1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

How to Write a Philosophical Essay

Authors: The Editors of 1000-Word Philosophy [1] Category: Student Resources Word Count: 998

If you want to convince someone of a philosophical thesis, such as that God exists , that abortion is morally acceptable , or that we have free will , you can write a philosophy essay. [2]

Philosophy essays are different from essays in many other fields, but with planning and practice, anyone can write a good one. This essay provides some basic instructions. [3]

1. Planning

Typically, your purpose in writing an essay will be to argue for a certain thesis, i.e., to support a conclusion about a philosophical claim, argument, or theory. [4] You may also be asked to carefully explain someone else’s essay or argument. [5]

To begin, select a topic. Most instructors will be happy to discuss your topic with you before you start writing. Sometimes instructors give specific prompts with topics to choose from.

It’s generally best to select a topic that you’re interested in; you’ll put more energy into writing it. Your topic will determine what kind of research or preparation you need to do before writing, although in undergraduate philosophy courses, you usually don’t need to do outside research. [6]

Essays that defend or attack entire theories tend to be longer, and are more difficult to write convincingly, than essays that defend or attack particular arguments or objections: narrower is usually better than broader.

After selecting a topic, complete these steps:

- Ensure that you understand the relevant issues and arguments. Usually, it’s enough to carefully read and take notes on the assigned readings on your essay’s topic.

- Choose an initial thesis. Generally, you should choose a thesis that’s interesting, but not extremely controversial. [7] You don’t have to choose a thesis that you agree with, but it can help. (As you plan and write, you may decide to revise your thesis. This may require revising the rest of your essay, but sometimes that’s necessary, if you realize you want to defend a different thesis than the one you initially chose.)

- Ensure that your thesis is a philosophical thesis. Natural-scientific or social-scientific claims, such as that global warming is occurring or that people like to hang out with their friends , are not philosophical theses. [8] Philosophical theses are typically defended using careful reasoning, and not primarily by citing scientific observations.

Instructors will usually not ask you to come up with some argument that no philosopher has discovered before. But if your essay ignores what the assigned readings say, that suggests that you haven’t learned from those readings.

2. Structure

Develop an outline, rather than immediately launching into writing the whole essay; this helps with organizing the sections of your essay.

Your structure will probably look something like the following, but follow your assignment’s directions carefully. [9]

2.1. Introduction and Thesis

Write a short introductory paragraph that includes your thesis statement (e.g., “I will argue that eating meat is morally wrong”). The thesis statement is not a preview nor a plan; it’s not “I will consider whether eating meat is morally wrong.”

If your thesis statement is difficult to condense into one sentence, then it’s likely that you’re trying to argue for more than one thesis. [10]

2.2. Arguments

Include at least one paragraph that presents and explains an argument. It should be totally clear what reasons or evidence you’re offering to support your thesis.

In most essays for philosophy courses, you only need one central argument for your thesis. It’s better to present one argument and defend it well than present many arguments in superficial and incomplete ways.

2.3. Objection

Unless the essay must be extremely short, raise an objection to your argument. [11] Be clear exactly which part of the other argument (a premise, or the form) is being questioned or denied and why. [12]

It’s usually best to choose either one of the most common or one of the best objections. Imagine what a smart person who disagreed with you would say in response to your arguments, and respond to them.

Offer your own reply to any objections you considered. If you don’t have a convincing reply to the objection, you might want to go back and change your thesis to something more defensible.

2.5. Additional Objections and Replies

If you have space, you might consider and respond to the second-best or second-most-common objection to your argument, and so on.

2.6. Conclusion

To conclude, offer a paragraph summarizing what you did. Don’t include any new or controversial claims here, and don’t claim that you did more than you actually accomplished. There should be no surprises at the end of a philosophy essay.

Make your writing extremely clear and straightforward. Use simple sentences and don’t worry if they seem boring: this improves readability. [13] Every sentence should contribute in an obvious way towards supporting your thesis. If a claim might be confusing, state it in more than one way and then choose the best version.

To check for readability, you might read the essay aloud to an audience. Don’t try to make your writing entertaining: in philosophy, clear arguments are fun in themselves.

Concerning objections, treat those who disagree with you charitably. Make it seem as if you think they’re smart, careful, and nice, which is why you are responding to them.

Your readers, if they’re typical philosophers, will be looking for any possible way to object to what you say. Try to make your arguments “airtight.”

4. Citations

If your instructor tells you to use a certain citation style, use it. No citation style is universally accepted in philosophy. [14]

You usually don’t need to directly quote anyone. [15] You can paraphrase other authors; where you do, cite them.

Don’t plagiarize . [16] Most institutions impose severe penalties for academic dishonesty.

5. Conclusion

A well-written philosophy essay can help people gain a new perspective on some important issue; it might even change their minds. [17] And engaging in the process of writing a philosophical essay is one of the best ways to develop, understand, test, and sometimes change, your own philosophical views. They are well worth the time and effort.

[1] Primary author: Thomas Metcalf. Contributing authors: Chelsea Haramia, Dan Lowe, Nathan Nobis, Kristin Seemuth Whaley.

[2] You can also do some kind of oral presentation, either “live” in person or recorded on video. An effective presentation, however, requires the type of planning and preparation that’s needed to develop an effective philosophy paper: indeed, you may have to first write a paper and then use it as something like a script for your presentation. Some parts of the paper, e.g., section headings, statements of arguments, key quotes, and so on, you may want to use as visual aids in your presentation to help your audience better follow along and understand.

[3] Many of these recommendations are, however, based on the material in Horban (1993), Huemer (n.d.), Pryor (n.d.), and Rippon (2008). There is very little published research to cite about the claims in this essay, because these claims are typically justified by instructors’ experience, not, say, controlled experiments on different approaches to teaching philosophical writing. Therefore, the guidance offered here has been vetted by many professional philosophers with a collective hundreds of hours of undergraduate teaching experience and further collective hundreds of hours of taking philosophy courses. The editors of 1000-Word Philosophy also collectively have thousands of hours of experience in writing philosophy essays.

[4] For more about the areas of philosophy, see What is Philosophy? by Thomas Metcalf.

[5] For an explanation of what is meant by an “argument” in philosophy, see Arguments: Why Do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf.

[6] Outside research is sometimes discouraged, and even prohibited, for philosophy papers in introductory courses because a common goal of a philosophy paper is not to report on a number of views on a philosophical issue—so philosophy papers usually are not “research reports”—but to rather engage a specific argument or claim or theory, in a more narrow and focused way, and show that you understand the issue and have engaged in critically. If a paper engages in too much reporting of outside research, that can get in the way of this critical evaluation task.

[7] There are two reasons to avoid extremely controversial theses. First, such theses are usually more difficult to defend adequately. Second, you might offend your instructor, who might (fairly or not) give you a worse grade. So, for example, you might argue that abortion is usually permissible, or usually wrong, but you probably shouldn’t argue that anyone who has ever said the word ‘abortion’ should be tortured to death, and you probably shouldn’t argue that anyone who’s ever pregnant should immediately be forced to abort the pregnancy, because both of these claims are extremely implausible and so it’s very unlikely that good arguments could be developed for them. But theses that are controversial without being implausible can be interesting for both you and the instructor, depending on how you develop and defend your argument or arguments for that thesis.

[8] Whether a thesis is philosophical mostly depends on whether it is a lot like theses that have been defended in important works of philosophy. That means it would be a thesis about metaphysics, epistemology, value theory, logic, history of philosophy, or something therein. For more information, see Philosophy and Its Contrast with Science and What is Philosophy? both by Thomas Metcalf.

[9] Also, read the grading rubric, if it’s available. If your course uses an online learning environment, such as Canvas, Moodle, or Schoology, then the rubric will often be visible as attached to the assignment itself. The rubric is a breakdown of the different requirements of the essay and how each is weighted and evaluated by the instructor. So, for example, if some requirement has a relatively high weight, you should put more effort into doing a good job. Similarly, some requirement might explicitly mention some step for the assignment that you need to complete in order to get full credit.

[10] In some academic fields, a “thesis” or “thesis statement” is considered both your conclusion and a statement of the basic support you will give for that conclusion. In philosophy, your thesis is usually just that conclusion: e..g, “Eating meat is wrong,” “God exists,” “Nobody has free will,” and so on: the support given for that conclusion is the support for your thesis.

[11] To be especially clear, this should be an objection to the argument given for your thesis or conclusion, not an objection to your thesis or conclusion itself. This is because you don’t want to give an argument and then have an objection that does not engage that argument, but instead engages something else, since that won’t help your reader or audience better understand and evaluate that argument.

[12] For more information about premises, forms, and objections, see Arguments: Why do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf.

[13] For a philosophical argument in favor of clear philosophical writing, and guidance on producing such writing, see Fischer and Nobis (2019).

