Writing Without Limits: Understanding the Lyric Essay

Sean Glatch | February 28, 2023 | 8 Comments

In literary nonfiction, no form is quite as complicated as the lyric essay. Lyrical essays explore the elements of poetry and creative nonfiction in complex and experimental ways, combining the subject matter of autobiography with poetry’s figurative devices and musicality of language.

For both poets and creative nonfiction writers, lyric essays are a gold standard of experimentation and language, but conquering the form takes lots of practice. What is a lyric essay, and how do you write one? Let’s break down this challenging CNF form, with lyric essay examples, before examining how you might approach it yourself.

Want to explore the lyric essay further? See our lyric essay writing course with instructor Gretchen Clark.

What is a lyric essay?

The lyric essay combines the autobiographical information of a personal essay with the figurative language, forms, and experimentations of poetry. In the lyric essay, the rules of both poetry and prose become suggestions, because the form of the essay is constantly changing, adapting to the needs, ideas, and consciousness of the writer.

Lyric essay definition: The lyric essay combines autobiographical writing with the figurative language, forms, and experimentations of poetry.

Lyric essays are typically written in a poetic prose style . (We’ll expand on the difference between prose poetry and lyric essay shortly.) Lyric essays employ many of the poetic devices that poets use, including devices of repetition and rhetorical devices in literature.

That said, there are few conventions for the lyric essay, other than to experiment, experiment, experiment. While the form itself is an essay, there’s no reason you can’t break the bounds of expression.

One tactic, for example, is to incorporate poetry into the essay itself. You might start your essay with a normal paragraph, then describe something specific through a sonnet or villanelle , then express a different idea through a POV shift, a list, or some other form. Lyric essays can also borrow from the braided essay, the hermit crab, and other forms of creative nonfiction .

In truth, there’s very little that unifies all lyric essays, because they’re so wildly experimental. They’re also a bit tricky to define—the line between a lyric essay and the prose poem, in particular, is very hazy.

Rather than apply a one-size-fits-all definition for the lyric essay, which doesn’t exist, let’s pay close attention to how lyric essayists approach the open-ended form.

There are few conventions for the lyric essay, other than to experiment, experiment, experiment

Personal essay vs. lyric essay: An example of each

At its simplest, the lyric essay’s prose style is different from that of the personal essay, or other forms of creative nonfiction.

Personal essay example

Here are the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

“We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.”

The prose in this personal essay excerpt is descriptive, linear, and easy to understand. Fennelly gives us the information we need to make sense of her world, as well as the foreshadow of what’s to come in her essay.

Lyric essay example

Now, take this excerpt from a lyric essay, “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

“The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.”

The prose in Knight’s lyric essay cannot be read the same way as a personal essay might be. Here, Knight’s prose is a sort of experience—a way of exploring the dream through language as shifting and ethereal as dreams themselves. Where the personal essay transcribes experiences, the lyric essay creates them.

Where the personal essay transcribes experiences, the lyric essay creates them.

For more examples of the craft, The Seneca Review and Eastern Iowa Review both have a growing archive of lyric essays submitted to their journals. In essence, there is no form to a lyric essay—rather, form and language are experimented with interchangeably, guided only by the narrative you seek to write.

Lyric Essay Vs Prose Poem

Lyric essays are commonly confused with prose poetry . In truth, there is no clear line separating the two, and plenty of essays, including some of the lyric essay examples in this article, can also be called prose poems.

Well, what’s the difference? A prose poem, broadly defined, is a poem written in paragraphs. Unlike a traditional poem, the prose poem does not make use of line breaks: the line breaks simply occur at the end of the page. However, all other tactics of poetry are in the prose poet’s toolkit, and you can even play with poetry forms in the prose poem, such as writing the prose sonnet .

Lyric essays also blend the techniques of prose and poetry. Here are some general differences between the two:

- Lyric essays tend to be longer. A prose poem is rarely more than a page. Some lyric essays are longer than 20 pages.

- Lyric essays tend to be more experimental. One paragraph might be in prose, the next, poetry. The lyric essay might play more with forms like lists, dreams, public signs, or other types of media and text.

- Prose poems are often more stream-of-conscious. The prose poet often charts the flow of their consciousness on the page. Lyric essayists can do this, too, but there’s often a broader narrative organizing the piece, even if it’s not explicitly stated or recognizable.

The two share many similarities, too, including:

- An emphasis on language, musicality, and ambiguity.

- Rejection of “objective meaning” and the desire to set forth arguments.

- An unobstructed flow of ideas.

- Suggestiveness in thoughts and language, rather than concrete, explicit expressions.

- Surprising or unexpected juxtapositions .

- Ingenuity and play with language and form.

In short, there’s no clear dividing line between the two. Often, the label of whether a piece is a lyric essay or a prose poem is up to the writer.

Lyric Essay Examples

The following lyric essay examples are contemporary and have been previously published online. Pay attention to how the lyric essayists interweave the essay form with a poet’s attention to language, mystery, and musicality.

“Lodge: A Lyric Essay” by Emilia Phillips

Retrieved here, from Blackbird .

This lush, evocative lyric essay traverses the American landscape. The speaker reacts to this landscape finding poetry in the rundown, and seeing her own story—family trauma, religion, and the random forces that shape her childhood. Pay attention to how the essay defies conventional standards of self-expression. In between narrative paragraphs are lists, allusions, memories, and the many twists and turns that seem to accompany the narrator on their journey through Americana.

“Spiral” by Nicole Callihan

Retrieved here, from Birdcoat Quarterly .

Notice how this gorgeous essay evolves down the spine of its central theme: the sleepless swallows. The narrator records her thoughts about the passage of time, her breast examination, her family and childhood, and the other thoughts that arise in her mind as she compares them, again and again, to the mysterious swallows who fly without sleep. This piece demonstrates how lyric essays can encompass a wide array of ideas and threads, creating a kaleidoscope of language for the reader to peer into, come away with something, peer into again, and always see something different.

“Star Stuff” by Jessica Franken

Retrieved here, from Seneca Review .

This short, imagery -driven lyric essay evokes wonder at our seeming smallness, our seeming vastness. The narrator juxtaposes different ideas for what the body can become, playing with all our senses and creating odd, surprising connections. Read this short piece a few times. Ask yourself, why are certain items linked together in the same paragraph? What is the train of thought occurring in each new sentence, each new paragraph? How does the final paragraph wrap up the lyric essay, while also leaving it open ended? There’s much to interpret in this piece, so engage with it slowly, read it over several times.

5 approaches to writing the lyric essay

This form of creative writing is tough for writers because there’s no proper formula for writing it. However, if you have a passion for imaginative forms and want to rise to the challenge, here are several different ways to write your essay.

1. Start with your narrative

Writing the lyrical essay is a lot like writing creative nonfiction: it starts with getting words on the page. Start with a simple outline of the story you’re looking to write. Focus on the main plot points and what you want to explore, then highlight the ideas or events that will be most difficult for you to write about. Often, the lyrical form offers the writer a new way to talk about something difficult. Where words fail, form is key. Combining difficult ideas and musicality allows you to find the right words when conventional language hasn’t worked.

Emilia Phillips’ lyric essay “ Lodge ” does exactly this, letting the story’s form emphasize its language and the narrative Phillips writes about dreams, traveling, and childhood emotions.

2. Identify moments of metaphor and figurative language

The lyric essay is liberated from form, rather than constrained by it. In a normal essay, you wouldn’t want your piece overrun by figurative language, but here, boundless metaphors are encouraged—so long as they aid your message. For some essayists, it might help to start by reimagining your story as an extended metaphor.

A great example of this is Zadie Smith’s essay “ The Lazy River ,” which uses the lazy river as an extended metaphor to criticize a certain “go with the flow” mindset.

Use extended metaphors as a base for the essay, then return to it during moments of transition or key insight. Writing this way might help ground your writing process while giving you new opportunities to play with form.

3. Investigate and braid different threads

Just like the braided essay , lyric essays can certainly braid different story lines together. If anything, the freedom to play with form makes braiding much easier and more exciting to investigate. How can you use poetic forms to braid different ideas together? Can you braid an extended metaphor with the main story? Can you separate the threads into a contrapuntal, then reunite them in prose?

