How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

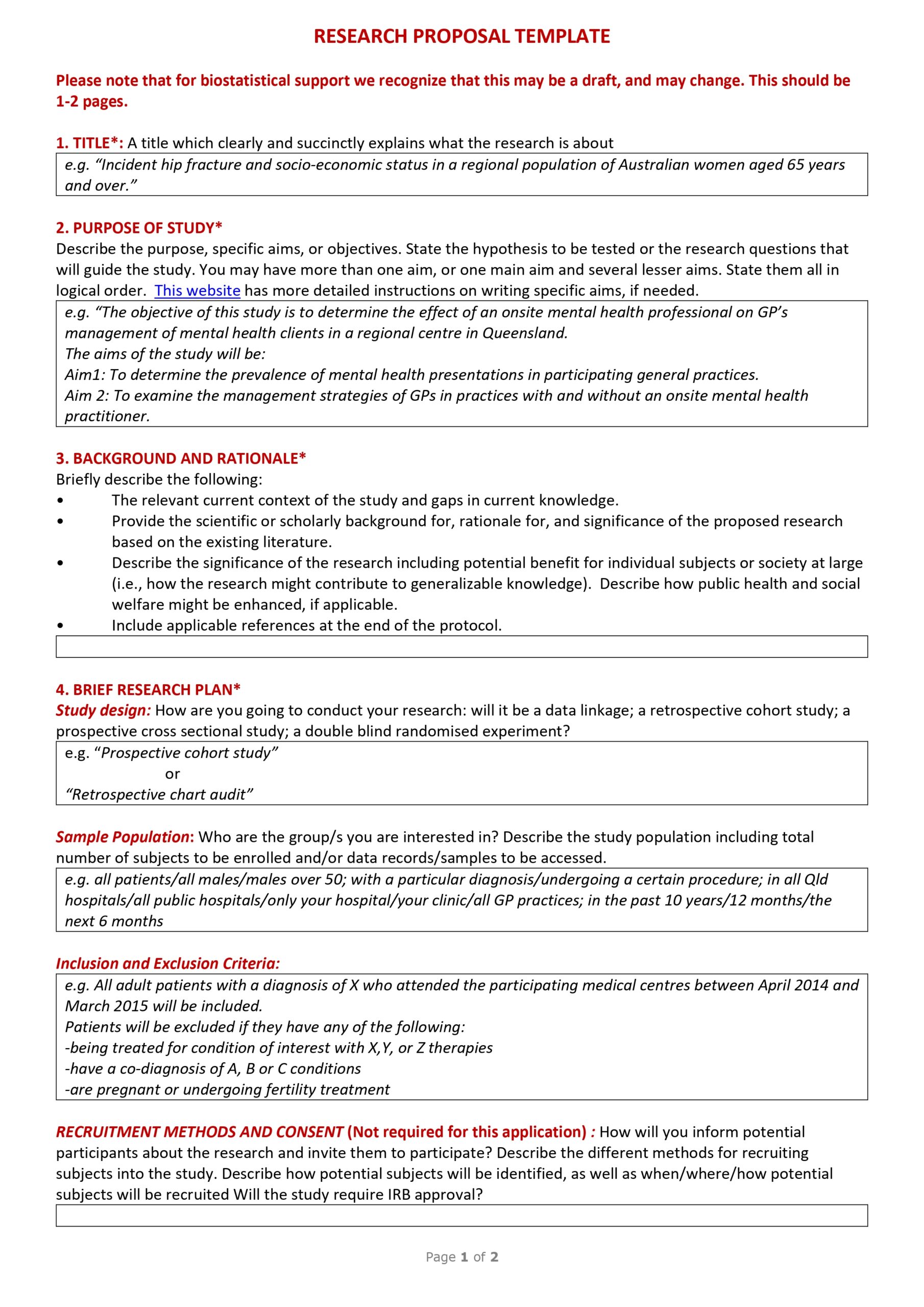

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Students & Educators —Menu

- Educational Resources

- Educators & Faculty

- College Planning

- ACS ChemClub

- Project SEED

- U.S. National Chemistry Olympiad

- Student Chapters

- ACS Meeting Information

- Undergraduate Research

- Internships, Summer Jobs & Coops

- Study Abroad Programs

- Finding a Mentor

- Two Year/Community College Students

- Social Distancing Socials

- Grants & Fellowships

- Career Planning

- International Students

- Planning for Graduate Work in Chemistry

- ACS Bridge Project

- Graduate Student Organizations (GSOs)

