.

And so in a way, he has this alternative history of the discovery of America where the violence is going primarily in the other direction against Europeans. And it’s an interesting story to be telling the people. Because if you think about this period, a lot of people in New England were quite uncomfortable with many of the trends in the West.

BRIAN: Right.

JOANNE MANCINI: And so Anderson was giving them this other story which says well, these people of free institutions and of the true race and Christianity come to America, they engage in battle with the Indians, the Indians win. And it’s a very different sort of take on things than the normal history that they would have had to confront. And it’s also a different story to the story of Columbus, where of course, there would’ve been a very strong tradition to emphasize what we would think of as the genocidal implications of the Colombian conquest.

BRIAN: If 19th century New Englanders were taken by this story as many were, how come it didn’t take off in the 20th century?

JOANNE MANCINI: Yeah, I think there are a couple of different dimensions of that. One is that in the 1920s, there is a successful push to have very strict restrictions on immigration. And so a lot of the dynamics which were pushing these kinds of distinctions between say, southern Europeans and northern Europeans, start to fade away because there are legal restrictions which are preventing many of these new populations from entering the country in large numbers. And so people become less preoccupied with that. And so the late 19th century search for alternative origins and the building up of an identity based on a very specific racial history becomes, I suppose, less of a feature of American racial politics as people become more focused on other issues regarding race.

BRIAN: Joanne Mancini is a historian at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth. We’ll post a link to her article about America’s 19th century Viking enthusiasm at backstoryradio.org.

PETER: It’s time for another break. Coming up next, Columbus is asked to answer for his crimes to a room full of teenagers.

ED: You’re listening to BackStory. We’ll be back in a minute.

PETER: And I’m Peter Onuf. We’re talking today about Christopher Columbus and how his name has resonated throughout American history.

ED: We’re going to turn the clock back now to one of the first examples of Columbus’s name being invoked. In the 16th and 17th centuries, as people on both sides of the Atlantic debated what to call this new world, a variation on the explorer’s name often cropped up. Columbia. And though a different explorer– Amerigo Vespucci– ultimately got naming rights, the name Columbia did live on in a different guise.

PETER: During the Revolutionary War, a symbolic figure with that name emerged, eventually becoming as recognizable as Mickey Mouse is today. Part of the idea was to create a counter to England’s muse, Britannia.

ELLEN BERG: The first person who really made a very clearly human Columbia was Phillis Wheatley, who was a well known poet at the time of the Revolution.

PETER: This is historian Ellen Berg.

ELLEN BERG: And what was really striking about her is that she was a former slave. She’d come to America as a child and was enslaved. She was named after the slave ship she was brought on in 1761, The Phillis. And she lived with the Wheatleys in Boston originally, and was taught English by them, was taught to read and write, and became quite a well known poet in her time.

Where she really invents Columbia is in 1775. She writes a poem to George Washington, who was then the commander in chief of the Continental Army. And at that time, the two armies were at an impasse. And in a way, Phillis Wheatley is calling upon George Washington to action, and calling him to greatness. And she uses this goddess figure of Colombia for the first time that we really know of as a way of imploring him to lead the people on and create a great country.

PHILLIS WHEATLEY: To his excellency George Washington. Celestial choir enthroned in realms of light. Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write. While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms, she flashes dreadful in refulgent arms. See mother Earth–

ELLEN BERG: She sent the poem to him. And in fact a few months later– it took him a little while– but he wrote back to her and asked her to come visit him at his station so that he could thank her for this beautiful poem that she wrote.

PETER: Right, right.

ELLEN BERG: He then helped to get her poem into print.

PHILLIS WHEATLEY: Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side. Thy every action let the goddess guide. A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine. With gold unfading, Washington! Be thine.

PETER: After Washington helped publish Wheatley’s poem, Columbia began to show up in songs and newspaper cartoons. She helped give meaning to a nation in its infancy.

ELLEN BERG: In the early decades of Columbia, she is considered the genius of the place. Which is an old concept.

ELLEN BERG: But basically, she is the guiding force. She is this wise creature, this wise being who can lead the country. And I think that’s really important early on, because there’s some sense of a supernatural force who is helping us know what to do, where this country should be going.

