The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time

For his senior thesis, Jordan Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese major, produced a nonfiction book of travel writing about the people and places along Colombia’s main river, the Magdalena.

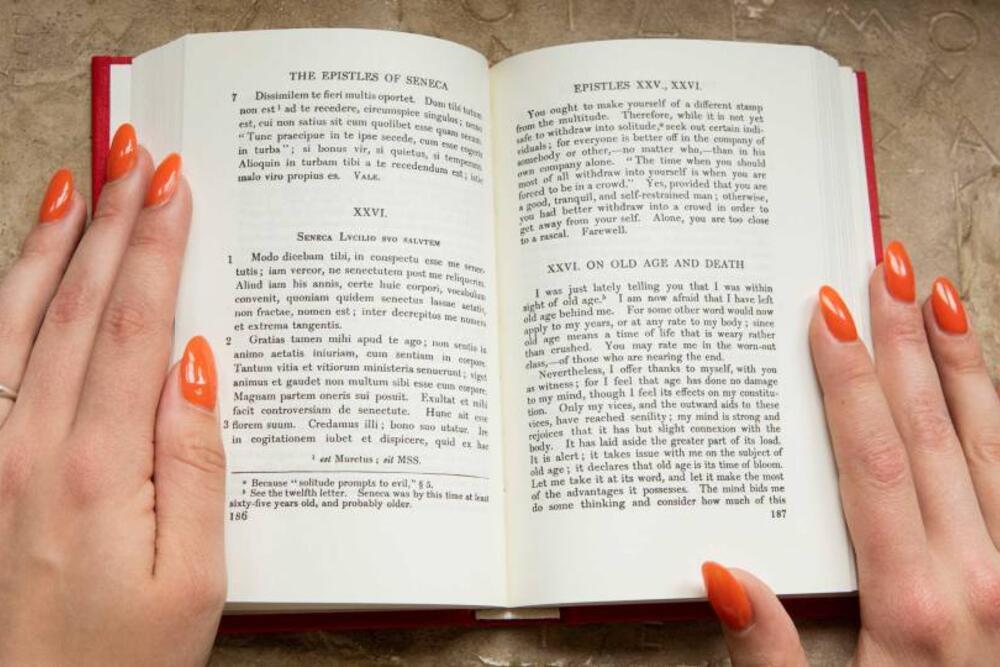

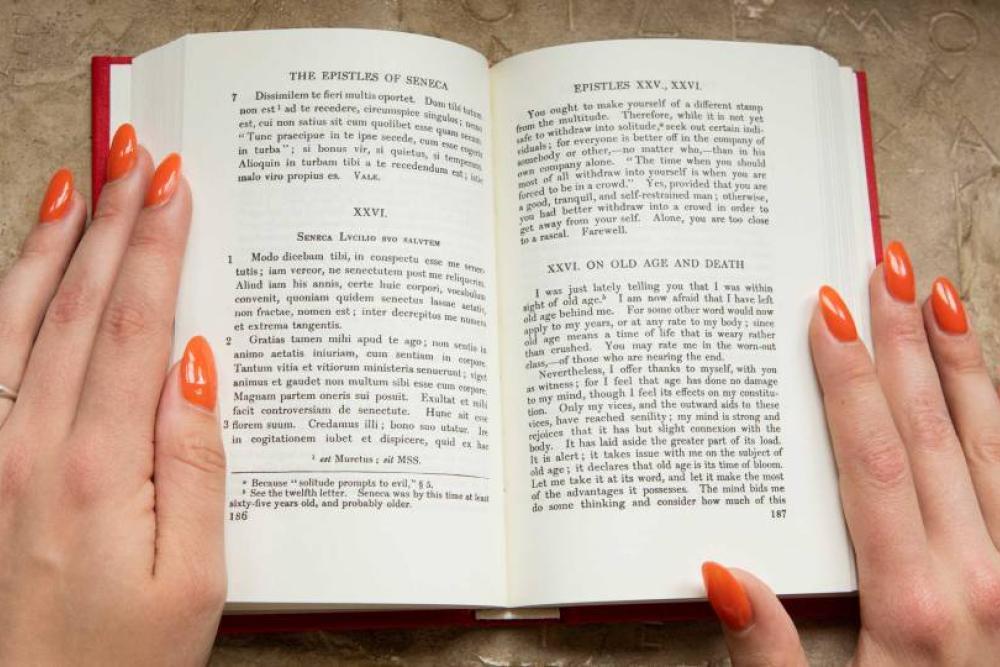

Embracing the Classics to Inform Policymaking for Public Education

For her senior thesis, Emma Treadwayconsiders how the basic tenets of Stoicism — a school of philosophy that dates from 300 BCE — can teach students to engage empathetically with the world and address inequities in the classroom.