[14] The most common styles in philosophy are APA (Purdue Online Writing Lab, n.d.a) and Chicago (Purdue Online Writing Lab, n.d.b.).

[15] You might choose to directly quote someone when it’s very important that the reader know that the quoted author actually said what you claim they said. For example, if you’re discussing some author who made some startling claim, you can directly quote them to show that they really said that. You might also directly quote someone when they presented some information or argument in a very concise, well-stated way, such that paraphrasing it would take up more space than simply quoting them would.

[16] Plagiarism, in general, occurs when someone submits written or spoken work that is largely copied, in style, substance, or both, from some other author’s work, and does not attribute it to that author. However, your institution or instructor may define “plagiarism” somewhat differently, so you should check with their definitions. When in doubt, check with your instructor first.

[17] These are instructions for relatively short, introductory-level philosophy essays. For more guidance, there are many useful philosophy-writing guides online to consult, e.g.: Horban (1993); Huemer (n.d.); Pryor (n.d.); Rippon (2008); Weinberg (2019).

Fischer, Bob and Nobis, Nathan. (2019, June 4). Why writing better will make you a better person. The Chronicle of Higher Education .

Horban, Peter. (1993). Writing a philosophy paper. Simon Fraser University Department of Philosophy .

Huemer, Michael. (N.d.). A guide to writing. Owl232.net .

Pryor, Jim. (N.d.). Guidelines on writing a philosophy paper. Jimpryor.net .

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (N.d.a.). General format. Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (N.d.b.). General format. Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Rippon, Simon. (2008). A brief guide to writing the philosophy paper. Harvard College Writing Center .

Weinberg, Justin. (2019, January 15). How to write a philosophy paper: Online guides. Daily Nous .

Related Essays

Arguments: Why do You Believe What You Believe? by Thomas Metcalf

Philosophy and its Contrast with Science by Thomas Metcalf

What is Philosophy? By Thomas Metcalf

Translation

Korean , Turkish

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com .

Share this:.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- BSA Prize Essays

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with BJA?

- About The British Journal of Aesthetics

- About the British Society of Aesthetics

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Philosophical Perspectives on Ruins, Monuments and Memorials

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sanna Lehtinen, Philosophical Perspectives on Ruins, Monuments and Memorials, The British Journal of Aesthetics , Volume 61, Issue 4, October 2021, Pages 596–599, https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayaa040

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This collection of twenty-three essays focuses on the question of what types of traces humans leave and have left behind over generations and what to think of them from the perspective of philosophical knowledge. Overarching themes in the book are the affective engagements through grief and remembrance, as Deborah Knight aptly elaborates in her contribution (p. 45). It seems that emotions such as grief are not exclusive to humans, but the act of creating and dedicating places and objects for remembrance seems to be. Memorials and monuments are defined by the intentional gesture of their original dedication. Ruins, on the other hand, can be preserved intentionally, even in cases in which their present state is the result of an unintentional process (p. 109). Ruins of war are something of an exception here, as they are a reminder of the destructive powers unleashed in conflict situations and cultural heritage has become increasingly the deliberately chosen target of destruction.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2842

- Print ISSN 0007-0904

- Copyright © 2024 British Society of Aesthetics

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

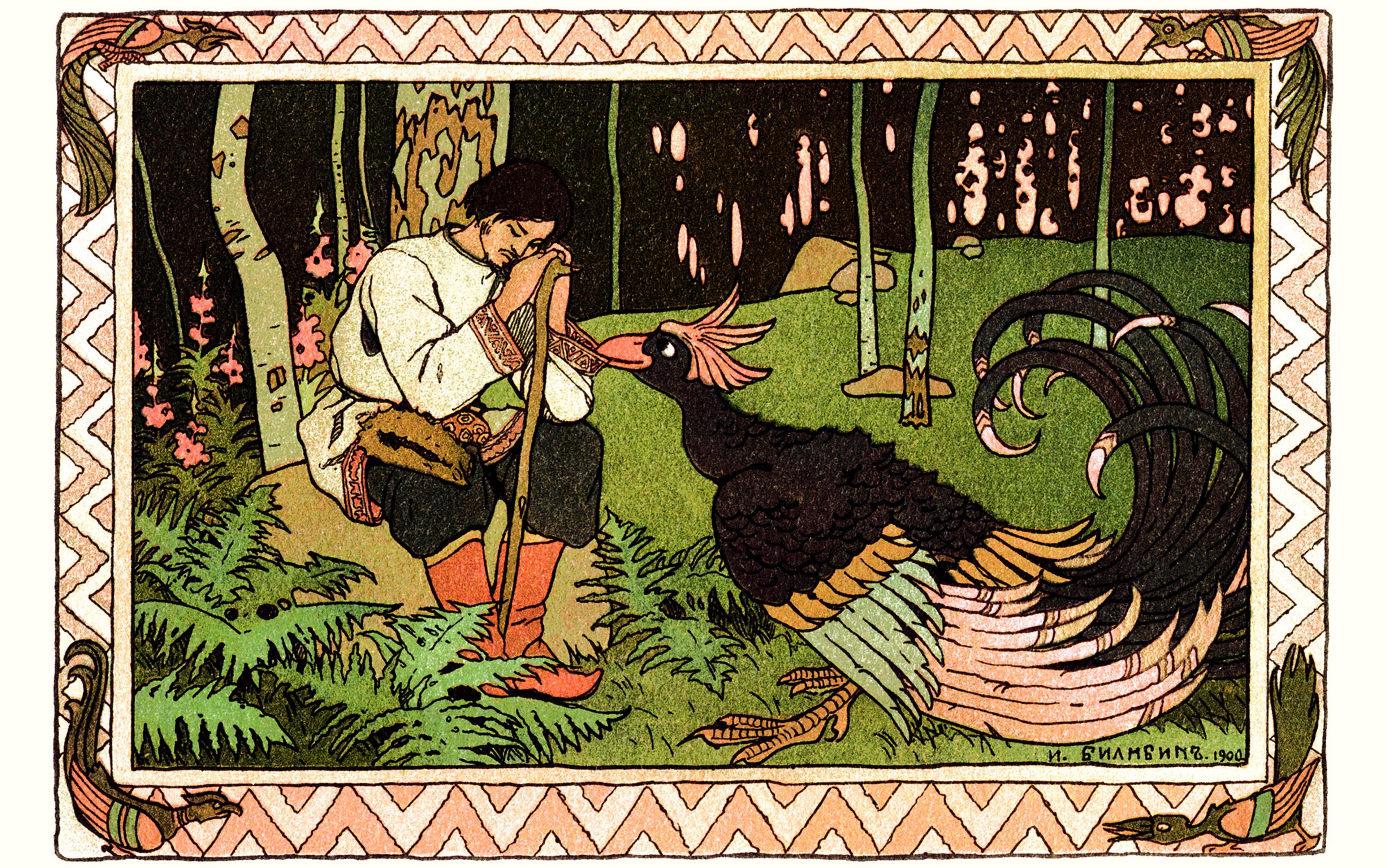

An illustration from Russian Wonder Tales (1912) by Poet Wheeler; illustrated by Ivan Bilibin. Photo by Getty

Folklore is philosophy

Both folktales and formal philosophy unsettle us into thinking anew about our cherished values and views of the world.

by Abigail Tulenko + BIO

The Hungarian folktale Pretty Maid Ibronka terrified and tantalised me as a child. In the story, the young Ibronka must tie herself to the devil with string in order to discover important truths. These days, as a PhD student in philosophy, I sometimes worry I’ve done the same. I still believe in philosophy’s capacity to seek truth, but I’m conscious that I’ve tethered myself to an academic heritage plagued by formidable demons.

The demons of academic philosophy come in familiar guises: exclusivity, hegemony and investment in the myth of individual genius. As the ethicist Jill Hernandez notes , philosophy has been slower to change than many of its sister disciplines in the humanities: ‘It may be a surprise to many … given that theology and, certainly, religious studies tend to be inclusive, but philosophy is mostly resistant toward including diverse voices.’ Simultaneously, philosophy has grown increasingly specialised due to the pressures of professionalisation. Academics zero in on narrower and narrower topics in order to establish unique niches and, in the process, what was once a discipline that sought answers to humanity’s most fundamental questions becomes a jargon-riddled puzzle for a narrow group of insiders.

In recent years, ‘canon-expansion’ has been a hot-button topic, as philosophers increasingly find the exclusivity of the field antithetical to its universal aspirations. As Jay Garfield remarks, it is as irrational ‘to ignore everything not written in the Eurosphere’ as it would be to ‘only read philosophy published on Tuesdays.’ And yet, academic philosophy largely has done just that. It is only in the past few decades that the mainstream has begun to engage seriously with the work of women and non-Western thinkers. Often, this endeavour involves looking beyond the confines of what, historically, has been called ‘philosophy’.