So in the first few decades of use of Columbia, she is a bit removed from politics. She’s kind of off in a cave somewhere or up in the clouds in some beautiful place. And poets and some artists then use her to express their feelings about how the country’s going.

PETER: And the country looked to her throughout most of the 19th century. She was depicted weeping on Washington’s coffin. Presidential candidates were seen wooing her in the popular press. But soon, there was a new kid on the block.

ELLEN BERG: Ultimately, Uncle Sam really does supersede Columbia, but it takes quite a while for him to do that. He’s first identified as a symbol during the War of 1812. And I’d say it wasn’t for another 100 years or so that Uncle Sam really took her place or became more well known as a symbol. She’s use quite heavily alongside Uncle Sam during the Spanish-American War.

PETER: Are they depicted together sometimes?

ELLEN BERG: They are often–

PETER: Uncle Sam and Columbia?

ELLEN BERG: Yeah.

PETER: What an odd conjunction. It’s hard for me to imagine this classical woman in her flowing robes and this guy from Troy, New York with a beard.

ELLEN BERG: Yeah well, she’d had classical robes, but also a number of artists depicted her in more contemporary clothing. Depends on the time and the place.

But Uncle Sam and Columbia have an interesting relationship. It’s not always clear how they’re related to each other. Is he her uncle? That’s often one way he’s expressed. Sometimes it seems more of a domestic partnership or–

PETER: Ooh. There’s an erotic dimension to this then, you’re suggesting.

ELLEN BERG: Yeah, sometimes they are an old married couple with their children, the many states. So it’s a flexible relationship–

ELLEN BERG: That people can use as they see fit.

PETER: By the 20th century, with the federal government looming large, Columbia was on her way out. It was Uncle Sam’s turn to shine.

ELLEN BERG: Over time, Uncle Sam becomes more powerful with the rise of the federal government as a stronger and stronger power.

PETER: You might say that Columbia is the figure that embodies, almost literally, the nation. Whereas Uncle Sam is the more aggressive, assertive representation of the state.

ELLEN BERG: Yes.

PETER: And the balance between those two things, of course, has shifted over time. For the most part, Columbia has vanished from our memory. But Berg says she was so present through so much of our history that you can never erase her completely.

ELLEN BERG: Some people would argue that Columbia is right there in New York Harbor. The Statue of Liberty originally would have been considered as the Statue of Columbia for many, many Americans. And they referred to the statue in that way.

And I think it’s just over time, as our knowledge of Columbia has fallen, what remains is the statute who we know is the goddess of liberty. And the statue has become the stronger figure. So in a way, we can say that Columbia is still there, we’re just not really aware of it.

PETER: Ellen Berg is working on a book tracing the history of the goddess Columbia.

BRIAN: For the final part of our Columbus Day show, we’re going to turn to the place where a lot of people first hear the name of the great explorer, the school classroom.

JULIAN HIPKINS: Columbus is going to start. So Columbus is up front. The jury’s in the back.

ED: Now what you’re hearing is a bunch of 11th graders getting ready to do a little more than just read about the story of Columbus. Desks are set up in a long rectangle. At one end, a jury. At the other, a sort of a witness stand. The students here are about to put Christopher Columbus on trial.

JULIAN HIPKINS: The first two minutes roughly will be your time to say why you are innocent and who is guilty. And then the jury will be able to ask questions.

ED: This is Julian Hipkins. He’s a history teacher at Capital City Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., which serves mostly black and Latino students. The trial he’s organized is based around Columbus’s voyages. It’s a sort of who done it. The class has to figure out who is most responsible for the decimation of the Caribbean Taino Indian population.

And it’s not just Columbus on trial . It’s also his men, the king and queen of Spain, and the entire system of colonialism itself. Even the Tainos are on trial for not fighting back.

JULIAN HIPKINS: So jury, as you’re going along, start thinking about percentage guilt. All right, Columbus, let’s go. Begin.

ED: Members of the jury question Columbus and several of the students who make up his council. And while speaking, they wave around incriminating documents like excerpts from Columbus’s journal.

