Find anything you save across the site in your account

If ever there was a great example of how the best popular movies come out of a merger of commerce and art, “The Godfather” is it. The movie starts from a trash novel that is generally considered gripping and compulsively readable, though (maybe because movies more than satisfy my appetite for trash) I found it unreadable. You’re told who and what the characters are in a few pungent, punchy sentences, and that’s all they are. You’re briefed on their backgrounds and sex lives in a flashy anecdote or two, and the author moves on, from nugget to nugget. Mario Puzo has a reputation as a good writer, so his potboiler was treated as if it were special, and not in the Irving Wallace-Harold Robbins class, to which, by its itch and hype and juicy roman-à-clef treatment, it plainly belongs. What would this school of fiction do without Porfirio Rubirosa, Judy Garland, James Aubrey, Howard Hughes, and Frank Sinatra? The novel “The Godfather,” financed by Paramount during its writing, features a Sinatra stereotype, and sex and slaughter, and little gobbets of trouble and heartbreak. It’s gripping, maybe, in the same sense that Spiro Agnew’s speeches were a few years back. Francis Ford Coppola, who directed the film, and wrote the script with Puzo, has stayed very close to the book’s greased-lightning sensationalism and yet has made a movie with the spaciousness and strength that popular novels such as Dickens’ used to have. With the slop and sex reduced and the whoremongering guess-who material minimized (“Nino,” who sings with a highball in his hand, has been weeded out), the movie bears little relationship to other adaptations of books of this kind, such as “The Carpetbaggers” and “The Adventurers.” Puzo provided what Coppola needed: a storyteller’s outpouring of incidents and details to choose from, the folklore behind the headlines, heat and immediacy, the richly familiar. And Puzo’s shameless turn-on probably left Coppola looser than if he had been dealing with a better book; he could not have been cramped by worries about how best to convey its style. Puzo, who admits he was out to make money, wrote “below my gifts,” as he puts it, and one must agree. Coppola uses his gifts to reverse the process—to give the public the best a moviemaker can do with this very raw material. Coppola, a young director who has never had a big hit, may have done the movie for money, as he claims—in order to make the pictures he really wants to make, he says—but this picture was made at peak capacity. He has salvaged Puzo’s energy and lent the narrative dignity. Given the circumstances and the rush to complete the film and bring it to market, Coppola has not only done his best but pushed himself farther than he may realize. The movie is on the heroic scale of earlier pictures on broad themes, such as “On the Waterfront,” “From Here to Eternity,” and “The Nun’s Story.” It offers a wide, startlingly vivid view of a Mafia dynasty. The abundance is from the book; the quality of feeling is Coppola’s.

The beginning is set late in the summer of 1945; the film’s roots, however, are in the gangster films of the early thirties. The plot is still about rival gangs murdering each other, but now we see the system of patronage and terror, in which killing is a way of dealing with the competition. We see how the racketeering tribes encroach on each other and why this form of illegal business inevitably erupts in violence. We see the ethnic subculture, based on a split between the men’s conception of their responsibilities—all that they keep dark—and the sunny false Eden in which they try to shelter the women and children. The thirties films indicated some of this, but “The Godfather” gets into it at the primary level, the willingness to be basic and the attempt to understand the basic, to look at it without the usual preconceptions, are what give this picture its epic strength.

The visual scheme is based on the most obvious life-and-death contrasts; the men meet and conduct their business in deep-toned, shuttered rooms, lighted by lamps even in the daytime, and the story moves back and forth between this hidden, nocturnal world and the sunshine that they share with the women and children. The tension is in the meetings in the underworld darkness; one gets the sense that this secret life has its own poetry of fear, more real to the men (and perhaps to the excluded women also) than the sunlight world outside. The dark-and-light contrast is so operatic and so openly symbolic that it perfectly expresses the basic nature of the material. The contrast is integral to the Catholic background of the characters: innocence versus knowledge—knowledge in this sense being the same as guilt. It works as a visual style, because the Goyaesque shadings of dark brown into black in the interiors suggest (no matter how irrationally) an earlier period of history, while the sunny, soft-edge garden scenes have their own calendar-pretty pastness. Nino Rota’s score uses old popular songs to cue the varying moods, and at one climactic point swells in a crescendo that is both Italian opera and pure-forties movie music. There are rash, foolish acts in the movie but no acts of individual bravery. The killing, connived at in the darkness, is the secret horror, and it surfaces in one bloody outburst after another. It surfaces so often that after a while it doesn’t surprise us, and the recognition that the killing is an integral part of business policy takes us a long way from the fantasy outlaws of old movies. These gangsters don’t satisfy our adventurous fantasies of disobeying the law; they’re not defiant, they’re furtive and submissive. They are required to be more obedient than we are; they live by taking orders. There is no one on the screen we can identify with—unless we take a fancy to the pearly teeth of one shark in a pool of sharks.

Even when the plot strands go slack, about two-thirds of the way through, and the passage of a few years leaves us in doubt about whether certain actions have been concluded or postponed, the picture doesn’t become softheaded. The direction is tenaciously intelligent. Coppola holds on and pulls it all together. The trash novel is there underneath, but he attempts to draw the patterns out of the particulars. It’s amazing how encompassing the view seems to be—what a sense you get of a broad historical perspective, considering that the span is only from 1945 to the mid-fifties, at which time the Corleone family, already forced by competitive pressures into dealing in narcotics, is moving its base of operations to Las Vegas.

The enormous cast is headed by Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone, the “godfather” of a powerful Sicilian-American clan, with James Caan as his hothead son, Sonny, and Al Pacino as the thoughtful, educated son, Michael. Is Brando marvellous? Yes, he is, but then he often is; he was marvellous a few years ago in “Reflections in a Golden Eye,” and he’s shockingly effective as a working-class sadist in a current film, “The Nightcomers,” though the film itself isn’t worth seeing. The role of Don Vito—a patriarch in his early sixties—allows him to release more of the gentleness that was so seductive and unsettling in his braggart roles. Don Vito could be played as a magnificent old warrior, a noble killer, a handsome bull-patriarch, but Brando manages to debanalize him. It’s typical of Brando’s daring that he doesn’t capitalize on his broken-prow profile and the massive, sculptural head that has become the head of Rodin’s Balzac—he doesn’t play for statuesque nobility. The light, cracked voice comes out of a twisted mouth and clenched teeth; he has the battered face of a devious, combative old man, and a pugnacious thrust to his jaw. The rasp in his voice is particularly effective after Don Vito has been wounded; one almost feels that the bullets cracked it, and wishes it hadn’t been cracked before. Brando interiorizes Don Vito’s power, makes him less physically threatening and deeper , hidden within himself.

Brando’s acting has mellowed in recent years; it is less immediately exciting than it used to be, because there’s not the sudden, violent discharge of emotion. His effects are subtler, less showy, and he gives himself over to the material. He appears to have worked his way beyond the self-parody that was turning him into a comic, and that sometimes left the other performers dangling and laid bare the script. He has not acquired the polish of most famous actors; just the opposite—less mannered as he grows older, he seems to draw directly from life, and from himself. His Don is a primitive sacred monster, and the more powerful because he suggests not the strapping sacred monsters of movies (like Anthony Quinn) but actual ones—those old men who carry never-ending grudges and ancient hatreds inside a frail frame, those monsters who remember minute details of old business deals when they can no longer tie their shoelaces. No one has aged better on camera than Brando; he gradually takes Don Vito to the close of his life, when he moves into the sunshine world, a sleepy monster, near to innocence again. The character is all echoes and shadings, and no noise; his strength is in that armor of quiet. Brando has lent Don Vito some of his own mysterious, courtly reserve: the character is not explained; we simply assent to him and believe that, yes, he could become a king of the underworld. Brando doesn’t dominate the movie, yet he gives the story the legendary presence needed to raise it above gang warfare to archetypal tribal warfare.

