- Feature Article

- Developmental Biology

Meta-Research: The need for more research into reproductive health and disease

- Natalie D Mercuri

- Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Canada ;

- Open access

- Copyright information

- Comment Open annotations (there are currently 0 annotations on this page).

- 2,512 views

- 164 downloads

- 5 citations

Share this article

Cite this article.

- Brian J Cox

- Copy to clipboard

- Download BibTeX

- Download .RIS

- Figures and data

Introduction

Conclusions, data availability, decision letter, author response, article and author information.

Reproductive diseases have a significant impact on human health, especially on women’s health: endometriosis affects 10% of all reproductive-aged women but is often undiagnosed for many years, and preeclampsia claims over 70,000 maternal and 500,000 neonatal lives every year. Infertility rates are also rising. However, relatively few new treatments or diagnostics for reproductive diseases have emerged in recent decades. Here, based on analyses of PubMed, we report that the number of research articles published on non-reproductive organs is 4.5 times higher than the number published on reproductive organs. Moreover, for the two most-researched reproductive organs (breast and prostate), the focus is on non-reproductive diseases such as cancer. Further, analyses of grant databases maintained by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Institutes of Health in the United States show that the number of grants for research on non-reproductive organs is 6–7 times higher than the number for reproductive organs. Our results suggest that there are too few researchers working in the field of reproductive health and disease, and that funders, educators and the research community must take action to combat this longstanding disregard for reproductive science.

It is difficult to overstate the impact of reproductive disease. Adverse pregnancy outcomes – which include preterm delivery, low birth weight, hypertensive disorders, and gestational diabetes –impact the acute and chronic health of the population ( Barker, 1997 ; Williams, 2011 ; Lewis et al., 2012 ). About 20% of all pregnancies require medical intervention ( Murray and Lopez, 1998 ), and in lower resource settings, pregnancy and delivery complications are a leading cause of maternal and neonatal death ( WHO, 2019 ).

In 1992, the Institute of Medicine in the United States published a report called Strengthening Research in Academic OB-GYN Departments that outlined areas of research with obstetrics and gynecology where improvements were needed, such as low-birth-weight infants, fertility complications, and pregnancy-induced hypertension ( Institute of Medicine, 1992 ). Three decades later, despite the essential nature and impact of the reproductive system, these issues are still major challenges in reproductive health.

Gender inequality and bias have been issues since the onset of biological and medical research. For example, including women as subjects in clinical research was not standard practice until after 1986 ( Liu and Mager, 2016 ). There has been progress in developing policies to increase the representation of women (as both subjects and researchers) and in providing education on gender inequality for all researchers, but women are still underrepresented in scientific and medical research ( Huang et al., 2020 ).

There are a variety of stigmas and taboos surrounding any topic relating to reproductive function. Menstruation is one function that has faced stigmatization that persists today ( Litman, 2018 ; Pickering, 2019 ), with women often feeling too embarrassed to talk about this natural process or even complete an essential task, such as purchasing menstrual products at a local store. Political power highly affects reproductive health care and rights over other biological processes. In many countries, ongoing political and legal battles directly affect access to safe reproductive health care, including contraception, safe abortion, and gender identity rights ( Pugh, 2019 ). There are parallels between the low level of research into reproductive diseases and the response to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. The long delay in recognizing AIDS as a significant health issue, and then implementing research policies, perpetuated false ideas surrounding the lifestyles of those affected by the disease and created a barrier to expanding sexual education and seeking healthcare, likely costing many lives ( Francis, 2012 ). Despite great advances in AIDS research and treatment, including social awareness, public health stigma still lingers in society ( Turan et al., 2017 ). Similar increases in advocacy and public awareness are needed to overcome these barriers affecting reproductive health.

Reproductive pathologies are often challenging to diagnose and properly treat, which increases the risk of comorbidity development. Moreover, a long-standing lack of research into reproductive health and disease means that the acute and chronic healthcare burden caused by reproductive pathologies is likely to continue increasing. This lack of research likely results from historic and ongoing systemic biases against female-focused research, and from political and legal challenges to female reproductive health ( Coen-Sanchez et al., 2022 ). In this exploratory analysis we seek to understand the “research gap” between reproductive health and disease and other areas of medical research, and to suggest ways of closing this gap.

Comparing numbers of publications

To benchmark research on reproductive health and disease, we used the PubMed database to compare the number of articles published on seven reproductive organs and seven non-reproductive organs between 1966 and 2021 ( Table 1 ). While the reproductive organs are not essential to postnatal life, we posit that the placenta and the uterus are as essential to fetal survival in utero as the lungs and the heart are to postnatal survival after birth. Our analysis revealed that the average number of articles on non-reproductive organs was 4.5 times higher than the number on reproductive organs (and ranged between about 2 and 20 in pairwise comparisons). The reproductive organs with the most publications were the breast and prostate.

Total number of matching articles from PubMed for seven non-reproductive keywords and seven reproductive keywords for the period 1966–2021.

| Keyword | Total matching articles |

|---|---|

| Non-reproductive keywords | |

| 1,058,995 | |

| 851,955 | |

| 834,006 | |

| 652,797 | |

| 451,177 | |

| 120,034 | |

| 99,772 | |

| Reproductive keywords | |

| 464,629 | |

| 197,736 | |

| 83,971 | |

| 57,076 | |

| 55,971 | |

| 32,344 | |

| 15,019 | |

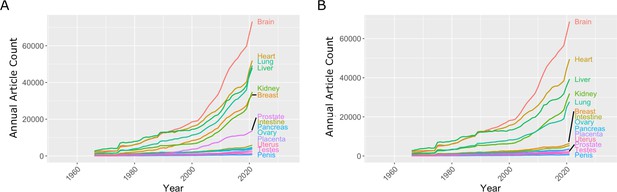

The research landscape can change over time and efforts to reduce gender bias in research might have had an impact on the volume of reproductive research, so we plotted the number of publications on the 14 organs as a function year between 1966 and 2021 ( Figure 1A ). Breast and prostate were the only reproductive organs to increase in publication at a rate similar to the kidney; the second least studied non-reproductive organ in our list. The intestine was the only non-reproductive organ to show similar publication rates to the other five reproductive organs. To investigate further, we compared disease-driven research versus research not related to disease.

Number of articles published every year on seven reproductive organs and seven non-reproductive organs.

( A ) The number of articles published on most of the non-reproductive organs (including the brain, heart, lung and liver) has increased more rapidly than the number of articles published on the reproductive organs. ( B ) Removing articles that contain the keyword cancer has relatively little effect on the number of articles for non-reproductive organs (with the exception of the lung), but has a significant impact on the number of articles for the two reproductive organs with the most articles: the breast and prostate. Data extracted from PubMed using organ-specific keyword searches for the period 1966–2021.

Figure 1—source data 1

Articles per year for reproductive and non-reproductive organs, with and without the keyword cancer.

Comparing research related to disease and research not related to disease

In the 1970s, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiated a war on cancer, and the breast and prostate are both associated with sex-specific cancers. We reassessed publication data with the added search parameter "NOT cancer" to eliminate cancer-based research ( Figure 1B ). We observed a reduction of approximately 20% for most non-reproductive organs; however, the reduction for publication on the breast and prostate was about 80%, suggesting that most research on these organs is driven by an interest in cancer research rather than reproductive health and disease ( Figure 1B ).

