Allan Paivio and His Dual Coding Theory

The dual coding theory by Allan Paivio

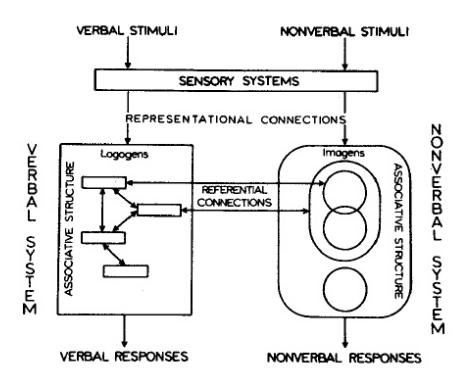

According to Paivio, there are two ways in which a person can extend what they learn with verbal associations and visual images. Dual coding theory states that one can use both visual and verbal data to represent information. Visual and verbal information process differently and on different channels in the human mind, resulting in separate representations for the information in process on each channel.

The brain uses the mental codes corresponding to these representations to organize the incoming information it can store, retrieve, and even modify for later use. It can use both visual and verbal codes to remember information. Additionally, encoding a stimulus in two different ways increases the chance of recalling a memorized item.

There are three different types of processing within dual coding theory: representational, referential processing, and associative processing. In most cases, the subconscious requires all three forms when it comes to a particular task. In other words, a given task may require any or all of the three types of processing.

Paivio also postulates that there are two different types of representative units . The “images” for mental images and “logogens” for verbal entities. The organization of logogens happens in terms of associations and hierarchies. In turn, it organizes images in terms of part-whole relationships .

- Representational processing is when verbal or nonverbal representations directly activate.

- Also, the referential processing when the activation of the verbal system occurs by the non-verbal system or vice versa.

- In addition, associative processing when representations activate within the same system-verbal or non-verbal process.

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Mental Imagery

Dual coding and common coding theories of memory.

The Dual Coding Theory of memory was initially proposed by Paivio (1971) in order to explain the powerful mnemonic effects of imagery that he and others had uncovered, but its implications for cognitive theory go far beyond these findings. It has inspired an enormous amount of controversy and experimental research in psychology, and played a very large role in stimulating the resurgence of scientific and philosophical interest in imagery. Indeed, it has been described as “one of the most influential theories of cognition this [20th] century” (Marks, 1997), and has been fruitfully applied to a wide range of psychological issues, including: thinking processes (Paivio, 1975a); individual differences in thinking styles (Paivio & Harshman, 1983); language understanding (Paivio & Begg, 1981); bilingualism (Paivio & Desrochers, 1980; Paivio, 1986); metaphor (Paivio, 1979); creative thinking (Paivio, 1983b); the observational/theoretical distinction in science (Clark & Paivio, 1989); the psychology of reading and writing (Sadoski & Paivio, 2001); and even the use of visualization to enhance athletic performance (Paivio, 1985; Hall et al. , 1998; Munroe et al. , 2000).

The more intricate details of Dual Coding Theory are beyond our scope here, but the core idea is very simple and intuitive. Paivio proposes that the human mind operates with two distinct classes of mental representation (or “codes”), verbal representations and mental images, and that human memory thus comprises two functionally independent (although interacting) systems or stores, verbal memory and image memory. Imagery potentiates recall of verbal material because when a word evokes an associated image (either spontaneously, or through deliberate effort) two separate but linked memory traces are laid down, one in each of the memory stores. Obviously the chances that a memory will be retained and retrieved are much greater if it is stored in two distinct functional locations rather than in just one.

