- IKEA Case: One Company’s Fight to End Child Labor

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Focus Areas

- Business Ethics

- Business Ethics Resources

IKEA Case: One Company’s Fight to End Child Labor

A business ethics case study.

In this business ethics case study, Swedish multinational company IKEA faced accusations relating to child labor abuses in the rug industry in Pakistan which posed a serious challenge for the company and its supply chain management goals.

Empty garage with a highlighted walking path in front of an IKEA.

Photo credit: mastrminda/Pixabay

Yuvraj Rao '23 , a 2022-23 Hackworth Fellow at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics graduated with a marketing major and entrepreneurship minor from Santa Clara University.

Introduction

IKEA is a Swedish multinational company that was founded in 1943 by Ingvar Kamprad. [1] The company mainly provides simple, affordable home furniture and furnishings, and it pioneered DIY, or do it yourself, furniture. Kamprad originally sold binders, fountain pens, and cigarette lighters, but eventually expanded to furniture in 1948. According to the Journal of International Management, in 1953, Kamprad offered products that came as “a self assembled furniture” for the lowest price, which ultimately became a key part of IKEA’s value proposition going forward. In 1961, IKEA started to contact furniture factories in Poland to order chairs from a factory in Radomsko. [2] Outsourcing to Poland was mainly due to other Swedish furniture stores pressuring Swedish manufacturers to stop selling to IKEA. In the mid 1960’s, IKEA continued its supplier expansion into Norway, largely because IKEA didn’t want to “own their own line of production,” [3] and Germany due to its ideal location (downtown, suburban area) to place an IKEA store. Given IKEA’s suppliers were now not just in Sweden, it led to an increased importance on developing strong relationships with its suppliers.

In the following decades, IKEA continued its expansion and solidified its identity as a major retail outlet with parts being manufactured around the world. By the mid 90’s, IKEA was the “world’s largest specialized furniture retailer with their GDP reaching $4.5 billion in August of 1994.” [4] It also worked with 2,300 suppliers in 70 different countries, who supplied 11,200 products and had 24 “trading offices in nineteen countries that monitored production, tested product ideas, negotiated products, and checked quality.” [5] IKEA’s dependence on its suppliers ultimately led to problems in the mid 1990’s. At this time, IKEA was the largest furniture retailer in the world, and had nearly “100 stores in 17 countries.” [6] Also during this time, a Swedish documentary was released that highlighted the use of child labor in the rug industry in Pakistan, which impacted IKEA given it had production there. The rug industry in particular is extremely labor intensive and is one of the largest “export earners for India, Pakistan, Nepal and Morocco.” Here, children are forced to work long hours for very little pay (if there is any pay at all). In some cases, their wages are only enough to pay for food and lodging. In cases where children are not paid, the wages are used by the loom owner to pay the parents and agents who brought the children to the factories. Additionally, the work the children must do comes with a lot of risk. More specifically, children face risks of diminishing eyesight and damaged lungs from “the dust and fluff from the wool used in the carpets.” [7] As a result of these working conditions, many of these children are very sick when they grow up. Despite these terrible conditions, it isn’t that simple for families not to send children to work at these factories. A lot of the parents can’t afford food, water, education, or healthcare, so they are often left with no choice but to send their children to work for an additional source of income. [8]

IKEA and Child Labor Accusations

The accusations of child labor in the rug industry in Pakistan posed a serious challenge for IKEA and its supply chain management goals. It would need to address the serious issues of alleged injustice for the sake of its reputation and brand image. Additionally, as IKEA also had suppliers in India, it would need to be in compliance with India’s “landmark legislation act against child labor, the Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986.” [9]

As a result of these accusations, IKEA ultimately ended its contracts with Pakistani rug manufacturers, but the problem of child labor in its supply chain still persisted in other countries that were supplying IKEA. Marianne Barner, the business area manager for rugs for IKEA at the time, stated that the film was a “real eye-opener…I myself had spent a couple of months in India for some supply chain training, but child labor was never mentioned.” [10] She also added that a key issue was that IKEA’s “buyers met suppliers at offices in the cities and rarely visited the actual production sites.” [11] The lack of visits to the actual production sites made it difficult for IKEA to identify the issue of child labor in these countries.

To make matters worse, in 1995, a German film “showed pictures of children working at an Indian rug supplier... ‘There was no doubt that they were rugs for IKEA,’ says business area manager for textiles at the time, Göran Ydstrand.” [12] In response to these accusations, Barner and her team went to talk to suppliers in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India. They also conducted surprise raids on rug factories and confirmed that there was child labor in these factories. The issue of child labor, along with the accusations of having formaldehyde (a harmful chemical) in IKEA’s best selling BILLY bookcases and the discovery of unsafe working conditions for adults (such as dipping hands in petrol without gloves), led to increased costs and a significantly damaged reputation for the company.

It was later discovered that the German film released in 1995 was fake, and the renowned German journalist who was responsible for this film was involved in “several fake reports about different subjects and companies.” [13] IKEA was now left with three options. First, some members of IKEA management wanted to permanently shut down production of their rugs in South Asia. Another option was to do nothing and proceed with its existing practices now that it was announced that the film was fake. The third option was that the company could attempt to tackle the issue of child labor that was clearly evident in its supply chain, regardless of whether the film was fake or not. IKEA ultimately decided to opt for the third option, and its recent discoveries would eventually help guide the policies the company implemented to address these issues, particularly child labor in India.

Steps Taken to Address Child Labor in the Supply Chain

IKEA took multiple steps to deal with its damaged reputation and issues of child labor in its supply chain. One way in which it did this was through institutional partnerships. One such partnership was with Save the Children, which began in 1994. According to Save the Children’s website, one of the main goals of their partnership is to realize children's “rights to a healthy and secure childhood, which includes a quality education. By listening to and learning from children, we develop long-term projects that empower communities to create a better everyday life for children.” [14] Furthermore, the partnership is intended to “drive sustainable business operations across the entire value chain.” [15] Together, IKEA and Save the Children are focused on addressing the main causes of child labor in India’s cotton-growing areas. [16] Save the Children also advised IKEA to bring in an independent consultant to ensure that suppliers were in compliance with their agreements, which further improved IKEA’s practices in its supply chain. IKEA also partnered with UNICEF to combat child labor in its supply chain. According to the IKEA Foundation, in 2014, IKEA provided UNICEF with six new grants totaling €24.9 million with a focus “on reaching the most marginalized and disadvantaged children living in poor communities and in strengthening UNICEF’s response in emergency and conflict situations.” Additionally, five of the six grants were given to help programs in “Afghanistan, China, India, Pakistan, and Rwanda,” with a “focus on early childhood development, child protection, education, and helping adolescents to improve their lives and strengthen their communities.” [17]

Next, IKEA and Save the Children worked together to develop IWAY, which was launched in 2000. [18] IWAY is the IKEA code of conduct for suppliers. According to the IKEA website, “IWAY is the IKEA way of responsibly sourcing products, services, materials and components. It sets clear expectations and ways of working for environmental, social and working conditions, as well as animal welfare, and is mandatory for all suppliers and service providers that work with IKEA.” [19] In addition, IWAY is meant to have an impact in the following four areas: “promoting positive impacts on the environment,” “securing decent and meaningful work for workers,” “respecting children’s rights”, and “improving the welfare of animals in the IKEA value chain.” [20] IWAY is used as a foundation to collaborate with IKEA’s suppliers and sub-contractors to ensure supply chain transparency.

As mentioned previously, one of the main goals of IKEA’s partnership with Save the Children was to address child labor in India’s cotton-growing areas. To do this, IKEA and Save the Children developed a program that would ultimately help more than 1,800 villages between 2009 and 2014. More specifically, the program moved nearly 150,000 children out of child labor and into classrooms. Also, as a result of this program, more than 10,000 migrant children “moved back into their home communities.” [21] Last but not least, the program trained almost 2,000 teachers and 1,866 Anganwadi workers (whose duties include teaching students and educating villagers on healthcare [22] ) in order to provide each village with a community leader. This was to ensure that the community had a skilled leader to assist in educating the villagers. In 2012, the IKEA Foundation and Save the Children announced that they would expand with new programs in Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. This joint program illustrates IKEA’s commitment to improving communities in addition to helping children go to school.

Conclusion & Looking Ahead

IKEA has taken numerous steps to ensure that suppliers abide by the IWAY Code of Conduct. Companies around the world can learn from the policies IKEA has put in place to ensure that each company has control and complete oversight over their supply chains, which can lead to a more transparent and ethical supply chain. According to The IKEA WAY on Purchasing Products, Materials and Services, one way in which IKEA does this is by requiring all suppliers to share the content of the code to all co-workers and sub-suppliers, thus leading to more accountability among the company's suppliers. IKEA also believes in the importance of long term relationships with its suppliers. Therefore, if for some reason, a supplier is not meeting the standards set forth by the code, IKEA will continue to work with the supplier if the supplier shows a willingness to improve its practices with actionable steps to complete before a specified period of time. [23]

Additionally, during the IWAY implementation process, IKEA monitors its suppliers and service providers. To do this, IKEA has a team of auditors who conduct audits (both announced and unannounced) at supplier facilities. The auditors are also in charge of following up on action plans if suppliers are failing to meet the agreed upon standards specified by IWAY. Along with this, “IKEA…has the Compliance and Monitoring Group, an internal independent group that is responsible for independent verification of implementation and compliance activities related to IWAY and Sustainability.” [24] IKEA also has independent third party teams who conduct inspections on behalf of IKEA. [25] By conducting audits and putting together teams to ensure cooperation from suppliers throughout the supply chain, companies can be better equipped to prevent unethical practices in the production of goods and services. In Ximeng Han’s Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management, Han highlights IWAY’s importance in maintaining links with IKEA’s suppliers. [26] Therefore, IWAY plays a crucial role in ensuring supply chain transparency and in building a more ethical and sustainable supply chain.

In addition to all of the policies IKEA has put in place to address issues in its supply chain, the company has also donated a lot of money to combat child labor in India. More specifically, according to an IKEA Foundation article written in 2013, “Since 2000, the IKEA Foundation has committed €60 million to help fight child labour in India and Pakistan, aiming to prevent children from working in the cotton, metalware and carpet industries.” [27] Furthermore, in 2009, the company announced that it would donate $48 million to UNICEF to “help poor children in India.” [28]

IKEA’s goal to completely eliminate child labor from its supply chain is an ongoing battle, and it is still committed to ensuring that this is ultimately the case. More specifically, it is extremely difficult to completely eliminate child labor from a company’s supply chain because of the various aspects involved. According to a report published in 2018 by the International Labour Organization, these aspects include a legal commitment, building and “extending” social protection systems (including helping people find jobs), “expanding access to free, quality public education,” addressing supply chain issues, and providing more protection for children in general. [29] Furthermore, Han points out the potential downsides that could arise as a result of having a global supply chain like IKEA does. Given IKEA is an international retailer, the company “has to spend a lot of time, money and manpower to enter new markets due to the different cultures, laws and competitive markets in different regions, and there is also a significant risk of zero return.” [30] Han also argues that the COVID-19 pandemic showed IKEA’s and many other companies’ inability to respond to “fluctuations in supply and demand,” primarily due to inflexible supply chains. [31] This information points out the various aspects that need to align in order to completely end the issue of child labor throughout the world, as well as the difficulties of having a global supply chain, which is why child labor is so difficult to completely eliminate.

