You are here

Feminist approaches to literature.

This essay offers a very basic introduction to feminist literary theory, and a compendium of Great Writers Inspire resources that can be approached from a feminist perspective. It provides suggestions for how material on the Great Writers Inspire site can be used as a starting point for exploration of or classroom discussion about feminist approaches to literature. Questions for reflection or discussion are highlighted in the text. Links in the text point to resources in the Great Writers Inspire site. The resources can also be found via the ' Feminist Approaches to Literature' start page . Further material can be found via our library and via the various authors and theme pages.

The Traditions of Feminist Criticism

According to Yale Professor Paul Fry in his lecture The Classical Feminist Tradition from 25:07, there have been several prominent schools of thought in modern feminist literary criticism:

- First Wave Feminism: Men's Treatment of Women In this early stage of feminist criticism, critics consider male novelists' demeaning treatment or marginalisation of female characters. First wave feminist criticism includes books like Marry Ellman's Thinking About Women (1968) Kate Millet's Sexual Politics (1969), and Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch (1970). An example of first wave feminist literary analysis would be a critique of William Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew for Petruchio's abuse of Katherina.

- The 'Feminine' Phase - in the feminine phase, female writers tried to adhere to male values, writing as men, and usually did not enter into debate regarding women's place in society. Female writers often employed male pseudonyms during this period.

- The 'Feminist' Phase - in the feminist phase, the central theme of works by female writers was the criticism of the role of women in society and the oppression of women.

- The 'Female' Phase - during the 'female' phase, women writers were no longer trying to prove the legitimacy of a woman's perspective. Rather, it was assumed that the works of a women writer were authentic and valid. The female phase lacked the anger and combative consciousness of the feminist phase.

Do you agree with Showalter's 'phases'? How does your favourite female writer fit into these phases?

Read Jane Eyre with the madwoman thesis in mind. Are there connections between Jane's subversive thoughts and Bertha's appearances in the text? How does it change your view of the novel to consider Bertha as an alter ego for Jane, unencumbered by societal norms? Look closely at Rochester's explanation of the early symptoms of Bertha's madness. How do they differ from his licentious behaviour?

How does Jane Austen fit into French Feminism? She uses very concise language, yet speaks from a woman's perspective with confidence. Can she be placed in Showalter's phases of women's writing?

Dr. Simon Swift of the University of Leeds gives a podcast titled 'How Words, Form, and Structure Create Meaning: Women and Writing' that uses the works of Virginia Woolf and Silvia Plath to analyse the form and structural aspects of texts to ask whether or not women writers have a voice inherently different from that of men (podcast part 1 and part 2 ).

In Professor Deborah Cameron's podcast English and Gender , Cameron discusses the differences and similarities in use of the English language between men and women.

In another of Professor Paul Fry's podcasts, Queer Theory and Gender Performativity , Fry discusses sexuality, the nature of performing gender (14:53), and gendered reading (46:20).

How do more modern A-level set texts, like those of Margaret Atwood, Zora Neale Hurston, or Maya Angelou, fit into any of these traditions of criticism?

Depictions of Women by Men

Students could begin approaching Great Writers Inspire by considering the range of women depicted in early English literature: from Chaucer's bawdy 'Wife of Bath' in The Canterbury Tales to Spenser's interminably pure Una in The Faerie Queene .

How might the reign of Queen Elizabeth I have dictated the way Elizabethan writers were permitted to present women? How did each male poet handle the challenge of depicting women?

By 1610 Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker's The Roaring Girl presented at The Fortune a play based on the life of Mary Firth. The heroine was a man playing a woman dressed as a man. In Dr. Emma Smith's podcast on The Roaring Girl , Smith breaks down both the gender issues of the play and of the real life accusations against Mary Frith.

In Dr. Emma Smith's podcast on John Webster's The Duchess of Malfi , a frequent A-level set text, Smith discusses Webster's treatment of female autonomy. Placing Middleton or Webster's female characters against those of Shakespeare could be brought to bear on A-level Paper 4 on Drama or Paper 5 on Shakespeare and other pre-20th Century Texts.

Smith's podcast on The Comedy of Errors from 11:21 alludes to the valuation of Elizabethan comedy as a commentary on gender and sexuality, and how The Comedy of Errors at first seems to defy this tradition.

What are the differences between depictions of women written by male and female novelists?

Students can compare the works of Charlotte and Emily Brontë or Jane Austen with, for example, Hardy's Tess of the d'Ubervilles or D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover or Women in Love .

How do Lawrence's sexually charged novels compare with what Emma Smith said about Webster's treatment of women's sexuality in The Duchess of Malfi ?

Dr. Abigail Williams' podcast on Jonathan Swift's The Lady's Dressing-Room discusses the ways in which Swift uses and complicates contemporary stereotypes about the vanity of women.

Rise of the Woman Writer

With the movement from Renaissance to Restoration theatre, the depiction of women on stage changed dramatically, in no small part because women could portray women for the first time. Dr. Abigail Williams' adapted lecture, Behn and the Restoration Theatre , discusses Behn's use and abuse of the woman on stage.

What were the feminist advantages and disadvantages to women's introduction to the stage?

The essay Who is Aphra Behn? addresses the transformation of Behn into a feminist icon by later writers, especially Bloomsbury Group member Virginia Woolf in her novella/essay A Room of One's Own .

How might Woolf's description and analysis of Behn indicate her own feminist agenda?

Behn created an obstacle for later women writers in that her scandalous life did little to undermine the perception that women writing for money were little better than whores.

In what position did that place chaste female novelists like Frances Burney or Jane Austen ?

To what extent was the perception of women and the literary vogue for female heroines impacted by Samuel Richardson's Pamela ? Students could examine a passage from Pamela and evaluate Richardson's success and failures, and look for his influence in novels with which they are more familiar, like those of Austen or the Brontë sisters.

In Dr. Catherine's Brown's podcast on Eliot's Reception History , Dr. Brown discusses feminist criticism of Eliot's novels. In the podcast Genre and Justice , she discusses Eliot's use of women as scapegoats to illustrate the injustice of the distribution of happiness in Victorian England.

Professor Sir Richard Evans' Gresham College lecture The Victorians: Gender and Sexuality can provide crucial background for any study of women in Victorian literature.

Women Writers and Class

Can women's financial and social plights be separated? How do Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë bring to bear financial concerns regarding literature depicting women in the 18th and 19th century?

How did class barriers affect the work of 18th century kitchen maid and poet Mary Leapor ?

Listen to the podcast by Yale's Professor Paul Fry titled "The Classical Feminist Tradition" . At 9:20, Fry questions whether or not any novel can be evaluated without consideration of financial and class concerns, and to what extent Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own suggests a female novelist can only create successful work if she is of independent means.

What are the different problems faced by a wealthy character like Austen's Emma , as opposed to a poor character like Brontë's Jane Eyre ?

Also see sections on the following writers:

- Jane Austen

- Charlotte Brontë

- George Eliot

- Thomas Hardy

- D.H. Lawrence

- Mary Leapor

- Thomas Middleton

- Katherine Mansfield

- Olive Schreiner

- William Shakespeare

- John Webster

- Virginina Woolf

If reusing this resource please attribute as follows: Feminist Approaches to Literature at http://writersinspire.org/content/feminist-approaches-literature by Kate O'Connor, licensed as Creative Commons BY-NC-SA (2.0 UK).

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › British Literature › Feminist Literary Criticism

Feminist Literary Criticism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 7, 2022

Feminist literary criticism has its origins in the intellectual and political feminist movement. It advocates a critique of maledominated language and performs “resistant” readings of literary texts or histories. Based on the premise that social systems are patriarchal—organized to privilege men—it seeks to trace how such power relations in society are reflected, supported, or questioned by literary texts and expression.