Brando isn’t the whole show; James Caan is very fine, and so are Robert Duvall and many others in lesser roles. Don Vito’s sons suggest different aspects of Brando—Caan’s Sonny looks like the muscular young Brando but without the redeeming intuitiveness, while as the heir, Michael, Al Pacino comes to resemble him in manner and voice. Pacino creates a quiet, ominous space around himself; his performance—which is marvellous, too, big yet without ostentation—complements Brando’s. Like Brando in this film; Pacino is simple; you don’t catch him acting, yet he manages to change from a small, fresh-faced, darkly handsome college boy into an underworld lord, becoming more intense, smaller, and more isolated at every step. Coppola doesn’t stress the father-and-son links; they are simply there for us to notice when we will. Michael becomes like his father mostly from the inside, but we also get to see how his father’s face was formed (Michael’s mouth gets crooked and his cheeks jowly, like his father’s, after his jaw has been smashed). Pacino has an unusual gift for conveying the divided spirit of a man whose calculations often go against his inclinations. When Michael, warned that at a certain point he must come out shooting, delays, we are left to sense his mixed feelings. As his calculations will always win out, we can see that he will never be at peace. The director levels with almost everybody in the movie. The women’s complicity in their husbands’ activities is kept ambiguous, but it’s naggingly there—you can’t quite ignore it. And Coppola doesn’t make the subsidiary characters lovable; we look at Clemenza (Richard Castellano) as objectively when he is cooking spaghetti as we do when he is garroting a former associate. Many of the actors (and the incidents) carry the resonances of earlier gangster pictures, so that we almost unconsciously place them in the prehistory of this movie. Castellano, with his resemblance to Al Capone and Edward G. Robinson (plus a vagrant streak of Oscar Levant), belongs in this atmosphere; so does Richard Conte (as Barzini), who appeared in many of the predecessors of this movie, including “House of Strangers,” though perhaps Al Lettieri (as Sollozzo) acts too much like a B-picture hood. And perhaps the director goes off key when Sonny is blasted and blood-spattered at a toll booth; the effect is too garish.

The people dress in character and live in character—with just the gewgaws that seem right for them. The period details are there—a satin pillow, a modernistic apartment-house lobby, a child’s pasted-together greeting to Grandpa—but Coppola doesn’t turn the viewer into a guided tourist, told what to see. Nor does he go in for a lot of closeups, which are the simplest tool for fixing a director’s attitude. Diane Keaton (who plays Michael’s girlfriend) is seen casually; her attractiveness isn’t labored. The only character who is held in frame for us to see exactly as the character looking at her sees her is Apollonia (played by Simonetta Stefanelli), whom Michael falls in love with in Sicily. She is fixed by the camera as a ripe erotic image, because that is what she means to him, and Coppola, not having wasted his resources, can do it in a few frames. In general, he tries not to fix the images. In “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” John Schlesinger showed a messy knocked-over ashtray being picked up in closeup, so that there was nothing to perceive in the shot but the significance of the messiness. Coppola, I think, would have kept the camera on the room in which the woman bent over to retrieve the ashtray, and the messiness would have been just one element among many to be observed—perhaps the curve of her body could have told us much more than the actual picking-up motion. “The Godfather” keeps so much in front of us all the time that we’re never bored (though the picture runs just two minutes short of three hours)—we keep taking things in. This is a heritage from Jean Renoir—this uncoercive, “open” approach to the movie frame. Like Renoir, Coppola lets the spectator roam around in the images, lets a movie breathe, and this is extremely difficult in a period film, in which every detail must be carefully planted. But the details never look planted: you’re a few minutes into the movie before you’re fully conscious that it’s set in the past.

When one considers the different rates at which people read, it’s miraculous that films can ever solve the problem of a pace at which audiences can “read” a film together. A hack director solves the problem of pacing by making only a few points and making those so emphatically that the audience can hardly help getting them (this is why many of the movies from the studio-system days are unspeakably insulting); the tendency of a clever, careless director is to go too fast, assuming that he’s made everything clear when he hasn’t, and leaving the audience behind. When a film has as much novelistic detail as this one, the problem might seem to be almost insuperable. Yet, full as it is, “The Godfather” goes by evenly, so we don’t feel rushed, or restless, either; there’s classic grandeur to the narrative flow. But Coppola’s attitudes are specifically modern—more so than in many films with a more jagged surface. Renoir’s openness is an expression of an almost pagan love of people and landscape; his style is an embrace. Coppola’s openness is a reflection of an exploratory sense of complexity; he doesn’t feel the need to comment on what he shows us, and he doesn’t want to reduce the meanings in a shot by pushing us this way or that. The assumption behind this film is that complexity will engage the audience.

These gangsters like their life style, while we—seeing it from the outside—are appalled. If the movie gangster once did represent, as Robert Warshow suggested in the late forties, “what we want to be and what we are afraid we may become,” if he expressed “that part of the American psyche which rejects the qualities and the demands of modern life, which rejects ‘Americanism’ itself,” that was the attitude of another era. In “The Godfather” we see organized crime as an obscene symbolic extension of free enterprise and government policy, an extension of the worst in America—its feudal ruthlessness. Organized crime is not a rejection of Americanism, it’s what we fear Americanism to be. It’s our nightmare of the American system. When “Americanism” was a form of cheerful bland official optimism, the gangster used to be destroyed at the end of the movie and our feelings resolved. Now the mood of the whole country has darkened, guiltily; nothing is resolved at the end of “The Godfather,” because the family business goes on. Terry Malloy didn’t clean up the docks at the end of “On the Waterfront;” that was a lie. “The Godfather” is popular melodrama, but it expresses a new tragic realism. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

They thought that they’d found the perfect apartment. They weren’t alone .

The world’s oldest temple and the dawn of civilization .

What happened to the whale from “Free Willy.”

It was one of the oldest buildings left downtown. Why not try to save it ?

The religious right’s leading ghostwriter .

After high-school football stars were accused of rape, online vigilantes demanded that justice be served .

A comic strip by Alison Bechdel: the seven-minute semi-sadistic workout .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

EMPIRE ESSAY: The Godfather Review

01 Jan 1972

172 minutes

EMPIRE ESSAY: The Godfather

A son returns from war and doesn't want to get mixed up in the family business: organised crime. When his father is gunned down, however, he commits murder and is inextricably bound by ties of blood, heritage and "honour" to a course of vendetta and power ruthlessly maintained through fear. Eventually he inherits his father's mantle as syndicate big shot and family head, the film ending with a chilling shot of the door closing on his uncomprehending wife as Michael Corleone receives the homage "Godfather".

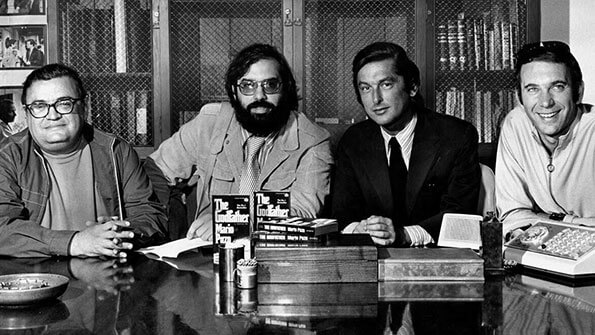

It was the first event movie of the 70s – the one multitudes queued up to see, the one whose dialogue, characters and imagery instantly became ingrained in the collective consciousness. It made stars of Al Pacino and James Caan , and won Oscars for Picture, Screenplay and Marlon Brando , in a triumphant comeback. Shortly after its premiere in 1972, Variety reported, " The Godfather is an historic smash of unprecedented proportions". At the time the director, Francis Ford Coppola , was holed up in a hotel writing the screenplay for The Great Gatsby , a job he took to relieve his financial problems because he believed in his movie. He had only been given the film after a lengthy wish-list of veterans including Otto Preminger, Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann and Franklin Schaffner turned it down. He perked up when Frank Capra wrote to him, claiming it was, " Out of this world. I cheered inwardly at scene after scene."

