800.747.4457

Mon-Thurs 7am - 5pm CST

Get in touch with our team

Frequently asked questions

- Fitness & Health

- Sport & Exercise Science

- Physical Education

- Strength & Conditioning

- Sports Medicine

- Sport Management

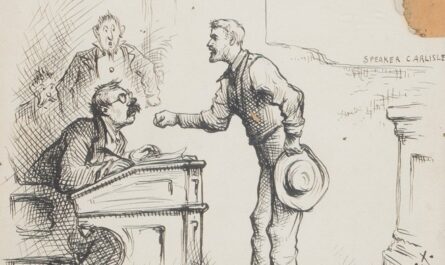

Definitions of leisure, play, and recreation

This is an excerpt from park and recreation professional's handbook with online resource, the by amy hurd & denise anderson..

Defining leisure, play, and recreation provides us as leisure professionals with a strong foundation for the programs, services, and facilities that we provide. While we might disagree on the standard definition of leisure, play, or recreation, we are all concerned with providing an experience for participants. Whether we work in the public, private nonprofit, or commercial sector, all three concepts are driving forces behind the experiences we provide. Table 1.1 outlines the basic definitions of leisure, play, and recreation.

Definitions of Leisure

There is debate about how to define leisure. However, there is a general consensus that there are three primary ways in which to consider leisure: leisure as time, leisure as activity, and leisure as state of mind.

Leisure as Time

By this definition leisure is time free from obligations, work (paid and unpaid), and tasks required for existing (sleeping, eating). Leisure time is residual time. Some people argue it is the constructive use of free time. While many may view free time as all nonworking hours, only a small amount of time spent away from work is actually free from other obligations that are necessary for existence, such as sleeping and eating.

Leisure as Activity

Leisure can also be viewed as activities that people engage in during their free time—activities that are not work oriented or that do not involve life maintenance tasks such as housecleaning or sleeping. Leisure as activity encompasses the activities that we engage in for reasons as varied as relaxation, competition, or growth and may include reading for pleasure, meditating, painting, and participating in sports. This definition gives no heed to how a person feels while doing the activity; it simply states that certain activities qualify as leisure because they take place during time away from work and are not engaged in for existence. However, as has been argued by many, it is extremely difficult to come up with a list of activities that everyone agrees represents leisure—to some an activity might be a leisure activity and to others it might not necessarily be a leisure activity. Therefore, with this definition the line between work and leisure is not clear in that what is leisure to some may be work to others and vice versa.

Leisure as State of Mind

Unlike the definitions of leisure as time or activity, the definition of leisure as state of mind is much more subjective in that it considers the individual's perception of an activity. Concepts such as perceived freedom, intrinsic motivation, perceived competence, and positive affect are critical to determining whether an experience is leisure or not leisure.

Perceived freedom refers to an individual's ability to choose the activity or experience in that the individual is free from other obligations as well as has the freedom to act without control from others. Perceived freedom also involves the absence of external constraints to participation.

The second requirement of leisure as state of mind, intrinsic motivation, means that the person is moved from within to participate. The person is not influenced by external factors (e.g., people or reward) and the experience results in personal feelings of satisfaction, enjoyment, and gratification.

Perceived competence is also critical to leisure defined as state of mind. Perceived competence refers to the skills people believe they possess and whether their skill levels are in line with the degree of challenge inherent in an experience. Perceived competence relates strongly to satisfaction, and for successful participation to occur, the skill-to-challenge ratio must be appropriate.

Positive affect, the final key component of leisure as state of mind, refers to a person's sense of choice, or the feeling people have when they have some control over the process that is tied to the experience. Positive affect refers to enjoyment, and this enjoyment comes from a sense of choice.

What may be a leisure experience for one person may not be for another; whether an experience is leisure depends on many factors. Enjoyment, motivation, and choice are three of the most important of these factors. Therefore, when different individuals engage in the same activity, their state of mind can differ drastically.

Definition of Play

Unlike leisure, play has a more singular definition. Play is imaginative, intrinsically motivated, nonserious, freely chosen, and actively engaging. While most people see play as the domain of children, adults also play, although often their play is more entwined with rules and regulations, which calls into question how playful their play really is. On the other hand, children's play is typified by spontaneity, joyfulness, and inhibition and is done not as a means to an end but for its inherent pleasure.

Definition of Recreation

There is some consensus on the definition of recreation. Recreation is an activity that people engage in during their free time, that people enjoy, and that people recognize as having socially redeeming values. Unlike leisure, recreation has a connotation of being morally acceptable not just to the individual but also to society as a whole, and thus we program for those activities within that context. While recreation activities can take many forms, they must contribute to society in a way that society deems acceptable. This means that activities deemed socially acceptable for recreation can change over time.

Examples of recreational activities are endless and include sports, music, games, travel, reading, arts and crafts, and dance. The specific activity performed is less important than the reason for performing the activity, which is the outcome. For most the overarching desired outcome is recreation or restoration. Participants hope that their recreation pursuits can help them to balance their lives and refresh themselves from their work as well as other mandated activities such as housecleaning, child rearing, and so on.

People also see recreation as a social instrument because of its contribution to society. That is, professionals have long used recreation programs and services to produce socially desirable outcomes, such as the wise use of free time, physical fitness, and positive youth development. The organized development of recreation programs to meet a variety of physical, psychological, and social needs has led to recreation playing a role as a social instrument for well-being and, in some cases, change. This role has been the impetus for the development of many recreation providers from municipalities to nonprofits such as the YMCA, YWCA, Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts of the USA, and the Boys and Girls Clubs of America. There are also for-profit agencies, such as fitness centers and spas, designed to provide positive outcomes.

Latest Posts

- Body Processes Awareness

- Dance Composition

- Exploring Modern Dance

- Management Versus Leadership

- Job positions at fitness facilities

- Effect of COVID-19 on the Fitness Industry

Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Definition of leisure and recreation, impacts of leisure and recreation.

Leisure and recreation are different concepts but always seem to go hand in hand. People tend to use them in the same breath as if the concepts cannot exist apart from each other (Difference Between, 2012). They can and actually exist apart from each other. This essay seeks a deeper understanding of the two concepts and their impact on lifestyles.

Leisure relates to that free time at the disposal of a person in which the person can do what they feel like doing away from the routine (Veal, 1992). It is a condition of the mind marked by the time without obligations coupled with willing optimism (Veal, 1992). Leisure does not posit an activity; it can be the absence of activity too (Veal, 1992). At such times, an individual is not under any compulsion to do a particular activity but has discretion to choose (Veal, 1992).

Recreation, on the other hand, is the experiences and expeditions a person chooses to pursue at the spare time (Merriam-Webster, 2013). The experiences and expeditions chosen by the individual give an individual energy to resume routine duties. (Veal, 1992). In relation to leisure, recreation is any activity performed during leisure time and includes shopping, hiking among others (Veal, 1992).

Deriving from the above distinction, leisure is the time at one’s disposal to perform the non-routine activities and is usually rooted in the mind. Recreation is a pursuit that an individual engages in during leisure time. Recreation is an activity of leisure (Human Kinetics, 2013).

Concerning health, recreational activities enable an individual to relax by giving a pacifying wellness to the nerves (scilifestyle, 2012). Moreover, it helps an individual to vent out tension and conserve equilibrium. Recreation reduces stress too and enables the individual to keep minor ailments at bay (Definitions of leisure, play, and recreation, 2013).

On the social aspect, recreation affords social benefits to an individual as it enables the individual to encounter likeminded friends and build healthy relationships with them (Recreation, n.d.). Likeminded people are likely to come up with mutually beneficial ideas or activities and this enables the group members to achieve things the individual would have never achieved alone in their routine activities. Such initiatives include visiting the less fortunate members of the society as a group or coming up with an investment or welfare groups.