Specific to IKEA’s actions, in 2021, IKEA announced three key focus areas for its action pledge: “Further integrating children’s rights into the existing IKEA due diligence system (by reviewing IWAY from a child rights’ perspective in order to strengthen the code),” “accelerating the work to promote decent work for young workers,” and partnering “up to increase and scale efforts.” [32] IKEA’s fight to end child labor in India highlights the importance of supply chain transparency and putting policies in place that ensures cooperation from suppliers and all parties involved. Additionally, in a Forbes article written in 2021, “According to the data from the OpenText survey…When asked whether purchasing ethically sourced and/or produced products matters, 81 percent of respondents said yes.” [33] Steve Banker, who covers logistics and supply chain management, also adds, “What is interesting is that nearly 20 percent of these survey respondents said that it has only mattered to them within the last year, which indicates that the Covid pandemic, and some of the product shortages we have faced, has made consumers re-evaluate their stance on ethical sourcing.” [34] These results confirm that customers are now considering how a product was sourced in their purchasing decisions, which makes it even more important for IKEA to be transparent about its efforts to eliminate child labor from its supply chain. Furthermore, the company’s open commitment to eliminating child labor and helping communities in India is beneficial in maintaining a positive relationship with its stakeholders.

The increase in globalization has made it even more essential for companies to monitor their supply chains and have complete oversight over business practices. IKEA is one of the companies leading the way in building a more ethical and sustainable supply chain, but more companies need to follow suit and implement policies similar to IWAY that holds all parties in the supply chain accountable for their actions. Through supply chain transparency and accountability, companies will likely be better equipped to handle issues that arise throughout their respective supply chains. Furthermore, by implementing new policies, conducting audits, and maintaining close communication with suppliers, companies can work to eliminate child labor in their supply chains and put children where they belong: in school.

Reflection Questions:

- What does this case teach you about supply chain ethics?

- What are some of the ways in which management/leaders can ensure compliance of the standards set forth by a company in terms of supplier behavior and ethical sourcing?

- Who is primarily responsible for ensuring ethical behavior throughout the supply chain? Is it the company? The suppliers? Both?

- How can companies utilize the various platforms and technologies that exist today to better understand and oversee their supply chains?

- IKEA has taken numerous steps to address child labor in its supply chain. Do you think every business working in a context that may involve child labor has a duty to act in a similar way? Why or why not?

Works Cited

“ About Ikea – Our Heritage .” IKEA.

“Anganwadi Workers.” Journals Of India , 16 June 2020.

Banker, Steve. “ Do Consumers Care about Ethical Sourcing? ” Forbes , 9 Nov. 2022.

Bharadwaj , Prashant, et al. Perverse Consequences of Well-Intentioned Regulation ... - World Bank Group .

“ Child Labor in the Carpet Industry Rugmark: Carpets: Rugs: Pakistan .” Child Labor in the Carpet Industry RugMark |Carpets | Rugs | Pakistan .

“ Creating a Sustainable IKEA Value Chain with Iway. ” Sustainability Is Key in Our Supplier Code of Conduct .

“ Ending Child Labour by 2025 - International Labour Organization .” International Labour Organization .

“ Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA .” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

Foundation , ECLT. “ Why Does Child Labour Happen? Here Are Some of the Root Causes. ” ECLT Foundation , 17 May 2023.

Han, Ximeng. “ Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management. ” Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management | Atlantis Press , 27 Dec. 2022.

“ Human Rights and Global Sourcing: IKEA in India. ” Journal of International Management , 13 May 2011.

“ IKEA and IKEA Foundation .” Save the Children International .

“ IKEA Foundation Contributes €24.9 Million to UNICEF to Help Advance Children’s Rights. ” IKEA Foundation , 26 May 2020.

“ IKEA Foundation Helps Fight the Roots Causes of Child Labour in Pakistan .” IKEA Foundation , 18 Feb. 2013.

“ Ikea Gives $48 Million to Fight India Child Labor .” NBC News , 23 Feb. 2009.

“ IKEA Supports 2021 as the UN International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. ” About IKEA.

The Ikea Way on Purchasing Products , Materials and Services .

Jasińska, Joanna, et al. “ Flat-Pack Success: IKEA Turns to Poland for Its Furniture. ” – The First News .

Thomas , Susan. “ IKEA Foundation Tackles Child Labor in India’s Cotton Communities .” Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship , 15 July 2014.

[1] “About Ikea – Our Heritage.” IKEA .

[2] Jasińska, Joanna, et al. “Flat-Pack Success: IKEA Turns to Poland for Its Furniture.” – The First News .

[3] “Human Rights and Global Sourcing: IKEA in India.” Journal of International Management , 13 May 2011.

[4] “Human Rights and Global Sourcing: IKEA in India.” Journal of International Management , 13 May 2011.

[5] “Human Rights and Global Sourcing: IKEA in India.” Journal of International Management , 13 May 2011.

[6] “Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA.” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

[7] “Child Labor in the Carpet Industry Rugmark: Carpets: Rugs: Pakistan.” Child Labor in the Carpet Industry RugMark |Carpets | Rugs | Pakistan .

[8] Foundation , ECLT. “Why Does Child Labour Happen? Here Are Some of the Root Causes.” ECLT Foundation , 17 May 2023.

[9] Bharadwaj , Prashant, et al. Perverse Consequences of Well-Intentioned Regulation ... - World Bank Group .

[10] “Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA.” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

[11] “Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA.” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

[12] “Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA.” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

[13] “Film on Child Labour Is Eye-Opener for IKEA.” IKEA Museum , 31 Mar. 2022.

[14] “IKEA and IKEA Foundation.” Save the Children International .

[15] “IKEA and IKEA Foundation.” Save the Children International .

[16] “IKEA and IKEA Foundation.” Save the Children International .

[17] “IKEA Foundation Contributes €24.9 Million to UNICEF to Help Advance Children’s Rights.” IKEA Foundation , 26 May 2020.

[18] “IKEA and IKEA Foundation.” Save the Children International .

[19] “Creating a Sustainable IKEA Value Chain with Iway.” Sustainability Is Key in Our Supplier Code of Conduct .

[20] “Creating a Sustainable IKEA Value Chain with Iway.” Sustainability Is Key in Our Supplier Code of Conduct .

[21] Thomas, Susan. “IKEA Foundation Tackles Child Labor in India’s Cotton Communities.” Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship , 15 July 2014.

[22] “Anganwadi Workers.” Journals Of India , 16 June 2020.

[23] The Ikea Way on Purchasing Products, Materials and Services .

[24] The Ikea Way on Purchasing Products, Materials and Services .

[25] The Ikea Way on Purchasing Products, Materials and Services .

[26] Han, Ximeng. “Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management.” Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management | Atlantis Press , 27 Dec. 2022.

[27] “IKEA Foundation Helps Fight the Roots Causes of Child Labour in Pakistan.” IKEA Foundation , 18 Feb. 2013.

[28] “Ikea Gives $48 Million to Fight India Child Labor.” NBC News , 23 Feb. 2009.

[29] “Ending Child Labour by 2025 - International Labour Organization.” International Labour Organization .

[30] Han, Ximeng. “Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management.” Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management | Atlantis Press , 27 Dec. 2022.

[31] Han, Ximeng. “Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management.” Analysis and Reflection of IKEA’s Supply Chain Management | Atlantis Press , 27 Dec. 2022.

[32] “IKEA Supports 2021 as the UN International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour.” About IKEA .

[33] Banker, Steve. “Do Consumers Care about Ethical Sourcing?” Forbes , 9 Nov. 2022.

[34] Banker, Steve. “Do Consumers Care about Ethical Sourcing?” Forbes , 9 Nov. 2022.

Child Labor 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Around the world, children as young as 5 years old are working in mines, fields, and factories. They’re exposed to brutal working conditions like long hours, toxic materials, sexual exploitation, pollution, and dangerous equipment. While child labor has decreased over the decades, there are still millions of kids facing exploitation. In this article, we’ll define child labor, provide eight examples of the most common forms, and explain where you can find more learning opportunities about child labor.

Child labor disrupts a child’s education, damages their health, and exposes them to violence, sexual abuse, and exploitation. The most common types include debt bondage, sex trafficking, armed conflict, forced criminal activities, agriculture, mining, factory work, and domestic work.

What’s the meaning of child labor?

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines “child labor” as work that takes a young person’s childhood away from them. The work is “mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful” to kids and interferes with their education. As an example, putting a 15-year-old to work in a salt mine for 12 hours a day is child labor, while hiring a 15-year-old to wash dishes after school is most likely not. Laws vary from country to country. The United States has regulations regarding what hours 14 and 15-year-olds can work, while certain occupations (like power-driven bakery machines and power-driven forklifts) are completely prohibited for all minors .

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which was adopted in 1989, states that all ratifying parties must recognize a child’s right to be protected from economic exploitation and performing hazardous work. It also requires State Parties to take legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures to enforce this right. The CRC is the most widely ratified human rights treaty, although the United States and Somalia have not ratified it. In 2020, the ILO announced that all ILO party countries had ratified Convention No. 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, which provides for the elimination and prohibition of child labor like slavery, trafficking , armed conflict, pornography, and illegal activities. Convention No. 182, which was adopted in 1999, is the fastest ratified agreement in UN history.

How long has child labor existed?

Child labor has a long history, and for centuries, it wasn’t considered exploitative. From a very young age, children were expected to contribute to their families and communities. Why? The concept of childhood wasn’t as accepted as it is today. As the philosophy around children and childhood changed, so did society’s view of child labor. Child labor laws were passed and rates of child labor fell around the world. It’s still prevalent in areas affected by poverty. In 2016, global estimates found that ⅕ of kids in Africa are involved in child labor.

What are examples of child labor?

Child labor refers to any exploitative and harmful labor performed by a child. Here are eight examples:

#1. Debt bondage

When people go into debt and can’t pay with money or goods, the person owed the money may suggest that family members – including children – work for very little or for nothing to pay off the debt. This is often a trick as the debt-holder has no intention of lifting the debt or ending the forced labor. Because the debt can never be paid, debt bondage can keep multiple generations enslaved. This form of exploitation was one of the most prevalent types of forced labor in 2016 .

#2. Child sex trafficking

Child sex trafficking is the buying, selling, and moving of children for sexual exploitation. Precise numbers are hard to calculate, but a 2016 UNODC Global Report found that women and girls are trafficked more often for sexual slavery and marriage . Armed groups are a common perpetrator, although experts say trafficked children are very likely to know or even be related to their exploiters.

#3. Armed conflict

According to UNICEF, more than 105,000 children were exploited in armed conflict between 2005 and 2022 . Because of how difficult it is to track child labor statistics, the number is likely higher. Children in armed conflict are used as soldiers, scouts, cooks, guards, messengers, and more. Some are abducted or threatened into work, while others are trying to earn money for their families. Regardless of the specifics, using children for any reason in armed conflict is a major violation of human rights law.

