Understanding Reconstruction - A Historiography

As the United States entered the 20th century, Reconstruction slowly receded into popular memory. Historians began to debate its results. William Dunning and John W. Burgess led the first group to offer a coherent and structured argument. Along with their students at Columbia University, Dunning, Burgess, and their retinue created a historical school of thought known as the Dunning School. This interpretation of Reconstruction placed it firmly in the category of historical blunder.

Why did the Dunning School blame Radical Republicans and Freedmen for Reconstruction's failure?

While the Radical Republicans were the apparent villains, Dunning and his followers ascribed blame to President Johnson as well, saddling him with responsibility for Reconstruction’s failure. Freedmen were portrayed as animalistic or easily manipulated, therefore, lacking the kind of agency they indeed exhibited. While certainly influenced by the day's racial bias, the Dunning School at least formulated a coherent argument (although an incredibly inaccurate and distasteful one) that refused to fragment. This model of unity did prove somewhat valuable to historians following Dunning, even if their historical research opposed the Dunning School’s argument, “For all their faults, it is ironic that the best Dunning studies did, at least, attempt to synthesize the social, political, and economic aspects of the period.” In contrast, the Progressive historians that followed the Dunning School disagreed with some of its interpretations. President Johnson was not to blame, but rather, the Northern Radical Republicans were at fault. They cynically used freedmen's civil rights as a means to force capitalism and economic dependence on the South.

Why was W.E.B. Du Bois's reassessment of Reconstruction so important?

However, one work stands out from this period as a harbinger of what was to come. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote Black Reconstruction in America in 1935. Du Bois chastised historians for ignoring the central figures of Reconstruction, the freedmen. Moreover, Du Bois pointedly remarked on the prevailing racial bias of the historical inquiry up to that moment, “One fact and one alone explains the attitude of most recent writers toward Reconstruction; they cannot conceive of Negroes as men.” Du Bois’s indictment served as a precursor for the explosion of revisionist history of the 1960s, which would latch onto the argument of Du Bois and refocus the debate concerning Reconstruction to include the central figures of the freedmen.

The revisionists of the 1960s viewed Reconstruction's heroes to be the Southern freedmen and the Radical Republicans. Instead of going too far, Reconstruction failed to be radical enough. According to revisionists, Reconstruction was tragic not because it went too far and handcuffed white southerners; it was tragic because it was unable to securely secure the rights of freedmen and failed to restructure Southern society through land reform and similar measures. Following on the heels of the Revisionist School were the Post-Revisionists who viewed Reconstruction as overly conservative. This conservatism failed to achieve any lasting influence; thus, once Reconstruction ended, the South returned to its old social and economic structures.

What is the Modern Interpretation of Reconstruction?

So, where has that left historians today? How do more recent historians interpret Reconstruction? Several leading historians (James McPherson, Eric Foner, Emory Thomas) have labeled either the Civil War or Reconstruction as a second American revolution. Eric Foner’s work Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution openly claims Reconstruction to be a break from traditional systems (social, political, economic) prevailing in the South.

In contrast, Emory Thomas’s The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience argues the South first underwent a “conservative revolution” in breaking away from the Union since it broke from the North not to redefine itself but to maintain the status quo of the South. Ironically, according to Thomas, this first “external” revolution was subsumed by a more radical “internal” revolution during the Civil War as the South attempted to urbanize, industrialize and modernize to compete with the North. Thus, whether consciously or not, the Confederacy's leaders looked to recreate the South in a way that mirrored the North in several ways. However, this brief example illustrates the differences among historians and the current scholarship on the Civil War and Reconstruction. Perhaps, the best place to start might be with conditions between the North and South before the outbreak of war in 1861.

James McPherson provides a convincing account of the growing differences between the North and South on the eve of the war. McPherson, author of Battle Cry for Freedom (considered in some circles as the preeminent account of the Civil War), is frequently acknowledged as a leading if not the leading historian in Civil War studies today. In an essay for Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction entitled, “The Differences between the Antebellum North and South,” McPherson argues that the South had not changed, but the North had. According to McPherson, the Southern states had remained loyal to the Jeffersonian interpretation of republicanism. Instead of investing in manufacturing and industry, they reinvested in agrarian pursuits. Southern culture emphasized traditional values, patronage, and ties of kinship.

Northern republicanism was opposed to the Southern belief in republicanism emphasizing limited government and property rights, not to mention Southern anti-manufacturing sensibilities. Additionally, the more capital intensive economy of the North relied on wage labor and immigration. Two economic and social variables absent from the South. The rise of wage labor placed wager earners in the North in opposition to the system of slavery in the South, and the rising population of the North (from immigration) increased tensions between the two regions. Along with these differences, the West of America was growing rapidly in the image of the North. Resulting from the influence and growth of railroads, trade relations were no longer centered on the North/South relationship but East to West.

Moreover, the political system held a foundation based on the patronage of the planter class. According to Thomas, the South’s initial break from the Union was inspired by the hope that the South might preserve its traditions and institutions. Led by radical “fire-eaters,” Southern politicians incited animosity between the North and South, “They made a ‘conservative revolution’ to preserve the antebellum status quo, but they made a revolution just the same. The ‘fire-eaters’ employed classic revolutionary tactics in their agitation for secession. And the Confederates were no fewer rebels than their grandfathers had been in 1776”.

However, this initial ‘conservative revolution’ inspired by radicals was overtaken by the moderates of the political south who recognized the need for change. If the Confederacy were to survive economically, politically, and socially, they would mount their internal revolution. Peter Kolchin’s work American Slavery 1619-1877 upholds much of McPherson’s and Thomas’ arguments concerning the South’s increasingly entrenched society. Kolchin’s work attempts to synthesize the prevailing studies of the day concerning slavery in America. Divided into three sections (colonial America and the American Revolution, antebellum South, and Civil War and Reconstruction)

Moreover, politically, Kolchin remarks on the non-democratic nature of the South, “antebellum Southern sociopolitical thought harbored profoundly anti-democratic currents … More common than outright attacks on democracy were denunciations of fanatical reformism and appealed to conservatism, order, and tradition.” Also, the access to education among Southerners was limited at best, “Advocates of public education, for example, made little headway in their drive to persuade Southern state legislatures to emulate their northern counterparts and establish statewide public schooling … it was only after the Civil War that public education became widely available in the South.”

How did the Civil War Change the South's Social Structure?

In general, Thomas points out three areas of change political, economic, and social. The economic reform was extreme. As the Civil War commenced, the south had neither a large industrial complex nor many large urban areas (New Orleans stands as the lone exception). Jefferson Davis and others saw the need for increased industry and urbanization, “A nation of farmers knew the frustration of going hungry, but Southern industry made great strides. And Southern cities swelled in size and importance. Cotton, once king, became a pawn in the Confederate South. The emphasis on manufacturing and urbanization came too little, too late. But compared to the antebellum South, the Confederate South underwent nothing short of an economic revolution.”

Thus, once Weaver had assembled some 70 slaves, he no longer looked to improve industrial efficiency or examine technological advancements. “After he acquired and trained a group of skilled slave artisans in the 1820s and 1830s and had his ironworks functioning successfully, Weaver displayed little interest in trying to improve the technology of ironmaking at Buffalo Forge … The emphasis was on stability, not innovation. Slavery, in short, seems to have exerted a profoundly conservative influence on the manufacturing process at Buffalo Forge, and one suspects that similar circumstances prevailed at industrial establishments throughout the slave South.” Thus, Dew’s assertion would render the Confederacy’s attempt to industrialize increasingly tricky since the Southern labor system was not conducive to optimum industrial efficiency. Additionally, the Confederacy’s attempt to industrialize, urbanize, and in general, command the Southern economy contrasts sharply with its belief in states’ rights federal authority. Through such management of the economy, the Confederate leaders were contradicting themselves, yet the war called for such measures.

