Unsupported Browser Detected. It seems the web browser you're using doesn't support some of the features of this site. For the best experience, we recommend using a modern browser that supports the features of this website. We recommend Google Chrome , Mozilla Firefox , or Microsoft Edge

- National Chinese Language Conference

- Teaching Resources Hub

- Language Learning Supporters

- Asia 21 Next Generation Fellows

- Asian Women Empowered

- Emerging Female Trade Leaders

- About Global Competence

- Global Competency Resources

- Teaching for Global Understanding

- Thought Leadership

- Global Learning Updates

- Results and Opportunities

- News and Events

- Our Locations

Islam in Southeast Asia

by Michael Laffan

Asia is home of 65 percent of the world's Muslims, and Indonesia, in Southeast, is the world's most populous Muslim country. This essay looks at the spread of Islam into Southeast Asia and how religious belief and expression fit with extant and modern polictical and economic infrastructures.

It is difficult to determine where Islamic practice begins or ends in any Muslim society, especially as the teachings of Islam encourage Muslims to be mindful of God and their fellow believers at all times. Still, the absence of publicly demonstrated mindfulness of God—whether expressed in terms of the wearing of special dress, such as the many sorts of veils donned by Southeast Asian women, or by recourse to frequent enunciations invoking His name—need not be taken as meaning that the person is any less a Muslim. Indeed, one’s faith is not to be measured by outward acts alone, and Muslim tradition ascribes greater weight to the personal intention of the believer than to outward appearance. Even so, what follows is an explanation of some aspects of the outward expression of Islamic identity in Southeast Asia.

Unity and Diversity

Although the national motto of Indonesia, “Unity in diversity” (Bhinneka tunggal ika), was intended to be an explicitly national one, it is no less applicable to the community of Southeast Asian Muslims, as well as to Muslims the world over. When Muslims come together to worship in the mosque on Friday, or when they perform their daily prayers as individuals, they face the same direction. As such they participate in a unitary tradition. The same might be said of when Muslims greet each other with the traditional Arabic blessing “Peace be with you” (al-salam `alaykum), when they undertake the fast (sawm) during the month of Ramadan, or when they make the pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca.

If asked about the core elements of their faith and practice, many Muslims will point to the five basic duties of Islam. These consist of the profession of faith (shahada), the daily prayers (salat), the hajj, fasting in Ramadan (sawm), and the giving of alms (zakat). However, there is a whole range of calendrical celebrations and rites of passage associated with Islam, not to mention the simple acts of piety that some perform before carrying out basic actions. This might include invoking God’s name before eating or washing one’s face and limbs before prayer. Once again, these acts are shared across Islamic time and space.

On the other hand, many distinctions between believers of different cultural and theological traditions remain in evidence. Even when the global community of the faithful gather in Mecca for the hajj and don the same simple costume of two unsewn sheets (known as ihram), they often travel together in tightly managed groups of fellow countrymen or linguistic communities—at times with tags displaying their national flags. By the same token, there are many specific local practices that are felt to be thoroughly Islamic in Southeast Asia, but these, on occasion, have been condemned by Muslims of different cultural backgrounds by virtue of their absence in, or displacement from, their own histories. Local practices include the use of drums (bedug) in place of the call to prayer (adhan), or the visitation of the tombs of the founding saints of Java.

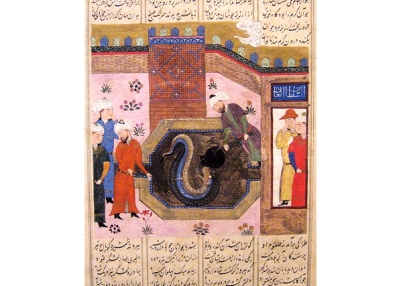

Other such examples of distinct Southeast Asian practices might be linked to the wearing of the sarung (a practice shared with Muslims and non-Muslims throughout Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean), the relatively late circumcision of young males (often celebrated as a major event in village life), the use of shadow puppets (believed by some communities to have been invented by one Muslim saint to explain Islam in the local idiom), or the many popular verse tales of the exploits of an uncle of the Prophet, Amir Hamzah, drawn from Persian and Arabic originals. Even if such practices are regionally distinct or viewed askance elsewhere, if not contested openly, such practices are nonetheless seen as ways of connecting to a faith that is global and egalitarian.

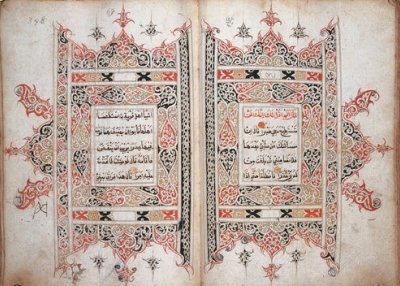

Arabic and the Qur’an

One undeniably universal expression of religiosity is the recitation (qira’a) of the Qur’an, which all Muslims are enjoined to learn as soon as they are able. The Qur’an is understood to be the eternal expression of God’s will revealed through the Angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad, who is believed by Muslims to be the last messenger appointed to mediate between God and humanity. Indeed the Qur’an is also affirmed as the final validation of the messages of all the prophets before him, including those known in the Jewish and Christian traditions. These include Abraham, Joseph, and Jesus, though there are additional figures such as Iskandar (Alexander the Great) and the enigmatic Khidr.

The Qur’an contains stories of all these prophets and many accounts of the difficulties that they—and Muhammad in particular—had in being accepted by their own people before winning them over and establishing God’s law (shari`a) among them. It is further replete with parables ranging over a broad range of human experience, and its recitation brings feelings of closeness to God and His Prophet, as well as solidarity with Muslims all over the world. Some Southeast Asians, such as the Indonesian Hajja Maria Ulfah, have even obtained international recognition for the quality of their recitations.

Yet while the Qur’an may be recited as proficiently, and as often, in Jakarta and Pattani as in Mecca or Algiers, the fact remains that the Holy Text was revealed in Arabic, and in the Arabic of Muhammad’s day. As such all Muslims require explanation of its meanings and those of non-Arab traditions—whether in India, Central Asia or Southeast Asia—require the additional intervention of translation.

The task of the explanation of the divine text is helped, in part, by the fact that Malay (both in its modern Indonesian and Malaysian variants), Javanese, and several other Austronesian languages spoken in insular Southeast Asia, are infused with Islamic terms. This process of linguistic appropriation may be linked with the expansion of a Muslim role in the trade linking the port towns of Southeast Asia, starting in the thirteenth century. It was in this way that the Arabic of the Qur’an, its associated scholarly traditions, and the everyday speech of many of the visiting traders suffused local languages—Malay in particular—with both sacred and profane terms. For example, the Arabic word fard (broadly meaning an obligation), has left two traces in Malay: one with the same sense of a “religious obligation” (fardu), and the other as the more general verb “to need” (perlu).

Regardless of the presence of Arabic elements in the Malay vocabulary that are not specifically religious, Southeast Asian Muslims have long been mindful of the sacred role that Arabic has played in what has increasingly become their history as much as that of Arabs. Certainly, there is a long history of the translation and explication of the Qur’an in the region, although it is important to note that in the Islamic tradition a translation, being the result of human interpretation, may never be elevated to the status of the divine text itself.

This principle, along with heightened contacts with new forms of Islamic thought being propagated from British-occupied Egypt and India in the late nineteenth century, led to debates in the similarly-colonised entities of Indonesia (then the Netherlands Indies) and Malaysia about the legitimacy of attempting to produce a translation—particularly after the widespread availability of printing presses and heightened literacy made it a commercial possibility. Some even argued that written translation (as opposed to the glossing of words and fragments) had never been permitted by Islamic law.

Whether permitted or not, such translations have long been made. Indeed, among the Islamic books brought back to Europe from Southeast Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were Qur’anic texts, religious treatises, and works in verse that made use of holy scripture. These include the works of the mystical poet Hamzah Fansuri (d. 1527), who liberally infused his writings with Qur’anic verses, as well as more neutral Arabic, Persian, and Javanese terms, while stressing his distinct identity as a Malay of Fansur, a port-town of Sumatra.

