Decoding Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Art: Exploring the Symbolism Behind His Iconic Paintings.

- White Court Art

Step into the captivating world of one of the most influential artists of our time, Jean-Michel Basquiat. With a brushstroke that defied convention and a mind that shattered boundaries, Basquiat’s art continues to leave an indelible mark on contemporary culture. In this blog post, we embark on an exhilarating journey to decipher the hidden meanings and symbolism behind his iconic paintings. Join us as we unravel the enigmatic puzzles painted by this artistic genius, revealing insights into society, race, identity – and ultimately understanding why Basquiat’s work remains both timeless and profoundly relevant today.

Introduction to Jean-Michel Basquiat and his impact on the art world

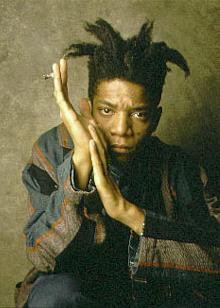

Jean-Michel Basquiat is a name that has become synonymous with contemporary art. Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1960, Basquiat rose to fame in the 1980s as a prominent figure in the Neo-Expressionist movement. Sax Berlin , a contemporary of JMB, recalls seeing Basquiat selling T Shirts on the street corners in the very early 1980s NYC. He was known for his raw and emotive paintings that combined elements of graffiti, street art, and primitivism.

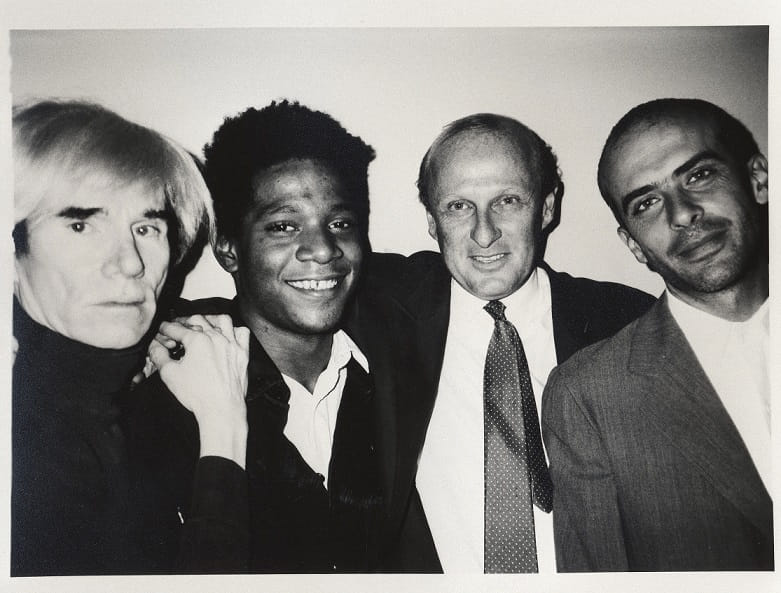

Basquiat’s rise to success was meteoric – from being a teenage graffiti artist on the streets of New York City to exhibiting his work alongside established artists like Andy Warhol. His unique style and use of symbolism have made him one of the most influential artists of the late 20th century.

But what sets Basquiat apart from other artists? What makes his work so enduring and impactful?

One of the key factors is his use of symbols in his paintings. Unlike traditional paintings that rely on realistic depictions, Basquiat’s works are filled with enigmatic symbols that invite viewers to interpret their meanings.

Basquiat drew inspiration from various sources such as African American history, pop culture, classical literature, and even personal experiences. His works often explore themes of race, identity, social inequality, politics, and mortality.

The combination of these symbols and themes created a powerful visual language that spoke to people from all walks of life. It allowed viewers to connect with Basquiat’s personal struggles while also addressing universal issues.

His impact on the art world goes beyond just his paintings; it also extends to breaking down barriers for minority artists. As an African American artist during a time when galleries were dominated by white males, Basquiat challenged societal norms and paved the way for future generations.

