The 10 Most Ridiculous Scientific Studies

I mportant news from the world of science: if you happen to suffer a traumatic brain injury, don’t be surprised if you experience headaches as a result. In other breakthrough findings: knee surgery may interfere with your jogging, alcohol has been found to relax people at parties, and there are multiple causes of death in very old people. Write the Nobel speeches, people, because someone’s going to Oslo!

Okay, maybe not. Still, every one of those not-exactly jaw-dropping studies is entirely real—funded, peer-reviewed, published, the works. And they’re not alone. Here—with their press release headlines unchanged—are the ten best from from science’s recent annals of “duh.”

Study shows beneficial effect of electric fans in extreme heat and humidity: You know that space heater you’ve been firing up every time the temperature climbs above 90º in August? Turns out you’ve been going about it all wrong. If you don’t have air conditioning, it seems that “fans” (which move “air” with the help of a cunning arrangement of rotating “blades”) can actually make you feel cooler. That, at least, was the news from a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) last February. Still to come: “Why Snow-Blower Use Declines in July.”

Study shows benefit of higher quality screening colonoscopies: Don’t you just hate those low-quality colonoscopies? You know, the ones when the doctor looks at your ears, checks your throat and pronounces, “That’s one fine colon you’ve got there, friend”? Now there’s a better way to go about things, according to JAMA, and that’s to be sure to have timely, high quality screenings instead. That may be bad news for “Colon Bob, Your $5 Colonoscopy Man,” but it’s good news for the rest of us.

Holding on to the blues: Depressed individuals may fail to decrease sadness: This one apparently came as news to the folks at the Association for Psychological Science and they’ve got the body of work to stand behind their findings. They’re surely the same scientists who discovered that short people often fail to increase inches, grouchy people don’t have enough niceness and folks who wear dentures have done a terrible job of hanging onto their teeth. The depression findings in particular are good news, pointing to exciting new treatments based on the venerable “Turn that frown upside down” method.

Quitting smoking after heart attack reduces chest pain, improves quality of life: Looks like you can say goodbye to those friendly intensive care units that used hand out packs of Luckies to post-op patients hankering for a smoke. Don’t blame the hospitals though, blame those buzz-kills folks at the American Heart Association who are responsible for this no-fun finding. Next in the nanny-state crosshairs: the Krispy Kreme booth at the diabetes clinic.

Older workers bring valuable knowledge to the job: Sure they bring other things too: incomprehensible jokes, sensible shoes, the last working Walkman in captivity. But according to a study in the Journal of Applied Psychology , they also bring what the investigators call “crystallized knowledge,” which comes from “knowledge born of experience.” So yes, the old folks in your office say corny things like “Show up on time,” “Do an honest day’s work,” and “You know that plan you’ve got to sell billions of dollars worth of unsecured mortgages, bundle them together, chop them all up and sell them to investors? Don’t do that.” But it doesn’t hurt to humor them. They really are adorable sometimes.

Being homeless is bad for your health: Granted, there’s the fresh air, the lean diet, the vigorous exercise (no sitting in front of the TV for you!) But living on the street is not the picnic it seems. Studies like the one in the Journal of Health Psychology show it’s not just the absence of a fixed address that hurts, but the absence of luxuries like, say, walls and a roof. That’s especially true in winter—and spring, summer and fall too, follow-up studies have found. So quit your bragging, homeless people. You’re no healthier than the rest of us.

The more time a person lives under a democracy, the more likely she or he is to support democracy: It’s easy to fall for a charming strong-man—that waggish autocrat who promises you stability, order and no silly distractions like civil liberties and an open press. Soul-crushing annihilation of personal freedoms? Gimme’ some of that, big boy. So it came as a surprise that a study in Science found that when you give people even a single taste of the whole democracy thing, well, it’s like what they say about potato chips, you want to eat the whole bag. But hey, let’s keep this one secret. Nothing like a peevish dictator to mess up a weekend.

Statistical analysis reveals Mexican drug war increased homicide rates: That’s the thing about any war—the homicide part is kind of the whole point. Still, as a paper in The American Statistician showed, it’s always a good idea to crunch the numbers. So let’s run the equation: X – Y = Z, where X is the number of people who walked into the drug war alive, Y is the number who walked out and Z is, you know, the dead guys. Yep, looks like it adds up. (Don’t forget to show your work!)

Middle-aged congenital heart disease survivors may need special care: Sure, but they may not, too. Yes you could always baby them, like the American Heat Association recommends. But you know what they say: A middle-aged congenital heart disease survivor who gets special care is a lazy middle-aged congenital heart disease survivor. Heck, when I was a kid, our middle-aged congenital heart disease survivors worked for their care—and they thanked us for it too. This is not the America I knew.

Scientists Discover a Difference Between the Sexes: Somewhere, in the basement warrens of Northwestern University, dwell the scientists who made this discovery—androgynous beings, reproducing by cellular fission, they toiled in darkness, their light-sensitive eye spots needing only the barest illumination to see. Then one day they emerged blinking into the light, squinted about them and discovered that the surface creatures seemed to come in two distinct varieties. Intrigued, they wandered among them—then went to a kegger and haven’t been seen since. Spring break, man; what are you gonna’ do?

Read about changes to Time.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What Makes a Friendship Last Forever?

- How to Read Political Polls Like a Pro

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- How ‘Friendshoring’ Made Southeast Asia Pivotal to the AI Revolution

- Column: Your Cynicism Isn’t Helping Anybody

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 02 June 2022

Tolerating bad health research: the continuing scandal

- Stefania Pirosca 1 ,

- Frances Shiely 2 , 3 ,

- Mike Clarke 4 &

- Shaun Treweek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7239-7241 1

Trials volume 23 , Article number: 458 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

24 Citations

421 Altmetric

Metrics details

At the 2015 REWARD/EQUATOR conference on research waste, the late Doug Altman revealed that his only regret about his 1994 BMJ paper ‘The scandal of poor medical research’ was that he used the word ‘poor’ rather than ‘bad’. But how much research is bad? And what would improve things?

We focus on randomised trials and look at scale, participants and cost. We randomly selected up to two quantitative intervention reviews published by all clinical Cochrane Review Groups between May 2020 and April 2021. Data including the risk of bias, number of participants, intervention type and country were extracted for all trials included in selected reviews. High risk of bias trials was classed as bad. The cost of high risk of bias trials was estimated using published estimates of trial cost per participant.

We identified 96 reviews authored by 546 reviewers from 49 clinical Cochrane Review Groups that included 1659 trials done in 84 countries. Of the 1640 trials providing risk of bias information, 1013 (62%) were high risk of bias (bad), 494 (30%) unclear and 133 (8%) low risk of bias. Bad trials were spread across all clinical areas and all countries. Well over 220,000 participants (or 56% of all participants) were in bad trials. The low estimate of the cost of bad trials was £726 million; our high estimate was over £8 billion.