Expanding the canon generally isn’t so simple as resurfacing a ‘standard’ philosophical treatise in the style of white male contemporaries that happens to have been written by someone outside this demographic. Sometimes this does happen, as in the case of Margaret Cavendish (1623-73) whose work has attracted increased recognition in recent years. But Cavendish was the Duchess of Newcastle, a royalist whose political theory criticises social mobility as a threat to social order. She had access to instruction that was highly unusual for women outside her background, which lends her work a ‘standard’ style and structure. To find voices beyond this elite, we often have to look beyond this style and structure.

Texts formerly classified as squarely theological have been among the first to attract significant renewed interest. Female Catholic writers such as Teresa of Ávila or Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, whose work had been largely ignored outside theological circles, are now being re- examined through a philosophical lens. Likewise, philosophy departments are gradually including more work by Buddhist philosophers such as Dignāga and Ratnakīrti, whose epistemological contributions have been of especial recent interest . Such thinkers may now sit on syllabi alongside Augustine or Aquinas who, despite their theological bent, have long been considered ‘worthy’ of philosophical engagement.

On the topic of ‘worthiness’, I am wary of using the term ‘philosophy’ as an honorific. It is crucial that our interest in expanding the canon does not involve the implication that the ‘philosophical’ confers a degree of rigour over the theological, literary, etc. To do so would be to engage in a myopic and uninteresting debate over academic borders. My motivating question is not what the label of ‘philosophy’ can confer upon these texts, but what these texts can bring to philosophy. If philosophy seeks insight into the nature of such universal topics as reality, morality, art and knowledge, it must seek input from those beyond a narrow few. Engaging with theology is a great start, but these authors still largely represent an elite literate demographic, and raise many of the same concerns regarding a hegemonic, exclusive and individualistic bent.

As Hernandez quips: ‘[W]e know white, Western men have not cornered the market on deeply human, philosophical questions.’ And furthermore, ‘we also know, prudentially, that philosophy as a discipline needs to (and must) undergo significant navel-gazing to survive … in an ever-increasingly difficult time for homogenous, exclusive academic disciplines.’ In light of our aforementioned demons, it appears that philosophy is in urgent need of an exorcism.

I propose that one avenue forward is to travel backward into childhood – to stories like Ibronka’s. Folklore is an overlooked repository of philosophical thinking from voices outside the traditional canon. As such, it provides a model for new approaches that are directly responsive to the problems facing academic philosophy today. If, like Ibronka, we find ourselves tied to the devil, one way to disentangle ourselves may be to spin a tale.

Folklore originated and developed orally. It has long flourished beyond the elite, largely male, literate classes. Anyone with a story to tell and a friend, child or grandchild to listen, can originate a folktale. At the risk of stating the obvious, the ‘folk’ are the heart of folklore. Women, in particular, have historically been folklore’s primary originators and preservers. In From the Beast to the Blonde (1995), the historian Marina Warner writes that ‘the predominant pattern reveals older women of a lower status handing on the material to younger people’.

Folklore has existed in some form in every culture and, in each, it has brought underrepresented groups to the fore. As we look to expand the canon, folklore is a rich source of thought on topics of philosophic interest with the potential to uplift a wide range of voices who have thus far been largely overlooked.

Folktales puzzle and surprise and haunt. They make us ask ‘Why?’ And they invite us to imagine new ways to respond

In his wry poem ‘The Conundrum of the Workshops’ (1890), Rudyard Kipling describes Adam’s first sketch scratched in the dirt of Eden with a stick:

… [It] was joy to his mighty heart, Till the Devil whispered behind the leaves: ‘It’s pretty, but is it Art?’

And so we may ask: folklore may be inclusive, but is it philosophy?

To answer that question, one would need at least a loose definition of philosophy. This is daunting to provide but, if pressed, I’d turn to Aristotle, whose Metaphysics offers a hint: ‘it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin, and at first began, to philosophise.’ In my view, philosophy is a mode of wondrous engagement, a practice that can be exercised in academic papers, in theological texts, in stories, in prayer, in dinner-table conversations, in silent reflection, and in action. It is this sense of wonder that draws us to penetrate beyond face-value appearances and look at reality anew.

Given this lens, it is unsurprising that one solution to philosophy’s crisis might be found in a childhood pastime. In childhood, we literally see the world with new eyes; here, wonder is most keenly felt. We’ve all heard a child ask ‘Why?’ and realised not only that we don’t know the answer, but that we’d forgotten how miraculously puzzling the question was to begin with. Wonder and folktales are likewise linked. Wundermärchen – the original German word for fairytale – literally translates to ‘wonder tale’. Perhaps this is why children love folktales. In most cultures, folktales predate broad social distinctions between adult and children’s entertainment. But as other flashier diversions have largely overtaken the adult sphere, folktales have maintained their spell over children. They speak the child’s language. They puzzle and surprise and haunt. They make us ask ‘Why?’ And they invite us to imagine new ways to respond.

Aristotle’s wonder-based view of philosophy hasn’t been accepted by all. The late Harry Frankfurt rejected this analysis of what makes a question philosophical, countering in The Reasons of Love (2004):

It is hardly appropriate to characterise these things merely as puzzling. They are startling. They are marvels. The response they inspired must have been deeper, and more unsettling, than simply – as Aristotle puts it – a ‘wondering that the matter is so.’ It must have been resonant with feelings of mystery, of the uncanny, of awe.

But wonder, fear and awe are old friends. Like any Catholic schoolchild, I learned that ‘fear of God’ was just another name for ‘wonder and awe’. It seems that folklore and philosophy meet at this intersection, where wonder and fear converge into something both unsettling and marvellous. The folklorist Maria Tatar writes that, in the world of the folktale, ‘anything can happen, and what happens is often so startling … that it often produces a jolt.’ Folklore and philosophy are both in the business of startling us. Philosophy demands that we confront humanity’s deepest anxieties and longings. Whether we disguise them with phis and psis , it is deeply concerned with our shudders and sighs. And folklore, with its forests and phantoms, is perhaps the largest-scale historical inventory of these fears.

The folklorist Reet Hiiemäe goes as far as to argue it is ‘human fear’ that ‘induced the emergence and formation of folkloric phenomena’. Folklore is an imaginative attempt to make sense of the inexplicable. By tuning into what frightens us, we learn who we are. And if we want to find out what frightens us, the Black Forest is the first place we should look.

P hilosophy and folklore both elicit this sense of wondrous fear, startling awe. They also share a dual aim, well articulated by Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment (1976). For him, the purpose of folklore is to help us ‘live not just moment to moment, but in true consciousness of our existence.’ Here, as in philosophy, there is the search for the truth, which is to meaningfully attend to the structures of reality we so often take for granted, to perceive the world as more than mere scenery.

Second, there is the aim of a life well lived, the desire that our intellectual enquiry serve our lived experience, that we live and breathe our philosophy as well as contemplate it. The most obvious philosophical application of folklore is to ethics. Most of us are familiar with the parting moral lesson found at the end of familiar childhood tales. Warner argues that one of the most valuable aspects of the medium is its centring of marginalised voices in moral debates. She writes that ‘alternative ways of sifting right and wrong require different guides, ones perhaps discredited or neglected.’ If indeed philosophy is in crisis in part because of a narrowly circumscribed demographic of ‘guides’, folklore is a rich place to look for new ones. Bettelheim also suggests that folktales are normatively laden at their most fundamental level:

Tolkien addressing himself to the question of ‘Is it true?’ remarks that ‘It is not one to be rashly or idly answered.’ He adds that of much more real concern to the child is the question: ‘“Was he good? Was he wicked?” That is, [the child] is more concerned to get the Right side and the Wrong side clear.’

Before a child can come to grips with reality, he must have some frame of reference to evaluate it. When he asks whether a story is true, he wants to know whether the story contributes something of importance to his understanding, and whether it has something significant to tell him in regard to his greatest concerns.

Combing through folklore, it is easy to find stories that map well on to our contemporary concerns – many even mirror the structure of core ethical thought-experiments. For instance, in the traditional Russian tale Ilya Muromets and the Dragon, the hero must choose between aiding a king in a distant land whose kingdom is plagued by dragons, and returning to serve his home nation, which is in less dire need. In this tale, themes of partiality, community and nationalism arise. Does great need override one’s partiality toward one’s own family, nation, community? Parallels can be seen in many well-known thought-experiments in contemporary ethics. Whether one is jumping off a pier to save a drowning woman, steering a trolley, or ruining their new shoes in a pond to save a child, philosophers have long been concerned with whether and how our obligations to the familiar and the strange diverge. When mutually exclusive, should one save the life of one’s friend or of a stranger?