#4. Forced criminal activities

Children are exploited for a variety of criminal activities, such as theft, producing and trafficking drugs, burglarizing homes, and more. According to a post on The Conversation, organized crime gangs can groom and exploit kids as young as 12 years old. Kids may be initially paid with drugs and alcohol, which can trigger addiction and make it even harder to break free. In Ecuador, police found stuffed animals at one cartel hideout, leading them to believe that the gang was using toys to lure children . In that same area, most of the 230 people arrested between January and April 2022 were just 17 or 18 years old.

#5. Agriculture

According to the International Labour Organization, child labor is concentrated in agriculture . 60% of the child laborers aged 5-17 years old are in work like farming, fishing, livestock, forestry, and aquaculture. Poverty is the main driver of child labor in agriculture. Child labor may also be more widely accepted in agriculture because of its long-standing history. Children can participate in agricultural activities on family farms without being child laborers, but any work that interferes with schooling, harms a child’s health and development, or exceeds what’s age appropriate for the child is exploitation.

Mining is a dangerous activity even for adults, but around the world, thousands of kids labor in mines for materials like cobalt, salt, gold, and mica. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, children as young as seven mine for cobalt, which is used for lithium-ion batteries. In 2014, around 40,000 kids were working in cobalt mines . Conditions can be brutal and deadly. Many miners work long hours without protective equipment for pay as low as 1-2 dollars a day.

#7. Factory work

Factories make a huge amount of products like clothing, toys, and meat. They’re also rife with poor ventilation, toxic materials, and hazardous machinery. When kids are exploited in factories, they face long-term health and development consequences. In 2023, the United States Department of Labor discovered more than 100 kids – some just 3 years old – employed in factories across eight states. Their jobs included cleaning dangerous equipment like bone cutters and skull splitters in meatpacking plants.

#8. Domestic work

Domestic work includes a variety of tasks and services, some of which don’t constitute exploitative child labor. Exploitation occurs when kids are employed in the domestic work sector at ages younger than is legal and are exposed to hazardous conditions. Any domestic work that interferes with a child’s education is also child labor. In many places, domestic work exploitation is “hidden” as kids – especially girls – are expected to contribute to the household and prepare for a life as an adult. According to the International Labour Organization, kids face heightened risks when they live in the household where they’re employed. Without consistent contact from the child’s parents or friends, it’s much easier for employers to exploit a child.

Where can you learn more about child labor?

Child labor is one of the most troubling human rights violations . Here’s a short list f of classes, books, and documentaries that shine a light on this urgent issue:

The ILO’s e-learning tools

The International Labour Organization offers a handful of courses to help students understand child labor and what role ILO stakeholders play. Using interactive tests and exercises, these free courses are self-paced. Examples include the reporting on child labor for media course, which is 8 hours long and available in English, and the eliminating child labor course, which is a 2-hour course for labor inspectors and child labor monitors. It’s available in French, Spanish, Vietnamese, English, and Mongolian.

FAO e-learning academy

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations offers a 2.5-hour course on child labor in agriculture. It gives an overview of child labor in agriculture, foundational knowledge on what is and isn’t child labor, its causes and consequences, and more. It’s available in English, Spanish, French, Turkish, and Russian. It’s also available in Portuguese as a downloadable offline package.

Harvard University’s Child Protection: Children’s Rights Theory in Theory and Practice

This 16-week course teaches students about the causes and consequences of child protection failures. Topics include the strategies, international laws, standards, and resources that protect all children, as well as how students can apply strategies to their careers. It’s a self-paced course, but it takes 16 weeks with 2-5 hours of work per week. Students can audit the course for free or pay a fee for a certificate.

Agents of Reform: Child Labor and the Origins of the Welfare State (2021)

Elisabeth Anderson

This book explores the late 19th-century labor movement, groundbreaking child labor laws, and the regulatory welfare state. Through seven in-depth case studies from Germany, France, Belgium, Massachusetts, and Illinois, Anderson explores individual reformers and challenges existing explanations of welfare state development.

Blood and Earth: Modern Slavery, Ecocide, and the Secret to Saving the World (2016)

Kevin Bales

Expert Kevin Bales, who has traveled around the world documenting human trafficking, describes the link between slavery and environmental destruction. In addition to being a human rights violation, human trafficking is destroying the earth. Backed by seven years of research and travel, Bales reports from places where this link is most concentrated. While it doesn’t focus exclusively on child labor, child labor is a huge part of human trafficking.

“The Chocolate War” (2022)

Director: Miki Mistrati

The cocoa and chocolate industry is rife with child slavery. In 2001, eight large companies, the World Cocoa Foundation, and the Chocolate Manufacturers Association signed a pledge to end child labor and slavery in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, but the deadline has been postponed to 2025. Why won’t the industry change? “The Chocolate War” follows Terry Collingsworth, a human rights lawyer, for five years as he takes on the multi-billion-dollar chocolate industry. The film was nominated for a Cinema for Peace Award and Best Documentary at the Warsaw International Film Festival.

You may also like

11 Examples of Systemic Injustices in the US

Women’s Rights 101: History, Examples, Activists

What is Social Activism?

15 Inspiring Movies about Activism

15 Examples of Civil Disobedience

Academia in Times of Genocide: Why are Students Across the World Protesting?

Pinkwashing 101: Definition, History, Examples

15 Inspiring Quotes for Black History Month

10 Inspiring Ways Women Are Fighting for Equality

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Clean Water

15 Trusted Charities Supporting Trans People

15 Political Issues We Must Address

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

This website uses cookies

The only cookies we store on your device by default let us know anonymously whether you have seen this message. With your permission, we also set Google Analytics cookies. You can click “Accept all” below if you are happy for us to store cookies (you can always change your mind later). For more information please see our Cookie Policy .

Google Analytics will anonymize and store information about your use of this website, to give us data with which we can improve our users’ experience.

Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Child Labour

If you have questions, feedback or you're looking for further help in protecting human rights, please contact us at

What is Child Labour?

Child labour is work that harms children’s well-being and hinders their education, development and future livelihood, according to the International Labour Organization ( ILO ). Not all child labour is harmful; for example, if it is light work and does not interfere with a child’s education or right to leisure, such as, children helping their parents on a farm with non-harmful activities or in a shop outside of school hours. Moreover, youth employment and student work are considered legal and may contribute positively to the development of children and young people.

What is the Dilemma?

The dilemma for responsible business is how to address child labour responsibly given the complex social and economic context in which it occurs. While a business may seek to respect the principles contained in international labour standards and national laws on minimum age, removing children (or having children removed) from their operations or supply chains without considering the implications for them could potentially worsen their situation. For example, removing children from the workplace without providing safer and suitable alternatives may leave them vulnerable to more exploitative work elsewhere (e.g. in subcontractor companies), as well as potentially lead to negative health and well-being implications due to increased poverty within their family.

Prevalence of Child Labour

The ILO and UNICEF estimate that 160 million children — 63 million girls and 97 million boys — were in child labour globally at the beginning of 2020, accounting for almost 1 in 10 of all children worldwide. [2] 79 million children (nearly 50% of all children in child labour) were involved in hazardous work such as agriculture or mining, operating dangerous machinery or working at height. However, this number is an approximation — child labour is difficult to quantify as it is often hidden due to its illegal nature. The identification of children in the workplace can be further impeded by a lack of reliable documents such as birth certificates and the fact that it often occurs in rural settings or in areas of cities where authorities have little visibility.

Key trends include:

- Global progress against child labour has stagnated since 2016 despite global efforts to eradicate child labour by 2025, as per target 8.7 [1] of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- The COVID-19 crisis threatened to further erode global progress against child labour. ILO estimates suggested that a further 8.9 million children would be in child labour by the end of 2022 due to rising poverty and parental deaths driven by the pandemic.

- Since the start of the pandemic, child labour risks increased in more than 83 countries. Africa remains the highest risk region, with 6 of the 10 highest risk countries ( Verisk Maplecroft ). According to an ILO report published in June 2021, there are more children in child labour in sub-Saharan Africa than in the rest of the world combined.

- The year 2021 was designated as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour by UN Member States to further increase global efforts in eliminating child labour.

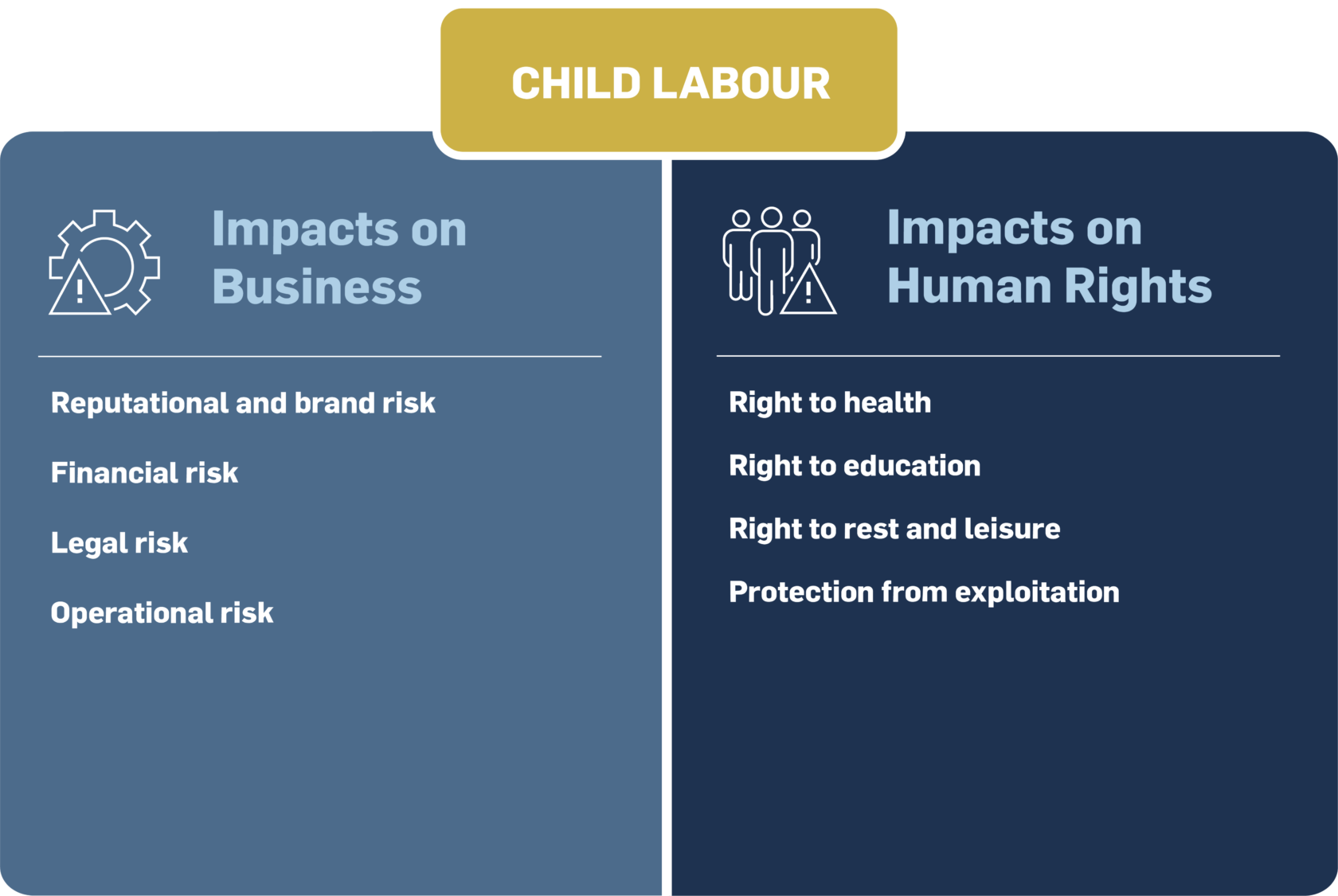

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by child labour risks in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Reputational and brand risk : Campaigns by NGOs, trade unions, consumers, media and other stakeholders can result in reduced sales and/or brand erosion.

