- Research Matters — to the Science Teacher

Pedagogical Content Knowledge: Teachers' Integration of Subject Matter, Pedagogy, Students, and Learning Environments

"Those who can, do. Those who understand, teach." (Shulman, 1986, p. 14)

Introduction

Recently, there has been a renewed recognition of the importance of teachers' science subject matter knowledge, both as a function of research evidence (e.g., Ball & McDiarmid, 1990; Carlsen, 1987; Hashweh, 1987), and as a function of literature from reform initiatives such as the Holmes Group (1986) and the Renaissance Group (1989). Not surprisingly, it has become clear that both teachers' pedagogical knowledge and teachers' subject matter knowledge are crucial to good science teaching and student understanding (Buchmann, 1982, 1983; Tobin & Garnett, 1988).

The recent development of the National Science Education Standards (NRC, 1996) and the Benchmarks for Science Literacy (AAAS, 1993) as well as a multitude of state, district, and school level content area standards, have further renewed emphasis on the importance of subject matter. Moreover, these documents contain not only key subject matter concepts for student learning, but they also inform pedagogical issues related to science subject matter content.

The Nature of Pedagogical Content Knowledge

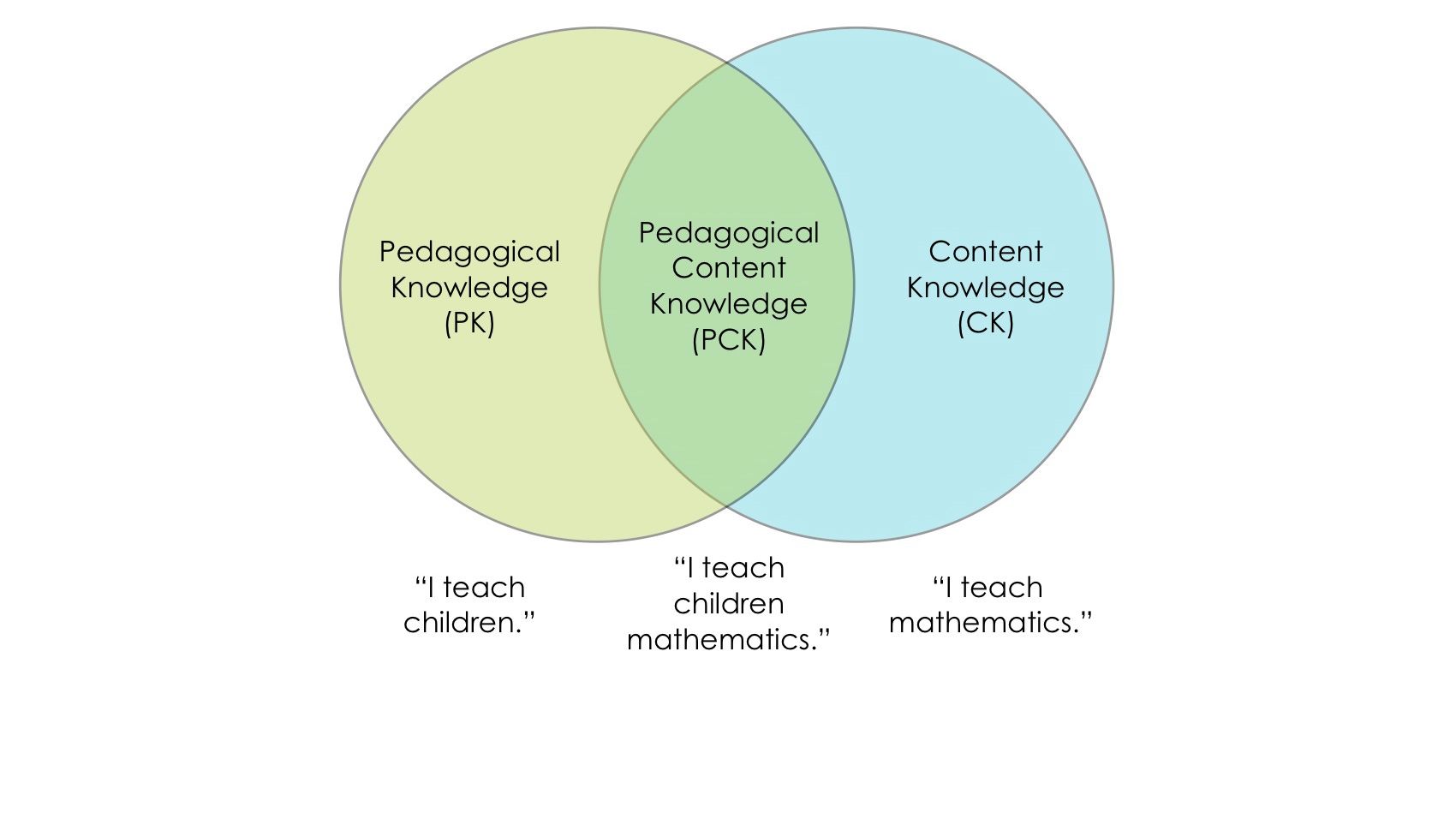

In addition to teachers' subject matter (content) knowledge and their general knowledge of instructional methods (pedagogical knowledge), pedagogical content knowledge was originally suggested as a third major component of teaching expertise, by Lee Shulman (1986; 1987) and his colleagues and students (e.g. Carlsen, 1987; Grossman, Wilson, & Shulman, 1989; Gudmundsdottir, 1987a, 1987b; Gudmundsdottir & Shulman, 1987; Marks, 1990). This idea represents a new, broader perspective in our understanding of teaching and learning, and a special issue of the Journal of Teacher Education (Ashton, 1990) was devoted to this topic.

Pedagogical content knowledge is a type of knowledge that is unique to teachers, and is based on the manner in which teachers relate their pedagogical knowledge (what they know about teaching) to their subject matter knowledge (what they know about what they teach). It is the integration or the synthesis of teachers' pedagogical knowledge and their subject matter knowledge that comprises pedagogical content knowledge. According to Shulman (1986) pedagogical content knowledge

. . . embodies the aspects of content most germane to its teachability. Within the category of pedagogical content knowledge I include, for the most regularly taught topics in one's subject area, the most useful forms of representation of those ideas, the most powerful analogies, illustrations, examples, explanations, and demonstrations - in a word, the ways of representing and formulating the subject that make it comprehensible to others . . . [It] also includes an understanding of what makes the learning of specific concepts easy or difficult: the conceptions and preconceptions that students of different ages and backgrounds bring with them to the learning (p. 9).

Pedagogical content knowledge is a form of knowledge that makes science teachers teachers rather than scientists (Gudmundsdottir, 1987a, b). Teachers differ from scientists, not necessarily in the quality or quantity of their subject matter knowledge, but in how that knowledge is organized and used. In other words, an experienced science teacher's knowledge of science is organized from a teaching perspective and is used as a basis for helping students to understand specific concepts. A scientist's knowledge, on the other hand, is organized from a research perspective and is used as a basis for developing new knowledge in the field. This idea has been documented in Biology by Hauslein, Good, & Cummins (1992), in a comparison of the organization of subject matter knowledge among groups of experienced science teachers, experienced research scientists, novice science teachers, subject area science majors, and preservice science teachers. Hauslein et al. found that science majors and preservice teachers both showed similar, loosely organized subject matter knowledge; and that the subject matter knowledge of the novice and experienced teachers and the research scientists was much deeper and more complex. However, compared to the researchers (who showed a flexible subject matter structure), the teachers showed a more fixed structure, hypothesized to result from curriculum constraints.

Cochran, DeRuiter, & King (1993) revised Shulman's original model to be more consistent with a constructivist perspective on teaching and learning. They described a model of pedagogical content knowledge that results from an integration of four major components, two of which are subject matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. The other two other components of teacher knowledge also differentiate teachers from subject matter experts. One component is teachers' knowledge of students' abilities and learning strategies, ages and developmental levels, attitudes, motivations, and prior knowledge of the concepts to be taught. Students' prior knowledge has been especially visible in the last decade due to literally hundreds of studies on student misconceptions in science and mathematics. The other component of teacher knowledge that contributes to pedagogical content knowledge is teachers' understanding of the social, political, cultural and physical environments in which students are asked to learn. The model in Figure 1 shows that these four components of teachers' knowledge all contribute to the integrated understanding that we call pedagogical content knowledge; and the arrows indicate that pedagogical content knowledge continues to grow with teaching experience. The integrated nature of pedagogical content knowledge is also described by Kennedy (1990).

