Introduction

CDHE Nomination

AUCC Requirements

Course Description

Sample Policy Statements

Syllabus Sequencing Strategies

Sample Daily Syllabi

Lesson Plans

Reading Selection Recommendations

Assignments

Response Papers and Discussion Forums

Presentations

Discusssion, Group, WTL Questions

Variations, Misc.

Curbing Plagiarism

Additional Teaching & Course Design Resources

Guide Contributors

Presentation Assignment Examples

Presentations enable students to practice their verbal communication skills. Students ‘become the professional' by sharing a project, lesson plan, interpretation, etc. with the class. Some instructors schedule presentations the last few weeks of the semester. Others spread them throughout the semester.

Many instructors prefer collaborative presentations, which consist of groups sharing responsibilities. From experience with groups, many instructors advise assigning individuals within groups specific duties or a confidential and brief evaluation paper explaining the group's conduct and struggles to allow students to comment on distribution of the workload and attempts at communicating with other group members. Group presentations make a strong alternative to a traditional final exam, and it is less grading for the instructor.

- Presentation Assignment Example

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

How to Structure your Presentation, with Examples

August 3, 2018 - Dom Barnard

For many people the thought of delivering a presentation is a daunting task and brings about a great deal of nerves . However, if you take some time to understand how effective presentations are structured and then apply this structure to your own presentation, you’ll appear much more confident and relaxed.

Here is our complete guide for structuring your presentation, with examples at the end of the article to demonstrate these points.

Why is structuring a presentation so important?

If you’ve ever sat through a great presentation, you’ll have left feeling either inspired or informed on a given topic. This isn’t because the speaker was the most knowledgeable or motivating person in the world. Instead, it’s because they know how to structure presentations – they have crafted their message in a logical and simple way that has allowed the audience can keep up with them and take away key messages.

Research has supported this, with studies showing that audiences retain structured information 40% more accurately than unstructured information.

In fact, not only is structuring a presentation important for the benefit of the audience’s understanding, it’s also important for you as the speaker. A good structure helps you remain calm, stay on topic, and avoid any awkward silences.

What will affect your presentation structure?

Generally speaking, there is a natural flow that any decent presentation will follow which we will go into shortly. However, you should be aware that all presentation structures will be different in their own unique way and this will be due to a number of factors, including:

- Whether you need to deliver any demonstrations

- How knowledgeable the audience already is on the given subject

- How much interaction you want from the audience

- Any time constraints there are for your talk

- What setting you are in

- Your ability to use any kinds of visual assistance

Before choosing the presentation’s structure answer these questions first:

- What is your presentation’s aim?

- Who are the audience?

- What are the main points your audience should remember afterwards?

When reading the points below, think critically about what things may cause your presentation structure to be slightly different. You can add in certain elements and add more focus to certain moments if that works better for your speech.

What is the typical presentation structure?

This is the usual flow of a presentation, which covers all the vital sections and is a good starting point for yours. It allows your audience to easily follow along and sets out a solid structure you can add your content to.

1. Greet the audience and introduce yourself

Before you start delivering your talk, introduce yourself to the audience and clarify who you are and your relevant expertise. This does not need to be long or incredibly detailed, but will help build an immediate relationship between you and the audience. It gives you the chance to briefly clarify your expertise and why you are worth listening to. This will help establish your ethos so the audience will trust you more and think you’re credible.

Read our tips on How to Start a Presentation Effectively

2. Introduction

In the introduction you need to explain the subject and purpose of your presentation whilst gaining the audience’s interest and confidence. It’s sometimes helpful to think of your introduction as funnel-shaped to help filter down your topic:

- Introduce your general topic

- Explain your topic area

- State the issues/challenges in this area you will be exploring

- State your presentation’s purpose – this is the basis of your presentation so ensure that you provide a statement explaining how the topic will be treated, for example, “I will argue that…” or maybe you will “compare”, “analyse”, “evaluate”, “describe” etc.

- Provide a statement of what you’re hoping the outcome of the presentation will be, for example, “I’m hoping this will be provide you with…”

- Show a preview of the organisation of your presentation

In this section also explain:

- The length of the talk.

- Signal whether you want audience interaction – some presenters prefer the audience to ask questions throughout whereas others allocate a specific section for this.

- If it applies, inform the audience whether to take notes or whether you will be providing handouts.

The way you structure your introduction can depend on the amount of time you have been given to present: a sales pitch may consist of a quick presentation so you may begin with your conclusion and then provide the evidence. Conversely, a speaker presenting their idea for change in the world would be better suited to start with the evidence and then conclude what this means for the audience.

Keep in mind that the main aim of the introduction is to grab the audience’s attention and connect with them.

3. The main body of your talk

The main body of your talk needs to meet the promises you made in the introduction. Depending on the nature of your presentation, clearly segment the different topics you will be discussing, and then work your way through them one at a time – it’s important for everything to be organised logically for the audience to fully understand. There are many different ways to organise your main points, such as, by priority, theme, chronologically etc.

- Main points should be addressed one by one with supporting evidence and examples.

- Before moving on to the next point you should provide a mini-summary.

- Links should be clearly stated between ideas and you must make it clear when you’re moving onto the next point.

- Allow time for people to take relevant notes and stick to the topics you have prepared beforehand rather than straying too far off topic.

When planning your presentation write a list of main points you want to make and ask yourself “What I am telling the audience? What should they understand from this?” refining your answers this way will help you produce clear messages.

4. Conclusion

In presentations the conclusion is frequently underdeveloped and lacks purpose which is a shame as it’s the best place to reinforce your messages. Typically, your presentation has a specific goal – that could be to convert a number of the audience members into customers, lead to a certain number of enquiries to make people knowledgeable on specific key points, or to motivate them towards a shared goal.

Regardless of what that goal is, be sure to summarise your main points and their implications. This clarifies the overall purpose of your talk and reinforces your reason for being there.

Follow these steps:

- Signal that it’s nearly the end of your presentation, for example, “As we wrap up/as we wind down the talk…”

- Restate the topic and purpose of your presentation – “In this speech I wanted to compare…”

- Summarise the main points, including their implications and conclusions

- Indicate what is next/a call to action/a thought-provoking takeaway

- Move on to the last section

5. Thank the audience and invite questions

Conclude your talk by thanking the audience for their time and invite them to ask any questions they may have. As mentioned earlier, personal circumstances will affect the structure of your presentation.

Many presenters prefer to make the Q&A session the key part of their talk and try to speed through the main body of the presentation. This is totally fine, but it is still best to focus on delivering some sort of initial presentation to set the tone and topics for discussion in the Q&A.

Other common presentation structures

The above was a description of a basic presentation, here are some more specific presentation layouts:

Demonstration

Use the demonstration structure when you have something useful to show. This is usually used when you want to show how a product works. Steve Jobs frequently used this technique in his presentations.

- Explain why the product is valuable.

- Describe why the product is necessary.

- Explain what problems it can solve for the audience.

- Demonstrate the product to support what you’ve been saying.

- Make suggestions of other things it can do to make the audience curious.

Problem-solution

This structure is particularly useful in persuading the audience.

- Briefly frame the issue.

- Go into the issue in detail showing why it ‘s such a problem. Use logos and pathos for this – the logical and emotional appeals.

- Provide the solution and explain why this would also help the audience.

- Call to action – something you want the audience to do which is straightforward and pertinent to the solution.

Storytelling

As well as incorporating stories in your presentation , you can organise your whole presentation as a story. There are lots of different type of story structures you can use – a popular choice is the monomyth – the hero’s journey. In a monomyth, a hero goes on a difficult journey or takes on a challenge – they move from the familiar into the unknown. After facing obstacles and ultimately succeeding the hero returns home, transformed and with newfound wisdom.

Storytelling for Business Success webinar , where well-know storyteller Javier Bernad shares strategies for crafting compelling narratives.

Another popular choice for using a story to structure your presentation is in media ras (in the middle of thing). In this type of story you launch right into the action by providing a snippet/teaser of what’s happening and then you start explaining the events that led to that event. This is engaging because you’re starting your story at the most exciting part which will make the audience curious – they’ll want to know how you got there.

