| | | | | | | | | | | | | | Afghanistan | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.4 | -2.6 | -2.7 | -2.8 | -2.8 | -2.7 | -2.7 | -2.5 | -2.6 | | | Albania | -0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | | | Algeria | -1.4 | -1.2 | -1.2 | -1.1 | -1.1 | -0.9 | -0.8 | -1.1 | -0.8 | -1.0 | -0.7 | | | American Samoa | .. | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | | | Andorra | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | | | Angola | -2.0 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.7 | -0.6 | | | Anguilla | .. | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | | | Antigua and Barbuda | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | | | Argentina | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | | | Armenia | -0.7 | 0.1 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.7 | -0.6 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.8 | -0.8 | -0.8 | | | Aruba | .. | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | | | Australia | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | | | Austria | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.6 | | | Azerbaijan | -0.8 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.7 | -0.8 | -0.8 | -0.7 | -0.7 | -0.9 | -0.8 | -0.9 | | | Bahamas, The | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | | | Bahrain | 0.1 | -1.3 | -0.9 | -1.1 | -0.8 | -1.0 | -0.8 | -0.6 | -0.6 | -0.5 | -0.4 | | | Bangladesh | -0.7 | -1.6 | -0.9 | -1.2 | -1.3 | -1.3 | -1.0 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -1.0 | -1.1 | | | Barbados | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | | | Belarus | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | -0.9 | -0.8 | -0.8 | | | Belgium | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | | | Belize | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | | | Benin | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.3 | | | Bermuda | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | | | Bhutan | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | | | Bolivia | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.3 | | | Bosnia and Herzegovina | -0.5 | -0.4 | 0.0 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.4 | | | Botswana | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | | | Brazil | 0.2 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.7 | -0.4 | -0.4 | -0.3 | | | Brunei Darussalam | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | | | Bulgaria | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | | | Burkina Faso | 0.1 | -0.8 | -0.8 | -0.6 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -1.1 | -1.3 | -1.5 | -1.6 | -1.8 | | | Burundi | -2.0 | -1.4 | -0.8 | -1.9 | -2.0 | -2.0 | -1.6 | -1.6 | -1.5 | -1.3 | -1.2 | | | Cabo Verde | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | | | Cambodia | -0.8 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.0 | | | Cameroon | -0.6 | -0.5 | -1.1 | -1.0 | -1.1 | -1.1 | -1.4 | -1.6 | -1.5 | -1.4 | -1.4 | | | Canada | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | | | Cayman Islands | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | | | Central African Republic | -1.1 | -2.2 | -2.7 | -1.9 | -1.8 | -2.0 | -2.2 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.1 | -2.2 | | | Chad | -1.1 | -1.1 | -1.6 | -1.0 | -1.3 | -1.3 | -1.5 | -1.4 | -1.3 | -1.4 | -1.5 | | | Chile | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | | | China | -0.2 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.6 | -0.5 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.4 | | | Colombia | -1.6 | -1.3 | -1.1 | -1.1 | -0.9 | -0.8 | -0.8 | -1.0 | -0.7 | -1.0 | -0.6 | | | Comoros | 0.0 | -0.3 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.4 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.2 | -0.2 | | | Congo, Dem. Rep. | -2.5 | -2.2 | -2.2 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.3 | -2.1 | -1.6 | -1.8 | -1.7 | -2.0 | | | Congo, Rep. | -0.9 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.0 | | | Cook Islands | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | | | Costa Rica | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | | | Cote d'Ivoire | -1.2 | -1.0 | -1.0 | -0.8 | -0.9 | -1.1 | -0.9 | -1.0 | -1.0 | -0.7 | -0.5 | | | Croatia | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | | | Cuba | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |  - Insert Row Before

- Insert Row After

- Change Style

- Reset Style

- Remove Sort

| Label | | | Font Type | | Font Size | | | Style | | Indent | | | Align | | Vertical Align | | | Textcolor | | Background | | | Height | | | | The Custom Country option allows you to create your own customized country groups from country selection panel. Click on Custom Country. A new box will open. Click on the desired countries listed in the country selection panel. Enter the group name in the Enter Group Title box and click on Add. The new country group will be added to the right panel. To edit an existing country group, click on the Edit link in the current selection panel in right side. Now you can add new countries or remove the countries to an existing customized group. 1. Click on the additional countries listed in the country selection panel. 2. To remove the country from the group double click on the country or select the country and click Remove button. 3. Click on Add to save changes to your customized group. Note: Editing the group name will create a new custom group. You can remove the customized group by clicking on the Delete button in the current selection panel in right side  Help/FeedbackModal title.  Contributor NotesBotswana is typical of the countries that are endowed with abundant natural resources. Although it is commonly accepted that resource-rich economies tend to fail in accelerating growth, Botswana has experienced the most remarkable economic performance in the region. Using the latest cross-country data, this study empirically readdresses the question of whether resource abundance can contribute to growth. It finds that governance determines the extent to which the growth effects of resource wealth can materialize. In developing countries in particular, the quality of regulation, such as the predictability of changes of regulations, and anticorruption policies, such as transparency and accountability in the public sector, are most important for effective natural resource management and growth. I. I ntroductionBotswana, which is one of the most resource-rich countries in the world, has experienced remarkable growth for several decades. Its abundance of diamonds seems to have contributed significantly to Botswana’s strong economic growth. The average growth rate since the 1980s has been 7.8 percent, about 40 percent of which can be explained by mining, though recent economic diversification has slightly reduced that contribution ( Figure 1 ). However, it is commonly accepted that resource-abundant economies tend to grow less rapidly than resource-scarce economies—the phenomenon often referred to as the “resource curse.” This paper casts light on the question of whether and why Botswana has succeeded in transforming its diamond wealth into growth and development.  Botswana: Growth Contribution by Mining, 1980/81–2003/04 Citation: IMF Working Papers 2006, 138; 10.5089/9781451863987.001.A001 - Download Figure

- Download figure as PowerPoint slide

One of the pioneer studies addressing the relationship between natural resource richness and economic growth is Sachs and Warner (1995) . They find that developing countries with abundant primary resources are likely to grow slowly when initial income levels and differences in macroeconomic policies are controlled. Papyrakis and Gerlagh (2004) , focusing on the transmission channels through which resource richness affects economic growth, show that the indirect, negative effects through macroeconomic policies, such as trade openness and educational investment, outweigh the direct, positive resource effects. Leite and Weidmann’s evidence (1999) also supports the resource curse hypothesis. Capital-intensive resource industries tend to induce more corruption, hampering economic development. Theoretically, however, abundant natural resources could promote growth, since resource richness can give a “big push” to the economy through more investment in economic infrastructure and more rapid human capital development. Therefore, any resource-rich country must attain higher growth rates ( Sachs and Warner, 1999 ; Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny, 2000 ). Various reasons have been put forward for failures to effectively transform natural resources to growth. One of the most crucial, when attention is paid to the importance of governance in facilitating economic development, is that natural resource wealth sows the seeds of discord and conflict among domestic stakeholders, such as politicians, developers, local tribes, and citizens (also known as taxpayers). 2 They are naturally motivated to seek unfair resource rents, quickly depleting natural resources and wasting resource revenue. A model of political evolution for analyzing a resource-rich country shows that high resource dependency, concentration of government control over resources, and government’s ability to tax the opposition, such as private entrepreneurs, all inhibit the development of democracy and provoke insurrection. As the result, natural resources may impede economic growth ( Shahnawaz and Nugent, 2004 ). 3 One implication of this is that because of their high earnings from natural resources, resource-dependent countries have less need for tax revenues and are therefore relatively relieved of accountability pressures. Resource rents tend to bring about not only conflict but also corruption. Leite and Weidmann (1999) , modeling the effects of anticorruption policies, show that strengthened monitoring can reduce the steady-state shadow price of capital, producing a higher growth rate during the convergence. From the viewpoint of government fiscal management, in developing countries large resource rents may have the same negative impact as massive foreign aid inflows. As described in the aid fungibility literature (e.g., Devarajan and Swarrop, 1998 ; Gupta and others, 2003 ), resource wealth may relieve governments of tax collection pressures and reduce fiscal discipline. It is natural that populists tend to pander to the insatiable wish of citizens to reduce taxes. Bacon (2001) mentions that oil-producing countries are likely to charge lower domestic gasoline prices, implying that natural resource rents obtained from upstream royalties are subsidizing domestic downstream consumption. An intuitive but important policy implication from all this is that government resource management could catalyze resource endowment to produce economic prosperity. Resource abundance would be advantageous to any economy whose government has a sound long-term plan for extracting natural resources and an effective mechanism for spending revenues on the social and economic infrastructure needed for sustained growth. 4 If governance is poor, resource earnings tend to be unevenly distributed and unfairly dissipated, leading the country into economic stagnation. In Latin America, in fact, high income inequality stemming from uneven distribution of resource returns has ended in failure to accumulate social and human capital, interfering with sustained growth and economic diversification ( Leamer and others, 1999 ). 5 From the economic perspective, the other possible reason for stagnation in resource-rich countries is the Dutch disease problem. In resource-exporting countries, sectors other than natural resources (typically manufacturing) are likely to suffer from real appreciation of the national currency, because natural resource earnings are in part absorbed by the domestic nontradable sector (e.g., Corden and Neary, 1982 ). In the context of slow growth in Africa, Sachs and Warner (1997) interpret the estimated negative growth impact of natural resources to be part of the dynamic Dutch disease syndrome. In general, however, it is rarely easy to see such a direct effect of large resource exports on the terms of trade—which is one of the major measures of external competitiveness ( Figure 2 ), though there are other measures, such as factor costs, composition of exports, and national economic productivity.  Natural Resource Abundance and Terms of Trade, 1998-2002 In addition, the natural resource sector is generally capital-intensive and asset-specific. Extraction of minerals requires large, durable, location-specific investments (often referred to as site specificity). Once sited, the assets are almost immobile. Such investments in facilities and equipment tend to be unique to a particular mine and region ( Masten and Crocker, 1985 ; Joskow, 1987 ). Thus, natural resource development brings about few positive externalities to forward and backward industries ( Sachs and Warner, 1995 ). For the same reasons, the learning-by-doing effect is not expected in this area, either. Based on the viewpoint of political economy that natural resource abundance is linked with economic growth through governance, this paper examines whether Botswana has succeeded in escaping the resource curse. The Dutch disease syndrome is only partly taken into account. Section II illustrates the relationship between resource richness, growth, and governance, with particular attention to Botswana. Section III describes the empirical model and the data and econometric issues. Section IV presents the estimation results. Section V discusses the policy implications. II. R ecent D evelopments in N atural R esources and G overnance in B otswana- A. Natural Resources and Growth