A simple example of threading in lyric essay is Jane Harrington’s “ Ossein Pith .” Harrington intertwines the “you” and “I” of the story, letting each character meet only when the story explores moments of “hunger.”

Whichever threads you choose to write, use the freedom of the lyric essay to your advantage in exploring the story you’re trying to set down.

4. Revise an existing piece into a lyric essay

Some CNF writers might find it easier to write their essay, then go back and revise with the elements of poetic form and figurative language. If you choose to take this route, identify the parts of your draft that don’t seem to be working, then consider changing the form into something other than prose.

For example, you might write a story, then realize it would greatly benefit the prose if it was written using the poetic device of anaphora (a repetition device using a word or phrase at the beginning of a line or paragraph). Chen Li’s lyric essay “ Baudelaire Street ” does a great job of this, using the anaphora “I would ride past” to explore childhood memory.

When words don’t work, let the lyrical form intervene.

5. Write stream-of-conscious

Stream-of-consciousness is a writing technique in which the writer charts, word-for-word, the exact order of their unfiltered thoughts on the page.

If it isn’t obvious, this is easier said than done. We naturally think faster than we write, and we also have a tendency to filter our thoughts as we think them, to the point where many thoughts go unconsciously unnoticed. Unlearning this takes a lot of practice and skill.

Nonetheless, you might notice in the lyric essay examples we shared how the essayists followed different associations with their words, one thought flowing naturally into the next, circling around a subject rather than explicitly defining it. The stream-of-conscious technique is perfect for this kind of writing, then, because it earnestly excavates the mind, creating a kind of Rorschach test that the reader can look into, interpret, see for themselves.

This technique requires a lot of mastery, but if you’re keen on capturing your own consciousness, you may find that the lyric essay form is the perfect container to hold it in.

Closing thoughts on the lyric essay form

Creative nonfiction writers have an overt desire to engage their readers with insightful stories. When language fails, the lyrical essay comes to the rescue. Although this is a challenging form to master, practicing different forms of storytelling could pave new avenues for your next nonfiction piece. Try using one of these different ways to practice the lyric craft, and get writing your next CNF story!

[…] Sean “Writing Your Truth: Understanding the Lyric Essay.” writers.com. https://writers.com/understanding-the-lyric-essay published 19 May, 2020/ accessed 13 Oct, […]

[…] https://writers.com/understanding-the-lyric-essay […]

I agree with every factor that you have pointed out. Thank you for sharing your beautiful thoughts on this. A personal essay is writing that shares an interesting, thought-provoking, sometimes entertaining, and humorous piece that is often drawn from the writer’s personal experience and at times drawn from the current affairs of the world.

[…] been wanting to learn more about lyric essay, and this seems a natural transition from […]

thanks for sharing

Thanks so much for this. Here is an updated link to my essay Spiral: https://www.birdcoatquarterly.com/post/nicole-callihan

I’m interested in learning about essays to write my memoir, so I shall be back.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A Guide to Lyric Essay Writing: 4 Evocative Essays and Prompts to Learn From

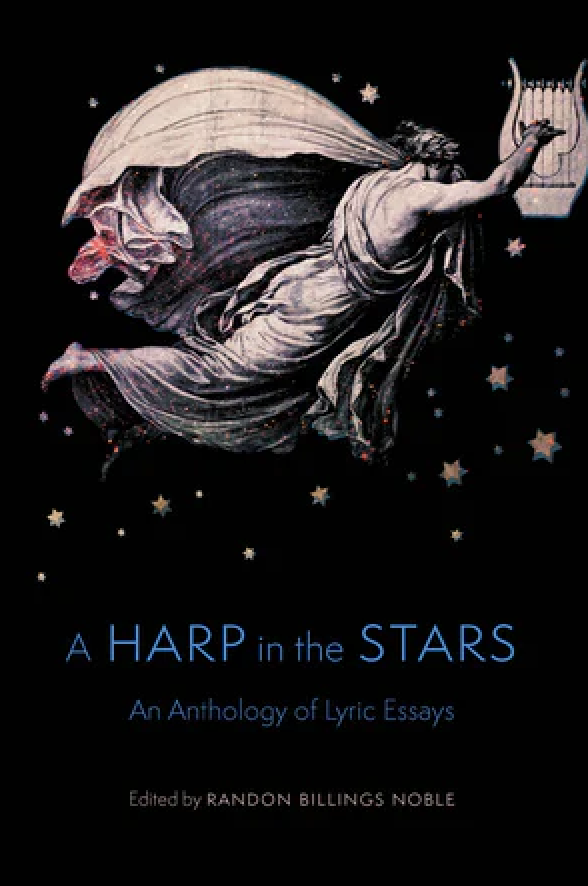

Poets can learn a lot from blurring genres. Whether getting inspiration from fiction proves effective in building characters or song-writing provides a musical tone, poetry intersects with a broader literary landscape. This shines through especially in lyric essays, a form that has inspired articles from the Poetry Foundation and Purdue Writing Lab , as well as become the concept for a 2015 anthology titled We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay.

Put simply, the lyric essay is a hybrid, creative nonfiction form that combines the rich figurative language of poetry with the longer-form analysis and narrative of essay or memoir. Oftentimes, it emerges as a way to explore a big-picture idea with both imagery and rigor. These four examples provide an introduction to the writing style, as well as spotlight tips for creating your own.

1. Draft a “braided essay,” like Michelle Zauner in this excerpt from Crying in H Mart .

Before Crying in H Mart became a bestselling memoir, Michelle Zauner—a writer and frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast—published an essay of the same name in The New Yorker . It opens with the fascinating and emotional sentence, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” This first line not only immediately propels the reader into Zauner’s grief, but it also reveals an example of the popular “braided essay” technique, which weaves together two distinct but somehow related experiences.

Throughout the work, Zauner establishes a parallel between her and her mother’s relationship and traditional Korean food. “You’ll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom’s soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup,” Zauner writes, illuminating the deeply personal and mystifying experience of grieving through direct, sensory imagery.

2. Experiment with nonfiction forms , like Hadara Bar-Nadav in “ Selections from Babyland . ”

Lyric essays blend poetic qualities and nonfiction qualities. Hadara Bar-Nadav illustrates this experimental nature in Selections from Babyland , a multi-part lyric essay that delves into experiences with infertility. Though Bar-Nadav’s writing throughout this piece showcases rhythmic anaphora—a definite poetic skill—it also plays with nonfiction forms not typically seen in poetry, including bullet points and a multiple-choice list.

For example, when recounting unsolicited advice from others, Bar-Nadav presents their dialogue in the following way:

I heard about this great _____________.

a. acupuncturist

b. chiropractor

d. shamanic healer

e. orthodontist ( can straighter teeth really make me pregnant ?)

This unexpected visual approach feels reminiscent of an article or quiz—both popular nonfiction forms—and adds dimension and white space to the lyric essay.

3. Travel through time , like Nina Boutsikaris in “ Some Sort of Union .”

Nina Boutsikaris is the author of I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych , and her work has also appeared in an anthology of the best flash nonfiction. Her essay “Some Sort of Union,” published in Hippocampus Magazine , was a finalist in the magazine’s Best Creative Nonfiction contest.

Since lyric essays are typically longer and more free verse than poems, they can be a way to address a larger idea or broader time period. Boutsikaris does this in “Some Sort of Union,” where the speaker drifts from an interaction with a romantic interest to her childhood.

“They were neighbors, the girl and the air force paramedic. She could have seen his front door from her high-rise window if her window faced west rather than east,” Boutsikaris describes. “When she first met him two weeks ago, she’d been wearing all white, buying a wedge of cheap brie at the corner market.”

In the very next paragraph, Boutskiras shifts this perspective and timeline, writing, “The girl’s mother had been angry with her when she was a child. She had needed something from the girl that the girl did not know how to give. Not the way her mother hoped she would.”

As this example reveals, examining different perspectives and timelines within a lyric essay can flesh out a broader understanding of who a character is.

4. Bring in research, history, and data, like Roxane Gay in “ What Fullness Is .”

Like any other form of writing, lyric essays benefit from in-depth research. And while journalistic or scientific details can sometimes throw off the concise ecosystem and syntax of a poem, the lyric essay has room for this sprawling information.