- Great storytelling: Examples from Alibaba Founder, Jack Ma

Remaining method

The remaining method structure is good for situations where you’re presenting your perspective on a controversial topic which has split people’s opinions.

- Go into the issue in detail showing why it’s such a problem – use logos and pathos.

- Rebut your opponents’ solutions – explain why their solutions could be useful because the audience will see this as fair and will therefore think you’re trustworthy, and then explain why you think these solutions are not valid.

- After you’ve presented all the alternatives provide your solution, the remaining solution. This is very persuasive because it looks like the winning idea, especially with the audience believing that you’re fair and trustworthy.

Transitions

When delivering presentations it’s important for your words and ideas to flow so your audience can understand how everything links together and why it’s all relevant. This can be done using speech transitions which are words and phrases that allow you to smoothly move from one point to another so that your speech flows and your presentation is unified.

Transitions can be one word, a phrase or a full sentence – there are many different forms, here are some examples:

Moving from the introduction to the first point

Signify to the audience that you will now begin discussing the first main point:

- Now that you’re aware of the overview, let’s begin with…

- First, let’s begin with…

- I will first cover…

- My first point covers…

- To get started, let’s look at…

Shifting between similar points

Move from one point to a similar one:

- In the same way…

- Likewise…

- Equally…

- This is similar to…

- Similarly…

Internal summaries

Internal summarising consists of summarising before moving on to the next point. You must inform the audience:

- What part of the presentation you covered – “In the first part of this speech we’ve covered…”

- What the key points were – “Precisely how…”

- How this links in with the overall presentation – “So that’s the context…”

- What you’re moving on to – “Now I’d like to move on to the second part of presentation which looks at…”

Physical movement

You can move your body and your standing location when you transition to another point. The audience find it easier to follow your presentation and movement will increase their interest.

A common technique for incorporating movement into your presentation is to:

- Start your introduction by standing in the centre of the stage.

- For your first point you stand on the left side of the stage.

- You discuss your second point from the centre again.

- You stand on the right side of the stage for your third point.

- The conclusion occurs in the centre.

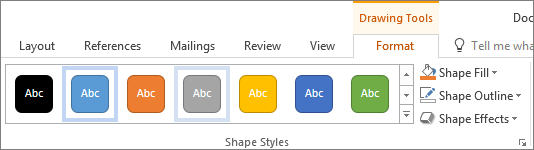

Key slides for your presentation

Slides are a useful tool for most presentations: they can greatly assist in the delivery of your message and help the audience follow along with what you are saying. Key slides include:

- An intro slide outlining your ideas

- A summary slide with core points to remember

- High quality image slides to supplement what you are saying

There are some presenters who choose not to use slides at all, though this is more of a rarity. Slides can be a powerful tool if used properly, but the problem is that many fail to do just that. Here are some golden rules to follow when using slides in a presentation:

- Don’t over fill them – your slides are there to assist your speech, rather than be the focal point. They should have as little information as possible, to avoid distracting people from your talk.

- A picture says a thousand words – instead of filling a slide with text, instead, focus on one or two images or diagrams to help support and explain the point you are discussing at that time.

- Make them readable – depending on the size of your audience, some may not be able to see small text or images, so make everything large enough to fill the space.

- Don’t rush through slides – give the audience enough time to digest each slide.

Guy Kawasaki, an entrepreneur and author, suggests that slideshows should follow a 10-20-30 rule :

- There should be a maximum of 10 slides – people rarely remember more than one concept afterwards so there’s no point overwhelming them with unnecessary information.

- The presentation should last no longer than 20 minutes as this will leave time for questions and discussion.

- The font size should be a minimum of 30pt because the audience reads faster than you talk so less information on the slides means that there is less chance of the audience being distracted.

Here are some additional resources for slide design:

- 7 design tips for effective, beautiful PowerPoint presentations

- 11 design tips for beautiful presentations

- 10 tips on how to make slides that communicate your idea

Group Presentations

Group presentations are structured in the same way as presentations with one speaker but usually require more rehearsal and practices. Clean transitioning between speakers is very important in producing a presentation that flows well. One way of doing this consists of:

- Briefly recap on what you covered in your section: “So that was a brief introduction on what health anxiety is and how it can affect somebody”

- Introduce the next speaker in the team and explain what they will discuss: “Now Elnaz will talk about the prevalence of health anxiety.”

- Then end by looking at the next speaker, gesturing towards them and saying their name: “Elnaz”.

- The next speaker should acknowledge this with a quick: “Thank you Joe.”

From this example you can see how the different sections of the presentations link which makes it easier for the audience to follow and remain engaged.

Example of great presentation structure and delivery

Having examples of great presentations will help inspire your own structures, here are a few such examples, each unique and inspiring in their own way.

How Google Works – by Eric Schmidt

This presentation by ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt demonstrates some of the most important lessons he and his team have learnt with regards to working with some of the most talented individuals they hired. The simplistic yet cohesive style of all of the slides is something to be appreciated. They are relatively straightforward, yet add power and clarity to the narrative of the presentation.

Start with why – by Simon Sinek

Since being released in 2009, this presentation has been viewed almost four million times all around the world. The message itself is very powerful, however, it’s not an idea that hasn’t been heard before. What makes this presentation so powerful is the simple message he is getting across, and the straightforward and understandable manner in which he delivers it. Also note that he doesn’t use any slides, just a whiteboard where he creates a simple diagram of his opinion.

The Wisdom of a Third Grade Dropout – by Rick Rigsby

Here’s an example of a presentation given by a relatively unknown individual looking to inspire the next generation of graduates. Rick’s presentation is unique in many ways compared to the two above. Notably, he uses no visual prompts and includes a great deal of humour.

However, what is similar is the structure he uses. He first introduces his message that the wisest man he knew was a third-grade dropout. He then proceeds to deliver his main body of argument, and in the end, concludes with his message. This powerful speech keeps the viewer engaged throughout, through a mixture of heart-warming sentiment, powerful life advice and engaging humour.

As you can see from the examples above, and as it has been expressed throughout, a great presentation structure means analysing the core message of your presentation. Decide on a key message you want to impart the audience with, and then craft an engaging way of delivering it.

By preparing a solid structure, and practising your talk beforehand, you can walk into the presentation with confidence and deliver a meaningful message to an interested audience.

It’s important for a presentation to be well-structured so it can have the most impact on your audience. An unstructured presentation can be difficult to follow and even frustrating to listen to. The heart of your speech are your main points supported by evidence and your transitions should assist the movement between points and clarify how everything is linked.

Research suggests that the audience remember the first and last things you say so your introduction and conclusion are vital for reinforcing your points. Essentially, ensure you spend the time structuring your presentation and addressing all of the sections.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11 Presentation Skills

11.2 Planning the Presentation

To think about a strategy for your presentation, you must move from thinking only about your self to how you will engage with the world outside of you, which, of course, includes your audience and environment.

This section focuses on helping you prepare a presentation strategy by selecting an appropriate format , prepare an audience analysis, ensure your style reflects your authentic personality and strengths, and that the tone is appropriate for the occasion.

Then, after you’ve selected the appropriate channel, you will begin drafting your presentation, first by considering the general and specific purposes of your presentation and using an outline to map your ideas and strategy.

You’ll also learn to consider whether to incorporate backchannels or other technology into your presentation, and, finally, you will begin to think about how to develop presentation aids that will support your topic and approach.

At the end of this chapter you should be armed with a solid strategy for approaching your presentation in a way that is authentically you, balanced with knowing what’s in it for your audience while making the most of the environment.

Preparing a Presentation Strategy

Incorporating fast.

You can use the acronym FAST to develop your message according to the elements of format, audience, style, and tone . When you are working on a presentation, much like in your writing, you will rely on FAST to help you make choices.

- F ormat – What type of document will you use? What are the elements of that document type?

- A udience – Who will receive your message? What are their expectations? What’s in it for them?

- S tyle – What personality does your writing have? Consider issues like word choice, sentence length and punctuation.

- T one – How do you want your audience to feel about your message? Is your message formal or informal? Positive or negative? Polite? Direct or indirect?

There is a FAST Form template to fill out.