Total world natural resource exports in 2002 amounted to over US$ 700 billion; Botswana exported some US$ 2 billion of diamonds, nickel, copper, gold, and other resources—over 80 percent of its total exports ( Figure 3 ). 6 7 On a per capita basis, the distribution of world natural resource wealth is extremely skewed (see Figure 4 ). 8 Botswana is the 18th largest resource exporter among 161 countries for which data are available.  Natural Resource Exports, 1990–2002 (In billions of U.S. dollars)  Natural Resource Exports per Capita, 1998–2002 (In U.S. dollars; period average) Though Botswana has experienced strong growth thanks to this abundance of resources, such growth may not be sustainable. First, the capital-intensive mining sector does not provide many employment opportunities. While mining production contributed 40 percent to GDP ( Figure 5 ), it absorbed only 4 percent of total employment ( Figure 6 ). 9 Regardless of the government’s efforts to diversify the economy, developing the nontraditional industries has been challenging ( Figure 5 ). 10 In that sense, as Sachs and Warner (1995) hypothesized, too specific and intensified capital investment in the primary sector has restrained Botswana from benefiting from forward and backward linkages and labor market externalities. 11  Botswana: Mining Share of GDP, 1980/81–2003/04  Botswana: Employment Share by Industry, 2001 Second, geographical characteristics, such as lack of access to the sea, also make it harder to relate resource abundance to growth. Because natural resources are usually exported by sea, landlocked countries have extremely high shipping costs. Significantly, about one-third of sub-Saharan African countries, like Botswana, are landlocked ( Sachs and Warner, 1997 ). Bloom, Canning and Sevilla (2003) indeed finds that the proximity of land to the coast has a positive impact on national income and a high air temperature has a negative impact. The empirical analysis that follows takes the landlocked factor into consideration. Finally, it is debatable whether Botswana has suffered from the typical Dutch disease syndrome. 12 Between 1998 and 2002, Botswana exported about US$ 1,200 of natural resources per capita; at the same time, it suffered a 16 percent deterioration in terms of trade. Yet in the first half of the 1990s, the terms of trade index improved by about 10 percent. The reason Botswana has nevertheless achieved marked growth to date seems to be that it has sound institutions and good governance. As to how Botswana has been successful in developing a solid institutional structure, see Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2002) . They point out that Botswana’s good institutions, particularly in the private property area, have stemmed from its precolonial political institutions, limited British colonialism, strong political leadership since independence, and the elite’s motivation to reinforce institutions. According to the Governance Research Indicator Country Snapshot (GRICS) database developed by Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi (2003) , Botswana has enjoyed relatively good governance by global and regional standards ( Table 1 ). The GRICS indices cover six dimensions of governance: voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. Here, each index is normalized between zero and one. 13 Governance Research Indicator Country Snapshot (GRICS), 2002 Botswana Lesotho Namibia South

Africa Swaziland Sub-

Saharan

Africa Low-

Income

countries Middle-

income

countries High-

income

countries Voice and accountability 0.75 0.53 0.66 0.75 0.28 0.42 0.38 0.57 0.82 Political stability 0.78 0.57 0.69 0.52 0.64 0.45 0.40 0.59 0.82 Government effectiveness 0.66 0.40 0.48 0.59 0.36 0.30 0.27 0.42 0.77 Quality of regulation 0.72 0.44 0.59 0.66 0.50 0.38 0.34 0.51 0.85 Rule of law 0.67 0.48 0.60 0.53 0.34 0.33 0.29 0.47 0.84 Control of corruption 0.62 0.39 0.47 0.51 0.36 0.29 0.25 0.39 0.76 Four aspects of governance seem to be particularly important for natural resource management. First, voice and accountability, measured by the political process, civil liberties, and political rights, indicates the ability to discipline those in authority for resource extraction. Without monitoring by the citizens and a process by which those in power are selected and replaced, resource rents tend to be dissipated. Botswana has done particularly well on this aspect of governance; international observers praised as free and fair the 2004 national election, the first conducted under the Southern African Development Community (SADC) guidelines for democratic elections. Second, government effectiveness, measured by the quality of public services and the competence of civil servants, also needs to be high. If the government cannot produce and implement good resource management policies, resource wealth will be overexploited and rapidly exhausted. In Botswana, use of mineral revenues has followed an implicit self-disciplinary rule, the Sustainable Budget Index (SBI), under which any mineral revenue is supposed to finance “investment expenditure,” defined as development expenditure and recurrent spending on education and health. Other recurrent spending is funded from nonmineral revenues. In addition, there is a government asset fund, the Pula Fund, where financial assets are invested only on a long-term basis in a transparent and accountable manner. Although the first rule has been broadly followed for decades, there has been some minor departure in recent years ( Figure 7 ). Violation of the rule tends to have been accompanied by a large fiscal deficit, as in 2001/02 and 2002/03.  Botswana: Mineral Revenue and Investment Expenditure, 1985/86–2003/04 (In millions of pula) Third, because natural resource development must of necessity involve a long-term relationship with private parties, market-unfriendly policies like price controls and excessive regulatory burdens are undesirable. Contracts related to natural resources commonly extend for more than 10 years. 14 The term for diamond-mining leases in Botswana is 25 years. 15 The quality of Botswana’s regulation is generally acceptable. For instance, the Botswana Telecommunications Authority (BTA) of 1996 has been praised as one of the first independent regulatory authorities in Africa ( ITU, 2001 ). 16 However, there may remain some regulations that restrict labor mobility and business opportunities. 17 In the mining sector, the government of Botswana retains 50 percent of the shares in Debswana, the largest diamond firm in the country, and the Ministry of Minerals, Energy and Water Resources has direct responsibility generally for natural resource regulation and management. Finally, anticorruption policies are essential for fair and transparent distribution of resource benefits. In Botswana, corruption in the public sector is not a serious problem. The budgetary and procurement process is relatively transparent. An independent anticorruption authority established in 1994, the Directorate of Corruption and Economic Crime, has authority to report corruption cases directly to the president. The constitution also makes the attorney general independent of the government and politicians. This sound anticorruption framework is considered to be conducive to proper resource management in Botswana. But do these governance factors really affect growth and natural resources? As shown in Figure 8 , where the anticorruption indicator is taken as an example, the recent growth rate cannot simply be explained by natural resource abundance, even though there is a slight positive correlation between growth and governance, and resource abundance is positively associated with governance.  Natural Resources, Growth, and Anticorruption Policies, 1998–2002 Economic growth has not been high in some other resource-abundant countries, such as Indonesia, Venezuela, and Nigeria, partly because of inadequate governance. On the other hand, resource-scarce countries have sometimes attained relatively high economic growth, like the Maldives, which has good governance. There are other anomalies: While Malaysia has abundant natural resources and good governance, it has low economic growth for this sample period. Albania is a resource-scarce country with poor governance that has somehow achieved marked growth. Therefore, not only governance but also other macroeconomic elements must affect the relationship between natural resource wealth and economic growth. III. M ethodologyTo examine the relationship between natural resource wealth, growth, and governance, this paper follows the standard empirical growth literature (e.g., Mankiw, Romer, and Weil, 1992 ; Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995 ; Barro, 1997 ) and uses the following linear growth regression model: 18 where g is the real per capita growth rate, MIN is a proxy of mineral resource abundance, 19 θ is one of the governance indicators, n is population growth, and r is the average tax rate. TRA is a proxy representing the degree of trade openness, and X includes exogenous variables to control for heterogeneity across countries. 20 The equation has an interaction term between resource abundance and governance that allows us to address the primary question motivating this paper: whether and how natural resource richness and governance factors influence economic growth. Of particular note: the average tax rate is supposed to capture the conventional effect of government intervention in the economy (e.g., Romer, 1996 ). If the tax rate is significantly high, economic growth is likely to stagnate. On the other hand, TRA is supposed to represent generally expected positive impacts of trade liberalization on growth. When particular attention is paid to the Dutch disease syndrome, another equation can be estimated that incorporates the indirect terms of trade effect: μ ^ is obtained as a residual from the following transmission channel equation: where TOT denotes a change in terms of trade. 21 The most important econometric issue in estimating Equations (1) through (3) with aggregated cross-country data is how to deal with biases caused by measurement errors and endogeneity. In this analysis, growth is affected by governance and natural resource extraction; at the same time, resource exploitation and governance are likely to be determined systematically by the stage of economic development. Consequently, the independent variables may be contemporaneously correlated with the error term. To solve this problem, the analysis uses five-year lagged values of the independent variables as instrumental variables, because there is usually no correlation between the disturbance and the lagged values. 22 The original variables for the period from 1998 to 2002 are instrumented by the lagged equivalents from 1992 to 1996. Another important issue is how to treat potential outliers in data. As shown in Figure 4 , the natural resource distribution is very skewed, so that resource-rich countries, though a main target of this research, tend to lie substantially outside the likely population. According to the conventional statistical test where outliers are defined observations lying outside the level of two per million for a normal population, the acceptable maximum of mineral exports per capita is estimated at US$ 1,312. In the current sample, 8 of 89 countries may be viewed as severe outliers. Fortunately, however, it has been found that the exclusion of outliers in terms of natural resource endowment has little effect on the estimation results. Therefore, no observation is excluded from the analysis. 23 IV. E mpirical R esults- A. Basic Regression Results