One of the founders of this kind of approach was Virginia Woolf , who showed in her 1929 essay A Room of One’s Own how women’s material and intellectual deprivation were obstacles to authorship. Woolf illustrated her case with the abortive artistic aspirations of Shakespeare’s fictitious sister Judith. In another essay, “Professions for Women,” Woolf also announced the necessity for women writers to kill the “angel in the house,” taking her cue from Coventry Patmore’s mid-Victorian poem of the same name that glorified a domestic (or domesticated) femininity devoid of any critical spirit.

Another important source of inspiration has been Simone de Beauvoir ’s 1949 The Second Sex . Here de Beauvoir wrote that “one is not born a woman, one becomes one.” De Beauvoir’s point behind her muchquoted comment was that “ ‘woman’ is a cultural construction, rather than a biological one.” As Ruth Robbins notes, this remark is important because it highlights the fact that “the ideas about male and female roles which any given society may have come to regard as natural are not really so and that given that they are not natural they may even be changed” (118). All three texts provided ammunition for the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s and are useful starting points for discussions of short stories that take women and the feminine as central concerns.

The ensuing critical response may best be described as bifurcating into an Anglo-American and a French strand. The former was defined by the greater importance British feminists such as Sheila Rowbotham, Germaine Greer, and Michèle Barrett attached to class. Literary critics working in this school were interested in representations of women in literary texts, an approach most famously encapsulated in Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics (1970)—probably the world’s best-selling doctoral thesis. Groundbreaking as the book turned out to be in reading canonized authors (e.g., Charles Dickens, D. H. Lawrence) against the grain and in drawing attention to their suffocating (and often misogynist) representations of women, it was also criticized for its insistence on a male conspiracy. There were objections that its readings were too often based on the assumption that literature simply mirrors reality.

Left, Susan Gubar. Right, Sandra M. Gilbert. | Left, Eli Setiya. Right, Peter Basmajian. Via Vox

Subsequent critics sought to redress the gaps in Millet’s book by setting out to discover and reevaluate neglected female writing. Among those mapping this dark continent (in Sigmund Freud’s trope) was Ellen Moers, whose Literary Women (1976) is often seen as pioneering in its attempts to focus on noncanonical women writers such as Mary Shelley. The book has since been criticized on account of its unqualified appraisal of “heroinism,” an appraisal that leaves the concept of the “great writer”—a central category of male literary historiography—intact. One of the terms used by Elaine Showalter in A Literature of Their Own (1977) is “ gynocriticism ,” a term intended to indicate her concern with the history of women as authors. In A Literature of Their Own Showalter posited the idea of a “feminine” period of literary history (1840–80) in which the experiences of women such as the Brontës, Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, and George Eliot—notably their use of male pseudonyms and imitation of male standards—demonstrate the obstacles women writers have tended to face. Showalter then described a second phase (1880–1920) that comprised so-called New Woman writers (e.g., Vernon Lee, George Egeron, Ella D’Arcy) dedicated to protest and minority rights. After 1920, this feminist stage was transcended by a female phase whose major representatives, Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf are said to move beyond mimicry or opposition by asserting feminine identities, no matter how fragile or provisional these might be. Their narratives explore allegedly minor yet personally significant, even epiphanic moments and experiment with gender roles including androgyny and homosexuality. Literary texts of this period can also be said to anticipate postmodernist views of gender in their emphasis on the cultural interpretation of the body as distinguished from the physical characteristics that make people male or female.

Further landmarks in the field of feminist research were provided by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar ’s The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Imagination (1979) and The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women (1985). The Madwoman, runner-up for a Pulitzer Prize in 1980, attributed an “anxiety of authorship” to writers such as Jane Austen, the Brontës, and George Eliot. It also posited the widespread imagery of guilt or rage in texts by 19th-century women writers as part of a specifically female aesthetic—an aesthetic whose distinctness from male writers was emphasized in the canon of women’s literature as established by the 1985 Norton Anthology. Gilbert and Gubar have remained extremely influential, although some critics have questioned the clearcut separatism of their canon (male versus female) on the grounds that it unconsciously validates the implicit patriarchal ideology.

French feminism shifted the focus onto language. Its proponents drew on Freudian models of infant development that the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan had connected with processes of language acquisition and the construction of sexual difference. Lacan’s disciples Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, and Luce Irigaray started from the premise that a child’s entry into language coincides with the disruption of its dyadic relationship with the mother. Language then reflects a binary logic that works through oppositions such as male/female, nature/culture. This pattern connecting oppression and language tends to group positive qualities with the masculine side. Woman, it is argued, is therefore alienated from linguistic structures and is liable to turn to a different discourse, derived from a preoedipal, “semiotic” period of fusion of mother and child. As so-called écriture feminine , this form of writing disturbs the organizing principles of “symbolic” masculinized language. It dissolves generic boundaries, causal plot, stable perspectives, and meaning in favor of rhythmic and highly allusive writing. Such transgression, though, is not gender-specific but can be performed by anyone—indeed, James Joyce is cited as the major representative of “writing one’s body” on the margins of dominant culture.

Both the French celebration of disruptive textual pleasure and the Anglo-American analysis of textual content have come under attack for their underlying assumption that all women—African slave and European housewife—share the same oppression. Postcolonial feminism, as advanced by Alice Walker, bell hooks, Gayatri Spivak, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, took issue with the reductive ways of representing nonwhite women as sexually constrained, uneducated, and in need of being spoken for. They also objected to feminism’s insistence that women needed to reinforce their homogeneity as a sex, because they felt that this thinking demonstrated an ignorance of plurality and in fact perpetuated the very hierarchies on which patriarchy and Western imperialism had thrived.

From today’s perspective, so much has been done to improve female presence that some commentators have suggested that we live in an age of postfeminism . However, there are many who would argue that even in a postfeminist age much needs to be done to highlight the importance of interrogating seemingly natural signs of male/female difference. Critics following Judith Butler have begun to entertain the idea that the very assumption of an innate biological sex might itself be a cultural strategy to justify gender attributes. Whether one accepts this position or not, seeing identities as the embodiments of cultural practices may prompt change. This, in turn, might pave the way for a correspondingly flexible critical approach to identities as things that are entwined with other categories: ethnicity, sexual orientation, social status, health, age, or belief. In this sense, the prefix post- should not be read as meaning after feminism or as suggesting a rejection of feminism; rather, it should suggest a more self-reflexive working on the blind spots of former readings.

Key Ideas of Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar

Post-Feminism: An Essay

Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics

Simone de Beauvoir and The Second Sex

Feminism: An Essay

Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

BIBLIOGRAPHY Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1999. Eagleton, Mary. Working with Feminist Criticism. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996. Gamble, Sarah, ed. The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Postfeminism. London: Routledge, 2001. Hanson, Clare, ed. Re-reading the Short Story. New York: St. Martin’s, 1989. Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics. Feminist Literary Theory. London: Methuen, 1985. Ruth Robbins, “Feminist Approaches.” in Literary Theories, edited by Julian Wolfreys and William Baker, 103–126. London: Macmillan, 1998. Showalter, Elaine. A Literature of Their Own. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Share this:

Categories: British Literature , Gender Studies , Literary Terms and Techniques , Literature , Queer Theory

Tags: Alice Walker , and George Eliot , bell hooks , Brontës , Chandra Talpade Mohanty , Elaine Showalter , Elizabeth Gaskell , Ella D'Arcy , Ellen Moers , Feminism , Feminism and literary criticism , Feminism and Literary Theory , Feminist literary criticism , Feminist Literary Criticism Analysis , Feminist Literary Criticism history , feminist literary critics , Feminist literary theory , feminist movement , Gayatri Spivak , George Egeron , Key works by Feminist Literary Critics , major Feminist Literary Critics , Mary Elizabeth Braddon , Vernon Lee

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Feminist theory and its use in qualitative research in education.

