Essay on Science City

Students are often asked to write an essay on Science City in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Science City

Introduction.

Science City, a concept popular worldwide, is a hub where science is celebrated and explored. It’s a place full of interactive exhibits, planetariums, and laboratories.

What is a Science City?

Benefits of science city.

Science City provides an exciting way to learn science. It makes complex concepts easy to understand. It also encourages curiosity and creativity among students.

In conclusion, Science City is a wonderful place for students to explore and understand the wonders of science. It makes learning science fun and engaging.

250 Words Essay on Science City

The concept of science city, components of science city.

The core components of a Science City include universities, research institutes, high-tech businesses, and startups. These elements work synergistically to create an environment that encourages creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurial spirit. They also foster the sharing of ideas and resources, facilitating the transformation of scientific knowledge into tangible products or services.

Science Cities offer numerous benefits. They stimulate economic growth and job creation by attracting investment in high-tech industries. They contribute to social development by improving the quality of education and promoting scientific literacy. Additionally, they help address global challenges like climate change, health crises, and energy scarcity by promoting research and innovation in these areas.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite their potential, Science Cities face challenges such as maintaining a balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability, ensuring equal access to opportunities, and managing the rapid pace of technological change. However, with strategic planning and management, these challenges can be overcome. The future of Science Cities lies in their ability to adapt to changing circumstances, foster a culture of innovation, and contribute to sustainable development.

In conclusion, Science Cities represent a novel approach to urban development, offering a platform for scientific and technological progress, economic growth, and social development. They are a testament to the power of science and technology in shaping our future.

500 Words Essay on Science City

Science City, often termed as a city of the future, is an innovative concept that integrates science, technology, and urban living. The idea is to create a sustainable, knowledge-based environment that promotes scientific awareness and understanding, fostering a culture of innovation and creativity.

Components of a Science City

A Science City typically consists of several key components. First, there are educational institutions, which provide a steady stream of skilled workers and researchers. Second, there are research and development facilities, where new technologies and scientific breakthroughs are made. Third, there are businesses, which apply these innovations to create new products and services. Lastly, there are residential areas, where people who work in these institutions and businesses live.

Role in Promoting Innovation

One of the primary roles of a Science City is to promote innovation. By bringing together a diverse range of actors – from students and researchers to entrepreneurs and investors – Science Cities create a vibrant ecosystem where ideas can be exchanged, tested, and brought to market. They provide the infrastructure and resources necessary for innovation to thrive, including state-of-the-art labs, incubators, and funding opportunities.

Science City and Sustainability

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Science cities: Their characteristics and future challenges

- January 2004

- International Journal of Technology Management 28(3-6)

- Tampere University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

Science City Kolkata TRAVEL GUIDE

- How to reach

- Things to do

Science City is a science-centric museum located in Kolkata. Its main purpose is to increase interest in science among the common people. Its foundation was laid on 1 July 1997. There are many types of scientific things and facts presented in a very interesting manner. These b. s. Haldane is located in Avenue. There is an exhibition of illusions in one place, here are things like 'Power of tenses', 'Freshwater Aquarium', 'Live Butterfly Enclave', 'Science on a Sphere'.

The country's largest science center, Science City, Kolkata, is a unit of National Council of Science Museums, which is an autonomous body under Ministry of Culture, Government of India. It was developed with a onetime capital grant provided by the administrative ministry. Science city started on 01 July, 1997. Then there were two features in this - Science Center and (Centers). The science center campus includes space odyssey, dynamo, science exploration hall, marine center (maritime center), land-exploration hall and extensive park. Since its inception, about 29.90 million viewers have circulated so far, and it is also a center of attraction for the local residents of Kolkata, as well as for the foreign tourists coming to the city. Any person coming to Kolkata cannot be unaware of this prestigious institution, whereas unlike other science museums present in the country, there is a combination of education as well as entertainment. The land on which the waste of whole city was ever thrown for more than a hundred years, the work of that place was completely reversed by the creation of the science city with a science-festive and environment-friendly scenario welcoming on the same land.

How to Reach Science City

It is very well connected with all the significant methods of open transport. Nearby local buses, small transports, and metered taxis are effectively accessible from numerous part of the city. You can likewise profit nearby trains from Sealdah and get down at Bidhan Nagar station. From Bidhan Nagar station, there are shared auto rickshaws just as metered taxis. You can employ them and reach here.

Best Time to visit Science City

September to March. 9:00 AM - 9:00 PM

Science City Location

Things to see in Science City

Science City is an example of financial self-sufficiency for the public sector and with its revenues, it mobilizes its operations and maintenance expenses.

Illusion is a permanent exhibition in which Illusion of the world is displayed very interestingly. There are 43 display articles in ‘Power of Ten', which demonstrates the littlest biggest dimension of the universe increments or diminishes in extent to 10. The 'Freshwater Aquarium' located in it has a total of 26 tanks, in which a variety of fish is exhibited. There is also a great description of the biodiversity of fish. The butterfly exhibit is in 'Live Butterfly Enclave'. In this hall, a movie 'Painted Prajapati' keeps moving, in which the life cycle of the butterfly is shown. In this, a spherical projection system has been built on behalf of 'National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration' (NOAA), where the exhibition here can see 70 people simultaneously. This exhibition is 30 minutes total. Here is a science exploration house. Founded in 2016, this exploration house is spread over 5400 square meters. It has four main sections. According to the name, 'Emerging Technology Gallery', 'Evolution of Life - A Dark Side', 'Panorama of Human Evolution' and 'Science and Technology Heritage of India'. There is a huge theater in it, in which about 2200 people have the ability to sit together. Around 100 participants can display their art together on the platform created in it. There is also a 'Space Odyssey' 3-D Vision Theater, which is featured with the help of Stereo Beck Projection. Along with this, there are approximately 35 such exhibit items, which show an exhibition based on the reflection of light.

© Copyright 2018 Design By India Easy Trip All Rights Reserved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 23 January 2024

Cities matter to the world’s future — science must serve them better

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Mexico City has used research to inform policymaking for decades, but scientists struggle to get such work published in international journals. Credit: Getty

The numbers say it all: cities are hugely important to the world’s future but face big challenges. More than half of the world’s nearly eight billion people live in a city. Of those, 2.8 billion — the combined population of China and India — lack proper housing. For more than one billion individuals, home is in an informal settlement, and that number is rising. Some 90% live in Africa or Asia, according to 2020 data.

What’s more, few, if any, of the targets of the 11th United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 11) to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” are even within shouting distance of being achieved by the 2030 deadline. Some progress has been made in expanding access to public transport (currently available to around half of the world’s urban dwellers). However, “vast gaps” remain when it comes to achieving universal access to affordable homes, improving living conditions and reducing the environmental impact of cities, says the urban-development agency UN-Habitat (see go.nature.com/3srrcsq ).

Want a sustainable future? Then look to the world’s cities

There are gaps, too, when it comes to cities and science. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) need the kind of knowledge-based decision-making that is routine in high-income countries. And yet most research expertise is concentrated in rich nations, notes Eduardo Cesar Leão Marques, a political scientist at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, in a review article in the inaugural edition of Nature Cities ( E. C. L. Marques Nature Cities 1 , 22–29; 2024 ).

This, in turn, makes it harder for researchers in LMICs to publish their research on regions such as Latin America in journals based in the United States, says María José Álvarez-Rivadulla, a sociologist at the University of the Andes in Bogotá who has worked on cities in both areas. This is at least in part because reviewers don’t see such articles as relevant to readers who are based mainly in high-income countries. “You have to keep justifying why you study the cities that you study, because they are not in the global north and your research isn’t based in a rich university in a rich country,” she says.

A second, related, problem is that most existing research in, on or about cities falls in disciplines that don’t focus exclusively on urban environments. Studies on governance, climate and sustainability, public health, transport and other topics relevant to cities can be found in publications, including the Nature Portfolio journals, that serve their respective communities. But there are few journals that speak to all those working in the urban space and consider urban challenges across social divides.