In “What Fullness Is,” award-winning writer Roxane Gay contextualizes her own ideas and experiences with weight loss surgery through the history and culture surrounding the procedure.

“The first weight-loss surgery was performed during the 10th century, on D. Sancho, the king of León, Spain,” Gay details. “He was so fat that he lost his throne, so he was taken to Córdoba, where a doctor sewed his lips shut. Only able to drink through a straw, the former king lost enough weight after a time to return home and reclaim his kingdom.”

“The notion that thinness—and the attempt to force the fat body toward a state of culturally mandated discipline—begets great rewards is centuries old.”

Researching and knowing this history empowers Gay to make a strong central point in her essay.

Bonus prompt: Choose one of the techniques above to emulate in your own take on the lyric essay. Happy writing!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

8 Tried and True Ways to Get Over Writer’s Block

Forget Merit: Write Poems to Express Yourself

6 Types of Poetry to Read on National Read a Book Day

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Lyric Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Because the lyric essay is a new, hybrid form that combines poetry with essay, this form should be taught only at the intermediate to advanced levels. Even professional essayists aren’t certain about what constitutes a lyric essay, and lyric essays disagree about what makes up the form. For example, some of the “lyric essays” in magazines like The Seneca Review have been selected for the Best American Poetry series, even though the “poems” were initially published as lyric essays.

A good way to teach the lyric essay is in conjunction with poetry (see the Purdue OWL's resource on teaching Poetry in Writing Courses ). After students learn the basics of poetry, they may be prepared to learn the lyric essay. Lyric essays are generally shorter than other essay forms, and focus more on language itself, rather than storyline. Contemporary author Sherman Alexie has written lyric essays, and to provide an example of this form, we provide an excerpt from his Captivity :

"He (my captor) gave me a biscuit, which I put in my

pocket, and not daring to eat it, buried it under a log, fear-

ing he had put something in it to make me love him.

FROM THE NARRATIVE OF MRS. MARY ROWLANDSON,

WHO WAS TAKEN CAPTIVE WHEN THE WAMPANOAG

DESTROYED LANCASTER, MASSACHUSETS, IN 1676"

"I remember your name, Mary Rowlandson. I think of you now, how necessary you have become. Can you hear me, telling this story within uneasy boundaries, changing you into a woman leaning against a wall beneath a HANDICAPPED PARKING ONLY sign, arrow pointing down directly at you? Nothing changes, neither of us knows exactly where to stand and measure the beginning of our lives. Was it 1676 or 1976 or 1776 or yesterday when the Indian held you tight in his dark arms and promised you nothing but the sound of his voice?"

Alexie provides no straightforward narrative here, as in a personal essay; in fact, each numbered section is only loosely related to the others. Alexie doesn’t look into his past, as memoirists do. Rather, his lyric essay is a response to a quote he found, and which he uses as an epigraph to his essay.

Though the narrator’s voice seems to be speaking from the present, and addressing a woman who lived centuries ago, we can’t be certain that the narrator’s voice is Alexie’s voice. Is Alexie creating a narrator or persona to ask these questions? The concept and the way it’s delivered is similar to poetry. Poets often use epigraphs to write poems. The difference is that Alexie uses prose language to explore what this epigraph means to him.

An Introduction to the Lyric Essay

An introduction to the lyric essay, how it differs from other nonfiction, and some excellent examples to get you started.

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Essays come in a bewildering variety of shapes and forms: they can be the five paragraph essays you wrote in school — maybe for or against gun control or on symbolism in The Great Gatsby . Essays can be personal narratives or argumentative pieces that appear on blogs or as newspaper editorials. They can be funny takes on modern life or works of literary criticism. They can even be book-length instead of short. Essays can be so many things!

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “lyric essay” and are wondering what that means. I’m here to help.

What is the Lyric Essay?

A quick definition of the term “lyric essay” is that it’s a hybrid genre that combines essay and poetry. Lyric essays are prose, but written in a manner that might remind you of reading a poem.

Before we go any further, let me step back with some more definitions. If you want to know the difference between poetry and prose, it’s simply that in poetry the line breaks matter, and in prose they don’t. That’s it! So the lyric essay is prose, meaning where the line breaks fall doesn’t matter, but it has other similarities to what you find in poems.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Lyric essays have what we call “poetic” prose. This kind of prose draws attention to its own use of language. Lyric essays set out to create certain effects with words, often, although not necessarily, aiming to create beauty. They are often condensed in the way poetry is, communicating depth and complexity in few words. Chances are, you will take your time reading them, to fully absorb what they are trying to say. They may be more suggestive than argumentative and communicate multiple meanings, maybe even contradictory ones.

Lyric essays often have lots of white space on their pages, as poems do. Sometimes they use the space of the page in creative ways, arranging chunks of text differently than regular paragraphs, or using only part of the page, for example. They sometimes include photos, drawings, documents, or other images to add to (or have some other relationship to) the meaning of the words.

Lyric essays can be about any subject. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be. They can be philosophical or about nature or history or culture, or any combination of these things. What distinguishes them from other essays, which can also be about any subject, is their heightened attention to language. Also, they tend to deemphasize argument and carefully-researched explanations of the kind you find in expository essays . Lyric essays can argue and use research, but they are more likely to explore and suggest than explain and defend.

Now, you may be familiar with the term “ prose poem .” Even if you’re not, the term “prose poem” might sound exactly like what I’m describing here: a mix of poetry and prose. Prose poems are poetic pieces of writing without line breaks. So what is the difference between the lyric essay and the prose poem?

Honestly, I’m not sure. You could call some pieces of writing either term and both would be accurate. My sense, though, is that if you put prose and poetry on a continuum, with prose on one end and poetry on the other, and with prose poetry and the lyric essay somewhere in the middle, the prose poem would be closer to the poetry side and the lyric essay closer to the prose side.

Some pieces of writing just defy categorization, however. In the end, I think it’s best to call a work what the author wants it to be called, if it’s possible to determine what that is. If not, take your best guess.

Four Examples of the Lyric Essay

Below are some examples of my favorite lyric essays. The best way to learn about a genre is to read in it, after all, so consider giving one of these books a try!

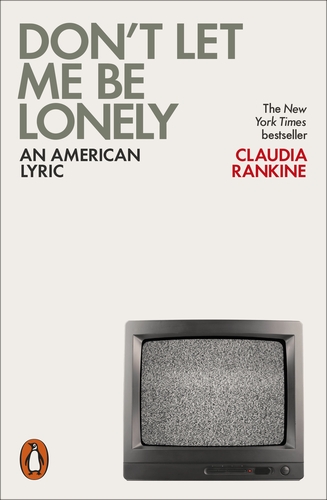

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen counts as a lyric essay, but I want to highlight her lesser-known 2004 work. In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence from the perspective of post-9/11 America. It combines words and images, particularly television images, to ponder our relationship to media and culture. Rankine writes in short sections, surrounded by lots of white space, that are personal, meditative, beautiful, and achingly sad.

Calamities by Renee Gladman

Calamities is a collection of lyric essays exploring language, imagination, and the writing life. All of the pieces, up until the last 14, open with “I began the day…” and then describe what she is thinking and experiencing as a writer, teacher, thinker, and person in the world. Many of the essays are straightforward, while some become dreamlike and poetic. The last 14 essays are the “calamities” of the title. Together, the essays capture the artistic mind at work, processing experience and slowly turning it into writing.

The Self Unstable by Elisa Gabbert

The Self Unstable is a collection of short essays — or are they prose poems? — each about the length of a paragraph, one per page. Gabbert’s sentences read like aphorisms. They are short and declarative, and part of the fun of the book is thinking about how the ideas fit together. The essays are divided into sections with titles such as “The Self is Unstable: Humans & Other Animals” and “Enjoyment of Adversity: Love & Sex.” The book is sharp, surprising, and delightful.

