Fast Fashion and Sustainability - the Case of Inditex-Zara

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham

Senior Theses International Studies

Winter 2-1-2020

Fast Fashion and Sustainability - The Case of Inditex - Zara

Tatiana Destiny Sitaro

Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/international_senior

Part of the Fashion Business Commons

Fast Fashion and Sustainability - The Case of Inditex-Zara

Tatiana Sitaro [email protected] B.A. International Studies Europe Track

Advisor: Rafael Lamas [email protected]

Table of Contents

I. Abstract 3

II. Introduction 4

III. Methods and Limitations 5

IV. Theoretical Framework 7

V. Literature Review 8

A. Fast Fashion Model 8

B. Sustainable Model 10

C. Descriptive Study 11

D. Analytical Perspective 12

VI. Case Study: Inditex-Zara 14

A. Historical Overview 14

B. Business Structure of Inditex 17

C. Zara’s Business Model 20

D. Zara and Fast Fashion 22

E. Zara’s Sustainability Measures 24

VII. Analysis 27

A. Profit 28

B. Environment 29

C. People 31

VIII. Conclusion 33

IX. Works Cited 35 3

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between Inditex’s business model of fast fashion and sustainability, specifically using Zara as a case study. The analysis focuses on the comparison of Inditex and their sustainability goals, against a fixed definition of sustainability split into three parts: profit, environment, and people. The methodology of the paper is analyzing Inditex’s 2018 Annual Report and their global sustainability goals against various scholarly articles and studies conducted of the company and sustainable fashion .

Ultimately, I synthesized prior studies and added the most recent sustainability report published by Inditex. The findings show that while Inditex-Zara can take steps towards becoming sustainable, ultimately the company will never become completely sustainable according to the incompatibility of the business structures. Moreover, much of the rhetoric around sustainability is centered around creating goals, yet quite little action and results have been made. This paper contributes to the fast fashion industry literature by emphasizing the importance of the case study, the importance of sustainable actions, and decreasing the negative impact the fashion industry creates.

Introduction

Eileen Fisher, fashion designer, said, “Becoming more mindful about clothing means looking at every fiber , every seed and every dye and seeing how to make it better. We don’t want sustainability to be our edge, we want it to be universal.” In the fashion industry, the topic of sustainability has become a buzzword over the last few years as the true cost of fast fashion has continued to be uncovered. Fast fashion refers to clothes that are trendy, affordable, and only meant to wear a handful of times before being discarded. However, in contrast, the term sustainability, in relation to the fashion industry, has become almost an empty concept and growly difficult to define. For the purpose of this thesis, the following three main areas of sustainability will be focused on: profit, environment, and people.

This paper explores the relationship between fast fashion - clothes that are “here today, gone tomorrow,” and sustainability. The question this paper attempts to answer is, can a fast fashion company, Inditex-Zara, become sustainable? More specifically, to prove my point, I use the case study of Inditex-Zara, a Spanish based apparel company to compare against the definition listed above of sustainability. Ultimately, I argue that because the business structure of

Inditex is incompatible with a sustainable business model, it will not succeed in becoming sustainable. Furthermore, I make a case for transitioning away from the development of ambitious corporate sustainability goals to taking action.

In the following sections, I will examine the similarities and primarily the differences between a fast fashion business model and a sustainable business model. I begin the thesis with an indepth look at existing literature related to fast fashion, Inditex-Zara, and sustainability in the fashion industry. I then transition into a historical overview of the case study and present current 5 statistics and figures of the company, including annual profits, number of stores, the logistics of the company, and their sustainability efforts. Finally, the analysis section puts Inditex-Zara’s sustainability efforts in conversation with the definition of sustainability in order to see if these two different business models are compatible. I argue that due to the very nature of

Inditex-Zara’s business model and the difference between it and the sustainable model, they are in fact not sustainable. The structure of fast fashion companies allows for sustainable action and progress, but not complete sustainability.

Methods and Limitations

The information collected and used in this thesis was found primarily through Fordham’s online library database. In the beginning, I looked for articles that tracked and analyzed the history and growth of Inditex-Zara. Generally, these articles were easy to find; however, locating articles that placed Inditex-Zara’s business model in conversation with sustainability proved more difficult. Due to the nature of sustainability, both it being a relatively new topic and the flexibility of the definition of sustainability, the articles that I was able to find all approached the topic differently. Many articles focused on the logistics of sustainability, specifically related to supply chain and production. While these are topics I wanted to discuss in my thesis, I was also interested in the social aspect of sustainability. Searches for lawsuits against Inditex and worker’s rights proved more helpful for gathering this type of information.

Many of the sources used are from the early to mid-2000s, and my hope for this thesis was that it would bring a fresh and current perspective to the issue of fast fashion and sustainability. However, it proved difficult to find material that analyzed these topics together 6 and were published recently. As a way to combat this, much of my analysis relies on Inditex’s

2018 Annual Report and Inditex’s global sustainability goals released in July of this year. I used my other sources, especially the ones related to sustainability, to compare and contrast Inditex’s business structure, annual report, and sustainability goals, against a fixed definition of sustainability. Through this method, I was able to explore my research question and make my case that fast fashion and sustainability are not completely compatible.

Besides the limitation related to sustainability sources, another major limitation I faced while conducting my research was the perspective of my sources. The story told of Inditex-Zara in my sources, the story of rapid growth and immense profit, is much the story that I imagine

Amancio Ortega would tell himself --The story of how one man with humble origins transformed his small retail shop located in Northern Spain to one of the largest clothing companies in the world through hard work and innovative thinking. Yet, as I was conducting my research I could not help to wonder, “Is this the actual story?” Would the workers and residents who grew up in

La Coruña tell the same version? As an undergraduate student conducting research using scholarly sources, this information was not available to me. In fact, this information might only be available to a researcher who has the time and resources to be on the ground in Northern

Spain conducting interviews and uncovering not the history, but the memory of Inditex-Zara.

Yet, that being said, with the resources available to me, my thesis argues that even if a

Inditex-Zara, a fast fashion company, takes steps towards sustainability, it is a company rooted in exploitation that ultimately will never be completely sustainable.

Theoretical Framework

Fast fashion “departs from the traditional norms of designer-led fashion seasons, using instead designers who adapt their creations to customer demands on an ongoing basis” (Crofton

41). In order to rapidly respond to the demands of customers at affordable prices, Inditex uses over one hundred subsidiaries, vertically integrated design, “just- time production,” distribution, and speedy communication between customers and designers. In order to achieve this fast fashion model, Inditex strayed from “the fashion industry’s traditional model of seasonal lines of clothing designed by star designers, manufactured by subcontractors months earlier, and marketed with heavy advertising” (42).

According to Shen and his colleagues, “sustainable fashion is all about paying attention to a few key aspects, like sustainable manufacturing , ecomaterial preparation, green distribution/retailing, but also ethical consumers” (qtd. in Popescu 335). Sustainable manufacturing “enforces human rights and environment protection.” (335). Eco-material production focuses on the use of organic materials that are made with less water consumption and chemicals. Eco-material production can also include the use of recycled materials. Green distribution is more complicated because of the complexity and speed of season cycles; however, the focus here is on carbon emissions. Green retailing encourages “ethical consumer practices” since as of late, consumers are more interested and aware of sustainability practices and brands in the fashion industry, which ties into ethical consumers who use or prefer sustainable fashion lines (335). Supply chain is defined as a “protypical example of a buyer-driven global chain, in which profits derived from unique combinations of high-value research, design, sales, marketing , 8 and financial services that allow retailers, branded marketers, and branded manufacturers to act as strategic brokers in linking overseas factories with markets” (Ghemawat et al. 1).

