Research Using Vertebrate Animals

If you are a principal investigator planning to use live vertebrate animals for research, research training, or biological testing, this page explains how to adhere to requirements, prepare a strong application, and manage your grant.

Table of Contents

Animal policies, planning animal research is a team effort, consider alternatives to using animals, check for limits on your planned animal species or source, is your institution assured by olaw, how to get an olaw assurance, working with your iacuc, write your protocol, write the application: indicate use of animals, answer the three points in the vertebrate animals section, how niaid reviews applications using research animals, understand codes on your summary statement, niaid will send a just-in-time request, iacucs monitor your progress, you'll have semiannual reviews and inspections, avoid suspension of animal activities, know your reporting requirements, keep your records accessible.

You must follow the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (referred to as PHS policy below) and the Animal Welfare Act .

The PHS policy is summarized in the NIH brochure What Investigators Need to Know About the Use of Animals .

The PHS definition of research animal use includes production of custom antibodies and animals obtained for their tissues. Read more at Applicability of the PHS Policy .

Read about NIH animal research, policies, and crisis management at OER Animals in Research .

Peer reviewers will evaluate your application based on your compliance, so it's important to know what's expected of you and your institution.

When you apply for NIAID funding, you need to answer the four points in the Vertebrate Animals Section (VAS) of your grant application. Most grant types, including research grants such as the R01 and Exploratory/Developmental Grant (R21) use electronic application. Find guidance on completing the VAS in the Worksheet for Review of the Vertebrate Animal Section (PDF) and OLAW's 30-minute training module on how to Complete the Vertebrate Animals Section (VAS) .

If your application receives a fundable overall impact score, have your animal use protocol reviewed and approved by an institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC), which evaluates your institution's animal research program.

To receive an award, you must have IACUC approval, and your institution must have an Animal Welfare Assurance approved by the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW).

If you have domestic subaward agreements, those organizations also need IACUC approval and an assurance. Read more in the Subawards (Consortium Agreements) for Grants SOP .

For foreign awards and subawards, learn more below at IACUC Requirements Vary for Domestic and Foreign Institutions.

To find out if your institution is assured, see the OLAW Domestic Institutions With a PHS Approved Animal Welfare Assurance or Foreign Institutions With a PHS Approved Animal Welfare Assurance . Domestic assurances are valid up to four years, then they must be renewed. Foreign assurances last up to five years and may be renewed only for current or pending awards involving vertebrate animals. Learn more about the IACUC in the OLAW IACUC 101 Series .

It's also a good idea to find out if your institution has animal facilities accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC).

- AAALAC is a private, nonprofit organization; participation in its accreditation program sends the message that your institution is committed to high-quality animal care and use.

- OLAW accepts AAALAC accreditation in lieu of some required documentation. Non-accredited institutions are required to provide a copy of their most recent semi-annual report of program review and facility inspection with their assurance.

To reduce administrative burden, domestic institutions have the option to use sections of the AAALAC Program Description to complete parts of the OLAW Domestic Animal Welfare Assurance.

Planning and Preparing for Animal Research

Planning and teamwork are key to preparing a successful application. An animal research application requires a lot of work, so start early, leave time for unanticipated issues, and involve experts in your project from the beginning.

Ask senior institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) members to validate your ideas and methods. Consult with the attending veterinarian about available facilities, equipment, personnel, and products.

For example, the veterinarian may know of a new analgesic that introduces fewer variables into the research. The institutional business official who submits your grant application should also be comfortable with your proposal.

These early consultations protect you and your institution. Since NIH allows just-in-time IACUC approval of animal use protocols, a PI can move a research project all the way through NIH initial peer review before an IACUC has a chance to see it.

If your IACUC has last-minute problems with your protocol, e.g., you have no biosafety level 4 facilities for Ebola research, you might not receive funding you otherwise could have received.

When planning your research, consider whether you can achieve your scientific objectives while reducing the number of animals, refining the use of animals by minimizing their pain or distress, using a lower order species, or designing your experiments to avoid using animals at all.

USDA regulations require that investigators search the scientific literature for alternatives. Conduct this search while you plan your experiments. Include the search results in the animal study protocol for your IACUC approval.

Considering alternatives during the planning stage gives you enough time to incorporate methods that benefit the animals and the science. It also shows peer reviewers that you are thorough and reduces your chances of a bar to award because of animal welfare concerns.

If you must use animals, here are some ideas to limit animal use and discomfort:

- Limit animal involvement by using the minimum number required to obtain valid results.

- Use non-animal methods, such as mathematical models, computer simulation, or in vitro biological systems.

- Avoid or minimize animal discomfort, distress, and pain as is consistent with sound scientific practices.

- Use appropriate sedation, analgesia, or anesthesia when your procedures will cause more than momentary pain or distress. Do not perform surgical or other painful procedures on non-anesthetized animals.

- Select the lowest phylogenetic species appropriate for the experiment if animals are necessary.

As you plan, remember that NIH or HHS policies may affect your choice of species or source of animals. Review existing policy through the OLAW website, and for new policies, watch the NIH Guide and NIAID Funding News .

Here's a summary of the latest policies on chimpanzees, dogs, and cats:

- NIH will not consider or fund any competing applications involving chimpanzees unless the research fits the definition of “noninvasive” as described at 42 CFR Part 9 . Learn more in the NIH May 26, 2016 Guide notice .

- USDA Class A dealers

- Privately-owned colonies (e.g., colonies established by donations from breeders or owners)

- Client-owned animals (e.g., animals participating in veterinary clinical trials)

- For details, see the December 17, 2013 Guide notice .

- Awardees must not use NIH funds to get cats from Class B dealers. See the February 8, 2012 Guide notice .

Before NIAID can award your grant, your institution and all performance sites involved in animal work must have an Animal Welfare Assurance on file with OLAW and provide certification of IACUC approval.

There are three types of Animal Welfare Assurances: domestic, interinstitutional, and foreign.

- Domestic assurances typically remain in effect for up to four years and can be renewed.

- The organizations agree to conduct the project according to the assurance of the covered organization.

- Timeframes for these assurances are project specific and approved for the life of the project, up to five years. For example, a small business subcontracting animal work to a performance site must apply for a new interinstitutional assurance each time it successfully competes for a grant.

- Foreign assurances are for foreign institutions that are grantees or subaward partners to a domestic grantee.

A foreign entity must state that it will comply with the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals and the applicable laws, regulations, and policies of the country in which the research will be conducted. For example, a German institution or performance site should adhere to German laws governing the care and use of laboratory animals.

- Foreign assurances may be renewed if there is a current or pending award that involves vertebrate animals.

- Even without an assurance, an institution may apply for funding or be named as a performance site.

- If we plan to fund a new award, we will ask OLAW to negotiate a new assurance with your institution. For a direct award, foreign institutions do not need to submit certification of IACUC approval.

- For an indirect or subaward from a domestic institution, the domestic institution must provide the verification of IACUC approval for all activities conducted at the foreign institution (i.e., certification that the activities conducted at the foreign performance site are acceptable to the grantee.)

Learn about IACUC requirements for foreign and domestic awards and subawards below at IACUC Requirements Vary for Domestic and Foreign Institutions.

Institutions that collaborate with grantees through a subaward are required to have an assurance, whether domestic or foreign.

- If the institution doesn't have an assurance, OLAW will negotiate one with the grantee.

- The grantee may amend its assurance to include a collaborating institution; in this case, the grantee takes full responsibility for the animal care and use program of the collaborating institution.

- Read more in the Subawards (Consortium Agreements) for Grants SOP .

If your institution has never had an assurance, don't worry about it when you apply. NIAID grants management or program staff will contact OLAW to negotiate an assurance with your institution if you're likely to be funded based on peer review results, e.g., your percentile or overall impact score is within NIAID's payline.

For that process, OLAW will send your institution an electronic packet that includes a sample assurance and PHS policy information. IACUC members and other experts at your institution should collaborate to draft the assurance, inserting your institution's animal policies and procedures where appropriate.

Follow the format shown at OLAW's sample Animal Welfare Assurance for Domestic Institutions , Interinstitutional Assurance , or Animal Welfare Assurance for Foreign Institutions .

OLAW will review your institution's domestic assurance for compliance with federal policies. If acceptable, OLAW approves it and your institution is assured. If not, OLAW will prompt your institution for more information until the responses describe your animal care and use program in compliance with the PHS Policy and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . Your application is barred from an award until an approved assurance is in place.