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

That is where Nature Cities , which launched this month, aims to be different : it will publish research, commentary and journalism across the spectrum of urban issues. The journal intends to cross-pollinate the vast variety of urban-relevant research and thought and to reflect the variety and ways that scholars, practitioners and others are thinking about urban problems.

Take urban governance, which is an increasingly popular research topic. Participation in city governance by stakeholders from civil society and non-governmental organizations is key to achieving SDG 11. The good news is that city governments are being given more powers to make decisions that once might have sat with regional or national governments. Moreover, civil-society organizations are increasingly becoming involved, both in shaping and influencing policies and in providing services to communities. However, such engagement is under threat or becoming constrained in some regions, says UN-Habitat.

Clearly, there’s a mountain to climb on urban governance, boosting cities research in LMICs and reflecting under-represented voices in international research publishing. As part of our commitment to better highlight such challenges, last summer, the Nature Portfolio journals issued a call for papers on progress towards the SDGs . The aim is to energize the world’s research community so that it can play a bigger part in achieving them.

Cities are places where researchers and communities from different disciplines are having daily conversations — sometimes loudly, sometimes quietly, but often passionately. We hope that Nature Cities will provide a central square to do just that.

Nature 625 , 632 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00167-9

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

Our cities, ourselves

- Sustainability

Monitor soil health using advanced technologies

Correspondence 23 JUL 24

Freezer holding world’s biggest ancient-ice archive to get ‘future-proofed’

News 16 JUL 24

Regulate to protect fragile Antarctic ecosystems from growing tourism

Correspondence 09 JUL 24

Editorial 22 AUG 23

Weak links in finance and supply chains are easily weaponized

Comment 09 MAY 22

Trip frequency is key ingredient in new law of human travel

News & Views 26 MAY 21

The need for equity in Brazilian scientific funding

Correspondence 13 AUG 24

Canadian graduate-salary boost will only go to a select few

A hike of postdoc salary alone will not retain the best researchers in low- or middle-income countries

Assistant Professor Position in Genomics

The Lewis-Sigler Institute at Princeton University invites applications for a tenure-track faculty position in Genomics.

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, US

The Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University

Associate or Senior Editor, BMC Medical Education

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor, BMC Medical Education Locations: New York or Heidelberg (Hybrid Working Model) Application Deadline: August ...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Open Rank Professor of Pharmacology, Tenured/Tenure-Track

The Department of Pharmacology in the School of Medicine at the University of Virginia invites candidates for an open rank tenured/tenure-track fac...

Charlottesville, Virginia

University of Virginia - Pharmacology

Post-doctoral researcher (m/f/d) in (Marine) Microbial Natural Product Chemistry

GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Wischhofstraße 1-3, 24148 Kiel, Germany

Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel (GEOMAR)

Tenure-Track Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor

Westlake Center for Genome Editing seeks exceptional scholars in the many areas.

Westlake Center for Genome Editing, Westlake University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Imagining Future Cities in an Age of Ecological Change

Ursula heise, los angeles. 27 may 2019.

2 Comments Join our conversation

Very diverse in form, these 1,200 stories included science fiction, magical realism, speculative fiction, and fantasy. After many rounds of judging, fifty-seven of these stories from 21 countries were compiled into a book titled A Flash of Silver-Green: Stories of The Nature of Cities . Seven of those were judged to be prize-winners, authored by women from the United States, Canada, and India.

To place these stories in context, literary scholar Ursula K. Heise was asked to write an introduction that offers a cultural backdrop to work that tackles the future of cities from an environmental perspective. Her full introduction is included below, and the collection of stories can be purchased now from Publication Studio .

David Maddox, Executive Director, The Nature of Cities Curtis Walker, Production Coordinator, PS Guelph Malerie Lovejoy, Co-Editor, A Flash of Silver-Green

Floating cities. Flying cities. Domed cities. Drowned cities. Cities that flip over once a day to expose different populations to sunlight. Cities underground, in the oceans, or in orbit. Cities on moons, asteroids, or other planets. Cities of memory, of surveillance, or of violence. Speculative fiction in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has offered an enormous range of urban visions of the future, many of them dystopian, a few utopian, and quite a few somewhere in between.

For good reason: Cities have taken on a new centrality for human futures. In 2008, the World Health Organization and the United Nations published data showing that more than fifty percent of humans now live in cities, for the first time in the history of our species. By 2050, this figure is expected to rise to seventy percent globally. Much of this increase in urban populations will occur in Africa and Asia, often in cities that are not—or not yet—well-known globally. Some ecologists and demographers argue that this shift in where people live will be one of the crucial environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. Where earlier generations of environmentalists had worried about population increase as a problem in and of itself, these researchers shift the focus from the sheer number of people who will inhabit Earth to the kinds of habitats that will be built to house and employ them and to provide them with infrastructures of water, food, energy, health, education, justice, and governance. Since the new cities that will house twenty-first century people are only beginning to be built in many parts of the world, they offer enormous possibilities for constructing sustainable, healthy, and enjoyable places. But the social and ecological challenge is that many will be constructed informally, without the guidance of laws or building codes (or in defiance of regulations), let alone the input of urban planners, architects, or landscape designers—and even with such guidance, sustainability in fast-growing cities is of course far from assured.

The explosive growth in cities over the next century will entail far-reaching political, economic, social, and cultural consequences. And it will unfold in the context of ecological risks that range from local to regional and global scales: from soil, air, and water pollution to altered water and energy regimes, biodiversity loss, and climate change with its increased threats of droughts, floods, fires, and sea level rise. Many cities in the global South as well as the global North are already struggling to address these challenges—sometimes as a matter of sheer survival, sometimes as a matter of health and social justice, and sometimes as a matter of improved urban livability and aesthetics. Many new paradigms and concepts in urban ecology, urban planning, architecture, landscape architecture, design, and environmental activism have developed to engage with these issues over the last thirty years: ecological urbanism, urban political ecology, urban metabolism, urban environmental justice, biophilic design, and climate urbanism, to name just a few, have transformed the theory and to some extent the practice in these fields of research and activism.

Translating such principles and ideas into reality often requires a vision of the future of cities in the face of global ecological change. Between the promise of more livable and sustainable cities and the threat of a “planet of slums”, as the geographer Mike Davis has called it, artists, architects, and writers have frequently sought to outline such visions over the last half-century. From the Japanese Metabolism movement in architecture in the 1960s to the recent advocacy for biophilic design in the United States, architects have incorporated the forms and functions of organisms and biological structures into their building models. New Urbanists have developed principles for more walkable cities with a greater number of parks and green spaces. Designs for green roofs, vertical gardens, and urban farming are seeking to bring back some of the practices and products of nature that were driven out of the city during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Conscious of the global crisis in biodiversity, environmental activists are reintroducing native plants into city centers and educating urban dwellers to use their backyard spaces for the creation of wildlife habitat. Some geographers and anthropologists are even calling for a new “zoöpolis”, cities designed with the awareness that urban spaces are not just inhabited by one species—humans—but by many other species as well. Ideas such as these form part of an effort to transform ecological crises into points of departure for better-designed cities that integrate both humans and nonhumans into their cultural and economic values.

Artists, designers, and writers have all taken up these issues in their works. The 2010 MoMA exhibition Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront , curated by Barry Bergdoll, for example, focused on designs by artists and landscape architects that might protect Manhattan from rising sea levels and increasing storms due to climate change. Robert Graves and Didier Madoc-Jones’ Postcards from the Future, a series of speculative photo illustrations, reimagines London under conditions of large-scale migration and global warming. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change (2011), a book by architect and New Urbanism founder Peter Calthorpe, explores models for sustainable urban futures. Three volumes by the feminist and environmentalist Rebecca Solnit that focus on San Francisco, New York, and New Orleans, respectively, combine maps and texts to highlight patterns of social, economic, cultural, and ecological change in the three cities now and in the future. And science fiction, from David Brin’s Earth (1990) to Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 (2017), has eagerly explored visions of future cities in their relationship to nature.

