- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What Does “Longform” Journalism Really Mean?

On love and ruin , terminology, and the anxiety of limits.

Writers are preoccupied with limits: temporal and physical and metaphysical, the divisions between self and other, the mind’s inability to reconstruct the subject of its fascination. Borges envisioned “a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point.” Moby-Dick ’s Ishmael claimed that “true places” resisted the attempts of mapmakers. Stories often assume the shape of their limitations. In 2006, the same year that Twitter launched, Robert Olen Butler published Severance , a story collection that employed what one reviewer called “a new—and unlikely to be replicated—art form, the vignette of the severed head told in exactly 240 words.”

For journalists, tasked with something like verisimilitude, these limits are always existential. Joe Gould claimed to be writing an oral history whose purview was the knowable world. Joseph Mitchell, who first profiled Gould for The New Yorker in 1942, came to doubt the history’s existence, and said as much after Gould’s death. Gould’s history was never published. Another New Yorker staff writer, Jill Lepore, suspects Gould’s compulsive writing was hypergraphia. “This is an illness, a mania,” she wrote, “but seems more like something a writer might envy.” Perhaps Mitchell did; after his final piece on Gould, Mitchell never published another word. Like Gould’s productivity, Mitchell’s silence was storied but impossible to verify. Lepore wrote about both men in “Joe Gould’s Teeth,” a feature article whose word count grew into a book-length manuscript.

“Writers tumble into this story,” wrote Lepore, “and then they plummet.” The boundaries of the observable world push inward and outward; we are fathomless, the universe immeasurable. Where, then, should a story begin and end?

In the past decade, as declining ad revenue constricted editorial space in print publications, online publishing offered journalists freedom from some of their limits. A story could be as complicated as its subject required, and as long as necessary, though the ancient caveat still applied: your readers might not stick with you until the end. Websites such as BuzzFeed, whose content seemed to assume a newly attention-deficient readership, occasionally published pieces of narrative nonfiction whose word counts reached into the thousands. Online publishers began to label such stories “longform.”

Journalists and their readers have an uneasy history with such labels. “I have no idea who coined the term ‘the New Journalism’ or when it was coined,” wrote Tom Wolfe in a 1972 feature article in New York . “I have never even liked the term.” Neither did Hunter S. Thompson, who wrote to Wolfe and threatened to “have your goddamn femurs ground into bone splinters if you ever mention my name again in connection with that horrible ‘new journalism’ shuck you’re promoting.” (Wolfe still included Thompson in his 1973 anthology, The New Journalism .) “Creative nonfiction” still enjoys wide usage, and a magazine exists by the same name. Its editor, Lee Gutkind, writes that Creative Nonfiction “defines the genre simply, succinctly, and accurately as ‘true stories well told.’” These labels amount to a shaggy taxonomy; journalists that share certain aesthetics are grouped together, and then those groups are differentiated from each other, to the presumed benefit of readers.

Such labels sometimes reward the writer, who becomes associated with a popular movement. They sometimes reward the reader, who has a new word for what she seeks. Most often, they reward the publisher. But a publisher’s loyalties can shift with the market. Medium, a publishing platform that developed an early reputation for longform journalism, distanced itself from the label. (“It was not our intention… to create a platform just for ‘long-form’ content,” said Ev Williams, Medium CEO and a co-founder of Twitter.) BuzzFeed, on the other hand, hired a “longform editor” in 2013 to oversee a section of the site devoted to such stories. The longform editor described his section as “BuzzFeed for people who are afraid of BuzzFeed.”

Whether labels like “longform” reward a story is another matter. “Length is hardly the quality that most meaningfully classifies these stories,” wrote James Bennet in The Atlantic . “Yet there’s a real conundrum here: If ‘long-form’ doesn’t fit, what term is elastic enough to encompass the varied journalism it has come to represent, from narrative to essay, profile to criticism?” The term “journalism” is, somehow, insufficient.

Taxonomy presents one conundrum; popularity makes for another. The “longform” label offers readers and writers a new way to self-identify, and a new hashtag by which they may find, distinguish and promote stories. An attendant risk is that a story’s appeal as a “longform” product could short-circuit editorial judgment and damage a writer or his subject before a large audience.

In 2014, Grantland published “ Dr. V’s Magical Putter ,” a 7,000-word profile of an inventor and transgender woman whose gender transition was revealed in the story—before she had revealed it to people in her life. “What began as a story about a brilliant woman with a new invention,” author Chris Hannan wrote, “had turned into the tale of a troubled man who had invented a new life for himself.” Hannan reveals in his final paragraphs that his subject committed suicide, and wrote, “Writing a eulogy for a person who by all accounts despised you is an odd experience.” In the New York Times , Jonathan Mahler cautioned readers and writers again “fetishizing the form and losing sight of its function.”

“Longform” springs from journalism’s anxiety over limitations—mainly, its online audience’s attention span. During the longform decade, software developers created programs that translate word counts into estimated reading times. Both Longreads.com and Longform.org use the program, as does Medium. For their first assignment, students of the late New York Times media critic David Carr wrote stories with estimated reading times of fewer than five minutes.

In 2011, The Atavist Magazine began to publish longform stories—“one blockbuster nonfiction story a month, generally between 5,000 and 30,000 words.” Since its inception, The Atavist ’s stories have been nominated for eight National Magazine Awards; the magazine’s first win, for 2015’s “Love and Ruin,” was also the first time the coveted “feature writing” award went to a digital magazine. While the magazine’s founder, Evan Ratliff, employs the “longform” label to describe The Atavist ’s work, he doesn’t fret about his audience’s attention span.

“The people who are making decisions based on that, I don’t think they’re doing it based on actual research, either,” he told Columbia Journalism Review a few months after The Atavist Magazine published its first story. “I think they’re all doing it based on anecdotal experience.” Ratliff concluded, “I don’t really care if attention spans are going down in the world overall or not.” And the universe—the unknowable curator of all the components of our stories—doesn’t care either.

Love and Ruin is a new anthology of stories culled from The Atavist ’s first five years. If labels like “longform” mean anything, then Love and Ruin is also the first collection of stories that typify a new genre, a successor to titles like Wolfe’s The New Journalism and Robert Boynton’s The New New Journalism .

“‘Longform’ written storytelling . . . was, it was said, going the way of the black rhino,” Ratliff writes in his foreword. “Our magazine is built on questioning that wisdom.” Still, Ratliff doesn’t dwell on the word; if length can be considered a characteristic of each story in Love and Ruin , then it’s the one that interests him least.

Each story in Love and Ruin first appeared online, via the magazine’s proprietary platform, along with interview excerpts, original photography, embedded videos, and optional audiobook downloads. Most also came with an estimated reading time. The shortest story in Love and Ruin —Brooke Jarvis’ 10,000-word account of the year she spent working with leprosy patients in Kalaupapa, Hawaii, as the community and its last inhabitants dwindled—is classified online as a “44 minute read.” The longest stories clear 20,000 words, which means a time commitment equivalent to watching a feature film.