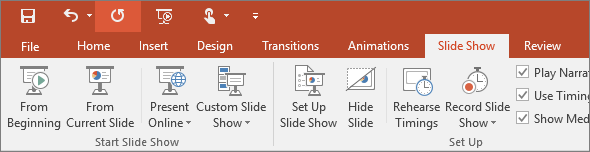

First, you’ll need to think about the format of your presentation. This is a choice between presentation types. In your professional life you’ll encounter the verbal communication channels in the following table. The purpose column labels each channel with a purpose (I=Inform, P=Persuade, or E=Entertain) depending on that channel’s most likely purpose.

| Channel | Direction | Level of Formality | Interaction | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech | One to many | Formal | Low One-sided | I, P, E |

| Presentation | One or few to many | Formal | Variable Often includes Q&A | I, P, E |

| Panel | Few to many | Formal | High Q&A-based | I, P |

| Meeting | Group | Informal | High | I, P |

| Teleconference | Group | Informal | High | I, P |

| Workshop | One to many | Informal | High Collaborative | I (Educate) |

| Webinar | One to many | Formal | Low | I |

| Podcast | One to many | Formal | Low Recorded | I, P, E |

There are some other considerations to make when you are selecting a format . For example, the number of speakers may influence the format you choose. Panels and presentations may have more than one speaker. In meetings and teleconferences, multiple people will converse. In a workshop setting, one person will usually lead the event, but there is often a high level of collaboration between participants.

The location of participants will also influence your decision. For example, if participants cannot all be in the same room, you might choose a teleconference or webinar . If asynchronous delivery (participants access the presentation at different times) is important, you might record a podcast . When choosing a technology-reliant channel, such as a teleconference or webinar, be sure to test your equipment and make sure each participant has access to any materials they need before you begin.

When your presentation is for a course assignment, often these issues are specified for you in the assignment. But if they aren’t, you can consider the best format for your topic, content, and audience. Once you have chosen a format, make sure your message is right for your audience. You’ll need to think about issues such as the following:

- What expectations will the audience have?

- What is the context of your communication?

- What does the audience already know about the topic?

- How is the audience likely to react to you and your message?

AUDIENCE Analysis Form

- Analyze – Who will receive your message?

- Understand – What do they already know or understand about your intended message?

- Demographics – What is their age, gender, education level, occupation, position?

- Interest – What is their level of interest/investment in your message? (What’s in it for them?)

- Environment – What setting/reality is your audience immersed in and what is your relationship to it? What is their likely attitude to your message? Have you taken cultural differences into consideration?

- Need – What information does your audience need? How will they use the information?

- Customize – How do you adjust your message to better suit your audience?

- Expectations – What does your audience expect from you or your message?

Here is an Audience Analysis Form template to fill out.

Next, you’ll consider the style of your presentation. Some of the things you discovered about yourself as a speaker in the self-awareness exercises earlier will influence your presentation style. Perhaps you prefer to present formally, limiting your interaction with the audience, or perhaps you prefer a more conversational, informal style, where discussion is a key element. You may prefer to cover serious subjects, or perhaps you enjoy delivering humorous speeches. Style is all about your personality!

Finally, you’ll select a tone for your presentation. Your voice, body language, level of self-confidence, dress, and use of space all contribute to the mood that your message takes on. Consider how you want your audience to feel when they leave your presentation, and approach it with that mood in mind.

Presentation Purpose

Your presentation will have a general and specific purpose. Your general purpose may be to inform, persuade, or entertain. It’s likely that any speech you develop will have a combination of these goals. Most presentations have a little bit of entertainment value, even if they are primarily attempting to inform or persuade. For example, the speaker might begin with a joke or dramatic opening, even though their speech is primarily informational.

Your specific purpose addresses what you are going to inform, persuade, or entertain your audience with—the main topic of your speech. Each example below includes two pieces of information: first, the general purpose; second, the specific purpose.

To inform the audience about my favourite car, the Ford Mustang.

To persuade the audience that global warming is a threat to the environment.

Aim to speak for 90 percent of your allotted time so that you have time to answer audience questions at the end (assuming you have allowed for this). If audience questions are not expected, aim for 95 percent. Do not go overtime—audience members may need to be somewhere else immediately following your presentation, and you will feel uncomfortable if they begin to pack up and leave while you are still speaking. Conversely, you don’t want to finish too early, as they may feel as if they didn’t get their “money’s worth.”

To assess the timing of your speech as you prepare, you can

- Set a timer while you do a few practice runs, and take an average.

- Run your speech text through an online speech timer.

- Estimate based on the number of words (the average person speaks at about 120 words per minute).

You can improve your chances of hitting your time target when you deliver your speech, by marking your notes with an estimated time at certain points. For example, if your speech starts at 2 p.m., you might mark 2:05 at the start of your notes for the body section, so that you can quickly glance at the clock and make sure you are on target. If you get there more quickly, consciously try to pause more often or speak more slowly, or speed up a little if you are pressed for time. If you have to adjust your timing as you are delivering the speech, do so gradually. It will be jarring to the audience if you start out speaking at a moderate pace, then suddenly realize you are going to run out of time and switch to rapid-fire delivery!

Incorporating Backchannels

Have you ever been to a conference where speakers asked for audience questions via social media? Perhaps one of your teachers at school has used Twitter for student comments and questions, or has asked you to vote on an issue through an online poll. Technology has given speakers new ways to engage with an audience in real time, and these can be particularly useful when it isn’t practical for the audience to share their thoughts verbally—for example, when the audience is very large, or when they are not all in the same location.

These secondary or additional means of interacting with your audience are called backchannels , and you might decide to incorporate one into your presentation, depending on your aims. They can be helpful for engaging more introverted members of the audience who may not be comfortable speaking out verbally in a large group. Using publicly accessible social networks, such as a Facebook Page or Twitter feed, can also help to spread your message to a wider audience, as audience members share posts related to your speech with their networks. Because of this, backchannels are often incorporated into conferences; they are helpful in marketing the conference and its speakers both during and after the event.

There are some caveats involved in using these backchannels, though. If, for example, you ask your audience to submit their questions via Twitter, you’ll need to choose a hashtag for them to append to the messages so that you can easily find them. You’ll also need to have an assistant who will sort and choose the audience questions for you to answer. It is much too distracting for the speaker to do this on their own during the presentation. You could, however, respond to audience questions and comments after the presentation via social media, gaining the benefits of both written and verbal channels to spread your message.

Developing the Content

Creating an outline.

As with any type of messaging, it helps if you create an outline of your speech or presentation before you create it fully. This ensures that each element is in the right place and gives you a place to start to avoid the dreaded blank page. Here is an outline template that you can adapt for your purpose. Replace the placeholders in the content column with your ideas or points, then make some notes in the verbal and visual delivery column about how you will support or emphasize these points using the techniques we’ve discussed. This outline is appropriate for a presentation meant to inform or persuade. You’ll note this is similar to an outline for a research paper.

Introduction

The beginning of your speech needs an attention-grabber to get your audience interested right away. Choose your attention-grabbing device based on what works best for your topic. Your entire introduction should be only around 10 to 15 percent of your total speech, so be sure to keep this section short. Here are some devices that you could try for attention-grabbers:

| Attention Grabber | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Subject statement | A subject statement is to the point, but not the most interesting choice. | We are surrounded by statistical information in today’s world, so understanding statistics is becoming paramount to citizenship in the twenty-first century. |

| Audience reference | An audience reference highlights something common to the audience that will make them interested in the topic. | As human resource professionals, you and I know the importance of talent management. In today’s competitive world, we need to invest in getting and keeping the best talent for our organizations to succeed. |

| Quotation | Share wise words of another person. You can find quotations online that cover just about any topic. | Oliver Goldsmith, a sixteenth-century writer, poet, and physician, once noted that “the true use of speech is not so much to express our wants as to conceal them.” |

| Current event | Refer to a current event in the news that demonstrates the relevance of your topic to the audience. | On January 10, 2007, Scott Anthony Gomez Jr. and a fellow inmate escaped from a Pueblo, Colorado, jail. During their escape the duo attempted to rappel from the roof of the jail using a makeshift ladder of bed sheets. During Gomez’s attempt to scale the building, he slipped, fell 40 feet, and injured his back. After being quickly apprehended, Gomez filed a lawsuit against the jail for making it too easy for him to escape. |