Leisure activities have an impact on the economy too. Such activities include tourism activities, visiting amusement parks and restaurants. This helps in building the economy through fees and costs incurred because more business means more revenues to the government and growth in development. Leisure is the fastest growing industry in United Kingdom (Osborne, 2010). In addition, when leisure groups meet and start investment groups, it boosts both the individual and state economy.

Leisure time affords people to catch up and participate in the political sphere of life (David). This happens through group meetings where members seek to inform others or get information during their meetings. It is also commonplace for governments to declare public holidays on days the citizens cast votes. This is leisure time, which enables the individual to perform the civic duty of electing public officials.

Finally, leisure activities have an impact on the culture in the sense that it provides a platform for cultural exchanges and learning. When tourists visit different places, they learn a lot from the host communities. Some have remained behind in tourist destination areas and adopted the local culture (David, Web).

Recreation activities are significant to both the individual and the community. For such activities to take place, leisure is necessary.

Brightbill, C. K. (1960). The challenge of leisure . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Difference Between Leisure and Recreation . (2012). Web.

David. Activity and Leisure . Web.

Definitions of leisure, play, and recreation. (2013). Human Kinetics . Web.

Recreation. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online. Web.

Osborne, A. (2010). Leisure could be one of UK’s fastest growing industries, if Government takes it seriously . Web.

Scilifestyle. (2012). The importance of recreation . Web.

Veal, A. J. (1992). Definitions of Leisure and Recreation. Australian Journal of Leisure and Recreation, 52. pp. 44-48. Web.

- Worldview Structure and Functions

- Various theories of human nature

- Recreation Zones and Public Administration Issues

- Leisure Service Providers Comparison

- Therapeutic Recreation - Prader-Willi Syndrome

- Nietzsche’s Zarathustra is a Camusian Absurd Hero, That’s to Say He Has No Hope

- Nature Interaction with Humans

- A Matter of Life and Death, or Did You Hear Someone Knocking?

- Philosophy as a Way of Life

- Happiness Meaning and Theories

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, April 16). Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-leisure-and-recreation/

"Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation." IvyPanda , 16 Apr. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-leisure-and-recreation/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation'. 16 April.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation." April 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-leisure-and-recreation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation." April 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-leisure-and-recreation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Philosophy of Leisure and Recreation." April 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-leisure-and-recreation/.

Elizabeth J. Peterson

Thinking Through Philosophy, Culture, and Psychology

A More Descriptive Definition of Leisure

What is “leisure”? The word is often considered to be simply the time spent outside of work, synonymous with ‘non-working’ time. This leaves space for too many questions to be a useful definition. Is sleep considered leisure? Watching television? What about commuting or eating dinner? Is housework leisure? Clearly, we need a more exact and helpful description.

The question, “What is leisure?” is seemingly philosophical, but practical because it relates to so much advice we hear today about a need to find rewarding hobbies and ways to reduce stress. How can we reduce stress, though, if we don’t know which activities actually help with stress? We’ve heard for decades that Americans don’t use their vacation time – perhaps it’s because we haven’t any idea what to do with it? Defining leisure more clearly will help millions of Americans to identify the sorts of activities most likely to help them de-stress and improve themselves at the same time. The aim of this essay is to arrive at a working definition for leisure.

Continuing the conversation begun in Leisure Isn’t About Not Working, It’s About Improvement , the notion of leisure is much older than the emergence of the middle class. Today’s perception of the term is a far cry from the ancient Greek notion of leisure which usually involved exertion and creation, and included activities like wrestling, athletic competitions, pottery, and play music. Their understanding was leisure required effort and was done to accomplish a purpose. This means the activity was done for its own sake, as in the playing of an instrument, painting, or woodworking. True leisure isn’t a “side hustle,” either. The leisurely painter dabs at his canvas for his own enjoyment; the leisurely violinist learns and performs Beethoven not because she needs to perform in order to eat, but for the thrill of playing iconic classical compositions. The idea that passive consumption or spending exorbitant amounts of money is leisure is a recent development.

Does leisure involve consumption?

Thorstein Veblen’s 1899 Theory of the Leisure Class describes the new phenomenon of the leisure class, an upper class which emerged in the 1850s who are neither nobility nor rulers, but wealthy enough they don’t have to work. The leisure class signal their elite position in how they spend their days and time; on frivolous purchases; by collecting collegiate degrees a status symbols, not as a requirement for their profession; in trophy hunting; and fussy or even impractical dressing.

The key argument of Veblen’s Theory , and the most identifiable feature of the leisure class, is their participation in activities which serve no economic purpose. This includes such hobbies as hunting, gambling, learning multiple languages, playing instruments, practicing grammar or writing belles lettres ; all markers of much time and money to spend.

Veblen’s work considers consumption a central tenet of the leisure class. Veblen even coined the term “conspicuous waste,” in reference to the superfluous goods flaunted by this class, like fur coats, awards of distinction, the building of ostentatious houses, breeding and racing of horses, etc. His theory was based on signaling; you can’t automatically size up how much money a person has, so the leisure class developed signs which signaled to others they could afford to spend money on frivolous chattel. This elite signaling then trickles down to the working classes. Modern examples include buying (and discarding) fashionable garments every season, buying new cars every year, collecting art, or gambling. It is all conspicuous consumption designed to membership in a leisure class, thereby distancing themselves from the working class.

Does the leisure class actually encapsulate the term leisure in any way? The leisure class are concerned with appearances and maintaining their elite status. True leisure is not externally motivated like this; leisure is about nourishing and growing the mind and heart. It’s about taking the time to become a better and wiser person. However, the stigma of doing nothing all day remains in our productivity minded society; one must be able to show what they’ve done with their time and resources. For this reason, the signal aspect of Veblen’s leisure class is still very much necessary to our definition, while consumption is not.

The more ancient and Greek notions would suggest consumption is not only not required, but antithetical to leisure. What we today consider “leisure” time is mostly spent consuming, usually watching television or scrolling social media. Our more established descriptions involve building, rather than passively consuming. This would suggest true leisure is meant to enrich, not simply passing non-working time, and is not primarily concerned with consumption.

Does leisure involve creation?

Does leisure require creating something? A painting, a new understanding of a concept, a beautifully played sonata; some sort of creation one can point to and say, “This is how I’ve spent my time.” A requirement of creating something new does square nicely with Veblen’s theory. He points to the various insignias, awards, trophies, and distinctions the leisure class weave as social proof they spend their time on costly things, though only on activities not associated with manual labor:

“As seen from the economic point of view, leisure, considered as an employment, is closely allied in kind with the life of exploit; and the achievements which characterise a life of leisure, and which remain as its decorous criteria, have much in common with the trophies of exploit. But leisure in the narrower sense, as distinct from exploit and from any ostensibly productive employment of effort on objects which are of no intrinsic use, does not commonly leave a material product. The criteria of a past performance of leisure therefore commonly take the form of “immaterial” goods. Such immaterial evidences of past leisure are quasi-scholarly or quasi-artistic accomplishments and a knowledge of processes and incidents which do not conduce directly to the furtherance of human life.” -Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

Today’s leisure class signals might include examples like Jay Leno and Jerry Seinfeld’s classic car collections; the antique and rare art collections of many upper class families; advanced degrees; learning multiple languages; involved gardens, and hunting trophies. All are examples of leisurely objects pursued at one time by the leisure class, but which trickled down over time to the working classes. In fact, trophy hunting in America, only really took off with the creation of the leisure class, around the 1850s. Every single example involves creating something – a trophy or signal – which didn’t exist before. Even going back further to the Greeks, they awarded physical competition and performed the plays written in leisure time. It would seem then, that historical examples require leisure to include the creation of some sort of social signal.

Improvement is required.

What is meant by “improvement”? Only that leisure is concerned with progress and becoming a more knowledgeable, empathetic, responsible, and well-rounded person. This ties into the signal requirement; there needs to be some demonstrable result of how one spends their time. This doesn’t necessarily mean you need to enter formal competitions, like sporting or painting competitions, but simply that whatever you choose to do, you are aiming to improve your skills and yourself. This can apply to virtually anything, of course; making wooden furniture, building birdhouses, running faster or lifting more weight, sharpening your photography skills, tightening your writing, understanding more about astrophysics; any venture where you can show improvement.