When reviewing your institution's animal welfare assurance, OLAW will evaluate several items, including veterinary care, personnel qualifications and training, occupational health and safety, IACUC procedures, and animal facilities and husbandry.

What OLAW Looks For

Veterinary care.

When reviewing your institution's domestic assurance, OLAW will evaluate several items, including applicability, lines of authority, veterinary care, IACUC procedures, personnel qualifications and training, occupational health and safety, and animal facilities and husbandry.

All veterinary programs should provide for the following:

- Access to animals and periodic assessment of their well-being

- Appropriate facilities, personnel, equipment, and services

- Treatment of diseases and injuries and the availability of emergency, weekend, and holiday care

- Guidelines for animal procurement and transportation

- Preventive medicine

- Pre-surgical planning, training, monitoring, and post-surgical care

- Pain relief, including analgesics, anesthetics, and tranquilizers

- Euthanasia. Follow the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals

- Drug storage and control

The veterinarian must have program authority and responsibility for the institution’s animal care and use program, including access to all animals. He or she must also have the authority to implement the veterinary care program and oversee the adequacy of other aspects of animal care and use, e.g., animal husbandry, nutrition, sanitation practices, and hazard containment.

The size of the veterinary staff depends on the institution and the size and nature of its animal program. Consultant or part-time veterinary services may be appropriate for small programs with limited numbers of animals.

Do not include the veterinarian's resume as an assurance attachment. Instead, describe the veterinarian's qualifications in the assurance documentation. Follow the format shown in OLAW's example assurances at Sample Documents .

Personnel Qualifications and Training

Your institution must ensure that staff working with animals are appropriately trained. This includes investigators, animal technicians, and other personnel involved in animal care, treatment, or use on research or testing methods that minimize the number of animals used as well as animal pain and distress.

For more information, read Education and Training in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: A Guide for Developing Institutional Programs , developed by the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research .

Occupational Health and Safety

OLAW makes sure your institution has an occupational health and safety program for all personnel who work with animals. The program will depend on the facility, research activities, hazards, and animal species involved. Minimally, the program should include the following:

- Control and prevention strategies

- Hazard identification and risk assessment

- Facilities, equipment, and monitoring

- Personnel training

- Personal hygiene

- Animal experimentation involving hazards

- Personal protection

- Medical evaluation and preventive medicine for personnel

- Where appropriate, special precautions for personnel working with nonhuman primates

For guidelines on establishing and maintaining an effective safety program, check out Occupational Health and Safety in the Care and Use of Research Animals , published by the National Research Council .

Animal Facilities and Species Inventory

Institutions provide a facility and species inventory as part of their domestic assurance. Follow the format shown at Facility and Species Inventory in OLAW’s Domestic Assurance Sample Document .

OLAW uses this information to assess the nature and size of the animal care and use program and evaluate the adequacy of other program components, e.g., veterinary care and occupational health and safety.

Your IACUC is an oversight body appointed by an official at your institution, such as the chief executive officer. See the OLAW IACUC Handbook, Third Edition . OLAW relies on the IACUC to enforce PHS policy and your institution's animal policies.

As outlined in PHS Policy IV.B 1 through 8 , IACUCs do the following:

- Institutional definitions of a "significant change" vary. Be sure you know your institution's policy. Implementing a significant change without IACUC prior approval is a serious violation of PHS policy.

- For more information, see OLAW Topic Index—Protocol Review .

- Monitor the animal care and use program, including semiannual program review and facility inspection and report of the IACUC evaluations to the institutional official

- Review concerns involving the care and use of animals

- Make recommendations to the institutional official on the institution’s animal program, facilities, or personnel training

- Be authorized to suspend a previously approved protocol in instances of noncompliance

- Evaluate compliance with institutional policies

- Report annually and notify OLAW of suspensions and instances of serious noncompliance with PHS policy. See OLAW Reporting Noncompliance for guidance on what an IACUC should report to OLAW.

- Ensure that personnel working with animals are appropriately trained and qualified

Find out your institution's policies before you plan your research. In most institutions, policies for research animals are a combination of institutional and USDA and PHS requirements. Some are more stringent than others, so a procedure you performed at another institution may not be acceptable at your current workplace.

IACUC Requirements Vary for Domestic and Foreign Institutions

Identify your situation below for a summary of IACUC requirements

- Follow all the IACUC requirements outlined in this tutorial and by OLAW

- The domestic institution's IACUC reviews and approves the animal activity as described in the application.

- Both institutions must have an OLAW assurance.

- The foreign subawardee should also follow the instructions in the next section.

- The foreign institution doesn't need its own IACUC unless required by local law.

- The foreign institution must have an assurance. Follow the format shown at OLAW's sample Animal Welfare Assurance for Foreign Institutions . It states that the institution will comply with your country's laws, regulations, and policies governing the care and use of laboratory animals and follow the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals .

How Your IACUC Is Structured

Your IACUC will have at least five members, including people with the following backgrounds:

- A veterinarian with experience in laboratory animal science and medicine, who has direct or delegated authority and responsibility for activities involving animals at the institution.

- A practicing scientist experienced in research with animals.

- A person whose primary concerns are in a nonscientific area, e.g., an ethicist, lawyer, or member of the clergy.

- A person not affiliated with the institution who represents community interests and who is not a laboratory animal user.

Other IACUC members are usually faculty members and fellow researchers who are familiar with the issues you are facing and can serve as resources to help you prepare the best possible application.

Add Animals to the Application

Coordinate writing your application and protocol. Be sure to write and submit your protocol early enough for the IACUC review. When you send your protocol to your IACUC, it is extremely important that the substantive information is consistent with what you proposed in your grant application. Depending on how your IACUC tracks protocols, administrative details like PI name and application title may vary or be omitted.

Most IACUCs require investigators to submit information about proposed animal use on an institutional protocol review form. Before writing your protocol, consult with the attending veterinarian on the latest technologies and procedures that could improve your approach. Also send the veterinarian a draft of your protocol to resolve any issues before it goes to the IACUC. A standard animal protocol includes the following information.

- Description of project. Help IACUC members understand your animal procedures by avoiding technical language only people in your field will understand. Use visual aids, such as flow charts and bullets, to illustrate your points or break up text.

- Justification for using animals. Describe why an animal model is necessary. If you're studying a human health problem, state its cause, existing therapies, and the potential contribution of your experiments to further its understanding. Use lay language, explaining all medical terms and defining acronyms the first time you use them.

- Non-human primates, such as monkeys, marmosets, and baboons

- Large animals, such as cats, dogs, and pigs

- Rodents, such as hamsters, rats, and mice

- Non-mammalian vertebrates, such as poultry, reptiles, and fish

Your rationale for using a species may be size or availability; the existence of previous work or laboratory data that validates the use of a certain animal model; or the availability of reagents.

- Justification for number of animals. Request the amount of animals you need and explain why. Use the minimum number needed to yield statistically significant results.

- Consideration of alternatives. Convince IACUC members that you have adequately explored alternative methods. Use techniques to minimize pain and distress. These are known as "refinements" to your protocol. List databases you searched and when, citations derived, and the keywords or search strategy. List other sources, such as journal articles, presentations, and colleagues.

- Description of animal procedures. Include non-surgical methods, such as injections and sample collections; surgical methods, such as suturing and anesthesia; and other measures, such as pre-anesthetic fasting, drugs, and care during recovery.

- Assurance that qualified staff will perform work. Name all personnel who will be working on your study, along with their animal research experience and familiarity with your proposed procedures. If you or someone on your staff does not have the necessary experience, list experts at your institution who can provide training. Your IACUC will have to verify that this training took place before animal work can begin.

- Endpoint criteria. Choose endpoints that achieve the aims of the study and avoid unnecessary pain and distress. Include the criteria you will use to decide when to intervene or end animal use in the study, e.g., pain that cannot be controlled with analgesics, tumor size, and stage of disease. Interventions include euthanasia, treatment, or discontinuance of procedure. Many institutions have default criteria, so check with your IACUC for guidance.

If you're using live vertebrate animals (including production of custom antibodies and animals obtained for their tissues), you'll need to answer "Yes" to the question "Vertebrate animals, yes or no" in Item 2 of the Other Project Information component in your grant application.