Moreover, he showed that street art can have a place in highbrow galleries – blurring the lines between “high” and “low” art forms. Basquiat’s success also opened doors for other street artists, giving them a platform to showcase their work and be recognized as legitimate artists.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s impact on the art world cannot be overstated. His use of symbols and powerful themes in his paintings has left a lasting impression on contemporary art. He challenged societal norms and paved the way for diversity in the art world while blurring the lines between different art forms. Through his legacy, he continues to inspire future generations of artists to push boundaries and tell their stories through their unique perspectives.

Understanding Basquiat’s unique style and use of symbols in his paintings

Jean-Michel Basquiat is known for his unique and iconic style of art that has captivated audiences around the world. His paintings are filled with bold colors, abstract figures, and most notably, an array of symbols that add a deeper layer of meaning to his work. In this section, we will dive into the world of Basquiat’s art and explore the symbolism behind some of his most famous paintings.

Basquiat’s use of symbols stems from his fascination with African-American history and culture. Growing up in New York City during the 1960s and 1970s, Basquiat was exposed to the vibrant street art scene which heavily influenced his style. He incorporated graffiti-like elements into his paintings along with references to African masks, Caribbean motifs, and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

One recurring symbol in Basquiat’s art is the crown or “three-pronged tiara.” This symbol represents power, authority, and royalty but also holds a deeper meaning related to Basquiat’s own identity as a black man in a predominantly white society. The artist often portrayed himself wearing this symbolic crown as a way to challenge societal norms and reclaim power for marginalized groups.

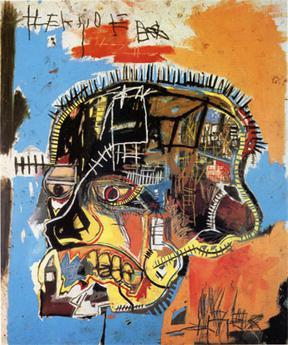

Another prominent symbol seen in Basquiat’s work is the skeletal figure or “skull.” This representation can be traced back to Basquiat’s childhood when he was involved in a serious car accident that left him hospitalized for weeks. The experience had a lasting effect on him and became a recurring image in his paintings. The skull also serves as a memento mori or reminder of death, adding an element of mortality to his work.

Basquiat also used words and letters as symbols in many of his pieces. He often included fragments of poetry or meaningful phrases written haphazardly across the canvas. These words served not only as visual elements but also added layers of context and commentary on social issues such as racism, poverty, and oppression.

In addition to these recurring symbols, Basquiat also incorporated references to pop culture, history, and personal experiences into his paintings. He would often combine seemingly unrelated images and symbols to create a visual narrative that invites the viewer to interpret their meaning for themselves.

Basquiat’s unique style and use of symbols have made him one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. His art continues to inspire and challenge viewers, inviting them to delve deeper into the layers of meaning behind each piece. By understanding the symbolism in Basquiat’s work, we can gain a greater appreciation for his art and its impact on society.

Uncovering the meanings behind some of his most iconic works

One of the most intriguing aspects of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art is the symbolism behind each of his iconic works. From his use of recurring motifs to his incorporation of cultural references, Basquiat’s paintings are filled with hidden meanings waiting to be uncovered. sax Berlin pays homage to the symbolism of Basquiat and the manner of his burn out in the spotlight with his work “Caught In the Crossfire”.

One such example is his famous painting “Untitled (Skull)”, which features a large skull in the center surrounded by colorful graffiti-like marks and text. At first glance, the skull may seem like a simple representation of death or mortality. However, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that Basquiat was commenting on societal issues such as racism and inequality.

The use of text in this painting is also significant. Basquiat often incorporated words and phrases from different languages into his artwork, reflecting his multicultural background and making powerful statements about identity and belonging. In “Untitled (Skull)”, he includes words like “crown” and “king”, possibly referencing the exploitation of black bodies by white society.