The laboratory evidence favoring the theory goes well beyond the original context of verbal learning experiments, however. For example, it is claimed that it finds experimental support in studies of memory for pictures (Richardson, 1980 ch.5) and in chronometric studies of mental comparisons of sizes, distances and other dimensions of variation (Paivio, 1975, 1978a, 1978b; Kosslyn, Murphy, Bemesderfer, & Feinstein, 1977; Moyer & Dumais, 1978). Perhaps the most direct experimental support comes from work on the so called selective interference effect, which occurs when a person tries simultaneously to do two mental tasks both of which call for manipulation of representations from the same code (i.e., two verbal tasks, or two imagery/visuo-spatial tasks). In such circumstances, experimental subjects perform measurably more poorly (i.e., slower and/or with more errors) than they do when attempting either task together with one that calls upon the other code (i.e., a verbal and a simultaneous imagery/visuo-spatial task) (Brooks, 1967, 1968; Atwood, 1971; Segal & Fusella, 1971; Baddeley et al., 1975; Janssen, 1976a, 1976b; Baddeley & Lieberman, 1980; Eddy & Glass, 1981; Hampson & Duffy, 1984; Logie & Baddeley, 1990; De Beni & Moè, 2003). Provided one interprets the imagery code primarily as a system for the representation of shape and spatial and spatio-temporal relationships (rather than as specialized for encoding purely visual properties such as color or brightness) these results find a very natural interpretation in Dual Coding terms: two tasks that use the same code interfere strongly with one another because they call upon the same representational and processing resources. [ 1 ]

Nevertheless, the proper interpretation of these experiments (and all the other multifarious relevant laboratory findings) and thus the empirical status of Dual Coding Theory itself, remains controversial. Throughout its history, the theory has been developed and interpreted in the context of opposition to various forms of what have come to be known as common coding theories of memory: Theories committed to explaining all the relevant phenomena in terms of just one type of code (representational format) common to all memories. Thus, to properly understand Dual Coding Theory and the controversies that have surrounded it, it is important to be aware that the prevailing conception of the nature of this common code have changed quite radically over the course of the dual coding versus common coding controversy.

It is also important to distinguish the dual/common coding debate from the better known (at least to philosophers), and ongoing, analog versus propositional debate about imagery, which arose a few years later, in the early 1970s (and will be covered in section 4.4 ). Although these two controversies did become very entangled, the main points at issue are quite different, and an explicit awareness of this may help us avoid some of the confusions that arose from the entanglement. The analog/propositional debate concerns the nature of imagery itself (to put it very crudely, the analog side thinks mental images are inner pictures, and the propositional side think they are inner descriptions), whereas the dual/common coding debate concerns the functional role played by imagery in the cognitive processes of memory and thought. It may be true that that, amongst cognitive scientists, Dual Coding Theory is most often associated with an analog conception of imagery, and common coding is associated with the propositional conception. However, given that Paivio conceives of his verbal code to be embodied as natural language, inner speech, there seems to be no reason to think that it is incoherent to combine a propositional view of imagery with a form of Dual Coding Theory, as Baylor (1972) and Kieras (1978) have proposed. There also appear to be no prima facie reasons to think that the enactive theory of imagery (see §4.5.1 of the main entry ) might be inconsistent with Dual Coding. Furthermore, although perhaps no contemporary theorists combine an analog theory of imagery with a common coding theory of memory, it is arguable that this view was implicit in many of the cognitive theories of former times. For instance, Empiricist philosophers such as Berkeley and Hume (and, very arguably, Aristotle) thought of images as being picture-like ( analog ), and held that all memories (indeed, all mental contents, all ideas ) are images of some sort ( common code ) (see §2.3 Images as Ideas in Modern Philosophy ).

When Paivio initially developed Dual Coding Theory in the 1960s, however, psychological thinking was still dominated by neo-Behaviorism, and the prevailing view was that human memory (where it goes beyond the operant or classical conditioning also seen in animals) depends entirely on words, on inner or subvocal speech in one's native tongue: the common code was taken to be a verbal code. This, however, was soon to change. In the very same era that Paivio's ideas were becoming influential, rapid developments in psycholinguistics, the influence of Artificial Intelligence research, and the rise of the computational information processing approach to cognition were profoundly affecting psychological conceptions of mental representation. Although mainstream memory researchers still mostly focused on memory for verbal material, many came to think of this as encoded in the mind in an abstract format analogous to the “deep structures” of Chomskian linguistic theory or the nested data structures of programming languages such as LISP (Collins & Quillian, 1969; Anderson & Bower, 1973). Thus, by the mid 1970s a very different form of common coding theory had become prevalent. Computationally oriented psychologists began to think of memories as being stored as what they called “propositional representations”, or just “propositions”.