Is leisure active or passive?

Our more precise definition of leisure, then, is reserved for things like photography, studying, and gardening; the activities we do because we enjoy them and they make us better people, but don’t necessarily have a monetary incentive associated with them. Because leisure involves creating something new, it must be an active and not passive activity.

This leaves us in a quandary with so-called leisure activities. We often call things like watching television, conversation, scrolling social media, reading for enjoyment, or taking a walk leisure. These sorts of things would be considered pastimes- and there is nothing wrong with them – they simply do not fit into this more precise definition of leisure. While these can all be great activities and are certainly parts of modern life, considering them leisure seems a step too far. In order to refresh our minds, we have to engage and use our minds. Passive activities simply don’t meet this requirement. Likewise, normal healthy activities like exercise and eating aren’t included as leisure because they aren’t done with a specific goal of improvement.

A definition.

In my previous essay on the topic I concluded, “Leisure refers to purposeful activities that nourish and enrich a person. While we have more free time than ever, we engage in less true leisure time.”

Today, we’ve expanded this definition by determining leisure is active, requiring the creation of some sort of signal to show others how we’ve spent our time, and secondly, it requires some form of personal development. True leisure refers to the activities one does in their free time by creating some object in the pursuit of improving oneself.

What are the implications of understanding leisure?

Why does leisure matter? Leisure is often how measure our lives – am I able to spend my time doing the things I want to do? Joseph Pieper called leisure the basis of culture. It’s what we all work toward, and we continue to find more efficient ways to complete work, presumably to spend our time on leisure. Most of us though, aren’t actually spending time on leisure, but on those passive activities which don’t reduce stress and aren’t helping us to find fulfillment. Instead we’re just passing time.

With a clearer understanding of leisure, and by proceeding with a more precise definition like the one we’ve concluded with today, we give ourselves a better idea of the kinds of activities we want to explore. A clearer definition helps us to ask whether we’re really engaged in anything, and how we’d like to see ourselves improve. It’s the adult equivalent of when your mom told you to go play outside instead of spending all day indoors. “Find something interesting to do.”

Leisure, truly, is what gives our lives color; it’s paint on the blank canvas of a day. Leisure offers fulfillment, which is the ingredient missing from modern life. We work jobs and come home to relax, but we don’t aim for fulfillment. In the past few decades marked by positive psychology, the message has been to chase happiness. The problem is happiness is a byproduct, not an end of itself. Fulfillment is found in having the freedom to choose what you want to do and having the ability to do that thing. Choosing truly leisurely activities will go a long way toward personal fulfillment.

We’ve refined the definition of leisure to have two requirements; the active creation of a signal and involving an element of demonstrable personal improvement. What remains to be seen is whether there are more components to true leisure, or if by refining the term we can bring meaningful, widespread change to the realities of modern life.

Painting: Auf der Ligethi Puszta (1884) by von Hörmann, Theodor (1840 – 1895).

You might also like

Hitchens’ Razor and the Burden of Proof

On “Exploring my Options”: An Argument for Making Commitments

Seven Lessons on Ego from Sophocles’ “Antigone”

Leisure, the Basis of Culture: An Obscure German Philosopher’s Timely 1948 Manifesto for Reclaiming Our Human Dignity in a Culture of Workaholism

By maria popova.

Today, in our culture of productivity-fetishism, we have succumbed to the tyrannical notion of “work/life balance” and have come to see the very notion of “leisure” not as essential to the human spirit but as self-indulgent luxury reserved for the privileged or deplorable idleness reserved for the lazy. And yet the most significant human achievements between Aristotle’s time and our own — our greatest art, the most enduring ideas of philosophy, the spark for every technological breakthrough — originated in leisure, in moments of unburdened contemplation, of absolute presence with the universe within one’s own mind and absolute attentiveness to life without, be it Galileo inventing modern timekeeping after watching a pendulum swing in a cathedral or Oliver Sacks illuminating music’s incredible effects on the mind while hiking in a Norwegian fjord.

So how did we end up so conflicted about cultivating a culture of leisure?

In 1948, only a year after the word “workaholic” was coined in Canada and a year before an American career counselor issued the first concentrated countercultural clarion call for rethinking work , the German philosopher Josef Pieper (May 4, 1904–November 6, 1997) penned Leisure, the Basis of Culture ( public library ) — a magnificent manifesto for reclaiming human dignity in a culture of compulsive workaholism, triply timely today, in an age when we have commodified our aliveness so much as to mistake making a living for having a life.

Decades before the great Benedictine monk David Steindl-Rast came to contemplate why we lost leisure and how to reclaim it , Pieper traces the notion of leisure to its ancient roots and illustrates how astonishingly distorted, even inverted, its original meaning has become over time: The Greek word for “leisure,” σχoλη , produced the Latin scola , which in turn gave us the English school — our institutions of learning, presently preparation for a lifetime of industrialized conformity , were once intended as a mecca of “leisure” and contemplative activity. Pieper writes:

The original meaning of the concept of “leisure” has practically been forgotten in today’s leisure-less culture of “total work”: in order to win our way to a real understanding of leisure, we must confront the contradiction that rises from our overemphasis on that world of work. […] The very fact of this difference, of our inability to recover the original meaning of “leisure,” will strike us all the more when we realize how extensively the opposing idea of “work” has invaded and taken over the whole realm of human action and of human existence as a whole.

Pieper traces the origin of the paradigm of the “worker” to the Greek Cynic philosopher Antisthenes, a friend of Plato’s and a disciple of Socrates. Being the first to equate effort with goodness and virtue, Pieper argues, he became the original “workaholic”:

As an ethicist of independence, this Antisthenes had no feeling for cultic celebration, which he preferred attacking with “enlightened” wit; he was “a-musical” (a foe of the Muses: poetry only interested him for its moral content); he felt no responsiveness to Eros (he said he “would like to kill Aphrodite”); as a flat Realist, he had no belief in immortality (what really matters, he said, was to live rightly “on this earth”). This collection of character traits appears almost purposely designed to illustrate the very “type” of the modern “workaholic.”

Work in contemporary culture encompasses “hand work,” which consists of menial and technical labor, and “intellectual work,” which Pieper defines as “intellectual activity as social service, as contribution to the common utility.” Together, they compose what he calls “total work” — “a series of conquests made by the ‘imperial figure’ of the ‘worker'” as an archetype pioneered by Antisthenes. Under the tyranny of total work, the human being is reduced to a functionary and her work becomes the be-all-end-all of existence. Pieper considers how contemporary culture has normalized this spiritual narrowing:

What is normal is work, and the normal day is the working day. But the question is this: can the world of man be exhausted in being “the working world”? Can the human being be satisfied with being a functionary, a “worker”? Can human existence be fulfilled in being exclusively a work-a-day existence?

The answer to this rhetorical question requires a journey to another turning point in the history of our evolving — or, as it were, devolving — understanding of “leisure.” Echoing Kierkegaard’s terrific defense of idleness as spiritual nourishment , Pieper writes:

The code of life in the High Middle Ages [held] that it was precisely lack of leisure, an inability to be at leisure, that went together with idleness; that the restlessness of work-for-work’s-sake arose from nothing other than idleness. There is a curious connection in the fact that the restlessness of a self-destructive work-fanaticism should take its rise from the absence of a will to accomplish something. […] Idleness, for the older code of behavior, meant especially this: that the human being had given up on the very responsibility that comes with his dignity… The metaphysical-theological concept of idleness means, then, that man finally does not agree with his own existence; that behind all his energetic activity, he is not at one with himself; that, as the Middle Ages expressed it, sadness has seized him in the face of the divine Goodness that lives within him.