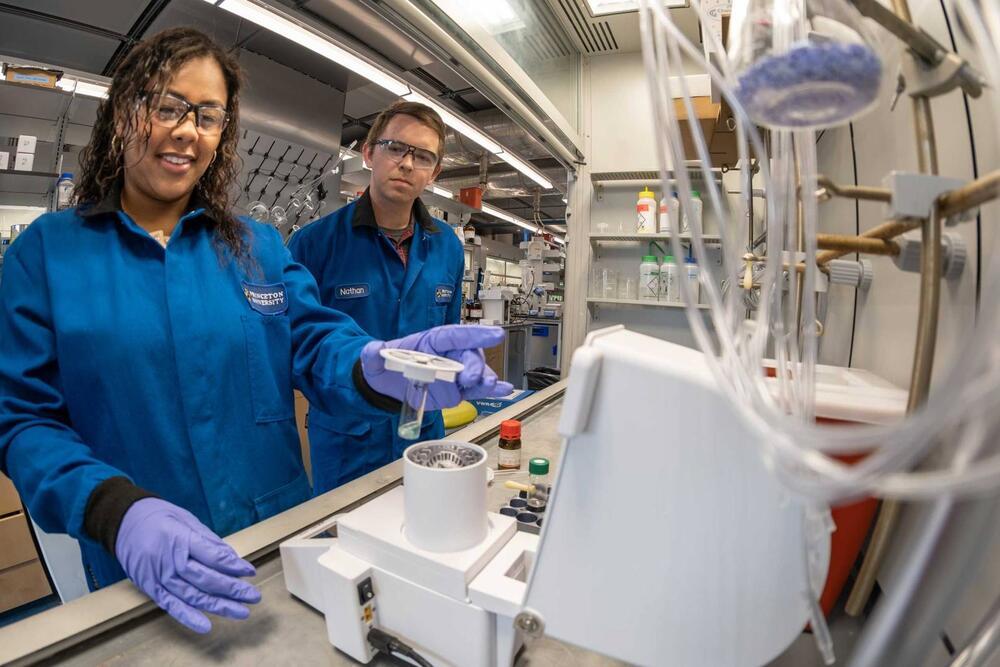

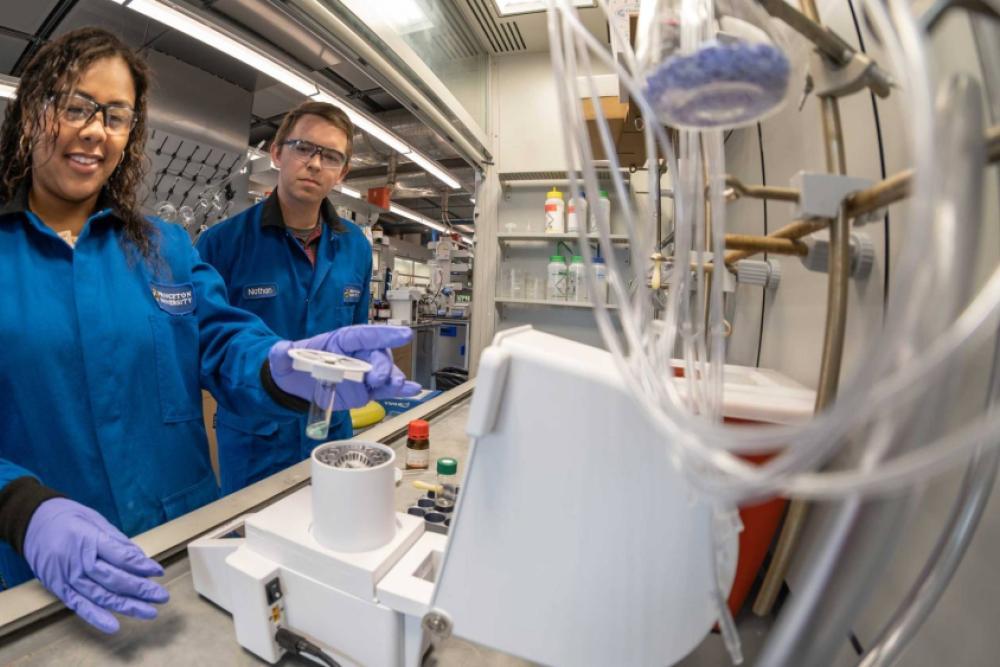

Creating A Faster, Cheaper and Greener Chemical Reaction

One way to make drugs more affordable is to make them cheaper to produce. For her senior thesis research, Cassidy Humphreys, a chemistry major with a passion for medicine, took on the challenge of taking a century-old formula at the core of many modern medications — and improving it.

The Humanity of Improvisational Dance

Esin Yunusoglu investigated how humans move together and exist in a space — both on the dance floor and in real life — for the choreography she created as her senior thesis in dance, advised by Professor of Dance Susan Marshall.

From the Blog

The infamous senior thesis, revisiting wwii: my senior thesis, independent work in its full glory, advisers, independent work and beyond.

What Is a Senior Thesis?

Daniel Ingold/Cultura/Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A senior thesis is a large, independent research project that students take on during their senior year of high school or college to fulfill their graduation requirement. It is the culminating work of their studies at a particular institution, and it represents their ability to conduct research and write effectively. For some students, a senior thesis is a requirement for graduating with honors.

Students typically work closely with an advisor and choose a question or topic to explore before carrying out an extensive research plan.

Style Manuals and the Paper's Organization

The structure of your research paper will depend, in part, on the style manual that is required by your instructor. Different disciplines, such as history, science, or education, have different rules to abide by when it comes to research paper construction, organization, and modes of citation. The styles for different types of assignment include:

Modern Language Association (MLA): The disciplines that tend to prefer the MLA style guide include literature, arts, and the humanities, such as linguistics, religion, and philosophy. To follow this style, you will use parenthetical citations to indicate your sources and a works cited page to show the list of books and articles you consulted.

American Psychological Association (APA): The APA style manual tends to be used in psychology, education, and some of the social sciences. This type of report may require the following:

- Introduction

Chicago style: "The Chicago Manual of Style" is used in most college-level history courses as well as professional publications that contain scholarly articles. Chicago style may call for endnotes or footnotes corresponding to a bibliography page at the back or the author-date style of in-text citation, which uses parenthetical citations and a references page at the end.

Turabian style: Turabian is a student version of Chicago style. It requires some of the same formatting techniques as Chicago, but it includes special rules for writing college-level papers, such as book reports. A Turabian research paper may call for endnotes or footnotes and a bibliography.

Science style: Science instructors may require students to use a format that is similar to the structure used in publishing papers in scientific journals. The elements you would include in this sort of paper include:

- List of materials and methods used

- Results of your methods and experiments

- Acknowledgments

American Medical Association (AMA): The AMA style book might be required for students in medical or premedical degree programs in college. Parts of an AMA research paper might include:

- Proper headings and lists

- Tables and figures

- In-text citations

- Reference list

Choose Your Topic Carefully

Starting off with a bad, difficult, or narrow topic likely won't lead to a positive result. Don't choose a question or statement that's so broad that it's overwhelming and could comprise a lifetime of research or a topic that's so narrow you'll struggle to compose 10 pages. Consider a topic that has a lot of recent research so you won't struggle to put your hands on current or adequate sources.

Select a topic that interests you. Putting in long hours on a subject that bores you will be arduous—and ripe for procrastination. If a professor recommends an area of interest, make sure it excites you.

Also, consider expanding a paper you've already written; you'll hit the ground running because you've already done some research and know the topic. Last, consult with your advisor before finalizing your topic. You don't want to put in a lot of hours on a subject that is rejected by your instructor.

Organize Your Time

Plan to spend half of your time researching and the other half writing. Often, students spend too much time researching and then find themselves in a crunch, madly writing in the final hours. Give yourself goals to reach along certain "signposts," such as the number of hours you want to have invested each week or by a certain date or how much you want to have completed in those same timeframes.

Organize Your Research

Compose your works cited or bibliography entries as you work on your paper. This is especially important if your style manual requires you to use access dates for any online sources that you review or requires page numbers be included in the citations. You don't want to end up at the very end of the project and not know what day you looked at a particular website or have to search through a hard-copy book looking for a quote that you included in the paper. Save PDFs of online sites, too, as you wouldn't want to need to look back at something and not be able to get online or find that the article has been removed since you read it.

Choose an Advisor You Trust

This may be your first opportunity to work with direct supervision. Choose an advisor who's familiar with the field, and ideally select someone you like and whose classes you've already taken. That way you'll have a rapport from the start.

Consult Your Instructor

Remember that your instructor is the final authority on the details and requirements of your paper. Read through all instructions, and have a conversation with your instructor at the start of the project to determine his or her preferences and requirements. Have a cheat sheet or checklist of this information; don't expect yourself to remember all year every question you asked or instruction you were given.

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- Your Personal Essay Thesis Sentence

- Revising a Paper

- How to Narrow the Research Topic for Your Paper

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- How to Develop a Research Paper Timeline

- Finding Trustworthy Sources

- World War II Research Essay Topics

- How to Use Verbs Effectively in Your Research Paper

- How to Write a 10-Page Research Paper

- Finding Statistics and Data for Research Papers

- Writing an Annotated Bibliography for a Paper

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- What Is an Autobiography?

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- What Is a Bibliography?

Senior Thesis

Undergraduate Program Office 609-258-4861 [email protected]

The senior thesis is a scholarly paper focused on the policy issue in public or international affairs that is of greatest interest to the student. It is based on extended research and is the major project of the senior year.

Each student must complete a senior thesis that addresses a specific policy question and either draws out policy implications or offers policy recommendations (or both).

The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs awards several scholarships each year for travel and living expenses related to senior thesis research.

The University’s requirement for a senior comprehensive examination is satisfied in the School by an oral defense of the thesis. Students prepare a response to written evaluations from their thesis advisor and a second reader, followed by a question-and-answer period.

Senior Thesis Advising: The Senior Thesis Advisor Selection Guide - Students should use this to identify thesis advisors who match their interests and possible thesis topics. This tool is organized by faculty issue and regional expertise.

Senior Thesis Deadlines

Thesis Proposal Form Due Friday, September 20, 2024

You must submit your thesis proposal form, signed by your advisor, via email to [email protected] by 12pm (noon) on Friday, September 20, 2024.

First Semester Progress Report Due Monday, December 9, 2024

You must submit your first-semester progress report to your advisor and to [email protected] by 12pm (noon).

Complete Draft Monday, March 10, 2025

First drafts of all of your chapters are due to your thesis advisor by 12pm (or earlier per any agreement with your thesis advisor).

Thesis Due Friday, April 4, 2025

An electronic copy must be submitted to the Undergraduate Program Office ( [email protected] ) by 12:00 p.m. (noon). Upload a PDF of your thesis, for archiving at MUDD Library, via the centralized University Senior Thesis Submission Site . See page 9 of the Senior Thesis Guide for additional thesis deadline information.

Oral Examinations May 7th – May 8th, 2025

The University’s requirement for a senior comprehensive examination is satisfied by an oral examination based on your thesis.

Guide to Senior Independent Work

Please review this document completely and thoroughly for more information on your senior thesis.

Getting Started in Data Analysis: Topic Selection and Crafting of a Research Question - Independent research projects start with the selection of a topic and the crafting of a feasible research question. This video maps the initial steps to help...

All independent work that involves research with human subjects must first be reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board . The mission of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is to protect the rights, privacy, and welfare of human participants in research conducted by faculty, staff, and students.

If you plan to conduct research involving human subjects for your Senior Thesis, you must first consult with IRB prior to beginning your interviews to determine whether an IRB application, review, and approval are required for our project. The department recommends Seniors should complete the process in October or November, if possible.

Email a synopsis of the proposed activity (3 paragraphs) to the IRB: [email protected] . Include the draft measurements (survey, questionnaire, interview guide), if applicable.

Please visit the eRIA-IRB training site for more information.

Should you have questions as you prepare the materials, please consult IRB at [email protected] or your advisor for assistance.

SPIA Thesis Funding - Students can apply for funding by accessing the online application in the Student Activities Funding Engine (SAFE)

In addition to your consultations with your thesis advisor, we strongly recommend that you meet regularly with the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs Writing Advisor, for assistance in conceptualizing and organizing your thesis, developing your arguments, and reviewing your writing. They can best help you if you meet with him early in (as well as throughout) the process. Writing advisors can be reached at [email protected] .

Library Resource Guide - A guide for seniors who are conducting thesis research

An excellent senior thesis can be 75 pages or less. No thesis should be longer than 115 pages. Any page after 115 may or may not be read by the second reader. A thesis longer than 115 pages will not be considered for a SPIA thesis prize.

The 115-page limit includes:

- the abstract

- the table of contents

- ancillary material such as tables and charts

- all footnotes

The page limit does not include:

- the title page

- the dedication

- the honor code statement

- the bibliography

Include the Honor Pledge, and your signature on the last page.

Use a 1-inch margin on the left, right, top and bottom.

Double-space all text (except long quotations, footnotes and bibliography).

Number your pages.

Make sure the thesis is single sided.

Use a 12‑point size type and a readable font. Avoid the use of multiple fonts and type sizes(other than footnotes, which may be in a smaller font).

Indent paragraphs and avoid paragraphs longer than a page.

Within chapters, use only two levels of headings, either in bold or underlined and placed at the left margin or centered. The primary heading is all caps, the secondary is caps and lower case:

Pages should be organized as follows:

Title page (see format on next page)

Second page: Dedications (optional)

Third page: Acknowledgements

Fourth page: Table of Contents

Fifth page: Abstract

Last page: The last page must contain the following: This thesis represents my own work in accordance with University Regulations. Your signature

Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library Senior Thesis Catalog - is a catalog of theses written by seniors at Princeton University from 1926 to present

The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs will grant extensions only for severe personal illness, accident, or family emergency. The request for an extension must be made in writing. Extensions to a date no later than the University’s deadline for submitting senior independent work may be granted by the Undergraduate Program Faculty Chair, Susan Marquis, [email protected] . After this deadline, extensions may be granted only by the Dean of your residential college.

Under no circumstances will extensions be granted for any reason connected with computer problems . Students should therefore save, backup, print their work in a manner designed to prevent last-minute crises.

One-third of the thesis final grade will be deducted for each four days (or fraction of four days) that the thesis is late. Please see the Guide to Independent Work for more information.

Submit one electronic copy in PDF format to the SPIA undergraduate office, [email protected] , by the Deadline. Must also upload a PDF of your thesis, for archiving at MUDD library, via a centralized University Senior Thesis Submission Site .

The thesis is graded by the thesis advisor, who is the first reader of the senior thesis, and by a second reader assigned by the Undergraduate Program Office. The grade is calculated as follows:

- If the readers' grades are identical, that is the final grade.

- If the readers' grades differ by one full grade (e.g., A to B) or less, the average grade is the final grade.

- If the readers’ grades differ by more than one full letter grade, the two readers consult to determine the final grade; if they are unable to agree, the Faculty Chair of the Undergraduate Program determines the grade.

The Undergraduate Program office will determine any penalty for lateness, which will be included in the grade reported to the Registrar .

A thesis that receives a grade of A or higher and a statement of support from both readers (and is within the page limit) may be considered for a Princeton School of Public and International Affairs thesis prize. Prizes are awarded by a specially appointed School faculty committee that weighs the relative merits of all theses under consideration. Prizes are presented at the Class Day ceremony.

SPIA Prize Theses - Sample Prize theses from 2017 to present

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, preparing for a senior thesis.

Every year, a little over half of Harvard’s senior class chooses to pursue a senior thesis. While the senior thesis looks a little different from field to field, one thing remains the same: completion of a senior thesis is a serious and challenging endeavor that requires the student to make a genuine intellectual contribution to their field of interest.

The senior thesis is a significant task for students to undertake, but there is a variety of support resources available here at Harvard to ensure that seniors can make the best of their senior thesis experience.

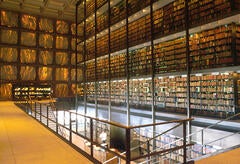

Wandering the library stacks at Widener.

I do most of my research in Widener Library. Hannah Martinez

As a rising senior in the History department, I am planning on pursuing a senior thesis on the history and use of the SAT in college admissions, and I am using the following support systems and resources to research and write my thesis:

- Staff at the History department. Every student within the department is assigned an academic advisor, who is a graduate student studying History at Harvard and knows the support available within the department. My academic advisor has helped me throughout the thesis process by connecting me with potential faculty members to advise my thesis and pick classes with a lighter course load so I can focus on completing my thesis. The Director of Undergraduate Studies in History (the History DUS) has also been pivotal in making sure that I attended a lot of information sessions about what the thesis looks like and how much of a commitment it is.

- History faculty at Harvard! All of my professors in History have been incredibly helpful in teaching me how to write like a historian, how to use primary sources in my essays, and how to undertake a serious research project over the course of a semester. Of course, while the thesis will require me to go far beyond what I’ve ever done before, I feel prepared to take on such a task because of the unwavering support from the History faculty. My mentor, Emma Rothschild, is one of the members of the faculty who has been invaluable in encouraging me to go as far as I am able.

- And last but certainly not least: funding. Funding, whether in term-time of the summer before senior year, is crucial towards making the senior thesis possible. Harvard’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships is dedicated to connecting Harvard students to funding sources across the university so they can pursue their research and get paid for it. This summer, I received a grant from the university of almost $2,000 so I am able to travel to libraries, buy books, and potentially take time off of work and do my research. Without such a grant, it would be incredibly difficult for me to do enough research so I can write a thesis this upcoming fall.

As you can see, there are multiple avenues for support and resources here at Harvard so your senior thesis is as easy as possible. While the senior thesis is still a challenging project that will take up a lot of time, Harvard’s resources make it possible for senior students to do their very best in all of their theses. I’m excited to start writing this fall!

Hannah Class of '23 Alumni

Hello! My name is Hannah, and I am a rising senior at Harvard concentrating in History from southeast Los Angeles County.

Student Voices

My unusual path to neuroscience, and research.

Raymond Class of '25

Senior Thesis: A Daunting and Fulfilling Journey

Angelica Class of '24

How the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Propelled My Love of Archives into Academic Aspirations

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Senior Thesis Writing Guides

The senior thesis is typically the most challenging writing project undertaken by undergraduate students. The writing guides below aim to introduce students both to the specific methods and conventions of writing original research in their area of concentration and to effective writing process.

| ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR SENIOR THESIS WRITERS |

|

Author: Andrew J. Romig

See also | |

|

Author: Department of Sociology, Harvard University

See also the r | |

|

Author: Department of Government, Harvard University

| |

|

Author: Nicole Newendorp

| |

|

Authors: Rebecca Wingfield, Sarah Carter, Elena Marx, and Phyllis Thompson

| |

|

Author: Department of History, Harvard University

See also | |

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

- Course-Specific Writing Guides

- Disciplinary Writing Guides

- Gen Ed Writing Guides

Senior Theses

- Categories: Strategies for Learning

Doing a senior thesis is an exciting enterprise. It’s often the first time students are engaging in truly original research and trying to develop a significant contribution to a field of inquiry. But as joyful as an independent research process can be, you don’t have to go it alone. It’s important to have support as you navigate such a large endeavor, and the ARC is here to offer one of those layers of support.

Whether or not to write a senior thesis is just the first in a long line of questions thesis writers need to consider. In addition to questions about the topic and scope of your thesis, there are questions about timing, schedule, and support. For example, if you are collecting data, when should data collection start and when should it be completed? What kind of schedule will you write on? How will you work with your adviser? Do you want to meet with your adviser about your progress once a month? Once a week? What other resources can you turn to for information, feedback, and support?

Even though there is a lot to think about and a lot to do, doing a thesis really can be an enjoyable experience! Keep reminding yourself why you chose this topic and why you care about it.

Tips for Tackling Big Projects:

- When you’re approaching a big project, it can seem overwhelming to look at the whole thing at once, so it’s essential to identify the smaller steps that will move you towards the completed project.

- Your advisor is best suited to help you break down the thesis process with field-specific advice.

- If you need to refine the breakdown further so it makes sense for you, schedule an appointment with an Academic Coach . An academic coach can help you think through the steps in a way that works for you.

- Pre-determine the time, place, and duration.

- Keep it short (15 to 60 minutes).

- Have a clear and reasonable goal for each writing session.

- Make it a regular event (every day, every other day, MWF).

- time is not wasted deciding to write if it’s already in your calendar;

- keeping sessions short reduces the competition from other tasks that are not getting done;

- having an achievable goal for each session provides a sense of accomplishment (a reward for your work);

- writing regularly can turn into a productive habit.

- In addition to having a clear goal for each writing session, it’s important to have clear goals for each week and to find someone to communicate these goals to, such as your adviser, a “thesis buddy,” your roommate, etc. Communicating your goals and progress to someone else creates a useful sense of accountability.

- If your adviser is not the person you are communicating your progress to on a weekly basis, then request to set up a structure with your adviser that requires you to check in at less frequent but regular intervals.

- Commit to attending Accountability Hours at the ARC on the same day every week. Making that commitment will add both social support and structure to your week. Use the ARC Scheduler to register for Accountability Hours.

- Set up an accountability group in your department or with thesis writers from different departments.

- It’s important to have a means for getting consistent feedback on your work and to get that feedback early. Work on large projects often lacks the feeling of completeness, so don’t wait for a whole section (and certainly not the whole thesis) to feel “done” before you get feedback on it!

- Your thesis adviser is typically the person best positioned to give you feedback on your research and writing, so communicate with your adviser about how and how often you would like to get feedback.

- If your adviser isn’t able to give you feedback with the frequency you’d like, then fill in the gaps by creating a thesis writing group or exploring if there is already a writing group in your department or lab.

- The Harvard College Writing Center is a great resource for thesis feedback. Writing Center Senior Thesis Tutors can provide feedback on the structure, argument, and clarity of your writing and help with mapping out your writing plan. Visit the Writing Center website to schedule an appointment with a thesis tutor .

- Working on a big project can be anxiety provoking because it’s hard to keep all the pieces in your head and you might feel like you are losing track of your argument.

- To reduce this source of anxiety, try keeping a separate document where you jot down ideas on how your research questions or central argument might be clarifying or changing as you research and write. Doing this will enable you to stay focused on the section you are working on and to stop worrying about forgetting the new ideas that are emerging.

- You might feel anxious when you realize that you need to update your argument in response to the evidence you have gathered or the new thinking your writing has unleashed. Know that that is OK. Research and writing are iterative processes – new ideas and new ways of thinking are what makes progress possible.

- It’s also anxiety provoking to feel like you can’t “see” from the beginning to the end of your project in the way that you are used to with smaller projects.

- Breaking down big projects into manageable chunks and mapping out a schedule for working through each chunk is one way to reduce this source of anxiety. It’s reassuring to know you are working towards the end even if you cannot quite see how it will turn out.

- It may be that your thesis or dissertation never truly feels “done” to you, but that’s okay. Academic inquiry is an ongoing endeavor.

- Thesis work is not a time for social comparison; each project is different and, as a result, each thesis writer is going to work differently.

- Just because your roommate wrote 10 pages in a day doesn’t mean that’s the right pace or strategy for you.

- If you are having trouble figuring out what works for you, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach , who can help you come up with daily, weekly, and semester-long plans.

- If you’re having trouble finding a source, email your question or set up a research consult via Ask a Librarian .

- If you’re looking for additional feedback or help with any aspect of writing, contact the Harvard College Writing Center . The Writing Center has Senior Thesis Tutors who will read drafts of your thesis (more typically, parts of your thesis) in advance and meet with you individually to talk about structure, argument, clear writing, and mapping out your writing plan.

- If you need help with breaking down your project or setting up a schedule for the week, the semester, or until the deadline, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach .

- If you would like an accountability structure for social support and to keep yourself on track, come to Accountability Hours at the ARC.

Department of Physics

Senior Theses

The senior thesis is the capstone of the physics major and an opportunity for intellectual exploration broader than courses can afford. It is an effort that spans the whole academic year. The thesis is a great opportunity to dive into research on an aspect of physics which most engages you. Whether your thesis is on biophysics, gravity and cosmology, condensed matter, or string theory, writing it is way to put to use all that you have learned in coursework so far—and to make a contribution to scientific knowledge. Even for topics outside of the mainstream of physics, for example with a focus on policy, or neuroscience, or finance, we expect you to apply your undergraduate physics education to the problem you focus on.

You can build on previous work in your senior thesis, for example summer work or a junior paper. However, it is equally acceptable to start a brand new project in the fall of your senior thesis with an adviser you have not previously worked with. In any case, in order to have a level playing field, your thesis will be evaluated based on work done during the academic year.

You must submit your choice of adviser and topic in Canvas by 3:00pm October 3. Your adviser must have a full-time faculty appointment at Princeton University. Your adviser can be one of your junior paper advisers, but need not be. If your adviser does not have their primary appointment in the Physics Department, you must communicate your choice of second reader in Canvas by October 3, and this second reader must have a full-time faculty appointment at Princeton University with their primary appointment in the Physics Department.

You must turn in a draft of content for your senior thesis by 3:00pm January 16, as explained in the section entitled Fall term draft .

The final version of your senior thesis is due by 3:00pm of the University's deadline for submitting the senior thesis, April 29. The requirements for formatting and submitting your final senior thesis are somewhat detailed; please consult the section entitled Thesis Formatting and Submission . The page on important dates gives a complete listing of dates and deadlines relevant to the senior thesis. In case of any confusion about dates and deadlines, the page on important dates should be regarded as authoritative.

An oral examination conducted by the the Senior Committee at the end of the senior year serves as the senior departmental examination. This exam is described in more detail below in the section entitled Oral Examination .

Department of Physics Independent Work Guide

Senior committee.

A committee of several faculty in Physics oversees all the senior theses. In AY 2024-2025, the committee members are Professor(s) William Jones (chair), Lyman Page, Shinsei Ryu and Jason Puchalla. The senior committee is assisted by Karen Olsen, the Undergraduate Administrator. The committee meets with the seniors at the beginning of the academic year to outline what is expected and to help them get started on choosing advisers and topics. The committee may establish milestones during the year (e.g. a due date for a thesis outline and/or an oral progress report) in addition to the ones indicated on this webpage; any such additional milestones will be announced to all seniors via e-mail and clearly indicated on the important dates page. You are encouraged at any time to approach members of the senior committee with questions or concerns about the progress of your thesis work.

Getting Started

The best advice in finding an advisor is to go to several faculty members in areas of research that you are interested in, and see what topics they propose. If you have a topic to propose yourself, great: shop it around to faculty and see what they think. Most topics come from faculty as part of the work their research groups are conducting. When you have a tentative topic in mind, start by reading some of the literature, ideally at the Scientific American level, in order to understand the highlights and context of the work you'll embark on. If you're undecided between topics, this first stage of reading should help you choose. Make sure to circle back to your prospective adviser with questions, and confirm with them before the deadline that they are in fact prepared to advise you on a topic that you have both agreed on. It's important to start this process at the very beginning of term, because false starts are possible.

The most important advice we can give is to make a fast start on your senior thesis, and focus on it particularly at the start of the fall term. Adjust your courses accordingly; for instance, senior fall is not the right time to shop five courses. Experience suggests that distractions and delays occur from time to time, both expected (e.g. grad school applications) and unexpected (e.g. your adviser disappears to a conference just when you need help). If you have a good start on your thesis you can put it aside briefly when such a delay occurs. If you don't, it becomes harder and harder to catch up. Regardless of where you are in the term—and especially early on—the best advice is to set your senior thesis at top priority.

Students considering thesis topics mostly or entirely outside of physics should consider the application procedure outlined in the section below entitled Alternative grading rubric . Please note that time is of the essence in applying for an alternative grading rubric.

Fall Term Draft

A draft of content to be included in your senior thesis must be turned in to Canvas by 3:00pm on January 16. The second reader must be identified in Canvas at the time you turn in this draft of content. (Even if you have previously identified your second reader, e.g. because you are working with a primary advisor outside the department, please confirm this choice at the time of turning in your draft of content.) This draft of content will be assigned a P/D/F grade by your advisor and second reader, and the grade will be reported to the senior committee; however, it will not appear on your Princeton transcript. The draft of content is intended to serve as a status check and a way to start the conversation with your advisor and second reader about the spring term end game for your thesis. The guidelines for the draft of content are as follows:

- The minimum length is 7 pages, plus front matter and bibliography.

- The document should be written in full sentences and paragraphs, in the style you intend for the final version of your senior thesis. An outline of work to follow can be included at the end, but the main focus of the document should be on what you have understood and done so far.

- Formatting should be the same that you intend to use in the final version of your senior thesis; in particular, front matter (including the Student Acknowledgment of Original Work, signed), introduction, main body, and bibliography should be present, with all the formatting as you intend for the final version of your senior thesis. In short, follow the guidelines in the Primary grading rubric . Indicate clearly in the front matter that the document is a draft of content.

- While it is anticipated that your results will be quite incomplete, do make an effort to communicate the background in an accessible fashion that starts with the fundamentals and demonstrates your understanding of the context of your ongoing work.

Thesis Formatting and Submission

You must submit your thesis electronically as a PDF file. The first few pages of your senior thesis are called the front matter. Front matter must include in the first two pages the title, the student's name, an abstract, the Student Acknowledgment of Original Work, and a signature following this acknowledgment. The wording of the Acknowledgment must be as set forth in the current edition of Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities: "This paper represents my own work in accordance with University regulations.” The Page formatting should be suitable for printing on standard 8.5" x 11" paper with one to one and a half inch margins all around the main text. All fonts should be between 10 and 14 points, and line spacing should be anywhere between double spacing and 1.5 spacing. Pages should be numbered, with numbers no closer than half an inch to any edge of the page. Figures should be clear and legible, with descriptive captions. Figures should be your original work or else credit should be clearly given in the caption to the figure creator. You should request permission to re-use figures made by colleagues. There is no length requirement, but a total length (including front matter, bibliography, figures, appendices, etc) of 50 to 100 pages is about right for most topics.

The deadline for submission of the senior thesis is 3 pm April 29. For the spring semester of 2024, no hard copy submission will be required. By that deadline, you must submit your thesis electronically in Canvas. You must provide an electronic signature for the Student Acknowledgment of Original Work. Your signature will serve as confirmation that the submitted version is the official version. By the end of the day on April 29, you must also send electronic copies of your thesis to your advisor and second reader. You must also submit your thesis electronically to Mudd Library in order to graduate. Details on the Mudd Library submission process will come by email.

To set high goals for the thesis, and at the same time to accommodate the breadth of experience that physics majors seek, the Physics Department has a dual rubric approach to grading. The primary grading rubric for the senior thesis is the one set forth in detail in the section below entitled Primary grading rubric . It should be used for all theses which are primarily focused on a topic in physics, broadly construed. Applied physics, biophysics, astrophysics, plasma physics, and mathematical physics (among others) are fields in which this primary rubric should be used. Every student is advised to take pains to make their thesis accessible to physicists outside their discipline. Doing so is part of good presentation, and it is part of showing the student's own mastery of their topic. The physical principles involved should be explained clearly, starting at the level of undergraduate physics courses. Any necessary jargon should be introduced with clear explanations.

Written presentation is also important and will affect the final grade. Good presentation includes all aspects of scholarly writing, including clear explanations, organization, and citations; correct spelling, grammar, and formatting; a style that is at once accessible and precise; and a logical structure including front matter, introduction, main body, conclusion, and bibliography.

Primary grading rubric

The main basis for the final grade will be the physics content contained in the thesis as a document. Physics content could include, for example, theoretical ideas, calculations, modeling, and predictions; experimental methods, description of apparatus, results, and data analysis; and an assessment of the significance of the work reported in the thesis against the backdrop of the larger field of which it is part. Physics content can be particularly noteworthy—for instance a really new theoretical idea or a genuinely impactful experimental result—but humbler advances, such as verification or extension of published calculations, or successful calibration of an experimental device, are also highly esteemed. In short, new research results are desirable but not required for even the highest grades. Scholarly substance is the key.

Written presentation is also important and will affect the final grade. Good presentation includes all aspects of scholarly writing, including clear explanations, organization, and citations; correct spelling, grammar, and formatting; a style that is at once accessible and precise; and a logical structure including front matter, introduction, main body, conclusion, and bibliography.

Grade recommendations from the adviser and second reader are communicated to the senior committee, along with short text descriptions describing and assessing the thesis. The letter grade from the Oral examination will count for 10% of the senior thesis grade. The following grade descriptions are representative of Physics Department grading practices. Any individual thesis may have qualities spread across several of these descriptions, and it is ultimately up to the judgement of the Physics Department faculty to balance the considerations in any given case in order to come up with the final grade.

- A+. A substantial, professional-level contribution to some field of physics, with outstanding presentation and truly impressive content. For example, there may be original results suitable or almost suitable for publication in a peer-reviewed journal which physicists working in this field often publish in. Or the thesis may be a brilliantly written review paper which could usefully be shared with professional colleagues. A written statement from the advisor justifying the A+ must be included.

- A. The thesis deals with some topic in physics in an unusually thorough way, with unexpected insights and/or an especially clear presentation. The advisor should have learned new things from it. This grade should be used for work that goes far beyond "doing a good job."

- A-. The thesis covers some topic in physics well and goes into significant depth. It is written in a professional style with only minor flaws. The student shows mastery of the subject.

- B+. The thesis covers a topic in physics well, and in some depth. The presentation and physics content are good but leave room for improvement.

- B. The thesis covers a topic in physics fairly well. Presentation and physics content are fairly good, but some deficiencies may be noted.

- B-. The thesis addresses a topic in physics but without the depth expected for senior independent work. There may be significant errors or an inadequate presentation.

- C+. The thesis contains an overview of a topic in physics, but the physics content is mostly superficial. The presentation may be inadequate, and there may be significant errors or omissions.

- C. The thesis contains a partial or superficial overview of a topic in physics. The thesis gives little evidence of understanding of the relevant physics. The presentation is sloppy, and there are significant errors or omissions.

- C-. The thesis contains some correct information about a topic in physics, but it fails to show understanding of the relevant physics. The presentation is incomplete, with serious errors or omissions.

- D. The lowest passing grade. The thesis is deficient in multiple respects, with minimal physics content, poor presentation, and/or poor scholarship.

- F. There are several ways an F can result. One way is for the thesis to be largely incomplete and incorrect. A second way is for the thesis not to be turned in on time, accounting for any extensions granted, or for a document to be turned in without a clear written indication that it is the official version of the student's senior thesis. A third way is for the thesis to be turned in on time but with issues that prevent it from being accepted. Examples of this last are omitting from the first two pages the title, the student's name, the abstract, the Student Acknowledgment of Original Work, or a signature following this acknowledgment. Formatting that renders the thesis unreasonably difficult to read may also prevent it from being accepted and result in an F.

Alternative grading rubric

Students wishing to branch out and work on a senior thesis topic that is mostly or entirely outside of physics will have their theses graded using an alternative grading rubric customized to their field of work, provided they receive approval from the senior committee of a proposal submitted electronically in Canvas no later than 3pm October 10. The proposal must consist of the following points:

- Student's name.

- Adviser's name. The adviser must sign next to their name to indicate their endorsement of the proposed grading rubric.

- Second reader's name. As with all theses in the Physics Department, your adviser and the second reader should both have full-time faculty appointments at Princeton University, and at least one of them should have their primary appointment in the Physics Department.

- A tentative thesis title (200 characters or less).

- Summary of proposed work (1500 to 2000 characters).

- Give us a simple description of the area of scholarship your thesis falls in. For example, "Climate policy" or "Behavioral neuroscience."

- Provide a short explanation of why you are interested in this area, and why it should be of general interest to professional physicists.

- Provide an adaptation of the primary grading rubric that you feel is suitable to your thesis work. The text to adapt is the entire contents of the section entitled Primary grading rubric . Leave the second, third, and fourth paragraphs unchanged, as these sections will be applied in any case; likewise the criteria for an F cannot be changed. Changes to the rest of the text should be at the minimal level needed in order for it to be fairly applied to the work you are going to do. For example, if you are working on climate policy, replacing "physics" by "climate policy" throughout should be a good start. Topics which have some physics content but are primarily outside of physics should include in the grading rubric some measure of how well the physics is developed and presented.

The senior committee may adjust or rewrite the grading rubric you propose before approving it, and the final rubric will go to your adviser and second reader as well as to you.

Proposals that are approved will allow a thesis to be graded at the same standard as other Physics Department senior theses, but in a different direction. Students who do pursue a topic outside of physics should make a particular effort to make their thesis accessible to physicists and students of physics, and this effort will be counted as part of a good presentation. If a proposal is not received on time by the senior committee or is not approved, thesis work will be graded according to the Primary grading rubric : In particular, the physics content will then be the main basis for the final grade.

A fall term draft of content as outlined in the section entitled Fall term draft is required for all theses.

Oral examination

The oral examination will be scheduled near the end of the academic year, after you have turned in your senior thesis. You should prepare a presentation with a planned duration of 20 minutes. Use standard visual aids, i.e. PowerPoint or similar. Presentations should be well organized and thoughtful; in particular:

- If you want to use a laptop, you are responsible for making sure things work!

- Have enough paper copies of your presentation material so that every committee member can have their own copy. Paper copies are useful even when you use PowerPoint from a laptop and serve as a backup in case of a technical glitch.

- Limit your main presentation to approximately 15 slides (depending on your style). If you have more material, prioritize it and put extra material at the end as backup slides.

- Do not expect committee members to flip through your thesis during the exam; your presentation should be self-contained.

- Emphasize graphical material in your slides (including key equations).

- If you have text in your slides, focus on terse summaries and avoid long segments of text.

- Rehearse! You can rehearse before a group of friends, or your advisor, or a graduate student, or an empty room.

The senior committee is entitled to ask questions both about the thesis and about undergraduate physics. The grade for the oral depends on both the quality of the presentation and your ability to answer questions.

The oral examination will be assigned a letter grade by the senior committee. The letter grade for the oral examination will count for 10% of the senior thesis grade.

Psychology Junior Paper and Senior Thesis Guide

- Research Consultations

- Junior Paper Guidelines

Senior Thesis Guidelines

Senior thesis requirements.

- Examples of Senior Theses

- Psychology Literature

- Keyword Searching

- Literature Mapping This link opens in a new window

- Evaluating Articles

- Finding the Full Text

- Reference Managers

- Peer Review

Current guidelines for Psychology Senior Theses can be found on the Department of Psychology's website .

Students can conduct an experimental thesis, a computational thesis, or a theoretical thesis. All formats require a review of the literature .

- An experimental thesis should include a comprehensive literature review, findings from at least one original research study (an experiment or a field study) with appropriate statistical analyses, and a general discussion of the findings.

- A computational thesis should include a review of the literature and description and discussion of the computational models that the student has completed.

- A theoretical thesis should include a comprehensive review of the research literature on a psychology topic of importance, including an extensive evaluation of the findings and original interpretations, theoretical proposals, or a proposed program of research to add further scientific knowledge.

- << Previous: Junior Paper Guidelines

- Next: Examples of Senior Theses >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 11:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/psyc_jp_thesis

Department of History

Senior Thesis Guidelines

Your thesis must be printed or typewritten in black-letter type upon plain white paper (any kind of paper is acceptable). The text must be double-spaced, with wide margins and paragraphs clearly indented. Although there is no fixed requirement, you should be careful to leave enough space on the left to allow for binding, and enough on the right, top, and bottom so that your thesis will look presentable. (An inch and a half on the left and an inch on the right, top, and bottom should be adequate.) It must be a single-sided document.

The title page should contain the title, name of author, date, and the following statement: "A senior thesis submitted to the History Department of Princeton University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts."

On a separate page you should certify that "This paper represents my own work in accordance with University regulations" and sign your name.

A table of contents listing the title and page number of each chapter should follow the title page. On a page preceding the table of contents, you may wish to acknowledge any special assistance or support that you received in writing your thesis.

The prescribed minimum length of text only, excluding appendices, charts, bibliography, illustrations, or images, is 75 pages. The prescribed maximum length is 100 pages. No thesis may exceed 100 pages unless permission of the thesis adviser is obtained in advance. Font size is required to be similar to Times New Roman 12, though it need not be in Times New Roman. The text must be double-spaced, with wide margins and paragraphs that are clearly indented. (Margins of an inch on the left, right, top, and bottom should be adequate.) It can be printed double-sided.

A PDF copy of the thesis must be submitted electronically. A copy must also be deposited with the Mudd Library Thesis Archive. Submission details will be sent to seniors one month before the deadline. For 2021 hard copies are not required.

The following guidelines provide advice on general styling and formatting questions.

General Usage

Use quotations sparingly, keep them brief, and work them into the flow of your own narrative. If a long quotation must be used, take it out of the body of the text, indent, and single-space. Quotations treated in this manner are called block quotations. Quotation marks are not used for block quotations.

The omission of a word or phrase from a quotation is indicated by an ellipsis, or three spaced periods (. . .), at the point of omission. If the omitted words would have ended a sentence, a fourth period should be added to indicate the normal terminal punctuation.

A quotation must conform to the original in every detail. Do not correct misspellings or other errors, but insert after them the Latin word sic in brackets [ sic ] to show that the error was in the original. Brackets, not parentheses, are used to insert a clarifying word or phrase of your own into quoted material. When your thesis is completed, you should check all quotations against the original sources to ensure absolute accuracy.

Footnotes must be used to indicate the sources of:

- all quotations and statistical data;

- all facts not generally known to historians; and

- all opinions or interpretations that are not your own, whether quoted, paraphrased, or summarized.

Footnotes may also include your comments on the sources, remarks on disagreement among authorities, additional quotations, or essential information that cannot appropriately fit into the text. Generally speaking, anything worth saying at all is worth saying in the text. Do not use your footnotes as a dumping ground for surplus data.

Start a new set of footnotes, starting at 1, with each chapter. The footnote number, elevated above the line of type, should come at the end of the sentence for which a citation is needed. If the material in one or more paragraphs is all derived from a single work, put your footnote at the end of the section containing this material. If a single sentence or paragraph contains material from a number of sources, the sources may all be cited in the same footnote, separated by semicolons.

Footnotes should be placed at the bottom of the page upon which the material in question appears. They should be separated from the text by a short black line beginning at the left hand margin. Subject to your adviser’s approval, notes may be typed consecutively at the end of each chapter. In either case, the notes should be single-spaced with the first line of each note indented.

There is no single, universally accepted set of rules for citations. You probably will notice in your reading that different publishers and authors use different forms of footnotes. However, most historians follow the so-called Chicago style, which is based on the Chicago Manual of Style , and this is the format recommended by the Department of History. Still, the most important criterion is clarity and consistency: your notes should present all the pertinent information in as direct and simple a fashion as possible, and you should use the same format throughout your thesis.

The first time you cite a book, give the author's full name, the full title of the book as it appears on the title page, the place of publication, the publisher's name, the date of publication, and page from which your material has been drawn. Note that the publication data is enclosed in parentheses. For example:

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Robert Kennedy and His Times (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978), 231.

Multivolume Work

When all the volumes in a multivolume work have the same title, a reference to pages within a single volume is given in the following manner. (Note that the volume number is given in Arabic numerals and that the volume and page numbers are separated by a colon.) For example:

- James Schouler, History of the United States of America, under the Constitution (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1904), 4:121.

When each volume in a multivolume work has a different title, a reference to pages within a single volume is given as follows:

- Forrest C. Pogue, George C. Marshall, vol. 4, Statesman, 1945-1959 (New York: Viking, 1987), 31.

Article in a Scholarly Journal

For the first citation of an article, give the author's full name, the full title, and the name, volume number, month and year, and page number of the journal or quarterly. For example:

- Edwin S. Gaustad, “The Theological Effects of the Great Awakening in New England,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review , 40 (March 1954), 690.

Subsequent Citation

Subsequent citations of the same book or article should give only the author's last name and an abbreviated (short) title. For example:

- Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy , 295.

- Gaustad, “Theological Effects of the Great Awakening,” 693-695.

Use of the Abbreviation 'Ibid'

If a footnote refers to the same source that was cited in the immediately preceding footnote, the abbreviation ibid. (for ibidem , which means “in the same place") may take the place of the author’s name, title of the work, and as much of the succeeding material as is identical. For example:

- Ibid., 699.

Collected Works

In citing printed collected works such as diaries or letters, the author’s name may be omitted if it is included in the title. The name of the editor follows the title, preceded by a comma and the abbreviation “ed.,” which stands for “edited by.” For example:

- An Englishman in America, 1785, Being the Diary of Joseph Hudfield , ed. Douglas S. Robertson (Toronto: Hunter-Rose, 1933), 23.

In citing correspondence from manuscript collections, give the full names of the writer and recipient, the date the letter was written, and the manuscript collection in which it may be found. The first time a collection is cited, its name should be given in full and its location should be indicated. Subsequent citations should abbreviate the name of the collection and omit location of the collection. For example:

- James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, May 6, 1791, Andre De Coppet Collection, Firestone Library, Princeton University.

- James Madison to George Washington, Feb. 18, 1788, De Coppet Collection.

In the case of large collections, you should indicate the number of the box (or designation of the file) in which the cited material may be found. For example:

- Adlai E. Stevenson to John F. Kennedy, Jan. 12, 1961, Adlai E. Stevenson Papers, Box 310, Seeley G. Mudd Library, Princeton University.

Article in a Popular Magazine

It is not necessary to cite the volume or issue number of a magazine of general interest. Note, however, that the abbreviation “p” is required to distinguish clearly between the date of publication and page number. For example:

- Michael Rogers, “Software for War, or Peace: All the World’s a Game,” Newsweek , Dec. 9, 1985, p. 82.

For reference to a newspaper, the name of the paper and date usually are sufficient. However, for large newspapers, particularly those made up of sections, it is desirable to give the page number. For example:

- Washington Globe , Feb. 24, 1835

- Richmond Enquirer , May 15, 1835.

- New York Times , Oct. 24, 1948, p. 17.

Include as much of the following information as is available: author, title of the site, sponsor of the site, and the site’s URL. When no author is named, treat the sponsor as the author. For example:

- Kevin Rayburn, The 1920s , http://www.louisville.edu/~kprayb01/1920s.html .

The Chicago Manual of Style does not advise including the date that you accessed a Web source, but you may provide the date after the URL if the cited material is time sensitive.

Abbreviation

Should you cite certain sources repeatedly, you may wish to develop a system of abbreviations to simplify your footnotes. In this case, a page explaining the abbreviations should follow the table of contents. For example:

DOHC - Dulles Oral History Collections FRUS - Foreign Relations of the United States NYT - New York Times

Sample Footnotes

- Edwin S. Gaustad, "The Theological Effects of the Great Awakening in New England," Mississippi Valley Historical Review , 40 (March 1954), 690.

- Gaustad, "Theological Effects of the Great Awakening," 693-695.

- James Madison to George Washington, Feb. 19, 1788, De Coppet Collection.

- Washington Globe , Feb. 24, 1835; Richmond Enquirer, May 15, 1835.

- Kevin Rayburn, The 1920s , http://www.louisville.edu/~kprayb01/1920s/html .

For additional guidance and examples of Chicago-style documentation, see Footnotes made easy: a guide for history majors , which is posted in the Department of History’s Library Resources . (Do not hesitate to ask your thesis adviser for assistance in determining the appropriate format.)

Bibliography

General requirements.

The bibliography should list all primary and secondary sources that are actually used in writing your thesis. Bibliographies of theses that draw upon archival and manuscript sources normally are divided into sections. Sources are listed alphabetically by author, editor, or publishing agency (when no author or editor is given). Single-space each item with double-spacing between items and sections of the bibliography. The following is an acceptable model for delineating various categories of primary and secondary sources.

Primary Sources

Government Archives

- Records of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Record Group 218. National Archives and Records Service, Washington, D.C.

Manuscript Collections

- Stevenson, Adlai E. Papers. Seeley G. Mudd Library, Princeton University.

Government Documents

- U.S. Congress. House. Committee on Naval Affairs. Hearings on H.R. 9218 . 75th Cong., 3rd sess., 1938.

- U.S. Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1944. Vol. 4, Europe . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1966.

Memoirs and Collected Papers

- Hudfield, Joseph. An Englishman in America, 1785, Being the Diary of Joseph Hudfield . Edited by Douglas S. Robertson. Toronto: Hunter-Rose, 1933.

Contemporary Journals and Newspapers

- New York Times , 1921-1923.

Secondary Sources

Books and Articles

- Campbell, Mildred, The English Yeoman under Elizabeth and the Early Stuarts . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1942.

- Gaustad, Edwin S. "The Theological Effects of the Great Awakening in New England," Mississippi Valley Historical Review , 40 (March 1954), 681-706.

- Schouler, James. History of the United States of America, under the Constitution . 6 vols. Rev. ed. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1904.

Unpublished Material

- Rigby, David Joseph. “The Combined Chiefs of Staff and Anglo-American Strategic Coordination in World War II.” Ph.D. dissertation, Brandeis University, 1996.

Submission and Readers

You should remember that theses are submitted to the Department of History and not only to your individual thesis adviser. The adviser is just one of the readers who will grade the thesis; the final evaluation of your work will be the product of deliberations between your adviser and a second reader (and in some instances, a third reader). Still, there should be no problem submitting an acceptable thesis as long as you work closely with your adviser throughout the year and respond to his/her guidance.

Each reader of your thesis will prepare written comments. Usually these take the form of a general evaluation of your work, but you may find that a reader has prepared more detailed comments about particular points of substance and style. Thesis comments and grades will be emailed to you upon receipt of your Personal Statement prior to and in preparation for the Senior Departmental Examination.

Useful Links

Independent Work in History Library Resources Academic Integrity Senior Calendar

Senior Thesis

During the senior year, each student writes a thesis. The senior thesis is expected to make an original (or otherwise distinctive) contribution to broader knowledge in the field in which the student is working. It is important that the thesis be situated explicitly in relation to existing published literature. The senior thesis must be judged satisfactory by two members of the faculty, at least one of whom must be a member of the Department of Politics.

It is common, but by no means required, for junior paper topics, especially in the spring term, to serve as starting points for a senior thesis topic. The Department encourages students to use the summer between junior and senior year for work on the senior thesis.

Your senior thesis may expand upon ideas that you explored in the JP. You may draw on and cite your own JP just like you would use other resources. In addition, you may re-use a limited portion of your JP in your senior thesis; for instance, the literature review could be re-used across the two. Whenever material from the JP is re-used, you must add a footnote noting the duplication across the JP or senior thesis. Note this policy does not affect the standard university guidelines for attributing ideas and research findings, whenever appropriate. The same policy holds with respect to incorporating the Fall junior research prospectus into either the Spring JP or senior thesis.

The length of a senior thesis is generally about 100 double-spaced pages and rarely under 80 pages. No thesis should be longer than 125 pages, including appendices. (This limit does not include the ancillary pages for the title, dedication, table of contents, abstract, bibliography and honor code statement.) Any pages after 125 may or may not be read by the second reader. A thesis longer than 125 pages will not be considered for Politics thesis prizes.

- Senior Thesis Project Planning Map and Timeline

- Research Advice

- Senior Thesis Funding

- Submission and Grading of Independent Work

Also, seniors are required to prepare and present a professional poster describing their senior thesis results.

| Advisors | Availability | Fields of Study | Areas of Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available | International Relations | International Security, Human Rights, International Justice, International Law | |

| Full | Comparative Politics | Regime Change, Political Parties, Political Mobilization, Democracy | |

| Available | International Relations | International Security, U.S. Foreign Policy, Civil Conflict, Migration, Political Psychology, Public Opinion, Statebuilding, Terrorism, Insurgency and Counterinsurgency | |

| Available | Comparative Politics, Political Economy | Empirical Democratic Theory, Political Economy, Political Institutions | |

| Available | American Politics | Judicial Politics, U.S. Presidency, Congress, Bureaucracy, National Policymaking, Political Economy | |

| Full | Political Theory | History of Political Thought, Democratic Theory, Representation, Freedom of Speech | |

| Full | Political Theory, Public Law | Philosophy of Law, Constitutional Interpretation, Civil Liberties, Moral and Political Philosophy, Bioethics, Law and Religion, Natural Law Theory | |

| Available | Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods, Political Economy | Political Economy, Game Theory, Networks, Information Transmission | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Gender and Politics, Development, Inequality, Political Economy of Development, Identity Politics, Political Representation, Ethnic Conflict, South Asia, Climate Change, Political Culture | |

| Available | American Politics | Political Communication, Social Media, Misinformation, Opinion Change, Experiments | |

| Available | American Politics, Comparative Politics, Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods, Political Economy | Political Economy, Institutions and Collective Decision-Making in Legislatures, Courts and Electorates | |

| Available | International Relations | International Relations Theory, U.S. Grand Strategy, International Organizations, International Order, Liberalism and International Relations | |

| Available | International Relations | Case Study Methods, Economic Power in Central and Eastern Europe, Russian Foreign Policy | |

| Full | Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods, Political Economy | Political Economy, Elections, Lobbying, Legislative Bargaining | |

| Available | International Relations | International Political Economy, Economic Development, U.S. Foreign Policy, Conflict | |

| Available | American Politics, Public Law | American Political Institutions, Judicial Politics, Supreme Court Nominations | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Comparative Politics, Bureaucracy, Development, Southeast Asian Politics | |

| Available | American Politics | Congress, Political Parties, Policymaking | |

| Available | International Relations, Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods | South America, Political Economy, Electoral Politics, Text as Data | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | International Security, Civil-Military Relations, Middle East and North Africa, Political Violence, Terrorism, Conflict, Democratization, Extremism | |

| Available | Political Theory | Citizenship and Civic Education, The Constitution, Marriage and Family, Immigration, Diversity, Civil Liberties, Free Speech and Hate Speech | |

| Full | American Politics | American Politics, Political Institutions, Political Polarization, Economic and Social Inequality, Political Economy of Financial Markets | |

| Available | American Politics, Race, Ethnicity and Identity | American Politics, Gender and Politics, Race, Ethnicity and Politics, American Political Development, Democratization, Social Movements and Protests, Policymaking, Social Identities, Federalism, State and Local Politics, Voting Rights, Political Decisionmaking | |

| Available | Comparative Politics, International Relations, Political Economy | International Political Economy, Comparative Political Economy, Globalization, The Resource Curse, Taxation, International Trade, Two-Level Bargaining Games, International Economic Cooperation, Taxation and Political Accountability | |

| Available | International Relations | European Union Politics, International Relations Theory, Transatlantic Relations, International Human Rights, Qualitative Methods, International Organizations, International Law, Foreign Policy, Far-Right Populism, Global Democracy | |

| Available | International Relations, Political Economy | International Political Economy, Globalization, International Finance, Labor and Employment, Multinational Corporations, Global Supply Chains, International Trade, Sovereign Debt | |

| Available | American Politics | Policing, Bureaucracy, Political Behavior, Quantitative Methods | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Comparative Politics, Middle East and North Africa, Political Psychology, Authoritarianism, Politics and Religion | |

| Available | Political Theory | Activism, Authority and Political Obligation, Civil Resistance, Social Norms, Political Theory, Social Change, Civil Disobedience | |

| Available | Political Theory | Political Theory, Theories of Justice, Democratic Theory, Nationalism, Multiculturalism, Language | |

| Full | International Relations, Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods, Political Economy | Violent Conflict, War, Strategy, Political Economy, Environmental Politics | |

| Available | International Relations | Conflict, Political Economy, Security, Development, Disinformation | |

| Available | Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods | Comparative Politics, Political Methodology, Text as Data, Machine Learning/AI, Political Institutions, Parliaments, British Politics | |

| Available | American Politics, Race, Ethnicity and Identity | Racial Attitudes, Public Opinion, Black Politics, Race, Ethnicity and Politics, Political Communication, Experimental Methods | |

| Available | Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods | Quantitative Methods, Political Methodology, Applied Statistics, Comparative Politics, Party Systems | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Chinese Politics, Authoritarianism, Repression, Human Rights | |

| Available | Comparative Politics, Political Economy | Comparative Politics, Political Economy, Politics and Religion, Judicial Politics, Latin American Politics | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Comparative Politics, Political Economy, Democratization, Democratic Backsliding | |

| Available | Comparative Politics, Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods, Political Economy | Political Economy, Elections, Democratization, Governance | |

| Available | American Politics, Race, Ethnicity and Identity | Race, Ethnicity and Politics, Racial Attitudes, American Politics, Political Behavior, Public Opinion, African American Politics | |

| Available | Comparative Politics | Public Management, State Capacity, International and Comparative Constitutional Law, Public Law, African Politics, Public Goods Provision, Politics of Reform, Disaster Response, Electoral Systems, U.S. Community Development Block Grant Program | |

| Available | American Politics | Interest Groups, Lobbying, American Political Institutions, Political Economy, Congress, Bureaucracy, Federalism | |

| Available | Formal Theory & Quantitative Methods | Causal Inference, Political Methodology, Political Institutions, Quantitative Methods, Comparative Politics, Chinese Politics, Political Economy of Development, Bureaucratic Organizations, Political Communication, Media and Politics |

The Senior Thesis

From the outset of their time at Princeton, students are encouraged and challenged to develop their scholarly interests and to evolve as independent thinkers.

The culmination of this process is the senior thesis, which provides a unique opportunity for students to pursue original research and scholarship in a field of their choosing. At Princeton, every senior writes a thesis or, in the case of some engineering departments, undertakes a substantial independent project.

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability to meet new challenges.

Many students develop projects from ideas sparked in the classes they’ve taken; others fashion their topics on the basis of long-standing personal passions. Most thesis writers encounter the intellectual twists and turns of any good research project, where the questions emerge as they proceed, often taking them in unexpected directions.

Planning for the senior thesis starts in earnest in the junior year, when students complete a significant research project known as the junior paper. Students who plan ahead can make good use of the University's considerable resources, such as receiving University funds to do research in the United States or abroad. Other students use summer internships as a launching pad for their thesis. For some science and engineering projects, students stay on campus the summer before their senior year to get a head start on lab work.

Writing a thesis encourages the self-confidence and high ambitions that come from mastering a difficult challenge. It fosters the development of specific skills and habits of mind that augur well for future success. No wonder generations of graduates look back on the senior thesis as the most valuable academic component of their Princeton experience.

Navigating Colombia’s Magdalena River, One Story At A Time