The ten stories in Love and Ruin fall comfortably within the word counts that The Atavist sets for its nonfiction, a range that contemporary readers expect from “longform.” But word counts and reading times are poor distinguishing features for a genre, a lackluster explanation for why these stories should appear together, and a useless tool for evaluating the rewards of the book.

The stories in Love and Ruin don’t share many sensibilities. Ratliff writes in his foreword that there is no “house style”—a suggestion that each Atavist story is told in something closer to each writer’s authentic voice. In her introduction, New Yorker staff writer Susan Orlean takes on journalism’s taxonomy problem, sets aside a few genre labels (“new journalism,” “creative nonfiction,” “longform”), and then classifies the stories in Love and Ruin as “magpie journalism.” It’s a laudatory phrase, but at a second glance it doesn’t distinguish the stories in Love and Ruin from plenty of others.

If the stories in Love and Ruin are bound by something other than glue, then it’s a sort of thematic unity, born from the same anxieties that gave us “longform.” Each story in Love and Ruin depicts its author’s struggle with the limits of investigation, representation, or understanding. “The Fort of Young Saplings” follows Vanessa Veselka’s tangential connection to a native Alaskan tribe back to the moment when that tribe’s history was overwritten. Jarvis’ story, “When We Are Called to Part,” approaches the same critical moment, when a community becomes a collection of stories, told selectively and bracketed by time. In “Mother, Stranger,” Cris Beam navigates the fog of her abusive mother’s mental illness and her own traumatic upbringing. “I didn’t have a language for my mother,” writes Beam, “probably because she didn’t have a cohesive language for herself.” The black boxes in Love and Ruin are figurative and sometimes literal; Adam Higginbotham’s “1,000 Pounds of Dynamite,” an anatomy of a failed extortion plot, features both.

Underpinned by limits and all their attendant complications, the narratives that arise from Love and Ruin are fundamentally strange and unwieldy, and as long as they need to be. Leslie Jamison’s “52 Blue” provides Love and Ruin with its most luminous prose. But the story—about a solitary whale that sings at a unique and isolating frequency, and the people drawn to the whale’s story—also offers the anthology’s best consideration of the boundaries that shape stories and their telling.

“52 Blue suggests not just one single whale as a metaphor for loneliness, but metaphor itself as a salve for loneliness,” Jamison writes. “What if we grant the whale his whaleness, grant him furlough from our metaphoric employ, but still grant the contours of his second self—the one we’ve made—and admit what he’s done for us?”

Jamison does not reach her best ideas in few words. But without the words she uses, those ideas may not be otherwise reachable. A story’s word count can sometimes be a proxy for complexity; that’s the appeal of a label like “longform” for the readers that claim to love it. But complicated stories also refute “longform.” They leave their readers with a feeling that the story and its shape are an inevitable match. How else could it have been told?

Here, then, is The Atavist ’s chief achievement with Love and Ruin : In collecting its finest “longform” nonfiction, The Atavist created an anthology that undermines its own flimsy label—and, hopefully, refutes some of our anxiety about time and attention, and the other limits that govern our lives.

The anxiety of limitation—the dread of meaning lost, to time and to space—is recurrent. “Before there were even screens in our living rooms, the same worries reared their heads,” writes Nick Bilton in I Live in the Future, and Here’s How it Works . “There was a time in the 1920s when cultural critics feared Americans were losing their ability to swallow a long, thoughtful novel or even a detailed magazine piece. The evil culprit: Reader’s Digest .”

But the condensed and excerpted stories in Reader’s Digest didn’t bring about the end of attention, or of complicated storytelling. “Reader’s weren’t abandoning long stories for short ones,” writes Bilton. “The appeal of Reader’s Digest was in the overall experience.”

In 2001, David Foster Wallace—who died in the early years of the “longform” decade and whose nonfiction posthumously bears that label—reviewed a collection of prose poems. “These putatively ‘transgressive’ forms depend heavily on received ideas of genre, category, and formal conventions,” wrote Wallace, “since without such an established context there’s nothing much to transgress against.” Do away with some of those conventions and received ideas, and a genre seems more accommodating. Labels like “longform” and “prose poem” are unnecessary limitations; they may evoke a certain shape, but they also constrain it.

A few years ago, for his introduction to The Best American Magazine Writing , James Bennet wrote a short essay that later appeared online at The Atlantic , under the headline “Against ‘Long-Form Journalism.’” Bennet argues that the label is insubstantial and misleading, and then suggests “another perfectly good, honorable name for this kind of work—the one on the cover of this anthology. You might just call it all magazine writing.” But that’s like distinguishing between “book fiction” and “movie fiction,” and besides, “magazine journalism” conflates a story with a product. A medium like print may help to shape a story, but that medium is always just a tool in the service of a narrative, and media change. There will come a time when Best American Magazine Writing needs a new title.

All the stories we tell are products of limits. Time shatters histories and then hides a few pieces. Writers construct narratives and, inevitably, omit some details. Addressing the same issue in photography, Errol Morris asked, “Isn’t there always a possible elephant lurking just at the edge of the frame?” Perhaps the elephant is unimportant to the story. And yet, there he is.

Here’s the trade-off: Narratives require that we surrender our conceptions of time and space, that we readjust our ideas of what can be known and what might be said. They can be fallible by design but still leave understanding in their wake. A story, of any length, moves readers through the world without fracturing meaning. The world fractures meaning on its own.

So perhaps we can unburden ourselves of labels like “longform.” The Atavist has already begun to do just that; in 2014, the site stopped translating word counts into estimated reading times. And perhaps we can task ourselves with something more: that we read and write closer to those circumstances that bracket our lives, and simply take the time and space we need.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Brendan Fitzgerald

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Best of the Week: November 14 - 18, 2016

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The Ins and Outs of Writing Long-Form Content

Published: June 09, 2020

Let's talk about content.

More specifically, long-form content.

Not only that, but why it's a good idea to have on your website.

Let's say you're looking for a resource about how to start an online business . You want a full rundown, concrete information, and actionable tips that will assist you begin a successful company. You're probably going to want a lengthy resource that's valuable, right?

This is the glory of long-form writing. It gives you a chance to provide highly motivated readers with a ton of value and context. Long-form content generally has a word count of more than 1,000 words — so, it’s not the shortest read.

That doesn't mean that short-form content isn't useful for your website. You should have both to serve different purposes. Let's take a minute to look at how.

Long-Form Content

On the surface, long-form content doesn't sound like it's great for user engagement. It might seem counterintuitive to give your audience more to read in order to keep them on your website longer. But it's true, and I'm going to dive into why below.

I'm here, however, to debunk that myth. Let's add a definition to the term, first.

What is long-form content?

Long-form content describes a piece of writing that is between 1,000 — 7,500 words. You might want to read long-form content to get a deep dive of complicated subjects from a robust source of writing.

The purpose of long-form content is to provide valuable information to the reader. If you write long-form pieces — and make sure those articles and essays are useful to your audience — you can increase the time spent on your site and value to your reader.

More than that, if you optimize your website for search engines and add calls-to-action in the body of your piece, you can improve lead generation. Your articles will have a higher chance of showing up on the first page of SERPs, and you can guide readers to offers that relate to the topic of your work. Similarly, for essays and academic writing, you should structure your content to make it easier for the reader to understand your question, argument, and analysis. With the growth of AI essay writers , content writers, and blog writers, making engaging and optimized content is becoming even easier.