Literature Review

The study of Inditex and their business model has been approached from many different perspectives. However, there seems to be four major approaches when studying fashion companies: the fast fashion model, the sustainable model, the descriptive study, and the analytical perspective. This thesis will apply both the fast fashion model and the sustainable model to analyze the case study of Inditex, and explore if a fast fashion company can evolve into a sustainable fashion company. Through my search for sources and research on the topic of sustainability in relationship to Inditex, much of the information available seems one-sided. The story of Inditex, its history, its revolution of the fast fashion industry, and its efforts towards sustainability are all told from the perspective of the “winners”, as if Amancio Ortega were telling it himself. The research and information given on sustainability efforts comes from

Inditex themselves, and more specifically from the people in power. My thesis will try to fill this gap, and while I may not have the current means to find the truth, I can question the narrative and information that exists.

The Fast Fashion Model In 1904, Georg Simmel in his book Fashion wrote, “Fashion is the imitation of a given example and satisfies the demand for social adaptation… The more an article becomes subject to rapid changes of fashion, the greater the demand for cheap products of its kind” (qtd. in 9

Ghemawat et al). This would be seventy-one years before Zara opened its first store in Galicia ,

Spain, in 1975. The fast fashion model relies on using designers who can adapt their creations and designs to the customer’s demands on a regular basis (Crofton 41). In the academia surrounding fast fashion, Amancio Ortega, creator of Inditex (Industria de Diseño Textil), is often referred to as the creator and pioneer of this business model. Inditex themselves describes their way of doing business as “creativity and quality design together with a rapid response to market demands” with the “democratization of fashion” (Inditex Corporate Website). In other words, fashion products are now available to the general public for mass consumption where before, fashion was only for the elite consumers (Avendaño et al. 220).

Rather, fast fashion companies use vertical integration design, rapid production and distribution, and rely on direct feedback from the consumers (Crofton 42). Vertical integration can be defined as when a company manages production stages that are traditionally handled and operated by separate companies. Inditex aims to please the customer demand by cutting the time in which new clothes become available in its stores. The fast fashion model is based in rapid change, flexibility, and responsiveness, as well as a supply chain that is agile (qtd. in Popescu

334). In return, due to the lower price points, the fashion products produced by fast fashion companies can be purchased by the majority of society, broadening the target audience

(Avendaño et al. 220). As mentioned before, Inditex depends upon their customers and their opinions. The company pays close attention to their customers’ wants and needs, and they are answered with market segmentation and product tailoring. Furthermore, “specific sets of behaviour across the entire company are designed to answer customers’ needs in an agile and permanent manner” (Avendaño et al. 223). 10

The Sustainable Model

In contrast to the fast fashion model, sustainable fashion companies utilize “sustainable manufacturing, eco-material production, green distribution, green retailing and ethical consumer practices” (Popescu 333). The sustainable movement was created as a backlash to the problems that arose from fast fashion companies’ rapid and flexible supply chain. Yet, while some companies have chosen to move from the traditional or fast fashion model to the sustainable model for environmental and/or economic reasons, others have switched purely out of their own interests (Marcuello 393). Some issues include pollution, exploitation of workers, carbon emission levels, and resources management. As a result of these issues, “the environmental and social footprints became major concerns at the level of the fashion industry, besides the economic footprint” (334). Recently, companies with a sustainable supply chain report themselves to three sustainability pillars: economic, social, and environmental measures.

Another concern that the sustainable model looks at is ethicism; more specifically, the social responsibility that fashion companies have (Brodish et al. 355). The sustainable model, like the fast fashion model, in an ever-growing business, may outsource production to developing countries due to the lower environmental regulations and cheaper production costs; however, the sustainable model strives to ensure uniform environmental conditions and resources in order to avoid sustainability issues. For example, a company who focuses on sustainable manufacturing

“enforces human rights and environment protection, given the fact that more and more consumers envisage the effect their purchase has on promoting modern human slavery conditions in apparel manufacturing” (qtd. in Popescu 335).

Descriptive Study

Justo de Jorge Moreno, a professor at the University of Alcalá with over 74 publications specialized in business economics and development, states that 50% of published papers on the topic of Inditex and their internationalization are grouped in the descriptive sector (Carrasco

Rojas et al. 398). Most research in this area accords with this method, while some fell under the analytical perspective or were a hybrid of the two frameworks. Additionally, two other sources fall under the category of descriptive study: Ghemawat et al. and Alonso Álvarez. Ghemawat et al. choose to look at the structure of Zara from the producers to the customers. They also profile

The Gap, Hennes & Mauritz, and Benetton, which are three of Inditex’s leading competitors before focusing on Zara’s business system and international expansion (Ghemawat et al. 1).

Likewise, Alonso Álvarez divides his paper into four sections. The first section provides background on Inditex’s place in the broader Spanish clothing business sector. Secondly, he provides the history of the group between 1963 and 1999, and compares financial and commercial ratios. Finally, the author looks at the factors that influenced the company’s rapid growth and success. On a similar note, Crofton, a professor at High Point University, lays out the fast fashion model and presents its historical development and prospects. She then takes this framework and applies to it the growth of Inditex from its beginning to 2006 and predicts the prospects for the company and the fast fashion industry overall.

It is important to note that much of the literature that falls under the descriptive study category follows a similar structure of those mentioned above. In the realm of sustainability and fashion, the papers in this category slightly differ structurally. PhD lecturer at West University of

Timisoara, Romania , Alexandra-Codruta Popescu, details the actions that Inditex and H&M have 12 taken in order to make sure that sustainability exists within their supply chains, businesses, and brands. In order to achieve this, the author compares the two companies to a sustainable business model, analyzing factors such as manufacturing, water consumption, green distribution and retailing, and ethical consumers (Popescu 339-347). In the same category, Marcuello et al. detail the role NGOs play in corporate social responsibility by looking at the case of Inditex vs. Clean

Clothes. In other words, the authors argue that “both corporations and non-government organisations must account for the social impact of their activities” by looking at the harassment claims filed by the Spanish chapter of the Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC) against Inditex (393).

Analytical Perspective

Similarly, if fifty percent of published materials fall into the descriptive study group, then the rest falls into the analytical perspective category. More specifically, “the online market Zara and competition, brand differentiation, corporate identity, the influence of information technology and communication and the biography of the founder of Zara” (Carrasco Rojas et al.

398). His own study, although a hybrid of descriptive and analytical, relies heavily on the analytical perspective. The work is divided into two parts. In the first part, Carrasco Rojas and

Moreno analyze Inditex for its competitive environment using a cluster analysis to “segment the market and carry out a comparative analysis of Inditex with its direct competitors” (406). In the second part, the authors focus on analyzing the company during a fixed time period from 1990 to

2013, in order to study the company’s efficiency.

Avendaño, et al. (2003), established professors at the University of Vigo, Oureuse, Spain, take a slightly different approach in their analysis on market orientation and Inditex-Zara’s 13 performance. The paper, which presents itself as the first of its kind in the context of research, examines Zara as a “paradigmatic example of the development of market orientation in a company, as a basis for the company’s performance and competitive advantages” (220). The authors used company specific literature, including other cases studies on the company, interviews, internet articles, and reports conducted by financial analysts. Moreover, the authors sent out specific questionnaires “to members of different departments of the store chains which compose the group, and in-depth interviews were carried out with Mr. Fernando Aguiar, a company executive and university lecturer” (Avendaño et al. 220).

Orcao and Pérez (2014), both from the University of Zaragoza, also fall under the analytical perspective although they choose to look at Inditex’s global production (Orcao et al.).

The authors focus on how transport and logistics play into the production network and argue that transport and logistics is one of the main factors that gives the company its comparative advantage. The paper confronts the dilemmas fashion retailers have to face when organizing supply chain and geographical integration. More specifically, they describe “the network of shops and manufacturing” and base their analysis on “recent and previously unpublished data on the brand’s logistics hub in Zaragoza” which “sheds light on the modus operandi of the group and confirms the crucial importance of logistics in all facets of the production model” (Orcao et al. 113). In order to do this, Orcao et al. present the principles of the logistical model and explain the procedures taken in order to make the geographical integration of Zara function properly.