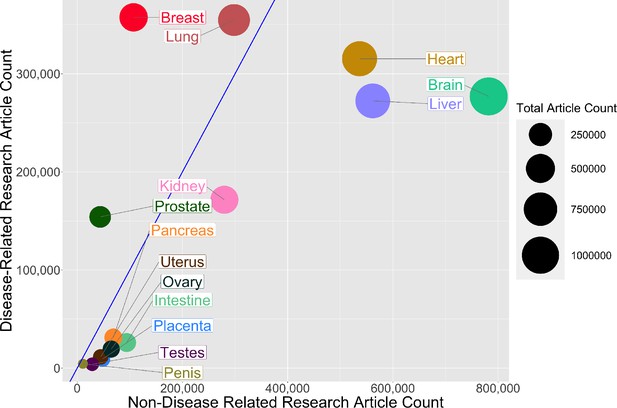

Then, for each organ, we plotted the number of publications related to disease on the vertical axis, and the number not related to disease on the horizontal axis, which revealed a high degree of variation among the organs ( Figure 2 ). For three non-reproductive organs (brain, heart, and liver) the number of publications not related to disease was almost three times as high as the number related to disease, and for two non-reproductive organs (kidney and lung) the numbers were similar. For the breast and prostate, on the other hand, the number of publications related to disease was three times as high as the number not related to disease. For the five remaining reproductive organs, and also for the intestine and pancreas, the number of publications not related to disease was about twice as high as the number related to disease (although the total number of publications for these seven organs was about an order of magnitude lower than the number for the other seven organs).

Comparing research related to disease and research not related to disease for reproductive and non-reproductive organs.

For each organ (colored circles) the vertical axis shows the number of publications for the period 1966–2021 related to disease, and the horizontal axis shows the number not related to disease: the area of the circle is proportional to the total number of publications. The straight blue line corresponds to equal numbers of disease-related and non-disease-related publications, so organs to the right of this line (notably non-reproductive organs such as the brain, heart and liver) tend to be the subject of more basic or non-disease-related research, whereas organs to the left of this line (notably reproductive organs such as the breast and prostate) tend to be the subject of disease-related research. The lung is the only non-reproductive organ in our sample to the left of the blue line.

Figure 2—source data 1

Total number of articles on research related to disease and research not related to disease for reproductive and non-reproductive organs.

Research funding

Next we used databases belonging to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the NIH to investigate funding trends for the different organs. The 14 keywords (brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta) were entered into each database, and we extracted funding data for the period between 2013 and 2018. These organs were chosen as keywords to investigate the funding related to a basic understanding of the biology of these organs. Although grants that relate to pregnancy or fertility may not be captured, these topics are much broader and would introduce subtopics outside of the reproductive scope, similar to using keywords such as metabolism or behaviour. Table 2 gives the number of projects for each keyword and the corresponding average funding amount per grant for the CIHR, and the same for the NIH. Our analysis found that the mean grant amounts for the CIHR and NIH are similar between different keyword research topics (CIHR: $ 370 000 ± $ 50 000; NIH: $ 481 500 ± $ 50 000). The similar funding amounts between different organs are encouraging and may result from standard funding guidelines for biomedical research. However, our analysis found that the average number of funded projects is much higher for non-reproductive organs compared to reproductive organs for both the CIHR (800 vs 115) and the NIH (31 000 vs 5 300).

Total number of projects funded and average grant (in Canadian or US dollars) for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (columns 2 and 3) and the US National Institutes of Health (columns 4 and 5) for the years 2013–2018 for seven non-reproductive keywords and seven reproductive keywords (column 1).

| Keyword | Number of projects (CIHR) | Average grant funded (CAD) | Number of projects(NIH) | Average grant funded(USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reproductive keywords | ||||

| 1686 | $391,023 | 81666 | $441,149 | |

| 1214 | $369,665 | 43833 | $491,993 | |

| 1597 | $314,473 | 22072 | $454,276 | |

| 526 | $371,154 | 34492 | $525,631 | |

| 347 | $424,360 | 21176 | $508,853 | |

| 128 | $444,490 | 5800 | $371,727 | |

| 96 | $491,274 | 8649 | $482,901 | |

| Reproductive keywords | ||||

| 459 | $336,734 | 19132 | $525,134 | |

| 143 | $299,034 | 8960 | $514,638 | |

| 42 | $379,349 | 4814 | $520,804 | |

| 105 | $369,825 | 2169 | $526,147 | |

| 45 | $324,690 | 1356 | $509,250 | |

| 10 | $372,110 | 340 | $500,160 | |

| 1 | $304,676 | 323 | $369,434 | |

Table 2—source data 1

Source data for Table 2 .

Our analysis suggests a bias against research into reproductive health and disease, and it is important that efforts are made to eliminate this bias so that research into reproductive medicine does not fall further behind. The higher levels of research observed for some reproductive organs (notably the breast and prostate) were driven by cancer-focused research, but this has not led to an increase in the level of non-disease-related research on these organs ( Figure 1B ). Factors such as Breast Cancer Awareness Month ( Jacobsen and Jacobsen, 2011 ) and screening programmes for prostate cancer ( Dickinson et al., 2016 ) likely led to the increase in publications about these two reproductive organs.

While our analysis is suggestive that many reproductive organs achieve a good balance of non-disease versus disease-related research, the paucity of research is highly problematic to the field. An important consideration is that a lack of non-disease-related research on reproductive organs may hinder progress in diagnosing and treating a wide range of pathologies (including preeclampsia, polycystic ovary syndrome, and endometriosis).

In a competitive funding system, publications are correlated to successful grants and dollar values awarded. Across research areas, we found that the mean grant dollar amounts per project are similar. However, the numbers of funded research projects on non-reproductive organs were higher than the numbers for reproductive organs by a factor of 6–7 (which is slightly larger than the discrepancy seen in publication rates). An important consideration is that the part of the NIH that supports reproductive research in the US, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, is one of the lowest-funded institutes at the NIH and does not have the word reproduction in its title. In Canada, the Human Development, Child and Youth Health Institute of CIHR is a funder of most pregnancy and reproductive biology grants, typically awarded through the Clinical Investigation – A panel, and it may be that the use of a clinical panel to fund this area of research inhibits non-diseased focused research. This panel is well-funded relative to other panels; however, some research areas (e.g., cardiovascular and neurological research) have more than one panel.

A growing political and societal emphasis is placed on disease-related research, such as cancer. This may arise from a view of basic research as ineffective or inefficient compared to applied research ( Lee, 2019 ). Perhaps this is best seen in our analysis by the high percentage of research publications on the prostate and breast that are due to cancer research, whereas most research on the other reproductive organs we studied was not disease-related. While the placenta and uterus are widely viewed as causal organs for reproductive complications that claim large numbers of maternal and neonatal lives, and treatments cost tens of billions of US dollars every year, there is relatively little disease-related research into these organs. The investigation of cancer biology within a reproductive organ can rely on knowledge of cancer in other organ systems. However, the low levels of research into reproductive organs relative to other organs means that there is much less foundational knowledge to rely on when seeking to develop treatments for diseases of these organs. Moreover, there are fewer researchers who are experienced on working with these organs.