Another potent example arises in the Haitian folktale Papa God and General Death. There is a wide ethical literature on the nature and value of death: Fred Feldman’s Confrontations with the Reaper (1992) provides a useful introduction to the many facets of the debate. Is death a great evil? Is it a form of injustice? This tale offers an argument in defence of death. Papa God claims that people love him better than Death because he gives them life, while Death only takes it away. To prove this is so, Papa God asks a local man for water. The man, upon hearing that He is God, refuses Him a drink. When questioned, the man explains that he prefers Death over God:

Because Death has no favourites. Rich, poor, young, old – they are all the same to him … Death takes from all the houses. But you, you give all the water to some people and leave me here with 10 miles to go on my donkey for just one drop.

This tale turns our assumptions on their head, vividly arguing against the common presupposition that death is a moral evil. In its universality, death is actually a form of justice in a way that life never can be.

I n many cultures, folklore has even greater ethical import. For instance, the scholars Oluwole Coker and Adesina Coker argue that in Yoruba culture folklore plays a large role in ‘generating the laws governing intra and interpersonal relationships, communal cohesion, ethical regime and the justice system’. They term this relationship ‘folklaw’, explaining that folklore functions as a law-like ethical system that underlies social practices. They also emphasise that folklore is a ‘pathway for existential philosophy among the Yoruba’, as ethical quandaries are primarily explored through story. The Yoruba have long taken folklore seriously as a source of ethical reasoning.

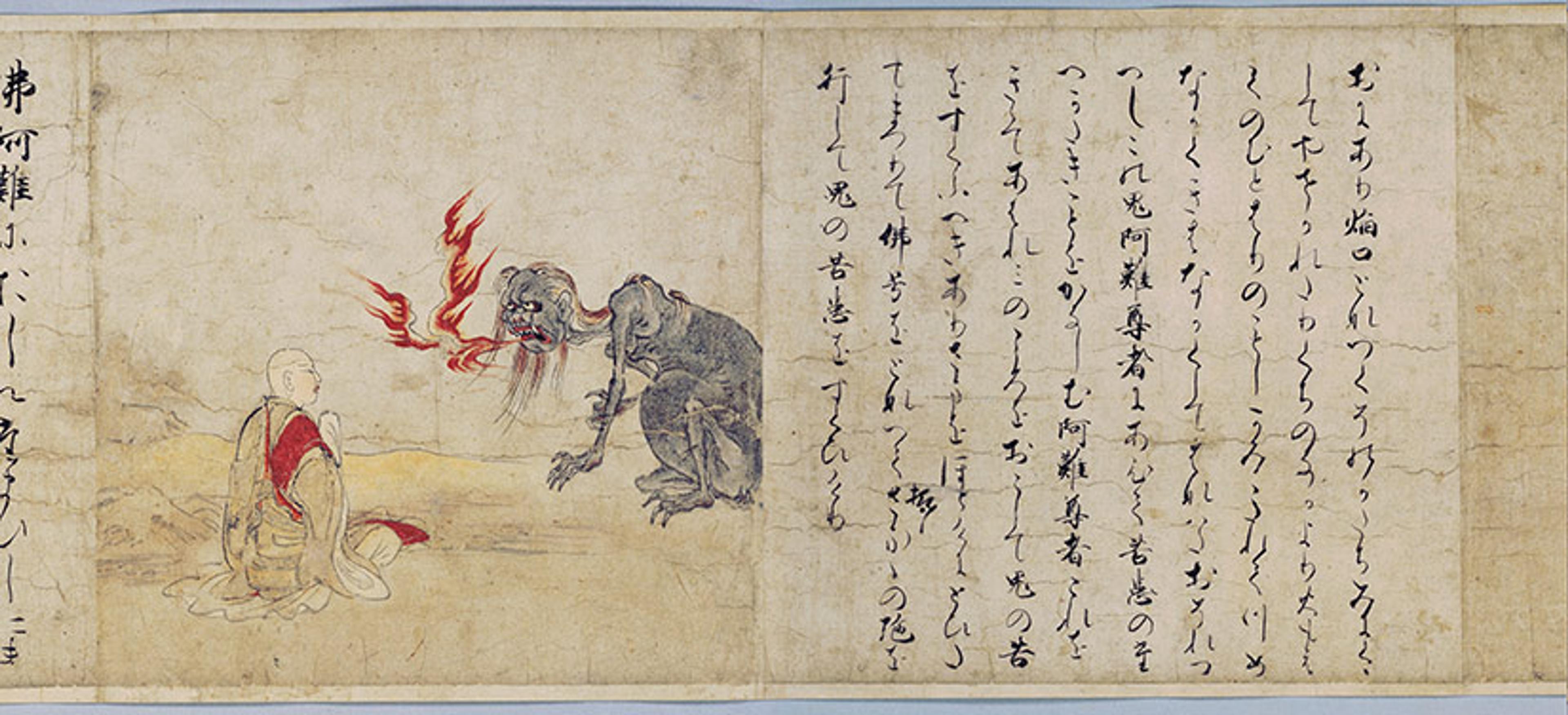

From Gaki-Zoshi (The Hungry Ghosts Scroll). Late 12th century. Courtesy the Kyoto Museum .

Beyond ethics, folklore touches all the branches of philosophy. With regard to its metaphysical import, Buddhist folklore provides a striking example. When dharma – roughly, the ultimate nature of reality – ‘is internalised, it is most naturally taught in the form of folk stories: the jataka tales in classical Buddhism, the koans in Zen,’ writes the Zen teacher Robert Aitken Roshi. The philosophers Jing Huang and Jonardon Ganeri offer a fascinating philosophical analysis of a Buddhist folktale seemingly dating back to the 3rd century BCE, which they’ve translated as ‘Is This Me?’ They argue that the tale constructs a similar metaphysical dilemma to Plutarch’s ‘ship of Theseus’ thought-experiment, prompting us to question the nature of personal identity:

The story tells the tale of a traveller’s unfortunate encounter with a pair of demons, one of whom is bearing a corpse. As the first demon tears off one of the man’s arms, the second demon takes an arm from the corpse and uses it as a transplant. This sport continues until the man’s whole body has been replaced, torn limb from limb, with the body-parts of the corpse. The man is given to ask himself: ‘What has become of me ?’

This tale tests our intuitions about the relationship between an entity’s parts and its whole. At what point does the mass of parts become the man? What sorts of material substitution entail an identity change?

Ancient tales have played a pivotal role in challenging previously unquestioned epistemic assumptions

The conclusion of the tale foregrounds an alternative approach to epistemology. Following the Buddhist Madhyamaka tradition of the ‘tetralemma’, the tale outlines four possible responses to the dilemma: is the replaced body the original man? 1) Yes it is the man. 2) No it is not the man. 3) It is both the man and not the man. 4) It is neither the man nor not the man. The tale progresses to reveal that each of these options leads to some absurdity. This functions as a reductio argument against the notion of personal identity altogether, suggesting that the concept was, from the start, empty or incorrectly defined. Other tales affirm the more radical notion that it is coherent to reject or accept all four responses simultaneously.

This heterodox approach to epistemology inspired the logician Graham Priest’s notion of ‘dialetheism’, which posits the coherence of ‘dialetheias’ – joint propositions that include a statement and its negation. The development of dialetheism provides an example of a case where ancient tales have already played a pivotal role in challenging previously unquestioned epistemic assumptions. What other philosophic insights might lie buried in folklore? What new questions might they ask, and how might they widen our understanding of the scope of answers available?

Then there is the question of methodology: when faced with a folktale, how would a sympathetic philosopher proceed? The tales generally aren’t going to give us arguments neatly pre-packaged in premise-conclusion form. We will need to put in the interpretive work to understand the contextual and stylistic features necessary to extract philosophic insights. There will be interpretive, literary and anthropological facts to consider. Perhaps philosophers are ill-equipped to do this work alone – and all the better! Cross-disciplinary engagement broadens our enquiry and leaves all involved enriched. How wonderful would it be if departments collaborated more often, if we saw papers co-published by folklorists and metaphysicians, if our search for truth transcended bureaucratic academic divisions and led us through the winding paths of stories, paths we shared in childhood, but have long since forgotten.

But before we sharpen our pencils to hunt for proofs, I would invite my fellow philosophers to be open to alternative approaches to engaging with philosophic ideas. Don’t get me wrong, I love premise-conclusion form as much as the next girl (and probably far more, unless the next girl is also a graduate student in metaphysics). But it would be patently irrational to assume that the whole of philosophic understanding is recorded in that form. (And we lovers of proofs famously detest irrationality.)