The Appendix describes the sample data. Six instrumental variable (IV) regressions are performed with data that include high-income countries. The results are shown in Table 2 . There are several interesting findings: Estimation Results for All Countries 1 , 2 , 3 1 The dependent variable is GDP per capita growth. 2 The White-heterooscedasticity consistent standard errors are shown in parentheses. 3 * 10% level significance; ** 5% level significance. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Mineral exports per capita ( ) -0.0010*

(0.0006) -0.0015

(0.0010) -0.0010

(0.0007) -0.0017

* (0.0009) -0.0014

(0.0010) -0.0013

(0.0008) Voice and accountability ( ) -4.1559

(3.3823) * 0.0011 *

(0.0006) Political stability ( ) -1.3706

(3.2083) * 0.0018

(0.0012) Government effectiveness ( ) -2.3886

(5.4436) * 0.0013 *

(0.0008) Regulatory quality ( ) -4.3060

(6.7246) * 0.0021

** (0.0010) Rule of law ( ) 2.1286

(3.8417) * 0.0016

(0.0011) Control of corruption ( ) 2.2529

(3.9123) * 0.0016*

(0.0009) Population growth -1.3063 **

(0.5723) -1.2180 **

(0.5388) -1.1197 *

(0.6530) -1.1724**

(0.5783) -1.1870*

(0.6594) -1.2650*

(0.6630) Government revenue per GDP -0.0988 **

(0.0464) -0.0841 *

(0.0465) -0.0974 **

(0.0465) -0.0934 *

(0.0472) -0.1004**

(0.0444) -0.1007 **

(0.0463) Trade openness 0.0185 **

(0.0081) 0.0164 *

(0.0086) 0.0151 **

(0.0072) 0.0158 *

(0.0086) 0.0147 **

(0.0072) 0.0152**

(0.0070) Initial human capital 0.0047

(0.0245) -0.0024

(0.0255) 0.0066

(0.0300) 0.0100

(0.0328) -0.0061

(0.0285) -0.0079

(0.0293) Initial GDP per capita -0.00006

(0.00004) -0.00007 *

(0.00004) -0.00005

(0.00006) -0.00005

(0.00004) -0.00008 *

(0.00004) -0.00009 *

(0.00005) Landlocked 0.1217

(0.7465) 0.0808

(0.7172) 0.0879

(0.6936) 0.1845

(0.7271) 0.0386

(0.7053) 0.1255

(0.6930) Americas -1.5677 *

(0.8958) -1.8647 **

(0.8235) -2.0956

** (0.8418) -1.8981 **

(0.8328) -1.9275 **

(0.7571) -1.9675 **

(0.7596) East Asia and Pacific -1.6651 *

(0.9071) -1.3772

(0.9405) -1.6790**

(0.8841) -1.8188 **

(0.9205) -1.6744*

(0.9524) -1.5725 *

(0.9516) South Asia 0.3891

(1.4394) -0.0953

(1.4244) 0.1412

(1.3638) 0.1652

(1.2550) -0.3917

(1.3129) -0.2548

(1.3379) Sub-Saharan Africa -0.5580

(1.6283) -0.7295

(1.5381) -0.5501

(1.5429) -0.5405

(1.5956) -0.8591

(1.4896) -0.8519

(1.5339) Low-income countries -3.7840 *

(2.2174) -2.9167

(1.9505) -2.8440

(1.9895) -3.4681

(2.2246) -1.8691

(2.0291) -1.9401

(1.8915) Lower-middle-income countries -2.5767 *

(1.4653) -1.7844

(1.3883) -1.7072

(1.2691) -2.1601

(1.6301) -1.0157

(1.3474) -1.0247

(1.2596) Upper-middle-income countries -2.2394 *

(1.3048) -1.9079

(1.2265) -1.6847

(1.1365) -1.8880

(1.2560) -1.5535

(1.1312) -1.5997

(1.0934) Constant 9.8483 **

(3.9011) 7.8903 **

(3.4008) 7.7502

** (3.3862) 9.1275 **

(4.1179) 6.3276 *

(3.3121) 6.6418 **

(3.1979) | Number of observations | 88 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 87 | 86 | -statistics 4.68 6.24 6.27 7.25 5.52 4.17 R-squared 0.3613 0.3725 0.3842 0.3482 0.4307 0.4287 First, the coefficients of natural resources per capita tend to be negative when the interactive term of resource endowment and governance is included. For several models, those coefficients are statistically significant. 24 This evidence supports the resource curse hypothesis found in earlier studies. Second, the effects of governance are not statistically significant. This is not necessarily contradictory to certain expectations of the international donor community. It means that governance is less likely to matter for growth over the very short horizon of a few years, as modeled in this paper. More convincing evidence might be derived from very long-run regressions. Third, the interaction terms between resource abundance and governance have significant positive coefficients, meaning that if the country has good governance, particularly in terms of voice and accountability, government effectiveness, the quality of regulation, and anticorruption policies, resource wealth is conducive to economic development. Because this result is statistically robust, it can be concluded that resource abundance does not guarantee faster growth, but with proper government resource management, growth can be generated from resource richness. In other words, the absence of the positive relationship between resource abundance and economic development is attributable to a lack of good governance. As illustrated in Figure 9 , when the other conditions are controlled, Botswana seems to have taken advantage of its relatively good governance institutions to maximize the catalytic effect and transform resource abundance into growth. The figure shows the relationship between unexplained growth and the interaction term between resource exports and the governance indicator.  Interactive Effect of Resource Abundance and Governance on Growth As for other explanatory variables, an increase in the average tax rate has a negative impact on growth, as earlier growth studies found (see, e.g., Barro, 1990 ; Davoodi and Zou, 1998 ). This supports the conventional theoretical prediction that an increase in public purchases slows economic development. The coefficients of trade openness are significant and positive. This evidence supports the conventional argument promoting trade liberalization. Contrary to expectations, on the other hand, the coefficients of the landlocked dummy variable are positive, though not significant. Statistically, the landlocked effect seems to be absorbed by the income group dummy variables, implying that slow growth in landlocked economies is attributable to more general economic and social disadvantages shared by low-income countries rather than to geographical constraints. The population growth coefficient is negative and significant in a statistical sense, consistent with earlier studies. Some systematic differences among regions are also observed. - B. The Dutch Disease Hypothesis

Table 3 shows the estimation results of the indirect effect of resource abundance on terms of trade. Paradoxically, resource richness improves terms of trade. 25 With this indirect effect incorporated, the results of the IV regressions, presented in Table 4 , are quite similar to those in Table 2 . The indirect effect of terms of trade retrieved from the MIN coefficients in Table 3 and the μ ^ coefficients in Table 4 is very small. This can be interpreted to mean that for this period the Dutch disease syndrome has little effect on the linkage between natural resource abundance and economic development. Indirect transmission channels 1 , 2 , 3 1 The dependent variable is the average change of terms of trade. 3 *** 1% level significance. All sample Developing

countries only Mineral exports per capita ( ) 0.0085***

(0.0022) 0.0246***

(0.0067) | Constant | -1.6812

(1.9619) | -1.9993

(2.2126) | Number of observations 86 58 -statistics 14.20 13.56 R-squared 0.3052 0.2782 Estimation Results Including Indirect Terms of Trade Effect 1 , 2 , 3 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Mineral exports per capita ( ) -0.0010