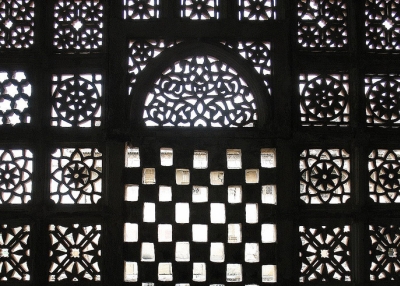

Script and Identity

Alongside its major oral contribution to Southeast Asian Islamic identity, Arabic also has had a visual impact with the adoption of its script for many local languages, with modifications to suit local phonemes such as the sounds “p” and “ng.” By the time Hamzah Fansuri would compose his Malay poems, this phonetic form of writing had already been in use for some three centuries, whether for commemorative stones or for further Islamic propagation. This did not mean that the script displaced earlier methods of writing immediately or permanently. In some cases, local scripts have been maintained for both religious and non-religious texts. Even so, by the time that the Portuguese arrived in Southeast Asia in significant numbers at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Malay was being written primarily with Arabic letters and in a cursive form that is immediately identifiable as pertaining to the region.

In Indonesia, the Arabic script would only be displaced after the widespread popularization of newspapers and school texts in roman script starting in the late nineteenth century, and ever more so in the twentieth when reformist Muslims founded schools to provide the opportunities for modern education largely denied by the Dutch and British. Arabic and Arabic script remain in use in many Islamic schools in Indonesia (now known broadly as pesantren), and both are still used on billboards and signs recommending certain behaviors as Islamic. For example, an advertising campaign in West Sumatra in the 1990s was accompanied by Arabic statements attributed to the Prophet such as “Love of cleanliness is a part of belief ” (Hubb al-nizafa min al-iman).

The Arabic script remains strongly linked to Muslim identity in neighboring Malaysia and Brunei. This is especially the case in Malaysia, with its prominent non-Malay minorities; and it is further discernible in southern Thailand, where the script serves to mark the Muslim community off from the Thai-Buddhist majority and remains the written medium for a considerable local Malay-language publishing industry.

The Study Circle and Its Absence

Whereas Arabic has long been studied by Muslims in Southeast Asia, due to its elevated status as the language of revelation and its importance for connection with the Middle East as the source of Islam, and even though it has made its contribution to the oral and written cultures of the region, the fact remains that Southeast Asians require the aid of teachers and glossaries to make the texts of Islam comprehensible and applicable in daily life. To this end, the months spent learning the Qur’an under the guidance of a teacher is often a crucial period in a child’s life. At the end of this period of study a celebration (known as khatm al-Qur’an) is held in the family home.

More advanced studies of Islam usually require the sort of in-depth education offered by traditional religious schools, such as Indonesia’s pesantrens. Here students learn the requisite texts concerning pronunciation and grammar by the use of glosses in their own languages and various mnemonics or songs. This will allow them to make sense of more advanced works concerning the formal rules laid out in Islamic law defining social interaction, as well as those pertaining to the inculcation of moral values (akhlaq). At all stages a teacher ensures that the individual student has properly mastered a text before advancing to any higher stage of learning. Still, even in these traditional schools—which may be found throughout Southeast Asia and which allow the movement of individuals across national borders— there is a blurring between global religious practice and indigenous cultural expressions. Even when they are in Arabic, many of the songs learned or the texts mastered are related to a specifically Southeast Asian source of inspiration, either from a creator born in the region who assumed a place of importance in Mecca, such as Nawawi of Banten (1813-97), or at the hands of a foreigner who once sojourned through its mosques and fields, such as Nur al-Din al-Raniri (d. 1656). Furthermore, in recent times students have begun to popularize and rephrase many of the popular poems sung in praise of the Prophet. Some musical groups have reached wide audiences by incorporating Arabic lyrics, and Arabic songs have been composed and sung in Southeast Asia with the aim of propagating certain messages among a broader community of Muslims—ranging from gender equity to jihad.

On the other hand, there are also a great many Southeast Asians who never receive such traditional Islamic schooling, who have not learned Arabic or mastered the Qur’an, and for whom such lyrics may be incomprehensible. Many still feel themselves to be full members of the Muslim community (umma), though. For, while they may not fully understand the literal rules of the provisions of Islamic law, they feel that the texts in which it is explained are part of their own Muslim cultural heritage, with which they might connect at rites of passage such as birth, marriage, and the commemoration of death.

Religio-Cultural Intersections and the Modern State

Just as the colonial regimes sought to monitor and regulate the pilgrimage and Islamic schools, the modern state often attempts to play a role in defining religious and cultural practices at both the level of religious obligation and as officially-sanctioned cultural expression. The most obvious interventions may be seen in the specifically national mobilizations for the Hajj. Each year, for example, Indonesia supplies one of the largest contingents of pilgrims (over 200,000 people) for the annual series of ceremonies that take place in Mecca and its surroundings. To get there on such a massive scale necessitates a large degree of national coordination, including the provision of financial support. Beyond finance and coordination though, states also play a proactive role in determining what variants of religious practice may be tolerated, particularly when those variants seem inimical to the government itself or which contest, sometimes violently, the depth of religious commitment of their fellow countrymen. For example, both Malaysia’s quietist Dar al-Ar qam organization, and the radical Ngruki network in Indonesia have seen their activities stopped or severely curtailed in the past decades.

Less tangible, but no less important, than contesting expressions of Islam framed in political terms or in alternative dress and practice, is the role of the state in presenting the style of religiosity felt to represent best the genius of its peoples. Sometimes the gaze is directed outward, sometimes inward. For example, one might think in terms of the architectural designs for many of the region’s modern mosques, which increasingly have a distinctly internationalist style owing more to India and Arabia than Southeast Asia; with minarets and onion domes and arches added to or supplanting the old multilayered pyramidal roofs.

On the other hand there is the Indonesian national museum for the Qur’an in Jakarta, with its showcase holy text (Al-Qur’an Mushaf Istiqlal) that has one page decorated in the style of each province of the Republic. But while the illuminations of Aceh have a distinct pedigree, many of the others are modern inventions designed to help Indonesians to think of the history of their country and its artistic expressions as an inevitable and natural process of combination given added meaning by Islam.

This is not to say, however, that this has always been the case, or that such increasingly Islamic views of history are universally accepted. Both Indonesia and Malaysia include substantial non-Muslim minorities, minorities that at times have become scapegoats during periods of economic uncertainty or because of the taint of imagined collaboration with colonial forces or even as fifth columnists for international communism. Indeed, Indonesia itself has a strong history as an avowedly secularist state, whose officials once placed more emphasis on the region’s pre-Islamic heritage in the form of temple remains. Its best-known author, the late Pramoedya Ananta Toer, even downplayed the role of Islam in the making of Indonesia and focussed instead on the powerful ideas of unity engendered by resistance to Dutch colonialism across the archipelago.

In either form of history, though, whether the view of an Islamic or an areligious anti-colonial national past, it is important to see Southeast Asians placing themselves in relation to a wider world, a world in which “Islam” offers just one set of civilizational practices to draw upon and which may be freely combined with others. In fact, many of the expressions that feed into globalising trends beyond the reach of the state, and redolent of an Islamic identity, are certainly at great variance to what might be conceived of as “traditional” Islam. Here we might think of the many popular groups that fuse the musical styles of the Middle East and Southeast Asia with a presentation owing something to western music videos, or the instructional literature for children now replete with illustrations drawn in the style of Japanese manga. And, again, there is a sphere of personal reflection and reaction that can seem outside the control of the state or that strives to take more from within the Southeast Asian artistic tradition than what lies beyond, whether in poetic musings on experiences in the mosque, or A. D. Pirous’s luminous canvases, which reflect upon both the eternal message and the troubled experiences of his own Acehnese people, who once fought for Indonesian independence in the 1940s but found themselves newly oppressed in the decades that followed.