We see glimmers of this recognition today, in sorely needed yet still-fringe notions like the theology of rest , but Pieper points to the Latin word acedia — loosely translated as “despair of listlessness” — as the earliest and most apt formulation of the complaint against this self-destructive state. He considers the counterpoint:

The opposite of acedia is not the industrious spirit of the daily effort to make a living, but rather the cheerful affirmation by man of his own existence, of the world as a whole, and of God — of Love, that is, from which arises that special freshness of action, which would never be confused by anyone [who has] any experience with the narrow activity of the “workaholic.” […] Leisure, then, is a condition of the soul — (and we must firmly keep this assumption, since leisure is not necessarily present in all the external things like “breaks,” “time off,” “weekend,” “vacation,” and so on — it is a condition of the soul) — leisure is precisely the counterpoise to the image for the “worker.”

But Pieper’s most piercing insight, one of tremendous psychological and practical value today, is his model of the three types of work — work as activity, work as effort, and work as social contribution — and how against the contrast of each a different core aspect of leisure is revealed. He begins with the first:

Against the exclusiveness of the paradigm of work as activity … there is leisure as “non-activity” — an inner absence of preoccupation, a calm, an ability to let things go, to be quiet.

In a sentiment Pico Iyer would come to echo more than half a century later in his excellent treatise on the art of stillness , Pieper adds:

Leisure is a form of that stillness that is necessary preparation for accepting reality; only the person who is still can hear, and whoever is not still, cannot hear. Such stillness is not mere soundlessness or a dead muteness; it means, rather, that the soul’s power, as real, of responding to the real — a co -respondence, eternally established in nature — has not yet descended into words. Leisure is the disposition of perceptive understanding, of contemplative beholding, and immersion — in the real.

But there is something else, something larger, in this conception of leisure as “non-activity” — an invitation to commune with the immutable mystery of being . Pieper writes:

In leisure, there is … something of the serenity of “not-being-able-to-grasp,” of the recognition of the mysterious character of the world, and the confidence of blind faith, which can let things go as they will. […] Leisure is not the attitude of the one who intervenes but of the one who opens himself; not of someone who seizes but of one who lets go, who lets himself go, and “go under,” almost as someone who falls asleep must let himself go… The surge of new life that flows out to us when we give ourselves to the contemplation of a blossoming rose, a sleeping child, or of a divine mystery — is this not like the surge of life that comes from deep, dreamless sleep?

This passage calls to mind Jeanette Winterson’s beautiful meditation on art as a function of “active surrender” — a parallel quite poignant in light of the fact that leisure is the seedbed of the creative impulse, absolutely necessary for making art and doubly so for enjoying it.

Pieper turns to the second face of work, as acquisitive effort or industriousness, and how the negative space around it silhouettes another core aspect of leisure:

Against the exclusiveness of the paradigm of work as effort, leisure is the condition of considering things in a celebrating spirit. The inner joyfulness of the person who is celebrating belongs to the very core of what we mean by leisure… Leisure is only possible in the assumption that man is not only in harmony with himself … but also he is in agreement with the world and its meaning. Leisure lives on affirmation. It is not the same as the absence of activity; it is not the same thing as quiet, or even as an inner quiet. It is rather like the stillness in the conversation of lovers, which is fed by their oneness.

With this, Pieper turns to the third and final type of work, that of social contribution:

Leisure stands opposed to the exclusiveness of the paradigm of work as social function. The simple “break” from work — the kind that lasts an hour, or the kind that lasts a week or longer — is part and parcel of daily working life. It is something that has been built into the whole working process, a part of the schedule. The “break” is there for the sake of work. It is supposed to provide “new strength” for “new work,” as the word “refreshment” indicates: one is refreshed for work through being refreshed from work. Leisure stands in a perpendicular position with respect to the working process… Leisure is not there for the sake of work, no matter how much new strength the one who resumes working may gain from it; leisure in our sense is not justified by providing bodily renewal or even mental refreshment to lend new vigor to further work… Nobody who wants leisure merely for the sake of “refreshment” will experience its authentic fruit, the deep refreshment that comes from a deep sleep.

To reclaim this higher purpose of leisure, Pieper argues, is to reclaim our very humanity — an understanding all the more urgently needed today, in an era where we speak of vacations as “digital detox” — the implication being that we recuperate from, while also fortifying ourselves for, more zealous digital retox, so to speak, which we are bound to resume upon our return.

Leisure is not justified in making the functionary as “trouble-free” in operation as possible, with minimum “downtime,” but rather in keeping the functionary human … and this means that the human being does not disappear into the parceled-out world of his limited work-a-day function, but instead remains capable of taking in the world as a whole, and thereby to realize himself as a being who is oriented toward the whole of existence. This is why the ability to be “at leisure” is one of the basic powers of the human soul. Like the gift of contemplative self-immersion in Being, and the ability to uplift one’s spirits in festivity, the power to be at leisure is the power to step beyond the working world and win contact with those superhuman, life-giving forces that can send us, renewed and alive again, into the busy world of work… In leisure … the truly human is rescued and preserved precisely because the area of the “just human” is left behind… [But] the condition of utmost exertion is more easily to be realized than the condition of relaxation and detachment, even though the latter is effortless: this is the paradox that reigns over the attainment of leisure, which is at once a human and super-human condition.

This, perhaps, is why when we take a real vacation — in the true sense of “holiday,” time marked by holiness, a sacred period of respite — our sense of time gets completely warped . Unmoored from work-time and set free, if temporarily, from the tyranny of schedules, we come to experience life exactly as it unfolds, with its full ebb and flow of dynamism — sometimes slow and silken, like the quiet hours spent luxuriating in the hammock with a good book; sometimes fast and fervent, like a dance festival under a summer sky.

Leisure, the Basis of Culture is a terrific read in its totality, made all the more relevant by the gallop of time between Pieper’s era and our own. Complement it with David Whyte on reconciling the paradox of “work/life balance,” Pico Iyer on the art of stillness , Wendell Berry on the spiritual rewards of solitude , and Annie Dillard on reclaiming our everyday capacity for joy and wonder .

— Published August 10, 2015 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/08/10/leisure-the-basis-of-culture-josef-pieper/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture josef pieper philosophy psychology, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Themed Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Ilona Kickbusch Award

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Online

- Open Access Option

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Promotion International

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Leisure as a context for active living, recovery, health and life quality for persons with mental illness in a global context, recovery defined, re-defining active living, enjoyable and meaningful leisure as a context for active living, purpose statement, toward a holistic/ecological framework of the roles of leisure in active living, recovery and health/life-quality promotion among persons with mental illness, potential contributions of leisure to active living, recovery and health/life quality among people with mental illness, importance of cultural and environmental factors and health care systems, holistic, person-centered, recovery-oriented, strengths-based, and culturally sensitive health and human care.

- < Previous

Leisure as a context for active living, recovery, health and life quality for persons with mental illness in a global context

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Yoshitaka Iwasaki, Catherine P. Coyle, John W. Shank, Leisure as a context for active living, recovery, health and life quality for persons with mental illness in a global context, Health Promotion International , Volume 25, Issue 4, December 2010, Pages 483–494, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq037

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Globally, the mental health system is being transformed into a strengths-based, recovery-oriented system of care, to which the concept of active living is central. Based on an integrative review of the literature, this paper presents a heuristic conceptual framework of the potential contribution that enjoyable and meaningful leisure experiences can have in active living, recovery, health and life quality among persons with mental illness. This framework is holistic and reflects the humanistic approach to mental illness endorsed by the United Nations and the World Health Organization. It also includes ecological factors such as health care systems and environmental factors as well as cultural influences that can facilitate and/or hamper recovery, active living and health/life quality. Unique to this framework is our conceptualization of active living from a broad-based and meaning-oriented perspective rather than the traditional, narrower conceptualization which focuses on physical activity and exercise. Conceptualizing active living in this manner suggests a unique and culturally sensitive potential for leisure experiences to contribute to recovery, health and life quality. In particular, this paper highlights the potential of leisure engagements as a positive, strengths-based and potentially cost-effective means for helping people better deal with the challenges of living with mental illness.