- Financial risk : Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

- Legal risk : Legal charges can be brought against the company, up to and including criminal charges, which can result in imprisonment in some countries and usually involve significant fines and/or surrendering of goods produced by child labour (see section ‘ Definition and Legal Instruments ’). Former child workers may also be able to sue their exploitative employers, potentially including companies further up in the supply chain.

- Operational risk : Changes to a company’s supply chains made in response to the discovery of child labour may result in disruption. For example, companies may feel the need to terminate supplier contracts (resulting in potentially higher costs and/or disruption) and direct sourcing activities to lower-risk locations.

Impacts on Children’s Rights

Child labour has the potential to impact a range of children’s rights, [3] including but not limited to:

- Right to health and to an adequate standard of living ( CRC , Articles 6.2 and 27.1): Children’s health and personal development may be negatively impacted through engagement in work activities, which are not age-appropriate.

- Right to education ( CRC , Article 28): Working hours may preclude children from attending school. Likewise, working children may be too tired to benefit fully from their studies. Children’s ability to learn and join the formal labour market at a later date may also be compromised by child labour.

- Right to rest and leisure and to cultural life ( CRC , Article 31.1): Children involved in child labour often do not have sufficient time to develop socially and culturally through play and interaction with other children.

- Right to protection from economic exploitation ( CRC , Article 32): Children have the right to be protected from economic exploitation. This includes the right to be protected from work that is hazardous or likely to interfere with the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.

For further information on children’s rights, please refer to UNICEF’s helpful summary of children’s rights listed in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The following SDG targets relate to child labour :

- Goal 8 ( “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” ), Target 8.7 : Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

- Goal 16 ( “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” ), Target 16.2 : End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence and torture against children

Progress on these targets and Global Goals will also help advance other goals, for example Goal 3 ( “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” ) and Goal 4 ( “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” ).

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address child labour responsibly in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO and UNICEF, Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward : The most up-to-date global estimates of child labour from the ILO and UNICEF, including an overview of the impact on child labour from COVID-19.

- ILO and International Organisation of Employers (IOE), Child Labour Guidance Tool for Business : This tool helps companies meet the due diligence requirements laid out in the UN Guiding Principles , as they pertain to child labour.

- Ethical Trading Initiative, Base Code Guidance: Child Labour : A step-by-step guide for businesses on eliminating child labour in global supply chains.

Definition & Legal Instruments

According to the ILO , the term “child labour” is work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development. It refers to work that:

- Is mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and/or

- Interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

It is important to distinguish between minimum age violations and the worst forms of child labour. The minimum age for work is defined as follows:

- The minimum age for work should not be less than the age for completing compulsory schooling, and in general, not less than 15 years. However, States whose economy and educational facilities are insufficiently developed may initially specify a minimum age of 14 years as a transitional measure ( Minimum Age Convention No. 138 ).

- Children can engage in light work from 13 years of age (or 12 as a transitional measure), provided that it does not interfere with their education or vocational training and that it does not have a negative impact on their health ( Minimum Age Convention No. 138 ).

The worst forms of child labour include ( Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention No. 182 ):

- The sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict;

- The use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution or pornographic performances;

- The use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities (e.g. production and trafficking of drugs).

Child labour also includes hazardous work performed by young workers over the legal minimum age for work but under 18 years. According to the ILO , hazardous work is defined as work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.

Examples of hazardous child labour include:

- Work that exposes children to physical, psychological or sexual abuse;

- Work underground, underwater, at dangerous heights or in confined spaces;

- Work with dangerous machinery, equipment and tools, or which involves the manual handling or transport of heavy loads;

- Work in an unhealthy environment which may, for example, expose children to hazardous substances, agents or processes, or to temperatures, noise levels, or vibrations damaging to their health;

- Work under particularly difficult conditions such as work for long hours or during the night or work where the child is unreasonably confined to the premises of the employer.

The ILO provides further guidance on types of hazardous work, while national legislation often includes lists of prohibited hazardous activities for children. It is important to note that the list of prohibited hazardous activities will vary between states, depending on a variety of contextual factors; it is, therefore, often better to follow best practice and work to prevent children working in hazardous jobs.

Legal Instruments

Ilo and un conventions.

Two ILO Conventions and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provide the framework for national law to define a clear line between what is acceptable and what is not in terms of child employment. The effective abolition of child labour is one of the five fundamental rights and principles at work by the ILO which Member States must promote, irrespective of whether or not they have ratified the respective conventions listed below

- ILO Minimum Age Convention, No. 138 (1973) sets a general minimum age of 15 for employment with some exceptions for developing countries.

- ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, No. 182 (1999) prohibits worst forms of child labour, including hazardous work by young workers under 18.

- The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits child labour and requires signatories to regulate minimum age and conditions of work for children.

The ILO Convention No. 182 has been ratified by all 187 ILO Member States (the only ILO Convention that has achieved universal ratification ). The UN Convention on the Right of the Child has also been ratified by all countries except the United States (although the United States signed the Convention). Furthermore, most States have ratified ILO Convention No. 138. This means that in most countries relevant national legislation should be in place to implement the terms of these international legal instruments. In due diligence, it is important to check the ratification status for particular countries as an indicator of potentially more limited state protections against child labour. However, ratification does not guarantee that these countries are free from child labour, as the existence and enforcement of national laws to address child labour varies.

The fight against child labour is included as one of the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact: “ Principle 5 : Businesses should uphold the effective abolition of child labour” . The four labour principles of the UN Global Compact are derived from the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work .

These fundamental principles and rights at work have been affirmed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in International Labour Conventions and Recommendations and cover issues related to child labour, discrimination at work, forced labour and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining.

Member States of the ILO have an obligation to promote the effective abolition of child labour, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question.

Other Legal Instruments

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ( UNGPs ) set the global standard regarding the responsibility of businesses to respect human rights in their operations and across their value chains. The Guiding Principles call upon States to consider a smart mix of measures — national and international, mandatory and voluntary — to foster business respect for human rights. Businesses should consider the UNGPs in their operational and supply chain decisions, and when following national legislation.

Children’s Rights and Business Principles ( CRBPs ) were first proposed in 2010 and are based on existing standards, initiatives and best practices related to business and children. These Principles seek to define the scope of corporate responsibility towards children. Covering a wide range of critical issues – from child labour to marketing and advertising practices to the role of business in aiding children affected by emergencies – the Principles call on companies everywhere to respect children’s rights through their core business actions, but also through policy commitments, due diligence and remediation measures.

Regional and Domestic Legislation

Companies are increasingly subject to non-financial reporting requirements and due diligence obligations in the jurisdictions in which they operate, which often include disclosures on their performance. There are several high-profile examples of national legislation that specifically mandate human rights-related reporting and other positive legal duties, such as due diligence, including the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act 2015 , Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018 , the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010 , the French Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law 2017 , the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains 2023 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2022 .

Also, in 2021 the Netherlands submitted a Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct, and the European Commission announced its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). This Directive is likely to come into force between 2025 and 2027 and will make human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory for larger companies.

These mandatory due diligence and disclosure laws require companies to publicly communicate their efforts to address actual and potential human rights impacts, including the worst forms of child labour. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to real legal risk for companies.

Contextual Risk Factors

The prevention of child labour requires an understanding of its underlying causes and the consideration of a wide range of issues which may increase the risk of child labour, that often interfere and reinforce one another, such as inadequate family income and poor or non-existent educational facilities.

Key risk factors include:

- High rates of poverty and unemployment , especially where there is a lack of state support (e.g. unemployment benefits). In regions where adult unemployment is high, children may be required to work to assist the family.

- Low wages can exacerbate the prevalence of poverty and drive the need for children to work alongside their parents to supplement household income (see Living Wage issue).

- Lack of educational opportunities for children due to a lack of school facilities or where school tuition costs and educational materials are considered too expensive. Where educational facilities or other forms of childcare are missing, children tend to accompany (and often help) their parents at work.

- Lack of safe alternative pathways to employment results in adolescents finding themselves moving from one form of hazardous work to another. The alternative is for adolescents to have access to safe work that could lead to long-term employment.

- Poorly enforced domestic labour laws due to a lack of government resources, capacity or commitment to fully implement state duty to protect citizens against human rights violations. This can result in a lack of or inadequate training of labour inspectors, as well as improper payments made by employers to (sometimes poorly compensated) inspectors to overlook child labour violations.

- Informal economies are associated with higher child labour risks. Informality often leads to lower and less regular incomes, inadequate and unsafe working conditions, extreme job precarity and exclusion from social security schemes, among other factors. All of these can spur families to turn to child labour in the face of financial distress.

- Rural areas are also associated with a higher prevalence of child labour. There are 122.7 million rural children (13.9%) in child labour compared to 37.3 million urban children (4.7%). Job opportunities are often scarce in rural areas, leaving children to find work to assist their families, with government oversight of these areas much lower.

- Intersectionality , or the interaction between gender, race, ethnicity, age and other categories of difference, leads to increased child labour risks. For example, girls from an ethnic minority living in poor rural areas may be more exposed to the risks of child labour exploitation.

Industry-specific Risk Factors

Whilst child labour is present in many industries, the following present particularly significant levels of risk. To identify potential child labour risks for other industries, companies can access the CSR Risk Check .

Agriculture

According to ILO 2020 estimates , around 70% of child labourers around the world — 112 million children — work in agriculture, including fishing, aquaculture and livestock rearing. Although certain work on family farms is acceptable for children — provided that it is not hazardous and does not prevent them from receiving an education — many forms of child work in agricultural supply chains are not legal. The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that the most common items produced by child labour in agriculture include bananas, cattle and dairy products, cocoa, coffee, cotton, fish, rice, sugar and tobacco.

Agriculture-specific risk factors include the following:

- Piece rate: Many agricultural jobs are paid by the amount of produce picked, which encourages parents to bring their children along with them to help collect greater volumes.

- Seasonal migrant labour: The agricultural sector traditionally relies heavily on migrant labour due to seasonality. This can mean the children of migrant labourers are often not in one place long enough to attend school, so work with their parents in the field instead.

- Families: Family-based child labour is hard for companies to identify, as family farms usually feed into larger co-operatives or wholesalers and are relatively invisible within the supply chain. Furthermore, family-based child labour can be easily hidden on inspection.

- OECD-FAO, Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains : This guidance provides a common framework to help agro-businesses and investors support sustainable development and identify and prevent child labour.

- FAO, Framework on Ending Child Labour in Agriculture : This framework guides the FAO and its personnel on the integration of measures addressing child labour within FAO’s typical work, programmes and initiatives.

- FAO, Regulating Labour and Safety Standards in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Sectors : This resource provides information on international labour standards that apply in agriculture, including those on child labour.