There are several limitations to our approach. One important limitation is that the number of unfunded grant applications is not accessible, so we could not determine if the lower numbers of grants for research on reproductive health and disease were due to proportionally lower total application numbers, or to a bias against reproductive research. Funding bodies should conduct internal analyses to determine appropriate action. The use of keywords to distinguish between non-disease and disease-related research is a limitation, and the relatively low numbers of publications on reproductive organs can also present challenges when making comparisons. However, the differences we observe between research into reproductive and non-reproductive organs (as measured by numbers of publications and levels of funding) are large and are unlikely to result from missing search terms.

How can we address the research gap and enable the field of reproductive health and disease to catch up with other areas of research? Based on our analysis, we need to increase the number of researchers working on reproductive organs and related pathologies. Recent efforts by the NIH, such as the Human Placenta Project ( Guttmacher et al., 2014 ), indicate a recognition of the need to increase research capacity in reproductive sciences, and may lead to further increases in both interest and research capacity in the longer term.

New researchers may avoid the reproductive field due to social and political factors and the research gap (ie, the low levels of grant funding and publications), and this in turn may discourage students and trainees, which will make it even more difficult to increase the size of the research base. While continued advocacy, education, and political lobbying may help to overcome many of the social and political factors, closing the research gap will require other approaches.

To increase researchers and research output, we may learn lessons from the examples of breast and prostate cancer. In both cases, research increased dramatically from a historically low level. While public campaigns played a prominent role in these increases, the existence of a large pool of researchers and trainees already working on other types of cancers was probably more important (as it was these researchers, rather than those doing non-disease-related research on these organs, who did most of the work on breast and prostate cancer). However, this is unlikely to work for preeclampsia and other reproductive pathologies as there are no large pools of existing researchers available to switch the focus of their work.

Therefore, to increase research capacity, we should promote collaborations between researchers working on reproductive health and disease and those working in other areas of physiology and medicine, especially other areas with much higher research capacities. There are plenty of examples that show the benefit of such an integrated approach. For instance, female sex hormones protect against many aging diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurological diseases, leading to the prescription of hormone replacement therapies after menopause in some women ( Paciuc, 2020 ).

Links to immunology, cardiology and other systems can be used to increase research capacity. During pregnancy, there are dramatic changes in maternal physiology, including metabolism, the immune system, and cardio-pulmonary systems, and consequently, these are the same systems affected by reproductive pathologies. Preeclampsia predisposes the mother to a long-term cardiovascular risk of developing peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure ( Rana et al., 2019 ). Additionally, complications of the liver and kidney are associated with preeclampsia. Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis are related to metabolism problems and the risk of cancer development. Children born from pregnancies affected by preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction are at a 2.5 times higher risk of developing hypertension and require anti-hypertensive medications as adults ( Ferreira et al., 2009 ; Fox et al., 2019 ).

The pathological interaction of reproductive with non-reproductive systems and organs should attract investigators from nephrology, hepatology and cardiovascular research, where the total number of researchers is 10–20 times as high as the number in reproductive health and disease. If just 1% of the researchers in the cardiovascular field were to refocus on pregnancy-related cardiovascular adaptation and pathologies, this would increase reproductive research by 10%.

Our neglect of the placenta and reproductive biology impedes other biomedical research areas. In cancer research, the methylation patterns of tumours look most like those found in the placenta, but why placenta methylation patterns are so unlike all other organs is not known ( Smith et al., 2017 ; Rousseaux et al., 2013 ). In regenerative medicine, the immune-modulating genes used by the placenta ( Szekeres-Bartho, 2002 ) are repurposed to generate universally transplantable stem cells and tissues ( Han et al., 2019 ). A poor understanding of reproductive biology is dangerous, considering emerging diseases that affect pregnancy and fetal development, such as the recent Zika virus outbreak ( Schuler-Faccini et al., 2016 ; Calvet et al., 2016 ). There are likely many other broad benefits to better understanding reproductive biology. The time to act is now, as waiting longer will not improve the situation.

Publication rates

Published research manuscripts were searched in NCBI’s PubMed database ( https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ) between and including the years 1966 and 2021. Keywords for each search pertained to a specific organ or disease and were limited to the title/abstract of the manuscripts. The organs used for these analyses were the brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta. We restricted the organ publication timelines to the years 1966–2021 and extracted the annual article count. The organ publication timeline was reconducted with the addition of the search parameter "NOT cancer".

Funding rates

Grant funding data was obtained from the CIHR funding database ( https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/funding/Search?p_language=E&p_version=CIHR ) and the NIH reporter tool ( https://reporter.nih.gov ) by searching keywords in the title and abstracts/summary. Keywords used for these searches were brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta. The years were restricted to 2013–2018. The total number of projects pertaining to each search term during this period was extracted, and the total amount of funding for those projects was averaged.

All graphs were produced using R (version 4.0.2) in R Studio (version 1.3.1073). R packages used were ggplot2, tidyverse, formattable, gridExtra, RColorBrewer, ggrepel.

All data were obtained from public databases (PubMed/NCBI, NIH and CIHR). Source data files for Figure 1, Figure 2 and Table 2 are available (see figure and table captions for details).

- Google Scholar

- de Filippis I

- de Sequeira PC

- de Mendonça MCL

- de Oliveira L

- Tschoeke DA

- Thompson FL

- Dos Santos FB

- Nogueira RMR

- de Filippis AMB

- Coen-Sanchez K

- El-Mowafi IM

- Idriss-Wheeler D

- Dickinson J

- Connor Gorber S

- Stehouwer CDA

- Lewandowski AJ

- Guttmacher AE

- Ferreira LMR

- Strominger JL

- Meissner TB

- Barabási AL

- Institute of Medicine

- Jacobsen GD

- Jacobsen KH

- Pickering K

- Karumanchi SA

- Rousseaux S

- Debernardi A

- Nagy-Mignotte H

- Moro-Sibilot D

- Brichon P-Y

- Lantuejoul S

- de Reyniès A

- Brambilla C

- Brambilla E

- Schuler-Faccini L

- Feitosa IML

- Horovitz DDG

- Cavalcanti DP

- Doriqui MJR

- Wanderley HYC

- El-Husny AS

- Sanseverino MTV

- Brazilian Medical Genetics Society–Zika Embryopathy Task Force

- Cacchiarelli D

- Szekeres-Bartho J

- Browning WR

- Mugavero MJ

- Peter Rodgers Senior and Reviewing Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

- Marleen van Gelder Reviewer

- James Roberts Reviewer

In the interests of transparency, eLife publishes the most substantive revision requests and the accompanying author responses.

Decision letter after peer review:

Thank you for submitting the paper "A Poor Research Landscape Hinders the Progression of Knowledge and Treatment of Reproductive Diseases" for consideration by eLife . Your article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, and the evaluation has been overseen by a Reviewing Editor and a Senior Editor. The following individuals involved in review of your submission have agreed to reveal their identity: Marleen van Gelder (Reviewer #1); James Roberts (Reviewer #3).

This article will need considerable revision to be suitable for publication as a Feature Article. In particular, you will need to address the concerns raised by the referees (see below), and also address a number of editorial points.