People are still cheering scene after scene in one of the greatest American films ever made, and committing chunks of dialogue to memory — like the goons in TV's The Sopranos who adore Godfather impersonations, and businessmen like Tom Hanks ' bookseller in You've Got Mail who explains to Meg Ryan that The Godfather is the font of all wisdom for the modern man.

Coppola can be credited with laying the groundwork of 70s cinema with his commanding technical engineering and audacious, visceral and stately set-pieces.

Evaluating the story's irresistibility, Mario Puzo's best-selling novel was, the author considered modestly, "A great combination, the family story and a crime story. And also I made them out to be good guys, except they committed murder once in a while". In adapting the book with Puzo, Coppola had a darker, ultimately more profound take: "I looked at it as the story of a king with three sons." It is pulp fiction turned into opera, an epic of gangster patriarchy, of family, of America itself. "I believe in America," are the first words in the film, spoken by the undertaker Bonasera, an immigrant proud of his assimilation and enrichment. But, he says, "for justice, we must go to Don Corleone." Puzo introduced the term 'godfather', now synonymous with crime family bosses. The words Mafia, Cosa Nostra, camorra and the like never occur in the film because Paramount producer Al Ruddy was paid a little visit by Joe Colombo, one of the heads of the real 'five families', and nervously promised the crime syndicate would be referred to in non-Italian terms.

Ironically, real Mafiosi later embraced the film, paying assiduous court to its principals to this day and affecting the language and style of Vito, Michael, Sonny, their lieutenants and soldiers. Original protests by Italian-Americans who deplored being defamed en masse (the Sons Of Italy, The Italian-American Anti-Defamation League and its champion Frank Sinatra , who raised funds to campaign against the film) have been overshadowed ever since the film's release by its popularity within that same ethnic group. Italian immigrants' descendants, whose assimilation and Americanisation has been complete, view with nostalgic yearning the Corleone clan happily pounding down their pasta, celebrating and sorrowing together at the weddings, the baptism, and the inevitable funeral. Such anecdotes, the legends (Brando did stuff his cheeks with cotton, but had resin blobs clipped to his back teeth; Sinatra, universally believed to be the model for crooner Johnny Fontane, did attack Puzo in a restaurant, calling him a "stool-pigeon"), the footnotes (the baby being baptised during the climactic murder binge is Coppola's infant daughter Sofia ), and the postscripts (Brando sending Satcheen Littlefeather to reject his Oscar) are so abundant that there are volumes of Godfather lore and trivia. TV documentaries have been made of the actor's screen tests.

This landmark remains a masterly work, fully deserving of its reputation. Coppola can be credited with laying the groundwork of 70s cinema with his commanding technical engineering and his audacious, visceral and stately set-pieces – the horse's head in the bed, the slaughter of Sonny (which Coppola acknowledges was inspired by Arthur Penn's climax to 1967's Bonnie And Clyde ), the interweaving of the sunny wedding party with Don Corleone's court indoors, the progress of Michael's respectful Sicilian courtship of Apollonia contrasted with Connie and Carlo's explosive domestic life, and, most unforgettably, the dazzling finale of assassinations, carried out against the sacramental rites in which Michael officially assumes the role of godfather. But the film's finest qualities also reveal Coppola's fluency in the classics, from the superior pulp of the 30s, into 40s noir and social dramas; his authoritative grip on an ordered, fastidiously constructed narrative, Dean Tavoularis' richly detailed design, the weight given to a fabulous supporting ensemble ( Robert Duvall , Richard Conte, John Cazale, Castellano, Alex Rocco), Gordon Willis' striking cinematography, Nino Rota's beautifully melodic score.

The one enduring criticism of The Godfather is that it glorifies the Mafia, affection mingled with abhorrence in its expression of the acts and ethos of Vito Corleone and his extended criminal family. The identification — both Coppola's and the audience's —with Pacino's Michael is unreserved. And cold, ruthless, logical Michael is definitely not the "pretty good guy" it amused Puzo to characterise him as.

Time and two more pictures would highlight the despair and nihilism in The Godfather , with its burden of sins accruing beyond redemption. The 1974 sequel, The Godfather Part II (which took six Oscars, including the only one for Best Picture ever awarded to a sequel) is arguably even more compelling in its elaboration of power's corruption into complete moral decay. 1990's flawed Part III sees Michael get his with Shakespearean finality, Heaven finding a way to kill his only joy. The Godfather continues to entice and entrance with its emphatically mythic exploration of family, be it one cursed in blood and ambition.

READ MORE: The 20 Best Moments From The Godfather Trilogy

READ MORE: Francis Ford Coppola On The Godfather At 50: "It Changed My Life So Significantly"

Related Articles

Movies | 14 05 2024

](http://www.empireonline.com/301?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

Movies | 27 05 2014

Movies | 19 05 2014

The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

The Godfather

Essay by brian eggert february 20, 2022.

Myths examine origins and establish traditions, and a rich mythology sustains The Godfather. Since debuting in 1972, writers and viewers have tried to encapsulate what makes the film a watershed moment in cinema history. Based on Mario Puzo’s best-selling gangster epic, the film explores connections between fathers and sons, family bonds and brutal violence, the American Dream and capitalist greed. The story has seeped into our collective consciousness, creating a mystique around the Corleones, an Italian-American crime family, and the dramatized transition of power in their ranks. Our compulsion to keep examining the phenomenon—investigating why the film is so compelling and, in doing so, adding to the overwhelming degree of assessment—only feeds its status in the pantheon of great filmmaking and storytelling. Countless words have been written to analyze director Francis Ford Coppola’s filmmaking techniques, celebrate the incredible performances, chronicle the behind-the-scenes conflict, survey its influence on the gangster genre, and situate the film in historical contexts. And writers will devote many more words to the subject, all in hopes of understanding why it continues to have a lasting impact more than most other films. The persistent fascination with The Godfather and its unchartable reach has ingrained its mythological place in our culture and history.

So how did the film become the stuff of Hollywood legend? Everyone involved in the production, from Puzo to Coppola to actors with minor roles in the cast, has given their account of The Godfather . There’s a legacy of storytelling about the film among those involved—what it was like to watch Marlon Brando work, witness the arrival of Al Pacino, and be on the set while the battle between Paramount Pictures and Coppola exploded. Given its eventual monumental success at the box office and 1973 Oscar ceremony, which ultimately saved Paramount from going under, everyone has an opinion about who did what and where it all started. Everyone wants credit, too. The answer to the question “Who or what is responsible for this masterpiece?” remains a subject of some debate, exaggerated by the desire to give the majority of credit to a single person. Robert Evans, then the head of production at Paramount, is usually named as an integral force behind the camera. Others attribute the film’s success to Coppola, the 32-year-old Hollywood outsider whose singular vision, and willingness to fight for that vision, shaped the resulting three-hour film. But pour over any number of books and articles about The Godfather , and so many details remain unclarified, occasionally misrepresented, and often disputed by those involved. Historians and critics have taken down conflicting accounts from the principal parties and witnesses, leaving viewers without a clear picture, catapulting the film into the realm of myth.

The exhaustive accounts of the film’s development from page to screen might threaten to overshadow another film, except The Godfather also lends itself to layered textual and thematic analyses. It’s not a classically told story, after all, and it’s easy to overlook how unconventional Coppola’s approach was considered at the time, given its high ranking today on many lists of the greatest films ever made (AFI, BFI, et al.). The novelty of its aesthetic in 1972 has been taken for granted in the subsequent decades. Though it comes out of the venerable gangster movie tradition, it deviates from the classical template established during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Such films dramatized Prohibition-era controversies and created thin allusions to figures such as Al Capone. A long list of gangster classics from the early sound era— The Public Enemy and Little Caesar (both in 1931), Scarface (1932), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), and The Roaring Twenties (1939) among them—solidified the genre with sensationalized stories ripped from the headlines, featuring larger-than-life performances from James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, and George Raft. The genre resurfaced in postwar years, extended by film noir, when gangsters became less ethnically specific (Caucasian but not Italian) and concentrated on their warped psychology, such as Cagney’s mad robber in White Heat (1949). There would be few innovative leaps in the genre in the decades to follow. Like Westerns or swashbucklers, the gangster movie became another form of studio programmer: predictable, safe, and easy to sell.