It is important to be aware that this use of the word ‘proposition’ differs, subtly but significantly, from the well established philosophical use of the term, whereby propositions are distinguished sharply from representations (mental or otherwise), and are considered instead to be the underlying, entirely abstract meanings (truths or falsehoods) that representations (such as sentences) may express (Gale, 1967). Thus, following the very influential work of Fodor (1975), philosophers expounding computational theories of mind have usually preferred to talk about “sentential” rather than “propositional” representations, with the understanding that the relevant sentences are to be thought of as expressed not in English (or any other natural, spoken, language) but in mentalese , a computational “language of thought” that is (hypothetically) built into the brain, somewhat as a computer's machine code is built into its CPU. But although it seems to capture their intentions quite well, this philosophical terminology is not widely used by psychologists. In what follows, the philosophical mentalese terminology will generally be favored, but readers should be aware that most of the psychological authors discussed in fact speak of propositional representations.

It is very arguable that the “propositional” common coding theory of memory is more elegant and parsimonious than Dual Coding Theory; certainly it coheres more readily with the broadly computational conception to the mind that remains dominant in cognitive science. Paivio argues, however, that parsimony in terms of representational formats is bought at the cost of a need to posit more types of cognitive processes. He also makes a strong case that Dual Coding Theory has the advantage in its ability to account for the broad range of empirical evidence. The theory has stood up well over the decades both to vigorous conceptual criticism and to many attempted experimental refutations, and Paivio has continued to develop, elaborate, and defend it, periodically reviewing the relevant experimental literature (Paivio, 1971, 1977, 1983a, 1986, 1991a, 1995, 2007; Paivio & Begg, 1981; Sadoski & Paivio, 2001 – for less partisan reviews see Morris & Hampson, 1983; Thomas, 1987; Richardson, 1980, 1999).

Copyright © 2014 by Nigel J.T. Thomas < nigel @ imagery-imagination . com >

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2016 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Dual Coding Theory: The Complete Guide for Teachers

Dual Coding Theory has been gaining a lot of attention from teachers around the world over the last couple of years, but what exactly is it and how can teachers use it to help their students gain a deeper learning?

What is Dual Coding Theory? Allan Pavio discovered that our memory has two codes (or channels) that deal with visual and verbal stimuli. Whilst it stores them independently, they are linked (linking words to images). These linked memories make retrieval much easier. The word or image stimulates retrieval of the other.

When teachers employ a dual coding mindset to their learning materials, the student’s cognitive load is reduced and their working memory capacity is increased, thus, learning is improved.

Whats is Dual Coding Theory?

Back in 1971, Canadian researcher, Allan Paivio, formulated his dual coding theory. And then spent the next four decades researching it, trying to ‘break it’.

He didn’t manage it.

This learning theory still stands today as one of the most robust ways of understanding the invisible processes that happen in our heads as we attempt to make sense of incoming stimuli.

His most significant discovery was that we have two separate channels that deal with verbal and visual stimuli.

While being independent of each other, they are also able to create what Paivio called “associative connections” between them. So, they are both apart from one another but can cooperate in forming linked pairs of words and images.

By forming such a link, the encoding process is enriched.

It leaves a double memory trace and, in the words of Professor Paul Kirschner , results in “double-barrelled learning” because of the resultant double opportunity of being retrieved by either verbal or visual means.

Dual Coding and Cognitive Load

Encoding, of course, is psychologists’ term for learning and, so, such a powering up of the encoding and retrieval processes deserves teachers’ close attention.

It’s no surprise then that John Sweller — the originator of the related Cognitive Load Theory — concludes that:

“Working memory capacity can be effectively increased, and learning improved, by using a dual-mode presentation.”

( Cognitive Load Theory, 2011, Sweller, Ayres & Kalyuga )

Often, cognitive science brings bad news to students. They are confronted by the facts that learning happens through thinking hard (Coe), that the comforting habit of rereading and highlighting is very inefficient, and that studying one topic at a time is less than optimal.

Dual coding is quite different in that pairing words and images don’t incur any additional cognitive load and also greatly helps retrieval.

It’s a ‘freebie’!

But, as good as this news is, it’s only half the story.

When Paivio found that the two channels worked as separate systems, he also noted that they were also fundamentally different in structure.

Verbal information, you won’t be surprised to learn, is sequential in construction. Words are joined together in “concatenation” as philosopher, Bertrand Russell , described it when comparing the relative merits of text and diagrams in conveying meaning.

Why are Visual Aids Important in the Classroom?

Visual information was defined by Paivio as being synchronous, or simultaneous’ in structure.