- Emily Freeman Emily Freeman University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1193

- Published online: 28 August 2019

Feminist theory rose in prominence in educational research during the 1980s and experienced a resurgence in popularity during the late 1990s−2010s. Standpoint epistemologies, intersectionality, and feminist poststructuralism are the most prevalent theories, but feminist researchers often work across feminist theoretical thought. Feminist qualitative research in education encompasses a myriad of methods and methodologies, but projects share a commitment to feminist ethics and theories. Among the commitments are the understanding that knowledge is situated in the subjectivities and lived experiences of both researcher and participants and research is deeply reflexive. Feminist theory informs both research questions and the methodology of a project in addition to serving as a foundation for analysis. The goals of feminist educational research include dismantling systems of oppression, highlighting gender-based disparities, and seeking new ways of constructing knowledge.

- feminist theories

- qualitative research

- educational research

- positionality

- methodology

Introduction

Feminist qualitative research begins with the understanding that all knowledge is situated in the bodies and subjectivities of people, particularly women and historically marginalized groups. Donna Haraway ( 1988 ) wrote,

I am arguing for politics and epistemologies of location, position, and situating, where partiality and not universality is the condition of being heard to make rational knowledge claims. These are claims on people’s lives I’m arguing for the view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structuring, and structured body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplicity. Only the god trick is forbidden. . . . Feminism is about a critical vision consequent upon a critical positioning in unhomogeneous gendered social space. (p. 589)

By arguing that “politics and epistemologies” are always interpretive and partial, Haraway offered feminist qualitative researchers in education a way to understand all research as potentially political and always interpretive and partial. Because all humans bring their own histories, biases, and subjectivities with them to a research space or project, it is naïve to think that the written product of research could ever be considered neutral, but what does research with a strong commitment to feminism look like in the context of education?

Writing specifically about the ways researchers of both genders can use feminist ethnographic methods while conducting research on schools and schooling, Levinson ( 1998 ) stated, “I define feminist ethnography as intensive qualitative research, aimed toward the description and analysis of the gendered construction and representation of experience, which is informed by a political and intellectual commitment to the empowerment of women and the creation of more equitable arrangements between and among specific, culturally defined genders” (p. 339). The core of Levinson’s definition is helpful for understanding the ways that feminist educational anthropologists engage with schools as gendered and political constructs and the larger questions of feminist qualitative research in education. His message also extends to other forms of feminist qualitative research. By focusing on description, analysis, and representation of gendered constructs, educational researchers can move beyond simple binary analyses to more nuanced understandings of the myriad ways gender operates within educational contexts.

Feminist qualitative research spans the range of qualitative methodologies, but much early research emerged out of the feminist postmodern turn in anthropology (Behar & Gordon, 1995 ), which was a response to male anthropologists who ignored the gendered implications of ethnographic research (e.g., Clifford & Marcus, 1986 ). Historically, most of the work on feminist education was conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, with a resurgence in the late 2010s (Culley & Portuges, 1985 ; DuBois, Kelly, Kennedy, Korsmeyer, & Robinson, 1985 ; Gottesman, 2016 ; Maher & Tetreault, 1994 ; Thayer-Bacon, Stone, & Sprecher, 2013 ). Within this body of research, the majority focuses on higher education (Coffey & Delamont, 2000 ; Digiovanni & Liston, 2005 ; Diller, Houston, Morgan, & Ayim, 1996 ; Gabriel & Smithson, 1990 ; Mayberry & Rose, 1999 ). Even leading journals, such as Feminist Teacher ( 1984 −present), focus mostly on the challenges of teaching about and to women in higher education, although more scholarship on P–12 education has emerged in recent issues.

There is also a large collection of work on the links between gender, achievement, and self-esteem (American Association of University Women, 1992 , 1999 ; Digiovanni & Liston, 2005 ; Gilligan, 1982 ; Hancock, 1989 ; Jackson, Paechter, & Renold, 2010 ; National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education, 2002 ; Orenstein, 1994 ; Pipher, 1994 ; Sadker & Sadker, 1994 ). However, just because research examines gender does not mean that it is feminist. Simply using gender as a category of analysis does not mean the research project is informed by feminist theory, ethics, or methods, but it is often a starting point for researchers who are interested in the complex ways gender is constructed and the ways it operates in education.

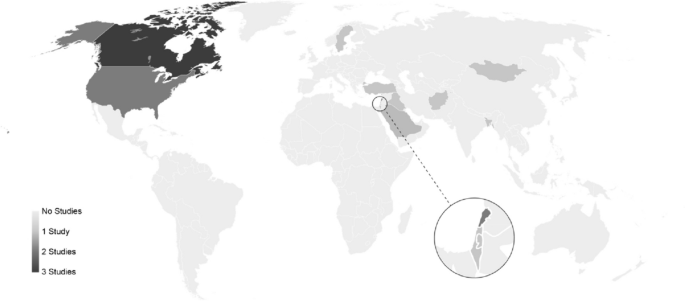

This article examines the histories and theories of U.S.–based feminism, the tenets of feminist qualitative research and methodologies, examples of feminist qualitative studies, and the possibilities for feminist qualitative research in education to provide feminist educational researchers context and methods for engaging in transformative and subversive research. Each section provides a brief overview of the major concepts and conversations, along with examples from educational research to highlight the ways feminist theory has informed educational scholarship. Some examples are given limited attention and serve as entry points into a more detailed analysis of a few key examples. While there is a large body of non-Western feminist theory (e.g., the works of Lila Abu-Lughod, Sara Ahmed, Raewyn Connell, Saba Mahmood, Chandra Mohanty, and Gayatri Spivak), much of the educational research using feminist theory draws on Western feminist theory. This article focuses on U.S.–based research to show the ways that the utilization of feminist theory has changed since the 1980s.

Histories, Origins, and Theories of U.S.–Based Feminism

The normative historiography of feminist theory and activism in the United States is broken into three waves. First-wave feminism (1830s−1920s) primarily focused on women’s suffrage and women’s rights to legally exist in public spaces. During this time period, there were major schisms between feminist groups concerning abolition, rights for African American women, and the erasure of marginalized voices from larger feminist debates. The second wave (1960s and 1980s) worked to extend some of the rights won during the first wave. Activists of this time period focused on women’s rights to enter the workforce, sexual harassment, educational equality, and abortion rights. During this wave, colleges and universities started creating women’s studies departments and those scholars provided much of the theoretical work that informs feminist research and activism today. While there were major feminist victories during second-wave feminism, notably Title IX and Roe v. Wade , issues concerning the marginalization of race, sexual orientation, and gender identity led many feminists of color to separate from mainstream white feminist groups. The third wave (1990s to the present) is often characterized as the intersectional wave, as some feminist groups began utilizing Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality ( 1991 ) to understand that oppression operates via multiple categories (e.g., gender, race, class, age, ability) and that intersecting oppressions lead to different lived experiences.

Historians and scholars of feminism argue that dividing feminist activism into three waves flattens and erases the major contributions of women of color and gender-nonconforming people. Thompson ( 2002 ) called this history a history of hegemonic feminism and proposed that we look at the contributions of multiracial feminism when discussing history. Her work, along with that of Allen ( 1984 ) about the indigenous roots of U.S. feminism, raised many questions about the ways that feminism operates within the public and academic spheres. For those who wish to engage in feminist research, it is vital to spend time understanding the historical, theoretical, and political ways that feminism(s) can both liberate and oppress, depending on the scholar’s understandings of, and orientations to, feminist projects.