We have five recommendations: trials should be neither funded (1) nor given ethical approval (2) unless they have a statistician and methodologist; trialists should use a risk of bias tool at design (3); more statisticians and methodologists should be trained and supported (4); there should be more funding into applied methodology research and infrastructure (5).

Conclusions

Most randomised trials are bad and most trial participants will be in one. The research community has tolerated this for decades. This has to stop: we need to put rigour and methodology where it belongs — at the centre of our science.

Peer Review reports

At the 2015 REWARD/EQUATOR conference on research waste, the late Doug Altman revealed that his only regret about his 1994 BMJ paper ‘The scandal of poor medical research’ [ 1 ] was that he used the word ‘poor’ rather than ‘bad’. Towards the end of his life, Doug had considered writing a sequel with a title that included not only ‘bad’ but ‘continuing’ [ 2 ].

That ‘continuing’ is needed should worry all of us. Ben Van Calster and colleagues have recently highlighted the paradox that science consistently undervalues methodology that would underpin good research [ 3 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has generated an astonishing amount of research and some of it has transformed the way the virus is managed and treated. But we expect that much COVID-19 research will be bad because much of health research in general is bad [ 3 ]. This was true in 1994 and it remains true in 2021 because how research is done allows it to be so. Research waste seems to be baked-in to the system.

In this commentary, we do not intend to list specific examples of research waste. Rather, we want to talk about scale, participants and money and then finish with five recommendations. All of the latter will look familiar — Doug Altman and others [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] have suggested them many times — but we hope our numbers on scale, participants and money will lend the recommendations an urgency they have always deserved but never had.

So, how much research is bad?

That research waste is common is not in doubt [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] but we wanted to put a number on something more specific: how much is bad research that is not just wasteful but which we could have done without and lost little or nothing? Rather than trying to tackle all of health research, we have chosen to focus on randomised trials because that is the field we know best and, in addition, they play a central role in decisions regarding the treatments that are offered to patients.

With this in mind, we aimed to estimate the proportion of trials that are bad, how many participants were involved and how much money was spent on them.

Selecting a cohort of trials

We used systematic reviews as our starting point because these bodies of trial evidence often underpin clinical practice through guideline recommendations and policy. We specifically chose Cochrane systematic reviews because they are standardised, high-quality systematic reviews. We were only interested in recent reviews because these represent the most up-to-date bodies of evidence.

Moreover, Cochrane reviews record the review authors’ judgements about the risk of bias of included trials, in other words, they assess the extent to which the trial’s findings can be believed [ 9 ]. We consider that to be a measure of how good or bad a trial is. Cochrane has three categories of overall risk of bias: high, uncertain and low. We considered a high risk of bias trial to be bad, a low risk of bias trial to be good and an uncertain risk of bias trial to be exactly that, uncertain. We did not attempt to look at which type (or ‘domain’) of bias drove the overall assessment. We share the view given in the Cochrane Handbook (Chapter 8) [ 9 ] that the overall risk of bias is the least favourable assessment across the domains of bias. If one domain is high risk, then the overall assessment is high risk. No domain is more or less important than any other and if there is a high risk of bias in even just one domain, this calls into question the validity of the trial’s findings.

We used the list randomiser at random.org to randomly select two reviews published between May 2020 and April 2021 from each of the 53 clinical Cochrane Review Groups. To be included, a review had to consider intervention effects rather than being a qualitative review or a review of reviews. We then extracted basic information (our full dataset is at https://osf.io/dv6cw/?view_only=0becaacc45884754b09fd1f54db0c495 ) about every included trial in each review, including the overall risk of bias assessment. Our aim was to make no judgements about the risk of bias ourselves but to take what the review authors had provided. We did not contact the review or trial authors for additional information. Extracted data were put into Excel spreadsheets, one for each Cochrane Review Group.

To answer our question about the proportion of bad trials and how many participants were in them, we used simple counts across reviews and trials. Counts across spreadsheets were done using R and our code is at https://osf.io/dv6cw/?view_only=0becaacc45884754b09fd1f54db0c495 . To estimate how much money might have been spent on the trials, we used three estimates of the cost-per-participant to give a range of possible values for total spend:

Estimate 1: An estimate of the cost-per-participant for the UK’s National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) Programme trials of 2987 GBP. This was calculated based on a median cost per NIHR HTA trial of 1,433,978 GBP for 2011–2016 [ 10 ] and a median final recruitment target for NIHR HTA trials of 480 for 2004–2016 [ 11 ].

Estimate 2: The median cost-per-participant of 41,413 USD found for pivotal clinical benefit trials supporting the US approval of new therapeutic agents, 2015–2017 [ 12 ].

Estimate 3: The 2012 average cost-per-participant for UK trials of 9758 EUR found by Europe Economics [ 13 ].

These estimates were all converted into GBP using https://www.currency-converter.org.uk to get the exchange rate on 1st January in the latest year of trials covered by the estimate (i.e. 2017 for E2 and 2012 for E3). These were then all converted to 2021 GBP on 11 August 2021 using https://www.inflationtool.com , making E1 £3,256, E2 £35,918 and E3 £9,382. We acknowledge that these are unlikely to be exact for any given trial in our sample, but they were intended to give ballpark average figures to promote discussion.

Scale, participants and money

We extracted data for 1659 randomised trials spread across 96 reviews from 49 of the 53 clinical Cochrane Review Groups. The remaining four Review Groups published no eligible reviews in our time period. The 96 included reviews involved 546 review authors. Trials in 84 countries, as well as 193 multinational trials, are included. Risk of bias information was not available for 19 trials, meaning our risk of bias sample is 1640 trials. Almost all reviews (94) exclusively used Cochrane’s original risk of bias tool (see Supplementary File 1 ) rather than the new Risk of Bias tool (version 2.0) [ 14 ]. Cochrane RoB 1.0 has six domains of bias (sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias), while RoB 2.0 has five domains (randomisation process; assignment and adherence to intervention; incomplete outcome data; outcome measurement; selective reporting). Where the old tool was used, we used review authors’ assessment of the overall risk of bias. For the two reviews that used Risk of Bias 2, we did not make individual risk of bias judgements for domains, but we did take a view on the overall risk of bias if the review authors did not do this. We did this by looking across the individual domains and making a choice of high, uncertain or low overall risk of bias based on the number of individual domains falling into each category. This was a judgement; we did not use a hard-and-fast rule. We had to do this for 40 trials.

