Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Refers to notes created by the researcher during the act of conducting a field study to remember and record the behaviors, activities, events, and other features of an observation. Field notes are intended to be read by the researcher as evidence to produce meaning and an understanding of the culture, social situation, or phenomenon being studied. The notes may constitute the whole data collected for a research study [e.g., an observational project] or contribute to it, such as when field notes supplement conventional interview data or other techniques of data gathering.

Schwandt, Thomas A. The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015.

How to Approach Writing Field Notes

The ways in which you take notes during an observational study is very much a personal decision developed over time as you become more experienced in fieldwork. However, all field notes generally consist of two parts:

- Descriptive information , in which you attempt to accurately document factual data [e.g., date and time] along with the settings, actions, behaviors, and conversations that you observe; and,

- Reflective information , in which you record your thoughts, ideas, questions, and concerns during the observation.

Note that field notes should be fleshed out as soon as possible after an observation is completed. Your initial notes may be recorded in cryptic form and, unless additional detail is added as soon as possible after the observation, important facts and opportunities for fully interpreting the data may be lost.

Characteristics of Field Notes

- Be accurate . You only get one chance to observe a particular moment in time so, before you conduct your observations, practice taking notes in a setting that is similar to your observation site in regards to number of people, the environment, and social dynamics. This will help you develop your own style of transcribing observations quickly and accurately.

- Be organized . Taking accurate notes while you are actively observing can be difficult. Therefore, it is important that you plan ahead how you will document your observation study [e.g., strictly chronologically or according to specific prompts]. Notes that are disorganized will make it more difficult for you to interpret the data.

- Be descriptive . Use descriptive words to document what you observe. For example, instead of noting that a classroom appears "comfortable," state that the classroom includes soft lighting and cushioned chairs that can be moved around by the students. Being descriptive means supplying yourself with enough factual evidence that you don't end up making assumptions about what you meant when you write the final report.

- Focus on the research problem . Since it's impossible to document everything you observe, focus on collecting the greatest detail that relates to the research problem and the theoretical constructs underpinning your research; avoid cluttering your notes with irrelevant information. For example, if the purpose of your study is to observe the discursive interactions between nursing home staff and the family members of residents, then it would only be necessary to document the setting in detail if it in some way directly influenced those interactions [e.g., there is a private room available for discussions between staff and family members].

- Record insights and thoughts . As you take notes, be thinking about the underlying meaning of what you observe and record your thoughts and ideas accordingly. If needed, this will help you to ask questions or seek clarification from participants after the observation. To avoid any confusion, subsequent comments from participants should be included in a separate, reflective part of your field notes and not merged with the descriptive notes.

General Guidelines for the Descriptive Content

The descriptive content of your notes can vary in detail depending upon what needs to be emphasized in order to address the research problem. However, in most observations, your notes should include at least some of the following elements:

- Describe the physical setting.

- Describe the social environment and the way in which participants interacted within the setting. This may include patterns of interactions, frequency of interactions, direction of communication patterns [including non-verbal communication], and patterns of specific behavioral events, such as, conflicts, decision-making, or collaboration.

- Describe the participants and their roles in the setting.

- Describe, as best you can, the meaning of what was observed from the perspectives of the participants.

- Record exact quotes or close approximations of comments that relate directly to the purpose of the study.

- Describe any impact you might have had on the situation you observed [important!].

General Guidelines for the Reflective Content

You are the instrument of data gathering and interpretation. Therefore, reflective content can include any of the following elements intended to contextualize what you have observed based on your perspective and your own personal, cultural, and situational experiences .

- Note ideas, impressions, thoughts, and/or any criticisms you have about what you observed.

- Include any unanswered questions or concerns that have arisen from analyzing the observation data.

- Clarify points and/or correct mistakes and misunderstandings in other parts of field notes.

- Include insights about what you have observed and speculate as to why you believe specific phenomenon occurred.

- Record any thoughts that you may have regarding any future observations.