These two synonymous terms were used to explain that with diagrams, several, if not all, the elements could be viewed in one go.

Words, by contrast, have to be processed one at a time.

While Paivio noted these important structural differences, he didn’t devote his research to exploring them much further.

Others did, I’m glad to say, and we will shortly meet them and learn what they discovered. But, for now, we’ll stay with Paivio’s studies of the associative links between the two modality systems.

As robust as his findings were over several decades, we ought not to forget that the nature of the content learned by his laboratory subjects was cognitively unchallenging.

Like Ebbinghaus in the century before him, Paivio used simple content in order to discount any element of comprehension messing up his pure work on retrieval.

That’s not how schools work though, they do deal with cognitively challenging content.

The knowledge organizer with its lists of facts —let’s acknowledge it—while a very useful document, hardly represents the apex of schools’ intellectual aspirations.

Instead, different approaches are needed to mesh together such isolated facts into coherent networks and integrated concepts.

The Visual Argument (Larkin and Simon).

That’s where Jill Larkin and Herbert Simon come into the picture.

In 1987, they wrote a paper that developed Paivio’s distinction of sequential and synchronous information structures.

By comparing the time, effort and accuracy involved in understanding concepts communicated in either verbal or visual format, they arrived at what is now called “ The Visual Argument” .

In their study, well-constructed diagrams were judged to be more computationally efficient than text.

Behind this somewhat technical term, lies this reasoning.

Because of the sequential nature of verbal information, each word is addressed one at a time. That, of course, isn’t all that’s entailed. To make sense of each word, they need to relate to others.

Sometimes this is simply the ones directly preceding them. But others may well be further apart in a previous phrase or sentence. Such distances require cognitive effort in searching and connecting in order to make the necessary inferences to make sense of the text as a whole.

Diagrams don’t work that way!

Constituent parts of a diagram are all significant, unlike the words in a piece of text. In addition, these visual elements can be perceived in one go, and not serially.

This is why Paivio described visual information being synchronous or simultaneous in structure. And this is why psychologists argue ( Clark & Lyons 2004 ) that diagrams can be largely understood by using our everyday perception.

Graphics for Learning

Gestalt psychology, for nearly a century, has shown us that we immediately understand that proximity of elements represent commonality, as indeed does inclusion within a border (think Euler and Venn diagrams).

Analogy: Things closer together are more related. People living in the same house are more likely to be related in some way than people in separate houses.

These natural capacities are at play in the reading of diagrams and require considerably less cognitive resources than in reading texts.

The two cognitive, or computational, tasks that are more efficient with diagrams are the reduced need to search for relevant items within sentences and, correspondingly, the easier use of inference because metacognition is able to take place.

Put simply…

Reading texts involves an almost constant traveling back and forth searching which parts relate to which. This, then, makes inferences so much more difficult, or effortful, to make.