- FAO, e-Learning Academy: Business Strategies and Public-Private Partnerships to End Child Labour in Agriculture : This course presents several business-oriented strategies to reduce child labour in agricultural supply chains.

- ILO, Child Labour in the Primary Production of Sugarcane : This report provides an overview of the sugarcane industry, including key challenges and opportunities in addressing child labour.

- Fair Labor Association, ENABLE Training Toolkit on Addressing Child Labor and Forced Labor in Agricultural Supply Chains : This toolkit guides companies on supply chain mapping and the abolition of child labour in supply chains. It contains six training modules, a facilitator’s guide, presentation slides and a participant manual.

- Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), From Farm to Table: Ensuring Fair Labour Practices in Agricultural Supply Chains : This resource provides guidelines on what investors should be looking for from companies to eliminate labour abuses in their agricultural supply chains.

- Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform : The SAI Platform guidance document on child labour facilitates the development of their members’ policies on child labour.

- Rainforest Alliance, Child Labor Guide : This guide has been developed to support the efforts of farm management to address the risks of child labour on their farms with a focus on coffee, cocoa, hazelnut and tea; however, it can be used for other crops as well.

- German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa : This multi-stakeholder initiative aims to improve the livelihood of cocoa farmers and their families, as well as to increase the proportion of certified cocoa according to sustainability standards. The Initiative’s background paper provides helpful information on child labor in the West African cocoa sector and possible solutions to address it.

- Fairtrade International, Guide for Smallholder Farmer Organisations – Implementing Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD) : This guidance was developed to provide advice and tools on HREDD for farmer organisations to implement.

- UNICEF, Mapping Child Labour Risks in Global Supply Chains: This paper provides a detailed analysis of the Apparel, Electronics and Agricultural Sectors. It was written as a background report for the Alliance 8.7 report on “Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains”.

Fashion and Apparel

The fashion and apparel industry may be linked to significant child labour risks. Fashion and apparel-specific risk factors include the following:

- Subcontracting: This industry features a lot of subcontracting and outsourcing, making tracing where a product was made and by whom difficult. In-depth due diligence checks on this part of a supply chain are, therefore, often overlooked.

- Homeworking: Homeworking is particularly hard to monitor, as the location of homeworking is often unknown to companies and there is no way to control working hours or who is doing the work. Research from the University of California, Berkeley , shows that the activities often outsourced to homeworkers are usually finishing tasks, such as beading, embroidery or adding tassels — activities that require delicate handiwork as opposed to being produced by machinery in a factory. Children’s smaller hands can be considered useful for this delicate handiwork.

- Gender: There is a significant gender aspect in this regard, with studies showing most homeworkers in the apparel industry are women and girls (see Gender Equality issue).

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment & Footwear Sector : The guidance aims to help fashion and apparel businesses implement the due diligence recommendations contained in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises in order to avoid and address the potential negative impacts of their activities and supply chains on a range of human rights, including child labour.

- Fair Wear Foundation, The Face of Child Labour: Stories from Asia’s Garment Sector : This report seeks to promote a greater understanding of the realities of child labour by presenting interviews with children who were found working in Asia’s garment sector.

- Fair Labor Association, Child Labor in Cotton Supply Chains: Collaborative Project on Human Rights in Turkey : The report explores cotton and garment supply chains in Turkey and provides recommendations for companies and other stakeholders on eliminating child labour from cotton supply chains.

- Fair Labor Association, Children’s Lives at Stake: Working Together to End Child Labour in Agra Footwear Production : The report demonstrates a high prevalence of child labour in shoe production in Agra, India, and provides recommendations for brands, including on enhancing their subcontracting policies.

- SOMO, Branded Childhood: How Garment Brands Contribute to Low Wages, Long Working Hours, School Dropout and Child Labour in Bangladesh : This report illustrates a link between child labour and low wages for adult workers and provides a series of concrete recommendations for brands and retailers sourcing from Bangladesh on combatting child labour.

- Save the Children, In the Interest of the Child? Child Rights and Homeworkers in Textile and Handicraft Supply Chains in Asia : This study provides data on both the positive and negative impact of home-based work and work in small workshops on child rights and identifies best practices to improve child rights in such settings.

- UNPRI, An Investor Briefing on the Apparel Industry : Moving the Needle on Labour Practices : The resource guides institutional investors on how to identify negative human rights impacts in the apparel industry, including those pertaining to child labour.

- The Partnership for Sustainable Textiles, Bündnisziele: Sozialstandards (German) : The Partnership for Sustainable Textiles — a multi-stakeholder initiative with about 135 members from business, Government, civil society, unions, and standards organizations — has formulated social goals , including on child labour, that all members recognize by joining the Partnership.

- Green Button : Certification label for sustainable textiles run by the German Government with ban on forced and child labour as one of the certification criteria.

Mining and the Extractive Industry

Child labour takes place in parts of the informal artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) industry and has been associated with the mining of “ conflict minerals ” — tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold — among other minerals such as cobalt. ASM work can be dangerous and personal protective equipment (PPE) is rarely provided. The US Department of Labor’s 2022 report suggests that gold, coal, granite, gravel, diamonds and mica are all associated with child labour.

Mining-specific risk factors include the following:

- Small and slight: Children are often involved in digging as they can get into tighter spaces to mine, or in carrying mined products like gems or metals between extraction sites and refining/washing/filtering sites.

- Global supply chains: Minerals mined by children can end up in global supply chains, including those of automobiles, construction, cosmetics, electronics, and jewellery. For example, the increased production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries has led to the growing demand for cobalt — an essential battery input. Approximately 70% of cobalt (as of January 2023) comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), one of the poorest and most unstable countries in the world where ASM activity is common, thus increasing child labour risks .

- OECD, Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas : The OECD guidance identifies the worst forms of child labour as a serious human rights abuse associated with the extraction, transport or trade of minerals. The guidance has practical actions for companies to identify and address the worst forms of child labour in mineral supply chains and conduct related due diligence.

- OECD, Practical actions for companies to identify and address the worst forms of child labour in mineral supply chains : This report has been designed for companies to help them identify, mitigate and account for the risks of child labour in their mineral supply chains.

- ILO, Child Labour in Mining and Global Supply Chains : This brief report outlines the scope of child labour in ASM, risks to children’s health and welfare, and recommendations for businesses on addressing this issue.

- ILO, Mapping Interventions Addressing Child Labour and Working Conditions in Artisanal Mineral Supply Chains : This report provides a high-level review of projects and initiatives that aim to address child labour in the ASM sector across different minerals.

- UNICEF, Child Rights and Mining Toolkit: Best Practices for Addressing Children’s Issues in Large-Scale Mining : This toolkit is designed to help industrial miners design and implement social and environmental strategies (from impact assessment to social investment) that respect and advance children’s rights, including the elimination of child labour.

- SOMO, Global Mica Mining and the Impact on Children’s Rights : This report outlines mica production globally and identifies direct or indirect links to child labour.

- SOMO, Beauty and a Beast: Child Labour in India for Sparkling Cars and Cosmetics : This report focuses on illegal mica mining in India. It outlines the due diligence actions of several multinational companies and provides further recommendations for mica mining, processing and/or using companies.

- Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Responsible Jewellery Council Standards Guidance : This guidance provides a suggested approach for RJC members to implement the mandatory requirements of the RJC Code of Practice (COP), including the elimination of child labour in mining operations.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries : This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with child labour. Responsible Minerals Initiative also has other helpful resources for mining companies on various steps of human rights due diligence.

- UNICEF, Extractive Pilot – Children’s Rights in the Mining Sector : This report seeks to understand the the impacts of the mining industry on children’s rights and facilitate the integration of children’s rights into companies’ human rights due diligence processes.

Electronics Manufacturing

The electronics manufacturing industry poses child labour risks, as well as risks for young workers.

Industry-specific risk factors include the following:

- Work experience: In several Asian and South-East Asian countries, there are government programmes with major businesses for students and young workers to get work experience. However, there are reports of these programmes being abused, with student and young workers having their IDs faked so they can work longer and more hazardous hours.

- Materials: Electronics companies may be linked to child labour via their mineral supply chains given that some of the minerals and metals used to manufacture electronic components can be associated with significant child labour risks (i.e. during the mining process), such as gold — see the section on mining.

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), Student Workers Management Toolkit : This toolkit helps human resources and other managers support responsible recruitment and management of student workers in electronics manufacturing.

- Responsible Minerals Initiative, Material Change: A Study of Risks and Opportunities for Collective Action in the Materials Supply Chains of the Automotive and Electronics Industries : This report examines responsible sourcing of materials in the automotive and electronics industries, including association with child labour.

- SOMO, Gold from Children’s Hands: Use of Child-Mined Gold by the Electronics Sector : This report outlines the magnitude and seriousness of child labour in the artisanal gold mining sector and provides insight into the supply chain linkages with the electronics industry.

Travel and Tourism

Businesses in the travel and tourism industry (e.g. hotels, restaurants and tour companies) may be linked to the risks of child labour and has significant risks of facilitating child trafficking, particularly in the aviation industry.

Travel and tourism-specific risk factors include the following:

- Developing countries: Children in developing countries are often put to work selling tourist gifts or supporting family businesses like restaurants. Although this type of work is acceptable for children — provided that it is not hazardous and does not prevent them from receiving an education — it may also constitute child labour if it does preclude children’s school attendance.

- Child sexual exploitation: Child sex tourism does exist, and the trafficking or use of children for sexual activities for tourists occurs around the world.

Businesses in other sectors that use travel and tourism services as part of their business activities or in their supply chains may also be linked to child exploitation.

- ILO, Guidelines on Decent Work and Socially Responsible Tourism : These guidelines provide practical information for developing and implementing policies and programmes to promote sustainable tourism and strengthen labour protection, including the protection of children from exploitation.

- ChildSafe Movement and G Adventures Inc, Child Welfare and the Travel Industry: Global Good Practice Guidelines : These guidelines provide information on child welfare issues throughout the travel industry, as well as guidance for businesses on preventing all forms of exploitation and abuse of children that could be related to the tourism industry.

- International Tourism Partnership, The Know How Guide: Human Rights and the Hotel Industry : This guide provides an overview of human rights (including child labour) within hospitality, with guidance on developing a human rights policy, performing due diligence and addressing any adverse human rights impacts.