One of the challenges in creating such a brief portrait of urban nature eighty years into the future is finding the right combination of global and local dimensions of urbanization. On one hand, the urban problems and opportunities the story deals with need to be recognizable to current readers hailing from different continents and languages: challenges associated with, for example, pollution, access to green spaces, gentrification, real estate ownership and use, disease, disasters, energy and water infrastructures, and governance, among many others. On the other hand, these general problems that affect cities around the globe need to link up, in a narrative, with enough local specifics to capture readers’ interest in a particular scenario—whether the locale is real or imagined.

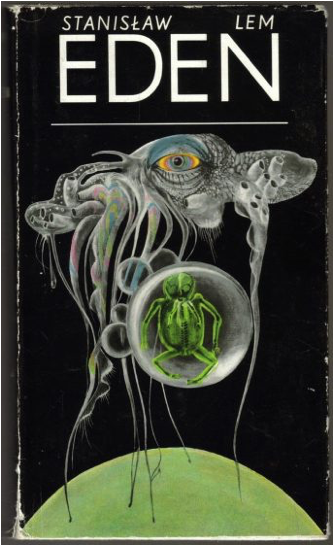

A second challenge concerns the combination of familiar and futuristic problems and solutions in the narrative. The portrayals of futuristic or alternative societies in speculative fiction and science fiction (terms that I will use interchangeably here so as to avoid delving into a debate of several decades’ standing about their identity or difference) need to contain enough familiar elements that they are still at least partially intelligible to readers. (The Polish science fiction writer Stanislav Lem, in his novels Eden [1958] and Solaris [1961], has eloquently thematized the enormous challenges that arise when humans traveling into outer space encounter planets and cultures that they have absolutely no grounds for understanding.) But stories about the future also usually contain what the science fiction scholar Darko Suvin has called the “novum”, the new element that turns a familiar scenario into one that does not quite map on to our present reality and thereby makes us look at our present in a new and different way. In this vein, Jonathan Lethem’s Gun, with Occasional Music (1994) and Sheri S. Tepper’s The Family Tree (1997) feature intelligent animals—descendants of animals used in biotechnological experiments in the twentieth century who are full members of future societies—as a way of making readers think in new ways about humans’ current relationships to nonhuman species.

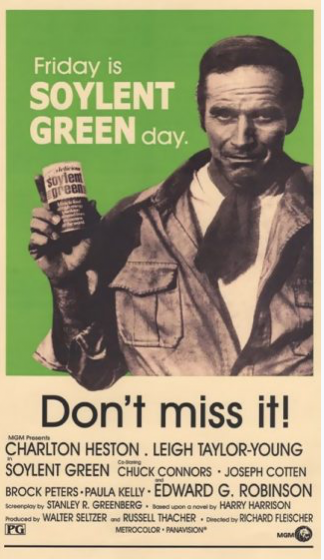

The literary scholar Fredric Jameson has put this in a somewhat different way by focusing on the typical time structure of futuristic texts. Science fiction makes us think critically about the present, he argues, by offering us a future in relation to which we have to re-envision our present as a past, the precursor to what the narrative portrays for us. This is, quite obviously, the principle of “cautionary tales” about the future, stories about societies that are considerably worse than our own or even dystopian. Descriptions of future totalitarian societies, dire scarcities, or ecological disasters in fiction and film—from Soylent Green (1973) to The Day after Tomorrow (2004)—are often meant to call on readers or viewers to beware of undemocratic, exploitative, or anti-environmental trends in the present.

The dystopian vision of the future was appropriated by writers interested in new media technologies as well as by environmentalists in the 1950s and 1960s. Kurt Vonnegut’s short story “EPICAC” (1950) and D.F. Jones’ novel Colossus (1960) foresaw computers taking over humans’ most personal relationships as well as world government. Rachel Carson adopted the dystopian genre to introduce her path-breaking book Silent Spring (1962) with a “A Fable for Tomorrow” that warned of a ghastly end to the agricultural heartland of America if the use of pesticides were continued, a vision that Brian Aldiss developed at a more global level in his science fiction novel Earthworks (1965). Paul Ehrlich similarly interpolated dystopian science fiction vignettes between the expository chapters of his nonfiction book The Population Bomb (1968), which warned of future starvation and misery if 1960s population growth rates continued into the future. A similar vision informed Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! (1966), which inspired the film Soylent Green , a vision that was shared by many other overpopulation fictions and films at the time. Implicitly or explicitly, dystopia continued to function as a tool for political criticism in these environmentalist works.

Over the last few decades, dystopian visions of the future have become standard in futuristic fiction and film. Fears about the loss of privacy and freedom in the digital age, about the consequences of biotechnology, the displacement of state by corporate power, aggravation of social inequality and economic exploitation, and about ecological catastrophe have resonated in texts as diverse as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), Edmundo Paz Soldán’s El delirio de Turing ( Turing’s Delirium , 2006), Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy (2003-2013), Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita’s Lunar Braceros 2125-2148 (2009), Efe Okogu’s “Proposition 23” (2012), Hao Jingfang’s “Folding Beijing” (2012), and Dave Eggers’ The Circle (2013), as well as in films such as Roland Emmerich’s 2012 (2009), Tarik Saleh’s Metropia (2009), and Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013). Young adult novels and films such as The Hunger Games (2008-2010) and Divergent (2011-2013) series similarly portray socially and ecologically devastated futures. If the dominant mode in science fiction is to be believed, post-apocalyptic wastelands will be as ordinary as parking lots, anarchy as predictable as taxes, and cannibalism as common as lunch at McDonald’s.

Cities are often central to such dystopian visions. The metropolis has, of course, functioned as the quintessential place where modernity unfolds in many twentieth- and twenty-first-century works of speculative fiction—as well as in many other forms of contemporary art and literature. It is often presented as a material manifestation of societies to come, in both their best and their worst dimensions—from the latest achievements in commerce, communication, and transportation to the worst excesses of squalor, inequality, and oppression. Utopian views of cities have become rare in science fiction in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, though they do still emerge occasionally. Kim Stanley Robinson’s descriptions of New York City in his novels 2312 (2012) and New York 2140 , for example, foreground the ingenious ways in which New Yorkers have recreated their city after climate change and sea level rise, transforming it into a latter-day version of Venice. Both novels show how what seems to a twenty-first century reader like one of the most artificial and human-dominated environments on the planet can appear as an exhilaratingly natural habitat to off-worlders used to living in sealed-off domes, with the outside accessible only in spacesuits.

