ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Quality of democracy makes a difference, but not for everyone: how political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy condition the relationship between democratic quality and political trust.

- Department of Knowledge Exchange and Outreach GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Cologne, Germany

In light of recent crises, not least the COVID-19 pandemic, citizen trust in the political system has been highlighted as one of the central features ensuring citizen compliance and the functioning of democracy. Given its many desirable consequences, one of the key questions is how to increase political trust among ordinary citizens. This paper investigates the role of democratic quality in determining citizens’ trust in the political system. While we know that citizens’ evaluations of democratic performance are a strong predictor of political trust, previous research has shown that trust is not always higher in political systems with higher democratic quality, indicating that democratic performance evaluations do not always correspond to actual democratic quality. Several moderating factors may account for this disconnect between democratic quality and citizens’ evaluations of democratic performance and, ultimately, political trust. For one, citizens may receive different information about the political system; second, they may process this information in different ways; and third, they may have different standards of what democratic quality ought to be. Using survey data from three rounds of the World Values Survey (2005–2020) and aggregate data on democratic quality and other macro determinants of political trust from the V-Dem project and World Development Indicators for 50 democracies around the world, this contribution empirically investigates the complex relationship between democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, and political trust in multi-level moderated mediation models. Its findings demonstrate that democratic quality affects political trust indirectly through citizens’ democratic performance evaluations and that this indirect effect is stronger for citizens with higher political interest, higher education, and especially those with more liberal conceptions of democracy.

Introduction

Ever since the seminal works of David Easton (1965, 1975) , scholars have considered political trust as essential not only for the stability but also for the smooth functioning of democracy ( Hetherington, 1998 ; Dalton, 2004 ; Letki, 2006 ; Newton, 2009 ; Marien and Hooghe, 2011 ). Especially in times of crisis, political trust serves an important function for societal cohesion and compliance. For instance, recent research on the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that citizens with higher political trust are more likely to follow recommendations on social distancing ( Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020 ; Olsen and Hjorth, 2020 ) and to engage in recommended health behavior ( Han et al., 2020 ). If we want to ensure the stability and smooth functioning of democracy in times of crisis, then, it is of paramount importance to secure the trust of ordinary citizens. Since political trust will always fluctuate in reaction to short-term stimulants like changes in government ( Anderson and LoTempio, 2002 ), the implementation of specific policies ( Bol et al., 2020 ), or economic downturns ( Armingeon and Guthmann, 2014 ), building or maintaining a reservoir of trust based on more long-term factors would help retain citizen cooperation and compliance in times of crisis. One potential avenue to build such a reservoir of trust could be a strengthening of democratic quality: as political trust reflects citizens’ attitudes toward their political system, we might expect it to be at least somewhat dependent on one of the core characteristics of this political system, the level of democracy. Yet while there is strong evidence that citizens’ democratic performance evaluations are indeed a key predictor of political trust, the relationship between a country’s democratic quality and how much trust citizens have in its core political institutions remains obscured. Whereas some studies find political trust to be higher in countries with higher democratic quality ( Mishler and Rose, 2001 ; Norris, 2011 ; van der Meer and Dekker, 2011 ), others find this relationship to hold only under certain model specifications ( Anderson and Tverdova, 2003 ; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017 ).

In an effort to shed light on this relationship, I first follow van der Meer (2017) and Mauk (2020a) in arguing that democratic quality as a macro-level phenomenon does not affect political trust as an individual-level attitude directly but rather that its effect is mediated through individual-level democratic performance evaluations. Second, I advance the theoretical discussion and dig deeper into the relationship between democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, and political trust by introducing three characteristics of citizens that may moderate this relationship: political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy.

Combining data from the World Values Survey ( Haerpfer et al., 2020 ), Varieties-of-Democracy Project ( Coppedge et al., 2020 ), and World Development Indicators ( World Bank, 2020 ) for 50 democracies worldwide, the empirical analysis uses multi-level moderated mediation models to investigate how political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy interact with democratic quality in determining democratic performance evaluations and, subsequently, political trust. The results show that democratic quality indeed affects political trust only indirectly, mediated through citizens’ democratic performance evaluations. This indirect effect is moderated by citizens’ characteristics, with democratic quality affecting political trust more among the more politically interested, the higher educated, and especially those with more liberal conceptions of democracy. The findings contribute to our understanding of the complex relationship between democratic quality and political trust: they substantiate and add to previous literature hypothesizing the link between democratic quality and political trust to run through citizens’ democratic performance evaluations, and further the discussion by providing a first account of how this indirect effect varies according to citizens’ political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Defined as citizens’ confidence that the political system, its institutions, or actors will “do what is right even in the absence of constant scrutiny” ( Miller and Listhaug, 1990 : 358), political trust is a relational concept which entails an evaluation of the relationship between the subject of trust (the citizen) and the object of trust (the political system). Determinants of trust can therefore relate to either characteristics of the individual citizen (exogeneous variables), characteristics of the political system (endogenous variables), or a combination of these two ( van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017 ).

Democratic quality is clearly a characteristic of the political system, i.e. the object of trust. Such endogenous characteristics are typically studied from a rational-choice perspective, arguing that citizens continuously form positive or negative evaluations about the political system’s performance which then form the basis for their attitudes about the political system itself ( Barry, 1970 ; Rogowski, 1974 ; Kornberg and Clarke, 1992 ). Previous research has identified citizens’ evaluations of the democratic process as one of the key determinants of political trust. Most prominently, the extent to which citizens find the political elites and institutions to be corrupt has been consistently found to exert a strong effect on both trust in institutions and satisfaction with democracy ( Seligson, 2002 ; Huang et al., 2008 ; Linde, 2012 ; Wang, 2016 ; Maciel and Sousa, 2018 ). Political freedoms, procedural fairness, free and fair elections, and accountability are other aspects of democratic quality that influence citizens’ attitudes toward the political system ( Mishler and Rose, 1997 ; Huang et al., 2008 ; Linde, 2012 ; Norris, 2014 ; Magalhães, 2016 ; Marien and Werner, 2019 ). We can therefore expect political trust to be higher when citizens evaluate the system’s democratic performance more positively.

Democratic performance evaluations are not, however, the same as democratic quality. Conceptually, democratic quality is an assessment of a political system’s structure and processes as compared to a normative benchmark. These assessments are usually based on expert judgements and most commonly relate to liberal democratic ideals, i.e. the presence of universal suffrage, electoral contestation, political participation, separation of power, rule of law, and civil liberties ( Dahl, 1971 ; Dahl, 1989 ; Morlino, 2004 ; Morlino, 2011 ; Geissel et al., 2016 ). In contrast, citizens’ democratic performance evaluations are based on each individual citizen’s conception of democracy, the information they receive, and how they process this information ( Gómez and Palacios, 2016 ; Kriesi and Saris, 2016 ; Quaranta, 2018a ). Consequently, while we find high agreement across different measures of democratic quality ( Steiner, 2016 ; Bernhagen, 2019 ; Boese, 2019 ), citizens’ evaluations of the same political system can differ vastly ( Pietsch, 2014 ). Empirically, prior research has demonstrated that citizens’ evaluations of a political system’s democratic performance hardly align with expert judgements of democratic quality ( Park, 2013 ; Bedock and Panel, 2017 ; Kruse et al., 2019 ).

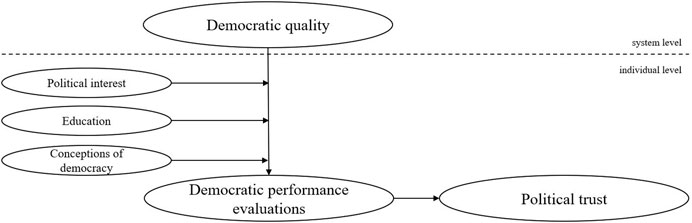

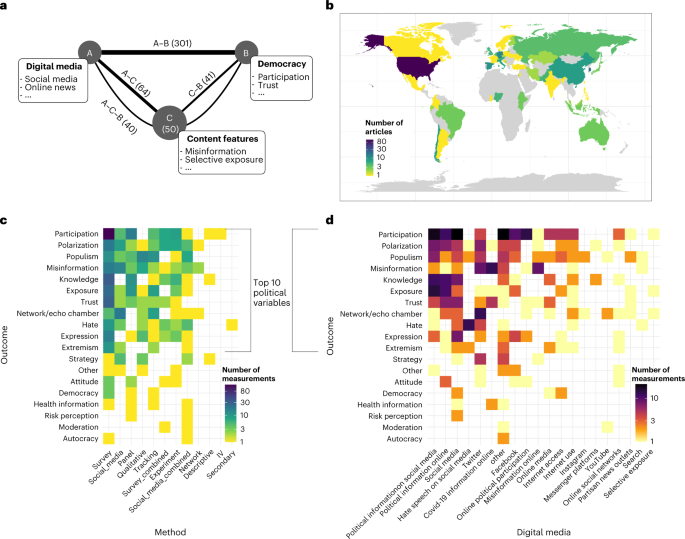

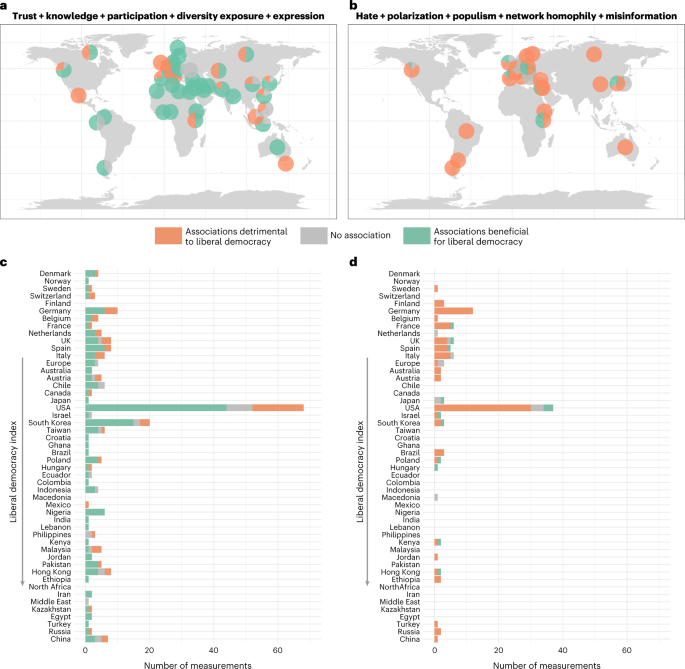

When it comes to political attitudes, unlike individual-level democratic performance evaluations, macro-level democratic quality seems to exert only a limited effect. On the one hand, previous studies find corruption to decrease both trust in political institutions and satisfaction with democracy ( Mishler and Rose, 2001 ; Anderson and Tverdova, 2003 ; van der Meer and Dekker, 2011 ; Stockemer and Sundström, 2013 ; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017 ) and citizens’ attitudes tend to be more positive in political systems with higher electoral quality or rule of law ( Norris, 2011 ; Dahlberg and Holmberg, 2014 ; Fortin-Rittberger et al., 2017 ). On the other hand, these effects mostly disappear completely once citizens’ perceptions of corruption or other evaluations of democratic performance are controlled for ( Listhaug et al., 2009 ; Stockemer and Sundström, 2013 ; Christmann, 2018 ). We may therefore expect macro-level democratic quality not to exert a direct effect on political trust but rather an indirect effect that is mediated through individual-level democratic performance evaluations (see also Figure 1 ). Results presented by van der Meer (2017) and Mauk (2020a) support the idea of an indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust.

FIGURE 1 . The theoretical linkage between democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, and political trust.

H1: Democratic quality has an indirect effect on political trust that is mediated through democratic performance evaluations.

While the second part of this indirect effect, i.e. the link between democratic performance evaluations and political trust, has received considerable scholarly attention and shall not be discussed here further, the first part, i.e. the link between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations, remains undertheorized and understudied. If we want to explain how macro-level democratic quality translates into individual-level democratic performance evaluations , we may turn to attitude-formation theories developed primarily in the field of (social) psychology. Most of these theories identify four fundamental steps of the attitude-formation process: environment, information, beliefs, and attitudes ( Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980 ; Anderson, 1981 ; Zaller, 1992 ; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010 ). Building on these theories, we can describe the process by which democratic quality (environment) translates into democratic performance evaluations (attitudes) as follows: Citizens receive information about their political system’s democratic quality which they interpret through various cognitive processes to arrive at beliefs about democratic quality. Comparing and integrating these beliefs with existing evaluative standards, citizens finally form their democratic performance evaluations.

As the huge variance of democratic performance evaluations even within the same country ( Bedock and Panel, 2017 ; Gómez and Palacios, 2016 ; Pietsch, 2014 ) suggests, this process can be distorted in several ways. As a result, the link between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations is likely to be far from uniform across citizens (see also Figure 1 ). By extension, this also means that the entire indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust may vary from citizen to citizen 1 . For one, the information citizens receive about the democratic quality of their political system can vary greatly, both in quantity and in accuracy. In general, information about democratic quality can be conveyed through two main channels: direct experience or indirect communications through the mass media and other channels ( Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975 ; Wyer and Albarracín, 2005 ). Direct experience with democratic quality may, for example, include witnessing voter intimidation on election day or being the victim of police harassment; indirect communications on democratic quality may, for example, include news coverage on a corruption scandal or social-media posts about gerrymandering. While direct experiences typically provide accurate, albeit potentially localized, information about democratic quality, not only the advent of “fake news” has cast doubt on the accuracy of indirect communications. Especially in non-democratic contexts, media freedom can be severely limited, and citizens have few means of obtaining accurate information about their country’s democratic quality through indirect communications ( Egorov et al., 2009 ; Popescu, 2011 ; Stier, 2015 ). In democracies, in contrast, the presence of media freedom and a pluralist media landscape means that accurate information about democratic quality is available from the media and other indirect channels, and the availability of information should hardly vary from citizen to citizen. What does vary, however, is the amount of information citizens receive. For both direct experience and indirect communications, those with higher political interest are more likely to receive information about the political system’s democratic quality as they are more likely to participate in politics and to follow political content on news and other media ( Verba et al., 1997 ; Strömböck et al., 2013 ; Lecheler and Vreese, 2017 ; Owens and Walker, 2018 ). As the more politically interested know more about the state of democracy in their country, i.e. hold more accurate beliefs, their democratic performance evaluations should more closely reflect the actual democratic quality of the political system. Consequently, we can expect the effect of democratic quality on democratic performance evaluations and, ultimately, the entire indirect effect democratic quality has on political trust to be larger for citizens with higher political interest.

H2: The indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust increases with political interest.

Second, the cognitive processes through which citizens interpret this information may also vary from individual to individual. Accurately processing complex information from different sources requires considerable cognitive skills, for instance to judge the credibility of the source, to weigh information from different sources, and to understand the content of the information they receive. Apart from cognitive capacity itself, one major factor determining how citizens translate information into beliefs is education ( van der Meer, 2010 ; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012 ). Ceteris paribus, we can expect those with higher education to be more likely to be able both to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources of information and to understand their content correctly. Consequently, the higher educated not only have higher political knowledge but also hold more accurate beliefs about the political system ( Seligson, 2002 ; Monsiváis-Carrillo and Cantú Ramos, 2020 ). Lending empirical support to the idea that the well-educated are better informed about their country’s democratic quality, Ananda and Bol (2020) show that providing information about democracy to citizens in Indonesia lowers satisfaction with democracy among the lower educated but not among the higher educated. If we assume that education increases the accuracy of citizens’ beliefs about their country’s democratic quality, we can expect education to have a moderating effect on the relationship between macro-level democratic quality and individual-level democratic performance evaluations as well as, by extension, political trust.

Prior research strongly supports this proposition, at least when it comes to the effect of corruption. In their study of 21 European democracies, Hakhverdian and Mayne (2012) demonstrate that corruption only has an effect on political trust for citizens with at least medium levels of education, while political trust among those with the lowest levels of education remains virtually unaffected by the amount of corruption in the respective country. This finding is corroborated by van der Meer and Hakhverdian (2017) . Additionally, van der Meer (2010) presents evidence of an interaction effect between corruption and education in 26 European democracies, finding corruption to always have a negative effect on trust in parliament but for trust to decrease more rapidly for citizens with higher education. More generally, Monsiváis-Carrillo and Cantú Ramos’ (2020) results for 18 Latin American democracies suggest that democratic quality increases satisfaction with democracy among highly educated citizens, whereas it has little to no effect among the less educated. Providing further evidence for an interaction between democratic quality and education, Ugur-Cinar et al. (2020) show that education and political trust are positively correlated in countries with low levels of corruption but that in highly corrupt countries, the more highly educated express less trust in political institutions than the less educated. Similarly, Agerberg (2019) finds education to have a weaker positive effect on what he calls “institutional attitudes” in democracies with high levels of corruption, indicating that corruption has a stronger negative effect on citizens’ attitudes among the higher educated. Overall, we can therefore expect the indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust to be larger for more highly educated citizens.

H3: The indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust increases with education.

Finally, we can expect the effect of democratic quality on political trust to vary with the standards to which citizens compare their beliefs. When it comes to such standards, previous research has predominantly examined the role of citizens’ value orientations. Scholars in the critical-citizens tradition have long argued that increasingly liberal and democratic value orientations among citizens set expectations that no real-world political system can ever meet and that this results in lower levels of political trust among citizens with stronger pro-democratic values ( Dalton, 2000 ; Dalton, 2004 ; Norris, 1999 ; Norris, 2011 ). In addition, a number of researchers have pointed to the role of education, suggesting that apart from its accuracy-inducing function (see above, hypothesis 3), education also has a norm-inducing function. According to this view, higher education elicits stronger support for core democratic values and principles ( Evans and Rose, 2007 ; Kotzian, 2011 ; Kołczyńska, 2020 ), which then leads to citizens attaching higher priority to democratic quality when evaluating their political system ( Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012 ; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017 ; Monsiváis-Carrillo and Cantú Ramos, 2020 ). Empirically, while previous studies confirm a moderating effect of education on how democratic quality relates to political trust (see above), evidence for an interaction between democratic quality and citizens’ value orientations is scarce and at best mixed. While Huhe and Tang (2017) find pro-democratic value orientations to have a more positive effect on political trust in democracies than in autocracies in their analysis of 13 East Asian political systems, Mauk’s (2020b) analysis of 102 political systems across the globe provides no empirical support for an interaction between macro-level democratic quality and citizens’ value orientations.

One potential explanation for the mixed results is that citizens’ value orientations condition the relationship between democratic performance evaluations and political trust (see also Mauk, 2020a ; Mauk, 2020b ) but not the relationship between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations. Instead, I suggest that citizens employ another standard to which they compare their beliefs about democratic quality: conceptions of democracy . This proposition builds on Torcal and Trechsel (2016) , who argue that conceptions of democracy set expectations and determine which contextual factors citizens deem most relevant when forming their evaluations of democratic performance. For beliefs about democratic quality to be translated into democratic performance evaluations, citizens must compare them to what they think constitutes high democratic quality, i.e. their conceptions of democracy. Just as political interest and education, conceptions of democracy among citizens can vary widely. Previous research has shown citizens’ conceptions of democracy to range not only from minimalist electoral conceptions to maximalist substantive conceptions but also to sometimes include elements that are clearly undemocratic from a normative perspective ( Dalton et al., 2007 ; Hernández, 2016 ; Shin and Kim, 2018 ; Ceka and Magalhães, 2020 ; Zagrebina, 2020 ). Depending on their conception of democracy, citizens will arrive at different evaluations of democratic performance even if they hold the exact same beliefs about democratic quality ( Torcal and Trechsel, 2016 ). For instance, Bedock and Panel (2017) find that French citizens with a more minimalist conception of democracy (focusing mostly on free and fair elections) tend to evaluate their political system’s democratic performance more positively than those who hold a more encompassing conception of democracy (including elements of direct democracy). Overall, the more closely citizens’ conceptions of democracy align with the academic definition of democratic quality, the more closely macro-level democratic quality should relate to individual-level democratic performance evaluations. If we follow the mainstream of scholarship and define democratic quality in primarily procedural and liberal terms ( Dahl, 1971 ; Dahl, 1989 ; Morlino, 2004 ; Morlino, 2011 ; Geissel et al., 2016 ), this means that democratic quality should have a larger effect on democratic performance evaluations and, by extension, political trust for citizens who hold more procedural and liberal conceptions of democracy. Concerning such an interaction effect between democratic quality and citizens’ conceptions of democracy, previous literature is scarce, yet unanimous. Analyzing 29 political systems in Europe, Hooghe et al. (2017) show that good governance conditions how citizens’ conceptions of democracy affect political trust, with procedural conceptions of democracy having a more positive effect on political trust in countries with higher levels of good governance. van der Meer (2017) goes one step further and examines the entire causal chain from macro-level democratic quality to individual-level political trust including the mediating effect of citizens’ democratic performance evaluations. His results for 26 European democracies evidence that the effects of macro-level impartiality on trust in parliament are mediated at least in part through citizens’ evaluations of democratic quality. Testing for the moderating effect of conceptions of democracy, he finds that both macro-level impartiality and individual-level democratic performance evaluations play a larger role in shaping political trust for citizens who understand democracy in primarily procedural terms. Investigating the link between what they call “democratic knowledge” and citizens’ evaluations of democratic performance, Wegscheider and Stark (2020) demonstrate that citizens who consider only democratic (instead of autocratic) principles as essential characteristics of democracy–i.e. hold a conception of democracy that comes closer to its scholarly definition–evaluate their own country’s democratic performance more positively in more democratic countries and more negatively in more authoritarian countries. Summing up, we can expect democratic performance evaluations to reflect macro-level democratic quality more closely for citizens who hold procedural and liberal conceptions of democracy, and consequently for the indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust to be larger for these citizens.

H4: The indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust is stronger among citizens who hold a more liberal conception of democracy.

Data and Methods

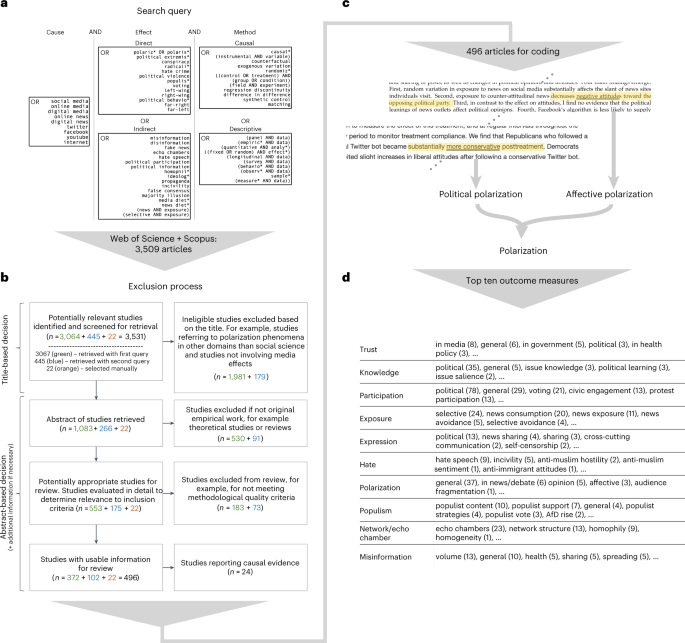

To examine how macro-level democratic quality interacts with individual-level political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy in determining citizens’ democratic performance evaluations and ultimately political trust, I combine aggregate data from the Varieties-of-Democracy project ( Coppedge et al., 2020 ) and World Development Indicators ( World Bank, 2020 ) with survey data from the World Values Survey ( Haerpfer et al., 2020 ). As the World Values Survey (WVS) has included suitable questions on democratic performance evaluations, political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy since its fifth round fielded from 2005, I can make use of three full rounds of the WVS (round five, 2005–2008; round 6, 2010–2014; round seven, 2017–2020). These data cover 50 democracies 2 in 92 country-years worldwide 3 (for a full list of countries, see Supplementary Table S1 ).

For the dependent variable political trust , I use three indicators measuring citizens’ confidence in the government, national parliament, and courts. Institutional confidence is a commonly used measure of political trust ( Dalton, 2004 ; Moehler, 2009 ; Hooghe et al., 2015 ). Taken together, the three institutions government, parliament, and courts cover all three branches of government and should thus represent citizens’ attitudes toward the political system as a whole. In all analyses, political trust will be modeled latently.

A single-item measurement captures the mediating variable democratic performance evaluations . By asking respondents how democratically they think their country is being governed today on a scale from completely undemocratic to completely democratic, the World Values Survey prompts a general and summative evaluation of democratic performance. Such a general and summative evaluation appears well-suited to my purposes as it does not provide any particular conception of democracy or emphasize any specific aspect of democratic quality, leaving citizens free to employ their own standards.

For the key independent variable, democratic quality , I employ V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Index. This index captures both electoral (universal suffrage, electoral contestation, political participation) and liberal (separation of powers, rule of law, civil liberties) components of democracy and thereby represents common conceptions of democratic quality ( Dahl, 1971 ; Dahl, 1989 ; Morlino, 2004 ; Morlino, 2011 ; Geissel et al., 2016 ).

The theoretical argument outlined above proposes three variables moderating the effect of macro-level democratic quality on individual-level democratic performance evaluations: political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy. A question asking respondents how interested they are in politics measures political interest . For education , the World Values Survey records the highest level of education respondents have completed. The most recent round of the WVS uses the 9-category ISCED-2011 classification of education, but earlier rounds use different classifications and detailed categorizations are not available for all countries. To establish a minimum level of comparability, I recode the education variable into three categories: primary education or less; at least some secondary education; at least some tertiary education. While this is far from ideal, it allows us to compare the effects of democratic quality between citizens with low education (primary or less) and those with high education (at least some tertiary). For the third moderator, citizens’ conceptions of democracy , the WVS contains a question battery asking respondents which of a list of items are essential characteristics of democracy. Even though the number and content of items varies slightly from survey round to survey round, all three rounds contain three items which capture core elements of a procedural and liberal conception of democracy: people choose their leaders in free elections; civil rights protect people from state oppression; women have the same rights as men. Following Kirsch and Welzel (2019) , I use a factor of these three items to measure liberal conceptions of democracy. All moderating variables as well as democratic quality are scaled from 0 (lowest possible value) to 1 (highest possible value) to allow for a straightforward interpretation of the cross-level interaction effects.

All empirical models control for alternative individual-level determinants of political trust: social trust ( Zmerli and Newton, 2008 ), financial satisfaction ( Catterberg and Moreno, 2005 ), and household income ( Zmerli and Newton, 2011 ). They also include age and gender as standard sociodemographics. On the macro level, the analyses control for a country’s macroeconomic performance (logged GDP per capita, annual GDP growth; van Erkel and van der Meer, 2016 ) and human development (level of education, degree of urbanization, life expectancy; Norris, 2011 ). Data for country-level education come from V-Dem, whereas urbanization, life expectancy, and macroeconomic indicators are based on the World Development Indicators ( World Bank, 2020 ). All macro-level data are matched to the survey data with a 1-year lag to ensure that citizens have had a chance to gather and process the relevant information.

To estimate the (moderated) multi-level mediation effect proposed in the hypotheses, the empirical analyses use multi-level structural equation modeling (MSEM). MSEM takes into account the hierarchical nature of the data and allows for latent estimation of the dependent variable political trust. MSEM is superior to traditional approaches to multi-level mediation analysis as it decomposes the variance of all variables into within and between variance and thereby avoids producing conflated estimates of between and within components of the indirect effect ( Meuleman, 2019 ; Preacher et al., 2010 ). All models were estimated using Mplus (version 8.4; Muthén et al., 2019 ). Given the hierarchical nature of the data and the unbalanced TSCS design where some countries were surveyed in only a single year, while other countries were surveyed in two or even three years, a three-level model structure (individuals nested in country-years nested in countries) with year dummies at the country-year level would be most appropriate. Due to the relatively low number of level-3 clusters (countries), however, models using this structure run into estimation problems ( Meuleman and Billiet, 2009 ). The main models presented here thus utilize a simpler two-level structure (individuals nested in country-years, with year dummies on the country-year level). Robustness checks show that the three-level structure yields substantially similar results, even though standard errors may not be trustworthy for these models (cf. Supplementary Table S3 , Supplementary Figure S2 ). Additional robustness checks using only the newest available data for each country in order to avoid creating an unbalanced TSCS structure also yield substantially the same results as the main models (cf. Supplementary Table S4 , Supplementary Figure S3 ). As we lack truly longitudinal data 4 , the models follow common practice and leverage between-country-year differences in democratic quality to estimate how democratic quality affects democratic performance evaluations and political trust. Model-building proceeds stepwise, starting with the direct effect of individual-level democratic performance evaluations on political trust (Model 1) before adding the direct effect of macro-level democratic quality (Model 2) and the indirect effect of democratic quality via democratic performance evaluations (Model 3). The final set of models includes cross-level interactions to examine the moderating effects of political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy on democratic performance evaluations and, by extension, on political trust (Models 4–6). By estimating the cross-level interaction between macro-level democratic quality and individual-level political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy, thanks to the symmetrical nature of the interaction term (cf. Bauer and Curran, 2005 ), these models can test not only whether these individual-level characteristics (political interest, education, conception of democracy) have a larger effect in more democratic countries but also whether democratic quality has a larger effect among the more politically interested, the more educated, and those with a more liberal conception of democracy. By combining multi-level mediation with cross-level interaction effects, these models allow us to test complex hypotheses about the origins of political trust and to study how democratic quality affects democratic performance evaluations and, eventually, political trust, differently among different people.

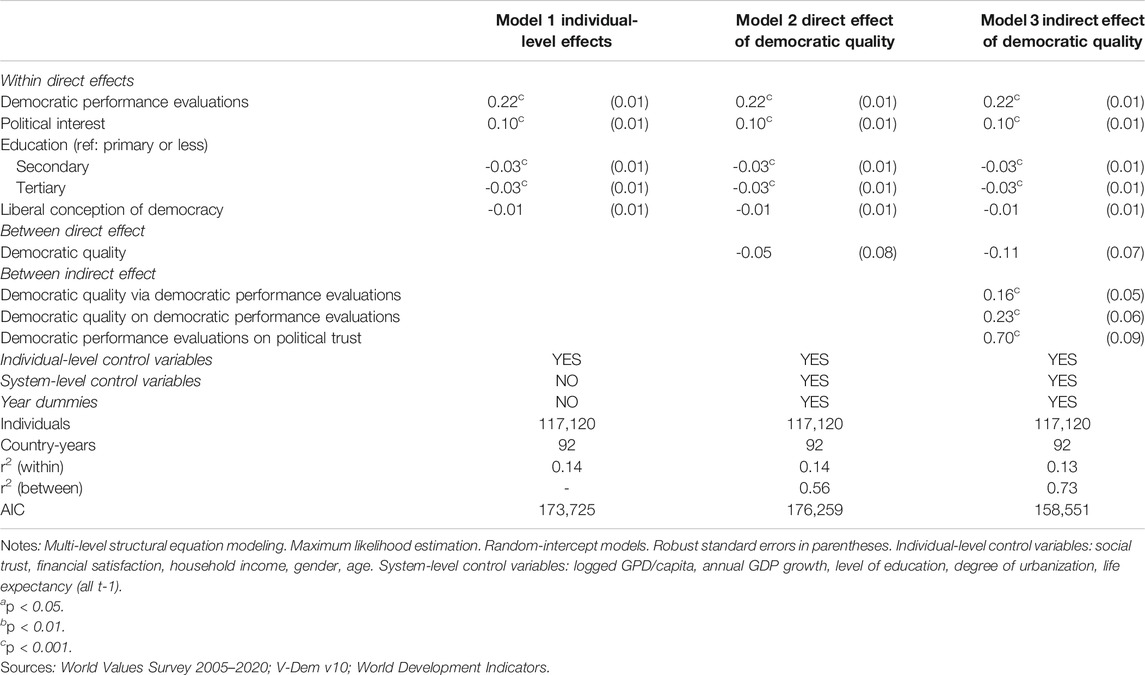

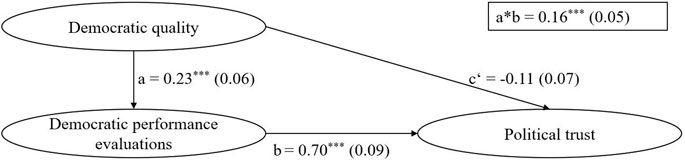

Based on the empirical analysis of 50 democracies (in 92 country-years) across the globe, Model 1 in Table 1 corroborates the bulk of previous research by confirming that individual-level democratic performance evaluations have a strong positive effect on political trust. In contrast, we observe no direct effect of macro-level democratic quality on political trust (Model 2, Table 1 ). Instead, confirming hypothesis 1, macro-level democratic quality exerts a sizable indirect effect on political trust that is mediated through individual-level democratic performance evaluations (Model 3, Table 1 ). Figure 2 depicts this indirect effect graphically. It illustrates that while democratic quality does not directly affect how much trust citizens have in their core political institutions (path c’), it strongly influences how democratic they find their country to be (path a), and these democratic performance evaluations in turn shape citizens’ political trust (path b).

TABLE 1 . Democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, and political trust.

FIGURE 2 . The indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust. Notes : Multilevel structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimation. Unstandardized estimates. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Model specifications according to Model 3 in Table 1 . * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Sources : World Values Survey 2005-2020; V-Dem v10; World Development Indicators.

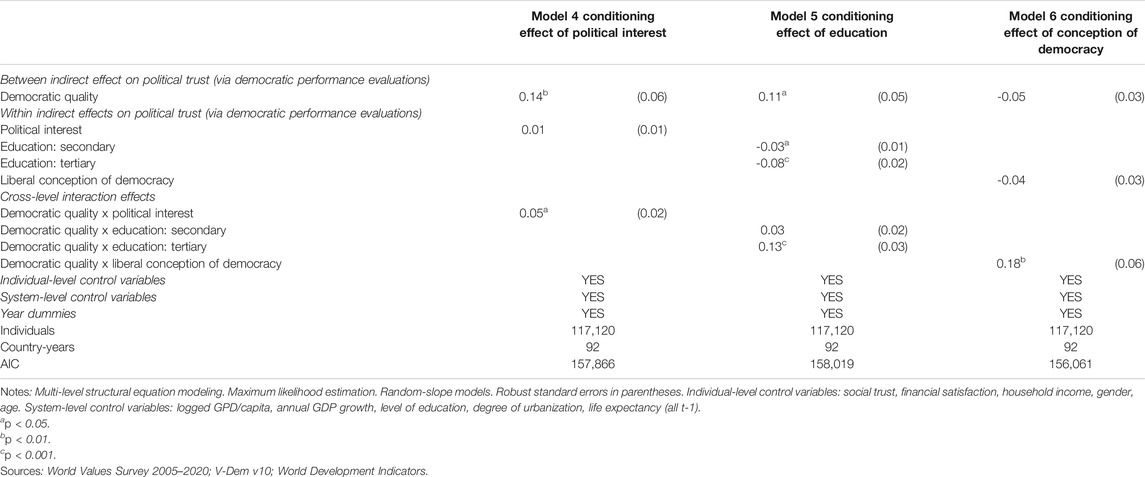

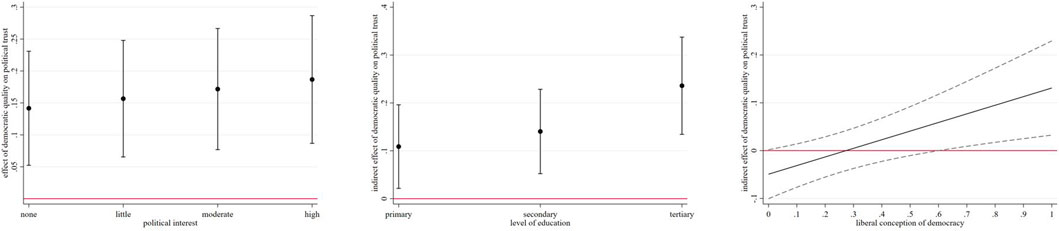

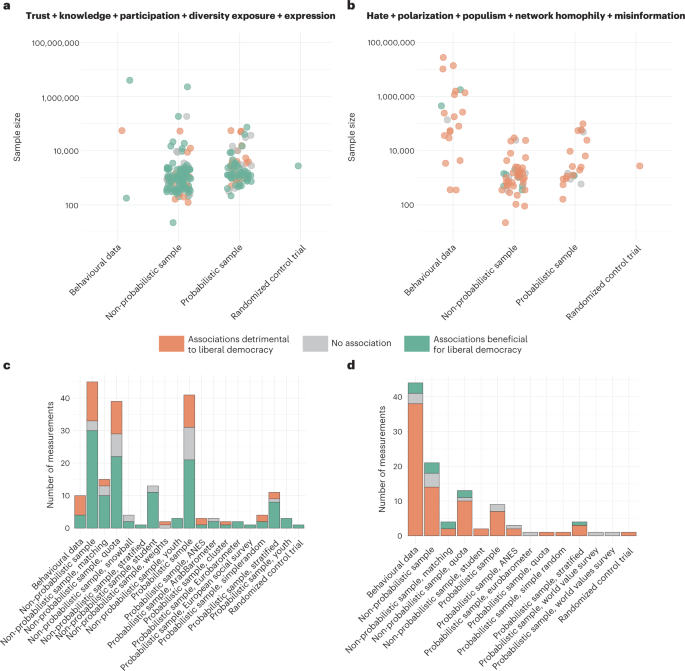

Turning to the core research question, Models 4 to 6 ( Table 2 ) investigate the cross-level interactions between democratic quality and political interest (Model 4), education (Model 5), and conceptions of democracy (Model 6). In line with the theoretical argument, which expects the relationship between macro-level democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations to vary according to citizens’ information (political interest), cognitive processes (education), and standards (conceptions of democracy), Models 4 to 6 estimate these cross-level interactions on the first part of the indirect effect (path a), i.e. the link between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations. Slopes for the second part of the indirect effect (path b), i.e. the link between democratic performance evaluations and political trust, are fixed. All variations in the overall indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust shown in Table 2 and Figure 3 will therefore solely reflect the conditionality of the relationship between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations (path a of the indirect effect). The cross-level interaction effects are introduced into the models separately and one at a time. This means that for each model, the coefficient of democratic quality can be interpreted as the indirect effect democratic quality has on political trust for citizens who score “0” on the respective moderating variable. As all moderating variables were scaled from 0 to 1, this equals the effect of democratic quality for citizens with no political interest at all (Model 4), the lowest possible level of education (Model 5), or the most illiberal conception of democracy (Model 6). The coefficient for the interaction term then represents the difference in effect size for democratic quality between these citizens and those who score “1” on the respective moderating variable, i.e. those with high political interest (Model 4), secondary or tertiary 5 education (Model 5), or the most liberal conception of democracy (Model 6). To provide some graphical representation of these numbers, Figure 3 illustrates the interactions by plotting the average marginal effects of democratic quality at different levels of the moderating variables.

TABLE 2 . The conditional effects of democratic quality on political trust.

FIGURE 3 . Conditional indirect effects of democratic quality on political trust. Notes : Multilevel structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimation. Unstandardized estimates and 95% confidence intervals of conditional effect for varying levels of political interest/education/conceptions of democracy. Model specifications according to Models 4–6 in Table 2 . Sources : World Values Survey 2005-2020; V-Dem v10; World Development Indicators.

Beginning with the moderating effect of political interest, Model 4 shows a significant, yet weak cross-level interaction between democratic quality and political interest, indicating that the indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust is at least to some extent contingent on how politically interested each individual citizen is. For those with higher political interest, democratic quality plays a larger role than for those with lower political interest. While democratic quality has a positive effect on democratic performance evaluations even for the politically uninterested, this effect is about 30% stronger for those with high political interest. Even though the difference between individual citizens is comparatively minor (see also Figure 3 ), we can still interpret this as tentative evidence for hypothesis 2 and the idea that citizens who receive more information about democratic quality generally hold more accurate beliefs about their country’s democratic quality than those who receive less information. 6

Model 5 presents empirical evidence on the moderating effect of education (hypothesis 3). Since education is a categorical variable, we need to estimate cross-level interactions between democratic quality and a dummy variable for each level of education, except the reference category (primary or less). The coefficient for the interaction term then indicates the difference in the effect of democratic quality for respondents with the respective level of education (secondary, tertiary) compared to respondents in the reference category, i.e. those with primary education or less. Looking at the results, we find no cross-level interaction between secondary education and democratic quality, indicating that democratic quality does not have a stronger indirect effect on political trust for citizens with secondary education compared to citizens with primary or less education (see also Figure 3 ). This changes for tertiary education: here, the interaction term is significant and positive, indicating that democratic quality plays a larger role for political trust among citizens with tertiary education compared to citizens who have at most primary education, with the effect size more than doubling for citizens with tertiary education. Interpreting these findings within the theoretical framework outlined above, tertiary education appears to make citizens more capable of adequately processing the information they receive about democratic quality, leading to these citizens having considerably more accurate beliefs about their country’s democratic quality than their lesser educated counterparts.

Finally, Model 6 demonstrates that conceptions of democracy exert a strong moderating effect on how democratic quality affects political trust. As evidenced by both the large coefficient for the cross-level interaction ( Table 2 ) as well as the plot in Figure 3 , the indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust varies dramatically between citizens with different conceptions of democracy. For those who hold a predominantly illiberal conception of democracy, higher democratic quality actually relates to lower political trust, indicating that these citizens apply standards that are very different from the mainstream academic definition when translating their beliefs about democratic quality into evaluations of democratic performance. This negative indirect effect of democratic quality vanishes and turns into a significant positive effect when citizens’ conceptions of democracy become more liberal. For those with the most liberal conceptions of democracy–aligning most closely with the academic definition of democratic quality–, democratic quality exerts a strong positive indirect effect on political trust, about four times the size of the (negative) effect it had for those with highly illiberal conceptions of democracy (hypothesis 4).

Summing up, the empirical evidence clearly corroborates the idea that macro-level democratic quality affects political trust only indirectly, i.e. via individual-level democratic performance evaluations. With regard to the conditionality of this indirect effect of democratic quality, the results provide at least some evidence for a moderating effect of political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy. While results were mixed for education–only tertiary education made a difference for how democratic quality affects political trust–and rather weak for political interest, the analysis found strong support for a moderating effect of conceptions of democracy, showing substantial differences between citizens with more liberal conceptions of democracy and those with more illiberal conceptions of democracy.

When it comes to the relationship between democratic quality and political trust, previous research has yielded mixed results. This contribution set out to enhance our understanding of this intricate relationship and to investigate whether and how macro-level democratic quality affects individual-level political trust. Integrating research on political trust with social psychological theories of attitude formation, it developed a theoretical framework which explicates the mechanisms that link macro-level context factors like democratic quality with individual-level attitudes like political trust and suggested a number of ways in which citizen characteristics may interact with macro-level democratic quality in shaping political trust. Utilizing multi-level structural equation models that combined mediation with moderating effects, it was able to test these complex relationships between democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, political interest, education, conceptions of democracy, and political trust. Based on a broad data base covering 50 democracies on all continents, its findings are two-fold. First, democratic quality does affect political trust, but only indirectly by shaping citizens’ democratic performance evaluations, which in turn are a core predictor of political trust. Second, this effect of democratic quality on democratic performance evaluations and, consequently, its indirect effect on political trust, is not uniform for all citizens. Instead, democratic performance evaluations correspond more closely with expert-assessed democratic quality among those with more political interest, higher education, and especially those who hold more liberal conceptions of democracy.

These results lend support not only to the basic proposition that democratic quality exerts a purely indirect effect on political trust but also to the underlying idea that citizens need to receive, process, and interpret information about their country’s democratic quality to arrive at democratic performance evaluations. As a first account of the interactions between democratic quality, political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy, they can serve as a vantage point for further theory-building and empirical analyses. For instance, future studies could gain more insight into these mechanisms by collecting data on citizens’ beliefs about democratic quality that allow for a direct test of the underlying assumptions. They could test whether those who are more politically interested actually receive more information about their country’s democratic quality and whether those with higher education are more able to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources of information as well as to correctly process this information, resulting in more accurate beliefs about democratic quality. Another emerging question is whether conceptions of democracy really serve as standards against which citizens compare their beliefs about democratic quality to translate these into democratic performance evaluations. Building on the present insights, researchers may further be interested in investigating the sources of citizens’ information and how the media landscape and citizens’ use of different media channels condition which information citizens receive, for instance whether citizens trust certain sources of information more than others and whether these sources of information differ systematically in the content and type of information they provide. The question of what sources of information citizens rely on becomes even more pressing when taking into account not only democracies but also autocracies, which guarantee not even a minimum of media freedom and where alternative sources of information may be hard to access. Moreover, given the limitations of the (survey) data, the present study could only leverage between-country differences in democratic quality to examine the relationship between democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, and political trust. Using time-series data and/or conducting case studies, future research may also want to investigate within-country effects and study whether and how citizens react to changes in democratic quality.

Despite their limitations, the present findings can provide some implications for how to secure citizens’ trust in the political system. First and foremost, they demonstrate that strengthening democracy is beneficial not only for normative reasons but can also help maintaining and winning political trust among ordinary citizens. Above all in times of crisis, political trust that is rooted in citizens’ appreciation of a political system’s democratic quality can serve as a reservoir of goodwill and contribute to ensuring social cohesion and citizen compliance with government measures. Governments might therefore wish to engage in programs aimed at improving democratic quality, for example the UNDP’s Global Program for Strengthening the Rule of Law and Human Rights ( United Nations Development Programme, 2020 ). In addition, the positive effects of such programs could be amplified through public information campaigns and other measures aimed at reaching broad segments of the population and in particular those who may otherwise not actively seek out information about the political system as well as those who may normally experience difficulties in understanding and processing such information ( Weiss and Tschirhart, 1994 ; Solovei and van den Putte, 2020 ). Finally, the findings suggest that democratic decisionmakers would be well-advised to make sure their country’s citizens have a liberal conception of democracy. Based on previous studies on sources of conceptions of democracy, this goal may also be served well by public information campaigns, as long as they include information on what democratic quality means ( Cho, 2015 ; Quaranta, 2018b ; Hernández, 2019 ). Especially in new and emerging democracies, conceptions of democracy might play a crucial role in how citizens evaluate and reward what are often incremental improvements in the quality of political institutions. At the same time, the results presented in this study tie in with the ongoing debate on democratic backsliding ( Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018 ; Waldner and Lust, 2018 ; Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019 ; Bakke and Sitter, 2020 ). In substantiating and qualifying the relationship between democratic quality and political trust, they exemplify that the curtailing of core democratic principles we are currently witnessing in countries like Poland and Hungary are likely to be met with backlash from citizens–but primarily among the politically interested, higher educated, and especially those holding more liberal conceptions of democracy.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp https://www.v-dem.net/en/ https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators . Code to recreate the dataset and to replicate the analyses in this paper is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/mmauk .

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved of its publication.

Acknowledgments

I greatly appreciate the provision of data by the World Values Survey, the Varieties-of-Democracy Project, and the World Bank. I would like to thank Antonia May, Amy Yunyu Chiang, Anne Stroppe, Tom van der Meer, and Carsten Wegscheider for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. I am most grateful to the two reviewers as well as the special issue editors for their constructive criticism and suggestions as well as the engaging discussions on the interactive review forum. The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.637344/full#supplementary-material

1 The second part of this indirect effect, i.e. the link between democratic performance evaluations and political trust, may also vary from citizen to citizen as some citizens may place greater weight on democratic performance evaluations than others when forming their attitudes about the political system as a whole (see, e.g., van der Meer, 2017 ). While such variations would also mean that the entire indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust varies between citizens, this contribution is primarily interested in how citizen characteristics condition the first part of the indirect effect, i.e. the link between macro-level democratic quality and individual-level democratic performance evaluations.

2 Countries are classified as democratic according to V-Dem’s Regimes-of-the-World (RoW) measure ( Lührmann et al., 2018 ).

3 Not every country is covered in all rounds of the WVS.

4 Most importantly, the World Values Survey is not a panel study and we therefore cannot compare characteristics on the individual level over time. Additionally, not every country is covered in every round of the World Values Survey, which results in an unbalanced TSCS design and severely limits the amount of time-series data we could use even for a purely aggregate analysis.

5 Since education is a categorical variable, Model 5 includes cross-level interactions with dummy variables for secondary and tertiary education, respectively (reference category: primary education or less).

6 For the sake of brevity, Table 2 reports only the cross-level interactions on the total indirect effect of democratic quality on political trust. Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S1 demonstrate that the moderating effects of political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy are even stronger when looking only at the theoretically relevant part of this indirect effect, i.e. the link between democratic quality and democratic performance evaluations (path a).

Agerberg, M. (2019). The Curse of Knowledge? Education, Corruption, and Politics. Polit. Behav. 41 (2), 369–399. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9455-7

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall

Ananda, A., and Bol, D. (2020). Does Knowing Democracy Affect Answers to Democratic Support Questions? A Survey Experiment in Indonesia. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. edaa012 doi:10.1093/ijpor/edaa012

Anderson, C. J., and LoTempio, A. J. (2002). Winning, Losing and Political Trust in America. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 32 (2), 335–351. doi:10.1017/s0007123402000133

Anderson, C. J., and Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes toward Government in Contemporary Democracies. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 47 (1), 91–109. doi:10.1111/1540-5907.00007

Anderson, N. H. (1981). Foundations of Information Integration Theory . New York, London: Academic Press

Armingeon, K., and Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in Crisis? the Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007-2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 53 (3), 423–442. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Bakke, E., and Sitter, N. (2020). The EU’s Enfants Terribles: Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe since 2010. Perspect. Polit. Online first 1–16. doi:10.1017/S1537592720001292

Bargain, O., and Aminjonov, U. (2020). Trust and Compliance to Public Health Policies in Times of Covid-19. J. Public Econ. 192, 104316. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barry, B. (1970). Sociologists, Economists and Democracy . Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press

Bauer, D. J., and Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing Interactions in Fixed and Multilevel Regression: Inferential and Graphical Techniques. Multivariate Behav. Res. 40 (3), 373–400. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5

Bedock, C., and Panel, S. (2017). Conceptions of Democracy, Political Representation and Socio-Economic Well-Being: Explaining How French Citizens Assess the Degree of Democracy of Their Regime. Fr Polit. 15 (4), 389–417. doi:10.1057/s41253-017-0043-8

Bernhagen, P. (2019). “Measuring Democracy and Democratization,” in Democratization . Editors C. W. Haerpfer, P. Bernhagen, C. Welzel, and R. F. Inglehart (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 52–66.

Google Scholar

Boese, V. A. (2019). How (Not) to Measure Democracy. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 22 (2), 95–127. doi:10.1177/2233865918815571

Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., and Loewen, P. (2020). The Effect of COVID‐19 Lockdowns on Political Support: Some Good News for Democracy?. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60 (4), 497–505. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12401

Catterberg, G., and Moreno, A. (2005). The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 18 (1), 31–48. 10.1093/ijpor/edh081

Ceka, B., and Magalhães, P. C. (2020). Do the Rich and the Poor Have Different Conceptions of Democracy? Socioeconomic Status, Inequality, and the Political Status Quo. Comp. Polit. 52 (3), 383–412. doi:10.5129/001041520x15670823829196

Cho, Y. (2015). How Well Are Global Citizenries Informed about Democracy? Ascertaining the Breadth and Distribution of Their Democratic Enlightenment and its Sources. Polit. Stud. 63 (1), 240–258. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12088

Christmann, P. (2018). Economic Performance, Quality of Democracy and Satisfaction with Democracy. Elect. Stud. 53, 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.004

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., and Knutsen, C. H. (2020). V-dem Country–Year Dataset V10. Available at: https://www.v-dem.net/en/ (accessed 27 May 2020).

Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its Critics . New Haven, London: Yale University Press .

Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition . New Haven, London: Yale University Press .

Dahlberg, S., and Holmberg, S. (2014). Democracy and Bureaucracy: How Their Quality Matters for Popular Satisfaction. West Eur. Polit. 37 (3), 515–537. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.830468

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies . Oxford: Oxford University Press .

Dalton, R. J., Shin, D. C., and Jou, W. (2007). Understanding Democracy: Data from Unlikely Places. J. Democracy 18 (4), 142–156.

Dalton, R. J. (2000). “Value Change and Democracy,” in Disaffected Democracies: What's Troubling the Trilateral Countries? . Editors S. J. Pharr, and R. D. Putnam (Princeton: Princeton University Press ), 252–269.

Easton, D. (1965). A Systems Analysis of Political Life . New York: Wiley .

Easton, D. (1975). A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support. Br. J. Polit. Sci 5 (4), 435–457. doi:10.1017/s0007123400008309

Egorov, G., Guriev, S., and Sonin, K. (2009). Why Resource-Poor Dictators Allow Freer Media: A Theory and Evidence from Panel Data. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 103 (4), 645–668. doi:10.1017/s0003055409990219

Evans, G., and Rose, P. (2007). Support for Democracy in Malawi: Does Schooling Matter?. World Dev. 35 (5), 904–919. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.011

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, Menlo Park, London, Amsterdam . Don Mills, Sydney: Addison-Wesley .

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach . New York, Hove: Taylor & Francis .

Fortin-Rittberger, J., Harfst, P., and Dingler, S. C. (2017). The Costs of Electoral Fraud: Establishing the Link between Electoral Integrity, Winning an Election, and Satisfaction with Democracy. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 27 (3), 350–368. doi:10.1080/17457289.2017.1310111

Geissel, B., Kneuer, M., and Lauth, H.-J. (2016). Measuring the Quality of Democracy: Introduction. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 37 (5), 571–579. doi:10.1177/0192512116669141

Gómez, B., and Palacios, I. (2016). “Citizens' Evaluations of Democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy . Editors M. Ferrín, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 155–177. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0008

Haerpfer, C. W., Inglehart, R. F., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., et al. (2020). World Values Survey: Round Seven - Country-Pooled Datafile. Available at: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp (accessed 20 July 2020).

Hakhverdian, A., and Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional Trust, Education, and Corruption: A Micro-macro Interactive Approach. J. Polit. 74 (3), 739–750. doi:10.1017/s0022381612000412

Han, Q., Zheng, B., Cristea, M., Agostini, M., Belanger, J. J., Gutzkow, B., et al. (2020). Trust in Government and its Associations with Health Behaviour and Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Med. , 1–32. doi:10.1017/S0033291721001306

Hernández, E. (2019). Democracy Belief Systems in Europe: Cognitive Availability and Attitudinal Constraint. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 11 (4), 485–502. doi:10.1017/s1755773919000286

Hernández, E. (2016). “Europeans' Views of Democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy . Editors M. Ferrín, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 43–63. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0003

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The Political Relevance of Political Trust. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 92 (4), 791–808. doi:10.2307/2586304

Hooghe, M., Dassonneville, R., and Marien, S. (2015). The Impact of Education on the Development of Political Trust: Results from a Five-Year Panel Study Among Late Adolescents and Young Adults in Belgium. Polit. Stud. 63 (1), 123–141. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12102

Hooghe, M., Marien, S., and Oser, J. (2017). Great Expectations: The Effect of Democratic Ideals on Political Trust in European Democracies. Contemp. Polit. 23 (2), 214–230. doi:10.1080/13569775.2016.1210875

Huang, M.-h., Chang, Y.-t., and Chu, Y.-h. (2008). Identifying Sources of Democratic Legitimacy: A Multilevel Analysis. Elect. Stud. 27 (1), 45–62. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2007.11.002

Huhe, N., and Tang, M. (2017). Contingent Instrumental and Intrinsic Support: Exploring Regime Support in Asia. Polit. Stud. 65 (1), 161–178. doi:10.1177/0032321715622791

Kirsch, H., and Welzel, C. (2019). Democracy Misunderstood: Authoritarian Notions of Democracy Around the Globe. Social Forces 98 (1), 59–92. doi:10.1093/sf/soy114

Kornberg, A., and Clarke, H. D. (1992). Citizens and Community: Political Support in a Representative Democracy . New York: Cambridge University Press .

Kotzian, P. (2011). Public Support for Liberal Democracy. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 32 (1), 23–41. doi:10.1177/0192512110375938

Kołczyńska, M. (2020). Democratic Values, Education, and Political Trust. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. Online first 61 (1), 3–26. 10.1177/0020715220909881

Kriesi, H., and Saris, W. (2016). “The Structure of the Evaluations of Democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy . Editors M Ferrín, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 178–205. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0009

Kruse, S., Ravlik, M., and Welzel, C. (2019). Democracy Confused: When People Mistake the Absence of Democracy for its Presence. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 50 (3), 315–335. doi:10.1177/0022022118821437

Lecheler, S., and de Vreese, C. H. (2017). News Media, Knowledge, and Political Interest: Evidence of a Dual Role from a Field Experiment. J. Commun. 67 (4), 545–564. doi:10.1111/jcom.12314

Letki, N. (2006). Investigating the Roots of Civic Morality: Trust, Social Capital, and Institutional Performance. Polit. Behav. 28 (4), 305–325. doi:10.1007/s11109-006-9013-6

Levitsky, S., and Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die: What History Reveals about Our Future . London: Viking .

Linde, J. (2012). Why Feed the Hand that Bites You? Perceptions of Procedural Fairness and System Support in Post-Communist Democracies. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 51 (3), 410–434. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02005.x

Listhaug, O., Aardal, B., and Ellis, I. O. (2009). “Institutional Variation and Political Support: An Analysis of CSES Data from 29 Countries,” in The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems . Editor H-D. Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 311–332.

Lührmann, A., and Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about it?. Democratization 26 (7), 1095–1113. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

Lührmann, A., Tannenberg, M., and Lindberg, S. I. (2018). Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes. PaG 6 (1), 60–77. doi:10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214

Maciel, G. G., and de Sousa, L. (2018). Legal Corruption and Dissatisfaction with Democracy in the European Union. Soc. Indic Res. 140 (2), 653–674. doi:10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x

Magalhães, P. C. (2016). Economic Evaluations, Procedural Fairness, and Satisfaction with Democracy. Polit. Res. Q. 69 (3), 522–534. doi:10.1177/1065912916652238

Marien, S., and Hooghe, M. (2011). Does Political Trust Matter? an Empirical Investigation into the Relation between Political Trust and Support for Law Compliance. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50 (2), 267–291. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x

Marien, S., and Werner, H. (2019). Fair Treatment, Fair Play? the Relationship between Fair Treatment Perceptions, Political Trust and Compliant and Cooperative Attitudes Cross‐nationally. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 58 (1), 72–95. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12271

Mauk, M. (2020a). Citizen Support for Democratic and Autocratic Regimes . Oxford: Oxford University Press . doi:10.1093/oso/9780198854852.001.0001

CrossRef Full Text

Mauk, M. (2020b). Disentangling an Elusive Relationship: How Democratic Value Orientations Affect Political Trust in Different Regimes. Polit. Res. Q. 73 (2), 366–380. doi:10.1177/1065912919829832

Meuleman, B., and Billiet, J. (2009). A Monte Carlo Sample Size Study: How Many Countries Are Needed for Accurate Multilevel SEM?. Surv. Res. Methods 3 (1), 45–58.

Meuleman, B. (2019). Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling for Cross-National Comparative Research. Köln Z. Soziol 71 (S1), 129–155. doi:10.1007/s11577-019-00605-x

Miller, A. H., and Listhaug, O. (1990). Political Parties and Confidence in Government: A Comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Br. J. Polit. Sci 20 (3), 357–386. doi:10.1017/s0007123400005883

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (1997). Trust, Distrust and Skepticism: Popular Evaluations of Civil and Political Institutions in Post-Communist Societies. J. Polit. 59 (2), 418–451. doi:10.1017/s0022381600053512

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2001). What Are the Origins of Political Trust?. Comp. Polit. Stud. 34 (1), 30–62. doi:10.1177/0010414001034001002

Moehler, D. C. (2009). Critical Citizens and Submissive Subjects: Election Losers and Winners in Africa. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 39 (2), 345–366. doi:10.1017/s0007123408000513

Monsiváis-Carrillo, A., and Cantú Ramos, G. (2020). Education, Democratic Governance, and Satisfaction with Democracy: Multilevel Evidence from Latin America. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. Online first . doi:10.1177/0192512120952878

Morlino, L. (2011). Changes for Democracy: Actors, Structures, Processes . Oxford: Oxford University Press . doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199572533.001.0001

Morlino, L. (2004). What Is a 'good' Democracy?. Democratization 11 (5), 10–32. doi:10.1080/13510340412331304589

Muthén, L. K., Muthén, B., and Asparouhov, T. (2019). Mplus Version 8.4. Available at: http://www.statmodel.com/index.shtml (accessed November 19, 2019).

Newton, K. (2009). “Social and Political Trust,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior . Editors R. J. Dalton, and H-D. Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 342–361.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited . New York: Cambridge University Press . doi:10.1017/cbo9780511973383

Norris, P. (2014). Why Electoral Integrity Matters . New York: Cambridge University Press . doi:10.1017/cbo9781107280861

Norris, P. (1999). “Conclusions: The Growth of Critical Citizens and its Consequences,” in Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance . Editor P. Norris (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 257–272. doi:10.1093/0198295685.003.0013

Olsen, A. L., and Hjorth, F. (2020). Willingness to Distance in the COVID-19 Pandemic https://osf.io/xpwg2/ (accessed 20 November 2020).

Owens, M. L., and Walker, H. L. (2018). The Civic Voluntarism of “Custodial Citizens”: Involuntary Criminal Justice Contact, Associational Life, and Political Participation. Perspect. Polit. 16 (4), 990–1013. doi:10.1017/s1537592718002074

Park, C. (2013). Democratic Quality of Institutions and Regime Support in East Asia. Taiwan J. Democracy 9 (1), 93–116.

Pietsch, J. (2014). Authoritarian Durability: Public Opinion towards Democracy in Southeast Asia. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 25 (1), 31–46. doi:10.1080/17457289.2014.933836

Popescu, B. G. (2011). State Censorship: A Global Study of Press Freedom in Non-democratic Regimes. Paper presented at the MPSA Annual Conference , Chicago , March 31-April 3, 2011 .

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., and Zhang, Z. (2010). A General Multilevel SEM Framework for Assessing Multilevel Mediation. Psychol. Methods 15 (3), 209–233. doi:10.1037/a0020141

Quaranta, M. (2018a). How Citizens Evaluate Democracy: An Assessment Using the European Social Survey. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 10 (2), 191–217. doi:10.1017/s1755773917000054

Quaranta, M. (2018b). The Meaning of Democracy to Citizens across European Countries and the Factors Involved. Soc. Indic Res. 136 (3), 859–880. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1427-x

Rogowski, R. (1974). Rational Legitimacy: A Theory of Political Support . Princeton: Princeton University Press .

Seligson, M. A. (2002). The Impact of Corruption on Regime Legitimacy: A Comparative Study of Four Latin American Countries. J. Polit. 64 (2), 408–433. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00132

Shin, D. C., and Kim, H. J. (2018). How Global Citizenries Think about Democracy: An Evaluation and Synthesis of Recent Public Opinion Research. Jpn. J. Polit. Sci. 19 (2), 222–249. doi:10.1017/s1468109918000063

Solovei, A., and van den Putte, B. (2020). The Effects of Five Public Information Campaigns: The Role of Interpersonal Communication. Commun. Online first 45 (s1), 586–602. doi:10.1515/commun-2020-2089

Steiner, N. D. (2016). Comparing Freedom House Democracy Scores to Alternative Indices and Testing for Political Bias: Are US Allies Rated as More Democratic by Freedom House?. J. Comp. Pol. Anal. Res. Pract. 18 (4), 329–349. doi:10.1080/13876988.2013.877676

Stier, S. (2015). Democracy, Autocracy and the News: The Impact of Regime Type on Media Freedom. Democratization 22 (7), 1273–1295. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.964643

Stockemer, D., and Sundström, A. (2013). Corruption and Citizens' Satisfaction with Democracy in Europe: what Is the Empirical Linkage?. Z. Vgl Polit. Wiss 7 (S1), 137–157. doi:10.1007/s12286-013-0168-3

Strömböck, J., Djerf-Pierre, M., and Shehata, A. (2013). The Dynamics of Political Interest and News Media Consumption: A Longitudinal Perspective. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 25 (4), 414–435. 10.1093/ijpor/eds018

Torcal, M., and Trechsel, A. H. (2016). “Explaining Citizens' Evaluations of Democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy . Editors M. Ferrín, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 206–232. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0010

Ugur-Cinar, M., Cinar, K., and Kose, T. (2020). How Does Education Affect Political Trust?: An Analysis of Moderating Factors. Soc. Indic Res. 152 (2), 779–808. doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02463-z

United Nations Development Programme (2020). The Global Programme for Strengthening the Rule of Law and Human Rights for Sustaining Peace and Fostering Development. Available at: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/2030-agenda-for-sustainable-development/peace/rule-of-law--justice--security-and-human-rights.html (accessed 23 November 2020).

van der Meer, T., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). Political Trust as the Evaluation of Process and Performance: A Cross-National Study of 42 European Countries. Polit. Stud. 65 (1), 81–102. doi:10.1177/0032321715607514

van der Meer, T. (2010). In what We Trust? A Multi-Level Study into Trust in Parliament as an Evaluation of State Characteristics. Int. Rev. Administrative Sci. 76 (3), 517–536. doi:10.1177/0020852310372450

van der Meer, T. W., and Dekker, P. (2011). “Trustworthy States, Trusting Citizens? A Multilevel Study into Objective and Subjective Determinants of Political Trust,” in Political Trust: Why Context Matters . Editors S. Zmerli, and M. Hooghe (Colchester: ECPR Press ), 95–116.

van der Meer, T. W. (2017). “Dissecting the Causal Chain from Quality of Government to Political Support,” in Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis: Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies . Editors C. van Ham, J. Thomassen, K. Aarts, and R. Andeweg (Oxford: Oxford University Press ), 136–155.

van Erkel, P. F. A., and van der Meer, T. W. G. (2016). Macroeconomic Performance, Political Trust and the Great Recession: A Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of Within-Country Fluctuations in Macroeconomic Performance on Political Trust in 15 EU Countries, 1999-2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55 (1), 177–197. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12115

Verba, S., Burns, N., and Schlozman, K. L. (1997). Knowing and Caring about Politics: Gender and Political Engagement. J. Polit. 59 (4), 1051–1072. doi:10.2307/2998592

Waldner, D., and Lust, E. (2018). Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21 (1), 93–113. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628

Wang, C.-H. (2016). Government Performance, Corruption, and Political Trust in East Asia*. Soc. Sci. Q. 97 (2), 211–231. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12223

Wegscheider, C., and Stark, T. (2020). What Drives Citizens' Evaluation of Democratic Performance? the Interaction of Citizens' Democratic Knowledge and Institutional Level of Democracy. Z. Vgl Polit. Wiss 14 (4), 345–374. doi:10.1007/s12286-020-00467-0

Weiss, J. A., and Tschirhart, M. (1994). Public Information Campaigns as Policy Instruments. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 13 (1), 82–119. doi:10.2307/3325092

World Bank (2020). World Development Indicators, 1960-2020. Available at: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators (accessed 6 November 2020).

Wyer, R. S., and Albarracín, D. (2005). “Belief Formation, Organization, and Change: Cognitive and Motivational Influences,” in The Handbook of Attitudes . Editors D. Albarracín, B. T Johnson, and M. P. Zanna (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum ), 273–322.

Zagrebina, A. (2020). Concepts of Democracy in Democratic and Nondemocratic Countries. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 41 (2), 174–191. doi:10.1177/0192512118820716

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinions . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . doi:10.1017/cbo9780511818691

Zmerli, S., and Newton, K. (2011). “Winners, Losers and Three Types of Trust,” in Political Trust: Why Context Matters . Editors S. Zmerli, and M. Hooghe (Colchester: ECPR Press ), 67–94.

Zmerli, S., and Newton, K. (2008). Social Trust and Attitudes toward Democracy. Public Opin. Q. 72 (4), 706–724. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn054

Keywords: education, political interest, political trust, democratic quality, democratic performance evaluations, conceptions of democracy

Citation: Mauk M (2021) Quality of Democracy Makes a Difference, but Not for Everyone: How Political Interest, Education, and Conceptions of Democracy Condition the Relationship Between Democratic Quality and Political Trust. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:637344. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.637344

Received: 03 December 2020; Accepted: 19 April 2021; Published: 07 May 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Mauk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marlene Mauk, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Maduro Can Only Rule Through Fear and Terror

- Paola Bautista de Alemán

Inside Orbán’s Plan to Occupy Europe

- Kim Lane Scheppele

How Civil Society Can Confront the China Challenge — And Win

Misunderstanding Democratic Backsliding

- Thomas Carothers

- Brendan Hartnett

More from the Journal

View the Archive

October 2017, Volume 28, Issue 4

The Kremlin Emboldened: Putin Is Not Russia

- Vladimir V. Kara-Murza

More Russians are rejecting the Kremlin’s corruption and authoritarianism. They—and not the regime—are Russia’s future.

July 2020, Volume 31, Issue 3

Authoritarian Survival: Why Maduro Hasn’t Fallen

- Javier Corrales

His regime has hung onto power despite setbacks that would have toppled most democratic governments. Besides pure repression, Maduro has developed new autocratic tools that have kept Venezuela’s authoritarian state afloat.

October 2020, Volume 31, Issue 4

The Bangladesh Paradox

- Harry Blair

Despite impressive achievements in socioeconomic development, Bangladesh has struggled with establishing democracy and is now effectively under one-party rule.

July 2024, Volume 35, Issue 3

When Democracy Is on the Ballot

- Michael Ignatieff

Democracy is on dangerous ground when its fundamental rules become the main point of political contention. This is where we are today. The truth is that the institutions, not just the players, need to change.

Latest Online Exclusives

Where Conspiracy Theories Come From | Scott Radnitz There is nothing inherently menacing or antidemocratic about conspiracy theories. They can even be a source of amusement. The trouble comes when political elites weaponize them to invite violence.

Welcome to Manila’s Game of Thrones | Richard Javad Heydarian The struggle between the Marcos and Duterte clans isn’t just a battle between two houses. It is becoming a proxy fight between the United States and China for the future of the Indo-Pacific.

Why Macron’s Big Gamble Worked | Jean-Yves Camus The French president risked it all to hand the far right a stinging loss. But the celebration can’t last long. If the country is to avoid greater political chaos, voters must be encouraged to think about broader coalitions that go beyond a narrow left-right divide.

News & Updates

Is democracy bad for lgbt+ rights.

August 2024