Certainly one gains a more intimate view of the inner spirituality of Southeast Asian Muslims in such expressions. Even so, while Muslims are joined to each other by the medium of a religious inheritance in their archipelagic homelands, as well as to the broader Muslim community, in the expression of that identity they are undeniably drawing at all times from the images and sounds of the wider, shared world.

Additional Background Reading

Religion in the Philippines

Islamic Belief Made Visual

Islamic Influence on Southeast Asian Visual Arts, Literature, and Performance

Shahnama: The Book of Kings

Islamic Calligraphy and the Illustrated Manuscript

Introduction to Southeast Asia

Historical and Modern Religions of Korea

Excerpts from Religious Texts

Diversity and Unity

Related content.

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

The Spread of Islam in West Africa: Containment, Mixing, and Reform from the Eighth to the Twentieth Century

While the presence of Islam in West Africa dates back to eighth century, the spread of the faith in regions that are now the modern states of Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali and Nigeria, was in actuality, a gradual and complex process. Much of what we know about the early history of West Africa comes from medieval accounts written by Arab and North African geographers and historians. Specialists have used several models to explain why Africans converted to Islam. Some emphasize economic motivations, others highlight the draw of Islam’s spiritual message, and a number stress the prestige and influence of Arabic literacy in facilitating state building. While the motivations of early conversions remain unclear, it is apparent that the early presence of Islam in West Africa was linked to trade and commerce with North Africa. Trade between West Africa and the Mediterranean predated Islam, however, North African Muslims intensified the Trans-Saharan trade. North African traders were major actors in introducing Islam into West Africa. Several major trade routes connected Africa below the Sahara with the Mediterranean Middle East, such as Sijilmasa to Awdaghust and Ghadames to Gao. The Sahel, the ecological transition zone between the Sahara desert and forest zone, which spans the African continent, was an intense point of contact between North Africa and communities south of the Sahara. In West Africa, the three great medieval empires of Ghana, Mali, and the Songhay developed in Sahel.

The history of Islam in West Africa can be explained in three stages, containment, mixing, and reform. In the first stage, African kings contained Muslim influence by segregating Muslim communities, in the second stage African rulers blended Islam with local traditions as the population selectively appropriated Islamic practices, and finally in the third stage, African Muslims pressed for reforms in an effort to rid their societies of mixed practices and implement Shariah. This three-phase framework helps sheds light on the historical development of the medieval empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay and the 19th century jihads that led to the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate in Hausaland and the Umarian state in Senegambia.

Containment: Ghana and the Takrur

The early presence of Islam was limited to segregated Muslim communities linked to the trans-Saharan trade. In the 11th century Andalusian geographer, Al-Bakri, reported accounts of Arab and North African Berber settlements in the region. Several factors led to the growth of the Muslim merchant-scholar class in non-Muslim kingdoms. Islam facilitated long distance trade by offering useful sets of tools for merchants including contract law, credit, and information networks. Muslim merchant-scholars also played an important role in non-Muslim kingdoms as advisors and scribes in Ghana. They had the crucial skill of written script, which helped in the administration of kingdoms. Many Muslim were also religious specialists whose amulets were prized by non-Muslims. Merchant-scholars also played a large role in the spread of Islam into the forest zones. These included the Jakhanke merchant-scholars in [name region], the Jula merchants in Mali and the Ivory Coast, and the Hausa merchants during the nineteenth century in Nigeria, Ghana, and Guinea Basau,]. Muslim communities in the forest zones were minority communities often linked to trading diasporas. Many of the traditions in the forest zones still reflect the tradition of Al-Hajj Salim Suwari, a late fifteenth-century Soninke scholar, who focused on responsibilities of Muslims in a non-Muslim society. His tradition, known as the Suwarian tradition, discouraged proselytizing, believing that God would bring people around to Islam in his own ways. This tradition worked for centuries in the forest zone including the present day, where there are vibrant Muslim minority communities. Although modern Ghana is unrelated to the ancient kingdom of Ghana, modern Ghana chose the name as a way of honoring early African history. The boundaries of the ancient Kingdom encompassed the Middle Niger Delta region, which consists of modern-day Mali and parts of present-day Mauritania and Senegal. This region has historically been home to the Soninken Malinke, Wa’kuri and Wangari peoples. Fulanis and the Southern Saharan Sanhaja Berbers also played a prominent role in the spread of Islam in the Niger Delta region. Large towns emerged in the Niger Delta region around 300 A.D. Around the eighth century, Arab documents mentioned ancient Ghana and that Muslims crossed the Sahara into West Africa for trade. North African and Saharan merchants traded salt, horses, dates, and camels from the north with gold, timber, and foodstuff from regions south of the Sahara. Ghana kings, however, did not permit North African and Saharan merchants to stay overnight in the city. This gave rise to one of the major features of Ghana—the dual city; Ghana Kings benefited from Muslim traders, but kept them outside centers of power. From the eighth to the thirteenth century, contact between Muslims and Africans increased and Muslim states began to emerge in the Sahel. Eventually, African kings began to allow Muslims to integrate. Accounts during the eleventh century reported a Muslim state called Takrur in the middle Senegal valley. Around this time, the Almoravid reform movement began in Western Sahara and expanded throughout modern Mauritania, North Africa and Southern Spain. The Almoravids imposed a fundamentalist version of Islam, in an attempt to purify beliefs and practices from syncretistic or heretical beliefs. The Almoravid movement imposed greater uniformity of practice and Islamic law among West African Muslims. The Almoravids captured trade routes and posts, leading to the weakening of the Takruri state. Over the next hundred years, the empire dissolved into a number of small kingdoms.

Mixing: The Empires of Mali and Songhay

Over the next few decades, African rulers began to adopt Islam while ruling over populations with diverse faiths and cultures. Many of these rulers blended Islam with traditional and local practices in what experts call the mixing phase. Over time, the population began to adopt Islam, often selectively appropriating aspects of the faith. The Mali Empire (1215-1450) rose out of the region’s feuding kingdoms. At its height, the empire of Mali composed most of modern Mali, Senegal, parts of Mauritania and Guinea. It was a multi-ethnic state with various religious and cultural groups. Muslims played a prominent role in the court as counselors and advisors. While the empire’s founder, Sunjiata Keita, was not himself a Muslim, by 1300 Mali kings became Muslim. The most famous of them was Mansa Musa (1307-32). He made Islam the state religion and in 1324 went on pilgrimage from Mali to Mecca. Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca showed up in European records because of his display of wealth and lavish spending. Apparently, his spending devalued the price of gold in Egypt for several years. The famed 14th century traveler Ibn Battuta visited Mali shortly after Mansa Musa’s death. By the fifteenth century, however, Mali dissolved largely due to internal dissent and conflicts with the Saharan Tuareg. Several Muslim polities developed farther east, including the Hausa city-states and the Kingdom of Kanem in modern Northern Nigeria. Hausaland was comprised of a system of city-states (Gobir, Katsina, Kano, Zamfara, Kebbi and Zazzau). The Kingdom of Kanem near Lake Chad flourished as a commercial center from the ninth to 14th century. The state became Muslim during the ninth century. Its successor state was Bornu. Modern day Northern Nigeria comprises much of Hausaland and Bornu in the east. By the 14th century all ruling elites of Hausaland were Muslim, although the majority of the population did not convert until the 18th century jihads. Much like the rulers of earlier Muslims states, the rulers of Hausaland blended local practices and Islam. Emerging from the ruins of the Mali Empire, the Mande Songhay Empire (1430s to 1591) ruled over a diverse and multi-ethnic empire. Although Islam was the state religion, the majority of the population still practiced their traditional belief systems. Many rulers, however, combined local practices with Islam. Sonni Ali, the ruler from 1465-1492, persecuted Muslim scholars, particularly those who criticized pagan practices. During the 13th century, Mansa Musa conquered the Kingdom of Gao. Two centuries later, the kingdom of Gao rose again as the Songhay Empire. Sonni Ali captured much of the Empire of Mali. Under [Aksia Muhammad] 1493-1529), the Songhay’s borders extended far beyond any previous West African empire. The Songhay state patronized Islamic institutions and sponsored public buildings, mosques and libraries. One notable example is the Great Mosque of Jenne, which was built in the 12th or 13th century. The Great Mosque of Jenne remains the largest earthen building in the world. By the 16th century there were several centers of trade and Islamic learning in the Niger Bend region, most notably the famed Timbuktu. Arab chroniclers tell us that the pastoral nomadic Tuareg founded Timbuktu as a trading outpost. The city’s multicultural population, regional trade, and Islamic scholarship fostered a cosmopolitan environment. In 1325, the city’s population was around 10,000. At its apex, in the 16th century, the population is estimated to have been between 30,000 and 50,000. Timbuktu attracted scholars from throughout the Muslim world. The Songhay’s major trading partners were the Merenid dynasty in the Maghrib (north-west Africa) and the Mamluks in Egypt. The Songhay Empire ended when Morocco conquered the state in 1591. The fall of the Songhay marked the decline of big empires in West Africa. Merchant scholars in Timbuktu and other major learning centers dispersed, transferring learning institutions from urban-based merchant families to rural pastoralists throughout the Sahara. During this period there was an alliance between scholars, who were also part of the merchant class, and some warriors who provided protection for trade caravans. Around the 12th and 13th century, mystical Sufi brotherhood orders began to spread in the region. Sufi orders played an integral role in the social order of African Muslim societies and the spread of Islam through the region well into the 20th century.