Remember that your application covers all performance sites, including subaward partners, collaborators, and others involved in the research. Even if the animal work will be done somewhere other than your institution, mark "yes."

Follow the instructions for Vertebrate Animals in the SF 424 Form Instructions.

Go to Determine Institutional Resources for a brief description of what you need to put in the application.

To see if your institution or performance site is assured, refer to OLAW's Domestic Institutions With a PHS Approved Animal Welfare Assurance or Foreign Institutions With a PHS Approved Animal Welfare Assurance .

Peer reviewers can adjust your overall impact score based on your responses to the three points below. An incomplete or missing response could exclude your application from review or lead to a bar to award.

Address these three points in the Vertebrate Animal Section (VAS) of the Research Plan:

- Describe the proposed procedures to be used that involve vertebrate animals. Identify the species, strains, ages, sex, and total numbers of animals by species. If dogs or cats are proposed, provide the source of the animals. (You must also justify the total number of animals in the approach section of your Research Strategy.)

- Justify that the species are appropriate for the proposed research. Explain why the research goals cannot be accomplished using an alternative model (e.g. computational, human, invertebrate, in vitro).

- Describe the interventions including analgesia, anesthesia, sedation, palliative care and humane endpoints to minimize discomfort, distress, pain, and injury.

In addition, if you will euthanize animals and your method will not be consistent with American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals guidelines, you will need to describe and scientifically justify your methods on the Cover Page Supplement form.

Follow the instructions for Vertebrate Animals in the SF 424 Form Instructions. NIH's Worksheet for Review of the Vertebrate Animal Section (VAS) (PDF) describes requirements and provides an example of a complete VAS. OLAW also offers a 30-minute training module on how to Complete the Vertebrate Animals Section (VAS) .

Since there is no page limit for this section, use as much space as you need to convince reviewers that you'll do everything right. Don't assume reviewers will automatically know what you're talking about. Help them understand why your approach will yield the best results and how you will limit animal pain and distress to that which is scientifically necessary.

After You Apply

When assessing the scientific merit of an application, all NIH initial peer review committees use the same review criteria.

Peer reviewers also evaluate your project's compliance with federal requirements for animal research, rating your application based on your responses to the three points in the Vertebrate Animals Section. Any problems may negatively affect your overall impact score.

Learn more about peer review in general at Review Process .

Scientific review officers will code your summary statement to reflect your use of research animals. Such codes can also indicate assurance status, need for IACUC review, missing information, reviewer concerns, euthanasia method inconsistent with AVMA guidelines , or the fact that there are no problems and NIAID can issue your award. See Research Animals Involvement Codes for a complete list.

Codes that result in a bar to award must be resolved before NIAID can release your award. If your summary statement lists such a code, contact the program officer listed on your summary statement right away.

Learn more about summary statements at Scoring and Summary Statements .

After you've cleared initial peer review, we'll send you a request for just-in-time information if your application is in the fundable range.

For animal research, you will need to send in your certification of IACUC approval and resolve any reviewer concerns before NIAID can issue your award. For more on the just-in-time process, see Responding to Pre-Award Requests ("Just-in-Time") .

During and After Award

By signing your application, your institutional official promises the federal government that your institution will comply with all terms and conditions of award, including those covering animal care and use. Monitor your work closely. As PI, you are accountable for all activities involving animals during the project.

Your approved animal use protocol is a contract between you and your IACUC, stipulating that your project will follow all institutional policies and procedures. You must obtain IACUC approval before you make any significant changes to the research, including the following:

- Switching from nonsurvival to survival surgery

- Introducing procedures that result in greater pain, distress, or degree of invasiveness

- Using different anesthesia, analgesics, sedation, or experimental substances

- Changing PI, species, study objectives, or methods of euthanasia

Consult your IACUC for guidance. The definition of a "significant change" varies from institution to institution, and your IACUC actions depend on the nature of your significant change.

If you're planning to make a significant change to your project, also contact your program officer right away. The NIH Grants Policy Statement requires grantees to obtain prior approval from NIH for changes in scope. For a list, see Manage Your Grant .

You will also need to get a new IACUC approval every three years; some IACUCs may require it sooner. Institutional officials and IACUCs do not have authority to extend an IACUC approval beyond its expiration date. Conducting research in the absence of a valid IACUC approval constitutes noncompliance with PHS policy and it is reportable to OLAW.

As part of its semiannual program review and facility inspection, your IACUC will conduct routine assessments of institutional animal activities. Refer to the OLAW Semiannual Program Review and Facility Inspection Checklist .

This review covers institutional policies and responsibilities, IACUC membership and functions, and IACUC record keeping and reporting procedures. It also looks at the adequacy and appropriateness of animal environment, housing, and management; veterinary care; staff training; emergency preparedness; and occupational health and safety programs.

A facility review is a physical inspection of buildings, areas, and vehicles (including satellite facilities housing animals for more than 24 hours) used for confinement, transport, maintenance, breeding, or experiments, including surgery.

Your lab may be inspected as part of a facility review, or your IACUC may randomly visit to verify that you are following your protocol.

IACUCs report the results of their program evaluation and facility inspection to the institutional official for animal welfare. These reports describe any deficiencies found and include plans and schedules for correcting each one.

Institutional officials submit semiannual IACUC reports to OLAW only if requested or if the institution is submitting a new or renewal assurance and is not accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care .

Your IACUC can suspend your project if it finds serious or continuing noncompliance with PHS policy or your institution's assurance or deviations from the approved protocol or the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals .

If you have a subaward agreement, noncompliance at the subaward organization can also provoke a suspension. See the Subawards (Consortium Agreements) for Grants SOP for more information.

Your IACUC will convey its reasons for a suspension to the institutional official for animal welfare, who will take corrective measures and report the situation to OLAW.

OLAW can withdraw approval of your institution's assurance though this is extremely rare. Should this happen, your institution would become ineligible for spending NIH funds on research activities involving animals, and NIAID may seek to recover its monies. NIH may allow expenditures for the maintenance and care of animals.

OLAW can also place restrictions on an institution's assurance until compliance problems are fully resolved. OLAW always emphasizes corrective rather than punitive actions and will restrict or withdraw approval of an assurance only if an institution's efforts to correct its problems are unsuccessful.

During the life of your grant, there are several reporting requirements for NIAID. For example, you'll need to get your certification of IACUC approval at least every three years.

At least once every 12 months your institution is required to submit a report from your IACUC to OLAW, signed by the institutional official for animal welfare and IACUC chairperson. The report includes the following.

- Changes in the institution's program of animal care and use

- Change of institutional official or IACUC membership

- Dates when the IACUC conducted its semiannual program evaluations and facility inspections

- Minority IACUC views, i.e., dissenting opinions attached to required reports

Annual reports are due by December 1 for the previous fiscal year—October 1 to September 30. Your institution sends the report as a PDF email attachment to [email protected] . If you have questions or need assistance, call OLAW at 301-496-7163.

In addition to the annual report, your institutional official for animal welfare must notify OLAW promptly of any of the following:

- Serious or continuing noncompliance with PHS policy

- Serious departures from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . Note that exceptions listed in the Guide are not departures.

- IACUC suspensions

Send preliminary and final reports of noncompliance, deviations, and IACUC suspensions to [email protected] .

Learn more about the reporting process and see a sample final report at OLAW Reporting Noncompliance .

For general reporting requirements, see Reporting Requirements During Your Grant and Final Reports for Grant Closeout .

You must keep your project records accessible for three years after the grant ends. If an issue arises, NIAID must be able to verify the records, which must include all data and fiscal information.

Under PHS policy your institution is required to maintain the following records for a minimum of three years:

- Assurance approved by OLAW

- Minutes of IACUC meetings

- Records of IACUC activities and deliberations

- Minority IACUC views

- Documentation of protocols reviewed by the IACUC, and proposed significant changes to protocols (this documentation must be maintained for an additional three years after completion of animal activities)

- IACUC semiannual program evaluations and facility inspections, including deficiencies identified and plans for correction

- Accrediting body determinations

Through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the public can access information about your grant. If someone formally requests non-proprietary information about your application, our FOIA office will provide it.

Previous Step

Have questions.

A program officer in your area of science can give you application advice, NIAID's perspective on your research, and confirmation that your proposed research fits within NIAID’s mission.

Find contacts and instructions at When to Contact an NIAID Program Officer .