Standpoint Epistemology

Much of the theoretical work that informs feminist qualitative research today emerged out of second-wave feminist scholarship. Standpoint epistemology, according to Harding ( 1991 , 2004 ), posits that knowledge comes from one’s particular social location, that it is subjective, and the further one is from the hegemonic norm, the clearer one can see oppression. This was a major challenge to androcentric and Enlightenment theories of knowledge because standpoint theory acknowledges that there is no universal understanding of the world. This theory aligns with the second-wave feminist slogan, “The personal is political,” and advocates for a view of knowledge that is produced from the body.

Greene ( 1994 ) wrote from a feminist postmodernist epistemology and attacked Enlightenment thinking by using standpoint theory as her starting point. Her work serves as an example of one way that educational scholars can use standpoint theory in their work. She theorized encounters with “imaginative literature” to help educators conceptualize new ways of using reading and writing in the classroom and called for teachers to think of literature as “a harbinger of the possible.” (Greene, 1994 , p. 218). Greene wrote from an explicitly feminist perspective and moved beyond simple analyses of gender to a larger critique of the ways that knowledge is constructed in classrooms.

Intersectionality

Crenshaw ( 1991 ) and Collins ( 2000 ) challenged and expanded standpoint theory to move it beyond an individual understanding of knowledge to a group-based theory of oppression. Their work, and that of other black and womanist feminists, opened up multiple spaces of possibility for feminist scholars and researchers because it challenged hegemonic feminist thought. For those interested in conducting feminist research in educational settings, their work is especially pertinent because they advocate for feminists to attend to all aspects of oppression rather than flattening them to one of simple gender-based oppression.

Haddix, McArthur, Muhammad, Price-Dennis, and Sealey-Ruiz ( 2016 ), all women-of-color feminist educators, wrote a provocateur piece in a special issue of English Education on black girls’ literacy. The four authors drew on black feminist thought and conducted a virtual kitchen-table conversation. By symbolically representing their conversations as one from the kitchen, this article pays homage to women-of-color feminism and pushes educators who read English Education to reconsider elements of their own subjectivities. Third-wave feminism and black feminism emphasize intersectionality, in that different demographic details like race, class, and gender are inextricably linked in power structures. Intersectionality is an important frame for educational research because identifying the unique experiences, realities, and narratives of those involved in educational systems can highlight the ways that power and oppression operate in society.

Feminist Poststructural Theory

Feminist poststructural theory has greatly informed many feminist projects in educational research. Deconstruction is

a critical practice that aims to ‘dismantle [ déconstruire ] the metaphysical and rhetorical structures that are at work, not in order to reject or discard them, but to reinscribe them in another way,’ (Derrida, quoted in Spivak, 1974 , p. lxxv). Thus, deconstruction is not about tearing down, but about looking at how a structure has been constructed, what holds it together, and what it produces. (St. Pierre, 2000 , p. 482)

Reality, subjectivity, knowledge, and truth are constructed through language and discourse (cultural practices, power relations, etc.), so truth is local and diverse, rather than a universal experience (St. Pierre, 2000 ). Feminist poststructuralist theory may be used to question structural inequality that is maintained in education through dominant discourses.

In Go Be a Writer! Expanding the Curricular Boundaries of Literacy Learning with Children , Kuby and Rucker ( 2016 ) explored early elementary literacy practices using poststructural and posthumanist theories. Their book drew on hours of classroom observations, student interviews and work, and their own musings on ways to de-standardize literacy instruction and curriculum. Through the process of pedagogical documentation, Kuby and Rucker drew on the works of Barad, Deleuze and Guattari, and Derrida to explore the ways they saw children engaging in what they call “literacy desiring(s).” One aim of the book is to find practical and applicable ways to “Disrupt literacy in ways that rewrite the curriculum, the interactions, and the power dynamics of the classroom even begetting a new kind of energy that spirals and bounces and explodes” (Kuby & Rucker, 2016 , p. 5). The second goal of their book is not only to understand what happened in Rucker’s classroom using the theories, but also to unbound the links between “teaching↔learning” (p. 202) and to write with the theories, rather than separating theory from the methodology and classroom enactments (p. 45) because “knowing/being/doing were not separate” (p. 28). This work engages with key tenets of feminist poststructuralist theory and adds to both the theoretical and pedagogical conversations about what counts as a literacy practice.

While the discussion in this section provides an overview of the histories and major feminist theories, it is by no means exhaustive. Scholars who wish to engage in feminist educational research need to spend time doing the work of understanding the various theories and trajectories that constitute feminist work so they are able to ground their projects and theories in a particular tradition that will inform the ethics and methods of research.

Tenets of Feminist Qualitative Research

Why engage in feminist qualitative research.

Evans and Spivak ( 2016 ) stated, “The only real and effective way you can sabotage something this way is when you are working intimately within it.” Feminist researchers are in the classroom and the academy, working intimately within curricular, pedagogical, and methodological constraints that serve neoliberal ideologies, so it is vital to better understand the ways that we can engage in affirmative sabotage to build a more just and equitable world. Spivak’s ( 2014 ) notion of affirmative sabotage has become a cornerstone for understanding feminist qualitative research and teaching. She borrowed and built on Gramsci’s role of the organic intellectual and stated that they/we need to engage in affirmative sabotage to transform the humanities.

I used the term “affirmative sabotage” to gloss on the usual meaning of sabotage: the deliberate ruining of the master’s machine from the inside. Affirmative sabotage doesn’t just ruin; the idea is of entering the discourse that you are criticizing fully, so that you can turn it around from inside. The only real and effective way you can sabotage something this way is when you are working intimately within it. (Evans & Spivak, 2016 )

While Spivak has been mostly concerned with literary education, her writings provide teachers and researchers numerous lines of inquiry into projects that can explode androcentric universal notions of knowledge and resist reproductive heteronormativity.

Spivak’s pedagogical musings center on deconstruction, primarily Derridean notions of deconstruction (Derrida, 2016 ; Jackson & Mazzei, 2012 ; Spivak, 2006 , 2009 , 2012 ) that seek to destabilize existing categories and to call into question previously unquestioned beliefs about the goals of education. Her works provide an excellent starting point for examining the links between feminism and educational research. The desire to create new worlds within classrooms, worlds that are fluid, interpretive, and inclusive in order to interrogate power structures, lies at the core of what it means to be a feminist education researcher. As researchers, we must seriously engage with feminist theory and include it in our research so that feminism is not seen as a dirty word, but as a movement/pedagogy/methodology that seeks the liberation of all (Davis, 2016 ).

Feminist research and feminist teaching are intrinsically linked. As Kerkhoff ( 2015 ) wrote, “Feminist pedagogy requires students to challenge the norms and to question whether existing practices privilege certain groups and marginalize others” (p. 444), and this is exactly what feminist educational research should do. Bailey ( 2001 ) called on teachers, particularly those who identify as feminists, to be activists, “The values of one’s teaching should not be separated sharply from the values one expresses outside the classroom, because teaching is not inherently pure or laboratory practice” (p. 126); however, we have to be careful not to glorify teachers as activists because that leads to the risk of misinterpreting actions. Bailey argued that teaching critical thinking is not enough if it is not coupled with curriculums and pedagogies that are antiheteronormative, antisexist, and antiracist. As Bailey warned, just using feminist theory or identifying as a feminist is not enough. It is very easy to use the language and theories of feminism without being actively feminist in one’s research. There are ethical and methodological issues that feminist scholars must consider when conducting research.

Feminist research requires one to discuss ethics, not as a bureaucratic move, but as a reflexive move that shows the researchers understand that, no matter how much they wish it didn’t, power always plays a role in the process. According to Davies ( 2014 ), “Ethics, as Barad defines it, is a matter of questioning what is being made to matter and how that mattering affects what it is possible to do and to think” (p. 11). In other words, ethics is what is made to matter in a particular time and place.