Sounds pretty great, right?

But wait — if there's content that's long-form, there has to be a short version, right? It's important to know the difference between the two so you know how to best serve your audience.

Long-form content vs. short-form content

Short-form content can be extremely helpful to readers who want a quick answer to their queries. For instance, you can offer short-form content to provide a simple definition or explain a product in small portions . Short-form content gives your reader the information fast so their attention doesn't wane.

This type of shorter writing is generally under 1,000 words. It provides a general overview and saves readers time. Long-form content, on the other hand, goes deeper into topics.

In addition to diving deeper into topics, long-form content can aid with ranking highly on search engines and build your website's reputation.

For example, this article, about how to write a blog post , has earned thousands of views. Additionally, the average time spent on the page is about four minutes. From these metrics, we can guess that this 17-minute read, well over 1,000 words, was successful in providing value to the reader.

This doesn't mean that you should fill your blog with 17-minute reads. But it can be useful to start thinking of how long-form content can be effective for your audience. How can you provide ample writing that's actionable for readers?

If you build an archive of long-form content that's valuable for readers, you can create a reputation as a source people look to first to help them solve their questions. It's kind of like ordering a product online. You're probably more likely to order from a site you've used many times before, that has proved to be reputable, instead of trying out a brand new ecommerce option.

Let's look at another reason why long-form, valuable writing is successful: page rank on Google. Backlinko found that websites with a high "time on site" are more likely to rank highly on search engine results pages (SERPs).

When a search query is typed into Google, the search engine crawls websites for content that will help solve that user's query. Web pages that have a longer time spent on site than others suggest to Google that browsers found that information important enough to stay on that page.

As a result, Google is more likely to suggest that page above others. (Don't forget that a page optimized for SEO is also a huge boost to improving rank).

So now you know why long-form content is important to have on your site: It provides values to readers, can earn you a reputable reputation, and brings more eyes to your site. But what does successful long-form content look like? Let's take a look at some examples.

Long-Form Content Examples

Before we talk about how to write long-form content, let's look at some effective examples. These examples show how long-form content can be optimized for the reader's comprehension.

1. Hayley Williams Isn't Afraid Anymore by Rolling Stone

This long-form profile about solo artist Hayley Wiliams, written by Brittany Spanos for Rolling Stone , does a great job of performing other content produced by Rolling Stone about the same topic, or those that are similar.

Within the profile, other works previously done by Williams or her rock band, Paramore, are featured and hyperlinked to previous RS articles that are applicable. For instance, the word "Paramore" was hyperlinked to an internal tag of the same name, showing all previous RS posts that mentioned the band.

A particularly intriguing mention of past works related to the topic, Williams, comes up in the sidebar of the feature. There, you can find previous music reviews of the singer/songwriter's releases. This is a visual way to promote past content, and one that catches the attention of readers.

Image Source

If you want to include other works in your long-form content that relate to the article, consider an approach similar to this one. You'll give the reader a break from reading the piece to queue up similar posts for later. Additionally, you'll provide more value to the article by offering up supporting ideas.

2. Getting Started with Google Remarketing Ads by Mailchimp

Mailchimp is a marketing software platform. This post is a guide to navigating setting up Google Remarketing Ads. Complete guides about a topic that pertains to your industry are a wonderful example of a long-form content piece that you can add to your blog.

What's great about this article is that it shows off a table of contents, different languages to read in, and social sharing options.

Adding in a table of contents helps the reader easily navigate through a longer piece if they are only interested in one section. And international readers are able to read in their native language with the opportunity to translate the text.

3. Delivering Emails with Litmus by Litmus

This long-form content is a transcription of a podcast episode that was embedded into the post. I get it: Even with software available, it's taxing work to do a transcription. Even this short, 18-minute episode was not an easy feat to transpose.

However, if you create YouTube videos or podcasts, a transcription can make your audio/video content accessible to audience members who are hearing impaired.

If for some reason, the embed of the audio file doesn't work or a quote doesn't come through clearly, the non-hearing impaired listeners can identify what was said without having to mentally fill in the blanks. I would find a transcription helpful if I were writing an article and wanted to pull a quote, or if I wanted directions on how to use software and didn't want to keep rewinding.

4. 77 Essential Social Media Marketing Statistics for 2020 by HubSpot

Data is great material for a long-form post, like this one from HubSpot. This post is classified as a long read, but because the statistics included are short and formatted in a comprehensible way, readers are able to get through the post easily.

When you section off stats, for instance, "General Social Media Marketing Statistics," and "Facebook Statistics," you make it easier for readers to jump to the section they're looking for. Additionally, the words are sectioned off for organization.

Now that you've seen some examples, you're probably stoked to get started writing your long-form content. Before you do, take a look at the tips below to make sure your work is actionable, comprehensive, and accessible.

How to Write Long-Form Content

Outside of concrete grammar rules, like subjects and predicates, there's no "right" or "wrong" way to write. That said, there are ways to create content that's digestible and useful to readers. I'm going to be referencing using HubSpot, but feel free to use similar software to format your post.

Writing Long-Form Content

- Form your paragraphs in comprehensible sections.

- Section off your main ideas.

- Make sure your thoughts are organized.

- Describe the 'so what?' of each section.

- Keep a conversational tone throughout your piece.

- Hook the reader with an engaging introduction.

- Add visuals to break up long sections of text.

1. Form your paragraphs in comprehensible sections.

When you sit down to write your long-form piece, take note of paragraph structure. To optimize your piece for readability, keep paragraphs short. Ideally, paragraphs shouldn't be longer than three sentences, unless it makes sense to add more.

Let's talk about that exception. If you're writing a paragraph where the impact is best presented in rhetorical questions, for example, it might look better to keep those questions in the same section.

Does the paragraph have an effect on the reader? Do you effectively get your point across? How will you use paragraphs to make content digestible? Are you pulling the reader in with your formatting?

In some cases, it’s alright to ignore the three-sentence rule if, like above, each sentence flows together. Adding an entire new paragraph just to fit that extra question doesn't provide the same effect and does little for formatting.

2. Section off your main ideas.

Headers are your friends. H2s, H3s, and H4s can be found in almost every writing tool, such as Docs, Word, WordPress, HubSpot, and other software programs. Headers help you guide the reader through the main ideas of your piece by breaking off your content into sections.

For instance, in this piece, the main idea of this section is "How to Write Long-form Content," so I made it the H2, which is generally used for titles and main ideas. The list items underneath this section are formatted into H3s, which support that main idea. If I were to add subsections underneath any of these list items, they would be H4s.

Headers split up long sections of your text and assist with organization. If this piece lacked these items, it would be pretty difficult to navigate. Additionally, when I'm outlining a long-form post, planning headers in advance supports me in writing effective content — I can visualize what I need to add to make each portion effective.

3. Make sure your thoughts are organized.

It's crucial for long-form content to make sense. So, before you press "publish," read over your piece for organization. Ask yourself if your piece has a beginning, middle, and ending that readers can follow.