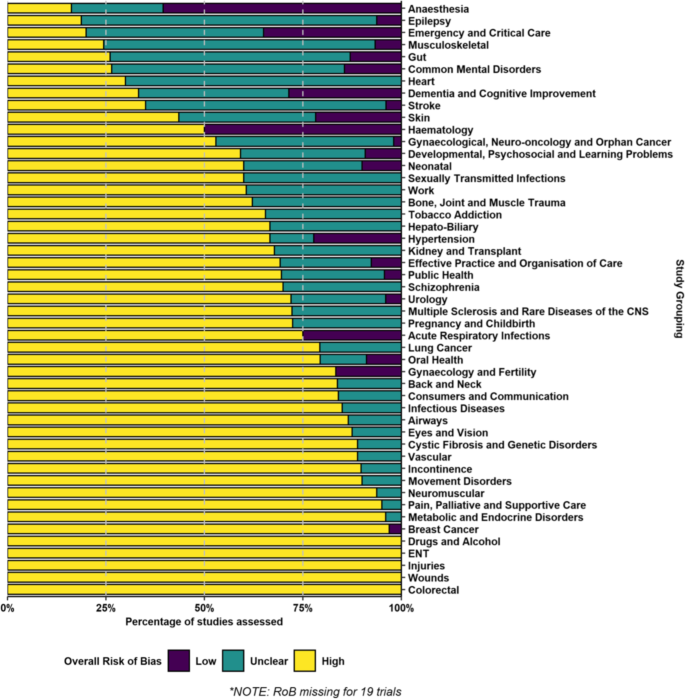

The majority of trials (1013, or 62%) were high risk of bias (Table 1 ). These trials were spread across all 49 Cochrane Review Groups and over half of the Groups (28, or 57%) had zero low risk of bias trials included in the reviews we randomly selected. The clinical area covered by the Anaesthesia Review Group had the highest proportion of low risk of bias trials at 60% but this group included 19 trials with no risk of bias information (see Fig. 1 ).

Risk of bias for included trials in randomly selected systematic reviews published between May 2020 and April 2021 by 49 Cochrane Review Groups

Some of the 84 countries in our sample contributed very few trials but Table 2 shows risk of bias data for the 17 countries that contributed 20 or more trials, as well as for multinational trials. The percentage of a country’s trials that were judged as low risk of bias reached double figures for multinational trials (23%) and five individual countries: Australia (10%), France (13%), India (10%), Japan (10%) and the UK (11%). The full country breakdown is given in Supplementary File 2 .

Participants

The 1659 included trials involved a total of 398,410 participants. The majority of these (222,850, or 56%) were in high risk of bias trials (Table 1 ).

Table 3 shows estimates for the amount of money spent on trials in each of the three risk of bias categories.

Using our low estimate for cost-per-participant (estimate 1 from NIHR HTA trials), we get an estimated spend of £726 million on high risk of bias trials. Our high estimate (estimate 2 from USA drug approval trials) gives an equivalent figure of over £8 billion. Based on an annual spend of £76 million for the UK’s NIHR HTA programme [ 15 ], the first figure, our lowest estimate, would be sufficient to fund the programme for almost a decade, while the second figure would fund it for over a century.

While looking at scale, participants and money, we made a few other secondary observations. To avoid distracting attention from our main points, we present these observations in Supplementary File 3 .

Bad trials — ones where we have little confidence in the results — are not just common, they represent the majority of trials across all clinical areas in all countries. Over half of all trial participants will be in one. Our estimates suggest that the money spent on these bad trials would fund the UK’s largest public funder of trials for anything between a decade and a century. It is a wide range but either way, it is a lot of money. Had our random selection produced a different set of reviews, or we had assessed all those published in the last 1, 5, 10 or 20 years, we have no reason to believe that the headline result would have been different. Put simply, most randomised trials are bad.

Despite this, we think our measure of bad is actually conservative because we have only considered the risk of bias. We have not attempted to judge whether trials asked important research questions, whether they involved the right participants and whether their outcomes were important to decision-makers such as patients and health professionals nor have we attempted to comment on the many other decisions that affect the usefulness of a trial [ 16 , 17 ]. In short, the picture our numbers paint is undoubtedly gloomy, but the reality is probably worse.

Five recommendations for change

Plenty of ideas have been suggested about what must change [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ], but we propose just five here because the scale of the problem is so great that providing focus might avoid being overwhelmed into inaction. We think these five recommendations, if implemented, would reduce the number of bad trials and could do so quite quickly.

Recommendation 1: do not fund a trial unless the trial team contains methodological and statistical expertise

Doing trials is a team sport. These teams need experienced methodologists and statisticians. We do not know how many trials fail to involve experienced methodologists and statisticians but we expect it to be a high proportion given the easily avoidable design errors seen in so many trials. It is hard to imagine doing, say, bowel surgery without involving people who have been trained in, and know how to do, bowel surgery. Sadly, the same does not seem to be true for trial design and statistical analysis of trial data. Our colleague Darren Dahly, a trial statistician, neatly captured the problem in a series of ironic tweets sent at the end of 2020:

These raise a smile but make a very serious point: we would not tolerate statisticians doing surgery so why do we tolerate the reverse? Clearly, this is not about surgeons, it is about not having the expertise needed to do the job properly.

Recommendation 2: do not give ethical approval for a trial unless the trial team contains methodological and statistical expertise

As for recommendation 1, but for ethical approval. All trials need ethical approval and the use of poor methods should be seen as an ethical concern [ 3 ]. No patient or member of the public should be in a bad trial and ethical committees, like funders, have a duty to stop this happening. Ethics committees should always consider whether there is adequate methodological and statistical expertise within the trial team. Indeed, we think public and patient contributors on ethics committees should routinely ask the question ‘Who is the statistician and who is the methodologist?’ and if the answer is unsatisfactory, ethical approval is not awarded until a name can be put against these roles.

Recommendation 3: use a risk of bias tool at trial design

This is the simplest of our recommendations. Risk of bias tools were developed to support the interpretation of trial results in systematic reviews. However, as Yordanov and colleagues wrote in 2015 [ 5 ], by then the horse has bolted and nothing can be changed. They considered 142 high risk of bias trials and found the four most common methodological problems to be exclusion of patients from analysis (50 trials, 35%), lack of blinding with a patient-reported outcome (27 trials, 19%), lack of blinding when comparing a non-drug treatment to nothing (23 trials,16%) and poor methods to deal with missing data (22 trials, 15%). They judged the first and last of these to be easy to fix at the design stage, while the two blinding problems were more difficult but not impossible to deal with. Sadly, trial teams themselves had not addressed any of these problems.

Applying a risk of bias tool at the trial design phase, having the methodological and statistical expertise to correctly interpret the results and then making any necessary changes to the trial, would help to avoid some of the problems highlighted by others [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] in the past and which we have found to be very common.

Applying a risk of bias tool at the trial design phase, having the methodological and statistical expertise to correctly interpret the results and then making any necessary changes to the trial, would help to avoid some of the problems we and others [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] highlight. Funders could ask to see the completed risk of bias tool, as could ethics committees. No trial should be high risk of bias.

Recommendation 4: train and support more methodologists and statisticians

Recommendations 1, 2 and 3 all lead to a need for more methodologists and statisticians. This has a cost but it would probably be much less than the money wasted on bad trials. See recommendation 5.

Recommendation 5: put more money into applied methodology research and supporting infrastructure

Methodology research currently runs mostly on love not money. This seems odd when over 60% of trials are so methodologically flawed we cannot believe their results and we are uncertain whether we should believe the results of another 30%.