Reviewer #1

In this manuscript, Mercuri and Cox aimed to quantify the advancement of research in reproductive sciences relative to other medical disciplines. They compared two indicators of the research landscape: published research manuscripts and funded projects. The results showed lower publication rates for research on reproductive organs compared to selected non-reproductive organs, in particular concerning basic research. In addition, a relatively small number of grants was funded for projects on diseases with a reproductive focus. Based on these data, the authors concluded that the gap in knowledge and treatment of diseases of the reproductive organs is at least partially caused by a poor research landscape.

Although the conclusions of this paper are somewhat supported by the data, some aspects of the methods and reporting need to be clarified.

[Note: The following point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

1) The manuscript, and in particular the Introduction and Discussion sections, could benefit from restructuring, in which adhering to a relevant reporting guideline may be helpful. For example, the authors provide relatively extensive background information on a number of important reproductive health disorders, but the level of detail does not contribute to setting the aim for the study. Moreover, the last paragraph of the introduction section (lines 92-100) already seems to include the conclusion of this paper.

[Note: Please address points b, d and f below. The other points are covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

2) Concerns regarding the methods:

a) Citations in PubMed are known to be selective before 1966; consider using a fixed start date/year for the search.

b) The results strongly depend on the organs and diseases selected to be included in the 'reference group'. Provide a rationale for the selection of organs, which in the current analysis only seem to include major organs that are known to be well-studied, and not organs such as skin, eyes, intestine, pancreas, spleen or urinary bladder. The selection is vital for drawing robust conclusions from the data.

c) The approach to distinguish between basic and applied research is not validated.

d) The prevalence of diseases reported in Figure 4 is highly country-specific, in particular for tuberculosis. Therefore, this comparison may not be suitable for an international audience.

e) The most important limitation of the grant funding data was already mentioned: "the number and keywords of failed grant applications were not accessible" (lines 271-272). Therefore, it is hard to draw conclusions on failure of grant applications on reproductive health.

f) The rationale for the keywords used in the funding databases is missing and likely to yield selective results. Many reproductive health related projects may be missed, as keywords such as pregnancy and subfertility were not included. And also in this search, the selection of keywords for the reference group seems biased.

[Note: Please consider adding a table as suggested below; however, this is optional rather than essential.]

3) To emphasize the lack of knowledge in relation to disease burden, a table summarizing the prevalence, number of publications, and grants could summarize the results.

[Note: This point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

4) A number of topics and statements in the Discussion section seem to be unrelated to the aim of this study. Examples include the female representation in STEM disciplines and the correlation between research publications and changes in policy (this was not specifically analyzed and would require additional analyses).

Reviewer #2

[Note: Please address the following point]

While the authors have attempted to be broad in their assessment of reproduction research, they seem to neglect two very broad areas of women's health for which there is little research: menstruation and menopause. Both are only mentioned in the discussion, and referenced with respect to promotion of the study of human physiology. Given the focus on lack of basic understanding of reproductive organs, it may be worth mentioning these, particularly in comparison to the depth of research on erectile dysfunction; this may also help to emphasize the fact that the lack of research in reproduction primarily affects women (though there are of course consequences for men's health, including the period in the womb).

Figure 1: the color code is not clear; Not sure how this could be better represented, but maybe listing the organs from high to low for both parts a and b in the legend? Or magnifying one part of each graph? In particular, the 80% loss of publications in breast/prostate when applying the search term "NOT cancer" does not come through; so perhaps a graph focusing on just these two organs showing the original search and the "NOT cancer" search results would be best?

Tables 2 and 3: It is not clear how this search was done; was the project title or abstract of grants searched for these key terms?

Discussion (including lines 259-260): I'm not sure that the conclusion drawn here is consistent with the data? The authors somewhat confusingly alternate between lack of research in reproduction as a whole vs. lack of basic research in this area.

[Note: Addressing the following point is optional, not essential.]

Another point of discussion that merits mention here is how the lack of interest/emphasis on reproduction research by funding agencies in turn affects the perception of "impact" of such research: i.e. both in terms of how low impact factors of reproduction journals are compared to journals in other fields, but also how the high-impact journals (Cell/Science/Nature) view/receive submissions from researchers in this area. Reviewer #3

The authors propose that research in reproductive areas lags behind that of other areas of biology. They support this with information from publications and funding sources.

This is a presentation of importance to investigators in all fields, funders and the general public. For reproductive investigators it provides objective data to support the lagging of reproductive research and to investigators in other areas of biology and the general public should be an eye opening demonstration of the huge gap between research in reproduction and other areas of biology. One would hope it would also provide a motivation to funders to modify the situation.

The authors remind us of the importance of reproduction on the survival of the species and provide extensive data on specific examples of the impact of reproductive diseases. They then use review of publications keyed to reproductive organs and non-reproductive organs both currently and over time. They point out that research on non-reproductive organs is 5 to 20 times more frequent than that on reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] They should make it clearer that this is referring to specific organs and not a comparison sum of research on all organs of reproduction and not reproduction. They show that over time this discrepancy has increased with the exception of prostate, and breast research but even with those it is evident this is research related specifically to cancer and not normal organ function.

They make a slightly less compelling comparison on the portion of research devoted to basic understanding or clinical research which for nonreproductive organs is considerably more for basic science than in reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] However, this is likely compromised by the relative minute number of either type of studies in reproduction.

They then make comparisons between the impact of specific reproductive topics and publications. They state that although preeclampsia and breast cancer have a similar prevalence the number of breast cancer publications are much higher. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] To me the comparison of a disorder with high mortality (breast cancer) and far lower mortality (preeclampsia) does not provide a compelling argument and also is a little off target for comparing reproductive and nonreproductive research.

[Note: Please address the point made in the following paragraph]

They make a similar comparison of PCOS a reproductive disorder with other non-reproductive disorders of similar or lower prevalence, autism, tuberculosis, Crohn's Disease and Lupus with a much lower publication rate for PCOS. Again, this seems a bit of comparing apples and oranges.

They investigate the relative funding of research on these topics in the US and Canada and find that the size of individual grants for reproductive and non-reproductive research in both countries is similar but that the number of funded grants for specific non-reproductive organs is, that like that of publications, is about 2 to 20 times higher for nonreproductive organs.

The authors present their conclusions of the reason for the discrepancy. They point out gender bias which has been a target for improvement for several years and has been reduced but research is still not on an equal basis for men and women. However, the bias goes beyond gender since male reproductive research publications and funding also lags. They conclude that there is a general bias against reproductive research. [Note: Please consider mentioning the following point in your article] Interestingly they do not cite a major support for this conclusion, that the major NIH institute supporting reproductive research, the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD)is one lowest funded institutes and does not have reproduction in its title.

They provide two general suggestions to increase reproductive research. The first is to increase funding and the second to involve other forms of research in studies supporting the role of reproductive disorders and physiology in non-reproductive studies. [Note: Please address the point made in the rest of this paragraph] They point out the relationship of preeclampsia to later life cardiovascular disease as an example of this. Unfortunately, they state this relationship as causal which has not been established. Nonetheless studying preeclampsia will likely provide information useful to cardiovascular health.

It is possible that linking publications and funding amounts to conclusions about bias against reproductive research is not precise. However, the magnitude of the differences strongly supports the authors' premise.