Related Rules & Policies:

- Animals in Research for Grants SOP

- Bars to Grant Awards—Research Animals SOP

- Sharing Model Organisms SOP

- ELEMENTARY TEACHING , INTEGRATED CURRICULUM ACTIVITIES

Animal Research Project for Kids at the Elementary Level in 2024

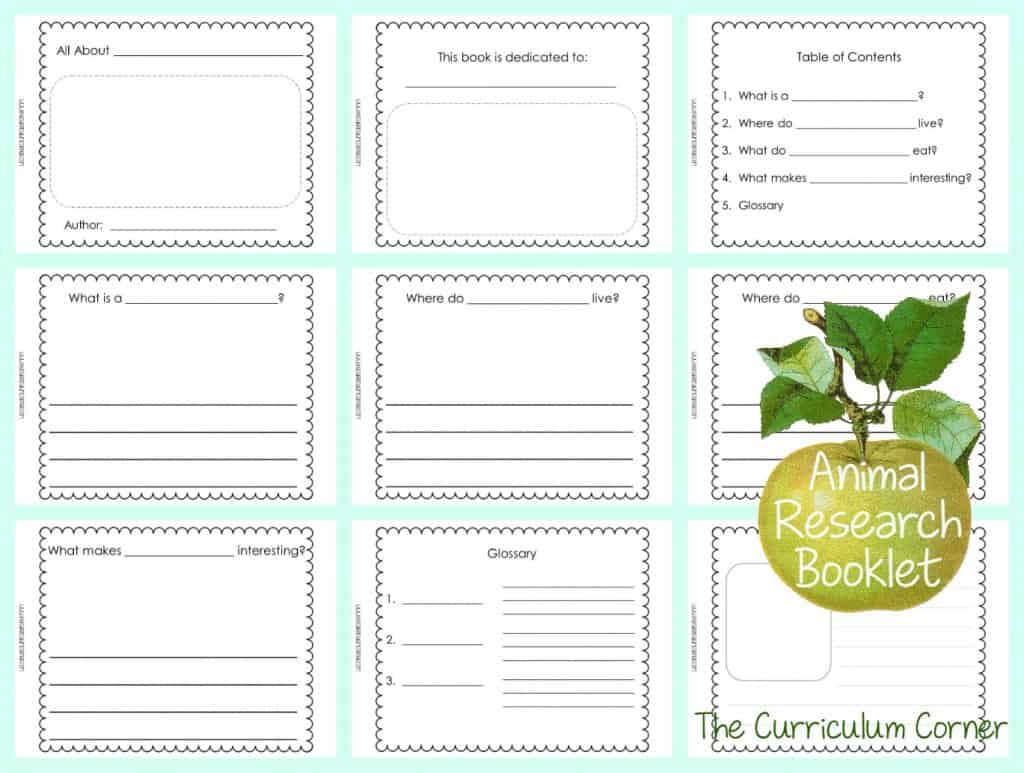

Whether you are doing a simple animal study or a fully integrated science, reading, and writing unit, this animal research project for kids includes everything you need. From the graphic organizer worksheets and guided note templates to the writing stationary, printable activities, projects, and rubrics.

Thousands of teachers have used this 5-star resource to have students complete self-guided animal research projects to learn about any animal they choose. The best part is, the resource can be used over and over again all year long by just picking a new animal! Learn all about this animal research project for kids at the elementary level below!

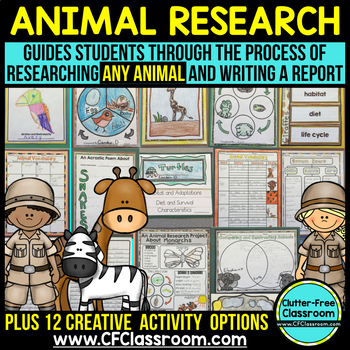

What is the Animal Research Project?

The animal research project is a resource that is packed with printable and digital activities and projects to choose from. It is perfect for elementary teachers doing a simple animal study or a month-long, fully integrated unit. It’s open-ended nature allows it to be used over and over again throughout the school year. In addition, it includes tons of differentiated materials so you can continue to use it even if you change grade levels. Learn about what’s included in it below!

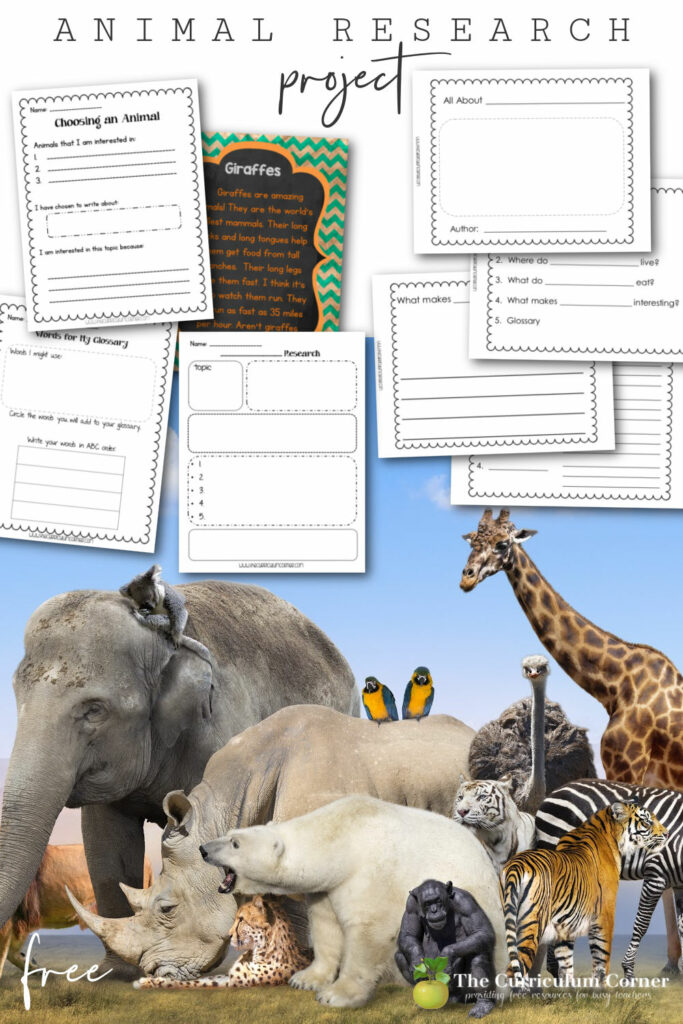

What is Included in the Animal Research Project

The following resources are included in the animal research project :

Teacher’s Guide

The teacher’s guide includes tips and instructions to support you with your lesson planning and delivery.

Parent Letter

The parent communication letter promotes family involvement.

Graphic Organizers

There are graphic organizers for brainstorming a topic, activating schema, taking notes, and drafting writing.

Research Report

There are research report publishing printables including a cover, writing templates, and resource pages.

There is a grading rubric so expectations are clear for students and grading is quick and easy for you.

Research Activities

The research activities include a KWL chart, can have are chart, compare and contrast venn diagram, habitat map, vocabulary pages, illustration page, and life cycle charts.

Animal Flip Book Project

There are animal flip book project printables to give an additional choice of how students can demonstrate their understanding.

Animal Flap Book Project

There is an animal flap book project printables that offers students yet another way to demonstrate their learning.

Animal Research Poster

The animal research poster serves as an additional way to demonstrate student understanding.

Poetry Activities

The resource includes poetry activities to offer students an alternative way to demonstrate their learning.

Digital Versions

There is a digital version of the resource so your students can access this resource in school or at home.

Why Teachers love the Animal Research Project

Teachers love this animal research project because of the following reasons:

- This resource guides students through the research and writing process, so they can confidently work their way through this project.

- It is a great value because it can be used over and over again throughout the school year because the pages can be used to learn about any animal.

- It offers several ways students can demonstrate their learning.

- It includes a ton of resources, so you can pick and choose which ones work best for you and your students.

- It is printable and digital so it can be used for in-class and at-home learning.

This animal research packet is great because it can be used over and over again using absolutely any animal at all. The printables in this packet are ideal to use with your entire class in school, as an at-home learning extension project or as a purposeful, open-ended, independent choice for your students who often finish early and need an enrichment activity that is so much more than “busy work.”