In 2015, David Moher and Doug Altman proposed that 0.1% of funders’ and publishers’ budgets could be set aside for initiatives to reduce waste and improve the quality, and thus value, of research publications [ 6 ]. That was for publications but the same could be done for trials, although we would suggest a figure closer to 10% of funders’ budgets. All organisations that fund trials should also be funding applied work to improve trial methodology, including supporting the training of more methodologists and statisticians. There should also be funding mechanisms to ensure methodology knowledge is effectively disseminated and implemented. Dissemination is a particular problem and the UK’s only dedicated methodology funder, the Medical Research Council-NIHR ‘Better Methods, Better Research’ Panel, acknowledges this in its Programme Aims [ 18 ].

Implementing these five recommendations will require effort and investment but doing nothing is not an option that anyone should accept. We have shown that 220,850 people had been enrolled in trials judged to be so methodologically flawed that we can have little confidence in their results. A further 127,290 people had joined trials where it is unclear whether we should believe the results. These numbers represent 88% of all trial participants in our sample. This is a betrayal of those participants’ hopes, goodwill and time. Even our lowest cost-per-participant estimate would suggest that more than £1billion was spent on these bad and possibly bad trials.

The question for everyone associated with designing, funding and approving trials is how many good trials never happen because bad ones are done instead? The cost of this research waste is not only financial. Randomised trials have the potential to improve health and wellbeing, change lives for the better and support economies through healthier populations. But poor evidence leads to poor decisions [ 19 ]. Society will only see the potential benefits of randomised trials if these studies are good, and, at the moment, most are not.

In this study, we have concentrated on risk of bias. What makes our results particularly troubling is that the changes needed to move a trial from high risk of bias to low risk of bias are often simple and cheap. However, this is also positive in relation to changing what will happen in the future. For example, Yordanov and colleagues estimated that easy methodological adjustments at the design stage would have made important improvements to 42% (95% confidence interval = 36 to 49%) of trials with risk of bias concerns [ 5 ]. Their explanation for these adjustments not being made in the trials was a lack of input from methodologists and statisticians at the trial planning stage combined with insufficient knowledge of research methods among the trial teams. If we were to ask a statistician to operate on a patient, we would rightly fear for the patient: proposing that a trial is designed and run without research methods expertise should induce the same fear.

In 2009, Iain Chalmers and Paul Glasziou estimated that 85% of research spending is wasted due to, among other things, poor design and incomplete reporting [ 7 ]. Over a decade later, our estimate is that 88% of trial spending is wasted. Without addressing the fundamental problem of trials being done by people ill-equipped to do them, a similar study a decade from now will once again find that the majority of trials across all clinical areas in all countries are bad.

Our work, and that of others before us [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ], makes clear that a large amount of the money we put into trials globally is being wasted. Some of that money should be repurposed to fund our five recommendations. This may well lead to fewer trials overall but it would generate more good trials and mean that a greater proportion of trial data is of the high quality needed to support and improve patient and public health.

That so much research, and so many trials, is and are bad is indeed a scandal. That it continues decades after others highlighted the problem is a bigger scandal. Even the tiny slice of global research featured in our study describes trials that involved hundreds of thousands of people and cost hundreds of millions of pounds, but which led to little or no useful information.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a time for many things, including reflection. As many countries start to look to what can be learnt, all of us connected with trials should put rigour and methodology where it belongs — at the centre of our science. We think our five recommendations are a good place to start.

To quote Doug Altman ‘We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons’ [ 1 ]. Quite so.

Availability of data and materials

All our data are available at https://osf.io/dv6cw/?view_only=0becaacc45884754b09fd1f54db0c495 .

Abbreviations

British Medical Journal

Coronavirus disease 2019

British Pound Sterling

Health Technology Assessment

National Institute for Health Research

United Kingdom

United States of America

United States Dollar

Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical research. BMJ. 1994;308:283.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Matthews R, Chalmers I, Rothwell P. Douglas G Altman: statistician, researcher, and driving force behind global initiatives to improve the reliability of health research. BMJ. 2018;362:k2588.

Article Google Scholar

Van Calster B, Wynants L, Riley RD, van Smeden M, Collins GS. Methodology over metrics: current scientific standards are a disservice to patients and society. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;S0895-4356(21)00170-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.05.018 .

Glasziou P, Chalmers IC. Research waste is still a scandal—an essay by Paul Glasziou and Iain Chalmers. MJ. 2018;363:k4645.

Yordanov Y, Dechartres A, Porcher R, Boutron I, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Avoidable waste of research related to inadequate methods in clinical trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h809.

Moher D, Altman DG. Four proposals to help improve the medical research literature. PLoS Med. 2015;12(9):e1001864. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001864 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet . 2009;374(9683):86–9.

Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, Dirnagl U, Chalmers I, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):101–4.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021); 2021. (Chapters 7 and 8) Cochrane, Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Google Scholar

Chinnery F, Bashevoy G, Blatch-Jones A, et al. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) health technology assessment (HTA) Programme research funding and UK burden of disease. Trials. 2018;19:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2489-7 .

Walters SJ, Bonacho dos Anjos Henriques-Cadby I, Bortolami O, et al. Recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: a review of trials funded and published by the United Kingdom Health Technology Assessment Programme. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015276 .

Moore TJ, Heyward J, Anderson G, et al. Variation in the estimated costs of pivotal clinical benefit trials supporting the US approval of new therapeutic agents, 2015–2017: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e038863. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038863 .

Hawkes N. UK must improve its recruitment rate in clinical trials, report says. BMJ. 2012;345:e8104. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8104 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366(l4898). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898 .

Williams H. The NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme: Research needed by the NHS. https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/nihr-health-technology-assessment-programme-nhs/85065/ [Accessed 11/10/2021].

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383:156–65.

Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:166–75.

MRC-NIHR Better Methods, Better Research. Programme Aims. https://mrc.ukri.org/funding/science-areas/better-methods-better-research/overview/#aims [Accessed 30/9/2021].

Heneghan C, Mahtani KR, Goldacre B, Godlee F, Macdonald H, Jarvies D. Evidence based medicine manifesto for better healthcare: a response to systematic bias, wastage, error and fraud in research underpinning patient care. Evid Based Med Royal Soc Med. 2017;22:120–2.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Brendan Palmer for helping SP with R coding and Darren Dahly for confirming that he was happy for us to use his tweets. The Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, receives core funding from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates. This work was done as part of the Trial Forge initiative to improve trial efficiency ( https://www.trialforge.org ).

This work was funded by Ireland’s Health Research Board through the Trial Methodology Research Network (HRB-TMRN) as a summer internship for SP.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen, AB25 2ZD, UK

Stefania Pirosca & Shaun Treweek

Trials Research and Methodologies Unit, HRB Clinical Research Facility, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Frances Shiely

School of Public Health, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Northern Ireland Methodology Hub, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK

Mike Clarke

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ST had the original idea for the work. ST, FS and MC designed the study. SP identified reviews and trials, extracted data and did the analysis, in discussion with ST and FS. ST and SP wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to further drafts. All authors approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shaun Treweek .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

ST is an Editor-in-Chief of Trials . MC, FS and ST are actively involved in initiatives to improve the quality of trials and all seek funding to support these initiatives and therefore have an interest in seeing funding for trial methodology increased. SP has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

The Cochrane Collaboration’s ‘old’ tool for assessing risk of bias.