Reform in the Nineteenth Century: Umarian Jihad in Senegambia and the Sokoto Caliphate in Hausaland

The 19th century jihad movements best exemplify the third phase in the development Islam in West Africa. Specialists have highlighted the ways in which literate Muslims became increasingly aware of Islamic doctrine and began to demand reforms during this period. This period was significant in that it marks a shift in Muslim communities that practiced Islam mixed with “pagan” rituals and practices to societies that completely adopted Islamic values and established Shariah Scholars have debated the origins of the 19th century West African jihads. The first known jihad in West Africa was in Mauritania during the 17th century. At that time, Mauritanian society was divided along scholar and warrior lineages. The scholar Nasir al-Din led a failed jihad called Sharr Bubba. Unlike the failed jihad in Mauritania, the 19th century jihad movements in Senegambia and Hausaland (in what is now northern Nigeria) successfully overthrew the established order and transformed the ruling and landowning class. In 1802, Uthman Dan Fodio, a Fulani scholar, led a major jihad. With the help of a large Fulani cavalry and Hausa peasants, Uthman Dan Fodio overthrew the region’s Hausa rulers and replaced them with Fulani emirs. The movement led to centralization of power in the Muslim community, education reforms, and transformations of law. Uthman Dan Fodio also sparked a literary revival with a production of religious work that included Arabic texts and vernacular written in Arabic script. His heirs continued the legacy of literary production and education reform. Uthman Dan Fodio’s movement inspired a number of jihads in the region. A notable example was the jihad of al Hajj Umar Tal, a Tukulor from the Senegambia region. In the 1850s, Umar Tal returned from pilgrimage claiming to have received spiritual authority over the West African Tijani Sufi order. From the 1850s to 1860s, he conquered three Bambara kingdoms. After Tal’s defeat by the French at Médine in 1857 and the subsequent defeat of his son in the 1880s, his followers fled westward spreading the influence of the Tijani order in Northern Nigeria. Although the French controlled the region, colonial authorities met another formidable enemy. Samori Toure rose up against the French and gathered a 30,000 strong army. Following his death, French forces defeated Toure’s son in 1901. The French occupation of Senegal forced the final development of Islamic practice where leaders of Sufi orders became allies with colonial administrators. Although European powers led to the decline of the Umarian state and the Sokoto Caliphate, colonial rule did little to stop the spread of Islam in West Africa. The British used anti-slavery rhetoric as they began their conquest of the Sokoto Caliphate in 1897. The Sokoto Caliphate ended in 1903, when British troops conquered the state. Colonial authorities attempted to maintain the established social order and ruled through Northern Nigerian emirs. Despite the efforts of colonial authorities, colonialism had far reaching effects on Northern Nigerian Muslim society. Modern communication and transportation infrastructure facilitated increased exchange between Muslim communities. As a result, Islam began to spread rapidly in new urban centers and regions such as Yoruba land. Similarly in the French Sudan, Islam actually spread in rates far greater than the previous centuries. Although Muslims lost political power, Muslim communities made rapid inroads in the West Africa during the early 20th century.

The three stages of containment, mixing, and reform can shed light on the historical developments of Islam in this region. The trans-Saharan trade was an important gateway for the spread of Islam in Africa. The legacy of the medieval empires and nineteenth century reform movements continues to have relevance in present day Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, as well as many neighboring communities. Muslim communities have existed in West Africa for over a millennium, pointing to the fact that Islam is a significant part of the African landscape.

For Further Reading:

- "Western Sudan, 500–1000 A.D.". In Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/sfw/ht06sfw.htm (October 2001)

- "Western and Central Sudan, 1000–1400 A.D.". In Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/07/sfw/ht07sfw.htm (October 2001)

- "Western and Central Sudan, 1400–1600 A.D.". In Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/08/sfw/ht08sfw.htm (October 2002)

- "Western and Central Sudan, 1600–1800 A.D.". In Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/09/sfw/ht09sfw.htm (October 2003)

- David Robinson. Muslim Societies in African History . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels (eds). The History of Islam in Africa . Athens OH: Ohio University Press, 2000.

- Spencer Trimingham, History of Islam in West Africa .New York: Oxford University Press, 1962.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The legacy of Muhammad

Sources of islamic doctrinal and social views.

- The universe

- Satan, sin, and repentance

- Eschatology (doctrine of last things)

- Social service

- The shahādah , or profession of faith

- Shrines of Sufi saints

- Early developments

- The Hellenistic legacy

- The Khārijites

- The Muʿtazilah

- The way of the majority

- Tolerance of diversity

- Influence of al-Ashʿarī and al-Māturīdī

- Related sects

- The Aḥmadiyyah

- Background and scope of philosophical interest in Islam

- The teachings of al-Kindī

- The teachings of Abū Bakr al-Rāzī

- Political philosophy and the study of religion

- Interpretation of Plato and Aristotle

- The analogy of religion and philosophy

- Impact on Ismāʿīlī theology

- The “Oriental Philosophy”

- Distinction between essence and existence and the doctrine of creation

- The immortality of individual souls

- Philosophy, religion, and mysticism

- Background and characteristics of the Western Muslim philosophical tradition

- Theoretical science and intuitive knowledge

- Unconcern of philosophy with reform

- The philosopher as a solitary individual

- Concern for reform

- The hidden secret of Avicenna’s “Oriental Philosophy”

- The divine law

- Traditionalism and the new wisdom

- Characteristic features of the new wisdom

- Critiques of Aristotle in Islamic theology

- Synthesis of philosophy and mysticism

- The teachings of al-Suhrawardī

- The teachings of Ibn al-ʿArabī

- The teachings of Mīr Dāmād

- The teachings of Mullā Ṣadrā

- Impact of modernism

- Family life

- Cultural diversity

- The visual arts

- Architecture

- The Qurʾān and non-Islamic influences

- The mystics

- Cosmogony and eschatology

- Other Qurʾānic figures

- Mystics and other later figures

- Mythologization of secular tales

- Tales and beliefs about numbers and letters

- Illustration of myth and legend

- Significance and modern interpretations

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - Islam

- IndiaNetzone - Islamic Concepts

- PBS - Latino Muslims

- World History Encyclopedia - Islam

- United Religions Initiative - Islam: Basic Beliefs

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art - William Blake

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Islam

- Islam - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Islam - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

Islam , major world religion promulgated by the Prophet Muhammad in Arabia in the 7th century ce . The Arabic term islām , literally “surrender,” illuminates the fundamental religious idea of Islam—that the believer (called a Muslim, from the active particle of islām ) accepts surrender to the will of Allah (in Arabic, Allāh: God). Allah is viewed as the sole God—creator, sustainer, and restorer of the world. The will of Allah, to which human beings must submit, is made known through the sacred scriptures, the Qurʾān (often spelled Koran in English), which Allah revealed to his messenger, Muhammad. In Islam Muhammad is considered the last of a series of prophets (including Adam , Noah , Abraham , Moses , Solomon , and Jesus ), and his message simultaneously consummates and completes the “revelations” attributed to earlier prophets.