Although the paper lists logistics and transport as a key factor in the expansion of Inditex, the authors believe their paper can be broadly applied to the fast fashion sector. The general application of this theory is important, as this thesis will follow a similar structure by attempting 14 to answer the question, “Can a fast fashion company become sustainable?” using Inditex-Zara as a case study.

Case Study: Inditex-Zara

The case study of Inditex, specifically the company Zara, will be used to show the business model of fast fashion model in contrast to sustainability, using the second largest fashion company in the world as an example. The rapid growth of Inditex and its unique business model, including the coinage of vertical integration, proves an easy case study to apply to the question of whether fast fashion companies can become sustainable, as it can be widely applied to other fashion companies in the world.

Historical Overview

Inditex, founded by Amancio Ortega, is one of the most successful companies in Spain and in the world. Today, the company houses the following brands: Zara, Pull & Bear, Massimo

Dutti, Bershka , Stradivarius, and Oysho (Marcuello et al. 396). Born in 1936, Ortega’s first job was in 1949 as an errand boy for a shirt maker in La Coruña, Spain. In 1963, Ortega created his first business: Confecciones Goa. Confecciones Goa, producer of housecoats, was Ortega’s first step in his mission to improve the manufacturing and retail interface. Out of this goal, Zara was born in 1975 on a main street in La Coruña known for its high-end retail stores. From its inception, Zara marketed itself as “a store selling ‘medium quality fashion clothing at affordable prices’” (Ghemawat et al. 7). By the end of the 70’s, Zara had expanded to half a dozen storefronts in Galicia, Spain. 15

Galicia, the third poorest of Spain’s seventeen autonomous regions, had poor communication with the rest of the country and during the time period of Ortega’s youth, was still heavily dependent on the agriculture and fishing sectors. In the apparel sector, however,

Galicia had a strong history dating back to the Renaissance when Galicians were often tailors to the aristocracy, and Galicia was littered with thousands of small apparel workshops (Ghemawat et al. 6). According to Ghemawat, “what Galicia lacked were a strong base upstream in textiles , sophisticated local demand, technical institutes and universities to facilitate specialized initiatives and training, and an industry association to underpin these or other potentially cooperative activities” (6). Yet, according to José María Castellano, the former CEO, “Galicia is the corner of Europe from the perspective of transport costs, which are very important to us given our business model” (Ghemawat et al. 6).

Amancio Ortega, said to be a gadgeteer and innovator by Ghemawat et al., purchased his first computer in 1976, a year after the grand opening of the first Zara. At this time in Inditex’s history, Ortega was responsible for only four factories and two stores. He used his interest and curiosity in technology to harvest store data on customers’ wants and desires. Zara reached

Madrid, the capital of Spain, in 1985, and by the end of the 80s, had stores in all Spanish cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Zara then shifted to opening new stores internationally as well as adding other retail brands, creating the corporation Inditex, by the early 1990s

(Ghemawat et al. 7). Spanish consumers wanted low prices but were not considered as fashion conscious or as stylish as Italian buyers, for example. However, that being said, Spain had advanced quickly in the world of fashion after the death of dictator General Francisco Franco in

1975. Following this, the country had opened up to the rest of the world and engaged more in 16 international trade and the global economy. Spain had a strong and productive apparel manufacturing sector by European standards and as a result, Ortega was able to rapidly and relatively easily expand his company (7).

Zara’s market expansion was quite extensive. According to the same source:

Zara’s international expansion began with the opening of a store in Oporto in northern Portugal . In 1989, it opened its first store in New York and in 1990, its first store in Paris. Between 1992 and 1997, it entered about one country per year… so that by the end of this period, there were Zara stores in seven European countries, the United States , and Israel . Since then, countries had been added more rapidly: 16 countries… in 1998-1999, and eight countries…in 2000-2001. Plans for 2002 included entry into Italy , Switzerland , and Finland. Rapid expansion gave Zara a much broader footprint than larger apparel chains: by way of comparison, H&M added eight countries to its store network between the mid-1980s and 2001, and The Gap added five (Ghemawat et al. 15).

By the end of 2001, out of all the chains, Zara was the largest and the most internationalized.

Zara had 2,982 stores in 32 countries other than Spain, accounting for 55% of the international market of Inditex. Zara also had earned approximately 1,506 million euros in sales, adding up to roughly 86% of Inditex’s international trade (15). According to Crofton et al. (2007), Zara’s astounding growth has led to an increase of other fashion companies attempting to replicate and recreate Inditex’s business model. In under fifty years, Zara transformed from a local retail store to the second largest clothing company with approximately 2,700 stores located in sixty countries throughout the world. Amancio Ortega’s once independently owned and operated business was now a public company responsible for over 8 billion dollars in annual sales and worth 24 billion (41).

Business Structure of Inditex

The six retailing chains that make up Inditex are structured as “separate business units within an overall structure that also included six business support areas (raw materials, manufacturing plants, logistics, real estate, expansion, and international) and nine corporate departments or areas of responsibility” (Ghemawat et al. 8). In other words, each of the chains

“operated independently and chains were responsible for their own strategy, product, design, sourcing and manufacturing, distribution, image, personnel, and financial results” (8). The

Group’s corporate “management set the strategic vision of the group, coordinated the activities of the concepts, and provided them with administrative and various other services” (8).

Inditex describes its business model as “creativity and quality design together with a rapid response to market demands” and the “democratization of fashion” (qtd. in Crofton et al.

42). In order to execute rapid responses to their customers’ demands and at affordable prices,

Inditex shifted away from the traditional model of seasonal lines and couture designers, focusing instead on vertically integrating just-in-time production, distribution, and sales. Many leading fashion companies manage design and sales but outsource manufacturing, often to low-wage subcontractors located in East Asia. In the search for cheap labor, companies “use networks of subcontractors that may buy, dye, embroider, and sew fabric each in a different country” (42).

However, this model of design-to-retail process can take up to eight months. In order to speed the production cycle up, Inditex coined the vertical integration model, where they produce a large percentage of their products in their own factories. To reiterate, typically, Inditex carries out the more “capital-intensive and value-added-intensive stages of production, such as raw materials, designing, cutting, dyeing , quality control, ironing, packaging, labeling, distribution, 18 and logistics and outsources more labor-intensive and less value-added-intensive stages of production, such as sewing” (43).

In order to ensure that their manufactured products arrive to stores as quickly as possible,

Inditex constructed an elaborate network of suppliers, manufacturers, and workshops. According to Crofton et al. once the raw materials are received from various countries including China and

Morocco, the fabrics are sent to workshops for finishing touches. These workshops, estimated to be numbered around 400, are located primarily in Galicia and Northern Portugal. It is in these workshops that the clothes are dyed, cut, and sown. Once the garments are assembled and completed, they are sent by truck to the stores (43). According to the same source, stores in

Europe can receive shipments from the workshops in under forty-eight hours (43). On the other side of the business, top corporate managers whose “ability to control performance down to the local store level was based on standardized reporting systems that focused on (like-for-like) sales growth, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT margin), and return on capital employed”

(Ghemawat et al. 8). Current CEO, Pablo Isla, describes the structure of Inditex as “very flat” moving away from formal meetings and formal management committees. He describes the workers as “empowered” people who make decisions themselves and put emphasis on teamwork

(McGinn 73).

Furthermore, the use of technology in the business has a huge impact on the structure as

“we [Inditex] use technology and algorithms that propose what garments to stock, but the store manager can change the order, because we want the store manager to feel like the owner of the product” (Mcginn 73). Inditex places a strong emphasis on their ability to speedily respond to customer demands. This can be seen as slowing the decline of manufacturing employment in 19 developed countries. For example, according to John Thorbeck of SupplyChainge. “Zara has proven that speed and flexibility matter more than pure price” (Crofton et al. 43) On the flip side,

John Quelch, professor of marketing at Harvard Business School, says “Nike, Levi’s and others face recriminations for exploiting low-cost labor in emerging economies. Zara is less subject to criticism” (43). Inditex’s response to this is that this approach of vertical integration and reduction of the design-to-retail cycle is simply a business decision, “not a moral stance. To reduce lead time, we need to produce closer, not cheaper” (43).