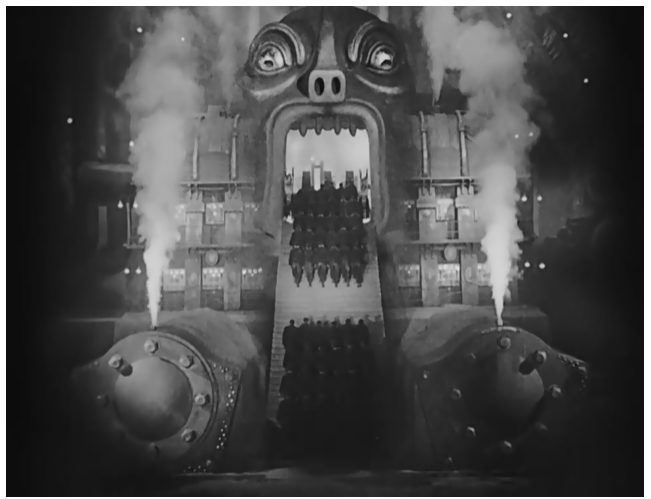

Dystopian views of cities make up the overwhelming majority of futuristic urban literature and film. The nightmarish social inequality of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1929) has found echoes in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013), all films in which poverty and wealth are made visible through spatial segregation—to the point where in Blade Runner and Elysium , the wealthy migrate off planet, leaving contaminated and impoverished cities behind on Earth. In recent novelistic dystopias such as Eden Lepucki’s California (2014) or Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus (2015), the city is what the protagonists need to leave behind to escape the worst consequences of social and environmental collapse. And in the most extreme story pattern, a science fiction narrative that is by now over a hundred years old, charismatic metropolises need to be reduced to ashes and rubble before a new social order can emerge. In a by now classic essay called “The Literary Destruction of Los Angeles”, Mike Davis, surveying the films and fictions up to the mid-1980s, blamed the persistence of this narrative template on underlying racism. Visions of London, New York, or Los Angeles destroyed, he argued, fulfilled a racist white fantasy of getting rid of the multiracial and multicultural urban masses. In more recent scenarios of wholesale urban destruction, the fantasy arguably addresses a much broader desire to see modern society with its track record of complexity, inequality, and environmental damage erased in favor of simpler, more egalitarian, and more sustainable ways of life. Often, these post-apocalyptic returns to life without the modern city amount to futuristic visions of the pastoral: from the utopian village community in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) to Howard Kunstler’s World Made by Hand (2008) and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam (2013), the life of the future takes place outside the city.

Dystopian scenarios also appeared in the submissions to The Stories of the Nature of Citiescontest, for example in the highly surveilled and controlled cities of Tatiana Shashkova’s “June Bugs in Glass Jars” and Louise Nzomo’s “Escape from the Butterfly Apartments”, or in Tasha Kerry Smith’s “City of the Last Breath”, where those who cannot afford living in luxury compounds are shipped off to work in submarine settlements while drugs slowly kill them. Daniel Uncapher’s “Dandelion and the Floodshark”, meanwhile, approaches dystopia and apocalypse in an ironic vein in the manner of British novelist China Miéville. Many other entries also foreground the persistence of economic inequality and racial discrimination, and they engage seriously with misguided uses of technology, environmental risk, and degraded nature, showing how these problems may continue and even become aggravated in the future. But a great number of stories present far more optimistic visions of urban futures. Quite a few of them show ways in which future urban societies have adapted to changed ecologies and worked to address if not to eliminate the gaps between the rich and the poor.

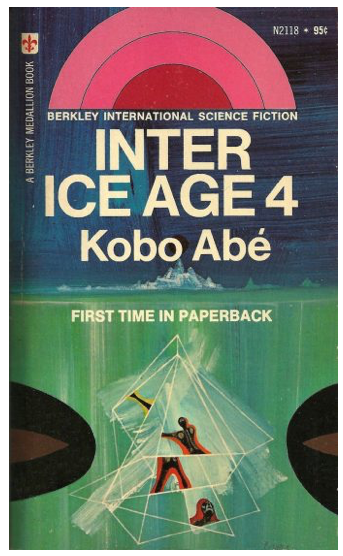

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the recurring theme of the flooded city. The city sinking beneath the waves is an age-old trope of speculative literature that one can trace all the way back to Plato’s Atlantis. In the twentieth century, it features prominently in hundreds of speculative fictions from Kobo Abe’s Inter Ice Age Four (第四間氷期, Dai-Yon Kampyōki [1959]), J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World (1962), and Sakyo Komatsu’s Japan Sinks (日本沈没, Nihon Chinbotsu [1973]) to recent novels such as Frank Schätzing’s Der Schwarm ( The Swarm, 2004), Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl (2009), and Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From (2017). Since the turn of the millennium, the drowned city has increasingly come to be associated with climate change and rising sea levels, ecological processes that have given an old literary theme a new contemporary resonance.

Many of the fictions in A Flash of Silver-Green: The Stories of the Nature of Cities allude to global warming or even focus on it as their central theme. But not all of them envision it according to the familiar story template of the disaster movie—the end-of-the-world catastrophe that only a select few survive, often centrally featuring a nuclear family with a heroic father figure. Instead, Alyssa Eckles’s “Uolo and the Idol” imagines a drowned city where piles of rusting cars have become habitat for new coral reefs and a vibrant marine biodiversity that has replaced agriculture as a food source for the human inhabitants. Claire Miye Stanford’s “Neither Above Nor Below” focuses on one of the currently most precarious cities, the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, which is threatened both by the soil subsidence that has followed from decades of aquifer depletion and by rising sea levels. In Stanford’s vision, Jakarta 2099 is “the only city in the world that had found a way to coexist with the rising tides”, a latter-day Venice that has become a global model by letting the water in and creating an entirely new environment for humans and nonhumans. In stories such as these, the drowning city as the melancholy icon of a civilization’s end morphs into a symbol of hope and a new urban way of living in and with nature.

This hopeful vision also predominates in stories that envision future cities as multispecies environments that encourage new bonds between humans and nonhuman species. In Elizabeth Twist’s “May Apple”, this takes the form of rituals that initiate city dwellers into the care of a particular plant, while in L.H. Metzger’s “Ecology” similar scientific attention to individual plants has led to an abundantly fertile and verdant urban landscape. In Amanda White’s “Listen”, biotranslators allow plants and ants, wolves, and worms to make their voices heard in meetings where humans discuss the future of the city. Mariusz Loszakiewicz’s “Tree” envisions cities that grow in trees, and that even the most recent technology is produced by tree growth.And in Joanne Bristol’s lyrical meditation “from eaves to footfall”, the boundaries between human and nonhuman, city and nature become so fluid that one often cannot be told from the other. Stories such as these see ecological crisis as a gateway to a new awareness and a new attribution of value—both cultural and economic—to the natural world and nonhuman species.

But Arakali’s, Lakshminarayan’s and Towey’s stories also highlight the underside of this renewed appreciation of green spaces: the gentrification of nature that makes access to parks a prerogative for the elite or only a temporary respite from landscapes that otherwise offer few experiences of plants and animals. In this vein, Sierra Adler’s “The Cathedral” features a domed park, from which the protagonist inevitably has to return to “normal” urban life without nature. Jenni Juvonen takes this scenario one step further in her story “Where Grass Grows Greener” by making the experience of “pure, authentic nature” one that is best accessed through virtual reality and by those who can afford its exorbitant cost. And Ari Honarvar’s “A Child of the Oasis” portrays a futuristic eco-utopian Paris only to highlight that the city is blocked to most of the desperate migrants fleeing from other regions of a planet in crisis. Stories such as these put questions about urban nature in 2099 firmly into the context of environmental justice, the question of who gets to benefit from nature and who does not, and who is exposed to ecological risks and who is not.

The contributors to this volume, then, reflect on a wide range of urban issues, from socioeconomic inequality, energy, water, transportation, and architecture all the way to population control, species extinction, and climate change. They offer vibrant visions of future cities, from tightly surveilled dystopias to urban eco-topias, sometimes democratically open and sometimes oligarchically closed. As the best writers to have emerged from this contest, their stories link their reflections on a particular locale and specific individuals to global urban and ecological processes and crises. In the process, the city often comes to function as a microcosm of planet Earth, challenging readers to imagine both the enormous heterogeneity and the unifying issues and institutions that shape planet-spanning societies. By offering a wide spectrum of visions of what urban futures at the end of the twenty-first century might look like, the stories collected here provide a vibrant inspiration to reimagine our cities even and especially in the face of the radical ecological changes that the twenty-first century has already begun to face.

Ursula Heise Los Angeles

On The Nature of Cities Also published by our partner, ArtsEverywhere.ca

Banner art by Katrine Claassens

Abbott, Carl. 2016. Imagining Urban Futures: Cities in Science Fiction and What We Might Learn from Them. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Bergdoll, Barry, Michael Oppenheimer, Guy Nordenson, and Judith Rodin. 2011. Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Calthorpe, Peter. 2011. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change . Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Carson, Rachel. 2002 [1962]. Silent Spring . New York: Houghton Mifflin. 40th anniversary edition.

Davis, Mike. 1998. Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster . New York: Henry Holt.