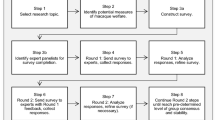

The Research Report Process

This animal research project packet was designed in a manner that allows you to use all of the components when studying any animal. Because the printables can be used over and over, I will often work through the entire researching and writing process with the whole class focusing on one animal together, This allows me to model the procedure and provide them with support as they “get their feet wet” as researchers. Afterwards I then have them work through the process with an animal of choice. You may find it helpful to have them select from a specific category (i.e. ocean animals, rainforest animals, etc) as this will help to streamline the resources you’ll need to obtain.

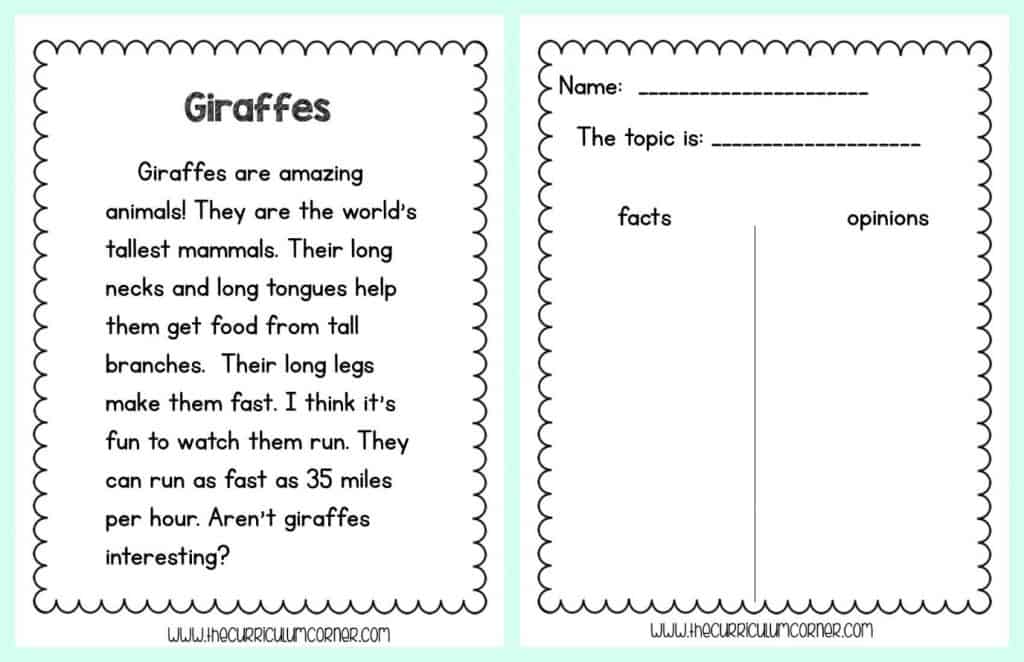

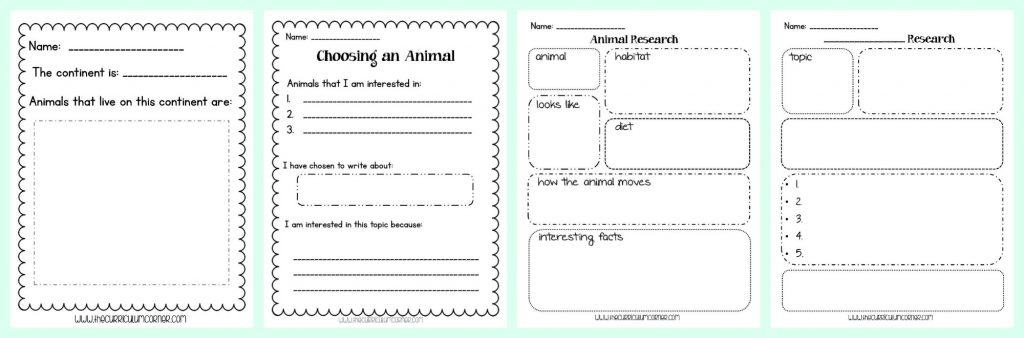

Step 1: Brainstorm a list of animals to research. Select one animal.

During this stage you may want to provide the students with a collection of books and magazines to explore and help them narrow down their choice.

Step 2: Set a purpose and activate schema.

Students share why they selected the animal and tell what they already know about it. Next, they generate a list of things they are wondering about the animal. This will help to guide their research.

Step 3: Send home the family letter.

To save you time, involve families, and communicate what is happening in the classroom, you may want to send home a copy of the family letter. It’s so helpful when they send in additional research materials for the students.

Step 4: Research and take notes.

The two-column notes template is a research-based tool that helps the kids organize their notes. I added bulleted prompts to guide the students in finding specific information within each category. This method has proven to be highly effective with all students, but is especially useful with writers who need extra support.

I have included two versions of the organizers (with and without lines). I print a copy of the organizer for each student. I also copy the lined paper back to back so it is available to students who need more space.

Step 5: Write a draft.

Using the information gathered through the research process, the students next compose drafts. The draft papers were designed to guide the students through their writing by providing prompts in the form of questions. Answering these questions in complete sentences will result in strong paragraphs. It may be helpful to give them only one page at a time instead of a packet as it make the task more manageable.

Step 6: Edit the draft.

Editing can be done in many ways, but it is most effective when a qualified editor sits 1:1 with a student to provides effective feedback to them while editing.

Step 7: Publish.

Print several copies of the publishing pages. I like to have all my students start with the page that has a large space for an illustration, but then let them pick the pages they want to use in the order they prefer after that. I have them complete all the writing first and then add the illustrations.

Finally, have the children design a cover for the report. Add that to the front and add the resources citation page to the back. Use the criteria for success scoring rubric to assign a grade. The rubric was designed using a 20 point total so you can simply multiply their score by 5 to obtain a percentage grade. The end result is a beautiful product that showcases their new learning as well as documents their reading and writing skills.

In closing, we hope you found this animal research project for kids helpful! If you did, then you may also be interested in these posts:

- How to Teach Research Skills to Elementary Students

- 15 Animals in Winter Picture Books for Elementary Teachers

- How to Teach Informative Writing at the Elementary Level

You might also like...

Project Based Learning Activities for Elementary Students

Me on the Map Activities and Printables for Elementary Teachers – 2024

Student-Made Board Games Ideas for Elementary Teachers in 2024

Join the email club.

- CLUTTER-FREE TEACHER CLUB

- FACEBOOK GROUPS

- EMAIL COMMUNITY

- OUR TEACHER STORE

- ALL-ACCESS MEMBERSHIPS

- OUR TPT SHOP

- JODI & COMPANY

- TERMS OF USE

- Privacy Policy

- Committee on Animal Research and Ethics (CARE)

- Animal Research

Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Nonhuman Animals in Research

Download the guidelines (PDF, 86KB)

February 2022

A foundational aspect of the discipline of psychology is teaching about and research on the behavior of nonhuman animals. Studying other animals is critical to understanding basic principles underlying behavior and to advancing the welfare of both human and nonhuman animals. While psychologists must conduct their teaching and research in a manner consonant with relevant laws and regulations, ethical concerns further mandate that psychologists consider the costs and benefits of procedures involving nonhuman animals before proceeding with these activities.

The following guidelines were developed by the American Psychological Association (APA) for use by psychologists working with nonhuman animals. The guidelines are informed by relevant sections of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA, 2017).The acquisition, care, housing, use, and disposition of nonhuman animals in research must comply with applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations, institutional policies, and with international conventions to which the United States is a party. APA members working outside the United States must also follow all applicable laws and regulations of the country in which they conduct research.

It is important to recognize that this document constitutes “guidelines,” which serve a different purpose than “standards.” Standards, unlike guidelines, require mandatory compliance, and may be accompanied by an enforcement mechanism. This document is meant to be aspirational and thereby provides recommendations for the professional conduct of specified activities. These guidelines are not intended to be mandatory, exhaustive, or definitive and should not take precedence over the professional judgment of individuals who have competence in the subject addressed.

Questions about these guidelines should be referred to the APA Committee on Animal Research and Ethics (CARE) via email at [email protected] , by phone at 202-336-6000, or in writing to the American Psychological Association, Science Directorate, Office of Research Ethics, 750 First St., NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242

These guidelines are scheduled to expire 10 years from (the date of adoption by the APA Council of Representatives). After this date users are encouraged to contact the APA Science Directorate to determine whether this document remains in effect.