Additional file 2.

Risk of bias data for all countries in our sample.

Additional file 3.

Additional observations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pirosca, S., Shiely, F., Clarke, M. et al. Tolerating bad health research: the continuing scandal. Trials 23 , 458 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06415-5

Download citation

Received : 26 November 2021

Accepted : 18 May 2022

Published : 02 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06415-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Randomised trials

- Research waste

- Risk of bias

- Statisticians

- Methodologists

ISSN: 1745-6215

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

12 reasons research goes wrong.

FIXING THE NUMBERS Massaging data, small sample sizes and other issues can affect the statistical analyses of studies and distort the results, and that's not all that can go wrong.

Justine Hirshfeld/ Science News

Share this:

By Tina Hesman Saey

January 13, 2015 at 2:23 pm

For more on reproducibility in science, see SN’s feature “ Is redoing scientific research the best way to find truth? “

Barriers to research replication are based largely in a scientific culture that pits researchers against each other in competition for scarce resources. Any or all of the factors below, plus others, may combine to skew results.

Pressure to publish

Research funds are tighter than ever and good positions are hard to come by. To get grants and jobs, scientists need to publish, preferably in big-name journals. That pressure may lead researchers to publish many low-quality studies instead of aiming for a smaller number of well-done studies. To convince administrators and grant reviewers of the worthiness of their work, scientists have to be cheerleaders for their research; they may not be as critical of their results as they should be.

Impact factor mania

For scientists, publishing in a top journal — such as Nature , Science or Cell — with high citation rates or “impact factors” is like winning a medal. Universities and funding agencies award jobs and money disproportionately to researchers who publish in these journals. Many researchers say the science in those journals isn’t better than studies published elsewhere, it’s just splashier and tends not to reflect the messy reality of real-world data. Mania linked to publishing in high-impact journals may encourage researchers to do just about anything to publish there, sacrificing the quality of their science as a result.

Tainted cultures

Experiments can get contaminated and cells and animals may not be as advertised. In hundreds of instances since the 1960s, researchers misidentified cells they were working with. Contamination led to the erroneous report that the XMRV virus causes chronic fatigue syndrome, and a recent report suggests that bacterial DNA in lab reagents can interfere with microbiome studies.

Do the wrong kinds of statistical analyses and results may be skewed. Some researchers accuse colleagues of “p-hacking,” massaging data to achieve particular statistical criteria. Small sample sizes and improper randomization of subjects or “blinding” of the researchers can also lead to statistical errors. Data-heavy studies require multiple convoluted steps to analyze, with lots of opportunity for error. Researchers can often find patterns in their mounds of data that have no biological meaning.

Sins of omission

To thwart their competition, some scientists may leave out important details. One study found that 54 percent of research papers fail to properly identify resources, such as the strain of animals or types of reagents or antibodies used in the experiments. Intentional or not, the result is the same: Other researchers can’t replicate the results.

Biology is messy

Variability among and between people, animals and cells means that researchers never get exactly the same answer twice. Unknown variables abound and make replicating in the life and social sciences extremely difficult.

Peer review doesn’t work

Peer reviewers are experts in their field who evaluate research manuscripts and determine whether the science is strong enough to be published in a journal. A sting conducted by Science found some journals that don’t bother with peer review, or use a rubber stamp review process. Another study found that peer reviewers aren’t very good at spotting errors in papers. A high-profile case of misconduct concerning stem cells revealed that even when reviewers do spot fatal flaws, journals sometimes ignore the recommendations and publish anyway ( SN: 12/27/14, p. 25 ).

Some scientists don’t share

Collecting data is hard work and some scientists see a competitive advantage to not sharing their raw data. But selfishness also makes it impossible to replicate many analyses, especially those involving expensive clinical trials or massive amounts of data.

Research never reported

Journals want new findings, not repeats or second-place finishers. That gives researchers little incentive to check previously published work or to try to publish those findings if they do. False findings go unchallenged and negative results — ones that show no evidence to support the scientist’s hypothesis — are rarely published. Some people fear that scientists may leave out important, correct results that don’t fit a given hypothesis and publish only experiments that do.

Poor training produces sloppy scientists

Some researchers complain that young scientists aren’t getting proper training to conduct rigorous work and to critically evaluate their own and others’ studies.

Mistakes happen

Scientists are human, and therefore, fallible. Of 423 papers retracted due to honest error between 1979 and 2011, more than half were pulled because of mistakes, such as measuring a drug incorrectly.

Researchers who make up data or manipulate it produce results no one can replicate. However, fraud is responsible for only a tiny fraction of results that can’t be replicated.

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

A new book tackles AI hype – and how to spot it

A fluffy, orange fungus could transform food waste into tasty dishes

‘Turning to Stone’ paints rocks as storytellers and mentors

Old books can have unsafe levels of chromium, but readers’ risk is low

Astronauts actually get stuck in space all the time

Scientists are getting serious about UFOs. Here’s why

‘Then I Am Myself the World’ ponders what it means to be conscious

Twisters asks if you can 'tame' a tornado. We have the answer

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- The scandal of poor...

The scandal of poor medical research

Linked opinion.

Richard Smith: Medical research—still a scandal

- Related content

- Peer review

We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons

What should we think about a doctor who uses the wrong treatment, either wilfully or through ignorance, or who uses the right treatment wrongly (such as by giving the wrong dose of a drug)? Most people would agree that such behaviour was unprofessional, arguably unethical, and certainly unacceptable.

What, then, should we think about researchers who use the wrong techniques (either wilfully or in ignorance), use the right techniques wrongly, misinterpret their results, report their results selectively, cite the literature selectively, and draw unjustified conclusions? We should be appalled. Yet numerous studies of the medical literature, in both general and specialist journals, have shown that all of the above phenomena are common. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 This is surely a scandal.

When I tell friends outside medicine that many papers published in medical journals are misleading because of methodological weaknesses they are rightly shocked. Huge sums of money are spent annually on research that is seriously flawed through the use of inappropriate designs, unrepresentative samples, small samples, incorrect methods of analysis, and faulty interpretation. Errors are so varied that a whole book on the topic, 7 valuable as it is, is not comprehensive; in any case, many of those who make the errors are unlikely to read it.

Why are errors so common? Put simply, much poor research arises because researchers feel compelled for career reasons to carry out research that they are ill equipped to perform, and nobody stops them. Regardless of whether a doctor intends to pursue a career in research, he or she is usually expected to carry out some research with the aim of publishing several papers. The length of a list of publications is a dubious indicator of ability to do good research; its relevance to the ability to be a good doctor is even more obscure. A common argument in favour of every doctor doing some research is that it provides useful experience and may help doctors to interpret the published research of others. Carrying out a sensible study, even on a small scale, is indeed useful, but carrying out an ill designed study in ignorance of scientific principles and getting it published surely teaches several undesirable lessons.