Globally, mental disorders are prevalent across all cultures—more than 450 million people suffer from mental disorders worldwide ( Hyman et al ., 2006 ). The World Health Organization ( WHO, 2001a ) estimated that mental disorders would account for 15% of the total burden of disease in the year 2020, and showed that mental disorders would be the principal cause of Years Lived with Disability internationally. Despite advances in pharmacological and psychosocial treatments, the quality and adequacy of health care for persons with mental illness ‘remain fragmented, disconnected, and often inadequate, frustrating the opportunity for recovery’ ( New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003 , p. 1).

Within Transforming Mental Health Care in America, Federal Action Agenda , recovery is emphasized as the single most important goal for the mental health system ( USDHHS, 2006 ). Also, as a follow-up to the 2001 World Health Report, the mental health Global Action Programme (mhGAP) was developed and provides a strategy for closing the gap between what is urgently needed and what is currently available to help individuals and families affected by mental illness ( WHO, 2001a ). Achieving the highest level of recovery was identified as a major goal of the mhGAP (WHO).

According to the National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery , derived from over 110 expert panelist deliberations, recovery is defined as ‘a journey of healing and transformation enabling a person with a mental health problem to live a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential’ ( USDHHS, 2006 ). Recovery involves a holistic, person-centered, strengths-based approach that focuses on: self-direction, respect, hope, connectedness, peer support, empowerment, spiritual fulfillment and meaningful life (including education, employment and leisure) ( Sells et al ., 2006 ; USDHHS, 2006 ). The practical use of these key elements of recovery (e.g. hope as the very idea that recovery is possible) was emphasized in Sartorius and Schulze's ( Sartorius and Schulze, 2005) document based on reports from the World Psychiatric Association's effort to fight against stigma of mental illness.

Understanding the true meaning and essence of recovery as an expectation for and by people with mental illness is a global concern. Davidson and Roe conducted an extensive review of the empirical literature on recovery from an international perspective ( Davidson and Roe, 2007) . They identified two complementary meanings of recovery—‘The first meaning of recovery from mental illness derives from over 30 years of longitudinal clinical research, which has shown that improvement is just as common, if not more so, than progressive deterioration. The second meaning of recovery in derives from the Mental Health Consumer/Survivor Movement, and refers instead to a person's rights to self-determination and inclusion in community life, despite continuing to suffer from mental illness’ (p. 459).

Ramon et al . also surveyed the meanings of the term recovery from a global perspective, with particular attention given to service users' definitions ( Ramon et al ., 2007) . They concluded, ‘Recovery is not about going back to a pre-illness state, and means something very different from the ‘old’ emphasis on controlling symptoms or cure. Rather, it is a complex and multifaceted concept, both a process and an outcome, the features of which include strength, self-agency and hope, interdependency and giving, and systematic effort, which entails risk-taking’ (p. 119).

The concept of recovery is based on a vision that a majority of people with mental illness can lead meaningful lives in their community ( Clay et al ., 2005 ). Within the USA, active living is a public health issue and its health benefits have been well documented. Beneficial outcomes include improved health ( Tudor and Bassett, 2004 ), physical functioning ( Brach et al ., 2004 ), health-related quality of life ( Brown et al ., 2004 ) and lower mortality ( Gregg et al ., 2003 ). However, active living is typically understood from a physical activity/exercise perspective. This is increasingly the case in an international context, as well (e.g. Murray, 2006 ; Carless, 2007 ). While physical activity and exercise is undeniably a core component in active living, there is a risk of over-emphasizing physical activity as the defining element of active living. This creates a biased view of active living by overlooking the potential value of other types of activities that promote active engagement in one's life, such as non-physical or less physically demanding forms of leisure (e.g. expressive/creative, social, spiritual or cultural forms of leisure).

We propose a broader and more strength-based, humanistic approach to the conceptualization of active living. This conceptualization views active living as being actively engaged in living all aspects of one's life both personally and in families and communities in a meaningful and enriching way rather than the narrower conceptualization of active living, which is predominately biased toward physical activity and exercise only ( Iwasaki et al ., 2006 ; Kaczynski and Henderson, 2007 ). Both the United Nations (UN; Quinn et al ., 2002 ) and World Health Organization (WHO, 2005) support such a conceptualization, given their endorsement of a broad and strengths-based, human rights approach to health promotion among global populations (including individuals with disabilities such as mental illness) in both developing and developed countries.

A broader conceptualization of active living may be particularly salient to persons with mental illness not only because sedentary and inactive lifestyles are prevalent among this population group ( McElroy et al ., 2006 ), but also because their lives are often characterized by loneliness and isolation and a disconnection from their community ( Lemaire and Mallik, 2005 ). A conceptualization of active living that is attentive to the humanistic as well as physical outcomes derived from activity may be more effective in this population, especially since it can embrace the individual's need for meaning-seeking or -making. Examples of activities that illustrate this conceptualization of active living would include: (a) Tai Chi, a physical activity that promotes physical health but which also focuses on body-mind-spirit harmony; (b) social leisure activities with peers/friends that promote emotional health and which do not emphasize living with mental illness as an issue (i.e. stigma); and (c) culturally meaningful, spiritually refreshing and/or creative/expressive leisure activity such as art/crafts, music and dance that promote self-expression and identity.

In this paper, leisure is defined as a relatively freely chosen humanistic activity and its accompanying experiences and emotions (e.g. enjoyment and happiness) that can potentially make one's life more enriched and meaningful. The meaning-seeking or meaning-making functions of leisure have a long tradition in the leisure research field (e.g. Shaw, 1985 ; Samdahl, 1988 ; Henderson et al ., 1996 ; Kelly and Freysinger, 2000 ). Recently, Iwasaki ( Iwasaki, 2008) identified key pathways to meaning-making through leisure-like pursuits in global contexts. He showed that in people's quest for a meaningful life, these leisure-generated pathways seem to simultaneously involve both ‘remedying the bad’ (e.g. coping with/healing from stressful or traumatic experiences, reducing suffering) and ‘enhancing the good’ (e.g. promoting life satisfaction and life quality) through facilitating, for example, positive emotions, identities, spirituality, connections and a harmony, human strengths and resilience, and learning and human development across the lifespan. Overall, these notions of leisure emphasize: (a) meaning-oriented emotional, spiritual, social and cultural properties of leisure that reflect a broader and humanistic perspective than physical activity alone, and (b) the role of meaning-making through leisure in promoting active living, health and life quality for people including individuals with mental illness. Leisure is a key context for active living and an important pathway toward recovery, health promotion and life-quality enhancement. Leisure represents broad aspects of human functioning including emotional, spiritual, social, cultural and physical elements. The forms that leisure expressions take (e.g. sport, exercise, art, crafts, visits with friends) are secondary to the meanings derived from and associated with the leisure experiences, and it is the outcomes/meanings derived that present the potential contributions to these pathways.

Recent research has shown that leisure opportunities (e.g. through a peer-run program at recreation centers) can play a key role in the recovery of persons with mental illness ( Swarbrick and Brice, 2006 ). Davidson et al .'s multinational study on recovery from serious mental illness highlighted the importance of going out and engaging in ‘normal’ activities, and having meaningful social roles and positive relationships outside of the formal mental health system ( Davidson et al ., 2005) . Not only can leisure and recreation provide an opportunity for going out and socially valued normal activities, but these activities can also provide a context for having a positive relationship and pursuing a meaningful social role among people including individuals with disabilities ( Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005 ; Iwasaki et al ., 2006 ; Hutchinson et al ., 2008 ). Fullagar's qualitative study with 48 women with depression in Australia found that creative (e.g. art/craft, gardening, writing, music), actively embodied (e.g. walking, yoga, Tai Chi, swimming) and social (e.g. cafes, friend/support groups) leisure activities acted as a counter-depressant by eliciting positive emotions (e.g. joy, pleasure, courage) that facilitated recovery and transformation in ways that biomedical treatments could not ( Fullagar, 2008) . These findings show important practical implications that advocate a more humanistic, strengths-based and potentially cost-effective health-care approach.