Research Evidence

Hashweh (1985, 1987) conducted an extensive study of three physics teachers' and three biology teachers' knowledge of science and the impact of that knowledge on their teaching. All six teachers were asked about their subject matter knowledge in both biology and physics, and they were asked to evaluate a textbook chapter and to plan an instructional unit on the basis of that material. Given a concept like photosynthesis for example, the biology teachers knew those specific misconceptions that students were likely to bring to the classroom (such as the idea that plants get their food from the soil) or which chemistry concepts the students would need to review before learning photosynthesis. The biology teachers also understood which ideas were likely to be most difficult (e.g. how ATP-ADP transformations occur) and how best to deal with those difficult concepts using a variety of analogies, examples, demonstrations and models. The biology teachers could describe multiple instructional "tools" for these situations; but, although they were experienced teachers, they had only very general ideas about how to teach difficult physics concepts. The physics teachers, on the other hand, could list many methods and ideas for teaching difficult physics concepts, but had few specific ideas for teaching difficult biology concepts.

When the teachers in Hashweh's study were asked about their subject matter knowledge in the field that was not their specific field, they showed more misconceptions, more misunderstandings, and a less organized understanding of the information. Within their own fields, they were more sensitive to subtle themes presented in textbooks, and could and did modify the text material based on their teaching experiences. Moreover, they were more likely to discover and act on student misconceptions. The teachers used about the same number of examples and analogies when planning instruction in both fields, but those analogies and examples were more accurate and more relevant in the teachers' field of expertise.

Other studies have shown that new teachers have incomplete or superficial levels of pedagogical content knowledge (Carpenter, Fennema, Petersen, & Carey, 1988; Feiman-Nemser & Parker, 1990; Gudmundsdottir & Shulman, 1987; Shulman, 1987). A novice teacher tends to rely on unmodified subject matter knowledge (most often directly extracted from the curriculum) and may not have a coherent framework or perspective from which to present the information. The novice also tends to make broad pedagogical decisions without assessing students' prior knowledge, ability levels, or learning strategies (Carpenter, et al., 1988). In addition, preservice teachers have been shown to find it difficult to articulate the relationships between pedagogical ideas and subject matter concepts (Gess-Newsome & Lederman, 1993); and low levels of pedagogical content knowledge have been found to be related to frequent use of factual and simple recall questions (Carlsen, 1987). These studies also indicate that new teachers have major concerns about pedagogical content knowledge, and they struggle with how to transform and represent the concepts and ideas in ways that make sense to the specific students they are teaching (Wilson, Shulman, & Richert, 1987). Grossman (1985, cited in Shulman, 1987) shows that this concern is present even in new teachers who possess the substantial subject matter knowledge gained through a master's degree in a specific subject matter area, and Wilson (1992) documents that more experienced teachers have a better "overarching" view of the content field and on which to base teaching decisions.

These and other studies show that pedagogical content knowledge is highly specific to the concepts being taught, is much more than just subject matter knowledge alone, and develops over time as a result of teaching experience. What is unique about the teaching process is that it requires teachers to "transform" their subject matter knowledge for the purpose of teaching (Shulman, 1986). This transformation occurs as the teacher critically reflects on and interprets the subject matter; finds multiple ways to represent the information as analogies, metaphors, examples, problems, demonstrations, and/or classroom activities; adapts the material to students' developmental levels and abilities, gender, prior knowledge, and misconceptions; and finally tailors the material to those specific individual or groups of students to whom the information will be taught. Gudmundsdottir (1987a, b) describes this transformation process as a continual restructuring of subject matter knowledge for the purpose of teaching; and Buchmann (1984) discusses the importance of science teachers maintaining a fluid control or "flexible understanding" (p. 21) of their subject knowledge, i.e. be able to see a specific set of concepts from a variety of viewpoints and at a variety of levels, depending on the needs and abilities of the students.

Recommendations for Teachers

To become more aware of this knowledge and to be able to more clearly think about it, teachers can find ways to keep track of this information, just as they ask students to do with the data collected in lab assignments. One way is to keep a personal notebook describing their teaching, even just once a week or so for a few difficult concepts. Another strategy is to videotape or audiotape a few class periods just to help see what's happening in the classroom. (It's not necessary to have anyone but the teacher see or listen to the tape.) Then teachers can start to think about the following types of questions. Which ideas need the most explanation? Why are those ideas more difficult for the students? What examples, demonstrations, and analogies seemed to work the best? Why did they work or not work? Which students did they work best for ?

- Teachers can try new ways of exploring how the students are thinking about the concepts being taught. Ask students about how and what they understand (not in the sense of a test, but in the sense of an interview). Ask students what "real life" personal situations they think science relates to. Try to get inside their heads and see the ideas from their point of view.

- Start discussions with other teachers about teaching. Take the time to find someone you can share ideas with and take the time to learn to trust each other. Exchange strategies for teaching difficult concepts or dealing with specific types of students. Get involved in a peer coaching project in your school or district. District faculty development staff or people at a local university can help you get one started and may be able to provide substitute support. Ask about telephone hot-lines and computer networks for teachers, and explore the world wide web.

- Get involved in action research projects. Much of the newestM and most important research is being conducted by teachers. Take a class at your nearest university and find out what is going on. Get involved with a mentor teacher program or a teacher on special assignment program. Join organizations and go to conferences such as the national or regional National Science Teachers Association or the NARST meetings. There are also often summer workshops and institutes in specific fields in science at many universities and colleges.

Where Should We Go From Here?

Contemporary research has focused on how to describe teachers' pedagogical content knowledge and how it influences the teaching process. We have yet, however, to fully understand the four components of this model, and we have yet to clearly understand how they really develop. We also know very little about how to enhance pedagogical content knowledge in preservice and inservice programs. Teacher involvement in research and university preparation programs is crucial for the development of this important idea and its usefulness for the improvement of science teaching.

by Kathryn F. Cochran, University of Northern Colorado

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (1993). Benchmarks for Science Literacy. New York: Oxford University Press. Ashton, P. T. (Ed.). (1990). Theme: Pedagogical Content Knowledge [Special issue]. Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (3). Ball, D. L., & McDiarmid, G. W. (1990). The subject matter preparation of teachers. In W. R. Houston, M. Haberman, & J. Sikula (Eds.). Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 437-449). New York: Macmillan. Buchmann, M. (1982). The flight away from content in teacher education and teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 14 , 1. Buchmann, M. (1984). The flight away from content in teacher education and teaching. In J. Raths & L. Katz (Eds.). Advances in teacher education (Vol. 1, pp. 29-48). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Carlsen, W. S. (1987). Why do you ask? The effects of science teacher subject-matter knowledge on teacher questioning and classroom discourse. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service NO. ED 293 181). Carpenter, T. P., Fennema, E., Petersen, P., & Carey, D. (1988). Teachers' pedagogical content knowledge of students' problem solving in elementary arithmetic. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 19 , 385-401. Cochran, K. F., DeRuiter, J. A., & King, R. A. (1993). Pedagogical content knowing: An integrative model for teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education, 44 , 263-272. Feiman-Nemser, S., & Parker, M. B. (1990). Making subject matter part of the conversation in learning to teach. Journal of Teacher Education, 41 , 32-43. Gess-Newsome, J., & Lederman, N. (1993). Preservice biology teachers' knowledge structures as a function of professional teacher education: A year-long assessment. Science Education, 77 , 25-45. Grossman, P. L., Wilson, S. M., & Shulman, L. (1989). Teachers of substance: Subject matter knowledge for teaching. In M. C. Reynolds (Ed.). Knowledge base for the beginning teacher (pp. 23-36). Oxford: Pergamon Press. Gudmundsdottir, S. (1987a). Learning to teach social studies: Case studies of Chris and Cathy. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Washington, D.C. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service NO. ED 290 700) Gudmundsdottir, S. (1987b). Pedagogical content knowledge: teachers' ways of knowing. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Washington, D.C. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service NO. ED 290 701) Gudmundsdottir, S. & Shulman, L. (1987). Pedagogical content knowledge in social studies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 31 , 59-70. Hashweh, M. Z. (1987). Effects of subject matter knowledge in the teaching of biology and physics. Teaching and Teacher Education, 3 , 109-120. Holmes Group. (1986). Tomorrow's teachers: A report of the Holmes Group. East Lansing, MI: The Holmes Group. Kennedy, M. (1990). Trends and Issues in: Teachers' Subject Matter Knowledge. Trends and Issues Paper No. 1. ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education, Washington, DC. (ED#322 100) Marks, R. (1990). Pedagogical content knowledge: From a mathematical case to a modified conception. Journal of teacher education, 41 , 3-11. National Research Council. (1996). National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Renaissance Group. (1989). Teachers for the new world: A statement of principles . Cedar Falls, IA: The Renaissance Group. Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4-14. Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57 , 1-22. Tobin, K., & Garnett, P. (1988). Exemplary practice in science classrooms. Science Education, 72, 197-208. Wilson, J. M. (1992, December). Secondary teachers' pedagogical content knowledge about chemical equilibrium. Paper presented at the International Chemical Education Conference, Bangkok, Thailand. Wilson, S. M., Shulman, L. S., & Richert, A. E. (1987). '150 different ways' of knowing: Representation of knowledge in teaching. In J. Calderhead (Ed.). Exploring teachers' thinking (pp. 104-124). London: Cassell.