(0.0006) * -0.0016

(0.0010) -0.0012

(0.0007) -0.0021 *

(0.0011) -0.0018 *

(0.0010) -0.0017 *

(0.0009) Voice and accountability ( ) -3.9395

(3.5294) * 0.0012 *

(0.0007) Political stability ( ) -1.1234

(3.2406) * 0.0019 *

(0.0012) Government effectiveness ( ) -1.3421

(5.6547) * 0.0015 *

(0.0009) Regulatory quality ( ) -3.9673

(6.7780) * 0.0026

* (0.0014) Rule of law ( ) 3.4048

(4.2299) * 0.0022 *

(0.0012) Control of corruption ( ) 2.8575

(3.7133) * 0.0021 *

(0.0012) 0.0011

(0.0235) 0.0069

(0.0231) 0.0086

(0.0246) 0.0110

(0.0272) 0.0141

(0.0235) 0.0110

(0.0225) Population growth -1.2843 **

(0.5385) -1.1899 **

(0.5005) -1.1085 *

(0.5886) -1.1229 **

(0.5119) -1.1430 *

(0.5896) -1.2300 **

(0.5742) Government revenue per GDP -0.1004 **

(0.0459) -0.0822 *

(0.0450) -0.0964 **

(0.0445) -0.0898 *

(0.0461) -0.1025 **

(0.0436) -0.1020 **

(0.0443) Trade openness 0.0161

(0.0109) 0.0133

(0.0109) 0.0116

(0.0094) 0.0123

(0.0104) 0.0112

(0.0090) 0.0121

(0.0090) Initial human capital 0.0072

(0.0229) 0.0017

(0.0238) 0.0088

(0.0277) 0.0138

(0.0306) -0.0020

(0.0263) -0.0032

(0.0257) Initial GDP per capita -0.00008 **

(0.00004) -0.00009 **

(0.00004) -0.00009

(0.00006) -0.00009 **

(0.00004) -0.00013

*** (0.00004) -0.00013 ***

(0.00005) Landlocked 0.2485

(0.7984) 0.2671

(0.7841) 0.3119

(0.7484) 0.4080

(0.8049) 0.2611

(0.7659) 0.3576

(0.7651) Americas -1.6464 *

(0.9198) -1.8355 **

(0.8378) -2.0263 **

(0.8396) -1.8738 **

(0.8468) -1.8126 **

(0.7524) -1.9357 **

(0.7450) East Asia and Pacific -1.6597 *

(0.8768) -1.3118

(0.8964) -1.6222 *

(0.8301) -1.6799 *

(0.8889) -1.6598 *

(0.9010) -1.5257 *

(0.8910) South Asia 0.3111

(1.5023) 0.0010

(1.5220) 0.1140

(1.4070) 0.2506

(1.3614) -0.4323

(1.3295) -0.2181

(1.3693) Sub-Saharan Africa -0.5344

(1.7206) -0.5126

(1.6849) -0.3763

(1.6166) -0.2756

(1.7035) -0.5185

(1.5721) -0.5938

(1.5746) Low-income countries -4.0601 *

(2.4521) -3.2876

(2.0493) -3.1483

(2.1269) -3.9457 *

(2.3864) -2.2063

(2.1209) -2.4381

(2.0413) Lower-middle-income countries -2.8217 *

(1.4904) -2.0951

(1.3400) -1.9985

(1.2342) -2.5319

(1.6204) -1.3101

(1.3321) -1.4209

(1.2224) Upper-middle-income countries -2.4092 *

(1.4351) -2.1939 *

(1.2961) -2.0034

(1.2424) -2.2124 *

(1.3078) -1.9352

(1.1941) -1.9714 *

(1.1692) | Constant | 10.0491 **

(3.8623) | 7.9376

** (3.1950) | 7.6892 **

(3.0562) | 9.1712 **

(3.9762) | 6.0418 **

(3.0095) | 6.7396 **

(2.9489) | Number of observations 86 85 86 86 85 84 -statistics 4.28 5.05 6.40 7.45 4.52 3.75 R-squared 0.3633 0.3811 0.4045 0.3598 0.4509 0.4436 One remaining econometric concern is that developing countries might not share the same growth structure as developed countries. Table 5 presents the estimation results for developing countries only. Although the statistical significance of some explanatory variables is changed, the main results hold. While the coefficients of natural resource abundance tend to be negative, only two governance indicators that interact with the resource variable retain significant coefficients: regulatory quality and control of corruption. Thus, in developing countries, sound government regulation and anticorruption policies are of particular importance for natural resource management. Estimation Results with Data on Developing Countries 1 , 2 , 3 3 * 10% level significance; ** 5% level significance; *** 1% level significance. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Mineral exports per capita ( ) -0.0037