Coppola should be credited for keeping one foot of The Godfather in traditional motifs and another foot outside them. He stood at the front of New Hollywood’s line of young upstarts—including Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Brian De Palma—who trained at schools like USC and UCLA during the 1960s. Movie brats all, they set out to revitalize Hollywood by working within studios to overcome the stodgy and safe products of the era. In his twenties, Coppola started out making skin flicks for experience before advancing into B-grade horror ( Dementia 13 , 1963), a maligned musical ( Finian’s Rainbow , 1968), and a road movie ( The Rain People , 1969). Coppola foundationalized his rebellious spirit with American Zoetrope in 1969, his San Francisco-based production company founded to give young film artists the freedom to experiment with the medium. Their first production, George Lucas’ THX 1138 (1971), an artfully conceived commercial flop, signaled the company’s ongoing struggle to remain in the black. Coppola needed the occasional studio job to pay the bills—and keep the sheriff from locking the doors, according to Coppola in an oft-told story. He took a studio gig co-writing Patton (1970) alongside Edmund H. North, which not only earned him an Oscar but helped legitimize him in the eyes of studio brass.

Around the same time in 1969, Mario Puzo’s best-selling book, originally titled Mafia , had become an instant phenomenon, selling upwards of nine million copies in the years after its publication. Puzo, a gambling addict and struggling writer, had already published several novels and short stories, some well-reviewed but none of them good sellers. At 45, he was in debt and had grown tired of writing books that no one read, so he decided to follow his editor’s advice and write a Mafia story in a pulpy style proven to sell: larger-than-life characters, sex or violence every few pages, and multiple plotlines to ensnare the reader. Puzo based Don Vito Corleone on his mother, drawing famous lines such as “Make him an offer he can’t refuse” directly from his mother’s mouth. But this is a disputed detail. Some accounts say a mobster used the line, and Puzo’s mother borrowed it. Nevertheless, his eventual manuscript became a sensation, earning Puzo a whopping $410,000 for the paperback rights alone—a record that many attribute to the highly publicized appearance of Mafia enforcer Joseph Valachi before Congress in 1963, watched by millions of Americans on television. Valachi’s testimony—complete with gems like, “You live by the gun and by the knife, and you die by the gun and by the knife”—exposed the general public to their first hint of Italian-American organized crime. Valachi also underscored a certain mythic romanticism about the Mafia that Puzo worked into his book, which weaves a yarn about a Sicilian family who pursues the American Dream by any means at their disposal. For readers who struggled to get what they wanted in life and saw corrupt systems of government and capitalism all around them, the Corleones had a distinct appeal in their self-governance and enforceable moral code.

During the 30-minute wedding sequence, Coppola shows Vito looking out from his window through the blinds at the party. The shots establish the relationship between business and the family, how they are inextricably connected, in that one allows the other to flourish—albeit through a juxtaposition of entrenched family values and criminal acts. But the shots of Vito gazing longingly out at his daughter’s wedding suggest his business dealings have torn him away from his family. The racketeering and coercion that goes on behind closed doors is a means to an end, a way for Vito to “take care of my family.” Though Vito is a ruthless criminal, he also cherishes his loved ones. He would prefer to be savoring his time with them. To illustrate this, Coppola gives us moments of Vito’s adored role in his family—his fathering of Fredo to “be a man,” his strategic advice to Michael, his tender last scene with his grandson. Vito understands the careful balance between his two worlds. But later in the film, after Vito’s near assassination, after Michael rises to become head of the family, the family-business dichotomy becomes unbalanced. The criminal enterprise has consumed Michael, whose ruthless approach to business has sidelined everything else. Of course, Michael’s severity comes as a response to his family’s war with the Five Families over heroin and casinos, which has claimed Sonny and nearly his father. But his scorched earth approach to protecting the family consumes him, leaving his family secondary to the criminal enterprise.

After Coppola read Puzo’s book for the first time, he found himself attracted to the story for several reasons. The portrait of a mob family proved compelling to the Italian-American director, who could imagine what the Corleones must be like in vivid detail. He also recognized the innate classicism that would propel the story into cinematic mythology, given its hints of Shakespeare’s King Lear , complete with three sons as potential successors. More significantly, Puzo’s text as a metaphor for American capitalism attracted Coppola. If the American Dream once represented the average citizen’s freedom to enrich one’s family by getting a fair chance to prosper, it had since been bulldozed by corporate interests, corrupt politicians, and crimes against justice. “The real appeal of the movie was showing family ties in a setting of power,” screenwriter Robert Towne told The New Yorker . “It was really kind of reactionary in that sense—a perverse expression of a desirable and lost cultural tradition, filling people with longing for a family like that, a father who not only knew what was best but, if a guy was giving you a hard time, could have someone kill him.” When the American Way proved faulty, the Corleones had the influence and will to correct it for people like Bonasera. In business, they were self-starters, a paragon of entrepreneurism. But when negotiations failed, gangsters could back their drive for success with the brutality required to ensure it. Americanism was rarely purer in its all-consuming need to conquer, own, and consume ad infinitum .

Puzo’s book attracted Peter Bart initially. A former journalist turned Paramount executive, Bart first optioned Puzo’s story for $12,500 before its publication. Before being selected as Paramount’s production head, Evans also specialized in nabbing literary properties for screen adaptation. But Evans glosses over Bart’s role in discovering Puzo’s book in his 1994 memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture . For Evans, The Godfather was the latest in his line of best-selling literary acquisitions that included Roderick Thorpe’s The Detective , Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby , and Erich Segal’s Love Story —all made into profitable films. Evans even claims he met with Puzo before the book’s publication and agreed to pay the author’s gambling debts in exchange for the film rights, going so far as to give Puzo an office at Paramount to finish his manuscript. But the extent of these claims has since been disputed as Evans trying to make himself appear as the film’s mastermind. Some accounts give Puzo’s publisher or members of the mob credit for keeping the author afloat financially while he researched the book.

Regardless, Evans and Bart approached a long list of directors for the eventual adaptation. The candidates, ranging from Arthur Penn to Costa-Govras, either dismissed the material on moral grounds or, like “Bloody” Sam Peckinpah ( The Wild Bunch , 1969), focused too much on the pulpier aspects and not enough on the multiple dimensions of the narrative. Then, Evans and Bart sought to make the story as authentic as possible by enlisting an Italian-American director, and Coppola’s name came up. Evans recognized that Coppola would be cheap, and what’s more, “He knew the way these men in The Godfather ate their food, kissed each other, talked. He knew the grit.” Then again, Bart has since denied claims that they chose Coppola because of his ethnicity. He told The New Yorker , “The thing was that Francis was not the only Italian-American director I knew but the brightest young director I knew.” Like most aspects of The Godfather , the motivations that led to Coppola’s entry into the project vary, depending on the source. Not only did Bart sell Evans on Coppola by playing up the young director’s Italian heritage in contrast to the predominantly Jewish filmmakers behind The Brotherhood , but he also underscored how, if Evans wanted to make the film, he would have to act fast to undercut Burt Lancaster’s production company from tempting Paramount with a million-dollar offer for the rights.