NOTE: Analysis of your field notes should occur as they are being written and while you are conducting your observations. This is important for at least two reasons. First, preliminary analysis fosters self-reflection and self-reflection is crucial for facilitating deep understanding and meaning-making in any research study. Second, preliminary analysis reveals emergent themes. Identifying emergent themes while observing allows you to shift your attention in ways that can foster a more developed investigation.

Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gambold, Liesl L. “Field Notes.” In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Edited by Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos, and Elden Wiebe. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports. Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Ravitch, Sharon M. “Field Notes.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation . Edited by Bruce B. Frey. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2018; Tenzek, Kelly E. “Field Notes.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods . Edited by Mike Allen. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2017; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

- << Previous: About Informed Consent

- Next: Writing a Policy Memo >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Introduction to Fieldwork in Social Work

- First Online: 22 March 2024

Cite this chapter

- M. Rezaul Islam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2217-7507 2

122 Accesses

This chapter serves as a foundational exploration of fieldwork in the context of social work practice. It begins by elucidating the concept of fieldwork, offering a comprehensive understanding of its nature and significance within the social work profession. The chapter delves into the multifaceted role that fieldwork plays in the development and application of social work skills, emphasizing its practical and experiential dimensions. Various types of fieldwork in social work practice are systematically examined, shedding light on the diverse settings and scenarios in which social work interventions take place. The chapter underscores the importance of fieldwork as a transformative component of social work education and professional development. It explores the symbiotic relationship between theoretical knowledge and hands-on experience, emphasizing the dynamic and enriching nature of fieldwork. An innovative framework, the EARIS (Exploration, Reflection, Integration, and Synthetization) Formula, is introduced to guide social work students in preparing for field practice. This formula provides a structured approach for students to navigate the challenges and opportunities inherent in fieldwork. Recognizing the emotional and psychological dimensions of fieldwork, the chapter addresses the social and mental preparation required for effective engagement in fieldwork practice. It explores strategies to enhance resilience, self-awareness, and cultural competence, emphasizing the importance of preparing social work students for the dynamic and diverse nature of fieldwork.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Baikady, R., Nadesan, V., Sajid, S. M., & Islam, M. R. (2022). Introduction: New directions to field work education in social work: A global south perspective. In The Routledge handbook of social work field education in the global south (pp. 1–10). Routledge.

Google Scholar

DeGroot, J. N. (2019). Bachelor of social work students experiences: Understanding learning needs (Doctoral dissertation, Capella University).

Dhemba, J. (2012). Fieldwork in social work education and training: issues and challenges in the case of Eastern and Southern Africa. Social Work & Society, 10 (1), 1–16.

Doel, M., Shardlow, S. M., Shardlow, S., & Johnson, P. G. (2010). Contemporary field social work: Integrating field and classroom experience . .

Hamilton, N., & Else, J. F. (1983). Designing field education: Philosophy, structure, and process . Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

Hay, K., & O’Donoghue, K. (2009). Assessing social work field education: Towards standardising fieldwork assessment in New Zealand. Social Work Education, 28 (1), 42–53.

Article Google Scholar

Ivry, J., Lawrance, F. P., Damron-Rodriguez, J., & Robbins, V. C. (2005). Fieldwork rotation: A model for educating social work students for geriatric social work practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 41 (3), 407–425.

Kaseke, E. (1986). The role of fieldwork in social work training. In Social Development and Rural Fieldwork. Proceedings of a workshop held in Harare. Harare, Journal of Social Development in Africa (pp. 52–62).

Pawar, M. (2017). Reflective learning and teaching in social work field education in international contexts. The British Journal of Social Work, 47 (1), 198–218.

Roy, S. (2017). Field work practice in correctional settings: Indian social work perspective. Global Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2 (1), 001–008.

Safari, J. (1986, June). The role of fieldwork in the training of social workers for rural development in: Social development and rural fieldwork. In Proceedings of a Workshop held (Vol. 10, No. 14, pp. 74-80).

Singla, P. R. (2015). Fieldwork as signature pedagogy of social work education: As I see it. Social Work Journal, 6 (1), 90–102.