Inditex’s international expansion is often described as an ‘oil stain’. First, the branch opens a flagship store in a major city and after learning about and testing the local market, introduces more stores in the country (Ghemawat et al. 15). The company looked for new country markets that were similar to the Spanish market and were relatively easy to enter.

According to former executive José María Castellano,

For us it is cheaper to deliver to 67 shops than to one shop. Another reason, from the point of view of the awareness of the customers of Inditex or of Zara, is that it is not the same if we have one shop in Paris compared to having 30 shops in Paris. And the third reason is that when we open a country, we do not have advertising or local warehouse costs, but we do have headquarters costs (Ghemawat et al. 16).

Inditex’s sales growth has grown increasingly and by multiple measures. Sales grew from $0.086 billion in 1985 to $0.8 billion in 1990, $1.2 billion in 1995, $2.4 billion in 2000, and $8.2 billion in 2005. Inditex employees jumped from 1,100 in 1985 to 5,018 in 1995, 24,004 in 2000, and

58.190 in 2005. About one-half of the employees that make up Inditex are located in Spain.

Other employees, including sewing cooperatives and workshops compose an additional 11,000 jobs (Crofton et al. 46). Inditex’s rapid growth raises many questions and concerns for the future and their business model. 20

Zara’s Business Model Zara is the largest and most international brand of Inditex. By the end of 2001, Zara had over 507 stores worldwide with “488,400 square meters of selling area (74% of the total) and employing 1,050 million of the company’s capital (72% of the total), of which the store network accounted for about 80% (Ghemawat et al. 8). In a 2017 interview with Pablo Isla, CEO of

Inditex, Isla describes the business model of the company as:

We have our own very specific business model. It’s based on the ability to react flexibly within a fashion season. We use what we call proximity sourcing, producing most of our goods in Spain, Portugal, and Morocco ; this allows us to make deliveries at the very last minute. We pay a lot of attention to the design of every single product. It is not just a question of being fast. It is the concept of trying to know what our customers want and then having a very integrated supply chain among manufacturing, logistics, and design to get it to them (Mcginn 73).

The company divides their product lines into “women’s, men’s, and children’s, with further segmentation of the women’s line, considered the strongest, into three sets of offerings that varied in terms of their prices, fashion content, and age targets” (Ghemawat et al. 13). The price points of the products, determined by the company, are supposed to be lower than competitors due to “direct efficiencies associated with a shortened, vertically integrated supply chain but also because of significant reductions in advertising and markdown requirements” (13). On average,

Zara spent only 0.3 percent of its annual budget on media advertising and the company avoided creating a strong image for the brand in fear of strictly defining the “Zara Woman.” Moreover, the company did not host ready-to-wear fashion shows; rather, all new product and stock was first shown in store (13).

Around 1990, Zara had completed its introduction into the Spanish market and began to make investments in manufacturing logistics and IT. In order to fulfill the company’s goal of 21

“just-in-time manufacturing”, they built a 130,000 square meter warehouse close to the corporate headquarters outside of La Coruña complemented by an advanced telecommunications system.

This system facilitated communication between Inditex’s headquarters, supply, production, and sales locations. Zara’s business system was unique because they manufactured the most avant-garde pieces, or newly in style pieces, internally since they tended to be the riskiest in terms of sales. The designers kept track of customer preferences and placed orders with the suppliers (Ghemawat et al. 9). Vertical integration helped to reduce the ‘bullwhip effect’ which can be defined as “the tendency for fluctuations in final demand to get amplified as they were transmitted back up the supply chain” (9).

As a result of Zara’s vertical integration, they were able to create a new design and have the finished product in stores within four to five weeks in the case of entirely new designs or two weeks for modifications made on existing product. In comparison, a traditional industry model could include production cycles that take up to six months for design and concept and up to three months to complete manufacturing. Zara’s very short cycle time allowed for non-stop manufacturing of new products allowing the brand to commit to the majority of their product line much later in the season than competitors. As a result, Zara committed to “35% of product design and purchases of raw material, 40%-50% of the purchases of finished products from external suppliers, and 85% of the in-house production after the season had started, compared with only 0%-20% in the case of traditional retailers” (Ghemawat et al. 9).

Zara and Fast Fashion

If one were to ask Pablo Isla about the company’s relationship to fast fashion, he’d respond “I don’t like labels”; however, the fact of the matter is, Zara is indeed a fast fashion company (Mcginn 73). Zara’s product offering can be defined as “emphasized broad, rapidly changing product lines, relatively high fashion content, and reasonable but not excessive physical quality: ‘clothes to be worn 10 times’” (Ghemawat et al.13). Zara creates two basic collections each year in the form of fall/winter and spring/summer seasons. The designers, over three hundred of them, constantly search for information about customers’ tastes and preferences.

They attend all the major fashion shows across the globe including Paris, New York, and Milan and study what people wear in their day-to-day life and routine. These efforts helps the designers better understand the clients, and therefore, better predict trends. However, the key source of information for Zara’s designers comes from the stores themselves and their base od dedicated customers who shop there. Twice a week the stores send the headquarters daily sales totals and detailed information on all of the products purchased within that time frame, itemized by color and size (Crofton et al. 42). This allows the designers, store managers, and customers to be linked, viewing customers as the company’s “accomplices” according to José Toledo, an executive at Zara (42).

Zara sources their fabric from suppliers with the assistance of their buying offices located in Barcelona and Hong Kong. Additional buying support is offered from sourcing personnel at the La Coruña headquarters as well. Previously, Zara had sourced their fabrics only from Europe, but the opening of three companies in Hong Kong allowed them to source and trend-spot from

Asia, expanding the production process significantly. In fact, approximately one-half of the 23 fabric purchased by Zara was gray, or undyed, in order to streamline in-season updates to the product line and maximize flexibility. In 2006, the vast majority of fabric was handled and processed through Comditel, a subsidiary of Inditex, that worked with more than 200 fabric and other raw material suppliers (Ghemawat et al. 11). Comditel “managed the dyeing, patterning, and finishing of gray fabric for all of Inditex’s chains, not just Zara, and supplied finished fabric to external as well as in house manufacturers” (11). This process meant that the company, on average, only took one week to finish fabric.

Zara’s power and attractiveness to consumers is based on the constant newness of its clothing, which in turn creates a sense of scarcity and an exclusive ambience around the company’s offering. The company’s freshness was rooted in “rapid product turnover, with new designs arriving in each twice-weekly shipment” (Ghemawat et al. 13). According to the same source, approximately three-quarters of the merchandise on display was changed every three to four weeks, corresponding to the average time between visits “given estimates that the average

Zara shoppers visited the chain 17 times a year, compared with the average figure of three to four times a year for competing chains and customers” (Ghemawat et al. 13). This amount of rapid turnover created a sense of “buy now” out of fear that the product would not be there the next time a customer visited a store. According to Luis Blanc, Inditex’s international directors:

We invest in prime locations. We place great care in the presentation of our storefronts. That is how we project our image. We want our clients to enter a beautiful store, where they are offered the latest fashions . But most important, we want our customers to understand that if they like something, they must buy it now, because it won’t be in the shops the following week. It is all about creating a climate of scarcity and opportunity (Ghemawat et al. 13).

In addition, this sense of “buy now or regret later” was reinforced by small, frequent shipments and a company mandated limit of how long items could be displayed and sold in the stores.

Moreover, the company requested the in store displays to appear barely stocked, as well as limiting the amount of each product sent in the shipments, decreasing the availability of stocked products (13). In a piece written by Otto Pohl, he interviews Maria Naranjo, a Spanish teenager and Zara aficionado, who spends her time tracking Zara’s delivery schedule. As an avid customer, Maria knows the truck arrives twice a week and she states, “They always have something new…I’ve been shopping here for as long as I can remember. My mom dressed me in

Zara when I was a kid” (Pohl). This type of customer devotion is what drives Zara’s commitment to fast fashion.