Retaining its emphasis on an uncompromising monotheism and a strict adherence to certain essential religious practices, the religion taught by Muhammad to a small group of followers spread rapidly through the Middle East to Africa , Europe , the Indian subcontinent , the Malay Peninsula , and China . By the early 21st century there were more than 1.5 billion Muslims worldwide. Although many sectarian movements have arisen within Islam, all Muslims are bound by a common faith and a sense of belonging to a single community .

This article deals with the fundamental beliefs and practices of Islam and with the connection of religion and society in the Islamic world. The history of the various peoples who embraced Islam is covered in the article Islamic world .

The foundations of Islam

From the very beginning of Islam, Muhammad had inculcated a sense of brotherhood and a bond of faith among his followers, both of which helped to develop among them a feeling of close relationship that was accentuated by their experiences of persecution as a nascent community in Mecca . The strong attachment to the tenets of the Qurʾānic revelation and the conspicuous socioeconomic content of Islamic religious practices cemented this bond of faith. In 622 ce , when the Prophet migrated to Medina , his preaching was soon accepted, and the community-state of Islam emerged. During this early period, Islam acquired its characteristic ethos as a religion uniting in itself both the spiritual and temporal aspects of life and seeking to regulate not only the individual’s relationship to God (through conscience) but human relationships in a social setting as well. Thus, there is not only an Islamic religious institution but also an Islamic law , state, and other institutions governing society. Not until the 20th century were the religious (private) and the secular (public) distinguished by some Muslim thinkers and separated formally in certain places such as Turkey .

This dual religious and social character of Islam, expressing itself in one way as a religious community commissioned by God to bring its own value system to the world through the jihād (“exertion,” commonly translated as “holy war” or “holy struggle”), explains the astonishing success of the early generations of Muslims. Within a century after the Prophet’s death in 632 ce , they had brought a large part of the globe—from Spain across Central Asia to India—under a new Arab Muslim empire.

The period of Islamic conquests and empire building marks the first phase of the expansion of Islam as a religion. Islam’s essential egalitarianism within the community of the faithful and its official discrimination against the followers of other religions won rapid converts. Jews and Christians were assigned a special status as communities possessing scriptures and were called the “people of the Book” ( ahl al-kitāb ) and, therefore, were allowed religious autonomy . They were, however, required to pay a per capita tax called jizyah , as opposed to pagans, who were required to either accept Islam or die. The same status of the “people of the Book” was later extended in particular times and places to Zoroastrians and Hindus , but many “people of the Book” joined Islam in order to escape the disability of the jizyah . A much more massive expansion of Islam after the 12th century was inaugurated by the Sufis (Muslim mystics), who were mainly responsible for the spread of Islam in India , Central Asia, Turkey, and sub-Saharan Africa ( see below ).

Beside the jihad and Sufi missionary activity, another factor in the spread of Islam was the far-ranging influence of Muslim traders, who not only introduced Islam quite early to the Indian east coast and South India but also proved to be the main catalytic agents (beside the Sufis) in converting people to Islam in Indonesia , Malaya, and China. Islam was introduced to Indonesia in the 14th century, hardly having time to consolidate itself there politically before the region came under Dutch hegemony .

The vast variety of races and cultures embraced by Islam (an estimated total of more than 1.5 billion persons worldwide in the early 21st century) has produced important internal differences. All segments of Muslim society, however, are bound by a common faith and a sense of belonging to a single community. With the loss of political power during the period of Western colonialism in the 19th and 20th centuries, the concept of the Islamic community ( ummah ), instead of weakening, became stronger. The faith of Islam helped various Muslim peoples in their struggle to gain political freedom in the mid-20th century, and the unity of Islam contributed to later political solidarity.

Islamic doctrine, law, and thinking in general are based upon four sources, or fundamental principles ( uṣūl ): (1) the Qurʾān, (2) the Sunnah (“Traditions”), (3) ijmāʿ (“consensus”), and (4) ijtihād (“individual thought”).

The Qurʾān (literally, “reading” or “recitation”) is regarded as the verbatim word, or speech, of God delivered to Muhammad by the archangel Gabriel . Divided into 114 suras (chapters) of unequal length, it is the fundamental source of Islamic teaching. The suras revealed at Mecca during the earliest part of Muhammad’s career are concerned mostly with ethical and spiritual teachings and the Day of Judgment. The suras revealed at Medina at a later period in the career of the Prophet are concerned for the most part with social legislation and the politico-moral principles for constituting and ordering the community.

Sunnah (“a well-trodden path”) was used by pre-Islamic Arabs to denote their tribal or common law . In Islam it came to mean the example of the Prophet—i.e., his words and deeds as recorded in compilations known as Hadith (in Arabic, Ḥadīth: literally, “report”; a collection of sayings attributed to the Prophet). Hadith provide the written documentation of the Prophet’s words and deeds. Six of these collections, compiled in the 3rd century ah (9th century ce ), came to be regarded as especially authoritative by the largest group in Islam, the Sunnis. Another large group, the Shiʿah , has its own Hadith contained in four canonical collections.

The doctrine of ijmāʿ , or consensus , was introduced in the 2nd century ah (8th century ce ) in order to standardize legal theory and practice and to overcome individual and regional differences of opinion. Though conceived as a “consensus of scholars,” ijmāʿ was in actual practice a more fundamental operative factor. From the 3rd century ah ijmāʿ has amounted to a principle of stability in thinking; points on which consensus was reached in practice were considered closed and further substantial questioning of them prohibited. Accepted interpretations of the Qurʾān and the actual content of the Sunnah (i.e., Hadith and theology) all rest finally on the ijmāʿ in the sense of the acceptance of the authority of their community.

Ijtihād , meaning “to endeavour” or “to exert effort,” was required to find the legal or doctrinal solution to a new problem. In the early period of Islam, because ijtihād took the form of individual opinion ( raʾy ), there was a wealth of conflicting and chaotic opinions. In the 2nd century ah ijtihād was replaced by qiyās (reasoning by strict analogy), a formal procedure of deduction based on the texts of the Qurʾān and the Hadith. The transformation of ijmāʿ into a conservative mechanism and the acceptance of a definitive body of Hadith virtually closed the “gate of ijtihād ” in Sunni Islam while ijtihād continued in Shiʿism. Nevertheless, certain outstanding Muslim thinkers (e.g., al-Ghazālī in the 11th–12th century) continued to claim the right of new ijtihād for themselves, and reformers in the 18th–20th centuries, because of modern influences, caused this principle once more to receive wider acceptance.

The Qurʾān and Hadith are discussed below. The significance of ijmāʿ and ijtihād are discussed below in the contexts of Islamic theology , philosophy, and law.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Trade and Geography in the Spread of Islam *

Stelios michalopoulos.

† Brown University, Department of Economics, 64 Waterman st., Robinson Hall, Providence, RI 02912, USA, CEPR, and NBER, ude.nworb@olahcims .

Alireza Naghavi

‡ University of Bologna. Department of Economics, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy, [email protected]

Giovanni Prarolo

§ University of Bologna. Department of Economics, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy, [email protected] .