Unfortunately, active living and health promotion research for individuals with mental illness has never directly integrated the concept of recovery. Conceptualizing active living from a broader, humanistic and meaning-oriented perspective is proposed as being preferable over a narrow single-dimensional (e.g. physical activity) perspective. Also, leisure pursuits seem to provide an important context for active living and recovery-oriented health and life-quality promotion ( Godbey et al ., 2005 ; Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005 ; Sallis et al ., 2005 ). This potential, however, has been neglected (and perhaps undervalued) and seldom studied directly. Therefore, based on an integrative review of the literature, this paper presents a heuristic conceptual framework of the potential role of enjoyable and meaningful leisure in facilitating active living, recovery and health/life-quality promotion among persons with mental illness from a more holistic/ecological and humanistic perspective in a global cross-cultural context. Holistic and ecological concepts supported by Ng et al . ( Ng et al ., 2009) , DeLeon ( DeLeon, 2000) and Bambery and Abell ( Bambery and Abell, 2006) are a basis of our framework.

First, inspired by Chinese medicine's holistic model, Ng et al . ( Ng et al ., 2009) conceptualized an Eastern body-mind-spirit approach to achieving a primary therapy goal of facilitating a harmonious equilibrium within oneself as well as between oneself and the natural and social environment. Advocating the notion of ‘beyond survivorship,’ this approach focuses on human strengths and thriving. For example, in this approach, striving for a vibrant mind/spirit is pursued through Tai Chi and Qigong exercises, which enable one to appreciate and affirm one's life through meaning-making, which can be a catalyst to transform clients for positive change. The aim of this holistic approach is to activate an interconnected body-mind-spirit system in order to reestablish a balance and harmony among clients contextualized within their broader community, society and environment.

DeLeon's Therapeutic Community (TC) model is also relevant to this holistic and ecological concept ( DeLeon, 2000) . The TC model is more comprehensive and integrative than those based on symptom reduction alone. It emphasizes the transformative influences of one's identity and culture through collective intervention formats using the power of social groups in augmenting active learning, personal and social responsibility, and collective growth. DeLeon's TC model aims to achieve an existentially derived and authentic purpose in life as the primary value of living, which he theorizes to include personal and social accountability, collective learning, community involvement and good citizenry within a broad societal system. These concepts are also in line with Bambery and Abell's ( Bambery and Abell, 2006) urge for shifting the mental health field's current paradigm of psychopathology to a more holistic and ecological perspective by supporting Fromm's ( Fromm, 1941 , 1955 , 1976 ) advocacy for a more comprehensive treatment of individuals including its sensitivity to a macro-context in which society (e.g. culture, historical forces, social class) influences one's behavior. These notions are further supported by Bambery and Abell's case study that addressed both individual psychopathology and larger societal ills influencing their study participants' lives including family, social and environmental factors from an ecological perspective.

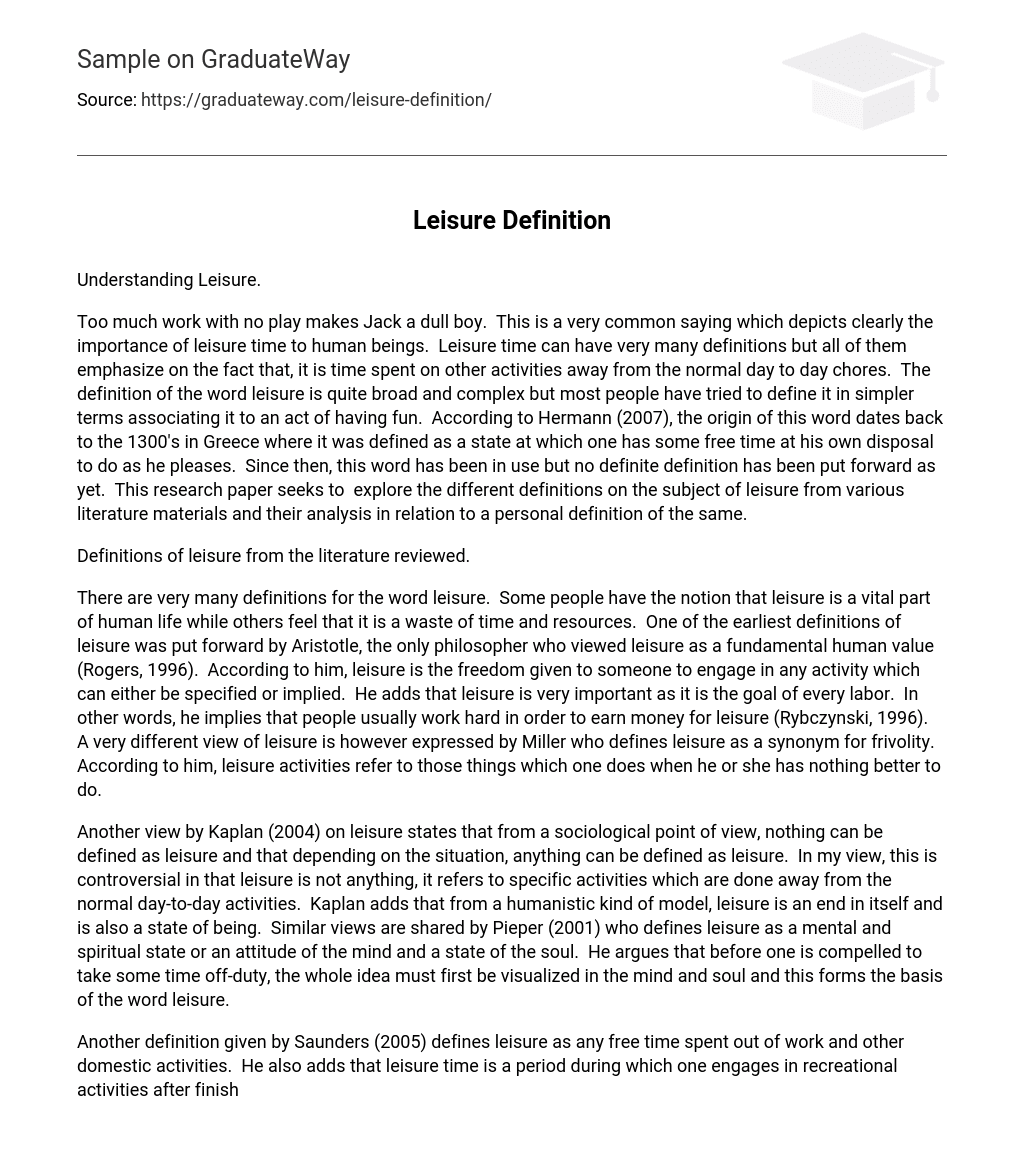

Using a holistic and ecological perspective, our proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1 ) depicts the potential interrelationships among active living, recovery and health/life quality among people with mental illness. These potential pathways were derived from an extensive and comprehensive review of the literature including both qualitative and quantitative data from studies conducted in a cross-cultural, international context.

A heuristic holistic/ecological framework of the roles of leisure in active living, recovery and health/life-quality promotion among persons with mental illness. Broken lines (---) represent transactional reciprocal relationships and connectedness between the various factors depicted in the framework.

In this framework, enjoyable and meaningful leisure expressions are emphasized as a key context for active living, and as a major pathway to recovery, health and life quality. We recognize that other activities (e.g. employment) also contribute to active living and the reader should not think that we are placing leisure as the sole construct contributing to active living. Rather, this conceptual framework is developed to highlight how enjoyable and meaningful leisure, an often neglected life activity in the rehabilitation process, can and should be considered when designing interventions to promote active living, recovery and health/life quality for individuals with mental illness.