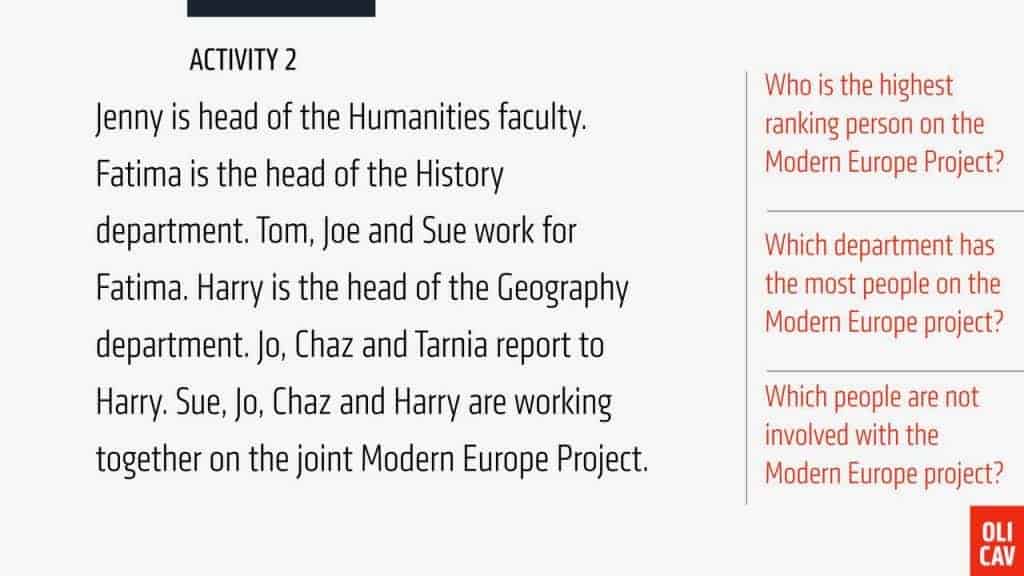

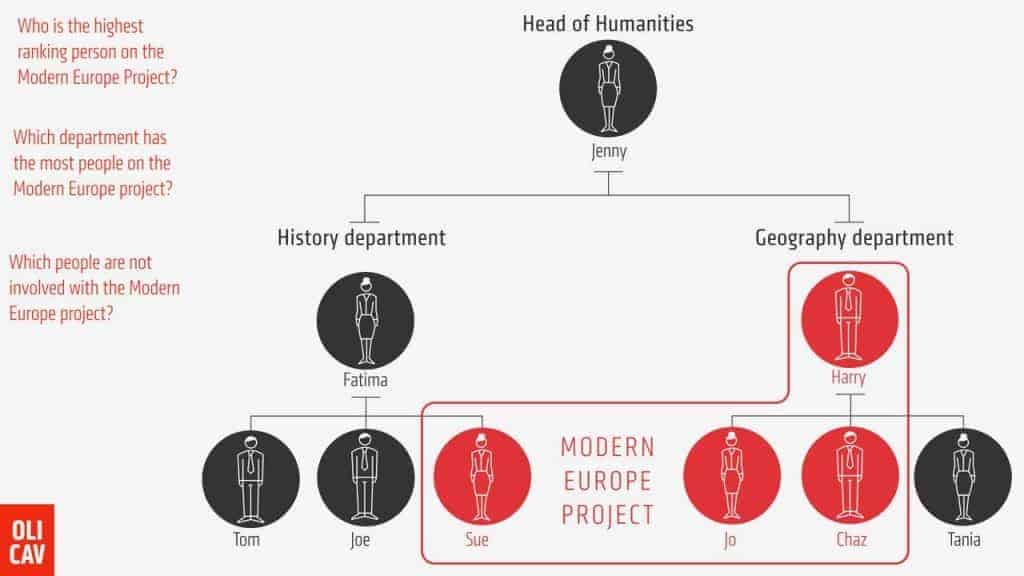

An Example of Dual Coding Theory

The example below, that I use in my presentations to make the concept of computational efficiency come alive, makes the point more effectively than my explanations.

From the text on the left, try and answer the questions. Difficult isn’t it!

Now try to answer the same questions by looking at the image below…

Much easier right?

Convinced of this you may be but, as always, there’s more to it than just presenting a diagram to your students.

As cognitive science authors, Clark and Lyons (2004) warn: “ Visuals ignored, don’t teach ”.

It’s all very well to give your students diagrams that convey information that require less effort to understand, but if you don’t then use them to make your students think, not much will be learned.

Diagrams should be thought of as platforms from which to better analyze texts and prepare for speaking and writing.

And then there are other problems to overcome.

