Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Jewish Question - Fyodor Dostoevsky

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

12 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by BeltAndRoad# on January 6, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

“The Jewish Question: History of a Marxist Debate” – a review

Enzo Traverso’s The Jewish Question: History of a Marxist Debate was first published in French in 1990.

In this updated and completely revised second edition, Enzo Traverso carefully reconstructs the intellectual debate surrounding the “Jewish Question’ over a century of Marxist thought.

Reviewed here by Deborah Maccoby, it is published by Haymarket Books and is available in the UK at a reduced price of £11.99 from Blackwell’s (delivery free).

The Jewish Question: History of a Marxist Debate ,

Enzo Traverso, 2nd Edition, Haymarket Books, 2019, 221pp.

Reviewed by Deborah Maccoby

Like the Talmud, this book is a record of arguments: a debate not between rabbis in the first centuries CE but between Marxists – most of them Jewish – in Central and Eastern Europe between 1843 and 1942. Traverso’s The Jewish Question was first published in 1990; this is the second edition, with a new Preface and an additional chapter called “Post-War Marxism and the Holocaust”.

The original near-century timespan divides Karl Marx’s essay “On the Jewish Question”, written in 1843, from Abram Leon’s book The Jewish Question, completed in 1942. And the specific area is chosen for the reason that it was essentially only in Central and Eastern Europe that an internal Marxist debate developed around “the Jewish Question”. Traverso argues that in France debates between Socialists on the subject were “outside Marxism”, instead being part of the opposition between Socialists and anti-Semitic nationalists. And in the United States, Traverso writes, the immigrant working class was still so multinational that there were no problems with a specific Jewish Socialism; hence no debate.

The debate centred on one issue: assimilation. As the inheritors of the Enlightenment, many Marxists believed, in common with many Enlightenment thinkers, that the ultimate goal of the liberation of Jews from discrimination and persecution was the disappearance of Judaism and of the Jews as a people – both considered as a kind of fossilised relic. In fact, the tendency of the classical Marxism portrayed in this book was to view the Jews not in terms of religion and culture at all, but rather as an economic caste.

Traverso begins with Marx’s definition of Jews in 1843 as “Geldmenschen” (“men of money”), whose secular religion was money – a religion that, Marx argued in this essay, had become the basis of bourgeois society in general, so that liberation of society from the domination of money would mean the “real self-emancipation of our time” – i.e. the disappearance of Jews into universal humanity. Traverso argues against the accusation that Marx was an antisemitic self-hater, pointing out that “On the Jewish Question” was a work of Marx’s immaturity; it does not reflect his mature thinking. Marx’s 1843 essay, Traverso argues, should also be seen in historical context; he quotes Hannah Arendt, who wrote that “On the Jewish Question” could only be understood in the light of the conflict between emergent “pariah” Jewish intellectuals such as Marx and Heine and the rich bankers – the “Court Jews”– who still survived as a group at that time; Marx’s attack was really aimed at the “Court Jews”.

Nonetheless, in later chapters, Traverso traces the influence of Marx’s youthful essay on later Marxist concepts of the Jews – concepts that tended towards the perception of Jews as an economic caste. The ultimate expression of this tendency (though blended with contrary opinions) was Abram Leon’s book The Jewish Question. Leon described the Jews as a “people-class”, which had played its real economic part in society before the rise of capitalism, as merchants and later (after the emergence of a Christian merchant bourgeoisie that displaced the Jews) as usurers. Leon argued that the Jews’ economic usefulness had become outdated; as a result, many Western Jews were in the process of assimilating. But, in Traverso’s summing –up of Leon’s thesis:

“The Jews of the East remained caught between feudalism in decomposition and decadent capitalism….they remained attached to a historically doomed economic function and they could no longer integrate themselves into society. It was this contradiction that produced modern anti-Semitism, transforming the Jews into scapegoats for the economic crisis. This also happened in the West, where the global crisis of capitalism gave a new boost to anti-Semitism; the Nazi regime turned the anti-capitalist hatred of the pauperised petty bourgeoisie against the Jews.”

Traverso strongly criticises Leon’s theory of the “people-class”, pointing out that it is only relevant to Jewish history from the eleventh century CE onwards in Christian Europe, whereas Leon “conceived it as a universal paradigm and projected it on to the entire history of the Jewish Diaspora”. Citing various critiques of the theory, Traverso concludes: “The theory of the people-class fatally appears both mono-causal and inspired with a form of economic determinism”. In his concluding chapter, he writes that “the Jewish Question reveals the blindness of Marxists to the significance of both the religion and the nation in the modern world”. And he points out that perceiving anti-Semitism only in economic terms also blinded Marxists to the real nature of Nazism.

But the book is of course a record of a debate; and, as well as tracing the main Marxist current on the Jewish Question, Traverso focuses on the opposition. In Eastern Europe, most Jews throughout the 1843-1942 period, unlike those in Central Europe, experienced persecution and isolation – with the result that a strong sense of secular national identity developed among many Jewish Marxists. Traverso calls these Marxist Jews “Judeo-Marxists”, to distinguish them from the Jewish Marxists who subscribed to the assimilationist side of the debate. But the Judeo-Marxists had their own internal debate, between the Bund – Jewish Marxists who formed an extra-territorial, Yiddish-speaking secular national identity within Eastern European Marxism — and Zionists, who wanted to forge a Jewish nation in Palestine. Traverso points out that Zionism – which could not provide any real answer to the Jewish Question — was itself a form of assimilation; its central aim was to “normalise” the Jews by making them like all other peoples. And Traverso writes that “Socialist Zionism did not escape the blind alley of European colonialism”; in their turn, Marxist Zionists required the assimilation of the Palestinian Arabs.

