An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Prevention, screening, and treatment for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder

Justin knox , ph.d., deborah s hasin , ph.d., farren r r larson , m.a., henry r kranzler , m.d..

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence Deborah S. Hasin, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, 1051 Riverside Drive, Box 123, New York, NY 10032, USA, Phone: 646-774-7909; Fax: 646-774-7920, [email protected] ; [email protected]

Contributors

JK did the initial data collection (literature search) and wrote the first draft of the paper. DSH and HRK contributed to the literature search coverage, contributed to interpretation of the findings and revision of the writing, and contributed short sections of the paper. FRRL contributed to the writing and revision of the paper, and to the design and creation of the tables and figure.

Issue date 2019 Dec.

Heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD) are major public health problems. Practitioners not specializing in alcohol treatment are often unaware of the guidelines for preventing, identifying, and treating heavy drinking and AUD. However, a consensus exists that clinically useful and valuable tools are available to address these issues. Here, we provide a critical review of existing information and recent developments in these areas. We also include information on heavy drinking and AUD among individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders, including drug use disorders. Areas covered include prevention; screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment (SBIRT); evidence-based behavioral interventions; medication-assisted treatment; technology-based interventions (eHealth and mHealth); and population-level interventions. We also discuss the key issues that remain for future research.

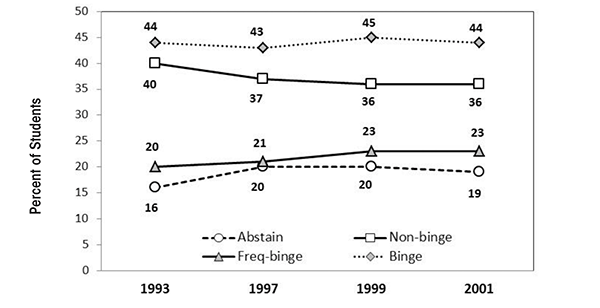

Heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD) are major public health concerns

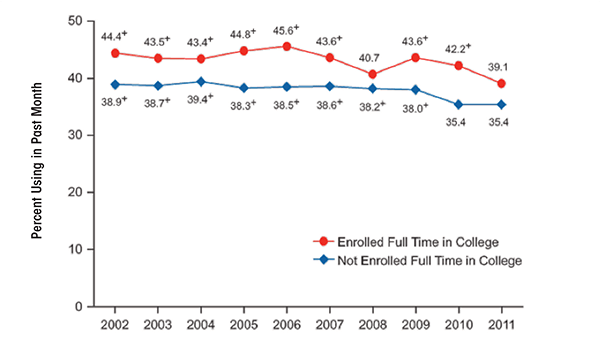

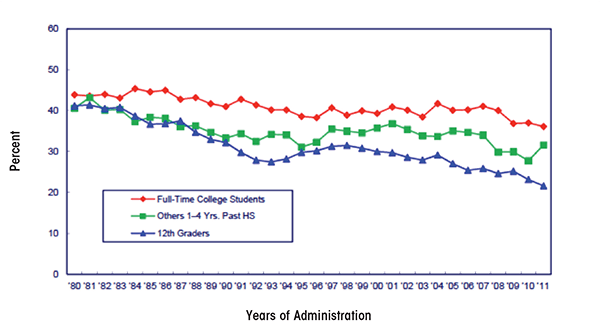

Alcohol consumption is prevalent worldwide. In 2016, 2·4 billion people (33% of the global population) were current drinkers. 1 In the United States, specifically, the prevalence of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and high-risk drinking in adults has increased substantially over the past ten years. 2 One in eight U.S. adults report past-year high-risk drinking, 2 and the prevalence of lifetime AUD is high. 3 In the United Kingdom, the prevalence of heavy drinking and AUD are also high. 4

In this paper, we primarily discuss heavy drinking and AUD. Many measures of alcohol consumption (e.g., heavy drinking, binge drinking) and alcohol-related disorders (e.g., harmful drinking, alcohol dependence, AUD) are used, and often, these reflect geographical preferences. For example, in the United States, Canada, and many other parts of the world, the diagnostic system of choice is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which was updated from the 4 th edition (DSM-IV) to the 5 th edition (DSM-5) in 2013. The United Kingdom and other European countries tend to use the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system to diagnose mental health conditions, including alcohol-related disorders. Overall, there has been good agreement between DSM and ICD diagnoses, with DSM-5 AUD capturing a wider and different aspect of problematic use than the diagnosis of alcohol dependence used in the ICD and previously in DSM-IV. 5 - 7 The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and the first three items from the AUDIT focused on consumption, known as the AUDIT-C, 8 , 9 are additional measures developed and validated by the WHO for international use which are common in the literature.

Alcohol use is a leading global cause of disease burden and substantial health loss. 1 Risk of all-cause mortality is positively associated with the level of alcohol consumption, such that any level of consumption is potentially harmful. 1 These findings are consistent with the well-demonstrated relationship of heavy drinking and AUD to numerous adverse health consequences, 2 , 3 , 10 , 11 and to morbidity and mortality worldwide. 12 - 14 Heavy drinking and AUDs also place psychological and financial burdens on individuals who engage in these behaviors, as well as their families, friends, coworkers, and society as a whole. 15 , 16 Compounding the seriousness of this problem, many individuals with AUD who could benefit from alcohol treatment, including those with severe disorders, do not receive it. 2 , 3 , 17 - 19 For example, in the United States, only about 8% of individuals with past-year AUD are treated annually in an alcohol treatment facility. 20

Despite the known adverse health consequences and prevalence of alcohol use (including harmful alcohol use), many practitioners outside the specific areas of alcohol specialization are not knowledgeable about the guidelines for preventing, identifying, and treating heavy drinking or AUD. In this report, we review existing information and recent developments in the prevention, identification, and treatment of heavy drinking and AUD. Whenever available, we include information about heavy drinking and AUD among individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders, including drug use disorders (DUD), as these disorders are highly prevalent among persons who drink heavily. 3 , 17 , 21 - 24 There is also a greater risk of relapse among individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders who receive alcohol treatment. 25 As a result, there is a recognized need to address the interrelationship of co-occurring alcohol use and mental health disorders through innovative approaches or adaptations of traditional treatments.