—. 2006. Planet of Slums. London: Verso.

Ehrlich, Paul. 1968. The Population Bomb . Cutchogue: Buccaneer.

Heise, Ursula K. 2008. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global . New York: Oxford University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 2005. Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions . London: Verso.

Lee, Kai N., William R. Freudenburg, and Richard B. Howarth. 2013. Humans in the Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Studies . New York: Norton.

Solnit, Rebecca. 2010. Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. Oakland: University of California Press.

—. 2013. Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas . Oakland: University of California Press.

—. 2016. Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas . Oakland: University of California Press.

Suvin, Darko. 2016 [1979]. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre . Ed. Gerry Canavan. Bern: Peter Lang. New edition.

UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Population Division. 2008. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision . New York: United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wup2007/2007WUP_Highlights_web.pdf .

UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). 2007. State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth . New York: United Nations Population Fund. http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2007 .

UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlement Programme). 2007. The State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/2007: Thirty Years of Shaping the Habitat Agenda . London: Earthscan for UNHabitat. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11292101_alt.pdf .

Wolch, Jennifer. “Zoöpolis.” 1998. Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands . Ed. Jennifer Wolch and Jody Emel. London: Verso, 1998. 119-138.

About the Writer: Ursula Heise

Ursula Heise is the Marcia H. Howard Chair in Literary Studies at the Department of English and the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA. Her research and teaching focus on contemporary literature and the environmental humanities; environmental literature, arts, and cultures; science fiction; and narrative theory.

2 thoughts on “ Imagining Future Cities in an Age of Ecological Change ”

Check at http://www.storiesofthenatureofcities.org now. The submission form is up and available.

Hello there. I’m a writer looking to submit a story for this year’s competition and I’m not entirely sure on where to submit it. Can anybody help me?

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Other Essays on: 26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

There is a difference between equality and equity. Equality says that everybody can participate in our success and equity says we need to make sure that everybody actually does participate in our success and in our growth. A just city is a city free from both inequity and inequality. We...

What has happened is that in the last 20 years, America has changed from a producer to a consumer. And all consumers know that when the producer names the tune, the consumer has got to dance. That’s the way it is. We used to be a producer—very inflexible at that,...

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology. Johannesburg’s development into a wealthy, white core of business and residential activity, with peripheral black dormitory townships, was a result of...

In 1993 or thereabouts I entered a contest for women to depict what they did on a particular day. That day, I went to meetings early in the morning at Harlem Hospital. I took photos of the abandoned buildings on West 136th, where I parked my car, and photos of...

OTHER ESSAYS ON SIMILAR THEMES...

Science & tools.

“Science cannot solve the ultimate mystery of nature. And that is because, in the last analysis, we ourselves are part of nature and therefore part of the mystery that we are trying to solve.” — Max Planck As a graduate student,...

PEOPLE & COMMUNITITES

Today’s post celebrates highlights from TNOC writing in 2017. These contributions, originating around the world, were widely read, offer novel points of view, are somehow disruptive in a useful way, or combine these characteristics. Certainly, all 1000+ TNOC essays and roundtables are great and worthwhile reads, but what follows will give you a taste of this year’s key and diverse content. 2017 has been an...

PLACE & DESIGN

Today’s post celebrates some of the highlights from TNOC writing in 2018. These contributions—originating around the world—were one or more of widely read, offering novel points of view, and/or somehow disruptive in a useful way. All 1000+ TNOC essays and roundtables are...

ART & AWARENESS

I recently spent a month in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and have been reflecting on my experience ever since. Chiang Mai is a beautiful and vibrant city, rich in culture and history. The Buddhist religion permeates every aspect of the city...

Science City Ahmedabad

- About Place

About The Place : Located off the Sarkhej Gandhinagar Highway, Science City is an ambitious initiative of the government of Gujarat to trigger an inquiry of science in the mind of a common citizen with the aid of entertainment and experiential knowledge. Covering an area of more than 107 hectares, the idea is to create imaginative exhibits, virtual reality activity corners, and live demonstrations in an easily understandable manner.

Gujarat Science City is a bold initiative of the Government of Gujarat to realize this priority. The Government is creating a sprawling center at Ahmedabad which aims to provide a perfect blend of education and entertainment. It will showcase contemporary and imaginative exhibits, minds on experiences, working models, virtual reality, activity corners, labs and live demonstrations to provide an understanding of science and technology to the common man

Science City : https://sciencecity.gujarat.gov.in

Attractions:

Robotics Gallery : An interactive gallery that demonstrates the development in the domain of robotics. A socially skilled humanoid robot welcomes guests and introduces them to the facility.

Aquatic Gallery : It takes visitors on a memorable voyage to the aqua world that features India's largest public aquarium with a state-of-the-art life support system.

Nature Park : Spread over an area of more than 20 acres, the Nature Park is a crown to the adventures of Science City. It houses a Mist Bamboo Tunnel, an Oxygen Park, a Butterfly Garden, a Colour Garden, a Chess and play areas for children.

Amphitheatre : Gujarat Science City's Amphitheater (Open Air Theater) has a total capacity of 1200 people and conducts scientific events, particularly science popularization. Learners and community leaders may promote an atmosphere where scientific facts and statistics meet the thrill, passion, and power of the stage for a little innovation.

Energy Park : Energy Education Park covers a total area of nearly 9000 square metres in a hexagonal grid pattern. The five elementary aspects (Panchbhuta) of ancient Indian philosophy are used to classify the exhibitions at Energy Park.

Hall Of Science : The Hall of Science is a large open research facility where guests can participate in practical learning displays and study science via exploration. It encourages visitors to interact with the displays by touching and operating them, as well as learning about the intriguing science underpinning them.

Hall Of Space : With high-resolution pictures and visitor-interactive digital control displays, the space exploration zone chronicles important breakthroughs in space research and development.

LED Screen : The 1,84,320 tiny LEDs on the large LED (Light Emitting Diode) screen at Gujarat Science City, which measures 20 x 12 feet, are used to portray characters or show narratives.

Life Science : Its goal is to bring scientific knowledge and ecology to the experience of children and to inspire them to learn about nature, man, and their progression, as well as the multiplication and survival of life on our planet. The major goal of this immersive outdoor park is to inspire youngsters to learn about nature and to become interested in the evolution, dissemination, and survival of life forms.

Planet Earth : Its goal is to raise public awareness, instruct, and teach people about natural calamities such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and landslides, as well as to promote our planet's stunning splendour and bountiful realities.

IMAX 3D : The IMAX experience is the most impactful and immersive film experience globally. IMAX technology transports you to never-before-seen worlds with spectacular pictures up to eight stories high and surround-sound 12,000-watt digital audio.

Science Programs : The programs and events held at Science City nudges the young minds with scientific questions and open the window to the discoveries and facts that run the world.

Tuesdays to Sundays - 10 AM to 8 PM (Closed on Mondays)

Photo Gallery

How to get there

Nearby Attractions

Where To Stay

Registered Tour Operators

Bhagwati holidays.

| Mobile | |

| Website |

Bharat Darshan Travels

Birla tourist & transport services, registered tourist guides, maunish prakashbhai bhavsar.

| Mobile |

Naman Ramaiya

Prahlad m samdani, related experiences.

My Study Times

Education through Innovation

Brief Report on Visit to Science Centre

Science city

Yesterday I have visited science city which is located at Ahmadabad in Gujarat. Which is very big and well established institute? There were science fair of schools and a huge dome for 3d movie. We reached there by bus and when we saw the entrance of the science city we were on cloud nine. We just felt like we have become junior scientists. There were so many wards like ancient middle and latest models.

When we reached there dr.barta come to receive us and welcomed us very warmly. Then we were given breakfast. It was so delicious then we entreated the huge dome which is in shape of earth which is planetarium where we saw stars and planets which was amazing experience.

Then we entered in aerospace and plane compartment where there were so many planes were placed and space shuttle too. And there were a ride name space ride which gave us a real space travelling experience.