(0.0039) -0.0093

(0.0074) -0.0042

(0.0063) -0.0208 *

(0.0116) -0.0072

(0.0054) -0.0134 **

(0.0053) Voice and accountability ( ) -3.3710

(3.4270) * 0.0090

(0.0091) Political stability ( ) -4.6256

(7.5320) * 0.0127

(0.0095) Government effectiveness ( ) 0.7405

(9.2971) * 0.0087

(0.0103) Regulatory quality ( ) -15.1695

(12.5871) * 0.0326 *

(0.0175) Rule of law ( ) -2.6370

(5.4129) * 0.0120

(0.0079) Control of corruption ( ) -4.4043

(6.6827) * 0.0227 **

(0.0089) Population growth -1.4181 **

(0.6576) -1.4074**

(0.5846) -1.3637*

(0.7280) -1.4279**

(0.5680) -1.2484*

(0.6498) -1.3250**

(0.6482) Government revenue per GDP -0.0947

(0.0684) -0.0580

(0.0870) -0.1052

(0.0697) -0.0949

(0.0826) -0.0801

(0.0760) -0.0702

(0.0754) Trade openness 0.0133

(0.0140) 0.0126

(0.0184) 0.0066

(0.0150) 0.0170

(0.0188) 0.0090

(0.0141) 0.0056

(0.0154) Initial human capital -0.0130

(0.0426) -0.0204

(0.0395) -0.0108

(0.0430) 0.0113

(0.0502) -0.0162

(0.0399) -0.0254

(0.0390) Initial GDP per capita -0.0011 ***

(0.0003) -0.0014 ***

(0.0003) -0.0012***

(0.0002) -0.0014 ***

(0.0004) -0.0013 ***

(0.0003) -0.0013 ***

(0.0003) Landlocked -0.4006

(0.7994) -0.4483

(0.8586) -0.1893

(0.7470) -0.4912

(1.0210) -0.2744

(0.8193) -0.2984

(0.8623) Americas -1.5513

(1.1267) -1.4440

(1.2927) -1.6732

(1.2928) -1.2612

(1.2269) -1.8990*

(1.1178) -1.8942*

(1.1571) East Asia and Pacific -2.4057 *

(1.4131) -1.6152

(1.7079) -2.4449 *

(1.3301) -3.0781 *

(1.6079) -1.8955

(1.5536) -1.8154

(1.6470) South Asia -0.9137

(1.4769) -1.6476

(1.9658) -1.3263

(1.2922) -1.0256

(1.3511) -0.9708

(1.4257) -1.3461

(1.4583) Sub-Saharan Africa -2.1561

(2.2009) -2.1766

(2.1107) -1.8856

(1.6975) -2.0710

(2.0235) -2.0380

(1.8583) -2.2162

(1.8700) Low-income countries -4.2733 **

(1.8966) -6.1461**

(2.7988) -4.1031 *

(2.2297) -7.7330 ***

(2.8199) -5.3629 **

(2.2896) -6.1244**

(2.3340) Lower-middle-income countries -2.5179 *

(1.2826) -3.6120 *

(2.1002) -2.3876 *

(1.3419) -4.4638 **

(1.8253) -3.0153 **

(1.3028) -3.6008 **

(1.5274) | Constant | 13.0153 **

(5.3963) | 15.0449 **

(6.2013) | 11.5868 **

(4.9761) | 20.2120 ***

(6.9082) | 13.3910 ***

(4.7379) | 15.4559

*** (4.6294) | Number of observations 59 58 59 59 58 57 –statistics 4.03 3.50 4.14 2.92 4.00 4.04 R-squared 0.5202 0.4422 0.5799 0.3501 0.5350 0.4787 More formally, at the 1 percent significance level, the standard structural test tends to accept the hypothesis that all the coefficients except those associated with regional and income group dummy variables are the same for both high-income and developing countries. The Wald statistics are estimated at 1.10 to 3.08, depending on the governance indicators used. 26 In Table 5 , the strong negative coefficients associated with initial GDP per capita imply that there is a conditional convergence in national incomes. Concurrently, however, the estimation results also indicate that low-income countries tend to record lower GDP growth rates. This means that even after the difference in income levels is controlled, there remains a systematic difference in nonincome growth between low- and middle-income countries. Low-income countries may face institutional and socioeconomic obstacles in achieving high economic development, such as political and macroeconomic instabilities and institutional weaknesses.  V. P olicy I mplicationsGiven these findings, an important policy question is how to establish effective natural resource management mechanisms in developing countries. IMF (2005) points out that it is important to introduce explicit fiscal rules for the treatment of mineral revenues. Any windfall should be deposited in a special account and used for designated economic and social development. Chad has actually passed a law to earmark oil revenue for debt service and spending in priority sectors. This type of political step may become a credible and irreversible commitment of the government. Similarly, disclosure of the terms of contracts and profitsharing arrangements with natural resource developers and publication of independent external audits have the same effects for increasing transparency in natural resource management. Further, if resource-developing enterprises are privatized, resource extraction must be strictly regulated. Ahmad and Mottu (2002) emphasize the necessity of centralizing resource revenue control and supplementing it with predictable and transparent transfers from the center. Decentralized resource management reduces the capacity of the central government to run countercyclical fiscal policies and to arrange equalization transfers among regions. Botswana has already established the prudent fiscal framework governing how to use mining revenue, but could take further steps to implement more precautionary saving policies for ensuring sustainable and stable growth over the long term. It cannot be overestimated that large market downturns and a depletion of the assets of stabilization funds are always possible ( Katz and others, 2004 ). This is of particular importance for Botswana: because of the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS and the related health expenditures, which will increase over the medium term, the fiscal position is expected to tighten increasingly. It is also important to recognize that government mineral revenues are exposed to several uncertain factors. Decomposing changes in government mineral revenue R: exchange rate ER, international diamond priced, the quantity of diamond exports Q, and an average share of export earnings 6, yields the following: An increase in mineral revenue in national currency terms can be explained by: (i) depreciation of the pula, (ii) an international price increase, (iii) enhancement of production capacity, and (iv) other remaining factors captured as changes in the average profit share ( ). 27 As shown in Table 6 , 28 percent of changes in mineral revenue are associated with changes in the exchange rate, and 21 percent are attributable to international prices. 28 Both factors, which are unpredictable, are characterized as windfalls. Resource rents are vulnerable to exogenous shocks, and the necessity of managing resource rents deliberately under a rigid saving mechanism cannot be overemphasized. 29 Botswana: Contribution to Changes in Mineral Revenue, 1988-2003 (In percent) 2001 2002 2003 Average