- Standards & Guidelines

- Explore Chemistry

- Science Outreach

- Publications

- ACS Student Communities

- LEADS Conference

- ChemMatters

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Students & Educators

Writing the Research Plan for Your Academic Job Application

By Jason G. Gillmore, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry, Hope College, Holland, MI

A research plan is more than a to-do list for this week in lab, or a manila folder full of ideas for maybe someday—at least if you are thinking of a tenure-track academic career in chemistry at virtually any bachelor’s or higher degree–granting institution in the country. A perusal of the academic job ads in C&EN every August–October will quickly reveal that most schools expect a cover letter (whether they say so or not), a CV, a teaching statement, and a research plan, along with reference letters and transcripts. So what is this document supposed to be, and why worry about it now when those job ads are still months away?

What Is a Research Plan?

A research plan is a thoughtful, compelling, well-written document that outlines your exciting, unique research ideas that you and your students will pursue over the next half decade or so to advance knowledge in your discipline and earn you grants, papers, speaking invitations, tenure, promotion, and a national reputation. It must be a document that people at the department you hope to join will (a) read, and (b) be suitably excited about to invite you for an interview.

That much I knew when I was asked to write this article. More specifics I only really knew for my own institution, Hope College (a research intensive undergraduate liberal arts college with no graduate program), and even there you might get a dozen nuanced opinions among my dozen colleagues. So I polled a broad cross-section of my network, spanning chemical subdisciplines at institutions ranging from small, teaching-centered liberal arts colleges to our nation’s elite research programs, such as Scripps and MIT. The responses certainly varied, but they did center on a few main themes, or illustrate a trend across institution types. In this article I’ll share those commonalities, while also encouraging you to be unafraid to contact a search committee chair with a few specific questions, especially for the institutions you are particularly excited about and feel might be the best fit for you.

How Many Projects Should You Have?

While more senior advisors and members of search committees may have gotten their jobs with a single research project, conventional wisdom these days is that you need two to three distinct but related projects. How closely related to one another they should be is a matter of debate, but almost everyone I asked felt that there should be some unifying technique, problem or theme to them. However, the projects should be sufficiently disparate that a failure of one key idea, strategy, or technique will not hamstring your other projects.

For this reason, many applicants wisely choose to identify:

- One project that is a safe bet—doable, fundable, publishable, good but not earthshaking science.

- A second project that is pie-in-the-sky with high risks and rewards.

- A third project that fits somewhere in the middle.

Having more than three projects is probably unrealistic. But even the safest project must be worth doing, and even the riskiest must appear to have a reasonable chance of working.

How Closely Connected Should Your Research Be with Your Past?

Your proposed research must do more than extend what you have already done. In most subdisciplines, you must be sufficiently removed from your postdoctoral or graduate work that you will not be lambasted for clinging to an advisor’s apron strings. After all, if it is such a good idea in their immediate area of interest, why aren’t they pursuing it?!?

But you also must be able to make the case for why your training makes this a good problem for you to study—how you bring a unique skill set as well as unique ideas to this research. The five years you will have to do, fund, and publish the research before crafting your tenure package will go by too fast for you to break into something entirely outside your realm of expertise.

Biochemistry is a partial exception to this advice—in this subdiscipline it is quite common to bring a project with you from a postdoc (or more rarely your Ph.D.) to start your independent career. However, you should still articulate your original contribution to, and unique angle on the work. It is also wise to be sure your advisor tells that same story in his or her letter and articulates support of your pursuing this research in your career as a genuinely independent scientist (and not merely someone who could be perceived as his or her latest "flunky" of a collaborator.)