Smith, D., Cleak, H., & Vreugdenhil, A. (2015). “What are they really doing?” An exploration of student learning activities in field placement. Australian Social Work, 68 (4), 515–531.

Sunirose, I. P. (2013). Fieldwork in social work education: Challenges, issues and best practices. Rajagiri Journal of Social Development, 5 (1), 48–56.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

M. Rezaul Islam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Review Questions

What is the significance of social and mental preparation before engaging in fieldwork?

How can the EARIS formula benefit social work students in preparing for field practice?

Why is setting clear objectives essential for effective fieldwork?

In what ways does fieldwork contribute to the overall development of social work students?

Explain the importance of ethical considerations and principles in the preparation phase of fieldwork.

Multiple Choice Questions

What is the significance of fieldwork in social work for professional development?

It is optional for social work students.

It has no impact on professional growth.

It is crucial for gaining practical experience and skills.

It is primarily for academic research.

How can the EARIS formula be applied in the context of fieldwork practice?

It guides social work students in preparing for fieldwork.

It is not applicable to social work.

It is a formula for personal fitness.

It is related to financial planning.

Why is social and mental preparation important before engaging in fieldwork?

It contributes to effective engagement and coping in fieldwork.

It has no impact on fieldwork outcomes.

It helps in avoiding fieldwork altogether.

It is only relevant for experienced social workers.

What role do clear objectives play in fieldwork?

They are unnecessary in social work.

They hinder the learning process.

They are only for academic purposes.

They provide a roadmap for effective fieldwork.

It has no impact on development.

It only focuses on theoretical knowledge.

It provides practical experience, skill development, and professional growth.

It is solely for academic credit.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Islam, M.R. (2024). Introduction to Fieldwork in Social Work. In: Fieldwork in Social Work. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56683-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56683-7_2

Published : 22 March 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-56682-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-56683-7