Contribution

1988-2003 a. Annual change in mineral revenue

-7.7 0.5 8.4 100.0 b. Change in exchange rates (appreciation -) 14.3 8.5 -21.8 27.5 c. Change in international diamond prices -7.5 -12.2 12.5 21.3 d. Change in diamond export quantities 6.7 8.3 7.1 19.7 e. Change in other factors (e.g. profit sharing arrangements) = a-b-c-d -21.1 -4.1 10.7 31.4 Given these unavoidable uncertainties, the Botswana government, though having accumulated large assets under a self-disciplinary fiscal rule (e.g., SBI) through a series of national development plans, may be able to amplify the governance and resource effects on growth by more explicit insulation of fiscal expenditure from the volatility and uncertainty of mining revenues. For instance, one possible option may be to adopt a nondiamond deficit target rule to accelerate the revenue base diversification, and another is to reserve particular types of resource-related rents (e.g., windfalls based on a given medium-term projection of mineral prices) to leave future generations as well off as the current one. This can be complemented by special-account treatment of diamond revenue in the budget. For increasing transparency, accountability, and predictability in natural resource management, it is in general useful to establish an independent mineral regulatory agency and to disclose and monitor the terms of reference for mining extraction and revenue sharing ( Katz and others, 2004 ). Although the institutional system of the Botswana government appears robust, a more transparent and neutral regulatory agency could advance efficient governance further, with current virtues of good governance maintained. Indeed, the above evidence indicates that in resource management, regulatory quality—which calls on market-friendly competition policies and deregulation—is the most significant of all the dimensions of governance examined above. It is worth recalling that not all mineral projects in which the Botswana government has been extensively involved have been profitable ( Gaolathe, 1997 ). Finally, it is important to keep strengthening anticorruption policies, demonstrably one of the keys to good natural resource management. VI. C onclusionThis paper has cast light on the accepted notion that countries endowed with abundant natural resources grow more slowly than resource-scarce countries, for a number of possible reasons: a strong likelihood of discord and conflicts about resources, the Dutch disease, the lack of forward and backward linkages and learning-by-doing effects in the natural resource sector, and social lethargy stemming from the abundance of resources. The big push theory nevertheless predicts that natural resource richness must have a positive effect on economic growth because it provides sufficient financial resources for strengthening economic infrastructure and human capital. As to the role of governance in transforming resource abundance into economic development, data from 89 countries reveal that an abundance of natural resources does not guarantee growth. What determines the degree to which natural resources can contribute to economic development is governance. Good governance—specifically a strong public voice with accountability, high government effectiveness, good regulation, and powerful anticorruption policies—tends to link natural resources with high economic growth. The last two dimensions of governance are especially important for natural resource management in developing countries. Botswana has benefited from the coexistence of good governance and abundant diamonds to materialize growth. No clear evidence can be found that deterioration in the terms of trade would negatively affect economic development, as the Dutch disease model would hypothesize. This paper uses data from 89 countries for which the latest macroeconomic statistics, including fiscal and trade data, are available. 30 The data cover 18 low-income, 22 lower-middle-income, 19 higher-middle income, and 29 high-income countries; they also cover 19 countries in East Asia and the Pacific and 10 in sub-Saharan Africa. The sample period is from 1998 to 2002. 31 The dependent variable is the average growth rate of real GDP per capita from 1998 to 2002. Taking the average values is intended to avoid measurement errors due to short-term economic fluctuations. Unless otherwise indicated, all the macroeconomic data used for this study were taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators . Five endogenous variables are taken into account. First, natural resource richness is represented by average natural resource exports for the period, divided by total population. This is good proximity on the assumption that natural resources extracted are mostly exported abroad. The resource export data comes from the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) database of the World Bank. Natural resources basically cover oil, non-oil commodities, and precious stones, but not agriculture. Previously (see, e.g., Sachs and Warner, 1997 ; Papyrakis and Gerlagh, 2004 ), resource richness has been defined as the share of mineral exports or production in GDP, but this is not consistent with the standard growth theory. 32 The figure of natural resource exports per capita seems more reasonable. Second, the level of governance affecting resource management is measured by the six governance indicators provided by Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi (2003) . The indicators are calculated based on existing data sources representing some perceptions of the level of public governance as well as the quality of government policies; they are therefore generally consistent with the general level of governance. This paper uses the 2002 indices normalized between zero and one. 33 Third, average tax rate is measured by government current revenues, excluding grants, divided by GDP. Fourth, the extent to which trade circumstances are open and liberalized is measured by the ratio of total trade to GDP. Average population growth rate for the period is used for n . Finally, for estimating the indirect growth effects of trade conditions, a terms of trade index (an export price index divided by an import price index), is employed, using the World Economic Outlook (WEO) database. TOT is defined as a percent change in terms of trade during the 5-year period. The model includes three exogenous control variables. To control for the differences in initial state conditions across countries, this paper uses initial accumulation of human capital and GDP per capita just before the sampling period. The Hausman exogeneity test cannot reject the hypothesis that at minimum these two variables are exogenous. 34 Initial human capital is measured by the percentage of gross secondary school enrolments compared to the official school age population in 1997; GDP per capita is in U.S. dollar terms for 1997. 35 Finally, the landlocked dummy variable is adopted to take geographical differences into consideration. To control unobservable region-specific and income-group-specific characteristics, regional and income-group dummy variables are also included. This treatment is expected to be useful for mitigating the measurement problem inherent in any cross-country analysis. Table A.2 shows the summary statistics. The average growth rate of the sample countries is about 1.8 percent, though there is significant variation, from −5 percent to over 10 percent. The natural resources per capita figure varies widely, from US$ 0.02 to over US$ 8,000; the mean is US$ 609. Population growth also differs considerably in the sample countries. While several countries have population growth of more than 5 percent, some developing countries, such as Bulgaria, have experienced a net reduction in population. The average tax rate for the sample is about 25 percent. Trade openness differs from 24 percent to 270 percent, implying that some counties, such as Luxembourg and Malaysia, are highly involved in the international trade system and others are not. The initial conditions in terms of human capital and national incomes also show considerable variations. Finally, the sample includes 18 landlocked countries. List of Sample Countries Americas Europe and Central Asia Argentina Albania Bolivia Austria Brazil Azerbaijan Canada Belgium Chile Bulgaria Colombia Croatia Costa Rica Cyprus Dominican Republic Czech Republic Jamaica Estonia Mexico Finland Nicaragua France Panama Germany Paraguay Greece Peru Hungary United States Iceland Uruguay Ireland Venezuela, RB Italy Kyrgyz Republic East Asia and Pacific Latvia Australia Lithuania China Luxembourg Indonesia Moldova Korea, Rep. Netherlands Malaysia Norway Mongolia Poland New Zealand Portugal Philippines Romania Thailand Russian Federation Vanuatu Slovak Republic Slovenia South Asia Spain India Sweden Nepal Switzerland Pakistan Turkey Sri Lanka United Kingdom Sub-Saharan Africa Middle East and North Africa Botswana Algeria Burundi Bahrain Cameroon Egypt, Arab Rep. Côte d’Ivoire Israel Ethiopia Jordan Guinea Kuwait Kenya Malta Madagascar Morocco Mauritius Oman Senegal Tunisia Zimbabwe United Arab Emirates Descriptive Statistics Variable Mean Sth. Dev. Min Max GDP per capita growth 1.84 2.61 -5.00 10.54 Mineral exports per capita 609.42 1,557.60 0.02 8,482.77 Population growth 1.18 1.07 -0.94 5.16 Government revenue per GDP 25.87 9.55 3.31 44.02 Trade openness 83.72 43.56 23.86 266.79 Initial human capital 74.62 32.23 6.64 157.09 Initial GDP per capita 8,877.06 11,266.93 113.06 47,960.78 Landlocked 0.20 0.41 0.00 1.00 Governance indices Voice and accountability 0.66 0.23 0.20 1.00 Political stability 0.63 0.25 0.05 1.00 Government effectiveness 0.55 0.23 0.11 0.99 Regulatory quality 0.64 0.21 0.13 1.00 Rule of law 0.58 0.24 0.15 1.00 Control of corruption 0.51 0.24 0.15 1.00 Income group dummy High-income counties 0.33 0.47 0.00 1.00 Low-income countries 0.20 0.41 0.00 1.00 Lower-middle-income countries 0.25 0.44 0.00 1.00 Upper-middle-income countries 0.22 0.41 0.00 1.00 Regional dummy Americas 0.19 0.40 0.00 1.00 East Asia and Pacific 0.11 0.32 0.00 1.00 South Asia 0.05 0.21 0.00 1.00 Sub-Saharan Africa 0.13 0.33 0.00 1.00 R eferencesAcemoglu , D. , S. Johnson , and J. Robinson , 2002 , “ An African Success Story: Botswana ,” CEPR Discussion Paper 3219 ( London : Centre for Economic Policy Research ). - Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Ahmad , E. , and E. Mottu , 2002 , “ Oil Revenue Assignments: Country Experiences and Issues .” IMF Working Paper 02/203 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ). Bacon , R. , 2001 , “ Petroleum Taxes: Trends in Fuel Taxes (and Subsidies) and the Implications ,” Viewpoint , Note Number 240 ( Washington : World Bank ). Banerjee , A. , and E. Duflo , 2003 , “ Inequality and Growth: What Can the Data Say? ” Journal of Economic Growth , Vol. 8 ( September ), pp. 267 - 99 . Barro , R. , 1990 , “ Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth ,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 98 ( October ), pp. S103 - S125 . Barro , R. , 1997 , Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Study ( Cambridge, Massachusetts : MIT Press ). Barro , R. , and X. Sala-i-Marin , 1995 , Economic Growth ( New York : McGraw-Hill ). Bloom , D. , D. Canning , and J. , Sevilla , 2003 , “ Geography and Poverty Traps ,” Journal of Economic Growth , Vol. 8 ( December ), pp. 255 - 78 . Burnside , C. , and D. Dollar , 2000 , “ Aid, Policies and Growth ,” American Economic Review , Vol. 90 ( September ), pp. 847 - 68 . Corden , W. , and J. Neary , 1982 , “ Booming Sector and De-Industrialisation in a Small Open Economy ,” Economic Journal , Vol. 92 ( December ), pp. 825 - 48 . Davoodi , H. , and H. Zou , 1998 , “ Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Study ,” Journal of Urban Economics , Vol. 43 ( March ), pp. 244 - 57 . Devarajan , S. , and V. Swarrop , 1998 , “ The Implications of Foreign Aid Fungibility for Development Assistance ,” Policy Research Working Paper 2022 ( Washington : World Bank ). Easterly , W. , 2003 , “ Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth? ” Journal of Economic Perspective , Vol. 17 ( Summer ), pp. 23 - 48 . Easterly , W. , R. Levine , and D. Roodman , 2004 , “ Aid, Policies, and Growth: Comment ,” American Economic Review , Vol. 94 ( June ), pp. 774 - 84 . Farzin , Y.H. , 1999 , “ Optimal Saving Policy for Exhaustible Resource Economies ,” Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 58 ( February ), pp. 149 - 84 . Gaolathe , B. , 1997 , “ Development of Botswana’s Mineral Sector ,” in Aspects of the Botswana Economy Selected Papers , ed. by J.S. Salkin , D. Mpabanga , D. Cowan , J. Selwe , and M. Wright ( Oxford, United Kingdom : James Currey Publishers ). Glaeser , E. , R. La Porta , F. Lopez-de-Silanes , and A. Shleifer , 2004 , “ Do Institutions Cause Growth? ” Journal of Economic Growth , Vol. 9 ( September ), pp. 271 - 303 . Goldberg , V. , and J. Erickson , 1987 , “ Quantity and Price Adjustment in Long-Term Contracts: A Case Study of Petroleum Coke ,” Journal of Law and Economics , Vol. 30 ( October ), pp. 369 - 98 . Gupta , S. , B. Clements , A. Pivovarsky , and E. Tiongson , 2003 , “ Foreign Aid and Revenue Response: Does the Composition of Aid Matter? ” IMF Working Paper 03/176 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ). International Monetary Fund , 1999 , “ Botswana: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix ,” IMF Staff Country Report No. 99/132 ( Washington ). International Monetary Fund , 2005 , Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, April 2005 ( Washington ). International Telecommunication Union (ITU) , 2001 , Effective Regulation—Case Study: Botswana ( Geneva ). Joskow , P. , 1987 , “ Contract Duration and Relationship-Specific Investments: Empirical Evidence from Coal Markets ,” American Economic Review , Vol. 77 ( March ), pp. 168 - 85 . Kaufmann , D. , A. Kraay , and A. Mastruzzi , 2003 , “ Governance Matters III: Governance Indicators for 1996-2002 ” ( mimeograph ; Washington : World Bank ). Katz , M. , U. Bartsch , H. Malothra , and M. Cuc , 2004 , Lifting the Oil Curse: Improving Petroleum Revenue Management in Sub-Saharan Africa ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ). Leamer , E. , H. Maul , S. Rodriguez , and P. Schott , 1999 , “ Does Natural Resource Abundance Increase Latin American Income Inequality? ” Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 59 ( June ), pp. 3 - 42 . Leite , C. , and J. Weidmann , 1999 , “ Does Mother Nature Corrupt? Natural Resources, Corruption, and Economic Growth ,” IMF Working Paper 99/85 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ). Mankiw , G. , D. Romer , and D. Weil , 1992 , “ A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth ,” Quarterly Journal of Economics , Vol. 107 ( May ), pp. 407 - 37 . Masten , S. , and K. Crocker , 1985 , “ Efficient Adaptation in Long-Term Contracts: Take-or-Pay Provisions for Natural Gas ,” American Economic Review , Vol. 75 ( December ), pp. 1083 - 93 . Murphy , K. , A. Shleifer , and R. Vishny , 2000 , “ Industrialization and the Big Push ,” in Readings in Development Microeconomics Vol. 1 (Micro-theory) , ed. by P. Bardhan and C. Udry ( Cambridge, Massachusetts : MIT Press ). Papyrakis , E. , and R. Gerlagh , 2004 , “ The Resource Curse Hypothesis and Its Transmission Channels ,” Journal of Comparative Economics , Vol. 32 ( March ), pp. 181 - 93 . Porter , R. , 1995 , “ The Role of Information in U.S. Offshore Oil and Gas Lease Auctions ,” Econometrica , Vol. 63 ( January ), pp. 1 - 27 . Romer , D. , 1996 , Advanced Macroeconomics ( New York : McGraw-Hill ). Sachs , J. , and A. Warner , 1995 , “ Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth ,” NBER Working Paper 5398 ( Cambridge, Massachusetts : National Bureau of Economic Research ). Sachs , J. , and A. Warner , 1997 , “ Sources of Slow Growth in African Economies ,” Journal of African Economies , Vol. 6 ( October ), pp. 353 - 76 . Sachs , J. , and A. Warner , 1999 , “ The Big Push, Natural Resource Booms and Growth .” Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 59 ( June ), pp. 43 - 76 . Shahnawaz , S. , and J. Nugent , 2004 , “ Is Natural Resource Wealth Compatible with Good Governance? ” Review of Middle East Economics and Finance , Vol. 2 ( December ), pp. 159 - 91 . Tanzi , V. , 1998 , “ Corruption around the World ,” IMF Staff Papers , Vol. 45 ( December ), pp. 559 - 94 . Tanzi , V. , and H. Davoodi , 1997 , “ Corruption, Public Investment, and Growth ,” IMF Working Paper 97/139 ( Washington : International Monetary Fund ). World Bank , 2004 , Doing Business in 2004: Understanding Regulation ( Washington ). World Bank , 2005 , World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development ( draft ; Washington ). I am most grateful to Mr. Paul Heytens for his insightful suggestions throughout this research. I also thank Messrs. Aart Kraay and Marshall Mills, the Bank of Botswana, and the IMF’s Office of the Executive Director for the Africa Group I Constituency for their helpful comments. The views expressed in this paper are not those of the IMF or the Bank of Botswana. For the argument on governance and growth, for example, see Tanzi and Davoodi (1997) , Tanzi (1998) , Burnside and Dollar (2000) , Easterly, Levine, and Roodman (2004) , and most recently, Glaeser and others (2004) . While Burnside and Dollar show that governance is a key in promoting growth in the context of foreign aid, Glaeser and others emphasize the risk of failing to measure institutional qualities and suggest that human capital is a more basic source of growth than political institutions. The model also indicates that there is another equilibrium at which the government can induce the opposition to be cooperative by offering higher profitsharing, a lower tax rate, and higher capital spending on new resource discovery (the “repressive government” equilibrium). The “democracy” equilibrium may exist somewhere between the cooperative solution and the civil war outcome. The areas where resource rents should be used vary from country to country. Typical are electricity and water distribution networks, primary schools, and hospitals. Income inequality is in general associated with slow economic growth. Banerjee and Duflo (2003) find that changes in inequality in any direction are associated with lower future growth rates. The World Bank (2005) claims that inequalities resulting from the failure of capital and insurance markets as well as market imperfections for human capital development may also distort allocation and undermine economic growth. In many Latin American countries, opening to trade has increased inequality in earnings, and so there must be complementary measures to provide infrastructure and safety nets for stable growth. These figures are subject to the available data in the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) database. For Botswana, the authorities’ mining export data are used. This paper defines natural resources as fuel, metal, nonferrous metals, and precious stones, according to the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) version 3 category. More specifically, natural resource exports correspond to these SITC categories: 28 metal ores/metal scrap; 32 coal/coke/briquettes; 33 petroleum and products; 34 gas natural/manufactured; 66 nonmineral manufactures, which includes precious stones like diamonds; 68 nonferrous metals, including silver, copper, and aluminum; and 97 nonmonetary ore, which includes gold. In Figure 4 , 82 countries with per capita resource exports of less than US$ 50 are ignored. Employment data come from the 2001 Population and Housing Census. This challenge has been recognized since the 1960s, and in the early 1980s the diversification efforts were accelerated through the Financial Assistance Policy. Indeed, growth accounting reveals that Botswana’s growth was mainly driven by capital accumulation rather than improvement in total factor productivity and growth in employment ( IMF, 1999 ). The recent rapid appreciation of the pula against hard currencies appears to have eroded to a certain extent the external competitiveness of nondiamond exports. However, this seems to have been caused by the short-run appreciation of the currency of neighboring South Africa, to which the Botswana currency is mainly pegged. Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi (2003) estimate the degree of governance, defined as country-specific, unobservable characteristics for each governance dimension, using over a hundred variables that measure perceptions of governance from 25 different data sources, such as those constructed Freedom House’s Freedom in the World, EIU’s Country Risk Service, and the World Bank’s World Business Environment Survey. The entire series of indices are available at http://info.worldbank.org/governance/kkz2004 . Mining activity tends to involve long-term contracts at every stage. For example, the U.S. federal government’s lease auctions for offshore oil and gas development involve five-year contracts with automatic extension, as long as there is production ( Porter, 1995 ), and the average contract length between coking refiners and aluminum producers is about 8 years ( Goldberg and Erickson, 1987 ). Natural gas is usually traded under extended contracts averaging 15 to 20 years ( Masten and Crocker, 1985 ). The contract between the government of Botswana and Debswana was renewed in September 2004. The 1996 Telecommunications Act provided the legislative foundation for BTA to have full and exclusive responsibility for licensing telecommunications and broadcasting operators, settling disputes among operators, approving tariffs, promoting and monitoring free and fair competition, allocating spectrum rights, approving terminal equipment, and protecting consumers. However, it has recently suffered a setback in regulatory independence from political pressures. A 2004 amendment of the telecommunications bill was meant to bring the BTA under the control of the Ministry of Work, Transport and Communication, which was then divided into Ministry of Communications, Science and Technology, and Ministry of Works and Transport. It requires the BTA to submit its operation plans and give the MWTC its powers to set regulations and licensing fees. One of the burdens for foreign companies starting businesses in Botswana is the restriction on employing foreign labor. Companies that hire foreign experts, particularly less skilled labor, must prove that the expertise cannot be found in the domestic market, and then localize the skills through internal job training programs afterward. The World Bank’s survey also indicates that Botswana’s administrative process for registering new businesses is very slow by regional and global standards ( World Bank, 2004 ). Farzin (1999) has an endogenous growth model with exhaustible natural resources. The estimation equation is based on the conditional convergence hypothesis, in which per capita growth is conditional on initial income and other variables, including natural resource abundance in this case. In ealier empirical work, natural resource richness is usually measured by resource exports due to data availability (e.g., Sachs and Warner, 1995 ; Papyrakis and Gerlagh, 2004 ). This treatment generates an apparent concern about endogeneity that GDP growth is regressed over exports. In fact, diamond exports contribute to about 35-40 percent of GDP in Botswana. However, this problem must be solved by employing instrumental variables (see the following section). According to the Ramsay RESET test, the hypothesis that this model has no crucial omitted variables cannot be rejected. The F statistics are estimated at 0.29 to 0.88, depending on which governance indicator is selected. For the derivation of the growth equation with an indirect resource effect, see Papyrakis and Gerlagh (2004) . In fact, the lagged values are considered valid instruments. The correlation of the residuals in the growth regressions at two periods is not crucially high. The estimated correlations are from −0.035 to 0.066, depending upon the specifications. In terms of growth rates, there is no severe outlier in the sample. Without the interaction term, neither resource abundance nor governance tends to be significant. This may reflect the fact that the relationship between resource abundance and terms of trade is self-evident in the sense that the resource measurement used here is defined in value rather than quantity terms. Higher international commodity prices are associated with greater natural resource endowments as well as higher export prices. The regional dummy cannot be tested by construction. The income group dummy cannot be included, either, because the sample has little regional variation among high-income countries. Even though these coefficients are excluded from the test restrictions, the test includes a relatively large number of linear hypotheses and tends to generate large test statistics by econometric nature. Thus, the sufficiently large critical value corresponding to the 1 percent significance level is a precaution. Nevertheless, one test employing government effectiveness as a governance variable can still reject the null hypothesis. The underlying rationale for this is R = [ER (P Q)]. ER is defined as the national currency per U.S. dollar and (P Q) is mineral exports in U.S. dollar terms. mainly reflects the existing profit-sharing arrangements and dividend policies (such as payout ratio, i.e., dividends on equity) but also includes possible residual factors unexplained by the other terms, including a measurement error due to time differences between exports and taxation, as well as changes in the quality mix of diamonds produced. Mineral revenues fell with the low international market prices in 2002 and the significant currency appreciation in 2003. In March 2004, the government of Botswana sold half its shares in Anglo American plc., a group company of De Beers, for about 760 million pula (equivalently US$ 170 million). This gain was reckoned as part of government mineral revenue and presumably used for general expenditure. However, resource-related asset sales should be discouraged unless long-term revenue is maximized. Debswana is owned in equal shares by the government of Botswana and De Beers Centenary AG, and Anglo American owns 45 percent of De Beers shares through DB Investment. From the long-term perspective, privatization and public asset sales would benefit the economy only if regulation were prudent and transparent. A full list of sample countries is shown in Table A.1 . The sample period of three decades taken in the earlier resource-and-growth literature (e.g., Sachs and Warner, 1995 ) seems to be too long to estimate the resource effects in a single equation. Any economic structure might change in a couple of decades. This paper considers five-year economic growth, a conventional duration in the standard growth literature. These two variables are nevertheless closely related to each other. A simple correlation is 0.7501 in the sample countries. Kaufmann’s indices are available for 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2002. This paper uses the 2002 figures, since it is presumed to take time for governance factors to be improved. In fact, the indices generally did not change dramatically during the sample period. The 2002 figures are instrumented by the 1996 data. In the Hausman test, the χ 2 statistics tend to be estimated at nearly zero. This can be interpreted as strong evidence that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. For several countries, the 1996 human capital variable is used because data are lacking. Same Series- Addressing the Natural Resource Curse: An Illustration From Nigeria