Davies ( 2016 ) extended her definition of ethics to the interactions one has with others.

This is not ethics as a matter of separate individuals following a set of rules. Ethical practice, as both Barad and Deleuze define it, requires thinking beyond the already known, being open in the moment of the encounter, pausing at the threshold and crossing over. Ethical practice is emergent in encounters with others, in emergent listening with others. It is a matter of questioning what is being made to matter and how that mattering affects what it is possible to do and to think. Ethics is emergent in the intra-active encounters in which knowing, being, and doing (epistemology, ontology, and ethics) are inextricably linked. (Barad, 2007 , p. 83)

The ethics of any project must be negotiated and contested before, during, and after the process of conducting research in conjunction with the participants. Feminist research is highly reflexive and should be conducted in ways that challenge power dynamics between individuals and social institutions. Educational researchers must heed the warning to avoid the “god-trick” (Haraway, 1988 ) and to continually question and re-question the ways we seek to define and present subjugated knowledge (Hesse-Biber, 2012 ).

Positionalities and Reflexivity

According to feminist ethnographer Noelle Stout, “Positionality isn’t meant to be a few sentences at the beginning of a work” (personal communication, April 5, 2016 ). In order to move to new ways of experiencing and studying the world, it is vital that scholars examine the ways that reflexivity and positionality are constructed. In a glorious footnote, Margery Wolf ( 1992 ) related reflexivity in anthropological writing to a bureaucratic procedure (p. 136), and that resonates with how positionality often operates in the field of education.

The current trend in educational research is to include a positionality statement that fixes the identity of the author in a particular place and time and is derived from feminist standpoint theory. Researchers should make their biases and the identities of the authors clear in a text, but there are serious issues with the way that positionality functions as a boundary around the authors. Examining how the researchers exert authority within a text allows the reader the opportunity to determine the intent and philosophy behind the text. If positionality were used in an embedded and reflexive manner, then educational research would be much richer and allow more nuanced views of schools, in addition to being more feminist in nature. The rest of this section briefly discussrs articles that engage with feminist ethics regarding researcher subjectivities and positionality, and two articles are examined in greater depth.

When looking for examples of research that includes deeply reflexive and embedded positionality, one finds that they mostly deal with issues of race, equity, and diversity. The highlighted articles provide examples of positionality statements that are deeply reflexive and represent the ways that feminist researchers can attend to the ethics of being part of a research project. These examples all come from feminist ethnographic projects, but they are applicable to a wide variety of feminist qualitative projects.

Martinez ( 2016 ) examined how research methods are or are not appropriate for specific contexts. Calderon ( 2016 ) examined autoethnography and the reproduction of “settler colonial understandings of marginalized communities” (p. 5). Similarly, Wissman, Staples, Vasudevan, and Nichols ( 2015 ) discussed how to research with adolescents through engaged participation and collaborative inquiry, and Ceglowski and Makovsky ( 2012 ) discussed the ways researchers can engage in duoethnography with young children.

Abajian ( 2016 ) uncovered the ways military recruiters operate in high schools and paid particular attention to the politics of remaining neutral while also working to subvert school militarization. She wrote,

Because of the sensitive and also controversial nature of my research, it was not possible to have a collaborative process with students, teachers, and parents. Purposefully intervening would have made documentation impossible because that would have (rightfully) aligned me with anti-war and counter-recruitment activists who were usually not welcomed on school campuses (Abajian & Guzman, 2013 ). It was difficult enough to find an administrator who gave me consent to conduct my research within her school, as I had explicitly stated in my participant recruitment letters and consent forms that I was going to research the promotion of post-secondary paths including the military. Hence, any purposeful intervention on my part would have resulted in the termination of my research project. At the same time, my documentation was, in essence, an intervention. I hoped that my presence as an observer positively shaped the context of my observation and also contributed to the larger struggle against the militarization of schools. (p. 26)

Her positionality played a vital role in the creation, implementation, and analysis of military recruitment, but it also forced her into unexpected silences in order to carry out her research. Abajian’s positionality statement brings up many questions about the ways researchers have to use or silence their positionality to further their research, especially if they are working in ostensibly “neutral” and “politically free” zones, such as schools. Her work drew on engaged anthropology (Low & Merry, 2010 ) and critical reflexivity (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell, 2008 ) to highlight how researchers’ subjectivities shape ethnographic projects. Questions of subjectivity and positionality in her work reflect the larger discourses around these topics in feminist theory and qualitative research.

Brown ( 2011 ) provided another example of embedded and reflexive positionality of the articles surveyed. Her entire study engaged with questions about how her positionality influenced the study during the field-work portion of her ethnography on how race and racism operate in ethnographic field-work. This excerpt from her study highlights how she conceived of positionality and how it informed her work and her process.

Next, I provide a brief overview of the research study from which this paper emerged and I follow this with a presentation of four, first-person narratives from key encounters I experienced while doing ethnographic field research. Each of these stories centres the role race played as I negotiated my multiple, complex positionality vis-á-vis different informants and participants in my study. These stories highlight the emotional pressures that race work has on the researcher and the research process, thus reaffirming why one needs to recognise the role race plays, and may play, in research prior to, during, and after conducting one’s study (Milner, 2007 ). I conclude by discussing the implications these insights have on preparing researchers of color to conduct cross-racial qualitative research. (Brown, 2011 , p. 98)

Brown centered the roles of race and subjectivity, both hers and her participants, by focusing her analysis on the four narratives. The researchers highlighted in this section thought deeply about the ethics of their projects and the ways that their positionality informed their choice of methods.

Methods and Challenges

Feminist qualitative research can take many forms, but the most common data collection methods include interviews, observations, and narrative or discourse analysis. For the purposes of this article, methods refer to the tools and techniques researchers use, while methodology refers to the larger philosophical and epistemological approaches to conducting research. It is also important to note that these are not fixed terms, and that there continues to be much debate about what constitutes feminist theory and feminist research methods among feminist qualitative researchers. This section discusses some of the tensions and constraints of using feminist theory in educational research.

Jackson and Mazzei ( 2012 ) called on researchers to think through their data with theory at all stages of the collection and analysis process. They also reminded us that all data collection is partial and informed by the researcher’s own beliefs (Koro-Ljungberg, Löytönen, & Tesar, 2017 ). Interviews are sites of power and critiques because they show the power of stories and serve as a method of worlding, the process of “making a world, turning insight into instrument, through and into a possible act of freedom” (Spivak, 2014 , p. xiii). Interviews allow researchers and participants ways to engage in new ways of understanding past experiences and connecting them to feminist theories. The narratives serve as data, but it is worth noting that the data collected from interviews are “partial, incomplete, and always being re-told and re-membered” (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012 , p. 3), much like the lived experiences of both researcher and participant.

Research, data collection, and interpretation are not neutral endeavors, particularly with interviews (Jackson & Mazzei, 2009 ; Mazzei, 2007 , 2013 ). Since education research emerged out of educational psychology (Lather, 1991 ; St. Pierre, 2016 ), historically there has been an emphasis on generalizability and positivist data collection methods. Most feminist research makes no claims of generalizability or truth; indeed, to do so would negate the hyperpersonal and particular nature of this type of research (Love, 2017 ). St. Pierre ( 2016 ) viewed the lack of generalizability as an asset of feminist and poststructural research, rather than a limitation, because it creates a space of resistance against positivist research methodologies.