In folktales, we may not always find arguments, at least as typically construed. This is not a sign of philosophical impotence. The European bias of the canon tends to privilege a particular argumentative structure. However, stories are not new to philosophy: Plato, Friedrich Nietzsche and Søren Kierkegaard were all vivid storytellers. Today, even the most methodologically rigid analytic philosophy is not immune to the lure of narrative. Just look at Bettelheim’s description of the function of fairy tales, which could be mistaken for a description of the contemporary thought-experiment:

It is characteristic of fairy tales to state an existential dilemma briefly and pointedly … [in order] to come to grips with the problem in its most essential form …

Storytelling is germane to the philosophic tradition, despite a general decline in recent times. (‘Recent’ in the long history of philosophy can mean a few centuries.) But the historical precedent for narrative in philosophy isn’t its only justification. Where the structure of folklore diverges from the philosophic tradition is perhaps where its impact can be most useful. Folklore is full of magical metamorphosis. It casts its spell, and I think we ought to let it. The most powerful canon-expansion will move beyond mere addition to methodological transformation.

F olklore provides a new model of enquiry that has the power to transform the discipline in exciting ways, re-enlivening it from the inside. What could philosophy look like beyond the assumptions of contemporary academia? How can folklore shed light on alternative ways of reasoning, raise new puzzles, and expand the range of answers in view?

Ludwig Edelstein, a scholar of Plato, argued that storytelling plays an important explanatory role: through stories, we ‘counteract sorcery by sorcery’. He contends that the human search for meaning is best realised when we engage both our rational and our emotive natures. Since ‘both these parts of the human soul must be equally tended by the philosopher’, stories are a valuable tool to impart ideas with maximal impact.

This value is instrumental as we seek to broaden philosophy’s reach beyond a narrow specialised few. Folklore is a medium of expansive inclusion – it transcends class and educational boundaries. As the fiction writer Karel Čapek noted: ‘a true folk fairy tale does not originate in being taken down by the collector of folklore, but in being told by a grandmother to her grandchildren’. It is intended for wide engagement, and its familiar and entertaining structure makes complex ideas accessible to a range of audiences throughout different disciplines, and beyond academe.

Another notable feature of folklore is its emphasis on collectivity. For most, the word ‘philosophy’ conjures a lineage of geniuses: your Aristotles, your Sartres, your Kants. The discipline has valorised individuals atomistically, framing their revolutionary contributions in a vacuum. In recent years, many have cast aspersions on this narrative. The sociologist Sal Restivo declares : ‘[I]f you give me a genius, I will give you a social network.’ Increasingly, there is a trend toward recognising progress as a matter of collaboration rather than atomistic ownership.

Storytelling engages with the messy and the real in a way that the pristine structures of philosophy struggle to do

Folklore has a long tradition in this spirit. In Sitting at the Feet of the Past (1992), a collection of essays on the North American folktale, Steve Sanfield writes: ‘Nobody owns these stories … They change each time they’re told.’ Tales are inherently communal, having no single author. Listeners alter the stories, misremember them, embellish them, and change their meaning with each retelling. In this manner, it is a mode of thinking collectively and through time, a collaborative enquiry that persists through centuries.

The generational model of folklore also contrasts with academic philosophy’s long-lamented blindness to its own historicity, to context and to contingency. As the literary scholar Karl Kroeber observed in Retelling/Rereading: The Fate of Storytelling in Modern Times (1992):

[A]ll significant narratives are retold and are meant to be retold – even though every retelling is a making anew. Story can thus preserve ideas, beliefs, and convictions without permitting them to harden into abstract dogma. Narrative allows us to test our ethical principles in our imaginations where we can engage them in the uncertainties and confusion of contingent circumstance.

Folklore is openly historical, and openly in flux. Tales evolve with the contributions of successive tellers, and yet, in what persists, we are able to witness thought processes that approach timeless resonance. This method offers advantages over the European philosophical model, which can obscure the wider history of ideas in its insistence on abstracted and individual pursuit of the universal. Storytelling is unafraid to engage with the contextual, the messy and the specificity of the real in a way that the pristine structures of philosophy struggle to do. As such, it provides a more thoroughly examined path to what might be called the universal. Folklore is both a reflection of the Now from which it is being told, and a record of what persists throughout aeons of successive nows. To borrow Kroeber’s metaphor, folklore preserves ideas softly . It’s putting flowers in a vase rather than drying them – watery narrative is always moving, always in flux, so the ideas stay green and do not become brittle.

The ending of Pretty Maid Ibronka has always moved me. She stands at the village graveyard, a young girl facing down the devil in the guise of a sophisticated man. One expects her to scream, to run or to fight. Instead, she tells him a story, one that contains the truth. She begins at the start of the tale itself, hijacking the role of narrator, tying the story into a loop. It is only when she does so that the devil is vanquished, and his victim’s lives restored.

Food and drink

The fermented crescent

Ancient Mesopotamians had a profound love of beer: a beverage they found celebratory, intoxicating and strangely erotic

Tate Paulette

Philosophy of science

Life makes mistakes

Hens try to hatch golf balls, whales get beached. Getting things wrong seems to play a fundamental role in life on Earth

David S Oderberg

Sex and sexuality

Sex and death

Our culture works hard to keep sex and death separate but recharging the libido might provide the release that grief needs

Cody Delistraty

Politics and government

The spectre of insecurity

Liberals have forgotten that in order for our lives not to be nasty, brutish and short, we need stability. Enter Hobbes

Jennifer M Morton

The joy of clutter

The world sees Japan as a paragon of minimalism. But its hidden clutter culture shows that ‘more’ can be as magical as ‘less’

Anthropology

Witches around the world

The belief in witches is an almost universal feature of human societies. What does it reveal about our deepest fears?

Gregory Forth

How to Write a Philosophy Paper: Bridging Minds

Table of contents

- 1 What is a Philosophy Paper?

- 2.1 Philosophy Research Paper Introduction

- 2.2 Body Sections

- 2.3 Writing a Philosophy Paper Conclusion

- 3 Template for a Philosophy Essay Structure

- 4 How to Format a Philosophy Research Paper

- 5.1 Choose a Topic

- 5.2 Read the Material and Take Notes

- 5.3 Think about Your Thesis

- 5.4 Make an Outline

- 5.5 Make a First Draft

- 5.6 Work on the Sections

- 5.7 Engage with Counterarguments

- 5.8 Don’t Niglet Citations

- 5.9 Check Formatting Guidelines.

- 5.10 Revise and Proofread

- 6 How to Select the Best Philosophy Essay Topic?

- 7.1 Argumentative Philosophy Essay Topics

- 7.2 Plato Essay Topics

- 7.3 Worldview Essay Topics

- 7.4 Transcendentalism Essay Topics

- 7.5 Practical Philosophy Essay Topics

- 7.6 Enlightenment Essay Topics

- 8 Let Your Philosophy Paper Shine

As a college student who has decided to take a philosophy course, you may be new to this science. A philosophy assignment may seem hard, and this subject is indeed pretty difficult. You read some text, but what you read is just one level of the text, as you need to think critically and analyze what the author is trying to get across. It also involves a lot of analytical and deep thinking. Thus, it is difficult to do an assignment unless you fully understand the text. Don’t freak out if you have little experience with this subject, as we have prepared a comprehensive guide on how to write a philosophy paper, from which you will know:

- The essence of philosophy paper, its structure and format

- Why it is important not to omit the outline stage

- Practical tips on writing a philosophy research paper.

What is a Philosophy Paper?

A philosophy research paper is an academic work that presents a comprehensive exploration of a specific philosophical question , topic, or thinker. It typically involves the analysis of arguments, the articulation of one’s own positions or perspectives, and the evaluation of philosophical texts and ideas. The primary objective of such a paper is to contribute to the understanding of philosophical issues by critically examining existing views, offering new interpretations, or developing novel arguments. The paper is characterized by rigorous logical reasoning, clear articulation of ideas, and grounding in relevant philosophical literature.

Drafting a philosophy essay begins with appreciating precisely what a philosophy research paper entails. It involves taking a definite position on a philosophical topic and defending that viewpoint with a logical, irrefutable claim. A good research essay generally uses rational arguments to lead readers down a path to a conclusive, hard-to-contradict resolution.