This interesting presentation makes and important point about the fact that reproductive research lags beyond other biological research. They do this through the use of publication and grant funding reviews. The differences are large in a direction that support the point they are making. There are some suggestions that I believe would improve the presentation.

[Note: Please address the following three points]

1. There should be a bit more discussion of the limitations of their approach.

2. In the comparisons of disorders of reproduction and non-reproduction they should indicate the limitations of comparing very different disorders.

3. Preeclampsia as a cause of later life CVD has not been established. They are related.

Reviewer #1 In this manuscript, Mercuri and Cox aimed to quantify the advancement of research in reproductive sciences relative to other medical disciplines. They compared two indicators of the research landscape: published research manuscripts and funded projects. The results showed lower publication rates for research on reproductive organs compared to selected non-reproductive organs, in particular concerning basic research. In addition, a relatively small number of grants was funded for projects on diseases with a reproductive focus. Based on these data, the authors concluded that the gap in knowledge and treatment of diseases of the reproductive organs is at least partially caused by a poor research landscape. Although the conclusions of this paper are somewhat supported by the data, some aspects of the methods and reporting need to be clarified. [Note: The following point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you] 1) The manuscript, and in particular the Introduction and Discussion sections, could benefit from restructuring, in which adhering to a relevant reporting guideline may be helpful. For example, the authors provide relatively extensive background information on a number of important reproductive health disorders, but the level of detail does not contribute to setting the aim for the study. Moreover, the last paragraph of the introduction section (lines 92-100) already seems to include the conclusion of this paper.

This query has been responded to the in Word file

[Note: Please address points b, d and f below. The other points are covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you] 2) Concerns regarding the methods: a) Citations in PubMed are known to be selective before 1966; consider using a fixed start date/year for the search.

This query has been responded to the in Word file. We have now used a fixed date of 1966 as the early timepoint and as indicated in the Word file.

Organs such as brain, heart and lungs are essential for life. The placenta is similarly essential. Other organs such as kidney and liver are also essential but not as immediate. We now include the intestine as a reference point.

Our preliminary analysis found that Skin has over 800,000 publication mentions, but it is not clear if this is the skin organ or a skin on something more work to eliminate background skin hits would be needed. Epidermis has 60,000 hits that are likely more specific, but we did find may abstracts and titles on the skin organ that do not use epidermis. Eyes are nearly 700,000 publications, intestine also over 700,000, pancreas has over 200,000 spleen is also over 200,000 urinary bladder has 130,000, which is similar to the placenta at just over 100,000

This preliminary search seems to still support our conclusion that placenta and reproductive organs are under-researched and only add a list of other organs that are better studied.

Comparisons of diseases has been removed from the manuscript.

We have removed disease focused terms form the search to ensure we capture organ focus research. The inclusion of pregnancy or subfertility would be misleading as it would include disciplines such as sociology and psychology. This is akin to searching for diabetes or metabolism to understand the research landscape on the pancreas.

We felt the separate tables made the information more digestible.

This query has been responded to the in Word file. We have extensively edited and redrafted the Discussion section.

Reviewer #2 [Note: Please address the following point] While the authors have attempted to be broad in their assessment of reproduction research, they seem to neglect two very broad areas of women's health for which there is little research: menstruation and menopause. Both are only mentioned in the discussion, and referenced with respect to promotion of the study of human physiology. Given the focus on lack of basic understanding of reproductive organs, it may be worth mentioning these, particularly in comparison to the depth of research on erectile dysfunction; this may also help to emphasize the fact that the lack of research in reproduction primarily affects women (though there are of course consequences for men's health, including the period in the womb). Figure 1: the color code is not clear; Not sure how this could be better represented, but maybe listing the organs from high to low for both parts a and b in the legend? Or magnifying one part of each graph? In particular, the 80% loss of publications in breast/prostate when applying the search term "NOT cancer" does not come through; so perhaps a graph focusing on just these two organs showing the original search and the "NOT cancer" search results would be best?

These corrections have been made to the in Word file.

We agree and have focused the discussion on the general low level of publications and low level of researchers in the field.

Another point of discussion that merits mention here is how the lack of interest/emphasis on reproduction research by funding agencies in turn affects the perception of "impact" of such research: i.e. both in terms of how low impact factors of reproduction journals are compared to journals in other fields, but also how the high-impact journals (Cell/Science/Nature) view/receive submissions from researchers in this area.

This is an issue many discipline struggle with. A low number of researchers in a field tends to create low levels of impact as measured through citations. Attempts to normalize impact factors and citation rates to the size of the field may help. While we agree with the reviewers comments we cannot address within our study.

Reviewer #3 The authors propose that research in reproductive areas lags behind that of other areas of biology. They support this with information from publications and funding sources. This is a presentation of importance to investigators in all fields, funders and the general public. For reproductive investigators it provides objective data to support the lagging of reproductive research and to investigators in other areas of biology and the general public should be an eye opening demonstration of the huge gap between research in reproduction and other areas of biology. One would hope it would also provide a motivation to funders to modify the situation. The authors remind us of the importance of reproduction on the survival of the species and provide extensive data on specific examples of the impact of reproductive diseases. They then use review of publications keyed to reproductive organs and non-reproductive organs both currently and over time. They point out that research on non-reproductive organs is 5 to 20 times more frequent than that on reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] They should make it clearer that this is referring to specific organs and not a comparison sum of research on all organs of reproduction and not reproduction. They show that over time this discrepancy has increased with the exception of prostate, and breast research but even with those it is evident this is research related specifically to cancer and not normal organ function.

Thank you for this comment. These clarifications have been made to the in Word file.

We agree that the lower level make estimating the ratio of basic to applied very challenging. But there seems to be a tendency to bias to basic research. We made some changes to the results and discussion to acknowledge this challenge.

We agree and have remove the section discussing a comparison of disease prevalence and mortalities. We realize there was no benefit to comparison disease prevalence and severity.

They investigate the relative funding of research on these topics in the US and Canada and find that the size of individual grants for reproductive and non-reproductive research in both countries is similar but that the number of funded grants for specific non-reproductive organs is, that like that of publications, is about 2 to 20 times higher for nonreproductive organs. The authors present their conclusions of the reason for the discrepancy. They point out gender bias which has been a target for improvement for several years and has been reduced but research is still not on an equal basis for men and women. However, the bias goes beyond gender since male reproductive research publications and funding also lags. They conclude that there is a general bias against reproductive research. [Note: Please consider mentioning the following point in your article] Interestingly they do not cite a major support for this conclusion, that the major NIH institute supporting reproductive research, the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD)is one lowest funded institutes and does not have reproduction in its title.

Thank you for this comment, we have added it!

Thank you for the comment, we modified our statement to an observed increased risk of cardiovascular disease, as the risk may be causal or associated as the reviewer stated.

It is possible that linking publications and funding amounts to conclusions about bias against reproductive research is not precise. However, the magnitude of the differences strongly supports the authors' premise. This interesting presentation makes and important point about the fact that reproductive research lags beyond other biological research. They do this through the use of publication and grant funding reviews. The differences are large in a direction that support the point they are making. There are some suggestions that I believe would improve the presentation. 1. There should be a bit more discussion of the limitations of their approach.