Then we saw new invention and ongoing research and dr. batra gave some light on some basic s of physics and space. Which boosted up our mind?

The-n we entered where we were given 3d glasses and we were so exited to watch movie the name of movie is rajasouras. Which was about the dinosaurs which was very good experience.

Then we took refreshment and spent some time in garden where there was a pond having fishes we fed them and enjoyed a lot.

Then we left for home with such a great memory of science city this visit really changed my way to see my surrounding world.

About Charmin Patel

Blogger and Digital Marketer by Choice and Chemical Engineer By Chance. Computer and Internet Geek Person Who Loves To Do Something New Every Day.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Science and the city: comparative perspectives on the urbanity of science and technology parks

2014, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy

Related Papers

Interdisciplinary Science Reviews

Åsa Lindholm Dahlstrand

R & D Management

Koenraad Debackere

This paper examines the role of university science parks in fostering interorganizational technology transfers and technological development. We first try to contrast the development of science parks with the theoretical and empirical findings from scholarly work in the area of the management of technology. This theoretical context allows us to interpret and to discuss empirical data collected from Belgian and Dutch science park firms. The data collection mainly focused on the interactions of park-based firms with their external R&D environment. This analysis leads to two important findings: (1) the level of R&D activity at the tenants is rather moderate for most of the parks studied, and (2) the tension between ‘regionalism’ and ‘internationalism’ in contemporary R&D management.In the wake of this second finding, arguments are presented to complement and even to change the focus from the ‘miniature’ R&D network which might develop on university science parks toward the ‘R&D community’ network holding together researchers working on a particular, interrelated set of scientific and technological problems wherever they may be located around the globe. Moreover, it is argued that a unified theory on the emergence and the development of new technologies is badly needed. Only if the dynamics underlying the development of a new technology are unravelled and better understood can technology policies, such as the ones involving the creation of science parks, be targeted more effectively.

Jacques van Dinteren

Xiaohui Hu , Robert Hassink

Alcino Pascoal

The concept of Science Park dates back to mid-50s and the strategic considerations undertaken at North Carolina, with critical contributions from academia and inestimable state governor support. This newly approach to link University with private business did have its burdens and drawbacks, until financial partners were engaged and there was a clearer view about the institutional setup. Research Triangle Park followed shortly after, whenever these issues were sorted-out. Europe followed too such trend, albeit a few years later. Sophia-Antipolis was one of the primary names to emerge (early 70s), whereas year 1984 witnessed the incorporation of International Association of Science Parks. This can be seen as a direct result of the significant role science parks were playing in terms of heightening socioeconomic development. European policies started also to reflect these changing paradigms, having proceed to the implementation of political/funding instruments targeted to such endeavours. Scientific concern beyond this work in progress addresses key characteristics of a Science Park, deemed essential for a sound operation and the fulfilment of its mission statement. Triple helix model is embedded still within Science Parks, but has evolved into more complex structures. Technology hub, entrepreneurship ecosystems and innovation ecosystems are but a few of recent denominations. The later have been used to better describe the fuzzy reality of Science Parks and their performance metrics in terms of A) ability to retain talents; B) network significance; C) accelerator capacity and D) science-to-the-market delivery. This work consists of a reflection about innovation models followed by Science Parks, quoting some EU-based examples. There's a discussion about recent trends, heavily influenced by external factors such as the scarcity of resources; sustainability; the individual; green economy. Way ahead encompasses smart specialisation and strategic thinking, being the paper a contribution for the analysis of regional dynamics which are Science-Park centred. Science Park concept: a historical insight The Science Park concept is not new: actually it has emerged back in the mid-50s, whenever some strategic considerations were undertaken at North Carolina. These have been supported both by academia and the state governor (Luther Hodges in such a case) whose enrolment was decisive at the time. Such a disruptive approach aiming at to strengthen the linkage between University and private businesses did have however plentiful burdens and drawbacks. That was the situation until the financial partners were enrolled and there was a clearer view as regard to the institutional setup. The Research Triangle Park (later referred to as RTP) followed shortly afterwards, as soon as all these issues have been tackled in a timely manner. The triangle vertexes comprised three university poles, It must be said that the decentralised model of RTP as far as the academia is concerned was followed closely by a concurrent endeavour dating back also to the 50s, more precisely to California and the eponymous Stanford University. It consisted of the first brick of what was known by then as Stanford Industrial Park (later renamed Stanford Research Park) and nowadays Silicon Valley. Whenever speaking about " The Valley " the one refers to the location of numerous fast growing high-tech companies. These contemporary examples have several common characteristics, that is: 1) the geographical dispersion, not restricted to a small conurbation but rather a large area. Current RTP campus spans over an area of approximately 2.800 ha (Cirillo, 2013), whilst Silicon

Technovation

Daniel Felsenstein

International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management

Paolo Landoni

Research Policy

Myriam Cloodt

Scientometrics

Robert Tijssen

New Technology-Based Firms in the New Millennium

Gert-Jan Hospers

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Proceedings of the 30th World Conference on Science and Technology Parks, International Association of Science Parks and Areas of Innovation - IASP, Recife, Brazil

Roberto M Spolidoro , Sisty One Co-authors

Serbian Journal of Management

Andrea Dobrosavljevic

R&D Management

Stuart Macdonald

Ricardo Martinez Cañas

Triple Helix Journal

Marcelo Amaral , Jéssica Souza Maia

Firas Thalji

Jakob Vestergaard , Finn Hansson

RAI Revista de Administração e Inovação

FEP Working Papers

Alexandre Almeida

Diego Ramos

EMBO reports

Andrea C. Rinaldi

International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development

Gemma Durán-Romero

Katerina Ciampi Stancova

Technological Forecasting and Social Change

Aurelia M Modrego

David Wield

European Journal of Innovation Management

Finn Hansson

Scientific Bulletin – Economic Sciences

Ramona Florina Popescu

Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy

Jennifer Clark

International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research

ilaria mariotti

Ashraf M . H . Mansour

International Journal of Industrial Organization

Albert Link

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- University City Science Center

By John L. Puckett

The University City Science Center, the nation’s first and oldest urban research park, represents a pivotal chapter in the story of American urban renewal, its associated racial tensions, and the important role played by institutions of higher education. Established in 1960 in West Philadelphia adjacent to and intertwining the campuses of the University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University as part of an urban renewal zone, the Science Center expanded to include sixteen buildings on its seventeen-acre campus, becoming in the process a key player in the economic and cultural vitality of University City.

The University City Science Center was conceived as part of “Unit 3,” an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority that included the West Philadelphia blocks from Powelton and Lancaster Avenues south to Chestnut Street between Thirty-Fourth and Fortieth Streets. The properties were redeveloped in conjunction with the West Philadelphia Corporation, an institutional coalition that included the University of Pennsylvania as the senior partner and the Drexel Institute of Technology (now Drexel University ), the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia ), Presbyterian Hospital ( Penn Presbyterian Medical Center ), and the Osteopathic Medical School ( Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine ) as the junior partners.

Planners envisaged the University City Science Center as a catalyst for the economic, cultural, and scholarly efflorescence of University City, a brand name and marketing gambit they devised for the blocks that included or bordered on the West Philadelphia Corporation’s member institutions. As recruitment magnets for the Science Center and the scientists and scholars they hoped to attract, the West Philadelphia Corporation dedicated human and monetary capital across University City to school-improvement initiatives, housing conservation, and condominium developments, a guaranteed mortgage plan for University of Pennsylvania employees, arts and culture, beautification, recreation, and retail and restaurant development in the Walnut Street corridor. The Science Center was to rise one block deep along both sides of Market Street between Thirty-Fourth and Thirty-Eighth Streets and below Market between Thirty-Ninth and Fortieth Streets. According to Jean Paul Mather (1914–2007), the Science Center’s first president, research and development was the center’s primary objective—either through its own efforts or by facilitating office or laboratory space for industry, independent foundations, and member institutions.

