- Visit the AAUP Foundation

- Visit the AFT

Secondary menu

Search form.

Member Login Join/Rejoin Renew Membership

- Constitution

- Elected Leaders

- Find a Chapter

- State Conferences

- AAUP/AFT Affiliation

- Biennial Meeting

- Academic Freedom

- Shared Governance

- Chapter Organizing

- Collective Bargaining

- Summer Institute

- Legal Program

- Government Relations

- New Deal for Higher Ed

- For AFT Higher Ed Members

- Faculty Compensation

- Political Interference in Higher Ed

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Responding to Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Free Speech on Campus

- Bulletin of the AAUP

- The Redbook

- Journal of Academic Freedom

- Academe Blog

- AAUP in the News

- AAUP Updates

- Join Our Email List

- Join/Rejoin

- Renew Membership

- Member Benefits

- Cancel Membership

- Start a Chapter

- Support Your Union

- AAUP Shirts and Gear

- Brochures and More

- Resources For All Chapters

- For Union Chapters

- For Advocacy Chapters

- Forming a Union Chapter

- Chapter Responsibilities

- Chapter Profiles

- AAUP At-Large Chapter

- AAUP Local 6741 of the AFT

You are here

Recognizing the reality of working college students.

When academically qualified people do not have the financial resources needed to enroll and succeed in college, higher education fails to fulfill the promise of promoting social mobility—and may actually serve to reinforce social inequities. The cost of college attendance is rising faster than family incomes, and increases in federal, state, and institutional grants have been insufficient to meet all students’ demonstrated financial needs. Between 2008–09 and 2017–18, average tuition and fees increased in constant dollars by 36 percent at public four-year institutions and 34 percent at public two-year institutions, while median family income rose by only 8 percent . The maximum federal Pell Grant covered 60 percent of tuition and fees at public four-year institutions in 2018–19, down from 92 percent in 1998–99. Full-time, dependent undergraduate students in the lowest family-income quartile averaged $9,143 in unmet financial need in 2016, up 149 percent (in constant dollars) from $3,665 in 1990.

Students who do not have sufficient savings, wealth, or access to other financial resources have few options for paying costs that are not covered by grants: they can take on loans, get a job, or do both. While these options pay off for many students, a higher education finance system that requires the use of loans and paid employment disproportionately disadvantages individuals from groups that continue to be underrepresented in and underserved by higher education.

Growth in student loan debt is well documented. As of the second quarter of 2019, total outstanding student loan debt in the United States exceeded $1.6 trillion and represented the largest source of nonhousing debt for American households. Annual total borrowing among undergraduate and graduate students from federal and nonfederal sources increased 101 percent (by $53 billion) in constant dollars from 1998–99 to 2018–19 .

Many individuals who use loans to pay college costs complete their educational programs, obtain jobs with sufficiently high earnings, and repay their loans. But the implications of borrowing vary across groups and are especially problematic for students who do not complete their degree. The Institute for College Access and Success reports lower loan repayment rates for Pell Grant recipients, first-generation students, and black and Hispanic students as well as for students who attend for-profit institutions. Black students also average higher rates and amounts of federal loans and experience higher default rates .

Like taking on loans, working for pay can have benefits. Paid employment can provide students with money they need to stay enrolled, and it can build human capital and improve labor-market outcomes. An exploratory study by Anne-Marie Nuñez and Vanessa A. Sansone found that first-generation Latinx students developed new relationships, skills, and knowledge through work and experienced satisfaction and enjoyment from working. But working can also have harmful consequences. And, as with loans, the negative implications of paid employment are more commonly experienced by students from underserved and underrepresented groups.

The circumstances of working students today can undermine the mission of higher education for multiple reasons.