As depicted with bi-directional arrows, enjoyable and meaningful leisure is assumed to function as a critical proactive agent via its potential to promote personal identity and spirituality, positive emotions, harmony and social connections, effective coping and healing, human development, and physical and mental health. The bi-directional arrows also indicate the converse that personal identity and spirituality, harmony and social connections, coping and healing, etc., in turn, influence leisure expressions.

The circular structure in our framework illustrates a system of micro and macro factors from a holistic/ecological perspective. The factors within the outer circle (i.e. cultural, environmental and health-care system factors) are considered more macro than the factors within the inner circle. Also, both the distinction and interconnectedness between micro and macro factors are implied. For example, personal identity and spirituality as a micro element are located within the inner circle along with other potential leisure outcomes such as positive emotions, harmony and social connections, coping/healing and health, which are distinguished from (yet are connected to) cultural factors as a macro element. On the other hand, active living, recovery and life quality are highlighted as key leisure-generated outcomes, contextualized within the outer layer of macro factors (i.e. cultural, environmental and health-care system factors). These transactional reciprocal relationships and connectedness between the various factors within multiple layers of circles are depicted with broken lines (---) of circles in the conceptual framework. It must, however, be cautioned that our intention here is not to suggest causation. Rather, our conceptual framework is presented as a ‘heuristic’ map to stimulate a more balanced, holistic/ecological and humanistic orientation of practice toward active living, recovery and the promotion of health and life quality among culturally diverse groups of people with mental illness in a global context. It is also recognized that this reciprocal transaction can be both positive and negative. That is, discretionary time behaviors (leisure) can be detrimental to health just as environmental factors can support or impede meaningful leisure experiences. Nevertheless, this article focuses on ideal transaction.

Leisure's potential has increasingly been shown in a series of empirical research. For example, Lloyd et al .'s ( Lloyd et al ., 2007) study with 44 Australian clubhouse members with mental illness found a significant association between leisure motivation (measured with leisure motivation scale, Beard and Ragheb, 1983 ) and recovery (measured with recovery assessment scale, Corrigan et al ., 2004 ). Specifically, individuals who were motivated to engage in leisure were functioning well at a higher level of recovery, while goal- and success-oriented leisure motivation ( r = 0.84) and leisure motivation toward personal confidence and hope ( r = 0.83) had strongest correlations with recovery. These findings are consistent with Hodgson and Lloyd's ( Hodgson and Lloyd, 2002) qualitative study showing that the involvement in leisure activities plays a vital role in relapse prevention for individuals with dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance misuse, and with Moloney ( Moloney, 2002) and Ryan ( Ryan, 2002) who emphasized that the engagement in leisure is instrumental in a journey for recovery from a consumer perspective. Trauer et al .'s study with 55 clients with serious mental illness reported that one's satisfaction with leisure had the strongest association with global well-being (GWB) ( r = 0.76) ( Trauer et al ., 1998) . This association between leisure satisfaction and GWB was greater than any other life-domain measures such as health, family and social relations. Also, Lloyd et al .'s ( Lloyd et al ., 2001) study found that individuals with mental illness who participated in a community-based rehabilitation program reported positive effects of leisure on intellectual stimulation, relaxation and enjoyable relationships with others. By integrating the findings of these studies, Lloyd et al . ( Lloyd et al ., 2007) emphasized that leisure-based programs should be considered for community reintegration and social inclusion of people with mental illness. This recommendation is in line with Heasman and Atwal's ( Heasman and Atwal, 2004) finding that leisure participation can contribute to greater social inclusion among British adults with mental illness.

Frances' ( Frances, 2006) evidence-based review highlighted the role of outdoor recreation (e.g. walking, cycling, hiking, kayaking, canoeing) as a viable therapeutic means for people with mental illness, particularly its role in facilitating positive identity and life quality ( Frances, 2006) . Also, Babiss' ( Babiss, 2002) ethnographic study of women with mental illness provided evidence that expressive activities such as art, music, writing and dance promote the process toward recovery, specifically as a vehicle for learning about self and for identifying feelings one cannot express verbally. Babiss indicated that ‘expression just for the sake of expression has value’ (p. 118), while emphasizing ‘the stunning importance of the human interaction and the human touch’ (p. 106). In fact, self-expressions and meaningful interpersonal interactions are two key benefits of leisure and recreation ( Driver and Bruns, 1999 ).

Yanos and Moos' integrated model of the determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia identified leisure activities as a key dimension of social functioning ( Yanos and Moos, 2007) . Minato and Zemke's study with 89 community residents (aged 19–64 years) with schizophrenia in Sapporo, Japan showed that leisure can act as a stress-reliever ( Minato and Zemke, 2004) . As shown earlier, Davidson et al .'s ( Davidson et al ., 2005) international study (conducted in Italy, Norway, Sweden and the USA) found that going out and engaging in normal activities, having meaningful social roles and maintaining positive interpersonal relationships outside of the formal mental health system were found as salient themes of recovery processes.

From a positive strengths-based perspective, Carruthers and Hood ( Carruthers and Hood, 2004) stressed the role of therapeutic recreation services for individuals with mental illness in facilitating resilience, thriving and life satisfaction. Pedlar et al .'s study pointed to the importance of informal recreation opportunities (e.g. informal get-together during which women inmates with mental health challenges living in a prison system spent a leisurely evening together with people from the community) rather than a conventional formalized intervention to facilitate friendship and community reintegration ( Pedlar et al ., 2008) .

The notion of leisure as an antidote to depressive symptomotology was shown in Fullagar's ( Fullagar, 2008) study with 48 Australian women with depression. This study drew on post-structural feminist theories of emotion to explore the significance of leisure within women's narratives of recovery from depression. Specifically, Fullagar found evidence that leisure: (a) helped open up positive experiences of self beyond the experiences with the medical/clinical treatment, (b) had transformative effects on gender identity (learning really ‘who I am’), (c) generated ‘hope’ that there is life beyond depression and (d) enabled the women to exercise a sense of entitlement to play and enjoy life. Importantly, recovery-oriented leisure practices involved setting new boundaries for self (e.g. personal space) and others, and elicited emotions (e.g. joy, pleasure, courage) that facilitated transformation in ways that biomedical treatments could not. Fullagar stated, ‘The recovery practices adopted by women were significant not because of the “activities” themselves but in terms of the meanings they attributed to their emerging identities. Women talked about how they engaged in leisure “for” themselves (e.g. alone or with others)’ through creative (e.g. art/craft, gardening, writing, reading, music, community theatre, self-education), actively embodied (e.g. martial arts, walking, bowls, dance, yoga, Tai Chi, swimming, meditation) and social activities (e.g. cafes, dance courses, support groups, pets, church, helping others) (p. 42).

Thus, active engagements in leisure give attention to the experiences and meanings derived from these engagements. For example, individuals with mental illness can engage in a nature walk with peers and/or friends that can provide an opportunity to gain social (e.g. companionship), emotional (e.g. positive moods) and spiritual (e.g. spiritual renewal) benefits within a natural environment beyond physical and physiological benefits of a nature walk. Empirical evidence is emerging to demonstrate that enjoyable and meaningful leisure can facilitate coping with stress and healing from trauma, and promote hope, identity (e.g. deeper understanding of self), connectedness, appreciation for life, human growth/transformation and life quality among people including persons with mental illness (e.g. Kleiber et al ., 2002 ; Hutchinson et al ., 2006 , 2008 ; Iwasaki et al ., 2006 ). Consistent with this evidence, Ritsner et al .'s ( Ritsner et al ., 2005) study with Jewish or Arab Israelis with mental illness found that leisure activities facilitated finding meaning in life, which counteracted negative states of depression and emotional distress. In addition, a recent National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI, 2004) document included an illustration about the power of enjoyable and meaningful forms of actively engaged leisure for individuals with serious mental illness.