According to Thomas, such reorganization did not limit itself to the economic field. Southern women were no longer confined to the home, “Southern women climbed down from their pedestals and became refugees, went to work in factories, or assumed the responsibility for managing farms.” This hardly seems to be a radical premise since this cycle repeats itself nationally during both World Wars of the 20th century.

Besides, class consciousness began to form in the minds of the “proletariat” “Under the strain of wartime some “un Southern” rents appeared in the fabric of Southern society. The very process of renting what had been harmonious—mass meetings, riots, resistance to Confederate law and order—was the most visible manifestation of the social unsettlement within the Confederate South. Whether caused by heightened class awareness, disaffection with the “cause,” or frustration with physical privation, domestic tumults bore witness to the social ferment which replaced antebellum stability.” Of course, Thomas is careful to couch this class consciousness with limits, “This is not to imply that the Confederate south seethed with labor unrest; it is rather to say that working men in the Confederacy asserted themselves to a degree unknown in the antebellum period.”

Therefore, would this not serve more aptly as an example of wartime necessities undertaken for war but not intended for permanence? One might respond that such cases begin the process of change since historically, once people are granted rights or freedoms, it proves to be quite difficult to reclaim such rights, mobility, or freedoms. However, one last point concerning social mobility must be made. Considering the conditions of trade for the South during the war, new ways of the trade needed to be located. Such avenues to wealth did provide many southerners previously excluded from the planter class to ascend the ladder of social mobility once new avenues or means to profit were established, “Those who were able to take advantage of new opportunities in trade and industry became wealthy and powerful men … Not only did exemplary men rise from commonplace to prominence in the Confederate period; statistical evidence tends to confirm that the Confederate leadership as a whole came from non-planters.”

Similarly, Thomas argues that the suspension of civil liberties in the South was a radical departure from Southern culture. Suspension of civil liberties is a common wartime tactic (WWI, WWII). Lincoln did the same in the North. Thomas cannot use this as truly viable evidence of revolutionary change.

Was Reconstruction a Revolution?

However, further complicating this portion of Foner’s argument is the non-linear nature of race relations in the South. Rather as Foner illustrates throughout the book, race relations were subject to local variables that greatly influenced interactions. Moreover, advances did not proceed linearly. Instead, through complex social, political, and economic interactions between races, race relations gradually evolved at times progressing, while in other moments, regressing. African American freedmen fought for their freedoms and liberties even when white resistance turned violent and exclusionary. Its this constant push and pull effect that produces the racial structure of the postwar South.

Foner’s work's major strength lies in its attempt to sketch for the reader a process that Foner argues begins in 1863 with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. In reality, Lincoln’s command held minimal legitimacy since it did not free slaves in the border states. Thus, Lincoln’s lack of authority over the South left his abolition of slavery a mere symbol in the Southern states. Despite this fact, Foner argues that “emancipation meant more than the end of a labor system, more even than the uncompensated liquidation of the nation’s largest concentration of private property … The demise of slavery inevitably threw open the most basic questions of the polity, economy, and society. Begun to preserve the Union, the war now portended a far-reaching transformation in Southern life and a redefinition of the place of blacks in American society and of the very meaning of freedom in the American republic.”

Reconstruction argues similarly, “But in 1867, politics emerged as the principal focus of black aspirations. The meteoric rise of the Union League reflected and channeled this political mobilization. By the end of 1867, it seemed, virtually every black voter in the South had enrolled in the Union League. The league’s main function, however, was political education” However, this political awareness did not mean that all Southerners appreciated it, nor did it necessarily lead to a better understanding between white and black Southerners, “Now as freedmen poured into the league, ‘the negro question’ disrupted some upcountry branches, leading many white members to withdraw altogether or retreat into segregated branches.” Such political activism redrew racial relationships and reorganized institutions. For example, the Union League’s acceptance of freedmen resulted in white flight or segregation among other branches, despite the small white farmer and the freedmen's obvious class similarities. Still, the political activism by freedmen and freedwomen signifies a great change in Southern society.

Harold D. Woodman also notes similar manifestations. However, it must be noted; Woodman refuses to use the term “revolutionary” for the Civil War and Reconstruction period. According to Woodman, historians must assess the quality of this change, not the amount. Woodman notes the need for reform in the former slave society. However, the reform needed was never produced. Bourgeoisie free labor was the basis of the new southern economy since the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil War had destroyed the previous one. New roles for both slave and the planter arose, along with the need for new lines of authority.

Why was Reconstruction was a Failure?

So, how successful was Reconstruction? Foner argues that Reconstruction proved revolutionary for a period but ultimately failed. “Here, however, we enter the realm of the purely speculative. What remains certain is that Reconstruction failed and that for blacks, its failure was a disaster whose magnitude cannot be obscured by the genuine accomplishments that did endure. For the nation as a whole, the collapse of Reconstruction was a tragedy that deeply affected the course of its future development.” Thomas views the final results of Reconstruction similarly but through a slightly different historical lens. According to Thomas, Reconstruction undid the revolutionary advances of the Confederacy, “Ironically, the internal revolution went to completion at the very time that the external revolution collapsed … The program of the radical Republicans may have failed to restructure Southern society. It may, in the end, have “sold out” the freedmen in the South. Reconstruction did succeed in frustrating the positive elements of the revolutionary Southern experience.”

Thus, Reconstruction allowed African Americans to more fully express agency while still oppressed. It gave blacks the chance to counter such oppression more freely. Networks, communities, and relationships were all redefined and recreated. Again, just as Foner maintained, Kolchin remarks, “And in the years after World War II, again with the help of white allies, they spearheaded a “second Reconstruction” – grounded on the legal foundation provided by the first — to create an interracial society that would finally overcome the persistent legacy of slavery.”

This article was originally published on Videri.org and is republished here with their permission.

Updated December 8, 2020

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Origins of Reconstruction

Presidential reconstruction, radical reconstruction.

- The end of Reconstruction

What was the Reconstruction era?

What were the reconstruction era promises, was the reconstruction era a success or a failure.

- Who was W.E.B. Du Bois?

- What did W.E.B. Du Bois write?

Reconstruction

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- American Battlefield Trust - Reconstruction: An Overview

- Texas State Historical Association - The Handbook of Texas Online - Reconstruction

- PBS LearningMedia - Michael Williams: Reconstruction

- Digital History - America's Reconstruction

- USHistory.org - Reconstruction

- Florida State College at Jacksonville Pressbooks - African American History and Culture - Politics of Reconstruction

- New Jersey State Library - The Reconstruction Era, 1865-1877

- National Park Service - Reconstruction

- Reconstruction - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Reconstruction - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The Reconstruction era was the period after the American Civil War from 1865 to 1877, during which the United States grappled with the challenges of reintegrating into the Union the states that had seceded and determining the legal status of African Americans . Presidential Reconstruction, from 1865 to 1867, required little of the former Confederate states and leaders. Radical Reconstruction attempted to give African Americans full equality.

Why was the Reconstruction era important?

The Reconstruction era redefined U.S. citizenship and expanded the franchise, changed the relationship between the federal government and the governments of the states, and highlighted the differences between political and economic democracy.

While U.S. Pres. Andrew Johnson attempted to return the Southern states to essentially the condition they were in before the American Civil War , Republicans in Congress passed laws and amendments that affirmed the “equality of all men before the law” and prohibited racial discrimination, that made African Americans full U.S. citizens, and that forbade laws to prevent African Americans from voting.

