How to go to Heaven

How to get right with god.

What is the documentary hypothesis?

For further study, related articles, subscribe to the, question of the week.

Get our Question of the Week delivered right to your inbox!

Documentary hypothesis

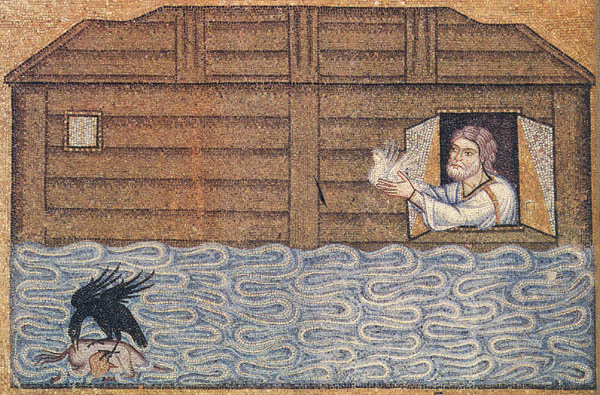

In biblical scholarship, the documentary hypothesis proposes that the Pentateuch (also called the Torah , or first five books of the Hebrew Bible ) was not literally revealed by God to Moses , but represents a composite account from several later documents. Four basic sources are identified in the theory, designated as "J" (Yahwist), "E" (Elohist), "P" (Priestly), and "D" (Deuteronomic), usually dated from the ninth or tenth through the fifth centuries B.C.E. Although the hypothesis had many antecedents, it reached its mature expression in the late nineteenth century through the work of Karl Heinrich Graf and Julius Wellhausen and is thus also referred to as the Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis.

- 2.1 Traditional Jewish and Christian beliefs

- 2.2 Rabbinical biblical criticism

- 2.3 The Enlightenment

- 2.4 Nineteenth-century theories

- 2.5 The modern era

- 2.6 Recent books

- 2.7 Criticisms of the hypothesis

- 3 Footnotes

- 4 References

- 5 External links

The documentary hypothesis has been refined and criticized by later writers, but its basic outline remains widely accepted by contemporary biblical scholars. Orthodox Jews and conservative Christians, however, usually reject the theory, affirming that Moses himself is the primary or sole author of the Pentateuch .

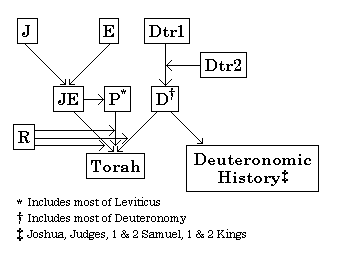

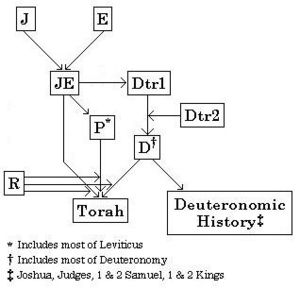

The documentary hypothesis proposes that the Pentateuch as we have it was created sometime around the fifth century B.C.E. through a process of combining several earlier documents—each with its own viewpoint, style, and special concerns—into one. It identifies four main sources:

- the "J," or Yahwist, source

- the "E," or Elohist, source (later combined with J to form the "JE" text)

- the "P," or Priestly, source

- the "D," or Deuteronomist, text (which had two further major edits, resulting in sub-texts known as Dtr1 and Dtr2)

The hypothesis further postulates the combination of the sources into their current form by an editor known as "R" (for Redactor), who added editorial comments and transitional passages.

The specific identity of each author remains unknown, (although a number of candidates have been proposed). However, textual elements identify each source with a specific background and with a specific period in Jewish history. Most scholars associate "J" with the southern Kingdom of Judah around the ninth century B.C.E. , and "E" with a northern context slightly later. Both of these sources were informed by various oral traditions known to their authors.

The combined "JE" text is thought to have been compiled in the Kingdom of Judah following the destruction of Israel by Assyria in the 720s B.C.E. "P" is often associated with the centralizing religious reforms instituted by king Hezekiah of Judah (reigned c. 716 to 687 B.C.E. ), and "D" with the later reforms Josiah (reigned c. 641 to 609 B.C.E. ). "R" is considered to have completed the work, adding transitional elements to weave the stories together as well as some explanatory comments, sometime after the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem from the Babylonian Exile in the fifth century B.C.E.

History of the hypothesis

Traditional jewish and christian beliefs.

The traditional view holds that God revealed the Pentateuch (also called the Torah ) to Moses at Mount Sinai in a verbal fashion, and that Moses transcribed this dictation verbatim. Moreover, the Ten Commandments were originally written directly by God onto two tablets of stone. Based on the Talmud (tractate Git. 60a), however, some believe that God may have revealed the Torah piece-by-piece over the 40 years that the Israelites reportedly wandered in the desert .

This tradition of Moses being the author of the Torah , long held by both Jewish and Christian authorities, was nearly unanimously affirmed with a few notable exceptions until the seventeeth century B.C.E. [1]

Rabbinical biblical criticism

Certain traditional rabbinical authorities do evidence skepticism of the Torah 's complete Mosaic authorship.

- The Talmud itself indicates that God dictated only the first four books of the Torah, and that Moses wrote Deuteronomy in his own words (Talmud Bavli, Meg. 31b). The Talmud also affirms that a peculiar section in the Book of Numbers (10:35-36) was originally a title of a separate book, which no longer exists ( Sabb. 115b).

- Recognizing that over the millennia, scribal errors had crept into the text, the Masoretes (seventh to tenth centuries C.E. ) compared all extant versions and attempted to create a definitive text.

- In the twelfth century, Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra observed that some parts of the Torah presented apparently anachronistic information, which should only have been known after the time of Moses. Later, Rabbi Joseph Bonfils explicitly stated that Joshua (or some later prophet ) must have added some phrases.

- Also in the twelfth century, Rabbi Joseph ben Isaac noted close similarities between a number of supposedly distinct episodes in Exodus and the Book of Numbers . He hypothesized that these incidents represented parallel traditions gathered by Moses, rather than separate incidents.

- In the thirteenth century, Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoah noticed the same textual anomalies that Ibn Ezra did and commented that this section of the Torah "is written from the perspective of the future." [2]

The Enlightenment

A number of Enlightenment writers expressed more serious doubts about the traditional view of Mosaic authorship. For example, in the sixteenth century, Andreas Karlstadt noticed that the style of the account of the death of Moses matched the style of the preceding portions of Deuteronomy . He suggested that whoever wrote about the death of Moses also wrote Deuteronomy and perhaps other portions of the Torah.

By the seventeenth century, some commentators argued outright that Moses did not write most of the Pentateuch . For instance, in 1651 Thomas Hobbes , in chapter 33 of Leviathan , argued that the Pentateuch dated from after Mosaic times on account of Deuteronomy 34:6 ("no man knoweth of his sepulchre to this day"), Genesis 12:6 ("and the Canaanite was then in the land"), and Num 21:14 (referring to a previous book of Moses's deeds). Other skeptics included Isaac de la Peyrère, Baruch Spinoza , Richard Simon, and John Hampden. However, these men found their works condemned and even banned.

The French scholar and physician Jean Astruc first introduced the terms Elohist and Jehovist in 1753. Astruc noted that the first chapter of Genesis uses only the word "Elohim" for God , while other sections use the word "Jehovah." He speculated that Moses compiled the Genesis account from earlier documents, some perhaps dating back to Abraham . He also explored the possibility of detecting and separating these documents and assigning them to their original sources.

Johann Gottfried Eichhorn further differentiated the two chief documents in 1787. However, neither he nor Astruc denied Mosaic authorship, and they did not analyze the Pentateuch beyond the Book of Exodus . H. Ewald first recognized that the documents that later came to be known as "P" and "J" left traces in other books. F. Tuch showed that "P" and "J" also appeared recognizably in Joshua .

W. M. L. de Wette joined this hypothesis with the earlier idea that the author(s) of the first four books of the Pentateuch did not write the Book of Deuteronomy . In 1805, he attributed Deuteronomy to the time of Josiah (c. 621 B.C.E. ). Soon other writers also began considering the idea. By 1823, Eichhorn, too, had abandoned the claim of Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.