| Historical event | Compare or contrast your topic with an occasion in history. | During the 1960s and ’70s, the United States intervened in the civil strife between North and South Vietnam. The result was a long-running war of attrition in which many American lives were lost and the country of Vietnam suffered tremendous damage and destruction. We saw a similar war waged in Iraq. American lives were lost, and stability has not yet returned to the region. |

| Anecdote, parable, or fable | An anecdote is a brief account or story of an interesting or humorous event, while a parable or fable is a symbolic tale designed to teach a life lesson. | In July 2009, a high school girl named Alexa Longueira was walking along a main boulevard near her home on Staten Island, New York, typing in a message on her cell phone. Not paying attention to the world around her, she took a step and fell right into an open manhole (Witney, 2009). The ancient Greek writer Aesop told a fable about a boy who put his hand into a pitcher of filberts. The boy grabbed as many of the delicious nuts as he possibly could. But when he tried to pull them out, his hand wouldn’t fit through the neck of the pitcher because he was grasping so many filberts. Instead of dropping some of them so that his hand would fit, he burst into tears and cried about his predicament. The moral of the story? “Don’t try to do too much at once” (Aesop, 1881). |

| Surprising statement | A strange fact or statistic related to your topic that startles your audience. | |

| Question | You could ask either a question that asks for a response from your audience, or a rhetorical question, which does not need a response but is designed to get them thinking about the topic. | |

| Humour | A joke or humorous quotation can work well, but to use humour you need to be sure that your audience will find the comment funny. You run the risk of insulting members of the audience, or leaving them puzzled if they don’t get the joke, so test it out on someone else first! | “The only thing that stops God from sending another flood is that the first one was useless.” —Nicolas Chamfort, sixteenth-century French author |

| Personal reference | Refer to a story about yourself that is relevant to the topic. | In the fall of 2008, I decided that it was time that I took my life into my own hands. After suffering for years with the disease of obesity, I decided to take a leap of faith and get a gastric bypass in an attempt to finally beat the disease. |

| Occasion reference | This device is only relevant if your speech is occasion-specific, for example, a toast at a wedding, a ceremonial speech, or a graduation commencement. | Today we are here to celebrate the wedding of two wonderful people. |

The above provides several options for attention-grabbers, but remember you likely only need one. After the attention-getter comes the rest of your introduction. It needs to do the following:

- Capture the audience’s interest

- State the purpose of your speech

- Establish credibility

- Give the audience a reason to listen

- Signpost the main ideas

For post-secondary students, your class presentation is likely to fulfill an assignment such as presenting the findings of a research paper or summarizing a class unit. It is important to realize that your presentation does not need to include all of your information. In fact, it is unwise (and very boring) to read your whole research paper in your presentation. Choose the important and interesting things to highlight in your presentation.

Your audience will think to themselves, Why should I listen to this speech? What’s in it for me? One of the best things you can do as a speaker is to answer these questions early in your body, if you haven’t already done so in your introduction. This will serve to gain their support early and will fill in the blanks of who, what, when, where, why, and how in their minds.

You can use the outline to organize your topics. Gather the general ideas you want to convey. There is often more than one way to organize a speech. Some of your points could be left out, and others developed more fully, depending on the purpose and audience. You will refine this information until you have the number of main points you need. Ensure that they are distinct, and balance the content of your speech so that you spend roughly the same amount of time addressing each. Make sure to use parallel structure to make sure each of your main points is phrased in the same way. The last thing to do when working on your body is to make sure your points are in a logical order, so that your ideas flow naturally from one to the next.

Practical Examples

Depending on the topic, it is often useful to use practical examples to demonstrate your point. If your presentation is about the impacts of global warming, for example, it would be wise to mention some familiar natural disasters that are linked to global warming. If your presentation is about how to do a good presentation, you could mention several specific examples of things that could go wrong if the presenter isn’t organized. These practical examples help the audience relate the content to real life and understand it better.

Using Humour

If appropriate, using humour in the presentation is often a welcome diversion from a serious topic. It lightens the mood, often helps relieve anxiety, and creates engagement with the audience. It needs to be used sparingly and tastefully. Humour is often an area that can offend, so run your ideas past others before incorporating it into your presentation.

Presentation Conclusion

You will want to conclude your presentation on a high note. You’ll need to keep your energy up until the very end of your speech. In your conclusion, you will want to reiterate the main points of your presentation. This will help to tie together the concepts for your audience. It will also help them realize you are wrapping it up. It is often a good idea to leave them with a final thought or call to action, depending on the general purpose of your message. Lastly, remember to be clear that it is the end of your presentation. Don’t end it by throwing one last piece of information or it will seem like you’ve left it hanging. End with a general statement about the topic or a thought to ponder. Ending with “thank you” also lets them know it’s the end. Once you have completed your question, you can invite questions and comments from the audience if appropriate.

Key Takeaways

- FAST (Format, Audience, Style, Tone) is a useful approach for ensuring your presentation strategy is comprehensive.

- Doing an audience analysis using the AUDIENCE tool helps us to better understand what’s in it for them.

- Using an outline is a good way to stay organized while you write your speech.

- Your presentation intro should include an appropriate attention grabber in the introduction. There are several types to choose from.

- The body of your presentation should be organized and structured appropriately, presenting the main ideas and their related specifics in an orderly manner.

- The conclusion should include a summary of the main points along with a residual message or call to action.

- Always aim to conclude on a high note.

In this section you considered the importance of FAST and AUDIENCE tools in helping to lay out a strategy that incorporates your own understanding with the needs of the audience. You learned about how to use an outline to stay organized and keep track of your ideas, as well as general and specific purposes. You learned the importance of sustaining your audience’s attention throughout the presentation with key approaches you can take as you write your introduction, body, and conclusion. You should now be prepared to take your strategy to the next level by ensuring you next consider whether and how to incorporate high-quality presentation aids.

Exercise: Check Your Understanding – Presentation Planning

- To entertain

- To persuade

- To avoid running out of time and having to cut short important content

- To make sure that the rate at which you speak gives the desired effect

- To make sure you have correctly timed technological elements such as slides

- All of the above

- Only (a) & (c)

- Entertain, persuade, and debate

- Persuade, inform, and perpetuate

- Celebrate, perpetuate, and inform

- Inform, persuade, and entertain

- Deliberative, epideictic, and forensic

- Have an extra laptop available so you can keep track of comments as they come in

- At natural breaks in the presentation, minimize your other visual aids and display the comment feed

- Wait until after the presentation to view the comments and reply to questions via the backchannel

- Select a person in the room to monitor the backchannel and cue you into questions

- Establish your credibility

- Explain the relevance of your topic to your audience

- Lay out a simple map of your speech

- To help the audience remember the primary message from the speech

- To summarize the main points of the speech

- To lead into a Q&A session

- Only (a) & (b)

- Pretend to sneeze into your hands several times as you walk up to a student. Then wipe the back of that hand across your nose before extending it to the student for a handshake.

- Ask them “How many of you like catching colds?”

- Tell a story about the time you got to skip school for a week because you caught a bad cold.

- Provide data that show 2 percent of all colds progress to life-threatening conditions like pneumonia or pleurisy.

- Your outline should include all the details of your presentation.

- Your outline should show your plan for an introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Your outline should show that you adequately supported your main points.

- Your outline should show that you have presented similar ideas in parallel ways.

- Identify the main points

- Get the audience’s attention

- Make the topic important to the audience

- Present the speech’s thesis

Aesop (1881). Aesop’s fables . New York, NY: Wm. L. Allison. Retrieved from http://www.litscape.com/author/Aesop/The_Boy_and_the_Filberts.html

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology [Online version]. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Ebbinghaus/index.htm

Whitney, L. (2009, July 13). Don’t text while walking? Girl learns the hard way . CNET News Wireless . Retrieved from http://news.cnet.com/8301-1035_3-10285466-94.html

Text Attributions

This chapter is an adaptation of the following chapter:

- “ Presenting in a Professional Context ” in Professional Communication OER by Olds College OER Development Team. Adapted by Mary Shier. CC BY . (The Olds College chapter itself is a remix that incorporates content from multiple sources. For a full list, refer to the Olds College chapter.)