Associated Data

In this study we explore the historical determinants of contemporary Muslim representation. Motivated by a plethora of case studies and historical accounts among Islamicists stressing the role of trade for the adoption of Islam, we construct detailed data on pre-Islamic trade routes, harbors, and ports to determine the empirical regularity of this argument. Our analysis – conducted across countries and across ethnic groups within countries – establishes that proximity to the pre-600 CE trade network is a robust predictor of today’s Muslim adherence in the Old World. We also show that Islam spread successfully in regions that are ecologically similar to the birthplace of the religion, the Arabian Peninsula. Namely, territories characterized by a large share of arid and semiarid regions dotted with few pockets of fertile land are more likely to host Muslim communities. We discuss the various mechanisms that may give rise to the observed pattern.

“ O you who believe! Eat not up your property among yourselves unjustly except it be a trade amongst you, by mutual consent. And do not kill yourselves (nor kill one another). Surely, Allah is Most Merciful to you.” The Noble Qur’an (Hilali-Khan translation), Surah An-Nisa’, 4:29 1

1. Introduction

Religion is significantly correlated with a range of economie and politicai outcomes both within and across countries. 2 This can, perhaps, be linked to the fact that religious people tend to be more trusting in general ( Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales, 2003 ). Given the importance of religion in society, a natural question to ask is what factors contributed to the distribution of religions around the globe that we see today.

In this study, we focus on the spread of one religion – Islam. There has been growing interest in Muslim societies in recent years amongst economists and political scientists, see for example, Blydes (2014) , Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott (2015) , Clingingsmith, Khwaja, and Kremer (2009) , Jha (2013) , and Kuran (2004) . Our analysis investigates the role that ancient trade routes have played in facilitating the spread of Islam. Motivated by numerous case studies on the historical relationship between trade and Islam, we construct detailed data on pre-Islamic trade routes, ports, and harbors. Proximity to the pre-600 CE trade network is a robust predictor of today’s Muslim adherence in the Old World. We also show that Islam spread successfully in regions that are ecologically similar to the birthplace of the religion, the Arabian Peninsula.

The empirical analysis establishes that countries located closer to historical trade routes are more likely to be Muslim. We then investigate whether this empirical regularity holds at the more disaggregated level of ethnic homelands within countries. Exploiting within-country variation has straightforward advantages. First, it allows us to test in a sharper manner whether differences in proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes are meaningful predictors of local adherence to Islam. Second, leveraging within contemporary-state variation in Muslim representation mitigates concerns related to the endogeneity of current political boundaries. Modern states, arguably, have affected religious affiliation in a multitude of ways including state-sponsored religion. As such, it is crucial to account for these nationwide histories.

These findings are in line with a rich body of earlier work by prominent Islamicists including Lapidus (2002) , Berkey (2003) , and Lewis (1993) , who have extensively discussed the role of long-distance trade, noting both the diffusion of Muslims along trade routes ( Geertz, 1968 ; Lewis, 1980 ; Trimingham, 1962 ) and the importance that Islamic scriptures confer on trade-related matters ( Cohen, 1971 ; Hiskett, 1984 ; Last, 1979 ). An innovation of Islam was the practice of direct trade, where Muslim merchants personally carried goods over long distances along the trade routes rather than relying on intermediaries. For example, the acceptance of Islam in most of Inner Asia, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa is known to have occurred primarily through contacts with Muslim merchants ( Insoll, 2003 ; Lapidus, 2002 ; Levtzion, 1979 ). In addition, the highly personal practice of exchange created preference for Muslims to conduct trade with co-religionists (Chaudhuri, 1995; Kuran and Lustig, 2012 ). Therefore, merchants converting to Islam enjoyed substantial externalities like access to the Muslim trade network, steady trade flows, and a reduction in transaction costs. In Section 2 we provide a brief overview illustrating the role of trade in the Islamization process in various parts of the Old World.

Although the primary contribution of this study is to establish how proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes has influenced the distribution of Muslim communities in the Old World, we also explore whether the ecological similarity to the Arabian peninsula of a given region predicts the presence of Muslim communities. But which are the salient geographic features of the cradle of Islam? The Arabian peninsula has a distinct geography, mainly consisting of desert and semi-arid landscapes with a few regions of moderate fertility such as today’s Yemen and other scattered oases in the interior. On the eve of Islam, frankincense, myrrh, vine, dyes, and dates were produced in these fertile pockets ( Ibrahim, 1990 ). To capture this distinct landscape, we construct for each country/ethnic homeland the Gini coefficient of land suitability for agriculture and show that ecological similarity to the Arabian Peninsula (reflected in the degree of inequality in the potential for farming across regions) increases Muslim representation.

We discuss various explanations consistent with this less-well-known fact and show that groups residing along geographically unequal territories have a particular production structure (both historically and today) with pasture dominating the semi-arid landscape and farming taking place in the few relatively fertile regions. These differences in the underlying productive endowments may generate gains from specialization and provide a basis for trade as a means of subsistence. This is indeed the case for a cross-section of ethnographic societies we examine. So, to the extent that trade is likely to flourish when the parties involved adhere to a common code of exchange, the trade-promoting institutional framework of Islam would find likely converts across such territories.

A complementary interpretation links geographic inequality to social inequality and predation and echoes Ibn Khaldun (1377) , one of the greatest philosophers of the Muslim world, who observed that a crucial factor for understanding Muslim history is the central social conflict between the primitive Bedouin and the urban society (“town” versus “desert”). The argument is that long-distance trade opportunities confer differential gains to populations residing in the relatively more fertile regions, fostering predatory behavior from the poorly endowed ones. Along the same lines, contemporary scholars have noted that when farmers and herders coexisted in absence of an institutional framework coordinating their activities, their interactions were often conflictual, disrupting trade flows across these territories ( Richerson, 1996 ). We conjecture that Islam with its redistributive economic principles was a unifying force aimed at reining in the underlying inequality in exchange for security for the trading caravans ( Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo, 2016 ). The premise that geographie inequality becomes more salient when long-distance trade opportunities arise generates an auxiliary prediction. Namely, the intensity of adoption of Islam across unequally endowed regions should increase with proximity to trade routes. This prediction is borne out in the data.

Our study belongs to a wider literature in economics that explores the interplay between the economic and political environment and (religious) beliefs and rules. Contributions include works by Greif (1994) , Benabou and Tirole (2001) , Botticini and Eckstein (2005 , 2007 ), Cervellati and Sunde (2017) , Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2016) , Platteau (2008 , 2011 ), Rubin (2009) , Becker and Woessmann (2009) , and Greif and Tabellini (2010) . Moreover, by focusing on the spread of a particular religion, our work is closely related to that of Cantoni (2012) who explores how proximity to Wittemberg, the birthplace of Martin Luther, influenced the diffusion of Protestantism. The evidence provided on the consistent geographic pattern followed by the Muslim world also makes contact with the studies by Engerman and Sokoloff (1997 , 2002 ) and Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2001 , 2002 ), among others, that stress the role of geography in shaping institutional outcomes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we provide a historical narrative of the significance of trade for the spread of Islam. In Section 3 , we discuss the data and present the empirical analysis conducted across countries and ethnic groups. In Section 4 , we dig deeper into what distance to trade routes and geographic inequality reflect and outline possible explanations consistent with the uncovered evidence. Section 5 summarizes and discusses avenues for future research.

2. The Spread of Islam along Historical Trade Routes

Islam has spread at a breathless pace since the time of Muhammad. Nevertheless, the mode of expansion has differed across time and space ranging from conquests, to trade, to proselytization and migrations. During the early phase, Islam expanded mainly through conquests within a certain radius around Mecca. The initial military conquests, even if they did not entail forced conversion, eventually resulted in Muslim-majority populations occupying large swaths of land. These areas overlap with contemporary countries close to Mecca including the entire Arab World in the Middle East and North Africa, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and slightly further away in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The territories featured important trade hubs during the pre-Islamic era, particularly those along the Silk Road in Asia and the Red Sea in North Africa. Most of these lands were part of the Persian Empire, which was the largest and most important empire of the time to be conquered and concede to Islam. Famous trade hubs along the routes of the Persian Empire were Rey (in Iran), Samarkand and Bukhara (in Uzbekistan), and Merv (in Turkmenistan).