Nineteenth-century theories

Further developments of the theory were contributed by Friedrich Bleek, Hermann Hupfeld, K. D. Ilgen, August Klostermann, and Karl Heinrich Graf. The mature expression of the documentary hypothesis, however, is usually credited to the work of Graf and Julius Wellhausen. Accordingly it is often referred to as the "Graf-Wellhausen" hypothesis.

In 1886, Wellhausen published Prolegomena to the History of Israel , [3] in which he argued that the Bible provides historians with an important source, but that they cannot take it literally. He affirmed that a number of people wrote the "hexateuch" (including the Pentateuch plus the book of Joshua ) over a long period. Specifically, he narrowed the field to four distinct narratives, which he identified by the aforementioned J ahwist, E lohist, D euteronomist and P riestly accounts. He also proposed a R edactor, who edited the four accounts into one text.

Using earlier propositions, he argued that each of these sources has its own vocabulary, its own approach and concerns, and that the passages originally belonging to each account can usually be distinguished by differences in style—especially the name used for God, the grammar and word usage, the political assumptions implicit in the text, and the interests of the author. Specifically:

- The "J" source: Here, God's name appears in Hebrew as YHWH, which scholars transliterated in modern times as “ Yahweh ” (the German spelling uses a "J," prounounced as an English "Y"). Some Bible translations use the term Jehovah for this word, but normally it is translated as "The Lord."

- The "E" source: Here, God's name is “Elohim” until the revelation of His true name to Moses in the Book of Exodus , after which God's name becomes YHWH in both sources.

- The "D" or "Dtr." source: The source of the Book of Deuteronomy and parts of the books of Joshua , Judges , Samuel , and Kings . It portrays a strong concern for centralized worship in Jerusalem and an absolute opposition to intermarriage with Canaanites or otherwise mixing Israelite culture with Canaanite traditions.

- The "P" source: This is the priestly material. It uses Elohim and El Shaddai as names of God and demonstrates a special concern for ritual , liturgy , and religious law.

Wellhausen argued that from the style and theological viewpoint of each source, one could draw important historical inferences about the authors and audiences of each particular source. He perceived an evident progression from a relatively informal and decentralized relationship between the people and God in the "J" account, to the more formal and centralized practices of the "D" and "P" accounts. Thus, the sources reveal the process and evolution of the institutionalized Israelite religion.

The modern era

Other scholars quickly responded to the documentary understanding of the origin of the five books of Moses , and within a few years it became the predominant hypothesis. While subsequent scholarship has dismissed many of Wellhausen's more specific claims, most historians still accept the general idea that the Pentateuch had a composite origin.

An example of a widely accepted update of Wellhausen's version came in the 1950s when Israeli historian Yehezkel Kaufmann published The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile (1960), in which he argued for the order of the sources as "J," "E," "P," and "D"—whereas Wellhausan had placed "P" after "D." The exact dates and contexts of each source, as well as their relationships to each other, have also been much debated.

Recent books

Richard Elliott Friedman's Who Wrote The Bible? (1981) offers a very reader-friendly and yet comprehensive argument explaining Friedman's opinions as to the possible identity of each of those authors and, more important, why they wrote what they wrote. Harold Bloom's The Book of J (1990) includes the publication of the J source only as a stand-alone document, creatively translated by co-author, David Rosenberg. Bloom argues that "J," whom he believes to be a literary genius on a par with William Shakespeare , was a woman living at the time of King Rehoboam of Judah. More recently, Israel Finkelstein (2001) and William Dever (2001) have each written a book correlating the documentary hypothesis with current archaeological research .

Criticisms of the hypothesis

Most Orthodox Jews and many conservative Christians reject the documentary hypothesis entirely and accept the traditional view that Moses essentially produced the whole Torah .

Jewish sources predating the emergence of the documentary hypothesis offer alternative explanations for the stylistic differences and alternative divine names from which the hypothesis originated. For instance, some regard the name Yahweh ( YHWH ) as an expression of God's mercifulness, while Elohim expresses His commitment to law and judgment. Traditional Jewish literature cites this concept frequently.

Over the last century, an entire literature has developed within conservative scholarship and religious communities dedicated to the refutation of biblical criticism in general and of the documentary hypothesis in particular.

R. N. Whybray's The Making of the Pentateuch offers a critique of the hypothesis from a critical perspective. Biblical archaeologist W. F. Albright stated that even the most ardent proponents of the documentary hypothesis must admit that no tangible, external evidence for the existence of the hypothesized "J," "E," "D," "P" sources exists. The late Dr. Yohanan Aharoni, in his work Canaanite Israel During the Period of Israeli Occupation , states, "[r]ecent archaeological discoveries have decisively changed the entire approach of Bible critics" and that later authors or editors could not have put together or invented these stories hundreds of years after they happened.

Some studies claim to show a literary consistency throughout the Pentateuch . For instance, a 1980 computer-based study at Hebrew University in Israel concluded that a single author most likely wrote the Pentateuch. However, others have rejected this study for a number of reasons, including the fact that a single later editor can rewrite a text in a uniform voice. [4]

- ↑ “Pentateuch” Catholic Encyclopedia . Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Shalom Carmy (ed.), Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations (Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, 1996, ISBN 978-1568214504 ).

- ↑ Prolegomena to the History of Israel by Julius Wellhausen at Project Gutenberg. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Biblical Criticism - The Jewish View, SimpleToRemember.com - Judaism Online. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

References ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph. The Pentateuch: An Introduction to the First Five Books of the Bible . Doubleday, 1992. ISBN 038541207X

- Bloom, Harold and David Rosenberg. The Book of J . Random House, 1990. ISBN 0802141919

- Carmy, Shalom (ed.). Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations . Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, 1996. ISBN 978-1568214504

- Cassuto, Umberto. The Documentary Hypothesis . Shalem, 2006. ISBN 9657052351

- Dever, William G. What Did The Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2001. ISBN 0802847943

- Finkelstein, Israel and Neil A. Silberman. The Bible Unearthed . Simon and Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684869128

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote The Bible? Harper and Row, 1987. ISBN 0060630353

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel and Moishe Greenberg (trans.). The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960. ISBN 978-0226427287

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context . Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Nicholson, Ernest Wilson. The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0198269587

- Van Seters, John. Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis . Westminster John Knox Press, 1992. ISBN 0664219675

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Hebrew Bible Timeline Chart by Mark Poyser

- "Did Moses Write the Pentateuch?" by Don Closson, Probe Ministries

- Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation - Dei Verbum by Pope Paul VI, 1965

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards . This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Documentary hypothesis history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia :

- History of "Documentary hypothesis"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- Philosophy and religion

- Pages using ISBN magic links

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please consider supporting TheTorah.com .

Don’t miss the latest essays from TheTorah.com.

Stay updated with the latest scholarship

Study the Torah with Academic Scholarship

By using this site you agree to our Terms of Use

SBL e-journal

Documentary Hypothesis: The Revelation of YHWH’s Name Continues to Enlighten

TheTorah.com

APA e-journal

When God reveals the name YHWH to Moses in Exodus, he says that not even the patriarchs knew this name, yet they all use it in Genesis. Critical scholarship’s solution to this problem led to one of the most important academic innovations in biblical studies in the last three hundred years: the Documentary Hypothesis.

Categories:

Source Criticism and the Names of God

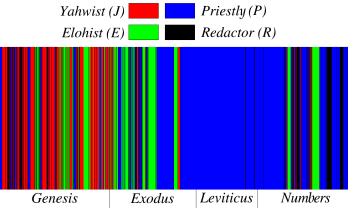

The Documentary Hypothesis (also called source criticism) in its classical form proposes that the Torah (or the Hexateuch, the Torah + Joshua) was made up of four sources, called J, E, P, and D. Alternative theories have been proposed (e.g. the supplementary hypothesis, the fragmentary hypothesis, etc.). While documentary scholars each have somewhat different nuanced versions of this hypothesis, most scholars agree on the significance of the observations that form the core of this hypothesis. One of the better-known arguments is the issue of God’s name.