Zara’s Sustainability Measures

Sustainability can be defined in many ways. For the purpose of this thesis, I have used the definition used by Stephanie Brodish et al., taken from the Brundtland Commission ’s definition.

According to this source, sustainable development is “development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (356). One of the more common approaches to defining and evaluating sustainability is through three pillars: people, planet and profit (356). In May of 2001, Inditex began selling shares on the Spanish stock exchange. To the company, this was a huge milestone that called for celebration since becoming a public company came with a new set of standards and regulations.

One of the main surprises for Inditex was the purchase of shares by the network CCC. The Clean

Clothes Campaign (CCC) was created in the 1990s as a response to the exploitation of textile 25 workers. Only later on, after the CCC’s purchase of shares did Inditex take steps towards integrating a corporate social responsibility policy. Inditex’s management “adopted the so-called

‘triple bottom-line’ of financial, social, and environmental efficiency’” (Marcuello 396).

After their purchase of stocks, Setem, the Spanish Chapter of the Clean Clothes

Campaign, filed a harassment claim against the company. Setem, an NGO, serves as a poster child for displaying the interaction between NGOs and companies and how NGOs can have the power to influence multi-million-dollar corporations. In other words, “both corporations and

NGOs must evaluate and be accountable for the social impact of their activities” (Marcuello

394). As the topic of sustainability continues to gain traction, there is a growing want for

“social-accountability tools” in order to evaluate the impact corporations, like Inditex, have on the social system (394).

When approached with the topic of how sustainability affects his leadership at Inditex in

2009, CEO, Pablo Isla, replied:

Every decision we make, we consider sustainability-not just me personally, but also the board and all the employees. Sustainability includes the quality of our products, what they’re made from, working conditions for the people making them, and the ability to recycle them (Mcginn 73).

This message of Isla’s commitment to sustainability was reinforced during his speech given in

July 2019, at the Annual General Meeting. During this event, Isla listed Inditex’s ambitious global sustainability goals for the upcoming years. According to the plan, by 2025, 100 percent of cotton , linen, and polyester used by the company with either be more sustainable, organic, or recycled. These three fabrics currently account for 90 percent of all raw materials used by

Inditex’s brands. By 2020, Inditex plans to fully eliminate the usage of plastic bags, something that they claim has already been achieved by Zara, Zara Home , Massimo Dutti , and Uterque. 26

Furthermore, according to the speech, in 2018, only 18 percent of bags used by all Inditex brands were made from plastic. Moreover, the company plans to eliminate all single-use plastic, in general, by 2023. Currently, the company recycles or reuses 88 percent of waste accumulated as a result of single-use plastics. Isla stated that they will continue to introduce collection and recycling systems for all of the materials used in package distribution and garment packaging including cardboard boxes, recycled plastic, alarms, and hangers for reuse within the supply chain or to be sent to the recycling program Green to Pack.

Continuing with Isla’s sustainability goals, during his Annual General Meeting Speech, he stated that the number of garments featuring the Join Life environmental excellence label will make up over 25 percent of all garments by 2020. He also noted that the volume of clothing featuring the Join Life label increased by 85 percent in 2018, amounting to approximately 136 million garments. Furthermore, in 2020, Isla promised that all of Inditex’s stores will have installed containers for collecting used clothing to either be donated for charitable purposes or recycled to the ‘Clothing Collection’ program. The Clothing Collection program works in collaboration with multiple non-profit organizations and has increased its reach to twenty-four markets. According to Inditex’s website, 1,382 containers are currently placed throughout

Inditex’s network of stores and are complemented by 2,000 street containers placed throughout

Spain in collaboration with Caritas, an at-home pick up service which operates nationwide in

Spain. Moreover, over 34,000 tons of garments, footwear, and accessories have been collected through the containers placed in Inditex’s stores, offices, and logistics platforms. The most ambitious program laid out by Isla is the completion of an entire eco-efficient store platform to be completed by 2020. In other words, 80 percent of the energy used by Inditex, whether in the 27 stores, logistic centers, or corporate offices, will be renewable. He stated that Zara will achieve this goal in 2019 and the rest of the Group's brands will follow suit (“Pablo Isla sets out Inditex’s global sustainability commitments”).

To reiterate, sustainability can be defined through three main pillars: people, planet, and profit. There are multiple misconceptions about sustainability and how it interacts with businesses and corporations. One misconception according to Brodish et al., is that capitalism is to blame for the push for sustainability since “the principles of sustainability imply that businesses should not make profits or make too much profit” (356). The actuality is that sustainability encourages the opposite. While sustainability seeks to hold companies accountable for their social and environmental impacts, “social and environmental efforts are not replacements for the customary measures of revenue and profit, but instead they enhance firm assessment by reducing the negative impact of a firm” (qtd. in Brodish et al. 356). Moreover, the

European Union states that in order to “fully meet their corporate social responsibility, enterprises should have in place a process to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights, and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy…” (qtd. in

Garcia-Torres et al. 2). Inditex is changing the way the fashion industry works by forcing other companies to adopt elements of the fast fashion model, even if traditionally, the companies followed a different model. According to Ken Watson of Industry Forum in 2007, a specialist in the fashion supply chain in the UK, Inditex “certainly impacts the way consumers react to fashion by expecting new fashion quicker. Inditex accounts for about 10 percent of the Spanish apparel market…” (Crofton et al. 49). 28

According to Crofton et al., the success of Inditex is most remarkable for two reasons.

First, the fact that Inditex started in Galicia, Spain, “a region without a fashion tradition in a country whose textile regions, Catalonia and Valencia, benefitted from trade protection until the

1970s” (45). The second reason is that, “this success continues despite the rise of producers from emerging economies, such as China, and ongoing steps liberalizing international trade in Spain”

(45). In fact, in 2018, the sales footprint of Inditex increased by 5 percent followed by the company’s commitment to opening larger stores equipped with improved technology, allowing for online integration and eco-efficient operations. But, just how can a company claim to be promoting sustainability, when in the last six years alone they have open 3,364 new stores, completed renovations in 2,374 stores, expanded 1,019 store fronts, and absorbed over 1,401 older and smaller-sized spaces (“Pablo Isla sets out Inditex’s global sustainability commitments”)? Pablo Isla’s current response to Inditex’s rapid expansion is, “Thanks to this effort, we are now offering our customers an integrated and unique experience in which they can swap the store for the online platform, and vice versa, at any stage in the process to best suit their needs” (“Pablo Isla sets out Inditex’s global sustainability commitments”). In relation to sustainability and profit used for good, this global expansion does not work.

Furthermore, according to Ghemawat et al., who published their article in 2006,

Spaniards were “exceptional in buying apparel only seven times a year, compared with a

European average of nine times a year, and higher-than-average levels for the Italians and

French, among others” (Ghemawat et al. 4). Yet, currently, Inditex’s strongest presence is in

Spain with Spain accounting for 16.2 percent of Zara’s net sales, showing the increase of 29

Spanish shoppers, and potentially the decrease of conscious shoppers (“Annual Report 2018”

20). Within the last six years, Inditex has invested over 2 billion dollars in technology development, in an attempt to integrate stores and online in order to streamline the shopping process and make it a more flexible experience for the consumer. According to the report, customers will be able to combine technologies while being in a physical store, for example, trying on a garment they ordered online or picking up an online order in store rather than having it shipped to their house (“Annual Report 2018” 52). The investment that Inditex has made in technology could be one of the leading factors in explaining Zara’s net sales of 18,021 million euros. Sustainability encourages profit because it recognizes that without a profit, a company could not stay in business for long. However, revenue and profit should be used to enhance the company by reducing the negative impact they make on the environment and people, not to further expand the company and its stores.