- Research should be undertaken with a clear scientific purpose. There should be a reasonable expectation that the research will a) increase knowledge of the process underlying the evolution, development, maintenance, alteration, control, or biological significance of behavior; b) determine the replicability and generality of prior research; c) increase understanding of the species under study; or d) provide results that benefit the health or welfare of humans or other animals.

- The scientific purpose of the research should be of sufficient potential significance to justify the use of nonhuman animals. In general, psychologists should act on the assumption that procedures that are likely to produce pain in humans may also do so in other animals, unless there is species-specific evidence of pain or stress to the contrary.

- In proposing a research project, the psychologist should be familiar with the appropriate literature, consider the possibility of nonanimal alternatives, and use procedures that minimize the number of nonhuman animals in research. If nonhuman animals are to be used, the species chosen for the study should be the best suited to answer the question(s) posed.

- Research on nonhuman animals may not be conducted until the protocol has been reviewed and approved by an appropriate animal care committee; typically, an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), to ensure that the procedures are appropriate and abide by the principles for humane experimental techniques embodied by the 3Rs – Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement (Russell & Burch, 1959).

- The researcher(s) should monitor the research and the subjects’ welfare throughout the course of an investigation to ensure continued justification for the research.

- Psychologists should ensure that personnel involved in their research with nonhuman animals be familiar with these guidelines.

- Investigators and personnel should complete all required institutional research trainings for the ethical conduct of such research.

- Research procedures with nonhuman animals should conform to the Animal Welfare Act (7 U.S.C. §2131 et. seq.) and when applicable, the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS, 2015) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Resource Council, 2011), as well as other applicable federal regulations, policies, and guidelines, regarding personnel, supervision, record keeping, and veterinary care.

- As behavior is not only the focus of study of many experiments but also a primary source of information about an animal’s health and well-being, investigators should watch for and recognize deviations from normal, species-typical behaviors as indicators of potential health problems.

- Psychologists should assume it is their responsibility that all individuals who work with nonhuman animals under their supervision receive explicit instruction in experimental methods and in the care, maintenance, and handling of the species being studied. The activities that any individuals may engage in must not exceed their respective competencies, training, and experience in either the laboratory or the field setting

As a scientific and professional organization, APA recognizes the complexities of defining psychological well-being for both human and nonhuman animals. APA does not provide specific guidelines for the maintenance of psychological well-being of research animals, as procedures that are appropriate for a particular species may not be for others. Psychologists who are familiar with the species, relevant literature, federal guidelines, and their institution’s research facility should consider the appropriateness of measures such as social housing and enrichment to maintain or improve psychological well-being of those species.

- The facilities housing laboratory animals should meet or exceed current regulations and guidelines (USDA, 1990, 1991; NIH, 2015) and are required to be inspected twice a year (USDA, 1989; NIH, 2015).

- All procedures carried out on nonhuman animals are to be reviewed by an IACUC to ensure that the procedures are appropriate and humane. The committee must have representation from within the institution and from the local community. In the event that it is not possible to constitute an appropriate IACUC in the psychologist’s own institution, psychologists should seek advice and obtain review from a corresponding committee of a cooperative institution.

- Laboratory animals are to be provided with humane care and healthful conditions during their stay in any facilities of the institution. Responsibilities for the conditions under which animals are kept, both within and outside of the context of active experimentation or teaching, rests with the psychologist under the supervision of the IACUC (where required by federal regulations) and with individuals appointed by the institution to oversee laboratory animal care.

- Laboratory animals not bred in the psychologist’s facility are to be acquired lawfully. The USDA and local ordinances should be determined and followed prior to IACUC protocol submission.

- Psychologists should make every effort to ensure that those responsible for transporting the nonhuman animals to the facility provide adequate food, water, ventilation, and space, and impose no unnecessary stress on the animals (NRC, 2006).

- Nonhuman animals taken from the wild should be trapped in a humane manner and in accordance with applicable federal, state, and local regulations.

- Use of endangered, threatened, or imported nonhuman animals must only be conducted with full attention to required permits and ethical concerns. Information and permit applications may be obtained from the Fish and Wildlife Service website at www.fws.gov .

Consideration for the humane treatment and well-being of the laboratory animal should be incorporated into the design and conduct of all procedures involving such animals, while keeping in mind the primary goal of undertaking the specific procedures of the research project—the acquisition of sound, replicable data. The conduct of all procedures is governed by Guideline I (Justification of Research) above.

- Observational and other noninvasive forms of behavioral studies that involve no aversive stimulation to, or elicit no sign of distress from, the nonhuman animal are acceptable.

- Whenever possible behavioral procedures should be used that minimize discomfort to the nonhuman animal. Psychologists should adjust the parameters of aversive stimulation to the minimal levels compatible with the aims of the research. Consideration should be given to providing the research animals control over the potential aversive stimulation whenever it is consistent with the goals of the research. Whenever reasonable, psychologists are encouraged to first test on themselves the painful stimuli to be used on nonhuman animal subjects.

- Procedures in which the research animal is anesthetized and insensitive to pain throughout the procedure, and is euthanized (AVMA, 2020) before regaining consciousness are generally acceptable.

- Procedures involving more than momentary or slight aversive stimulation, which is not relieved by medication or other acceptable methods, should be undertaken only when the objectives of the research cannot be achieved by other methods.

- Experimental procedures that require prolonged aversive conditions or produce tissue damage or metabolic disturbances require greater justification and surveillance by the psychologist and IACUC. A research animal observed to be in a state of severe distress or chronic pain that cannot be alleviated and is not essential to the purposes of the research should be euthanized immediately (AVMA, 2020).

- Procedures that employ restraint must conform to federal regulations and guidelines.

- Procedures involving the use of paralytic agents without reduction in pain sensation require prudence and humane concern. Use of muscle relaxants or paralytics alone during surgery, without anesthesia, is unacceptable.

- All surgical procedures and anesthetization should be conducted under the direct supervision of a person who is trained and competent in the use of the procedures.

- Unless there is specific justification for acting otherwise, research animals should remain under anesthesia until all surgical procedures are ended.

- Postoperative monitoring and care, which may include the use of analgesics and antibiotics, should be provided to minimize discomfort, prevent infection, and promote recovery from the procedure.

- In general, laboratory animals should not be subjected to successive survival surgical procedures, except as required by the nature of the research, the nature of the specific surgery, or for the well-being of the animal. Multiple surgeries on the same animal must be justified and receive approval from the IACUC.

- To minimize the number of nonhuman animals used, investigators should maximize the amount of data collected from each subject in a manner that is compatible with the goals of the research, sound scientific practice, and the welfare of the animal.

- To ensure their humane treatment and well-being, nonhuman animals reared in the laboratory must not be released into the wild because, in most cases, they cannot survive, or they may survive by disrupting the natural ecology.

- Euthanasia must be accomplished in a humane manner, appropriate for the species and age, and in such a way as to ensure immediate death, and in accordance with procedures outlined in the latest version of the AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association) Guidelines on Euthanasia of Animals (2020).

- Disposal of euthanized laboratory animals must be conducted in accordance with all relevant laws, consistent with health, environmental, and aesthetic concerns, and as approved by the IACUC. No animal shall be discarded until its death is verified.

Field research that carries a risk of materially altering the behavior of nonhuman animals and/or producing damage to sensitive ecosystems is subject to IACUC approval. Field research, if strictly observational, may not require animal care committee approval (USDA, 2000).

- Psychologists conducting field research should disturb their populations as little as possible, while acting consistent with the goals of the research. Every effort should be made to minimize potential harmful effects of the study on the population and on other plant and animal species in the area.

- Research conducted in populated areas must be done with respect for the property and privacy of the area’s inhabitants.

- Such research on endangered species should not be conducted unless IACUC approval has been obtained and all requisite permits are obtained (see section IV.D of this document). Included in this review should be a risk assessment and guidelines for prevention of zoonotic disease transmission (i.e., disease transmission between species, including human to nonhuman and vice versa).

Research on captive wildlife or domesticated animals outside the laboratory setting that materially alters the environment or behavior of the nonhuman animals should be subject to IACUC approval (Ng et al., 2019). This includes settings where the principal subjects of the research are humans, but nonhuman animals are used as part of the study, such as research on the efficacy of animal-assisted interventions (AAI) and research conducted in zoos, animal shelters, and so on. If it is not possible to establish an IACUC at the psychologists’ own institution, investigators should seek advice and obtain review from an IACUC of a cooperative institution.