During a brief period in the Reconstruction era, African Americans voted in large numbers and held public office at almost every level, including in both houses of Congress . However, this provoked a violent backlash from whites who did not want to relinquish supremacy. The backlash succeeded, and the promises of Reconstruction were mostly unfulfilled. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were unenforced but remained on the books, forming the basis of the mid-20th-century civil rights movement .

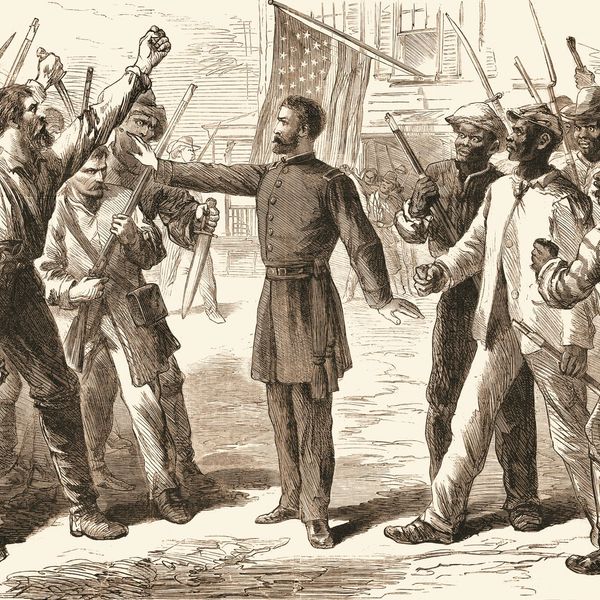

Reconstruction , in U.S. history, the period (1865–77) that followed the American Civil War and during which attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery and its political, social, and economic legacy and to solve the problems arising from the readmission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded at or before the outbreak of war. Long portrayed by many historians as a time when vindictive Radical Republicans fastened Black supremacy upon the defeated Confederacy , Reconstruction has since the late 20th century been viewed more sympathetically as a laudable experiment in interracial democracy . Reconstruction witnessed far-reaching changes in America’s political life. At the national level, new laws and constitutional amendments permanently altered the federal system and the definition of American citizenship. In the South , a politically mobilized Black community joined with white allies to bring the Republican Party to power, and with it a redefinition of the responsibilities of government.

The national debate over Reconstruction began during the Civil War. In December 1863, less than a year after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation , Pres. Abraham Lincoln announced the first comprehensive program for Reconstruction, the Ten Percent Plan. Under it, when one-tenth of a state’s prewar voters took an oath of loyalty, they could establish a new state government. To Lincoln, the plan was an attempt to weaken the Confederacy rather than a blueprint for the postwar South. It was put into operation in parts of the Union-occupied Confederacy, but none of the new governments achieved broad local support. In 1864 Congress enacted (and Lincoln pocket vetoed) the Wade-Davis Bill , which proposed to delay the formation of new Southern governments until a majority of voters had taken a loyalty oath. Some Republicans were already convinced that equal rights for the former slaves had to accompany the South’s readmission to the Union. In his last speech, on April 11, 1865, Lincoln, referring to Reconstruction in Louisiana , expressed the view that some Blacks—the “very intelligent” and those who had served in the Union army—ought to enjoy the right to vote .

Following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Andrew Johnson became president and inaugurated the period of Presidential Reconstruction (1865–67). Johnson offered a pardon to all Southern whites except Confederate leaders and wealthy planters (although most of these subsequently received individual pardons), restoring their political rights and all property except slaves. He also outlined how new state governments would be created. Apart from the requirement that they abolish slavery, repudiate secession, and abrogate the Confederate debt, these governments were granted a free hand in managing their affairs. They responded by enacting the Black codes , laws that required African Americans to sign yearly labour contracts and in other ways sought to limit the freedmen’s economic options and reestablish plantation discipline . African Americans strongly resisted the implementation of these measures, and they seriously undermined Northern support for Johnson’s policies.

When Congress assembled in December 1865, Radical Republicans such as Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Sen. Charles Sumner from Massachusetts called for the establishment of new Southern governments based on equality before the law and universal male suffrage. But the more numerous moderate Republicans hoped to work with Johnson while modifying his program. Congress refused to seat the representatives and senators elected from the Southern states and in early 1866 passed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights Bills. The first extended the life of an agency Congress had created in 1865 to oversee the transition from slavery to freedom. The second defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens, who were to enjoy equality before the law.

A combination of personal stubbornness, fervent belief in states’ rights , and racist convictions led Johnson to reject these bills, causing a permanent rupture between himself and Congress. The Civil Rights Act became the first significant legislation in American history to become law over a president’s veto. Shortly thereafter, Congress approved the Fourteenth Amendment , which put the principle of birthright citizenship into the Constitution and forbade states to deprive any citizen of the “equal protection” of the laws. Arguably the most important addition to the Constitution other than the Bill of Rights , the amendment constituted a profound change in federal-state relations. Traditionally, citizens’ rights had been delineated and protected by the states. Thereafter, the federal government would guarantee all Americans’ equality before the law against state violation.

In the fall 1866 congressional elections, Northern voters overwhelmingly repudiated Johnson’s policies. Congress decided to begin Reconstruction anew. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 divided the South into five military districts and outlined how new governments, based on manhood suffrage without regard to race , were to be established. Thus began the period of Radical or Congressional Reconstruction, which lasted until the end of the last Southern Republican governments in 1877.

By 1870 all the former Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and nearly all were controlled by the Republican Party. Three groups made up Southern Republicanism. Carpetbaggers , or recent arrivals from the North, were former Union soldiers, teachers, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, and businessmen. The second large group, scalawags , or native-born white Republicans, included some businessmen and planters, but most were nonslaveholding small farmers from the Southern up-country. Loyal to the Union during the Civil War, they saw the Republican Party as a means of keeping Confederates from regaining power in the South.

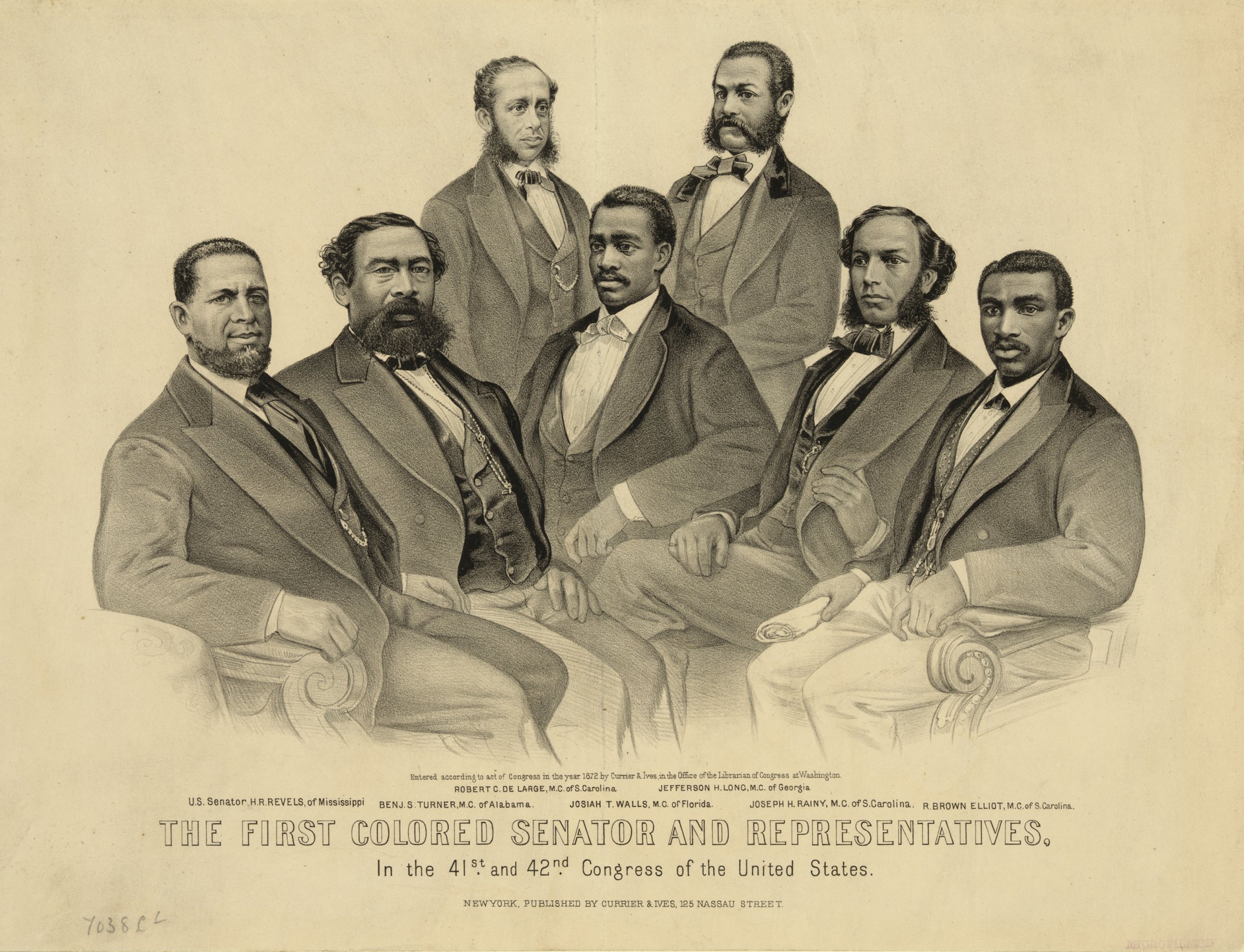

In every state, African Americans formed the overwhelming majority of Southern Republican voters. From the beginning of Reconstruction, Black conventions and newspapers throughout the South had called for the extension of full civil and political rights to African Americans. Composed of those who had been free before the Civil War plus slave ministers, artisans , and Civil War veterans, the Black political leadership pressed for the elimination of the racial caste system and the economic uplifting of the former slaves. Sixteen African Americans served in Congress during Reconstruction—including Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce in the U.S. Senate—more than 600 in state legislatures, and hundreds more in local offices from sheriff to justice of the peace scattered across the South. So-called “Black supremacy” never existed, but the advent of African Americans in positions of political power marked a dramatic break with the country’s traditions and aroused bitter hostility from Reconstruction’s opponents.

Serving an expanded citizenry, Reconstruction governments established the South’s first state-funded public school systems, sought to strengthen the bargaining power of plantation labourers, made taxation more equitable, and outlawed racial discrimination in public transportation and accommodations. They also offered lavish aid to railroads and other enterprises in the hope of creating a “New South” whose economic expansion would benefit Blacks and whites alike. But the economic program spawned corruption and rising taxes, alienating increasing numbers of white voters.

Meanwhile, the social and economic transformation of the South proceeded apace. To Blacks, freedom meant independence from white control. Reconstruction provided the opportunity for African Americans to solidify their family ties and to create independent religious institutions, which became centres of community life that survived long after Reconstruction ended. The former slaves also demanded economic independence. Blacks’ hopes that the federal government would provide them with land had been raised by Gen. William T. Sherman ’s Field Order No. 15 of January 1865, which set aside a large swath of land along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia for the exclusive settlement of Black families, and by the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of March, which authorized the bureau to rent or sell land in its possession to former slaves. But President Johnson in the summer of 1865 ordered land in federal hands to be returned to its former owners. The dream of “ 40 acres and a mule” was stillborn. Lacking land, most former slaves had little economic alternative other than resuming work on plantations owned by whites. Some worked for wages, others as sharecroppers, who divided the crop with the owner at the end of the year. Neither status offered much hope for economic mobility. For decades, most Southern Blacks remained propertyless and poor.

Nonetheless, the political revolution of Reconstruction spawned increasingly violent opposition from white Southerners. White supremacist organizations that committed terrorist acts, such as the Ku Klux Klan , targeted local Republican leaders for beatings or assassination. African Americans who asserted their rights in dealings with white employers, teachers, ministers, and others seeking to assist the former slaves also became targets. At Colfax, Louisiana, in 1873, scores of Black militiamen were killed after surrendering to armed whites intent on seizing control of local government. Increasingly, the new Southern governments looked to Washington, D.C. , for assistance.

By 1869 the Republican Party was firmly in control of all three branches of the federal government. After attempting to remove Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton , in violation of the new Tenure of Office Act , Johnson had been impeached by the House of Representatives in 1868. Although the Senate, by a single vote, failed to remove him from office, Johnson’s power to obstruct the course of Reconstruction was gone. Republican Ulysses S. Grant was elected president that fall ( see United States presidential election of 1868 ). Soon afterward, Congress approved the Fifteenth Amendment , prohibiting states from restricting the right to vote because of race. Then it enacted a series of Enforcement Acts authorizing national action to suppress political violence. In 1871 the administration launched a legal and military offensive that destroyed the Klan. Grant was reelected in 1872 in the most peaceful election of the period.

| | | | |||||

|

| |||||

In short, the South was effectively brought into a national system of credit and labor as a result of Reconstruction. “Free” labor, rather than some system of coerced labor would prevail in the region. Neither serfdom nor peasantry would replace slavery. And southern landowners and freedmen, whether they wanted to or not, were incorporated into the national credit markets.

Let us now take stock of the answers to the questions that we began with. On what terms would the nation be reunited? In short, on national terms. Property was not expropriated or redistributed in the South. Reforms that were imposed on the South—the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, for example—applied to the entire nation.

What implications did the Civil War have for citizenship? The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments represented stunning expansions of the rights of citizenship to former slaves. Even during the depths of the Jim Crow era in the early twentieth century, white supremacists never succeeded in returning citizenship to its pre-Civil War boundaries. African Americans especially insisted that they may have been deprived of their rights after the Civil War but they had neither surrendered nor lost their claim to those rights.

What would be the future of the restored nation’s economy? In simplest terms, Abraham Lincoln’s famous observation that a house divided cannot stand was translated into policy. However impoverished and credit starved, the former Confederacy was integrated back into the national economy , laying the foundation for the future emergence of the most dynamic industrial economy in the world. African Americans would not be enslaved or assigned to a separate economic status. But nor would African Americans as a group be provided with any resources with which to compete.

Guiding Student Discussion

Possible student perceptions of Reconstruction Aside from the challenge of organizing the complex events of the Reconstruction era into a narrative accessible to students, the biggest challenge is to help students understand what was possible and what was not possible after the Civil War. Students, for example, may be inclined to believe that white Americans were never committed to racial equality in the first place so Reconstruction was doomed to failure. Some students may fixate on northern white hypocrisy; many white Republicans pressured southern voters to pass the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments even while they opposed its passage in the North. Yet others may emphasize that citizenship rights for blacks were hollow because blacks had no economic resources; blacks in postwar America could not easily escape an economic system that was slavery by another name. Each of these positions is worth discussion, but each tends to flatten out the motivations and behavior of the actors in the drama of Reconstruction. And virtually all of these interpretations presumed that the outcome of Reconstruction was both inevitable and wholly outside the hands of African Americans.

Ask students to design their own version of Reconstruction. One approach that I have adopted in hopes of countering these tendencies is to ask students to state their “first principles” that they think Reconstruction should have pursued and established. If your students are like mine, many will propose that Reconstruction should have guaranteed equal rights for all Americans. I then ask them to define what those rights should have been. At this point, even students who are in broad agreement about the principle of equal rights for all Americans may differ on the specific content of those rights. For example, some may stress economic equality whereas others may emphasize equality of opportunity. In any case, the next step is to ask the students to think about how they would have turned their principle into policy. Those students who may have stressed economic equality may then sketch out a plan for “forty acres and mule” for each former slave. Those who stress the need for equal opportunity may sketch out the need for public education for freed people and other southerners. I next ask students where the requisite resources for these policies would come from. For example, where would the federal government have gotten the land and money to provide former slaves with land and livestock? If the federal government had expropriated land and resources from former slave masters, what consequences would that policy have had for private property elsewhere in the United States? (If the government could take lake and property from former slave masters, would it then have had precedent to later take land and property from former slaves?) What would the consequences of this policy have been for the production of cotton, the nation’s most important export? In response to students who propose universal public education, I ask them about the funding for these new schools. Who would pay for them? If taxes needed to be raised, what and whom should have been taxed? Should the schools have been integrated? If so, how would the resistance of white southerners to integrated schools be overcome? If not, would separate schools for blacks and white have legitimized segregation ?

Through this exercise, students gain a better sense of how all of the facets of Reconstruction were interrelated and how any broad principle was shaped by the circumstances, constraints, and traditions of the age. Equally important, students will better appreciate how astute African Americans were in pursuing their goals during the Reconstruction era. They recognized that the Civil War had ended slavery and destroyed the antebellum South, but it had not created a clean slate on which they had a free hand to write their future. Instead, black Americans were constantly gauging what was possible and who they might ally with to translate their long-suppressed hopes into a secure and rewarding future in American society.

The role of African Americans in Reconstruction The search by African Americans for allies during Reconstruction is the focus of another worthwhile exercise. It is essential for students to understand that African Americans were active participants in Reconstruction. They were not the dupes of northern politicians. Nor were they cowed by southern whites. This said, African Americans never had decisive control over Reconstruction. Whatever their goals, they needed allies. With that fundamental reality in mind, Ask students to identify the major stakeholders in Reconstruction. I ask students to draw up a list of the groups in American society who had a major stake/role in Reconstruction. Typically, students will identify the major actors as white northerners, white southerners and blacks. I then press the students to break those groups down further. Were all white northerners alike in their attitudes toward blacks? Were all white southerners? And were there any sub-groups of African Americans that should be distinguished? After this revision, my students typically distinguish between pro- and anti-black white northerners, elite white southerners, middling white southerners, blacks who were free before the Civil War, and recently freed slaves .

Once we have identified the actors in Reconstruction, we then systematically work thorough this list and consider what interests each of these groups might have shared. Put another way, on what grounds could each (any) of these groups found common cause with African Americans? Take middling whites for example. Many students may wonder why poor white southerners did not forge an alliance with former slaves. After all, they had poverty in common. Some students might suggest that poor whites refused to acknowledge their common condition with African Americans because of racism; a poor white man, in short, may have been poor but he could insist that at least he was a member of the “superior” white race. I also point out that poor whites and poor blacks may both have been poor, but they were poor in very different ways so that they were at best tentative allies. Poor whites typically were land poor; that is, they owned land but usually not the other resources that would have allowed them to exploit their land intensively. Black southerners were poor and landless; most had no significant holding of land to exploit. Consequently, when blacks called for expanded social services such as schools to meet their needs, they were implicitly calling for additional taxes to fund the services. What would be taxed to fund these new schools and services? In the nineteenth century, tangible property, and specifically land, was the principal taxed property. Taxes on the land of poor whites, then, helped to underwrite new schools in the Reconstruction South. These taxes, in the end, drove a wedge between poor whites and African Americans and ensured that black southerners could not take for granted the support of poor white southerners who bridled at paying taxes on their land to fund new schools. Or take the example of white northerners. Even some white Republicans who were unsettled by calls for racial equality could be allies of former slaves. Republicans believed that without the support of black voters in the South their party might surrender national power to the Democratic Party. Expediency alone, then, coaxed some white Republicans to support political rights for blacks. But as soon as the Republican Party garnered a sufficient national majority so that the support of southern blacks was no longer essential, these same northern Republicans urged the party to jettison its pledge to defend African American rights.

This exercise helps students see African Americans as actors in Reconstruction, but actors constrained by the actions of other actors. This exercise turns Reconstruction into a dynamic process of contestation, negotiation, and compromise, which, of course, is precisely what Reconstruction was.

What resources did the formerly enslaved bring to freedom? Finally, another possible approach is to focus students’ attention on the resources that African Americans could tap as they made the transition from slavery to freedom. I ask students to consider the needs that African Americans, as free Americans, had in 1865 and the resources they had at their disposal to allow them to survive as free Americans. This exercise prompts students to consider the resources and institutions that blacks already possessed in 1865 as well as those that blacks would subsequently need to build. In other words, many slaves possessed skills (some could read, some were skilled artisans) and had built institutions (particularly religious institutions ) that were foundations for black communities after emancipation. Taking these into account, students can then consider what additional resources former slaves needed and how they might have acquired these resources. This approach to Reconstruction inevitably leads to discussion of the possibilities and limits of black self-help as well as the prospects for meaningful assistance to blacks from white Americans. It also often leads to valuable discussions of the merits and drawbacks of the racially exclusive institutions that emerged during Reconstruction, such as schools and churches. Students gain a better appreciation, for example, of why blacks preferred schools taught by black teachers and black denominations even while students also recognize the subsequent vulnerability of these institutions.

Historians Debate

No era of American history has produced hotter scholarly debates than Reconstruction. Historians may have written more about the Civil War but they have argued louder and longer about Reconstruction. With a few notable exceptions, however, most of the scholarship on Reconstruction from the late nineteenth century to the 1960s ignored or denied the prominent role of African Americans in the era’s events. Blacks were rendered as the pawns and playthings of whites, whether they be white northerners or southerners. The most notable exception to this willful silence about blacks and Reconstruction was W. E. B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction (1935). Du Bois dissented from the then current interpretation of Reconstruction as a failed experiment in social engineering by placing the former slaves and the battle over the control of their labor at the center of his story. For him, Reconstruction was a failure not because blacks were unworthy of it but because white southerners and their northern allies sabotaged it. Not until the 1960s did a new generation of professional historians begin to reach similar conclusions. Spurred on by the civil rights struggle , which was commonly referred to as the “Second Reconstruction,” historians systematically studied all phases of Reconstruction. In the process, they fundamentally revised the portrait of African Americans. John Hope Franklin, in Reconstruction , Kenneth Stampp, in Era of Reconstruction , and others recast African Americans and their Republican allies as principled and progressive minded. By the 1970s, a subsequent wave of scholarship began to revise the largely positive take on the Reconstruction offered by Franklin, Stampp, et. al. Now Reconstruction was seen as an era marked by muddled policies, inadequate resources, and faltering commitment. William Gillette’s Retreat from Reconstruction (1979) was the fullest expression of this interpretation. Eric Foner’s Reconstruction synthesized the previous quarter century of scholarship on the period and offered the richest account yet of the role of African Americans in shaping Reconstruction. Foner also placed the accomplishments of Reconstruction in a comparative framework and concluded that the rights that the former slaves acquired during the era were exceptional when compared to those in any other post-emancipation society in the western hemisphere. Reconstruction may have left the former slaves with “nothing but freedom” but that freedom, Foner stressed, was written into the Constitution and was never completely compromised.

Since the publication of Foner’s work, most scholarship on Reconstruction has been devoted to topics that had previously been ignored by scholars. For example, the roles of black women , the struggle to develop a system of labor to replace slavery, and the emergence of black institutions have all been the focus of recent scholarly monographs. Two recent works that build on these works and suggest new directions for scholarship on Reconstruction are Heather Cox Richardson’s West From Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America after the Civil War (2007) and Steve Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, From Slavery to the Great Migration . Richardson highlights the importance of the Trans-Mississippi West in the political machinations and economic visions of the architects of Reconstruction while Hahn highlights the shared ideological values and cultural resources that sustained southern blacks in their struggle for economic and political power in the postbellum South.