In many countries a research ethics committee has to approve all research involving patients. Although the Royal College of Physicians has recommended that scientific criteria are an important part of the evaluation of research proposals, 8 few ethics committees in Britain include a statistician. Indeed, many ethics committees explicitly take a view of ethics that excludes scientific issues. Consequently, poor or useless studies pass such review even though they can reasonably be considered to be unethical. 9

The effects of the pressure to publish may be seen most clearly in the increase in scientific fraud, 10 much of which is relatively minor and is likely to escape detection. There is nothing new about the message of data or of data torture, as it has recently been called 11 - Charles Babbage described its different forms as long ago as 1830. 12 The temptation to behave dishonestly is surely far greater now, when all too often the main reason for a piece of research seems to be to lengthen a researcher's curriculum vitae. Bailar suggested that there may be greater danger to the public welfare from statistical dishonesty than from almost any other form of dishonesty. 13

Evaluation of the scientific quality of research papers often falls to statisticians. Responsible medical journals invest considerable effort in getting papers refereed by statisticians; however, few papers are rejected solely on statistical grounds. 14 Unfortunately, many journals use little or no statistical refereeing - bad papers are easy to publish.

Statistical refereeing is a form of fire fighting. The time spent refereeing medical papers (often for little or no reward) would be much better spent in education and in direct participation in research as a member of the research team. There is, though, a serious shortage of statisticians to teach and, especially, to participate in research. 15 Many people think that all you need to do statistics is a computer and appropriate software. This view is wrong even for analysis, but it certainly ignores the essential consideration of study design, the foundations on which research is built. Doctors need not be experts in statistics, but they should understand the principles of sound methods of research. If they can also analyse their own data, so much the better. Amazingly, it is widely considered acceptable for medical researchers to be ignorant of statistics. Many are not ashamed (and some seem proud) to admit that they don't know anything about statistics.

The poor quality of much medical research is widely acknowledged, yet disturbingly the leaders of the medical profession seem only minimally concerned about the problem and make no apparent efforts to find a solution. Manufacturing industry has come to recognise, albeit gradually, that quality control needs to be built in from the start rather than the failures being discarded, and the same principles should inform medical research. The issue here is not one of statistics as such. Rather it is a more general failure to appreciate the basic principles underlying scientific research, coupled with the “publish or perish” climate.

As the system encourages poor research it is the system that should be changed. We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons. Abandoning using the number of publications as a measure of ability would be a start.

- Pocock SJ ,

- Hughes MD ,

- Clemens J ,

- Gotzsche PC

- Williams HC ,

- Royal College of Physicians

- Bailar JC ,

- Mosteller F

- Altman DG ,

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 18, Issue 2

- Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Helen Noble 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- 2 School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield , Huddersfield , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Helen Noble School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast, Medical Biology Centre, 97 Lisburn Rd, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; helen.noble{at}qub.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102054

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Evaluating the quality of research is essential if findings are to be utilised in practice and incorporated into care delivery. In a previous article we explored ‘bias’ across research designs and outlined strategies to minimise bias. 1 The aim of this article is to further outline rigour, or the integrity in which a study is conducted, and ensure the credibility of findings in relation to qualitative research. Concepts such as reliability, validity and generalisability typically associated with quantitative research and alternative terminology will be compared in relation to their application to qualitative research. In addition, some of the strategies adopted by qualitative researchers to enhance the credibility of their research are outlined.

Are the terms reliability and validity relevant to ensuring credibility in qualitative research?

Although the tests and measures used to establish the validity and reliability of quantitative research cannot be applied to qualitative research, there are ongoing debates about whether terms such as validity, reliability and generalisability are appropriate to evaluate qualitative research. 2–4 In the broadest context these terms are applicable, with validity referring to the integrity and application of the methods undertaken and the precision in which the findings accurately reflect the data, while reliability describes consistency within the employed analytical procedures. 4 However, if qualitative methods are inherently different from quantitative methods in terms of philosophical positions and purpose, then alterative frameworks for establishing rigour are appropriate. 3 Lincoln and Guba 5 offer alternative criteria for demonstrating rigour within qualitative research namely truth value, consistency and neutrality and applicability. Table 1 outlines the differences in terminology and criteria used to evaluate qualitative research.

- View inline

Terminology and criteria used to evaluate the credibility of research findings

What strategies can qualitative researchers adopt to ensure the credibility of the study findings?

Unlike quantitative researchers, who apply statistical methods for establishing validity and reliability of research findings, qualitative researchers aim to design and incorporate methodological strategies to ensure the ‘trustworthiness’ of the findings. Such strategies include:

Accounting for personal biases which may have influenced findings; 6

Acknowledging biases in sampling and ongoing critical reflection of methods to ensure sufficient depth and relevance of data collection and analysis; 3

Meticulous record keeping, demonstrating a clear decision trail and ensuring interpretations of data are consistent and transparent; 3 , 4

Establishing a comparison case/seeking out similarities and differences across accounts to ensure different perspectives are represented; 6 , 7

Including rich and thick verbatim descriptions of participants’ accounts to support findings; 7

Demonstrating clarity in terms of thought processes during data analysis and subsequent interpretations 3 ;

Engaging with other researchers to reduce research bias; 3

Respondent validation: includes inviting participants to comment on the interview transcript and whether the final themes and concepts created adequately reflect the phenomena being investigated; 4

Data triangulation, 3 , 4 whereby different methods and perspectives help produce a more comprehensive set of findings. 8 , 9

Table 2 provides some specific examples of how some of these strategies were utilised to ensure rigour in a study that explored the impact of being a family carer to patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis. 10

Strategies for enhancing the credibility of qualitative research

In summary, it is imperative that all qualitative researchers incorporate strategies to enhance the credibility of a study during research design and implementation. Although there is no universally accepted terminology and criteria used to evaluate qualitative research, we have briefly outlined some of the strategies that can enhance the credibility of study findings.

- Sandelowski M

- Lincoln YS ,

- Barrett M ,

- Mayan M , et al

- Greenhalgh T

- Lingard L ,

Twitter Follow Joanna Smith at @josmith175 and Helen Noble at @helnoble

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Editorial Notes

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2020

What is useful research? The good, the bad, and the stable

- David M. Ozonoff 1 &

- Philippe Grandjean 2 , 3

Environmental Health volume 19 , Article number: 2 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

2 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

A scientific journal like Environmental Health strives to publish research that is useful within the field covered by the journal’s scope, in this case, public health. Useful research is more likely to make a difference. However, in many, if not most cases, the usefulness of an article can be difficult to ascertain until after its publication. Although replication is often thought of as a requirement for research to be considered valid, this criterion is retrospective and has resulted in a tendency toward inertia in environmental health research. An alternative viewpoint is that useful work is “stable”, i.e., not likely to be soon contradicted. We present this alternative view, which still relies on science being consensual, although pointing out that it is not the same as replicability, while not in contradiction. We believe that viewing potential usefulness of research reports through the lens of stability is a valuable perspective.