1. Many undergraduates are working more than twenty hours per week.

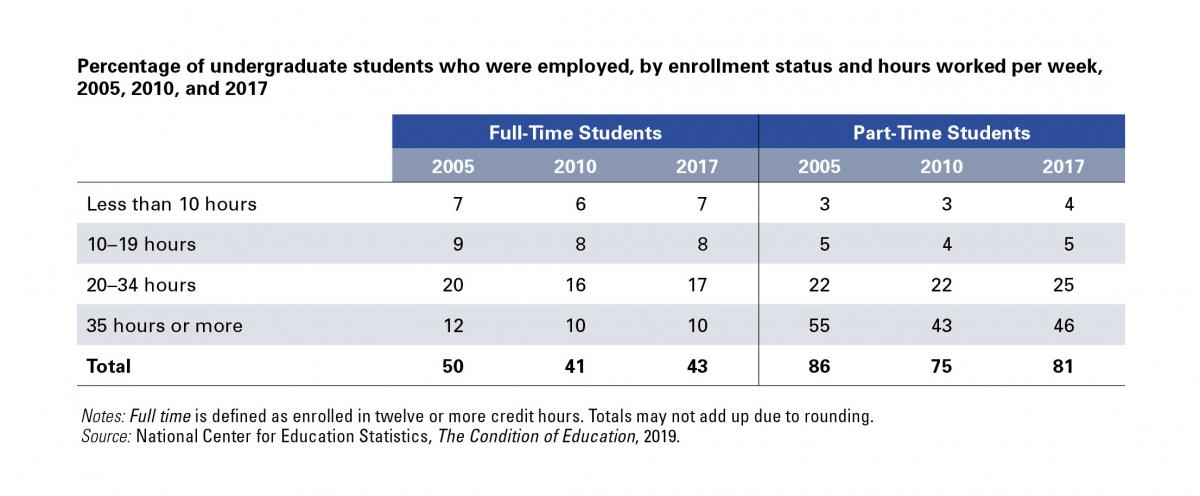

The US Department of Education reported that, in 2017, 43 percent of all full-time undergraduate students and 81 percent of part-time students were employed while enrolled (see table). The proportion of full-time students working for pay was higher in 2017 than in 2010, when 41 percent were employed, but lower than in 2005, when 50 percent worked for pay while enrolled. Employment rates for part-time students follow a similar fluctuating pattern: 86 percent in 2005, 75 percent in 2010, and 81 percent in 2017. In all, more than 11.4 million undergraduate students (58 percent) worked for pay while enrolled in 2017.

2. Working for pay is more common among undergraduates from underserved groups.

The financial need to work while enrolled, with all its negative consequences, disproportionately burdens students from historically underserved groups. While students from all family backgrounds work for pay, students from low-income families are more likely to do so—and, among those who are employed, work more hours on average—than their higher-income peers. The US Department of Education reports that, in 2017, 16 percent of black full-time students and 13 percent of Hispanic full-time students worked at least thirty-five hours per week while enrolled, compared with 9 percent of white full-time students.

Students who are classified as independent for financial aid purposes more commonly work for pay while enrolled than students who are classified as financially dependent (69 percent versus 59 percent in 2015–16, according to our analysis of 2016 NPSAS data). Working undergraduates who are independent also average more hours of work per week than working-dependent undergraduates (33.8 versus 22.1). Among working students, nearly three quarters (71 percent) of those who were also single parents with a dependent child worked thirty or more hours per week in 2016, compared with 50 percent of all working students.

3. Working for pay while enrolled is more common at under-resourced institutions.

The rate of employment and the rate of working more than twenty hours per week are higher among full-time students attending two-year institutions than among those attending four-year institutions. In 2017, 50 percent of full-time students at two-year institutions worked, and 72 percent of these working students worked more than twenty hours per week, according to the US Department of Education . By comparison, 41 percent of full-time students at four-year institutions worked; 60 percent of these students worked at least twenty hours per week.

Two-year institutions, as well as for-profit and less selective four-year institutions , enroll higher shares of students from low-income families. The Center for Community College Student Engagement reported that nearly half (46 percent) of Pell Grant recipients attending public two-year colleges in 2017 worked more than twenty hours per week.