Your sections should have a logical format. For example, in this piece, I wouldn't have jumped into providing steps to writing long-form content without first explaining the definition. Think about if Cinderella started with the royal wedding, then circled back to Cinderella cleaning the house — that wouldn't make much sense.

Readers could get confused if your work isn't organized in a logical way, so be mindful of formatting.

4. Describe the 'so what?' of each section.

Long-form content has an added difficulty of keeping readers engaged throughout the piece. To combat this, make every paragraph count. This will do two things: Avoid unnecessary added length, and keep readers compelled.

When you write a longer piece, you don't need to add extra information that doesn't serve the purpose of the post. This can lead to convoluted, intricate paragraphs or sections that don't make much sense.

To keep readers interested, get to the point. End sections with why the readers should care. This ensures they get the most out of your article.

5. Keep a conversational tone throughout your piece.

This tip circles back to keeping the attention of viewers. Instead of taking an extremely formal tone, it's okay to lighten up a little. In college, whenever I read academic textbooks, it was hard to keep my focus. The highly technical language couldn't keep my interest.

Unless your article is an academic journal, you don't have to use complicated language to seem like an expert on your topic. If you give well, researched, thoughtful, and actionable content, readers will find your post useful. Trying to sound "too" formal could actually have the negative effect and leave your readers feeling like they don't have any takeaways.

6. Hook the reader with an engaging introduction.

Depending on the platform you use to post your long-form article, the estimated read time is given to the reader. For instance, on the HubSpot Blog, when you click on an article, you can see the read time underneath the title.

Some people might see that read time and immediately feel compelled to skim, especially if it's something like 18 minutes. To hook the reader, make your introduction something that grabs their attention.

One of my colleagues is great at this — he will present an anecdote in the beginning of the piece and continues to use that anecdote to illustrate points throughout the rest of the article. It leads to gripping posts I’m sad to finish.

If you can't think of a story or life experience to use to pull the reader in, give a relevant statistic in the above-the-fold information. What you present above the fold is what's going to make that reader think, "Oh, I have to keep going!"

7. Add visuals to break up long sections of text.

In addition to breaking up long sections with short paragraphs and headers, eye-catching visuals are another way to break up long sections and keep the reader engaged. Personally, if I'm skimming an article and see a picture or graph included, I'm immediately drawn back into the piece.

You don't always have to use images or videos. Blockquotes and anchor text are also amazing tools. Blockquotes are those huge quotes you see highlighted in articles, and anchor text directs your reader back to sections you reference earlier in the piece.

Generally, you can find these tools within the software you're using. In HubSpot, blockquotes can be added by going to the header tab, and anchor text can be found by opening the "Insert" category.

Remember to have fun with your long-form content. Writing is a creative process, and readers can tell when something was a drag to write (It's probably a drag to read).

Long-form writing has its own advantages over short-form content, even though the latter might be the quickest way to beef up your archive. It's so valuable to have longer pieces on your site, and readers will definitely find them useful.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

27 Case Study Examples Every Marketer Should See

How to Write a Case Study: Bookmarkable Guide & Template

![long form essay meaning 7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]](https://knowledge.hubspot.com/hubfs/contenttypes.webp)

7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]

How to Market an Ebook: 21 Ways to Promote Your Content Offers

![long form essay meaning How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/listicle-1.jpg)

How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]

![long form essay meaning What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]](https://53.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/53/business%20whitepaper.jpg)

What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]

What is an Advertorial? 8 Examples to Help You Write One

How to Create Marketing Offers That Don't Fall Flat

20 Creative Ways To Repurpose Content

16 Important Ways to Use Case Studies in Your Marketing

Save time creating blog posts with these free templates.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

longform articles & essays 101

A comprehensive guide on longform journalism: favorite sites, newsletters, and a starter pack of my favorite articles.

what is longform journalism and why should you read it?

Longform journalism is essentially an article that is a long read, typically ranging between 2,000 to over 10,000 words. The lengthy word count allows for more detailed, developed pieces of writing that have room to expand and truly breathe. The content can vary, from investigative reporting to personal essays, from interviews to short fiction published in magazines and newspapers.

In the last year or so, I’ve begun reaching for longform essays often. It’s long enough to feel as satisfactory as a good nonfiction book, but it is also short enough that I can read it on my commute to work or other places. They are also just massively underrated outlets for reading—they are incredibly diverse in content and style and very informative. Articles pack the same depth of analysis and research as nonfiction books while being more accessible due to their short length.

I constantly strive to keep myself educated and knowledgeable even if I’m not in a classroom setting. Longform articles fill that education void for me, so I always try to make it a habit of reading at least one article daily, even when I don't have time to read actual books. It also increases my attention span (something I direly need to do because social media doomscrolling has been killing it). I treat these essays and articles like brain food, so it's always fun to learn something new.

where do you find articles & essays?

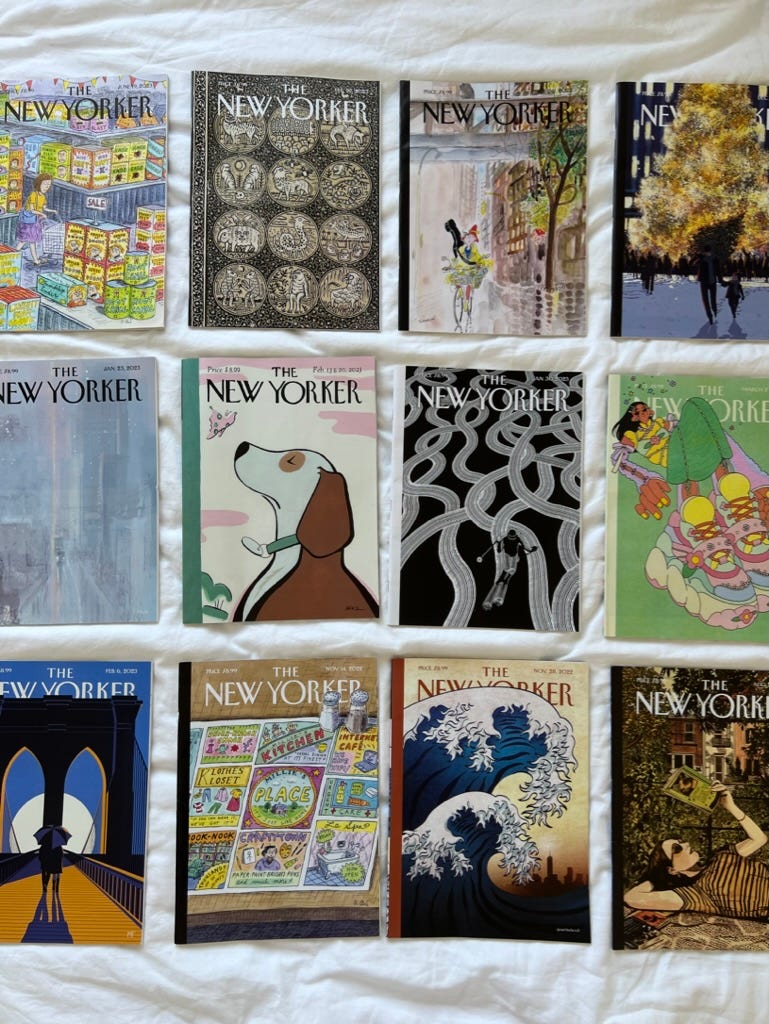

My go-to sites for articles are: The New Yorker, Aeon, The Paris Review, and The Atlantic. On these sites, will always be able to find a fantastic article on so many different topics.