The Torah contains many names for God, but two of them predominate: YHWH and Elohim . The meaning of the first one is traditionally believed to signify “The Eternal One”, but in academic circles the origin and meaning of the name is considered to be unknown. [1] The name is often left unpronounced by religious people and replaced most often with Lord ( Adonai ). [2] The second is a generic word, a common noun, for God or gods, which was also used as the name for the God of Israel.

A Short History of the Four Sources

Although many who are familiar with the Documentary Hypothesis know it to encompass four sources and the entire Torah, nevertheless, it took time and a number of intermediate steps for scholars to reach this conclusion. In the 18th century, a French physician, Jean Astruc, anonymously suggested that the two names of God in Genesis came from two different sources. He believed that these two sources, which he just called A and B, had been combined by Moses to create the book of Genesis. In 1753, he separated out these sources in his Conjectures on the original accounts of which it appears Moses availed himself in composing the Book of Genesis . [3] Over time, Astruc’s “source A” was renamed E, for Elohist, and his source B became J, for Jahwist.

Taking Astruc’s pioneering suggestion a step further, Johann Gottfried Eichhorn applied the source division to the rest of the Pentateuch. [4] This was not just an expansion, but a conceptual revolution. Astruc believed in the Mosaic authorship of the Torah. The title of his (Astruc’s) book makes it clear that he believed that Moses himself was the redactor of Genesis. Eichhorn, however, writing less than twenty years later, dispenses with the entire concept of Mosaic authorship. In his view, the Torah was put together from these two sources years after Moses lived.

The next important step in separating out sources was taken by Wilhelm M. L. de Wette. [5] De Wette showed, among other things, that Deuteronomy should be treated as a third, separate source, D (for Deuteronomist). [6] In other words, whereas the rest of the Pentateuch is made up of sources spliced together, De Wette argued that Deuteronomy should be read as a self-contained work.

Most important for the purposes of this essay, was the contribution of Herman Hupfeld. [7] Hupfeld pointed out that the Elohist source, as identified by earlier scholarship, actually is comprised of two different sources, both of which use Elohim in Genesis. Since one of these sources focuses a great deal on priestly issues, he called it P, retaining the siglum E for the non-Priestly source that uses Elohim . [8] These four sources formed the basis of the now famous Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis, which forms the basis of the various iterations of the Documentary Hypothesis known today. [9]

The Names of God in Genesis and Exodus – The Peshat Problem

Although Astruc was able to solve a number of narrative problems by dividing Genesis into two sources based on the two names of God, the biggest problem that this division solves actually appears in Exodus. In Exodus 6, God speaks to Moses:

שמות ו:ב וַיְדַבֵּר אֱלֹהִים אֶל מֹשֶׁה וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו אֲנִי יְ־הֹוָה. ו:ג וָאֵרָא אֶל אַבְרָהָם אֶל יִצְחָק וְאֶל יַעֲקֹב בְּאֵל שַׁדָּי וּשְׁמִי יְ־הֹוָה לֹא נוֹדַעְתִּי לָהֶם.

Exod 6:2 Elohim spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am YHWH. 6:3 I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai , but I did not make Myself known to them by My name YHWH.

According to the plain meaning of this passage, God is revealing to Moses a secret name, which even the patriarchs did not know. God says to Moses that God has another name, El Shaddai , which the patriarchs did know, but that the name YHWH had remained secret until this moment.

The name El Shaddai does appear in a number of the accounts of the Patriarchs in Genesis. God uses it when speaking with Abraham (17:1) and Jacob (35:11). Isaac (28:3) and Jacob (43:14, 48:3) use it when blessing or passing on messages to their sons. The name YHWH, however, also appears in the ancestral narratives. Moreover, in a number of these appearances, it is clear that the patriarchs know this name and use it.

When Eve names her son Cain (4:1), she does so to express that, “she created a man with YHWH.” [10] In the generation of Enosh, the Torah claims (4:26), the people began to call (or use) the name of YHWH. Abraham calls the name of YHWH multiple times (12:8, 13:4, 21:33), as does Isaac (26:25, 27:7, 27:27). God uses the name YHWH when speaking with Jacob (28:13) and Jacob uses it as well (28:16, 28:21, 32:10, 49:18). Sarah (16:5), Leah (29:32, 33, 35), Rachel (30:24), and Laban (30:27) know the name YHWH.

In short, when looking at all these passages, it seems clear that the name YHWH was hardly a secret and that it was well-known to the ancestors. And yet, Exodus 6:2-3 seems to be saying that they did not know it.

Traditional Solutions

The contradiction between the assertion in Exod. 6:3, that the name YHWH was unknown before this encounter, and the fact that the name is used by multiple characters in Genesis all the time, forced many traditional commentators to devise answers that would ease the tension between this verse and the accounts in Genesis.

1. Moses Anachronistically Wrote YHWH

Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra references the Karaite scholar, Yeshua, [11] who suggests that the verse means what it says: the name YHWH was unknown before Moses. He explains that it was Moses himself, who wrote the name into the stories in Genesis, but it is really an anachronism. [12] Not surprisingly, this out of the box suggestion had little caché among rabbinic commentators.

2. God Revealed Both Names to the Ancestors

Ibn Ezra also refers to the very different answer of Rav Sa’adia Gaon (10th cent.). Sa’adia states that the verse should be read with an implied “only (בלבד).” According to this interpretation, God is saying that God used both the name El Shaddai and YHWH when interacting with the patriarchs, but will use only YHWH with Moses.

Rashbam (1085-1158) and R. Joseph Bechor Shor (12th cent.) also believe that God is telling Moses that God revealed both names to the patriarchs, but they go about reading the verse in a very different manner. They suggest re-punctuating the verse by putting the comma after YHWH. The verse would then read:

Elohim spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am YHWH. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai and by my name YHWH, ( but ) I did not make Myself known to them.”

According to this reading, God tells Moses that God appeared to the Patriarchs as El Shaddai and YHWH. This solves the contradiction, but how is the reader to understand the final clause? Rashbam and Bechor Shor suggest that it means that even though God revealed God’s names, God never fulfilled the promises; “revealed” means “fulfilled” in this reading. What God tells Moses here is that this time it will be different, Moses will not only hear God’s names and God’s promises but will see their fulfillment as well.

Yet another commentator who believes the verse communicates that both names were used in revelation is R. Yehudah ha-Chasid (1140-1217). [13] He claims that the verse does not mean that God never appeared to them with the name YHWH. Of course, God did; it is documented. Instead, it means that God appeared to them with the name El Shaddai, and not YHWH, once they became Patriarchs, i.e. once they had children. Before that, God used the name YHWH.

3. The Ancestors Knew the Name But Did Not Understand It

Ibn Ezra (1089-1164) suggests that the term YHWH has both a nominal and adjectival meaning. In other words, YHWH is both a proper name, and thus designates God, and has a meaning, and can function descriptively, like some nouns do. The ancestors, he claims, were aware of the name (i.e. the proper noun) but they did not know its significance (i.e. its use as an adjectival description of God.) He claims that Moses’ understanding of the name demonstrates Moses’ greater grasp of matters divine; this is the reason that Moses could do miracles and the patriarchs could not. Hence, ibn Ezra writes, the meaning of the verse is that Moses will make the meaning of the name YHWH known to the world by performing miracles and making use of God’s power over the world.

Ramban (1194-c.1270), usually very critical of ibn Ezra, claims that in this case the philosopher hit it right on the money, the only problem being that since ibn Ezra was not a kabbalist, he didn’t truly understand the important truth he uncovered. Hence, Ramban writes, he will fill the readers in on real meaning of what ibn Ezra discovered. God appears to different prophets in distinctive emanations ( specula , from Latin, literally “windows” or “mirrors”). God appeared to the patriarchs in a dim or unclear emanation and to Moses in a bright one. The ancestors may have known the name YHWH, but they could not see God well enough to understand what it signified. Moses, on the other hand, was able to speak with God face to face and gaze upon the bright or clear emanation. Hence, it was to him that the true meaning of the name YHWH was revealed. The approach of ibn Ezra and Ramban was adopted by Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) in his Biur as the correct peshat understanding of the verse.