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

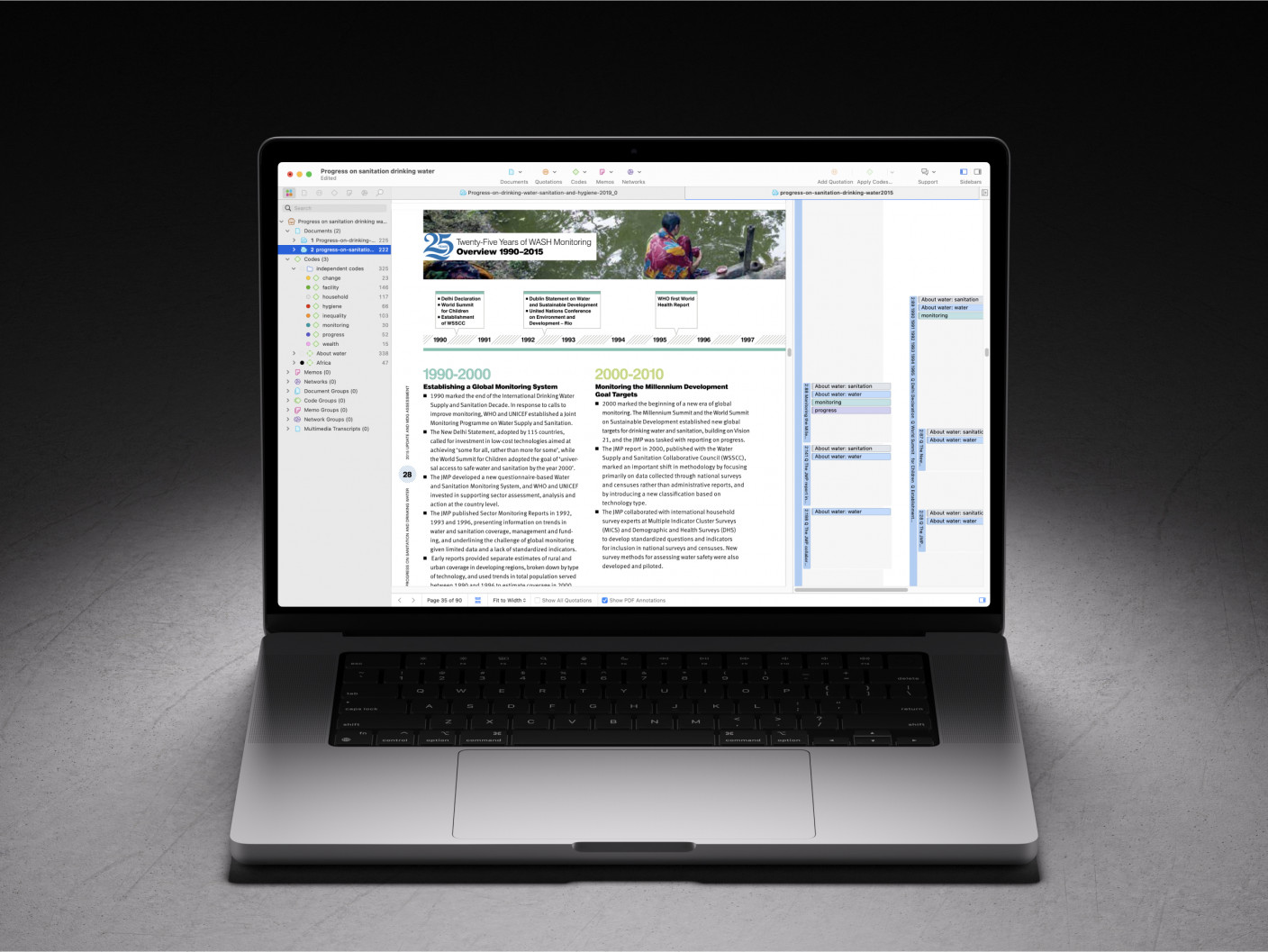

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Handling qualitative data

- Transcripts

- Introduction

What are field notes?

Understanding field notes, constructing field notes, how to approach writing field notes, considerations for qualitative data analysis.

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

- Narrative research

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative data analysis software

Field notes in research

Field notes are the centerpiece of observational research . Transcripts can document what was said in interviews , focus groups , or recorded observations. Still, to turn social practices, cultural rituals, and non-verbal communication into qualitative data , researchers typically turn to field notes to provide a detailed description of what they see.

Let's look at how field notes figure into qualitative research as well as some challenges and considerations when incorporating field notes into research.

Field notes are an integral part of many types of research, especially within qualitative inquiry. Essentially, field notes are the researcher's written record of observations made, experiences had, and insights gleaned while in the field conducting research.

Whereas qualitative interviewing seeks out perspectives and beliefs from research participants , notes are useful for documenting what research participants do and how they behave in social practice. Notes from observations serve as the first point of contact with the data to be analyzed. They are a fundamental resource for understanding the context, nuances, and complexities of the research setting.

Field notes are not objective descriptions, nor is the primary goal always to completely and accurately document factual data; they also contain the researcher's interpretations and reflections on what has been observed . This gives field notes their dual nature - they are both descriptive and reflective, painting a comprehensive picture of the phenomena under study.

At their core, field notes seek to capture the rich and complex world of human experience in a form that can be communicated to others and used for qualitative data analysis. They provide the essential raw material from which researchers can develop an understanding of the people, practices, and cultures they are studying.

What do you write in your field notes?

Field notes should capture a broad array of information, including what was seen, heard, felt, and thought during the course of research. In essence, they are a record of your sensory and intellectual experiences in the field. The information can include descriptions of people, actions, and interactions. You can also mention your own thoughts, questions, and ideas as they arise in response to what you're observing in our field notes.

Field notes may also include sketches, diagrams, or other visual materials that aid in capturing the research setting. Furthermore, they may detail any particular incidents, events, or situations that you find noteworthy or that illustrate the phenomena you're investigating.

What is the purpose of a field note?