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Teaching — The idea and conception of pedagogical content knowledge

The Idea and Conception of Pedagogical Content Knowledge

- Categories: Teaching

About this sample

Words: 2792 |

14 min read

Published: Oct 31, 2018

Words: 2792 | Pages: 6 | 14 min read

Table of contents

Criticisms with pck, models based on pck., pck/mkt and student learning, commonalties of pck in research, gaps in the pck research.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1783 words

4 pages / 1993 words

5 pages / 2173 words

2 pages / 1028 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Teaching

Teachers should be paid more. This statement reflects a sentiment shared by many who recognize the vital role that educators play in shaping the future of individuals and societies. In a world where education forms the [...]

Process analysis essays are an important genre of writing that focuses on explaining how a particular process works or how to perform a specific task. These essays provide step-by-step instructions to guide the reader through [...]

Teaching is often considered one of the noblest professions, and for good reason. The impact a teacher can have on a student's life is immeasurable, shaping their future and influencing their personal and professional [...]

Effective teaching is a cornerstone of successful learning and personal development. The art of teaching involves more than delivering information; it encompasses a set of principles that guide educators in creating meaningful [...]

The purpose of this essay is to critically reflect on providing supervision and mentoring support to others within the work place through teaching, learning and assessment. Evidence will be drawn from knowledge and understanding [...]

Dictionaries play a key role in language acquisition and teaching as they enhance learners’ autonomy. In this regard, in order to avoid asking a teacher frequently, a dictionary which is chosen meticulously may well be a wise [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Chapter 4: The Art and Science of Teaching—Pedagogical Content Knowledge

- What is the academic content scope and sequence for the content standard in the subject(s) that I teach?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of content standards?

- What are the most important ideas and skills you will be responsible for teaching?

- How do wise teachers maximize the use of content standards?

Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Effective teachers not only possess certain kinds of personality traits, skills, and dispositions, but they also have a certain kind of knowledge. Effective teachers possess a unique kind of knowledge known as pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) . PCK blends an understanding of content and pedagogy specifically for instruction. Lee Shulman (1987) coined this term and has written about it extensively. Here is a brief video that aptly explains this concept.

Very few ideas in the social sciences have a shelf-life longer than a few years. In education, for example, Lev Vygotsky’s (1896-1934) theory of social constructivism , Jerome Bruner’s (1915 – 2016) spiral curriculum, and Lee Shulman’s (1938 – ) PCK are three prominent examples. Below is Shulman’s seminal essay on PCK–an idea that has been used extensively across teacher education.

Read: Shulman, Lee S. “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching.” Journal of Education. 193, no. 3 (2013): 1-11.

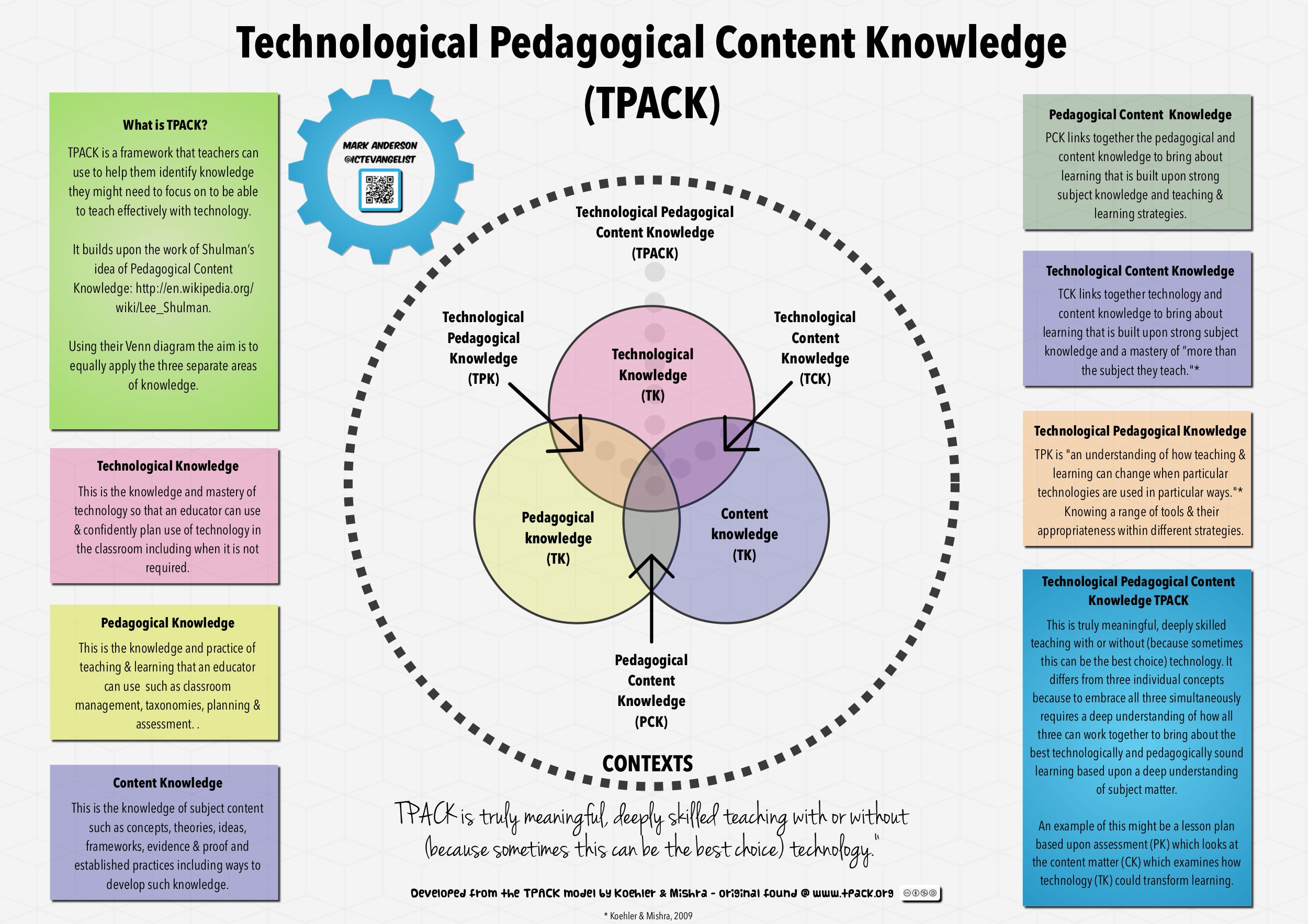

Technical Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Shulman’s ideas about what teachers need to know were powerful enough for others to add to them. In 1986, technology and its applications to teaching and learning were just beginning. As educators began to recognize the potential applications of technology to teaching, Shulman’s original model of teacher knowledge expanded to include knowledge of technology.