Student Success Copyright © 2020 by Mary Shier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Presentations

Rhian Morgan

Introduction

Presentations are a common form of assessment at university. At some point during your program, you will very likely be required to deliver information via a presentation. This chapter provides you with the foundational knowledge, skills, and tips to prepare and present your work effectively.

Types of Presentations

There are various types of presentations you may come across at university. Being aware of each type of presentation can be beneficial for you as a student. At university, most presentations will either be formal, informal, or group presentations.

- Formal presentations are instances where you are required to prepare in advance to deliver a talk. This can be for an assessment piece, interview, conference, or project. In a formal presentation, you are likely to use some form of visual tool to deliver the information.

- Informal presentations are occasions where you may be required to deliver an impromptu talk. This may occur in tutorials, meetings, or gatherings.

- Group presentations are normally formal and require you to work collaboratively with your peers in delivering information. Similar to formal presentations, group presentations require prior planning and practice. Group presentations are normally done for an assessment piece, projects, or conferences. Some visual tools may be used.

Regardless of the type of presentation you are asked to do, understanding the standard forms of presentations will assist with your preparation.

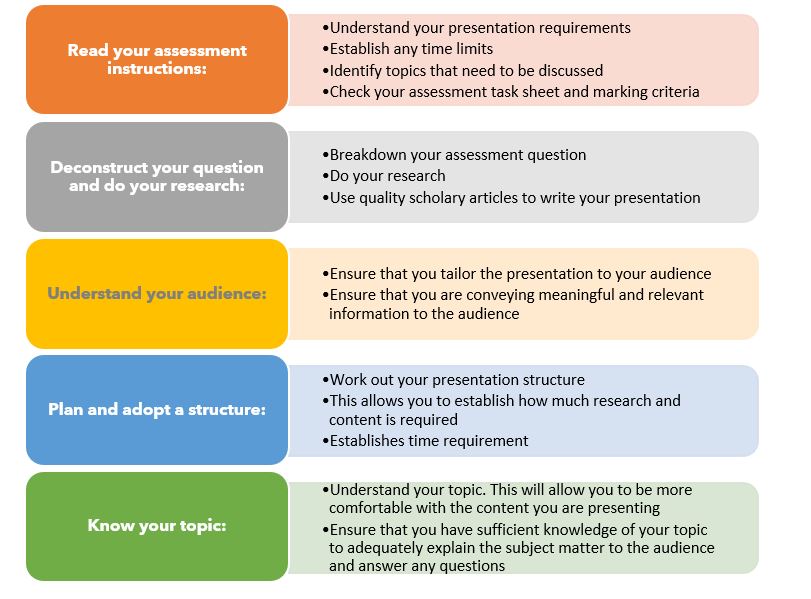

Preparation

Like other assessments or tasks, preparation is key to successfully delivering a presentation as it will help to ensure that you are heading in the right direction from the start. It will also likely increase your confidence in completing the presentation. Irrespective of the type of presentation, you can use the steps shown in Figure 73 for your preparation.

The steps shown in Figure 73 will essentially allow you to create tailored presentations which have directed content addressing a specific topic or task. This will allow you to engage your audience and deliver the message that you are trying to communicate effectively. Specific tips and tricks on how to present effectively are discussed later in this chapter.

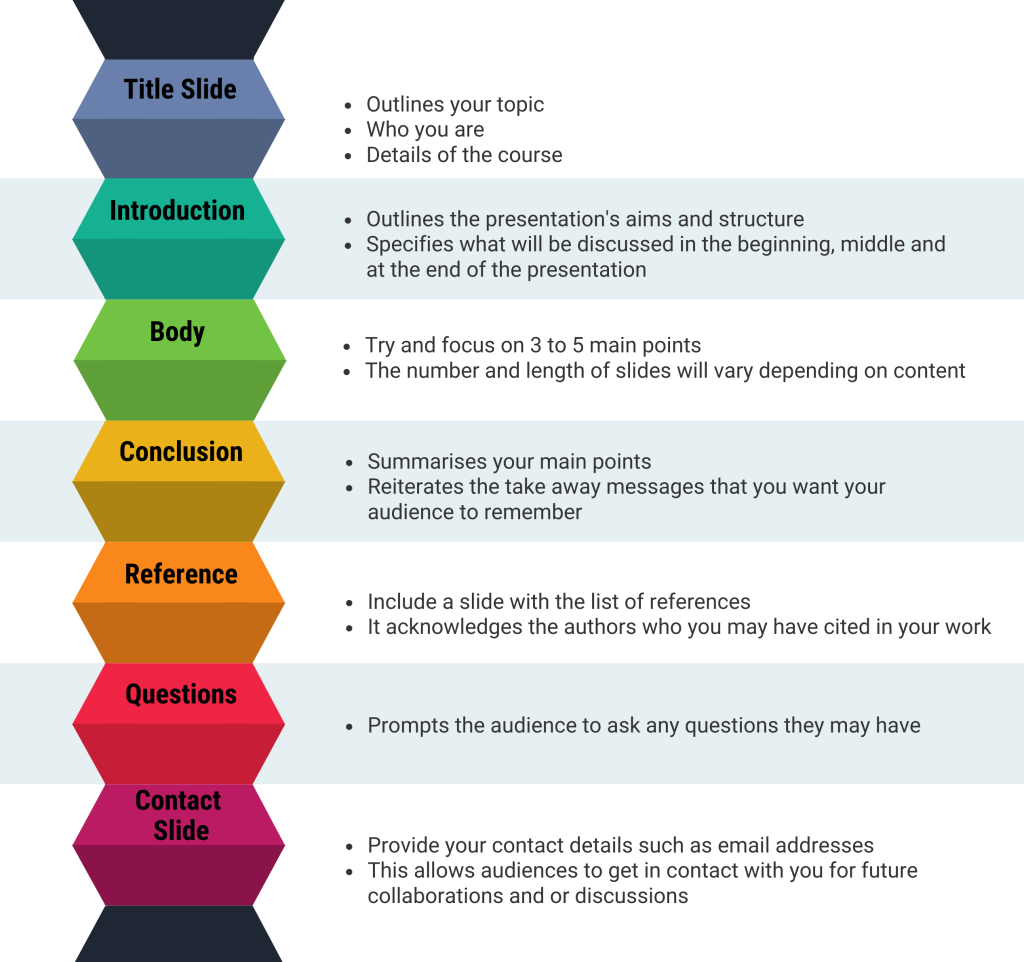

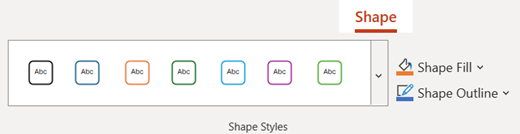

Presentation Structure

Similar to written assignments, creating a structure is crucial to delivering your presentation. The benefits of having a structure are that your presentation will flow in a logical manner and your audience will be able to follow and understand the information you are delivering. Presentation structures may vary depending on whether you are presenting in a group, presenting informally, or presenting a poster. Nonetheless, using some form of structure will likely be beneficial to both you and your audience. When structuring a presentation, also consider the platform, technology and setting. For example, if you are presenting informally, you may not require the use of any form of technology or visual equipment. You may just rely on hand written notes. In contrast, if you are presenting in a more formal setting, you may prefer to use technology to assist you, such as PowerPoint. Figure 77 offers a sample you can use to create your structure. Be sure to check any task sheet given to you by your lecturer. They may have a particular structure they wish for you to use for a specific task.

Tips and Tricks

There are certain strategies you can use to help deliver a good presentation. Not every strategy is going to be applicable to all presentations and every individual. You will need to choose the strategies that work for you and meet the objectives of your presentation, relate to your audience, and importantly address the overall task. Delivering your work is one of the hardest aspects of a presentation, but it is achievable. Therefore, it is essential that you have the appropriate approach in your delivery. This includes prior planning, practice, and being confident.

The tips and tricks in this section will guide you in preparing and delivering effective presentations. Please note that some of these tips and tricks may be more relevant to oral than visual presentations.

