Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI): 16 Personality Types

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is an introspective, self-report evaluation that identifies a person’s personality type and psychological preferences.

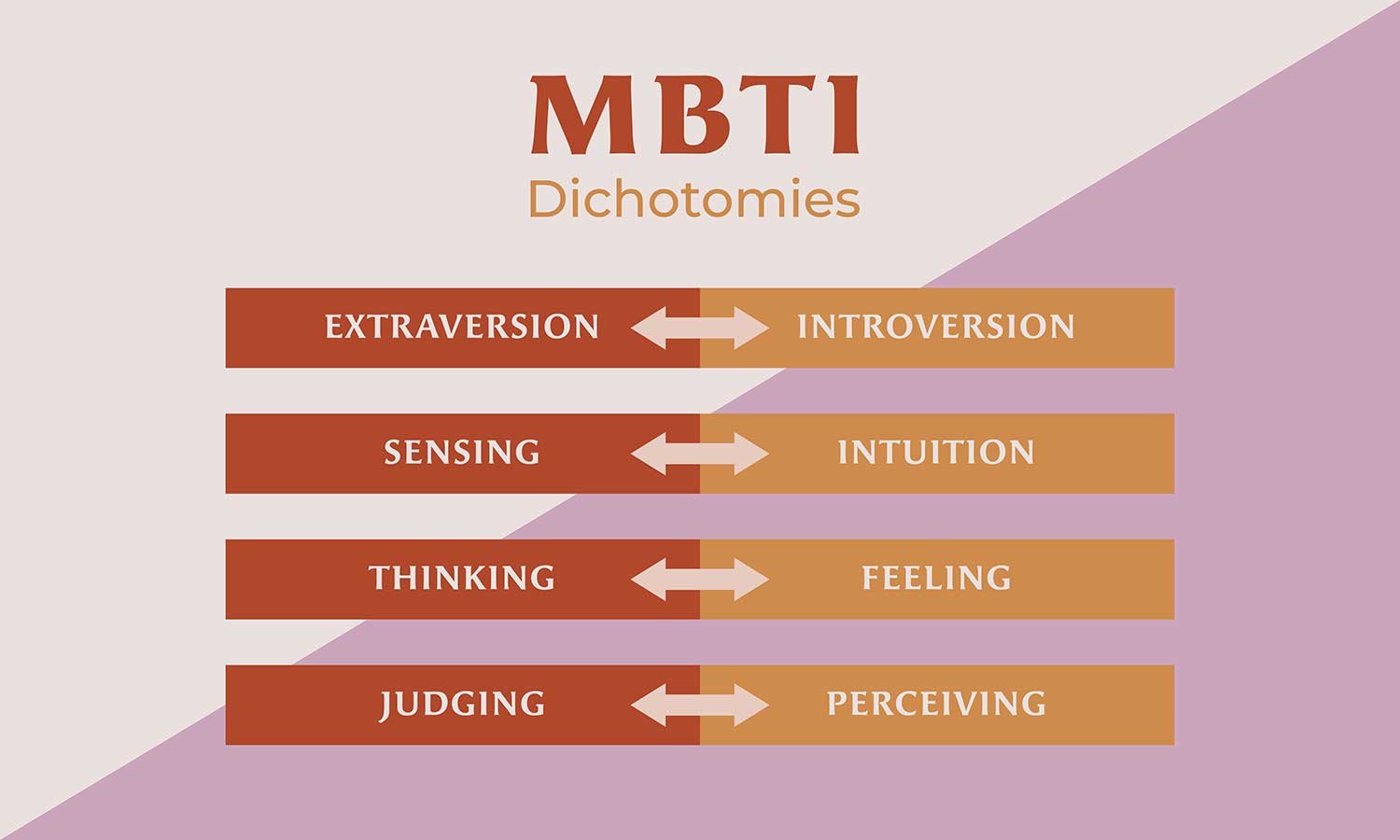

The MBTI propose that four different cognitive functions determine one’s personality: extraversion vs. introversion, sensing vs. intuition, thinking vs. feeling, and judging vs. perceiving.

MBTI Meaning

MBTI, short for Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, is a widely used personality assessment tool based on Carl Jung’s theories.

It categorizes individuals into one of 16 personality types, providing insights into their preferences in four dimensions: extraversion/introversion, sensing/intuition, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving. MBTI is commonly used for personal development, career counseling, and team building.

According to the MBTI theory, you combine your preferences to determine your personality type. The 16 types are referred to by an abbreviation of the initial letters of each of the four type preferences of each cognitive function.

For example, “ISTP” would denote introversion, sensing, thinking, and perceiving. No combination is considered “better” or “worse” than another– all types are considered equal.

The MBTI emphasizes that each individual has specific preferences in the way they view the world, and this assessment provides insight into the differences and similarities in people’s experiences of life.

The Development of the Myers-Briggs Test

The MBTI tool was developed by Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother Katharine Cook Briggs in 1942 and is based on psychological conceptual theories proposed by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung in his work, Psychological Types.

Jung’s theory of psychological types was based on the existence of four essential psychological functions – judging functions (thinking and feeling) and perceiving functions (sensation and intuition ).

He believed that one combination of the functions is dominant for a person most of the time.

Jung’s theory holds that human beings are either introverts or extroverts , so the combinations are expressed in either an introverted or extroverted form (This is why E or I is the first letter of the series). The remaining three functions operate in the opposite orientation.

The Four Dichotomies:

This assessment aims to assign individuals into one of four categories based on how they perceive the world and make decisions, enabling respondents to further explore and understand their own personalities.

The four categories are: introversion or extraversion, sensing or intuition, thinking or feeling, and judging or perceiving. Each person is said to have one preferred quality from each category, producing 16 unique personality types.

Extraversion (E) vs. Introversion (I)

- These are opposite ways to direct and receive energy. Do you prefer to focus on the outer world or your inner world?

- This dichotomy describes how people respond and interact with others and orient themselves within the world around them.

Extraverts tend to be action-oriented – focusing on other people and things, feeling energized by the presence of others, and emitting energy outwards.

Introverts are more thought-oriented. They enjoy deep and meaningful social interactions and feel recharged after spending time alone.

Sensing (S) vs. Intuition (N)

- Do you prefer to focus on the basic information you take in, or do you prefer to interpret and add meaning?

- This dichotomy describes how people gather and perceive information.

- Sensing-dominant people tend to prefer to focus on facts and details and perceive the world around them through their five senses.

- Intuition-dominant types are more abstract in their thinking, focusing on patterns, impressions, and future possibilities.

Thinking (T) vs. Feeling (F)

- When making decisions, do you prefer to first look at logic and consistency or first look at the people and special circumstances?

This dichotomy describes how people make decisions and use judgments.

Thinking types use logic and facts to judge the world, while feeling types tend to consider emotions.

Judging (J) vs. Perceiving (P)

- In dealing with the outside world, do you prefer to get things decided, or do you prefer to stay open to new information and options?

This dichotomy describes how people tend to operate in the outside world and reveals the specific attitudes of the functions.

Those judging dominant tend to be more methodical and results-oriented and prefer structure and decision-making.

Perceiving dominant individuals are more adaptable and flexible and tend to be good at multitasking.

The dominant function is the primary aspect of personality, while the auxiliary and tertiary functions play supportive roles.

The 16 Personality Types

Istj – the logistician.

These individuals tend to be serious, matter-of-fact, and reserved. They appreciate order and organization and pay a great deal of attention to detail.

They like to plan things out in advance and place an emphasis on tradition and law. They are responsible and realistic and can be described as dependable and trustworthy.

ISFJ – The Defender

These individuals are friendly, responsible, and reserved. They are service and work-oriented, committing to meeting their obligations and duties.

They are loyal, considerate, and place a lot of focus on the care of others. They are non-confrontational and value an orderly and harmonious environment.

INFJ – The Advocate

People with this personality type are serious, logical and hardworking. They are also compassionate, conscientious, and reserved.

They value close, deep connections and are sensitive to the needs of others, but also need time and space alone to recharge.

INTJ The Architect

These people are highly independent, self-confident and prefer to work alone. They are analytical, creative, logical, and driven.

They place an emphasis on logic and fact rather than emotion and can be viewed as perfectionist.

They tend to have high expectations of competence and performance for themselves and others.

ISTP – The Crafter

People with this personality type are fearless and independent. They love adventure, new experiences, and risk-taking.

They tend to be quiet observers and are not well attuned to the emotional states of others, sometimes coming across as insensitive or stoic.