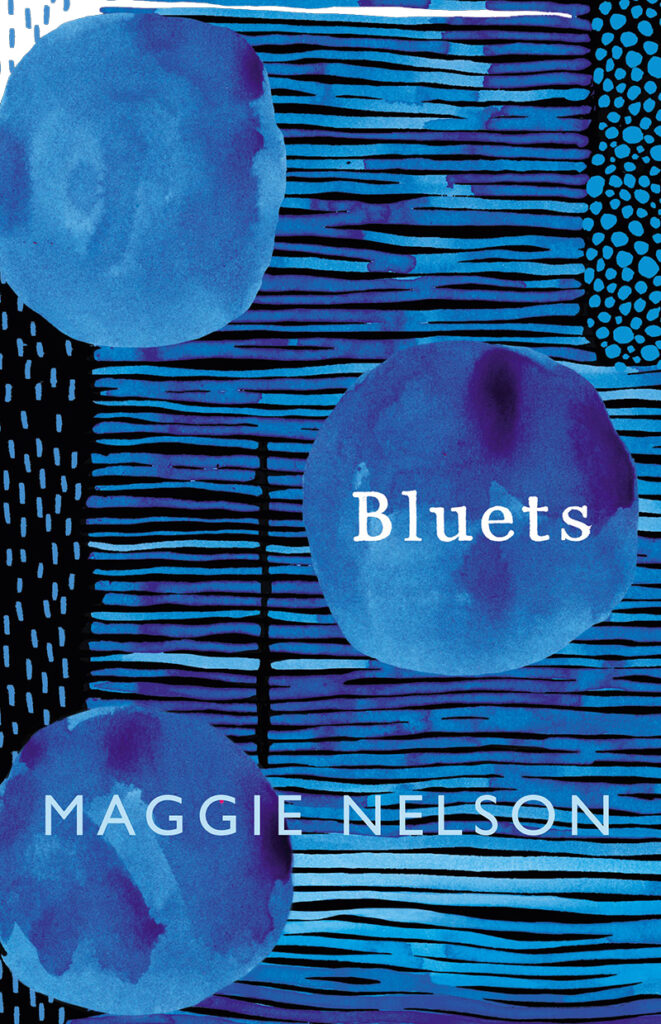

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. Maggie Nelson’s subjects are many and include the color blue, in which she finds so much interest and meaning it will take your breath away. It’s also about suffering: she writes about a friend who became a quadriplegic after an accident, and she tells about her heartbreak after a difficult break-up. Bluets is meditative and philosophical, vulnerable and personal. It’s gorgeous, a book lovers of The Argonauts shouldn’t miss.

It’s probably no surprise that all of these books are published by small presses. Lyric essays are weird and genre-defying enough that the big publishers generally avoid them. This is just one more reason, among many, to read small presses!

If you’re looking for more essay recommendations, check out our list of 100 must-read essay collections and these 25 great essays you can read online for free .

You Might Also Like

Novlr is now writer-owned! Join us and shape the future of creative writing.

19 January 2024

An Insider’s Guide to Writing the Perfect Lyrical Essay

As the name might suggest, the lyrical essay or the lyric essay is a literary hybrid, combining features of poetry, essay, and often memoir . The lyrical essay is a form of creative non-fiction that has become more popular over the last decade.

There has been much written about what lyrical essays are and aren’t, and many writers have strong opinions about them, either declaring them expressive and playful, or self-indulgent and nonsensical.

Today, you’ll learn what a lyrical essay is, what literary elements and techniques they usually employ, and how they depart from other forms of writing and why writers might choose to write them. You’ll also find recommendations for some top lyrical essays to start familiarising yourself with.

What is the lyrical essay?

Lyrical essays combine the rich, figurative language and musicality of poetry with the long-form focus of the essay. A lyrical essay is like the poem in its shapeliness and rhythmic style, but it also borrows from elements of the essay, using narrative to explore a particular topic in an extended way.

What makes this form of writing so distinctive is that it draws attention to its own use of language. Like poems, lyrical essays create certain effects with the words they choose, and are condensed in the way poetry is, attempting to communicate complexity and depth in as few words as possible.

What makes a good lyrical essay?

As with essays and poems, lyrical essays can be about any subject. Many lyrical essays tend to engage with topics such as philosophy, art, culture, history , beauty, politics, and nature, or a mixture of these subjects. They typically focus on a series of images of a person, place, or object, with the aim of evoking emotion in the reader by using very sensory details. A lyrical essay is written in an intimate voice, usually in the first person with a conversational and informal tone. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be.

While lyrical essays take on the longer-form shape of essays, they are not organized as a narrative, with one event unfolding in a chronological or even logical order. Instead, the writer usually creates a series of fragmented images using figurative language and poetic techniques in a looser, more playful way. Some lyrical essayists draw on research and fact to inform their writing, but lyrical essays are usually more suggestive and explorative than they are definitive or conclusive.

Creative techniques

Like poems, lyric essays often use white space creatively. Text can be displayed in chunks, bullet points, and on only parts of the page, rather than conforming to the typical paragraph structure you’d find in normal prose. Lyric essays might include asterisks, double spaces, and numbers to frame parts of the writing in new ways. They sometimes include drawings, documents, photos, or other images that add meaning to the words in some way.

As with poetry, reading lyrical essays can be an intense experience. Instead of being immersed in narrative and plot, the reader is immersed in structure and form, always being reminded of how the language is shifting. Lyric essays are playful, and as such, they can surprise and delight you with their ingenuity.

Lyrical essays usually contain some of the following techniques and features:

- Poetic language – alliteration, assonance, and internal rhyme

- Figurative language – metaphors and similes

- Intimate voice and tone – first person in a conversational and friendly style

- Imagery – sensory images of people, places, things, objects, and ideas

- Variety – an array of sentence styles and patterns

- Questions – posed for the reader to answer

- Juxtaposition and contradiction

- Rhythm or rhythmic prose

- Creative presentation of text – text displayed in a fragmented way, with white space, asterisks, subtitles etc to separate or highlight sections of the essay

- Inconclusive ending – often ends without answering the questions posed in the essay

Literary reception

One of the most popular criticisms of the lyrical essay is that they are self-indulgent. Some writers and readers feel strongly that lyrical essays are simply disjointed thoughts that are strung together without any order and that they go nowhere. Some people criticise them as a stream of consciousness, but that is also what others like about them. Those who defend lyrical essays think that they are one of the most exciting and unique forms of writing.

Deborah Tall, an American writer, poet and teacher, explains that the fragmented nature of lyrical essays is what makes them so interesting. She said that lyrical essays take shape “mosaically” and that their power and importance are “visible only when one stands back and sees it whole.” She goes on to say that the story a lyrical essay tells “may be no more than metaphors. Or, storyless, it may spiral in on itself, circling the core of a single image or idea, without climax, without a paraphrasable theme”. But she celebrates this very fact, as it is this unique construction that elucidates meaning.

Lyrical essays allow writers the freedom to push poetic prose until an important and emotional message pops from the page.

Recommended Lyrical Essays

What’s missing here a fragmentary, lyric essay about fragmentary, lyric essays by julia marie wade (from a harp in the stars: an anthology of lyric essays ).

What’s Missing Here? is an extraordinary piece of meta-writing – a lyrical essay about lyrical essays – from author and Professor of creative fiction, Julia Marie Wade. It is an absolute joy to read, at once challenging and fun, and also highly informative as it uses the techniques of lyrical essays to explain what they are and what they can do.

It’s one of the best examples of a clever and engaging lyrical essay, and it’s from a fantastic collection that is worth delving into if you’re interested in learning more about this unique literary hybrid.

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely by Claudia Rankine

In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Claudia Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence in post-9/11 America.

Rankine writes in short sections surrounded by white space and uses images of the television to explore our relationship to the media. It’s a powerful look at culture that is meditative and achingly sad from one of America’s best poets.

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Maggie Nelson is a genre-busting writer who defies classification. Bluets winds its way through depression, divinity, alcohol, and desire, visiting famous blue figures including Joni Mitchell, Billie Holiday, Leonard Cohen, and Andy Warhol along the way. While its narrator sets out to muse about her lifelong obsession with the colour blue, she ends up facing the painful end of an affair and the grievous injury of a friend.

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. It’s a vulnerable, personal, and philosophical lyrical essay, full of innovation and grace.