On the central debate between the assimilationists and the Judeo-Marxists, Traverso quotes Vladimir Medem, the theoretician of the Bund, criticising “the abstract internationalism of the Bolsheviks” with particular reference at the end to Lenin:

“In order to attract the working-class, the internationalist ideas need to be adapted to the language spoken by the workers and to the concrete national conditions in which they live. Workers should not be indifferent to the conditions and the development of their national culture, for it is only through it that they can participate in the internationalist culture of democracy and the world socialist movement. It is obvious, but V[ladimir] I[lyich] turns a blind eye to all of this”.

This lesson is extremely topical in view of the recent British General Election, in which a right-wing Brexiteer Tory Party in England and Wales and the Scottish National Party in Scotland swept the board. In England and Wales, in my view, the left was defeated mainly because it did not take sufficiently into account the “national culture” of the working-class.

Another opponent of the assimilationists was Walter Benjamin, to whom Traverso devotes a fascinating chapter, explaining his unique, romantic synthesis of Judaism (in particular the Jewish mystical and Messianic tradition), German culture and Marxism. In the other parts of the book, Traverso depicts such a dazzling array of characters and arguments that he doesn’t manage to go into any one thinker in depth, the result being at times too rapid and complex; but here he achieves his own in-depth synthesis of the personal and the intellectual (as he does in the chapter devoted to Abram Leon).

Both Benjamin and Leon died in the Holocaust; Benjamin committed suicide at the Spanish frontier in 1940; while Leon was murdered in Auschwitz at the age of 26 ( The Jewish Question was completed when he was 24). In the penultimate chapter, added for the second edition, Traverso discusses various attempts by Marxist thinkers, such as the Frankfurt School, to explain the Holocaust. He concludes that all these Marxist theorists “had abandoned any illusion of historical teleology”; i.e. the Marxist belief – inherited from the Enlightenment – in “the idea of progress in which history was envisaged as a linear development….. the development of productive forces under capitalism growing inevitably closer to the advent of the socialist order”. As Traverso puts it: “the Holocaust demonstrated that economic advancement and technological progress….could be a march towards catastrophe”.

Convincing though Traverso’s critique is of the “abstract internationalism” and economic reductionism of the assimilationists, he seems to me to go too far in the direction of particularity. Despite his discussion of the Jewish Messianism of Walter Benjamin, Traverso never brings out the Jewish dialectical paradox of being a separate nation that is dedicated to universalism – i.e. to the idea of One God and to the indestructible, eternal and universal values that this concept represents. This is surely the central reason for the survival of the Jews as a people for two thousand years; and this surely also helps to explain why so many Jews were attracted to the internationalism of Marxism (Traverso’s view of Judaism as a particularist religion seems to lie behind his dismissal – which I find unconvincing — of the idea that Marx was fundamentally, even if unconsciously, influenced by his Jewish heritage.) Citing Maxime Rodinson, Traverso writes:

“In the Diaspora, Yahweh remained the God of Israel, identified with a people , and it was not possible to participate in his cult without belonging at the same time to his people. In Rodinson’s words: ‘the conjunction in Judaism of religious and ethnic particularisms, inside pluralist societies of weak unifying force, ensured its survival’.” (Italics in original).

As a great monotheistic religion that gave rise to two other great monotheistic religions, Christianity and Islam, Judaism is surely more than a “cult” (and the name “Yahweh” sounds like a primitive tribal god).

Traverso seems at the end to put his faith in “identity politics” as a substitute for the failed illusions of Marxism. He ignores the controversial nature of “identity politics” that has been pointed out by many critics of the UK’s multiculturalism model: the dangers of social division and fragmentation, as everyone divides into rival oppressed groups. And it is never possible to resolve who within them has the right to speak on behalf of the various oppressed groups. The Board of Deputies has recently provided an excellent illustration of this problem by demanding that the Labour Party “engage with the Jewish community via its main representative groups and not through fringe organisations and individuals”.

But even by disagreeing with Traverso I am entering into the argument that this book stimulates in the reader. This is a rich, complex, fascinating, if at times difficult, intellectual history that brings to life an old debate that is still very topical and relevant today.

Comments (3)

” … in my view, the left was defeated mainly because it did not take sufficiently into account the “national culture” of the working-class.”

I leave aside the main issues raised in this article just to note how, post-election, every interest group is using Labour’s defeat to fly their own flag over the debris.

Actually the truth is that, above all, it’s not over-complicated to find an over-arching truth . Not this time ‘It’s the economy, stupid’, but that :

“It’s the media, stupid”

Response to RH. Not sure if this has anything to do with the above article. Yes, the media played a part. But Brexit divided everyone, political parties, families, communities etc.

[JVL web editor writes: please do not use this book review as the place to have an extended debate about Brexit. It was mentioned in passing in the review and the author is being given this chance to reply. The review was about so many other things besides!]

On the question of how far Labour’s Brexit policy contributed to Labour’s defeat, I recommend this article by Edmund Griffiths:

http://www.edmundgriffiths.com/brexitwqwa.html

Comments are now closed.

Related Articles

A queer jew for palestine…, retrying the dreyfus case, france flirts with a jewish candidate’s antisemitism, the internationalism of rosa luxemburg, abraham joshua heschel – an appreciation, jewish socialist magazine – new issue now out, the masses against the masses, the universal message of passover.