MALE STUDENT: You ordered your man to chop off their hands if they didn’t come up with the amount of gold in three months. You also ordered your men to spread terror among the Tainos. What do you have to say about that?

ED: A very defensive Christopher Columbus says he gave those orders in response to violence instigated by the Tainos.

STUDENT AS CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS: Sir, it was after they killed 39 of my men!

ED: Once the defendant steps down, his men are grilled.

FEMALE STUDENT: You were never given orders by Columbus to rape woman specifically, or to set dogs on children, so why did you do all of that as well?

ED: But they just pin it back on their boss.

STUDENT AS CREW MEMBER: We might have done those things. But in a way, we need a good loyal leader to lead us. And in a way, he just unleashed us into this land and we just misbehaved, which was on our part. But at the same time, we need guidance.

ED: The arguments ping pong back and forth. Students representing the system and then the Tainos take turns defending themselves . When Queen Isabella takes the stand, she says that it was all supposed to be a straight business operation.

STUDENT AS QUEEN ISABELLA: We gave him money for a voyage, for spices and gold. We didn’t give it for him to shed blood and kill all those people.

ED: The teacher, Julian Hipkins, says this way of teaching about Christopher Columbus forces students to think critically.

JULIAN HIPKINS: The thing I like with the trial is that it’s not so black and white where this person was responsible and this person wasn’t responsible. It’s much more complicated than that. You can have a lot of people responsible for one act in some way, shape, or form.

ED: And 16 year-old Destiny, who played Queen Isabella, says this story of Columbus is very different than the history she learned in elementary school.

DESTINY: It was like he had three ships. The Nina, the Pinta, the Santa Maria and stuff. And he went on a couple of voyages.

And I knew there was a little song. It was some type of song they sang. I mean, I didn’t really know much about him.

ED: Finally, the verdict is read. Though nearly every defendant has pointed the finger back at Columbus, he doesn’t get most of the blame. It’s actually pretty evenly spread around.

CHRISTIAN: Columbus himself, 25%. Columbus’s men, 20%. King and queen, 30%. Tainos, 10%. And the system, 15%.

ED: Christian, the student who read the verdict, stresses that history wasn’t the only thing that went into those numbers.

CHRISTIAN: We tried our best to decide our ruling based on what the groups gave to us. Not based on our background knowledge, but what was presented to us. And because of that, some of the groups’ arguments weren’t really strong. So it didn’t help them very much to prove that they weren’t guilty.

ED: So Brian and Peter, I think it’s important to realize that this exercise we just heard is an exercise that’s used in lots of classrooms. And it was inspired by Howard Zinn’s bestselling book from 1980, A People’s History of the United States. In that book, he says we need to focus on the injustices of the American past, rather than just its great men.

So what do you guys think? Should we be teaching history by doling out blame for the darkest moments in our past?

BRIAN: This is, I think, a creative, and in my opinion, effective way to get a bunch of high school students engaged with material that’s got to be pretty distant to them on the surface. How do you get high school students all excited? Well, ask them to make some judgments about people.

PETER: Brian, I think you’re right about the excitement of in effect, having history, you make the decisions about what history is. And that is empowering. That is engaging.

But it reminds me of something that we do as historians, and have always done, and that we need to reflect on a little bit. And that is this revisionist impulse, which is the beginning of good history. That’s the idea. What do we think we know, and let’s challenge it.

Now revisionism goes way back in American historiography and I think the word is used in the 1960s. But by 1980, when Howard Zinn wrote The People’s History of the United States, this is in effect a summa, a big statement of revisionism. And rather than framing the question who made America, the question is what bad things happened to the people who are the real Americans?

So it switches the terms from nation making to the costs of nation making. Because at the end of the day, it’s the people who are the nation. So that’s a flip of perspective that I think’s really important. And I think it raises fundamental questions about what we do and how we think about somebody like Christopher Columbus.

ED: I have written that I want revisionist history the same way I want revisionist surgery. [LAUGHTER] I want people to be using the latest technology, the latest ideas that they have.

PETER: Yeah, yeah, yeah.