Here is a big list of around 30 newspapers, magazines, and sites that have excellent long-form articles and never let me down. I tried to put them in order of the ones I read from the most, with descriptions of what you can expect to find on each magazine/newspaper.

The New Yorker : An American magazine that covers everything from politics to culture to art to fiction. Most articles are gems, and many of my favorite writers also write longform content on here every now and then. Here are some of the journalists I consistently follow and read from: Patrick Radden Keefe (true crime), Kathryn Schulz (anything from science to geography to memoirs), Peter Schjeldahl (art), Rachel Syme (profiles), and Jia Tolentino (feminism and culture).

Aeon : The best free magazine out there. Aeon covers essays about philosophy , psychology , science , society and culture . Every article is so well researched and written. So many of my favorite articles of all time are from this site, and everything feels like brain food. Here is an article about sulking , one about nostalgia , and one about female friendships .

This post is for paid subscribers

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of long-form

Examples of long-form in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'long-form.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1961, in the meaning defined above

Dictionary Entries Near long-form

Cite this entry.

“Long-form.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/long-form. Accessed 25 Aug. 2024.

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, 31 useful rhetorical devices, more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics Training

- Ethics Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- IFCN Grants

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

What do we mean by ‘longform journalism’ & how can we get it ‘to go’?

A Kickstarter project run by two journalists raised $50,000 in just 38 hours last week and has raised a total of $87,297 so far. The goal of the project , called “ Matter ,” is to “publish a single piece of top-tier long-form journalism about big issues in technology and science. That means no cheap reviews, no snarky opinion pieces, no top ten lists. Just one unmissable story.”

The project raises interesting questions about what constitutes longform journalism. We know that technology has renewed attention to longform journalism in recent years. But it’s also changed how we think about it.

Do we define longform by the quality of the writing? By the amount of time it took to write? By the research it entailed? Or do we define it by length? The longform journalism site Longreads, for instance, asks people to “post their favorite stories over 1,500 words.”

These conceptual differences matter, says New York Times science reporter Natalie Angier . When I asked her about the “Matter” Kickstarter project, Angier said she’s been wondering what people mean when they say “longform” journalism. She tends to equate it less with length and more with depth of reporting.

“Even as the editors have cut back on the column inches they’ll allot to my work (or anybody else’s), I continue to treat every piece I write as though it were an in-depth feature,” Angier said. “I can’t imagine writing about science any other way.”

A writer or site that continuously produces quality content drives people come back. But given how fast news comes at us these days, and how many choices we have on the Web, quality longform stories can easily get lost.

Mark Armstrong, founder of Longreads and editorial adviser of Read it Later , says that when it comes to content on the Web, “it feels like we’re living in a Hot Dog-Shooting Terrordome.”

In a story published earlier today , Armstrong said publishers are faced with a “seemingly unsolveable problem” — how to embrace the increasing demands for content without losing sight of their commitment to quality.

“But there’s a bigger challenge for the media business,” Armstrong wrote. “How can we change the ecosystem and evolve to a model that puts renewed attention on quality over quantity?”

Crowdfunded projects like “Matter” are one possible solution. But beyond that, Armstrong says, news sites need to find more ways to make content portable.

“Let people take content with them, and they will soon value it more highly than if it is shot at them,” Armstrong said. “Content creators will be rewarded with a longer social lifespan for the stories and videos they work so hard to create. And that ultimately lifts the value of a media brand.”

It seems, then, that the definition of longform can’t be limited to length or even quality. Increasingly, longform stories need to have staying power, and we need more tools to give them a greater lifespan. In keeping with the hot dog analogy, we need more “take-out” bags for content, Armstrong said.

Read it Later, which has more than 4 million users, enables people to save stories from their computer, smart phone or iPad , and makes them available for offline use. Read it Later data shows that, on average, users keep a video or article in their queue for 96 hours before marking it viewed. As this Bit.ly study shows , that’s a pretty long time compared to the life span of stories shared on Twitter.

The more we can give readers tools to control how and when they engage with content, the easier it will be for them to read content that may require more careful attention — either because it’s long, in-depth, or both.

Readers have a hunger for visionary thinkers and big ideas, Angier said. Whether or not people will pay for this content is a little less clear.

“People want substance, and insight, and optimism with a forebrain, and again where can you turn for any of that but to science? But will people pay to read long, provocative, beautifully crafted science stories? And will ‘Matter’ pay writers a living wage to meet that desire? Consider me a hopeful skeptic.”

Opinion | Media reaction to Kamala Harris’ acceptance speech

It was a speech that wowed not only the obviously partisan crowd in Chicago, but many of the media commentators covering it.

Fact check: How accurate was Kamala Harris’ 2024 DNC speech in Chicago?

Harris leaned into several key policy themes: abortion rights, voting rights and support for Ukraine as it fights a continuing Russian invasion

LIVE: Fact-checking Kamala Harris’ 2024 DNC speech in Chicago

PolitiFact is live fact-checking the fourth and final night of the 2024 Democratic National Convention

Opinion | Who has been the DNC’s most surprising speaker so far?

It’s Stephanie Grisham, a former White House press secretary for Donald Trump who now supports Kamala Harris for president

Fact check: What Walz, Buttigieg, Clinton and others got right and wrong at Day 3 of the DNC

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz accepted his party’s vice presidential nomination on the Democratic convention’s third night

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write an Essay

I. What is an Essay?

An essay is a form of writing in paragraph form that uses informal language, although it can be written formally. Essays may be written in first-person point of view (I, ours, mine), but third-person (people, he, she) is preferable in most academic essays. Essays do not require research as most academic reports and papers do; however, they should cite any literary works that are used within the paper.

When thinking of essays, we normally think of the five-paragraph essay: Paragraph 1 is the introduction, paragraphs 2-4 are the body covering three main ideas, and paragraph 5 is the conclusion. Sixth and seventh graders may start out with three paragraph essays in order to learn the concepts. However, essays may be longer than five paragraphs. Essays are easier and quicker to read than books, so are a preferred way to express ideas and concepts when bringing them to public attention.

II. Examples of Essays

Many of our most famous Americans have written essays. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson wrote essays about being good citizens and concepts to build the new United States. In the pre-Civil War days of the 1800s, people such as:

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (an author) wrote essays on self-improvement

- Susan B. Anthony wrote on women’s right to vote

- Frederick Douglass wrote on the issue of African Americans’ future in the U.S.

Through each era of American history, well-known figures in areas such as politics, literature, the arts, business, etc., voiced their opinions through short and long essays.

The ultimate persuasive essay that most students learn about and read in social studies is the “Declaration of Independence” by Thomas Jefferson in 1776. Other founding fathers edited and critiqued it, but he drafted the first version. He builds a strong argument by stating his premise (claim) then proceeds to give the evidence in a straightforward manner before coming to his logical conclusion.