W. Fitzhugh Brundage was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1995-96. He is the William B. Umstead Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Illustration credits

To cite this essay: Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. “Reconstruction and the Formerly Enslaved.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. DATE YOU ACCESSED ESSAY. <https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1865-1917/essays/reconstruction.htm>

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search

TeacherServe® Home Page National Humanities Center 7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535 Copyright © National Humanities Center. All rights reserved. Revised: May 2010 nationalhumanitiescenter.org

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Reconstruction

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 24, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Reconstruction (1865-1877), the turbulent era following the Civil War, was the effort to reintegrate Southern states from the Confederacy and 4 million newly-freed people into the United States. Under the administration of President Andrew Johnson in 1865 and 1866, new southern state legislatures passed restrictive “ Black Codes ” to control the labor and behavior of former enslaved people and other African Americans.

Outrage in the North over these codes eroded support for the approach known as Presidential Reconstruction and led to the triumph of the more radical wing of the Republican Party. During Radical Reconstruction, which began with the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, newly enfranchised Black people gained a voice in government for the first time in American history, winning election to southern state legislatures and even to the U.S. Congress. In less than a decade, however, reactionary forces—including the Ku Klux Klan —would reverse the changes wrought by Radical Reconstruction in a violent backlash that restored white supremacy in the South.

Emancipation and Reconstruction

At the outset of the Civil War , to the dismay of the more radical abolitionists in the North, President Abraham Lincoln did not make abolition of slavery a goal of the Union war effort. To do so, he feared, would drive the border slave states still loyal to the Union into the Confederacy and anger more conservative northerners. By the summer of 1862, however, enslaved people, themselves had pushed the issue, heading by the thousands to the Union lines as Lincoln’s troops marched through the South.

Their actions debunked one of the strongest myths underlying Southern devotion to the “peculiar institution”—that many enslaved people were truly content in bondage—and convinced Lincoln that emancipation had become a political and military necessity. In response to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation , which freed more than 3 million enslaved people in the Confederate states by January 1, 1863, Black people enlisted in the Union Army in large numbers, reaching some 180,000 by war’s end.

Did you know? During Reconstruction, the Republican Party in the South represented a coalition of Black people (who made up the overwhelming majority of Republican voters in the region) along with "carpetbaggers" and "scalawags," as white Republicans from the North and South, respectively, were known.

Emancipation changed the stakes of the Civil War, ensuring that a Union victory would mean large-scale social revolution in the South. It was still very unclear, however, what form this revolution would take. Over the next several years, Lincoln considered ideas about how to welcome the devastated South back into the Union, but as the war drew to a close in early 1865, he still had no clear plan.

In a speech delivered on April 11, while referring to plans for Reconstruction in Louisiana, Lincoln proposed that some Black people–including free Black people and those who had enlisted in the military –deserved the right to vote. He was assassinated three days later, however, and it would fall to his successor to put plans for Reconstruction in place.

Andrew Johnson and Presidential Reconstruction

At the end of May 1865, President Andrew Johnson announced his plans for Reconstruction, which reflected both his staunch Unionism and his firm belief in states’ rights. In Johnson’s view, the southern states had never given up their right to govern themselves, and the federal government had no right to determine voting requirements or other questions at the state level.

Under Johnson’s Presidential Reconstruction, all land that had been confiscated by the Union Army and distributed to the formerly enslaved people by the army or the Freedmen’s Bureau (established by Congress in 1865) reverted to its prewar owners. Apart from being required to uphold the abolition of slavery (in compliance with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ), swear loyalty to the Union and pay off war debt, southern state governments were given free rein to rebuild themselves.

As a result of Johnson’s leniency, many southern states in 1865 and 1866 successfully enacted a series of laws known as the “ black codes ,” which were designed to restrict freed Black peoples’ activity and ensure their availability as a labor force. These repressive codes enraged many in the North, including numerous members of Congress, which refused to seat congressmen and senators elected from the southern states.

In early 1866, Congress passed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights Bills and sent them to Johnson for his signature. The first bill extended the life of the bureau, originally established as a temporary organization charged with assisting refugees and formerly enslaved people, while the second defined all persons born in the United States as national citizens who were to enjoy equality before the law. After Johnson vetoed the bills—causing a permanent rupture in his relationship with Congress that would culminate in his impeachment in 1868—the Civil Rights Act became the first major bill to become law over presidential veto.

Radical Reconstruction

After northern voters rejected Johnson’s policies in the congressional elections in late 1866, Radical Republicans in Congress took firm hold of Reconstruction in the South. The following March, again over Johnson’s veto, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which temporarily divided the South into five military districts and outlined how governments based on universal (male) suffrage were to be organized. The law also required southern states to ratify the 14th Amendment , which broadened the definition of citizenship, granting “equal protection” of the Constitution to formerly enslaved people, before they could rejoin the Union. In February 1869, Congress approved the 15th Amendment (adopted in 1870), which guaranteed that a citizen’s right to vote would not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

By 1870, all of the former Confederate states had been admitted to the Union, and the state constitutions during the years of Radical Reconstruction were the most progressive in the region’s history. The participation of African Americans in southern public life after 1867 would be by far the most radical development of Reconstruction, which was essentially a large-scale experiment in interracial democracy unlike that of any other society following the abolition of slavery.

Southern Black people won election to southern state governments and even to the U.S. Congress during this period. Among the other achievements of Reconstruction were the South’s first state-funded public school systems, more equitable taxation legislation, laws against racial discrimination in public transport and accommodations and ambitious economic development programs (including aid to railroads and other enterprises).

Reconstruction Comes to an End

After 1867, an increasing number of southern whites turned to violence in response to the revolutionary changes of Radical Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations targeted local Republican leaders, white and Black, and other African Americans who challenged white authority. Though federal legislation passed during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871 took aim at the Klan and others who attempted to interfere with Black suffrage and other political rights, white supremacy gradually reasserted its hold on the South after the early 1870s as support for Reconstruction waned.

Racism was still a potent force in both South and North, and Republicans became more conservative and less egalitarian as the decade continued. In 1874—after an economic depression plunged much of the South into poverty—the Democratic Party won control of the House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War.

When Democrats waged a campaign of violence to take control of Mississippi in 1875, Grant refused to send federal troops, marking the end of federal support for Reconstruction-era state governments in the South. By 1876, only Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were still in Republican hands. In the contested presidential election that year, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes reached a compromise with Democrats in Congress: In exchange for certification of his election, he acknowledged Democratic control of the entire South.

The Compromise of 1876 marked the end of Reconstruction as a distinct period, but the struggle to deal with the revolution ushered in by slavery’s eradication would continue in the South and elsewhere long after that date.

A century later, the legacy of Reconstruction would be revived during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as African Americans fought for the political, economic and social equality that had long been denied them.