We have added more caveats about our approach and interpretation

The comparisons of diseases has been removed.

This is addressed as per the above comment.

Author details

Natalie D Mercuri is in the Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Contribution

Competing interests.

Brian J Cox is in the Department of Physiology and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

For correspondence

University of toronto, canada research chairs.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Toronto and the Department of Physiology for providing the opportunity and supporting the completion of this review. We also thank the librarians who offered expert advice on keyword searches of databases.

Publication history

- Received: October 28, 2021

- Preprint posted : November 19, 2021

- Accepted: December 12, 2022

- Accepted Manuscript published : December 13, 2022

- Accepted Manuscript updated : December 13, 2022

- Version of Record published : December 21, 2022

© 2022, Mercuri and Cox

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as pdf).

- Article PDF

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools), categories and tags.

- reproductive biology

- reproductive health

- meta-research

Research organism

- Of interest

FBXO24 deletion causes abnormal accumulation of membraneless electron-dense granules in sperm flagella and male infertility

Further reading.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules are membraneless electron-dense structures rich in RNAs and proteins, and involved in various cellular processes. Two RNP granules in male germ cells, intermitochondrial cement and the chromatoid body (CB), are associated with PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) and are required for transposon silencing and spermatogenesis. Other RNP granules in male germ cells, the reticulated body and CB remnants, are also essential for spermiogenesis. In this study, we disrupted FBXO24, a testis-enriched F-box protein, in mice and found numerous membraneless electron-dense granules accumulated in sperm flagella. Fbxo24 knockout (KO) mice exhibited malformed flagellar structures, impaired sperm motility, and male infertility, likely due to the accumulation of abnormal granules. The amount and localization of known RNP granule-related proteins were not disrupted in Fbxo24 KO mice, suggesting that the accumulated granules were distinct from known RNP granules. Further studies revealed that RNAs and two importins, IPO5 and KPNB1, abnormally accumulated in Fbxo24 KO spermatozoa and that FBXO24 could ubiquitinate IPO5. In addition, IPO5 and KPNB1 were recruited to stress granules, RNP complexes, when cells were treated with oxidative stress or a proteasome inhibitor. These results suggest that FBXO24 is involved in the degradation of IPO5, disruption of which may lead to the accumulation of abnormal RNP granules in sperm flagella.

- Cell Biology

Caenorhabditis elegans SEL-5/AAK1 regulates cell migration and cell outgrowth independently of its kinase activity

During Caenorhabditis elegans development, multiple cells migrate long distances or extend processes to reach their final position and/or attain proper shape. The Wnt signalling pathway stands out as one of the major coordinators of cell migration or cell outgrowth along the anterior-posterior body axis. The outcome of Wnt signalling is fine-tuned by various mechanisms including endocytosis. In this study, we show that SEL-5, the C. elegans orthologue of mammalian AP2-associated kinase AAK1, acts together with the retromer complex as a positive regulator of EGL-20/Wnt signalling during the migration of QL neuroblast daughter cells. At the same time, SEL-5 in cooperation with the retromer complex is also required during excretory canal cell outgrowth. Importantly, SEL-5 kinase activity is not required for its role in neuronal migration or excretory cell outgrowth, and neither of these processes is dependent on DPY-23/AP2M1 phosphorylation. We further establish that the Wnt proteins CWN-1 and CWN-2, together with the Frizzled receptor CFZ-2, positively regulate excretory cell outgrowth, while LIN-44/Wnt and LIN-17/Frizzled together generate a stop signal inhibiting its extension.

- Neuroscience

Multiple guidance mechanisms control axon growth to generate precise T-shaped bifurcation during dorsal funiculus development in the spinal cord

The dorsal funiculus in the spinal cord relays somatosensory information to the brain. It is made of T-shaped bifurcation of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory axons. Our previous study has shown that Slit signaling is required for proper guidance during bifurcation, but loss of Slit does not affect all DRG axons. Here, we examined the role of the extracellular molecule Netrin-1 (Ntn1). Using wholemount staining with tissue clearing, we showed that mice lacking Ntn1 had axons escaping from the dorsal funiculus at the time of bifurcation. Genetic labeling confirmed that these misprojecting axons come from DRG neurons. Single axon analysis showed that loss of Ntn1 did not affect bifurcation but rather altered turning angles. To distinguish their guidance functions, we examined mice with triple deletion of Ntn1, Slit1, and Slit2 and found a completely disorganized dorsal funiculus. Comparing mice with different genotypes using immunolabeling and single axon tracing revealed additive guidance errors, demonstrating the independent roles of Ntn1 and Slit. Moreover, the same defects were observed in embryos lacking their cognate receptors. These in vivo studies thus demonstrate the presence of multi-factorial guidance mechanisms that ensure proper formation of a common branched axonal structure during spinal cord development.

Be the first to read new articles from eLife

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sex Reprod Health Matters

- v.29(1); 2021

Language: English | French | French

Integrating human rights into sexual and reproductive health research: moving beyond the rhetoric, what will it take to get us there?

Sofia gruskin.

a Director, USC Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Correspondence :, ude.csu.dem@niksurg

William Jardell

b Program Specialist, USC Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Laura Ferguson

c Director, Program on Global Health and Human Rights, USC Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Kristin Zacharias

d Research Associate, USC Institute on Inequalities in Global Health, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Rajat Khosla

e Human Rights Advisor, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

The integration of human rights principles in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) research is often recognised to be of value. Good examples abound but lack of clarity persists as to what defines rights-inclusive SRH research. To help move the field forward, this article seeks to explore how key stakeholders responsible for funding and supporting rights in SRH research understand the strengths and weaknesses of what is being done and where, and begins to catalogue potential tools and actions for the future. Interviews with a range of key stakeholders including international civil servants, donors and researchers committed to and supportive of integrating rights into SRH research were conducted and analysed. Interviews confirmed important differences in what is understood to be SRH rights-oriented research and what it can accomplish. General barriers include lack of understanding about the importance of rights; lack of clarity as to the best approach to integration; fear of adding more work with little added benefit; as well as the lack of methodological guidance or published research methodologies that integrate rights. Suggestions include the development of a comprehensive checklist for each phase of research from developing a research statement through ultimately to publication; development of training modules and workshops; inclusion of rights in curricula; changes in journal requirements; and agreement among key funding sources to mandate the integration of rights principles in research proposals they receive. As a next step, cataloguing issues and concerns at local levels can help move the integration of human rights in SRH research from rhetoric to reality.

Résumé

L’utilité de l’intégration des principes des droits de l’homme dans la recherche sur la santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR) est reconnue. Les bons exemples abondent, mais un manque de clarté persiste sur la définition de la recherche sur la SSR inclusive des droits. Pour aider à progresser dans ce domaine, l’article se demande comment les principaux acteurs responsables du financement et du soutien des droits dans la recherche sur la SSR comprennent les forces et les faiblesses de ce qui est fait et où, et il commence à répertorier les outils potentiels et les mesures pour l’avenir. Des entretiens ont été réalisés et analysés avec un éventail d’acteurs clés, notamment des fonctionnaires publics, des donateurs et des chercheurs qui approuvent et soutiennent l’intégration des droits dans la recherche sur la SSR. Ils ont confirmé d’importantes différences dans ce qui est compris comme une recherche sur la SSR axée sur les droits et ce qu’elle peut accomplir. Les obstacles généraux comprennent le manque de compréhension de l’importance des droits ; l’insuffisante clarté quant à la meilleure approche de l’intégration ; la crainte de créer davantage de travail pour de faibles avantages ajoutés ; de même que le manque de conseils méthodologiques ou de méthodologies de recherche publiées qui intègrent les droits. Les suggestions comprennent la mise au point d’une liste de contrôle exhaustive pour chaque phase de recherche depuis l’élaboration de l’énoncé de la recherche jusqu’à la publication ; la préparation de modules de formation et d’ateliers ; l’inclusion des droits dans le programme d’études ; les changements dans les conditions des revues spécialisées ; et la volonté des principales sources de financement de rendre obligatoire l’intégration des principes des droits dans les propositions de recherche qu’elles reçoivent. En tant que prochaine étape, l’inventaire des problèmes et des préoccupations aux niveaux locaux peut aider à faire passer l’intégration des droits de l’homme dans la recherche sur la SSR de la théorie à la pratique.

La integración de los principios de derechos humanos en investigaciones sobre salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR) es reconocida como valiosa. Abundan los buenos ejemplos, pero persiste la falta de claridad en cuanto a qué define una investigación sobre SSR inclusiva de derechos. Con el fin de que progrese este campo, este artículo busca explorar cómo las partes interesadas clave responsables de financiar y apoyar los derechos en las investigaciones sobre SSR entienden las fortalezas y debilidades de qué se está haciendo y dónde, y empieza a catalogar posibles herramientas y acciones para el futuro. Se realizaron y analizaron entrevistas con una variedad de partes interesadas clave, tales como funcionarios, donantes e investigadores internacionales comprometidos a integrar los derechos en las investigaciones sobre SSR. Las entrevistas confirmaron importantes diferencias en lo que se entiende como investigación sobre SSR orientada hacia los derechos y qué se puede lograr. Entre las barreras generales figuran: la falta de comprensión sobre la importancia de los derechos; falta de claridad en cuanto al mejor enfoque para la integración; temor de agregar más trabajo con poco beneficio adicional; así como la falta de orientación metodológica o metodologías de investigación publicadas que integran los derechos. Algunas sugerencias son incluir la creación de una lista de verificación integral para cada fase de la investigación, desde la elaboración de la declaración de la investigación hasta la publicación; la creación de módulos y talleres de capacitación; la inclusión de derechos en currículos; cambios a los requisitos de revistas; y el acuerdo entre las principales fuentes de financiamiento de exigir la integración de los principios de derechos en las propuestas de investigaciones que reciben. Como un próximo paso, catalogar los problemas y las preocupaciones a nivel local podría ayudar a llevar la integración de los derechos humanos en las investigaciones sobre SSR de la retórica a la realidad.

It is often stated that integrating human rights in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) policies, programmes and services is essential to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” and SDG 5 “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” both include targets that call for universal access to SRH services and realisation of relevant rights. 1 The complex interplay of rights-related factors generally recognised to impact SRH outcomes includes the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of health services; informed decision making, privacy and confidentiality in the provision of health services; and nondiscrimination and equality with particular attention to key and marginalised populations. 2 , 3 SRH-related outcomes are all further helped or hindered by the unique legal and policy environment and the larger economic, social, cultural and political determinants of local contexts, including the presence or absence of accessible and functional accountability mechanisms. Attention to all these components forms part of what is considered a rights-based approach to SRH. 4

What this means for the research needed to put these policies and programmes into place is less clear. Previous writings have discussed how incorporating human rights concepts in SRH research can help

“address power imbalances within and between institutions and programs, ensure transparent, inclusive and ethical research processes, enhance good governance of research institutions and promote research programs of particular relevance to people living in poverty/under oppression, women and marginalised groups while not compromising on quality”. 5

In practical terms, the extent to which the range of rights considerations noted above form part of SRH research is not well documented, even in research that claims to have a focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights. It is also not clear from a methodological perspective what such a commitment means for each phase of research, from the development of a research question, through to implementation, analysis and publication. 6

A number of issues can be raised from the outset. How does one determine what qualifies as rights-based SRH research? Is it integration of rights at one or at every stage of the research process? Which rights are included? Is it the legal definition of rights or simply a concern with justice and equality? To qualify as rights-based SRH research, how relevant is the content or subject matter being addressed through the research? Is a focus, for example, on addressing inequalities among various population groups in their access to certain services necessarily rights-based? 5 Must rights principles, such as participation or accountability, be explicitly adopted as such, forming part of the study question and, in turn, how each phase of the research is designed and implemented? 7 , 8 Must the research team include lawyers or others with substantive expertise in rights? And how relevant is the final outcome under consideration – does it matter if the research is focused directly on, for example, increasing access to contraception versus a focus on improving the overall human rights situation for adolescents and young women, which over time will be assumed to improve access and use of contraception? 6

There is no one size fits all, nor should there be, but a number of issues must be considered. Without setting out to explicitly answer each of the questions noted above, we set out to determine the potential factors that may help or hinder efforts to integrate rights into SRH research in practice, with a focus on understanding what is being done and how, and not only the successes, but the challenges faced in integrating rights into research. A literature review found that the integration of rights has yet to be comprehensively explored in the literature, even as confronting these issues and addressing them head-on seem to be recognised as of critical importance to moving the field forward. Identified barriers to implementing rights in SRH programming included broad structural, policy and health systems barriers as well as perceived financial cost, staffing and time constraints and a lack of understanding of how concretely to include human rights, while facilitators included the existence of human rights champions and leadership, strong civil society participation, training, guidelines and funding made available specifically for implementation. 9 Additional key issues identified included the understanding of what human rights are and what they offer, awareness of appropriate methodologies, political will, the need for an enabling environment and clear accountability mechanisms. 9 Identified barriers and best practices were utilised to set the parameters for this study.

This article explores the current status of rights integration in SRH research through key informant interviews to understand what is being done and where, successes and barriers to wider adoption of rights in SRH research, and to begin to consider tools, approaches and other actions that might be useful. These interviews are used as background for the analysis and discussion that follow.

This section describes the methodology used to select key informants as well as the approach taken to data collection and analysis.

Participant selection

Without aiming for saturation, 10 key informants centrally engaged in and committed to integrating rights into SRH research and/or relevant programming from a variety of disciplinary and organisational perspectives were interviewed between April and August 2019. These included donors, international civil servants (e.g. policymakers, programme implementers) and researchers, with both personal and organisational commitment to integrating rights within their work, including from the United Nations, national governments and international funding agencies.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer using an interview guide developed for this purpose by the research team. The objective of these interviews was to determine how key stakeholders generally understand the quality and approach to what is being done and where, barriers they see to wider integration of rights in SRH research and tools and other actions they think would be useful to better incorporate rights into every stage of SRH research from the definition of the research question through to implementation, data analysis and publication. Detailed notes were taken during the interviews to capture content reported by informants.