Denzin and Giardina ( 2016 ) urged researchers to “consider an alternative mode of thinking about the critical turn in qualitative inquiry and posit the following suggestion: perhaps it is time we turned away from ‘methodology’ altogether ” (p. 5, italics original). Despite the contention over the term critical among some feminist scholars (e.g. Ellsworth, 1989 ), their suggestion is valid and has been picked up by feminist and poststructural scholars who examine the tensions between following a strict research method/ology and the theoretical systems out of which they operate because precision in method obscures the messy and human nature of research (Koro-Ljungberg, 2016 ; Koro-Ljungberg et al., 2017 ; Love, 2017 ; St. Pierre & Pillow, 2000 ). Feminist qualitative researchers should seek to complicate the question of what method and methodology mean when conducting feminist research (Lather, 1991 ), due to the feminist emphasis on reflexive and situated research methods (Hesse-Biber, 2012 ).

Examples of Feminist Qualitative Research in Education

A complete overview of the literature is not possible here, due to considerations of length, but the articles and books selected represent the various debates within feminist educational research. They also show how research preoccupations have changed over the course of feminist work in education. The literature review is divided into three broad categories: Power, canons, and gender; feminist pedagogies, curriculums, and classrooms; and teacher education, identities, and knowledge. Each section provides a broad overview of the literature to demonstrate the breadth of work using feminist theory, with some examples more deeply explicated to describe how feminist theories inform the scholarship.

Power, Canons, and Gender

The literature in this category contests disciplinary practices that are androcentric in both content and form, while asserting the value of using feminist knowledge to construct knowledge. The majority of the work was written in the 1980s and supported the creation of feminist ways of knowing, particularly via the creation of women’s studies programs or courses in existing departments that centered female voices and experiences.

Questioning the canon has long been a focus of feminist scholarship, as has the attempt to subvert its power in the disciplines. Bezucha ( 1985 ) focused on the ways that departments of history resist the inclusion of both women and feminism in the historical canon. Similarly, Miller ( 1985 ) discussed feminism as subversion when seeking to expand the canon of French literature in higher education.

Lauter and Dieterich ( 1972 ) examined a report by ERIC, “Women’s Place in Academe,” a collection of articles about the discrepancies by gender in jobs and tenure-track positions and the lack of inclusion of women authors in literature classes. They also found that women were relegated to “softer” disciplines and that feminist knowledge was not acknowledged as valid work. Culley and Portuges ( 1985 ) expanded the focus beyond disciplines to the larger structures of higher education and noted the varies ways that professors subvert from within their disciplines. DuBois et al. ( 1985 ) chronicled the development of feminist scholarship in the disciplines of anthropology, education, history, literature, and philosophy. They explained that the institutions of higher education often prevent feminist scholars from working across disciplines in an attempt to keep them separate. Raymond ( 1985 ) also critiqued the academy for not encouraging relationships across disciplines and offered the development of women’s, gender, and feminist studies as one solution to greater interdisciplinary work.

Parson ( 2016 ) examined the ways that STEM syllabi reinforce gendered norms in higher education. She specifically looked at eight syllabi from math, chemistry, biology, physics, and geology classes to determine how modal verbs showing stance, pronouns, intertextuality, interdiscursivity, and gender showed power relations in higher education. She framed the study through poststructuralist feminist critical discourse analysis to uncover “the ways that gendered practices that favor men are represented and replicated in the syllabus” (p. 103). She found that all the syllabi positioned knowledge as something that is, rather than something that can be co-constructed. Additionally, the syllabi also favored individual and masculine notions of what it means to learn by stressing the competitive and difficult nature of the classroom and content.

When reading newer work on feminism in higher education and the construction of knowledge, it is easy to feel that, while the conversations might have shifted somewhat, the challenge of conducting interdisciplinary feminist work in institutions of higher education remains as present as it was during the creation of women’s and gender studies departments. The articles all point to the fact that simply including women’s and marginalized voices in the academy does not erase or mitigate the larger issues of gender discrimination and androcentricity within the silos of the academy.

Feminist Pedagogies, Curricula, and Classrooms

This category of literature has many similarities to the previous one, but all the works focus more specifically on questions of curriculum and pedagogy. A review of the literature shows that the earliest conversations were about the role of women in academia and knowledge construction, and this selection builds on that work to emphasize the ways that feminism can influence the events within classes and expands the focus to more levels of education.

Rich ( 1985 ) explained that curriculum in higher education courses needs to validate gender identities while resisting patriarchal canons. Maher ( 1985 ) narrowed the focus to a critique of the lecture as a pedagogical technique that reinforces androcentric ways of learning and knowing. She called for classes in higher education to be “collaborative, cooperative, and interactive” (p. 30), a cry that still echoes across many college campuses today, especially from students in large lecture-based courses. Maher and Tetreault ( 1994 ) provided a collection of essays that are rooted in feminist classroom practice and moved from the classroom into theoretical possibilities for feminist education. Warren ( 1998 ) recommended using Peggy McIntosh’s five phases of curriculum development ( 1990 ) and extending it to include feminist pedagogies that challenge patriarchal ways of teaching. Exploring the relational encounters that exist in feminist classrooms, Sánchez-Pardo ( 2017 ) discussed the ethics of pedagogy as a politics of visibility and investigated the ways that democratic classrooms relate to feminist classrooms.

While all of the previously cited literature is U.S.–based, the next two works focus on the ways that feminist pedagogies and curriculum operate in a European context. Weiner ( 1994 ) used autobiography and narrative methodologies to provide an introduction to how feminism has influenced educational research and pedagogy in Britain. Revelles-Benavente and Ramos ( 2017 ) collected a series of studies about how situated feminist knowledge challenges the problems of neoliberal education across Europe. These two, among many European feminist works, demonstrate the range of scholarship and show the trans-Atlantic links between how feminism has been received in educational settings. However, much more work needs to be done in looking at the broader global context, and particularly by feminist scholars who come from non-Western contexts.

The following literature moves us into P–12 classrooms. DiGiovanni and Liston ( 2005 ) called for a new research agenda in K–5 education that explores the hidden curriculums surrounding gender and gender identity. One source of the hidden curriculum is classroom literature, which both Davies ( 2003 ) and Vandergrift ( 1995 ) discussed in their works. Davies ( 2003 ) used feminist ethnography to understand how children who were exposed to feminist picture books talked about gender and gender roles. Vandergrift ( 1995 ) presented a theoretical piece that explored the ways picture books reinforce or resist canons. She laid out a future research agenda using reader response theory to better comprehend how young children question gender in literature. Willinsky ( 1987 ) explored the ways that dictionary definitions reinforced constructions of gender. He looked at the definitions of the words clitoris, penis , and vagina in six school dictionaries and then compared them with A Feminist Dictionary to see how the definitions varied across texts. He found a stark difference in the treatment of the words vagina and penis ; definitions of the word vagina were treated as medical or anatomical and devoid of sexuality, while definitions of the term penis were linked to sex (p. 151).

Weisner ( 2004 ) addressed middle school classrooms and highlighted the various ways her school discouraged unconventional and feminist ways of teaching. She also brought up issues of silence, on the part of both teachers and students, regarding sexuality. By including students in the curriculum planning process, Weisner provided more possibilities for challenging power in classrooms. Wallace ( 1999 ) returned to the realm of higher education and pushed literature professors to expand pedagogy to be about more than just the texts that are read. She challenged the metaphoric dichotomy of classrooms as places of love or battlefields; in doing so, she “advocate[d] active ignorance and attention to resistances” (p. 194) as a method of subverting transference from students to teachers.

The works discussed in this section cover topics ranging from the place of women in curriculum to the gendered encounters teachers and students have with curriculums and pedagogies. They offer current feminist scholars many directions for future research, particularly in the arena of P–12 education.

Teacher Education, Identities, and Knowledge

The third subset of literature examines the ways that teachers exist in classrooms and some possibilities for feminist teacher education. The majority of the literature in this section starts from the premise that the teachers are engaged in feminist projects. The selections concerning teacher education offer critiques of existing heteropatriarchal normative teacher education and include possibilities for weaving feminism and feminist pedagogies into the education of preservice teachers.