Due Diligence Considerations

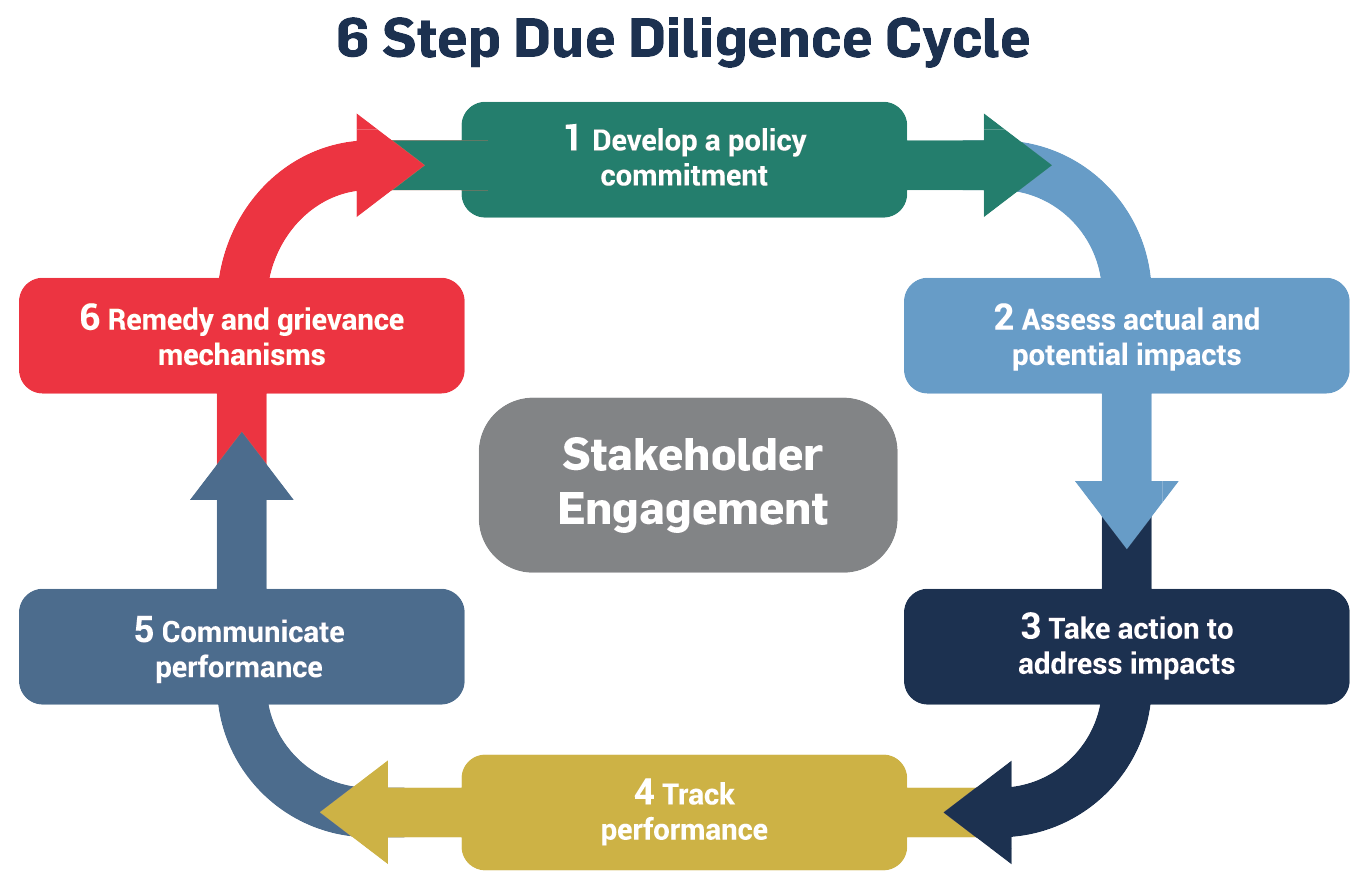

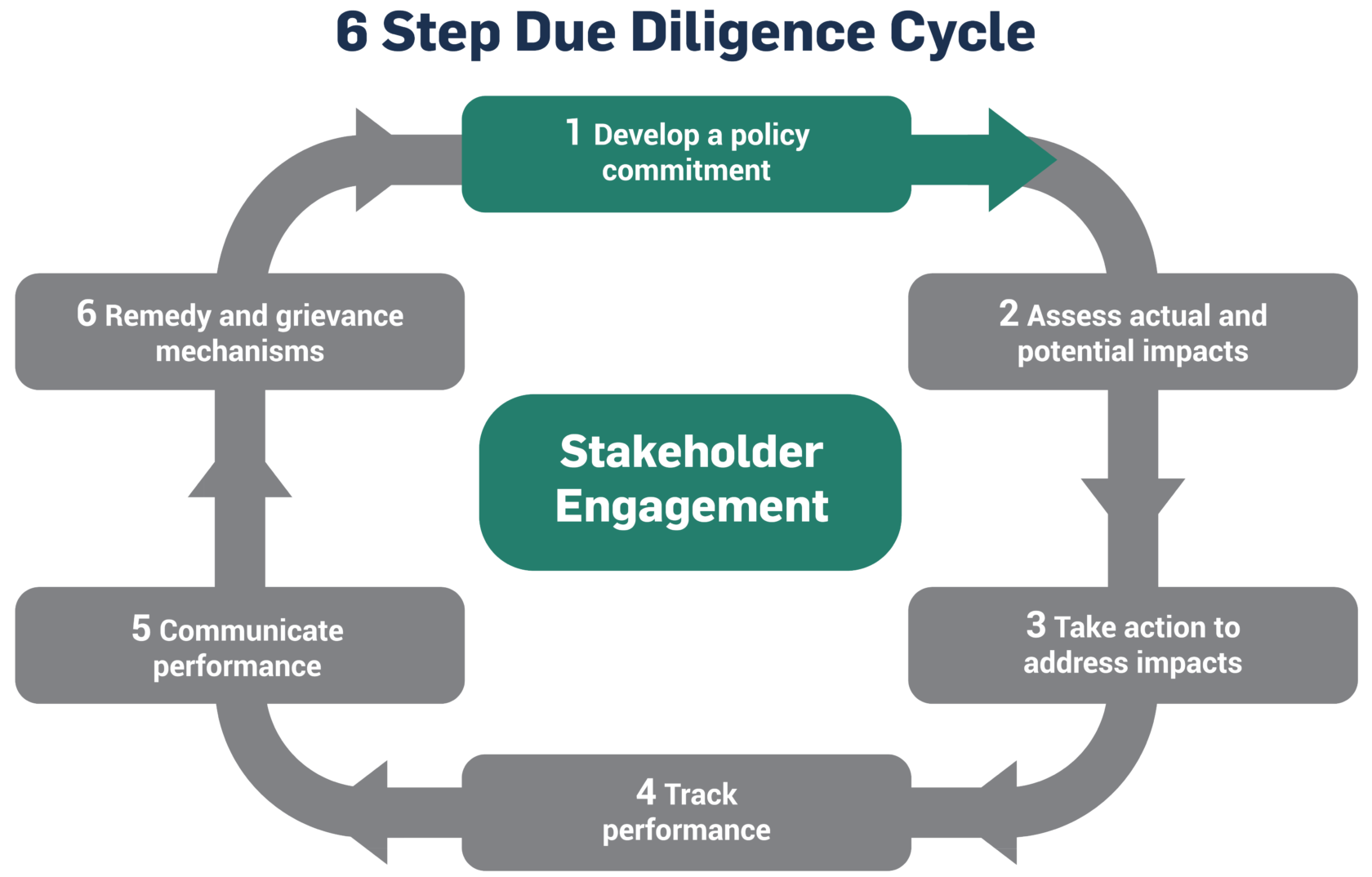

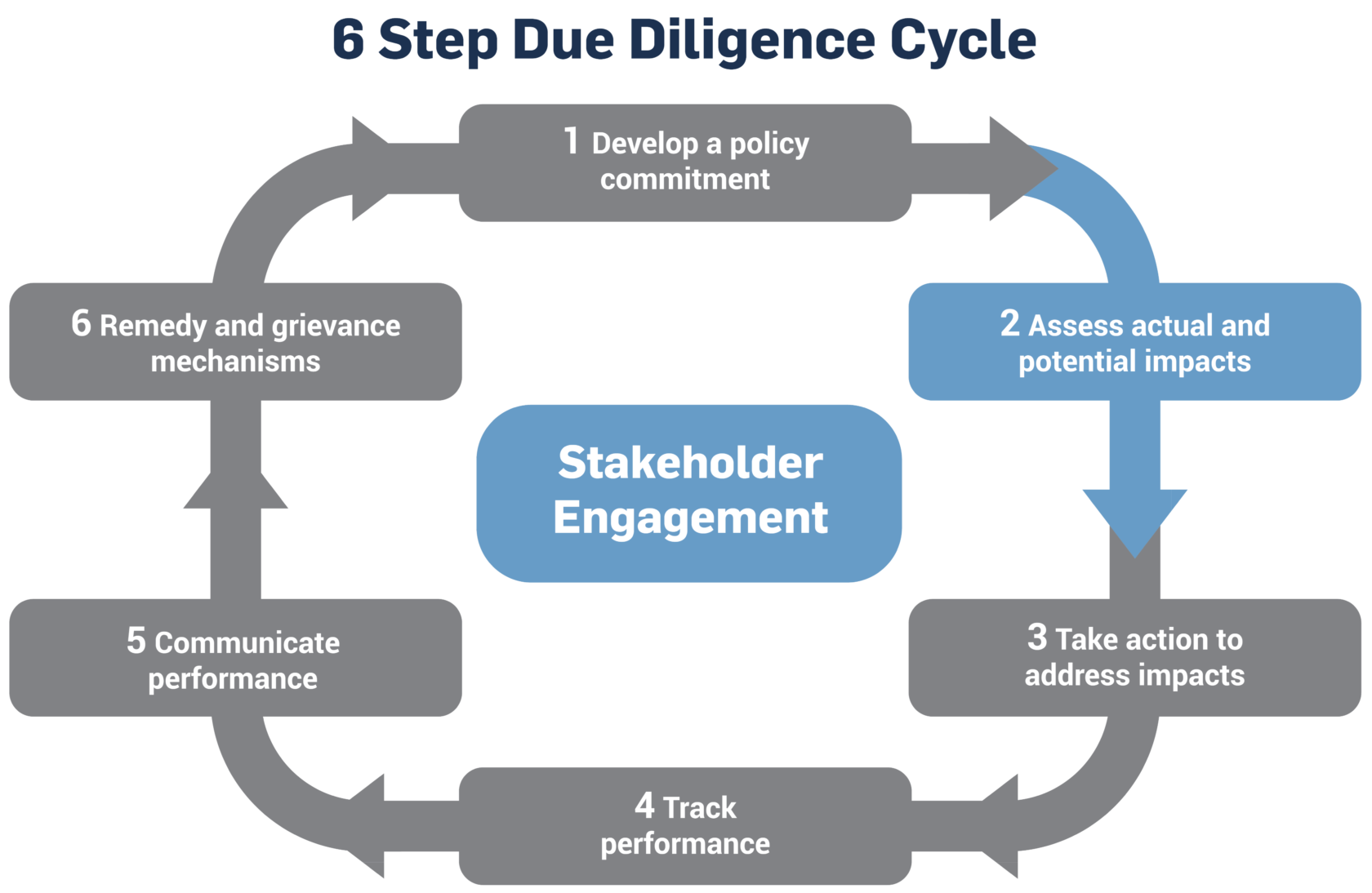

This section outlines due diligence steps that companies can take to eliminate child labour in their operations and supply chains. The described due diligence steps are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ( UNGPs ). Further information on UNGPs is provided in the ‘Key Human Rights Due Diligence Frameworks’ section below or in the Introduction .

While the below steps provide guidance on eliminating child labour in particular, it is generally more resource-efficient for companies to ‘streamline’ their human rights due diligence processes by also identifying and addressing other relevant human rights issues (e.g. forced labour , discrimination , freedom of association ) at the same time.