Not everyone was convinced about Coppola. The director had to sway the film’s producer Al Ruddy in a legendary pitch meeting where Coppola stood atop a table, shouted, and sold his vision of The Godfather . Ruddy compared him to the conman Bill Starbuck in the play The Rainmaker , promising to bring rain in a drought. Unlikely though it may have seemed, Coppola, like Starbuck, made it rain, but only after convincing the studio to spend more than they wanted. Paramount chose to situate the story in a contemporary setting as a money-saving measure. Period costumes and cars would increase the budget significantly, from the intended low-budget production to a significant investment. Paramount was, after all, a struggling studio. “There were eight studios in Hollywood and Paramount was ninth,” Evans wrote in his autobiography. But Coppola convinced them to shift the settings to the late 1940s and 1950s, along with location shooting in New York. It might be tempting to give Paramount praise for trusting in the maverick director and forking out the budgetary dollars for his vision—production costs rose well above the initially estimated $2.5 million—but Evans and others at the studio also mistrusted Coppola, spied on him, and on more than one occasion, tried to get him fired from the production. In Mark Seal’s book about the film, Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli , he discovered the film materialized out of “an unlikely amalgamation of brute force, artistic choice, market necessity, genius, and dumb luck.” Part of what makes The Godfather so mythological is that it ever got made.

As already noted, given how thoroughly The Godfather has saturated pop culture, it’s easy to miss how much of the production was considered unorthodox at the time. Take the cast, headlined by Brando, the down-on-his-luck actor whose erratic behavior and string of box-office disasters made him the odd man out in Hollywood. Puzo always saw Brando in the role and reached out to him well in advance of the production to ask if he would play Don Vito, though the actor turned down the part—at first, anyway. Al Pacino was a veritable unknown performer on the New York stage, appearing only in The Panic in Needle Park (1971) on film. Diane Keaton was best known for a television commercial. At least, James Caan and Robert Duvall had several credits to their name, and Coppola had seen their work on stage and screen. Brando, Pacino, Keaton, Caan, and Duvall always topped Coppola’s wishlist for the leading players, yet Evans and everyone else at Paramount recoiled at his picks. So the studio spent eight months and $400,000 on an elaborate casting call, the most highly publicized and widespread since David O. Selnick spared no expense to find his Scarlett O’Hara for Gone with the Wind (1939). Everyone who was anyone was considered, and many of them auditioned and screen-tested. But after all the rigamarole, Paramount, in time, agreed to the cast that Coppola wanted in the first place. In a story that continues to permeate Hollywood lore, Coppola eventually convinced the studio to cast Brando after recording a screen test—with shoe polish in his hair and tissues in his cheeks—showing how completely the actor disappeared into his role. If the casting process didn’t result in the studio finding a cast they approved of, the coverage helped publicize the upcoming film.

The Godfather’s screenplay, which Puzo started under Bart’s supervision, led to a working partnership between the author and Coppola, who took turns rewriting the other’s revisions. But the screenwriting process never quite ended. Coppola would produce rewrites sometimes the night before shooting, sometimes the same day. The actors improvised as well, creating some of the film’s most memorable and quotable dialogue. Caan invented Sonny’s “bada-bing” out of nowhere when he says, “You got to get them close like this and bada-bing! You blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit.” Today, the phrase Caan introduced into American vernacular has become synonymous with Tony Soprano, the complex personality from HBO’s watershed drama The Sopranos (1999-2007), a similar look into the private lives of gangsters. Playing Clemenza, Richard Castellano added the latter half to the famous line, “Leave the gun, take the cannoli,” supposedly on his wife’s suggestion—to emphasize the practicality of Clemenza putting food on the table for his family. The choice not only became iconic, but it underscores the film’s central theme of chronicling Italian-American families. Among the less fortunate improvisations was Pacino’s leap onto a moving car in the first week of filming, injuring his ankle and putting the production behind schedule.

Coppola’s endless rewriting, sometimes between setups, put the schedule in disarray. As a result, the budget rose over $6 million under Coppola, who insisted on doing things his way. For instance, Coppola wanted reality for the notorious scene where the Hollywood producer—who refuses to cast the Sinatra-esque Johnny Fontaine (Al Martino)—wakes up to a horse head in his bed. So the production designer, Dean Tavoularis, obtained the real thing from a dead horse slated for processing at a dog food company. By all accounts, choices like these worsened tensions between Coppola and the price-conscious studio, and some longtime film-workers on the set turned against their director. Take Aram Avakian, the film’s first editor, who veritably spied on and badmouthed Coppola to the studio. Avakian aligned himself with Jack Ballard, a studio crony sent to New York by Paramount to monitor the production. Avakian suggested that the studio should fire Coppola and make him the replacement (he had a single directing credit). Hearing about this, Coppola fired Avakian before any such coup could occur. Only the scenes shot on location in Sicily, far from anyone loyal to the studio, brought Coppola any pleasure; every other day, Coppola was under enormous pressure and came to work expecting to be fired. But he wouldn’t quit, even if his anxieties were giving him nightmares. And worse, they were not unfounded anxieties. Bart and Evans met with Elia Kazan as a possible replacement, but nothing came of it. The director told film critic Michael Sragow in 1997, “It was just an awful experience. I’m nauseated to think about it.” It’s stories like these that turn The Godfather ’s production into such an against-all-odds account and build the film’s mythical status.

Coppola worked with cinematographer Gordon Willis, nicknamed the “Prince of Darkness,” to create the film’s distinct visual schema of heavy shadows and businesslike sit-downs between Mafia families. But when Evans saw the initial footage, he couldn’t see anything. Willis’ photography had been too dark. The producer couldn’t understand Brando’s mumbled lines, either. The footage and performances were a disaster, according to Evans. The disappointing appearance of the initial dailies contributed to the producers turning on Coppola. Then again, this was Willis and Coppola’s plan. However unified, the director and cinematographer were not immune to conflict either, given the shouting matches that caused them to walk off the set or punch holes into doors. But if brightly colored Doris Day movies were the studio norm, Coppola wanted something different to represent the Corleones, who, on the surface, looked like an average American family. Behind closed doors, darker things were happening. Willis used overhead lighting to give the figures a theatrical quality. This highlighted the contrast between the bright wedding scenes and the darkened office to emphasize further the thematic conflict between light and dark, the exterior and the interior worlds. Indeed, the predominance of interiors implies the safety inside the family and the danger outside that awaits. Note that the assassination attempt of Don Vito occurs outside in the market.

Coppola and Willis instill a classicism into the look of The Godfather as well, which is why it doesn’t look like other films from the 1970s. The filmmaking represents an intricate application and unification of set design, camera placement, and lighting, arranged to make the Corleones look at once like a family but also players in a grand drama. Willis also insisted, whenever possible, on classical tableau shots that put the entire family on display—a family portrait in sfumato shadows and the amber hues of his underexposed film stock. Coppola and Willis’ visual agenda not only conveys a story that feels like history unfolding onscreen but also builds the narrative’s thematic underpinnings about the Mafia as a capitalist enterprise. In his monograph for the British Film Institute, Jon Lewis notes how Coppola stages sit-downs between family members like a corporate negotiation. Vito announces, with the cadence of an executive looking to broker a deal, “I hoped that we could come here and reason together. And as a reasonable man, I’m willing to do whatever’s necessary to find a peaceful solution to these problems.” The tactic makes these tableau scenes feel momentous, giving them the sense of a myth in the making. The same is true of scenes blocked around Michael, who wields a different strategy used by ruthless business people to control the room and subtly influence others. Michael isn’t his father’s outwardly humble businessman; he’s an unforgiving tactician bent on taking over the competition.

The film’s strategic slow release into theaters, compounded by exultant praise from nearly every prominent critic from Variety to Pauline Kael to Vincent Canby, resulted in a major box-office success for Paramount. The film opened in March and remained in theaters for much of 1972, earning upwards of $250 million worldwide. The Godfather was credited with not only saving the studio but saving the struggling film industry by reminding everyone that art and commerce could work in unison. David Lean, director of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), wrote Coppola and told him, “Your film is a real shot in the arm for anyone who loves our medium.” The rarity of The Godfather is that, even though Coppola was a director-for-hire at the outset, it became a blend of uncompromising artistry and commercial success. “A work of art that is also a blockbuster,” as Seal described it in his book. Kael wrote something similar: “If there was ever a great example of how the best popular movies come out as a merger of commerce and art, The Godfather it is.” The film’s triumph continued into 1973 on Oscar night. Nominated for ten Academy Awards, The Godfather did not win the most awards that night; Bob Fosse’s Cabaret won eight statues. But The Godfather won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for Puzo and Coppola, and Best Actor for Brando. The accolades continued for years to come. In 1998, the American Film Institute ushered in the new millennium with a list of the 100 greatest films of all time. The Godfather came in third after Casablanca (1942) and the list’s highest-ranked Citizen Kane (1941). When they reordered the list in 2007, it moved up a spot ahead of Casablanca .