The primary purpose of a field note is to create a comprehensive and nuanced record of the research setting and the phenomena being investigated. Field notes serve as the raw material for analysis , allowing researchers to revisit their observations, reflect upon them, and derive meaningful insights and interpretations . They also help in providing a level of detail and context about the setting and participants that would be difficult to recall accurately from memory alone.

Moreover, field notes also serve an important role in grounding the research in the lived experiences and realities of the people being studied. By capturing not just what is said but also the ways in which it is said, the interactions between individuals, and the context in which these interactions take place, field notes help ensure that the resulting analysis and conclusions are rooted in the real-world experiences of the research subjects.

The value of field notes in qualitative research

In qualitative research methods for data collection , field notes play a critical role as they capture the rich, complex, and nuanced data that characterize this form of inquiry. They are instrumental in helping researchers understand and interpret the social world from the perspective of the individuals being studied.

Through field notes, researchers can capture the subtleties and complexities of human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices, making them an indispensable tool in qualitative research. As a result, many research disciplines employ field notes in data collection. In communication research, methods for documenting observations through notes focus on how information is conveyed and negotiated between different speakers. Field notes serve an important purpose in analyzing social settings for research in anthropology and sociology, as well. In general, descriptive notes from qualitative observation can aid a qualitative researcher in identifying emergent themes about behaviors and actions seen during the course of a research study.

Analysis of ideas, actions, and values made possible with ATLAS.ti.

Turn your data into key insights with our powerful tools. Download a free trial today.

What should field notes include?

These notes should be comprehensive, capturing a range of information that covers both descriptive and reflective aspects of the field research experience.

Descriptive content includes detailed accounts of the physical setting, the people involved, the activities and interactions observed, and the nonverbal cues and behaviors noticed. Researchers might also note down direct quotations from participants that seem significant or representative of common themes.

Reflective content, on the other hand, includes the researcher's thoughts, feelings, reactions, and initial interpretations related to what's being observed. This might encompass speculations, feelings, problems, ideas, hunches, impressions, and prejudices.

Beyond these, researchers often find it helpful to include methodological notes (information about the research process) and demographic information about the people being observed.

Elements of a comprehensive field note

A comprehensive field note typically includes these elements:

1. Headnotes: These include the date, time, location, and other context-setting details of the observation period.

2. Descriptive observations: A detailed description of the physical setting, the participants, activities, and conversations.

3. Reflective notes: Personal reflections that reveal thoughts, ideas, concerns, or preliminary analysis about what is being observed.

4. Sketches and diagrams: Visual representations can be useful for depicting spatial relationships, layouts, or intricate details of observed objects.

5. Analytical insights: Early propositions or interpretations based on what is being observed.

6. Methodological notes: Information about any changes in research plans, the rationale for decisions, and lessons learned for future fieldwork.

The intersection of observation and note-taking

The process of taking notes goes hand-in-hand with observation in qualitative research . The researcher, while being a keen observer, should also be a diligent note-taker, translating observations into detailed and comprehensive notes. This dual role requires practice and skill. Balancing observation and note-taking can maximize the richness of the data collected, allowing for a deep and nuanced understanding of the phenomena under study.

Field note writing is not a task that is undertaken only after fieldwork. Rather, it is an ongoing process that spans the duration of the research project. From the preparation stage to time spent in the field, and finally, reflecting upon and refining your notes, there are different aspects to consider at each stage.

Preparation before field visits

Before you start your fieldwork, it is important to get familiar with the note-taking process. This could require you to practice taking notes in everyday situations. Taking accurate notes is not necessarily the main goal as long as these notes reflect your thinking about what you see. Still, note-taking should be guided by the research question or theoretical constructs underpinning your research study.

There are few strict prescriptions for taking notes while in the field; the advice presented here is aimed at giving the researcher guidance about how to collect useful data for later analysis . Rather than present some hard and fast rules about field note writing, let's close this section with two particular considerations that can guide your research.