- Researchers should minimize and mitigate any distress on the nonhuman animal subject caused by its involvement in the study. Qualifications for appropriate handling of animal subjects in AAI settings have been well described by the AVMA (2008). Psychologists studying the use of AAIs should have the expertise to recognize behavioral and/or physiological signs of stress and distress in the species involved in the study. However, when psychologists lack such expertise, they should ensure that the research team includes individuals with the necessary expertise to recognize and intervene to reduce the nonhuman animal subject’s distress. Any study that carries risk of experiencing, or being exposed to the experience of, another organism’s pain, fear, or distress requires greater justification and should be addressed in the IACUC protocol.

- When research is conducted in applied settings, such as hospitals, health clinics, and offices of doctors and mental health professionals, the investigator should understand the risk of, and declare mitigating strategies for, disease transmission between human and nonhuman participants. For example, studies of AAIs in health-care facilities offering mental health services may introduce risks for bi-directional zoonotic transmission of infectious diseases such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Lefebvre, et al., 2008). Investigators studying AAIs in health-care settings should therefore adhere to the guidelines for AAI management offered by the AVMA (2008).

- In all experimental circumstances, investigators should structure into the schedule the basic needs of the nonhuman animals such as food, water, and rest breaks.

Laboratory exercises as well as classroom demonstrations involving live animals are of great value as instructional aids. Psychologists are encouraged to include instruction and discussion of the ethics and values of nonhuman animal research in relevant courses.

- Nonhuman animals may be used for educational purposes only after review by an IACUC or other appropriate institutional committee.

- Consideration should be given to the possibility of using nonanimal alternatives. Procedures that may be justified for research purposes may not be so for educational purposes (e.g., animal models of pain that are used to develop safer analgesics would be in excess of what is needed to merely demonstrate the use of animal models in the study of behavior and cognition).

- All handlers of nonhuman animals in educational settings should adhere to the recommendations outlined above for personnel, housing, and acquisition of subjects. APA has adopted separate guidelines for the use of nonhuman animals in research and teaching at the pre-college level. A copy of the APA Guidelines for the Use of Nonhuman Animals in Behavioral Projects in Schools (K-12) can be obtained via email at [email protected] , by phone at 202-336-6000, or in writing to the American Psychological Association, Science Directorate, Office of Research Ethics, 750 First St., NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242 or downloaded at apa.org/science/leadership/care/animal-guide.pdf .

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2008). Guidelines for animal-assisted interventions in healthcare facilities. American Journal of Infection Control, 36(2), 78-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.09.005

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2020). AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/2020-Euthanasia-Final-1-17-20.pdf

Animal Welfare Act 7 U.S.C. § 2131 et seq. http://awic.nal.usda.gov/nal_display/index.php?info_center=3&tax_level=3&tax_subject=182&topic_id=1118&level3_id=6735

Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. (2011). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (8th ed.). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Lefebvre, S. L., Peregrine, A. S., Golab, G. C., Gumley, N. R., WaltnerToews, D., & Weese, J. S. (2008). A veterinary perspective on the recently published guidelines for animal-assisted interventions in health-care facilities. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association , 233(3), 394-402. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.233.3.394

National Institutes of Health Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. (2015). Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Bethesda, MD: NIH. https://olaw.nih.gov/policies-laws/phs-policy.htm

National Research Council. (2006). Guidelines for the humane transportation of research animals . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ng, Z., Morse, L., Albright, J., Viera, A., & Souza, M. (2019). Describing the use of animals in animal-assisted intervention research. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science , 22(4), 364-376.

Russell W.M.S., & Burch, R. L. (1959). The principles of humane experimental technique. Wheathampstead (UK): Universities Federation for Animal Welfare.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1989). Animal welfare; Final Rules. Federal Register , 54(168), (Aug 31, 1989), 36112-36163.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1990). Guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits; Final Rules. Federal Register , 55(136), (July 16, 1990), 28879- 28884.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1991). Animal welfare; Standards; Part 3, Final Rules. Federal Register , 55(32), (Feb 15, 1991), 6426-6505.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2000). Field study; Definition; Final Rules. Federal Register , 65(27), (Feb 9, 2000), 6312-6314.

U.S. Public Health Service. (2015). Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. https://olaw.nih.gov/sites/default/ files/PHSPolicyLabAnimals.pdf

Additional Resources

Dess, N. K., & Foltin, R. W. (2004). The ethics cascade. In C. K. Akins, S. Panicker, & C. L. Cunningham (Eds.). Laboratory animals in research and teaching: Ethics, care, and methods (pp. 31-39). APA.

National Institutes of Mental Health. (2002). Methods and welfare considerations in behavioral research with animals: Report of a National Institutes of Health Workshop. Morrison, A. R., Evans, H. L., Ator, N. A., & Nakamura, R. K. (Eds.). NIH Publications No. 02-5083. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

National Research Council. (2011). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. (8th ed.). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2003). Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2008). Recognition and alleviation of distress in laboratory animals. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2009). Recognition and alleviation of pain in laboratory animals. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Nonhuman Animals in Research was developed by the American Psychological Association Committee on Animal Research and Ethics in 2020 and 2021. Members on the committee were Rita Colwill, PhD, Juan Dominguez, PhD, Kevin Freeman, PhD, Pamela Hunt, PhD, Agnès Lacreuse, PhD, Peter Pierre, PhD, Tania Roth, PhD, Malini Suchak, PhD, and Sangeeta Panicker, PhD (Staff Liaison). Inquiries about these guidelines should be made to the American Psychological Association, Science Directorate, Office of Research Ethics, 750 First Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002, or via e-mail at [email protected].

Copyright © 2022 by the American Psychological Association. Approved by the APA Council of Representatives, February 2022.

Related Resources

- Some Friendly Advice for Responding to Requests for Information About Animal Research

- Resolution on the Use of Animals in Research, Testing and Education (PDF, 95KB)

Contact Science Directorate

NIH Simplified Peer Review Framework

- Share Marine Biological Laboratory | NIH Simplified Peer Review Framework on Facebook

- Share Marine Biological Laboratory | NIH Simplified Peer Review Framework on Twitter

- Share Marine Biological Laboratory | NIH Simplified Peer Review Framework on LinkedIn

NIH is simplifying peer review for most research project grants (RPGs) for application due dates of January 25, 2025 or later in order to address the complexity of the peer review process and the potential for reputational bias to affect peer review outcomes. Simplified peer review will apply to the following activity codes: R01, R03, R15, R16, R21, R33, R34, R36, R61, RC1, RC2, RC4, RF1, RL1, RL2, U01, U34, U3R, UA5, UC1, UC2, UC4, UF1, UG3, UH2, UH3, UH5, (including the following phased awards: R21/R33, UH2/UH3, UG3/UH3, R61/R33).

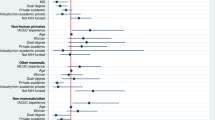

The Simplified Framework for NIH Peer Review Criteria retains the five regulatory criteria ( Significance , Investigators , Innovation , Approach , Environment ) but reorganizes them into three factors — two will receive numerical criterion scores and one will be evaluated for sufficiency. All three factors will be considered in arriving at the Overall Impact score. The reframing of the criteria serves to focus reviewers on three central questions reviewers should be evaluating: How important is the proposed research, how rigorous and feasible are the methods, and whether the investigators and institution have the expertise/resources necessary to carry out the project.

- Factor 1: Importance of the Research ( Significance , Innovation ), scored 1-9

- Factor 2: Rigor and Feasibility ( Approach ), scored 1-9

- Factor 3: Expertise and Resources ( Investigator , Environment ), to be evaluated as either sufficient for the proposed research or not (in which case reviewers must provide an explanation)

The change to having peer reviewers assess the adequacy of investigator expertise and institutional resources as a binary choice is designed to have reviewers evaluate Investigator and Environment with respect to the work proposed. It is intended to reduce the potential for general scientific reputation to have an undue influence.