Holzman ( 1986 ) explored the role of multicultural teaching and how it can challenge systematic oppression; however, she complicated the process with her personal narrative of being a lesbian and working to find a place within the school for her sexual identity. She questioned how teachers can protect their identities while also engaging in the fight for justice and equity. Hoffman ( 1985 ) discussed the ways teacher power operates in the classroom and how to balance the personal and political while still engaging in disciplinary curriculums. She contended that teachers can work from personal knowledge and connect it to the larger curricular concerns of their discipline. Golden ( 1998 ) used teacher narratives to unpack how teachers can become radicalized in the higher education classroom when faced with unrelenting patriarchal and heteronormative messages.

Extending this work, Bailey ( 2001 ) discussed teachers as activists within the classroom. She focused on three aspects of teaching: integrity with regard to relationships, course content, and teaching strategies. She concluded that teachers cannot separate their values from their profession. Simon ( 2007 ) conducted a case study of a secondary teacher and communities of inquiry to see how they impacted her work in the classroom. The teacher, Laura, explicitly tied her inquiry activities to activist teacher education and critical pedagogy, “For this study, inquiry is fundamental to critical pedagogy, shaped by power and ideology, relationships within and outside of the classroom, as well as teachers’ and students’ autochthonous histories and epistemologies” (Simon, 2007 , p. 47). Laura’s experiences during her teacher education program continued during her years in the classroom, leading her to create a larger activism-oriented teacher organization.

Collecting educational autobiographies from 17 college-level feminist professors, Maher and Tetreault ( 1994 ) worried that educators often conflated “the experience and values of white middle-class women like ourselves for gendered universals” (p. 15). They complicated the idea of a democratic feminist teacher, raised issues regarding the problematic ways hegemonic feminism flattens experience to that of just white women, and pushed feminist professors to pay particular attention to the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality when teaching.

Cheira ( 2017 ) called for gender-conscious teaching and literature-based teaching to confront the gender stereotypes she encountered in Portuguese secondary schools. Papoulis and Smith ( 1992 ) conducted summer sessions where teachers experienced writing activities they could teach their students. Conceptualized as an experiential professional development course, the article revolved around an incident where the seminar was reading Emily Dickinson and the men in the course asked the two female instructors why they had to read feminist literature and the conversations that arose. The stories the women told tie into Papoulis and Smith’s call for teacher educators to interrogate their underlying beliefs and ideologies about gender, race, and class, so they are able to foster communities of study that can purposefully and consciously address feminist inquiry.

McWilliam ( 1994 ) collected stories of preservice teachers in Australia to understand how feminism can influence teacher education. She explored how textual practices affect how preservice teachers understand teaching and their role. Robertson ( 1994 ) tackled the issue of teacher education and challenged teachers to move beyond the two metaphors of banking and midwifery when discussing feminist ways of teaching. She called for teacher educators to use feminist pedagogies within schools of education so that preservice teachers experience a feminist education. Maher and Rathbone ( 1986 ) explored the scholarship on women’s and girls’ educational experiences and used their findings to call for changes in teacher education. They argued that schools reinforce the notion that female qualities are inferior due to androcentric curriculums and ways of showing knowledge. Justice-oriented teacher education is a more recent iteration of this debate, and Jones and Hughes ( 2016 ) called for community-based practices to expand the traditional definitions of schooling and education. They called for preservice teachers to be conversant with, and open to, feminist storylines that defy existing gendered, raced, and classed stereotypes.

Bieler ( 2010 ) drew on feminist and critical definitions of dialogue (e.g., those by Bakhtin, Freire, Ellsworth, hooks, and Burbules) to reframe mentoring discourse in university supervision and dialogic praxis. She concluded by calling on university supervisors to change their methods of working with preservice teachers to “Explicitly and transparently cultivat[e] dialogic praxis-oriented mentoring relationships so that the newest members of our field can ‘feel their own strength at last,’ as Homer’s Telemachus aspired to do” (Bieler, 2010 , p. 422).

Johnson ( 2004 ) also examined the role of teacher educators, but she focused on the bodies and sexualities of preservice teachers. She explored the dynamics of sexual tension in secondary classrooms, the role of the body in teaching, and concerns about clothing when teaching. She explicitly worked to resist and undermine Cartesian dualities and, instead, explored the erotic power of teaching and seducing students into a love of subject matter. “But empowered women threaten the patriarchal structure of this society. Therefore, women have been acculturated to distrust erotic power” (Johnson, 2004 , p. 7). Like Bieler ( 2010 ), Johnson ( 2004 ) concluded that, “Teacher educators could play a role in creating a space within the larger framework of teacher education discourse such that bodily knowledge is considered along with pedagogical and content knowledge as a necessary component of teacher training and professional development” (p. 24). The articles about teacher education all sought to provoke questions about how we engage in the preparation and continuing development of educators.

Teacher identity and teacher education constitute how teachers construct knowledge, as both students and teachers. The works in this section raise issues of what identities are “acceptable” in the classroom, ways teachers and teacher educators can disrupt oppressive storylines and practices, and the challenges of utilizing feminist pedagogies without falling into hegemonic feminist practices.

Possibilities for Feminist Qualitative Research

Spivak ( 2012 ) believed that “gender is our first instrument of abstraction” (p. 30) and is often overlooked in a desire to understand political, curricular, or cultural moments. More work needs to be done to center gender and intersecting identities in educational research. One way is by using feminist qualitative methods. Classrooms and educational systems need to be examined through their gendered components, and the ways students operate within and negotiate systems of power and oppression need to be explored. We need to see if and how teachers are actively challenging patriarchal and heteronormative curriculums and to learn new methods for engaging in affirmative sabotage (Spivak, 2014 ). Given the historical emphasis on higher education, more work is needed regarding P–12 education, because it is in P–12 classrooms that affirmative sabotage may be the most necessary to subvert systems of oppression.

In order to engage in affirmative sabotage, it is vital that qualitative researchers who wish to use feminist theory spend time grappling with the complexity and multiplicity of feminist theory. It is only by doing this thought work that researchers will be able to understand the ongoing debates within feminist theory and to use it in a way that leads to a more equitable and just world. Simply using feminist theory because it may be trendy ignores the very real political nature of feminist activism. Researchers need to consider which theories they draw on and why they use those theories in their projects. One way of doing this is to explicitly think with theory (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012 ) at all stages of the research project and to consider which voices are being heard and which are being silenced (Gilligan, 2011 ; Spivak, 1988 ) in educational research. More consideration also needs to be given to non-U.S. and non-Western feminist theories and research to expand our understanding of education and schooling.

Paying close attention to feminist debates about method and methodology provides another possibility for qualitative research. The very process of challenging positivist research methods opens up new spaces and places for feminist qualitative research in education. It also allows researchers room to explore subjectivities that are often marginalized. When researchers engage in the deeply reflexive work that feminist research requires, it leads to acts of affirmative sabotage within the academy. These discussions create the spaces that lead to new visions and new worlds. Spivak ( 2006 ) once declared, “I am helpless before the fact that all my essays these days seem to end with projects for future work” (p. 35), but this is precisely the beauty of feminist qualitative research. We are setting ourselves and other feminist researchers up for future work, future questions, and actively changing the nature of qualitative research.

Acknowledgements

Dr. George Noblit provided the author with the opportunity to think deeply about qualitative methods and to write this article, for which the author is extremely grateful. Dr. Lynda Stone and Dr. Tanya Shields are thanked for encouraging the author’s passion for feminist theory and for providing many hours of fruitful conversation and book lists. A final thank you is owed to the author’s partner, Ben Skelton, for hours of listening to her talk about feminist methods, for always being a first reader, and for taking care of their infant while the author finished writing this article.