Beyond money and awards, the film turned out iconic performances and catapulted the careers of Pacino, Keaton, and many others; reignited Brando’s reputation; and turned Coppola into Paramount’s golden child for the remainder of the 1970s. They quickly signed the director to two sequels, gave him the freedom to make The Conversation before The Godfather Part II (both in 1974) , and earned him enough clout to finance another passion project with United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979). And The Godfather has sustained Coppola’s legend and career in the decades since. He continues to revisit the trilogy—a seemingly endless wellspring of financial opportunity with new restorations, home video releases, alternate cuts, and anniversaries. Sometimes, he seems compelled by his artistic desire; other times, he’s obligated by Paramount to revisit their enduring cash cow: the made-for-TV chronological cut, the 2018 “Coppola Restoration” consisting of a new audio and visual cleanup, and The Death of Michael Corleone in 2020 to give his underrated Part III another shot. In a stroke of irony, Coppola’s film decrying the dangers and corruptibility of capitalism has been his most enduring financial reservoir. And each time Coppola returns to it, The Godfather and its sequels create a renewed interest among moviegoers through this wide array of cuts and visual presentations. Upon the time of this essay, the film celebrates its 50th anniversary, prompting a new 4K restoration, theatrical rerelease, and physical media boxed set.

Moreover, The Godfather redefined the audience’s understanding of screen gangsters, established by classical Hollywood archetypes. Although the broad descriptions of organized crime explored by studios such as Warner Bros. in the ’30s and ’40s portrayed sensational violence with a moralizing message demanded by the Production Code, it’s easier to watch The Godfather and find the Corleone’s world appealing. Vito controls a small empire from his living room, and for people who feel powerless in their everyday lives, that’s a very attractive notion. Coppola admitted, “People love to read about an organization that’s really going to take care of us… When the courts fail you and the whole American system fails you, you can go to Don Corleone and get justice.” In his critical biography about Coppola, Peter Cowie notes that the Don’s “dignified” and “courtly behavior” tends to romanticize the character, ignoring the real-life violence and uncouth behavior of Mafia leaders recorded in court hearings. As with many subsequent gangster films, representation is often mistaken as a glamorization of the Mafia’s code of violence.

For a film about Michael destroying his family and straying from his father’s example to keep the business afloat, the idea that anyone could interpret the story as romantic remains curious. Perhaps the scenes detailing Vito’s backstory in Part II lend a romantic, rise-to-power narrative appeal. But the attractive prospect of the Corleone family’s self-empowerment, which is nonetheless marked by violence, ends with Vito. He sought to balance his family’s prosperity and his criminal enterprise. Viewers who argue that Part II is the superior film fail to recognize that the original says everything the story needed to say in this regard: The Corleones transform from a family into a business. The second film, albeit another landmark, reinforces the point through further narrative examples and a closer character study, building upon ideas conclusively established in its predecessor. One hesitates to call it redundant because, as it further illustrates that Michael has strayed from his father’s path, it deepens the myth of the Corleones. But there’s a quality about the original that feels singular, whereas the sequels feel innately secondary and tertiary. Indeed, along with the two sequels, countless other films about the Mafia followed The Godfather . But none, including Martin Scorsese’s brilliant inclusions in the genre— Goodfellas , Casino , The Irishman (2019)—boast the same classical themes and iconography that elevate Coppola’s film to the stuff of American myth.

The Godfather feels so essential to American cinema and mythology because it draws from established motifs in a grand tradition. If it feels ingrained into American storytelling, it might be because Puzo based his book on a Western, the only true American genre—1910’s The Heritage of the Desert , by Zane Grey. Readers and moviegoers had become accustomed to rooting for well-meaning outlaws and gunslingers who carved out a place for themselves in the Wild West. The gangster genre, Puzo recognized, was a variation on that theme. Puzo’s material deals in vast imagery and themes, from the baptism sequence that combines Christian motifs with murder and hostile takeover to Michael giving up his immortal soul to beat his competition. Coppola turns the story into an epic about universal generational conflicts that occur in a succession, when the former leader must give up their power for the next in line. Michael’s capitalist mindset and decidedly American way of doing business set aside his father’s Old World approach. Such imposing themes are bolstered by the lore surrounding its unlikely journey to the screen. The blended soup of conflicting accounts and behind-the-scenes drama, all of which has received as much coverage as the film itself, further engrains the film into the status of myth, inspiring a new tradition of storytelling about its production and legacy. Five decades later, The Godfather still resonates with the paradigm shifts from one generation to the next, still influences one filmmaker after another, and continues to be the foundation of a lasting mythology.

(Editor’s Note: This essay was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your generous support, Martha! )

Bibliography:

Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood . Simon and Schuster, 1998.

—. The Godfather Companion: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About All Three Godfather Movies . Harper Perennial, 1990.

Coppola, Francis Ford. The Godfather Notebook . Regan Arts, 2016.

Cowie, Peter. The Godfather Book . Faber & Faber, 1997.

—. Coppola . André Deutsch, 2013.

—. The Godfather: The Official Motion Picture Archives , 2012.

Evans, Robert. The Kid Stays in the Picture: A Notorious Life . Hyperion Books, 1994.

The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration . Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. Paramount Pictures, 2008.

The Godfather Legacy . Dir. Kevin Burns. History Channel and Prometheus Entertainment, 2012.

Jones, Jenny M. The Annotated Godfather (50th Anniversary Edition): The Complete Screenplay, Commentary on Every Scene, Interviews, and Little-Known Facts . Black Dog & Leventhal, 2021.

Lebo, Harlan. The Godfather Legacy . Fireside, 1997.

Puzo, Mario. The Godfather . G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1969.

Seal, Mark. Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of The Godfather . Gallery Books, 2021.

Sragow, Michael. “Godfatherhood.” The New Yorker . 24 March 1997. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/03/24/godfatherhood. Accessed 10 January 2022.

Related Titles

- In Theaters

Recent Reviews

- Beetlejuice Beetlejuice 2 Stars ☆ ☆

- Close Your Eyes 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Look Into My Eyes 2.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- AfrAId 1.5 Stars ☆ ☆

- Patreon Exclusive: Rope 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Good One 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Strange Darling 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Blink Twice 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Alien: Romulus 2.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Skincare 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Sing Sing 3.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Borderlands 1.5 Stars ☆ ☆

- Dìdi 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Cuckoo 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- The Instigators 2 Stars ☆ ☆

Recent Articles

- The Definitives: Goodfellas

- The Definitives: The Spirit of the Beehive

- Interview: Jeff Vande Zande, Author of The Dance of Rotten Sticks

- Reader's Choice: Even Dwarfs Started Small

- The Definitives: Nocturama

- Guest Appearance: KARE 11 - Hidden Gems of Summer

- The Labyrinth of Memory in Chris Marker’s La Jetée

- Reader's Choice: Perfect Days

- The Definitives: Kagemusha

- The Scrappy Independents of Mumblegore

- Israel-Gaza War

- War in Ukraine

- US Election

- US & Canada

- UK Politics

- N. Ireland Politics

- Scotland Politics

- Wales Politics

- Latin America

- Middle East

- In Pictures

- BBC InDepth

- Executive Lounge

- Technology of Business

- Women at the Helm

- Future of Business

- Science & Health

- Artificial Intelligence

- AI v the Mind

- Film & TV

- Art & Design

- Entertainment News

- Destinations

- Australia and Pacific

- Caribbean & Bermuda

- Central America

- North America

- South America

- World’s Table

- Culture & Experiences

- The SpeciaList

- Natural Wonders

- Weather & Science

- Climate Solutions

- Sustainable Business

- Green Living

The Godfather: Have we misunderstood America's greatest film?