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Reconstruction era - Essay Examples And Topic Ideas For Free

The Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) was a period in American history following the Civil War, aimed at reintegrating Southern states and establishing rights for freed slaves. Essays on this topic might explore the policies implemented during this period, the successes and failures of Reconstruction, or the long-term effects on racial relations and socio-economic disparities in the United States. Alternatively, essays could focus on significant figures or specific events within the Reconstruction Era that influenced the course of American history. We have collected a large number of free essay examples about Reconstruction Era you can find at PapersOwl Website. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Political Leader Abraham Lincoln and the Reconstruction Era

The United States has gone through many political changes as a country. Presidents and political leaders have reoccurred, and they have all had distinctive goals and plans going forward. As time goes on, almost all these subversive eras come to an end. One era that has concluded, was the Reconstruction Era. The Reconstruction Era was a moment in America consisting of many presidents, destinations, and attainments. (Highlighted) Abraham Lincoln was one of the first individuals who came up with a […]

Harriet Tubman’s Sacrifices to Become an American Hero

Harriet Tubman is considered an American hero and an influential role model. She was a five-foot tall African American abolitionist who lead hundreds of slaves away from something that was considered inescapable. She is a well-known female that many people believe is inspirational. Harriet Ross Tubman, born Araminta “Minty” Ross, was born a slave on the plantation of Edward Brodess in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her mother was Harriet “Rit” Green, owned by Mary Pattison Brodess; and her father was Ben […]

Essay on Recostruction – Success or Failure?

Reconstruction was a complete failure. I believe this because even though Lincoln abolished slavery, black men still did not have equal rights to white men. This reconstruction period was from 1865 to 1877. During this period, blacks were getting frustrated because they might have gotten freedom, but they still were being treated like slaves. Lincoln’s plan to rebuild the South was that 10% of the state's population to take an oath of loyalty to the United States. As seen in […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Harriet Tubman Biography

Introduction Did you know that harriet tubman was an african american that helped many hundreds of slaves from the southern state get their freedom back. In addition Harriet Tubman built the underground railroad.Harriet Tubman was born in the 1820’s in Maryland. Harriet’s family and herself were slaves. “When Harriet Tubman was about 6 years old she was working” (Pebblego). Also harriet built the underground railroad too. You will also be learning about her early life. Early life In this paragraph […]

Harriet Tubman – Pioneer for the Underground Railroad

"During the early 19th century, Harriet Tubman was one of the pioneers for the Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad helped enslaved people escape to freedom through various passageways and routes1. The railroad consisted of a series of hidden passages and safe houses where escapees and abolitionists helped lead slaves to the North (and South) to freedom. These routes led African-American slaves to freedom to the free states and other countries such as Canada, Nova Scotia, and Mexico. Although the years […]

The Eerie Truth of the Underground Railroad

Most times when we acknowledge the Underground Railroad it brings up very controversial points of view all around the world. The Underground Railroad was a secret system that was put together to help fugitive slaves on their escape to be free; when you are involved with the Underground Railroad it was super risky, and also highly illegal (Eiu.edu). It lasted from 1861 to 1865 and was very loosely organized despite the massive quantities of people it helped (Underground Railroad ). […]

The Underground Railroad History

The Underground Railroad was very important in history by helping many slaves to escape. The Underground Railroad holds a fascinating history, many plots and plans to escape, as well as people that helped slaves to escape, but escaping was often dangerous due to multiple reasons. The Underground Railroad helped tremendously with slave escapes by means of all of the routes and safehouses set up along the country. Due to roughly 100,000 escaped slaves, there was a lack of workers which […]

Who Killed Reconstruction: Factors and Consequences

Introduction Keith Lewis Julia Bernier HIST 201 29 November 2018 Reconstruction Essay Reconstruction was the period from 1865-1877 when national efforts concentrated on incorporating the South back into a Union after the Civil War. Neither before nor since the Americans have had the opportunity to refashion a particular region within the nation. Reconstruction was a struggle fought on many fronts, but it experienced trouble between blacks and whites, northerners and southerners. Lincoln's Vision and the Thirteenth Amendment Lincoln described the […]

Early Abolition Movement in North America

The early abolition movement in North America was energized by both slaves' endeavors to liberate themselves and by gatherings of white pioneers, for example, the Quakers, who restricted slavery on religious or virtuous grounds. Although the transcending standards of the Revolutionary era invigorated the development, by the late 1780s it was in decline, as the developing southern cotton industry made slavery a perpetually essential piece of the national economy. On the contrary, in the mid-nineteenth century, another brand of radical […]

Feet Throbbing, Heart Pounding

Feet throbbing, heart pounding, and blindly trying to find the way. Scared to death, hoping and praying that their owner does not find them. Slaves endure many obstacles to try and escape, even though numerous of them fail. Thanks to the Underground Railroad thousands of slaves were able to escape. The Underground Railroad was made up of escape routes and places for runaway slaves to find assistance in their path to freedom. The Underground Railroad had a different terminology of […]

The Life of Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman also known as Araminta Ross was born on January 29,1822. She thought she was born in 1825 since they had no record. Her parents are Bob Ross and Harriet Greene she lived in Dorchester County, Maryland She was born into a slave family. She worked in the house until she was twelve. At twelve she was moved to the fields with her mother, father, and older siblings. When she was thirteen she had a 2 lb weight accidentally […]

The Legacy Unveiled: Revisiting Reconstruction’s Impact

End of Reconstruction stands how a zero hour in American history marking arrangement of violent period broken post-civil of War of people directed in renewal. With 1865 to 1877 Reconstruction tried to unite the recently emancipated African Americans in society give a kind new South politics and new economic roads of smithy. However his halt in 1877 marked a turning point in national politics and social mutual relations putting foundation for a later fight and progress. Moving away of federal […]

Transformative Measures: the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and their Enduring Impact

In the wake of the Civil War, the United States faced a monumental task of reconstruction and reconciliation. At the forefront of this post-war era were the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, a series of legislative initiatives aimed at reshaping the Southern states and redefining the fabric of American society. These Acts, fueled by the ideals of justice and progress, sought to address the aftermath of slavery while paving the way for a more inclusive future. A cornerstone of the Reconstruction […]

The Reconstruction Period: a Critical Turning Point in American History

Period reconstruction, that moved from 1865 at first 1877, gives only sediment from eras more above all and yield processing to American history. It was time social, politics, and economic deep shock, because actual unis was grabbed with investigation civil war and appeals melting millions African Americans recently exempt in fabric American society. It essay investigates keys aspects period reconstruction, distinguishes his the bends points and influence, that it has on patient nation criticize. War, that ends in 1865 civil, […]

The Onset of the Gilded Age: a Historical Overview

The Gilded Age, a term you might have come across in history classes, conjures images of opulence, towering skyscrapers, and sprawling mansions. Yet, beneath this surface glitter lies a complex narrative of economic growth, social upheaval, and technological innovation. The question of when this era truly began isn't straightforward, as it didn't start with a bang but rather evolved gradually through various significant events. Generally, historians agree that the Gilded Age roughly spanned from the 1870s to the turn of […]

The Historical Context and Lasting Impact of Black Codes in Post-Civil War America

Following the Civil War, the Southern United States witnessed a seismic shift with the emergence of the Black Codes, a set of laws designed to exert control over newly emancipated African Americans. These statutes cast a long shadow over Reconstruction, leaving an indelible mark on America's social and economic fabric. The Black Codes emerged in the tumultuous aftermath of the Confederacy's defeat and the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment. In response to the dismantling of their slave-dependent economy, […]

The Conclusion of Reconstruction: a Turning Point in American History

Reconstruction, era effluent American Civil War with 1865 to 1877, was marked deep changes and considerable revolution. His primary aims must were to renew South and unite the once enslaved people in American society how even citizens. However, determining, that detailed close to Reconstruction complicated, than straight, marking a date. Arrangement of period can be analysed through different political for lenses, social, and prawny-ka?da suggestion expressive prospect thereon, as well as when Reconstruction made off truly. The traditional eventual point […]

The Architects of the Black Codes: Examining the Authors and their Motivations

The conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865 marked the beginning of a transformative period for the United States, particularly concerning the integration of millions of newly freed African Americans into the social, political, and economic fabric of the nation. However, the hopeful vision of freedom and equality that characterized the Reconstruction era was significantly tarnished by the introduction of the Black Codes. These laws were systematically crafted to restrict the rights and liberties of African Americans, ensuring their […]