- Abajian, S. M. (2016). Documenting militarism: Challenges of researching highly contested practices within urban schools. Anthropology & Education Quarterly , 47 (1), 25–41.

- Abajian, S. M. , and Guzman, M. (2013). Moving beyond slogans: Possibilities for a more connected and humanizing “counter-recruitment” pedagogy in militarized urban schools. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing , 29 (2), 191–205.

- Allen, P. G. (1984). Who is your mother? Red roots of white feminism. Sinister Wisdom , 25 (Winter), 34–46.

- American Association of University Women . (1992). How schools shortchange girls: The AAUW report: A study of major findings on girls and education . Washington, DC.

- AAUW . (1999). Gender gaps: Where schools still fail our children . New York, NY: Marlowe.

- Bailey, C. (2001). Teaching as activism and excuse: A reconsideration of the theory−practice dichotomy. Feminist Teacher , 13 (2), 125–133.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Behar, R. , & Gordon, D. A. (Eds.). (1995). Women writing culture . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bezucha, R. J. (1985). Feminist pedagogy as a subversive activity. In M. Culley & C. Portuges (Eds.), Gendered subjects: The dynamics of feminist teaching (pp. 81–95). Boston, MA: Routledge.

- Bieler, D. (2010). Dialogic praxis in teacher preparation: A discourse analysis of mentoring talk. English Education , 42 (4), 391–426.

- Brown, K. D. (2011). Elevating the role of race in ethnographic research: Navigating race relations in the field. Ethnography and Education , 6 (1), 97–111.

- Calderon, D. (2016). Moving from damage-centered research through unsettling reflexivity. Anthropology & Education Quarterly , 47 (1), 5–24.

- Ceglowski, D. , & Makovsky, T. (2012) Duoethnography with children. Ethnography and Education , 7 (3), 283–295.

- Cheira, A. (2017). (Fostering) princesses that can stand on their own two feet: Using wonder tale narratives to change teenage gendered stereotypes in Portuguese EFL classrooms. In B. Revelles-Benavente & A. M. Ramos (Eds.), Teaching gender: Feminist pedagogy and responsibility in times of political crisis (pp. 146–162). London, U.K.: Routledge.

- Clifford, J. , & Marcus, G. (Eds.). (1986). Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Coffey, A. , & Delamont, S. (2000). Feminism and the classroom teacher: Research, praxis, and pedagogy . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color . Stanford Law Review , 43 (6), 1241–1299.

- Culley, M. , & Portuges, C. (Eds.). (1985). Gendered subjects: The dynamics of feminist teaching . Boston, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Davies, B. (2003). Frogs and snails and feminist tales: Preschool children and gender . Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Davies, B. (2014). Listening to children: Being and becoming . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Davies, B. (2016). Emergent listening. In N. K. Denzin & M. D. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry through a critical lens (pp. 73–84). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Davis, A. Y. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement . Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

- Denzin, N. K. , & Giardina, M. D. (Eds.). (2016). Qualitative inquiry through a critical lens . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Derrida, J. (2016). Of grammatology ( G. C. Spivak , Trans.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Digiovanni, L. W. , & Liston, D. D. (2005). Feminist pedagogy in the elementary classroom: An agenda for practice. Feminist Teacher , 15 (2), 123–131.

- Diller, A. , Houston, B. , Morgan, K. P. , & Ayim, M. (1996). The gender question in education: Theory, pedagogy, and politics . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- DuBois, E. C. , Kelly, G. P. , Kennedy, E. L. , Korsmeyer, C. W. , & Robinson, L. S. (1985). Feminist scholarship: Kindling in the groves of the academe . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Duncan-Andrade, J. M. , & Morrell, E. (2008). The art of critical pedagogy: Possibilities for moving from theory to practice in urban schools . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Ellsworth, E. (1989). Why doesn’t this feel empowering? Working through the repressive myths of critical pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review , 59 (3), 297–324.

- Evans, B. , & Spivak, G. C. (2016, July 13). When law is not justice. New York Times (online).

- Gabriel, S. L. , & Smithson, I. (1990). Gender in the classroom: Power and pedagogy . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gilligan, C. (2011). Joining the resistance . Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Golden, C. (1998). The radicalization of a teacher. In G. E. Cohee , E. Däumer , T. D. Kemp , P. M. Krebs , S. Lafky , & S. Runzo (Eds.), The feminist teacher anthology . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Gottesman, I. H. (2016). The critical turn in education: From Marxist critique to poststructuralist feminism to critical theories of race . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Greene, M. (1994). Postmodernism and the crisis of representation. English Education , 26 (4), 206–219.

- Haddix, M. , McArthur, S. A. , Muhammad, G. E. , Price-Dennis, D. , & Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2016). At the kitchen table: Black women English educators speaking our truths. English Education , 48 (4), 380–395.

- Hancock, E. (1989). The girl within . New York, NY: Fawcett Columbine.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies , 14 (3), 575–599.

- Harding, S. (1991). Whose science/Whose knowledge? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Harding, S. (Ed.). (2004). The feminist standpoint theory reader . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (Ed.). (2012). Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Hill Collins, P. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hoffman, N. J. (1985). Breaking silences: Life in the feminist classroom. In M. Culley & C. Portuges (Eds.), Gendered subjects: The dynamics of feminist teaching (pp. 147–154). Boston, MA: Routledge.

- Holzman, L. (1986). What do teachers have to teach? Feminist Teacher , 2 (3), 23–24.

- Jackson, A. , & Mazzei, L. (2009). Voice in qualitative inquiry: Challenging conventional, interpretive, and critical conceptions in qualitative research . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jackson, A. Y. , & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jackson, C. , Paechter, C. , & Renold, E. (2010). Girls and education 3–16: Continuing concerns, new agendas . Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press.

- Johnson, T. S. (2004). “It’s pointless to deny that that dynamic is there”: Sexual tensions in secondary classrooms. English Education , 37 (1), 5–29.

- Jones, S. , & Hughes, H. E. (2016). Changing the place of teacher education: Feminism, fear, and pedagogical paradoxes . Harvard Educational Review , 86 (2), 161–182.

- Kerkhoff, S. N. (2015). Dialogism: Feminist revision of argumentative writing instruction . Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice , 64 (1), 443–460.

- Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2016). Reconceptualizing qualitiative research: Methodologies without methodology . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Koro-Ljungberg, M. , Löytönen, T. , & Tesar, M. (Eds.). (2017). Disrupting data in qualitative inquiry: Entanglements with the post-critical and post-anthropocentric . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Kuby, C. R. , & Rucker, T. G. (2016). Go be a writer! Expanding the curricular boundaries of literacy learning with children . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Lather, P. (1991). Feminist research in education: Within/against . Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University Press.

- Lauter, N. A. , & Dieterich, D. (1972). “Woman’s place in academe”: An ERIC Report. English Education , 3 (3), 169–173.

- Levinson, B. A. (1998). (How) can a man do feminist ethnography of education? Qualitative Inquiry , 4 (3), 337–368.

- Love, B. L. (2017). A ratchet lens: Black queer youth, agency, hip hop, and the Black ratchet imagination . Educational Researcher , 46 (9), 539–547.

- Low, S. M. , & Merry, S. E. (2010). Engaged anthropology: Diversity and dilemmas. Current Anthropology 51 (S2), S203–S226.

- Maher, F. (1985). Classroom pedagogy and the new scholarship on women. In M. Culley & C. Portuges (Eds.), Gendered subjects: The dynamics of feminist teaching (pp. 29–48). Boston, MA: Routledge.

- Maher, F. A. , & Rathbone, C. H. (1986). Teacher education and feminist theory: Some implications for practice. American Journal of Education , 94 (2), 214–235.