III. Types of Essays

A. expository.

Essays written to explore and explain ideas are called expository essays (they expose truths). These will be more formal types of essays usually written in third person, to be more objective. There are many forms, each one having its own organizational pattern. Cause/Effect essays explain the reason (cause) for something that happens after (effect). Definition essays define an idea or concept. Compare/ Contrast essays will look at two items and show how they are similar (compare) and different (contrast).

b. Persuasive

An argumentative paper presents an idea or concept with the intention of attempting to change a reader’s mind or actions . These may be written in second person, using “you” in order to speak to the reader. This is called a persuasive essay. There will be a premise (claim) followed by evidence to show why you should believe the claim.

c. Narrative

Narrative means story, so narrative essays will illustrate and describe an event of some kind to tell a story. Most times, they will be written in first person. The writer will use descriptive terms, and may have paragraphs that tell a beginning, middle, and end in place of the five paragraphs with introduction, body, and conclusion. However, if there is a lesson to be learned, a five-paragraph may be used to ensure the lesson is shown.

d. Descriptive

The goal of a descriptive essay is to vividly describe an event, item, place, memory, etc. This essay may be written in any point of view, depending on what’s being described. There is a lot of freedom of language in descriptive essays, which can include figurative language, as well.

IV. The Importance of Essays

Essays are an important piece of literature that can be used in a variety of situations. They’re a flexible type of writing, which makes them useful in many settings . History can be traced and understood through essays from theorists, leaders, artists of various arts, and regular citizens of countries throughout the world and time. For students, learning to write essays is also important because as they leave school and enter college and/or the work force, it is vital for them to be able to express themselves well.

V. Examples of Essays in Literature

Sir Francis Bacon was a leading philosopher who influenced the colonies in the 1600s. Many of America’s founding fathers also favored his philosophies toward government. Bacon wrote an essay titled “Of Nobility” in 1601 , in which he defines the concept of nobility in relation to people and government. The following is the introduction of his definition essay. Note the use of “we” for his point of view, which includes his readers while still sounding rather formal.

“We will speak of nobility, first as a portion of an estate, then as a condition of particular persons. A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny; as that of the Turks. For nobility attempers sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles. For men’s eyes are upon the business, and not upon the persons; or if upon the persons, it is for the business’ sake, as fittest, and not for flags and pedigree. We see the Switzers last well, notwithstanding their diversity of religion, and of cantons. For utility is their bond, and not respects. The united provinces of the Low Countries, in their government, excel; for where there is an equality, the consultations are more indifferent, and the payments and tributes, more cheerful. A great and potent nobility, addeth majesty to a monarch, but diminisheth power; and putteth life and spirit into the people, but presseth their fortune. It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings. A numerous nobility causeth poverty, and inconvenience in a state; for it is a surcharge of expense; and besides, it being of necessity, that many of the nobility fall, in time, to be weak in fortune, it maketh a kind of disproportion, between honor and means.”

A popular modern day essayist is Barbara Kingsolver. Her book, “Small Wonders,” is full of essays describing her thoughts and experiences both at home and around the world. Her intention with her essays is to make her readers think about various social issues, mainly concerning the environment and how people treat each other. The link below is to an essay in which a child in an Iranian village she visited had disappeared. The boy was found three days later in a bear’s cave, alive and well, protected by a mother bear. She uses a narrative essay to tell her story.

VI. Examples of Essays in Pop Culture

Many rap songs are basically mini essays, expressing outrage and sorrow over social issues today, just as the 1960s had a lot of anti-war and peace songs that told stories and described social problems of that time. Any good song writer will pay attention to current events and express ideas in a creative way.

A well-known essay written in 1997 by Mary Schmich, a columnist with the Chicago Tribune, was made into a popular video on MTV by Baz Luhrmann. Schmich’s thesis is to wear sunscreen, but she adds strong advice with supporting details throughout the body of her essay, reverting to her thesis in the conclusion.

VII. Related Terms

Research paper.

Research papers follow the same basic format of an essay. They have an introductory paragraph, the body, and a conclusion. However, research papers have strict guidelines regarding a title page, header, sub-headers within the paper, citations throughout and in a bibliography page, the size and type of font, and margins. The purpose of a research paper is to explore an area by looking at previous research. Some research papers may include additional studies by the author, which would then be compared to previous research. The point of view is an objective third-person. No opinion is allowed. Any claims must be backed up with research.

VIII. Conclusion

Students dread hearing that they are going to write an essay, but essays are one of the easiest and most relaxed types of writing they will learn. Mastering the essay will make research papers much easier, since they have the same basic structure. Many historical events can be better understood through essays written by people involved in those times. The continuation of essays in today’s times will allow future historians to understand how our new world of technology and information impacted us.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Long Form, Always

The NY Times contributing writer & National Magazine Award finalist on new directions in narrative journalism, advice for emerging writers, the importance of meticulous research, and what led her to her career as a journalist.

At the upcoming 2015 Creative Nonfiction Writers’ Conference , Maggie will participate in the panel discussion, “Fact & Story: A Balancing Act.” Creative Nonfiction ’s Shannon Swearingen spoke with Maggie about new directions in narrative journalism, advice for emerging writers, the importance of meticulous research, and what led her to her career as a journalist. Read her work here .

CNF : You have written about many social issues, including immigration, race, and poverty. Do you consider yourself a writer or a social rights proponent who uses writing as her medium? Or is it even necessary to establish a difference?

JONES : I’m first and foremost a journalist—but one who deeply cares about social justice issues and wants the public to learn about people who often don’t have a voice in the mainstream media. But part of being a journalist is that I’m willing to have my ideas turned upside down based on what I see and learn during reporting.

CNF : What first drew you to journalism and led you to your career with The New York Times ?

JONES : I was interested in long form, always, but I came to magazine journalism slowly. At first, I wanted to be a documentary filmmaker and started out as a researcher for a public TV documentary producer. Then I wrote for newspapers with the goal of learning to report so that I could move into magazines. First it was women’s magazines—when there used to be a far more robust women’s magazine market—and bit by bit I worked my way into small and then larger pieces for The New York Times Magazine .

CNF : How do you determine whether a piece you’re working on will be in the first or third person?

JONES : Unless it’s an essay, my pieces are rarely in the first person. I may dip in and out at times when it seems useful or relevant to do so: for example, in a few pieces I’ve done on adoption where I brought in my own experiences as an adoptive parent.

CNF : What do you find appealing about writing in the first person?

JONES : I’m a careful and reluctant first-person writer. I’m not inclined to open up my personal life for publication. So when I do, I want it to be with purpose. But the reason I do like to do it at times is more about format—I like the variety of writing more essayistic prose.

CNF : Do you gravitate toward first-person narratives as a reader?

JONES : Not necessarily. Foremost, I gravitate toward beautiful writing in any form.

CNF : What do you consider to be beautiful writing?

JONES : By beautiful writing in nonfiction, I mean writing that transports me somewhere—where characters, scenes, places are rendered with the detail and the best devices of fiction, while adhering to the rules of journalism.