Note: All purchase links in this post are affiliate links through BookShop.org, and Novlr may earn a small commission – every purchase supports independent bookstores.

10 of the Best Examples of the Lyric Poem

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

A lyric poem is a (usually short) poem detailing the thoughts or feelings of the poem’s speaker. Originally, lyric poems, as the name suggests, were sung and accompanied by the lyre , a stringed instrument not unlike a harp. Even today, we often use the term ‘lyricism’ to denote a certain harmony or musicality in poetry. Below, we introduce ten of the greatest short lyric poems written in English from the Middle Ages to the present day.

1. Anonymous, ‘Fowls in the Frith’.

We begin our whistle-stop tour of the lyric poem in the thirteenth century, a whole century before Geoffrey Chaucer, with this intriguing and ambiguous anonymous five-line lyric:

Foulës in the frith, The fishës in the flod, And I mon waxë wod; Much sorwe I walkë with For beste of bon and blod.

A ‘frith’ is a wood or forest; the poem, written in Middle English, features a speaker who, he tells us, ‘mon waxë wod’ (i.e. must go mad) because of the sorrow he walks with.

Because the last line is ambiguous (‘the best of bone and blood’ could refer to a woman or to Christ), the poem can be read either as a love lyric or as a religious lyric.

We have gathered together more classic medieval lyrics here .

2. Sir Thomas Wyatt, ‘ Whoso List to Hunt ’.

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind, But as for me, hélas , I may no more. The vain travail hath wearied me so sore, I am of them that farthest cometh behind …

One of the most popular and enduring lyric forms has been the sonnet: 14 lines (usually), in which the poet expresses their thoughts and feelings about love, death, or some other theme. In the English or ‘Shakespearean’ sonnet the poet usually brings their ‘argument’ to a conclusion in the final rhyming couplet.

Here, however, Sir Thomas Wyatt offers an Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, but he introduces the distinctive ‘English’ conclusion: that rhyming couplet. In a loose translation of a fourteenth-century sonnet by Petrarch, Wyatt (1503-42) describes leaving off his ‘hunt’ for a ‘hind’ – in a lyric poem that was possibly a coded reference to his own relationship with Anne Boleyn.

3. Robert Herrick, ‘ Upon Julia’s Clothes ’.

Whenas in silks my Julia goes, Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows The liquefaction of her clothes …

This very short lyric poem, by one of England’s foremost Cavalier poets of the seventeenth century, is deceptively simple. It seems to be simply a description of the woman’s silken clothing, and its pleasure-inducing effects on our poet.

But the poem seems to hint at far more than this, as we’ve explored in the analysis that follows the poem (in the link provided above). It might be described as one of the finest erotic lyric poems of the early modern period.

4. Emily Dickinson, ‘ The Heart Asks Pleasure First ’.

The Heart asks Pleasure – first – And then – Excuse from Pain – And then – those little Anodynes That deaden suffering …

So begins this short lyric poem from the prolific nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-86).

The poem examines what one’s ‘heart’ most desires: a common theme in lyric poetry. The heart desires pleasure, but failing that, will settle for being excused from pain, and to live a life without suffering pain.

5. Charlotte Mew, ‘ A Quoi bon Dire ’.

Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) was a popular poet in her lifetime, and was admired by fellow poets Ezra Pound and Thomas Hardy. ‘A Quoi Bon Dire’ was published in Charlotte Mew’s 1916 volume The Farmer’s Bride . The French title of this poem translates as ‘what good is there to say’. And what good is there to say about this short poem? We think it’s a beautiful example of early twentieth-century lyricism:

Seventeen years ago you said Something that sounded like Good-bye; And everybody thinks that you are dead …

Follow the link above to read this tender lyric poem in full.

6. W. B. Yeats, ‘ He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven ’.

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths, Enwrought with golden and silver light, The blue and the dim and the dark cloths Of night and light and the half light …

The gist of this poem, one of Yeats’s most popular short lyric poems, is straightforward: if I were a rich man, I’d give you the world and all its treasures. If I were a god, I could take the heavenly sky and make a blanket out of it for you.

But I’m only a poor man, and obviously the idea of making the sky into a blanket is silly and out of the question, so all I have of any worth are my dreams. And dreams are delicate and vulnerable – hence ‘Tread softly’. But Yeats, using his distinctive lyricism, puts it better than this paraphrase can convey.

7. T. E. Hulme, ‘ Autumn ’.

A touch of cold in the Autumn night – I walked abroad, And saw the ruddy moon lean over a hedge Like a red-faced farmer …

This short poem by arguably the first modern poet in English was written in 1908; it’s a short imagist lyric in free verse about a brief encounter with the autumn (i.e. harvest) moon. This poem earns its place on this list of great lyric poems because of the originality of the image at its centre: that of comparing the ‘ruddy moon’ to a … well, we’ll let you discover that for yourself.

8. H. D., ‘ The Pool ’.

After Hulme’s free verse lyrics came the imagists – a group of modernist poets who placed the poetic image at the centre of their poems, often jettisoning everything else. H. D., born Hilda Doolittle in the US in 1886, was described as the ‘perfect imagist’, and ‘The Pool’ shows why.

In this example of a short free-verse lyric poem, H. D. offers what her fellow imagist F. S. Flint described as an ‘accurate mystery’: clear-cut crystalline imagery whose meaning or significance nevertheless remain shrouded in ambiguity and questions. Here, H. D. even begins and ends her poem with a question. Who, or what, is the addressee of this miniature masterpiece?

9. W. H. Auden, ‘ If I Could Tell You ’.

Lyric poems weren’t all written in free verse once we arrived in the twentieth century. Indeed, many poets of the 1930s, such as the clear leader of the pack, W. H. Auden (1907-73), wrote in more traditional forms, such as the sonnet or, indeed, the villanelle: a form where the first and third lines of the poem are repeated at the ends of the subsequent stanzas.

In this tender lyric poem, Auden explores the limits of the poet’s ability to communicate to the world – or perhaps, to a loved one?

We have analysed this poem here .

10. Carol Ann Duffy, ‘ Syntax ’.

Duffy’s work shows a thorough awareness of poetic form, even though she often plays around with established forms and rhyme schemes to create something new.

First published in 2005, ‘Syntax’ is a contemporary lyric poem about trying to find new and original ways to say ‘I love you’. Duffy’s poem seeks out new ways to express the sincerity of love, explored, fittingly enough, in a new sort of ‘sonnet’ (14 lines and ending in a sort-of couplet, though written in irregular free verse). A love poem for the texting generation?

We introduce more Carol Ann Duffy poems here .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

2 thoughts on “10 of the Best Examples of the Lyric Poem”

- Pingback: Monday Post – 16th December, 2019 #Brainfluffbookblog #SundayPost | Brainfluff

- Pingback: 10 Interesting Posts You May Have Missed in December 2019 – Pages Unbound | Book Reviews & Discussions

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Hobart and William Smith Colleges

The lyric essay.

- Seneca Review

- Submissions

- Back Issues

- Lyric Essay

- Beyond Category

- Subscriptions

- Seneca Review Books

- HWS Colleges Press

- Offices/Administration

With its Fall 1997 issue, Seneca Review began to publish what we've chosen to call the lyric essay. The recent burgeoning of creative nonfiction and the personal essay has yielded a fascinating sub-genre that straddles the essay and the lyric poem. These "poetic essays" or "essayistic poems" give primacy to artfulness over the conveying of information. They forsake narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation.

The lyric essay partakes of the poem in its density and shapeliness, its distillation of ideas and musicality of language. It partakes of the essay in its weight, in its overt desire to engage with facts, melding its allegiance to the actual with its passion for imaginative form.

The lyric essay does not expound. It may merely mention. As Helen Vendler says of the lyric poem, "It depends on gaps. . . . It is suggestive rather than exhaustive." It might move by association, leaping from one path of thought to another by way of imagery or connotation, advancing by juxtaposition or sidewinding poetic logic. Generally it is short, concise and punchy like a prose poem. But it may meander, making use of other genres when they serve its purpose: recombinant, it samples the techniques of fiction, drama, journalism, song, and film.