They are results- oriented, acting quickly to find workable solutions and understand the underlying cause of practical problems.

ISFP – The Artist

These individuals are quiet, friendly, easy going, and sensitive. They have a strong need for personal space and time alone to recharge.

They value deep connection and prefer to spend time with smaller groups of close friends and family.

They are highly considerate and accepting, avoiding confrontation and committed to their values and to people who are important to them.

INFP – The Mediator

These people are creative, idealistic, caring, and loyal. They have high values and morals, and are constantly seeking out ways to understand people and to best serve humanity.

They are family and home-oriented and prefer to interact with a select group of close friends.

INTP – The Thinker

People with this personality type are described as quiet, contained, and analytical. They are highly focused on how things work and on solving problems, and tend to be good at logic and math.

They are more interested in ideas and theoretical concepts than in social interaction. They are loyal and affectionate to their closest friends and family, but tend to be difficult to get to know.

ESTP – The Entrepreneur

These individuals are action-oriented, taking pragmatic approaches to obtain results and solve problems quickly. They are often sophisticated, charming, and spontaneous.

They are outgoing and energetic, and enjoy spending time with a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. They focus on the here and now and prefer the practical over the abstract.

ESFP – The Entertainer

These people tend to be outgoing, friendly, and impulsive, seizing energy from other people. They love to be the center of attention and enjoy working with others in new environments.

They can be described as easy going, fun, and optimistic. They are spontaneous and focused on the present moment, and enjoy learning through hands-on experiences with other people.

ENFP – The Champion

These individuals are enthusiastic, creative, energetic, and highly imaginative. They have excellent people and communication skills and are good at giving others appreciation and support.

They do, however, seek approval from others. They value emotions and expression. They dislike routine and might struggle with disorganization and procrastination.

ENTP – The Debater

People with this personality type can be described as innovative, outspoken, and lively. They are idea-oriented and are more focused on the future rather than on the present moment.

They enjoy interacting with a wide variety of people and love to engage with others in debates. They tend to be easy to get along with, but also can be argumentative at times. They are great conversationalists and make good entrepreneurs.

ESTJ – The Director

These people are responsible, practical, and organized. They are assertive and like to take charge, focused on getting results in the most efficient way possible. They have clear standards and place a high value on tradition and rules.

They can be seen as rigid, stubborn, or bossy as they are forceful in implementing their plans. However, they tend to excel at putting plans into action because they are hardworking, self-confident, and dependable.

ESFJ – The Caregiver

These individuals are warmhearted, conscientious, and harmonious. They wear their hearts on their sleeves and tend to see the best in others.

They enjoy helping others and providing the care that people need, but want to be appreciated and noticed for their contributions. They are careful observers of others and excel in situations involving personal contact and community.

ENFJ – Protagonist

These people are responsible, warm, and loyal. They are highly attuned to the emotions of others and capable of forging friendships with essentially anybody.

They have a desire to help others fulfill their potential, and they derive personal satisfaction from helping others. They tend to make good leaders as they are highly capable of facilitating agreement among diverse groups of people.

ENTJ – The Commander

These individuals like to take charge. They value organization and structure and appreciate long-term planning and goal setting.

They have strong people skills and enjoy interacting with others, but they are not necessarily attuned to their own emotions or the emotions of others.

They have strong leadership skills and tend to make good executives, captains, and administrators.

Benefits of MBTI

- Companies can learn how to support employees better, assess management skills, and facilitate teamwork

- Coaches can utilize the information to help understand their preferred coaching approach

- Teachers can assess student learning style

- Teens and young adults can better understand their learning, communication, and social interaction styles

- Teens can determine what occupational field they might be best suited for

- Individuals can gain insight into their behavior

- Partners can better understand themselves and their spouses, allowing for more cohesive teamwork and greater productivity

Criticisms of MBTI

The MBTI has been criticized as a pseudoscience and does not tend to be widely endorsed by psychologists or other researchers in the field. Some of these critiques include:

- There is little scientific evidence for the dichotomies as psychometric assessment research fails to support the concept of a type, but rather shows that most people lie near the middle of a continuous curve.

- The scales show relatively weak validity as the psychological types created by Carl Jung were not based on any controlled studies and many of the studies that endorse MBTI are methodologically weak or unscientific.

- There is a high likelihood of bias as individuals might be motivated to fake their responses to attain a socially desirable personality type.

- Test-retest reliability is low (ie: test takers who retake the test often test as a different type)

- The terminology of the MBTI is incomprehensive and vague, allowing any kind of behavior to fit any personality type.

Take the MBTI (Paper Version)

Myers, I. B. (1962). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator: Manual (1962).

Myers, Isabel B.; Myers, Peter B. (1995) [1980]. Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89106-074-1.

Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary Comments Regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator . Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

The purpose of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®. The Myers & Briggs Foundation: MBTI Basics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 17 September 2018

A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets

- Martin Gerlach 1 ,

- Beatrice Farb 1 ,

- William Revelle 2 &

- Luís A. Nunes Amaral ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3762-789X 1 , 3 , 4 , 5

Nature Human Behaviour volume 2 , pages 735–742 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

94 Citations

983 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Computational science

- Human behaviour

Matters Arising to this article was published on 16 September 2019

Understanding human personality has been a focus for philosophers and scientists for millennia 1 . It is now widely accepted that there are about five major personality domains that describe the personality profile of an individual 2 , 3 . In contrast to personality traits, the existence of personality types remains extremely controversial 4 . Despite the various purported personality types described in the literature, small sample sizes and the lack of reproducibility across data sets and methods have led to inconclusive results about personality types 5 , 6 . Here we develop an alternative approach to the identification of personality types, which we apply to four large data sets comprising more than 1.5 million participants. We find robust evidence for at least four distinct personality types, extending and refining previously suggested typologies. We show that these types appear as a small subset of a much more numerous set of spurious solutions in typical clustering approaches, highlighting principal limitations in the blind application of unsupervised machine learning methods to the analysis of big data.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

A prediction-focused approach to personality modeling

Personality beyond taxonomy

Identity domains capture individual differences from across the behavioral repertoire

Data availability.

Data are available from https://osf.io/tbmh5/ (Johnson-300 and Johnson-120), http://mypersonality.org (myPersonality-100) and https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7656-1 (BBC-44).

Revelle, W., Wilt, J. & Condon, D. M. in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences (eds Chamorro-Premuzic, T. et al.) 1–38 (Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 2013).

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. in The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Volume 1 Personality Theories and Models (eds Boyle, G. J. et al.) 273–294 (SAGE, London, 2008).

Widiger, T. A. The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model of Personality (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2015).

Book Google Scholar

McCrae, R. R., Terracciano, A., Costa, P. T. & Ozer, D. J. Person-factors in the California adult Q-set: closing the door on personality trait types? Eur. J. Pers. 20 , 29–44 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

Donnellan, M. B. & Robins, R. W. Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality types: issues and controversies. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 11 , 1070–1083 (2010).

Specht, J., Luhmann, M. & Geiser, C. On the consistency of personality types across adulthood: latent profile analyses in two large-scale panel studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107 , 540–556 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Goldberg, L. R. An alternative “description of personality”: the Big-Five factor structure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59 , 1216–1229 (1990).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. NEO PI-R Professional Manual (Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL, 1992).

Google Scholar

Ozer, D. J. & Benet-Martı́nez, V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57 , 401–421 (2006).

Widiger, T. A. & Costa, P. T. Jr. Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality 3rd edn (American Psychological Association, Washington DC, 2013).

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F. & Van Aken, M. A. G. Carving personality description at its joints: confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. Eur. J. Pers. 15 , 169–198 (2001).

Robins, R. W., John, O. P., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E. & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled boys: three replicable personality types. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70 , 157–171 (1996).

Caspi, A. & Silva, P. A. Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Dev. 66 , 486–498 (1995).

Block, J. Lives Through Time (Bancroft Press, Berkeley, CA, 1971).

Costa, P. T., Herbst, J. H., McCrae, R. R., Samuels, J. & Ozer, D. J. The replicability and utility of three personality types. Eur. J. Pers. 16 , S73–S87 (2002).

Herzberg, P. Y. & Roth, M. Beyond resilients, undercontrollers, and overcontrollers? An extension of personality prototype research. Eur. J. Pers. 20 , 5–28 (2006).

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. Points of significance: clustering. Nat. Methods 14 , 545–546 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ashton, M. C. & Lee, K. An investigation of personality types within the HEXACO personality framework. J. Individ. Differ. 30 , 181–187 (2009).

Isler, L., Fletcher, G. J. O., Liu, J. H. & Sibley, C. G. Validation of the four-profile configuration of personality types within the Five-Factor model. Pers. Individ. Dif. 106 , 257–262 (2017).

Rentfrow, P. J. et al. Divided we stand: three psychological regions of the United States and their political, economic, social, and health correlates. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 105 , 996–1012 (2013).

Rentfrow, P. J., Jokela, M. & Lamb, M. E. Regional personality differences in Great Britain. PLoS ONE 10 , e0122245 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Revelle, W. et al. in SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods (eds Fielding, N. G. et al.) 578–595 (SAGE, London, 2016).

Jain, A. K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond k-means. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 31 , 651–666 (2010).

Goldberg, L. R. in Personality Psychology in Europe Vol. 7 (eds Mervielde, I., Deary, I., De Fruyt, F. & Ostendorf, F.) 7–28 (Tilburg Univ. Press, Tilburg, 1999).

Revelle, W. An Introduction to Psychometric Theory with Applications in R (Personality Project, 2017); http://www.personality-project.org/r/book/

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. in The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model (ed. Widiger, T. A.) 1–52 (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2015).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference 2nd edn (Springer, New York, NY, 2002).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6 , 461–464 (1978).

Fortunato, S. & Barthelemy, M. Resolution limit in community detection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 36–41 (2007).

Lancichinetti, A. et al. A high-reproducibility and high-accuracy method for automated topic classification. Phys. Rev. X 5 , 011007 (2015).

Horn, J. L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30 , 179–185 (1965).

Xie, X., Chen, W., Lei, L., Xing, C. & Zhang, Y. The relationship between personality types and prosocial behavior and aggression in Chinese adolescents. Pers. Individ. Dif. 95 , 56–61 (2016).

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Brent, L. J. & Costa, P. T. Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Psychol. Aging 20 , 493–506 (2005).

Meeus, W., Van de Schoot, R., Klimstra, T. & Branje, S. Personality types in adolescence: change and stability and links with adjustment and relationships: a five-wave longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 47 , 1181–1195 (2011).

Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, M. W. Personality and Individual Differences: a Natural Science Approach (Plenum Press, New York, NY, 1985).

Johnson, J. A. Measuring thirty facets of the Five Factor model with a 120-item public domain inventory: development of the IPIP-NEO-120. J. Res. Pers. 51 , 78–89 (2014).

Condon, D. M. The SAPA personality inventory: an empirically-derived, hierarchically-organized self-report personality assessment model. Preprint at https://psyarxiv.com/sc4p9/ (2018).

Vazire, S. & Mehl, M. Knowing me, knowing you: the accuracy and unique predictive validity of self-ratings and other-ratings of daily behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95 , 1202–1216 (2008).

Paulhus, D. L. & Vazire, S. in Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology (eds Robins, R. W. et al.) 224–239 (Guilford, New York, NY, 2007).

Chapman, B. & Goldberg, L. Replicability and 40-year predictive power of childhood ARC types. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101 , 593–606 (2011).

Steca, P., Alessandri, G. & Caprara, G. V. The utility of a well-known personality typology in studying successful aging: resilients, undercontrollers, and overcontrollers in old age. Pers. Individ. Dif. 48 , 442–446 (2010).

Kosinski, M., Matz, S., Gosling, S., Popov, V. & Stillwell, D. Facebook as a social science research tool: opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations and practical guidelines. Am. Psychol. 70 , 543–556 (2015).

University of Cambridge, Department of Psychology, British Broadcasting Corporation BBC Big Personality Test, 2009–2011: Dataset for Mapping Personality across Great Britain [data collection] (UK Data Service, 2015); https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7656-1

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S. & John, O. P. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. Am. Psychol. 59 , 93–104 (2004).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning 2nd edn (Springer, New York, NY, 2009).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12 , 2825–2830 (2011).

Kaiser, H. F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 23 , 187–200 (1958).

Factor rotation. Python code for factor rotation (GitHub, 2017); http://github.com/mvds314/factor_rotation

Carrol, J. An analytical solution for approximating simple structure in factor analysis. Psychometrika 18 , 23–38 (1953).

Bishop, C. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Springer, New York, NY, 2006).

Download references

Acknowledgements

L.A.N.A. thanks the John and Leslie McQuown Gift and support from the Department of Defense Army Research Office under grant number W911NF-14-1-0259. W.R.’s work was partially supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation: SMA-1419324. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank J. Johnson for making the Johnson-300 and the Johnson-120 data sets publicly available; D. Stillwell, M. Kosinski and the myPersonality project for sharing the myPersonality-100 data; and the BBC LabUK for making the BBC-44 data set publicly available.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Martin Gerlach, Beatrice Farb & Luís A. Nunes Amaral

Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

William Revelle

Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Luís A. Nunes Amaral

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Department of Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.G., B.F., W.R. and L.A.N.A. designed the research. M.G., B.F., W.R. and L.A.N.A. performed the research. M.G. and B.F. analysed the data. M.G., W.R. and L.A.N.A. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luís A. Nunes Amaral .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Figures 1–17; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Methods; Supplementary References

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gerlach, M., Farb, B., Revelle, W. et al. A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets. Nat Hum Behav 2 , 735–742 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0419-z

Download citation

Received : 17 January 2018

Accepted : 25 July 2018

Published : 17 September 2018

Issue Date : October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0419-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Searching for successful psychopathy: a typological approach.

- Moritz Michels

- Marcus Roth

Current Psychology (2023)

Resilient entrepreneurs? — revisiting the relationship between the Big Five and self-employment

- Petrik Runst

Small Business Economics (2023)

Personality type matters: Perceptions of job demands, job resources, and their associations with work engagement and mental health

- Raphael M. Herr

- Annelies E. M. van Vianen

- Joachim E. Fischer

Towards a typology of risk preference: Four risk profiles describe two-thirds of individuals in a large sample of the U.S. population

- Renato Frey

- Shannon M. Duncan

- Elke U. Weber

Journal of Risk and Uncertainty (2023)

Whole-brain white matter correlates of personality profiles predictive of subjective well-being

- Raviteja Kotikalapudi

- Mihai Dricu

- Tatjana Aue

Scientific Reports (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Personality types revisited–a literature-informed and data-driven approach to an integration of prototypical and dimensional constructs of personality description

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg Germany

Affiliation Personality Psychology and Psychological Assessment Unit, Helmut Schmidt University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

- André Kerber,

- Marcus Roth,

- Philipp Yorck Herzberg

- Published: January 7, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849

- Peer Review

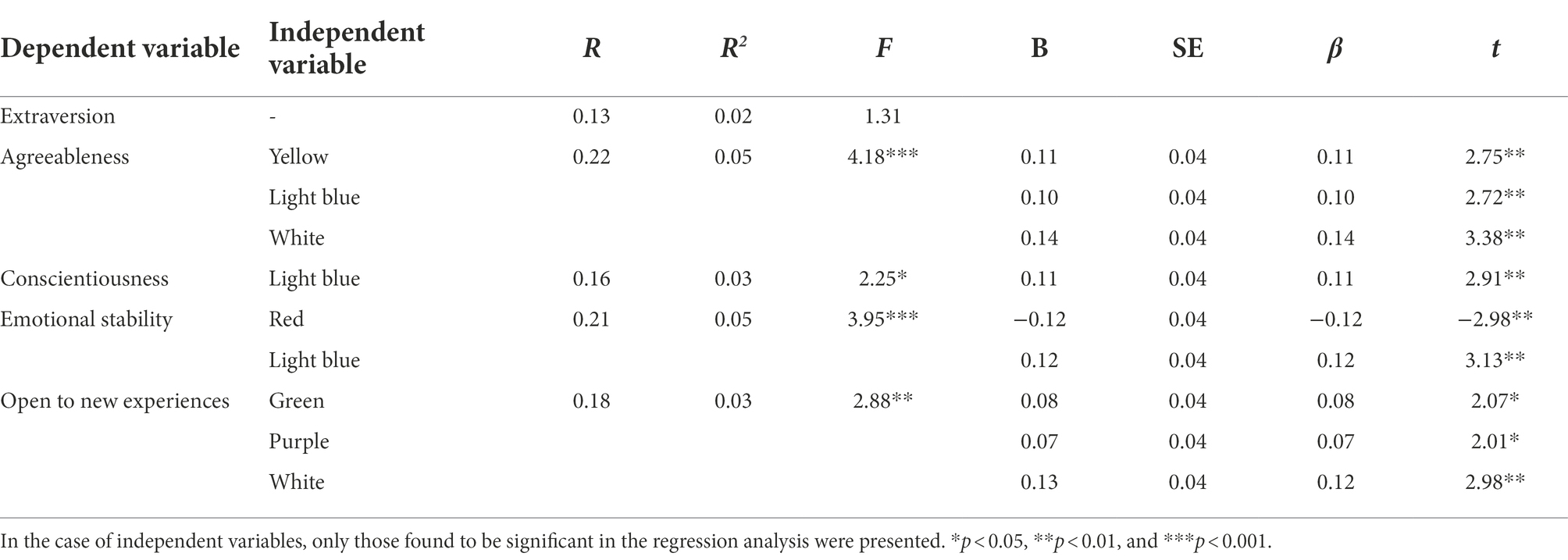

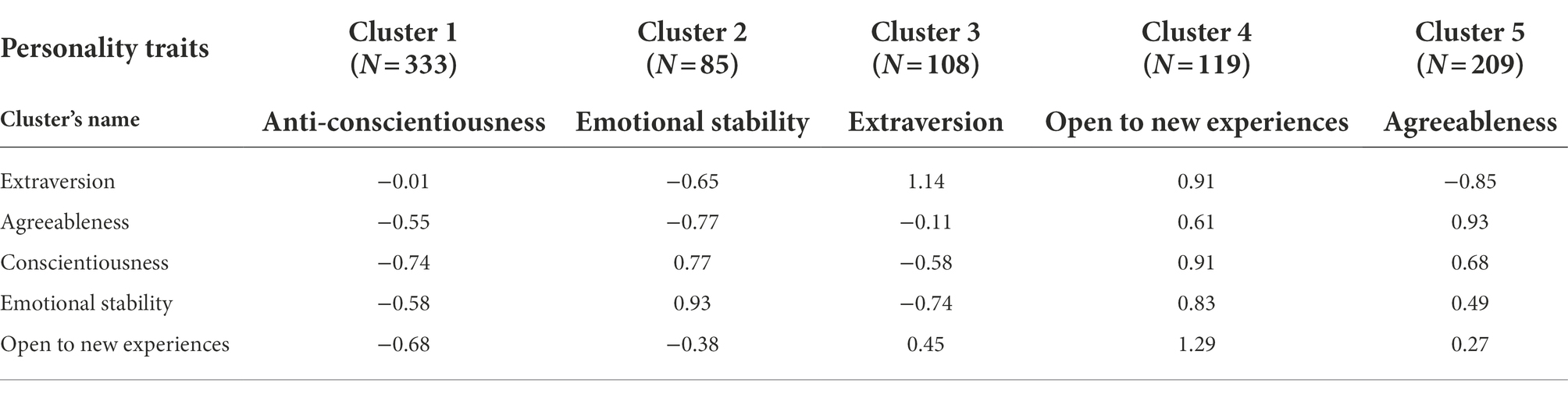

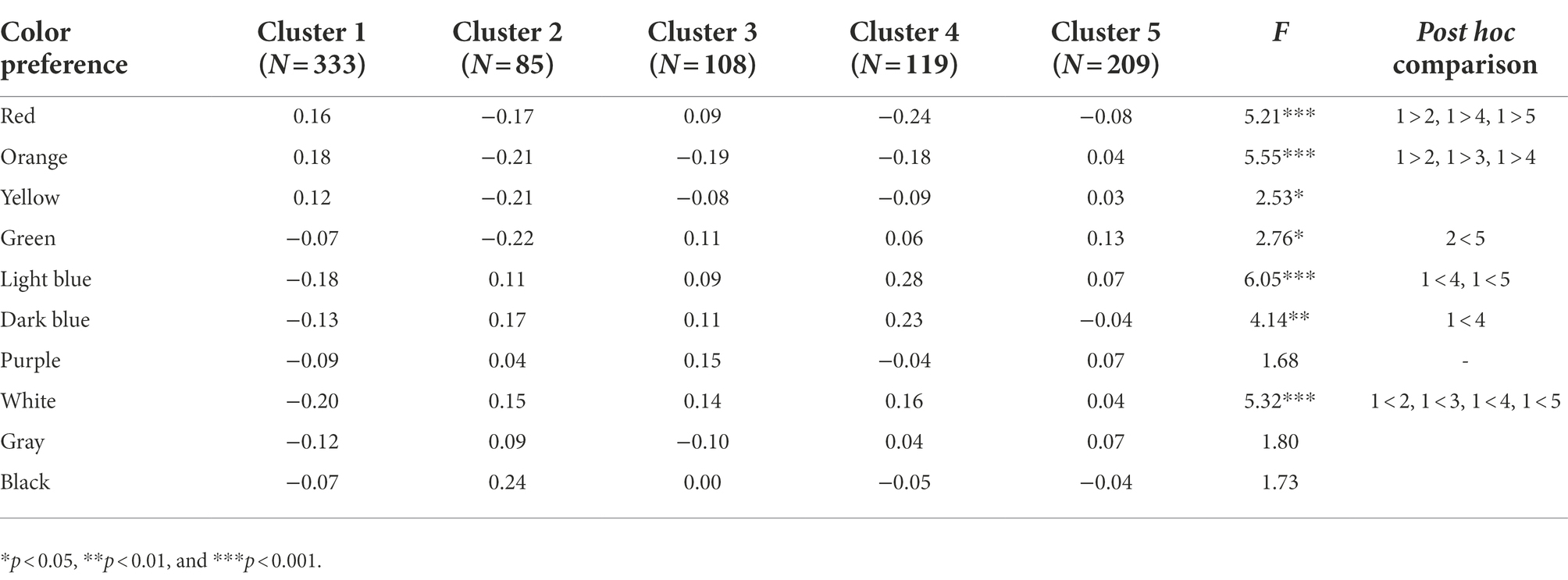

- Reader Comments

A new algorithmic approach to personality prototyping based on Big Five traits was applied to a large representative and longitudinal German dataset (N = 22,820) including behavior, personality and health correlates. We applied three different clustering techniques, latent profile analysis, the k-means method and spectral clustering algorithms. The resulting cluster centers, i.e. the personality prototypes, were evaluated using a large number of internal and external validity criteria including health, locus of control, self-esteem, impulsivity, risk-taking and wellbeing. The best-fitting prototypical personality profiles were labeled according to their Euclidean distances to averaged personality type profiles identified in a review of previous studies on personality types. This procedure yielded a five-cluster solution: resilient, overcontroller, undercontroller, reserved and vulnerable-resilient. Reliability and construct validity could be confirmed. We discuss wether personality types could comprise a bridge between personality and clinical psychology as well as between developmental psychology and resilience research.

Citation: Kerber A, Roth M, Herzberg PY (2021) Personality types revisited–a literature-informed and data-driven approach to an integration of prototypical and dimensional constructs of personality description. PLoS ONE 16(1): e0244849. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849

Editor: Stephan Doering, Medical University of Vienna, AUSTRIA

Received: January 5, 2020; Accepted: December 17, 2020; Published: January 7, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Kerber et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data used in this article were made available by the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, Data for years 1984-2015) at the German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, Germany. To ensure the confidentiality of respondents’ information, the SOEP adheres to strict security standards in the provision of SOEP data. The data are reserved exclusively for research use, that is, they are provided only to the scientific community. To require full access to the data used in this study, it is required to sign a data distribution contract. All contact informations and the procedure to request the data can be obtained at: https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222829.en/access_and_ordering.html .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Although documented theories about personality types reach back more than 2000 years (i.e. Hippocrates’ humoral pathology), and stereotypes for describing human personality are also widely used in everyday psychology, the descriptive and variable-oriented assessment of personality, i.e. the description of personality on five or six trait domains, has nowadays consolidated its position in modern personality psychology.

In recent years, however, the person-oriented approach, i.e. the description of an individual personality by its similarity to frequently occurring prototypical expressions, has amended the variable-oriented approach with the addition of valuable insights into the description of personality and the prediction of behavior. Focusing on the trait configurations, the person-oriented approach aims to identify personality types that share the same typical personality profile [ 1 ].

Nevertheless, the direct comparison of the utility of person-oriented vs. variable-oriented approaches to personality description yielded mixed results. For example Costa, Herbst, McCrae, Samuels and Ozer [ 2 ] found a higher amount of explained variance in predicting global functioning, geriatric depression or personality disorders for the variable-centered approach using Big Five personality dimensions. But these results also reflect a methodological caveat of this approach, as the categorical simplification of dimensionally assessed variables logically explains less variance. Despite this, the person-centered approach was found to heighten the predictability of a person’s behavior [ 3 , 4 ] or the development of adolescents in terms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms or academic success [ 5 , 6 ], problem behavior, delinquency and depression [ 7 ] or anxiety symptoms [ 8 ], as well as stress responses [ 9 ] and social attitudes [ 10 ]. It has also led to new insights into the function of personality in the context of other constructs such as adjustment [ 2 ], coping behavior [ 11 ], behavioral activation and inhibition [ 12 ], subjective and objective health [ 13 ] or political orientation [ 14 ], and has greater predictive power in explaining longitudinally measured individual differences in more temperamental outcomes such as aggressiveness [ 15 ].

However, there is an ongoing debate about the appropriate number and characteristics of personality prototypes and whether they perhaps constitute an methodological artifact [ 16 ].

With the present paper, we would like to make a substantial contribution to this debate. In the following, we first provide a short review of the personality type literature to identify personality types that were frequently replicated and calculate averaged prototypical profiles based on these previous findings. We then apply multiple clustering algorithms on a large German dataset and use those prototypical profiles generated in the first step to match the results of our cluster analysis to previously found personality types by their Euclidean distance in the 5-dimensional space defined by the Big Five traits. This procedure allows us to reliably link the personality prototypes found in our study to previous empirical evidence, an important analysis step lacking in most previous studies on this topic.

The empirical ground of personality types

The early studies applying modern psychological statistics to investigate personality types worked with the Q-sort procedure [ 1 , 15 , 17 ], and differed in the number of Q-factors. With the Q-Sort method, statements about a target person must be brought in an order depending on how characteristic they are for this person. Based on this Q-Sort data, prototypes can be generated using Q-Factor Analysis, also called inverse factor analysis. As inverse factor analysis is basically interchanging variables and persons in the data matrix, the resulting factors of a Q-factor analysis are prototypical personality profiles and not hypothetical or latent variable dimensions. On this basis, personality types (groups of people with similar personalities) can be formed in a second step by assigning each person to the prototype with whose profile his or her profile correlates most closely. All of these early studies determined at least three prototypes, which were labeled resilient, overcontroler and undercontroler grounded in Block`s theory of ego-control and ego-resiliency [ 18 ]. According to Jack and Jeanne Block’s decade long research, individuals high in ego-control (i.e. the overcontroler type) tend to appear constrained and inhibited in their actions and emotional expressivity. They may have difficulty making decisions and thus be non-impulsive or unnecessarily deny themselves pleasure or gratification. Children classified with this type in the studies by Block tend towards internalizing behavior. Individuals low in ego-control (i.e. the undercontroler type), on the other hand, are characterized by higher expressivity, a limited ability to delay gratification, being relatively unattached to social standards or customs, and having a higher propensity to risky behavior. Children classified with this type in the studies by Block tend towards externalizing behavior.

Individuals high in Ego-resiliency (i.e. the resilient type) are postulated to be able to resourcefully adapt to changing situations and circumstances, to tend to show a diverse repertoire of behavioral reactions and to be able to have a good and objective representation of the “goodness of fit” of their behavior to the situations/people they encounter. This good adjustment may result in high levels of self-confidence and a higher possibility to experience positive affect.

Another widely used approach to find prototypes within a dataset is cluster analysis. In the field of personality type research, one of the first studies based on this method was conducted by Caspi and Silva [ 19 ], who applied the SPSS Quick Cluster algorithm to behavioral ratings of 3-year-olds, yielding five prototypes: undercontrolled, inhibited, confident, reserved, and well-adjusted.

While the inhibited type was quite similar to Block`s overcontrolled type [ 18 ] and the well-adjusted type was very similar to the resilient type, two further prototypes were added: confident and reserved. The confident type was described as easy and responsive in social interaction, eager to do exercises and as having no or few problems to be separated from the parents. The reserved type showed shyness and discomfort in test situations but without decreased reaction speed compared to the inhibited type. In a follow-up measurement as part of the Dunedin Study in 2003 [ 20 ], the children who were classified into one of the five types at age 3 were administered the MPQ at age 26, including the assessment of their individual Big Five profile. Well-adjusteds and confidents had almost the same profiles (below-average neuroticism and above average on all other scales except for extraversion, which was higher for the confident type); undercontrollers had low levels of openness, conscientiousness and openness to experience; reserveds and inhibiteds had below-average extraversion and openness to experience, whereas inhibiteds additionally had high levels of conscientiousness and above-average neuroticism.

Following these studies, a series of studies based on cluster analysis, using the Ward’s followed by K-means algorithm, according to Blashfield & Aldenderfer [ 21 ], on Big Five data were published. The majority of the studies examining samples with N < 1000 [ 5 , 7 , 22 – 26 ] found that three-cluster solutions, namely resilients, overcontrollers and undercontrollers, fitted the data the best. Based on internal and external fit indices, Barbaranelli [ 27 ] found that a three-cluster and a four-cluster solution were equally suitable, while Gramzow [ 28 ] found a four-cluster solution with the addition of the reserved type already published by Caspi et al. [ 19 , 20 ]. Roth and Collani [ 10 ] found that a five-cluster solution fitted the data the best. Using the method of latent profile analysis, Merz and Roesch [ 29 ] found a 3-cluster, Favini et al. [ 6 ] found a 4-cluster solution and Kinnunen et al. [ 13 ] found a 5-cluster solution to be most appropriate.

Studies examining larger samples of N > 1000 reveal a different picture. Several favor a five-cluster solution [ 30 – 34 ] while others favor three clusters [ 8 , 35 ]. Specht et al. [ 36 ] examined large German and Australian samples and found a three-cluster solution to be suitable for the German sample and a four-cluster solution to be suitable for the Australian sample. Four cluster solutions were also found to be most suitable to Australian [ 37 ] and Chinese [ 38 ] samples. In a recent publication, the authors cluster-analysed very large datasets on Big Five personality comprising more than 1,5 million online participants using Gaussian mixture models [ 39 ]. Albeit their results “provide compelling evidence, both quantitatively and qualitatively, for at least four distinct personality types”, two of the four personality types in their study had trait profiles not found previously and all four types were given labels unrelated to previous findings and theory. Another recent publication [ 40 ] cluster-analysing data of over 270,000 participants on HEXACO personality “provided evidence that a five-profile solution was optimal”. Despite limitations concerning the comparability of HEXACO trait profiles with FFM personality type profiles, the authors again decided to label their personality types unrelated to previous findings instead using agency-communion and attachment theories.

We did not include studies in this literature review, which had fewer than 199 participants or those which restricted the number of types a priori and did not use any method to compare different clustering solutions. We have made these decisions because a too low sample size increases the probability of the clustering results being artefacts. Further, a priori limitation of the clustering results to a certain number of personality types is not well reasonable on the base of previous empirical evidence and again may produce artefacts, if the a priori assumed number of clusters does not fit the data well.

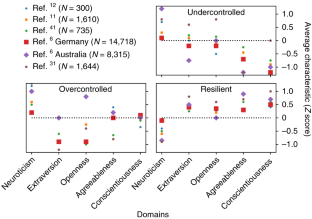

To gain a better overview, we extracted all available z-scores from all samples of the above-described studies. Fig 1 shows the averaged z-scores extracted from the results of FFM clustering solutions for all personality prototypes that occurred in more than one study. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the distribution of the z-scores of the respective trait within the same personality type throughout the different studies. Taken together the resilient type was replicated in all 19 of the mentioned studies, the overcontroler type in 16, the undercontroler personality type in 17 studies, the reserved personality type was replicated in 6 different studies, the confident personality type in 4 and the non-desirable type was replicated twice.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Average Big Five z-scores of personality types based on clustering of FFM datasets with N ≥ 199 that were replicated at least once. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the repective trait within the respective personality type found in the literature [ 5 , 6 , 10 , 22 – 25 , 27 – 31 , 33 – 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.g001

Three implications can be drawn from this figure. First, although the results of 19 studies on 26 samples with a total N of 1,560,418 were aggregated, the Big Five profiles for all types can still be clearly distinguished. In other words, personality types seem to be a phenomenon that survives the aggregation of data from different sources. Second, there are more than three replicable personality types, as there are other replicated personality types that seem to have a distinct Big Five profile, at least regarding the reserved and confident personality types. Third and lastly, the non-desirable type seems to constitute the opposite of the resilient type. Looking at two-cluster solutions on Big Five data personality types in the above-mentioned literature yields the resilient opposed to the non-desirable type. This and the fact that it was only replicated twice in the above mentioned studies points to the notion that it seems not to be a distinct type but rather a combined cluster of the over- and undercontroller personality types. Further, both studies with this type in the results did not find either the undercontroller or the overcontroller cluster or both. Taken together, five distinct personality types were consistently replicated in the literature, namely resilient, overcontroller, undercontroller, reserved and confident. However, inferring from the partly large error margin for some traits within some prototypes, not all personality traits seem to contribute evenly to the occurrence of the different prototypes. While for the overcontroler type, above average neuroticism, below average extraversion and openness seem to be distinctive, only below average conscientiousness and agreeableness seemed to be most characteristic for the undercontroler type. The reserved prototype was mostly characterized by below average openness and neuroticism with above average conscientiousness. Above average extraversion, openness and agreeableness seemed to be most distinctive for the confident type. Only for the resilient type, distinct expressions of all Big Five traits seemed to be equally significant, more precisely below average neuroticism and above average extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Research gap and novelty of this study

The cluster methods used in most of the mentioned papers were the Ward’s followed by K-means method or latent profile analysis. With the exception of Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ], Herzberg [ 33 ], Barbaranelli [ 27 ] and Steca et. al. [ 25 ], none of the studies used internal or external validity indices other than those which their respective algorithm (in most cases the SPSS software package) had already included. Gerlach et al. [ 39 ] used Gaussian mixture models in combination with density measures and likelihood measures.

The bias towards a smaller amount of clusters resulting from the utilization of just one replication index, e.g. Cohen's Kappa calculated by split-half cross-validation, which was ascertained by Breckenridge [ 42 ] and Overall & Magee [ 43 ], is probably the reason why a three-cluster solution is preferred in most studies. Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] pointed to the study by Milligan and Cooper [ 44 ], which proved the superiority of the Rand index over Cohen's Kappa and also suggested a variety of validity metrics for internal consistency to examine the construct validity of the cluster solutions.

Only a part of the cited studies had a large representative sample of N > 2000 and none of the studies used more than one clustering algorithm. Moreover, with the exception of Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] and Herzberg [ 33 ], none of the studies used a large variety of metrics for assessing internal and external consistency other than those provided by the respective clustering program they used. This limitation further adds up to the above mentioned bias towards smaller amounts of clusters although the field of cluster analysis and algorithms has developed a vast amount of internal and external validity algorithms and criteria to tackle this issue. Further, most of the studies had few or no other assessments or constructs than the Big Five to assess construct validity of the resulting personality types. Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] and Herzberg [ 33 ] as well, though using a diverse variety of validity criteria only used one clustering algorithm on a medium-sized dataset with N < 2000.

Most of these limitations also apply to the study by Specht et. al. [ 36 ], which investigated two measurement occasions of the Big Five traits in the SOEP data sample. They used only one clustering algorithm (latent profile analysis), no other algorithmic validity criteria than the Bayesian information criterion and did not utilize any of the external constructs also assessed in the SOEP sample, such as mental health, locus of control or risk propensity for construct validation.

The largest sample and most advanced clustering algorithm was used in the recent study by Gerlach et al. [ 39 ]. But they also used only one clustering algorithm, and had no other variables except Big Five trait data to assess construct validity of the resulting personality types.

The aim of the present study was therefore to combine different methodological approaches while rectifying the shortcomings in several of the studies mentioned above in order to answer the following exploratory research questions: Are there replicable personality types, and if so, how many types are appropriate and in which constellations are they more (or less) useful than simple Big Five dimensions in the prediction of related constructs?

Three conceptually different clustering algorithms were used on a large representative dataset. The different solutions of the different clustering algorithms were compared using methodologically different internal and external validity criteria, in addition to those already used by the respective clustering algorithm.

To further examine the construct validity of the resulting personality types, their predictive validity in relation to physical and mental health, wellbeing, locus of control, self-esteem, impulsivity, risk-taking and patience were assessed.

Mental health and wellbeing seem to be associated mostly with neuroticism on the variable-oriented level [ 45 ], but on a person-oriented level, there seem to be large differences between the resilient and the overcontrolled personality type concerning perceived health and well-being beyond mean differences in neuroticism [ 33 ]. This seems also to be the case for locus of control and self-esteem, which is associated with neuroticism [ 46 ] and significantly differs between resilient and overcontrolled personality type [ 33 ]. On the other hand, impulsivity and risk taking seem to be associated with all five personality traits [ 47 ] and e.g. risky driving or sexual behavior seem to occur more often in the undercontrolled personality type [ 33 , 48 ].

We chose these measures because of their empirically known differential associations to Big Five traits as well as to the above described personality types. So this both offers the opportunity to have an integrative comparison of the variable- and person-centered descriptions of personality and to assess construct validity of the personality types resulting from our analyses.

Materials and methods

The acquisition of the data this study bases on was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Basel Declaration and recommendations of the “Principles of Ethical Research and Procedures for Dealing with Scientific Misconduct at DIW Berlin”. The protocol was approved by the Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW).

The data used in this study were provided by the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) of the German institute for economic research [ 49 ]. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1 . The overall sample size of the SOEP data used in this study, comprising all individuals who answered at least one of the Big-Five personality items in 2005 and 2009, was 25,821. Excluding all members with more than one missing answers on the Big Five assessment or intradimensional answer variance more than four times higher than the sample average resulted in a total Big Five sample of N = 22,820, which was used for the cluster analyses. 14,048 of these individuals completed, in addition to the Big Five, items relevant to further constructs examined in this study that were assessed in other years. The 2013 SOEP data Big Five assessment was used as a test sample to examine stability and consistency of the final cluster solution.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.t001

The Big Five were assessed in 2005 2009 and 2013 using the short version of the Big Five inventory (BFI-S). It consists of 15 items, with internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) of the scales ranging from .5 for openness to .73 for openness [ 50 ]. Further explorations showed strong robustness across different assessment methods [ 51 ].

To measure the predictive validity, several other measures assessed in the SOEP were included in the analyses. In detail, these were:

Patience was assessed in 2008 with one item: “Are you generally an impatient person, or someone who always shows great patience?”

Risk taking.

Risk-taking propensity was assessed in 2009 by six items asking about the willingness to take risks while driving, in financial matters, in leisure and sports, in one’s occupation (career), in trusting unknown people and the willingness to take health risks, using a scale from 0 (risk aversion) to 10 (fully prepared to take risks). Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for this scale in the current sample.

Impulsivity/Spontaneity.

Impulsivity/spontaneity was assessed in 2008 with one item: Do you generally think things over for a long time before acting–in other words, are you not impulsive at all? Or do you generally act without thinking things over for long time–in other words, are you very impulsive?

Affective and cognitive wellbeing.

Affect was assessed in 2008 by four items asking about the amount of anxiety, anger, happiness or sadness experienced in the last four weeks on a scale from 1 (very rare) to 5 (very often). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .66. The cognitive satisfaction with life was assessed by 10 items asking about satisfaction with work, health, sleep, income, leisure time, household income, household duties, family life, education and housing, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .67. The distinction between cognitive and affective wellbeing stems from sociological research based on constructs by Schimmack et al. [ 50 ].

Locus of control.

The individual attitude concerning the locus of control, the degree to which people believe in having control over the outcome of events in their lives opposed to being exposed to external forces beyond their control, was assessed in 2010 with 10 items, comprising four positively worded items such as “My life’s course depends on me” and six negatively worded items such as “Others make the crucial decisions in my life”. Items were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from “does not apply” to “does apply”. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample for locus of control was .57.

Self-esteem.

Global self-esteem–a person’s overall evaluation or appraisal of his or her worth–was measured in 2010 with one item: “To what degree does the following statement apply to you personally?: I have a positive attitude toward myself”.

To assess subjective health, the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) was integrated into the SOEP questionnaire and assessed in 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010. In the present study, we used the data from 2008 and 2010. The SF-12 is a short form of the SF-36, a self-report questionnaire to assess the non-disease-specific health status [ 52 ]. Within the SF-12, items can be grouped onto two subscales, namely the physical component summary scale, with items asking about physical health correlates such as how exhausting it is to climb stairs, and the mental component summary scale, with items asking about mental health correlates such as feeling sad and blue. The literature on health measures often distinguishes between subjective and objective health measures (e.g., BMI, blood pressure). From this perspective, the SF-12 would count as a subjective health measure. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the SF-12 items was .77.

Derivation of the prototypes

The first step was to administer three different clustering methods on the Big Five data of the SOEP sample: First, the conventional linear clustering method used by Asendorpf [ 15 , 35 , 53 ] and also Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] combines the hierarchical clustering method of Ward [ 54 ] with the k-means algorithm [ 55 ]. This algorithm generates a first guess of personality types based on hierarchical clustering, and then uses this first guess as starting points for the k-means-method, which iteratively adjusts the personality profiles, i.e. the cluster means to minimize the error of allocation, i.e. participants with Big Five profiles that are allocated to two or more personality types. The second algorithm we used was latent profile analysis with Mclust in R [ 56 ], an algorithm based on probabilistic finite mixture modeling, which assumes that there are latent classes/profiles/mixture components underlying the manifest observed variables. This algorithm generates personality profiles and iteratively calculates the probability of every participant in the data to be allocated to one of the personality types and tries to minimize an error term using maximum likelihood method. The third algorithm was spectral clustering, an algorithm which initially computes eigenvectors of graph Laplacians of the similarity graph constructed on the input data to discover the number of connected components in the graph, and then uses the k-means algorithm on the eigenvectors transposed in a k-dimensional space to compute the desired k clusters [ 57 ]. As it is an approach similar to the kernel k-means algorithm [ 58 ], spectral clustering can discover non-linearly separable cluster formations. Thus, this algorithm is able, in contrast to the standard k-means procedure, to discover personality types having unequal or non-linear distributions within the Big-Five traits, e.g. having a small SD on neuroticism while having a larger SD on conscientiousness or a personality type having high extraversion and either high or low agreeableness.

Within the last 50 years, a large variety of clustering algorithms have been established, and several attempts have been made to group them. In their book about cluster analysis, Bacher et al. [ 59 ] group cluster algorithms into incomplete clustering algorithms, e.g. Q-Sort or multidimensional scaling, deterministic clustering, e.g. k-means or nearest-neighbor algorithms, and probabilistic clustering, e.g. latent class and latent profile analysis. According to Jain [ 60 ], cluster algorithms can be grouped by their objective function, probabilistic generative models and heuristics. In his overview of the current landscape of clustering, he begins with the group of density-based algorithms with linear similarity functions, e.g. DBSCAN, or probabilistic models of density functions, e.g. in the expectation-maximation (EM) algorithm. The EM algorithm itself also belongs to the large group of clustering algorithms with an information theoretic formulation. Another large group according to Jain is graph theoretic clustering, which includes several variants of spectral clustering. Despite the fact that it is now 50 years old, Jain states that k-means is still a good general-purpose algorithm that can provide reasonable clustering results.

The clustering algorithms chosen for the current study are therefore representatives of the deterministic vs. probabilistic grouping according to Bacher et. al. [ 59 ], as well as representatives of the density-based, information theoretic and graph theoretic grouping according to Jain [ 60 ].

Determining the number of clusters

There are two principle ways to determine cluster validity: external or relative criteria and internal validity indices.

External validity criteria.

External validity criteria measure the extent to which cluster labels match externally supplied class labels. If these external class labels originate from another clustering algorithm used on the same data sample, the resulting value of the external cluster validity index is relative. Another method, which is used in the majority of the cited papers in section 1, is to randomly split the data in two halves, apply a clustering algorithm on both halves, calculate the cluster means and allocate members of one half to the calculated clusters of the opposite half by choosing the cluster mean with the shortest Euclidean distance to the data member in charge. If the cluster algorithm allocation of one half is then compared with the shortest Euclidean distance allocation of the same half by means of an external cluster validity index, this results in a value for the reliability of the clustering method on the data sample.

As allocating data points/members by Euclidean distances always yields spherical and evenly shaped clusters, it will favor clustering methods that also yield spherical and evenly shaped clusters, as it is the case with standard k-means. The cluster solutions obtained with spectral clustering as well as latent profile analysis (LPA) are not (necessarily) spherical or evenly shaped; thus, allocating members of a dataset by their Euclidean distances to cluster means found by LPA or spectral clustering does not reliably represent the structure of the found cluster solution. This is apparent in Cohen’s kappa values <1 if one uses the Euclidean external cluster assignment method comparing a spectral cluster solution with itself. Though by definition, Cohen’s kappa should be 1 if the two ratings/assignments compared are identical, which is the case when comparing a cluster solution (assigning every data point to a cluster) with itself. This problem can be bypassed by allocating the members of the test dataset to the respective clusters by training a support vector machine classifier for each cluster. Support vector machines (SVM) are algorithms to construct non-linear “hyperplanes” to classify data given their class membership [ 61 ]. They can be used very well to categorize members of a dataset by an SVM-classifier trained on a different dataset. Following the rationale not to disadvantage LPA and spectral clustering in the calculation of the external validity, we used an SVM classifier to calculate the external validity criteria for all clustering algorithms in this study.

To account for the above mentioned bias to smaller numbers of clusters we applied three external validity criteria: Cohen’s kappa, the Rand index [ 62 ] and the Hubert-Arabie adjusted Rand index [ 63 ].

Internal validity criteria.

Again, to account for the bias to smaller numbers of clusters, we also applied multiple internal validity criteria selected in line with the the following reasoning: According to Lam and Yan [ 64 ], the internal validity criteria fall into three classes: Class one includes cost-function-based indices, e.g. AIC or BIC [ 65 ], whereas class two comprises cluster-density-based indices, e.g. the S_Dbw index [ 66 ]. Class three is grounded on geometric assumptions concerning the ratio of the distances within clusters compared to the distances between the clusters. This class has the most members, which differ in their underlying mathematics. One way of assessing geometric cluster properties is to calculate the within- and/or between-group scatter, which both rely on summing up distances of the data points to their barycenters (cluster means). As already explained in the section on external criteria, calculating distances to cluster means will always favor spherical and evenly shaped cluster solutions without noise, i.e. personality types with equal and linear distributions on the Big Five trait dimensions, which one will rarely encounter with natural data.

Another way not solely relying on distances to barycenters or cluster means is to calculate directly with the ratio of distances of the data points within-cluster and between-cluster. According to Desgraupes [ 67 ], this applies to the following indices: the C-index, the Baker & Hubert Gamma index, the G(+) index, Dunn and Generalized Dunn indices, the McClain-Rao index, the Point-Biserial index and the Silhouette index. As the Gamma and G(+) indices rely on the same mathematical construct, one can declare them as redundant. According to Bezdek [ 68 ], the Dunn index is very sensitive to noise, even if there are only very few outliers in the data. Instead, the authors propose several ways to compute a Generalized Dunn index, some of which also rely on the calculation of barycenters. The best-performing GDI algorithm outlined by Bezdek and Pal [ 68 ] which does not make use of cluster barycenters is a ratio of the mean distance of every point between clusters to the maximum distance between points within the cluster, henceforth called GDI31. According to Vendramin et al. [ 69 ], the Gamma, C-, and Silhouette indices are the best-performing (over 80% correct hit rate), while the worst-performing are the Point-Biserial and the McClain-Rao indices (73% and 51% correct hit rate, respectively).

Fig 2 shows a schematic overview of the procedure we used to determine the personality types Big Five profiles, i.e. the cluster centers. To determine the best fitting cluster solution, we adopted the two-step procedure proposed by Blashfield and Aldenfelder [ 21 ] and subsequently used by Asendorpf [ 15 , 35 , 53 ] Boehm [ 41 ], Schnabel [ 24 ], Gramzow [ 28 ], and Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ], with a few adjustments concerning the clustering algorithms and the validity criteria.

LPA = latent profile analysis, SVM = Support Vector Machine.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.g002

First, we drew 20 random samples of the full sample comprising all individuals who answered the Big-Five personality items in 2005 and 2009 with N = 22,820 and split every sample randomly into two halves. Second, all three clustering algorithms described above were performed on each half, saving the 3-, 4-,…,9- and 10-cluster solution. Third, participants of each half were reclassified based on the clustering of the other half of the same sample, again for every clustering algorithm and for all cluster solutions from three to 10 clusters. In contrast to Asendorpf [ 35 ], this was implemented not by calculating Euclidean distances, but by training a support vector machine classifier for every cluster of a cluster solution of one half-sample and reclassifying the members of the other half of the same sample by the SVM classifier. The advantages of this method are explained in the section on external criteria. This resulted in 20 samples x 2 halves per sample x 8 cluster solutions x 3 clustering algorithms, equaling 960 clustering solutions to be compared.

The fourth step was to compute the external criteria comparing each Ward followed by k-means, spectral, or probabilistic clustering solution of each half-sample to the clustering by the SVM classifier trained on the opposite half of the same sample, respectively. The external calculated in this step were Cohen's kappa, Rand’s index [ 62 ] and the Hubert & Arabie adjusted Rand index [ 63 ]. The fifth step consisted of averaging: We first averaged the external criteria values per sample (one value for each half), and then averaged the 20x4 external criteria values for each of the 3-,4-…, 10-cluster solutions for each algorithm.

The sixth step was to temporarily average the external criteria values for the 3-,4-,… 10-cluster solution over the three clustering algorithms and discard the cluster solutions that had a total average kappa below 0.6.

As proposed by Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ], we then calculated several internal cluster validity indices for all remaining cluster solutions. The internal validity indices which we used were, in particular, the C-index [ 70 ], the Baker-Hubert Gamma index [ 71 ], the G + index [ 72 ], the Generalized Dunn index 31 [ 68 ], the Point-Biserial index [ 44 ], the Silhouette index [ 73 ], AIC and BIC [ 65 ] and the S_Dbw index [ 66 ]. Using all of these criteria, it is possible to determine the best clustering solution in a mathematical/algorithmic manner.

The resulting clusters where then assigned names by calculating Euclidean distances to the clusters/personality types found in the literature, taking the nearest type within the 5-dimensional space defined by the respective Big Five values.

To examine the stability and consistency of the final cluster solution, in a last step, we then used the 2013 SOEP data sample to calculate a cluster solution using the algorithm and parameters which generated the solution with the best validity criteria for the 2005 and 2009 SOEP data sample. The 2013 personality prototypes were allocated to the personality types of the solution from the previous steps by their profile similarity measure D. Stability then was assessed by calculation of Rand-index, adjusted Rand-index and Cohen’s Kappa for the complete solution and for every single personality type. To generate the cluster allocations between the different cluster solutions, again we used SVM classifier as described above.

To assess the predictive and the construct validity of the resulting personality types, the inversed Euclidean distance for every participant to every personality prototype (averaged Big Five profile in one cluster) in the 5-dimensional Big-Five space was calculated and correlated with further personality, behavior and health measures mentioned above. To ensure that longitudinal reliability was assessed in this step, Big Five data assessed in 2005 were used to predict measures which where assessed three, four or five years later. The selection of participants with available data in 2005 and 2008 or later reduced the sample size in this step to N = 14,048.

Internal and external cluster fit indices

Table 2 shows the mean Cohen’s kappa values, averaged over all clustering algorithms and all 20 bootstrapped data permutations.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.t002

Whereas the LPA and spectral cluster solutions seem to have better kappa values for fewer clusters, the kappa values of the k-means clustering solutions have a peak at five clusters, which is even higher than the kappa values of the three-cluster solutions of the other two algorithms.

Considering that these values are averaged over 20 independent computations, there is very low possibility that this result is an artefact. As the solutions with more than five clusters had an average kappa below .60, they were discarded in the following calculations.

Table 3 shows the calculated external and internal validity indices for the three- to five-cluster solutions, ordered by the clustering algorithm. Comparing the validity criterion values within the clustering algorithms reveals a clear preference for the five-cluster solution in the spectral as well as the Ward followed by k-means algorithm.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.t003

Looking solely at the cluster validity results of the latent profile models, they seem to favor the three-cluster model. Yet, in a global comparison, only the S_Dbw index continues to favor the three-cluster LPA model, whereas the results of all other 12 validity indices support five-cluster solutions. The best clustering solution in terms of the most cluster validity index votes is the five-cluster Ward followed by k-means solution, and second best is the five-cluster spectral solution. It is particularly noteworthy that the five-cluster K-means solution has higher values on all external validity criteria than all other solutions. As these values are averaged over 20 independent cluster computations on random data permutations, and still have better values than solutions with fewer clusters despite the fact that these indices have a bias towards solutions with fewer clusters [ 42 ], there seems to be a substantial, replicable five-component structure in the Big Five Data of the German SOEP sample.

Description of the prototypes

The mean z-scores on the Big Five factors of the five-cluster k-means as well as the spectral solution are depicted in Fig 2 . Also depicted is the five-cluster LPA solution, which is, despite having poor internal and external validity values compared to the other two solutions, more complicated to interpret. To find the appropriate label for the cluster partitions, the respective mean z-scores on the Big Five factors were compared with the mean z-scores found in the literature, both visually and by the Euclidean distance.

The spectral and the Ward followed by k-means solution overlap by 81.3%; the LPA solution only overlaps with the other two solutions by 21% and 23%, respectively. As the Ward followed by k-means solution has the best values both for external and internal validity criteria, we will focus on this solution in the following.

The first cluster has low neuroticism and high values on all other scales and includes on average 14.4% of the participants (53.2% female; mean age 53.3, SD = 17.3). Although the similarity to the often replicated resilient personality type is already very clear merely by looking at the z-scores, a very strong congruence is also revealed by computing the Euclidean distance (0.61). The second cluster is mainly characterized by high neuroticism, low extraversion and low openness and includes on average 17.3% of the participants (54.4% female; mean age 57.6, SD = 18.2). It clearly resembles the overcontroller type, to which it also has the shortest Euclidean distance (0.58). The fourth cluster shows below-average values on the factors neuroticism, extraversion and openness, as opposed to above-average values on openness and conscientiousness. It includes on average 22.5% of the participants (45% female; mean age 56.8, SD = 17.6). Its mean z-scores closely resemble the reserved personality type, to which it has the smallest Euclidean distance (0.36). The third cluster is mainly characterized by low conscientiousness and low openness, although in the spectral clustering solution, it also has above-average extraversion and openness values. Computing the Euclidean distance (0.86) yields the closest proximity to the undercontroller personality type. This cluster includes on average 24.6% of the participants (41.3% female; mean age 50.8, SD = 18.3). The fifth cluster exhibits high z-scores on every Big Five trait, including a high value for neuroticism. Computing the Euclidean distances to the previously found types summed up in Fig 1 reveals the closest resemblance with the confident type (Euclidean distance = 0.81). Considering the average scores of the Big Five traits, it resembles the confident type from Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] and Collani and Roth [ 10 ] as well as the resilient type, with the exception of the high neuroticism score. Having above average values on the more adaptive traits while having also above average neuroticism values reminded a reviewer from a previous version of this paper of the vulnerable but invincible children of the Kauai-study [ 74 ]. Despite having been exposed to several risk factors in their childhood, they were well adapted in their adulthood except for low coping efficiency in specific stressful situations. Taken together with the lower percentage of participants in the resilient cluster in this study, compared to previous studies, we decided to name the 5 th cluster vulnerable-resilient. Consequently, only above or below average neuroticism values divided between resilient and vulnerable resilient. On average, 21.2% of the participants were allocated to this cluster (68.3% female; mean age 54.9, SD = 17.4).

Summarizing the descriptive statistics, undercontrollers were the “youngest” cluster whereas overcontrollers were the “oldest”. The mean age differed significantly between clusters ( F [4, 22820] = 116.485, p <0.001), although the effect size was small ( f = 0.14). The distribution of men and women between clusters differed significantly (c 2 [ 4 ] = 880.556, p <0.001). With regard to sex differences, it was particularly notable that the vulnerable-resilient cluster comprised only 31.7% men. This might be explained by general sex differences on the Big Five scales. According to Schmitt et al. [ 75 ], compared to men, European women show a general bias to higher neuroticism (d = 0.5), higher conscientiousness (d = 0.3) and higher extraversion and openness (d = 0.2). As the vulnerable-resilient personality type is mainly characterized by high neuroticism and above-average z-scores on the other scales, it is therefore more likely to include women. In turn, this implies that men are more likely to have a personality profile characterized mainly by low conscientiousness and low openness, which is also supported by our findings, as only 41.3% of the undercontrollers were female.

Concerning the prototypicality of the five-cluster solution compared to the mean values extracted from previous studies, it is apparent that the resilient, the reserved and the overcontroller type are merely exact replications. In contrast to previous findings, the undercontrollers differed from the previous findings cited above in terms of average neuroticism, whereas the vulnerable-resilient type differed from the previously found type (labeled confident) in terms of high neuroticism.

Stability and consistency