Five regulatory criteria reorganized into three factors

For due dates before Jan 25, 2025

- Significance - scored

- Investigator(s) - scored

- Innovation - scored

- Approach - scored

- Environment - scored

- Significance, Innovation

- Scored 1 - 9

- Approach ( also includes Inclusion and Clinical Trial (CT) Study Timeline )

- Investigators, Environment

- Evaluated as appropriate or gaps identified; gaps require explanation

- Considered in overall impact; no individual score

Additional Review Criteria Before Jan 25, 2025

- Human Subject (HS) Protections (for HS and CT)

- Vertebrate Animal Protections

- Resubmission/Renewal/Revisions

- Study Timeline (for CT only) *

- Inclusion of Women, Minorities, and Individuals across the lifespan (for HS and CT) *

Revised Additional Review Criteria

- Human Subject Protections (for HS and CT)

Additional Review Considerations Before Jan 25, 2025

- Applications from Foreign Organizations **

- Select Agent Research **

- Resource Sharing Plans **

- Authentication of Key Biological and/or Chemical Resources

- Budget and Period of Support

Additional Changes

Inclusion criteria and coding (considerations of sex/gender, inclusion across the lifespan, race/ethnicity of the study population), study timelines for clinical trial applications, and plans for valid design and analysis of Phase III clinical trials, previously evaluated under Additional Review Criteria, will be integrated within Factor 2 (Rigor and Feasibility). This change will help to emphasize the importance of these criteria in evaluating scientific merit, rather than as issues of policy compliance.

Peer reviewers will no longer evaluate the following Additional Review Considerations: Applications from Foreign Organizations, Select Agents, Resource Sharing Plans. These considerations will instead be administratively reviewed by NIH prior to funding.

Review Criteria Within the Simplified Framework

Overall impact.

Reviewers will provide an overall impact score to reflect their assessment of the likelihood for the project to exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved, in consideration of the following review criteria and additional review criteria (as applicable for the project proposed).

Review Criteria

Reviewers will evaluate Factors 1, 2 and 3 in the determination of scientific merit, and in providing an overall impact score. In addition, Factors 1 and 2 will each receive a separate criterion score. An application does not need to be strong in all categories to be judged likely to have major scientific impact.

| Factor 1. Importance of the Research | |

|

| |

| Factor 2. Rigor and Feasibility | |

|

| |

| Factor 3. Expertise and Resources | |

| | |

Additional Review Criteria

As applicable for the project proposed, reviewers will consider the following additional items while determining scientific and technical merit, but will not give criterion scores for these items, and should consider them in providing an overall impact score.

| Protections for Human Subjects | |

| For research that involves human subjects but does not involve one of the categories of research that are exempt under 45 CFR Part 46, evaluate the justification for involvement of human subjects and the proposed protections from research risk relating to their participation according to the following five review criteria: 1) risk to subjects; 2) adequacy of protection against risks; 3) potential benefits to the subjects and others; 4) importance of the knowledge to be gained; and 5) data and safety monitoring for clinical trials. For research that involves human subjects and meets the criteria for one or more of the categories of research that are exempt under 45 CFR Part 46, evaluate: 1) the justification for the exemption; 2) human subjects involvement and characteristics; and 3) sources of materials. For additional information on review of the Human Subjects section, please refer to the . | |

| Vertebrate Animals | |

| When the proposed research includes Vertebrate Animals, evaluate the involvement of live vertebrate animals according to the following criteria: (1) description of proposed procedures involving animals, including species, strains, ages, sex, and total number to be used; (2) justifications for the use of animals versus alternative models and for the appropriateness of the species proposed; (3) interventions to minimize discomfort, distress, pain and injury; and (4) justification for euthanasia method if NOT consistent with the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. For additional information on review of the Vertebrate Animals section, please refer to the . | |

| Biohazards | |

| When the proposed research includes Biohazards, evaluate whether specific materials or procedures that will be used are significantly hazardous to research personnel and/or the environment, and whether adequate protection is proposed. | |

| Resubmissions | |

| As applicable, evaluate the full application as now presented. | |

| Renewals | |

| As applicable, evaluate the progress made in the last funding period. | |

| Revisions | |

| As applicable, evaluate the appropriateness of the proposed expansion of the scope of the project. | |

Additional Review Considerations As applicable for the project proposed, reviewers will consider each of the following items, but will not give scores for these items, and should not consider them in providing an overall impact score.

| Authentication of Key Biological and/or Chemical Resources | |

| For projects involving key biological and/or chemical resources, evaluate the brief plans proposed for identifying and ensuring the validity of those resources. | |

| Budget and Period of Support | |

| Evaluate whether the budget and the requested period of support are fully justified and reasonable in relation to the proposed research. | |

Animal Studies and School Project Ideas

From Science Fair Project Ideas on Mammals to Experiments About Insects

David Williams / EyeEm / Getty Images

- Cell Biology

- Weather & Climate

- B.A., Biology, Emory University

- A.S., Nursing, Chattahoochee Technical College

Animal research is important for understanding various biological processes in animals , humans included. Scientists study animals in order to learn ways for improving their agricultural health, our methods of wildlife preservation, and even the potential for human companionship. These studies also take advantage of certain animal and human similarities to discover new methods for improving human health.

Learning From Animals

Researching animals to improve human health is possible because animal behavior experiments study disease development and transmission as well as animal viruses . Both of these fields of study help researchers to understand how disease interacts between and within animals.

We can also learn about humans by observing normal and abnormal behavior in non-human animals, or behavioral studies. The following animal project ideas help to introduce animal behavioral study in many different species. Be sure to get permission from your instructor before beginning any animal science projects or behavioral experiments, as some science fairs prohibit these. Select a single species of animal to study from each subset, if not specified, for best results.

Amphibian and Fish Project Ideas

- Does temperature affect tadpole growth?

- Do water pH levels affect tadpole growth?

- Does water temperature affect amphibian respiration?

- Does magnetism affect limb regeneration in newts?

- Does water temperature affect fish color?

- Does the size of a population of fish affect individual growth?

- Does music affect fish activity?

- Does the amount of light affect fish activity?

Bird Project Ideas

- What species of plants attract hummingbirds?

- How does temperature affect bird migration patterns?

- What factors increase egg production?

- Do different bird species prefer different colors of birdseed?

- Do birds prefer to eat in a group or alone?

- Do birds prefer one type of habitat over another?

- How does deforestation affect bird nesting?

- How do birds interact with manmade structures?

- Can birds be taught to sing a certain tune?

Insect Project Ideas

- How does temperature affect the growth of butterflies?

- How does light affect ants?

- Do different colors attract or repel insects?

- How does air pollution affect insects?

- How do insects adapt to pesticides?

- Do magnetic fields affect insects?

- Does soil acidity affect insects?

- Do insects prefer the food of a certain color?

- Do insects behave differently in populations of different sizes?

- What factors cause crickets to chirp more often?

- What substances do mosquitoes find attractive or repellent?

Mammal Project Ideas

- Does light variation affect mammal sleep habits?

- Do cats or dogs have better night vision?

- Does music affect an animal's mood?

- Do bird sounds affect cat behavior?

- Which mammal sense has the greatest effect on short-term memory?

- Does dog saliva have antimicrobial properties?

- Does colored water affect mammal drinking habits?

- What factors influence how many hours a cat sleeps in a day?

Science Experiments and Models

Performing science experiments and constructing models are fun and exciting ways to learn about science and supplement studies. Try making a model of the lungs or a DNA model using candy for these animal experiments.

- Can Animals Sense Natural Disasters?

- 23 Plant Experiment Ideas

- Life and Contributions of Robert Koch, Founder of Modern Bacteriology

- The Fastest Animals on the Planet

- The Best and Worst Fathers in the Animal Kingdom

- 10 of the World's Scariest-Looking Animals

- Slowest Animals on the Planet

- Is Spontaneous Generation Real?

- Animal Viruses

- Why Some Animals Play Dead

- Carnivorous Plants

- Fascinating Animal Facts

- Animals That Mimic Leaves

- Common Animal Questions and Answers

- Biology of Invertebrate Chordates

- What Is Phylogeny?

How to write an animal report

Your teacher wants a written report on the beluga whale . Not to worry. Use these organizational tools from the Nat Geo Kids Almanac so you can stay afloat while writing a report.

STEPS TO SUCCESS:

Your report will follow the format of a descriptive or expository essay and should consist of a main idea, followed by supporting details and a conclusion. Use this basic structure for each paragraph as well as the whole report, and you’ll be on the right track.

Introduction

State your main idea .

The beluga whale is a common and important species of whale.