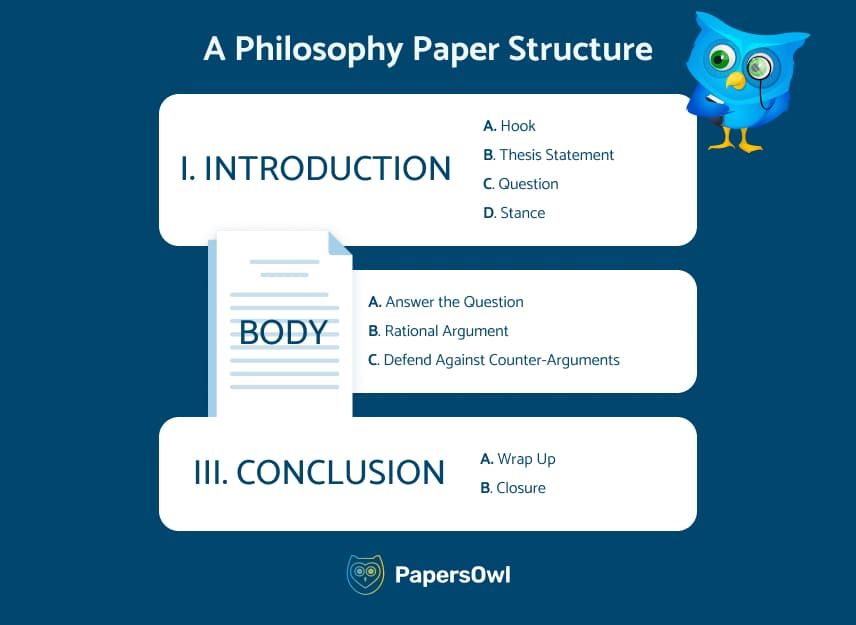

Philosophy Paper Outline Structure

Writing a quality philosophy paper means beginning with a first-rate outline. The best philosophy paper outline is straightforward in its intent, takes up a position, and is uncomplicated in its language. A proper outline makes drafting easier and less time-consuming. Moreover, philosophical writing with a clear-cut outline will lend assurance that your end result is condensed yet enlightening.

After determining a format, you are ready to begin writing out your philosophy paper outline. The first step in this process is to determine how to choose a topic for a paper. Great papers are those that the writer is most interested in. Once your topic has been chosen, your outline can be written with specific details and facts. Said specifics will take your introduction, body, and conclusion through an easy-to-follow guide.

Philosophy Research Paper Introduction

Your research essay should begin with a striking and attention-grabbing hook . It should identify your topic of focus in some way and ensure that readers have the desire to continue on. The hook is intended to smoothly transition to your thesis statement, which is the claim your thesis is venturing to prove. Your thesis statement should lead readers to the question of research – the distinct question that will be wholly explained in the body of writing. Finally, your introduction for the research paper will close with your stance on the question.

Body Sections

The body aspect of a philosophy thesis is considered the meat of any paper. It is hard unless you find someone to write my philosophy paper for me . This element is where most of the logic behind your stance is contained. Typically, bodies are made up of 3 sections, each explaining the explicit reasoning behind your position. For instance, the first chunk of the body will directly and logically answer the question posed.

In your second body section, use statements that argue why your position is correct. These statements should be informed, prudent, and concise in their reasoning, yet still presented without overly fancy lingo. The explanation of your argument should not be easily opposed. It should also be succinct and without fluff, insulating the explanatory material.

The third portion of the body section should defend your thesis against those that may have counterarguments. This will be the backbone of the essay – the portion that is too hard to refute. By ensuring that criticisms are properly and utterly denounced and the thesis is ratified, philosophical writing will begin to reach its end – the conclusion.

Writing a Philosophy Paper Conclusion

The conclusion is ultimately meant to tie the entire work together in a nice, coherent fashion. It should start with a brief rehash of the body section of your essay. Then, it will move into explaining the importance of the thesis and argument as a whole. Quality conclusions are ones that will offer a sense of closure.

Template for a Philosophy Essay Structure

A suggested template to help guide you when writing out a philosophy outline is as follows:

The use of the above outline template is sure to help with the overall drafting procedure of philosophical writing. Understanding the proper use of the outline is ideal for the best end product.

Putting an outline to use makes the process of writing a philosophy paper much more simple. By using an outline to navigate your thoughts as you write, your essay nearly composes itself. The addition of detail to an outline as it is written provides pronounced facts and a full outline. Take the outline chock full of thoughts and ideas, add words and transitions, and you have a complete paper.

How to Format a Philosophy Research Paper

Formatting a philosophy paper starts with choosing a citation style . The choice between APA, MLA, and Chicago styles simply lay out citations in contrasting manners for your philosophical writing. Each of these styles requires a differing method of citing sources and varying types of organization. Most commonly, philosophy research paper citations are done in MLA or Chicago. While both are accepted, it may be best to choose which your supervisor requires.

Luckily, you can APA research papers for sale and forget about this stress.

10 Steps to Write a Great Philosophy Paper Like a Pro

Learning how to write a philosophy research paper outline is a skill that can be carried over to numerous other subjects. While philosophical writing is a bit different than most other topics of discussion, the outline can be applied to others fairly easily. Proper utilization of outlines makes for a well-thought-out and structured thesis work that a writer can be proud of.

Choose a Topic

One of the primary steps is choosing a topic, and that is the first thing college students get stuck on. If you can not choose a topic you are interested in, talk to your university professor. You can also take a look at different lists of ideas on the Internet.

Read the Material and Take Notes

Read all materials carefully and take notes of important ideas. It is a good idea to read the material a couple of times as there will always be something you don’t notice at first. It is important to have a clear understanding of what you read to nail your assignment. If you feel like you don’t understand anything, then Google ‘ write my philosophy paper for me ’ and get help from real professionals.

Think about Your Thesis

Before you start writing, realize what you are going to show. Your work should have a strong thesis that states your position. The central component of the work is a clear thesis statement followed by supporting claims.

Make an Outline

An outline should include your ideas for the introduction, your thesis, main points, and conclusion. Having a philosophy paper outline before working on the assignment can help you stay focused and ensure you include all major points.

Make a First Draft

Don’t worry about perfection at this stage. Instead, focus on getting your ideas on paper. Following your outline, start building your arguments. Make sure to provide evidence or reasons for your claims.

Work on the Sections

Introduction: An introduction for a research paper is an essential part of any assignment because it gives your readers an overview of your work. It is your opportunity to grab their attention, so take this step seriously. Remember the thesis statement? You should present it here.

Main body: In this part, you need to present arguments and support your thesis. Start with providing a clear explanation of the philosopher’s ideas and move to the evaluation. Support your thesis by using examples.

Conclusion: A conclusion for any research paper is where you restate your central thesis. It should look like a mirror image of the introduction. Here you need to summarize the major points of your work.

Engage with Counterarguments

A good philosophy paper acknowledges opposing views. Make sure to address these counterarguments and provide reasons for why you believe your stance is more compelling.

Don’t Niglet Citations

Citations serve as a bridge. They link your ideas to the broader world of philosophical discourse, allowing readers to trace back your sources and delve deeper if they wish. Always remember, that citations are more than a mere formality. They correspond to specific ideas, arguments, or facts you present in your paper. This means every claim, idea, or quote you borrow from a philosopher needs to be clearly linked to its source. In this way, you will be sure that your work will be free of plagiarism .

Check Formatting Guidelines.

It’s also crucial to maintain consistency in your citation style. Whether you use APA, MLA, or Chicago, stick to one style throughout your paper.

Revise and Proofread

Once you finish your masterpiece, it is time to edit and proofread the research paper . We recommend you put your work aside for a few days to have a fresh perspective when start editing it.

How to Select the Best Philosophy Essay Topic?

First of all, we recommend deciding on a direction that interests you more. It can be a theoretical aspect, applicative use of philosophy or even the integration of this science with others – for example, ontology or metaphysics. After all, it is essential to reflect your thoughts correctly in writing for any direction. You will need to use writing tools for students to show your judgments accurately in the essay. Sometimes this can be a difficult task when the authors of the papers get into a so-called flow state.

Secondly, choosing a good topic that can be compared with the opinions of already-known thinkers is necessary for a deeper justification of your point of view. To do this, use the appropriate essay quotation format to make your paper easy to read. After all, while we are not recognized philosophers, proving our claims will be helpful to get the highest score.

If you still need to get philosophy essay ideas, continue reading this article. Here you will find 70 interesting topics that you can use as a topic for your essay or get inspired to create your own.

Easy Philosophy Paper Topics

Often we want to avoid reinventing the wheel. We are interested in writing an exciting but easy essay. So, if you were looking for simple philosophical essay topics, here is the list of the top 10 topics in philosophy for your paper:

- Human Responsibilities in Different World Religions: Why are They Distinct?

- Good and Evil: Do They Have Anything in Common? Will They Be Able to Insulate One without the Other?

- Advantages and Disadvantages of a Hedonistic Approach to Life

- Life after Death: Should We Endure the Circumstances of the X-axis for a Better Future on the Y-axis?

- Why Ancient People Asked Themselves the Same Questions as We Do: Isn’t Humanity Progressing?

- Do We Fulfill Our Moral Obligation to Parents by Helping Children?

- Three Features: Each from an Animal and an Angel. What is the Nature of Man?

- Is Genetic Engineering Ethical with Respect to the Laws of Nature?

- How Society Can Influence the Personal Choice of the Sense of Life for Each of Us

- Self-Determination of a Person & the Formation of our Microuniverse

Argumentative Philosophy Essay Topics

If you think more analytically, use it to your advantage. The argumentative type of philosophy essay is an unusual and exciting option for such papers since it requires strong thesis statement points. If you want to write exactly this sort of essay, these essay topics ideas will come in handy to decide on the topic of your work:

- Peaceful Protests/Desperate Battle: a Critical Analysis of the Philosophy of Resistance

- The Borderland Situation and Absurdity: Analytical Review.

- Explanation of the Path of any Subject to the Point of No Return. A Critical Analysis of “The Myth of Sisyphus” 1942.

- The Paradox of Absurdity and How to Find a Way Out of It: Follow the Rules or Set Yours

- Comparative Analysis of Forms of Globalization from the Point of View of Philosophy

- E. Leroy, P. Teilhard de Shader and Volodymyr Vernandskyi: Together About the Noosphere, Separately About its Functioning.

- Analysis of the Origins of the First Thinkers from the Point of View of Metaphysics.

- The Legal Aspect of Organ Cloning and Entire Human Cloning. Does it Make a Difference?

- Are People Obliged to Always Tell the Truth and Nothing But the Truth?

- Is Experience Acquired through Lived Years or Situations? Explanation of Each of the Parties.

Plato Essay Topics

Plato and Aristotle were the founders of philosophy in their classical sense. That is why writing an essay that will outline or refute Plato’s reasoning is a surefire option to impress your teacher and stand out from the rest of the group. If you still don’t know what to write about, below are the topics in the philosophy type of paper:

- Understanding a Being as a Multiplicity of Organic Elements According to Plato’s Postulates.

- Reflection of the Philosophy of Truth As an Idea: Plato’s Teaching

- Plato’s way of Familiarizing themself with the Truth through Memories

- Is It Possible to Trace the Influence of Socrates on Plato’s Philosophy: a Detailed Analysis

- Truth Exists, but It does not Exist until Being Developed – the Main Contradiction of Plato’s System of Philosophy Understanding

- “Phaedo”: Philosophy is the Science of Death.

- Plato’s Dialectic: Philosophy is the Cornice that Crowns All Our Knowledge

- Platonic Vision of Four Types of Dialectics as Four Modes of the Soul Activity

- A Move Against Democracy from the Platonic Postulates of Understanding the State and Society According to Personal Philosophy

- Plato and the “Ladder of Love” in the “Banquet”: Beautiful Bodies, Souls, Tempers and Sciences.

Worldview Essay Topics

Worldview and philosophy are similar concepts; they are rooted in the history of the human race. That is why this type of essay is interesting for both writing and reading. Choose your worldview essay topic from the options below to create your perfect piece of writing:

- Three-Aspect Structure of Worldview: Elements, Levels, Main Subsystems

- Mythological and Religious Types of Worldview: What do They Have in Common?

- Worldview as an Individual Prism of Multilevel Interaction Between Man and the World

- The Influence of Previous Generations on Modern Prejudices of our Outlook

- Ideological Form of Globalization. How does Social Media Affect It?

- The Noosphere as a Part of Countering Global Warming

- Modern Beauty Standards and the Bodily Phenomenon of Existence: What is the Connection between Them?

- Human Rights. Philosophy and Ethics

- Religious Beliefs as a Form of Philosophy Existence

- A Complex and Fragmented Approach to Studying the Worldview of Different Nations

Transcendentalism Essay Topics

Transcendentalism, as a new stage in the formation of philosophy, played a key role in its modern appearance. If you are more inclined towards more modernist lines of philosophy, these topics will suit you perfectly:

- Classical German Philosophy. Rational and Intelligent Thinking

- Subjectively Realistic Description of the Environment According to Categories of Philosophy

- The Influence of Transcendentalism on the Ongoing Development of Philosophy Accordingly to the Categories of Multiplicity and Necessity

- 10 Categories Denoting Deep Connections in being Relative to Transcendentalism: What Unites and Distinguishes Them

- Scientific Contemplation as a Mental Category through the Prism of the 20s Years of the 20th Century

- Life at the Intersection of the Past and the Future: Influence on Currents of American Transcendentalism Philosophy

- Modes of Perception of Time & Time as Duration: New ideas of Transcendentalists or Paraphrasing of Hegel’s Postulates?

- Ontological Doctrines and their Essential Characteristics: Henry David Thoreau

- Concepts of Understanding Space and their Qualitative Changes Relative to New Views on Philosophy

- Nature for Self-Sufficiency as the Main Myth of Philosophy Currents at the Beginning of the 20th Century

Practical Philosophy Essay Topics

The theory is great. However, any science’s practical and applied meaning is interesting for each of us. If you are interested in delving into the use of philosophy in modern society, these topics will not leave you indifferent:

- Everyday/Life Level of Philosophy

- Philosophy of Principles. What does It Mean to be Guided by a Certain Life Principle?

- Approach of Philosophy to the Life of Tibetan Monks – does It Correlate with Reality?

- Prejudice against Residents of Third World Countries: Reasons for Contempt for Their Mentality and Lifestyle

- Unpreparedness of College Teachers for Changes in the Education System: What are They Afraid of?

- Truth as the Last Instance of Communication with People. Is It Always Necessary?

- The Philosophy of Excessive Consumption in the USA. What Basis does it Have?

- Does the Concept of One’s Opinion Exist in the Era of Oversaturation of Information?

- The use of Ancient Greek Postulates in Philosophy Today – is the Appeal to Classical Canons Still Relevant?

- The Concept of Ethical and Moral Principles in the Era of Excessive Permissiveness.

Enlightenment Essay Topics

Enlightenment played a huge role in all sciences and spheres of human life. It’s a mind-blowing theme to write about. So, if you were looking for some ideas for your Enlightenment essay topic, we’ve prepared the best ones for you:

- Does the Urge to Study and Develop the Beautiful in Man Still Influence Modern Philosophy?

- Empiricism and Rationalism: Julien Aufre de Lametre’s Attempt to Unite Them

- The Concept of Atheistic Speech of Enlightenment: Religious Dogmatics Debunktion by Voltaire

- Voltaire: Ignorance, Fanaticism, Delusion and Lies Are Cultivated by Christianity

- The State as a Level of Inequality between the Rich and the Poor, According to Rousseau’s Views.

- The Immense Book of Nature as an Object of Knowledge According to Denis Diderot

- The Structure of Existence through Its Concepts: Elements, Substratum, Substance, Objective Reality beyond Human Consciousness and the Condition of Multiplicity.

- Concepts of Understanding Space and Time in Enlightenment Philosophy

- “Molecular Motion” by Paul Holbach: What is It?

- Social Life Based on the Principles of Reason and Justice – “About Reason” Andrian Helvetius

Let Your Philosophy Paper Shine

Good philosophy research paper writing requires some craft and care. Edit your work until it feels right, and make sure you are confident about your claims. If this science is just not your thing, or you struggle to understand it and doing assignments is sheer torture for you, then order a philosophical work crafted by real professionals! The best way to do your assignment is to leave it to experts and forget about your problems.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The Teacher Philosophical Heritage

2018, Kima0724.com

To philosophize is so essentially human- and in the sense to philosophize means living. -J. Pieper By: Kim B. Alcance (Group 1)

Related papers

Journal of Management Education, 2020

Teaching philosophy statements reflect our personal values, connect us to those with shared values in the larger teaching community, and inform our classroom practices. In this article, we explore the often-overlooked foundations of teaching philosophies, specifically philosophy and historical educational philosophies. We review three elements of pure philosophy and five seminal educational philosophies to help readers ground their personal philosophies in both a theoretical and historical context. We illustrate how core elements of one’s teaching philosophy can influence course design and the classroom environment. We suggest that teachers can develop greater authenticity in the classroom by deepening their understanding of their own philosophical ideas and beliefs.

Journal of Management Education, 2009

Teachers daily face situations with implicit fundamental questions pertaining to truth and of insight, to the moral dimension of actions, and to connectedness and love of one’s (civic and physical) environment. Whether conscious of it or not, teachers have implicit operational views on the nature of knowledge, ethics, and aesthetics. There is also, unfortunately, little doubt that all too many non-philosophers tend to undervalue, if not downright negate, the intrinsic importance of philosophy as well as its instrumental role in bringing to light our own developing sense what has traditionally been considered under the rubric of ‘the True, the Good, and the Beautiful’, of wonder and understanding, desire and morality, and love and beauty. Unless the teacher develops a reflective understanding of their own epistemological, ethical and aesthetic views, their judgement and consequent decisions leading to action remain diminished. I first make preliminary reflections on the practical role for philosophy highlighting the importance of insights into epistemology, ethics and aesthetic value. The discussion is framed by, and arises out of, considerations taken predominantly from the works of - mentioned in historical order - Rudolf Steiner, Bernard Lonergan, and John Deely. The discussion is developed in a manner that implicitly differentiates between the levels of experience, of object-formation, of judgement, and of ethical action. Though my paper is framed by the works of the aforementioned philosophers, it should be noted that my task is not to elucidate their respective works, but instead to allow aspects of their formidable contributions to play out through the lenses of my own experience as I personally strive towards a deeper understanding of essential characteristics in teacher formation.