The process of Islamization farther away from the birthplace of Islam was intimately linked to trade. The Islamic world came to dominate the network of the most lucrative international trade routes that connected Asia to Europe (and by sea to North Africa). With full Muslim control of the western half of the Silk Road by mid-8th century, any long-distance exchange had to traverse Muslim lands, giving trade a central role in the further propagation of the religion. Muslim merchants carried the message of Islam wherever they traveled. This was possible because of the Muslim practise of “direct” trade, one of the most remarkable innovations of Islam. Prior to Muslim conquests, trade was conducted by a network of local merchants who traded exclusively in their homelands. In other words, they played the role of intermediary agents with goods (often spices) being transported from one carrier to another by short journeys, creating a trade-relay. Muslims instead did not rely on intermediaries and personally travelled the entire length of the journey, crucial for the diffusion of the religion along the trade routes and at the destination. The spread of Islam was hence greatly enhanced by social contact as a consequence of trade ( Miller, 1969 ; Wood, 2003 ).

On the receiving end, the new religion appealed to the local merchants because it legitimized their economic base more than most belief systems present at that time. Merchants converting to Islam had clear advantages including (i) cooperation within the Muslim trading network, (ii) valuable contacts to expand their trade, and (iii) rules governing commercial activities naturally favoring Muslims over non-Muslims ( Sinor, 1990 ; Foltz, 1999 ).

Proselytization was a third factor that inffuenced the spread of Islam across locations most distant to Mecca. Trade routes were also important in this process as the charismatic Sufi preachers travelled along these routes to perform missionary activities. Finally, migration of Muslims (again through trade routes) and their inter-marriages at the destination also contributed to the spread of Islam along the trade routes distant from Mecca.

2.1. The Adoption of Islam by Ethnie Groups in the Vicinity of Trade Routes

The historical accounts linking trade routes and Muslim adherence across countries are indicative of their importance for the spread of Islam. Nevertheless, given the power of the state to inffuence its religious composition, one may wonder whether a similar nexus between proximity to trade hubs and Muslim representation exists within countries that are not religiously homogeneous. In what follows, we review the historical record on the emergence of Islam for specific countries with varying religious diversity including China, Tanzania, Mali (the location of the former Ghana Empire), Indonesia, and India. A systematic empirical analysis at the ethnic group level for each of these countries is relegated to Section 3.3 .

Figures 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, and 1e provide snapshots of pre-Islamic trade routes along with contemporary Muslim representation for groups located in these five regions making apparent the link between the two (see Section 3.1 below for a description of the underlying data).

Figure 1 portrays Muslim adherence at the ethnic group level and historical trade routes within five countries (1a: China, 1b: Mali, 1c: Tanzania, 1d: Indonesia and 1e: India). Muslim adherence is represented in quintiles at the level of ethnic group, where actual homelands are from the Ethnologue version 15 and data on religious affiliation from the World Religion Database. Darker shades represent higher Muslim shares in the population. In Figures 1a, 1c, and 1e the trade routes are depicted as thick, black-and-white dashed lines and correspond to pre-600 CE. These routes are digitized from Brice and Kennedy (2001) . The ancient ports and harbors, depicted as circled stars, are from Arthur de Graauw (2014) . In figure 1b trade routes are relative to 900 AD, while in figures 1c and 1d ports in year 600 CE (1800 CE) are represented with circled stars (circled dots). Country borders are represented with a thin dashed grey line.

2.2. Inner Asia

By the 8th century, Islam was no longer the religion of only the Arab world and had expanded geographical borders along the Silk Road. Conversions were often a result of economic considerations and the financial benefits afforded to those joining the Ummah. Even among the conquered people in Central Asia, Islam continued to gain a hearing without coercion as merchants spread the religion. Muslim traders traveled as far as the capital of the Tang dynasty, Chang’an, in the Chinese Empire. The 9th century saw the rise of Islamic kingdoms in Central Asia, especially the Samanid Empire, the first Persian dynasty after the Arab conquests. The Islamization of the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central and Inner Asia occurred during the 10th century along the trade routes. This process has been linked mainly to their participation in the oasis-based Silk Road trade and was accelerated by the conversion and the expansion of three Turkic Muslim dynasties of the Karakhanids, the Ghaznavids, and the Seljuks ( Meri and Bacharach, 2006 ).

The major ethnic groups close to trade routes with a substantial Muslim representation in this region are the Uyghurs, the Hui, the Kazakhs, the Kyrgyz, and the Tajiks. These ethnic groups also exist within China today and comprise the Muslim minority in the country. They are all located around Xianjiang, a vast region of deserts and mountains along the Silk Road in Northwest China.

The Uyghurs are one of the largest ethnic groups in Inner Asia, and their Islamization dates back to the Karakhanids in early 10th century, the first Turkic dynasty to convert to the new religion. The core of the Uyghurs’ homeland was Kashgar, an oasis city located in the West of China near the current-day border of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which historically served as a strategic trade hub between China, the Middle East, and Europe ( Roemer, 2000 ). The Hui people are another Muslim Chinese minority historically connected to Muslim merchants travelling along the Silk Road. Besides Xianjiang, they also live farther east in Central China. A cluster of this group can be found today in Xi’an, where they form the majority of a large Muslim community (the dark spot in the center of China in Figure 1a ). Xi’an was the first city in China where Islam was introduced. ( Soucek, 2000 ). The longest segment of the Silk Road runs across the Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The religion practiced by the majority of Kazakhs is Islam since its introduction in the region by the Arabs during the 9th century. The Kyrgyz tribes also adopted Islam as Muslim traders and then Sufi missionaries began to move out from scattered towns to the nomadic steppes, spreading Islam among the tribal groups. They are known to have adopted Islam between the 8th and 12th centuries. The Tajiks on the other hand, started converting to Islam in the late 11th century ( Minahan, 2014 ).

2.3. East and West Africa

Islam spread through the well-established trade routes of the east coast of Africa via merchants. The earliest records for trade in East Africa indicate Greco-Roman trade down the Red Sea and along the Somali coast to the Tanzanian coast. This was followed by the trade of frankincense, myrrh, and spices with the Persian Gulf from the 2nd to the 5th century CE. Soon Zanzibar Island also became a trade hub and remained so until the 9th century CE, when Bantu traders settled on the Kenyan-Tanzanian coast and joined the Indian Ocean trade networks interacting with the Somali and Arab proselytizers. Shanga, an early Swahili town on Pate Island in the Lamu Archipelago, is a good example of early influence through Muslim traders as they built the first small wooden mosque in the region around 850 CE ( Shillington, 2005 ). Islam was established on the Southeast coast soon after, and eventually a full-scale prosperous Muslim dynasty known for trading gold and slaves was established at Kilwa on the coast of modern Tanzania. By the 11th century CE, several settlements down the east coast were equipped with mosques, and Islam emerged as a unifying force on the coast to form a distinct Swahili identity ( Trimingham, 1964 ).

Historical accounts suggest that the early penetration of Islam was even more effective along the caravan routes of West Africa. Trans-Saharan trade started on a regular basis during the 4th century and presents a clear example of subsistence from trade between the people of the Sahara, forest, Sahel, and savanna ( Boahen, Ajayi, and Tidy, 1966 ). While present since 500 CE, the significance of the trans-Saharan trade routes rose and declined over time depending on the empire in power and the security that could be maintained along the routes ( Devisse, 1988 ). Islam was introduced through Muslim traders along several major trade routes that connected Africa below the Sahara with the Mediterranean Middle East, such as Sijilmasa to Awdaghust and Ghadames to Gao. Muslims crossed the Sahara into West Africa trading salt, horses, dates, and camels for gold, timber, and foodstuff from the ancient Ghana empire. The trade-friendly elements of Islam, such as credit or contract law, together with the information networks it helped create, facilitated long-distance trade. By the 10th century, merchants to the south of the trade routes had converted to Islam. In the 11th century CE the rulers began to convert. The first Muslim ruler in the region was the king of Gao, around the year 1000 CE. The Kanem empire (the Kanuri people), located at the southern end of the trans-Saharan trade route between Tripoli and the region of Lake Chad, followed after being exposed to Islam through North African traders, Berbers, and Arabs ( Trimingham, 1962 ; Levtzion and Pouwels, 2000 ; Robinson, 2004 ).