4. Working while enrolled can be harmful to student outcomes.

Working can have costs, as time spent working reduces time available for educational activities. Research has shown that working more than twenty hours per week is associated with lower grades and retention rates. Studies also show that working may slow the rate of credit-hour accumulation, encourage part-time rather than full-time enrollment, and reduce the likelihood of completing a bachelor’s degree within six years. These outcomes lengthen the time to degree, which can increase opportunity and other college costs. Reducing enrollment to less than half time reduces eligibility for federal Pell Grants and other aid. And the need to allocate time to paid employment may create stress, especially for students who are also parents or other caregivers. A disproportionate share of single parents enrolled in college are black and American Indian women.

5. Students from low-income families and other underserved groups are less likely to have jobs that advance career-related knowledge and skills.

While any employment may improve conscientiousness, teamwork, and other occupational skills, not all jobs will advance career-related knowledge and skills . About a quarter (26 percent) of working students under the age of thirty held a job in the food and personal services industries in 2012, according to data in Learning While Earning , a report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce; only 6 percent held managerial positions. In addition to working more hours on average than their higher-income peers, students from lower-income families are also less likely to have paid internships or other positions related to their career goals.

In a 2016 study , Judith Scott-Clayton and Veronica Minaya of Columbia University found that students with on-campus work locations and major- or career-related positions had higher rates of bachelor’s degree completion than students with other employment. Yet students from lower-income families and other underserved groups are less likely to hold on-campus and major-related jobs.

Ensuring that Work “Works”

Higher rates and intensity of employment among students from underserved backgrounds and those attending under-resourced institutions suggest that employment during college is serving to reinforce inequity in higher education opportunity, experiences, and outcomes. Changes in public policy and institutional practice are needed if higher education is to address these inequities. These efforts should focus on reducing the financial need to work and on minimizing the harm, while maximizing the benefits, of work.

Reducing the Need to Work

Even with current levels of employment, many students are struggling to make ends meet. In the 2015 National Survey of Student Engagement , most seniors at four-year institutions (63 percent) reported being “worried about having enough money” and half (48 percent) reported that they “did not participate in [unspecified] activities due to lack of money.” Reports of financial stress were more common among first-generation, black, and Hispanic students and among students over the age of twenty-four. More than a third (38 percent) of Pell Grant recipients at community colleges who worked more than twenty hours per week reported “running out of money” at least six times in a year, even though 46 percent worked more than twenty hours per week, according to the Center for Community College Student Engagement ; only 22 percent reported having access to cash, credit, or other sources of funds for an “unexpected need.”

The following strategies may help to reduce students’ financial need to work more than twenty hours per week, while still ensuring that they have the financial resources needed to enroll, engage, and persist to degree completion.

1. Reduce unmet financial need.

Federal, state, and local public policy makers can reduce unmet financial need by appropriating more resources to institutions, which can then be used to keep tuition low, and allocate more need-based grant aid. Institutional leaders can reduce unmet financial need by maximizing the availability of need-based grant aid, limiting merit-based grant aid, and controlling costs. Offering additional need-based aid to low-income students has been shown to reduce employment rates and number of hours worked and increase the likelihood of on-time degree completion .

2. Do not penalize students who work for pay in financial aid calculations .

Students should work to cover their own contribution to the Expected Family Contribution, as well as unanticipated costs that arise while enrolled. Student earnings from work should not be viewed as a way to cover costs that are omitted from an institution’s official cost of attendance or for covering unmet need. Working should provide a mechanism for paying unanticipated costs without influencing the availability of resources to pay the costs needed to stay enrolled.

3. Help students make individually appropriate decisions about federal loans and work.

Whether because of risk or loan aversion or because of incomplete or inaccurate information, some students do not use federal loans. Higher rates of loan aversion have been observed among men and Hispanic students . K–12 and higher education counselors and administrators should educate students, especially those from underserved groups, about the costs and benefits of paid employment and different types of loans and discuss how working more than twenty hours per week may increase time to degree, reduce the likelihood of completion, and result in other costs.

4. Ensure that students apply for and receive the need-based grant aid for which they are eligible.

Not all students who are eligible for need-based aid apply for and receive the aid. In 2011–12, in part because of a lack of clear information, approximately 20 percent of all undergraduates , and 16 percent of those with incomes below $30,000 , did not file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), a condition for receiving most federal and state need-based aid. The Institute for College Access and Success reports FAFSA verification may also limit aid receipt and enrollment, especially for low-income students.

Minimizing Harm, Maximizing Benefits

Colleges and universities should also act to minimize the harm and maximize the benefits of working. The following strategies may help.

1. Increase the availability of on-campus and major-related employment.

Institutions should identify on-campus employment opportunities for students that are related to their major field and provide opportunities to build career-related knowledge and skills. Descriptive analyses suggest that academic outcomes are better for students who are employed on campus rather than off campus.

2. Ensure that high-quality academic and other supports are available to working students.

Creating an institutional environment that promotes success for working students requires a campus-wide effort. Observers have recommended that institutions support working students by offering courses in the evenings, on weekends, and online; making available future course schedules; offering access to academic advising, office hours, and other support services at night and on weekends; offering online course registration and virtual academic advising; providing child-care options; and designating space for working students to study. Institutions may also connect employment and educational experiences through career counseling and occupational placement.

3. Recognize differences in employment-related needs and experiences.

Institutions should also recognize differences in the supports needed by different groups of working students, as, for example, the experiences, needs, and goals of working adult part-time students are different from those of working full-time students who are still dependents. The Learning While Earning report recommends that institutions develop collaborations with area employers in order to provide adult working students with “convenient learning options; child care; affordable transportation options; employment partnership agreements; access to healthcare insurance; paid sick, maternity, and paternity leave; financial literacy and wealth building information and retirement and investment options; and tuition assistance.”

Colleges and universities, especially those that enroll high shares of working adults, should also consider mechanisms for awarding credit for work and other prior experiences. These mechanisms include the College Board’s College-Level Examination Program and the American Council on Education’s College Credit Recommendation Service.

Employment during college too often contributes to inequity in higher education opportunity, experiences, and outcomes. More can and should be done to ensure that all students—especially students who must work for pay while enrolled—can fully engage in the academic experience, realize the potential benefits of working, and make timely progress to degree completion.

Laura W. Perna is GSE Centennial Presidential Professor of Education and executive director of the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (AHEAD) at the University of Pennsylvania. Her recent publications include Improving Research-Based Knowledge of College Promise Programs (2019, with Edward Smith) and Taking It to the Streets: The Role of Scholarship in Advocacy and Advocacy in Scholarship (2018) . Her email address is [email protected] . Taylor K. Odle is a PhD student in higher education in Penn’s Graduate School of Education and an AM candidate in statistics at the Wharton School. He was previously assistant director for fiscal policy and research at the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. His email address is [email protected] .

ADVERTISEMENT

American Association of University Professors 555 New Jersey Ave NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20001 Phone: 202-737-5900

[email protected], privacy policy & terms of use.

The Hard Working Student: a research study

“what does being a working student mean to me”: a reflection on my experiences.

August, 2020

By: Sara Sanabria

My name is Sara Sanabria and for the past two years I have been a research assistant for the Hard-Working Student study. As mentioned in the ‘About’ page, the study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the experiences of working students. As we ask students tough questions regarding balancing work and studies, I too have had an opportunity to reflect on what it means to be a working student. And while being a working student means very different things to different people, I decided to end my time with the study by sharing some insights on what being a working student means to me.

One of the things I realized is that working while studying means having a place to escape from school and life’s stresses. By having a time and a place to sit down and focus on something completely unrelated to my classes, I can take a mental and emotional break from constantly thinking about assignments and papers. In the long run it helps me to avoid burn out and to stay passionate about what I am studying.

Another thing I have come to realize about being a working student, is that many working students see their work as temporary. This was definitely the case for me when I worked in the retail and service industry. I saw my job as something I did on the side for money, and I always went into a job knowing that I would eventually leave it. Consequently, I usually took on a ‘put your head down and work hard’ mentality and accepted mistreatment or poor working conditions because I figured, “what’s the point in demanding better from my employer if I’ll be gone in a few months?” So, I accepted conditions that led to mild skin burns, long hours with no breaks, having my hours cut with little notice, and more. During my time with the HWS study, we organized a ‘Rights at Work’ event, and to my surprise, I discovered that there are support systems for working students such as worker’s unions and legal protections. However, I also learned that working students typically do not participate in unions because again, a lot of us see our term-time work as temporary. In the future I hope to be more assertive and to stand up for safe and fair working conditions for myself and my co-workers.

Lastly, as I head into law school and start a new job search in a new city, I reflect on how working while studying means having a sense of financial stability and how important it is for me to have a source of income while I study. I am privileged to have some support from my parents and the school, but even so, I know that without working it will be difficult to make ends meet. I know this is a reality for many students and so I share a sense of solidarity with others who are working hard to make a brighter future themselves. I am thankful to have been part of this study as I am certain it will go on to inform future policy and hopefully make a positive impact for other hard-working students.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Spam prevention powered by Akismet

Working While Studying: Pros and Cons Essay

Modern students seek financial independence and opportunities to receive practical skills from an early age. Nowadays more than 57% of students worldwide work part-time to cover their living and tuition costs as well as to satisfy some higher personal demands (Richmond par.1).

Working while studying helps students to realize their potential and develop crucial professional skills. Only in the working environment, it is possible to gain invaluable practical experience and knowledge. Apart from financial rewards, students receive necessary team-working, organizational, planning, time-management, leadership, and decision-making skills. They learn how to deal with real situations, take full responsibility for their actions, and efficiently interact with their colleagues.

A person who is engaged in a busy working environment also develops interpersonal, communicational, and conflict handling skills (Department for Business, Innovation, and Skills 79). Moreover, employers are more favorable to those who already have working experience after graduation, especially if to speak about relatively prestigious positions (Wignall 21).

At the same time, working while studying entails many challenges. A student will face pressure and need to achieve the balance between work and studying process. The quality of his or her studies might deteriorate significantly, as well as social life. A working person faces the risk of nervousness and tiredness, which may affect his or her ability to retain and process information at the University. In some cases, over-exhaustion may even lead to health problems (Department for Business, Innovation, and Skills 78).

Thus, it is up to the student to decide whether he or she can combine studies with working. Working while studying might be exhausting and stressful, but it brings significant benefits to young people and facilitates their finding in the modern economically unstable world.

Works Cited

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 2013. Working While Studying: A Follow-up to the Student Income and Expenditure Survey 2011/12 . Web.

Richmond, Leone. Student Part-time Work Increases . 2013. Web.

Wignall, Alice. The Guardian Postgraduate Guide . London, UK: Guardian, 2012. Print.

- Career Plan for a Realtor Agent

- Interest Profiler and Career Development

- College Tuition Should Not Rise

- Tuition: Is Higher Education Easily Accessible?

- Tuition Increases and Financial Aid in California

- The Transition From School to Work

- Personal Career Plan: A Vision Statement

- MBA in International Business and Investment Management

- Multiple Career Choices in Biosciences

- Master of Business Administration and Its Benefits

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, March 30). Working While Studying: Pros and Cons. https://ivypanda.com/essays/working-while-studying-pros-and-cons/

"Working While Studying: Pros and Cons." IvyPanda , 30 Mar. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/working-while-studying-pros-and-cons/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Working While Studying: Pros and Cons'. 30 March.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Working While Studying: Pros and Cons." March 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/working-while-studying-pros-and-cons/.

1. IvyPanda . "Working While Studying: Pros and Cons." March 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/working-while-studying-pros-and-cons/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Working While Studying: Pros and Cons." March 30, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/working-while-studying-pros-and-cons/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Time Management for Working Students

Ann Logsdon is a school psychologist specializing in helping parents and teachers support students with a range of educational and developmental disabilities.

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Image Source / Getty Images

- Procrastination

At a Glance

If you are working and going to school, time management will be key to making sure you can meet your goals as an employee and a student.

Students who are also doing work at a job—either to put themselves through college or because they’re going back to school after entering the workforce—often find it hard to juggle everything they need to do in a day.

Time management is key if you’re a working student. It can feel overwhelming, but there are some practical steps you can take to balance your school and work responsibilities.

Let’s talk about time management for students who are also working, including some tips for achieving your goals.

Before you can start planning to get things done, you need a clear idea of what you need to do. You also need to have a sense of the order in which you should tackle the tasks you need to complete.

Start by making a list of everything that needs to be done. Be prepared for it to be long and intimidating at first—but don’t worry, we’ll organize it and break it down later.

Look at the list and note any items that have a due date. For example, is there training at work you have to finish by the end of the month? Do you have a research paper due next Tuesday?

Put the tasks that need to be done soonest at the top. Once you’ve got all the high-priority items in place, look at the items that don’t have a firm “due date” but more of a suggested timeline.

For example, you may not have to get laundry done on a certain day, but you want clean sheets once a week. You may not need to go to the grocery store on Monday, but you will need to get groceries by the end of the week.

Do you have some lower-priority items left over? For example, maybe a hobby or a novel you’d like to get back to? Keep them on a side list that you can skim and fit in when you have time.

Be Ready to Say No

If you’ve got a full list of things to do and many of them are top priorities, keep in mind that you may not be able to take on anything else. If someone asks you to do something or an opportunity comes up, be prepared to say no—or at least “not right now.”

Make a Schedule

Probably the first time management tip anyone would give you is to make a schedule and stick to it. Why? It works! It seems obvious and simple, but a schedule is one of the most straightforward ways to manage your time.

When you think about the day ahead but don’t make concrete plans, you risk forgetting something, misplacing your priorities, or getting so overwhelmed by your to-do list that you just do nothing. Don’t underestimate the power of having a schedule to guide you through your busy days. Order is key for managing time, and a schedule helps get your life in order.

Start by writing out your day in 30-minute chunks. First, fill in all the events that are not flexible, like class times and work. Think about your priority items and fit them in first.

When those times are marked, you’ll be able to see what other time is available for other tasks like studying and taking care of responsibilities at home (here’s where you can work on laundry day and grocery shopping).

Use Downtime to Recharge

When you're planning your time, remember that you also need time to unwind and relax , maybe by watching an episode of your favorite show or taking a long bath. Making time to decompress and de-stress is important to avoid burnout .

You'll also have to accept that sometimes your downtime may have to be cut short. You only have so many hours in a day. When you’re overly stressed, you may want to lean more heavily into self-care—but instead of using it to shore up your reserves, you’re turning to it as an escape.

For example, if you’ve been working and studying all day, reading a chapter or two of a book for fun as you get ready for bed would be making time for self-care. On the other hand, if you binge-watch an entire season of your favorite show because you’re too overwhelmed to start writing a paper you’ve been putting off for a week, that’s avoidance.

You don’t have to take an “all-or-nothing” approach. You just need to balance the restorative power of stress-relieving activities with meeting your responsibilities.

Taking a short break can help you refocus. When you come back to your work, you might even be more productive. But resisting the urge to always choose a “fun” pursuit over the more challenging things you need to do requires self-discipline.

Being able to balance work, play, and rest is key to achieving your goals, but it takes practice and honesty. You need to tune into your needs but also be real with yourself about whether a break will help you or if it’s just a way for you to justify not doing something you don’t want to do.

Try Not to Procrastinate

Whether you’re putting off writing a research paper or doing a required (but boring) training for work, procrastination is something that even the most motivated and well-organized people do.

When you’re thinking about all the things you have to do, maybe you tend to see every single step along the way. Not surprisingly, it all starts to look like too much, and you get overwhelmed and just do nothing. Then, as you start thinking about all the stuff you have to do that you’re not doing, the anxiety sets in.

But instead of getting started on the task, you just keep putting it off. And then you feel guilty. Maybe you even start doing other things that aren’t even on your big to-do list just to feel like you’re doing something. To relieve the guilt you feel about putting a task off, you do other stuff (like household chores) to make it seem like you are accomplishing something.

Sound familiar? Procrastination might be common, but it’s not helpful. It can make it harder to manage your time effectively.

If you feel procrastination seeping in, you'll have to get real with yourself about the consequences of it. While it might feel better in the moment to free yourself from a task, you’re just making the “later” pile bigger. The truth is, if you’ve broken up a big goal into smaller tasks, the time it takes you to “do the thing” is often much shorter than you think. Once you've started, you’ll feel relief at getting it done.

It can also help to think more creatively about the task. For example, does the order of your to-do list matter? Could you shake up some tasks so there’s a little more variety? For example, could you do a few work tasks first, then do some coursework, then do some chores?

If you’ve got a laptop, tablet, and/or smartphone, you’ve already got a lot of tools to help you manage your time. There are apps and programs for everything—from scheduling and setting goals and reminders to enforcing productivity and reducing procrastination.

Here are just a few examples of tools you can use:

- Calendars are built into just about any device and can even sync between all your devices. You can track assignment due dates and study sessions and set up notifications and reminders. If you prefer writing things down, a physical desk calendar or planner can still have a digital counterpart—just scan the month or take a photo so you always have it on hand.

- Timers can be a big help if you tend to either stare at the clock and wish it would move faster or get so wrapped up in something that hours pass and it feels like seconds. Setting a timer can help you make sure you’re staying on track to finish a task in the time you have, as well as make sure that you’re taking breaks.

- You can download programs, browser extensions, and apps that make it harder to procrastinate. For example, you may want to block social media for a set amount of time when you need to work. That way, even if you can’t resist the urge to check (or just are in the habit of doing it mindlessly), you’re prevented from engaging with the time-suck.

- Journals and apps that help you track progress can help you stay motivated and give you a visual sense of how close you are to meeting your goals. It’s also a place where you can vent, work through the stressful feelings you’re having, and possibly even uncover some triggers and trends. You might be able to adjust your time management strategy based on what you learn about yourself.

Aeon B, Faber A, Panaccio A. Does time management work? A meta-analysis . PLoS One . 2021;16(1):e0245066. Published 2021 Jan 11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245066

Hamid A, Eissa MA. The effectiveness of time management strategies instruction on students’ academic time management and academic self efficacy . Online Submission . 2015;4(1):43-50.

McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning. Principles of effective time management for balance, well-being, and success .

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry . 2016;15(2):103–111. doi:10.1002/wps.20311

Boniwell I, Osin E, Sircova A. Introducing time perspective coaching: A new approach to improve time management and enhance well-being. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring . 2014 Aug;12(2):24.

Rozental A, Forsström D, Hussoon A, Klingsieck KB. Procrastination among university students: differentiating severe cases in need of support from less severe cases . Front Psychol . 2022;13:783570. Published 2022 Mar 15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.783570

By Ann Logsdon Ann Logsdon is a school psychologist specializing in helping parents and teachers support students with a range of educational and developmental disabilities.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

More can and should be done to ensure that all students—especially students who must work for pay while enrolled—can fully engage in the academic experience, realize the potential benefits of working, and make timely progress to degree completion.

By having a time and a place to sit down and focus on something completely unrelated to my classes, I can take a mental and emotional break from constantly thinking about assignments and papers. In the long run it helps me to avoid burn out and to stay passionate about what I am studying.

The duties and responsibilities of a working student have various positive and negative effects when it comes to their academic studies, behavioural status, and also on how they pursue their goals and dreams in life by also inspiring others as well as to those whose parents are working abroad.

the study examines the difference between working and nonworking students in their academic and social experience on campus, students’ perceptions of work, and the impact of work on their college life. The results indicate no significant difference between working and nonworking students in their academic and social experience, though

Working while studying helps students to realize their potential and develop crucial professional skills. Only in the working environment, it is possible to gain invaluable practical experience and knowledge.

Time management is key if you’re a working student. It can feel overwhelming, but there are some practical steps you can take to balance your school and work responsibilities. Let’s talk about time management for students who are also working, including some tips for achieving your goals.