UDEGBUNAM, D.O.M., 2013

Teaching Philosophy Statement, 2022

This Teaching Philosophy Statement (Third Edition) acts as a Teaching Portfolio, providing my experience and knowledge gained over the years of teaching and learning methods to be a successful educator. The personal teaching objectives are better aligned, the methods of teaching and learning are understood and the role of the actors (strategic educational platforms and educational institutions, teachers and researchers, students, and other target groups of learners) is further determined and better defined - thanks to the intensive postgraduate Pedagogical Course Harvard | The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. https://bokcenter.harvard.edu My goal: is to be a professional and inspiring lecturer in economics disciplines. I want to contribute to the students' progressive development and qualitative preparation to achieve their goals in life through modern methods of advanced teaching. My Offer: I am confident in taking teaching and learning approaches to the economics discipline, designing, expressing, organizing, and providing assessments for learning progression towards understanding and Higher-Order cognitions of constant thinking for evaluating, analyzing, and being creative. I believe that our modern societies need education in every corner of today's world, to some extent toning down traditional education and promoting advanced education, striving for better, and making progress using existing skills and intellectual capital. Societies are now at the center of the educational framework, creating politically affordable and economical offers (decision-making bodies), influencing stakeholders (educational institutions, teachers, learners, and parents) to act as well, quickly, and purposefully as possible, taking into account what is necessary for their school development and by is of public interest. I am enthusiastic and passionate about my desire to continue to be an inspirational and professional educator in business and engineering. I aim to apply my acquired knowledge and experience through the continuity of current teaching and vision methods and to serve the students to learn progressively, to have achieved their goals, and experience their lives through success stories. I hope this paper helps you define your teaching philosophy. Renato Preza

This paper explains that to bring about any form of educational equity for learners and teachers requires the realization that what is important is to educate the human disposition to understand the self. It identifies a unique relationship between the practical developmental phases of an educator toward a fully conscious professional and the philosophical scale of consciousness that leads to the understanding of the self by the self. The paper also discusses the necessary experiences and processes that lead an individual from one phase to the next, and it introduces a unique form of consciousness that combines elements of all other forms of knowledge and operates as an archeology of the self. The first section explains the importance of self-knowledge. The second section discusses forms of experience (art, religion, science, history, and philosophy). The third section describes the philosophical scale of consciousness. The fourth section discusses passion as a catalyst and the link...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

www.danielasieff.com, 2024

The Significance of Small Things: Essays in Honour of Diana Fane, 2018

Revista Colombiana De Sociologia, 2009

Heraldo de Aragón, La Firma, lunes, 15 de abril, p. 17, 2024

Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi, 2024

La protección de la vivienda habitual como exigencia del derecho a vivir de forma independiente de las personas con discapacidad, 2017

Illyrius, 2020

فاعلية استراتيجية التعلم المتمركز حول المشكلة في تنمية القدرة على حل المشكلات الاقتصادية المعاصرة ومهارات التفكير التأملي لدى الطلاب المعلمين شعبة الجغرافيا بكلية التربية, 2018

arXiv (Cornell University), 2009

Fractal and Fractional

Europace, 2018

International journal of tropical insect science, 2024

Experimental Biology and Medicine, 2006

Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1989

Deleted Journal, 2023

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- RUSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR

- BECOME A MEMBER

In Brief: The Ukrainian Operation Into Kursk

Post title post title post title post title.

Beginning on August 6, 2024, Ukrainian forces launched an incursion into Russian territory, pushing over seven miles into Kursk Oblast. Two weeks after the surprise operation, Ukrainian forces are still inching forward, deeper into Russia. We asked a panel of experts about the significance of the operation, how it might play out, and whether it could turn the tide of the war in Ukraine’s favor. Read more below. Oxana Shevel Associate Professor of Political Science & Director, International Relations Program Tufts University Ukraine’s unexpected incursion into Kursk turned the tables in the Russo-Ukrainian War, at least for now. Ukraine’s operation embarrassed Russia

This is members-only content. Become a member today to read more!

Will China Intervene Directly to Protect its Investments in Africa?

Horns of a dilemma, access denied non-aligned state decisions to grant access during war, rewind and reconnoiter: the arctic threat that must not be named.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

RCES303234CONTACT THE AUTHORS35From the AuthorsThis guide began as a collection of supplementary mater. al for a one-off workshop on essay-writing in philosophy. It is now presented to you as a han. book for students on the basics of philosophical writing. As supervisors ourselves, the four of us began the project out of a desire to offer extra ...

n philosophical writing:Avoid direct quotes. If you need to quote, quote sparingly, and follow your quotes by expla. ning what the author means in your own words. (There are times when brief direct quotes can be helpful, for example when you want to present and interpret a potential amb.

Chapter 1 - You, the Teacher as a Person in Society. Lesson 1 - Your Philosophical Heritage. Lesson Objectives. At the end of the lesson, the students will be able to: Discuss the underpinnings of the different schools of philosophies and their implications to teaching Formulate their personal philosophy of teaching and learning Explain the philosophy of education and the nature of teaching ...

These studies on the philosophical roots of heritage interpretation have been part of the InHerit project, a multi-lateral project which was supported by the EU's Grundtvig Programme. INHERIT / 540106-LLP-1-2013-1-BE-GRUNDTVIG-GMP Disclaimer: This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This

On the contrary, 'bottom-up' approaches are more capable to catch common people's attitude towards heritage, which is less inclined to grand structures (e.g., Macdonald Citation 2013), while seeking to preserve the 'sense of place' (e.g., Harrison and Rose Citation 2010); they also help to acknowledge the existence of 'unofficial ...

1. Planning. Typically, your purpose in writing an essay will be to argue for a certain thesis, i.e., to support a conclusion about a philosophical claim, argument, or theory.[4] You may also be asked to carefully explain someone else's essay or argument.[5] To begin, select a topic. Most instructors will be happy to discuss your topic with ...

The essays here confront Saramago's fiction with concepts, theories, and suggestions belonging to various philosophical traditions and philosophers including Plato, Pascal, Kierkegaard, Freud, Benjamin, Heidegger, Lacan, Foucault, Patočka, Derrida, Agamben, and Žižek. ... This introduction to the volume Saramago's Philosophical Heritage ...

The selection of essays provides an impressive array of themes that are not only collected to cater to the most obvious philosophical tastes. As many of the essays make explicit, it is challenging yet important to remain sensitive to social and political contexts or ethical issues more broadly when discussing material human heritage.

Abstract. The past decades have seen a growing "philosophical" interest in a number of authors, but strangely enough Saramago's oeuvre has been left somewhat aside. This volume aims at filling this gap by providing a diverse range of philosophical perspectives and expositions on Saramago's work. The chapters explore some possible issues ...

A guide to philosophical writing might make its dominant The aim of this guide is to help you to develop a good idea of what a philosophical paper should look like. While dialogues are fun and books are impressive, what you will write are papers. These will range from 2 to 0 pages in length. And in them you

The folklorist Maria Tatar writes that, in the world of the folktale, 'anything can happen, and what happens is often so startling … that it often produces a jolt.'. Folklore and philosophy are both in the business of startling us. Philosophy demands that we confront humanity's deepest anxieties and longings.

2.2 Body Sections. 2.3 Writing a Philosophy Paper Conclusion. 3 Template for a Philosophy Essay Structure. 4 How to Format a Philosophy Research Paper. 5 10 Steps to Write a Great Philosophy Paper Like a Pro. 5.1 Choose a Topic. 5.2 Read the Material and Take Notes. 5.3 Think about Your Thesis. 5.4 Make an Outline.

Here are several philosophy topics for essays that deal with Plato's beliefs and the timeless heritage. For example: The Theory of Forms: Understanding Plato's Concept of Reality ... Choosing the right philosophy essay topics can be overwhelming, so if you're struggling, you might consider seeking professional help to write my philosophy ...

The Teacher Philosophical Heritage. Kim Alcance. 2018, Kima0724.com. To philosophize is so essentially human- and in the sense to philosophize means living. -J. Pieper By: Kim B. Alcance (Group 1) See full PDF download Download PDF. Related papers. Republication of: Philosophy Rediscovered: Exploring the Connections Between Teaching ...

On 6 August 2024, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine as part of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Armed Forces of Ukraine launched an incursion into Russia's Kursk Oblast and clashed with the Russian Armed Forces and Russian border guard. [35] [36] [37] According to Russia, at least 1,000 troops crossed the border on the first day, supported by tanks and armored vehicles. [38]