Triangulation is an important component of qualitative research . In the context of observation data , it is especially useful to contextualize themes uncovered during observations with analysis from other research methods. A more developed investigation, for example, might incorporate observations with interview research in order to triangulate research participants ' beliefs with actions.

Finally, while you may be tempted to try and document every particular event that occurs during an observation, it is unreasonable to expect the researcher to notice the smallest details or to argue that every particular detail is salient to a given research inquiry. As with interview and focus group research , all research methods should focus on collecting data that is relevant to the study and the research questions you are looking to address.

Analyze transcripts, notes, and more with ATLAS.ti

Intuitive tools to help you with your research. Check them out with a free trial of ATLAS.ti.

Organizing Academic Research Papers: Writing Field Notes

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

Refers to notes created by the researcher during the act of qualitative fieldwork to remember and record the behaviors, activities, events, and other features of an observation setting. Field notes are intended to be read by the researcher to produce meaning and an understanding of the culture, social situation, or phenomenon being studied. The notes may constitute the whole data collected for a research study [e.g., an observational project] or contribute to it, as when field notes supplement conventional interview data.

How to Approach Writing Field Notes

The ways in which you take notes during an observational study is very much a personal decision developed over time as one becomes more experienced in observing. However, all field notes generally consist of two parts:

- Descriptive information , in which you attempt to accurately document the factual data [e.g., date and time], settings, actions, behaviors, and conversations you observe; and,

- Reflective information , in which you record your thoughts, ideas, questions, and concerns as you are making your observations.

Field notes should be written as soon as possible after an observation is completed. Your initial notes may be recorded in cryptic form and, unless they are fleshed out as soon as possible after the observation, important details and opportunities for fully interpreting the data may be lost.

Characteristics of Field Notes

- Be accurate . You only get one chance to observe a particular moment in time, so practice taking notes before you conduct your observations. This will help you develop your own style of transcribing observations quickly and accurately.

- Be organized . Taking accurate notes while observing at the same time can be difficult. It is therefore important that you plan ahead of time how you will document your observation study [e.g., strictly chronologically or according to specific prompts]. Notes that are disorganized will make it more difficult to interpret your findings.

- Be descriptive . Use descriptive words to document what you observe. For example, instead of noting that a classroom appears "comfortable," state that the classroom includes soft lighting and cushioned chairs that can be moved around by the study participants. Being descriptive means supplying yourself with enough factual detail that you don't end up guessing about what you meant when you write the field report.

- Focus on the research problem . Since it's impossible to document everything you observe, include greatest detail on aspects of the research problem and the theoretical constructs underpinning your research; avoid cluttering your notes with irrelevant information. For example, if the purpose of your study is to observe the discursive interactions between nursing home staff and the family members of residents, then it would only be necessary to document the setting in detail if it in some way directly influenced those interactions [e.g., there is a private room available for discussions between staff and family members].

- Record insights and thoughts . As you observe, be thinking about the underlying meaning of what you observe and record your thoughts and ideas accordingly. Doing so will help should you want to subsequently ask questions or seek clarification from participants. To avoid any confusion, these comments should be included in a separate, reflective part of the field notes and not merged with the descriptive part of the notes.

General Guidelines for the Descriptive Content

- Describe the physical setting.

- Describe the social environment and the way in which participants interacted within the setting. This may include patterns of interactions, frequency of interactions, direction of communication patterns [including non-verbal communication], and decision-making patterns.

- Describe the participants and their roles in the setting.

- Describe, as best you can, the meaning of what was observed from the perspectives of the participants.

- Record exact quotes or close approximations of comments that relate directly to the purpose of the study.

- Describe any impact you might have had on the situation you observed [important!].

General Guidelines for the Reflective Content

- Note ideas, impressions, thoughts, and/or any criticisms you have about what you observed.

- Include any unanswered questions that have arisen from analyzing the observation data as well as thoughts that you may have regarding any future observations.

- Clarify points and/or correct mistakes and misunderstandings in other parts of field notes.

- Include insights about what you have observed and speculate as to why you believe specific phenomenon occurred.