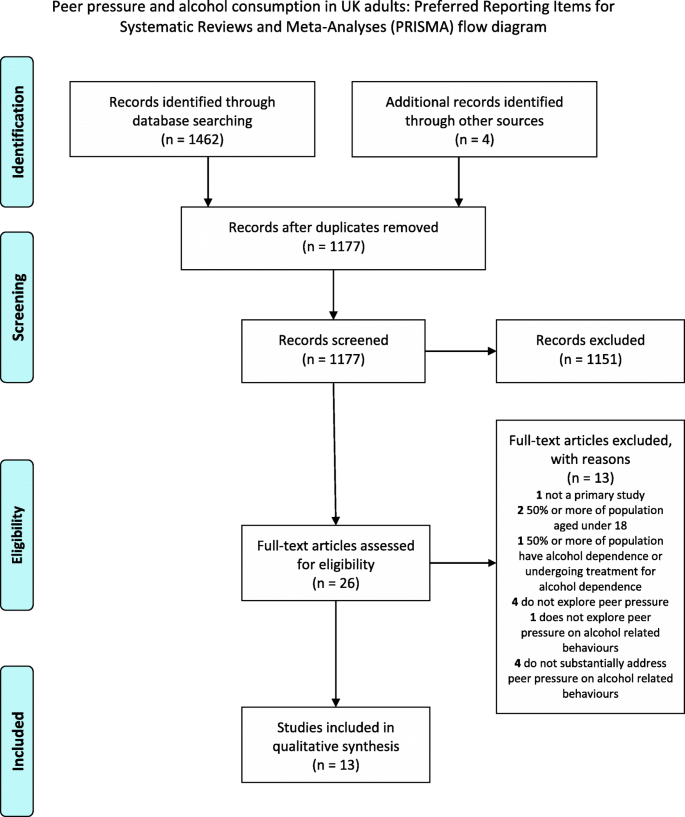

Search strategy and selection criteria

References for this review were identified through searches of PubMed for articles by use of the terms “alcohol,” “heavy drinking,” or “alcohol use disorder,” in combination with “prevention,” “school-based intervention,” “SBIRT,” “behavioral intervention,” “medication assisted treatment,” “technology,” or “population-level intervention.” Articles resulting from these searches and relevant references cited in those articles were reviewed. Articles deemed to have relevant information on preventing, identifying, and treating heavy drinking or AUD were included, with a focus on new developments, unresolved controversies, previous reviews, widely-cited studies, and literature about heavy drinking and AUD among individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders (including DUD), when it was available. Only articles published in English were included.

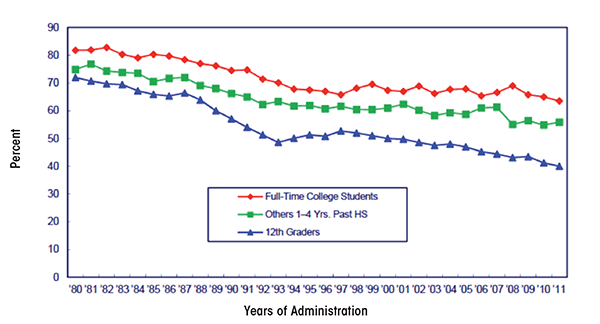

Preventing heavy drinking and AUD

Adolescence is a critical period for the initiation of alcohol use as the age at first drink occurs, on average, at 14 years in the United States 26 and 17 years globally. 27 Therefore, efforts to prevent heavy drinking and AUD are often targeted at youth before they usually begin drinking, and most of these efforts are implemented through schools. A systematic review of school-based interventions concluded that they can be an effective approach to alcohol prevention, at least in the short term. 28 However, another review noted that while school-based interventions increased knowledge and improved attitudes regarding drinking, evidence does not support their sustained effect on behavior. 29 Further, a review conducted in 2009 and updated in 2017 concluded that although alcohol education programs in schools and higher education settings are popular interventions, the evidence does not support their effectiveness. 30 , 31 An important direction for future research in this area would be to obtain more information on the short- and long-term efficacy of school-based alcohol prevention interventions. 28

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral for Treatment (SBIRT) for heavy drinking and AUD in clinical settings

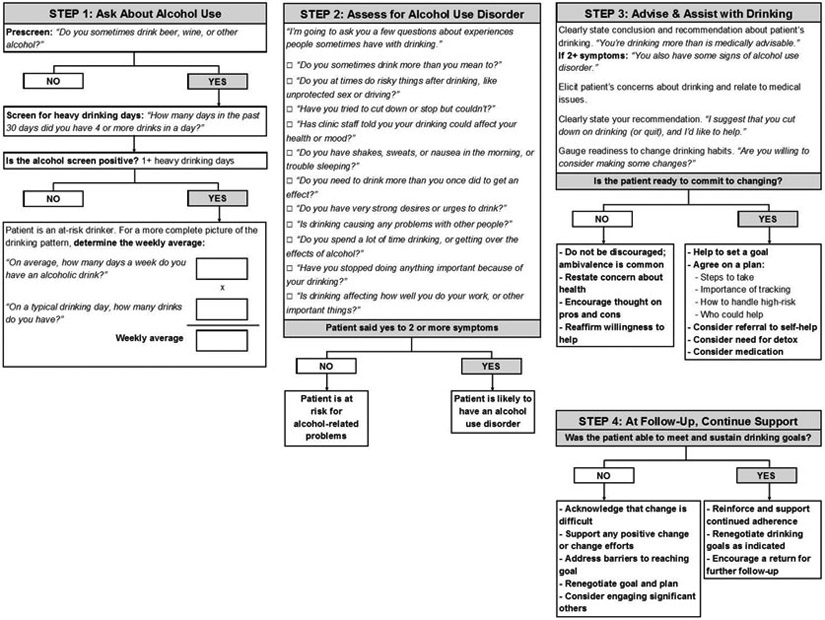

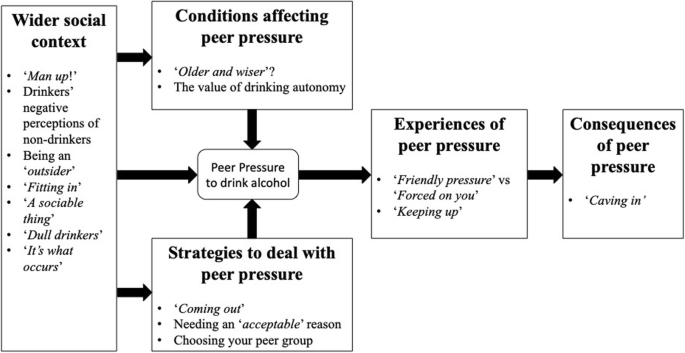

Interactions with healthcare providers across a variety of clinical settings present a valuable, yet underutilized opportunity to engage with patients about their alcohol consumption. 32 - 34 Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is a paradigm designed for use by healthcare providers who are not specialists in alcohol treatment to identify and reduce harmful drinking, thereby reducing the risk of alcohol abuse and dependence. Figure 1 illustrates the steps involved in SBIRT, as adapted from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Clinician’s Guide. 33 , 34 SBIRT has also been expanded to address illicit drug use. 35 - 37

Screening for heavy drinking and AUD, adapted from the NIAAA Clinician’s Guide 34

Harmful alcohol use, including AUD, is the target of alcohol screening. Two screening tools for alcohol use have been recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 38 The AUDIT-C, which comprises the first three items of the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), focuses on the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, including binge drinking. 8 , 9 Alternatively, a single question related to the frequency of binge drinking (defined as five or more drinks in a day for men and four or more drinks in a day for women) can be used. 39 Either tool can readily be incorporated in the clinical encounter.

Brief interventions.

According to SBIRT guidelines, brief interventions are recommended for patients who screen positive for harmful drinking but are not alcohol dependent. In general, brief interventions to reduce heavy drinking in primary care are effective in reducing drinking 36 , 40 - 42 and improving health outcomes. 43 Brief interventions can range in practice from very brief advice to theory-driven intervention, such as trained motivational interviewing. 40 - 42 , 44 , 45 Despite the different evidence-based behavioral treatment frameworks available (see discussion below), 46 current brief intervention efforts in the United States focus mostly on MI approaches aimed at motivating clients to change substance use patterns. 47 The number of sessions of brief treatment offered depend on the program and the patient, including his or her severity of drinking.

Referral for treatment.

Brief intervention has limited effectiveness among individuals with more severe alcohol problems, 42 , 48 - 59 including many who screen positive using the most widely used screening instruments. Referral to treatment may be more useful for this population, which often requires more intensive intervention. 34 , 60 - 65 However, the referral component of SBIRT is limited by the low rate at which individuals with severe alcohol problems follow up on referrals. 40 , 66 - 71 This occurs for a number of reasons, including concerns about stigma, 72 lack of interest in abstinence goals, 73 , 74 preference for self-sufficiency, financial barriers, and doubts about treatment efficacy. 18

SBIRT and patients with comorbid drug problems.

Individuals who drink heavily or have an AUD often use other substances, in many cases to the point of having a DUD. 17 In the U.S. general population, individuals with past-year AUD were three times more likely to have a DUD than those without a past-year AUD. 24 DUDs are prevalent and have been increasing. 75 - 77 They involve clinically significant impairment due to the recurrent use of drugs, 24 , 78 - 83 and create additional societal burden through their association with crime, incarceration, poverty, homelessness, and suicide. 78 , 79 , 81 , 83 SBIRT has been used as a paradigm to guide clinical interactions for individuals with combined illicit drug and alcohol use, with initial evidence of effectiveness. 84 Although calls have been made to implement SBIRT more widely, concerns exist about its efficacy. 85 - 87 This has led some individuals to suggest completely re-thinking the SBIRT model when drugs are involved, 88 while others suggest co-locating care management within primary care settings, including counseling about treatment options. 71 This remains an issue for further research and debate.

SBIRT implementation: Screening.

Despite the availability of validated screening tools, less than 25% of U.S. adult binge drinkers report ever being asked by a health professional about their drinking. 89 Reasons for this low percentage include individuals’ variable engagement with the healthcare system, providers’ lack of time due to competing priorities, and physicians’ concerns that patients will not accurately self-report their drinking. 90 The United Kingdom National Screening Committee does not currently recommend population screening for alcohol misuse due to concerns about the specificity of screening tools, variability in their cut-offs, and lack of evidence linking population screening to reduced alcohol-related harm. 91 However, in integrated healthcare systems where screening is mandated and built into the electronic medical record system, screening can be nearly universal, as it is in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system. 92

SBIRT implementation: The whole package.

SBIRT has been implemented across a range of clinical care settings around the world, including hospital emergency departments, community health clinics, specialty medical practices (e.g., sexually-transmitted disease clinics), primary care, and other community settings. 93 In the United States, in response to an Institute of Medicine call for increased community-based screening for health risk behaviors (including alcohol use), 94 SBIRT has been scaled up substantially over the past 15 years. 37 For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a clinical guideline for clinicians to screen all adults for alcohol misuse, and provide persons engaged in risky or hazardous drinking with brief behavioral counseling interventions. 39 In addition, the Joint Commission on Accreditation for Health Care Organizations, the major accrediting body for hospitals in the United States, now uses implementation of SBIRT as a quality indicator for general hospital care. 95 Globally, the WHO has focused on studying how to best implement Screening and Brief Intervention (SBI) for alcohol problems in primary care settings, 93 , 96 and how to integrate SBIRT into the health care systems of other countries, with notable success in South Africa, Brazil, and the European Union. 93 , 96

However, despite this investment in resources, well-recognized barriers to implementing these policies include physicians’ time constraints, lack of physicians’ interest and training, alignment with other treatment priorities, perceived lack of effectiveness of brief interventions, challenges with referral to treatment, and concerns about the accuracy of self-reported alcohol use. 96 - 99 A study of the use of SBIRT in primary care settings for adolescents additionally identified challenges related to parental involvement as a barrier to SBIRT implementation, although providers thought that increased reimbursement and dedicated resources would help improve screening rates. 98 In this vein, studies have also identified practices to help overcome challenges associated with implementing SBIRT, which include: having a start-up phase focused on comprehensive education and training, developing intra- and inter-organizational communication and collaboration, opinion leader support, practitioner and host site buy-in, and developing relationships with referral partners. 99 - 101

Evidence is lacking on the efficacy of SBIRT implementation in psychiatric emergency settings or in psychiatric outpatient settings that are not oriented to addressing substance abuse problems. One exception was an effort to implement computerized screening for alcohol and drug use among adults seeking outpatient psychiatric services within a large managed care system, which identified heavy drinking among 33% of patients who participated. 102 Given the high levels of heavy drinking and AUD among individuals with psychiatric disorders, 3 , 17 , 21 - 23 this area warrants further research.

Evidence-based behavioral interventions for heavy drinking and AUD

Because AUD arises from a complex interaction of neurobiological, genetic, and environmental factors, no single treatment works for everyone. Consensus exists that there are several evidence-based behavioral interventions that can be used to treat heavy drinking and AUD ( Table 1 ). Initially, we focus on treatments that have the greatest research support for their efficacy: motivational interviewing (MI), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and contingency management (CM).

Effectiveness of behavioral interventions for treating heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder

MI is a directive, client-centered counseling style used to elicit behavior change by helping clients explore and resolve ambivalence. 103 MI targets theorized mechanisms of effectiveness, 104 - 108 including self-efficacy 109 - 118 and commitment to change. 104 , 106 MI has an extensive evidence base 42 , 48 - 56 , 104 , 119 that consistently supports its use as an effective behavior intervention to help patients reduce risky/heavy drinking. 120 MI has been shown to help patients reduce risky/heavy drinking outside of the United States, including in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Europe and Brazil. 121 While MI has been studied most extensively in alcohol misuse, it is also utilized to treat dependence on other substances. 120 Advantages of MI are that it has been manualized and has a fidelity rating system. 122 Its limitations include requiring training, 123 supervision, 124 , 125 and a certain skill level. 126 Although MI is widely disseminated, 123 , 125 , 127 it is more complicated to administer than commonly assumed, 123 , 128 and its mechanism of effect is not always clear. 129

CBT focuses on challenging and changing unhelpful cognitive distortions and behaviors, improving emotional regulation, and developing personal coping strategies that target current problems. 46 , 130 - 132 CBT is viewed by many as the preferred treatment for psychiatric disorders, 133 and there is also evidence of its effectiveness to treat AUD, including in studies conducted outside of the United States. 131 , 132

CM involves the systematic reinforcement of desired behaviors (using vouchers, privileges, prizes, money, etc.) and the withholding of reinforcement or punishment of undesired behaviors. 134 Evidence supports the effectiveness of CM to improve medication adherence for AUD. 134 There is less evidence available for the effectiveness of CM to treat AUD in its own right. 135 A central challenge in implementing CM is the lack of biomarkers to detect alcohol use beyond the previous 12 hours. 136

In addition to MI, CBT, and CM, other behavioral interventions used to treat heavy drinking and AUD include 12-step facilitation, mindfulness-based interventions, couples-based therapy, and continuing care. In a multisite clinical trial, patients assigned to 12-step facilitation were as likely as those assigned to CBT, and slightly more likely than those assigned to motivational enhancement therapy, to achieve abstinence or moderate drinking without alcohol-related consequences. 137 - 139 In a systematic review of 11 mindfulness-based intervention studies, ten studies showed that mindfulness for AUD was effective compared to no treatment or a non-effective control, with some evidence to suggest it is comparable to other effective treatments. 140 A meta-analysis of couples therapy interventions for married or cohabiting individuals who sought help for AUD showed lower drinking frequency, fewer alcohol-related consequences, and better relationship satisfaction than those in individual treatment. 141 , 142 In a review of studies in which spouses and/or other family members of an alcoholic adult were involved in treatment efforts, marital and family therapy was found to be effective in helping the family cope better, and in motivating alcoholics to enter treatment when they are unwilling to seek help. 143 A systematic review that screened 15,235 studies of continuing care for AUD found only a few (n=6) high quality studies available, and concluded that adding an active intervention to usual continuing care seems to improve AUD treatment outcomes. 144

MI, CBT, and CM are the most commonly evaluated behavioral interventions used to treat individuals with co-occurring alcohol use and mood disorders. 145 While still not widely used, interventions based on these frameworks have shown initial promise in treating alcohol use among individuals with psychiatric comorbidity. 146 - 150 There is also some evidence that mindfulness-based interventions are useful for individuals with AUD and comorbid mental health conditions. 140 In contrast, a recent review found little evidence to support the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption among people who use illicit drugs. 151

Medication assisted treatment (MAT) for heavy drinking and AUD

In this section, we discuss medications that are approved by one or more regulatory agencies (e.g., European Medicines Agency, U.S. Food and Drug Administration) for treating AUD. We also discuss medications for which there is empirical evidence of efficacy from placebo-controlled trials despite lack of regulatory approval. The latter group of medications may be used “off-label” to treat heavy drinking or AUD, and some are recommended as second-line medications in clinical guidelines published by healthcare entities (e.g., U.S. Veterans Administration and Department of Defense) or professional groups (e.g., American Psychiatric Association).

Withdrawal.

Alcohol withdrawal occurs on a spectrum of severity ranging from simple withdrawal, with signs and symptoms that include insomnia and tremulousness, to severe manifestations including seizures, hallucinations, and delirium tremens. 152 Most patients undergoing alcohol withdrawal can be treated safely and effectively on an outpatient basis. 153 , 154 Individuals with acute medical or psychiatric illness may require inpatient care to avoid complications of those co-occurring disorders. Benzodiazepines, which target gamma aminobutyric acid receptors to curb excitability in the brain, have the largest and the best evidence base in treating the signs and symptoms of acute alcohol withdrawal. 155 Evidence indicates that anticonvulsants also have good efficacy, either on their own or in combination with sedatives/hypnotics. 156 Treatment of alcohol withdrawal should be followed by treatment for AUD to prevent relapse to heavy drinking. 152

A number of medications are available to treat AUD ( Table 2 ). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three medications for treating AUD: disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate. 157 These medicines are also approved in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe. Another medication, nalmefene, is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for treating AUD. 158 U.S. guidelines recommend that MAT, often in combination with a behavioral intervention, be offered to patients with a clinical indication (e.g., a positive screening test or relevant physical symptoms) of AUD. 34 , 62 We describe and review the evidence of efficacy and acceptability for each of these medications, and discuss medications that may be used off-label to treat AUD.

Effectiveness of medications for treating alcohol use disorder 20 , 179

Disulfiram.

When combined with alcohol, disulfiram increases the concentration of acetaldehyde, a toxic intermediary metabolite of alcohol. Excess amounts of acetaldehyde have unpleasant effects such as nausea, headache, and sweating. The anticipation of these unpleasant effects, rather than actually experiencing them, is considered the mechanism through which disulfiram potentially promotes patients’ avoidance of drinking. From 1949 until 1994, disulfiram was the only medication available in the United States for treating patients with alcohol dependence.

Although several clinical studies have assessed the efficacy of disulfiram in treating AUD, 159 , 160 most have not used a rigorous clinical trial methodology, 161 and a systematic review published in 1999 concluded that that the evidence for the efficacy of disulfiram was inconsistent. 162 A more recent meta-analysis of 22 randomized clinical trials using various outcome measures (e.g., continuous abstinence, number of days drinking, time to first relapse) showed a higher success rate for disulfiram than for controls, though the drug was effective only when its ingestion was supervised, and not when providers were blinded to the patients’ treatment condition. 163 Despite the potential clinical utility of disulfiram, it is not considered a primary medication for relapse prevention among patients with alcohol dependence 164 due to its adverse effects, poor adherence rate, and ethical objections to disulfiram among some clinicians. 165

Naltrexone.

Naltrexone blocks opioid receptors, stimulation of which can be involved in the pleasant sensations associated with drinking, and can reduce alcohol craving. Naltrexone was approved by the FDA as an oral medication in 1994 following the results of two randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) which showed that patients treated with naltrexone had better drinking outcomes (i.e., a greater likelihood of abstinence and reduced risk of relapse) than those treated with placebo. 166 , 167 A recent meta-analysis of 53 studies found that naltrexone was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of relapse to any drinking and heavy drinking, although the effect sizes were small (5% and 9% decreased risk, respectively). 62

Despite being one of only three FDA-approved medications for treating heavy drinking and AUD, naltrexone is infrequently prescribed. 168 Various addiction providers (e.g., physicians, managers, pharmacists) have been surveyed and have identified patient non-compliance, affordability, perceived low patient demand, and concerns about efficacy as barriers to prescribing MAT for treating AUD. 169 - 171

In 2006, naltrexone was approved by the FDA for use as a long-acting injectable formulation based on a multisite RCT that compared 190-mg and 380-mg dosages with placebo in 624 actively drinking alcohol dependent adults. 172 Results of this trial indicated a 25% greater reduction in the rate of heavy drinking days (HDD) among individuals who received the 380-mg extended-release naltrexone formulation compared to those on placebo. A multicenter, placebo-controlled RCT of a second naltrexone depot formulation in patients with alcohol dependence showed the active treatment resulted in a longer time to first drinking day, and a higher frequency of abstinent days and complete abstinence during treatment than placebo. 173 Injectable naltrexone has also been found to reduce alcohol consumption in a number of real world settings, including clinical settings among HIV-positive patients with heavy drinking, 174 HIV-positive released prisoners transitioning to the community, 175 and in the criminal justice system among adults with alcohol and opioid problems. 176 Because naltrexone has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the risk of heavy drinking, it is recommended as a first-line treatment for AUD. 20 Although theoretically the long-acting injectable formulation is associated with greater adherence than oral naltrexone, there are no large comparative studies that have evaluated the relative merits of the two formulations.

Acamprosate.

Acamprosate was approved by the FDA in 2004, based on efficacy studies conducted in Europe. Although the medication is assumed to correct an imbalance between GABA and glutamate, thus easing the negative effects of quitting drinking, a more precise understanding of its mechanism of action is lacking. 177 A recent meta-analysis of 27 studies found that although acamprosate had no effect on relapse to heavy drinking, it produced a 9% reduction in the risk of relapse to any drinking. 62

Another opioid receptor antagonist, nalmefene, is approved for treating AUD in Europe but not the United States. 158 A recent meta-analysis of five RCTs among 2,567 participants found that participants taking nalmefene had fewer HDD during treatment and lower total alcohol consumption than those taking placebo. 178 However, there was considerable dropout in the nalmefene groups, often due to adverse effects, which may limit its utility in treating AUD.

Additional medications.

Several other medications are now being evaluated in the United States for treating heavy drinking and AUD, including varenicline, gabapentin, topiramate, zonisamide, baclofen, ondansetron, levetiracetam, quetiapine, aripiprazole, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. 179 Although none of these are FDA-approved for treating AUD, they are sometimes used off-label for that purpose. Evidence has been mixed on the efficacy of these medications, their side effects, and acceptability. 180 Baclofen and topiramate currently have the most support for efficacy. 181 , 182

Treating co-occurring AUD and psychiatric disorders.

Efforts to treat AUD and co-occurring disorders such as major depression, bipolar disorder, and social anxiety disorder with MAT have evolved over time. Early efforts that used medications such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and lithium based on their efficacy in treating the primary psychiatric disorder had mixed success. 183 Such efforts were based on the hypothesis that a reduction in psychiatric symptoms would reduce drinking by reducing the motivation for self-medication with alcohol. In a meta-analysis of RCTs of antidepressants in patients with co-occurring major depression and a substance use disorder (including alcohol dependence), 184 the majority of studies showed a significant or near-significant advantage for the active medication over placebo, with small-to-medium effect sizes. Although studies that showed a medium effect size for treating depression also yielded a medium effect size in reducing substance use, studies that showed smaller effects on depression did not yield beneficial effects on substance use behavior, leading to the conclusion that it is necessary to treat both disorders. A good example of the recommended approach is a study of depressed patients with AUD who were treated with sertraline, naltrexone, sertraline plus naltrexone, or double placebo for 14 weeks; the combined treatment group had a significantly higher abstinence rate and longer time to relapse to heavy drinking than the other three groups, which did not differ from one another. 185 With respect to the effects on depression, at the end of treatment, the percentage of non-depressed patients in the sertraline plus naltrexone group (83·3%) versus the other treatment arms combined (58·3%) approached significance after correction for multiple comparisons. The pharmacotherapy of AUD and co-occurring psychiatric disorders remains an understudied, but clinically important area of research.

Utilization of medications.

Despite the availability of medications with demonstrated efficacy for treating AUD, they are widely underutilized. MAT is prescribed to less than 9% of patients who are likely to benefit from them. 20 A variety of obstacles to greater adoption of substance dependence medications have been identified, 169 , 186 , 187 and include both structural and philosophical barriers among substance abuse specialty providers. 188 Among a national sample of 372 organizations that deliver AUD treatment services in the United States, organizations that offered services related to health problems other than AUD (e.g., primary medical care, medications for smoking cessation, and services to address co-occurring psychiatric conditions) were more likely to offer pharmacotherapy for treating AUD. 189 Regarding the uptake of MAT, a study among a U.S. cohort of 190 publicly-funded treatment organizations that offered no substance use disorder (SUD) medications at baseline showed that 23% offered SUD medications after five years of follow-up. 190 This was more likely to occur in programs that had greater medical resources, Medicaid funding, and contact with pharmaceutical companies. 190

Further research.

Research to identify and develop medications with greater efficacy that can gain widespread clinical acceptance in treating heavy drinking and AUD remains a high priority. 20 However, several methodological barriers impede this effort and the ability to marshal stronger evidence of efficacy for approved medications. For example, MAT efficacy trials for AUD have been small, especially when compared to trials of treatments for other major public health problems such as cardiovascular disease. 89 Other methodological challenges faced by trials to treat AUD involve recruitment and retention, inclusion/exclusion criteria, measurement of medication adherence/intervention fidelity, timing of assessments, statistical analyses, and the outcome measures used. 191 , 192

Outcome measures of treatment efficacy and AUD treatment goals: Non-abstinent drinking reductions

Evaluating the efficacy of treatments for AUD should be placed in the context of evaluating the efficacy of medicines for other chronic conditions (e.g., depression, diabetes) in which a “perfect” outcome is not required for treatment to be considered successful. Historically, the favored outcome for clinical trials of MAT for AUD or alcohol dependence has been abstinence. 193 However, many participants of MAT clinical trials reduce their drinking substantially without achieving complete abstinence. 194 - 196 In this sense, abstinence is a very high-threshold outcome that may be insensitive to clinical benefit. Considering abstinence as the only successful treatment outcome is also problematic because many individuals with AUD are not interested in a goal of total abstinence, 197 - 199 and the assumption that clinicians will expect a goal of abstinence may deter them from seeking treatment at all. Recognizing this, the FDA now accepts an additional outcome for MAT clinical trials: no heavy drinking days (no-HDD; defined as no days in which more than four drinks are consumed by men and more than three drinks are consumed by women), 200 with the proportion of participants having no-HDD compared between treatment arms. However, the no-HDD outcome itself is also narrow and may be insensitive because it classifies patients as treatment failures after any HDD, even though some of these patients substantially reduce their drinking. 194 - 196 Evidence that non-abstinent reductions also provide clinical benefit has been emerging recently, with investigation into the best way to quantify clinically meaningful drinking reductions.

One measure of drinking reduction that has shown promise is the WHO four-level classification of drinking risk (very-high-risk, high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk). The EMA currently accepts a two-level reduction in WHO drinking risk levels as a valid clinical trial outcome. 201 , 202 The validity of a reduction in WHO drinking risk levels as a clinical trials outcome has been under investigation since 2012 by the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE) Group, 191 , 203 with greatest interest in drinkers who are initially at the highest levels (very-high-risk and high-risk drinkers), and thus are most relevant to clinical trials for AUD. 204 For the FDA to accept reductions in WHO drinking risk levels as a valid clinical trial outcome, information is needed about the clinical benefit provided by reductions in WHO drinking risk levels, i.e., whether such reductions predict improvements in how individuals feel and function.

Thus far, several clinical studies have demonstrated clinical benefit from reductions in WHO drinking risk levels. As a best example, in a pooled analysis of data from three multisite placebo-controlled RCTs of MAT (naltrexone, varenicline, and topiramate) in adults with DSM-IV alcohol dependence, more respondents met criteria for WHO drinking risk level reductions than total abstinence or no-HDD, yet standardized treatment effects observed for the WHO drinking risk level reductions were comparable to those obtained using either abstinence or no-HDD outcomes. 205 Another study 204 used data from the COMBINE study, 206 a multisite treatment trial for alcohol dependence (n=1,383), to show that reductions in WHO drinking risk levels predicted reduced alcohol consequences on the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrinC) 207 and improved mental health functioning on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12). 204 , 208 COMBINE study data has also been used to show that reductions in WHO drinking risk levels predict reductions in alcohol-related consequences and systolic blood pressure, and improved mental health functioning, liver enzyme levels, and quality of life. 209 In epidemiologic studies of U.S. drinkers (n=22,005) followed prospectively for three years, reductions from the very-high-risk and high-risk levels predicted decreased rates of overall and chronic alcohol dependence, improved SF-12 mental health functioning, 10 and reduced odds of liver disease, 210 psychiatric comorbidity, 211 and DUDs 212 ( Table 3 ). While more information on the relationship between these reductions and improvements in how individuals feel or function would further strengthen the case for using WHO drinking risk level reduction as a clinical trial outcome, 213 overall, the evidence thus far supports reductions from the highest levels of the four-level WHO drinking risk categories as valid outcomes.

Health outcomes associated with drinking reductions as defined by the WHO drinking risk levels (drinks per day) and change in WHO risk level between Wave 1 (2001-2002) and Wave 2 (2004-2005) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) 10 , 210 - 212

▼= decreased risk; ▲ = increased risk; ▼/▲= p≤0·05; ▼ / ▲ = p>0·05; R = reference group; --- = contrast could not be computed because the prevalence of condition at Wave 2 was 0·0%

Note: AUDIT-C results are not included because there were very high proportions of participants at the WHO very-high-risk and high-risk drinking levels with Wave 1 positive AUDIT-C scores; therefore, adjusted odds of positive Wave 2 AUDIT-C scores by change in WHO drinking risk level could not be produced because the regression models used to produce them did not converge.

Adopting valid non-abstinent drinking reduction measures may benefit research (and ultimately, treatment) if such drinking reductions are more sensitive indicators of treatment efficacy (including both behavioral and medication-assisted treatment) than the outcome measures now commonly used. Furthermore, demonstrating that clinical benefit is associated with non-abstinent drinking reductions (including sustained improvements in how individuals feel and function) could serve an additional important purpose by broadening interest in treatment. 157 Offering drinking reduction goals to patients who are not interested in an initial abstinence goal could encourage more of these individuals to enter treatment. 197 Some patients may benefit from reducing their drinking without a need to become abstinent, while other patients, after engaging in treatment, may decide that abstinence is a better goal for them. In summary, non-abstinent drinking reductions could extend the repertoire of tools available to clinicians to treat heavy drinking and AUD by strengthening clinical trial design and broadening interest in treatment.

The use of technology to prevent and treat heavy drinking and AUD

Ehealth and mhealth..

The use of digital technology to prevent and treat heavy drinking and AUD is often called eHealth (electronic-Health) or mHealth (mobile-Health). Even in situations where clinical care is provided onsite, 214 , 215 eHealth and mHealth interventions are emerging as ways to help meet the need for patient self-management and continuing care. 216

Evidence base for eHealth and mHealth interventions.

There is a growing evidence base for the effectiveness of eHealth and mHealth interventions. A recent meta-analysis of 57 studies of digital interventions for alcohol consumption in community-dwelling populations found moderate-quality evidence that digital interventions decrease alcohol consumption. 217 In addition, a meta-analysis of 26 brief web-based or computer-based interventions targeting young adults demonstrated a significant reduction in the mean number of drinks consumed weekly compared to control conditions. 218 eHealth and mHealth interventions have also been developed to address alcohol-related problems. However, a recent systematic review concluded that digital interventions were not consistently effective in people with AUD, and the heterogeneity of interventions, particularly in terms of their complexity, made reaching a consensus about their overall effectiveness challenging. 219 The review also noted that many interventions did not report on outcomes other than changes in drinking levels, such as psychological health or social functioning. 219 The complexity of AUD, which is characterized not only by compulsive alcohol use, but also by loss of control over alcohol intake and a negative emotional state when not using, may increase the challenge of addressing it through a digital platform.

The importance of mHealth is greater in low- and middle-income countries where people lack access to medical care but, oftentimes have a mobile phone. 220 A recent review identified six studies of mHealth interventions that targeted alcohol consumption in low- and middle-income countries (Brazil, Thailand, and Uruguay), all of which demonstrated efficacy in reducing drinking. 220

Examples of eHealth and mHealth interventions.

Several mHealth interventions delivered via smartphone have demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy in reducing alcohol consumption among individuals with AUD. 214 The Addiction-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS) promotes AUD recovery through high-risk GPS location tracking, educational resources, social support, a “panic button” (which triggers automated reminders about personal motivations for not drinking, provides alerts to people who could reach out to the user, and offers tools for dealing with urges), regular assessments, and relaxation tools. 221 - 223 A-CHESS users reported significantly fewer risky drinking days than participants in a control condition. 224 Another mHealth intervention, the Location-Based Monitoring and Intervention for Alcohol Use Disorders (LBMI-A), promotes AUD recovery through psychoeducational modules and other features, including high-risk location tracking, regular assessments, social support (users can share their assessment feedback with self-identified supportive others), and motivational tools. 225 , 226 LBMI-A users demonstrated significant decreases in self-reported HDD and drinks per week, and a significant increase in the proportion of days abstinent compared to participants assigned to an online, brief motivational intervention plus bibliotherapy. 226

Other mHealth interventions have been developed to address high-risk drinking in specialized populations. For example, HealthCall 227 , 228 targets drinking reductions among HIV-positive patients with heavy drinking by extending patient engagement beyond an initial brief MI-based intervention with little additional staff time or effort. 229 HealthCall participants had significantly greater reduction in multiple measures of alcohol consumption than a control condition. 227 , 229

Effective eHealth and mHealth interventions have also been developed to address alcohol consumption in patients with co-occurring alcohol and mental health problems. For example, the DEpression-ALcohol (DEAL) Project, a web-based self-help intervention, was associated with statistically significant reductions in quantity and frequency of alcohol use at three months post-intervention in young adults (ages 18–25 years) compared to participants assigned to a web-based attention-control condition. 230 A-CHESS was also translated and adapted for Spanish-speaking individuals with co-occurring alcohol and mental health disorders, and was found to have good acceptability; 231 results of its efficacy have not yet been published.

Future research.

eHealth and mHealth interventions could potentially become more effective if they are adjusted to the individual needs of users, which are often influenced by psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and personality disorders. Little work of this type has been done thus far, but could contribute to reducing the burden of co-occurring AUD and psychiatric disorders, especially if the interventions could be disseminated in real-world clinical settings. 219 Achieving this will likely require a better understanding of how people incorporate technology in their everyday lives, as well as research into effective ways to disseminate interventions that are efficacious in clinical trials. Future research is also needed to examine how mHealth interventions can be better adapted to match the user’s level of alcohol consumption, 232 and to investigate the impact of moderators such as sex, age, race, and comorbid psychiatric disorders on the efficacy of technology-based drinking reduction interventions.

Population-level interventions to prevent and treat heavy drinking and AUD

Beyond the individual-level methods of preventing and treating heavy drinking and AUD discussed thus far, population-level approaches to alcohol prevention are also important. 29 A large base of evidence is available to inform the development and modification of alcohol-related harm prevention policies ( Table 4 ). 30 , 31

Effectiveness of alcohol-related harm prevention policies 30 , 31

Evidence base for effective population-level interventions.

According to multiple reviews, there is clear and consistent evidence that regulating the availability of alcohol is efficacious and cost-effective in reducing overall alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. 233 , 234 Limiting alcohol availability is achieved by increasing the price of alcohol, mainly through taxation, which deters consumption because of the increased cost. Other forms of regulation include a minimum purchase age, restricting the days and hours of sale, and regulating the venues where alcohol can be sold. Addressing the marketing of alcohol has the potential to be efficacious and cost-effective in reducing overall alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm as well. This can be achieved by instating content guidelines and limiting the volume of advertising by alcohol companies, particularly advertising that targets youth. However, evidence suggests that self-regulation of alcohol marketing within the beverage industry is not effective in enforcing these rules. 30 , 31 Other reviews note there is also strong evidence that alcohol-related policies regarding drunk driving implemented through legislation and its enforcement are effective, i.e., lowering the legally allowable blood alcohol concentration level, establishing sobriety checkpoints, and mandating treatment for alcohol-impaired driving offenses. 30 , 31

Many campaigns that provide information and education to the general public increase awareness of alcohol-related harm, but lack evidence for their ability to produce long-lasting changes in behavior. 31 However, these campaigns may help raise awareness and acceptance of efforts to address alcohol consumption through other, more effective policy-level actions. 30 A long-standing, multi-pronged campaign to increase women’s awareness of the risks of drinking during pregnancy 235 may be an important exception to the overall lack of evidence for long-term change from public education, as evidenced by significant increases in the rate of binge drinking between 2002 and 2014 in non-pregnant U.S. women of reproductive age, but not among pregnant women. 236 Reviews note the evidence is weaker for the effectiveness of other population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm, including those that work at the family- and community-level, those based in schools, workplaces, or alcohol serving settings, and those that target illicit alcohol sales. 29

Because most countries do not have adequate policies in place to minimize alcohol-related harm, 237 there is a great need to implement efficacious, cost-effective policies. Efforts to scale up such policies are complicated by the ever-present tension between the beverage industry, whose goal is to increase alcohol consumption, and public health concerns, whose goal is to reduce harmful consumption. Some alcohol industry strategies may seek to undermine effective health policies and programs, increasing the challenges to their implementation and efficacy. 238 , 239 An area meriting exploration is how the alcohol policy environment impacts the efficacy of individual-level methods in preventing and treating heavy drinking and AUD, including among individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders. More complete knowledge of how individual-level and socio-ecological-level factors interact in the prevention and treatment of AUD would facilitate better targeting of prevention efforts, a particularly important concern given the limited resources available to minimize alcohol-related morbidity and mortality.

Concluding remarks and future directions

This review provides a critical discussion of widely used approaches for the prevention, identification, and treatment of heavy drinking and AUD, including recent interventions that have sought to harness the power of technology. The use of different measures of alcohol consumption (e.g., heavy drinking, binge drinking) and alcohol-related disorders (e.g., harmful drinking, alcohol dependence, AUD) throughout the literature poses challenges to generalizability across studies. Although practitioners not specializing in alcohol treatment are often unaware of the guidelines for preventing, identifying, and treating heavy drinking and AUD, consensus on certain guidelines does exist, and valuable tools are available. 34 Efforts are underway to continue developments in this area, with a focus on preventing, identifying, and treating heavy drinking and AUD among individuals who also suffer from psychiatric and drug use disorders.

One promising area of future research aims to identify individual-level factors that predict treatment response. These include phenotypic predictors such as types of drinker (e.g., reward vs. relief), 240 and genetic predictors such as variation in genes that encode neurotransmitter receptors. 241 , 242 Project MATCH found a number of patient characteristics that predicted response to psychotherapies at follow-up (e.g., psychiatric severity), 137 but not during the treatment period. 138 These approaches, now subsumed under the heading of precision medicine, are an important direction for future research.

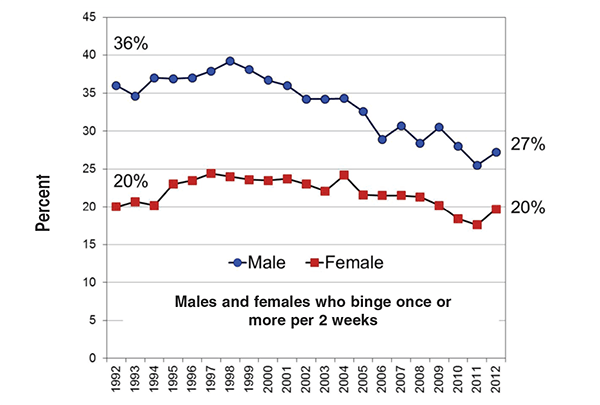

Given that alcohol use and binge drinking have increased more in adult women than men over the past several years, 2 , 243 more research is needed on prevention and treatment efforts that address the specific needs of adult women. Also, treatment providers continue to seek more information on heavy drinking and AUD among individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders, including drug use disorders. Although researchers can be reluctant to undertake these more complicated studies, and grant review committees may be critical of the study designs due to the increased heterogeneity of samples characterized by comorbidity, this remains an important area that requires further research. Other key issues for future research include: 1) the short- and long-term efficacy of school-based alcohol prevention interventions; 2) targeted prevention efforts focused on identifying youth at increased risk for developing heavy drinking or AUD; 3) improving the efficacy and implementation of SBIRT in clinical settings; 4) assessing the effectiveness of SBIRT in settings where it is currently implemented; 5) implementing SBIRT or similar procedures in mental health settings; 6) improving the uptake of MAT for patients who are eligible and interested in receiving it; 7) developing additional medication options; 8) evaluating the benefits of non-abstinent drinking reductions for clinical trial outcomes; 9) precision medicine; 10) scaling up technology-based interventions beyond the confines of efficacy trials; and 11) examining how the alcohol policy environment impacts individual-level methods of preventing and treating heavy drinking and AUD, including among patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Given the high prevalence of harmful alcohol use and its adverse health consequences, developing a fuller understanding of these issues is a public health priority.

Acknowledgments

Research funding is acknowledged from NIAAA (R01AA025309, PI: Hasin; R01AA023192, PI: Kranzler; R01AA021164, PI: Kranzler); New York State Psychiatric Institute; the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE); the Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center of the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; and NIDA (T32DA031099, for Knox; PI: Hasin). The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interests

DSH and HRK are members of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE), which in the past three years was sponsored by AbbVie, Alkermes, Amygdala Neurosciences, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Ethypharm, Indivior, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Pfizer. HRK is named as an inventor on PCT patent application #15/878,640 entitled "Genotype-guided dosing of opioid agonists," filed January 24, 2018. DSH acknowledges support from Campbell Alliance for an unrelated project on the measurement of opioid addiction. JK and FRRL declare no conflicts of interest.

- 1. GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018; 392(10152): 1015–35. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(9): 911–23. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72(8): 757–66. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Parker AJ, Marshall EJ, Ball DM. Diagnosis and management of alcohol use disorders. BMJ 2008; 336(7642): 496–501. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Saunders JB. Substance use and addictive disorders in DSM-5 and ICD 10 and the draft ICD 11. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017; 30(4): 227–37. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Saunders JB, Peacock A, Degenhardt L. Alcohol use disorders in the draft ICD-11, and how they compare with DSM-5. Current Addiction Reports 2018; 5: 257–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Degenhardt L, Bharat C, Bruno R, et al. Concordance between the diagnostic guidelines for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in the draft ICD-11 and other classification systems: Analysis of data from the WHO’s World Mental Health Surveys. Addiction 2019; 114(3): 534–52. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction 1993; 88(6): 791–804. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol 1995; 56(4): 423–32. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Hasin DS, Wall M, Witkiewitz K, et al. Change in non-abstinent WHO drinking risk levels and alcohol dependence: A 3 year follow-up study in the US general population. Lancet Psychiatry 2017; 4(6): 469–76. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheets: Alcohol use and your health. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm (accessed Jan 8, 2018).

- 12. Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet 2005; 365(9458): 519–30. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Rehm J, Gmel G, Sempos CT, Trevisan M. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Res Health 2003; 27(1): 39–51. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Rehm J Alcohol and all-cause mortality. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25(1): 215–6; author reply 8–20. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Lewis-Laietmark C, Wettlaufer A, Shield KD, et al. The effects of alcohol-related harms to others on self-perceived mental well-being in a Canadian sample. Int J Public Health 2017; 62(6): 669–78. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Greenfield TK, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Kaplan LM, Kerr WC, Wilsnack SC. Trends in alcohol’s harms to others (AHTO) and co-occurrence of family-related AHTO: The four US national alcohol surveys, 2000–2015. Subst Abuse 2015; 9(Suppl 2): 23–31. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64(7): 830–42. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007; 86(2–3): 214–21. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Shield KD, Rehm J, Rehm MX, Gmel G, Drummond C. The potential impact of increased treatment rates for alcohol dependence in the United Kingdom in 2004. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 53. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: A review. JAMA 2018; 320(8): 815–24. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61(8): 807–16. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62(10): 1097–106. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018; 75(4): 336–46. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(1): 39–47. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Witkiewitz K, Villarroel NA. Dynamic association between negative affect and alcohol lapses following alcohol treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77(4): 633–44. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Newes-Adeyi G, Chen CM, Williams GD, Faden VB. Trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2003. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380(9859): 2224–60. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Stigler MH, Neusel E, Perry CL. School-based programs to prevent and reduce alcohol use among youth. Alcohol Res Health 2011; 34(2): 157–62. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Martineau F, Tyner E, Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Lock K. Population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm: An overview of systematic reviews. Prev Med 2013; 57(4): 278–96. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 2009; 373(9682): 2234–46. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Burton R, Henn C, Lavoie D, et al. A rapid evidence review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: An English perspective. Lancet 2017; 389(10078): 1558–80. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: The SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(10): 1480–8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Willenbring ML, Massey SH, Gardner MB. Helping patients who drink too much: An evidence-based guide for primary care clinicians. Am Fam Physician 2009; 80(1): 44–50. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Babor TF, Del Boca F, Bray JW. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment: Implications of SAMHSA’s SBIRT initiative for substance abuse policy and practice. Addiction 2017; 112 Suppl 2: 110–7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus 2007; 28(3): 7–30. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Bray JW, Del Boca FK, McRee BG, Hayashi SW, Babor TF. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Rationale, program overview and cross-site evaluation. Addiction 2017; 112 Suppl 2: 3–11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018; 320(18): 1899–909. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Moyer VA, Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159(3): 210–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Saitz R Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: Absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010; 29(6): 631–40. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Whitlock EP, Green CA, Polen MR, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2004. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140(7): 557–68. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Chi FW, Weisner CM, Mertens JR, Ross TB, Sterling SA. Alcohol brief intervention in primary care: Blood pressure outcomes in hypertensive patients. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 77: 45–51. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2). [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(9): 986–95. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Ray LA, Bujarski S, Grodin E, et al. State-of-the-art behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2019; 45(2): 124–40. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Pringle JL, Kowalchuk A, Meyers JA, Seale JP. Equipping residents to address alcohol and drug abuse: The national SBIRT residency training project. J Grad Med Educ 2012; 4(1): 58–63. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005; 1: 91–111. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction 2001; 96(12): 1725–42. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71(5): 843–61. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction 1993; 88(3): 315–35. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Burke BL, Vassilev G, Kantchelov A, Zweben A. Motivational interviewing with couples In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002: 347–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Miller WR, Brown J, Simpson TL, et al. What works? A methodological analysis of the alcohol treatment outcome in literature In: Hester RK, Miller WR, eds. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: Effective alternatives. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1995: 12–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Grossberg PM, et al. Brief physician advice for heavy drinking college students: A randomized controlled trial in college health clinics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2010; 71(1): 23–31. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol 2001; 62(6): 806–16. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Hungerford DW, Williams JM, Furbee PM, et al. Feasibility of screening and intervention for alcohol problems among young adults in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2003; 21(1): 14–22. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Beich A, Gannik D, Malterud K. Screening and brief intervention for excessive alcohol use: Qualitative interview study of the experiences of general practitioners. BMJ 2002; 325(7369): 870. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Beich A, Gannik D, Saelan H, Thorsen T. Screening and brief intervention targeting risky drinkers in Danish general practice: A pragmatic controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol 2007; 42(6): 593–603. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S. Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003; 327(7414): 536–42. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: A meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol 2006; 41(3): 328–35. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Bogenschutz MP, Donovan DM, Mandler RN, et al. Brief intervention for patients with problematic drug use presenting in emergency departments: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(11): 1736–45. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014; 311(18): 1889–900. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Wilk AI, Jensen NM, Havighurst TC. Meta-analysis of randomized control trials addressing brief interventions in heavy alcohol drinkers. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12(5): 274–83. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Chambers JE, Brooks AC, Medvin R, et al. Examining multi-session brief intervention for substance use in primary care: Research methods of a randomized controlled trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2016; 11(1): 8. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction 2002; 97(3): 279–92. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Miller WR, Baca C, Compton WM, et al. Addressing substance abuse in health care settings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006; 30(2): 292–302. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction 2015; 110(9): 1404–15. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Revisiting our review of screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Meta-analytical results still point to no efficacy in increasing the use of substance use disorder services. Addiction 2016; 111(1): 181–3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Castellón PC, Cardenas G, Feaster DJ, et al. Desire for substance use disorder treatment among HIV-infected substance users in two U.S. southern cities. Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; 2015 Nov; Chicago, IL; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Kim TW, Bernstein J, Cheng DM, et al. Receipt of addiction treatment as a consequence of a brief intervention for drug use in primary care: A randomized trial. Addiction 2017; 112(5): 818–27. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Saitz R ‘SBIRT’ is the answer? Probably not. Addiction 2015; 110(9): 1416–7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, et al. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172(12): 1364–72. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Probst C, Moyo D, Purshouse R, Rehm J. Transition probabilities for four states of alcohol use in adolescence and young adulthood: What factors matter when? Addiction 2015; 110(8): 1272–80. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. van Amsterdam J, van den Brink W. Reduced-risk drinking as a viable treatment goal in problematic alcohol use and alcohol dependence. J Psychopharmacol 2013; 27(11): 987–97. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerda M, et al. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991–1992 to 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(6): 579–88. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Martins SS, Sarvet A, Santaella-Tenorio J, Saha T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Changes in US lifetime heroin use and heroin use disorder: Prevalence from the 2001–2002 to 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(5): 445–55. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Compton WM, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160(5): 890–955. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet 2012; 379(9810): 55–70. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Kessler RC. The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry 2004; 56(10): 730–7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192(2): 98–105. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. O’Brien CP, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Priority actions to improve the care of persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders: A call to action. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56(10): 703–13. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 83. Yuodelis-Flores C, Ries RK. Addiction and suicide: A review. The American Journal on Addictions 2015; 24(2): 98–104. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 84. Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: Comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009; 99(1–3): 280–95. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 85. Saitz R Candidate performance measures for screening for, assessing, and treating unhealthy substance use in hospitals: Advocacy or evidence-based practice? Ann Intern Med 2010; 153(1): 40–3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Glass JE, Andreasson S, Bradley KA, et al. Rethinking alcohol interventions in health care: A thematic meeting of the International Network on Brief Interventions for Alcohol & Other Drugs (INEBRIA). Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017; 12(1): 14. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Saitz R Lost in translation: The perils of implementing alcohol brief intervention when there are gaps in evidence and its interpretation. Addiction 2014; 109(7): 1060–2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Hingson R, Compton WM. Screening and brief intervention and referral to treatment for drug use in primary care: Back to the drawing board. JAMA 2014; 312(5): 488–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 89. McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, et al. Vital signs: Communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use, 44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63(1): 16–22. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26(3): 299–306. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 91. United Kingdom National Screening Committee. The UK NSC recommendation on alcohol misuse screening in adults. March 2017. https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/alcohol .

- 92. Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Collins BJ, Kivlahan DR. Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care 2006; 12(10): 597–606. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 93. Agerwala SM, McCance-Katz EF. Integrating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) into clinical practice settings: A brief review. J Psychoactive Drugs 2012; 44(4): 307–17. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 94. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 95. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: A narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2013; 8: 11. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 96. Babor TE, Higgins-Biddle J, Dauser D, Higgins P, Burleson JA. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: Implementation models and predictors. J Stud Alcohol 2005; 66(3): 361–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 97. Senreich E, Ogden LP, Greenberg JP. A postgraduation follow-up of social work students trained in “SBIRT”: Rates of usage and perceptions of effectiveness. Soc Work Health Care 2017; 56(5): 412–34. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 98. Palmer A, Karakus M, Mark T. Barriers faced by physicians in screening for substance use disorders among adolescents. Psychiatr Serv 2019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 99. Rahm AK, Boggs JM, Martin C, et al. Facilitators and barriers to implementing screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in primary care in integrated health care settings. Subst Abus 2015; 36(3): 281–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 100. Vendetti J, Gmyrek A, Damon D, Singh M, McRee B, Del Boca F. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Implementation barriers, facilitators and model migration. Addiction 2017; 112 Suppl 2: 23–33. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]