Fifty years after its premiere, Francis Ford Coppola's classic gangster movie is still considered one of the greatest artworks made about the US, but have we overlooked a key element, asks Nicholas Barber.

Fancy watching The Godfather? It's an offer that most of us can't refuse. Adapted from Mario Puzo's bestselling novel, Francis Ford Coppola's gangster saga came second in BBC Culture's 2015 critics poll to find the 100 greatest American films , and there aren't many such lists that don't have it in the top 10. Fifty years on from its release in March 1972, it stands as the defining US artwork not just on organised crime, but on immigration, capitalism and corruption. Even people who aren't familiar with the film can recognise Marlon Brando's weary, wheezy Mafia boss, Vito Corleone, and his favourite son Michael, played by Al Pacino. They can also quote or misquote its most memorable lines – including the one at the top of this paragraph. And its aficionados know it off by heart. In You've Got Mail, Tom Hanks cites it as the source of all wisdom. ("What is it about The Godfather?" sighs Meg Ryan.) The characters in The Sopranos are such enthusiasts that they name their strip club Bada Bing! after another of its lines.

More like this:

- The monster who terrifies, 100 years on

- The 1971 western that celebrated male intimacy

- The ancient roots of Catwoman

Still, the fact that The Godfather should be so easily associated with a strip club raises the contentious issue of its female characters. The running time is three hours, and yet, to quote the Chicago Sun-Times' critic, Roger Ebert : "There is little room for women in The Godfather." Some critics have gone further. Molly Haskell wrote in the New York Times in 1997 that "Coppola's film demeans and demotes women outrageously". They have a point. There are no women in The Godfather as ferocious as Michelle Pfeiffer's Elvira Hancock in Scarface (1983), or Kathleen Turner and Anjelica Huston's characters in Prizzi's Honor (1985).

While Vito, Michael and his brothers get to make deals and plan murders, pour drinks and eat Chinese takeaways, the women in their lives are left to hold the baby. The film is, among other things, a movie about hanging with your bros. Or, as David Thomson put it in Esquire magazine in 2021 : "It is a movie about happiness and feeling good. And guys get it. Always have." Providing "the most exultant glimpse of male nature in American film", The Godfather, Thomson writes, revolves around "work, order, and the making of decisions".

But it would be unfair to say that the film itself ignores women, even if the men in it so often do. In fact, Coppola keeps reminding us where the female characters are and how they are feeling. The opening speech is about a girl who has been abused, the closing scene has two women questioning and protesting against Michael's methods. The most disturbingly violent sequence has Vito's pregnant daughter Connie (Talia Shire) being whipped by her husband. And when Hollywood mogul Jack Woltz (John Marley) holds forth about a "young", "innocent" starlet, who "was the greatest piece of ass I've ever had", Coppola positions a maid in the background, forced to stand and listen to his misogynistic rant.

As for the male Corleones' neglect of their wives and sisters, well, let's not forget that The Godfather is set in the 1940s and 1950s. As much as we may enjoy the performances of Shelley Winters in Roger Corman's Bloody Mama (1970) and Madonna in Warren Beatty's Dick Tracy (1990), Coppola rejects the idea that mid-century Mafia women were pistol-packing molls, scheming femme fatales, or matriarchs doted on by a crowd of momma's boys. Instead, he insists, they were more likely to be pushed aside by their sexist men, who were steeped in blood and betrayal. The Godfather isn't a monument to male chauvinism, but a condemnation of it. And it's all too relevant, half a century after its release. When Vito attends an all-male meeting of Mafia bosses, the boardroom table is identical to those in countless photos of cabinet meetings and corporate conferences today.

Cutting off female influence

Besides, even though the men drive the plot in The Godfather, the women are vitally important to it. The bravura opening sequence is set at Connie's wedding banquet in the Corleones' family compound. Vito spends most of it in his shadowy study, fielding entreaties from his supplicants (an old Sicilian wedding tradition, apparently), and the dialogue keeps returning to the subject of masculinity. When Vito's top enforcer, Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana), thanks the boss for his wedding invitation, he offers the bride and groom this faltering blessing: "And I hope that their first child be a masculine child." Michael has a different perspective – at first, anyway. A decorated World War Two veteran, he brings his girlfriend Kay (Diane Keaton) to the wedding, shares the Corleones' darkest secrets with her, and insists on her being included in a family photograph. But the trajectory charted by the film is his arc away from Kay and towards damnation. "[Women] will be saints in heaven while we men burn in hell," says Vito in Puzo's novel, and Coppola seems to agree.

The first time we see Michael and Kay after the wedding, they are on a snowy Christmas shopping spree which could be a scene from a romantic comedy, but when Vito is wounded in a shooting, the real casualty is the couple's closeness. Michael can no longer tell her he loves her while his associates are listening, and he leaves the hotel room where they're having dinner to tend to his father. "I'm with you now," he whispers in Vito's ear.

There is a glimmering chance of redemption when Michael hides out in Sicily and falls for a peasant girl, Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), who dares to challenge him. When he first lays eyes on her, she turns and strides away, and after they are married, she is confident enough to mock him and chide him. Coppola puts her behind the wheel of her husband’s car – literally in the driving seat. Could Michael settle down with a companion who is his trusted equal?

Of course not. Apollonia is killed, and Michael returns to the US and the family business – no longer a smiling, tender war hero, but a reptilian tyrant who orders multiple murders, lies about them to his nearest and dearest, and professes to reject Satan at a baptism while his enemies are gunned down. By this stage, "I hope that their first child be a masculine child," sounds more like a curse than a blessing. Michael also reunites with Kay, but his marriage proposal is no longer the stuff of romantic comedies. While Apollonia was in the driving seat, the tearful Kay is ushered into the back of a chauffeur-driven car. You could easily mistake the scene for a kidnapping.

In Puzo's novel, Kay is willing to accept her place in the Corleone crime syndicate, but the film's famous ending has Michael's study door being closed in her distraught face so that he can strategise with his lieutenants in private. She is separated from him, just as Vito's wife (Morgana King) was all through the film. That's what being a Mafia boss means, it seems: being cut off from female influence.

None of this proves that the film is feminist, exactly: Coppola is too reverential towards its martyred women for that. In a Sight and Sound interview from 1972, reprinted in the current issue, he waxes lyrical about "a kind of feminine, magical quality, dating back to the Virgin Mary or something I picked up in catechism classes, that fascinates me". And it's true that he never paints the female Corleones in shades of grey. Kay, Apollonia and Vito's wife never condone their husbands' crimes, and Connie is banished to an apartment in New York after her wedding. It's as if Coppola can't bear the thought that they might be complicit in the men's nefarious deeds. But his approach in The Godfather doesn't "demean or demote" women so much as it places them on a pedestal.

You wouldn’t want many gangster films to have such angelic female characters. We are lucky to have had Lorraine Bracco as Karen Hill in Goodfellas (1990) and Sharon Stone as Ginger McKenna in Casino (1995), for example, as well as a new wave of female-led mob movies. In 2019's The Kitchen, Melissa McCarthy, Tiffany Haddish and Elisabeth Moss took over their husbands' rackets in late-1970s New York. Jennifer Lopez is due to play Griselda Blanco, a Colombian drug dealer, in The Godmother. And Jennifer Lawrence has signed on to star in Mob Girl as Arlyne Brickman, a gangster turned government witness.

These films may be a necessary corrective to The Godfather, but Coppola put more thought than most male writer-directors into what happens when women are excluded from men's lives. After The Godfather Part II – in which Kay abandons Michael – his next film was his 1979 Vietnam War masterpiece, Apocalypse Now (also featuring Marlon Brando). Again, there are almost no women in it, and, again, the women who are in it are archetypes rather than nuanced characters. But, again, they are clearly on Coppola's mind, in scenes ranging from the Playboy bunnies' calamitous show for the troops, to the killing of "Mr Clean" (Laurence Fishburne) while he is listening to a recording of his mother's voice.