Furthermore, from a health-promoting perspective, leisure seems to have the potential to reduce secondary health conditions (e.g. obesity) of individuals with mental illness. Healthy People 2010 ( USDHHS, 2000 ) defines secondary conditions as ‘medical, social, emotional, family, or community problems that a person with a primary disabling condition likely experiences.’ It has been shown that the reduction and prevention of secondary conditions are very important for persons with mental illness because of their adverse effects on health and life quality ( Johnson, 1997 ; Perese and Perese, 2003 ; Merikangas and Kalaydjian, 2007 ). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) also recognizes the importance of managing secondary conditions of people with disabilities ( WHO, 2001b ). Beyond the primary disabling conditions, physical, social and environmental factors amendable through public health intervention are widely acknowledged to mediate the development of secondary conditions ( Wilber et al ., 2002 ), yet targeted lifestyle interventions for persons with mental illness are lacking ( Bradshaw et al ., 2005 ).

Within our model, and supported by recent research findings, the potential exists in utilizing leisure activities within a health promotion framework, especially physically and socially active leisure. For example, Richardson et al . ( Richardson et al ., 2005) implemented an 18-week lifestyle intervention program to promote physical activity and healthy eating among 39 individuals with serious mental illness and found observable weight loss (to reverse weight gain as a secondary condition) over the course of the intervention. Also, Cournos and Goldfinger ( Cournos and Goldfinger, 2005) reported some success with a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention to promote walking among individuals with comorbid depression and diabetes (i.e. another secondary condition). The role of social leisure in dealing with social isolation (still as another secondary condition) has been found (e.g. Heasman and Atwal, 2004 ; Davidson et al ., 2005 ; Pedlar et al ., 2008 ), as well as the role of leisure in relapse prevention for individuals with dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance misuse ( Hodgson and Lloyd, 2002 ).

The framework includes cultural factors, health care systems and other environmental factors (e.g. family and peer support, socio-economic living conditions, neighborhood and community including parks and recreation centers, educational and employment opportunities). The interactive effects of these macro factors are assumed to influence the other components included in the framework, which is consistent with an ecological perspective of health and disability ( WHO, 2001b ).

Giving attention to cultural factors (e.g. race/ethnicity) is a must in the conceptualizations of leisure, active living, recovery, health promotion, life quality and health care, and its interrelationships. For example, Davidson et al .'s ( Davidson et al ., 2005) multinational study showed that cultural differences among individuals with mental illness from each country were noted primarily in the nature of the opportunities and supports offered rather than in the nature of the recovery processes described. Mendenhall ( Mendenhall, 2008) discussed factoring culture into outcome measurement in mental health, while Warren ( Warren, 2007) described cultural aspects of bipolar disorder and interpersonal meaning for clients and psychiatric nurses. Also, Ida ( Ida, 2007) suggested that the critical role of culture should be acknowledged in the recovery and healing process within the context of ‘racism, sexism, colonization, homophobia, and poverty, as well as the stigma and shame associated with having a mental illness’ (p. 49). Hopper et al ., 2007) conducted a cross-cultural inquiry into marital prospects after psychosis, and Rosen ( Rosen, 2003) discussed how developed countries can learn from developing countries in challenging psychiatric stigma from a cross-cultural perspective. This may ‘include wider communal involvement in addressing external (psycho-sociocultural) causal or precipitating factors (e.g., losses, lack of meaningful role, spiritual crises) rather than relying on internal biological explanations and treatments’ ( Rosen, 2003 , p. S95). Fallot showed that spirituality is central to self-understanding and recovery experiences of many individuals with mental illness, and that recognizing the role of spirituality and religion in a particular culture is often essential to offering culturally competent services ( Fallot, 2001) . Also, Hwang et al . ( Hwang et al ., 2008) provided a conceptual paradigm for understanding how cultural factors (e.g. cultural meanings, norms, expressions) influence several core domains of mental health, including (a) the prevalence of mental illness, (b) etiology of disease, (c) phenomenology of distress, (d) diagnostic and assessment issues, (e) coping styles and help-seeking pathways and (f) treatment and intervention issues. In addition, cultural meanings of leisure engagements for racial/ethnic minorities should be acknowledged rather than imposing a dominant western idea of leisure, as emphasized in Iwasaki et al .'s ( Iwasaki et al ., 2007) call for a power-balance between East and West in leisure research.

Besides cultural factors, the other macro factors included in the framework represent health care systems and other environmental factors. Certainly, access to and the approaches used in mental health care systems will affect active living and recovery, including the propensity to consider leisure-based active living in overall health and life quality. Consider, for example, the personal recovery experiences described by Schiff ( Schiff, 2004) . As a consumer–survivor, Schiff described a recovery process that involved connections with others, the environment and the world as a key contributor to life quality. Specifically, besides her inner desire for ‘wanting to get better’ (p. 215), she talked about her own recovering experiences facilitated by her relationships with patients, medical staff and some others at university, and through reclaiming social roles with peers including helping others who have mental illness. Similarly, from a consumer perspective, Happell's ( Happell, 2008) study found a supportive environment, especially connectedness with and encouragement/support from staff and peers, as a key aspect of mental health services to enhance recovery, while emphasizing that increased attention should be given to the views and opinions of consumers to develop more responsive mental health services. Also, Yanos and Moos ( Yanos and Moos, 2007) identified various environmental conditions—including social climate (e.g. community stigma, economic conditions, local mental health policies), resources (e.g. social support, family resources) and stressors (e.g. family relationships, neighborhood disadvantage)—as key determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia.

Besides ensuring the quality and accessibility of resources essential for daily community living (e.g. safety/security, health care, educational and employment opportunities), creating a more active-living-friendly neighborhood and community for people with mental illness is very important. To achieve this aim, however, the maintenance of accessible/inclusive, user-friendly and pleasant parks and recreation centers that offer a diverse range of opportunities for all to enjoy quality leisure time is a top priority. Recently, both American Journal of Preventive Medicine (e.g. Godbey et al ., 2005 ; Sallis et al ., 2005 ) and Leisure Sciences (e.g. Henderson and Bialeschki, 2005 ) featured a special issue on the role of recreation and leisure in promoting active lifestyles in neighborhoods and communities (e.g. engineering a safe/secure, visually attractive and user-friendly urban-park landscape) from a transdisciplinary perspective (e.g. urban planning, landscape architecture, engineering, leisure sciences, medicine, public health).

Another proposition implied in this framework is that persons with mental illness are in favor of and demand more holistic, person-centered, recovery-oriented, strengths-based and culturally sensitive health and human care beyond illness-focused care. Integrating humanistic leisure-based programs into health care systems would give attention to the wholeness of the individual and her/his life, in which personal and social behavior (including leisure behavior) and cultural and environmental factors influence each other. The quality and accessibility of community health care systems are an important factor for the lives of people with mental illness because the ability of those systems to adequately meet the unique needs of persons with mental illness is a critical concern for their health and life quality.

This paper has presented a heuristic conceptual framework in which the centrality of leisure engagements from a broader and more balanced experience- and meaning-oriented perspective (than simply behavioral) is viewed as a proactive, strengths-based agent and context for active living to facilitate recovery and health/life-quality enhancement. Emphasized in the framework include the functions of enjoyable and meaningful leisure not only to promote personal identity and spirituality, positive emotions, harmony and social connections, effective coping and healing functions, human development, and physical and mental health, but also the effects of these interrelated elements on promoting more enjoyable and meaningful leisure in a reciprocal way for persons with mental illness. This reciprocal transaction can, however, be both positive and negative. That is, negative discretionary time behaviors (e.g. deviant leisure; Rojek, 1999 ) can be detrimental to individuals just as environmental factors can support or impede meaningful leisure experiences.

Also, by adopting a holistic and ecological perspective, this framework stresses the significance of social and environmental factors including the need to transform neighborhoods and communities to be more resourceful and active-living friendly. From a global international perspective, however, the impact of cultural/cross-cultural factors should not be ignored as these are closely interconnected with neighborhood and community factors, health care systems and the other social and environmental factors (e.g. socio-economic).