Given its genre mingling, the lyric essay often accretes by fragments, taking shape mosaically - its import visible only when one stands back and sees it whole. The stories it tells may be no more than metaphors. Or, storyless, it may spiral in on itself, circling the core of a single image or idea, without climax, without a paraphrasable theme. The lyric essay stalks its subject like quarry but is never content to merely explain or confess. It elucidates through the dance of its own delving.

Loyal to that original sense of essay as a test or a quest, an attempt at making sense, the lyric essay sets off on an uncharted course through interlocking webs of idea, circumstance, and language - a pursuit with no foreknown conclusion, an arrival that might still leave the writer questioning. While it is ruminative, it leaves pieces of experience undigested and tacit, inviting the reader's participatory interpretation. Its voice, spoken from a privacy that we overhear and enter, has the intimacy we have come to expect in the personal essay. Yet in the lyric essay the voice is often more reticent, almost coy, aware of the compliment it pays the reader by dint of understatement.

What has pushed the essay so close to poetry? Perhaps we're drawn to the lyric now because it seems less possible (and rewarding) to approach the world through the front door, through the myth of objectivity. The life span of a fact is shrinking; similitude often seems more revealing than verisimilitude. We turn to the artist to reconcoct meaning from the bombardments of experience, to shock, thrill, still the racket, and tether our attention.

We turn to the lyric essay - with its malleability, ingenuity, immediacy, complexity, and use of poetic language - to give us a fresh way to make music of the world. But we must be willing to go out on an artistic limb with these writers, keep our balance on their sometimes vertiginous byways. Anne Carson, in her essay on the lyric, "Why Did I Awake Lonely Among the Sleepers" (Published in Seneca Review Vol. XXVII, no. 2) quotes Paul Celan. What he says of the poem could well be said of the lyric essay:

The poem holds its ground on its own margin.... The poem is lonely. It is lonely and en route. Its author stays with it.

If the reader is willing to walk those margins, there are new worlds to be found.

-- Deborah Tall, Editor and John D'Agata, Associate Editor for Lyric Essays

Course Syllabus

Writing the Lyric Essay: When Poetry & Nonfiction Play

Experiment with form and explore the possibilities of this flexible genre..

Some of the most artful work being done in essay today exists in a liminal space that touches on the poetic. In this course, you will read and write lyric essays (pieces of creative nonfiction that move in ways often associated with poetry) using techniques such as juxtaposition; collage; white space; attention to sound; and loose, associative thinking. You will read lyric essays that experiment with form and genre in a variety of ways (such as the hermit crab essay, the braided essay, multimedia work), as well as hybrid pieces by authors working very much at the intersection of essay and poetry. We will proceed in this course with an attitude of play, openness, and communal exploration into the possibilities of the lyric essay, reaching for our own definitions and methods, even as we study the work of others for models and inspiration. Whether you are an aspiring essayist interested in infusing your work with fresh new possibilities, or a poet who wants to try essay, this course will have room for you to experiment and play.

How it works:

Each week provides:

- discussions of assigned readings and other general writing topics with peers and the instructor

- written lectures and a selection of readings

Some weeks also include:

- the opportunity to submit two essays of 1000 and 2500 words each for instructor and/or peer review

- additional optional writing exercises

- an optional video conference that is open to all students(and which will be available afterward as a recording for those who cannot participate)

Aside from the live conference, there is no need to be online at any particular time of day. To create a better classroom experience for all, you are expected to participate weekly in class discussions to receive instructor feedback.

Week 1: Lyric Models: Space and Collage

In this first week, we’ll consider definitions and models for the lyric essay. You will read contemporary pieces that straddle the line between personal essay and poem, including work by Toi Derricotte, Anne Carson, and Maggie Nelson. In exercises, you will explore collage and the use of white space.

Week 2: Experiments with Form: Braided Essay and Hermit Crab Essay

We will build on our discussion of collage and white space, looking at examples of the braided essay. We’ll also examine the hermit crab essay, in which writers “sneak” personal essays into other forms, such as a job letter, shopping list, or how-to manual. You’ll experiment with your own braided pieces and hermit crab pieces and turn in the first assignment.

Week 3: Lyric Vignette and the Prose Poem

Prose poems will often capture emotional truths using juxtaposition, hyperbole, and absurd or surreal leaps of logic. This week, we’ll investigate how lyrical vignettes can stay true to actual events while employing some of the lyrical, dreamlike, and/or absurd qualities of the prose poem to communicate the wonder and mystery of life.

Week 4: Witnessing the Self: Essays by Poets

Poet Larry Levis has written of the poet as witness, as temporarily emptied of personality but simultaneously connected to a self, a “gazer.” Personal essays by poets retain something of this quality. Examining essays by poets such as Ross Gay, Lucia Perillo, Amy Gerstler, and Elizabeth Bishop, we’ll look at moments of connection and disconnection. Guided exercises will help you find and craft your own such moments.

Week 5: Hybrid Forms and the Documentary Impulse

As we wrap up the course, we will continue investigating the possibilities inherent in straddling and combining genres as we explore multimedia work, as well as work in the “documentary poetics” vein. We will look to writers like Claudia Rankine and Bernadette Mayer, Roz Chast and Maira Kalman for models of what is possible creatively when we observe ourselves as social beings moving through time, collecting text, images, and observations. Students will also turn in a final essay.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Lyric Poetry

Explore the glossary of poetic terms.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Lyric poetry refers to a short poem, often with songlike qualities, that expresses the speaker’s personal emotions and feelings. Historically intended to be sung and accompany musical instrumentation, lyric now describes a broad category of non-narrative poetry, including elegies, odes, and sonnets.

History of Lyric Poetry:

Lyric poetry began as a fixture of ancient Greece, classified against other categories of poetry at the time of classical antiquity: dramas (written in verse) and epic poems. The lyric was far shorter, distinguished also by its focus on the poet’s state of mind and personal themes rather than narrative arc.

Most typically accompanying the lyre, a harp-like instrument from which lyric poetry derives its name, these poems would also be sung to other instruments and other times recited. Classical musician-poets from the Archaic Greek period include Sappho , one of the most widely regarded lyric poets of all time. Her lyric, numbered “ XII ,” begins:

In a dream I spoke with the Cyprus-born,

And said to her,

“Mother of beauty, mother of joy,

Why hast thou given to men

“This thing called love, like the ache of a wound

In beauty's side,

To burn and throb and be quelled for an hour

And never wholly depart?“

Lyric poetry appears in a variety of forms, the most popular of which is arguably the sonnet : traditionally, a fourteen-line poem written in iambic pentameter. Sir Thomas Wyatt and of course William Shakespeare helped popularize the classical form for English audiences. William Wordsworth ’s “ The World Is Too Much With Us ” is a great example of a sonnet adapted, at the time, for the 19th century.

The ode , a formal address to an event, a person, or a thing not present, is another common branch of lyric poetry. There are three typical types of odes: the Pindaric, Horatian, and Irregular. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “ Ode to the West Wind ” is a great example of a Pindaric and one of the most celebrated odes of the English language.

Other famous examples of lyric poems include Edgar Allan Poe ’s “The Raven,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ’s “My Lost Youth,” and Samuel Taylor Coleridge ’s “Ode to Dejection.”

The Academy of American Poets Chancellors Mark Doty, Linda Gregerson, and Jane Hirshfield discusses the history of the lyric poem in this video.

We all know that poetry is not one thing; the spectrum from lyric to narrative in the category of "poem" is vast and encompasses much; so, too, the spectrum of formal to freer verse. The same goes for song, for music itself. So some of the ongoing discussions and debates about whether or not this or that song is also a poem, or this or that songwriter is also a poet intrigue and vex me in equal parts because I haven’t felt the attraction to debating the borders of genre, or, more important, to making some definitive decision about the topic.—Claudia Emerson in “ Lyric Impression, Muscle Memory, Emily, and the Jack of Hearts ”

I blinked, of course. This is the question essential to the lyric poem: how to make the particular universal, or, better said, how to discover the universal in the particular. Every poem is an attempt to answer this question, and when we are confronted with questions of such magnitude and scope, it is often best to defer to something that has—as Rilke says we must—lived those questions to their depths.—Joseph Fasano in “ Supernovae and Dark Stars: Some Notes on Universality in the Lyric Poem ”

Eros is often the fuel of the lyric imagination, which chooses to use words, sentences, musical structures of language to re/member the beloved, to enter that inexhaustible source of—not uniquely "carnal"—knowledge which is another person's body and mind.—“ Eros and the Lyric Imagination: Poems of Love ”

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Lyric Poetry: Expressing Emotion Through Verse

This musical verse conveys powerful feelings.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

- Poetic Forms

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jackie-Craven-ThoughtCo-58eeac613df78cd3fc7a495c.jpg)

- Doctor of Arts, University of Albany, SUNY

- M.S., Literacy Education, University of Albany, SUNY

- B.A., English, Virginia Commonwealth University

A lyric poem is a short verse with musical qualities that conveys powerful feelings. When writing lyrical poetry, a poet may use rhyme, meter, or other literary devices to create a song-like rhythm and word structure.