Read: Koehler, Matthew J. “What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)?” Journal of Education. 193, no. 3 (2013): 13-19.

Is Teaching an Art, Science, or Both?

The intellectual challenge of being a great teacher–whether for kindergartners or graduate students–is partly what motivates us 25+ years after beginning our careers. We are constantly learning, never satisfied, and continually trying to make our courses (and eBooks!) a little better. Watch the video below and ask yourself the age-old question, “Is teaching an art, science, or both?”

Our Perspective

Effective teaching is both art and science. Everything that constitutes the knowledge base of effective teaching cannot be reduced to a list of evidence-based practices, strategies, or skills. That is not to say that those lists are not helpful; they are. But effective teaching is somewhere in the mixture of art and science. Science provides a knowledge base of ideas that are helpful, perhaps necessary, in learning to teach; however, teaching is a performance art that also requires experience, intuition, creativity, and a host of other artistic elements. In fact, great teachers often seek balance between the teaching virtues. Great teachers balance confidence with humility; clarity with creativity; being businesslike with the ability to be warm and humorous, to name a few examples. And, any virtue taken to an extreme may hinder your effectiveness as a teacher; perhaps Aristotle was right, any virtue can become a vice?

Core Teaching Skills Copyright © 2020 by Thomas Vontz and Lori Goodson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- Back to parent navigation item

- Collections

- Sustainability in chemistry

- Simple rules

- Teacher well-being hub

- Women in chemistry

- Global science

- Escape room activities

- Decolonising chemistry teaching

- Teaching science skills

- Get the print issue

- RSC Education

- More navigation items

Apply your learning

By David Read 2022-01-04T07:30:00+00:00

- No comments

Discover how training in pedagogical content knowledge for one topic can improve your teaching

To be effective in the classroom, trainee teachers must develop their knowledge base. Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) is the specific practical knowledge required to support learners in grasping and applying subject understanding. PCK distinguishes chemistry teachers from chemists. It’s also topic-specific, so its development is time-consuming, given the number of topics within chemistry.

Source: © Klaus Vedfelt/Getty Images

Outline the big ideas to reel students in from getting lost in the complexity of concepts underpinning chemistry topics

In a recent study, Sevgi Aydin-Gunbatar and Fatma Nur Akin provided teachers with PCK training on a specific chemistry topic. They explored the trainees’ abilities to apply their knowledge in a different topic area.

Transformative training

The study involved 13 trainees on a four-year programme in Turkey. Their PCK training took place over 12 weeks. The training emphasised the process learners follow to master topics, known as transformation. It also focused on content knowledge of particle motion and organisation in different states, and the sequence of concepts that make up the topic. Trainees explicitly discussed the points that make the topic difficult for learners. Later, the group addressed the difficulties of selecting teaching methods.

The trainees played the role of students in a mock lesson. The researchers demonstrated conceptual change strategies to address the alternate conception that matter has a continuous structure in which there is no empty space. The researchers showed how to assess students’ ability to link concepts with concept maps. They used carefully chosen language throughout so trainees became accustomed to the role of the different components of PCK in transformation, such as ‘knowledge of learners’ and ‘assessment of learners’.

The researchers probed the teachers’ abilities to independently develop PCK in acid–base equilibrium, which was not covered in their training. They found that 11 of the 13 trainees significantly improved their PCK in acid–base equilibrium.

The bigger picture

Qualitative data showed that trainees improved their abilities at outlining the big ideas of the topic and at sequencing different concepts to support learners. Before their training, the teachers were unsure what to teach or how to identify the relevant big ideas. The participants also improved their ability to identify what students would struggle with and possible alternate conceptions. They could also identify suitable teaching and assessment strategies more effectively.

Teaching tips

- Read Building pedagogical content knowledge for more insights into developing PCK.

- Reflect on what students find difficult. Try to see things from their perspective to anticipate their difficulties and alternative conceptions.

- Ensure teaching strategies will help students address difficulties.

- Select assessment strategies that will identify problem areas. Use assessment outcomes to drill further into the difficulties students have experienced. Although there is a place for testing recall of concepts, assessment methods that provide insight into student understanding will be more valuable.

- Provide feedback that will help steer students in the right direction.

- Developing PCK is a career-long activity, and discussing it with colleagues is one of the most valuable tools to support it.

S Aydin-Gunbatar and F N Akin, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. , 2021, 22 , DOI: 10.1039/d1rp00106j

- Developing subject knowledge

- Developing teaching practice

- Education research

- Evidence-based teaching

Related articles

Strengthen your teaching practice with targeted CPD

2024-03-18T05:00:00Z By David Read

Discover why subject knowledge always packs a punch in the classroom

Understanding how students untangle intermolecular forces

2024-03-14T05:10:00Z By Fraser Scott

Discover how learners use electronegativity to predict the location of dipole−dipole interactions

Why I use video to teach chemistry concepts

2024-02-27T08:17:00Z By Helen Rogerson

Helen Rogerson shares why and when videos are useful in the chemistry classroom

No comments yet

Only registered users can comment on this article., more education research.

Unpacking representations

2024-08-06T05:04:00Z By David Read

Teach learners how to interpret and compare different chemical representations

Improve your learners’ NMR interpretation skills

2024-07-11T04:59:00Z By Fraser Scott

Encourage students to determine and draw the structures of simple organic molecules with this free, online resource

How best to engage students in group work

2024-06-11T05:19:00Z By David Read

Use evidence-based research to help students get the most out of group work

- Contributors

- Print issue

- Email alerts

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

TEACHERS' PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE AND STUDENTS' ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT: A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW

Teachers are the most important factor in students' learning, yet little is known about the specialized knowledge held by experienced teachers. In recent years, discourse on teachers' content knowledge (TCK), pedagogy knowledge (TPK), and pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) on students' learning outcomes have attracted increasing attention from several agents of change in the education industry. Conceptualizing teacher knowledge is a complex issue that involves understanding key underlying phenomena such as the process of teaching and learning, the concept of knowledge, as well as the way teachers' knowledge is put into action in the classroom. Empirical research shows that teacher quality is an important factor in determining gains in students' achievement. By inadequately explaining teachers' knowledge, existing educational production function research could be limited in its conclusions, not only by the magnitude of effects that teachers' knowledge has on students' learning but also about the kinds of teacher knowledge that matters most in producing students' learning outcomes. Teachers are expected to process and evaluate new knowledge relevant for their core professional practice and to regularly update their profession's knowledge base. This article reviews literature related to the concept of teachers' pedagogical content knowledge in enhancing students' academic achievement.

Related Papers

Pedagogi: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan

Yusuf O . Shogbesan

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Soledad Estrella , Raimundo Olfos , Tatiana Goldrine

When the studies carried out about the areas of knowledge that a teacher should have are examined, three categories are found as: “content knowledge”, “pedagogical knowledge”, and “general cultural knowledge” in our country. But in the recent years, a forth knowledge area called the “pedagogical content (PCK)” which is as significant as the other three knowledge areas is introduced and the courses have been started for the acquisition of this knowledge in teacher training programs. In this study, first, the emergence of the PCK and the definitions made by various researchers are presented. Second, the elements of the PCK and the development models are explained. Third, the samples of the studies conducted on the PCK in the literature are reviewed. Finally, suggestions are made about how to develop preservice and in-service teachers’ PCK and to keep the continuity of this knowledge.

Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education

Margaret Walshaw

Education Research International

Scholarly Research Journal For Interdisciplinary studies

Ritendra Roy , Sudhindra Roy

Teacher is one of the important components of education system. The quality and extent of learner achievement are determined primarily by teacher competence, sensitivity and teacher motivation (NCFTE, 2009). The achievement of the educational goals largely depends on the quality and standard of the teacher. Thus it is important to make them prepare for the future or upgrade their knowledge with new concepts to address the better quality and standard of them. Pedagogical content knowledge is one of such emerging concept which should be integrated in the curriculum of teacher education at all the level i.e. D.El.Ed, B.Ed or M.Ed. Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) is a type of knowledge unique to teachers. PCK concerns the manner in which teachers relate their pedagogical knowledge to their subject matter knowledge in the school context for teaching students with specific level of understanding (Shulman, 1986). It is the integration of teacher pedagogical knowledge with their subject matter knowledge in the specific context so that definite needs of the group of students as well as individual students can be addressed and make the learning simple to understand. In a country like India where the teachers have to deal with different context and different level of understanding of the students PCK of the teacher is more important instead of the content knowledge or pedagogical knowledge singly. This paper will try to define and explore the concept PCK followed by explaining the need of implementing the concept PCK in Indian Teacher Education curriculum and thereby will try to identify the elements related to PCK that has been mentioned in the new NCTE regulation i.e. National Council for Teacher Education (Recognition Norms and Procedure) Regulations, 2014.

Masoud Mahmoodi-Shahrebabaki

Literacy instructors are encountering accumulative challenges in today`s classrooms. Large-scale high-stake assessments and managerial/parental expectations have doubled the pressure on teachers to produce high-achieving literacy learners. One of the chief aspects the teacher training programs have been focusing on lately has been the notion of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). This paper provides an overview of the PCK and how it can be used optimally in classrooms. This article is concluded by some suggestions and arguments on the reciprocal correlations between PCK and effective practice.

Juan-Miguel Fernández-Balboa

Teaching and teacher education

Denise Spangler

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Freddie Bowles

Deisi Yunga

Rohaida Saat

Sevgi AYDIN , Betul Demirdogen

Journal of Educational Psychology

Michael Neubrand

Darío Luis Banegas

Doç. Dr. Yasemin Gödek

Eric Camburn , Deborah Ball

Teacher Development

Sinem Gençer

wandee Kasemsu

Marilena Petrou

The Normal Lights

Florisa Simeon

IJESRT Journal

Mourat Tchoshanov

Teaching and Teacher Education

robert bullough

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

Ahmad Mudzakir

Maher Hashweh

Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics

Nooreiny Maarof

Kirsten Mahoney

International Journal of Science Education

Vanessa Kind

International Journal of Innovative Research and Development

PRINCE DUKU

imran Tufail

YILMAZ SOYSAL (PhD) , Y. Soysal

Technium Social Sciences Journal

Williza Cordova

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We're celebrating 50 years of transforming education across the country!

COVID-19 Updates: Visit our Learning Goes On site for news and resources for supporting educators, families, policymakers and advocates.

- Resource Center

Pedagogical Content Knowledge- What Matters Most in the Professional Learning of Content Teachers in Classrooms with Diverse Student Populations

• By Adela Solís, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • August 2009

In its pursuit of equity in education, the Intercultural Development Research Association continually provides many professional learning opportunities to teachers of diverse student populations. These represent an important part of IDRA efforts to increase teaching quality and equity inside today’s classrooms. IDRA president Dr. María “Cuca” Robledo Montecel describes this major reform in a framework for quality education, the Quality Schools Action Framework ( 2005 ).

Through several of IDRA’s professional development models, like Math Smart! , Science Smart! and Coaching and Mentoring of Novice Teachers , coaching and mentoring are provided to beginning teachers and to other teachers who strive to provide rigorous and relevant content instruction to English language learners and other culturally diverse students. Teachers of mathematics, science and language are particularly looking for support as these are content areas where many students perform poorly on academic tests often due to content teachers’ lack of rigorous and accurate preparation. Dr. Abelardo Villarreal cites teaching quality as a major principle for an evidence-based secondary education plan for English language learners ( 2009 ).

Professional development and teacher preparation research also support the importance of teaching quality and further identify content specific pedagogy as a key ingredient in teaching quality. This is the first of two related articles. It provides insight from research pertinent to professional learning, theory of diverse pedagogy, content learning, and how these can be integrated into a professional development program for teachers in a multicultural, equity-conscious society.

Focus on Teacher Professional Learning in Content Areas

Many government-initiated school reform programs in the United States focus substantially on the professional learning of teachers (see Hassel, 1999 ; NPEAT, 2003). Content area teaching experts similarly seek the best knowledge on how to prepare teachers of adolescents to meet the demands unique to their specialization (Borko, 2004; Shanahan and Shanahan, 2008). The paucity of research on content teaching in a diverse classroom as a pressing issue in teacher education has received special focus in the United States as well as in other countries, like the Netherlands, Britain and Australia.

Not surprisingly, this issue has emerged with even greater import as a result of low student achievement and the prevailing student achievement gaps in the critical subject areas of reading, writing, mathematics and science. The answers to the critical question of how to most effectively reach students clearly tell us this: teaching matters, as does the learning of teachers. Furthermore, fast demographic changes require that content teaching reflect diverse pedagogy-specific teaching and learning practices.

Importance of Professional Learning through an Equity Lens

If all content teachers are formally trained, why is professional learning still necessary? Both research and first-hand observations of teaching and learning dynamics have discovered that what a teacher knows and what he or she does and believes have a major influence on how students learn. Most importantly, we know that these are dynamic behaviors and dispositions that evolve over time and include the right types of content-specific skills often referred to as pedagogical content knowledge , or PCK (Gess-Newsome and Lederman, 2001).

What is Pedagogical Content Knowledge?

The concept of pedagogical content knowledge is not new. The term gained renewed emphasis with Lee Shulman (1986), a teacher education researcher who was interested in expanding and improving knowledge on teaching and teacher preparation that, in his view, ignored questions dealing with the content of the lessons taught . He argued that developing general pedagogical skills was insufficient for preparing content teachers as was education that stressed only content knowledge. In his view, the key to distinguishing the knowledge base of teaching rested at the intersection of content and pedagogy ( Shulman, 1986 ).

Shulman defined pedagogical content knowledge as teachers’ interpretations and transformations of subject-matter knowledge in the context of facilitating student learning. He further proposed several key elements of pedagogical content knowledge: (1) knowledge of representations of subject matter (content knowledge); (2) understanding of students’ conceptions of the subject and the learning and teaching implications that were associated with the specific subject matter; and (3) general pedagogical knowledge (or teaching strategies). To complete what he called the knowledge base for teaching, he included other elements: (4) curriculum knowledge; (5) knowledge of educational contexts; and (6) knowledge of the purposes of education (Shulman, 1987). To this conception of pedagogical content knowledge, others have contributed valuable insights on the importance and relevance of the linguistic and cultural characteristics of a diverse student population.

While other education scholars since the 1990s have expanded and promoted the development of PCK among content teachers through both teacher preparation (pre-service) and professional development (inservice), “valid” research failed to address the issue of linguistically and culturally different students as a mediating variable that should be factored into any study of effective teaching practices. However, proponents of the PCK concept say that there is special value in their work in that it has served to re-focus educators’ attention on the important role of subject matter in educational practice and away from the more generic approach to teacher education that dominated the field since the 1970s (Gess-Newsome and Lederman, 2001). While the specific term, PCK, is just gaining momentum in U.S. literature, we see it addressed in published content standards by professional teaching associations as reviewed in In Time Project (2001) and in a number of content area textbooks, such as Schartz’s Elementary Mathematics Pedagogical Content Knowledge (2008).

Nevertheless, professional development is required in most states and certainly through national legislation, such as the No Child Left Behind Act and its various school-based programs. Certainly, dismal math and science test results have led to intensive scheduling of training for math and science teachers. In-depth planning about the specific type of knowledge and skills these teachers needed is not always evident. Below are a some key findings and implications of pedagogical content knowledge in the teaching literature that can contribute to awareness of the importance of PCK, as contributed by van Driel, Verloop and Vos (1998); Goldston (2004) ; Loughranm, Mulhall and Berry (2004), and others.

Highlights of Key Findings and Principles of Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Definitions.

- Pedagogical content knowledge is a special combination of content and pedagogy that is uniquely constructed by teachers and thus is the “special” form of an educator’s professional knowing and understanding.