Environment

Interestingly enough, in the table of contents of Inditex’s 2018 Annual Report they list under the section “Our Priorities” sub-categories such as our customers, our people, integrated supply chain management, excellence of our products, circularity and efficient use of resources but do not explicitly list the environment. Similarly, in the same table of contents, under the heading “Sustainable Strategy” the following sections are listed: materiality analysis, stakeholder relations, Inditex’s contribution to sustainable development, and promotion and respect for human rights; yet, once again, there is no mention of the environment-one of the three main pillars of sustainability (“Annual Report 2018” 2). In the 2009 data analysis from Brodish et al., 30

Inditex scored a 0.57 out of 1 in the environmental section, in comparison to Mango’s, another

Spanish fast fashion brand, score of 0.61 (357). While the authors consider this score to be strong, Inditex’s score is still lower than their competitor’s score, demonstrating that there is more the company can, and arguably should be doing in the realm of sustainability and the environmental pillar. The 2018 Annual Report, under the subheading ‘circularity and efficient use of resources’ states, “At Inditex, we are committed to minimizing the impact of our actions on the environment. We incorporate the most innovative technologies to reduce our consumption and emission and we opt for using renewable energies” (42). However, not much else is listed in relation to the effect the company has on the environment.

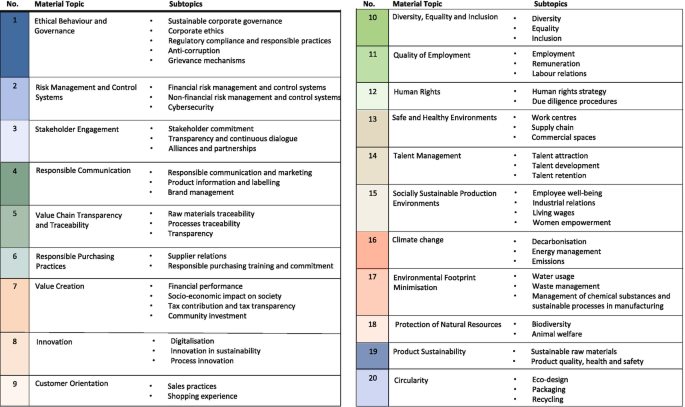

According to Popescu, in 2014 Inditex drafted their fourth consecutive materiality matrix where they prioritized the most relevant issues for the company. These issues, including green design, waste management, energy consumption, and recycling systems and management of the product end life, help the company evaluate their economic, social, and environmental impacts.

In this year, more than 60 percent of the Inditex suppliers respected the production standard, ensuring a sustainable environment for all wet processes for the Green to Wear product line.

Moreover, their 2020 objective was 0 discharge of hazardous substances (Popescu 342). Yet, in the 2018 Annual Report, it states that the “review, expansion and constant finetuning of our product health and safety standards” has facilitated progress towards the target of “Zero

Discharge of Hazardous Chemical” (28). This shows that the company’s goal of zero chemical discharge, set in 2014, was not met four years later (28). Moreover, while Isla in his speech to the General Assembly in July 2019, mentioned the increase in recycling programs, there was no mention of Inditex’s supposed commitment to eliminating hazardous substances. Popescu 31 mentions, “For the supplier wastewater management, Inditex works in collaboration with the

University of A Coruña, for the analysis of 280 water samples, to detect the five most relevant discharged chemical groups and their source of origin” (342). This collaboration between Inditex and the university helps improve the quality of Inditex’s runoff water and improve the suppliers’ waste water purification facilities (342). As a result of Inditex being a water-intense company, the effect they have on the environment is pressing. While Inditex continues to release goals and take steps towards improvement, it is not certain that change is actually being made.

Inditex is a company that was started on and continues to be rooted in the exploitation of its workers. According to Juan Fernandez, the head of the local textile union in Galicia which represents some of the company’s workers, Inditex only pays per piece of clothing sewn. Not only that, but, in many of the production factories, or for lack of a better word, sweatshops , employees earned approximately $500 a month in 2001, which was about half the average industrial wage (Pohl). In 2011, Zara was accused of accepting slave-labor working conditions in

Brazil. In the workshop, one worker explained to the reporter that “a pair of Zara jeans- which in

Brazil is sold for roughly R$ 200 ($126)- has a working cost of R$ 1,80 ($1.14). Such a sum is divided equally between all the people involved in the production system, which in the case of the pair of jeans takes about seven individuals” (Antunes). In the same source, the workers average monthly income was listed as approximately 569 dollars, for a working shift of no less than twelve hours. Going back to the definition of sustainability, specifically the social and fiscal 32 pillars of sustainability according to Brodish et al., human rights, established company standards, and a code of ethics are all aspects of a company that contribute to its level of sustainability.

As stated in Inditex’s 2018 Annual report, on December 12, 2016, the Board of Directors approved Inditex Group’s Policy on Human Rights which emphasizes the company’s commitment to human rights. Specifically, in regard to Inditex’s business model and labor human rights, the report lists priorities in rejecting forced labor, rejecting child labor, promoting diversity, respecting freedom of association and collective bargaining, protecting worker’s health and safety, and providing just, fair and favorable working conditions (Annual Report 2018 44).

The situation of Inditex’s workers is a tricky one. There is no denying that Inditex constantly exploits their workers, and has since the beginning; however, even Fernandez believes the corporation to be overall beneficial adding, “They’re [Inditex] one of the largest employers in the region…We need them here”’ (Pohl). Yet, Fernandez’s comment is particularly concerning since fast fashion and apparel companies, in general, employ millions of workers, a high percentage being young women. There needs to be an urgent push for developing and leveraging the power of local producers, communities, and environments, as well as a movement to reverse the negative impacts of this growth. In other words, while Inditex may claim they care deeply for their workers, and the workers themselves may acknowledge they need the job, this is not enough. The ultimate goal is to “create sustainable value within and beyond company… boundaries” (Garcia-Torres et al. 2), which is not currently the case for Inditex.

Juan Fernandez further adds that Inditex does not care about the conditions inside the factories, which often have a negative impact on workers. This is confirmed in the Brazil source, where the reporter lists the discovery of a fire extinguisher with an expiration date of 1998 33

(Antunes). Yet, according to the company themselves, they continuously insist that they routinely inspect the factories. Raul Estradera, a representative for Inditex stated, “We have a very close relationship with our suppliers.... and we check that they fulfill the legal minimums in terms of salaries, social security, health benefits, and working conditions.” (qtd. in Pohl). In the analysis done by Garcia-Torres et al. (2017) on Inditex’s annual report, they found:

Of the 198 actions under analysis, only 1% dealt with Responsible Consumption and End of Life, 5.5% addressed Raw Materials Sustainability… The analysis also showed that the highest proportion of actions (35%) related to human rights (Compensations and Benefits, Social Equality, Bargaining Power, etc.) … 18.

The emphasis on actions related to human rights in Inditex’s annual support is most likely due to the seriousness of these topics, taking into consideration the lawsuits the company has faced in the past, but also due to social and media pressure (Garcia-Torres et al. 18). The concern here revolves around these topics being “tip-of-the-iceberg” issues related to sustainability.

Addressing these topics will not truly put sustainable practices into action.

Current sustainability goals have been integrated into companies in order to develop a list of standards as a measurement tool. While these standards can act as agents for change, often times the promises companies make are empty. Specifically, “ sustainability reporting has been broadly attacked as ‘ greenwashing ’, or corporate rhetoric lacking consistency between talk and action” (Garcia-Torres et al. 2). Overall, the gap between sustainability reporting and actual sustainability practice is worrisome. Rather than focusing on reporting, in Inditex’s case to promote their image, there needs to be a large shift towards movement. According to Marcuello 34 et al., “Inditex takes the utmost care over the dissemination of its business facts and figures, since they affect its public reputation. The company first assesses the impact in the conventional media and then turns to the Internet to disseminate the message to a wider audience. Its website provides generous promotional information designed to convince readers of the company’s quality” (397).