Good science as a purpose

Any scientific journal wishes to add to the general store of knowledge. For Environmental Health, an additional important goal is also to publish research that is useful for public health. While maximizing scientific validity is an irreducible minimum for any research journal, it does not guarantee that the outcome of a “good” article is useful. Most writing on this subject concerns efficiencies and criteria for generating new and useful research results while avoiding “research waste” [ 1 ]. In this regard, the role of journals is hard to define. Indeed, a usefulness objective depends upon what happens after publication, thus to some extent being out of our control. That said, because of the importance of this issue the Editors have set out to clarify our thinking about what makes published research useful.

First the obvious: properly conducted scientific research may not be useful, or worse, may potentially mislead, confuse or be erroneously interpreted. Journal editors and reviewers can mitigate such regrettable outcomes by being attentive to faulty over- or under-interpretation of properly generated data, and vice versa, ensuring that unrealistic standards don’t prevent publication of a “good” manuscript. In regard to the latter, we believe our journal should not shy away from alternative or novel interpretations that may be counter to established paradigms and have consciously adopted a precautionary orientation [ 2 ]: We believe that it is reasonable to feature risks that may seem remote at the moment because the history of environmental and occupational health is replete with instances of red flags ignored, resulting in horrific later harms that could no longer be mitigated [ 3 , 4 ].

Nonetheless, it has happened that researchers publishing results at odds with vested interests have become targets of unreasonable criticism and intimidation whose aim is to suppress or throw suspicion on unwelcome research information, as in the case of lead [ 3 , 5 ] and many other environmental chemicals [ 6 ]. An alternative counter strategy is generating new results favorable to a preferred view [ 7 , 8 ], with the objective of casting doubt on the uncomfortable research results. Indeed, one trade association involved in supporting such science once described its activities with the slogan, “Doubt is our product” [ 9 ]. Thus, for better or for worse, many people do not separate science, whether good or bad, from its implications [ 10 ].

Further, even without nefarious reasons, it is not uncommon for newly published research to be contradicted by additional results from other scientists. Not surprisingly, the public has become all too aware of findings whose apparent import is later found to be negligible, wrong, or cast into serious doubt, legitimately or otherwise [ 11 ]. This has been damaging to the discipline and its reputation [ 12 ].

Replication as a criterion

A principal reaction to this dilemma has been to demand that results be “replicated” before being put to use. As a result, both funding agencies [ 13 ] and journals [ 14 ] have announced their intention of emphasizing the reproducibility of research, thereby also facilitating replication [ 15 ]. On its face this sounds reasonable, but usual experimental or observational protocols are already based on internal replication. If some form of replication of a study is desired, attempts to duplicate an experimental set-up can easily produce non-identical measurements on repeated samples, and seemingly similar people in a population may yield somewhat different observations. Given an expected variability within and between studies, we need to define more precisely what is to be replicated and how it is to be judged.

That said, in most instances, it seems that what we are really asking for is interpretive replication (i.e., do we think two or more studies mean the same thing), not observational or measurement replication. Uninterpreted evidence is just raw data. The main product of scientific journals like Environmental Health is interpreted evidence. It is interpreted evidence that is actionable and likely to affect practice and policy.

Research stability

This brings us back to the question of what kind of evidence and its accompanying interpretation is likely to be of use? The philosopher Alex Broadbent distinguishes between how results get used and the decision about which results are likely to be used [ 16 ]. Discussions of research translation tend to focus on the former question, while the latter is rarely discussed. Broadbent introduces a new concept into the conversation, the stability of the research results.

He begins by identifying which results are not likely to be used. Broadbent observes that if a practitioner or policy-maker thinks a result might soon be overturned she is unlikely to use it. Since continual revision is a hallmark of science, this presents a dilemma. All results are open to revision as science progresses, so what users and policy makers really want are stable results, ones whose meaning is unlikely to change in ways that make a potential practice or policy quickly obsolete or wrong. What are the features of a stable result?

This is a trickier problem than it first appears. As Broadbent observes it does not seem sufficient to say that a stable a result is one that is not contradicted by subsequent work, an idea closely related to replication. Failure to contradict, like lack of replication, may have many reasons, including lack of interest, lack of funding, active suppression of research in a subject, or external events like social conflict or recession. Moreover, there are many examples of clinical practice, broadly accepted as stable in the non-contradiction sense, that have not been tested for one reason or another. Contrariwise, contradictory results may also be specious or fraudulent, e.g., due to attempts to make an unwelcome result appear unstable and hence unusable [ 6 , 9 ]. In sum, lack of contradiction doesn’t automatically make a result stable, nor does its presence annul the result.

One might plausibly think that the apparent truth of a scientific result would be sufficient to make a result stable. This is also in accordance with Naomi Oreskes’ emphasis of scientific knowledge being fundamentally consensual [ 10 ] and relies on the findings being generalizable [ 15 ]. Our journal, like most, employs conventional techniques like pre-publication peer review and editorial judgment, to maximize scientific validity of published articles; and we require Conflict of Interest declarations to maximize scientific integrity [ 6 , 17 ]. Still, a result may be true but not useful, and science that isn’t true may be very useful. Broadbent’s example of the latter is the most spectacular. Newtonian physics continues to be a paragon of usefulness despite the fact that in the age of Relativity Theory we know it to be false. Examples are also prevalent in environmental health. When John Snow identified contaminated water as a source of epidemic cholera in the mid-nineteenth Century he believed a toxin was the cause, as the germ theory of disease had not yet found purchase. This lack of understanding did not stop practitioners from advocating limiting exposure to sewage-contaminated water. Nonetheless, demands for modes of action or adverse outcome pathways are often used to block the use of new evidence on environmental hazards [ 18 ].

Criteria for stability

Broadbent’s suggestion is that a result likely to be seen as stable by practitioners and policy makers is one that (a) is not contradicted by good scientific evidence; and (b) would not likely be soon contradicted by further good research [ 16 ] (p. 63).

The first requirement, (a), simply says that any research that produces contradictory evidence be methodologically sound and free from bias, i.e., “good scientific evidence.” What constitutes “good” scientific evidence is a well discussed topic, of course, and not a novel requirement [ 1 ], but the stability frame puts existing quality criteria, in a different, perhaps more organized, structure, situating the evidence and its interpretation in relation to stability as a criterion for usefulness.

More novel is requirement (b), the belief that if further research were done it would not likely result in a contradiction. The if clause focuses our attention on examining instances where the indicated research has not yet been done. The criterion is therefore prospective, where the replication demand can only be used in retrospect.

This criterion could usefully be applied to inconclusive or underpowered studies that are often incorrectly labeled “negative” and interpreted to indicate “no risk” [ 18 ]. A U.S. National Research Council committee called attention to the erroneous inference that chemicals are regarded inert or safe, unless proven otherwise [ 19 ]. This “untested-chemical assumption” has resulted in exposure limits for only a small proportion of environmental chemicals, limits often later found to be much too high to adequately protect against adverse health effects [ 20 , 21 ]. For example, some current limits for perfluorinated compounds in drinking water do not protect against the immunotoxic effects in children and may be up to 100-fold too high [ 22 ].