- Pedagogical content knowledge also is known as craft knowledge . It comprises integrated knowledge representing teachers’ accumulated wisdom with respect to their teaching practice: pedagogy, students, subject matter, and the curriculum.

- Pedagogical content knowledge must be addressed within the context of a diverse pedagogy.

How PCK is Developed

- Pedagogical content knowledge is deeply rooted in a teacher’s everyday work. However, it is not opposite to theoretical knowledge. It encompasses both theory learned during teacher preparation as well as experiences gained from ongoing schooling activities.

- The development of pedagogical content knowledge is influenced by factors related to the teacher’s personal background and by the context in which he or she works.

- Pedagogical content knowledge is deeply rooted in the experiences and assets of students, their families and communities.

Impact of PCK

- When teaching subject matter, teachers’ actions will be determined to a large extent by the depth of their pedagogical content knowledge, making this an essential component of their ongoing learning.

- Pedagogical content knowledge research links knowledge on teaching with knowledge about learning, a powerful knowledge base on which to build teaching expertise.

Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Core Content Areas

As noted above, PCK illustrates how the subject matter of a particular discipline is transformed for communication with learners. It includes recognition of what makes specific topics difficult to learn, the conceptions students bring to the learning of these concepts, and teaching strategies tailored to this specific teaching situation. To teach all students according to today’s standards, teachers indeed need to understand subject matter deeply and flexibly so they can help students map their own ideas, relate one idea to another, and re-direct their thinking to create powerful learning. Teachers also need to see how ideas connect across fields and to everyday life. These are the building blocks of pedagogical content knowledge.

It is critical, however, that pedagogical content knowledge be subject-specific. What are some examples PCK in the core subject areas of language, science, mathematics and social studies? And how does this knowledge compare with other knowledge that teachers traditionally master? The box on the next page shows a comparative view of teaching standards that demonstrate differences in teaching expectations pertinent to content knowledge, knowledge of general pedagogy, and pedagogical content knowledge ( NBPTS, 1998 ). Standards organized in this manner are a ready-made guide for practitioners to use in directing the specialized learning of their content teachers. Further, this distinction in knowledge bases can serve to assess the overall planning and delivery of content teacher professional development.

Professional Development that Supports Development of PCK

It is not uncommon for professional development leaders to work with schools that have concentrated all of their professional development efforts in only one area, such as subject matter knowledge or with schools that have designed professional development plans around only pedagogical concerns, such as effective instructional techniques. Yet, they have not netted the hoped-for results in student learning as evidenced in poor performance on achievement tests.

PCK theory questions the value of knowing everything about a subject if one does not understand how students learn it or the value of being the very best at instructional strategies if those strategies cannot deliver high quality subject matter knowledge. What is needed instead is to orchestrate teacher learning opportunities that are centered on the specific ways of knowing and doing within a given subject or, on pedagogical content knowledge.

Fortunately, current professional development principles do guide the process of teacher learning in ways that support PCK. We have best practices research that delineates the best overall approach, context, strategies, and content of professional development (NPEAT, 2003; von Frank, 2008 ). Below are eight of several professional development principles that foster actions (or practices) that, when well orchestrated, can result in the solid PCK in all content teachers.

Professional Development Practices Best to Avoid

By implication of the above premises, certain teacher training practices common in some schools would not be useful, and even counterproductive, to efforts to build teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Below are three examples of such practices.

- Workshops that review generic reading skills (the main idea is…), demonstrate only the “fun” aspect of games (great scavenger hunts), or lead teachers to recipe-style learning (following the textbook or instructional guide).

- Training on differentiated instruction that addresses developmental level (age and grade) but without reference to specific disciplines.

- Sessions focusing on content learning left to content experts whose focus and interest is mere subject matter.

At the heart of effective content teaching is the teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. If we are to improve the quality of teaching and learning in critical core content areas, we need to resist some old traditions in professional learning. Instead, we should acknowledge and expand the insights of experts who develop competence in subject matter teaching. We should additionally commit to high quality professional development targeted to develop this expertise. When we do this, we support the growth of the teacher as a person and a professional who can expertly lead a student to academic success. Concurrently, we will contribute to the realization of the goals and priorities of the classroom and the school system as a whole.

A follow-up article in a future issue of the IDRA Newsletter will address how generic knowledge about PCK juxtaposed with knowledge of diverse pedagogy is applied in a mentor training program that addresses the needs of teachers in classrooms with diverse student populations.

Borko, H. “ Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain ,” Educational Researcher (2004). Vol. 33, No. 8, 3-15.

Gess-Newsome, J., and N.G. Lederman. “Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge: The Construct and its Implications for Science Education,” Contemporary Trends and Issues in Science Education (2001).

Goldston, M. “ The Highly Qualified Teacher and Pedagogical Content Knowledge ,” 2004 Focus Group Background Papers (Arlington, Va.: The National Congress on Science Education, 2004).

Hassel, E. Professional Development: Learning from the Best: A Toolkit for Schools and Districts Based on the National Awards Program for Model Professional Development (Oakbrook, Ill.: North Central Regional Education Laboratory, 1999).

Hernández Sheets, R. Diversity Pedagogy – Examining the Role of Culture in the Teaching-Learning Process (Boston, Mass.: Pearson Education, Inc., 2005).

InTime (Integrating New Teaching into the Methods of Education) Project. Teachers’ In-depth Content Knowledge (Component of Technology as Facilitator of Quality Education Model) (Cedar Falls, Iowa: University of Northern Iowa, 2001).

Loughran, J., and P. Mulhall, A. Berry. “In Search of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science: Developing Ways of Articulating and Documenting Professional Practice,” Journal of Research in Science Teaching (Australia: Monash University, 2004). Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 370-391.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. Early Childhood/Generalist Standards (Arlington, Va.: NBPTS, 1998).

National Partnership for Excellence and Accountability in Teaching (NPEAT). “Principles of Effective Professional Development,” Research Brief (Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2003). Vol. 1, No. 15.

Robledo Montecel, M. “ A Quality Schools Action Framework – Framing Systems Change for Student Success ,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, November-December 2005).

Schartz, J.E. Elementary Mathematics Pedagogical Content Knowledge: Powerful Ideas for Teachers (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Allyn & Bacon, 2008).

Shanahan, C., and T. Shanahan. “ Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Re-thinking Content Literacy ,” Harvard Educational Review (2008).

Shulman, L.S. “ Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching ,” Educational Researcher (1986). 15 (2), 4-14.

Shulman, L.S. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform,” Harvard Educational Review (1987). 57, 1-22.

Van Driel, J.H., and N. Verloop, W. de Vos. “Developing Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge,” Journal of Research in Science Teaching (1998). 35(6), 673-695.

Villarreal, A. “ Ten Principles that Guide the Development of an Effective Educational Plan for English Language Learners at the Secondary Level – Part II ,” IDRA Newsletter (San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association, February 2009).

Von Frank, V. Professional Learning for School Leaders (Oxford, Ohio: National Staff Development Council, 2008).

Adela Solís, Ph.D., is a senior education associate in IDRA’s Field Services. Comments and questions may be directed to her via e-mail at [email protected] .

[©2009, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the August 2009 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]

- Classnotes Podcast

Explore IDRA

- Data Dashboards & Maps

- Educator & Student Support

- Families & Communities

- IDRA Valued Youth Partnership

- IDRA VisonCoders

- IDRA Youth Leadership Now

- Policy, Advocacy & Community Engagement

- Publications & Tools

- SEEN School Resource Hub

- SEEN - Southern Education Equity Network

- Semillitas de Aprendizaje

- YouTube Channel

- Early Childhood Bilingual Curriculum

- IDRA Newsletter

- IDRA Social Media

- Southern Education Equity Network

- School Resource Hub – Lesson Plans

5815 Callaghan Road, Suite 101 San Antonio, TX 78228

Phone: 210-444-1710 Fax: 210-444-1714

© 2024 Intercultural Development Research Association

- Financial Aid

- Campus Life

- Support UNI

- UNI Bookstore

- Rod Library

- Careers at UNI

- The Model (Graphic Version)

- Packaged Intime CDs and Customized CDs or DVDs

- Using Teaching Standards to Improve Student Learning DVD

- Democracy in the Classroom: Developing Character and Citizenship DVDs

- Intime Evaluator Series DVDs: Volumes 1-5

- Be a Buddy, Not a Bully! DVD & Curriculum Guide

- Initial Supporting Paper and Bibliography

- INTIME Goals and their Importance

- INTIME Resources

- INTIME Publicity

- INTIME Production and Creators

- INTIME Evaluation Overview

Teacher's In-Depth Content Knowledge

To teach all students according to today’s standards, teachers need to understand subject matter deeply and flexibly so they can help students create useful cognitive maps, relate one idea to another, and address misconceptions. Teachers need to see how ideas connect across fields and to everyday life. This kind of understanding provides a foundation for pedagogical content knowledge that enables teachers to make ideas accessible to others (Shulman, 1987).