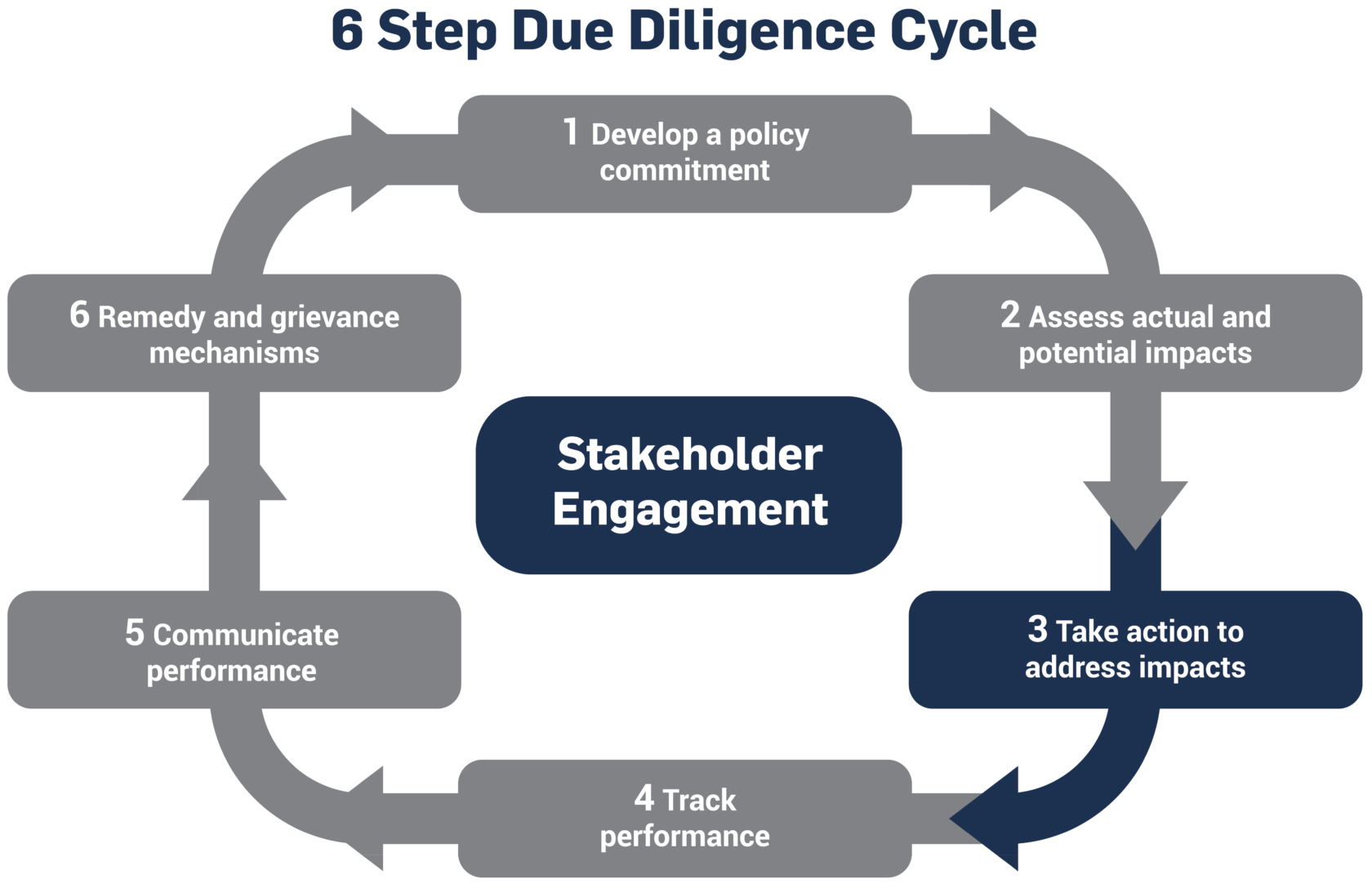

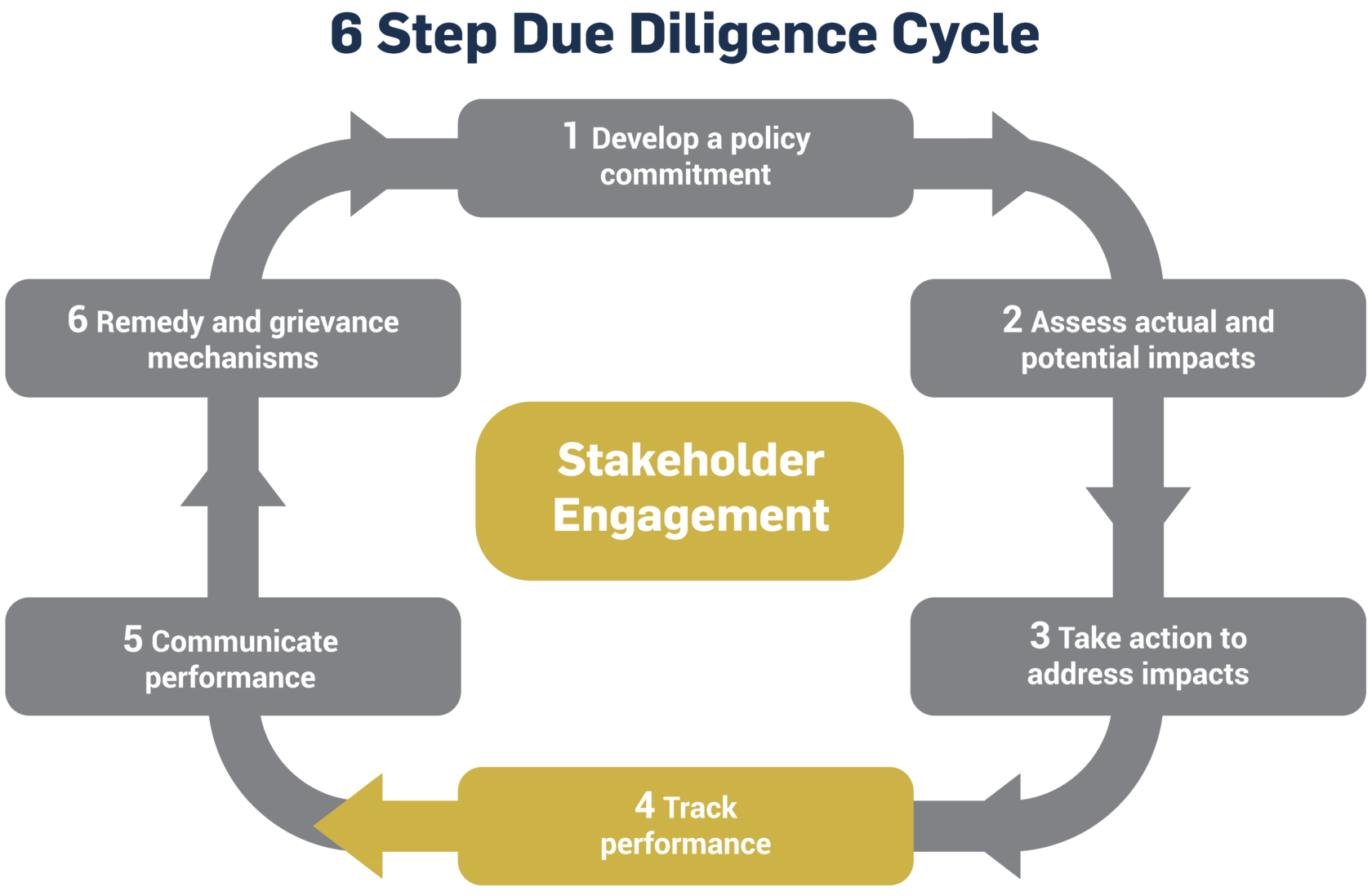

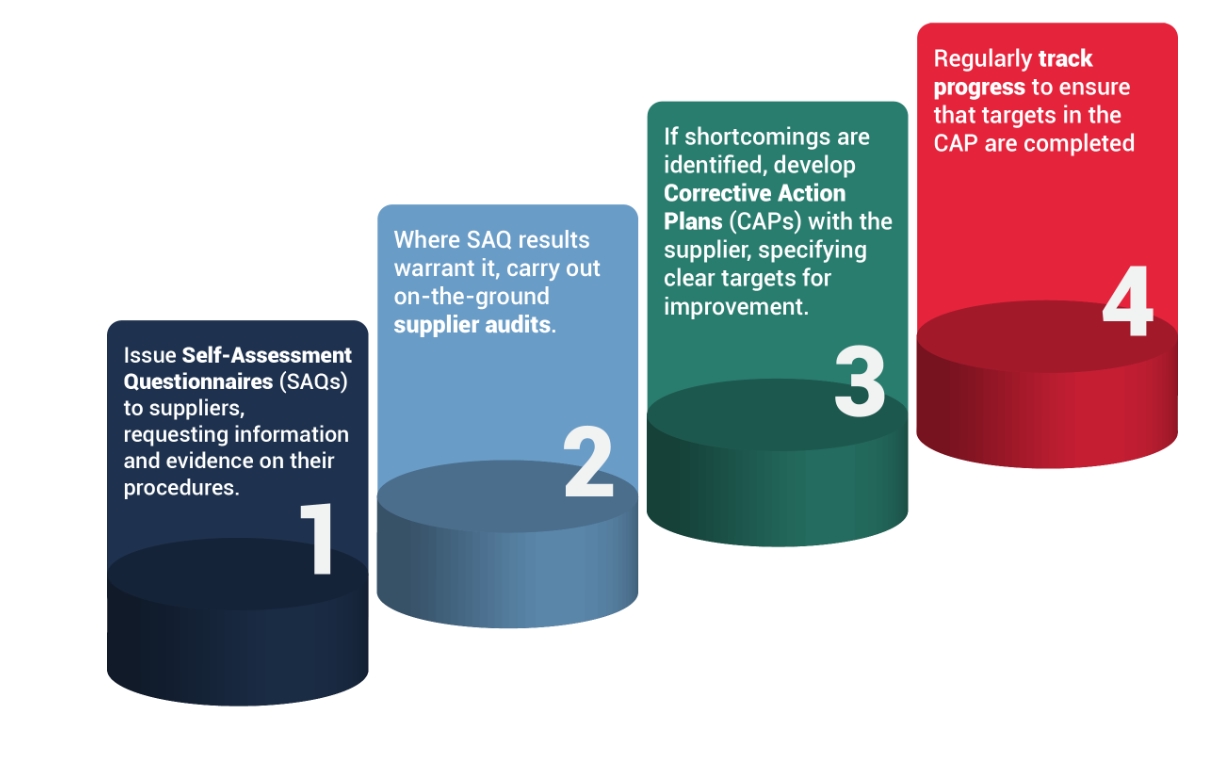

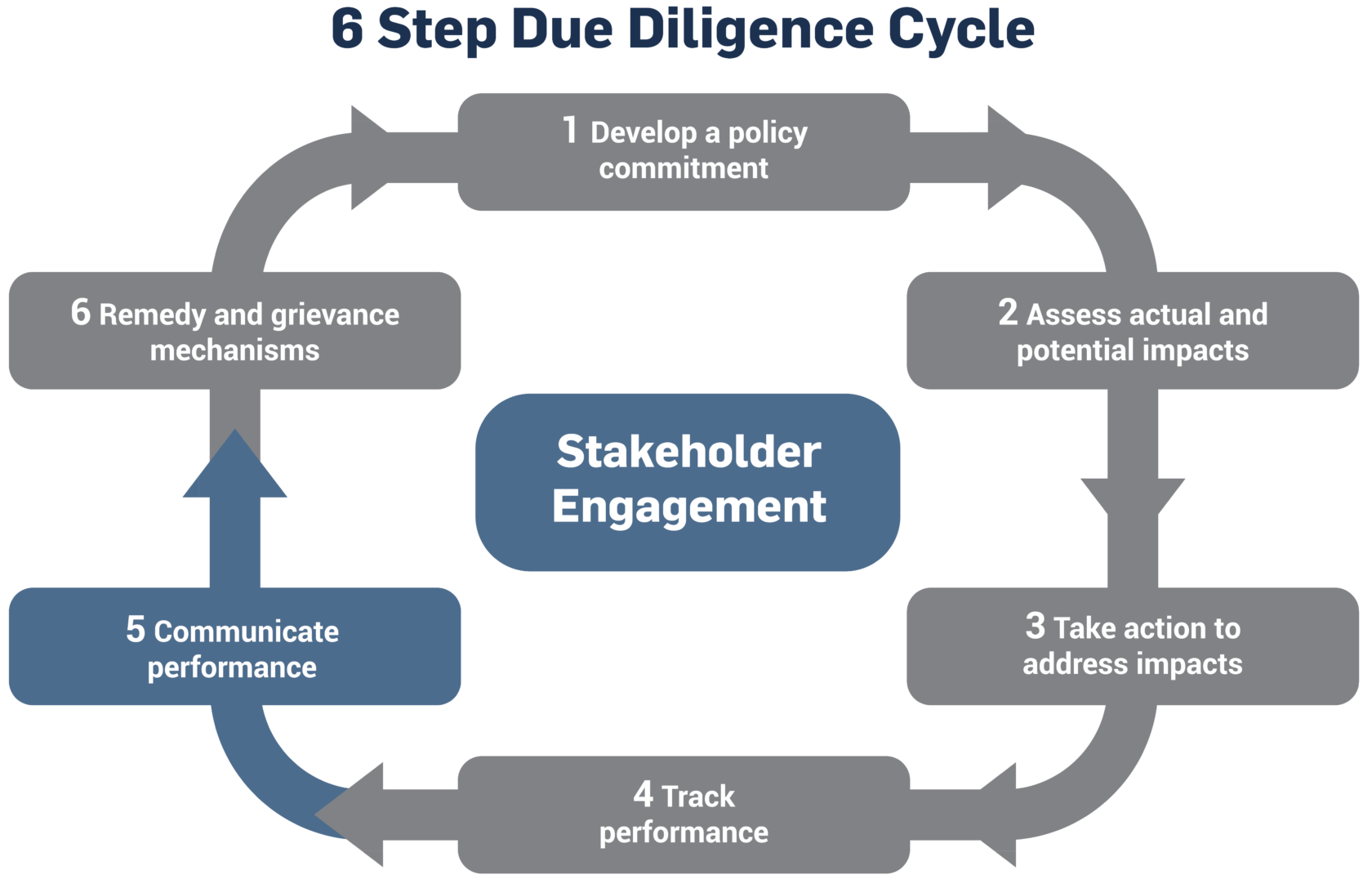

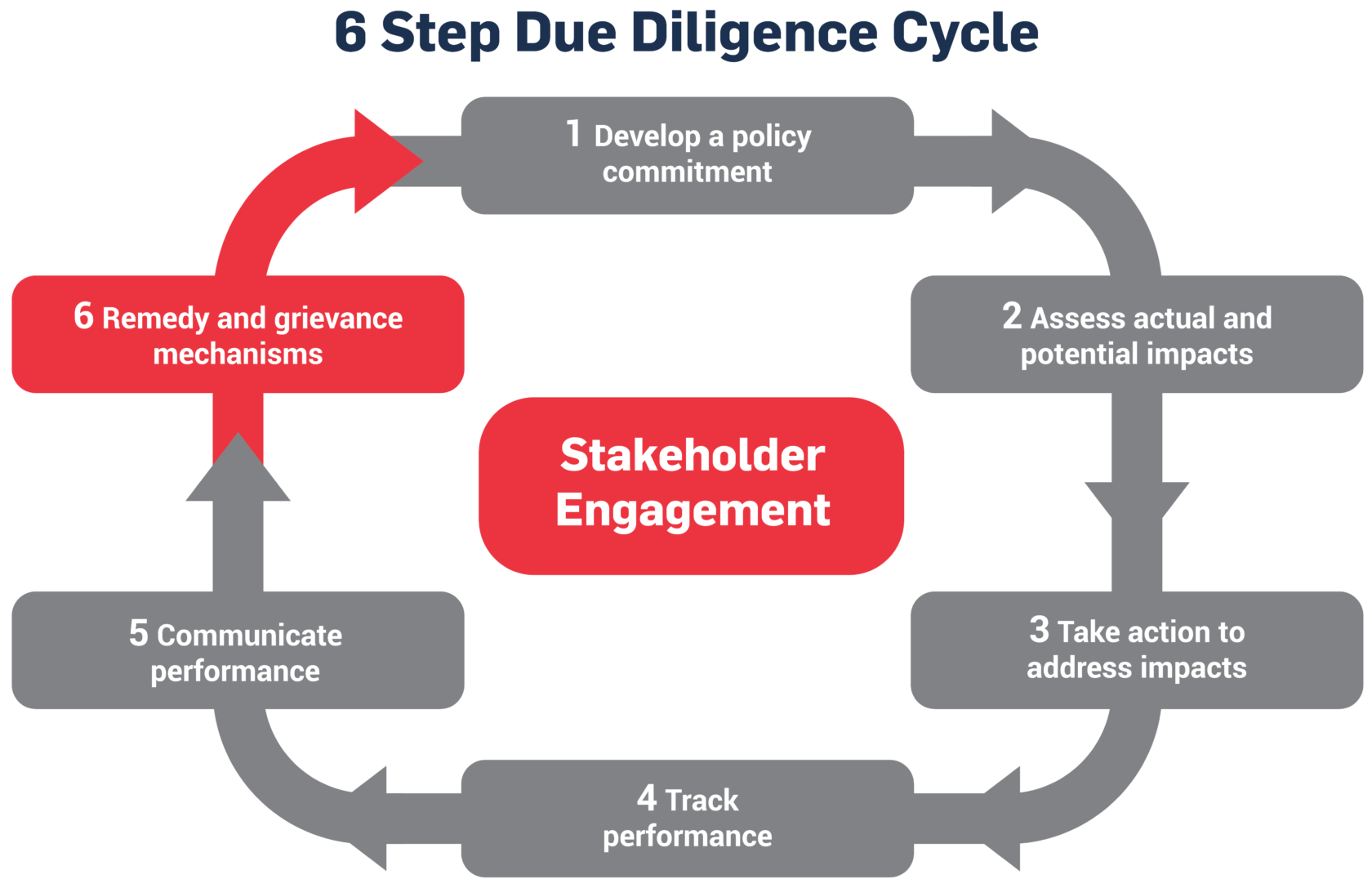

Several human rights frameworks describe the due diligence steps that businesses should ideally implement to address human rights issues, including forced labour. The primary framework is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ( UNGPs ) . Launched in 2011, the UNGPs offer guidance on how to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework, which establishes the respective responsibilities of Governments and businesses — and where they intersect.

The UNGPs set out how companies, in meeting their responsibility to respect human rights, should put in place due diligence and other related policies and process, which include:

- A publicly available policy setting out the company’s commitment to respect human rights;

- Assessment of any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved across its entire value chain;

- Integration of the findings from their impact assessments into relevant internal functions/processes — and the taking of effective action to manage the same;

- Tracking of the effectiveness of the company’s management actions;

- Reporting on how the company is addressing its actual or potential adverse impacts; and

- Remediation of adverse impacts that the company has caused or contributed to.

The steps outlined below follow the UNGPs framework and can be considered a process which a business looking to start implementing human rights due diligence processes can follow.

Additionally, the Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBPs) were based on the UNGPs as the first comprehensive set of principles to guide companies on the due diligence steps they can take to respect children’s rights in the workplace, marketplace and community.

The OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises further define the elements of responsible business conduct, including human and labour rights.

Another important reference document is the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy ( MNE Declaration ), which contains the most detailed guidance on due diligence as it pertains to labour rights. These instruments, articulating principles of responsible business conduct, draw on international standards enjoying widespread consensus.

Companies can seek specific guidance on this and other issues relating to international labour standards from the ILO Helpdesk for Business . The ILO Helpdesk assists company managers and workers who want to align their policies and practices with principles of international labour standards and build good industrial relations. It has a specific section on forced labour .

Additionally, the SME Compass offers guidance on the overall human rights due diligence process by taking businesses through five key due diligence phases. The SME Compass has been developed in particular to address the needs of SMEs but is freely available and can be used by other companies as well. The tool, available in English and German , is a joint project by the German Government’s Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