- Natural Resources, Volatility, and Inclusive Growth: Perspectives From the Middle East and North Africa

- The Macroeconomic Challenges of Scaling Up Aid to Africa

- A Governance Dividend for Sub-Saharan Africa?

- Natural Resource Booms in the Modern Era: Is the curse still alive?

- Ghana: Will it Be Gifted or Will it Be Cursed?

- Sustaining Growth Accelerations and Pro-Poor Growth in Africa

- A Public Financial Management Framework for Resources-Producing Countries

- Does Corruption Affect Income Inequality and Poverty?

- Do Resource Windfalls Improve the Standard of Living in Sub-Saharan African Countries?: Evidence from a Panel of Countries

Other IMF Content- I. I. Introduction

- I. I. Background

- AcronymsCountriesALB

- I. I. Introduction: Comparative AdvantageA.

Other PublishersAsian development bank. - Cambodia Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Rural Development Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map

- Country Integrated Diagnostic on Environment and Natural Resources for Nepal

Inter-American Development Bank- Global boom, local impacts: Mining revenues and subnational outcomes in Peru 2007-2011

- The Dutch Disease Phenomenon and Lessons for Guyana: Trinidad and Tobago's Experience

- Aid, Exports, and Growth: A Time-Series Perspective on the Dutch Disease Hypothesis

- Fiscal Rules and Resource Funds in Nonrenewable Resource Exporting Countries: International Experience

- Issues in State Modernization in Ecuador

- Traversing a Slippery Slope: Guyana's Oil Opportunity

- Investment Climate and Employment Growth: The Impact of Access to Finance, Corruption and Regulations across Firms

- Dealing with the Dutch Disease: Fiscal Rules and Macro-Prudential Policies

- Are You Being Served?: Political Accountability and Quality of Government

- IDB-9: Combating Fraud and Corruption

The World Bank- The relative richness of the poor?: Natural resources, human capital, and economic growth /

- A Pivotal Moment for Guyana: Realizing the Opportunities

- Combating Corruption in the Philippines: An Update.

- Botswana Development Policy Review: An Agenda for Competitiveness and Diversification.

- Remarks at International Conference on Improving Governance and Fighting Corruption, Brussels, March 14, 2007

- Natural resources and reforms

- Towards Sustainable Management of Natural and Built Capital for a Greener, Diversified, and Resilient Economy: Policy Note for Mongolia

- Remarks at the International Corruption Hunters Alliance Meeting, Washington, D.C., December 8, 2014

- Are Natural Resources Cursed?: An Investigation of the Dynamic Effects of Resource Dependence on Institutional Quality

- Anticorruption Initiatives: Reaffirming Commitment to a Development Priority

- Share on facebook Share on linkedin Share on twitter

Table of Contents- I. Introduction

- V. Policy Implications

- View raw image

- Download Powerpoint Slide

International Monetary Fund Copyright © 2010-2021. All Rights Reserved.  - [185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500  GRIS: Governance Research Indicator Country Snapshot- Tajikistan- World Bank Group

- Freedom of the press

- Infant mortality

- Gross national product

- Living conditions

- Composition of the population

- Social questions

- Education and communications

- Public finance

- Geography and oceanography

- Quality of life

- Social systems

- Communication process

Type of itemProviding institution. - Konstantinou Simitis Foundation

- Greek Aggregator SearchCulture.gr

Rights statement for the media in this item (unless otherwise specified)- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- Regime change

- 2000-2006 World Bank- Governance

- A1S5-6_WorBanGov_F1T10

- https://www.searchculture.gr/aggregator/edm/iksrep/000117-11649_21681

Providing countryCollection name. First time published on EuropeanaLast time updated from providing institution2024 Country Snapshots The 2024 Country Snapshots compiles the key statistical data used by the Committee for Development Policy (CDP) at the 2024 triennial review of the least developed country category. LDCs are defined as low-income countries suffering from structural impediments to sustainable development. To identify LDCs, the CDP uses three criteria: gross national income (GNI) per capita; human assets index (HAI) and economic and environmental vulnerability index (EVI). HAI and EVI are indices composed of fsix and eight indicators, respectively. These fourteen indicators, together with the indices for per capita GNI, HAI and EVI, are presented in two-page profiles for each of the 45 countries classified as LDCs in 2024, thus providing a snapshot of each country’s situation at the 2024 triennial review. The snapshots also illustrate the gaps in progress towards the LDC graduation thresholds for each country, while comparing individual outcomes with corresponding results for all LDCs and developing countries. Additionally, each snapshot provides a short overview on the country’s LDC status and applicable reports and resolutions related to inclusion into and graduation from the LDC category. - Office of the Director

- Global Economic Monitoring Branch

- Development Research Branch

- Development Policy Branch

- Secretariat of the Committee for Development Policy

- CDP Plenary

27th session: Tentatively 24-28 February 2025 - Least Developed Countries

- LDCs at a Glance

- International Support Measures

- Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Indicators

- Human Assets Indicators

- Inclusion into the LDC Category

- Graduation from the LDC Category

- Graduation Preparation & Smooth Transition

- LDC Resources

- Contacts and Useful Links

LDC resources- List of LDCs

- Reports and Resolutions

- Analytical documents

- Impact Assessments

- Vulnerability Profiles

- Monitoring Reports

- Country Snapshots

Committee for Development Policy- CDP Members

- CDP Resources

- News & Events

- Least Developed Countries (LDCs)

CDP Documents by Type- Reports & Resolutions

- Policy Notes

- LDC Handbook

- Background Papers

- CDP Policy Review Series

CDP Documents by Theme- Sustainable Development Goals

- Financing For Development

- Productive Capacity

- Social Issues

- Science & Technology

- Small Island Developing States

- Fraud Alert

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

|

IMAGES

COMMENTS

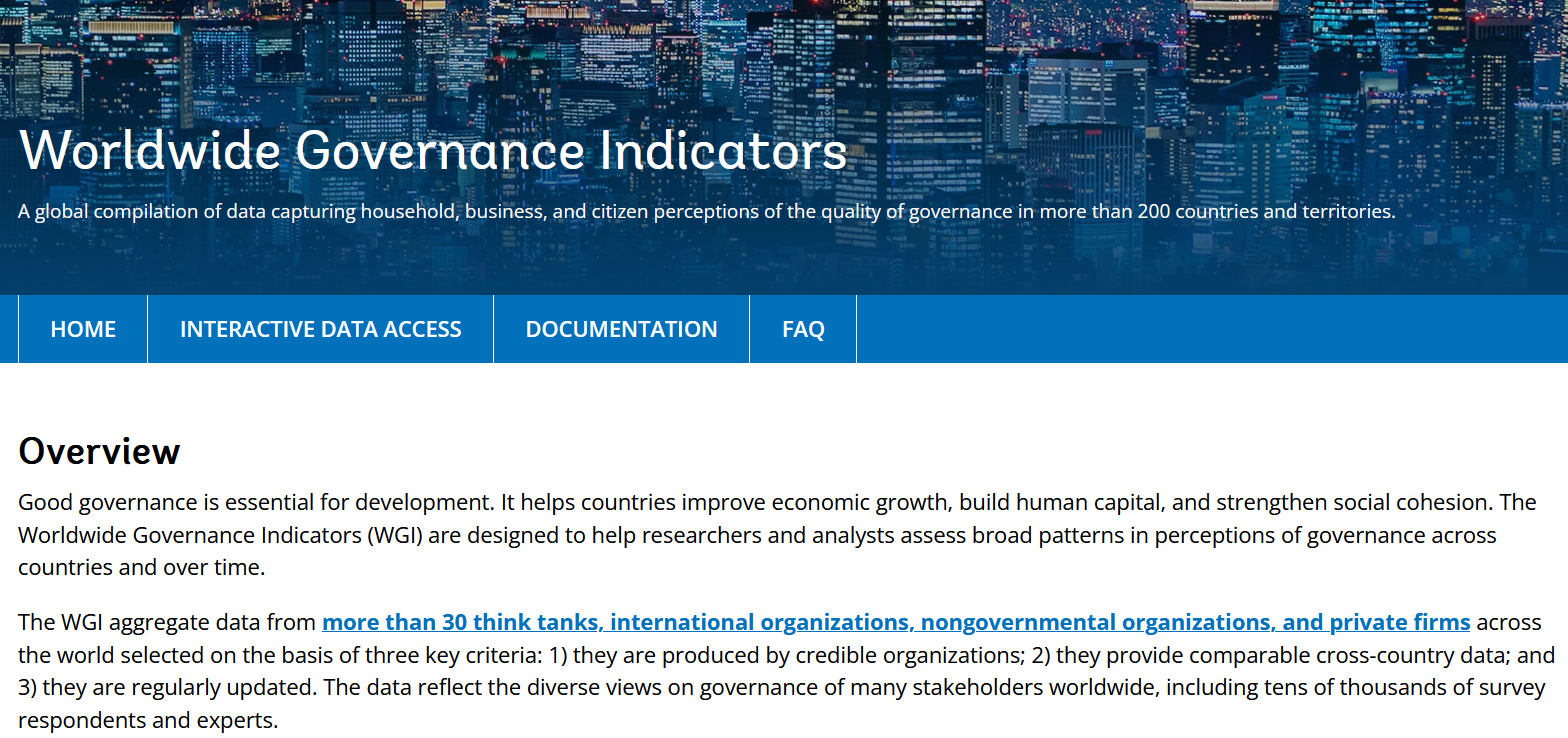

The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) are designed to help researchers and analysts assess broad patterns in perceptions of governance across countries and over time. The WGI aggregate data from more than 30 think tanks, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and private firms across the world selected on the basis of ...

The data is identified with the file name Worldwide Governance Indicators 2012-2022.xlsx. The data presented in that file consists of six dimensions of public governance as previously mentioned. The data is structured into a balanced panel data format from 2012 to 2022. It covers 180 countries members of the World Bank.

The Reproducible Research Repository is a one-stop shop for reproducibility packages associated with World Bank research. The catalogued packages provide the analytical scripts, documentation, and, where possible, the data needed to reproduce the results in the associated paper. ... The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) project reports ...

1. Click on the additional countries listed in the country selection panel. 2. To remove the country from the group double click on the country or select the country and click Remove button. 3. Click on Add to save changes to your customized group. Note: Editing the group name will create a new custom group.