In other words, how can we make sure that what Pablo Isla said during his speech about

Inditex’s sustainability goals this past July is true? Is sustainability really at the core of all decisions made at Inditex? Currently, we can only rely on what we are told by the companies themselves as we do not have access to the real story or what is really happening behind the scenes in relation to sustainability. While it is possible for a fast fashion company to become more sustainable, currently, it is not possible for them to become one-hundred percent sustainable. Yet, the case study of Inditex-Zara shows that a company whose business model seems completely incompatible with a sustainable business model can take steps in the right direction towards a more sustainable future for us all.

Works Cited

Alonso Álvarez, Luis. "Vistiendo a 3 continentes: La ventaja competitiva del grupo Inditex-Zara,

1963-1999 (Dressing 3 continents: the competitive advantage of Inditex group,

1963-1999)". Revista de Historia Industrial (Industrial History Review), Vol. 18, 2000, pp. 157-182.

Annual Report 2018. Inditex, www.inditex.com/documents/10279/619384/Inditex+Annual+Report+2018.pdf/25145dd

4-74db-2355-03f3-a3b86bc980a7. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

Antunes, Anderson. "Zara Accused of Alleged 'Slave Labor' in Brazil." Forbes, 17 Aug. 2011, www.forbes.com/sites/andersonantunes/2011/08/17/zara-accused-of-alleged-slave-labor-i

n-brazil/#20d43b501a51. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

Avendaño, Ruth, et al. "The Role of Market Orientation on Company Performance through the

Development of Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Inditex-Zara Case." Marketing Intelligence & Planning, no. 4–5, 2003, p. 220. Brodish, Stephanie, et al., "Fast fashion's knock-off savvy: Proposing a new competency in a

sustainability index for the fast fashion industry." Proceedings of the Northeast Business & Economics Association, 2011, pp. 355-58. Business Source Complete. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

Carrasco Rojas, Oscar, et al. "Efficiency, internationalization and market positioning in textiles

fast fashion". International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, issue 4, pp. 397-425. 36

Crofton, Stephanie. "Zara-Inditex and the Growth of Fast Fashion". Essays in Economic & Business History, vol. 25, 2007, pp. 41-53. Garcia-Torres, Sofia, et al., "Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: from

Sustainability Reporting to Action." Sustainability , vol. 9, no. 12, 6 Dec. 2017, pp. 1-27. Ghemawat, Pankaj, and José Luis Nueno. "Zara: Fast Fashion". Harvard Business School, 2006. Marcuello, Carmen, and Chaime Marcuello Servos. "NGOs, Corporate SocialResponsibility, and

Social Responsibility: Inditex vs. Clean Clothes". Development in Practice, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2007, pp. 393-403.

Mcginn, Daniel. "Fashionable Growth: A Conversation with Inditex CEO Pablo Isla".Harvard Business Review, 2017. Orcao Escalona, Ana, et al., "Global production chains in the fast fashion sector, transports and

logistics: the case of the Spanish retailer Inditex". Investigación Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, vol. 85, 2014, pp. 113-127. "Pablo Isla sets out Inditex's global sustainability commitments." Inditex , 16 July 2019, www.inditex.com/article?articleId=630055&title=Pablo+Isla+sets+out+Inditex%27s+glo

bal+sustainability+commitments. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

Pohl, Otto. "In Spain, a home-sewn exception to globalization." Christian Science Monitor, 26 July 2001, p. 8. Newspaper Source. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019. Popescu, Alexandra-Codruta. "On the Sustainability of Fast Fashion Supply Chains-

AComparison Between the Sustainability of Inditex and H&M's Supply Chains". Revista Tinerilor Economisti (The Young Economists Journal), Vol.1, Issue 24, 2015, pp. 29-40.

Case Study Integrated Valuation: Inditex

- Open Access

- First Online: 14 September 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Dirk Schoenmaker 3 &

- Willem Schramade 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Business and Economics ((STBE))

10k Accesses

This chapter applies the tools of the previous chapters to a particular company, Inditex, the largest fast fashion company in the world. The fast fashion industry faces major social (S) and environmental (E) challenges. Moreover, since the industry is characterised by high levels of outsourcing, those challenges tend to be hidden down the supply chain. The case study answers questions such as: how to calculate the integrated value of a company? Which company-reported data to use? How to fill the gaps from missing data in company reporting? We connect the company’s business model and purpose to its external impacts and transition challenges. This allows us to value on environmental (E), social (S), and financial (F) factors. We compute the company’s integrated value (IV) by summing FV, SV, and EV in several ways. The company’s IV turns out to be positive overall, but both positive SV and negative SV and EV turn out to be much larger than FV, which shows the importance of not netting. The large negative values need to be addressed: to be reduced and ideally eliminated. We therefore explore integrated value creation over time; how it can be improved; and how to communicate it to investors.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

- Business model

- Cost of equity

- Cost of debt

- Customer value proposition

- Double materiality

- Depreciation

- Enterprise value

- Environmental value (EV)

- External impacts

- Financial value (FV)

- Integrated value (IV)

- Integrated value creation

- Integrated valuation

- Investor presentation

- Inward perspective

- Key resources and processes

- Management quality

- Materiality

- Materiality assessment

- Monetisation factor

- Outward perspective

- Profit formula

- Quantification

- Sales-to-assets

- Social value (SV)

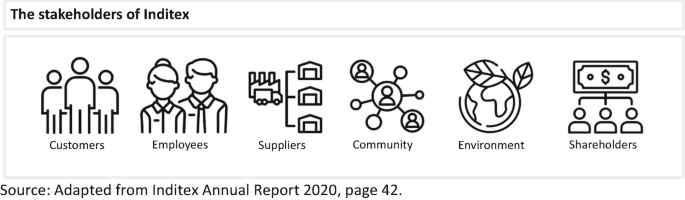

- Stakeholders

- Stakeholder impact map

- Total assets

- Transition scenarios

- Transition valuation scenarios

- True prices

- Value creation

- Value creation profile

- Value destruction

- Value driver

- Weighted average cost of capital (WACC)

This chapter applies the tools of the previous chapters, such as the equity valuation models of Chap. 9 and the social and environmental valuation models of Chap. 5 , to a particular company. It is a case study that gives an external perspective on the integrated value of Inditex as of January 2021 for educational purposes. It answers questions such as: how to calculate the integrated value of a company? Which company-reported data to use? How to fill the gaps from missing data in company reporting?

Inditex, or Industria de Diseño Textil, S.A., is a multinational clothing company, based in Arteixo, Spain. It is the largest fast fashion company in the world and operates over 7000 stores in almost 100 countries. The company is best known for its Zara brand, but also owns brands such as Bershka, Massimo Dutti, Pull&Bear, Zara Home, and Oysho. The fast fashion industry faces major social (S) and environmental (E) challenges. Moreover, since the industry is characterised by high levels of outsourcing, those challenges tend to be hidden down the supply chain.

In the following sections, we briefly introduce the nature of the company’s activities and its value drivers. We then connect the company’s business model and purpose to its external impacts and transition challenges. This allows us to value the company in various ways.

First, we make an assessment of its financial value F, including the effect of sustainability issues (inward view, Sect. 11.3 ), in several scenarios. We use the discounted cash flow (DCF) model for calculating F.

Second, we estimate Inditex’ value on S and E (outward view, Sect. 11.4 ), with flows projections on S and E, similar to those of an ordinary DCF. These calculations indicate that there is significant value destruction on E and S, but also significant value creation on S.

Third, we compute the company’s integrated value (IV) by summing FV, SV, and EV in several ways (Sect. 11.5 ). The company’s integrated value turns out to be positive overall, but both positive SV and negative SV and EV turn out to be much larger than FV, which shows the importance of not netting. The large negative values need to be addressed: to be reduced and ideally eliminated. We therefore explore integrated value creation over time; how it can be improved; and how to communicate it to investors. See Fig. 11.1 for a chapter overview.