NOTE : Analysis of your field notes should occur as they are being written and while you are conducting your observations. This is important for at least two reasons. First, preliminary analysis fosters self-reflection, and self-reflection is crucial for understanding and meaning-making in any research study. Second, preliminary analysis reveals emergent themes. Identifying emergent themes while observing allows you to shift your attention in ways that can foster a more developed investigation.

Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports . Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

- << Previous: About Informed Consent

- Next: Writing a Policy Memo >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

How to write field notes (and how to teach the writing of fieldnotes)

Writing is hard. And writing field notes is hard, too. I don’t think that there is enough guidance on how to do it. I’ve written about the use of ethnographic fieldnotes in scholarly written output , but I don’t think I had ever written about how to write fieldnotes and how to teach or learn on your own how to write better field notes.

Given my extensive experience as an ethnographer and fieldworker, I felt that it was important that I wrote a Twitter thread (which I am now converting into a blog post) on how to write field notes, along with references and citations that might be useful for people to read.

While there is literature on fieldwork (and field notes/fieldnotes, whichever spelling you prefer), and on ethnographic fieldwork, I feel like there’s never an “orientation” on how to write good field notes. Here’s a partial bibliography I compiled. https://t.co/Omp2JE2T3V — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Weirdly enough, I sometimes forget what I’ve published, particularly on qualitative methods. Well, here is an editorial I wrote on how you can use fieldnotes to prompt you to write, particularly when you’re feeling blocked. Pay attention to what I cite. https://t.co/oDBHjlw6gt — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Over the past three weeks, in my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation class, we have covered Coding, Theming and Writing Field Notes and Analytic Memorandums. These are classic components of qualitative text analylsis, and I discussed them in great depth. I believe that’s part and parcel of QDA.

But I want to emphasize what Maxwell 2013, p. 91 says: “there is no cookbook for qualitative methods”. I keep telling my students that qualitative analysis is extremely iterative. We try something, we code one way, see if it “sticks”, code another way, reframe, rethink. pic.twitter.com/Iv0j2eH8as — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

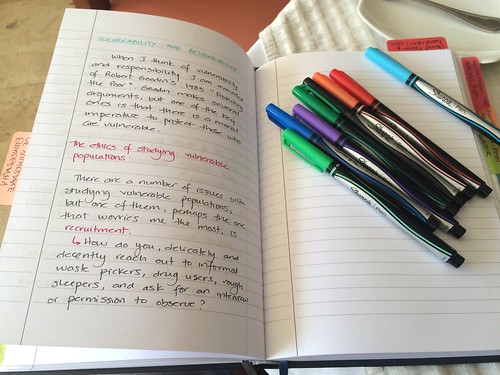

In my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation class, I went over what I believe is the core of a field note: I use a notebook, and on one side, I write my observations of whatever I am studying, alongside with the date and time. I make detailed notes (also noting on the left hand side of the page). Usually, the left hand side of the field notebook pages serves me to note my own emotions, the context, etc. This is not an uncommon approach (left hand side “emotions/context”, right hand side “phenomenon we are observing”) but others may use a different approach to mine.

As most of the respondents to my question of whether they would allow someone else to see and re-code their field notes noted, field notes are extremely personal, and may contain personal data that can be sensitive (all responses were AMAZING). https://t.co/KI3fuPcihL — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

But in my view, that’s also part of why it’s so hard to teach how to write good field notes: many/most of us may not be willing to show anybody else our field notes (for privacy/sensitivity issues, but also because they are primarily for us). And yes, despite good books on field notes.

… I have come to regain love for other three books: Sanjek https://t.co/KdT7W1PPuH Vivanco: https://t.co/WrGlNIw4jW Emerson, Fretz and Shaw: https://t.co/4LCAaxQ3Zv To note: ALL three books are excellent on the topic of ethnographic field notes. None disappoints. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Now, here’s the thing: you can teach how to write field notes, and how to write GOOD field notes, but then there’s the question of how do you write good ETHNOGRAPHIES ? As I have taught my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation students, my own personal bias is that a field note and an analytic memo are DIFFERENT .