Shulman (1986) introduced the phrase pedagogical content knowledge and sparked a whole new wave of scholarly articles on teachers' knowledge of their subject matter and the importance of this knowledge for successful teaching. In Shulman's theoretical framework, teachers need to master two types of knowledge: (a) content, also known as "deep" knowledge of the subject itself, and (b) knowledge of the curricular development. Content knowledge encompasses what Bruner (as cited in Shulman, 1992) called the "structure of knowledge"–the theories, principles, and concepts of a particular discipline. Especially important is content knowledge that deals with the teaching process, including the most useful forms of representing and communicating content and how students best learn the specific concepts and topics of a subject. "If beginning teachers are to be successful, they must wrestle simultaneously with issues of pedagogical content (or knowledge) as well as general pedagogy (or generic teaching principles)" (Grossman, as cited in Ornstein, Thomas, & Lasley, 2000, p. 508).

Shulman (1986, 1987, 1992) created a Model of Pedagogical Reasoning, which comprises a cycle of several activities that a teacher should complete for good teaching: comprehension, transformation, instruction, evaluation, reflection, and new comprehension.

Comprehension. To teach is to first understand purposes, subject matter structures, and ideas within and outside the discipline. Teachers need to understand what they teach and, when possible, to understand it in several ways. Comprehension of purpose is very important. We engage in teaching to achieve the following educational purposes:

To help students gain literacy

To enable students to use and enjoy their learning experiences

To enhance students’ responsibility to become caring people

To teach students to believe and respect others, to contribute to the well-being of their community

To give students the opportunity to learn how to inquire and discover new information

To help students develop broader understandings of new information

To help students develop the skills and values they will need to function in a free and just society (Shulman, 1992)

Transformation. The key to distinguishing the knowledge base of teaching lies at the intersection of content and pedagogy in the teacher’s capacity to transform content knowledge into forms that are pedagogically powerful and yet adaptive to the variety of student abilities and backgrounds. Comprehended ideas must be transformed in some manner if they are to be taught. Transformations require some combination or ordering of the following processes:

Preparation (of the given text material), which includes the process of critical interpretation

- Representation of the ideas in the form of new analogies and metaphors (Teachers' knowledge, including the way they speak about teaching, not only includes references to what teachers “should” do, it also includes presenting the material by using figurative language and metaphors [Glatthorn, 1990].)

- Instructional selections from among an array of teaching methods and models

- Adaptation of student materials and activities to reflect the characteristics of student learning styles

- Tailoring the adaptations to the specific students in the classroom

Glatthorn (1990) described this as the process of fitting the represented material to the characteristics of the students. The teacher must consider the relevant aspects of students’ ability, gender, language, culture, motivations, or prior knowledge and skills that will affect their responses to different forms of presentations and representations.

Instruction. Comprising the variety of teaching acts, instruction includes many of the most crucial aspects of pedagogy: management, presentations, interactions, group work, discipline, humor, questioning, and discovery and inquiry instruction.

Evaluation. Teachers need to think about testing and evaluation as an extension of instruction, not as separate from the instructional process. The evaluation process includes checking for understanding and misunderstanding during interactive teaching as well as testing students’ understanding at the end of lessons or units. It also involves evaluating one’s own performance and adjusting for different circumstances.

Reflection. This process includes reviewing, reconstructing, reenacting, and critically analyzing one’s own teaching abilities and then grouping these reflected explanations into evidence of changes that need to be made to become a better teacher. This is what a teacher does when he or she looks back at the teaching and learning that has occurred–reconstructs, reenacts, and recaptures the events, the emotions, and the accomplishments. Lucas (as cited in Ornstein et al., 2000) argued that reflection is an important part of professional development. All teachers must learn to observe outcomes and determine the reasons for success or failure. Through reflection, teachers focus on their concerns, come to better understand their own teaching behavior, and help themselves or colleagues improve as teachers. Through reflective practices in a group setting, teachers learn to listen carefully to each other, which also gives them insight into their own work (Ornstein et al., 2000).

New Comprehension . Through acts of teaching that are "reasoned" and "reasonable," the teacher achieves new comprehension of the educational purposes, the subjects taught, the students, and the processes of pedagogy themselves (Brodkey, 1986).

Students (the teacher’s audience) are another important element for the teacher to consider while using a pedagogical model. A skillful teacher figures out what students know and believe about a topic and how learners are likely to “hook into” new ideas. Teaching in ways that connect with students also requires an understanding of differences that may arise from culture, family experiences, developed intelligences, and approaches to learning. Teachers need to build a foundation of pedagogical learner knowledge (Grimmet & Mackinnon, 1992).

To help all students learn, teachers need several kinds of knowledge about learning. They need to think about what it means to learn different kinds of material for different purposes and how to decide which kinds of learning are most necessary in different contexts. Teachers must be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different learners and must have the knowledge to work with students who have specific learning disabilities or needs. Teachers need to know about curriculum resources and technologies to connect their students with sources of information and knowledge that allow them to explore ideas, acquire and synthesize information, and frame and solve problems. And teachers need to know about collaboration–how to structure interactions among students so that more powerful shared learning can occur; how to collaborate with other teachers; and how to work with parents to learn more about their children and to shape supportive experiences at school and home (Shulman, 1992).

Acquiring this sophisticated knowledge and developing a practice that is different from what teachers themselves experienced as students, requires learning opportunities for teachers that are more powerful than simply reading and talking about new pedagogical ideas (Ball & Cohen, 1996). Teachers learn best by studying, by doing and reflecting, by collaborating with other teachers, by looking closely at students and their work, and by sharing what they see.

This kind of learning cannot occur in college classrooms divorced from practice or in school classrooms divorced from knowledge about how to interpret practice. Good settings for teacher learning–in both colleges and schools–provide lots of opportunities for research and inquiry, for trying and testing, for talking about and evaluating the results of learning and teaching. The combination of theory and practice (Miller & Silvernail, 1994) occurs most productively when questions arise in the context of real students and work in progress and where research and disciplined inquiry are also at hand.

Darling-Hammond (1994) noted the following:

Better settings for such learning are appearing. More than 300 schools of education in the United States have created programs that extend beyond the traditional four-year bachelor’s degree program, providing both education and subject-matter course work that is integrated with clinical training in schools. Some are one or two year graduate programs for recent graduates or midcareer recruits. (p. 6)

Others are five-year models for prospective teachers who enter teacher education as undergraduates. In either case, the fifth year allows students to focus exclusively on the task of preparing to teach, with year-long, school-based internships linked to course work on learning and teaching. Studies have found that graduates of these extended programs are more satisfied with their preparation, and their colleagues, principals, and cooperating teachers view them as better prepared.

Both university and school faculty plan and teach in these programs. Beginning teachers get a more coherent learning experience when they are organized in teams with these faculty and with one another. Senior teachers deepen their knowledge by serving as mentors, adjunct faculty, co-researchers and teacher leaders. Thus, these schools can help create the rub between theory and practice, while creating more professional roles for teachers and constructing knowledge that is more useful for both practice and ongoing theory building(Darling-Hammond, 1994).

If teachers investigate the effects of their teaching on students’ learning and if they read about what others have learned, they become sensitive to variation and more aware of what works for what purposes and in what situations. Training in inquiry also helps teachers learn how to look at the world from multiple perspectives and to use this knowledge to reach diverse learners.