Previously established university-related research parks that might have served as models were located in spacious, bucolic surroundings. While University City planners did not discount the extraordinary advantage that swaths of pastoral landscape conveyed to Stanford University’s Industrial Park , which included such wildly successful tenants as Hewlett-Packard, General Electric, and Lockheed, or to the heavily wooded Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, they gambled that the University of Pennsylvania’s brand and the promise of urban amenities would convey a distinct advantage for recruiting high-tech industries. In the fall of 1963, the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas approved articles of incorporation for the University City Science Center and the University City Science Center Institute. The Science Center was the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority’s designated real estate developer for the entire complex. In this role, the Science Center assumed the obligation under the urban renewal plan for Unit 3 to put up buildings “within a reasonable time as determined by the Redevelopment Authority” on properties it acquired from the authority. The Science Center Institute, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Science Center, was to conduct its own research and development under Science Center management. Recognizing from the start that the project would rise or fall on its ability to attract the research arms of major corporations such as IBM and General Electric to the Market Street corridor, planners assigned the highest priority to recruiting such organizations.

Racial Demographics

Science Center planners denied charges that they conspired to construct a buffer zone that would insulate Penn from working-poor blacks in Mantua and Belmont, neighborhoods north of Unit 3. Yet there was no denying that the type of professionals the Science Center hoped to recruit would be overwhelmingly white, simply by virtue of the racial demographics of higher education and the learned professions of the 1960s. Unit 3 redevelopment, with the University City Science Center at its core, thus effectively created a barrier between Penn and its neighbors to the north.

As demolitions began to displace working-poor blacks in the Market Street corridor, a neighborhood known locally as the Black Bottom, racial politics flared. Of the 2,653 people displaced in Unit 3, roughly 78 percent were black. The Science Center and the projected Science Center-affiliated University City High School caused just over half of the total Unit 3 displacements. Protests by displaced residents and their West Philadelphia allies, including student demonstrators at Penn, fell on deaf ears at the Redevelopment Authority and the West Philadelphia Corporation, which managed the affair with hubris and insensitivity to the probable consequences of the removals, one of which was to be lasting damage to Penn’s community relations.

Adding to the original membership, the Science Center evolved as a consortium of some thirty-one educational and medical institutions throughout the Delaware Valley, although the University of Pennsylvania continued to hold a majority of the corporation’s stock in the 1960s and a plurality of its stock thereafter. Headquartered in a converted industrial building purchased in 1965, the Science Center opened its first new building in 1969 and successfully recruited the Monell Chemical Senses Center to its complex in April 1971. Despite that initial success, other major corporations with research and development departments, apparently wary of an area they regarded as a vestigial slum, failed to follow.

In its early years, the Science Center was undercapitalized and under constant pressure from the Redevelopment Authority to put up buildings regardless of their function. To meet its payroll and to hold the Redevelopment Authority at bay, the center reconfigured itself as a real estate operation by offering space to organizations regardless of whether they had a research focus. The General Services Administration , for example, constructed a fifteen-story office building on the corner of Thirty-Sixth and Market Streets to house the regional units of four federal agencies—a purpose that had nothing to do with research or development.

Strategic Redirection

Randall Whaley (c.1916–89), a technology innovator, became president of the Science Center in 1970, by which time the center was financially beleaguered and losing $30,000 per month. Under Whaley’s leadership, however, the center achieved financial stability, reporting its first operating surplus in 1973. As his signal contribution, Whaley restructured the Science Center as the nation’s first small business incubator in science and technology. In 1983, the Science Center was designated an Advanced Technology Center for Southeastern Pennsylvania (ATC/SEP)—one of four regional ATCs established under the auspices of the Commonwealth’s Ben Franklin Partnership (later renamed the Ben Franklin Technology Partners ), created by Gov. Richard Thornburgh (b. 1932) in 1982. Consistent with the partnership’s guidelines, the ATC/SEP developed an incubator program with business-development support services. Contrary to the original vision of national research laboratories occupying single buildings, emphasis shifted to start-up ventures housed in multi-tenant buildings. By 1984, the incubator had launched forty-four small businesses; by the spring of 1987, the total number was 106 start-ups.

By 1984 the center boasted nine buildings in the Market Street corridor between Thirty-Fourth and Thirty-Ninth Streets and counted twenty-eight colleges, universities, and hospitals as shareholders. By 1988, the number of organizations it hosted was up to 105, employing over six thousand people. The center’s total capital investment reached more than $90 million, returning more than $68 million in cumulative city wage and real estate taxes. The center did manage to attract some research and development activity, including a number of federally funded research projects sponsored by the University City Science Institute and projects among tenants such as the Connective Tissue Research Center (for example, research on the structure, immunology and molecular biology of basement membranes in diabetes, a study of lung endothelial cells’ response to infection and injury) and NASA’s Bioprocessing and Pharmaceutical Research Institute (research on processing pharmaceuticals and biological materials in space). Yet over the years, it remained dependent on non-R&D entities to balance its books. Organizations such as the Otis Elevator Company, the Radiation Management Corporation, the John Hancock Health Plan, and the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools claimed significant space there.

Although they were usually able to find tenants for the existing multistory office buildings, Whaley and his board were continuously stymied by a lack of funds to complete the research park. A development first proposed in 1965, deemed essential to the Science Center’s claim to be a bona fide, world-class research park, was the World Forum for Science and Human Affairs. Conceived as the Science Center’s signature development, this initiative would have featured a spectacular residential hotel with state-of-the-art facilities for conferences, seminars, and continuing education programs. Whaley, a high-minded thinker, undaunted optimist, and crusader for innovation, latched onto the idea shortly after his arrival in 1970, and it remained his idée fixe until his retirement in 1985, even as the project siphoned off time and money from other projects. Every developer who considered taking on the project ultimately backed away, however. As one deal after another fell through and the requisite financing never materialized, the center finally shelved the project in 1992.

In the summer of 1983, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority extended the Science Center’s contract for fifteen years, giving the corporation a grace period within which to complete the research park. The center subsequently leased its leveled properties between Thirty-Sixth and Thirty-Eighth Streets to the Parkway Corporation , which laid down parking lots. In the following decade, the Science Center confronted a loss of R&D dollars and an outmigration of many of its resident technology companies to suburban Pennsylvania, an exodus attributed to the burden of the city’s wage tax and the lack of flexible facilities—for example, laboratories and light manufacturing space—in the mid-rise research park.

Renaissance

In the mid-1990s, on the wings of the Clinton-era economy, the Science Center experienced a financial resurgence and physical growth spurt that continued, with the exception of the 2008 recession, for the next twenty years. In these decades, the center also benefited from a national zeitgeist that favored the revitalization of core areas of once historically vital cities in the Northeast Corridor. Urban research parks adjacent to major universities were suddenly au courant. The Science Center emerged as a major player in a University City building boom that began with the University of Pennsylvania’s commercial redevelopment of Walnut Street at the turn of the millennium and culminated with Drexel’s dramatic expansion and commercial redevelopment along Chestnut and Market Streets. Forming a phalanx of anchor institutions along a two-mile swath of the Schuylkill River’s west bank, Penn, Drexel, and the Science Center complemented, and intertwined with, each other’s astonishing growth. University City was poised to challenge Center City as a hub of urban redevelopment.

Commensurate with Randall Whaley’s vision of a science and technology incubator, in 2000 the Science Center debuted an eight-story building at 3711 Market Street housing the Port Business Incubator , organized to assist start-ups in biotechnology and information technology. Additions to the incubator included Quorum , a program that provided informal meeting spaces and liaison services for matching entrepreneurs and investors, and QED Proof-of-Concept , a program designed to help academic researchers in the life sciences and healthcare fields develop commercially viable information technologies. Drexel and the Science Center opened a 17,500 square-foot Innovation Center for business incubation on two floors of 3401 Market, a building that shared Thirty-Fourth Street with the rapidly growing Drexel campus.