Rabbi Joseph ibn Kaspi (1279-1340) also interpreted the verse in this way, albeit taking a more philosophical and less kabbalistic spin. He says simply that the ancestors may have known God’s name, but they never really had complete proven understanding of the concept behind it. Moses, on the other hand, understood the concept perfectly. Ibn Kaspi’s only bone of contention with ibn Ezra focuses on what it is that Moses understood—a philosophical debate far beyond the scope of this survey.

4. Different Kinds of YHWH Revelations

A slightly different solution was offered by Maimonides’ son, Rabbi Abraham (1186-1237), in a very long excursus on this issue. Rabbi Abraham surveys a number of the main interpretations discussed here, that of Sa’adia and Rashbam, calling their answers התנצלות, apologetics. [14] He then admits that it would be worthy for him to offer apologetics as well, if he didn’t have a good answer. Luckily, however, he does (at least in his opinion).

Rabbi Abraham says that upon looking at the various revelations to the patriarchs carefully, a pattern emerges. Whenever God uses the name YHWH, God inevitably qualifies the term with a description, like “I am YHWH, who took you out of Ur Kasdim” (Gen. 12:7), or “I am YHWH, the God of Abraham your father” (Gen. 28:13). However, when God uses El Shaddai , God doesn’t qualify the name but moves on to the message, like “I am El Shaddai ; walk before me,” (Gen. 17:1) or “I am El Shaddai ; be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 35:11). However, with Moses, God simply says, “I am YHWH,” and moves on to the message, as God did with the patriarchs when using El Shaddai . The meaning of this change, R. Abraham writes, is an important philosophical secret, the explanation of which occupies the next two pages of commentary. [15]

5. The Patriarchs Never Experienced the Truth of the Revelation

The best-known answer to the contradiction comes from Rashi (1041-1105). Rashi begins by pointing out that the verse uses the niphal form of the verb and not the causative form. (Onkelos translates the verse as if it were in the causative form, but Rashi does not mention this.) The verse does not mean that God didn’t inform them of the name YHWH, Rashi argues. Instead, it means that God did not demonstrate the “truth” of the name YHWH, a name that, according to Rashi, refers to God’s capacity to fulfill God’s promises. Since God intends to fulfill the promises now, God informs Moses that the Israelites will now experience the aspect of God’s being to which the name YHWH refers.

The modern academic biblical scholar, Umberto Cassuto (1883-1951), takes Rashi’s interpretation in a slightly different direction and sharpens it. [16] Gods in the ancient world were known by their particular powers or attributes. Even if the Israelites had only one God, this God had different names. But these names functioned similar to the names of gods in general; each name specifies a particular attribute or function of the one God. Hence, Cassuto argues, from the context of the blessings to the patriarchs, who are always being told to be fruitful and multiply, the name El Shaddai should be understood as referring to God’s capacity to assist with fertility and child producing.

The name YHWH, on the other hand, should be associated with the Promised Land. Since the patriarchs were not destined to live through the conquest of the land, God communicates their blessings through the persona of El Shaddai , the aspect of God that will make them fruitful. In other words, Cassuto believes that the ancestors knew of the name YHWH, but that God never demonstrated the function of that attribute to them. Moses and the generation of the exodus, however, are supposed to be part of the conquest—until the sins in the desert change the plan—so God appears to Moses in the aspect of YHWH, the God of the land.

6. God as the Source of Good and Evil

The eclectic 19th century Italian commentator, Rabbi Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal), takes an approach somewhere between Rashi and ibn Ezra. He claims that the patriarchs never really understood the name YHWH, because that name signifies that God is the source of everything in this world, all good and all bad. Since the patriarchs never experienced anything bad (Shadal’s words not mine) they could not really digest the significance of that name. However, now that Moses has said to God (5:22): “Why have you done evil to these people?” God now has the opportunity to really explain God’s nature. God does good and bad, everything comes from God. [17]

The Source-Critical Solution

All of the above explanations use resourceful, even ingenious interpretations to solve a very problematic verse within the framework of the Torah being of single authorship. Yet the plain meaning of the verse remains that God never told the patriarchs the name YHWH, and that it was a secret until the moment of this revelation. What is the person who searches for the straightforward explanation to do with the internal biblical evidence that points to the fact that the ancestors all know this name of God starting with Eve herself and continuing all the way through Jacob!

Source criticism although may sound ominous to some, in fact solves this contradiction in an elegant and complete fashion. Exodus 6:2-12 comes from the P source, in which this revelation is the first time the name of YHWH is mentioned. God is informing Moses that he is, in fact, the first human ever to learn this name. [18] According to the J source, however, God was known as YHWH by the ancestors. Thus, the name is used ubiquitously in Genesis; it is not depicted as a once secret name. [19]

In sum, according to the Documentary Hypothesis (in simplified form), the first four books of the Torah are a combination of three sources, J, E, and P. One of the main distinguishing features of these sources is the name the human characters use for God. [20]

In the J source, YHWH was always used, going back even to primordial times. Certainly, the ancestors were well aware of it. In E and P, only Moses is first introduced to this name by God. Although E does not state specifically that the name was unknown before, the primary name of God in the E narratives is Elohim . The P source states unequivocally that before Moses no human knew this secret name of God.

Tying Up Loose Ends: Revelation of YHWH Round Two?

Hupfeld’s division between P and E solves yet another interpretive problem related to God’s name. In Exodus 3:6, God introduces Godself to Moses as the god ( elohei ) of his fathers. Moses then asks God, in v. 13, how he might respond to an Israelite question of what the name of this god is. God responds in v. 15 by telling Moses the name YHWH. Now if Moses learned this name in chapter 3, why would God present it again to Moses as the revelation of a secret name in chapter 6? The answer source criticism provides is that chapter 3 comes from the E source while chapter 6 is from the P source.

A Compelling Hypothesis

The use of different names for God was one of the first tools the early academic Bible scholars came up with to distinguish between these three main sources in Genesis-Numbers. The source distinction was developed to solve certain textual problems, and it remains a powerful tool fulfilling that purpose today as well. It remains a hypothesis—no ancient document from the Dead Sea Scrolls or elsewhere contains, e.g., the separate J or P texts of the Torah. But it is a very powerful hypothesis that offers a single explanation for many contradictions of precisely the type that midrashic texts resolve in disparate fashions.

The division of the Torah into sources is not, however, based only, or even primarily upon the different names used of God. The evidence concerning divine names overlaps with other pieces of evidence, making it a very powerful, and for many, a most-compelling hypothesis.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

January 15, 2014

Last Updated

July 27, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

[1] Many theories have been suggested, but none has garnered wide approval.

[2] In much of the biblical period, the name YHWH was likely pronounced as written. In the late biblical period, however, it became taboo to pronounce the name, and it was replaced with a surrogate. The literature from the Dead Sea Scrolls already shows this tendency very clearly, though Adonai was only one of several surrogates used.

[3] Conjectures sur les mémoires originaux, dont il paraît que Moïse s’est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse.

[4] In his five-volume Introduction to the Old Testament ( Einleitung in das Alte Testament ), pub. 1780-1783 .

[5] In his two-volume Contributions towards an Introduction to the Old Testament ( Beiträge zur Einleitung in das Alte Testament ), pub. 1806-7 .

[6] D does not include, however, the very final verses of Deuteronomy.

[7] In his The Sources of Genesis and the Nature of their Composition Re-examined ( Die Quellen der Genesis und die Art ihrer Zusammensetzung. Von neuem untersucht ), pub. 1853.

[8] For a clear analysis of some of Hupfeld’s contributions to source criticism, see the opening chapters of Joel Baden, J, E, and the Redaction of the Pentateuch (FAT 68; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009).

[9] For a color-coded, graphic display of all four sources in one version of the Documentary Hypothesis (the exact details of the divisions differ from scholar to scholar), see: Richard Elliott Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed (New York: Harper Collins, 2003).

[10] This is the text in the Masoretic Text and Samaritan Pentateuch, but the Septuagint has Elohim (θεός).

[11] Presumably, he is referring to Yeshua ben Yehudah (in Arabic: Abu al-Faraj Furqan ibn Asad), the 11th century Karaite biblical exegete.

[12] This method of answering the problem is very similar to some modern attempts to explain the appearance of the term Philistine in the Abraham story.

[13] This interpretation was inspired by Rashi’s gloss of the verse, “I appeared – to the patriarchs,” although it seems quite certain that this was not Rashi’s intention in that comment.