CNF : What advice do you have for writers on how to get readers to care about their stories? How does one make the personal universal?

JONES : You get readers to care about stories with meticulous and intensive reporting and narrative writing that pulls readers in.

CNF : How important is it that your articles be universal?

JONES : If you mean “universal” in terms of readers “getting it” or understanding a character: Obviously I want to make my stories accessible to everyone. I want to show characters that, if you delve deeply enough, you feel that they share qualities with the rest of us. But also characters and stories are individual, so not every person or story is “universal.”

CNF : How do you think the art of journalism has evolved throughout your career?

JONES : Journalism in general? Or narrative journalism? Lyrical, well-reported narrative journalism has been around far longer than I’ve been alive.

CNF : In what new directions do you see writers pushing the form?

JONES : I’m not convinced that writers are pushing the form so much as the form itself is expanding. It’s far more about how multi-media is used: for instance, Serial and its week-by-week method of telling a story that leaves you hanging and in which you get a window into the reporter’s process. Also, the way that the Atavist uses its platform to tell stories that don’t fit neatly into conventional magazine formats.

CNF : Are your articles informative, creative, or both? How do you craft them? (i.e., do you seek to tell the facts, present a story, or both?)

JONES : Wow, that’s a big question on craft. No two articles are alike. Some are more heavily narrative than others; some start with an anecdotal lead, some don’t. Some are chronologically told, while in other cases, it makes more sense to weave back and forth in time. As for the informative part, I almost always need to explain some public policy or legal issues, somewhere in the story. But my goal is that the “informative” parts not feel like medicine.

CNF : You appear to immerse yourself in the stories on which you are reporting: for example, you spent time in the girls’ dormitory of a charter boarding school for The New York Times article “The Inner-City Prep School Experience.” Do you consider this a crucial part of your research process? What other types of research do you do?

JONES : It’s absolutely crucial. I write long-form narrative stories with the luxury of long deadlines. I can’t—and luckily don’t have to—hop in and out of a place and gather a few facts and sit down to write. I need to get to know people, understand how they live, what they think about, what their hopes are. There is no replacement for time spent with sources.

CNF : Do you generally have a set process that you follow for each article you write, or does it just depend on the piece?

JONES : My process varies by subject and by timing. Typically I try to immerse myself deeply in a subject—reading books about the topic, talking to experts in advance—before immersing myself in the on-the-scene reporting. That’s just not always possible: For a recent [article], I had to travel quickly because of timing and had to make do with what I could absorb quickly and do much of the background reading and reporting later.

CNF : What’s the most important thing you’ve learned about publishing your work?

JONES : Not sure I understand this question. If it’s about how to get my work published, it’s about not giving up. This is a really hard field to be in, and it requires a thick skin. You have to get in the door with editors by giving them really well-thought-out ideas and pitches and by working hard—reporting thoroughly, meeting deadlines, taking criticism well—so they will want to work with you again and again.

CNF : What was the biggest mistake you made as an emerging writer? What about as an established writer?

JONES : Probably the biggest mistake in the beginning was lack of confidence. For example, if I didn’t hear from an editor about a story pitch, I didn’t always pursue it further. As an established writer, I’m still making plenty of mistakes—including hearing an editor’s voice in my head when I’m reporting and panicking that the story isn’t going well when I’m in the field, when instead I just need to sit and listen and see what emerges.

CNF : If you could go back to the start of your career, what advice would you give yourself?

JONES : I would focus on getting all the tools as early as possible: learn how to report (which I did by writing for newspapers), and focus on narrative writing. Along with writing as a daily reporter for newspapers, being a fact checker for a magazine is a great way to start. I can’t overstate how much appreciation I have for fact checkers—and copy editors—and the incredible ways they have helped me over the years.

CNF : How do you handle rejection?

JONES : Better than I used to. I’m not terribly thick-skinned, but getting a story idea rejected or having my editor suggest I need to reorganize 80% of my story comes with this work.

CNF : Do you have any advice for new writers or journalists on how to move past rejection and gain confidence in their abilities?

JONES : If it’s any comfort—and it should be—every writer gets rejected. You just have to move on and not be paralyzed by it. When I started out, I tried to have several proposals out to editors at one time, so I wasn’t invested in only one story. Also, I’d tell new writers not to expect to land on the cover of The New York Times Magazine or get a story in The New Yorker the first time around. A few souls do that, I suppose. But most of us have to slug it out far more modestly for a long, long time.

CNF : What role does social media play in your career as a writer?

JONES : As long as it’s not a time suck, it’s a good tool. I have found story ideas through Facebook, sources through Facebook and Twitter, etc. But what an incredible way to waste time if you aren’t careful.

CNF : How have technology and the age of internet impacted your career?

JONES : It’s provided more outlets and more ways to publicize my work. But at the core, my work and the way I do it haven’t changed very much at all. I’m still an old-fashioned reporter, relying on tons of phones calls, spending time with people in person, and slogging away at writing as I’ve always done.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ lawng -fawrm , long ‐ ]

A long-form article can illuminate and humanize your subject.

a long-form TV drama whose story unfolds over ten episodes; long-form comics and graphic novels.

I've started writing more long-form on my blog.

Word History and Origins

Origin of long-form 1

Compare Meanings

How does long-form compare to similar and commonly confused words? Explore the most common comparisons:

- short-form vs. long-form

Example Sentences

The medium, the long form, rewards… if not ambiguity, then elements that create multiple reactions in the viewer.

When I want to think deeply, I write out my thoughts as long-form narratives or do mind mapping on my computer.

I was actually telling a story, and line by line when you put it all together it forms a long-form narrative of the trip.

Using long-form poetry, they crafted something that was simultaneously satirical and celebratory of the art of dressing well.

For proof good long-form journalism should never die, read Dan Barry's five part series on Elyria, Ohio.

This species is very distinct on account of its long form, and curved lower face, as well as its outer surface.

The emaciation of his long form was plainly seen through the single scarlet blanket which covered it.

My own preference is for the long form, because oftentimes the short form is not perfectly clear to the legislator.

"Good morning, Mr. Rattar," said he, throwing his long form into the clients' chair as he spoke.

A few minutes later the long form of the explorer appeared above the incline.

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

The Longform Article: Why you need it

Table of Contents

The longform article is meant to solve problems. But should you use long form pieces for every business problem? Keep reading to find out why it can be beneficial for your business and in your marketing.

Traditionally, the longform article is a type of journalistic writing that focuses on research and analysis in depth. It’s not just a story about an event and a person. It’s a multi-part article that attempts to answer the questions, “Why did this happen”? and “What happens next”?

You can see how this would lend itself well to content marketing.

Let’s say a customer is looking for a resource about starting an online business. They expect that this will provide a complete overview of everything they need to know, as well as actionable tips for starting successful businesses.

If you wanted to provide this information because it relates to your business, long form content would be perfect for your website. This is because it gives you the opportunity to explain how to start a business in depth. It also gives you the opportunity to mention your products and services in passing.

There is no set definition for long form content. Content is often written and includes multimedia elements, including podcasts, audio effects, videos, images, animations, infographics, and much more.