1. Develop a Policy Commitment to Help Eliminate Child Labour

As per the UNGPs , a human rights policy should be:

- “Approved at the most senior level” of the company;

- “Informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise”;

- Specific about company’s “human rights expectations of personnel, business partners and other parties directly linked to its operations, products or services”;

- “Publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties”; and

- “Reflected in operational policies and procedures necessary to embed it throughout the business”.

Research of 2,500 companies across nine industries conducted by the Global Child Forum suggests that 57% of companies have some form of stand-alone policy against child labour. Examples of companies with stand-alone child labour policies include ALDI South, H&M and ASOS. These tend to be companies that have identified child labour as a highly salient issue.

Another option is to integrate child labour commitments into companies’ wider human rights policy, an option that has been taken by Unilever, Marks and Spencer and Freeport-McMoRan. Where companies do not have a human rights policy, child labour is often addressed in other policy documents, such as a business code of conduct or ethics and/or a supplier code of conduct. Starbucks, BHP and HP offer examples of multinational companies that integrate child labour requirements into their codes of conduct. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), such as Haas & Co. Magnettechnik GmbH, also often include child labour in their business code of conduct or supplier code of conduct.

Businesses may want to check the ILO Helpdesk for Business, which provides answers to the most common questions that businesses may encounter while developing their child labour policies — or integrating child labour commitments into other policy documents. Examples include:

- I am trying to figure out why the basic minimum age is set at 15 or 14. What would be the consequences of setting a global policy with a basic minimum age at 16?

- A company is committed to not recruiting people below 18 years old, but the company operates in States where people below 18 have the right to work. Can it be considered as a breach of ILO Conventions related to discrimination?

- What are the general recommendations concerning apprenticeships to use when clarifying our child labour requirements to our suppliers?

Businesses may also consider aligning their policies with relevant industry-wide or cross-industry policy commitments, for example:

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) Code of Conduct

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) Base Code

- amfori BSCI Code of Conduct

- Fair Labor Association (FLA) Code of Conduct

- The Code of Conduct for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation in Travel and Tourism initiated by ECPAT, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and several tour operators