What was Reconstruction: Understanding Post-Civil War America

Reconstruction was a tumultuous and transformative period in American history, following the Civil War from 1865 to 1877. This era aimed to address the challenges of reintegrating the Southern states into the Union, rebuilding the South's devastated economy, and defining the new social and political status of freed African Americans. Understanding Reconstruction requires an exploration of its political policies, social dynamics, and the enduring legacy that continues to influence America today. The end of the Civil War in 1865 brought […]

The Radical Republicans: Architects of America’s Reconstructio

Amidst the turbulent currents of post-Civil War America, a cadre of American politicians within the Republican Party emerged as fervent champions for the eradication of slavery and the seamless integration of emancipated African Americans into the fabric of American society. Their influence reached its zenith during the tumultuous aftermath of the Civil War, a period marked by unparalleled national upheaval and profound metamorphosis. Guided by luminaries such as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, the Radical Republicans espoused a vision for […]

The States that Seceded from the Union during the American Civil War

A momentous juncture in U.S. history, the American Civil Conflict witnessed the withdrawal of eleven Southern territories from the Union, culminating in the inception of the Confederate States of America, a nascent nation spanning 1861 to 1865. Primarily propelled by disputes over states' prerogatives and the entrenched institution of servitude, this decision bore profound implications for the Southern socio-economic milieu. Scrutinizing the states' withdrawals and their impetus furnishes invaluable insight into the origins and repercussions of this tumultuous episode. Leading […]

The Impact of Black Codes on Reconstruction: a Critical Examination for APUSH Students

In the intricate dance of post-Civil War America, Reconstruction emerges as a pivotal chapter where the nation grappled with the aftermath of conflict and the promise of a new beginning. Central to this narrative are the Black Codes, insidious laws that emerged in the wake of emancipation, serving as a stark reminder of the entrenched forces of oppression and the complexities of forging a more equitable society. As students of APUSH embark on their academic journey, a critical exploration of […]

The Radical Republican Plan: Shaping Reconstruction and Civil Rights

Following the Civil War, a crucial epoch unfolded in American annals, characterized by endeavors to reconcile the nation and assimilate myriad liberated slaves into the socio-political fabric of the land. The Radical Republicans, a contingent within the Republican Party, wielded substantial sway during this juncture with a blueprint aimed at profoundly reshaping Southern society through assertive reforms and stringent oversight. Their approach to Reconstruction was both audacious and contentious, charting a trajectory with enduring repercussions on civil liberties and the […]

Andrew Johnson’s Approach to Reconstruction

Andrew Johnson, the seventeenth Commander-in-Chief of the United States, ascended to his position subsequent to the tragic assassination of Abraham Lincoln, amidst a pivotal epoch in American annals. His blueprint for Reconstruction, purposed to reinstate the Southern states to the Union post-Civil War, has been the subject of extensive deliberation and scrutiny. Johnson's methodology, characterized by clemency toward the South and scant safeguards for emancipated African Americans, starkly diverged from the more radical strategies advocated by his forerunners and contemporaries. […]

The Era of Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Symphony

Following the ravages of the Civil War, the United States embarked upon a grandiose and tumultuous period identified as Reconstruction. This epoch, spanning from 1865 to 1877, epitomized a phase of profound national introspection, endeavoring to reconstruct the fractured Union and confront the monumental injustices of enslavement. Nevertheless, the aftermath of Reconstruction is a saga of intricacy and paradox, characterized by notable achievements intertwined with disheartening setbacks. At the crux of Reconstruction lay the formidable task of assimilating myriad emancipated […]

The Reconstruction Act of 1867: a Cornerstone of Post-Civil War America

In the tumultuous aftermath of the Civil War, the United States grappled with the monumental task of rebuilding a fractured nation. Central to this effort was the Reconstruction Act of 1867, a legislative milestone that sought to redefine the social, political, and economic landscape of the South. This act was not just a policy; it was a bold statement of intent, signaling a commitment to address the injustices of slavery and to redefine the essence of American democracy. At its […]

Unpacking Lincoln’s Blueprint: a Fresh Perspective on Reconstruction Era

Within the annals of American history, Abraham Lincoln's blueprint for Reconstruction emerges as a beacon of hope in the aftermath of the Civil War. Far from a mere political strategy, Lincoln's plan encapsulated a vision of national healing and reconciliation, seeking to mend the deep wounds of division and chart a path towards a more inclusive society. Lincoln's approach to Reconstruction was grounded in the principles of compassion and pragmatism. Recognizing the need to reintegrate the Southern states into the […]

Reconstruction: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Rebuilding America

After the Civil War tore through the American South, leaving it in shambles, the nation embarked on a journey known as Reconstruction, aiming to stitch back together what was torn apart and bring into the fold millions of newly freed slaves. This era, from 1865 to 1877, was a whirlwind of high hopes and heartbreaks, making it a period that's both celebrated and lamented. First off, let's talk wins. Reconstruction wasn't all doom and gloom. It gave us the 13th, […]

| Dates : | Dec 8, 1863 – Mar 31, 1877 |

| Followed by : | Gilded Age; Jim Crow; Nadir of American race relations |

Additional Example Essays

- Personal Philosophy of Leadership

- Research Paper #1 – The Trail of Tears

- Rosa Parks Vs. Harriet Tubman

- PTSD in Veterans

- Basketball - Leading the Team to Glory

- History of Mummification

- The American and The French Revolutions

- Great Depression vs. Great Recession

- Levels of Leadership in the Army: A Comprehensive Analysis

- Was the American Revolution really Revolutionary?

- How are Napoleon and Snowballs leadership styles different?

- Similarities Between Zheng He And Christopher Columbus

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Reconstruction - Free Essay Examples And Topic Ideas

Reconstruction was aт age in America, comprising numerous leaders, objectives, and achievements. This means the rebuilding of the withdrawn states and the introduction of freedom into American culture amid and particularly after the Civil War. However, similar to everything throughout life, it came to an end and the result has been both a success and failure.

- 📘 Free essay examples for your ideas about Reconstruction

- 🏆 Best Essay Topics on Reconstruction

- ⚡ Simple & Reconstruction Easy Topics

- 🎓 Good Research Topics about Reconstruction

- 📖 Essay guide on Reconstruction

- ❓ Questions and Answers

Essay examples

Essay topic.

Save to my list

Remove from my list

- The Problem of Peace

- Historiography of the Reconstruction Era

- Reconstruction Era: Free But Not Equal

- Why was Reconstruction a failure?

- Civil War/ Reconstruction Dbq Essay

- North or South: Who Killed Reconstruction

- Successes and Failures of Reconstruction

- The Free State of Jones as a Historical Reference to The Reconstruction of The American South

- The Union Won The Civil War, and The Seceded States Won Reconstruction

- Reconstruction of The American South

- American Reconstruction – a Success with Exceptions

- The Successes and Failures of The Reconstruction Era

- Why Did Reconstruction Fail?

- The History of The Reconstruction of America

- A Study on The Discovery of America

- Analysis of How Reconstruction Was a Failure

- Dbq 10 Reconstruction: Us History

- Was Reconstruction A Success or a Failure?

- The Reconstruction Era

- Reconstruction Dbq Apush

- Reconstructionalism – Curriculum

- Differences Between the Wartime, Presidential, and Congressional Reconstruction

- Reconstruction DBQ

- DBQ Reconstruction

- Was The Reconstruction Success Or Failure

- Breakdown of U.s Citizenship with Reference to Historical Events on Different Races

- Reconstruction Era of the United States

- The Significance of Reconstruction in American History

- My Observations of the Era of Reconstruction

- Looking Back at the Era of Reconstruction

- Key Figures and Groups During Reconstruction