Data analysis

Capturing key points emergent in the interview data, notes from the 10 interviews were analysed looking for examples of current rights integration as well as challenges and successes in integrating rights at each phase of the research process. An iterative process of analysis was conducted. The literature review noted earlier was used to frame and analyse interview data, including attention to potential tools and approaches to take this work forward. 9

Respondents provided general reflections on all that it takes to incorporate rights into SRH research including substantive and methodological challenges. They also noted overarching questions and approaches that they thought might be helpful to move the field forward. The findings presented below include salient quotes to illustrate the points being made.

In the first instance, several ways in which attention to rights can help to strengthen SRH research were noted by respondents. These included attention to power and power dynamics, understanding the condition and position of research subjects (whatever the topic), substantive attention to inequalities, and the potential to use the legal grounding of rights for subsequent advocacy and potential policy change resulting from research findings.

“(Rights) strengthens (research) because it systematically draws attention to the things that we think matter that aren’t often explicitly called out in research and you can tell why things are or are not happening.” (KII7, Researcher)

“Power dynamics affect every part of a person’s experience including how the research is done and perceived, and I don’t think we’re as thoughtful about that as we need to be from the research perspective.” (KII4, Funder)

Nonetheless, a concern raised by one key informant, and echoed by others, centred on the view of many in the SRH research community that rights are political, legal, and/or are not helpful to SRH research unless the research is expressly concerned with addressing a rights concern such as gender inequality.

“The weaknesses are that human rights are in the first instance assumed to be political and people are scared of them, especially governments. Making clear to people that rights can be helpful to get to their outcomes is key to moving this work forward.” (KII7, Researcher)

Respondents also described a general unwillingness among many SRH researchers who fear that the addition of rights to their research may be too expensive, too fuzzy, or take too long.

“It’s considered a second-level priority unless the study is looking at that [rights] explicitly.” (KII1, Senior International Civil Servant)

According to respondents, limited knowledge of sound methodological approaches for how to incorporate rights into research has also hindered their ability to take hold. For example, even as contraception, abortion and maternal health are areas where rights have been more or less successfully integrated from a programming perspective, this has not translated into research efforts, even within these same areas.

“There was some work done around contraception, abortion, and maternal health but that was in programming and it’s not something that researchers would consider a natural part of their work.” (KII3, Retired Senior International Civil Servant and Funder)

Furthermore, it was noted that some researchers think that, because they have a good heart and a general concern with social justice, they are already incorporating rights into SRH research, adding to further confusion about what is actually needed to integrate rights into SRH research effectively. When rights integration has happened systematically, respondents shared that it tends to be associated with specific donors.

“The weakness is methodology, and awareness of the methodologies that do work. Integrating and unpacking on a granular level tends to be very nascent at this stage … When it does happen, it is largely focused on certain geographic areas funded by certain donors only … ” (KII6, International Civil Servant)

The importance of both funders and ethical review boards was a recurring theme. Respondents discussed how the interests of donors or the strength and focus of ethical review boards play a role in how strongly human rights concerns or protections are dealt with when developing and implementing a research study. It seems that, even with the best of intentions, there are few funders or review boards who fully know how to engage rights in research despite general interest in doing so. Even when funders or review boards insist on attention to rights, there are researchers who lack a commitment to rights and simply pay lip service to rights in their initial conceptualisation because they are focused on getting the research through, and not necessarily because they see the added benefit of doing so. Respondents also noted that even when there is a commitment to rights at the time of the initial conceptualisation of a research project, they would often be forgotten as the work moved forward.

“I have not seen many protocols that explicitly mention human rights and include them from the very start and all the way through the structure of the project. However, rights are very often mentioned in the background … It’s mentioned as something that is helpful and important, but it’s rarely incorporated into the design.” (KII2, Senior International Civil Servant)

“As a researcher, if you’re not asked for ‘the why’, then you’re not going to look for those answers.” (KII9, International Civil Servant)

“ … . sometimes when you don’t talk about something you forget about it and then that really biases how you’re understanding the problem. You forget that it’s a part of the equation … It’s like this with rights.” (KII4, Funder)

Even when researchers have a commitment to bringing rights into the operational phases of their research, substantive barriers remain concerning content and actual implementation. One interviewee discussed the importance of having rights-focused indicators for data collection embedded in each phase of the study design to ensure attention to rights can be carried all the way through.

“One of the challenges or barriers in the incorporation of each right per se is that we totally lack the measurements and don’t collect enough data on the context in which we are working or the people we are working with to make an assessment as to if, for example, we are discriminating or leaving people out.” (KII4, Funder)

Another barrier noted to ensuring that rights-oriented methodologies that do exist become known and can be replicated concerns the limited appetite of many peer-reviewed journals to publish the details of the sorts of methodologies needed to incorporate rights into research, resulting in rights being less apparent in published work.

“The bias is in the epidemiological framing. If we do an analysis that brings in rights considerations, getting this paper into X or Y journal may often be more in the editorial section than in the peer-reviewed, biomedical research section.” (KII9, International Civil Servant)

Respondents generally made the point that, even with the best of intentions, the ability to integrate rights into research requires training and experience. They emphasised that any such training needs to make clear not only the need to draw attention to the reasons for paying attention to rights and the potential value added, but the concrete ways rights can be integrated into the different phases of research.

“With gender and human rights as you go beyond what people have learned and it is less familiar this will require more time.” (KII3, Retired Senior International Civil Servant and Funder)

“It’s been a steep learning curve for me … I’ve learned so much in the past few years and I think people at the major public health places need to do the same. As I’ve come to understand a human rights perspective … I have learned a lot: what it is, what it means to apply it, etc.” (KII1, Senior International Civil Servant)

Respondents provided a number of recommendations they saw as useful next steps to facilitate SRH researchers’ ability to bring rights into the different phases of SRH research, from approaches to developing research objectives to the sorts of tools and actions needed at every stage of the research process.

Interviewees discussed as a first order of business the need to establish a willingness among researchers to learn and develop the necessary skills and suggested messaging in a variety of fora on the added value rights could bring to their work.

“There is a need for good public health research in the first place. And then what difference does it make using a rights-based approach to the study design or research questions? What are the underlying determinants, power structure? These questions need to be embedded in the study design. This starts to highlight the nature of tools that are required; training programs, facilitated online platforms that are specific to guiding people through all phases or research.” (KII6, International Civil Servant)

Informed consent was discussed as a potential entry point for communicating with researchers the importance of rights integration, in that even if they are unfamiliar with how to integrate rights into their work, they are aware of the importance of informed consent processes.

“One of the key things is informed consent. Regardless of if the research is biomedical or qualitative, this is the human rights aspect that most of the researchers try to cover also in terms of confidentiality, giving information, etc. Maybe this is a starting point where you can connect with all of them [the researchers]. Informed consent could be the common ground.” (KII10, International Civil Servant)

One key informant, an international civil servant, suggested a methodology to help researchers conceptualise a three-tiered approach to rights in developing their research statement: including attention to contextual factors, the questions to be asked, and the population to be addressed, as a way to explicitly incorporate rights in ways that can impact all aspects of the research. It was noted that this would help researchers to think more broadly than research ethics by bringing attention to the larger contextual factors or environment where the research will take place.

Key informants suggested a variety of approaches as to how to take the integration of rights in research forward. Respondents discussed important considerations including tools, products and approaches including a checklist, trainings, and changes to university curricula and funding requirements by donors.