Chapter overview

After you have studied this chapter, you should be able to:

link a company’s business model to its external impacts and transition exposures

build a company valuation model that incorporates F, S, and E

create and interpret a company value creation profile

assess corporate investments on F, S, and E in the context of the company’s value creation profile

critically assess a company’s information provisions on sustainability issues and the gaps therein

1 Introduction to Inditex

Inditex, officially known as Industria de Diseño Textil (which translates to ‘Textile Design Industry’), is a Spanish clothing company with a large portfolio of global fast fashion brands such as Zara, Bershka, Pull&Bear, and many more. With more than 7200 stores in 93 countries it is the biggest fast fashion group in the world.

In 1975, Amancio Ortega and his wife Rosalia Mera opened their first fashion store for their brand Zara. Later that year, Ortega hired a local professor, José Maria Castellano, who would be responsible for growing the company’s computing capabilities. In 1984, Castellano was appointed CEO after having developed a revolutionary design and distribution method that greatly improved the company’s performance. A year later Inditex was created as a holding company for Zara and its production facilities. After expanding internationally by opening a store in Portugal in 1988, the company started developing other brands such as Pull&Bear in 1991, Lefties in 1993, and Bershka in 1998.

When Inditex had its IPO in 2001 at the Spanish Stock Exchange, the company was valued at €9 billion. Over the course of the 2000s the company experienced exponential growth, achieving a milestone 2000 stores in 2004 and 4000 stores in 2008. In the meantime, Castellano was replaced by current CEO Pablo Isla in 2005. While the company has grown to become the largest fashion retailer in the world, it was hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic as the company saw its revenue decrease by 27.7% in 2020.

The company operates a number of brands but the Zara and Zara Home brands still account for more than two-thirds of sales. Geographically, the company’s sales are skewed to Europe (over 60%, of which 25% in Spain), with significant presences in Asia-Pacific (25% of sales) and the Americas (14% of sales).

Inditex claims to employ a ‘multi-concept strategy’, with ‘market segmentation through distinctive concepts’; independent management teams; a global presence; and the same business model across all concepts—i.e., with a high frequency of new collections; and outsourced production in low-cost countries. The business model is discussed further in Sect. 11.2 .

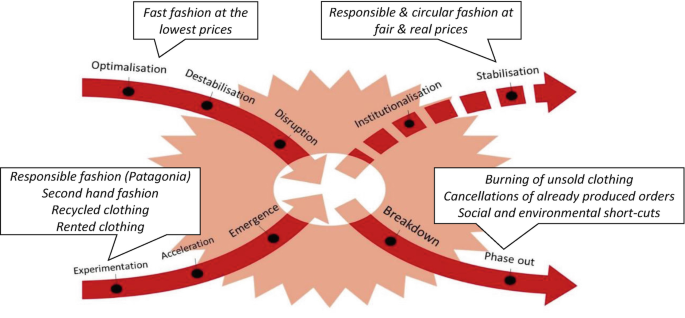

Like any industry, the fast fashion industry is exposed to trends that affect its growth and the way it operates. According to the international consultancy PwC, the industry’s key trends are sustainability and digitalisation. Footnote 1 For example, 3D design was quick to substitute fashion shows when those were no longer possible due to Covid-19 restrictions. Meanwhile customers are becoming more critical about clothing companies’ sustainability performance, and they demand better information on the footprint of individual pieces of clothing. As a result, supply chain transparency is becoming more important and increasingly enabled by digitalisation.

Company Value Drivers

The financial valuation analysis (Sect. 11.3 ) starts with Inditex’s value drivers: sales, margins, and capital. Table 11.1 shows Inditex’s sales. Inditex has produced consistent growth numbers during the 2010s with a minor blip in 2013, due to additional investments in refurbishing flagship brands and opening many new stores globally. The lower growth at the end of the decade indicated to some, including Morgan Stanley, that the company’s growth profile was fading. Footnote 2 While this could have played a part in the devastating sales drop in 2020, it should be largely attributed to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic which saw a staggering drop in sales globally due to lockdown measures. However, with global fashion sales in 2020 declining between 15 and 30%, Inditex seemingly took a larger hit than most. Footnote 3

Inditex’s profitability has been remarkably consistent throughout the last decade, especially in terms of EBIT which ranged from 16.7 to 19.6% over the course of 9 years (see Table 11.2 ). The company’s EBITDA has also performed well, although decreasing slightly over time. The strong increase in EBITDA in 2019 compared to 2018 is furthermore noticeable. This indicates that, although the company strongly improved its gross profit, there was also a significant growth in depreciation considering that EBIT stayed the same. The increased depreciation can be attributed to the 30.9% growth in assets during 2019.

Except for 2020, Inditex showed a strong financial performance over the past decade. Inditex’s growth during the last decade is noticeable in the development of its assets, which has more than doubled since 2010 (see Table 11.3 ). In fact, assets grew faster than sales (falling sales-to-assets ratio), possibly indicating that the company is operating less efficiently than before. For most of the decade, its sales-to-assets ratio was around 1.2, which is similar to other companies in the fashion sector, such as H&M. In contrast to other financial numbers, Inditex’s capex (investments) has been relatively inconsistent, particularly from 2017 onwards. In 2020 the capex was even negative, which means the company divested some of its assets. Finally, the Return on Assets has been healthy.

2 Inditex’ Business Model and Transition Challenges

Ultimately, to value Inditex on F, S, and E, we need to understand the company’s external impacts and transition challenges. This in turn requires an understanding of the company’s business model and purpose.

2.1 Business Model

In both its company profile and its 2020 Annual Report (AR 2020), Inditex spends several pages explaining its business model. Inditex claims to have a unique business model, ‘fully integrated, digital and sustainable’. But is it? And how can it be described in a more objective way? As discussed in Chap. 2 , Johnson et al. ( 2008 ) argue that a successful business model has three components:

A customer value proposition : the model helps customers perform a specific ‘job’ that alternative offerings do not address;

A profit formula : the model generates value for the company through factors such as the revenue model, cost structure, margins, and/or inventory turnover;

Key resources and processes : the company has the people, technology, products, facilities, equipment, and brand required to deliver the value proposition to targeted customers. The company also has processes (training, manufacturing, services) to leverage those resources.

For Inditex, these three components can be described as shown in Fig. 11.2 .

The three components of Inditex’ business model. Note: Authors’ assessment based on Annual Report 2020. At Inditex (and many other companies) sales/invested capital (IC) is higher than sales/assets, since invested capital is lower than total assets, from which short-term liabilities are deducted (and networking capital added) to arrive at IC

Crucially, Inditex’s customer value proposition is driven by frequently issuing new collections. To minimise costs and maintain high levels of ROIC, the garments are produced in an outsourced supply chain over which the company exercises strong bargaining power but limited control. This means large negative external impacts can be created beyond the boundaries of Inditex’ legal entities Footnote 4 —and indeed they are, as we will see later on. Strengths from an F perspective can be weaknesses from an S and E perspective. Box 11.1 provides a critical perspective on Inditex’s marketing.

Box 11.1 Sustainable Marketing

Fuller ( 1999 ) defines sustainable marketing as ‘the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the development, pricing, promotion, and distribution of products in a manner that satisfies the following three criteria: (1) customer needs are met, (2) organisational goals are attained, and (3) the process is compatible with ecosystems’.

The above definition is over 20 years old, and with current knowledge one could argue that the third criterion should be refined to ‘within social and planetary boundaries’. However, that does not change our judgement: that Inditex succeeds at criteria (1) and (2) while failing at (3). Footnote 5 To stay within planetary boundaries, Inditex has to adjust its marketing mix, do serious product system life cycle management, and broaden its view on customer value. This could mean switching to a model with lower product volumes, longer product lives, and selling fashion as a service, renting or leasing clothing instead of selling it. Such new models would cannibalise the company’s existing models, which makes it a tough call for management. Still, it probably makes sense to at least do this in an experimental way alongside the current model, and the company seems to have started on this journey.

2.2 Purpose

A company’s purpose is the reason for its existence, which is grounded in the way it creates value for its clients and other stakeholders. Hence, it should be closely related to its business model and competitive position. In the case of Inditex, it is hard to find a stated purpose.