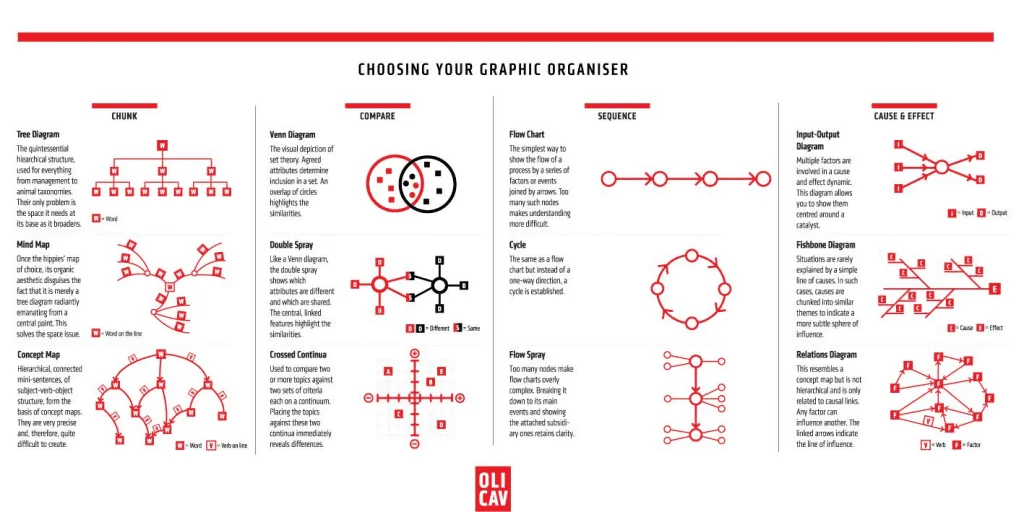

The Visual Argument only happens when teachers have chosen an appropriate visual tool. Exploring the differences between rural and urban settings is not best represented by a timeline for example. And plotting the plot of Hamlet becomes confusing if a mind map is used.

Deductive Reasoning in Dual Coding Theory

Graphic organizers can usefully be grouped along these four types of deductive reasoning:

- Linking cause and effect.

Identifying the nature of the knowledge task is essential before moving on to choose an appropriate visual tool.

As you might now expect, there’s one more danger to avoid.

Supposing the correct organizer is chosen to fit the nature of the task, its execution needs to be adequate.

Clark and Lyons (2004) highlight poor execution as a major factor behind dual coding’s diminished impact.

Above all, teachers need to make their handwriting legible. To be confident of this, printing in a clear, bold style with no flourishes or elaborations, is essential.

Forcing students to decipher a rushed handwritten script is an unnecessary cognitive burden that clearly bears an extraneous, unproductive load.

Other graphic considerations when creating dual coded communications involve the following four principles I devised after responding to requests for feedback from teachers on Twitter.

How to do Dual Coding

Simply to cut—reduce the volume presented on page or slide. It’s the easiest and most effective of all the principles.

Chunk the selected content. Identify the categories so it’s easier to make sense. And signal the chunks by providing more headings than you normally would.

Aligning the chunks, and any other element on the page —line or image— makes scanning and search so much easier for the reader.

In other words, don’t make them ‘artistic’ and random in placement. Order makes reading and scanning so very much easier.

And lastly, continuing on the non-artistic perspective, practice restraint in the number and intensity of colors used, along with the use of a single typeface (font) ensuring it isn’t a fancy, hard-to-read display font or Comic Sans.

Typographers have a long history of theory, research and practice as to what makes reading easy.

Just look closely at any newspaper or magazine design and you will see these principles in action.

For a more detailed explanation of dual coding theory and examples of how it can be included in your classroom practice, Oliver’s book; “ Dual Coding with Teachers ” is perfect, it will be hugely useful to any teacher.

Similar Posts:

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

- 20 Huge Benefits of Using Technology in the Classroom

5 thoughts on “Dual Coding Theory: The Complete Guide for Teachers”

The diagram made things much easier. I my even make an assignment for the students to read that ( or any other type) of question, and make their own diagram. As long as you have problems that have a proper flow, I think this is a great way to visualize the problems and be creative in their own diagrams.

Interesting article. I agree with the article’s content and have always believed in the power of symbols. Key point is that teachers must be deliberate in the selection of their visual aids/diagrams.

When I introduce a new topic in social studies, I create easy to read and simple visuals to show the important info so students will focus on the over all idea rather than in all the detail.

When I introduce a new topic in social studies, I like to show my students different visuals to highlight the important information I aim to help my students focus on.

I understand how the use of images, visuals and organizers can help, but I am not sure how I could incorporate it into an elementary level music lesson. If I am comparing 2 songs, I may use a Venn diagram, but I am not using graphics regularly.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

- skip to content

Learning Theories

- Recent Changes

- Media Manager

Table of Contents

What is dual coding theory, what is the practical meaning of dual coding theory, keywords and most important names, bibliography, dual coding theory.