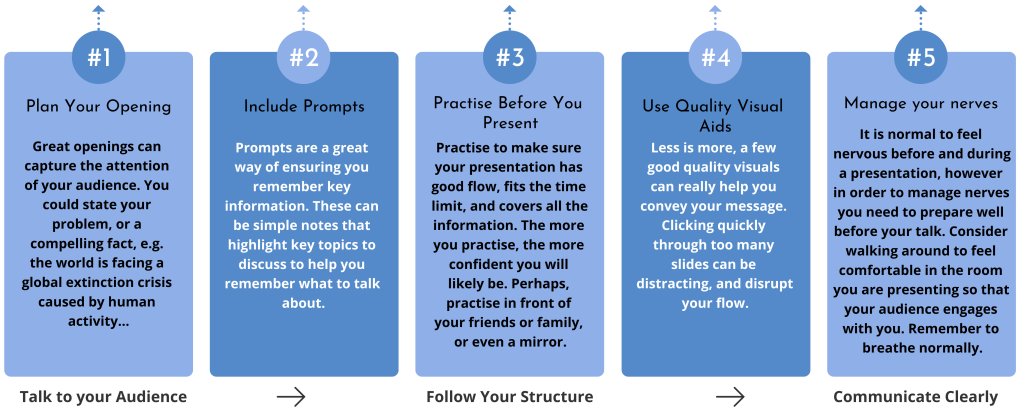

Tip 1: Improve your delivery

Figure 75 presents five simple ways to lift the standard of your delivery.

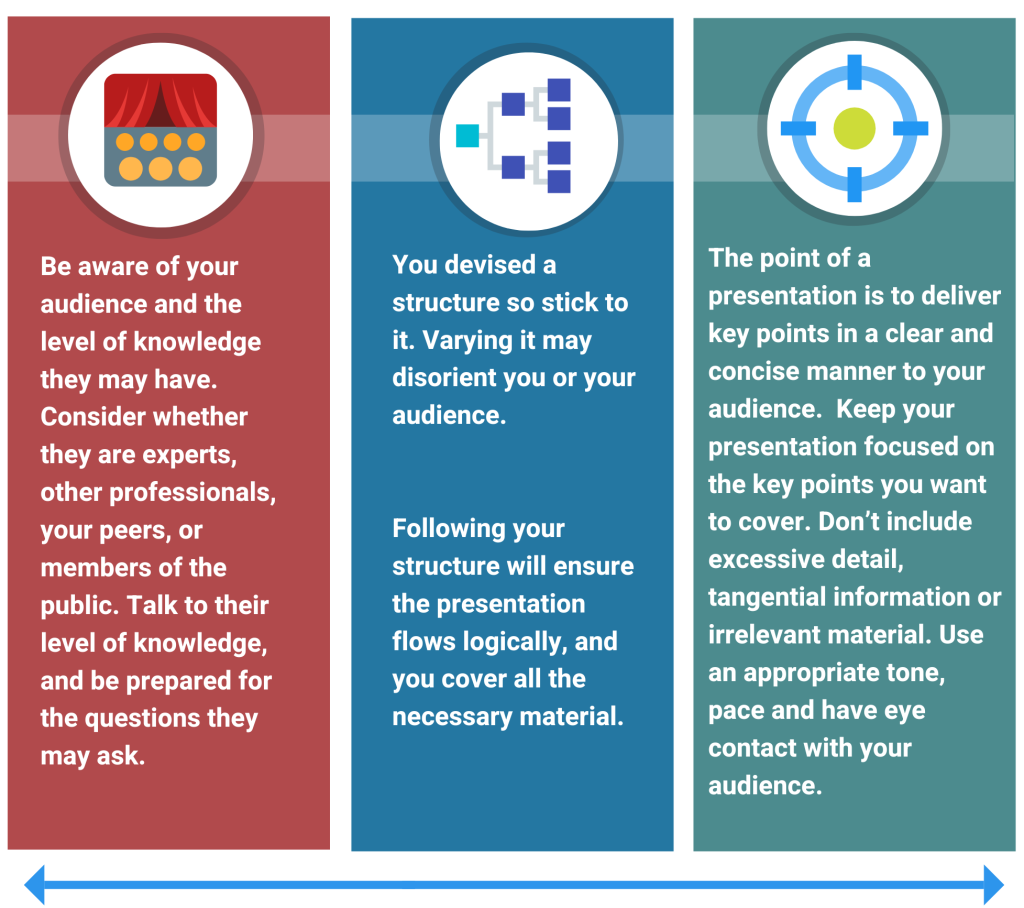

Tip 2: Stay on track with your presentation

Figure 76 presents reminders about your audience, structure, and focus of your presentation to keep you on track.

Tip 3: Consider your voice and body

When giving an oral presentation, you should pay special attention to your voice and body. Voice is more than the sum of the noises you make as you speak. Pay attention to inflection, which is the change in pitch or loudness of your voice. You can deliberately use inflection to make a point, to get people’s attention, or to make it very obvious that what you are saying right now is important. You can also change the volume of your voice. Speak too softly, and people will think you are shy or unwilling to share your ideas; speak too loudly, and people will think you are shouting at them. Control your volume to fit the audience and the size of the venue. If you use these tips, you should do a good job of conveying your ideas to an audience.

Some people have a tendency to rush through their presentations because they are feeling nervous. This means they speed up their speech, and the audience has a difficult time following along. Take care to control the speed at which you give a presentation so that everyone can listen comfortably. You can achieve this by timing yourself when preparing and practising your talk. If you are exceeding the time limit, you may either be speaking too quickly, or have too much content to cover.

Also, to add to the comfort of the listeners, it is always nice to use a conversational tone in a presentation. This includes such components as stance, gesture, and eye contact—in other words, overall body language. How do you stand when you are giving a presentation? Do you move around and fidget? Do you look down at the ground or stare at your note cards? Are you chewing gum or sticking your hands in and out of your pockets nervously? Obviously, you don’t want to do any of these things. Make eye contact with your audience as often as possible. Stand in a comfortable manner, but don’t fidget. Use gestures sparingly to make certain points. Most importantly, try to be as comfortable as you can knowing that you have practised the presentation beforehand and you know your topic well. This will help to calm nerves.

Tip 4: Consider your attitude

Attitude is everything. Your enthusiasm for your presentation will prime the audience. If you are bored by your own words, the audience will be yawning. If you are enthused by what you have to offer, they will sit up in their seats and listen intently. Also, be interested in your audience. Let them know that you are excited to share your ideas with them because they are worth your effort.

Tip 5: Consider the visuals

You might also think about using technology to deliver your presentation. Perhaps you will deliver a slide presentation in addition to orally communicating your ideas to your audience. Keep in mind that the best presentations are those with minimal words or pictures on the screen, just enough to illustrate the information conveyed in your oral presentation. Do a search on lecture slides or presentation slides to find a myriad suggestions on how to create them effectively. You may also create videos to communicate what you found in your research.

Today, there are many different ways to take the information you found and create something memorable through which to share your knowledge. When you are making a presentation that includes a visual component, pay attention to three elements: design, method, and function. The design includes such elements as size, shape, colour, scale, and contrast. You have a vast array of options for designing a background or structuring the visual part of your presentation, whether online or offline.

Consider which method to use when visually presenting your ideas. Will it be better to show your ideas by drawing a picture, including a photograph, using clip art, or showing a video? Or will it be more powerful to depict your ideas through a range of colours or shapes? These decisions will alter the impact of your presentation. Will you present your ideas literally, as with a photograph, or in the abstract, as in some artistic rendition of an idea? For example, if you decide to introduce your ideas symbolically, a picture of a pond surrounded by tall trees may be the best way to present the concept of a calm person. Consider also the purpose of the visuals used in your presentation. Are you telling a story? Communicating a message? Creating movement for the audience to follow? Summarising an idea? Motivating people to agree with an idea? Supporting and confirming what you are telling your audience? Knowing the purpose of including the visual element of your presentation will make your decisions about design and method more meaningful and successful.

As mentioned previously, not every strategy is applicable to all presentations or to every individual. Choose the strategies that are relevant to you and focus on them.