By the mid-2010s, the Science Center had become a thriving engine of economic development for high-wage and middle-wage workers on the corporation’s Market Street campus. It was also a boon for talented entrepreneurs striving to launch small businesses in life sciences, clean tech, IT, bioinformatics, nanotechnology, and diagnostics and devices, as well as for the employees of these incubated businesses and their clientele. Two new buildings along the north side of Market between Thirty-Seventh and Thirty-Eighth Streets served as bulwarks of the Penn Health System—3701 Market Street for outpatient primary care and 3737 Market, a sparkling eleven-story tower that houses the Penn Presbyterian Medical Center’s integrative specialty medical services and outpatient treatment options. A low-rise “flex” building with laboratory and other tailorable spaces opened at 3615 Market. Drexel acquired a Science Center building in the 3401 block of Market, formerly the Institute for Scientific Research, a research indexing service, for its College of Media Arts and Design. The eyesore surface parking lot on the 3601 block of Market to Filbert, once earmarked for the Whaley’s World Forum, became the site of a twenty-eight–story postmodernist apartment tower with ground-story retail development.

In the planning stage in 2016 was uCity Square, a development formed in partnership with Wexford Science and Technology, a biomedical realty company. Bounded by Thirty-Seventh and Thirty-Eighth Streets between the line of Filbert and the point where Powelton Avenue joined Lancaster Avenue, it was designed to be a vibrant live/work/play neighborhood of postmodern residential buildings, a high-end grocery store, boutique retail venues, and interior walkways and public spaces. However, for all the realized and potential economic benefits of the University City Science Center, an open question remained as to whether its major reorganization of urban space and displacements of West Philadelphia’s poor and minority residents would help mitigate Philadelphia’s status as the nation’s poorest large city and the city with the highest level of deep poverty.

John L. Puckett is a professor in the Education, Culture, and Society Division of the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. A co-founder of the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, he teaches academically-based community service courses at Penn, and he has been active in community organizing around schools in West Philadelphia. Among other books, he is a co-author of Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and Dewey’s Dream: Universities and Democracies in an Age of Education Reform (Temple University Press, 2007). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

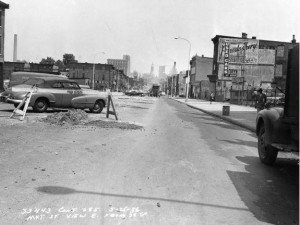

Market Street Before Construction of the University City Science Center

PhillyHistory.org

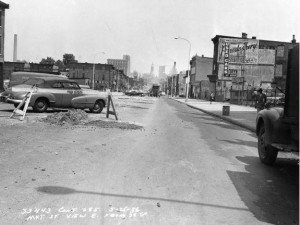

Prior to the construction of the University City Science Center, the Market Street corridor was a low-income, mixed residential and commercial district largely populated by working-class African Americans. The neighborhood was densely constructed with two- and three-story row houses and tenement buildings, many with retail and local-service operations on their ground floors.

The Science Center was conceived during an ambitious wave of urban renewal in the 1960s that sought to reverse the city's decline by attracting middle class residents, many of whom had left for the suburbs in the decades following World War II, back into the city. West Philadelphia’s Market Street corridor was one of the areas targeted for urban renewal. In conjunction with the Redevelopment Authority, the Science Center was organized by planners of the West Philadelphia Corporation, a nonprofit entity that served the area’s higher education and medical institutions and was dominated by the University of Pennsylvania.

Community Meeting with the Redevelopment Authority, 1965

Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries

Plans to demolish Unit 3, an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, for the construction of the University City Science Center met with resistance from the community. Demolition of Unit 3 would require the displacement of the residents of the Black Bottom, a largely working-class African American neighborhood along the Market Street corridor. The Redevelopment Authority held meetings with the community, such as this one in 1965 at the Drew School, in advance of the demolitions, but residents' pleas were to no avail. The neighborhood was declared blighted and demolished.

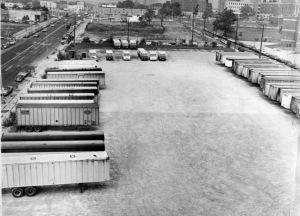

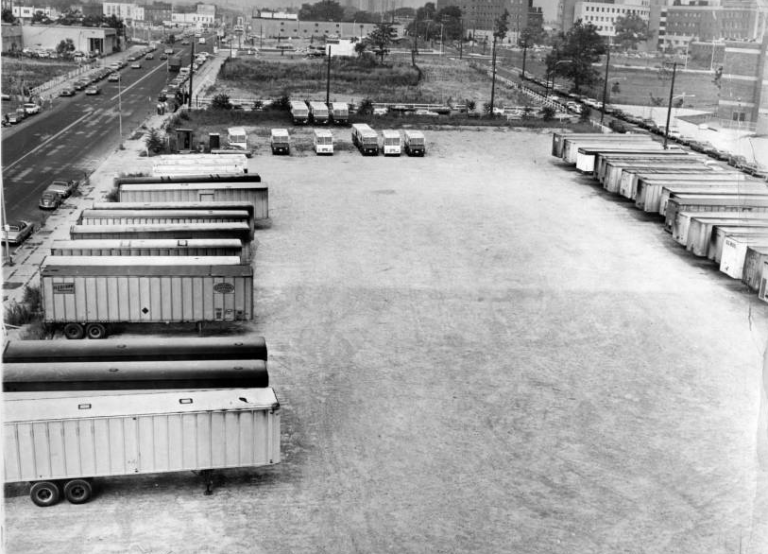

Aerial View of the Science Center Under Construction

This 1968 aerial photograph shows the University City Science Center in its early days. The project required the demolition of residences along Market, Filbert, and Warren Streets. Just over half of the displacements caused by the project took place to clear the land for the University City High School, shown here bordered by a trapezoidal fence in the lower left. Planned during an ambitious period of public school reforms in Philadelphia, the University City High School was to serve as a magnet school, attracting top-tier math and science students from across the region. The curriculum would offer a unique, individualized program for each student, without schedules or structured class periods.

Community friction combined with overcrowding in other schools and a change in the city's political climate subverted these lofty goals. University City High School opened in 1971 and was quickly forced to abandon its high-toned curriculum as an influx of new students from neighboring schools transferred to the new facility, regardless of academic aptitude. Difficulties staffing the new school adequately led to violence, including a 1972 incident where the student body took over the school and the Philadelphia Police Department's gang-control units were forced to intervene. The school's reputation was permanently tarnished. It closed in 2013 and was demolished.

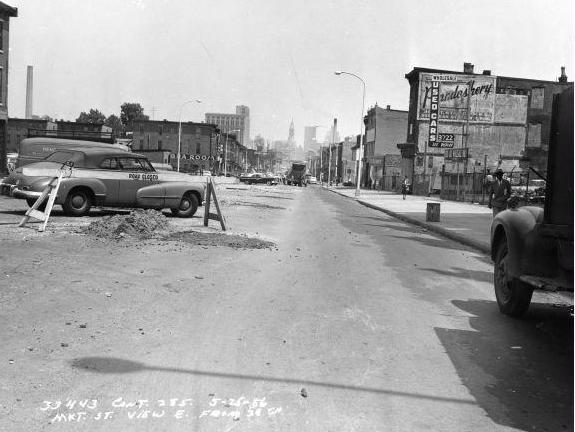

Residences Cleared for Construction

Despite community opposition, the Black Bottom neighborhood was demolished for the construction of the University City Science Center. This photograph shows two clusters of houses standing, awaiting the relocation of the families residing in them. Since 1984 and continuing into the twenty-first century, the former residents of the Black Bottom and their families convened annually for a picnic in remembrance of the neighborhood. The picnic, held in Fairmount Park, was made official in 1999, when the Philadelphia City Council recognized the second Sunday in August as Black Bottom Day.

University of Pennsylvania Students Hold a Sit-in