References

Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1996). Reform by the book: What is--or might be--the role of curriculum materials in teacher learning and instructional reform? Educational Researcher, 25 (9), 6-8.

Brodkey, J. J. (1986). Learning while teaching . Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1994, September). Will 21st-century schools really be different? The Education Digest, 60, 4-8.

Glatthorn, A. A. (1990). Supervisory leadership . New York: Harper Collins.

Grimmet, P., & MacKinnon, A. (1992). Craft knowledge and the education of teachers. In G. Grant (Ed.), Review of research in education 18, pp. 59-74 Washington, DC: AERA.

Miller, L., & Silvernail, D. L. (1994). Wells Junior High School: Evolution of a professional development school. In L. Darling-Hammond (Ed.), Professional development schools: Schools for developing a profession (pp.56-80). New York: Teachers College Press.

Ornstein, A. C., Thomas, J., & Lasley, I. (2000). Strategies for effective teaching . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher , 15 (2), 4-14.

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57 (1), 1-22.

Shulman, L. (1992, September-October). Ways of seeing, ways of knowing, ways of teaching, ways of learning about teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 28 , 393-396

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge and Self-Efficacy Words: 702

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Secondary Level Agricultural Science Words: 1229

- Funds of Knowledge, the Book for Teachers Words: 689

- Pedagogical Theory and Practice and Improving Student Learning Experience Words: 4327

- Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice Words: 1665

- Using a Content Knowledge to Build Meaningful Curriculum Words: 668

- Pedagogical Skills in Elementary School Words: 559

- Personal and Shared Knowledge Words: 1650

- Mathematics Teacher’s Career Goal Words: 905

- E-Government and Knowledge Management Words: 1120

- Different Perceptions in Knowledge Words: 1595

- Knowledge Management in Business Words: 548

- Pre-Service Mathematics Teachers’ Self-Perceptions Words: 1545

- Indigenous Knowledge Mistreatment: A Long Way to Go Words: 3876

Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics

Pedagogical content knowledge has become increasingly important for science teacher education. The delivery of rich educational content to learners in the modern classroom environment demands a profound understanding of the subject matter in question. The history of educations shows that teacher-training courses have been focusing on the teacher’s content knowledge. However, recent developments in teacher education concentrate on pedagogy. For this reason, teachers are required to conduct deep research on pedagogical content knowledge with a view of helping students relate the classroom theories to real-life situations. This approach enables them to connect ideas while addressing mistaken beliefs that occur in everyday life. This study focuses on pedagogical content knowledge with a view of discussing courses that are designed to deepen the preservice understanding of elementary mathematics and pedagogy.

Pedagogical content is seen as the most useful form of representing the most powerful and useful ideas, analogies, illustrations, examples, explanations, and demonstrations to learners. This phenomenon also entails the realization of various teaching methods that improve the understanding of content amongst the students. This undertaking corrects the misconstructions that are developed in the learners’ minds, thereby enabling them to relate theoretical knowledge to real-life situations.

Content knowledge refers to the level of familiarity with a certain subject and its organization in the mind of a teacher. On the other hand, pedagogical knowledge entails the strategies and principles of classroom management and organization in education. Learners need a teacher who has expertise in their subject besides having sufficient pedagogical skills to articulate the content matter. Training programs align the knowledge of the subject to instruction and learning to prepare preservice teachers effectively. It is emphasized that preservice teachers should have knowledge that goes beyond the common understanding of mathematical concepts. Therefore, teacher-training programs should consider improving their mathematics courses that focus on teaching the subject to improve self-efficacy.

Teachers with strong pedagogical content knowledge are confident in the delivery of instruction. Additionally, teachers who are less confident in their ability to teach can affect the development of their knowledge. Various studies have revealed that mixing mathematical and pedagogical tasks enhances mathematics knowledge among preservice teachers. The mastery experiences can develop the acquired subject matter to pedagogical knowledge. This knowledge prepares the teacher to apply the appropriate instructional techniques to deliver the desired content to the students. Besides, numerous researchers have also identified that a relationship exists between teaching efficacy and pedagogical content knowledge. It is also known that content-specific knowledge acquired through pedagogical emphasis significantly increased the self-efficacy levels amongst the instructors. Notably, it enables the preservice teachers to formulate and represent the subject to students in a comprehensible manner.

Furthermore, it enables them to comprehend what makes certain concepts either difficult or easily understood by the children. The best approach to the delivery of instruction to the learners entails teaching known to unknown knowledge. This practice enables the learners to connect known knowledge with the newly taught concepts. Teachers should involve themselves in deliberation, debate, and decision-making on how to teach since it is the best way to develop sufficient pedagogical content knowledge. In this regard, deliberation, debate, and participation in the formulation of decisions improve the teachers’ self-efficacy in content delivery.

Pedagogical content knowledge focuses on improving the skills of teachers to make them science instructors rather than technical experts. Preservice instructors need to articulate the knowledge about the specialization subjects. This position enables them to develop students who have in-depth knowledge about the concepts they learn in class. However, the amount of mathematical knowledge needed to deliver the scientific content to the learners demands the teachers to undergo a variety of courses to improve their resourcefulness. As a result, teachers should frequently review the content knowledge about their subjects of specialization with a view of improving the literacy levels of the students.

The accomplishment of this objective requires the teachers to focus on both mathematical and pedagogical skills. This situation enables the learners to understand concepts both within and outside the subject. Teachers also need mathematical knowledge to acquaint the learners with the necessary skills for not only educational purposes but also application in everyday real-life scenarios. For instance, pedagogical content knowledge helps the teacher encourage the students to be respectful to other people in society besides providing the opportunity to inquire about new information. Most importantly, it enables them to connect the ideologies learned in class to practice.

Today, teacher education has shifted its focus from content to pedagogical knowledge. Teachers are expected to have a professional understanding of the need for improving both literacy and numeracy skills, especially in science subjects. Furthermore, there is a need to link such subjects to actual phenomena in which they are applied. The current world is driven by technological pressure due to increased industrialization, globalization, and information-based factors. Therefore, the professional development of both the curriculum and learners is inevitable if schools have to ensure competence in the labor market.

Preservice teachers can fail to get adequate time to conduct adequate practical lessons with the learners. However, the application of the case-based approach to learning can provide a powerful framework for the delivery of scientific knowledge. This approach entails practices such as collaborative learning and role-play. Therefore, reviewing the classroom cases can allow the preservice teachers to improve the reasoning abilities of the children significantly. However, the accomplishment of this objective also demands the instructors provide the learners with the reflective knowledge that connects theory to practice.

The effective delivery of mathematical knowledge requires the teacher to challenge the learners with some real-life problems together with the specific methods for deriving the desired solution. In this manner, preservice teachers stand a position to know the strengths and weaknesses of the learners. This situation helps them identify learners with special difficulties or needs. Therefore, preservice instructors should use curriculum resources to link their learners to the most appropriate knowledge that provide opportunities for discovering, attaining, and synthesizing new information.

In conclusion, teachers should be encouraged to switch from traditional to the pedagogical content-based knowledge that combines a variety of instructional methods. For instance, they should use methods that utilize the student’s knowledge about the mathematics content as a vehicle to develop a pedagogical framework for realizing, inquiring, and analyzing new information. This practice is seen in some courses such as ‘Teaching Mathematics in Elementary School (330) that offers an opportunity for the students to use a variety of materials for learning. The adoption of pedagogical methods practices helps the teachers integrate subject-specific knowledge into a variety of methods of delivering mathematical instruction. This practice encourages the students to use a range of conceptual models to perform activities that develop new perspectives while demonstrating scientific proficiency, especially in elementary mathematics.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, November 25). Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics. https://studycorgi.com/pedagogical-content-knowledge-in-mathematics/

"Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics." StudyCorgi , 25 Nov. 2020, studycorgi.com/pedagogical-content-knowledge-in-mathematics/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics'. 25 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics." November 25, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/pedagogical-content-knowledge-in-mathematics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Mathematics." November 25, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/pedagogical-content-knowledge-in-mathematics/.