Delivering a presentation may be daunting, especially if you are new to university. But as we have discussed in this chapter, there are several approaches you can use to help you prepare and deliver your presentation effectively. While each individual may have their own approach, preparing, planning, structuring and practising your presentation will go a long way to help you achieve success. Following the steps and considering the ideas in this chapter places you in a good position to deliver presentations effectively. The approaches are beneficial, but ensure you are adhering to any specific requirements included in the assignment task sheet. Following the task sheet closely and applying these presentation skills will increase your likelihood of academic success.

- Understand the type of presentation you are asked to deliver.

- Start preparing in advance and adopt a structure.

- Know your topic well and your audience.

- Try and practice different strategies, tools, and speaking approaches well before your presentation and ensure it is within the allocated time limit. Remember, practice, practice and practice!

- Be confident in yourself, your presentation skills, and follow the plan you have developed.

Presentations Copyright © 2023 by Rhian Morgan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 14: Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas

14.1 Organizing a Visual Presentation 14.2 Incorporating Effective Visuals into a Presentation 14.3 Giving a Presentation 14.4 Creating Presentations: End-of-Chapter Exercises

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10. Designing and Delivering Presentations

In this chapter.

- Strategies for developing professional oral presentations and designing clear, functional slides

- Discussion of what makes presentations challenging and practical advice for becoming a more engaging and effective presenter

- Tips for extending the concepts of high quality presentations to creating videos and posters

Presentations are one of the most visible forms of professional or technical communication you will have to do in your career. Because of that and the nature of being put “on the spot,” presentations are often high pressure situations that make many people anxious. As with the other forms of communication described in this guide, the ability to present well is a skill that can be practiced and honed.

When we think of presentations, we typically imagine standing in front of a room (or auditorium) full of people, delivering information verbally with slides projected on a screen. Variations of that scene are common. Keep in mind, though, that the skills that make you a strong presenter in that setting are incredibly valuable in many other situations, and they are worth studying and practicing.

Effective presentation skills are the ability to use your voice confidently to communicate in “live” situations—delivering information verbally and “physically,” being able to engage your audience, and thinking on your feet. It also translates to things like videos, which are a more and more common form of communication in professional spheres. You will have a number of opportunities during your academic career to practice your presentation skills, and it is worth it to put effort into developing these skills. They will serve you well in myriad situations beyond traditional presentations, such as interviews, meetings, networking, and public relations.

This chapter describes best practices and tips for becoming an effective presenter in the traditional sense, and also describes how best practices for presentation skills and visuals apply to creating videos and posters.

Process for Planning, Organizing, and Writing Presentations

Similar to any other piece of writing or communication, to design a successful presentation, you must follow a thoughtful writing process (see Engineering Your Writing Process ) that includes planning, drafting, and getting feedback on the presentation content, visuals, and delivery (more on that in the following section).Following is a simple and comprehensive way to approach “writing” a presentation:

Step 1: Identify and state the purpose of the presentation. Find focus by being able to clearly and simply articulate the goal of the presentation—what are you trying to achieve? This is helpful for you and your audience—you will use it in your introduction and conclusion, and it will help you draft the rest of the presentation content.

Step 2: Outline major sections. Next, break the presentation content into sections. Visualizing sections will also help you assess organization and consider transitions from one idea to the next. Plan for an introduction, main content sections that help you achieve the purpose of the presentation, and a conclusion.

Step 3: Draft content. Once you have an outline, it’s time to fill in the details and plan what you are actually going to say. Include an introduction that gives you a chance to greet the audience, state the purpose of the presentation, and provide a brief overview of the rest of the presentation (e.g. “First, we will describe the results of our study, then we’ll outline our recommendations and take your questions”). Help your audience follow the main content of the presentation by telling them as you move from one section of your outline to the next—use the structure you created to keep yourself and your audience on track.

End with a summary, restating the main ideas (purpose) from the presentation and concluding the presentation smoothly (typically thanking your audience and offering to answering any questions from your audience). Ending a presentation can be tricky, but it’s important because it will make a lasting impression with your audience—don’t neglect to plan out the conclusion carefully.

Step 4: Write presentation notes. For a more effective presentation style, write key ideas, data, and information as lists and notes (not a complete, word-for-word script). This allows you to ensure you are including all the vital information without getting stuck reading a script. Your presentation notes should allow you to look down, quickly reference important information or reminders, and then look back up at your audience.

Step 5: Design supporting visuals. Now it’s time to consider what types of visuals will best help your audience understand the information in your presentation. Typically, presentations include a title slide, an overview or advance organizer, visual support for each major content section, and a conclusion slide. Use the visuals to reinforce the organization of your presentation and help your audience see the information in new ways.

Don’t just put your notes on the slides or use visuals that will be overwhelming or distracting—your audience doesn’t need to read everything you’re saying, they need help focusing on and really understanding the most important information. See Designing Effective Visuals .

At each step of the way, assess audience and purpose and let them affect the tone and style of your presentation. What does your audience already know? What do you want them to remember or do with the information? Use the introduction and conclusion in particular to make that clear.

For in-class presentations, look at the assignment or ask the instructor to make sure you’re clear on who your audience is supposed to be. As with written assignments, you may be asked to address an imagined audience or design a presentation for a specific situation, not the real people who might be in the room.

In summary, successful presentations

- have a stated purpose and focus;

- are clearly organized, with a beginning, middle, and end;

- guide the audience from one idea to the next, clearly explaining how ideas are connected and building on the previous section; and

- provide multiple ways for the audience to absorb the most important information (aurally and visually).

Developing a Strong Presentation Style

Since presentation are delivered to the audience “live,” review and revise it as a verbal and visual presentation, not as a piece of writing. As part of the “writing” process, give yourself time to practice delivering your presentation out loud with the visuals . This might mean practicing in front of a mirror or asking someone else to listen to your presentation and give you feedback (or both!). Even if you have a solid plan for the presentation and a strong script, unexpected things will happen when you actually say the words—timing will feel different, you will find transitions that need to be smoothed out, slides will need to be moved.

More importantly, you will be better able to reach your audience if you are able to look up from your notes and really talk to them—this will take practice.

Characteristics of a Strong Presentation Style

When it comes time to practice delivery, think about what has made a presentation and a presenter more or less effective in your past experiences in the audience. What presenters impressed you? Or bored you? What types of presentation visuals keep your attention? Or are more useful?

One of the keys to an effective presentation is to keep your audience focused on what matters—the information—and avoid distracting them or losing their attention with things like overly complicated visuals, monotone delivery, or disinterested body language.

As a presenter, you must also bring your own energy and show the audience that you are interested in the topic—nothing is more boring than a bored presenter, and if your audience is bored, you will not be successful in delivering your message.

Verbal communication should be clear and easy to listen to; non-verbal communication (or body language) should be natural and not distracting to your audience. The chart below outlines qualities of both verbal and non-verbal communication that impact presentation style. Use it as a sort of “rubric” as you assess and practice your own presentation skills.

| Project your voice appropriately for the room. Make sure everyone can hear easily, but avoid yelling or straining your voice. If using a microphone, test it (if possible), check in with your audience, and be willing to adjust. Don’t rush! Many people speak too quickly when they are nervous. Remind yourself to speak clearly and deliberately, with reasonable pauses between phrases and ideas, and enunciate carefully (especially words or concepts that are new to your audience). Speak with a natural rise and fall in your voice. Monotone speaking is difficult to listen to, but it is easy to do if you’re nervous or reading from a script. Remember that you are speaking to your audience, not at them, and try to use a conversational tone of voice. Limit the number of “filler” words in your speech—”uh,” “um,” “like,” “you know,” “so,” etc. These are words that creep in and take up space. You might not be able to eliminate them completely, but with awareness, preparation, and practice, you can keep them from being excessively distracting. |

| Position yourself where your audience can see you, but do not block their view of the visuals. Look at your audience. You should have practiced the presentation enough that you can look up from your notes and make them feel as though you’re talking to them. Stand comfortably (do not lean on the wall or podium). Depending on the setting, you might move around during the presentation, but avoid too much swaying or rocking back and forth while standing—stay grounded. Use natural, conversational gestures; avoid nervous fidgeting (e.g., pulling at clothing, touching face or hair). |

As you plan and practice a presentation, be aware of time constraints. If you are given a time limit (say, 15 minutes to deliver a presentation in class or 30 minutes for a conference presentation), respect that time limit and plan the right amount of content. As mentioned above, timing must be practiced “live”—without timing yourself, it’s difficult to know how long a presentation will actually take to deliver.