2.4. South and Southeast Asia

There is ample historical evidence indicating that Arabs and Muslims interacted with India from the very early days of Islam, although trade relations had existed since ancient times. Malabar and Kochi were two important princely states on the western coast of India where Arabs and Persians found fertile ground for their trade activities. The trade on the Malabar coast prospered due to the local production of pepper and other spices. Islam was first introduced to India by the newly converted Arab traders reaching the western coast of India (Malabar and the Konkan-Gujarat region) during the 7th century CE ( Elliot and Dowson, 1867 ; Makhdum, 2006 ; Rawlinson, 2003 ).

Cheraman Juma Masjid in Kerala is thought to be the first mosque in India. It was built towards the end of Muhammad’s lifetime during the reign of the last ruler of the Chera dynasty, who converted to Islam and facilitated the proliferation of Islam in Malabar. The 8th century CE marked the start of a period of expansion of Muslim commerce along all major routes in the Indian Ocean, suggesting that the Islamic influence during this period was essentially one of commercial nature. Initially settling in Konkan and Gujarat, the Persians and Arabs extended their trading bases and settlements to southern India and Sri Lanka by the 8th century CE, and to the Coromandel coast in the 9th century CE. These ports helped develop maritime trade links between the Middle East and Southeast Asia during the 10th century CE ( Wink, 1990 ).

The people of the Malay world have been active participants in trade and maritime activities for over a thousand years. Their settlements along major rivers and coastal areas were important means of contact with traders from the rest of the world. The strategic location of the Malay Archipelago at the crossroad between the Indian Ocean and East Asia, and in the middle of the China-India trade route, aided the rapid development of trade in the region ( Wade, 2009 ). In particular, the Srivijaya kingdom (7th −13th century CE) on the straits of Malacca attracted ships from China, India, and Arabia plying the China-India trade routes by ensuring safe passage through the Straits of Malacca ( Andaya and Andaya, 1982 ).

Similar to those in Africa, rulers in Southeast Asia often converted to Islam through the influence of Muslim merchants who set up or conducted business there. While the landed Hindu-Buddhists were content to let the trade come to them, the Muslim merchants, lacking a fixed land base, made their profits from trade at the location of exchange. Consequently, the people of Southeast Asia began to accept Islam and create Muslim towns and kingdoms. By the late 13th century CE, the kingdom of Pasai in northern Sumatra had converted to Islam. At the same time, the collapse of Srivijayan power at the end of the 13th century CE drew foreign traders to the harbors on the northern Sumatran shores of the Bay of Bengal, safe from the pirate lairs at the southern end of the Strait of Malacca ( Houben, 2003 ; Ricklefs, 1991 ). Around 1400 CE, a new kingdom was established in Malacca (on the north shore of the Malacca Strait). The rulers of Malacca soon accepted Islam in order to attract Muslim and Javanese traders to their port by providing a common culture and offering legal security under Islamic law ( Holt, Lambton, and Lewis, 1970 ; Esposito, 1999 ). Finally, the Bugis, an ethnic group along Java’s northern coast adopted Islam later in the 16th century CE when Muslim proselytizers from West Sumatra came in contact with the people of this region who conducted trade ( Mattulada, 1983 ).

3. Empirical section

3.1. the data sources.

The historical overview vividly illustrates the importance of pre-existing trade routes for the diffusion of Islam but also suggests the beneficial impact of Islam on the further expansion of the trade network. To make sure we capture the first part of this two-way relationship, we construct our main explanatory variable by measuring the distance between the relevant unit of analysis (a country or an ethnic homeland) and the closest historical trade route or port before 600 CE, reflecting the structure of trade flows already present in the Old World in the eve of Islam. 3

The location of trade routes is outlined in Brice and Kennedy (2001) whereas the location of ancient ports and harbors is taken from the work of De Graauw, Maione-Downing, and McCormick (2014) who collected and identified their precise locations. The result is an impressive list of approximately 2, 900 ancient ports and harbors mentioned in the writings of 66 ancient authors and a few modern authors, including the Barrington Atlas. We complement the pre-600 CE routes mapped in Brice and Kennedy (2001) with information on the Roman roads identified in the Barrington Atlas ( McCormick, et al., 2013 ). Finally, we also extend the trade network up to 1800 CE, digitizing the relevant information from Brice and Kennedy (2001) , and supplementing it with routes within Europe, Southeast Asia, West Africa, and China mapped in O’Brien (1999) during the same time period. We expect these data to be useful to other researchers. See Figures 2a and 2b for the reconstruction of the pre-Islamic and pre-1800 CE trade network, respectively.

Figure 2a (2b) shows the Old World network of Roman roads (from the Barrington Atlas), ancient ports and harbours (from Arthur de Graauw, 2014 ) and trade routes (from Brice and Kennedy, 2001 ) in 600 AD (1800 AD).

In the cross-country analysis, the dependent variable employed is the fraction of Muslims in the population as early as 1900 CE reported by Barrett, Kurian, and Johnson (2001) . For the ethnic group analysis, the dependent variable is the fraction of Muslims and of other religious denominations in 2005 from the World Religion Database (WRD). 4 These estimates are extracted from the World Christian Database and are subsequently adjusted based on three sources of religious affiliation: census data, demographic and health surveys, and population survey data. 5 In absence of historical estimates of Muslim representation at an ethnic group level, we are constrained in using contemporary data. Reassuringly, country-level Muslim representation derived from the group-specific estimates of the WRD are highly correlated (0.93) with the respective country statistics on Muslim adherence in 1900 CE.

Information on the location of ethnic groups’ homelands is available from the World Language Mapping System (WLMS) database. This dataset maps the locations of the language groups covered in the 15th edition of the Ethnologue (2005) database. The location of each ethnic group is identified by a polygon. Each of these polygons delineates the traditional homeland of an ethnic group; populations away from their homelands (e.g., in cities, refugee populations, etc.) are not mapped. Also, the WLMS (2006) does not attempt to map immigrant languages. Finally, ethnic groups of unknown location, widespread ethnicities (i.e., groups whose boundaries coincide with a country’ boundaries) and extinct languages are not mapped and, thus, not considered in the empirical analysis. The matching between the WLMS (2006) and the WRD is done using the unique Ethnologue identifier for each ethnic group within a country. 6

To capture how similar the ecology of a given region is to that of the Arabian Peninsula, we construct the distribution of land quality and, in turn, the Gini coefficient of regional land potential for agriculture across countries and homelands. Under the assumption that land quality dictates the productive capabilities of a given region, populations on fertile areas would engage in farming whereas pastoralism would be the norm in poorly endowed regions (see more on this in Section 4 ). In the absence of historical data on land quality, we use contemporary disaggregated data on the suitability of land for agriculture to proxy for regional productive endowments. The global data on current land quality for agriculture were assembled by Ramankutty et al. (2002) to investigate the effect of future climate change on contemporary agricultural suitability and have been used extensively in the recent literature in historical comparative development. Each observation takes a value between 0 and 1 and represents the probability that a particular grid cell may be cultivated. 7

Finally, we combine anthropological information on ethnic groups from Murdock (1967) with the Ethnologue (2005) , enabling us to examine the pre-colonial societal and economic traits of Muslim groups. We discuss these two datasets in more detail as we introduce them to our analysis.

3.2. Cross-Country Analysis

We start by investigating the relationship between distance to trade routes in the Old World and Muslim adherence across modern-day countries. The cross-country summary statistics and the corresponding correlation matrix of the variables of interest are reported in Appendix Table 1 .

To estimate how proximity to trade routes shapes Muslim adherence we adopt the following OLS specification:

where % Muslim 1900 i is the fraction of the population in country i adhering to Islam in 1900 CE. 8