Unlike narrative poetry , which chronicles events, lyric poetry doesn't have to tell a story. A lyric poem is a private expression of emotion by a single speaker. For example, American poet Emily Dickinson described her inner feelings when she wrote the lyric poem that begins, I felt a Funeral, in my Brain, / And Mourners to and fro .

Key Takeways: Lyric Poetry

- A lyric poem is a private expression of emotion by an individual speaker.

- Lyric poetry has musical qualities and can feature poetic devices like rhyme and meter.

- Some scholars categorize lyric poetry into three subtypes: Lyric of Vision, Lyric of Thought, and Lyric of Emotion. However, this classification is not widely agreed upon.

Origins of Lyric Poetry

Song lyrics often begin as lyric poems. In ancient Greece, lyric poetry was combined with music played on a U-shaped stringed instrument called a lyre. Through words and music, great lyric poets like Sappho (ca. 610–570 B.C.) poured out feelings of love and yearning.

Similar approaches to poetry were developed in other parts of the world. Between the fourth century B.C. and the first century A.D., Hebrew poets composed intimate and lyrical psalms, which were sung in ancient Jewish worship services and compiled in the Hebrew Bible. During the eighth century, Japanese poets expressed their ideas and emotions through haiku and other poetic forms. Writing lyrically about his private life, Taoist writer Li Po (710–762) became one of China's most celebrated poets.

The rise of lyric poetry in the Western world represented a shift from epic narratives about heroes and gods. The personal tone of lyric poetry gave it broad appeal. Poets in Europe drew inspiration from ancient Greece but also borrowed ideas from the Middle East, Egypt, and Asia.

Types of Lyric Poetry

Of the three main categories of poetry—narrative, dramatic, and lyric—lyric is the most common and the most difficult to classify. Narrative poems tell stories. Dramatic poetry is a play written in verse. Lyric poetry, however, encompasses a wide range of forms and approaches.

Nearly any experience or phenomenon can be explored through the emotional and personal mode of lyric writing, from war and patriotism to love and art.

Lyric poetry has no prescribed form. Sonnets , villanelles , rondeaus , and pantoums are all considered lyric poems. So are elegies, odes, and most occasional (or ceremonial) poems. When composed in free verse , lyric poetry achieves musicality through literary devices such as alliteration , assonance , and anaphora .

Each of the following examples illustrates an approach to lyric poetry.

William Wordsworth, "The World Is Too Much With Us"

The English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850) famously said that poetry is "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." In The World Is Too Much with Us , his passion is evident in blunt exclamatory statements such as "a sordid boon!" Wordsworth condemns materialism and alienation from nature, as this section of the poem illustrates.

"The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!"

Although The World Is Too Much with Us feels spontaneous, it was composed with care ("recollected in tranquility"). A Petrarchan sonnet, the complete poem has 14 lines with a prescribed rhyme scheme, metrical pattern, and arrangement of ideas. In this musical form, Wordsworth expressed personal outrage over the effects of the Industrial Revolution .

Christina Rossetti, "A Dirge"

British poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) composed A Dirge in rhyming couplets. The consistent meter and rhyme create the effect of a burial march. The lines grow progressively shorter, reflecting the speaker's sense of loss, as this selection from the poem illustrates.

"Why were you born when the snow was falling?

You should have come to the cuckoo’s calling,

Or when grapes are green in the cluster,

Or, at least, when lithe swallows muster

For their far off flying

From summer dying."

Using deceptively simple language, Rossetti laments an untimely death. The poem is an elegy, but Rossetti doesn't tell us who died. Instead, she speaks figuratively, comparing the span of a human life to the changing seasons.

Elizabeth Alexander, "Praise Song for the Day"

American poet Elizabeth Alexander (1962– ) wrote Praise Song for the Day to read at the 2009 inauguration of America's first Black president, Barack Obama . The poem doesn't rhyme, but it creates a song-like effect through the rhythmic repetition of phrases. By echoing a traditional African form, Alexander paid tribute to African culture in the United States and called for people of all races to live together in peace.

"Say it plain: that many have died for this day.

Sing the names of the dead who brought us here,

who laid the train tracks, raised the bridges,

picked the cotton and the lettuce, built

brick by brick the glittering edifices

they would then keep clean and work inside of.

Praise song for struggle, praise song for the day.

Praise song for every hand-lettered sign,

the figuring-it-out at kitchen tables."

Praise Song for the Day is rooted in two traditions. It's an occasional poem, written and performed for a special occasion, and a praise song, an African form that uses descriptive word pictures to capture the essence of something being praised.

Occasional poetry has played an important role in Western literature since the days of ancient Greece and Rome. Short or long, serious or lighthearted, occasional poems commemorate coronations, weddings, funerals, dedications, anniversaries, and other important events. Similar to odes, occasional poems are often passionate expressions of praise.

Classifying Lyric Poems

Poets are always devising new ways to express feelings and ideas, transforming our understanding of the lyric mode. Is a found poem lyric? What about a concrete poem made from artful arrangements of words on the page? To answer these questions, some scholars utilize three classifications for lyric poetry: Lyric of Vision, Lyric of Thought, and Lyric of Emotion.

Visual poetry like May Swenson's pattern poem, Women , belongs to the Lyric of Vision subtype. Swenson arranged lines and spaces in a zigzag pattern to suggest the image of women rocking and swaying to satisfy the whims of men. Other Lyric of Vision poets have incorporated colors, unusual typography, and 3D shapes .

Didactic poems designed to teach and intellectual poems (such as satire) may not seem especially musical or intimate, but these works can be placed in the Lyric of Thought category. For examples of this subtype, consider the scathing epistles by 18th-century British poet Alexander Pope .

The third subtype, Lyric of Emotion, refers to works we usually associate with lyric poetry as a whole: mystical, sensual, and emotional. However, scholars have long debated these classifications. The term "lyric poem" is often used broadly to describe any poem that is not a narrative or a stage play.

- Burch, Michael R. " The Best Lyric Poetry: Origins and History with a Definition and Examples. " The HyperTexts Journal.

- Gutman, Huck. " The Plight of the Modern Lyric Poet. " Except from a seminar lecture. “Identity, Relevance, Text: Reviewing English Studies.” Calcutta University, 8 Feb. 2001.

- Melani, Lilia. " Reading Lyric Poetry. " Adapted from A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature, Brooklyn College.

- Neziroski, Lirim. "Narrative, Lyric, Drama." Theories of Media, Keyword Glossary. University of Chicago. Winter 2003.

- The Poetry Foundation. "Saphho."

- Titchener, Frances B. " Chapter 5: Greek Lyric Poetry. " Ancient Literature and Language, A Guide to Writing in History and Classics.

- What Is Narrative Poetry? Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Blank Verse

- The Sonnet: A Poem in 14 Lines

- What Is Ekphrastic Poetry?

- Introduction to Found Poetry

- What Is Enjambment? Definition and Examples

- Understanding the Definition of an Acrostic Poem

- What Is an Iamb in Poetry?

- What Kind of Poem Is a Pantoum?

- The Beat Take on Haiku: Ginsberg's American Sentences

- Singing the Old Songs: Traditional and Literary Ballads

- Internet Research for Lines of Poetry

- Overview of Imagism in Poetry

- An Introduction to the Song-Like Villanelle Form of Poetry

- An Introduction to Free Verse Poetry

- What Is a Rondeau in Poetry?