Dual coding is a theory of cognition introduced by Allan Paivio in late 1960s. This theory suggests that there are two distinct subsystems contributing to cognition: one is specialized for language and verbal information, and the other for images and non-verbal information. According to Paivio,

- “ Human cognition is unique in that it has become specialized for dealing simultaneously with language and with nonverbal objects and events. ” 1)

- “ The most general assumption in dual coding theory is that there are two classes of phenomena handled cognitively by separate subsystems, one specialized for the representation and processing of information concerning nonverbal objects and events, the other specialized for dealing with language. ” 2)

The two mentioned kinds of processing systems, verbal and non-verbal are functionally and structurally independent. This means that each of them can work independently of the other one and that they work on different kinds of representational units. Representational units are “ relatively stable long-term information corresponding to perceptually identifiable objects and activities, both verbal and nonverbal. ”. 3) They are divided into:

- logogens , referring to verbal entities (spoken or written words) and organized in terms of associations and hierarchies, and

- imagens , referring to mental images and non-verbal entities and organized in terms of part-whole relationships.

For example, a written or spoken word will be processed using the verbal processor and stored as a verbal representation - logogen, but a sound not related to language will be processed by the non-verbal processor and stored as a non-verbal representation - imagen. Logogens and imagens are connected with two kinds of connections:

- Referential connections , which represent links between logogens and imagens. Referential connections enable performing operations like imaging to words and namings to pictures or images to words. For example, associations of an image of a school building or an unpleasant feeling (both non-verbal entities) elicited by the word school (a verbal entity).

- Associative connections , which represent connections between logogens or between imagens. Associative connections on the other hand enable forming verbal-verbal or non-verbal-non-verbal associations. For example, the word school can elicit verbal entities blackboard , or boredom .

Both referential and associative types of connections help forming the complex networks of human memory.

Paivio also refers to the issue of problem-solving. Problem-solving is, according to Pavio, the result of joined work of both verbal and non-verbal processing, but if the task is more concrete and non-verbal, the contribution of non-verbal processing system will be more crucial to the outcome and vice-versa.

Dual coding theory suggests that combining verbal and graphical material in learning (or just encouraging students to generate appropriate mental images) should increase the probability that words will activate corresponding images and vice-versa.

This also means that learning material will be easier to relate if it is less abstract.

- “ … concrete nouns are superior to abstract nouns in their capacity to elicit sensory images, and that imagery can mediate the formation of an associative connection between members of a pair. ” 4)

Paivio also addresses individual differences in tendency and capacity to use imagery:

- “ Students who have trouble imaging , for example, may fail to remember passages of text that benefit from imaginal processing, may not understand geography or other spatial facts in a concrete way, and might do poorly at visualizing the steps in a geometric proof, spelling difficult words or even printing letters correctly. ”

Common criticisms of dual coding theory suggest that there is no need for two representational systems, since both verbal and non-verbal stimuli are processed in working memory, turned to semantic elements or propositions and are stored in long-term memory. This assumption is sometimes also known as the single-coding theory . 5)

- Allan Paivio

- Dual coding theory , verbal and non-verbal system , logogen , imagen , referential connections , associative connections

Paivio, Allan. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Ryu, Jiyeon, Tingling Lai, Susan Colaric, Joanne Cawley, and Habibe Aldag. Dual Coding Theory. 2000.

Paivio, Allan. Imagery and verbal processes. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. New York, 1971.

- Show pagesource

- Old revisions

- Export to PDF

- Back to top

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Dual-coding theory is a theory of cognition that suggests that the mind processes information along two different channels; verbal and nonverbal. It was hypothesized by Allan Paivio of the University of Western Ontario in 1971. In developing this theory, Paivio used the idea that the formation of mental imagery …

The dual coding theory by Allan Paivio. According to Paivio, there are two ways in which a person can extend what they learn with verbal associations and visual images. Dual coding theory states that one can use …

Dual Coding and Common Coding Theories of Memory. The Dual Coding Theory of memory was initially proposed by Paivio (1971) in order to explain the powerful mnemonic effects of imagery …

What is Dual Coding Theory? Allan Pavio discovered that our memory has two codes (or channels) that deal with visual and verbal stimuli. Whilst it stores them independently, they are linked (linking words to images). …

The dual coding theory postulates that abstract concepts and words are represented in a verbal system, whereas only concrete ones are represented by both verbal and imagery codes …

Dual coding theory (DCT) explains human behavior and experience in terms of dynamic associative processes that operate on a rich network of modality- specific verbal and nonverbal …

Dual coding theory suggests that combining verbal and graphical material in learning (or just encouraging students to generate appropriate mental images) should increase the probability that words will activate corresponding images …