Should You Discuss Potential Collaborators?

Regarding collaboration, tread lightly as a young scientist seeking or starting an independent career. Being someone with whom others can collaborate in the future is great. Relying on collaborators for the success of your projects is unwise. Be cautious about proposing to continue collaborations you already have (especially with past advisors) and about starting new ones where you might not be perceived as the lead PI. Also beware of presuming you can help advance the research of someone already in a department. Are they still there? Are they still doing that research? Do they actually want that help—or will they feel like you are criticizing or condescending to them, trying to scoop them, or seeking to ride their coattails? Some places will view collaboration very favorably, but the safest route is to cautiously float such ideas during interviews while presenting research plans that are exciting and achievable on your own.

How Do You Show Your Fit?

Some faculty advise tailoring every application packet document to every institution to which you apply, while others suggest tweaking only the cover letter. Certainly the cover letter is the document most suited to introducing yourself and making the case for how you are the perfect fit for the advertised position at that institution. So save your greatest degree of tailoring for your cover letter. It is nice if you can tweak a few sentences of other documents to highlight your fit to a specific school, so long as it is not contrived.

Now, if you are applying to widely different types of institutions, a few different sets of documents will certainly be necessary. The research plan that you target in the middle to get you a job at both Harvard University and Hope College will not get you an interview at either! There are different realities of resources, scope, scale, and timeline. Not that my colleagues and I at Hope cannot tackle research that is just as exciting as Harvard’s. However, we need to have enough of a niche or a unique angle both to endure the longer timeframe necessitated by smaller groups of undergraduate researchers and to ensure that we still stand out. Furthermore, we generally need to be able to do it with more limited resources. If you do not demonstrate that understanding, you will be dismissed out of hand. But at many large Ph.D. programs, any consideration of "niche" can be inferred as a lack of confidence or ambition.

Also, be aware that department Web pages (especially those several pages deep in the site, or maintained by individual faculty) can be woefully out-of-date. If something you are planning to say is contingent on something you read on their Web site, find a way to confirm it!

While the research plan is not the place to articulate start-up needs, you should consider instrumentation and other resources that will be necessary to get started, and where you will go for funding or resources down the road. This will come up in interviews, and hopefully you will eventually need these details to negotiate a start-up package.

Who Is Your Audience?

Your research plan should show the big picture clearly and excite a broad audience of chemists across your sub-discipline. At many educational institutions, everyone in the department will read the proposal critically, at least if you make the short list to interview. Even at departments that leave it all to a committee of the subdiscipline, subdisciplines can be broad and might even still have an outside member on the committee. And the committee needs to justify their actions to the department at large, as well as to deans, provosts, and others. So having at least the introduction and executive summaries of your projects comprehensible and compelling to those outside your discipline is highly advantageous.

Good science, written well, makes a good research plan. As you craft and refine your research plan, keep the following strategies, as well as your audience in mind:

- Begin the document with an abstract or executive summary that engages a broad audience and shows synergies among your projects. This should be one page or less, and you should probably write it last. This page is something you could manageably consider tailoring to each institution.

- Provide sufficient details and references to convince the experts you know your stuff and actually have a plan for what your group will be doing in the lab. Give details of first and key experiments, and backup plans or fallback positions for their riskiest aspects.

- Hook your readers with your own ideas fairly early in the document, then strike a balance between your own new ideas and the necessary well referenced background, precedents, and justification throughout. Propose a reasonable tentative timeline, if you can do so in no more than a paragraph or two, which shows how you envision spacing out the experiments within and among your projects. This may fit well into your executive summary

- Show how you will involve students (whether undergraduates, graduate students, an eventual postdoc or two, possibly even high schoolers if the school has that sort of outreach, depending on the institutions to which you are applying) and divide the projects among students.

- Highlight how your work will contribute to the education of these students. While this is especially important at schools with greater teaching missions, it can help set you apart even at research intensive institutions. After all, we all have to demonstrate “broader impacts” to our funding agencies!

- Include where you will pursue funding, as well as publication, if you can smoothly work it in. This is especially true if there is doubt about how you plan to target or "market" your research. Otherwise, it is appropriate to hold off until the interview to discuss this strategy.

So, How Long Should Your Research Plan Be?

Learn more on the Blog

Here is where the answers diverged the most and without a unifying trend across institutions. Bottom line, you need space to make your case, but even more, you need people to read what you write.

A single page abstract or executive summary of all your projects together provides you an opportunity to make the case for unifying themes yet distinct projects. It may also provide space to articulate a timeline. Indeed, many readers will only read this single page in each application, at least until winnowing down to a more manageable list of potential candidates. At the most elite institutions, there may be literally hundreds of applicants, scores of them entirely well-suited to the job.

While three to five pages per proposal was a common response (single spaced, in 11-point Arial or 12-point Times with one inch margins), including references (which should be accurate, appropriate, and current!), some of my busiest colleagues have said they will not read more than about three pages total. Only a few actually indicated they would read up to 12-15 pages for three projects. In my opinion, ten pages total for your research plans should be a fairly firm upper limit unless you are specifically told otherwise by a search committee, and then only if you have two to three distinct proposals.

Why Start Now?

Hopefully, this question has answered itself already! Your research plan needs to be a well thought out document that is an integrated part of applications tailored to each institution to which you apply. It must represent mature ideas that you have had time to refine through multiple revisions and a great deal of critical review from everyone you can get to read them. Moreover, you may need a few different sets of these, especially if you will be applying to a broad range of institutions. So add “write research plans” to this week’s to do list (and every week’s for the next few months) and start writing up the ideas in that manila folder into some genuine research plans. See which ones survive the process and rise to the top and you should be well prepared when the job ads begin to appear in C&EN in August!

Jason G. Gillmore , Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Chemistry at Hope College in Holland, MI. A native of New Jersey, he earned his B.S. (’96) and M.S. (’98) degrees in chemistry from Virginia Tech, and his Ph.D. (’03) in organic chemistry from the University of Rochester. After a short postdoctoral traineeship at Vanderbilt University, he joined the faculty at Hope in 2004. He has received the Dreyfus Start-up Award, Research Corporation Cottrell College Science Award, and NSF CAREER Award, and is currently on sabbatical as a Visiting Research Professor at Arizona State University. Professor Gillmore is the organizer of the Biennial Midwest Postdoc to PUI Professor (P3) Workshop co-sponsored by ACS, and a frequent panelist at the annual ACS Postdoc to Faculty (P2F) Workshops.

Other tips to help engage (or at least not turn off) your readers include:

- Avoid two-column formats.

- Avoid too-small fonts that hinder readability, especially as many will view the documents online rather than in print!

- Use good figures that are readable and broadly understandable!

- Use color as necessary but not gratuitously.

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="plan for future research"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Guide

How to Write a Research Plan

- Research plan definition

- Purpose of a research plan

- Research plan structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

Tips for creating a research plan

- Research plan examples

Research plan: definition and significance

What is the purpose of a research plan.

- Bridging gaps in the existing knowledge related to their subject.

- Reinforcing established research about their subject.

- Introducing insights that contribute to subject understanding.

Research plan structure & template

Introduction.

- What is the existing knowledge about the subject?

- What gaps remain unanswered?

- How will your research enrich understanding, practice, and policy?

Literature review

Expected results.

- Express how your research can challenge established theories in your field.

- Highlight how your work lays the groundwork for future research endeavors.

- Emphasize how your work can potentially address real-world problems.

5 Steps to crafting an effective research plan

Step 1: define the project purpose, step 2: select the research method, step 3: manage the task and timeline, step 4: write a summary, step 5: plan the result presentation.

- Brainstorm Collaboratively: Initiate a collective brainstorming session with peers or experts. Outline the essential questions that warrant exploration and answers within your research.

- Prioritize and Feasibility: Evaluate the list of questions and prioritize those that are achievable and important. Focus on questions that can realistically be addressed.

- Define Key Terminology: Define technical terms pertinent to your research, fostering a shared understanding. Ensure that terms like “church” or “unreached people group” are well-defined to prevent ambiguity.

- Organize your approach: Once well-acquainted with your institution’s regulations, organize each aspect of your research by these guidelines. Allocate appropriate word counts for different sections and components of your research paper.

Research plan example

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

FLEET LIBRARY | Research Guides

Rhode island school of design, create a research plan: research plan.

- Research Plan

- Literature Review

- Ulrich's Global Serials Directory

- Related Guides

A research plan is a framework that shows how you intend to approach your topic. The plan can take many forms: a written outline, a narrative, a visual/concept map or timeline. It's a document that will change and develop as you conduct your research. Components of a research plan

1. Research conceptualization - introduces your research question

2. Research methodology - describes your approach to the research question

3. Literature review, critical evaluation and synthesis - systematic approach to locating,

reviewing and evaluating the work (text, exhibitions, critiques, etc) relating to your topic

4. Communication - geared toward an intended audience, shows evidence of your inquiry

Research conceptualization refers to the ability to identify specific research questions, problems or opportunities that are worthy of inquiry. Research conceptualization also includes the skills and discipline that go beyond the initial moment of conception, and which enable the researcher to formulate and develop an idea into something researchable ( Newbury 373).

Research methodology refers to the knowledge and skills required to select and apply appropriate methods to carry through the research project ( Newbury 374) .

Method describes a single mode of proceeding; methodology describes the overall process.

Method - a way of doing anything especially according to a defined and regular plan; a mode of procedure in any activity

Methodology - the study of the direction and implications of empirical research, or the sustainability of techniques employed in it; a method or body of methods used in a particular field of study or activity *Browse a list of research methodology books or this guide on Art & Design Research

Literature Review, critical evaluation & synthesis

A literature review is a systematic approach to locating, reviewing, and evaluating the published work and work in progress of scholars, researchers, and practitioners on a given topic.

Critical evaluation and synthesis is the ability to handle (or process) existing sources. It includes knowledge of the sources of literature and contextual research field within which the person is working ( Newbury 373).

Literature reviews are done for many reasons and situations. Here's a short list:

| to learn about a field of study to understand current knowledge on a subject to formulate questions & identify a research problem to focus the purpose of one's research to contribute new knowledge to a field personal knowledge intellectual curiosity | to prepare for architectural program writing academic degrees grant applications proposal writing academic research planning funding |

Sources to consult while conducting a literature review:

Online catalogs of local, regional, national, and special libraries

meta-catalogs such as worldcat , Art Discovery Group , europeana , world digital library or RIBA

subject-specific online article databases (such as the Avery Index, JSTOR, Project Muse)

digital institutional repositories such as Digital Commons @RISD ; see Registry of Open Access Repositories

Open Access Resources recommended by RISD Research LIbrarians

works cited in scholarly books and articles

print bibliographies

the internet-locate major nonprofit, research institutes, museum, university, and government websites

search google scholar to locate grey literature & referenced citations

trade and scholarly publishers

fellow scholars and peers

Communication

Communication refers to the ability to

- structure a coherent line of inquiry

- communicate your findings to your intended audience

- make skilled use of visual material to express ideas for presentations, writing, and the creation of exhibitions ( Newbury 374)

Research plan framework: Newbury, Darren. "Research Training in the Creative Arts and Design." The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts . Ed. Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. New York: Routledge, 2010. 368-87. Print.

About the author

Except where otherwise noted, this guide is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution license

source document

Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2024 1:29 AM

- URL: https://risd.libguides.com/researchplan

- RIT Libraries

- Future Foresight and Planning Resources

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Electronic Books

- Print Books

- Interlibrary Loan This link opens in a new window

- Google Scholar Library Links

- Journals & Websites

- Citation Management Tool

- Digital Institutional Repository

- ProQuest Research Companion

- Literature Review

- Writing a Literature Review

- Thesis Submission Instructions

Writing a Rsearch Proposal

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research. Your paper should include the topic, research question and hypothesis, methods, predictions, and results (if not actual, then projected).

Research Proposal Aims

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Literature review

Reference list While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take. Proposal FormatThe proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

Introduction The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.. Your introduction should:

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own. In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

Research design and methods Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions. Write up your projected, if not actual, results. Contribution to knowledge To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters. For example, your results might have implications for:

Lastly, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use free APA citation generators like BibGuru. Databases have a citation button you can click on to see your citation. Sometimes you have to re-format it as the citations may have mistakes.

Edit this Guide Log into Dashboard Use of RIT resources is reserved for current RIT students, faculty and staff for academic and teaching purposes only. Please contact your librarian with any questions. Help is Available Email a LibrarianA librarian is available by e-mail at [email protected] Meet with a LibrarianCall reference desk voicemail. A librarian is available by phone at (585) 475-2563 or on Skype at llll Or, call (585) 475-2563 to leave a voicemail with the reference desk during normal business hours . Chat with a LibrarianFuture foresight and planning resources infoguide url. https://infoguides.rit.edu/ffp Use the box below to email yourself a link to this guide

career-advice.jobs.ac.uk Making A Five Year Research Plan Many academics will be asked by their institutions to produce a research plan that will take them up to the date of the next REF-style audit. In this exercise universities want their researchers to conduct ‘blue skies’ thinking that will fulfil their institutional strategic needs. However, scholars have their own agendas too. Here’s some advice on how to make your five-year research plan work for you. Thinking backwards:Preparing a five-year plan is a good opportunity for you to tie up loose ends. Doing your PhD you will have come across numerous avenues of research that did not make the final draft. So you will probably have several half-started projects or ideas that have a lot of potential. You might now be able to schedule time to complete these projects. If they are worthwhile to the development of your discipline, enhancing your own scholarly identity and furthering your career, then they are definitely worth pursuing. Thinking forwards:This is also an exciting opportunity to plan and develop new projects. It is vital to think big and to show your current employers or any future employers that you can deliver significant research projects. However, be realistic. Take into account the teaching commitments that will distract you from research and the competitive nature of funding and publication opportunities. Planning ahead – career and research:Using this method of five-year planning, you can tie your research profile to your developing career. Do you want to move to another institution or gain promotion in your current one? If so, think of ways in which your research plan can improve your chances of doing just that. Undertaking an audit of your progress so far and your future plans is a perfect activity for the new year! Institutional needs:Your university (and future employers) will want to see that you’ve thought about three major areas: internationalisation, third stream income and impact . They may also have their own particular areas of focus that you can refer to. Your research mentor will want to see that any projects are realistically costed. Do not just imagine what you want to research but how you will pay for it. If you suggest a piece of research that can be accomplished without teaching relief, practical resources, or travel costs then you can complete it when you like, but some funding will be required for most projects. Try to achieve a balance between internal funding from your institution and external funding from other sources. Collaborations:You don’t always have to design, undertake and complete a research project alone. Scientists are much better at collaborative work than their humanities counterparts. Not only can collaborations be personally rewarding through developing connections and even friendships with like-minded individuals, but also much larger projects can be considered. When thinking of your research plans, focus on the output that you will produce. This might be a traditional publication, a monograph, edited collection or journal, but could be something different such as a documentary, a museum exhibition, a website, a series of public lectures or a database. These outputs can be tied to the strategic agenda of your university, and to your career development ambitions. What did you think of our article? - please rate Share this article Reader InteractionsYou may also like:, leave a reply cancel reply. Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Please enter an answer in digits: 14 + 19 = This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .  Illustration by James Round How to plan a research projectWhether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery. by Brooke Harrington + BIO is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages. Edited by Sam Haselby Need to know‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question. Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work. What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis. At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question. Step 1: Orient yourself Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read. Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims? In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later. Step 2: Define your research question Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations. Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face. In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues. Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic. Step 3: Review previous research In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute. Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research: