Home / Everyday actions / 6 Claims Made by Climate Change Skeptics—and How to Respond

6 Claims Made by Climate Change Skeptics—and How to Respond

Filed Under: Everyday actions | Tagged: Climate Last updated November 1, 2022

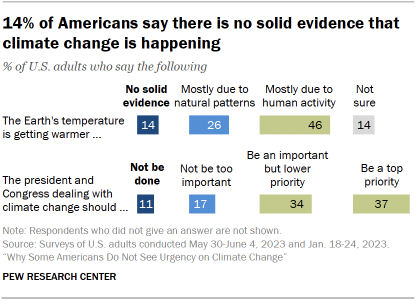

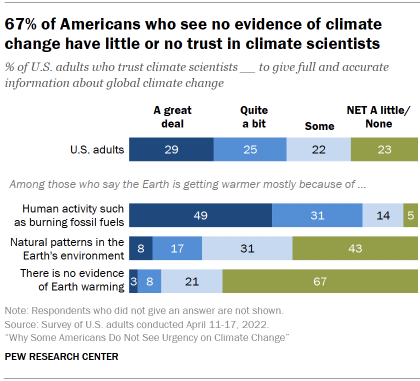

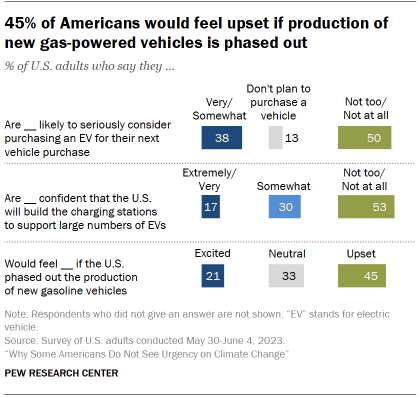

It’s hard to believe, but apparently more than a few climate change deniers still roam our ever-heating planet. According to a recent study in the esteemed science journal PLOS , people systematically understate their disbelief in human-caused climate change when answering surveys, so skepticism is more prevalent than many of us realize.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, it’s crucial that we all do our part to educate any doubters we might encounter. That’s why the Rainforest Alliance has compiled six arguments commonly made by climate change deniers, along with science-backed responses you can deploy to convince them of the truth: that climate change is real, accelerating, and that we need to take bold action ASAP.

1. Climate change denier claim: “This is the coldest winter we’ve had in years! So much for global warming.”

There’s a difference between climate and weather: Weather fluctuates day in, day out, whereas climate refers to long term trends—and the overall trend is clearly and indisputably a warming one. While the impacts of climate change have only just begun to hit the Global North, farmers in the tropics have been contending with impacts—from droughts to floods to a proliferation of crop-destroying pests—for years. That’s why the Rainforest Alliance works with farmers to take a climate-smart approach . That means first assessing a farm’s particular climate risks, taking the crop and local ecosystem into account, then finding the right combination of tools to manage the farms climate challenges. That’s what makes climate-smart agriculture “smart.”

Together, we’re building a future where people and nature thrive. Sign up today and join our movement…

2. “Climate change is natural and normal—it’s happened at other points in history.”

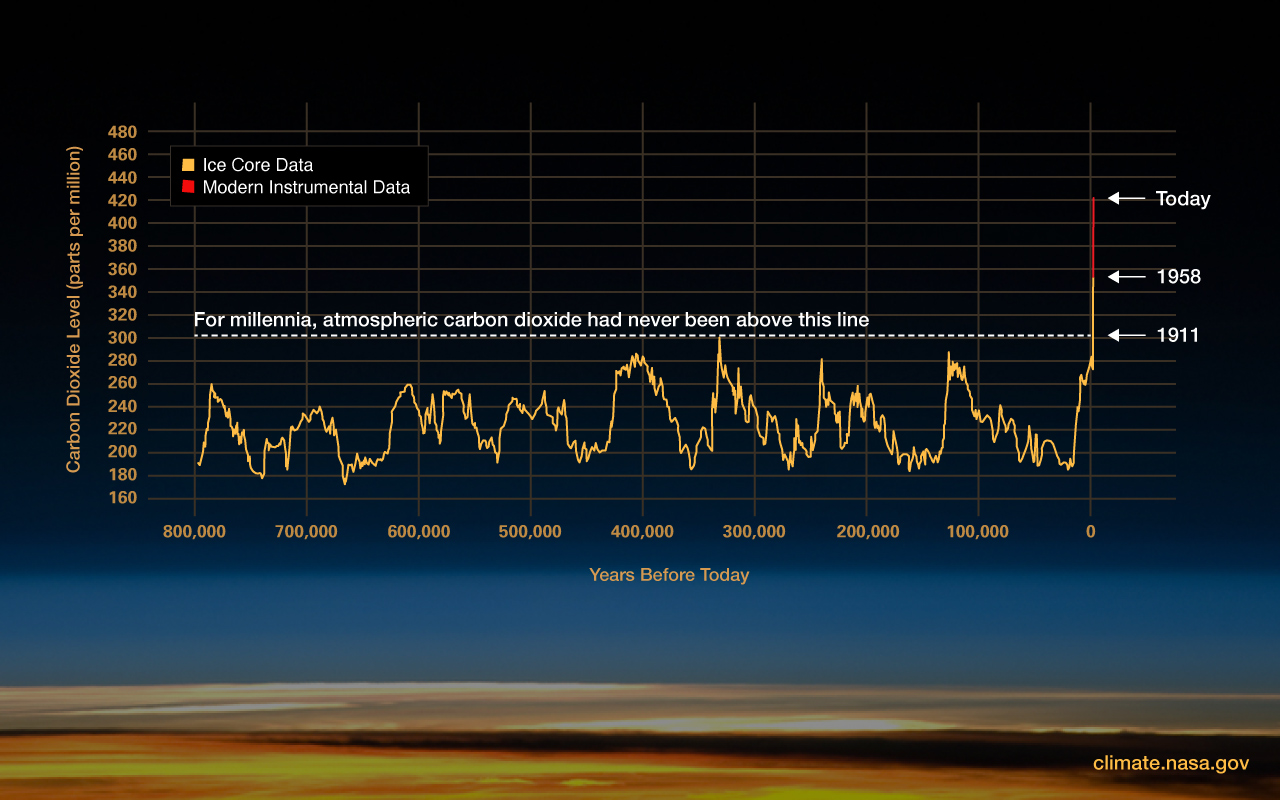

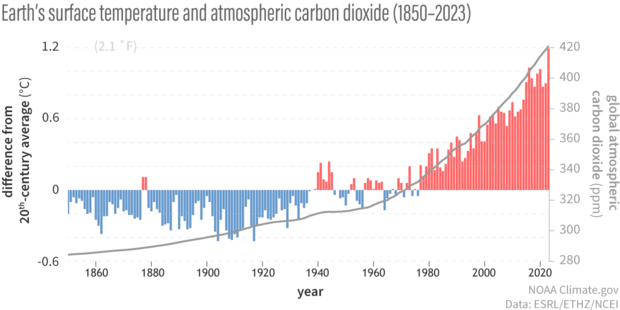

It’s true that there have been periods of global warming and cooling—also related to spikes and lulls in greenhouse gases—during the Earth’s long history. But those historic increases in CO 2 should be a warning to us: They led to serious environmental disruptions, including mass extinctions. Today, humans are emitting greenhouse gases at a far higher rate than any previous increase in history . (Before you collapse into a puddle of despair, however, find out about our work to promote natural climate solutions , like community forestry and regenerative agriculture.)

3. “There’s no consensus among scientists that climate change is real.”

Wrong. There is nearly 100 percent agreement among scientists. Moreover, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that global warming is accelerating, and will reach 1.C above pre-Industrial levels around 2030 —a full decade earlier than previously forecast .

4. “Plants and animals can adapt.”

Wrong again. Because human-caused climate change is happening so rapidly, species simply don’t have time to adapt . Frogs tell the story best: With their semi-permeable skin, unprotected eggs, and reliance on external temperatures to regulate their own, they are often among the first species to die off when ecosystems tip out of balance—and they’re dying off in droves. The Rainforest Alliance chose a frog as its mascot more than 30 years ago precisely because it’s a bio-indicator: A healthy frog population signals a healthy ecosystem, which is what we’ve been working to promote—along with thriving communities—since 1987.

5. “Climate change is good for us.”

It’s hard to even know where to begin to address this statement by climate change deniers, especially when you think about the human cost of a warming planet. The evidence points to a clear link between climate change and a surge in modern slavery : When crop failures, drought, floods, or fires wipe out livelihoods and homes, people migrate in the hopes of improving their lot—but can find themselves vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor and other human rights abuses. And the overall economic cost is staggering: The global economy could lose $23 trillion to climate change by 2050 .

6. “OK, maybe climate change is real, but there’s nothing to be done—it’s too late.”

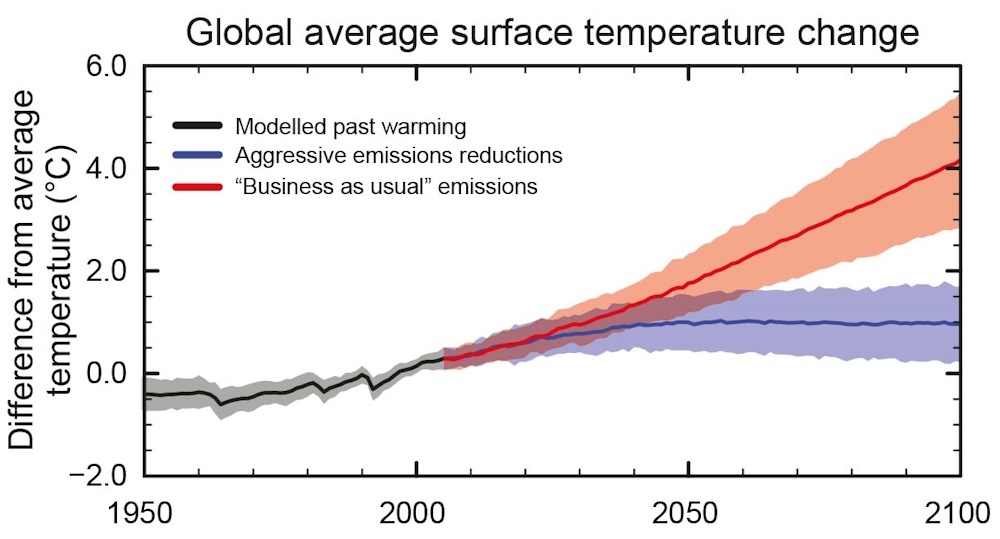

It’s true that we don’t have a moment to waste, but it’s not too late. If governments, business, and individuals begin taking drastic action now, we can keep warming within the 1.5C target set by the Paris Agreement. What can you do to make sure that happens? A lot. Here are actions you can take —both to make your daily life more sustainable and to push governments and companies to act—to secure a better future.

2023 Was One Of The Hottest Years On Record. Will 2024 Be Worse?

You might also like....

5 Ways to Build Collective Climate Impact through Individual Actions

Global Climate Strike: 5 Youth Activists Who Are Leading the Charge on Climate Action

5 of Your Favorite Foods Threatened by Climate Change

How to Talk to Kids About Climate Change (Without Freaking Them Out)

Coming soon, eudr deforestation risk assessment tool.

Does your company source cocoa and/or coffee? Sign up for our new tool to help meet your EUDR requirements.

How to use critical thinking to spot false climate claims

Lecturer in Critical Thinking, Director of the UQ Critical Thinking Project, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Peter Ellerton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Much of the public discussion about climate science consists of a stream of assertions. The climate is changing or it isn’t; carbon dioxide causes global warming or it doesn’t; humans are partly responsible or they are not; scientists have a rigorous process of peer review or they don’t, and so on.

Despite scientists’ best efforts at communicating with the public, not everyone knows enough about the underlying science to make a call one way or the other. Not only is climate science very complex, but it has also been targeted by deliberate obfuscation campaigns.

Read more: A brief history of fossil-fuelled climate denial

If we lack the expertise to evaluate the detail behind a claim, we typically substitute judgment about something complex (like climate science) with judgment about something simple (the character of people who speak about climate science).

But there are ways to analyse the strength of an argument without needing specialist knowledge. My colleagues, Dave Kinkead from the University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project and John Cook from George Mason University in the US, and I published a paper yesterday in Environmental Research Letters on a critical thinking approach to climate change denial.

We applied this simple method to 42 common climate-contrarian arguments, and found that all of them contained errors in reasoning that are independent of the science itself.

In the video abstract for the paper, we outline an example of our approach, which can be described in six simple steps.

Six steps to evaluate contrarian climate claims

Identify the claim : First, identify as simply as possible what the actual claim is. In this case, the argument is:

The climate is currently changing as a result of natural processes.

Construct the supporting argument: An argument requires premises (those things we take to be true for the purposes of the argument) and a conclusion (effectively the claim being made). The premises together give us reason to accept the conclusion. The argument structure is something like this:

- Premise one: The climate has changed in the past through natural processes

- Premise two: The climate is currently changing

- Conclusion: The climate is currently changing through natural processes.

Determine the intended strength of the claim: Determining the exact kind of argument requires a quick detour into the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning. Bear with me!

In our paper we examined arguments against climate change that are framed as definitive claims. A claim is definitive when it says something is definitely the case, rather than being probable or possible .

Definitive claims must be supported by deductive reasoning. Essentially, this means that if the premises are true, the conclusion is inevitably true.

Read more: How I came to know that I am a closet climate denier

This might sound like an obvious point, but many of our arguments are not like this. In inductive reasoning, the premises might support a conclusion but the conclusion need not be inevitable.

An example of inductive reasoning is:

- Premise one: Every time I’ve had a chocolate-covered oyster I’ve been sick

- Premise two: I’ve just had a chocolate-covered oyster

- Conclusion: I’m going to be sick.

This is not a bad argument – I’ll probably get sick – but it’s not inevitable. It’s possible that every time I’ve had a chocolate-covered oyster I’ve coincidentally got sick from something else. Perhaps previous oysters have been kept in the cupboard, but the most recent one was kept in the fridge.

Because climate-contrarian arguments are often definitive , the reasoning used to support them must be deductive . That is, the premises must inevitably lead to the conclusion.

Check the logical structure: We can see that in the argument from step two – that the climate change is changing because of natural processes – the truth of the conclusion is not guaranteed by the truth of the premises.

In the spirit of honesty and charity, we take this invalid argument and attempt to make it valid through the addition of another (previously hidden) premise.

- Premise three: If something was the cause of an event in the past, it must be the cause of the event now

Adding the third premise makes the argument valid, but validity is not the same thing as truth. Validity is a necessary condition for accepting the conclusion, but it is not sufficient. There are a couple of hurdles that still need to be cleared.

Check for ambiguity: The argument mentions climate change in its premises and conclusion. But the climate can change in many ways, and the phrase itself can have a variety of meanings. The problem with this argument is that the phrase is used to describe two different kinds of change.

Current climate change is much more rapid than previous climate change – they are not the same phenomenon. The syntax conveys the impression that the argument is valid, but it is not. To clear up the ambiguity, the argument can be presented more accurately by changing the second premise:

- Premise two: The climate is currently changing at a more rapid rate than can be explained by natural processes

This correction for ambiguity has resulted in a conclusion that clearly does not follow from the premises. The argument has become invalid once again.

We can restore validity by considering what conclusion would follow from the premises. This leads us to the conclusion:

- Conclusion: Human (non-natural) activity is necessary to explain current climate change.

Importantly, this conclusion has not been reached arbitrarily. It has become necessary as a result of restoring validity.

Note also that in the process of correcting for ambiguity and the consequent restoring of validity, the attempted refutation of human-induced climate science has demonstrably failed.

Check premises for truth or plausibility: Even if there were no ambiguity about the term “climate change”, the argument would still fail when the premises were tested. In step four, the third premise, “If something was the cause of an event in the past, it must be the cause of the event now ”, is clearly false.

Applying the same logic to another context, we would arrive at conclusions like: people have died of natural causes in the past; therefore any particular death must be from natural causes.

Restoring validity by identifying the “hidden” premises often produces such glaringly false claims. Recognising this as a false premise does not always require knowledge of climate science.

When determining the truth of a premise does require deep knowledge in a particular area of science, we may defer to experts. But there are many arguments that do not, and in these circumstances this method has optimal value.

Inoculating against poor arguments

Previous work by Cook and others has focused on the ability to inoculate people against climate science misinformation. By pre-emptively exposing people to misinformation with explanation they become “vaccinated” against it, showing “resistance” to developing beliefs based on misinformation.

Read more: Busting myths: a practical guide to countering science denial

This reason-based approach extends inoculation theory to argument analysis, providing a practical and transferable method of evaluating claims that does not require expertise in climate science.

Fake news may be hard to spot, but fake arguments don’t have to be.

- Climate change

- Climate change denial

Chief Financial Officer

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

Argumentative Essay Writing

Argumentative Essay About Climate Change

Make Your Case: A Guide to Writing an Argumentative Essay on Climate Change

Published on: Mar 2, 2023

Last updated on: Jan 31, 2024

People also read

Argumentative Essay - A Complete Writing Guide

Learn How to Write an Argumentative Essay Outline

Best Argumentative Essay Examples for Your Help

Basic Types of Argument and How to Use Them?

Take Your Pick – 200+ Argumentative Essay Topics

Essential Tips and Examples for Writing an Engaging Argumentative Essay about Abortion

Crafting a Winning Argumentative Essay on Social Media

Craft a Winning Argumentative Essay about Mental Health

Strategies for Writing a Winning Argumentative Essay about Technology

Crafting an Unbeatable Argumentative Essay About Gun Control

Win the Debate - Writing An Effective Argumentative Essay About Sports

Ready, Set, Argue: Craft a Convincing Argumentative Essay About Wearing Mask

Crafting a Powerful Argumentative Essay about Global Warming: A Step-by-Step Guide

Share this article

With the issue of climate change making headlines, it’s no surprise that this has become one of the most debated topics in recent years.

But what does it really take to craft an effective argumentative essay about climate change?

Writing an argumentative essay requires a student to thoroughly research and articulate their own opinion on a specific topic.

To write such an essay, you will need to be well-informed regarding global warming. By doing so, your arguments may stand firm backed by both evidence and logic.

In this blog, we will discuss some tips for crafting a factually reliable argumentative essay about climate change!

On This Page On This Page -->

What is an Argumentative Essay about Climate Change?

The main focus will be on trying to prove that global warming is caused by human activities. Your goal should be to convince your readers that human activity is causing climate change.

To achieve this, you will need to use a variety of research methods to collect data on the topic. You need to make an argument as to why climate change needs to be taken more seriously.

Argumentative Essay Outline about Climate Change

An argumentative essay about climate change requires a student to take an opinionated stance on the subject.

The outline of your paper should include the following sections:

Argumentative Essay About Climate Change Introduction

The first step is to introduce the topic and provide an overview of the main points you will cover in the essay.

This should include a brief description of what climate change is. Furthermore, it should include current research on how humans are contributing to global warming.

An example is:

| |

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Thesis Statement For Climate Change Argumentative Essay

The thesis statement should be a clear and concise description of your opinion on the topic. It should be established early in the essay and reiterated throughout.

For example, an argumentative essay about climate change could have a thesis statement such as:

âclimate change is caused by human activity and can be addressed through policy solutions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote cleaner energy sourcesâ. |

Climate Change Argumentative Essay Conclusion

The conclusion should restate your thesis statement and summarize the main points of the essay.

It should also provide a call to action, encouraging readers to take steps toward addressing climate change.

For example,

Climate change is an urgent issue that must be addressed now if we are to avoid catastrophic consequences in the future. We must take action to reduce our emissions and transition to cleaner energy sources. It is up to us as citizens to demand policy solutions from our governments that will ensure a safe and sustainable future. |

How To Write An Argumentative Essay On Climate Change

Writing an argumentative essay about climate change requires a student to take an opinionated stance on the subject.

Following are the steps to follow for writing an argumentative essay about climate change

Do Your Research

The first step is researching the topic and collecting evidence to back up your argument.

You should look at scientific research, articles, and data on climate change as well as current policy solutions.

Pick A Catchy Title

Once you have gathered your evidence, it is time to pick a title for your essay. It should be specific and concise.

Outline Your Essay

After selecting a title, create an outline of the main points you will include in the essay.

This should include an introduction, body paragraphs that provide evidence for your argument, and a conclusion.

Compose Your Essay

Finally, begin writing your essay. Start with an introduction that provides a brief overview of the main points you will cover and includes your thesis statement.

Then move on to the body paragraphs, providing evidence to back up your argument.

Finally, conclude the essay by restating your thesis statement and summarizing the main points.

Proofread and Revise

Once you have finished writing the essay, it is important to proofread and revise your work.

Check for any spelling or grammatical errors, and make sure the argument is clear and logical.

Finally, consider having someone else read over the essay for a fresh perspective.

By following these steps, you can create an effective argumentative essay on climate change. Good luck!

Examples Of Argumentative Essays About Climate Change

Climate Change is real and happening right now. It is one of the most urgent environmental issues that we face today.

Argumentative essays about this topic can help raise awareness that we need to protect our planet.

Below you will find some examples of argumentative essays on climate change written by CollegeEssay.orgâs expert essay writers.

Argumentative Essay About Climate Change And Global Warming

Persuasive Essay About Climate Change

Argumentative Essay About Climate Change In The Philippines

Argumentative Essay About Climate Change Caused By Humans

Geography Argumentative Essay About Climate Change

Check our extensive blog on argumentative essay examples to ace your next essay!

Good Argumentative Essay Topics About Climate Change

Choosing a great topic is essential to help your readers understand and engage with the issue.

Here are some suggestions:

- Should governments fund projects that will reduce the effects of climate change?

- Is it too late to stop global warming and climate change?

- Are international treaties effective in reducing carbon dioxide emissions?

- What are the economic implications of climate change?

- Should renewable energy be mandated as a priority over traditional fossil fuels?

- How can individuals help reduce their carbon footprint and fight climate change?

- Are regulations on industry enough to reduce global warming and climate change?

- Could geoengineering be used to mitigate climate change?

- What are the social and political effects of global warming and climate change?

- Should companies be held accountable for their contribution to climate change?

Check our comprehensive blog on argumentative essay topics to get more topic ideas!

We hope these topics and resources help you write a great argumentative essay about climate change.

Now that you know how to write an argumentative essay about climate change, itâs time to put your skills to the test.

Overwhelmed with assignments and thinking, "I wish someone could write me an essay "?

Our specialized writing service is here to turn that wish into reality. With a focus on quality, originality, and timely delivery, our team of professionals is committed to crafting essays that align perfectly with your academic goals.

And for those seeking an extra edge, our essay writer , an advanced AI tool, is ready to elevate your writing to new heights.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good introduction to climate change.

An introduction to a climate change essay can include a short description of why the topic is important and/or relevant.

It can also provide an overview of what will be discussed in the body of the essay.

The introduction should conclude with a clear, focused thesis statement that outlines the main argument in your essay.

What is a good thesis statement for climate change?

A good thesis statement for a climate change essay should state the main point or argument you will make in your essay.

You could argue that “The science behind climate change is irrefutable and must be addressed by governments, businesses, and individuals.”

Cathy A. (Medical school essay, Education)

For more than five years now, Cathy has been one of our most hardworking authors on the platform. With a Masters degree in mass communication, she knows the ins and outs of professional writing. Clients often leave her glowing reviews for being an amazing writer who takes her work very seriously.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

November 30, 2009

14 min read

7 Answers to Climate Contrarian Nonsense

Evidence for human interference with Earth’s climate continues to accumulate

By John Rennie

Alison Seiffer

President Donald Trump has consistently opposed fighting climate change. His administration loosened fuel economy and emissions standards for new motor vehicles, for example—a measure that automakers had not even requested. He replaced the Clean Power Plan championed by his predecessor, President Barack Obama, with new regulations that permit more carbon emissions from coal- and gas-burning power plants. In November 2019 he even initiated the year-long process of withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris climate accords, an agreement that required nothing from its signatories except an unenforced pledge to help keep the rise in global temperatures below two degrees Celsius.

The reasoning behind those actions has been hard to pin down. Trump has repeatedly denounced global warming as a “hoax” and a Chinese plot to undermine U.S. manufacturing. But then, in a January 2019 press conference, Trump also said “nothing’s a hoax” about climate change. Many of those he had named to head various agencies, including Rick Perry at the Department of Energy and Scott Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency, questioned or denied the role of carbon dioxide in climate change. But when reporters have directly asked whether Trump believes global warming is real, White House press secretaries have skirted the question. It’s hard to tell whether his administration is skeptical about the scientific fact of the climate crisis or simply the urgency of doing anything about it.

Ambiguity has often been weaponized by those who prefer to call themselves “climate skeptics”—although they generally seem to be more dedicated to naysaying than to genuine skeptical inquiry. Not everyone who questions climate change science fits that description, of course: some people are genuinely unaware of the facts or honestly disagree about their interpretation. What distinguishes the true naysayers is their dedicated opposition to conceding that there is an actionable problem, often with long-disproved arguments about alleged weaknesses in the science of climate change.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What follows is a partial list of the contrarians’ bad-faith arguments and some brief rebuttals of them.

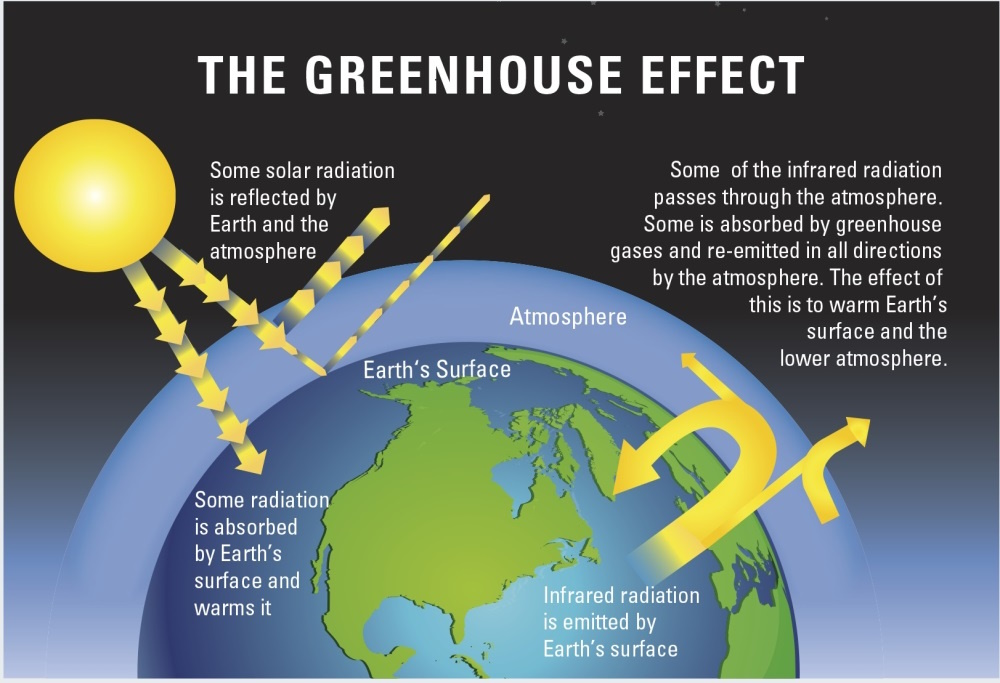

CLAIM 1: Anthropogenic carbon dioxide can’t be changing climate, because CO 2 is only a trace gas in the atmosphere and the amount produced by humans is dwarfed by the amount from volcanoes and other natural sources. Water vapor is by far the most important greenhouse gas, so changes in CO 2 are irrelevant.

Although carbon dioxide makes up only 0.04 percent of the atmosphere, that small number plays a significant role in climate dynamics. Even at that low concentration, CO 2 absorbs infrared radiation and acts as a greenhouse gas, as physicist John Tyndall demonstrated in 1859. Chemist Svante Arrhenius went further in 1896 by estimating the impact of CO 2 on the climate; after painstaking hand calculations, he concluded that doubling its concentration might cause almost six degrees Celsius of warming—an answer not much out of line with recent, far more rigorous computations.

Forests remove atmospheric CO 2 and offset the nonhuman releases of CO 2 . Human activity, combined with forest clearing ( shown here ), negates this process, however. Credit: Joel W. Rogers Getty Images

Contrary to the contrarians, human activity is by far the largest contributor to the observed increase in atmospheric CO 2 . According to the Global Carbon Project, anthropogenic CO 2 amounts to about 35 billion tons annually—more than 130 times as much as volcanoes produce. True, 95 percent of the releases of CO 2 to the atmosphere are natural, but natural processes such as plant growth and absorption into the oceans pull the gas back out of the atmosphere and almost precisely offset them, leaving the human additions as a net surplus. Moreover, several sets of experimental measurements, including analyses of the shifting ratio of carbon isotopes in the air, further confirm that fossil-fuel burning and deforestation are the primary reasons that CO 2 levels have risen 45 percent since 1832, from 284 parts per million (ppm) to 412 ppm—a remarkable jump to the highest levels seen in millions of years.

Contrarians frequently object that water vapor, not CO 2 , is the most abundant and powerful greenhouse gas; they insist that climate scientists routinely leave it out of their models. The latter is simply untrue: from Arrhenius on, climatologists have incorporated water vapor into their models. In fact, water vapor is why rising CO 2 has such a big effect on climate. CO 2 absorbs some wavelengths of infrared that water does not, so it independently adds heat to the atmosphere. As the temperature rises, more water vapor enters the atmosphere and multiplies CO 2 ’s greenhouse effect; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that water vapor may “approximately double the increase in the greenhouse effect due to the added CO 2 alone.”

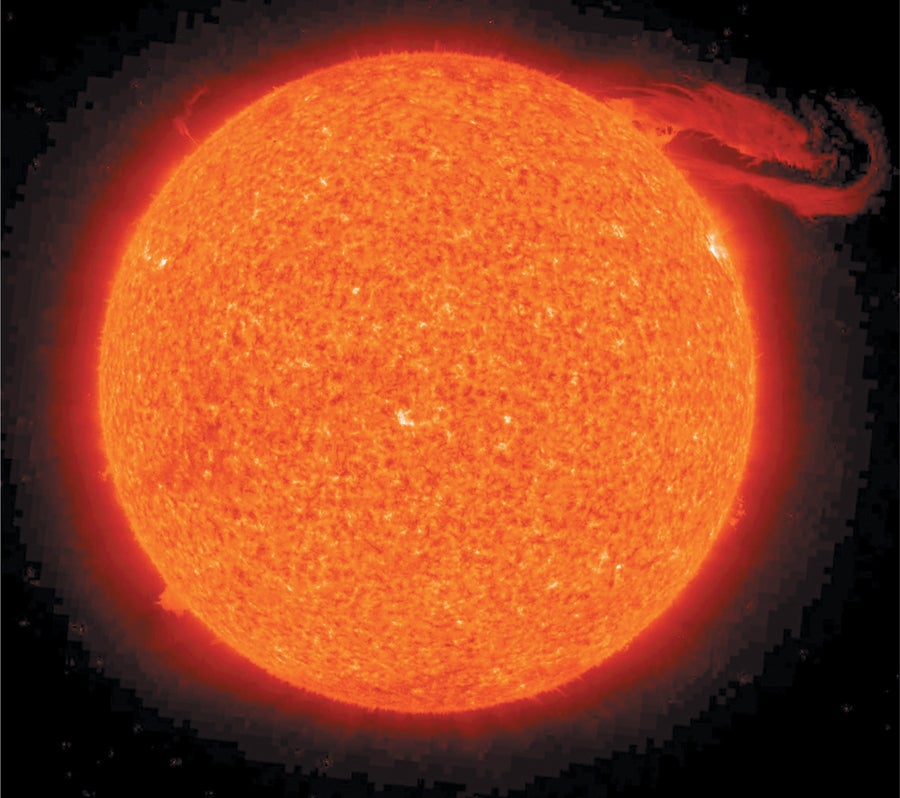

Climate contrarians argue that variation in solar energy reaching the planet is behind global warming. But human influence has a measurably stronger effect on climate. Credit: NASA

Nevertheless, within this dynamic, the CO 2 remains the main driver (what climatologists call a “forcing”) of the greenhouse effect. As NASA climatologist Gavin Schmidt has explained, water vapor enters and leaves the atmosphere much more quickly than CO 2 and tends to preserve a fairly constant level of relative humidity, which caps off its greenhouse effect. Climatologists therefore categorize water vapor as a feedback rather than a forcing factor. (Contrarians who don’t see water vapor in climate models are looking for it in the wrong place.)

Because of CO 2 ’s inescapable greenhouse effect, contrarians holding out for a natural explanation for current global warming need to explain why, in their scenarios, CO 2 is not compounding the problem.

CLAIM 2: The alleged “hockey stick” graph of temperatures over the past 1,600 years has been disproved. It doesn’t even acknowledge the existence of a “medieval warm period” around a.d. 1000 that was hotter than today is. Therefore, global warming is a myth.

It is hard to know which is greater: contrarians’ overstatement of the flaws in the historical temperature reconstruction from 1998 by Michael E. Mann and his colleagues or the ultimate insignificance of their argument to the case for climate change.

First, there is not simply one hockey-stick reconstruction of historical temperatures using one set of proxy data. Similar evidence for sharply increasing temperatures over the past couple of centuries has turned up independently while looking at ice cores, tree rings and other proxies for direct measurements, from many locations. Notwithstanding their differences, they corroborate that the planet has been getting sharply warmer.

A 2006 National Research Council review of the evidence concluded “with a high level of confidence that global mean surface temperature was higher during the last few decades of the 20th century than during any comparable period during the preceding four centuries”—which is the section of the graph most relevant to current climate trends. The report placed less faith in the reconstructions back to a.d. 900, although it still viewed them as “plausible.” Medieval warm periods in Europe and Asia with temperatures comparable to those seen in the 20th century were therefore similarly plausible but might have been local phenomena: the report noted “the magnitude and geographic extent of the warmth are uncertain.” And a research paper by Mann and his colleagues seems to confirm that the Medieval Warm Period and the “Little Ice Age” between 1400 and 1700 were both caused by shifts in solar radiance and other natural factors that do not seem to be happening today.

After the NRC review was released, another analysis by four statisticians, called the Wegman report, which was not formally peer-reviewed, was more critical of the hockey-stick paper. But correction of the errors it pointed out did not substantially change the shape of the hockey-stick graph. In 2008 Mann and his colleagues issued an updated version of the temperature reconstruction that echoed their earlier findings.

But hypothetically, even if the hockey stick was busted ... What of it? The case for anthropogenic global warming originally came from studies of climate mechanics, not from reconstructions of past temperatures seeking a cause. Warnings about current warming trends came out years before Mann’s hockey-stick graph. Even if the world were incontrovertibly warmer 1,000 years ago, it would not change the fact that the recent rapid rise in CO 2 explains the current episode of warming more credibly than any natural factor does—and that no natural factor seems poised to offset further warming in the years ahead.

CLAIM 3: Global warming stopped in 1998; Earth has been cooling since then.

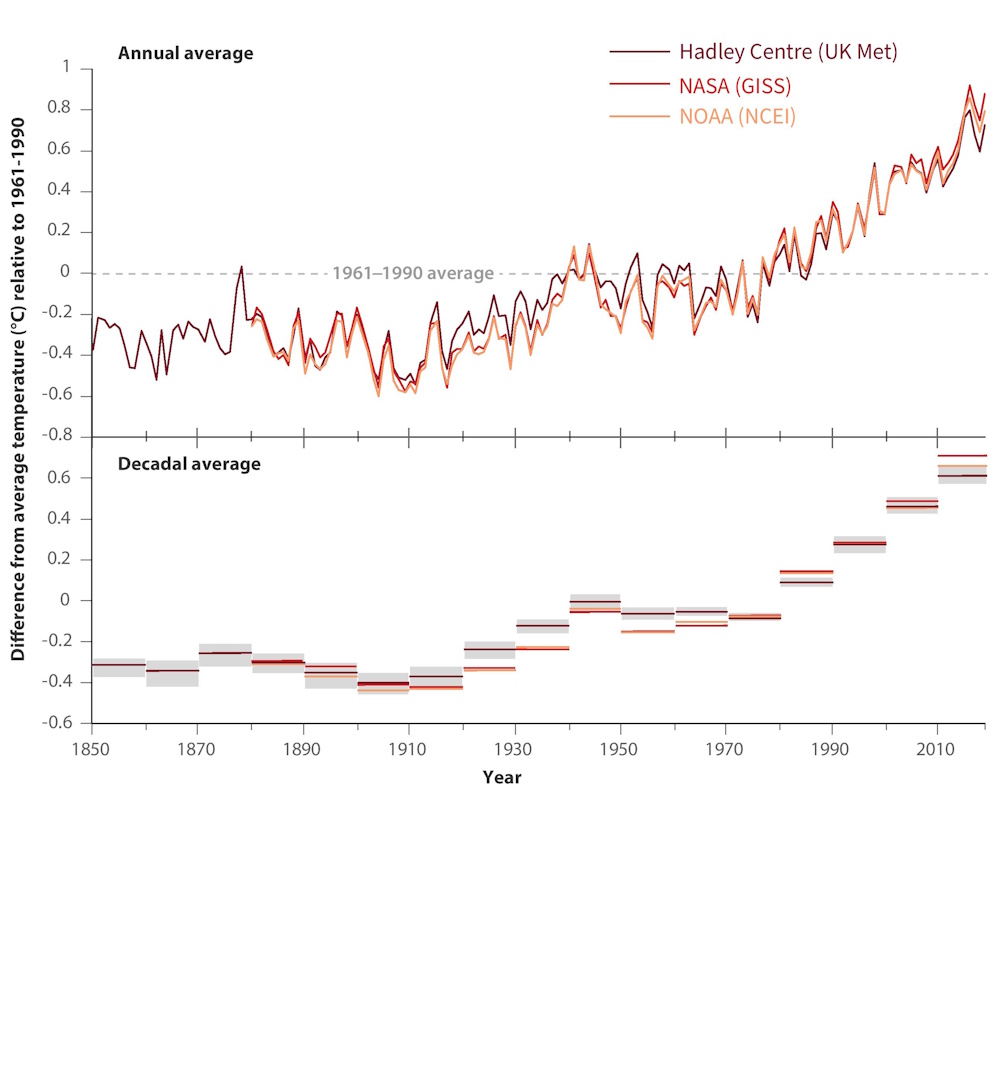

This contrarian argument might be the most obsolete and unintentionally hilarious. Here’s how it goes: 1998 was the world’s warmest year, according to the U.K. Met Office Hadley Center’s records; the following decade was cooler; therefore, the previous century’s global warming trend is over, right?

Anyone with even a glancing familiarity with statistics should be able to spot the weaknesses of that argument. Given the extended duration of the warming trend, the expected (and observed) variations in the rate of increase and the range of uncertainties in the temperature measurements and forecasts, a decade’s worth of mild interruption is too small a deviation to prove a break in the pattern, climatologists say.

If a lull in global warming had continued for another decade, would that have vindicated the contrarians’ case? Not necessarily, because climate is complex. For instance, Mojib Latif, then at the Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences in Germany, and his colleagues published a paper in 2008 that suggested ocean-circulation patterns might cause a period of cooling in parts of the Northern Hemisphere, even though the long-term pattern of warming remained in effect. Fundamentally, contrarians who have resisted the abundant evidence that supports warming should not be too quick to leap on evidence that only hints at the opposite.

In any case, the claim that a “warming pause” disproved ongoing climate change became completely academic when 1998 stopped being the warmest year on record. That title now belongs to 2016, with 2019 right behind it. In fact, the past 15 years have included all 10 of the hottest years on record.

CLAIM 4: The sun or cosmic rays are much more likely the real causes of global warming. After all, Mars is warming up, too.

Astronomical phenomena are obvious natural factors to consider when trying to understand climate, particularly the brightness of the sun and details of Earth’s orbit because those seem to have been major drivers of the ice ages and other climate changes before the rise of industrial civilization. Climatologists, therefore, do take them into account in their models. But in defiance of the naysayers who want to chalk the recent warming up to natural cycles, there is insufficient evidence that enough extra solar energy is reaching our planet to account for the observed rise in global temperatures.

The IPCC has noted that between 1750 and 2005, the radiative forcing from the sun increased by 0.12 watt per square meter—less than a tenth of the net forcings from human activities (1.6 W/ m 2 ). The largest uncertainty in that comparison comes from the estimated effects of aerosols in the atmosphere, which can variously shade Earth or warm it. Even granting the maximum uncertainties to these estimates, however, the increase in human influence on climate exceeds that of any solar variation.

Moreover, remember that the effect of CO 2 and the other greenhouse gases is to amplify the sun’s warming. Contrarians looking to pin global warming on the sun can’t simply point to any trend in solar radiance: they also need to quantify its effect and explain why CO 2 does not consequently become an even more powerful driver of climate change. (And is what weakens the greenhouse effect a necessary consequence of the rising solar influence or an ad hoc corollary added to give the desired result?)

Contrarians therefore gravitated toward work by Henrik Svensmark of the Technical University of Denmark, who argued that the sun’s influence on cosmic rays needed to be considered. Cosmic rays entering the atmosphere help to seed the formation of aerosols and clouds that reflect sunlight. In Svensmark’s theory, the high solar magnetic activity over the past 50 years shielded Earth from cosmic rays and allowed exceptional heating, but now that the sun is more magnetically quiet again, global warming would reverse. Svensmark claimed that, in his model, temperature changes correlate better with cosmic-ray levels and solar magnetic activity than with other greenhouse factors.

Svensmark’s theory failed to persuade most climatologists, however, because of weaknesses in its evidence. In particular, there do not seem to be clear long-term trends in the cosmic-ray influxes or in the clouds that they are supposed to form, and his model does not explain (as greenhouse explanations do) some of the observed patterns in how the world is getting warmer (such as that more of the warming occurs at night). For now, at least, cosmic rays remain a less plausible culprit in climate change.

And the apparent warming seen on Mars? Because it is based on a very small base of measurements, it may not represent a true trend. Too little is yet known about what governs the Martian climate to be sure, but a period when there was a darker surface might have increased the amount of absorbed sunlight and raised temperatures.

Elevated CO 2 makes oceans acidic, which could have irreversible harmful effects on coral reefs, such as coral bleaching ( shown here ). Credit: Getty Images

CLAIM 5: Climatologists conspire to hide the truth about global warming by locking away their data. Their so-called consensus on global warming is scientifically irrelevant because science isn’t settled by popularity.

It is virtually impossible to disprove accusations of giant global conspiracies to those already convinced of them (can anyone prove that the Freemasons and the Roswell aliens aren’t involved, too?). Let it therefore be noted that the magnitude of this hypothetical conspiracy would need to encompass many thousands of uncontroversial publications and respected scientists from around the world, stretching back through Arrhenius and Tyndall for almost 150 years. A conspiracy would have to be so powerful that it has co-opted the official positions of dozens of scientific organizations, including the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the U.K.’s Royal Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Geophysical Union, the American Institute of Physics and the American Meteorological Society.

If there were a massive conspiracy to defraud the world on climate (and to what end?), surely the thousands of e-mails and other files stolen from the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit in England and distributed by hackers in 2009 would bear proof of it. None did. Most of the few statements from those e-mails that critics claimed as evidence of malfeasance had more innocent explanations that make sense in the context of scientists conversing privately and informally. If any of the scientists involved manipulated data dishonestly or thwarted Freedom of Information requests, it would have been deplorable; however, there is no evidence that happened. What is missing is any clear indication of a widespread attempt to falsify and coordinate findings on a scale that could hold together a global cabal or significantly distort the record on climate change.

Climatologists are often frustrated by accusations that they are hiding data or the details of their models because, as NASA’s Schmidt points out, much of the relevant information is in public databases or otherwise accessible—a fact that contrarians conveniently ignore when insisting that scientists stonewall their requests. (And because nations differ in their rules on data confidentiality, scientists are not always at liberty to comply with some requests.) If contrarians want to deal a devastating blow to global warming theories, they should use the public data and develop their own credible models to demonstrate sound alternatives.

Yet that rarely occurs. In 2004 historian of science Naomi Oreskes published a landmark analysis of the peer-reviewed literature on global warming, “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change.” Out of 928 papers whose abstracts she surveyed, she wrote, 75 percent explicitly or implicitly supported anthropogenic global warming, 25 percent were methodological or otherwise took no position on the subject—and none argued for purely natural explanations. Notwithstanding some attempts to debunk Oreskes’s findings that eventually fell apart, her conclusion stands.

Oreskes’s work does not mean that all climate scientists agree about climate change—obviously, some do not (although they are very much a minority). Rather the meaningful consensus is not among the scientists but within the science: the overwhelming predominance of evidence for greenhouse-driven global warming that cannot easily be overturned even by a few contrary studies. (Oreskes currently is a columnist for Scientific American .)

CLAIM 6: Climatologists have a vested interest in raising the alarm because it brings them money and prestige.

If climate scientists are angling for more money by hyping fears of climate change, they are not doing so very effectively. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, between 1993 and 2014 federal spending on climate change research, technology, international assistance and adaptation rose from $2.4 billion to $11.6 billion. (An additional $26.1 billion was also allocated to climate change programs and activities by the economic stimulus package of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009. Total federal nondefense spending on research in 2014 exceeded $65 billion.) Yet the scientific research share of that money fell sharply throughout that period: most of the budgeted money went to energy-conservation projects and other technology programs. Climatologists’ funding therefore stayed almost flat, whereas others, including those in industry, benefited handsomely. Surely the Freemasons could do better than that.

CLAIM 7: Technological fixes, such as inventing energy sources that don’t produce CO 2 or geoengineering the climate, would be more affordable, prudent ways to address climate change than reducing our carbon footprint.

Critics of standard policy responses to climate change have often seemed to imply that environmentalists are obsessed with regulatory reductions in CO 2 emissions and uninterested in technological solutions. That interpretation is at best bizarre: such innovations in energy efficiency, conservation and production are exactly what caps or levies on CO 2 are meant to encourage.

The relevant question is whether it is prudent for civilization to defer curbing or reducing its CO 2 output before such technologies are ready and can be deployed at the needed scale. The most common conclusion is no. Remember that as long as CO 2 levels are elevated, additional heat will be pumped into the atmosphere and oceans, extending and worsening the climate consequences. As climatologist James Hansen of the Earth Institute at Columbia University has pointed out, even if current CO 2 levels could be stabilized overnight, surface temperatures would continue to rise by 0.5 degree C over the next few decades because of absorbed heat being released from the ocean. The longer we wait for technology alone to reduce CO 2 , the faster we will need for those solutions to pull CO 2 out of the air to minimize the warming problems. Minimizing the scope of the challenge by restricting the accumulation of CO 2 only makes sense.

Moreover, climate change is not the only environmental crisis posed by elevated CO 2 : it also makes the oceans acidic, which could have irreversibly harmful effects on coral reefs and other marine life. Only the immediate mitigation of CO 2 release can contain those losses.

Much has already been written on why schemes for geoengineering—altering Earth’s climate systems by design—seem ill advised except as a desperate last-chance strategy for dealing with climate change. The more ambitious proposals involve largely untested technologies, so it is unclear how well they would achieve their desired purpose; even if they did curb warming, they might cause other significant environmental problems in the process. Methods that did not remove CO 2 from the air would have to be maintained in perpetuity to prevent drastic rebound warming. And the governance of the geoengineering system could become a political minefield, with nations disagreeing about what the optimal climate settings should be. And of course, as with any of the other technological solutions, reducing the emission and accumulation of CO 2 in the atmosphere first would only make any geoengineering solution easier.

All in all, counting on future technological developments to solve climate change rather than engaging with the problem straightforwardly by all available means, including regulatory ones, seems like the height of irresponsibility. But then again, responsible action on climate change is what the contrarians seem most interested in denying.

John Rennie is a former editor in chief of Scientific American .

- News, Stories & Speeches

- Get Involved

- Structure and leadership

- Committee of Permanent Representatives

- UN Environment Assembly

- Funding and partnerships

- Policies and strategies

- Evaluation Office

- Secretariats and Conventions

- Asia and the Pacific

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- New York Office

- North America

- Climate action

- Nature action

- Chemicals and pollution action

- Digital Transformations

- Disasters and conflicts

- Environment under review

- Environmental law and governance

- Extractives

- Fresh Water

- Green economy

- Ocean, seas and coasts

- Resource efficiency

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Youth, education and environment

- Publications & data

Debunking eight common myths about climate change

The world is warming at a record pace , with unseasonable heat baking nearly every continent on Earth. April, the last month for which statistics are available, marked the 11th consecutive month the planet has set a new temperature high.

Experts say that is a clear sign the Earth’s climate is rapidly changing. But many believe – or at least say they believe – that climate change is not real, relying on a series of well-trodden myths to make their point.

“Most of the world rightly acknowledges that climate change is real,” says Dechen Tsering, Acting Director of the Climate Change Division at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). “But in many places, misinformation is delaying the action that is so vital to countering what is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity.”

This month, delegates will be meeting in Bonn, Germany for a key conference on climate change. Ahead of that gathering, here is a closer look at eight common climate-related myths and why they are simply not true.

Myth #1: Climate change has always happened, so we should not worry about it.

It is true that the planet’s temperature has long fluctuated, with periods of warming and cooling. But since the last ice age 10,000 years ago, the climate has been relatively stable, which scientists say has been crucial to the development of human civilization.

That stability is now faltering. The Earth is heating up at its fastest rate in at least 2,000 years and is about 1.2°C hotter than it was in pre-industrial times. The last 10 years have been the warmest on record, with 2023 smashing global temperature records.

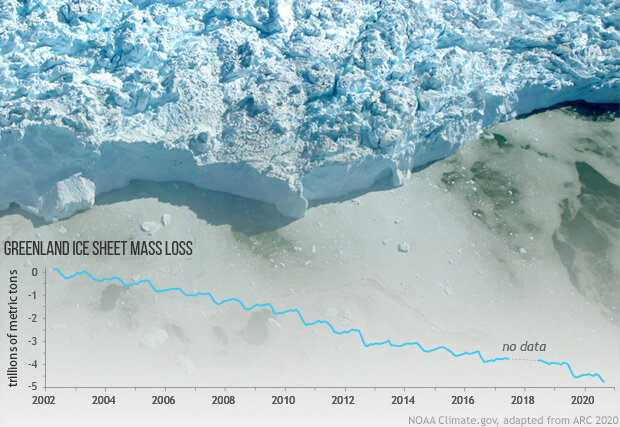

Other key climate-related indicators are also spiking. Ocean temperatures , sea levels and atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses are rising at record rates while sea ice and glaciers are retreating at alarming speeds.

Myth #2: Climate change is a natural process. It has nothing to do with people.

While climate change is a natural process human activity is pushing it into overdrive. A landmark report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which draws on the research of hundreds of leading climate scientists, found that humans are responsible for almost all the global warming over the past 200 years.

The vast majority of warming has come from the burning of coal, oil and gas. The combustion of these fossil fuels is flooding the atmosphere with greenhouse gases, which act like a blanket around the planet, trapping heat.

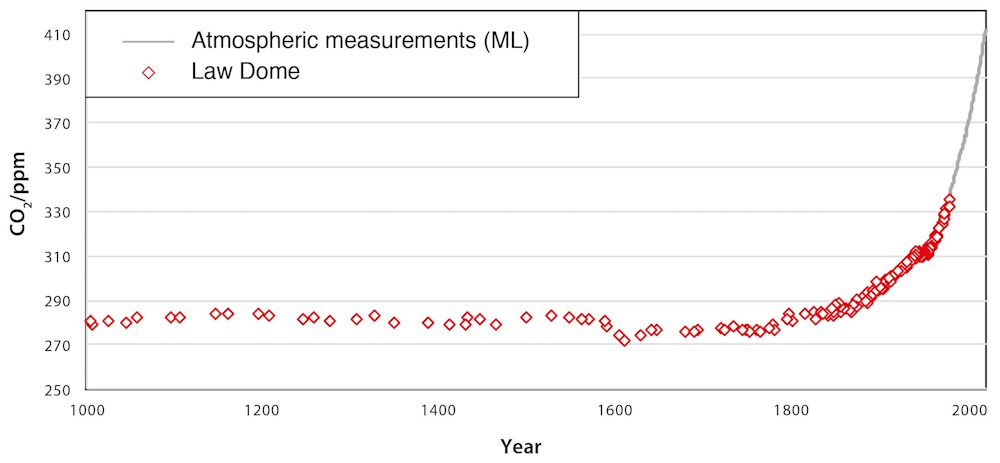

By measuring everything from ice cores to tree rings, scientists have been able to track concentrations of greenhouse gases. Carbon dioxide levels are at their highest in 2 million years , while two other greenhouse gases, methane and nitrous oxide, are at their highest in 800,000 years .

Myth #3: A couple of degrees of warming is not that big of a deal.

Actually, small temperature rises can throw the world’s delicate ecosystems into disarray, with dire implications for humans and other living things. The Paris Agreement on climate change aims to limit average global temperature rise to “well below” 2°C, and preferably to 1.5°C, since pre-industrial times.

Even that half-a-degree swing could make a massive difference. The IPCC found that at 2°C of warming, more than 2 billion people would regularly be exposed to extreme heat than they would at 1.5°C. The world would also lose twice as many plants and vertebrate species and three times as many insects. In some areas, crop yields would decrease by more than half, threatening food security.

At 1.5°C of warming, 70 per cent to 90 per cent of corals, the pillars of many undersea ecosystems, would die. At 2°C of warming, some 99 per cent would perish. Their disappearance would likely lead to the loss of other marine species, many of which are a critical source of protein for coastal communities.

“Every fraction of a degree of warming matters,” says Tsering.

Myth #4: An increase in cold snaps shows climate change is not real.

This statement confuses weather and climate, which are two different things. Weather is the day-to-day atmospheric conditions in a location and climate is the long-term weather conditions in a region. So, there could still be a cold snap while the general trend for the planet is warming.

Some experts also believe climate change could lead to longer and more intense cold in some places due to changes in wind patterns and other atmospheric factors. One much-publicized paper found the rapid warming of the Arctic may have disrupted the swirling mass of cold air above the North Pole in 2021. This unleashed sub-zero temperatures as far south as Texas in the United States, causing billions of dollars in damages.

Myth #5: Scientists disagree on the cause of climate change.

A 2021 study revealed that 99 per cent of peer-reviewed scientific literature found that climate change was human-induced. That was in line with a widely read study from 2013 , which found 97 per cent of peer-reviewed papers that examined the causes of climate change said it was human-caused.

“The idea that there is no consensus is used by climate deniers to muddy the waters and sow the seeds of doubt,” says Tsering. “But the scientific community agrees: the global warming we are facing is not natural. It is caused by humans.”

Myth #6: It is too late to avert a climate catastrophe, so we might as well keep burning fossil fuels.

While the situation is dire, there is still a narrow window for humanity to avoid the worst of climate change.

UNEP’s latest Emissions Gap Report found that cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 42 per cent by 2030, the world could limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C compared with pre-industrial levels.

A little math reveals that to reach that target, the world must reduce its annual emissions by 22 billion tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent in less than seven years. That might seem like a lot. But by ramping up financing and focusing on low-carbon development in key transport , agriculture and forestry, the world can get there.

“There is no question the task ahead of us is massive,” Tsering says. “But we have the solutions we need to reduce emissions today and there is an opportunity to raise ambition in the new round of national climate action plans.”

Myth #7: Climate models are unreliable.

Climate skeptics have long argued that the computer models used to project climate change are unreliable at best and completely inaccurate at worst.

But the IPCC, the world’s leading scientific authority on climate change, says that over decades of development, these models have consistently provided “a robust and unambiguous picture” of planetary warming.

Meanwhile, a 2020 study by the University of California showed that global warming models were largely accurate. The study looked at 17 models that were generated between 1970 and 2007 and found 14 of them closely matched observations.

Myth #8: We do not need to worry about lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Humanity is inventive; we can just adapt to climate change.

Some countries and communities can adapt to rising temperatures, lower precipitation and the other impacts of climate change. But many cannot.

The world’s developing countries collectively need between US$215 billion and US$387 billion per year to adapt to climate change, yet only have access to a fraction of that total, found UNEP’s latest Adaptation Gap Report . Even wealthy nations will struggle to afford the cost of adaptation, which in some cases will require radical measures, such as displacing vulnerable communities, relocating vital infrastructure or changing staple foods.

In many places, people are already facing hard limits on how much they can adapt. Small island developing states , for example, can only do so much to hold back the rising seas that threaten their existence.

Without significant action to lower greenhouse gas emissions, communities will reach these hard limits faster and begin to suffer irreparable damage from climate change, say experts.

The Sectoral Solution to the climate crisis

UNEP is at the forefront of supporting the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global temperature rise well below 2°C, and aiming for 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. To do this, UNEP has developed the Sectoral Solution, a roadmap to reducing emissions across sectors in line with the Paris Agreement commitments and in pursuit of climate stability. The six sectors identified are: energy; industry; agriculture and food; forests and land use; transport; and buildings and cities.

Further Resources

- UNEP’s work on climate change

- The Sectoral Solution to Climate Change

- Adaptation Gap Report 2023

- Emissions Gap Report 2023

Related Content

Related Sustainable Development Goals

© 2024 UNEP Terms of Use Privacy Report Project Concern Report Scam Contact Us

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

How did we get here the roots and impacts of the climate crisis.

People’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels and the cutting down of carbon-storing forests have transformed global climate.

For more than a century, researchers have honed their methods for measuring the impacts of human actions on Earth's atmosphere.

Sam Falconer

Share this:

By Alexandra Witze

March 10, 2022 at 11:00 am

Even in a world increasingly battered by weather extremes, the summer 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest stood out. For several days in late June, cities such as Vancouver, Portland and Seattle baked in record temperatures that killed hundreds of people. On June 29, Lytton, a village in British Columbia, set an all-time heat record for Canada, at 121° Fahrenheit (49.6° Celsius); the next day, the village was incinerated by a wildfire.

Within a week, an international group of scientists had analyzed this extreme heat and concluded it would have been virtually impossible without climate change caused by humans. The planet’s average surface temperature has risen by at least 1.1 degrees Celsius since preindustrial levels of 1850–1900. The reason: People are loading the atmosphere with heat-trapping gases produced during the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal and gas, and from cutting down forests.

To celebrate our 100th anniversary, we’re highlighting some of the biggest advances in science over the last century. To see more from the series, visit Century of Science .

A little over 1 degree of warming may not sound like a lot. But it has already been enough to fundamentally transform how energy flows around the planet. The pace of change is accelerating, and the consequences are everywhere. Ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting, raising sea levels and flooding low-lying island nations and coastal cities. Drought is parching farmlands and the rivers that feed them. Wildfires are raging. Rains are becoming more intense, and weather patterns are shifting .

The roots of understanding this climate emergency trace back more than a century and a half. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that scientists began the detailed measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide that would prove how much carbon is pouring from human activities. Beginning in the 1960s, researchers started developing comprehensive computer models that now illuminate the severity of the changes ahead.

Today we know that climate change and its consequences are real, and we are responsible. The emissions that people have been putting into the air for centuries — the emissions that made long-distance travel, economic growth and our material lives possible — have put us squarely on a warming trajectory . Only drastic cuts in carbon emissions, backed by collective global will, can make a significant difference.

“What’s happening to the planet is not routine,” says Ralph Keeling, a geochemist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. “We’re in a planetary crisis.”

Setting the stage

One day in the 1850s, Eunice Newton Foote, an amateur scientist and a women’s rights activist living in upstate New York, put two glass jars in sunlight. One contained regular air — a mix of nitrogen, oxygen and other gases including carbon dioxide — while the other contained just carbon dioxide. Both had thermometers in them. As the sun’s rays beat down, Foote observed that the jar of CO 2 alone heated up more quickly, and was slower to cool down, than the one containing plain air.

The results prompted Foote to muse on the relationship between CO 2 , the planet and heat. “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature,” she wrote in an 1856 paper summarizing her findings .

Three years later, working independently and apparently unaware of Foote’s discovery, Irish physicist John Tyndall showed the same basic idea in more detail. With a set of pipes and devices to study the transmission of heat, he found that CO 2 gas, as well as water vapor, absorbed more heat than air alone. He argued that such gases would trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, much as panes of glass trap heat in a greenhouse, and thus modulate climate.

Today Tyndall is widely credited with the discovery of how what we now call greenhouse gases heat the planet, earning him a prominent place in the history of climate science. Foote faded into relative obscurity — partly because of her gender, partly because her measurements were less sensitive. Yet their findings helped kick off broader scientific exploration of how the composition of gases in Earth’s atmosphere affects global temperatures.

Heat-trapping gases

In 1859, John Tyndall used this apparatus to study how various gases trap heat. He sent infrared radiation through a tube filled with gas and measured the resulting temperature changes. Carbon dioxide and water vapor, he showed, absorb more heat than air does.

Carbon floods in

Humans began substantially affecting the atmosphere around the turn of the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution took off in Britain. Factories burned tons of coal; fueled by fossil fuels, the steam engine revolutionized transportation and other industries. Since then, fossil fuels including oil and natural gas have been harnessed to drive a global economy. All these activities belch gases into the air.

Yet Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius wasn’t worried about the Industrial Revolution when he began thinking in the late 1800s about changes in atmospheric CO 2 levels. He was instead curious about ice ages — including whether a decrease in volcanic eruptions, which can put carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, would lead to a future ice age. Bored and lonely in the wake of a divorce, Arrhenius set himself to months of laborious calculations involving moisture and heat transport in the atmosphere at different zones of latitude. In 1896, he reported that halving the amount of CO 2 in the atmosphere could indeed bring about an ice age — and that doubling CO 2 would raise global temperatures by around 5 to 6 degrees C.

It was a remarkably prescient finding for work that, out of necessity, had simplified Earth’s complex climate system down to just a few variables. But Arrhenius’ findings didn’t gain much traction with other scientists at the time. The climate system seemed too large, complex and inert to change in any meaningful way on a timescale that would be relevant to human society. Geologic evidence showed, for instance, that ice ages took thousands of years to start and end. What was there to worry about?

Extreme Climate Survey

Science News is collecting reader questions about how to navigate our planet's changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

One researcher, though, thought the idea was worth pursuing. Guy Stewart Callendar, a British engineer and amateur meteorologist, had tallied weather records over time, obsessively enough to determine that average temperatures were increasing at 147 weather stations around the globe. In a 1938 paper in a Royal Meteorological Society journal, he linked this temperature rise to the burning of fossil fuels . Callendar estimated that fossil fuel burning had put around 150 billion metric tons of CO 2 into the atmosphere since the late 19th century.

Like many of his day, Callendar didn’t see global warming as a problem. Extra CO 2 would surely stimulate plants to grow and allow crops to be farmed in new regions. “In any case the return of the deadly glaciers should be delayed indefinitely,” he wrote. But his work revived discussions tracing back to Tyndall and Arrhenius about how the planetary system responds to changing levels of gases in the atmosphere. And it began steering the conversation toward how human activities might drive those changes.

When World War II broke out the following year, the global conflict redrew the landscape for scientific research. Hugely important wartime technologies, such as radar and the atomic bomb, set the stage for “big science” studies that brought nations together to tackle high-stakes questions of global reach. And that allowed modern climate science to emerge.

The Keeling curve

One major effort was the International Geophysical Year, or IGY, an 18-month push in 1957–1958 that involved a wide array of scientific field campaigns including exploration in the Arctic and Antarctica. Climate change wasn’t a high research priority during the IGY, but some scientists in California, led by Roger Revelle of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, used the funding influx to begin a project they’d long wanted to do. The goal was to measure CO 2 levels at different locations around the world, accurately and consistently.

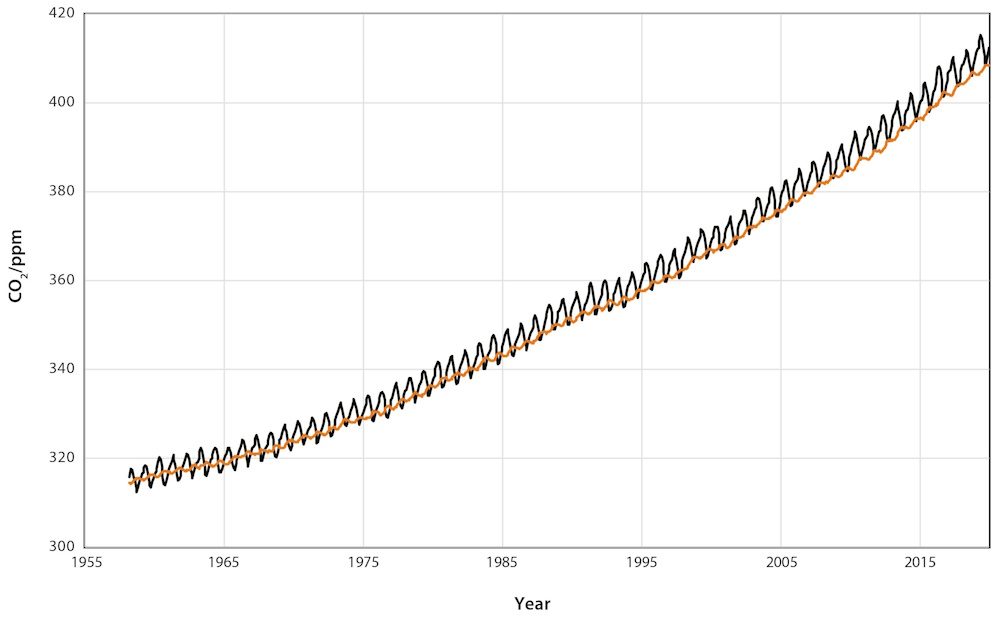

The job fell to geochemist Charles David Keeling, who put ultraprecise CO 2 monitors in Antarctica and on the Hawaiian volcano of Mauna Loa. Funds soon ran out to maintain the Antarctic record, but the Mauna Loa measurements continued. Thus was born one of the most iconic datasets in all of science — the “Keeling curve,” which tracks the rise of atmospheric CO 2 .

When Keeling began his measurements in 1958, CO 2 made up 315 parts per million of the global atmosphere. Within just a few years it became clear that the number was increasing year by year. Because plants take up CO 2 as they grow in spring and summer and release it as they decompose in fall and winter, CO 2 concentrations rose and fell each year in a sawtooth pattern. But superimposed on that pattern was a steady march upward.

“The graph got flashed all over the place — it was just such a striking image,” says Ralph Keeling, who is Keeling’s son. Over the years, as the curve marched higher, “it had a really important role historically in waking people up to the problem of climate change.” The Keeling curve has been featured in countless earth science textbooks, congressional hearings and in Al Gore’s 2006 documentary on climate change, An Inconvenient Truth .

Each year the curve keeps going up: In 2016, it passed 400 ppm of CO 2 in the atmosphere as measured during its typical annual minimum in September. Today it is at 413 ppm. (Before the Industrial Revolution, CO 2 levels in the atmosphere had been stable for centuries at around 280 ppm.)

Around the time that Keeling’s measurements were kicking off, Revelle also helped develop an important argument that the CO 2 from human activities was building up in Earth’s atmosphere. In 1957, he and Hans Suess, also at Scripps at the time, published a paper that traced the flow of radioactive carbon through the oceans and the atmosphere . They showed that the oceans were not capable of taking up as much CO 2 as previously thought; the implication was that much of the gas must be going into the atmosphere instead.

Steady rise

Known as the Keeling curve, this chart shows the rise in CO 2 levels as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii due to human activities. The visible sawtooth pattern is due to seasonal plant growth: Plants take up CO 2 in the growing seasons, then release it as they decompose in fall and winter.

Monthly average CO 2 concentrations at Mauna Loa Observatory

“Human beings are now carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment of a kind that could not have happened in the past nor be reproduced in the future,” Revelle and Suess wrote in the paper. It’s one of the most famous sentences in earth science history.

Here was the insight underlying modern climate science: Atmospheric carbon dioxide is increasing, and humans are causing the buildup. Revelle and Suess became the final piece in a puzzle dating back to Svante Arrhenius and John Tyndall. “I tell my students that to understand the basics of climate change, you need to have the cutting-edge science of the 1860s, the cutting-edge math of the 1890s and the cutting-edge chemistry of the 1950s,” says Joshua Howe, an environmental historian at Reed College in Portland, Ore.

Evidence piles up

Observational data collected throughout the second half of the 20th century helped researchers gradually build their understanding of how human activities were transforming the planet.

Ice cores pulled from ice sheets, such as that atop Greenland, offer some of the most telling insights for understanding past climate change. Each year, snow falls atop the ice and compresses into a fresh layer of ice representing climate conditions at the time it formed. The abundance of certain forms, or isotopes, of oxygen and hydrogen in the ice allows scientists to calculate the temperature at which it formed, and air bubbles trapped within the ice reveal how much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases were in the atmosphere at that time. So drilling down into an ice sheet is like reading the pages of a history book that go back in time the deeper you go.

Scientists began reading these pages in the early 1960s, using ice cores drilled at a U.S. military base in northwest Greenland . Contrary to expectations that past climates were stable, the cores hinted that abrupt climate shifts had happened over the last 100,000 years. By 1979, an international group of researchers was pulling another deep ice core from a second location in Greenland — and it, too, showed that abrupt climate change had occurred in the past. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a pair of European- and U.S.-led drilling projects retrieved even deeper cores from near the top of the ice sheet, pushing the record of past temperatures back a quarter of a million years.

Together with other sources of information, such as sediment cores drilled from the seafloor and molecules preserved in ancient rocks, the ice cores allowed scientists to reconstruct past temperature changes in extraordinary detail. Many of those changes happened alarmingly fast. For instance, the climate in Greenland warmed abruptly more than 20 times in the last 80,000 years , with the changes occurring in a matter of decades. More recently, a cold spell that set in around 13,000 years ago suddenly came to an end around 11,500 years ago — and temperatures in Greenland rose 10 degrees C in a decade.

Evidence for such dramatic climate shifts laid to rest any lingering ideas that global climate change would be slow and unlikely to occur on a timescale that humans should worry about. “It’s an important reminder of how ‘tippy’ things can be,” says Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

More evidence of global change came from Earth-observing satellites, which brought a new planet-wide perspective on global warming beginning in the 1960s. From their viewpoint in the sky, satellites have measured the rise in global sea level — currently 3.4 millimeters per year and accelerating, as warming water expands and as ice sheets melt — as well as the rapid decline in ice left floating on the Arctic Ocean each summer at the end of the melt season. Gravity-sensing satellites have “weighed” the Antarctic and Greenlandic ice sheets from above since 2002, reporting that more than 400 billion metric tons of ice are lost each year.

Temperature observations taken at weather stations around the world also confirm that we are living in the hottest years on record. The 10 warmest years since record keeping began in 1880 have all occurred since 2005 . And nine of those 10 have come since 2010.

Worrisome predictions

By the 1960s, there was no denying that the planet was warming. But understanding the consequences of those changes — including the threat to human health and well-being — would require more than observational data. Looking to the future depended on computer simulations: complex calculations of how energy flows through the planetary system.

A first step in building such climate models was to connect everyday observations of weather to the concept of forecasting future climate. During World War I, British mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson imagined tens of thousands of meteorologists, each calculating conditions for a small part of the atmosphere but collectively piecing together a global forecast.

But it wasn’t until after World War II that computational power turned Richardson’s dream into reality. In the wake of the Allied victory, which relied on accurate weather forecasts for everything from planning D-Day to figuring out when and where to drop the atomic bombs, leading U.S. mathematicians acquired funding from the federal government to improve predictions. In 1950, a team led by Jule Charney, a meteorologist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., used the ENIAC, the first U.S. programmable, electronic computer, to produce the first computer-driven regional weather forecast . The forecasting was slow and rudimentary, but it built on Richardson’s ideas of dividing the atmosphere into squares, or cells, and computing the weather for each of those. The work set the stage for decades of climate modeling to follow.

By 1956, Norman Phillips, a member of Charney’s team, had produced the world’s first general circulation model, which captured how energy flows between the oceans, atmosphere and land. The field of climate modeling was born.

The work was basic at first because early computers simply didn’t have much computational power to simulate all aspects of the planetary system.

An important breakthrough came in 1967, when meteorologists Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald — both at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, a lab born from Charney’s group — published a paper in the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences that modeled connections between Earth’s surface and atmosphere and calculated how changes in CO 2 would affect the planet’s temperature. Manabe and Wetherald were the first to build a computer model that captured the relevant processes that drive climate , and to accurately simulate how the Earth responds to those processes.

The rise of climate modeling allowed scientists to more accurately envision the impacts of global warming. In 1979, Charney and other experts met in Woods Hole, Mass., to try to put together a scientific consensus on what increasing levels of CO 2 would mean for the planet. The resulting “Charney report” concluded that rising CO 2 in the atmosphere would lead to additional and significant climate change.

In the decades since, climate modeling has gotten increasingly sophisticated . And as climate science firmed up, climate change became a political issue.

The hockey stick

This famous graph, produced by scientist Michael Mann and colleagues, and then reproduced in a 2001 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, dramatically captures temperature change over time. Climate change skeptics made it the center of an all-out attack on climate science.

The rising public awareness of climate change, and battles over what to do about it, emerged alongside awareness of other environmental issues in the 1960s and ’70s. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring , which condemned the pesticide DDT for its ecological impacts, catalyzed environmental activism in the United States and led to the first Earth Day in 1970.

In 1974, scientists discovered another major global environmental threat — the Antarctic ozone hole, which had some important parallels to and differences from the climate change story. Chemists Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland, of the University of California, Irvine, reported that chlorofluorocarbon chemicals, used in products such as spray cans and refrigerants, caused a chain of reactions that gnawed away at the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer . The resulting ozone hole, which forms over Antarctica every spring, allows more ultraviolet radiation from the sun to make it through Earth’s atmosphere and reach the surface, where it can cause skin cancer and eye damage.

Governments worked under the auspices of the United Nations to craft the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which strictly limited the manufacture of chlorofluorocarbons . In the years following, the ozone hole began to heal. But fighting climate change is proving to be far more challenging. Transforming entire energy sectors to reduce or eliminate carbon emissions is much more difficult than replacing a set of industrial chemicals.

In 1980, though, researchers took an important step toward banding together to synthesize the scientific understanding of climate change and bring it to the attention of international policy makers. It started at a small scientific conference in Villach, Austria, on the seriousness of climate change. On the train ride home from the meeting, Swedish meteorologist Bert Bolin talked with other participants about how a broader, deeper and more international analysis was needed. In 1988, a United Nations body called the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, was born. Bolin was its first chairperson.

The IPCC became a highly influential and unique body. It performs no original scientific research; instead, it synthesizes and summarizes the vast literature of climate science for policy makers to consider — primarily through massive reports issued every couple of years. The first IPCC report, in 1990 , predicted that the planet’s global mean temperature would rise more quickly in the following century than at any point in the last 10,000 years, due to increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

IPCC reports have played a key role in providing scientific information for nations discussing how to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations. This process started with the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 , which resulted in the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Annual U.N. meetings to tackle climate change led to the first international commitments to reduce emissions, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 . Under it, developed countries committed to reduce emissions of CO 2 and other greenhouse gases. By 2007, the IPCC declared the reality of climate warming is “unequivocal.” The group received the Nobel Peace Prize that year, along with Al Gore, for their work on climate change.

The IPCC process ensured that policy makers had the best science at hand when they came to the table to discuss cutting emissions. Of course, nations did not have to abide by that science — and they often didn’t. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, international climate meetings discussed less hard-core science and more issues of equity. Countries such as China and India pointed out that they needed energy to develop their economies and that nations responsible for the bulk of emissions through history, such as the United States, needed to lead the way in cutting greenhouse gases.

Meanwhile, residents of some of the most vulnerable nations, such as low-lying islands that are threatened by sea level rise, gained visibility and clout at international negotiating forums. “The issues around equity have always been very uniquely challenging in this collective action problem,” says Rachel Cleetus, a climate policy expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists in Cambridge, Mass.