Several authors agree with me (fieldnote is a record of my observations, analytic memo is a reflection of what I recorded in the fieldnote), including Saldaña 2013, p. 42, from where drew this quotation. Here’s my personal view (RPV): we need to teach GOOD fieldnote writing. pic.twitter.com/bHXrf3I55j — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

But to teach how to write good fieldnotes we also need to educate our students on how to write excellent ethnographic prose. For that particular purpose I have two suggestions:

1) Read A LOT OF ETHNOGRAPHIES, particularly book-length.

2) Read books on how to write ethnography.

For (2), I have two books I want to recommend: Kristen Ghodsee’s “From Notes to Narrative” https://t.co/l5SJDByHV1 Ghodsee does something rarely done (from what I’ve read): she walks you from your fieldwork notebook scribbles to producing great ethnographies. Excellent book. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

And the second book is by Kirin Narayan, “Alive in the Writing” https://t.co/qCUayWzz7y Narayan is spectacular in how she crafts narratives, but she also offers EXERCISES. “Here, this is how you do THIS in your writing”. Her writing is very didactic and easy to absorb. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) October 12, 2021

Teaching Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation has already changed me and the term is not over yet. I have been able to spend a lot of time pondering and thinking about the craft of teaching how to do good qualitative research, and it has benefited me enormously.

So, my take home suggestions. If you want to learn how to write good field notes:

1) Read books on field note writing 2) Read books on writing ethnographies 3) Read well written ethnographies 4) Practice writing field notes 5) Practice writing analytic memorandums.

6) Practice writing scholarly outputs.

Hopefully this blog post will be useful to readers interested in qualitative methods.

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia , fieldwork , qualitative methods , research methods , writing .

Tagged with field notes , fieldnotes , fieldwork .

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – October 12, 2021

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Can you recommend books on field note writinfg?

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- The value and importance of the pre-writing stage of writing

- My experience teaching residential academic writing workshops

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

Recent Comments

- Raul Pacheco-Vega on Online resources to help students summarize journal articles and write critical reviews

- Joseph G on Using the rhetorical precis for literature reviews and conceptual syntheses

- Alma Rangel on Improving your academic writing: My top 10 tips

- Jackson on How to respond to reviewer comments: The Drafts Review Matrix

- Charlotte on The value and importance of the pre-writing stage of writing

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

COMMENTS

Describe roles and responsibilities, considering ethical dimensions and client-centered approaches. Demonstrate proficiency in effective fieldwork documentation while adhering to ethical standards. Analyze and navigate ethical challenges in field practice, applying ethical principles.

Definition. The purpose of a field report in the social sciences is to describe the deliberate observation of people, places, and/or events and to analyze what has been observed in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem underpinning the study.

Definition. Refers to notes created by the researcher during the act of conducting a field study to remember and record the behaviors, activities, events, and other features of an observation.

The purpose of field reports is to describe an observed person, place, or event and to analyze that observation data in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem(s) underpinning the study.

An assignment at the Army Human Resources Command (HRC) is an incredible opportunity for officers and enlisted personnel to learn how the Army executes personnel processes. During my time...

Define the importance of fieldwork in social work and its role in professional development. Differentiate between various types of fieldwork in social work practice. Recognize the significance of fieldwork for social work students and apply the EARIS formula.

The Field Instructor, as the official MSW supervisor, is accountable for providing oversite of all social work competencies and documents demonstrating competency and practicum hours completed.

Field notes are an integral part of many types of research, especially within qualitative inquiry. Essentially, field notes are the researcher's written record of observations made, experiences had, and insights gleaned while in the field conducting research.

Definition. Refers to notes created by the researcher during the act of qualitative fieldwork to remember and record the behaviors, activities, events, and other features of an observation setting.

In my Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretation class, I went over what I believe is the core of a field note: I use a notebook, and on one side, I write my observations of whatever I am studying, alongside with the date and time.