As in The Godfather, the hollow left by absent women has been filled with blood. In the extended "Redux" edit of Apocalypse Now, which Coppola completed in 2001, Martin Sheen's Willard spends a night with a widow (Aurore Clémont) on a French plantation, who tells him: "There are two of you, don't you see? One that kills and one that loves." Just like Michael Corleone in Sicily, he glimpses how life could be if he was one that loves rather than one that kills. But the next morning he returns to his mission on the Stygian river, on a journey away from humanity and into the heart of darkness.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

From 1972: ‘The Godfather’ is a film ‘close to the soul of modern man’

Editor’s note: “The Godfather” was released 50 years ago this month. This review appeared in America on March 25, 1972. The original grammar and style elements are preserved here.

Often films set at some distance lend a perspective to the here and now; they allow us to step back from our everyday skin to see who we really are. Bergman, for example, used a medieval knight in The Seventh Seal (1956) to reveal the crisis of faith in post-Christian Europe, and Robert Gardner, in Dead Birds (1963), used a primitive tribe of warriors in New Guinea to reveal the pathetic madness of a people, who like ourselves, have come to accept war as a normal way of life. And now The Godfather . How remote from actual experience, this world of violence and treachery, and yet how close to the soul of modern man.

With The Godfather , Francis Ford Coppola, at 33 years of age, has become a major new talent among American directors.

The mafiosi , murderers and extortionists all, emerge from the film as believable people, when they might easily have become comic gangsters or monsters. Their world tips wildly from the orbit of normalcy; it is a closed world, where their ghastly brutal work is considered an ordinary way to support a family. In the idyllic Sicily sequence, the quaint customs, the fierce family loyalties and the rigid patriarchal formality have a rustic lovely charm; in the New York underworld they are pathetic anachronisms. Yet it is precisely these grotesque rural customs that humanize the members of the famiglia . They are human in the midst of a sordid world, and they do what they must to survive. That is their way, and perhaps the way of all of us.

Don Vito Corleone, meaning lionhearted, is an aging racketeer whose empire and health both show the stress of old age. Brando brings depth and sensitivity to the part, but because of his long established “star” quality he has taken too much of the prerelease publicity. Al Pacino, as his son Michael, gives a virtuoso performance which should bring him instant recognition. He is an idealistic college graduate, marked for a career in the foreign land outside the mob, but gradually the destructive world of his father overwhelms him in its evil. He matures both in humanity and ruthlessness to become a calculating killer and worthy heir to the Don's empire.

At three hours, The Godfather is by any reasonable standard too long to sustain interest, but most viewers will be sorry to see it end.

With The Godfather , Francis Ford Coppola, at 33 years of age, has become a major new talent among American directors. Two sequences in particular are set pieces of editing and directing, and are even more remarkable because of their different styles. During a baptism at which Michael is godfather, his men plan and execute a series of assassinations designed to consolidate his power over the other famiglie . The ceremony drags on endlessly, but the intercutting of the preparations for the murders builds a palpable tension. The explosion of violence at the end of the sequence snaps the tension; it is almost a relief to end it all despite the horror of the bloodletting.

The second sequence, by contrast, is a tender, loving family portrait of Don Corleone and his infant grandson playing together in the garden of his estate. The Don is weak, but with his grandchild he appears perfectly at peace with himself. At this moment, when he appears most fully human, he dies quietly and gently, alone with his grandchild and his flowers. Alone, each of the two scenes is a cameo of directorial art; together they show Coppola's immense versatility.

Nino Rota, who prepared the music for all of Federico Felliní's great films, blends Italian folk themes and America kitsch of the 194O's into an effective comment on the dramatic action.

Richard A. Blake, S.J., served as managing editor and executive editor of America and director of the Catholic Book Club, as well as America 's regular film reviewer for many decades. He is the author of Afterimage: The Indelible Catholic Imagination of Six American Filmmakers , among other books.

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

- Going to the Movies Words: 838

- Why Movies Are Popular All Over the World Words: 858

- The Lost World Movie Review Words: 603

- Movie Censorship and Ratings in America Words: 8217

- Film Studies: Watching Movies Now and in the Past Words: 605

- Minorities Portraying in Movies Words: 904

- Elements That Make a Movie as a Detailed Recording Words: 1683

- The Mirror (1975) Movie Review Words: 560

- “Freedom Song”: Movie Review Words: 1141

- Movie Review: “Rebel Without a Cause” Words: 606

The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review

Introduction, unity and balance.

The Godfather is a world-famous masterpiece directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1972. According to multiple expert reviews and public opinion, the movie is nearly peerless film-making (Chiang). The film has a marvelous screenplay, flawless cast, excellent camera-work, and mindful composition. The present paper offers an analysis of the movie considering art elements and principles of design. According to the analysis, the film is valued for its unity, balance, and contrast.

The most important element of the movie is the sense of harmony of all its parts. Coppola organized and designed all aspects of composition so that they concord with each other, painting a holistic picture of the criminal world in the middle 1900s. At the same time, all elements create a perfect equilibrium since action scenes are followed by mindful conversations, and the positive sides of being a criminal leader are balanced by the drawbacks. None of the elements seem redundant or out of place, which is vital for the composition to be effective.

The movie is built upon contrasts and controversies, which makes it appealing and stimulating. Contrast is seen everywhere from camera work to composition, making the viewer wonder about the questions asked by the director. For instance, in the opening scene, the camera first captures Nino Rota’s evil eyes and skeleton-like face. However, as the picture zooms out, the viewer sees a meek and balding middle-aged man. This is an excellent example of how Coppola uses contrast even within one scene. On the macro level, the viewer is forced to feel empathy with a criminal leader, which is controversial.

The Godfather is a well-composed movie that emphasizes unity, balance, and contrast. All of the scenes seem in place, which helps to achieve equilibrium in composition. At the same time, the feeling of controversy is promoted throughout the movie by showing the contrasting aspects of the life of a criminal leader.

- Chiang, James. Shot Analysis: The Godfather. Animated Spirit. Web

- Coppola, Francis Ford. The Godfather. Paramount Pictures, 1972.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, February 16). The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review. https://studycorgi.com/the-godfather-by-francis-ford-movie-review/

"The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review." StudyCorgi , 16 Feb. 2022, studycorgi.com/the-godfather-by-francis-ford-movie-review/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review'. 16 February.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review." February 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-godfather-by-francis-ford-movie-review/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review." February 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-godfather-by-francis-ford-movie-review/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review." February 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-godfather-by-francis-ford-movie-review/.

This paper, “The Godfather’ by Francis Ford: Movie Review”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: April 21, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

YOUR FINAL GRADE - GUARANTEED UK Essay Experts

Disclaimer: This essay is provided as an example of work produced by students studying towards a film studies degree, it is not illustrative of the work produced by our in-house experts. Click here for sample essays written by our professional writers.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UKEssays.com.

The Godfather Movie Analysis Film Studies Essay

| ✅ Free Essay | ✅ Film Studies |

| ✅ 1559 words | ✅ 1st Jan 2015 |

Reference this

Get Help With Your Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help! Find out more about our Essay Writing Service

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

Essay Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Assignment Writing Service

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please:

Our academic writing and marking services can help you!

- Find out more about our Essay Writing Service

- Undergraduate 2:2

- 7 day delivery

- Marking Service

- Samples of our Service

- Full Service Portfolio

Related Lectures

Study for free with our range of university lecture notes!

- All Available Lectures

Freelance Writing Jobs

Looking for a flexible role? Do you have a 2:1 degree or higher?

Study Resources

Free resources to assist you with your university studies!

- Dissertation Resources at UKDiss.com

- How to Write an Essay

- Essay Buyers Guide

- Referencing Tools

- Essay Writing Guides

- Masters Writing Guides

The Godfather

by Mario Puzo

Critical Context