There was a time when a long form article was considered to be anything over 1,000 words. Now, because of changes to Google’s algorithm, long content frequently crosses into the 2,000 mark.

Longform journalism is writing in an essay form and over a long period of time, often over multiple weeks or months. It is not specific to journalism, and can be found in magazines or books.

Long form journalism is useful for providing in-depth analysis and understanding. Meanwhile, long form content marketing is a good tool for educating a specific audience about a particular subject.

Quality content that demonstrates your brand’s expertise, industry knowledge, and original insight can be useful.

Like long form journalism, a piece of long content on your website asks questions. It goes beyond basic explanations of some topic in your industry.

When you offer long form content, you can educate customers through your funnel and help them succeed, even after you’ve closed the deal. They can find helpful user guides, troubleshooting guides, and ideas for making the most of your products and services.

Your target audience has qualified you as a great prospect if they read all the way through your long form content. Media and other companies are increasingly investing in long form content.

This is because long form article content has been shown to rank on the first page of Google. Search engine algorithms are designed to evaluate high-quality content, which often means long form meets the ‘intent’ of the search query.

Providing valuable information to the reader is the purpose of long-form content. Make sure your long form content is useful to your audience. You can increase the time spent on your site and the value you offer to your readers.

People have often talked about the benefits of long form versus its shorter formed cousin.

Short form is often truncated to a few paragraphs and is shared on a variety of platforms. It’s an easy way to get your message out. It’s great to use when you just want your reader to have a quick overview of your product or service.

Longform content is so comprehensive that it serves as a good source for short form content. Content and formats of long form can be extracted, repackaged, and repurposed to share with social media or incite readers to convert.

You can get many more references, infographics, lists, tutorials, webinars, step-by-step guides, and social media threads from the same longform article.

Because long form has become so important to business and marketing, it’s important that you know how to write it well.

Following these steps should help you get long form writing right:

1. Work hard on your paragraphs

Paragraphs are the building block of writing. Let’s say you write a longform article post and include paragraph after paragraph of business jargon-filled text.

If you cut-and-paste paragraphs out of the middle of a post, that post usually ends up being hard to comprehend. Therefore, make it a priority to write paragraphs that are good.

Start with a dominant idea or point. Think about the first sentence of your paragraph. What is the dominant idea that you want readers to understand? This sentence usually has a hook or a powerful question that gets readers interested.

A hook is a question or claim that you want readers to understand. A hook gets readers to click through and read the rest of your paragraph. It’s a good idea to spend extra time on your first sentence.

2. Rewrite main ideas until they are easily understood.

Business writing often contains complex concepts. Long form is a form of writing that tries to convey complex subjects without sacrificing clarity and detail.

Content must make sense. Read over your piece for structure before you press submit. See if there is a clear beginning, middle and end that is easy to understand.

Organize your sections in a logical way. If your work is not organized in a logical way, readers are going to get confused.

3. Keep a conversational tone throughout your piece.

It’s important to sound as though you are talking to the reader. You allow the reader to formulate their own thoughts through the use of personal pronouns and questions.

Your audience is reading this out of sheer curiosity as they power down their work day. Make it easy for them to get what you’re trying to say. Use casual, playful language.

Striving to write in a high-level language style will only lead you to write unnatural sounding works that will go over the reader’s head.

4. Start your introduction by engaging the reader.

It’s harder to hold reader’s attention these days. There is so much more to read and so much less time to read it in.

This is why you should catch your reader’s interest from the beginning. Try to intrigue your reader with something that they’ll really want to read about. Share a personal anecdote.

This will put your reader at ease. It helps them feel as if they are having a conversation with you and not just a boss or teacher giving them push.

Your narrative form and story behind a product or service will be noticed by readers, particularly those who will eventually end up buying.

5. Use Visuals for breaking up longform article text.

Nobody likes looking a huge wall of text. This is why a graphic element is so important for your content.

You can use infographics, pictures, graphs, charts, pictographs and more to make your article more visual and more readable. This will only add value and increase the chances of people remaining on your site and clicking through to your content.

Just make sure the graphic is not too busy and easy to understand and that it helps break up the text.

The longform article is a cornerstone of journalism and of the digital world. After reading this article, you should be able to understand the benefits of long form articles .

By learning how to write long form well, you can write better content more effective and add more value to your content.

Pam is an expert grammarian with years of experience teaching English, writing and ESL Grammar courses at the university level. She is enamored with all things language and fascinated with how we use words to shape our world.

Explore All Long-form Articles

Write longer essays with these tips.

Almost all advice about how to make your essay longer tells you to do gimmicky things that will lead to…

Write a Unique 2000 Words Article in Record Time

Writing a 2000 words article in a short period can seem like an impossible dream for many writers. Are you…

The Ultimate Guide to How Long Should a Blog post be

How long should a blog post be is an often asked question. The answers are different according to whom you…

Interesting Basic Tips How to Make Your Essay Better

There might be a lot of tips you see online on how to make your essay better. An essay is…

The longform article is meant to solve problems. But should you use long form pieces for every business problem? Keep…

How Many Pages is 3000 Words: A Key to Convert Word Count

To start, let’s define what a standard 3,000-word essay should look like. How many pages is 3000 words falls anywhere…

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How long is an essay? Guidelines for different types of essay

How Long is an Essay? Guidelines for Different Types of Essay

Published on January 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The length of an academic essay varies depending on your level and subject of study, departmental guidelines, and specific course requirements. In general, an essay is a shorter piece of writing than a research paper or thesis .

In most cases, your assignment will include clear guidelines on the number of words or pages you are expected to write. Often this will be a range rather than an exact number (for example, 2500–3000 words, or 10–12 pages). If you’re not sure, always check with your instructor.

In this article you’ll find some general guidelines for the length of different types of essay. But keep in mind that quality is more important than quantity – focus on making a strong argument or analysis, not on hitting a specific word count.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Essay length guidelines, how long is each part of an essay, using length as a guide to topic and complexity, can i go under the suggested length, can i go over the suggested length, other interesting articles.

| Type of essay | Average word count range | Essay content |

|---|---|---|

| High school essay | 300–1000 words | In high school you are often asked to write a 5-paragraph essay, composed of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. |

| College admission essay | 200–650 words | College applications require a short personal essay to express your interests and motivations. This generally has a strict word limit. |

| Undergraduate college essay | 1500–5000 words | The length and content of essay assignments in college varies depending on the institution, department, course level, and syllabus. |

| Graduate school admission essay | 500–1000 words | Graduate school applications usually require a longer and/or detailing your academic achievements and motivations. |

| Graduate school essay | 2500–6000 words | Graduate-level assignments vary by institution and discipline, but are likely to include longer essays or research papers. |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In an academic essay, the main body should always take up the most space. This is where you make your arguments, give your evidence, and develop your ideas.

The introduction should be proportional to the essay’s length. In an essay under 3000 words, the introduction is usually just one paragraph. In longer and more complex essays, you might need to lay out the background and introduce your argument over two or three paragraphs.

The conclusion of an essay is often a single paragraph, even in longer essays. It doesn’t have to summarize every step of your essay, but should tie together your main points in a concise, convincing way.