Inertia as a consequence

Journals play an unfortunate part in the dearth of critical information on emerging contaminants, as published articles primarily address chemicals that have already been well studied [ 23 ]. This means that environmental health research suffers from an impoverishing inertia, which may in part be due to desired replications that may be superfluous or worse. The bottom line is that longstanding acceptance in the face of longstanding failure to test a proposition should not be used as a criterion of stability or of usefulness, although this is routinely done.

If non-contradiction, replication or truth are not reliable hallmarks of a potentially useful research result, then what is? Broadbent makes the tentative proposal that a stable interpretation is one which has a satisfactory answer to the question, “Why this interpretation rather than another?” Said another way, are there more likely, almost or equally as likely, or other possible explanations (including methodological error in the work in question)? Sometimes the answer is patently obvious. Such an evaluation is superfluous in instances where the outcomes have such forceful explanations that this exercise would be a waste of time, for example a construction worker falling from the staging. We only need one instance and (hopefully no repetitions) to make the case.

Consensus and stability

Having made the argument for perspicuous interpretation, we must also issue a note of caution. It is quite common to err in the other direction by downplaying conclusions and implications. Researchers frequently choose to hedge their conclusions by repeated use of words such as ‘maybe’, ‘perhaps’, ‘in theory’ and similar terms [ 24 ]. Indeed, we might call the hedge the official flower of epidemiology. To a policy maker, journalist or member of the public not familiar with the traditions of scientific writing, the caveats and reservations may sound like the new results are irredeemably tentative, leaving us with no justification for any intervention. To those with a vested interest, the soft wording can be exploited through selective quotation and by emphasizing real or alleged weaknesses [ 25 ]. This tendency goes beyond one’s own writings and affects peer review and evaluations of manuscripts and applications. Although skepticism is in the nature of science, a malignant form is the one that is veiled and expressed in terms of need for further replication or emphasizing limitations of otherwise stable observations [ 9 ]. By softening the conclusions and avoiding attribution of specific causality and the possible policy implications, researchers protect themselves against critique by appearing well-balanced, unassuming, or even skeptical toward one’s own findings. In seeking consensus, researchers often moderate or underestimate their findings, a tendency that is not in accordance with public health interests.

These are difficult issues, requiring a balancing act. The Editors continue to ponder the question how to inspire, improve and support the best research and its translation. We believe Broadbent’s stability idea is worth considering as an alternative perspective to the replication and research translation paradigms prevalent in discussions of this topic. We also believe in Oreskes’ vision of consensus, though not to a degree that will preclude new interpretations. Meanwhile, we will endeavor to keep the Journal’s standards high while encouraging work that will make a difference.

Availability of data and materials

Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):86–9.

Article Google Scholar

Grandjean P. Science for precautionary decision-making. In: Gee D, Grandjean P, Hansen SF, van den Hove S, MacGarvin M, Martin J, Nielsen G, Quist D, Stanners D, editors. Late Lessons from Early Warnings, vol. II. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency; 2013. p. 517–35.

Google Scholar

Markowitz GE, Rosner D. Deceit and denial : the deadly politics of industrial pollution. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2002.

European Environment Agency. Late lessons from early warnings: the precautionary principle 1896-2000. Environmental issue report No 22. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency; 2001.

Needleman HL. The removal of lead from gasoline: historical and personal reflections. Environ Res. 2000;84(1):20–35.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Krimsky S. Science in the private interest. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2003.

Boden LI, Ozonoff D. Litigation-generated science: why should we care? Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(1):117–22.

Fabbri A, Lai A, Grundy Q, Bero LA. The influence of industry sponsorship on the research agenda: a scoping review. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):e9–e16.

Michaels D. Doubt is their product: how industry's assault on science threatens your health. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Oreskes N. Why trust science? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2019.

Book Google Scholar

Nichols TM. The death of expertise : the campaign against established knowledge and why it matters. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Ioannidis JPA. All science should inform policy and regulation. PLoS Med. 2018;15(5):e1002576.

Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505(7485):612–3.

Journals unite for reproducibility. Nature. 2014;515(7525):7.

National Research Council. Reproducibility and replicability in science. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019.

Broadbent A. Is stability a stable category in medical epistemology? Angewandte Philosophie. 2015;2(1):24–37.

Soskolne CL, Advani S, Sass J, Bero LA, Ruff K. Response to Acquavella J, conflict of interest: a hazard for epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;36:62–3.

Grandjean P. Seven deadly sins of environmental epidemiology and the virtues of precaution. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):158–62.

National Research Council. Science and decisions: advancing risk assessment. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2009.

Goldsmith JR. Perspectives on what we formerly called threshold limit values. Am J Ind Med. 1991;19(6):805–12.

Schenk L, Hansson SO, Ruden C, Gilek M. Occupational exposure limits: a comparative study. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;50(2):261–70.

Grandjean P, Budtz-Jorgensen E. Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated alkylates: calculation of benchmark doses based on serum concentrations in children. Environ Health. 2013;12:35.

Grandjean P, Eriksen ML, Ellegaard O, Wallin JA. The Matthew effect in environmental science publication: a bibliometric analysis of chemical substances in journal articles. Environ Health. 2011;10:96.

Hyland K. Hedging in scientific research articles. John Benjamins: Amsterdam; 1998.

Grandjean P. Late insights into early origins of disease. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(2):94–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental Health, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

David M. Ozonoff

Department of Environmental Medicine, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Philippe Grandjean

Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DMO and PG jointly drafted the Editorial and read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Philippe Grandjean .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

DMO and PG are editors-in-chief of this journal but have no other interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ozonoff, D.M., Grandjean, P. What is useful research? The good, the bad, and the stable. Environ Health 19 , 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0556-5

Download citation

Published : 07 January 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0556-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Generalizability

- Replication

- Reproducibility

- Scientific journals

Environmental Health

ISSN: 1476-069X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 03 August 2020

Why time poverty matters for individuals, organisations and nations

- Laura M. Giurge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7974-391X 1 na1 ,

- Ashley V. Whillans ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1726-6978 2 na1 &

- Colin West 3

Nature Human Behaviour volume 4 , pages 993–1003 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

6511 Accesses

75 Citations

916 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social policy

Over the last two decades, global wealth has risen. Yet material affluence has not translated into time affluence. Most people report feeling persistently ‘time poor’—like they have too many things to do and not enough time to do them. Time poverty is linked to lower well-being, physical health and productivity. Individuals, organisations and policymakers often overlook the pernicious effects of time poverty. Billions of dollars are spent each year to alleviate material poverty, while time poverty is often ignored or exacerbated. In this Perspective, we discuss the societal, organisational, institutional and psychological factors that explain why time poverty is often under appreciated. We argue that scientists, policymakers and organisational leaders should devote more attention and resources toward understanding and reducing time poverty to promote psychological and economic well-being.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout