SAFETY ALERT: If you are in danger, please use a safer computer and consider calling 911. The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 / TTY 1-800-787-3224 or the StrongHearts Native Helpline at 1−844-762-8483 (call or text) are available to assist you.

Please review these safety tips .

Research & Evidence

NRCDV works to strengthen researcher/practitioner collaborations that advance the field’s knowledge of, access to, and input in research that informs policy and practice at all levels. We also identify and develop guidance and tools to help domestic violence programs and coalitions better evaluate their work, including by using participatory action research approaches that directly tap the diverse expertise of a community to frame and guide evaluation efforts.

Safety & Privacy in a Digital World

Immigrant Survivors of Domestic Violence

Teen Dating Violence

Housing and Domestic Violence

Domestic Violence in LGBTQ Communities

Trans and Non-Binary Survivors

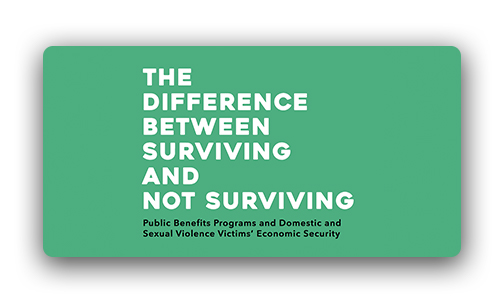

The Difference Between Surviving & Not Surviving

Earned Income Tax Credit & Other Tax Credits

For an extensive list of research & evidence materials check out the research & statistics section on VAWnet

The Domestic Violence Evidence Project (DVEP) is a multi-faceted, multi-year and highly collaborative effort designed to assist state coalitions, local domestic violence programs, researchers, and other allied individuals and organizations better respond to the growing emphasis on identifying and integrating evidence-based practice into their work. DVEP brings together research, evaluation, practice and theory to inform critical thinking and enhance the field's knowledge to better serve survivors and their families.

The Community Based Participatory Research Toolkit (CBPR) is for researchers and practitioners across disciplines and social locations who are working in academic, policy, community, or practice-based settings. In particular, the toolkit provides support to emerging researchers as they consider whether and how to take a CBPR approach and what it might mean in the context of their professional roles and settings. Domestic violence advocates will also find useful information on the CBPR approach and how it can help answer important questions about your work.

For over two decades, the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence has operated VAWnet , an online library focused on violence against women and other forms of gender-based violence. VAWnet.org has long been identified as an unparalleled, comprehensive, go-to source of information and resources for anti-violence advocates, human service professionals, educators, faith leaders, and others interested in ending domestic and sexual violence.

Safe Housing Partnerships , the website of the Domestic Violence and Housing Technical Assistance Consortium , includes the latest research and evidence on the intersection of domestic and sexual violence, housing, and homelessness. You can also find new research exploring different aspects of efforts to expand housing options for domestic and sexual violence survivors, including the use of flexible funding approaches, DV Housing First and rapid rehousing, DV Transitional Housing, and mobile advocacy.

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics * Domestic Violence Video Presentations * Online CEU Courses

From the Editorial Board of the Peer-Reviewed Journal, Partner Abuse www.springerpub.com/pa and the Advisory Board of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Programs www.battererintervention.org * www.domesticviolenceintervention.net

Resources for researchers, policy-makers, intervention providers, victim advocates, law enforcement, judges, attorneys, family court mediators, educators, and anyone interested in family violence

PASK FINDINGS

61-Page Author Overview

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics at-a-Glance

PASK Researchers

PASK Video Summary by John Hamel, LCSW

- Introduction

- Implications for Policy and Treatment

- Domestic Violence Politics

17 Full PASK Manuscripts and tables of Summarized Studies

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH

THE PARTNER ABUSE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE PROJECT

The world's largest domestic violence research data base, 2,657 pages, with summaries of 1700 peer-reviewed studies.

Courtesy of the scholarly journal, Partner Abuse www.springerpub.com/pa and the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Providers www.domesticviolenceintervention.net

MAJOR UPDATE COMING, JANUARY, 2025!

Over the years, research on partner abuse has become unnecessarily fragmented and politicized. The purpose of The Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project (PASK) is to bring together in a rigorously evidence-based, transparent and methodical manner existing knowledge about partner abuse with reliable, up-to-date research that can easily be accessed both by researchers and the general public.

Family violence scholars from the United States, Canada and the U.K. were invited to conduct an extensive and thorough review of the empirical literature, in 17 broad topic areas. They were asked to conduct a formal search for published, peer-reviewed studies through standard, widely used search programs, and then catalogue and summarize all known research studies relevant to each major topic and its sub-topics. In the interest of thoroughness and transparency, the researchers agreed to summarize all quantitative studies published in peer-reviewed journals after 1990, as well as any major studies published prior to that time, and to clearly specify exclusion criteria. Included studies are organized in extended tables, each table containing summaries of studies relevant to its particular sub-topic.

In this unprecedented undertaking, a total of 42 scholars and 70 research assistants at 20 universities and research institutions spent two years or more researching their topics and writing the results. Approximately 12,000 studies were considered and more than 1,700 were summarized and organized into tables. The 17 manuscripts, which provide a review of findings on each of the topics, for a total of 2,657 pages, appear in 5 consecutive special issues of the peer-reviewed journal Partner Abuse . All conclusions, including the extent to which the research evidence supports or undermines current theories, are based strictly on the data collected.

Contact: [email protected]

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE TRAININGS

Online CEU Courses - Click Here for More Information

Also see VIDEOS and ADDITIONAL RESEARCH sections below.

Other domestic violence trainings are available at: www.domesticviolenceintervention.net , courtesy of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Providers (ADVIP)

Click here for video presentations from the 6-hour ADVIP 2020 International Conference on evidence-based treatment.

NISVS: The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey

Click here for all reports

CLASSIC VIDEO PRESENTATIONS Murray Straus, Ph.D. * Erin Pizzey * Don Dutton, Ph.D. Click Here

Video: the uncomfortable facts on ipv, tonia nicholls, ph.d., video: batterer intervention groups: moving forward with evidence-based practice, john hamel, ph.d., additional research.

From Other Renowned Scholars and Clinicians. Click on any name below for research, trainings and expert witness/consultation services

PREVALENCE RATES

Arthur Cantos, Ph.D. University of Texas

Denise Hines, Ph.D. Clark University

Zeev Winstok, Ph.D. University of Haifa (Israel)

CONTEXT OF ABUSE

Don Dutton, Ph.D University of British Columbia (Canada)

K. Daniel O'Leary State University of New York at Stony Brook

Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Ph.D. University of South Alabama

ABUSE WORLDWIDE ETHNIC/LGBT GROUPS

Fred Buttell, Ph.D. Tulane University

Clare Cannon, Ph.D. University of California, Davis

Vallerie Coleman, Ph.D. Private Practice, Santa Monica, CA

Chiara Sabina, Ph.D. Penn State Harrisburg

Esteban Eugenio Santovena, Ph.D. Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

Christauria Welland, Ph.D. Private Practice, San Diego, CA

RISK FACTORS

Louise Dixon, Ph.D. University of Birmingham (U.K.)

Sandra Stith, Ph.D. Kansas State University

Gregory Stuart, Ph.D. University of Tennessee Knoxville

IMPACT ON VICTIMS AND FAMILIES

Deborah Capaldi, Ph.D. Oregon Social Learning Center

Patrick Davies, Ph.D. University of Rochester

Miriam Ehrensaft, Ph.D. Columbia University Medical Ctr.

Amy Slep, Ph.D. State University of New York at Stony Brook

VICTIM ISSUES

Carol Crabsen, MSW Valley Oasis, Lancaster, CA

Emily Douglas, Ph.D. Bridgewater State University

Leila Dutton, Ph.D. University of New Haven

Margaux Helm WEAVE, Sacramento, CA

Linda Mills, Ph.D. New York University

Brenda Russell, Ph.D. Penn State Berks

CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESPONSES

Ken Corvo, Ph.D. Syracuse University

Jeffrey Fagan, Ph.D. Columbia University

Brenda Russell, Ph.D, Penn State Berks

Stan Shernock, Ph.D. Norwich University

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Julia Babcock, Ph.D. University of Houston

Fred Buttell, Ph.D.Tulane University

Michelle Carney, Ph.D. University of Georgia

Christopher Eckhardt, Ph.D. Purdue Univerity

Kimberly Flemke, Ph.D. Drexel University

Nicola Graham-Kevan, Ph.D. Univ. Central Lancashire (U.K.)

Peter Lehmann, Ph.D. University of Texas at Arlingon

Penny Leisring, Ph.D. Quinnipiac University

Christopher Murphy, Ph.D. University of Maryland

Ronald Potter-Efron, Ph.D. Private Practice, Eleva, WI

Daniel Sonkin, Ph.D. Private Practice, Sausalito, CA.

Lynn Stewart, Ph.D. Correctional Service, Canada

Casey Taft, Ph.D Boston University School of Medicine

Jeff Temple, Ph.D. University of Texas Medical Branch

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Gender, Sex and Sexualities

- Research Topics

New Perspectives on Domestic Violence: from Research to Intervention

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

In a document dated June 16th 2017, the United States Department of Justice stated that Domestic Violence (DV) has a significant impact not only on those abused, but also on family members, friends, and on the people within the social networks of both the abuser and the victim. In this sense, children who ...

Keywords : domestic violence, intimate partner violence, victims, perpetrators, societal attitudes, gender violence, intervention and prevention, relevant research, same sex intimate partner violence, same sex domestic violence

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

- About The Journalist’s Resource

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Domestic violence and abusive relationships: Research review

Research review of data and studies relating to intimate partner violence and abusive relationships.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource August 17, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/domestic-violence-abusive-relationships-research-review/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The controversy over NFL star Ray Rice and the instance of domestic violence he perpetrated, which was caught on video camera, stirred wide discussion about sports culture, domestic violence and even the psychology of victims and their complex responses to abuse . In 2015, domestic violence drew a national spotlight again when the South Carolina newspaper, the Post and Courier , won a Pulitzer Prize for its investigation of women who were abused by men and had been dying at a rate of one every 12 days.

The research on domestic violence, referred to more precisely in academic literature as “intimate partner violence” (IPV), has grown substantially over the past few decades. Although knowledge of the problem and its scope have deepened, the issue remains a major health and social problem afflicting women. In November 2014 the World Health Organization estimated that 35% of all women have experienced either intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner during their lifetimes. This figure is supported by the findings of a 2013 peer-reviewed metastudy — the most rigorous form of research analysis — published in the leading academic journal Science . That metastudy found that “in 2010, 30.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 27.8 to 32.2%] of women aged 15 and over have experienced, during their lifetime, physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence.” The prevalence found among high-income regions in North America was 21.3%. Of course, under-reporting remains a substantial problem in this research area.

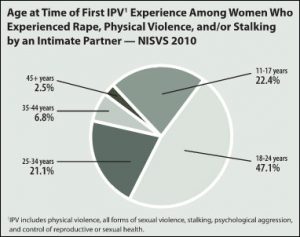

In 2010, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that “more than 1 in 3 women (35.6%) … in the United States have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.” That survey was subsequently updated in September 2014. The findings, based on telephone surveys with more than 12,000 people in 2011, include:

The lifetime prevalence of physical violence by an intimate partner was an estimated 31.5% among women and in the 12 months before taking the survey, an estimated 4.0% of women experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner. An estimated 22.3% of women experienced at least one act of severe physical violence by an intimate partner during their lifetimes. With respect to individual severe physical violence behaviors, being slammed against something was experienced by an estimated 15.4% of women, and being hit with a fist or something hard was experienced by 13.2% of women. In the 12 months before taking the survey, an estimated 2.3% of women experienced at least one form of severe physical violence by an intimate partner.

Still, the overall rates of IPV in the United States have been generally falling over the past two decades, and in 2013 the federal government reauthorized an enhanced Violence Against Women Act , adding further legal protections and broadening the groups covered to include LGBT persons and Native American women. (For research on the relatively higher violence rates among gay men, see the 2012 study “Intimate Partner Violence and Social Pressure among Gay Men in Six Countries.” )

A 2013 study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family , “Women’s Education, Marital Violence, and Divorce: A Social Exchange Perspective,” analyzes a nationally representative sample of more than 900 young U.S. women to look at factors that make females more likely to leave abusive relationships. The researchers, Derek A. Kreager, Richard B. Felson, Cody Warner and Marin R. Wenger, are all at Pennsylvania State University. They note that traditional “social exchange theory” would suggest that as women have more resources, they become less dependent on men and have more opportunities outside relationships, and therefore have more ability to divorce. The study sets out to “determine whether the relationship between a woman’s education and divorce is different in violent marriages.” The researchers also hypothesize that women who have higher levels of education are less likely to get divorced in general — prior academic work they cite supports this — but they aim to see how the introduction of intimate partner violence changes this dynamic.

The study’s findings include:

- The data provide “support for our primary hypotheses that women’s education typically protects against divorce but that this association weakens in abusive marriages. In addition, we found a similar pattern for wives’ proportional income, net of education. Together, these patterns suggest that educational and financial resources benefit women by increasing marital stability in nonabusive marriages and promoting divorce in abusive marriages.”

- Further, the “greater tendency for educated women to leave abusive marriages was substantial. For example, in highly violent marriages, women with a college degree had over a 10% greater probability of divorce in the observed time period than women without a college degree.”

- The study also finds that “women with economic resources were likely to leave unhappy marriages, regardless of whether they involve abuse. Similarly, degree-earning women were more likely than less educated women to leave violent marriages, regardless of their feelings of dissatisfaction.”

The researchers note that, across the U.S. population, more women are attaining college degrees, and given the study’s findings, this suggests “increases in women’s education should reduce rates of domestic violence. In a population with many educated women, violent marriages are likely to break up.” They caution that it is also possible “that our observed patterns reflect husbands’ perceptions and decisions. Perhaps abusive men feel threatened by successful wives, which then increases divorce risk. Nonabusive men may not feel threatened and thus stay with successful women.” On this point, more research is required.

Related research: A 2015 study titled “When War Comes Home: The Effect of Combat Service on Domestic Violence” suggests that multiple deployments and longer deployment lengths may increase the chance of family violence. A June 2014 study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence , “Intimate Partner Violence Before and During Pregnancy: Related Demographic and Psychosocial Factors and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms Among Mexican American Women,” provides a snapshot of domestic violence in a community sample of low-income Hispanic women. A March 2013 report from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994-2010,” provides a broad picture of such crimes across American society, examining the demographics of both victims and offenders. Regarding the issue of IPV prevention, a 2003 metastudy published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) , “Interventions for Violence Against Women: Scientific Review,” found that “information about evidence-based approaches in the primary care setting for preventing IPV is seriously lacking…. Specifically, the effectiveness of routine primary care screening remains unclear, since screening studies have not evaluated outcomes beyond the ability of the screening test to identify abused women. Similarly, specific treatment interventions for women exposed to violence, including women’s shelters, have not been adequately evaluated.” Subsequent research continues to find problems with current techniques for screening and detection.

Tags: gender, women and work, crime, sex crimes

About The Author

John Wihbey

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women

- Mina Shayestefar 1 ,

- Mohadese Saffari 1 ,

- Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh 2 ,

- Monir Nobahar 3 , 4 ,

- Majid Mirmohammadkhani 4 ,

- Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh 5 &

- Zahra Khosravi 6

BMC Women's Health volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication. Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan.

This study was conducted as mixed research (cross-sectional descriptive and phenomenological qualitative methods) to investigate domestic violence against women, and some related factors (quantitative) and experiences of such violence (qualitative) simultaneously in Semnan. In quantitative study, cluster sampling was conducted based on the areas covered by health centers from married women living in Semnan since March 2021 to March 2022 using Domestic Violence Questionnaire. Then, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics. In qualitative study by phenomenological approach and purposive sampling until data saturation, 9 women were selected who had referred to the counseling units of Semnan health centers due to domestic violence, since March 2021 to March 2022 and in-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The conducted interviews were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step method.

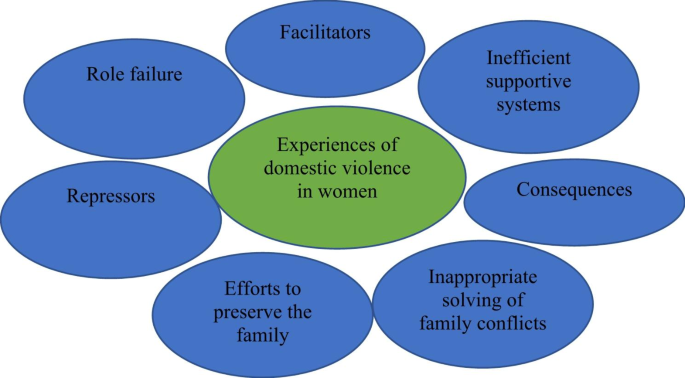

In qualitative study, seven themes were found including “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems”. In quantitative study, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage had a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of the number of children had a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). Also, increasing the level of female education and income both independently showed a significant relationship with increasing the score of violence.

Conclusions

Some of the variables of violence against women are known and the need for prevention and plans to take action before their occurrence is well felt. Also, supportive mechanisms with objective and taboo-breaking results should be implemented to minimize harm to women, and their children and families seriously.

Peer Review reports

Violence against women by husbands (physical, sexual and psychological violence) is one of the basic problems of public health and violation of women’s human rights. It is estimated that 35% of women and almost one out of every three women aged 15–49 experience physical or sexual violence by their spouse or non-spouse sexual violence in their lifetime [ 1 ]. This is a nationwide public health issue, and nearly every healthcare worker will encounter a patient who has suffered from some type of domestic or family violence. Unfortunately, different forms of family violence are often interconnected. The “cycle of abuse” frequently persists from children who witness it to their adult relationships, and ultimately to the care of the elderly [ 2 ]. This violence includes a range of physical, sexual and psychological actions, control, threats, aggression, abuse, and rape [ 3 ].

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent, and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication [ 3 ]. In the United States of America, more than one in three women (35.6%) experience rape, physical violence, and intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime. Compared to men, women are nearly twice as likely (13.8% vs. 24.3%) to experience severe physical violence such as choking, burns, and threats with knives or guns [ 4 ]. The higher prevalence of violence against women can be due to the situational deprivation of women in patriarchal societies [ 5 ]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran reported 22.9%. The maximum of prevalence estimated in Tehran and Zahedan, respectively [ 6 ]. Currently, Iran has high levels of violence against women, and the provinces with the highest rates of unemployment and poverty also have the highest levels of violence against women [ 7 ].

Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society [ 8 ]. Violence against women leads to physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, including threats, coercion and arbitrary deprivation of their freedom in public and private life. Also, such violence is associated with harmful effects on women’s sexual reproductive health, including sexually transmitted infection such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), abortion, unsafe childbirth, and risky sexual behaviors [ 9 ]. There are high levels of psychological, sexual and physical domestic abuse among pregnant women [ 10 ]. Also, women with postpartum depression are significantly more likely to experience domestic violence during pregnancy [ 11 ].

Prompt attention to women’s health and rights at all levels is necessary, which reduces this problem and its risk factors [ 12 ]. Because women prefer to remain silent about domestic violence and there is a need to introduce immediate prevention programs to end domestic violence [ 13 ]. violence against women, which is an important public health problem, and concerns about human rights require careful study and the application of appropriate policies [ 14 ]. Also, the efforts to change the circumstances in which women face domestic violence remain significantly insufficient [ 15 ]. Given that few clear studies on violence against women and at the same time interviews with these people regarding their life experiences are available, the authors attempted to planning this research aims to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan with the research question of “What is the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Semnan, and what are their experiences of such violence?”, so that their results can be used in part of the future planning in the health system of the society.

This study is a combination of cross-sectional and phenomenology studies in order to investigate the amount of domestic violence against women and some related factors (quantitative) and their experience of this violence (qualitative) simultaneously in the Semnan city. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethic code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182. The researcher introduced herself to the research participants, explained the purpose of the study, and then obtained informed written consent. It was assured to the research units that the collected information will be anonymous and kept confidential. The participants were informed that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, so they can withdraw from the study at any time with confidence. The participants were notified that more than one interview session may be necessary. To increase the trustworthiness of the study, Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [ 16 ], were applied throughout the research process. The COREQ checklist was used to assess the present study quality. The researchers used observational notes for reflexivity and it preserved in all phases of this qualitative research process.

Qualitative method

Based on the phenomenological approach and with the purposeful sampling method, nine women who had referred to the counseling units of healthcare centers in Semnan city due to domestic violence in February 2021 to March 2022 were participated in the present study. The inclusion criteria for the study included marriage, a history of visiting a health center consultant due to domestic violence, and consent to participate in the study and unwillingness to participate in the study was the exclusion criteria. Each participant invited to the study by a telephone conversation about study aims and researcher information. The interviews place selected through agreement of the participant and the researcher and a place with the least environmental disturbance. Before starting each interview, the informed consent and all of the ethical considerations, including the purpose of the research, voluntary participation, confidentiality of the information were completely explained and they were asked to sign the written consent form. The participants were interviewed by depth, semi-structured and face-to-face interviews based on the main research question. Interviews were conducted by a female health services researcher with a background in nursing (M.Sh.). Data collection was continued until the data saturation and no new data appeared. Only the participants and the researcher were present during the interviews. All interviews were recorded by a MP3 Player by permission of the participants before starting. Interviews were not repeated. No additional field notes were taken during or after the interview.

The age range of the participants was from 38 to 55 years and their average age was 40 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in table below (Table 1 ).

Five interviews in the courtyards of healthcare centers, 2 interviews in the park, and 2 interviews at the participants’ homes were conducted. The duration of the interviews varied from 45 min to one hour. The main research question was “What is your experience about domestic violence?“. According to the research progress some other questions were asked in line with the main question of the research.

The conducted interviews were analyzed by using the 7 steps Colizzi’s method [ 17 ]. In order to empathize with the participants, each interview was read several times and transcribed. Then two researchers (M.Sh. and M.N.) extracted the phrases that were directly related to the phenomenon of domestic violence against women independently and distinguished from other sentences by underlining them. Then these codes were organized into thematic clusters and the formulated concepts were sorted into specific thematic categories.

In the final stage, in order to make the data reliable, the researcher again referred to 2 participants and checked their agreement with their perceptions of the content. Also, possible important contents were discussed and clarified, and in this way, agreement and approval of the samples was obtained.

Quantitative method

The cross-sectional study was implemented from February 2021 to March 2022 with cluster sampling of married women in areas of 3 healthcare centers in Semnan city. Those participants who were married and agreed with the written and verbal informed consent about the ethical considerations were included to the study. The questionnaire was completed by the participants in paper and online form.

The instrument was the standard questionnaire of domestic violence against women by Mohseni Tabrizi et al. [ 18 ]. In the questionnaire, questions 1–10, 11–36, 37–65 and 66–71 related to sociodemographic information, types of spousal abuse (psychological, economical, physical and sexual violence), patriarchal beliefs and traditions and family upbringing and learning violence, respectively. In total, this questionnaire has 71 items.

The scoring of the questionnaire has two parts and the answers to them are based on the Likert scale. Questions 11–36 and 66–71 are answered with always [ 4 ] to never (0) and questions 37–65 with completely agree [ 4 ] to completely disagree (0). The minimum and maximum score is 0 and 300, respectively. The total score of 0–60, 61–120 and higher than 121 demonstrates low, moderate and severe domestic violence against women, respectively [ 18 ].

In the study by Tabrizi et al., to evaluate the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, researchers tried to measure the face validity of the scale by the previous research. Those items and questions which their accuracies were confirmed by social science professors and experts used in the research, finally. The total Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.183, which confirmed that the reliability of the questions and items of the questionnaire is sufficient [ 18 ].

Descriptive data were reported using mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage. Then, to measure the relationship between the variables, χ2 and Pearson tests also variance and regression analysis were performed. All analysis were performed by using SPSS version 26 and the significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Qualitative results

According to the third step of Colaizzi’s 7-step method, the researcher attempted to conceptualize and formulate the extracted meanings. In this step, the primary codes were extracted from the important sentences related to the phenomenon of violence against women, which were marked by underlining, which are shown below as examples of this stage and coding.

The primary code of indifference to the father’s role was extracted from the following sentences. This is indifference in the role of the father in front of the children.

“Some time ago, I told him that our daughter is single-sided deaf. She has a doctor’s appointment; I have to take her to the doctor. He said that I don’t have money to give you. He doesn’t force himself to make money anyway” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“He didn’t value his own children. He didn’t think about his older children” (p 4, 54 yrs).

The primary code extracted here included lack of commitment in the role of head of the household. This is irresponsibility towards the family and meeting their needs.

“My husband was fired from work after 10 years due to disorder and laziness. Since then, he has not found a suitable job. Every time he went to work, he was fired after a month because of laziness” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“In the evening, he used to get dressed and go out, and he didn’t come back until late. Some nights, I was so afraid of being alone that I put a knife under my pillow when I slept” (p 2, 33 yrs).

A total of 246 primary codes were extracted from the interviews in the third step. In the fourth step, the researchers put the formulated concepts (primary codes) into 85 specific sub-categories.

Twenty-three categories were extracted from 85 sub-categories. In the sixth step, the concepts of the fifth step were integrated and formed seven themes (Table 2 ).

These themes included “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems” (Fig. 1 ).

Themes of domestic violence against women

Some of the statements of the participants on the theme of “ Facilitators” are listed below:

Husband’s criminal record

“He got his death sentence for drugs. But, at last it was ended for 10 years” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Inappropriate age for marriage

“At the age of thirteen, I married a boy who was 25 years old” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My first husband obeyed her parents. I was 12–13 years old” (p 3, 32 yrs).

“I couldn’t do anything. I was humiliated” (p 1, 38 yrs).

“A bridegroom came. The mother was against. She said, I am young. My older sister is not married yet, but I was eager to get married. I don’t know, maybe my father’s house was boring for me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“My parents used to argue badly. They blamed each other and I always wanted to run away from these arguments. I didn’t have the patience to talk to mom or dad and calm them down” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Overdependence

“My husband’s parents don’t stop interfering, but my husband doesn’t say anything because he is a student of his father. My husband is self-employed and works with his father on a truck” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“Every time I argue with my husband because of lack of money, my mother-in-law supported her son and brought him up very spoiled and lazy” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Bitter memories

“After three years, my mother married her friend with my uncle’s insistence and went to Shiraz. But, his condition was that she did not have the right to bring his daughter with her. In fact, my mother also got married out of necessity” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Some of their other statements related to “ Role failure” are mentioned below:

Lack of commitment to different roles

“I got angry several times and went to my father’s house because of my husband’s bad financial status and the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible to work and always says that he cannot find a job” (p 6, 48 yrs).

“I saw that he does not want to change in any way” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“No matter how kind I am, it does not work” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Repressors” are listed below:

Fear and silence

“My mother always forced me to continue living with my husband. Finally, my father had been poor. She all said that you didn’t listen to me when you wanted to get married, so you don’t have the right to get angry and come to me, I’m miserable enough” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“Because I suffered a lot in my first marital life. I was very humiliated. I said I would be fine with that. To be kind” (p1, 38 yrs).

“Well, I tell myself that he gets angry sometimes” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Shame from society

“I don’t want my daughter-in-law to know. She is not a relative” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Some of the statements of the participants regarding the theme of “ Efforts to preserve the family” are listed below:

Hope and trust

“I always hope in God and I am patient” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Efforts for children

“My divorce took a month. We got a divorce. I forgave my dowry and took my children instead” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Inappropriate solving of family conflicts” are listed below:

Child-bearing thoughts

“My husband wanted to take me to a doctor to treat me. But my father-in-law refused and said that instead of doing this and spending money, marry again. Marriage in the clans was much easier than any other work” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Lack of effective communication

“I was nervous about him, but I didn’t say anything” (p 5, 39 yrs).

“Now I am satisfied with my life and thank God it is better to listen to people’s words. Now there is someone above me so that people don’t talk behind me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Consequences” are listed below:

Harm to children

“My eldest daughter, who was about 7–8 years old, behaved differently. Oh, I was angry. My children are mentally depressed and argue” (p 5, 39 yrs).

After divorce

“Even though I got a divorce, my mother and I came to a remote area due to the fear of what my family would say” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Social harm

“I work at a retirement center for living expenses” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“I had to go to clean the houses” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Non-acceptance in the family

“The children’s relationship with their father became bad. Because every time they saw their father sitting at home smoking, they got angry” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Emotional harm

“When I look back, I regret why I was not careful in my choice” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“I felt very bad. For being married to a man who is not bound by the family and is capricious” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Inefficient supportive systems” are listed below:

Inappropriate family support

“We didn’t have children. I was at my father’s house for about a month. After a month, when I came home, I saw that my husband had married again. I cried a lot that day. He said, God, I had to. I love you. My heart is broken, I have no one to share my words” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My brother-in-law was like himself. His parents had also died. His sister did not listen at all” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“I didn’t have anyone and I was alone” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Inefficiency of social systems

“That day he argued with me, picked me up and threw me down some stairs in the middle of the yard. He came closer, sat on my stomach, grabbed my neck with both of his hands and wanted to strangle me. Until a long time later, I had kidney problems and my neck was bruised by her hand. Given that my aunt and her family were with us in a building, but she had no desire to testify and was afraid” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Undesired training and advice

“I told my mother, you just said no, how old I was? You never insisted on me and you didn’t listen to me that this man is not good for you” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Quantitative results

In the present study, 376 married women living in Semnan city participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 38.52 ± 10.38 years. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 73 years old. The maximum age difference was 16 years. The years of marriage varied from one year to 40 years. Also, the number of children varied from no children to 7. The majority of them had 2 children (109, 29%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in the table below (Table 3 ).

The frequency distribution (number and percentage) of the participants in terms of the level of violence was as follows. 89 participants (23.7%) had experienced low violence, 59 participants (15.7%) had experienced moderate violence, and 228 participants (60.6%) had experienced severe violence.

Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.988. The mean and standard deviation of the total score of the questionnaire was 143.60 ± 74.70 with a range of 3-244. The relationship between the total score of the questionnaire and its fields, and some demographic variables is summarized in the table below (Table 4 ).

As shown in the table above, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage have a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of number of children has a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). However, the variable of education level difference showed no significant relationship with the total score and any of the fields. Also, the highest average score is related to patriarchal beliefs compared to other fields.

The comparison of the average total scores separately according to each variable showed the significant average difference in the variables of the previous marriage history of the woman, the result of the previous marriage of the woman, the education of the woman, the education of the man, the income of the woman, the income of the man, and the physical disease of the man (p < 0.05).

In the regression model, two variables remained in the final model, indicating the relationship between the variables and violence score and the importance of these two variables. An increase in women’s education and income level both independently show a significant relationship with an increase in violence score (Table 5 ).

The results of analysis of variance to compare the scores of each field of violence in the subgroups of the participants also showed that the experience and result of the woman’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with physical violence and tradition and family upbringing, the experience of the man’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with patriarchal belief, the education level of the woman has a significant relationship with all fields and the level of education of the man has a significant relationship with all fields except tradition and family upbringing (p < 0.05).

According to the results of both quantitative and qualitative studies, variables such as the young age of the woman and a large age difference are very important factors leading to an increase in violence. At a younger age, girls are afraid of the stigma of society and family, and being forced to remain silent can lead to an increase in domestic violence. As Gandhi et al. (2021) stated in their study in the same field, a lower marriage age leads to many vulnerabilities in women. Early marriage is a global problem associated with a wide range of health and social consequences, including violence for adolescent girls and women [ 12 ]. Also, Ahmadi et al. (2017) found similar findings, reporting a significant association among IPV and women age ≤ 40 years [ 19 ].

Two others categories of “Facilitators” in the present study were “Husband’s criminal record” and “Overdependence” which had a sub-category of “Forced cohabitation”. Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported in their population-based study in Iran that husband’s addiction and rented-householders have a significant association with IPV [ 19 ].

The patriarchal beliefs, which are rooted in the tradition and culture of society and family upbringing, scored the highest in relation to domestic violence in this study. On the other hand, in qualitative study, “Normalcy” of men’s anger and harassment of women in society is one of the “Repressors” of women to express violence. In the quantitative study, the increase in the women’s education and income level were predictors of the increase in violence. Although domestic violence is more common in some sections of society, women with a wide range of ages, different levels of education, and at different levels of society face this problem, most of which are not reported. Bukuluki et al. (2021) showed that women who agreed that it is good for a man to control his partner were more likely to experience physical violence [ 20 ].

Domestic violence leads to “Consequences” such as “Harm to children”, “Emotional harm”, “Social harm” to women and even “Non-acceptance in their own family”. Because divorce is a taboo in Iranian culture and the fear of humiliating women forces them to remain silent against domestic violence. Balsarkar (2021) stated that the fear of violence can prevent women from continuing their studies, working or exercising their political rights [ 8 ]. Also, Walker-Descarte et al. (2021) recognized domestic violence as a type of child maltreatment, and these abusive behaviors are associated with mental and physical health consequences [ 21 ].

On the other hand and based on the “Lack of effective communication” category, ignoring the role of the counselor in solving family conflicts and challenges in the life of couples in the present study was expressed by women with reasons such as lack of knowledge and family resistance to counseling. Several pathologies are needed to investigate increased domestic violence in situations such as during women’s pregnancy or infertility. Because the use of counseling for couples as a suitable solution should be considered along with their life challenges. Lin et al. (2022) stated that pregnant women were exposed to domestic violence for low birth weight in full term delivery. Spouse violence screening in the perinatal health care system should be considered important, especially for women who have had full-term low birth weight infants [ 22 ].

Also, lack of knowledge and low level of education have been found as other factors of violence in this study, which is very prominent in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Because the social systems and information about the existing laws should be followed properly in society to act as a deterrent. Psychological training and especially anger control and resilience skills during education at a younger age for girls and boys should be included in educational materials to determine the positive results in society in the long term. Manouchehri et al. (2022) stated that it seems necessary to train men about the negative impact of domestic violence on the current and future status of the family [ 23 ]. Balsarkar (2021) also stated that men and women who have not had the opportunity to question gender roles, attitudes and beliefs cannot change such things. Women who are unaware of their rights cannot claim. Governments and organizations cannot adequately address these issues without access to standards, guidelines and tools [ 8 ]. Machado et al. (2021) also stated that gender socialization reinforces gender inequalities and affects the behavior of men and women. So, highlighting this problem in different fields, especially in primary health care services, is a way to prevent IPV against women [ 24 ].

There was a sub-category of “Inefficiency of social systems” in the participants experiences. Perhaps the reason for this is due to insufficient education and knowledge, or fear of seeking help. Holmes et al. (2022) suggested the importance of ascertaining strategies to improve victims’ experiences with the court, especially when victims’ requests are not met, to increase future engagement with the system [ 25 ]. Sigurdsson (2019) revealed that despite high prevalence numbers, IPV is still a hidden and underdiagnosed problem and neither general practitioner nor our communities are as well prepared as they should be [ 26 ]. Moreira and Pinto da Costa (2021) found that while victims of domestic violence often agree with mandatory reporting, various concerns are still expressed by both victims and healthcare professionals that require further attention and resolution [ 27 ]. It appears that legal and ethical issues in this regard require comprehensive evaluation from the perspectives of victims, their families, healthcare workers, and legal experts. By doing so, better practical solutions can be found to address domestic violence, leading to a downward trend in its occurrence.

Some of the variables of violence against women have been identified and emphasized in many studies, highlighting the necessity of policymaking and social pathology in society to prevent and use operational plans to take action before their occurrence. Breaking the taboo of domestic violence and promoting divorce as a viable solution after counseling to receive objective results should be implemented seriously to minimize harm to women, children, and their families.

Limitations

Domestic violence against women is an important issue in Iranian society that women resist showing and expressing, making researchers take a long-term process of sampling in both qualitative and quantitative studies. The location of the interview and the women’s fear of their husbands finding out about their participation in this study have been other challenges of the researchers, which, of course, they attempted to minimize by fully respecting ethical considerations. Despite the researchers’ efforts, their personal and professional experiences, as well as the studies reviewed in the literature review section, may have influenced the study results.

Data Availability

Data and materials will be available upon email to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Intimate Partner Violence

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Organization WH. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization; 2021.

Huecker MR, Malik A, King KC, Smock W. Kentucky Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ahmad Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Kevin King declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: William Smock declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

Gandhi A, Bhojani P, Balkawade N, Goswami S, Kotecha Munde B, Chugh A. Analysis of survey on violence against women and early marriage: Gyneaecologists’ perspective. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71(Suppl 2):76–83.

Article Google Scholar

Sugg N. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, health consequences, and intervention. Med Clin. 2015;99(3):629–49.

Google Scholar

Abebe Abate B, Admassu Wossen B, Tilahun Degfie T. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):1–8.

Adineh H, Almasi Z, Rad M, Zareban I, Moghaddam A. Prevalence of domestic violence against women in Iran: a systematic review. Epidemiol (Sunnyvale). 2016;6(276):2161–11651000276.

Pirnia B, Pirnia F, Pirnia K. Honour killings and violence against women in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):e60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Balsarkar G. Summary of four recent studies on violence against women which obstetrician and gynaecologists should know. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71:64–7.

Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. The lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72.

Chasweka R, Chimwaza A, Maluwa A. Isn’t pregnancy supposed to be a joyful time? A cross-sectional study on the types of domestic violence women experience during pregnancy in Malawi. Malawi Med journal: J Med Association Malawi. 2018;30(3):191–6.

Afshari P, Tadayon M, Abedi P, Yazdizadeh S. Prevalence and related factors of postpartum depression among reproductive aged women in Ahvaz. Iran Health care women Int. 2020;41(3):255–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reproductive health. 2017;14:1–10.

Duran S, Eraslan ST. Violence against women: affecting factors and coping methods for women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(1):53–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mahapatro M, Kumar A. Domestic violence, women’s health, and the sustainable development goals: integrating global targets, India’s national policies, and local responses. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(2):298–309.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: sage; 1985.

Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978.

Mohseni Tabrizi A, Kaldi A, Javadianzadeh M. The study of domestic violence in Marrid Women Addmitted to Yazd Legal Medicine Organization and Welfare Organization. Tolooebehdasht. 2013;11(3):11–24.

Ahmadi R, Soleimani R, Jalali MM, Yousefnezhad A, Roshandel Rad M, Eskandari A. Association of intimate partner violence with sociodemographic factors in married women: a population-based study in Iran. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):834–44.

Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, Musuya T, Letiyo E, Bazira D. An examination of physical violence against women and its justification in development settings in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0255281.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walker-Descartes I, Mineo M, Condado LV, Agrawal N. Domestic violence and its Effects on Women, Children, and families. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(2):455–64.

Lin C-H, Lin W-S, Chang H-Y, Wu S-I. Domestic violence against pregnant women is a potential risk factor for low birthweight in full-term neonates: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12):e0279469.

Manouchehri E, Ghavami V, Larki M, Saeidi M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Domestic violence experienced by women with multiple sclerosis: a study from the North-East of Iran. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–14.

Machado DF, Castanheira ERL, Almeida MASd. Intersections between gender socialization and violence against women by the intimate partner. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2021;26:5003–12.

Holmes SC, Maxwell CD, Cattaneo LB, Bellucci BA, Sullivan TP. Criminal Protection orders among women victims of intimate Partner violence: Women’s Experiences of Court decisions, processes, and their willingness to Engage with the system in the future. J interpers Violence. 2022;37(17–18):Np16253–np76.

Sigurdsson EL. Domestic violence-are we up to the task? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(2):143–4.

Moreira DN, Pinto da Costa M. Should domestic violence be or not a public crime? J Public Health. 2021;43(4):833–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study appreciate the Deputy for Research and Technology of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Social Determinants of Health Research Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences and all the participants in this study.

Research deputy of Semnan University of Medical Sciences financially supported this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Mina Shayestefar & Mohadese Saffari

Amir Al Momenin Hospital, Social Security Organization, Ahvaz, Iran

Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar & Majid Mirmohammadkhani

Clinical Research Development Unit, Kowsar Educational, Research and Therapeutic Hospital, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh

Student Research Committee, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Zahra Khosravi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.Sh. contributed to the first conception and design of this research; M.Sh., Z.Kh., M.S., R.Gh. and S.H.Sh. contributed to collect data; M.N. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the qualitative data; M.M. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the quantitative data; M.SH., M.N. and M.M. contributed to the interpretation of the data; M.Sh., M.S. and S.H.Sh. wrote the manuscript. M.Sh. prepared the final version of manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript meticulously and approved it. All names of the authors were listed in the title page.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mina Shayestefar .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This article is resulted from a research approved by the Vice Chancellor for Research of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethics code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182 in the Social Determinants of Health Research Center. The authors confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants accepted the participation in the present study. The researchers introduced themselves to the research units, explained the purpose of the research to them and then all participants signed the written informed consent. The research units were assured that the collected information was anonymous. The participant was informed that participating in the study was completely voluntary so that they can safely withdraw from the study at any time and also the availability of results upon their request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shayestefar, M., Saffari, M., Gholamhosseinzadeh, R. et al. A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women. BMC Women's Health 23 , 322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2023

Accepted : 14 June 2023

Published : 20 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Cross-sectional studies

- Qualitative research

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Domestic Violence Statistics 2024

Author: Milena J. Wisniewska | Last updated: August 29, 2024 Fact-checked | Cite this webpage

Report highlights. In the United States, nearly every 1 in 2 women and more than 2 in 5 men reported experiencing intimate partner violence at some point in their lifetime.

Here are some critical facts:

- Nearly every 1 in 2 women in the United States is going to face physical violence from an intimate partner at some point in their lives. [ 1 ]

- More than 16 million people in the U.S. suffer from intimate partner abuse per year. [ 2 ]

- Every minute 32 people experience intimate partner violence in the United States. [ 3 ]

- 1 in 4 men in the United States has endured severe physical violence from an intimate partner. [ 4 ]

- Over 47% of women have encountered contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime. [ 5 ]

How Many Women Experience Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence continues to profoundly affect the lives of countless women across the United States, remaining a persistent and critical issue.

According to a series of reports from the 2016/2017 data years of the National Intimate Partner Violence Survey (NISVS):

- Nearly every 1 in 2 women in the United States will face physical violence from an intimate partner at some point in their lives. [ 6 ]

- Almost 1 in 5 women in the United States reported any contact sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 7 ]

- Slightly more than 2 in 5 women in the United States reported experiencing any physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 8 ]

- Almost 40 million women reported being slapped, pushed, or shoved. [ 9 ]

- Almost half of all women reported any psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 10 ]

How Common Is Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence is alarmingly common in the United States, affecting millions of individuals each year. NISVS reports:

- More than 16 million people in the U.S. suffer from intimate partner abuse per year. [ 11 ]

- Every minute 32 people experience intimate partner violence in the United States. [ 12 ]

- Nearly every 1 in 2 women and more than 2 in 5 men reported experiencing intimate partner violence at some point in their lifetime. [ 13 ]

What Percentage of Domestic Violence Victims Are Female?

Data leaves no doubt: Domestic violence predominantly impacts women. According to a report published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) in 2009:

- 85% of domestic violence victims are women. [ 14 ]

How Many Women Die From Domestic Violence?

- Around 75% of fatal victims of domestic violence are women. [ 15 ]

- In 2007, 24% of female homicide victims were killed by a spouse or ex-spouse. [ 16 ]

- By 2019, nearly 4 women were murdered daily by intimate partners. [ 17 ]

Domestic Violence Rates Over Time

Domestic violence statistics over the years paint a grim picture, revealing the persistent and escalating nature of the issue:

- In 2000, a U.S. Department of Justice report indicated that 1.3% of women and 0.9% of men experienced domestic violence in the past year. [ 18 ]

- By 2019, nearly 4 women were murdered daily by intimate partners, reflecting an increase since 2014 after decades of decline. [ 19 ]

- Each year, about 2.3 million people are raped or physically assaulted by a current or former partner. [ 20 ]

- Victimization rates vary by race, with White and Black women more frequently victims of beatings than Asian or Hispanic women. [ 21 ]

Domestic Violence Statistics From the CDC

- Nearly every 1 in 2 women in the United States will face physical violence from an intimate partner at some point in their lives. [ 22 ]

- Almost 1 in 5 women in the United States reported any contact sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 23 ]

- Slightly more than 2 in 5 women in the United States reported experiencing any physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 24 ]

- Almost 40 million women reported being slapped, pushed, or shoved. [ 25 ]

- Almost half of all women reported any psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. [ 26 ]

- More than 16 million people in the U.S. suffer from intimate partner abuse per year. [ 27 ]

- Every minute, 32 people experience intimate partner violence in the United States (based on annualized report results). [ 28 ]

- 1 in 4 men in the United States has endured severe physical violence from an intimate partner. [ 29 ]

- Over 47% of women have encountered contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime. [ 30 ]

- Leemis, R. W., Friar, N., Khatiwada, S., Chen, M. S., Kresnow, M., Smith, S. G., Caslin, S., & Basile, K. C. (2022). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2016/2017 report on intimate partner violence . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nisvs/documentation/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf ↩︎

- Catalano, S., Smith, E., Snyder, H., & Rand, M. (2009). Female victims of violence (NCJ 228356). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvv.pdf ↩︎

- Catalano, S., Smith, E., Snyder, H., & Rand, M. (2009). Female victims of violence (NCJ 228356). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pd ↩︎

- Fridel, E. E., & Fox, J. A. (2019). Gender differences in patterns and trends in US homicide, 1976–2017. Violence and Gender, 6 (1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2019.0005 ↩︎

- Tjaden, P. G. (2000). Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey . US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice. https://books.google.com/books/download/Full_Report_of_the_Prevalence_Incidence.pdf?id=1ErTLeIq8ccC&output=pdf ↩︎

- The Violence Against Women Act of 2005, Summary of Provisions. 42 U.S.C. §§ 13925–14045d. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/3402 ↩︎

- Stockman, J. K., Hayashi, H., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women [Corrected]. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt), 24 (1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4879 ↩︎

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Employing Research To Understand Violence Against Women

Fifty years ago, violence against women, and domestic violence in particular, was not considered a criminal justice concern in this country. It was largely viewed as a personal matter, best dealt with privately within families.

With a sweeping reinvestment in criminal justice reform in the 1960s, the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and efforts in the late 1980s and 1990s that led to passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, violence against women entered the public consciousness in the United States. It began to be recognized as a serious public health and public safety problem that warranted criminal justice system intervention.

Over the past 50 years, NIJ has established and expanded a strong program that addresses violence against women. Its portfolio has funded more than $130 million in research on intimate partner violence, sexual violence, stalking, teen dating violence, and other related topics. NIJ-funded initiatives have also helped finance the testing of previously unsubmitted sexual assault kits and establish best practices in testing these kits.

Kristina Rose, a former NIJ acting director who worked on violence against women issues throughout her 19 years with the U.S. Department of Justice, summed up NIJ’s influence: “When it comes to violence against women, NIJ has been brave and pioneering across the spectrum of issues to help people understand what we know about violence against women, including what the criminal justice response should look like.”

Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment

In the wake of national attention surrounding violence against women in the 1970s and early 1980s, NIJ funded a randomized controlled trial experiment in Minneapolis that examined various law enforcement responses to domestic violence. [1] In 1984, the results of the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment indicated that spending a night in jail significantly reduced the risk that a person would commit a future act of domestic violence. As a result, many police departments across the country implemented pro-arrest or mandatory arrest policies in domestic violence situations.

Given the findings and the implications for law enforcement, NIJ funded six replication studies, beginning in 1986. These studies showed contradictory results, which underscored the importance of replicating research studies. Replication ensures that results are valid, reliable, and generalizable.

Although replications found mixed results, the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment marked a significant change in how law enforcement approached intimate partner violence.

“This was the first time there was a shift in how the criminal justice system thought about and responded to domestic violence,” says Angela Moore, senior science advisor and social scientist at NIJ.

Nearly 40 years later, the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment is still frequently cited as a pivotal study.

The Violence Against Women Act

The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) of 1994 was landmark legislation that created legal protections for victims of domestic and sexual violence and established funding streams for responding to these crimes. Filling critical resource gaps in every state, VAWA grant programs support law enforcement agencies, prosecutors’ offices, courts, domestic violence shelters, and rape crisis centers in serving victims and holding persons who commit violent acts against women accountable. VAWA also expanded the scope and scale of U.S. research on violence against women and led to a significant expansion of NIJ’s major research and evaluation efforts in the field.

“VAWA was an impetus,” says Moore. “We did some work on violence against women before the Act, but the funding NIJ received as a result of VAWA helped us spring forward and gave rise to the program we have today.”

VAWA was reauthorized in 2000, 2005, and 2013, and separate legislation in 2002 established the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW), a Department of Justice agency responsible for leading the implementation of VAWA grant programs.

“Thanks to funding administered by OVW, communities have developed coordinated responses to crimes of violence against women,” says OVW Acting Director Katharine Sullivan. “Justice system professionals, victim services providers, and other community partners have used these grants to work together to ensure that victims get the help they need and that dangerous persons are stopped from committing more crimes. These coordinated community responses have transformed how domestic violence is treated in the criminal and civil justice systems and sparked innovative prevention efforts like Maryland’s Lethality Assessment Program to reduce domestic violence homicides.”

In 1998, NIJ began receiving designated VAWA funds for research on violence against women. Funding allocations varied by year — ranging from $7 million in 1998 to $1.88 million in 2008 and 2009 — with a current allocation of $3 million to $5 million each fiscal year. This steady stream of funds from OVW has helped NIJ study the nature and scope of violence against women and the effectiveness of strategies for combatting these crimes. Knowledge generated through NIJ’s Violence Against Women program informs efforts within the Department of Justice and in communities across the nation to protect victims and bring those who commit violent acts against women to justice.

Collecting Representative Data

Despite the considerable number of studies on violence against women that were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, there remained a critical need to understand the magnitude and nature of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking in a way that would provide accurate and reliable data. Surveys that frame questions within the context of crime do not necessarily provide representative data on respondents’ experiences with violence against women, in part because people do not always self-identify as victims of crime.

To address this research gap, in 2000 NIJ partnered with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS). [2] The survey revealed that more than half of the surveyed women reported being physically assaulted at some point in their lives, and nearly two-thirds of women who reported being raped, physically assaulted, or stalked were victimized by intimate partners.

For two reasons, this survey has been consistently cited as a more reliable representation of rates of violence against women than surveys that frame victimization within the context of crime. First, the NVAWS did not rely solely on reported offenses because the vast majority of crimes go unreported. Second, the survey was designed to ask detailed, behavior-specific questions about respondents’ victimization experiences. By asking questions that avoid legal terms (for example, “rape”) and instead asking about a suspect’s specific behaviors (for example, “slapped,” “pushed,” and “shoved”), the survey avoided attributing blame or labeling respondents as victims.

The NVAWS was one of many NIJ-CDC collaborations to address violence against women. As a result, NIJ was able to bring a public health perspective to its work, alongside its inherent focus on public safety. NIJ again collaborated with CDC, as well as the U.S. Department of Defense Family Advocacy Program, to develop the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS); the first survey report was produced in 2011. [3] CDC continues to administer the NISVS to capture data about violence against women and men, and the survey has become one of the most frequently cited data sets in the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data.

Research After VAWA

VAWA mandated that the Department of Justice work in partnership with the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to develop a research agenda for violence against women. The 1996 NAS report Understanding Violence Against Women was instrumental in shaping the direction of NIJ’s violence against women research portfolio. Subsequent NAS reports, along with strategic planning workshops and other input, have also informed program goals and direction.

Intimate Partner Violence

Through grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts supported by VAWA funding, NIJ has supported more than 200 studies on intimate partner violence — accounting for nearly half of the agency’s total funding allocations for violence against women research since 1993. Over this period, rates of intimate partner homicides have dropped nearly 30 percent as public awareness of intimate partner violence and policy responses have grown. [4] In 2016, NIJ hosted a meeting with prominent researchers and criminal justice practitioners to inform the Institute’s research agenda moving forward.