[14] R. Abraham does not reference Rashbam by name and it is possible that he has another commentator in mind, but with the same interpretation. In addition to these two, R. Abraham also references a comment by Yonah ibn Janach (c.990-c.1050), who says that the phrase is an oath, not a statement of fact. Unfortunately, I do not know where R. Abraham gets this from since in ibn Janach’s work, under the root ידע, he interprets the phrase as meaning “revealed” and interprets the verse to mean that God revealed Godself to Moses more fully than he did to the Patriarchs but that, nevertheless, they knew the name YHWH.

[15] This approach seems very close to that of ibn Ezra, Ramban and ibn Kaspi.

[16] Cassuto is famous for being an opponent of the Documentary Hypothesis.

[17] For a modern defense of the traditional view, see Rabbi Yehuda Rock, “Knowing the Name of God.”

[18] The sources referenced above where God uses the name El Shaddai all come from the P source as well.

[19] That P believes the special name was only introduced now represent how the period of the exodus and after was fundamentally differentiated from what preceded it, both because of the uniqueness of Moses and the reality of the looming covenant at Sinai and construction of the Tabernacle, in which YHWH would dwell among the people of Israel.

[20] According to many source critical scholars, in E, while the characters use only the name Elohim when speaking about God, until the revelation of the name YHWH in Exodus 3, the narrator’s voice sometimes uses YHWH even earlier than this. Other scholars debate this point. A unique view is that of Tzemah Yoreh ( The First Book of God, BZAW 402 [Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010], 6), who argues that the revelation of the name YHWH to Moses in Exodus 3 is a Yahwistic redaction of E, and that E uses only Elohim and never YHWH throughout its entire corpus.

Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber is the Senior Editor of TheTorah.com, and a Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute's Kogod Center. He holds a Ph.D. from Emory University in Jewish Religious Cultures and Hebrew Bible, an M.A. from Hebrew University in Jewish History (biblical period), as well as ordination ( yoreh yoreh ) and advanced ordination ( yadin yadin ) from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School. He is the author of Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception (De Gruyter 2016) and editor (with Jacob L. Wright) of Archaeology and History of Eighth Century Judah (SBL 2018).

Related Topics:

Essays on Related Topics:

Launched Shavuot 5773 / 2013 | Copyright © Project TABS, All Rights Reserved

Documentary Hypothesis

| stress on Judah | stress on northern Israel | stress on Judah | stress on central shrine |

| stresses leaders | stresses the prophetic | stresses the cultic | stresses fidelity to Jerusalem | stresses fear of the LORD | stress on law obeyed | stress on Moses' obedience | -->

| anthropomorphic speech about God | refined speech about God | majestic speech about God | speech recalling God's work |

| God walks and talks with us | God speaks in dreams | cultic approach to God | moralistic approach |

| God is YHWH | God is Elohim (till Ex 3) | God is Elohim (till Ex 3) | God is YHWH |

| uses "Sinai" | Sinai is "Horeb" | has genealogies and lists | has long sermons |

What is the Documentary Hypothesis? A Short Introduction

There are many evidences for the belief that there are multiple authors of the Pentateuch. Some examples include:

- The various names of God: Yahweh, Elohim, El Shaddai, El Elyon, etc. The different authors of these texts had divergent views of God at the times they wrote these accounts – they all experienced God in ways that were unique to them and their culture and worldviews.

- Repetitions and doublets. I have catalogued 35 stories told twice in the Pentateuch. The Documentary Hypothesis is a tool used to explain why these doublets occur, even down to the subtle (and not so subtle!) differences in these stories , explaining why we read such changes.

- Inconsistencies regarding laws – for example, there are 3 divergent slave laws in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy, all supposedly coming to us from the pen of Moses. These authors even disagree as to how old God says that mankind can live, with one author stating that there is a 120 year maximum age limit , while a different author portrays prophets living much longer than 12o years.

- Stylistic differences: once readers are aware of the different authors that have penned these texts, they can see stylistic differences readily. For example, the rule keeping Priestly author sounds much different to modern readers than the Jahwist. The narration of the story of Moses sounds much different than Exodus 36-40 where the Priestly author delves into the intricacies of the functions of the priesthood and the tabernacle. The author of Deuteronomy views the temple as a place where God will put his name, while the Priestly author sees the temple/tabernacle as a place where God dwells.

- Breaks in the text: when readers are notified to the breaks in the texts they can see where one author left off and when he picks the story up again from the previous break in the narrative. I will write more about breaks in the text in future posts, but for now, one of my favorite breaks in the text happens in Numbers 20:29. In this verse we learn that Aaron dies and that the people “mourned for thirty days, even all the house of Israel.” The text then goes on to tell other stories: the brass serpent in Numbers 21, and the Balaam/Balak episode in Numbers 22-24, both stories from a northern author – the Elohist. Then in Numbers 25 we pick up again with the Priestly author who informs readers that “behold, one of the children of Israel came and brought unto his brethren a Midianitish woman in the sight of Moses, and in the sight of all the congregation of the children of Israel, who were weeping before the door of the tabernacle of the congregation” (Numbers 25:6). Why are they mourning? The last verse of P before this was Numbers 20:29, and so after a four chapter break, P continues where it had left off, and we have the people mourning the death of Aaron from Numbers 20:29.

I highly recommend reading Richard Friedmans defense of the Documentary Hypothesis for a great introduction regarding the strength of the Documentary Hypothesis and its explanatory power.

Further reading:

Reflections on the Documentary Hypothesis by Kevin Barney

Share this:

No comments.

- The Messiness of Scripture | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- Stories told twice in the Bible | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- The story of Joseph sold into Egypt – The Documentary Hypothesis In Effect | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- Slave Laws in the Old Testament | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- Genesis 6-9 RSV with sources revealed | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- How’d We Get the Bible? (The Short Version) | LDS Scripture Teachings 2018/12/14 Permalink

- On the other side of Jordan | LDS Scripture Teachings 2019/05/31 Permalink

Comments are closed.

Designed using Unos Premium . Powered by WordPress .

- Disappearance of god Explore a chain of mysteries that concern the presence or absence of God

- Le-David Maskil: A Birthday Tribute for David Noel Freedman An homage to Noel Freedman

- The Bible Now Discover what the Hebrew Bible says or does not say about a wide range of issues

- The Hidden Face of God this inspiring work explores three interlinking mysteries

- The Exile and Biblical Narrative: The Formation of the Deuteronomistic and Priestly Works A biblical narrative

- The Exodus Real evidence of a historical basis for the exodus — the history behind the story

- The Hidden Book in the Bible Discover an epic hidden within the books of the Hebrew Bible

- The Creation of Sacred Literature: Composition and Redaction of the Biblical Text Composition and Redaction of the Biblical Text

- Who Wrote the Bible A thought-provoking and perceptive guide

- The Poet and the Historian: Essays in Literary and Historical Biblical Criticism Essays in Literary and Historical Biblical Criticism

Great to have you back

Thoughts about the documentary hypothesis.

(From the Introduction to Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism , Jeffrey Tigay, Editor)

Since the nineteenth century, the Documentary Hypothesis has been the best-known, most published, most often criticized, most thoroughly defended, and most widely taught explanation of the development of the first five books of the Bible. Evidence and arguments in support of it have grown continually more substantial—not just in quantity but in their nature, grounded more in demonstrable, quantifiable data from linguistic, literary, and archaeological products. Despite this, there have been a plethora of new models and variations proposed in recent years—some with substantial followings—and the number of claims that the Documentary Hypothesis has been overthrown has grown. Those among our colleagues who assert these claims have never challenged—in fact, have rarely mentioned—the main evidence and arguments for the hypothesis. They especially do not go near the newest strong evidence, namely: (1) linguistic evidence showing that the Hebrew of the texts corresponds to the stages of development of the Hebrew language in the periods in which the hypothesis says those respective texts were composed; (2) evidence that the main source texts (J, E, P, and D) were continuous, i. e. it is possible to divide the texts and find considerable continuity while keeping the characteristic terms and phrases of each consistent; and (3) as this book shows, evidence that the manner of composition that is pictured in the hypothesis was part of the literary practices of the ancient Near East.

To its earlier critics, the problem with the Documentary Hypothesis was that it was too hypothetical: a clever construction, perhaps, but without enough solid evidence. Two things have changed that situation over the years: the first is this acquisition of new evidence, and the second is advances in method. This book, Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism , stands out because it features both. The authors have brought new texts into the picture, which sheds light on what was or was not possible in the literature of the ancient Near East. And, at the same time, they have exercised a level of methodological sophistication that was not matched in the early stages of the field.

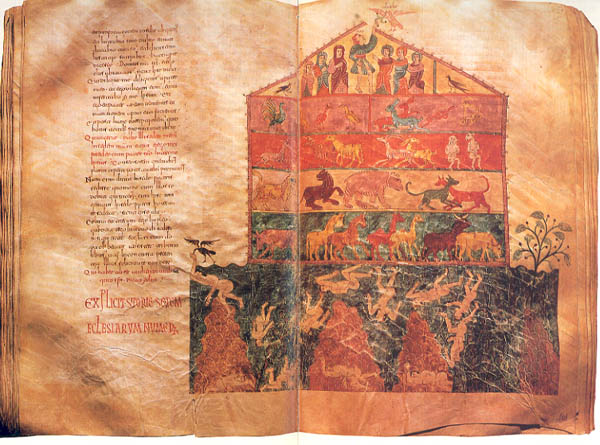

One of the early attacks on the Documentary Hypothesis was that no other works were ever composed in the manner that the hypothesis attributes to the Pentateuch. The Torah of Moses, this argument went, is being pictured as a “crazy patchwork,” having a literary history that has no parallel in the ancient Near East or in subsequent ages. Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism responds to this attack. Jerffrey Tigay and his four colleagues, Mordecai Cogan, Alex Rofé, Emmanuel Tov, and Yair Zakovitch, present what the book’s title promises: empirical models—analogous cases of composition—from the ancient Near East. They bring parallels to the manner of composition that the Documentary Hypothesis attributes to the Hebrew Bible, including parallels from the Epic of Gilgamesh , Qumran, the Septuagint, and the Samaritan Pentateuch. In an appendix, Tigay also includes George Foot Moore’s 1890 essay treating Tatian’s Diatesseron —the work that combined the New Testament’s four Gospels—as another, manifest parallel to the combining of the four pentateuchal sources in the Hebrew Bible.

Tigay’s own contributions to this volume, in particular, provide a number of cases of demonstrable parallels in works from the ancient Near East. Notably, he reviews the stages of composition of the Epic of Gilgamesh. These stages are documented, thanks to the existence of copies from several periods, and so the development of the work can be observed. Tigay and his fellow contributors also bring examples of conflation of stories in the Qumran scrolls (as in the case of the conflate text of the Decalog in the All Souls Deuteronomy Scroll); in the Septuagint (as in the Bigtan and Teresh episode in the book of Esther); in the Samaritan Pentateuch; in postbiblical literature (as in the Temple Scroll); and even in modern works. They show where literary conflation in these texts results in inconsistencies and vocabulary variation like those in the Hebrew Bible.

Not only do these ancient works involve doublets and conflation of texts in the manner of the Torah. They involve the same editorial techniques. We find, for example, cases of epanalepsis—also known as resumptive repetition or Wiederaufnahme— that is, cases in which an editor inserts material into a text and then resumes the interrupted text by restating the last line before the interruption. This is a well-known phenomenon in the Hebrew Bible as well. (See, for example, Exod 6:12 and 30, in which the words, “And Moses spoke in front of YHWH, saying, ‘. . . how will Pharaoh listen to me? And I’m uncircumcised of lips!’” come both before and after a long text that has signs of having been added to the chapter.) Also we find different names for the same character in different accounts, differences of vocabulary and style in components of a text stemming from different sources, and cases of incomplete revision of reformulated texts. Tigay demonstrates that literary conflation in these texts produces inconsistencies and vocabulary variation like those in the Hebrew Bible. Emanuel Tov as well reveals cases of homogenizing additions by editors. Tigay also observes that “a comparison of [four different] stages [in the evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic ] reveals a pattern of decreasing degrees of adaptation of earlier sources and versions.” This, too, parallels the development of the Torah, in which the exilic Deuteronomist (Dtr2) and the final Redactor (R) can now be shown (in my own research and that of others) to practice substantially less adaptation of their sources than did the earlier redactor of the J and E sources (RJE).1 What all of this book’s contributors are doing is uncovering how the editors worked. We have come a long way in this understanding. It is now possible to have a sense of the individual editors: their differences, their preferences, their methods. That is, we have reached a stage of acquaintance with the editors.

These analyses provide the visible, empirically-documented parallels that the challengers of the Documentary Hypothesis asked. But a point that we should all note here is that, even before these new analyses came to light, this argument was really no argument at all. A lack of analogies to the Torah’s literary history was never a case against that history’s reality. As Tigay puts it, “The reluctance of these writers to contemplate the possibility of something unique in Israelite literary history does not commend itself.” Indeed it does not. A vast body of evidence led to the identification of distinct source works and layers of editing in the Five Books of Moses. Numerous lines of evidence converged to point in the same direction. This convergence of evidence is what made the hypothesis so compelling a century ago and in our own day. Tigay and Rofé especially emphasize this convergence of many lines of evidence in establishing the Documentary Hypothesis. This has been the strongest argument for the hypothesis all along and the one least addressed by its opponents. One cannot challenge such a body of evidence with a simple claim that other works did not get written that way. And, as the researches in this book show, as a matter of fact other works did get written that way. These researches should bring this argument to an end, and it will not be missed. But really it never was an argument anyway.

What, after all, was the point of demanding to be shown ancient Near Eastern analogues when there was no ancient Near Eastern prose ?! The early biblical sources, being the first lengthy prose on earth, were without analogues from the get-go. If we were to acknowledge the soundness of this demand, then should we also say: the biblical text could not be prose because where is there an analogue?!

Indeed, I have occasionally heard people claim that dual variations of stories—known as doublets, such as the two accounts of Moses bringing water from rock—are a common feature of ancient Near Eastern literary works composed by single authors. But there is no such feature. Doublets can hardly be a common feature of Near Eastern prose when there is no Near Eastern prose, either in the form of history-writing or long fiction, prior to the biblical source-works that are treated in the Documentary Hypothesis. It is not even a common feature of ancient Near Eastern poetry. Where we do find the same sort of characteristics that we see in the biblical text is the Epic of Gilgamesh , and Tigay demonstrates in this volume that the Epic of Gilgamesh is a composite of edited sources very much in the manner of the Hebrew Bible. This volume thus turns a false claim on its head. The evidence from the texts of the ancient Near East is a demonstration that composition by combining sources was a known literary activity in that world.

Nonetheless the challenge persists. The most recent expression of the claim that the Documentary Hypothesis pictures something that was not a literary reality in that world came from an old friend and colleague of mine, Susan Niditch. Niditch pictures the steps of the process of editing the sources and says, “I suggest that the above imagining comes from our world and not from that of ancient Israel” (Oral World and Written Word: Ancient Israelite Literature, p. 112).

Tigay and his colleagues had shown that what is pictured in the hypothesis was very much a part of the world of ancient Israel. But Niditch, seemingly unaware that this had already been demonstrated, made this unfortunate criticism in 1996 with no citation of Tigay et al when Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism had been out for over ten years.

Even experienced biblical scholars seem not to understand how texts that are composed by more than one author come to be put together according to the hypothesis. Niditch, for example, writes:

At the heart of the documentary hypothesis. . . is the cut-and-paste image of an individual pictured like Emperor Claudius of the PBS series, having his various written sources laid out before him as he chooses this verse or that, includes this tale not that, edits, elaborates, all in a library setting. If the texts are leather, they may be heavy and need to be enrolled. Finding the proper passage in each scroll is a bit of a chore. If texts are papyrus, they are read held in the arm, one hand clasping or “supporting” the “bulk” of the scroll, while the other unrolls. Did the redactor need three colleagues to hold J, E, and P for him? Did each read the text out loud, and did he ask them to pause until he jotted down his selections, working like a secretary with three tapes dictated by the boss? (p. 113)

That is a nicely visual and witty formulation, but it is not what is pictured in the hypothesis. Precisely what makes the hypothesis seem outlandish in this formulation is what Niditch has gotten wrong. There is no juggling of multiple large, heavy scrolls. There is no one redactor who works with J, E, and P at the same time. Only two large texts are combined at each stage of the editing. J and E are combined not long after 722 BCE. P is combined with the already-edited JE some three hundred years later. I have worked with scrolls. Laying out two scrolls of the size in question and doing the editing process that actually is pictured in the hypothesis is perfectly feasible. (Anyone who has ever seen a scroll of the entire Torah in a synagogue knows that scrolls containing just JE or just P would be much smaller and quite manageable to a scribe.) And Tigay et al have shown that it is more than just feasible. It is something that was done in that literary world. Niditch says that “the hypothesized scenario behind the documentary hypothesis is flawed.” With due respect, it is Niditch’s understanding of what the hypothesis pictures that is flawed.

I do not mean to single out Niditch’s challenge as if it were something unique to her. It is just a very recent example of a long line of this type of criticism of the hypothesis. When Niditch uses language like “cut-and-paste” and “dicing and splicing source criticism” (p. 114), much like the old phrase “crazy patchwork,” she and the others who have used these phrases reveal that they have not yet come to terms with the way in which literature was in fact produced in antiquity and that they do not appreciate the artistry that it entailed, an artistry that was a collaboration of authors and editors.

One significant thing about the argument that there are no ancient parallels to the Torah as conceived in the Documentary Hypothesis is that it was of a different type from most previous arguments against the hypothesis. Traditional responses to the hypothesis had been to argue the items of evidence one at a time. Each doublet was interpreted as complimentary rather than repetitious. Each change in the divine names was explained as reflecting different divine aspects. Each contradictory datum was defended as not contradictory, or ascribed to prophecy, and so on. The documentary analysis, on the other hand, explained virtually all of the data with a very few, consistent premises. The item-by-item approach never came to terms with either the convergence of all this evidence or the economy of the explanation. The argument concerning the absence of analogous works at least was an argument against the structure of the hypothesis rather than a one-for-one series of responses that missed the forest for the trees. That is why the newer, stronger bodies of evidence for the hypothesis are so significant. They are structural defenses in terms of factors that pervade the text. The evidence of language, the evidence of continuity of texts, and the evidence regarding the literary practices of the ancient Near East are more persuasive than old claims such as that J and E use two different words for a handmaid. The force of linguistic evidence is that it is something pervasive and concrete. The same goes for the evidence in this book. What these two bodies of evidence offer together is a window into the ancient world that produced the Hebrew Bible. Works that do not take these two corpora of data into account—either accepting them or responding to them—at this point really cannot be considered to be scholarship of substance.

Among the many failures of method in recent biblical scholarship, one that stands out is the weakness in properly addressing arguments that disagree with one’s own views. Scholars argue that texts are late without addressing the linguistic evidence that they are early.3 Scholars argue that texts are composite without addressing the evidence that they are part of a single design. Other scholars argue that particular texts are unities without addressing the evidence that they are composite. This volume is a lesson to such scholarship. It faces a classic argument, takes it seriously, and brings the evidence in response to it.

Tigay discusses why it is called the Documentary Hypothesis in his introduction, referring to its hypothetical methodology (p. 2). Really, it is long past time for us to stop referring to it as a hypothesis. The state of the evidence is such that it is now—at the very least—a theory, and a well established one at that. To my mind, in the absence of any proper refutation of its strongest evidence, it is fact.

What is good about all this: Both the defenders and the critics of the Documentary Hypothesis have benefited from the process of arguing their cases. In the early days the defenders made questionable arguments based on style, foolish arguments about when a certain idea would be developed, and murky pictures of how redaction takes place. And the critics (and the defenders as well) misunderstood the “names of God” argument.4 And the critics used the argument: if an author would not include a contradiction, why would an editor?5 And they used arguments based on chiastic literary structures that supposedly could only have been fashioned by a single author.6 And they used absurd computer studies. Truly, both sides lacked a real literary sense. We needed to be prodded by non-specialists to develop a better sense of artistry and editing.

This book thus has value even beyond its stated purpose. As I indicated above, its additional value is in terms of method. Our field developed like a detective story in its early centuries. We were simply following clues that surfaced, going wherever they led us. There was little self-conscious addressing of method. The argument against the Documetary Hypothesis that “there are no ancient Near Eastern literary parallels” had worth because at least it was a methodological criticism. The authors of Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism , in responding to this argument, came to produce a project in methodology, examining our assumptions, our premises. Their work is both a vindication of the process of the Documentary Hypothesis and a lesson to scholars who come after them. The lesson is: you must address the methods by which you arrive at your conclusions. This book is thus a signpost, a contribution to our field’s evolution. Our field of research has reached a more self-critical, more sophisticated stage. To be sure, there are still plenty of scholars who have not yet come to terms with the present state of methodology. But they pay the price for this as their arguments and conclusions are more easily criticized and belied.

Much of the criticism of the Documentary Hypothesis comes from people who are not actively involved in the research. So the argument that there are no ancient Near Eastern literary parallels was easy for them. They could just say there are no parallels—without having to produce anything. But the authors of this book were willing to do the research, and they showed that there are in fact parallels. Likewise, critics who say that the “names of God” prove nothing and those who say that the presence of doublets proves nothing are persons who do not know the arguments and have not checked the texts themselves. If they had, they would know that: (1) the actual evidence concerning the name of God in each of the sources proves a great deal; and (2) the divine name argument was not in fact that different sources use the words El, Elohim, or YHWH characteristically, and the doublet argument was not simply that doublets exist. Everyone knows that a single author can use different names for the same person in a work. Everyone knows that a single author can use two similar accounts within a work. The argument was that these two things converge . When we divide up the doublets, they fall into identifiable groups in which the right name for God comes in the right place consistently, with hardly an exception in the entire Pentateuch. (In two thousand occurrences of El, Elohim, and YHWH in the Masoretic Text, there are just three exceptions.) What’s more, the other categories of evidence line up and converge with these two consistent bodies of evidence as well: We find the right terms in the right half of the doublets, we find contradictions disappearing as they fall in one group or another, we find the doublets to fall in groups that consistently fit the right stages of the Hebrew language. These critics simply do not know this evidence. Likewise they do not take on the linguistic evidence because they simply do not know it.

And then they toss off that phrase “crazy patchwork.” And they are right. In the absence of understanding the convergence of the many lines of evidence, and in the absence of awareness of the power of the linguistic evidence, it really does look like a crazy patchwork to them.

Similarly, Emanuel Tov’s chapter shows the actual process, the way this kind of composition works in practice. For those who say: show us a J text that has been found (or an E or a P), i. e. show us a source , Tov provides it. The Greek text contains just one of the two sources that were used to form the David-and-Goliath story. This criticism (“show us a source”) was another of the arguments that did not require the critics of the hypothesis to produce anything. These critics rather pressure the supporters of the hypothesis to produce something. Well, the inability to produce such evidence—viz. finding ancient Near Eastern parallels or finding a source text separately—would not have made the Documentary Hypothesis wrong anyway. But Tigay and Tov have produced it nonetheless.

Those who oppose the hypothesis are left with arguments like: the critics themselves disagree over the identification of various passages as being from one source or another. They say this as if disagreements among specialists in any field of learning are proof that the entire field is wrong. The disagreement of scholars over whether a passage is J or E is part of the normal process of refining that we expect in any healthy, honest field. Pointing to this professional process and claiming that it proves that all of the disagreeing scholars are wrong is, well, absurd. And it is an argument from weakness, something to be claimed when other arguments have failed. The only thing weaker is the claim that we still hear from time to time that “no one believes that anymore.”

As the very existence of the Diatesseron shows, the impulse to reconcile four sources is not “crazy” or even unique. What all of the examples in this book show is that editing was a fundamental part of literature well into antiquity. To state it simply: from the earliest times of the production of written works until the present day, where there are authors there are editors. The story of the formation of the Hebrew Bible is the story of a great collaboration of authors and editors (very possibly the greatest in all literature). Those who claim that this was uncommon, unlikely, uncharacteristic, unparalleled, anachronistic, or a crazy patchwork simply do not know the evidence. So, please, let us never hear the ridiculous phrase “crazy patchwork” again. If we need metaphors from the world of sewing, then we would do better to say “brilliant embroidery.”

Does Israel Have No Roots There in History?

Death and afterlife.

The Documentary Hypothesis in Trouble

By Joseph Blenkinsopp

The Pentateuch, or the five books of Moses—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy—how was it formed? What is the history of its composition?

The traditional view of both Judaism and Christianity has been that it was written by Moses under divine inspiration.

As early as the 12th century, however, the Jewish commentator Ibn Ezra raised questions about certain references that seemed to point unmistakably to events that occurred or circumstances that existed much later than Moses’ time. Some of the difficulties besetting the traditional dogma—for example, the circumstantial account of Moses’ death and burial at the end of Deuteronomy—are obvious to us today. This was not the case in the early modern period, however. Richard Simon, a French Oratorian priest now regarded as one of the pioneers in the critical study of the Pentateuch, discovered this the hard way when he published his Histoire critique du Vieux Testament (Critical History of the Old Testament) in 1678. Simon tentatively attributed the final form of the Pentateuch to scribes from the time of Moses to the time of Ezra. Simon’s work was placed on the Roman Catholic index, most of the 1,300 copies printed were destroyed and Simon himself was exiled to a remote parish in Normandy.

023 One clue modern source critics still employ to distinguish between different sources or strands in the biblical text is the use of different divine names. This technique was first employed more than 250 years ago. Some biblical passages seem consistently to refer to God by the name Yahweh ; others, by Elohim . The first person to distinguish between different sources on the basis of the divine names used in them was an obscure 024 German pastor named Witter whose work, published in 1711, went unnoticed to such an extent that it was only rediscovered about 60 years ago. The French scholar Adolphe Lods came across the book, written in Latin, while researching the early stages of Pentateuch criticism in 1924. Interestingly enough, Witter did not abandon the dogma of Mosaic authorship but simply suggested that Moses used sources recognizable by the generic divine name Elohim, as distinct from Yahweh. Yahweh was the name revealed to Moses in the wilderness ( Exodus 3:13–15 ; 6:2–3 ).

This idea was developed further, but apparently independently of Witter, by a French physician, Jean Astruc. In 1753 Astruc, on the basis of his study Genesis, identified three sources in the text: the Elohistic source (using the name Elohim ), the Jehovistic source (using the name Yahweh —or Jehovah in its Germanic form) and a remaining source that could not be attributed to either of these sources. These mémoires, as Astruc called the sources, were put together by Moses and resulted in the Pentateuch as we have it.

Astruc’s formulation was taken over and further refined by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, author of the first scientific Introduction to the Old Testament (1780). Eichhorn maintained that Moses was the author of the Pentateuch, but Eichhorn did so as a child of the Enlightenment—not for dogmatic reasons but because he believed that Moses began life as an Egyptian intellectual and then became the founder of the Israelite nation.

By the beginning of the 19th century, most Bible critics outside of the conservative ecclesiastical mainstream agreed that the Pentateuch was the result of a long process of formation, and that it was made up principally of two types of material indentified in general by their respective use of the divine names Elohim and Yahweh .

Later, the Elohist source (E) was subdivided into the Elohist (E) and another strand designated as the Priestly source (P). In its first formulation the P source was regarded as the product of priestly authors writing sometime after the Babylonian Exile 586 -->B.C. -->), when the priests assumed a dominant role in the religious life of the community. Generally, the E source was thought to be earlier than the J source, largely on the ground that, according to one biblical tradition ( Exodus 6:2–3 ), the personal divine name Yahweh was first revealed to Moses; prior to Moses’ time, God was referred to as Elohim .

One problem—and it is still a problem today—is apparent: the conclusions were drawn primarily on the basis of Genesis. Today we recognize that an explanation that seems to work well with one section of the Bible—for example, the primeval history recounted in Genesis 1–11 —might not work so well with another section—for example, the Exodus story in Exodus 1–15 .

Closer study of key passages, beginning with the work of German theologian Wilhelm de Wette in 1807, led to a reversal of the chronological order in which the sources were arranged, so that J was dated earlier than. E. De Wette also made a significant contribution by recognizing Deuteronomy as a separate source and identifying it with the book discovered, according to the Bible, during repair of the Temple fabric in the 22nd year of the reign of King Josiah (622 -->B.C. -->), the last great king of Judah. King Josiah’s religious reforms, as recounted in 2 Kings 22–23 , included the disestablishment of the “high places” and an insistence on the exclusiveness of the single central sanctuary in Jerusalem. Since this corresponds closely with the legal viewpoint in Deuteronomy (especially 12:1–14 ), de Wette was able to identify the fifth book of the Pentateuch as the book the Bible tells us was discovered in the cleansed Jerusalem Temple or, as de Wette maintained, as the book that was “planted” in the temple by the priests. De Wette’s hypothesis, which won wide acceptance, was to become a pivotal point in the study of the Pentateuch, since it made possible a distinction between earlier legislation not in accord with Deuteronomy and later enactments that presupposed it.

The ground was thus prepared for the classic statement of the documentary hypothesis developed by the Strasbourg professor Eduard Reuss (1804–1891), together with his student and friend Karl Heinrich Graf (1815–1869), and formulated with unsurpassed brilliance and clarity in Julius Wellhausen’s Prolegomena to the History of Israel in 1883. This so-called higher criticism was carried on for the most part in Germany, which has always been the heartland of biblical and theological study in the modern period. In the English-speaking world, where conservative ecclesiastical influences were more in evidence, the documentary hypothesis took root much later. As late as 1880, the vast majority of biblical scholars in Britain and America supported the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.

The literary analysis embodied in the higher criticism not only attempted to explain the compositional history of the Pentateuch, it also served as the basis for reconstructing the evolution of religious ideas in Israel and early Judaism. The earliest sources, J and E (which Wellhausen wisely did not try to distinguish too systematically), were thought to reflect a more primitive stage of nature religion based on the kinship group. Deuteronomy (D), on he other hand, recapitulated prophetic religion; at same time, Deuteronomy brought the age of 025 prophecy to an end by the issuance of a written law. For most scholars in the 19th century, the prophets, with their elevation of ethics over cult and their unmediated approach to God, represented the apex of religious development. Accordingly, after the age of prophecy came to an end, there was nowhere to go but down. The last stage Israel’s religious development, reflecting a theocratic world view, found expression in the, Priestly source (P) from the Exilic or early post-Exilic period (sixth-fifth century -->B.C. -->).

This kind of evolutionism, which drew heavily on German Romanticism and the philosophy of Hegel, is fortunately no longer in favor. What remains as a task for scholarship today is a more careful evaluation of the arguments on which the documentary hypothesis is based.

Since the publication of Wellhausen’s Prolegomena it has become apparent that all four strands of the Pentateuch—J, E, P and D—are themselves composites. But the attempt to break them down into their components (J 1 , J 2 , for example) has led increasingly to frustration and has contributed to the current widespread disillusionment with the docmentary hypothesis.

There have always been those who either questioned one or another aspect of the documentary hypothesis or, like the Jewish scholars Yehezkel Kaufmann and Umberto Cassuto, have rejected it outright. In the last decade, however, doubts have begun to be raised by biblical scholars standing in the critical mainstream. A more detached investigation of key passages, especially in Genesis, has suggested that the criteria for distinguishing between the “classical” sources (J, E, P, D and their subdivisions) can no longer be taken for granted. The distinction between J and E (J’s ghostly Doppelgänger ) has always been problematic, and there has never been complete consensus on the existence of E as a separate and coherent narrative. In the years shortly after World War II, the Yahwist(J) achieved a high degree of individuality as the great theologian the early monarchy (tenth or ninth century -->B.C. -->), largely due to the influential work of the Heidelberg Old Testament scholar Gerhard von Rad. During the last decade, however, growing doubts have emerged about the date, the extent and even the existence of J as a separate and cohesive source spanning the first five or six books of the Bible. Similar if less insistent doubts have been voiced about the date of the Priestly source (P) and its relation to earlier traditions in the Pentateuch