Finally, remember that presentations are “live” and you need to stay alert and flexible to deal with the unexpected:

- Check in with your audience. Ask questions to make sure everything is working (“Can everyone hear me ok?” or “Can you see the screen if I stand here?”) and be willing to adapt to fix any issues.

- Don’t get so locked into a script that you can’t improvise. You might need to respond to a question, take more time to explain a concept if you see that you’re losing your audience, or move through a planned section more quickly for the sake of time. Have a plan and be able to underscore the main purpose and message of your presentation clearly, even if you end up deviating from the plan.

- Expect technical difficulties. Presentation equipment fails all the time—the slide advancer won’t work, your laptop won’t connect to the podium, a video won’t play, etc. Obviously, you should do everything you can to avoid this by checking and planning, but if it does, stay calm, try to fix it, and be willing to adjust your plans. You might need to manually advance slides or speak louder to compensate for a faulty microphone. Also, have multiple ways to access your presentation visuals (e.g., opening Google Slides from another machine or having a flash drive).

Developing Strong Group Presentations

Group presentations come with unique challenges. You might be a confident presenter individually, but as a member of a group, you are dealing with different presentation styles and levels of comfort.

Here are some techniques and things to consider to help groups work through the planning and practicing process together:

- Transitions and hand-off points. Be conscious of and plan for smooth transitions between group members as one person takes over the presentation from another. Awkward or abrupt transitions can become distracting for an audience, so help them shift their attention from one speaker to the next. You can acknowledge the person who is speaking next (“I’ll hand it over to Sam who will tell you about the results”) or the person who’s stepping in can acknowledge the previous speaker (“So, I will build on what you just heard and explain our findings in more detail”). Don’t spend too much time on transitions—that can also become distracting. Work to make them smooth and natural.

- Table reads. When the presentation is outlined and written, sit around a table together and talk through the presentation—actually say what you will say during the presentation, but in a more casual way. This will help you check the real timing (keep an eye on the clock) and work through transitions and hand-off points. (Table reads are what actors do with scripts as part of the rehearsal process.)

- Body language. Remember that you are still part of the presentation even when you’re not speaking. Consider non-verbal communication cues—pay attention to your fellow group members, don’t block the visuals, and look alert and interested.

Designing Effective Visuals

Presentation visuals (typically slides, but could be videos, props, handouts, etc.) help presenters reinforce important information by giving the audience a way to see as well as hear the message. As with all other aspects of presentations, the goal of visuals is to aid your audience’s understanding, not overwhelm or distract them. One of the most common ways visuals get distracting is by using too much text. Plan and select visuals aids carefully—don’t just put your notes on the screen, but use the visuals to reinforce important information and explain difficult concepts.

The slides below outline useful strategies for designing professional, effective presentation slides.

- Write concise text. Minimize the amount of reading you ask your audience to do by using only meaningful keywords, essential data and information, and short phrases. Long blocks of text or full paragraphs are almost never useful.

- Use meaningful titles. The title should reveal the purpose of the slide. Its position on the slide is highly visible—use it to make a claim or assertion, identify the specific focus of the slide, or ask a framing question.

- Use images and graphics. Wherever possible, replace wordy descriptions with visuals. Well chosen images and graphics will add another dimension to the message you are trying to communicate. Make sure images are clear and large enough for your audience to see and understand in the context of the presentation.

- Keep design consistent. The visual style of the slides should be cohesive. Use the same fonts, colors, borders, backgrounds for similar items (e.g., all titles should be styled the same way, all photos should have the same size and color border). This does not mean every slide needs to look identical, but they should be a recognizable set.

- Use appropriate contrast. Pay attention to how easy it is to see elements on the screen. Whatever colors you choose, backgrounds and overlaid text need to be some version of light/dark. Avoid positioning text over a patterned or “busy” background—it is easy for the text to get lost and become unreadable. Know that what looks ok on your computer screen might not be as clear when projected.

Key Takeaway

- Create a structure for your presentation or video that clearly supports your goal.

- Practice effective verbal and non-verbal communication to become comfortable with your content and timing. If you are presenting as a group, practice together.

- Use visuals that support your message without distracting your audience.

Additional Resources

Fundamentals of Engineering Technical Communications Copyright © by Leah Wahlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter Twenty-One – Presenting as a Group

Imagine you have been assigned to a group for a project requiring a presentation at the end. “Now is the busiest time in my schedule and I do not have time to fit all these people into it,” the voice in your head reminds you. Then you ask the question: “Is there ever a non-busy time for assembling a group together for a presentation?” These thoughts are a part of a group presentation assignment. The combined expertise of several individuals is becoming increasingly necessary in many vocational (related to a specific occupation) and avocational (outside a specific occupation) presentations.

Group presentations in business may range from a business team exchanging sales data; research and development teams discussing business expansion ideas; to annual report presentations by boards of directors. Also, the government, private, and public sectors have many committees that participate in briefings, conference presentations, and other formal presentations. It is common for group presentations to be requested, created, and delivered to bring together the expertise of several people in one presentation. Thus, the task of deciding the most valuable information for audience members has become a coordination task involving several individuals. All group members are responsible for coordinating things such as themes, strong support/evidence, and different personalities and approaches in a specified time period. Coordination is defined in the dictionary as harmonious combination or interaction, as of functions or parts.

This chapter focuses on how the group, the speech assignment, the audience, and the presentation design play a role in the harmonious combination of planning, organization, and delivery for group presentations.

Preparing All Parts of the Assignment

In group presentations, you are working to coordinate one or two outcomes—outcomes related to the content (product outcomes) and/or outcomes related to the group skills and participation (process outcomes). Therefore, it is important to carefully review and outline the prescribed assignment of the group before you get large quantities of data, spreadsheets, interview notes, and other research materials.

Types of Group Presentations

A key component of a preparation plan is the type of group presentation. Not all group presentations require a format of standing in front of an audience and presenting. According to Sprague and Stuart (2005), there are four common types of group presentations:

- A structured argument in which participants speak for or against a pre-announced proposition is called a debate . The proposition is worded so that one side has the burden of proof, and that same side has the benefit of speaking first and last. Speakers assume an advocacy role and attempt to persuade the audience, not each other.

- The forum is essentially a question-and-answer session. One or more experts may be questioned by a panel of other experts, journalists, and/or the audience.

- A panel consists of a group of experts publicly discussing a topic among themselves. Individually prepared speeches, if any, are limited to very brief opening statements.

- Finally, the symposium is a series of short speeches, usually informative, on various aspects of the same general topic. Audience questions often follow (p. 318).

These four types of presentations, along with the traditional group presentation in front of an audience or on-the-job speaking, typically have pre-assigned parameters. Therefore, all group members must be clear about the assignment request.

Establishing Clear Objectives

For the group to accurately summarize for themselves who is the audience, what is the situation/occasion, and what supporting materials need to be located and selected, the group should establish clear objectives about both the process and the product being assessed.

Assessment plays a central role in optimizing the quality of group interaction. Thus, it is important to be clear whether the group is being assessed on the product(s) or outcome(s) only or will the processes within the group—such as equity of contribution, individual interaction with group members, and meeting deadlines—also be assessed. Kowitz and Knutson (1980) argue that three dimensions for group evaluation include (1) informational —dealing with the group’s designated tasks; (2) procedural —referring to how the group coordinates its activities and communication; and (3) interpersonal —focusing on the relationships that exist among members while the task is being accomplished. Groups without a pre-assigned assessment rubric may use the three dimensions to effectively create a group evaluation instrument.

The group should determine if the product includes both a written document and an oral presentation. The written document and oral presentation format may have been pre-assigned with an expectation behind the requested informative and/or persuasive content. Although the two should complement each other, the audience, message, and format for each should be clearly outlined. The group may create a product assessment guide (see Table 21) . Additionally, each group member should uniformly write down the purpose of the assignment. You may think you can keep the purpose in your head without any problem. Yet the goal is for each member to consistently have the same outcome in front of them. This will bring your research, writing, and thinking back to focus after engaging in a variety of resources or conversations.