Welcome to our new website! We're excited to see you. *** RETURNING USERS WILL NEED TO RESET THEIR PASSWORD FOR THIS NEW SITE. CLICK HERE TO RESET YOUR PASSWORD.*** Close this alert

Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945

Description.

Most people today are vaguely aware of "issues" with Jews in contemporary society. But generally speaking, few have any deeper awareness of the pervasive and detrimental role that they play throughout the West. And fewer still understand the history and the context of what has long been known as "the Jewish Question"-namely: How should non-Jews deal with this most pernicious minority in their midst?

The Jewish Question goes back centuries, at least to ancient Rome. The Romans were the first Western power to encounter the Judean Hebrews, to defeat them, and to scatter them throughout the world. Unfortunately, Roman victory proved temporary; with the collapse of the Empire in 395 AD, Jews and Judeo-Christianity took hold in Europe. They are yet to relinquish their grip.

Throughout the Christian era, Jews steadily gained in wealth and power. By the mid-1800s, they were achieving full civil rights in European countries, and their wealth was beginning to distort the social fabric. This led many observers to begin commenting, often harshly, on the negative Jewish presence in society. From such well-known figures as Richard Wagner and Fyodor Dostoyevsky to virtual unknowns like Frederick Millingen and Wilhelm Marr, shocking stories began to emerge. Into the National Socialist era, a number of Germans, including Theodor Fritsch, Adolf Hitler, and Heinrich Himmler, took a very hard line against the Jewish intruders. Their words are potent and compelling.

Now, for the first time, 16 classic essays are compiled into a single volume. These essays are difficult to find, even in the Internet age. When found, they are typically incomplete. When found complete, they are poorly translated and edited. As a result, it is nearly impossible to obtain a deep understanding of the Jewish Question over the past century and a half. The aim of the present book is to alleviate this shortcoming and to reawaken society to the nature and severity of the Jewish Question.

You May Also Like

Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation

Best Tales of Texas Ghosts

Islam: A Short History (Modern Library Chronicles #2)

Texas Haunted Forts

Imminent: Inside the Pentagon's Hunt for UFOs

Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation

A Ukrainian Christmas

God: A Human History

The Newish Jewish Encyclopedia: From Abraham to Zabar’s and Everything in Between

The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy: and the Path to a Shared American Future

The Koran in English: A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books #27)

A Story Waiting to Pierce You: Mongolia, Tibet and the Destiny of the Western World

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine

The House Divided: Sunni, Shia and the Making of the Middle East

Life: My Story Through History

A Little History of Religion (Little Histories)

Celtic Women's Spirituality: Accessing the Cauldron of Life

Man's Search for Meaning

Calloused Heart: Navigating the Balance between Faith and Violence

American Zion: A New History of Mormonism

Unexpected: The Backstory of Finding Elizabeth Smart and Growing Up in the Culture of an American Religion

Brujería: A Little Introduction (RP Minis)

Spooky Texas: Tales of Hauntings, Strange Happenings, and Other Local Lore

Meditation for Beginners: Techniques for Awareness, Mindfulness & Relaxation (Llewellyn's for Beginners)

The Shortest History of Europe: How Conquest, Culture, and Religion Forged a Continent - A Retelling for Our Times (The Shortest History Series)

Exploring how religious and secular forces interact in the modern world.

Theorizing Modernities article

Why is the jewish question different from all similar questions.

This essay is based on a talk given during the “Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Critique of Israel: Towards a Constructive Debate” conference held at University of Zurich from June 29–30, 2022.

To confront the relationship between antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and the critique of Israel is a daunting challenge. In light of this monumental task, a remark from the Talmud comes to mind. Rabbi Tarfon said, “The day is short, the task is great. You are not obliged to complete the task, but neither are you free to give it up” (Bab. Tal., Ninth Tractate Avot , 2:20–21). This sums up my situation perfectly. My space is limited and the task is great. I could not possibly complete it, but neither am I capable of giving it up. Far from giving it up, the question of the Jewish Question is now at the center of my work on antisemitism, anti-Zionism, and the critique of Israel.

This post is divided into two parts. In part I, “Asking the Jewish Question,” I argue for one reading of the Question. I call it, for a reason that I hope becomes clear, “the antithesis reading.” In Part II, “Questioning the Zionist Answer,” I concentrate on an alternative reading, “the national reading,” which I see as underlying political Zionism in all its different forms. (In this essay, whenever I refer to Zionism I mean political Zionism and not the cultural Zionism associated, in the first place, with Ahad Ha’am.) There are many angles of approach to questioning Zionism. In Part II, I refer only to “the postcolonial critique” advanced by the Left —but I barely scratch the surface. (Barely scratching the surface is a good way to describe my essay as a whole.) I argue that, on the one hand, Jews who react against anti-Zionism (or come to the defense of Israel) tend to slip unawares between one reading of the Jewish Question and the other. On the other hand, the Left (including a section of the Jewish Left) tends to be too quick to dismiss their reaction when giving a postcolonial critique of Zionism and Israel. The combination of these two tendencies generates impassioned confusion—confusion that is not merely intellectual—on both sides. The analysis points to self-critique—on both sides—as a condition for the possibility of constructive debate.

I. Asking the Jewish Question

The so-called “Jewish Question” is a question in the sense of being a problem that needs to be solved. But who set the problem? For whom—in whose eyes—is there a problem about the Jews, the Jews as Jews? I suppose the first person who saw the Jews as a problem was Moses, who, time and again, complained to God about them; or maybe it was God who first saw the Jews as problematic. I don’t know. In any case, the problem they saw is not exactly the problem to which the so-called “Jewish Question” refers. The “Jewish Problem” is set by Europe: it is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews.

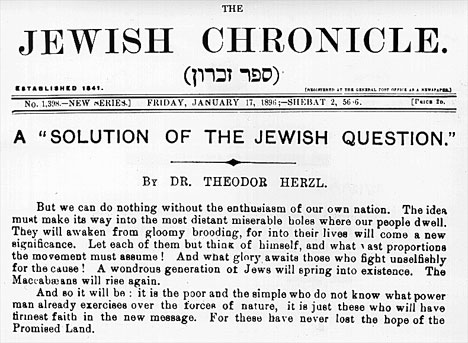

The term “the Jewish Question” became current in the 19 th century. This was, says Holly Case in her book of the same name, “ the age of questions ,” by which she means questions with the form “the X question.” The X questions were a motley lot, but, by and large, they could be grouped under three headings: “social,” “religious,” or “national.” The Jewish Question, rather like the Jews themselves, had no fixed abode: it could be housed under any one of these headings. I shall focus on the view that, au fond , it was a national question, keeping company with such questions as the Armenian, Macedonian, Irish, Belgian, Kurdish, and so on. I do so because the national take on the Jewish Question is the one that is especially relevant to our conference, “Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Critique of Israel: Towards a Constructive Debate .” From Herzl to the present day, the Jewish Question has been construed in political Zionism as a national question; and Zionism lies at the heart of the current debate about Israel and antisemitism.

The “Jewish Problem” is set by Europe: it is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews.

The national take, however, is a mis -take. The Jews were not another case of a European nation whose future on the political map was the subject of debate. Rather, whether the Jews collectively are a nation in the modern (European) sense was up for debate: it was an integral part of the Jewish Question. Nor was there anything novel about querying their collective status: the status of the Jews was seen as problematic for a thousand years or more before the political formations that were the subject of the National Question in the 19th century came into being. And, while there were other groups in this period whose status as nations was up for debate, the case of the Jews was radically different. How so? The answer to this question gets to the core of the Jewish question.

I noted earlier that the Jewish Question is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews. But, although ostensibly about the Jews, ultimately it is about Europe: it is about Europe via the question of the Jews. It always has been, ever since antiquity and the days of the original European Union (as it were), the one whose capital city was Rome. Anti-Jewish animus is older than the Roman Empire, of course. But the story I have in mind begins with the conversion to Christianity of Flavius Valerius Constantinus, otherwise known as Constantine the Great, Emperor of Rome. Constantine’s conversion on his deathbed gave birth, in a way, to the question that came to be called “Jewish.” From this point on, Europe has used the Jews to define itself. The question, which we might rename “the European Question,” was this: What is Europe? Answer: not Jewish. Down the centuries, as Europe’s idea of itself changed, this “not” persisted, though it took different forms.

Granted, in the “New Europe” that emerged after the shock and tumult of the Shoah and the Second World War, the role of Jews collectively has, to some extent, been inverted. We are now liable to function for Europe (as I have discussed elsewhere ) more as an admired model than as a despised foil , with consequences for Western European policies towards the State of Israel. Furthermore, a thread of philosemitism runs through Europe’s history . Neither of these points, however, contradicts the account I am giving here of the negative role played by Jews down the centuries in Europe’s self-definition.

Thus, the Jewish Question existed as an issue for Europe avant la lettre . Seen as being in Europe but not of Europe, the Jews were the original “internal Other,” the inner alien to the European self, the Them inside the Us. First, in antiquity, Judaism was the foil against which Europe defined itself as Christian. Then, in the eighteenth century, the Jews were, as Adam Sutcliffe puts it in his book Judaism and the Enlightenment , “the Enlightenment’s primary unassimilable Other,” but no longer as the immovable object to Christianity ‘s irresistible force (254). Esther Romeyn explains: “For the Enlightenment, with its investment in universalism and civilization, the Jew was a symbol of particularism, a backward-looking, pre-modern tribal culture of outmoded customs and religious tutelage” (92). In the following century, the symbol flipped. Romeyn again (partly quoting Sarah Hammerschlag ): “For a nationalism based on roots, the distinctiveness of cultures, and allegiance to a shared past, the Jew was an uprooted nomad or a suspect ‘cosmopolitan’ aligned with ‘abstract reason rather than roots and tradition’” (92; Hammerschlag, 7, 20). Europe now saw itself as a patchwork quilt of ethnic nationalities and the question arose: “How do the Jews fit in? Do they fit in? If they do not, what is to be done with them or with their Jewishness?” This was the Jewish Question in the 19 th century, a new variation on a very old European theme: the theme of the anomalous Jew; or, more precisely, the antithetical Jew.

In short, the National Question was about ethnic difference and how Europe should deal with it. The Jewish Question was about the alien within—so deep within as to be internal to Europe’s idea of itself. Other groups and peoples, such as Arabs and Africans, have played the part of Europe’s external Others; this is written into the script of European imperialism and colonialism. They too have provided a reference point for Europe to define itself by way of what it is not. But Jews as Jews are not part of the colonial script. As Jews, we have been, ab initio , “insider outsiders,” a people who, in any given era, are the negative—the internal negative—to Europe’s positive: belonging in Europe by not belonging. Certainly, the Jewish Question, as it has been asked in different European places at different times, has features in common with other “X questions.” Moreover, the Jewish Question is not unique in being unique! Each “X question” is unique or singular in its own distinctive way. But the singularity of the Jewish case is such that it escapes the boxes in which other “X questions” are placed. Being seen as antithetical to Europe, like the alien race in the 1960 horror film Village of the Damned : this is what underlies the questionableness of “the Jews.” It is why (to allude to the title of my paper) the Jewish Question is different from all similar questions. I call this reading of the Jewish Question “the antithesis reading.” Whether it adequately describes the Jewish space in the European imagination, the salient point is this: this is how the Question sits in Jewish collective memory, continually working in the background of the Zionist answer to the Question.

II. Questioning the Zionist Answer

The mass of Jews, if only subliminally, bring collective memory to their embrace of Zionism and the State of Israel. They keep slipping, in the process, between two different readings of the Jewish Question, eliding the one with the other: the one I have just given and the one that Theodor Herzl gives in Der Judenstaat . Herzl’s (mis)reading has become a staple of the State of Israel as it defines itself (and, simultaneously, defines the Jewish people). In Der Judenstaat , he fastens onto the category of “nation.” He writes: “I think the Jewish question is no more a social than a religious one, notwithstanding that it sometimes takes these and other forms. It is a national question …” (15). The subtitle of Der Judenstaat calls his political proposal, a state of the Jews, “An Attempt at a Modern Solution of the Jewish Question”; he means the national question. The indefinite article (“ a Modern Solution”) is misleading. Herzl wrote to Bismarck : “I believe I have found the solution to the Jewish Question. Not a solution, but the solution, the only one” (245). Several times (four to be precise) the text refers to “the National Idea,” which, as Herzl envisages it, would be the ruling principle in the Jewish state and, as I read him, in the rest of the Jewish world too (see Der Judenstaat, 49, 50, 54 and 70). The latter idea, if not explicit, is coiled up inside Herzl’s text. I call his reading of the Jewish Question “the national reading.”

Zionism, both as a movement and as an ideology, has changed a lot since Herzl wrote his foundational pamphlet. It has developed two political wings (left and right); it has both secular and religious varieties; and it has produced a state: the State of Israel. But, fundamentally, Herzl’s take on the Jewish Question—figuring it as a national question, putting “the National Idea” at the heart of Jewish identity—has persisted to the present day. This is reflected in the Nation-State Bill (or Nationality Bill), which, upon being passed in the Knesset in 2018, became a Basic Law: Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish People. The law is “basic,” not only for the constitution of the Jewish state but also for the Zionist goal of re constituting the Jewish people as “a nation, like all other nations” with a state of its own, as Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence puts it . This means reconstituting Judaism itself. [1]

Why do so many rank and file Jews across the globe appear to accept this reconstitution of their identity? Why did Britain’s current Chief Rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis , call Zionism “one of the axioms of Jewish belief”? How could he write: “Open a Jewish daily prayer book [ siddur ] used in any part of the world and Zionism will leap out at you.” Zionism, noch , not Zion. When exactly did Judaism convert to the creed of “the National idea”? in January 2009, when Operation Cast Lead was in full swing in Gaza, why was London’s Trafalgar Square awash with Israeli flags held aloft by British Jews? I witnessed this for myself. I was part of a small Jewish counter-demonstration that was spat at and jeered by some of the people—fellow Jews—in the official rally. How did people who are otherwise decent, people who uphold human rights, suddenly become ardent fans of forced evictions, house demolitions, and military violence against unarmed civilians? No doubt, there are zealots who would tick this box in the name of “the Jewish nation-state.” But zealotry is not what moves the mass of Jews to flock to the flag. If they identify with Israel (or defend it at all costs), it is not because they are persuaded intellectually by the “National Idea” (which is what underlies Herzl’s “national reading” of the Jewish Question), but because they feel viscerally the unbearable burden of the Question (which underlies the “antithesis reading”). When they wave the Israeli flag, it is certainly a gesture of defiance, and possibly hostility, aimed at Palestinians; but, at bottom, it is aimed at Europe—not just at the centuries of exclusion and oppression, but at the sheer chutzpah of Europe’s asking “the Jewish Question”—a question to which there is no right answer, because there is no right answer to the wrong question. [2]

But we Jews, understandably, are hungry for an answer that will put an end to the price we have paid for the nature of our difference. Political Zionism might appear to provide the answer. Paradoxically, the Zionist answer consists in taking Jews out of Europe to the Middle East in order to be included in the European dispensation. (Or you could say: normalizing by conforming to the European norm; it’s as if, by leaving, we’ve arrived.) Leading Zionist figures, from Herzl to Nordau to Ben-Gurion to Barak to Netanyahu, have placed “the Jewish state” in Europe, or see it as an extension of Europe. As Herzl wrote , “We should there form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia” (30). More recently Benjamin Netanyahu was quoted saying, “We are a part of the European culture. Europe ends in Israel. East of Israel, there is no more Europe.” So, the concept of the Jewish people becomes ethno-national—just like the real European thing; newcomers, who are largely from Europe, create a home for themselves by dispossessing the people who previously inhabited the land—just like a European colony; they turn their home into a state, just like certain former European colonies (such as the “White” dominions of Canada and Australia). Then there is the way their state—Israel—conducts itself in what is generally regarded as part of the Global South. It subjugates, à la Europe, the previous inhabitants of the land; it systematically discriminates against them; it expands its territory via settlers—a classic European practice; and it enters the Eurovision song contest. In all these respects (except perhaps the song contest), Israel courts a postcolonial critique. The Left are happy to oblige. In a way, the postcolonial critique is the ultimate compliment, the capstone on Zionism’s European solution of Europe’s Jewish Problem.

This prompts a surprising question, one that might seem ludicrous or at least redundant, but follows logically from the argument so far. It is this: Since political Zionism locates the state of Israel in Europe, and since Israel conducts itself in the manner of a European colonizing power, what is so objectionable to the generality of Jews—those who close ranks around Zionism and the state of Israel—about a critique that precisely treats Israel as a European state? The answer is that there is a piece missing from the stock postcolonial discourse, a discourse that folds Zionism completely, without remainder, into the history of European hegemony over the Global South, as if this were the whole story . But it is not; and the piece that is missing is, for most Jews, including quite a few of us who are not part of the Jewish mainstream regarding Zionism and Israel, the centerpiece. Put it this way: For Jews in the shtetls of Eastern Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s (like my grandparents), the burning question was not “How can we extend the reach of Europe?” but “How can we escape it?” That was the Jewish Jewish Question. Like Europe’s Jewish Question, it too was not new; and it was renewed with a vengeance after the walls of Europe closed in during the first half of the last century, culminating in the ultimate crushing experience: genocide . Among the Jewish answers to the Jewish Jewish Question was migration to Palestine. But, by and large, the Jews who moved to Palestine after the Shoah were not so much emigrants as (literally or in effect) refugees. This does not, for a moment, justify the dispossession of the Palestinians, let alone the grievous injustices inflicted upon them by the State of Israel from its creation in 1948 to the present day. But it does put a massive dent into the story told in the postcolonial critique. We need another, more nuanced and inclusive, story.

For Jews in the shtetls of Eastern Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s (like my grandparents), the burning question was not ‘How can we extend the reach of Europe?’ but ‘How can we escape it?’

In a sense, both the “national reading” of the Jewish Question, which Zionism assumes and Israel embodies, and the postcolonial critique of Israel and Zionism, are culpable in the same way: both take an existing European paradigm and apply it to the Jewish case, without so much as a mutatis mutandis . Neither passes muster. Moreover, the omission of what is, for most Jews, the centerpiece of the story behind Zionism and the creation of Israel erases a crucial feature of Jewish historical experience and collective memory. Not only does this erasure vitiate the postcolonial critique, it also feeds the suspicion that many Jews harbor that the critique is malign. It has a familiar ring. They feel, in their guts, that it is another slander against the Jews, a new expression of an old animus—antisemitism by any other name. To put it mildly, this is an exaggeration. The Left, in turn, are skeptical about this reaction. It has a familiar ring. They feel, in their guts, that it is disingenuous, a cynical ploy to suppress criticism of Israel. This too, to put it mildly, is an exaggeration. The more one side reacts to the other side, the more the other side reacts to them. This is not a debate. It is a bout, a wrestling bout, where the two antagonists are locked in a clinch, as inseparable as lovers.

The analysis in this essay suggests that each of the adversaries is in the grip of certain states of mind, connected to particular blind spots. In one case, it is confusion about the meaning of the Question that Europe has persisted in asking about the Jews, plus obliviousness to the injustices done to Palestinians by the Jewish “nation-state.” In the other case, it is confusion over the limits of a postcolonial critique, plus obliviousness to what it is that leads so many Jews to react understandably and, to an extent, legitimately, against that critique. The upshot, on the one side, is demonization of the Left; on the other side, demonization of Zionism. Accordingly, the question each side needs to ask is not “How can I break the hold of the other?,” but “How can I break my hold on the other?” “How,” that is to say, “can I loosen the grip that certain confused ideas and powerful passions have over me?” In short, if a futile bout is to turn into a constructive debate, what is needed is self-critique. This is not asking too much of ourselves. But the task is great, and life is short.

[1] The best treatment that I have seen of a cluster of questions surrounding Jewish identity, Zionism, and the state of Israel is in the work of Yaacov Yadgar, Professor of Israel Studies, University of Oxford. See especially his two books: Sovereign Jews: Israel, Zionism, and Judaism and Israel’s Jewish Identity Crisis: State and Politics in the Middle East .

[2] My current work in this area is focused on developing the idea of unasking the Jewish Question .

Share this article:

One thought on “ Why is the Jewish Question Different from All Similar Questions? ”

A very interesting and thought provoking read. As an Irish leftist I found it illuminating. We too are one of C19TH Europe’s questions. We understand the urge to escape oppression and to have a safe place (our own state). We have supplied a president of Israel, a fact of which many of us are proud. We admire Jewish discourse and intelligence. We are horrified to see Jews become genocidal butchers, as bad as the Europeansthey fled, with just the clothes on their backs. We admire and envy the restoration of Hebrew. So we are conflicted. We admire Jews, we are impressed by the success of Israel but we are ashamed of its crimes. Unlike other Europeans we feel guilt-free in relation to the murder of Jews and we feel morally obliged to call on Israel to behave in line with international law and its own, Jewish morality. Are we holding Israel to higher standards than Syria or Saudi Arabia? Yes. Is it because they should behave as Jews, or as Europeans? Probably.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Fully aware of the ways in which personhood has been denied based on the hierarchies of modernity/coloniality, we do not publish comments that include dehumanizing language and ad hominem attacks. We welcome debate and disagreement that educate and illuminate. Comments are not representative of CM perspectives.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945

9781737446187.

Description:

Best prices to buy, sell, or rent ISBN 9781737446187

Frequently asked questions about classic essays on the jewish question: 1850 to 1945, how much does classic essays on the jewish question: 1850 to 1945 cost.

At BookScouter, the prices for the book start at $ 30.30 . Feel free to explore the offers for the book in used or new condition from various booksellers, aggregated on our website.

Current Buyback Prices for ISBN-13 9781737446187 ?

If you’re interested in selling back the Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 book, you can always look up BookScouter for the best deal. BookScouter checks 30+ buyback vendors with a single search and gives you actual information on buyback pricing instantly.

As for the Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 book, the best buyback offer comes from and is $ for the book in good condition.

Is Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 in high demand?

Not enough insights yet.

When is the right time to sell back 9781737446187 Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 ?

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- < Back to search results

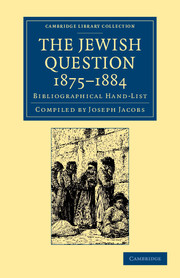

- The Jewish Question, 1875–1884

The Jewish Question, 1875–1884

Bibliographical hand-list.

- Get access Buy a print copy Check if you have access via personal or institutional login Log in Register

- Compiled by Joseph Jacobs

- Export citation

- Buy a print copy

Book description

Although born in Australia, the historian and folklorist Joseph Jacobs (1854–1916) spent his adult years in England and America. Educated at Cambridge and Berlin, he came to public attention in 1882 following the publication in The Times of a series of articles on the persecution of Jews in Russia that had followed the assassination of Alexander II. The Mansion House Committee to aid the Jews of Russia was established as a result of these articles. In 1885 he published this book, listing all the printed works on the 'Jewish Question' that had appeared in the previous decade. It is notable that those items originating in Germany form the bulk of the bibliography, providing as much material as all other countries combined. Revealing in its scope, this has been described as the most important contemporary bibliography on the subject.

- Aa Reduce text

- Aa Enlarge text

Refine List

Actions for selected content:.

- View selected items

- Save to my bookmarks

- Export citations

- Download PDF (zip)

- Save to Kindle

- Save to Dropbox

- Save to Google Drive

Save content to

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to .

To save content items to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

Save Search

You can save your searches here and later view and run them again in "My saved searches".

Frontmatter pp i-iii

- Get access Check if you have access via personal or institutional login Log in Register

Introduction pp iv-iv

Preface pp v-xii, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 1 to 12 pp 1-12, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 12 to 19 pp 12-19, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 20 to 23 pp 20-23, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 23 to 25 pp 23-25, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 26 to 27 pp 26-27, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 28 to 29 pp 28-29, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 29 to 32 pp 29-32, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 32 to 35 pp 32-35, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 35 to 36 pp 35-36, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 36 to 37 pp 36-37, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 38 to 40 pp 38-40, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 40 to 44 pp 40-44, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 44 to 49 pp 44-49, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 49 to 59 pp 49-59, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 60 to 61 pp 60-61, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 62 to 71 pp 62-71, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 71 to 79 pp 71-79, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 79 to 87 pp 79-87, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 87 to 88 pp 87-88, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 88 to 88 pp 88-88, the jewish question, 1875–1883 pages 89 to 91 pp 89-91, appendix pp 91-96, full text views.

Full text views reflects the number of PDF downloads, PDFs sent to Google Drive, Dropbox and Kindle and HTML full text views for chapters in this book.

Book summary page views

Book summary views reflect the number of visits to the book and chapter landing pages.

* Views captured on Cambridge Core between #date#. This data will be updated every 24 hours.

Usage data cannot currently be displayed.

Religious Studies

You are here, classic essays in early rabbinic culture and history.

This volume brings together a set of classic essays on early rabbinic history and culture, seven of which have been translated into English especially for this publication. The studies are presented in three sections according to theme: (1) sources, methods and meaning; (2) tradition and self-invention; and (3) rabbinic contexts. The first section contains essays that made a pioneering contribution to the identification of sources for the historical and cultural study of the rabbinic period, articulated methodologies for the study of rabbinic history and culture, or addressed historical topics that continue to engage scholars to the present day. The second section contains pioneering contributions to our understanding of the culture of the sages whose sources we deploy for the purposes of historical reconstruction, contributions which grappled with the riddle and rhythm of the rabbis’ emergence to authority, or pierced the veil of their self-presentation. The essays in the third section made contributions of fundamental importance to our understanding of the broader cultural contexts of rabbinic sources, identified patterns of rabbinic participation in prevailing cultural systems, or sought to define with greater precision the social location of the rabbinic class within Jewish society of late antiquity. The volume is introduced by a new essay from the editor, summarizing the field and contextualizing the reprinted papers.

About the series

Classic Essays in Jewish History

(Series Editor: Kenneth Stow)

The 6000 year history of the Jewish peoples, their faith and their culture is a subject of enormous importance, not only to the rapidly growing body of students of Jewish studies itself, but also to those working in the fields of Byzantine, eastern Christian, Islamic, Mediterranean and European history. Classic Essays in Jewish History is a library reference collection that makes available the most important articles and research papers on the development of Jewish communities across Europe and the Middle East. By reprinting together in chronologically-themed volumes material from a widespread range of sources, many difficult to access, especially those drawn from sources that may never be digitized, this series constitutes a major new resource for libraries and scholars. The articles are selected not only for their current role in breaking new ground, but also for their place as seminal contributions to the formation of the field, and their utility in providing access to the subject for students and specialists in other fields. A number of articles not previously published in English will be specially translated for this series. Classic Essays in Jewish History provides comprehensive coverage of its subject. Each volume in the series focuses on a particular time-period and is edited by an authority on that field. The collection is planned to consist of 10 thematically ordered volumes, each containing a specially-written introduction to the subject, a bibliographical guide, and an index. All volumes are hardcover and printed on acid-free paper, to suit library needs. Subjects covered include:

The Biblical Period The Second Temple Period

The Development of Jewish Culture in Spain

Jewish Communities in Medieval Central Europe

Jews in Medieval England and France

Jews in Renaissance Europe

Jews in Early Modern Europe

Jews under Medieval Islam

Jews in the Ottoman Empire and North Africa

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Collection. opensource. Language. English. Item Size. 30.7M. This is an excerpt written by Dostoevsky on the Jews in Russia from his thousand-plus page "A Writer's Diary." Addeddate. 2021-01-06 09:11:11.

The Jewish question presents itself differently according to the state in which the Jew resides. In Germany, where there is no political state, no state as such, the Jewish question is purely theological. The Jew finds himself in religious opposition to the state, which proclaims Christianity as its foundation. This state is a theologian ex ...

Into the National Socialist era, a number of Germans, including Theodor Fritsch, Adolf Hitler, and Heinrich Himmler, took a very hard line against the Jewish intruders. Their words are potent and compelling. Now, for the first time, 16 classic essays are compiled into a single volume. These essays are difficult to find, even in the Internet age.

ISBN-13: 9781737446187. See Item Details . Alibris. BEST. NV, USA. $30.60 $38.00. Add to Cart. Add this copy of Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 to cart. $30.60, new condition, Sold by Ingram Customer Returns Center rated 5.0 out of 5 stars, ships from NV, USA, published 2022 by Clemens & Blair, LLC.

The original near-century timespan divides Karl Marx's essay "On the Jewish Question", written in 1843, from Abram Leon's book The Jewish Question, completed in 1942. And the specific area is chosen for the reason that it was essentially only in Central and Eastern Europe that an internal Marxist debate developed around "the Jewish ...

"On the Jewish Question" is a response by Karl Marx to then-current debates over the Jewish question.Marx wrote the piece in 1843, and it was first published in Paris in 1844 under the German title "Zur Judenfrage" in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher.The essay criticizes two studies [1] [2] by Marx's fellow Young Hegelian, Bruno Bauer, on the attempt by Jews to achieve political ...

The Jewish Question goes back centuries, at least to ancient Rome. The Romans were the first Western power to encounter the Judean Hebrews, to defeat them, and to scatter them throughout the world. Unfortunately, Roman victory proved temporary; with the collapse of the Empire in 395 AD, Jews and Judeo-Christianity took hold in Europe.

Publisher: Clemens & Blair, LLC. ISBN: 9781737446170. Number of pages: 370. Weight: 540 g. Dimensions: 229 x 152 x 21 mm. Buy Classic Essays on the Jewish Question by Thomas Dalton from Waterstones today! Click and Collect from your local Waterstones or get FREE UK delivery on orders over £25.

'On the Jewish Question' 'A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: Introduction' From the Paris Notebooks 'Critical Marginal Notes on "The King of Prussia and Social Reform. By a Prussian"' Points on the State and Bourgeois Society 'On Feuerbach' From 'The German Ideology': Chapter One, 'Feuerbach'.

Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1970. Google Scholar. Davis, Leopold. " The Hegelian Antisemitism of Bruno Bauer.". History of European Ideas 25 (1999): 179 - 206.

Limited Preview for 'Classic Essays on the Jewish Question : 1850 To 1945' provided by Archive.org *This is a limited preview of the contents of this book and does not directly represent the item available for sale.* A preview for 'Classic Essays on the Jewish Question : 1850 To 1945' is unavailable. ...

Karl Marx and the Jewish Question'. William H. Blanchard2. Karl Marx sought virtue through suffering. His need to seek it in some. of social rebellion was a product of his early life experiences. reaction to his Jewish origin determined the direction of that rebellion: field of economics. His first paper on the Jewish question described the.

In these words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer we glimpse the creative centre of his paradigm for human behaviour within the church and the state. Through essays, letters and books he explored both traditional and experimental patterns of relating the church which he served to the state, especially the German state during the rule of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis (1933-45).

classic essays in relation to the growing perception that the early modern period in Jewish history possesses its own distinctive features and identity. Accompanied by a rich bibliography, the volume highlights the many changes that the academic study of this vital phase of the Jewish past has undergone during the last hundred and twenty years.

The "Jewish Problem" is set by Europe: it is a question Europe asks itself about the Jews. The term "the Jewish Question" became current in the 19 th century. This was, says Holly Case in her book of the same name, " the age of questions," by which she means questions with the form "the X question.".

You can buy the Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850 to 1945 book at one of 20+ online bookstores with BookScouter, the website that helps find the best deal across the web. Currently, the best offer comes from and is $ for the .

text of the larger piece ("The Jewish Question"), of which they constitute the con-clusion. Jewish commentators have largely dismissed the reconciliation that Dos-toevskii envisions at the end of "The Jewish Question" as lacking in conviction and 2See Robert Louis Jackson, "'If I Forget Thee, 0 Jerusalem': An Essay on Chekhov's 'Rothschild's

The formulation of a question is its solution. The critique of the Jewish question is the answer to the Jewish question. The summary, therefore, is as follows: We must emancipate ourselves before we can emancipate others. The most rigid form of the opposition between the Jew and the Christian is the religious opposition.

Select THE JEWISH QUESTION, 1875-1883 pages 88 to 88. THE JEWISH QUESTION, 1875-1883 pages 88 to 88 pp 88-88. Get access. Check if you have access via personal or institutional login. Log in Register. Export citation; Select THE JEWISH QUESTION, 1875-1883 pages 89 to 91.

Classic Essays in Jewish History provides comprehensive coverage of its subject. Each volume in the series focuses on a particular time-period and is edited by an authority on that field. The collection is planned to consist of 10 thematically ordered volumes, each containing a specially-written introduction to the subject, a bibliographical ...