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What’s Missing Here? A Fragmentary, Lyric Essay About Fragmentary, Lyric Essays

Julie marie wade on the mode that never quite feels finished.

“Perhaps the lyric essay is an occasion to take what we typically set aside between parentheses and liberate that content—a chance to reevaluate what a text is actually about. Peripherals as centerpieces. Tangents as main roads.”

Did I say this aloud, perched at the head of the seminar table? We like to pretend there is no head in postmodern academia—decentralized authority and all—but of course there is. Plenty of (symbolic) decapitations, too. The head is the end of the table closest to the board—where the markers live now, where the chalk used to live: closest seat to the site of public inscription, closest seat to the door.

But I might have said this standing alone, in front of the bathroom mirror—pretending my students were there, perched on the dingy white shelves behind the glass: some with bristles like a new toothbrush, some with tablets like the contents of an old prescription bottle. Everything is multivalent now.

(Regardless: I talk to my students in my head, even when I am not sitting at the head of the table.)

“Or perhaps the entire lyric essay should be placed between parentheses,” I say. “Parentheses as the new seams—emphasis on letting them show.”

Once a student asked me if I had ever considered the lyric essay as a kind of transcendental experience. “Like how, you know, transcendentalism is all about going beyond the given or the status quo. And the lyric essay does that, right? It goes beyond poetry in one way, and it goes beyond prose in another. It’s kind of mystical, right?”

There is no way to calculate—no equation to illustrate—how often my students instruct and delight me. HashtagHoratianPlatitude. HashtagDelectandoPariterqueMonendo.

“Like this?” I asked, with a quick sketch in my composition book:

“I don’t know, man. I don’t think of math as very mystical,” the student said, leaning—not slumping—as only a young sage can.

“But you are saying the lyric essay can raise other genres to a higher power, right?”

Horace would have dug this moment: our elective humanities class spilling from the designated science building. Late afternoon light through a lattice of wisp-white clouds. In the periphery: Lone iguana lumbering across the lawn. Lone kayak slicing through the brackish water. Some native trees cozying up to some non-native trees, their roots inevitably commingling. Hybrids everywhere, as far as the eye could see, and then beyond that, ad infinitum .

You’ll never guess what happened next: My student high-fived me—like this was 1985, not 2015; like we were players on the same team (and weren’t we, after all?)—set & spike, pass & dunk, instruct & delight.

“Right!” A memory can only fade or flourish. That palm-slap echoes in perpetuity.

“The hardest thing you may ever do in your literary life is to write a lyric essay—that feels finished to you; that you’re comfortable sharing with others; that you’re confident should be called a lyric essay at all.”

“Is this supposed to be a pep talk?” Bless the skeptics, for they shall inherit the class.

I raise my hand in the universal symbol for wait. In this moment, I remember how the same word signifies both wait and hope in Spanish. ( Esperar .) I want my students to do both, simultaneously.

“Hear me out. If you make this attempt, humbly and honestly and with your whole heart, the next hardest thing you may ever do in your literary life is to stop writing lyric essays.”

My hand is still poised in the wait position, which is identical, I realize, to the stop position. Yet wait and stop are not true synonyms, are they? And hope and stop are verging on antonyms, aren’t they? (Body language may be the most inscrutable language of all.)

“So you think lyric essays are addictive or something?” Bless the skeptics—bless them again—for they shall inherit the page.

“Hmm … generative, let’s say. The desire to write lyric essays seems to multiply over time. We continue to surprise ourselves when we write them, and then paradoxically, we come to expect to be surprised.”

( Esperar also means “to expect”—doesn’t it?)

When I tell my students they will remember lines and images from their college workshops for many years—some, perhaps, for the rest of their lives—I’m not sure if they believe me. Here’s what I offer as proof:

In the city where I went to school, there were twenty-six parallel streets, each named with a single letter of the alphabet. I had walked down five of them at most. When I rode the bus, I never knew precisely where I was going or coming from. I didn’t have a car or a map or a phone, and GPS hadn’t been invented yet. In so many ways, I was porous as a sieve.

Our freshman year a girl named Rachel wrote a self-referential piece—we didn’t call them lyric essays yet, though it might have been—set at the intersection of “Division” and “I.”

How poetic! I thought. What a mind-puzzle—trying to imagine everything the self could be divisible by:

I / Parents I/ Religion I/ Scholarships I/ Work Study I/ Vocation I/ Desire

Months passed, maybe a year. One night I glanced out the window of my roommate’s car. We were idling at a stoplight on a street I didn’t recognize. When I looked up, I saw the slim green arrow of a sign: Division Avenue.

“It’s real,” I murmured.

“What do you mean?” Becky asked, fiddling with the radio.

I craned my neck for a glimpse of the cross street. It couldn’t be—and yet—it was!

“This is the corner of Division and I!”

“Just think about it—we’re at the intersection of Division and I!”

The light changed, and Becky flung the car into gear. There followed a pause long enough to qualify as a caesura. At last, she said, “Okay. I guess that is kinda cool.”

Here’s another: I remember how my friend Kara once described the dormer windows in an old house on Capitol Hill. She wrote that they were “wavy-gazy and made the world look sort of fucked.”

I didn’t know yet that you could hyphenate two adjectives to make a deluxe adjective—doubling the impact of the modifier, especially if the two hinged words were sonically resonant. (And “wavy-gazy,” well—that was straight-up assonant.)

Plus: I didn’t know that profanity was permissible in our writing, even sometimes apropos. At this time, I knew the meaning of the word apropos but didn’t even know how to spell it.

One day I would see apropos written down but not recognize it as the word I knew in context. I would pronounce it “a-PROP-ose,” then wonder if I had stumbled upon a typo.

Like many things, I don’t remember when I learned to connect the spelling of apropos with its meaning, or when I learned per se was not “per say,” or when I realized I sometimes I thought of Kara and Becky and Rachel when I should have been thinking about my boyfriend—even sometimes when I was with my boyfriend. (He was majoring in English, too, but I found his diction far less memorable overall.)

“The lyric essay is not thesis-driven. It’s not about making an argument or defending a claim. You’re writing to discover what you want to say or why you feel a certain way about something. If you’re bothered or beguiled or in a state of mixed emotion, and the reason for your feelings doesn’t seem entirely clear, the lyric essay is an opportunity to probe that uncertain place and see what it yields.”

Sometimes they are undergrads, twenty bodies at separate desks, all facing forward while I stand backlit by the shiny white board. Sometimes they are grad students, only twelve, clustered around the seminar table while I sit at the undisputed, if understated, head. It doesn’t matter the composition of the room or the experience of the writers therein. This part I say to everyone, every term, and often more than once. My students will all need a lot of reminding, just as I do.

(A Post-it note on my desk shows an empty set. Outside it lurks the question—“What’s missing here?”—posed in my smallest script.)

“Most writing asks you to be vigilant in your noticing. Pay attention is the creative writer’s credo. We jot down observations, importing concrete nouns from the external world. We eavesdrop to perfect our understanding of dialogue, the natural rhythms of speech. Smells, tastes, textures—we understand it’s our calling to attend to them all. But the lyric essay asks you to do something even harder than noticing what’s there. The lyric essay asks you to notice what isn’t.”

I went to dances and dried my corsages. I kept letters from boys who liked me and took the time to write. Later, I wore a locket with a picture of a man inside. (I believe they call this confirmation bias .) The locket was shaped like a heart. It tarnished easily, which only tightened my resolve to keep it clean and bright. I may still have it somewhere. My heart was full, not empty, you see. I was responsive to touch. (We always held hands.) I was thoughtful and playful, attentive and kind. I listened when he confided. I laughed at his jokes. We kissed in public and more than kissed in private. (I wasn’t a tease.) When I cried at the sad parts in movies, he always wrapped his arm around. For years, I saved everything down to the stubs, but even the stubs couldn’t save me from what I couldn’t say.

“Subtract what you know from a text, and there you have the subtext.” Or—as my mother used to say, her palms splayed wide— Voilà!

I am stunned as I recall that I spoke French as a child. My mother was fluent. She taught me the French words alongside the English words, and I pictured them like two parallel ladders of language I could climb.