Another one of Basquiat’s well-known works is “Hollywood Africans”, a painting that showcases three figures wearing crowns made out of TV sets. This piece has been interpreted as a commentary on how black artists are commodified by the entertainment industry. The TV sets represent how African Americans are reduced to mere objects for consumption by mainstream media.

Basquiat’s fascination with history can also be seen in many of his paintings, particularly in “Charles the First”. This piece features a portrait of King Charles I with an X over his face, symbolizing rebellion against oppressive systems. It also includes historical references such as images from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, reflecting Basquiat’s interest in art history and its influence on contemporary culture.

In addition to social commentary, Basquiat’s art also delves into personal struggles and emotions. Take for instance his self-portrait titled “Self-Portrait with Sliced Ear”. The sliced ear represents Van Gogh’s infamous self-mutilation and serves as a reflection of Basquiat’s own battles with mental health and addiction.

Basquiat’s art is a complex web of symbols and references that reflect his experiences and beliefs. By decoding these elements, we gain a deeper understanding of the artist and his impact on the art world. His works continue to inspire and challenge viewers, making him an iconic figure in contemporary art history.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art is known for its raw and powerful expression, filled with symbolism and references to his cultural background and personal experiences. Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1960 to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat was deeply influenced by the vibrant street culture of the city as well as his diverse heritage. These elements played a significant role in shaping his unique artistic style and subject matter.

Growing up in Brooklyn during the 1960s and 70s, Basquiat was exposed to the graffiti writing movement that emerged in New York City at the time. This subculture of street art had a major impact on him, inspiring him to create his own bold and colorful artworks on abandoned buildings and subway trains. The influence of this urban environment can be seen in many of Basquiat’s paintings, with their vivid colors, bold lines, and use of text reminiscent of graffiti tags.

Basquiat’s Haitian heritage also had a profound influence on his art. His father introduced him to African American history and encouraged him to embrace his roots through visits to Haiti as well as introducing him to artists like jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie who were proud of their African heritage. These experiences instilled in Basquiat a deep appreciation for Black culture which he often incorporated into his work through imagery such as masks or references to voodoo symbols.

Furthermore, Basquiat’s personal experiences greatly impacted his artwork. He faced numerous struggles throughout his life including poverty, discrimination, addiction, and mental health issues which are reflected in many of his paintings. For example, “Irony of Negro Policeman” (1981) is a direct response to an incident where he was racially profiled by police while walking with artist friend Keith Haring.

Basquiat also drew inspiration from other influential figures such as jazz musician Charlie Parker or boxer Sugar Ray Robinson who he admired for breaking barriers and achieving success despite facing discrimination. Their stories of resilience and determination resonated with Basquiat and can be seen in works such as “Charles the First” (1982) which references Charlie Parker.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art was heavily influenced by his cultural background and personal experiences. From his upbringing in Brooklyn to his Haitian heritage and encounters with racism, all these elements played a crucial role in shaping his artistic identity. His ability to incorporate these diverse influences into his work is what makes his paintings so powerful and iconic, making him one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Analyzing the social commentary in Basquiat’s work and its relevance today

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artwork is known for its bold and provocative visual language, but it also carries a strong social commentary that remains relevant even today. Born in Brooklyn to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat’s art often explored themes of race, class, power, and identity – issues that are still prevalent in our society.

One of the most striking aspects of Basquiat’s work is his use of symbols and words to convey his message. His paintings are filled with cryptic phrases, cultural references, and powerful images that challenge the viewer to think deeper about the world around them. For instance, in his painting “Irony of a Negro Policeman,” Basquiat addresses the complex relationship between African Americans and law enforcement. The central figure in the painting is a black police officer depicted as a skeletal figure with an exaggerated smile – symbolizing how black people are forced to conform to societal expectations while being constantly marginalized by those in power.

Similarly, in “Notary,” Basquiat uses imagery from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics to comment on the commodification of African culture by Western societies. The painting features a pyramid-shaped head with various symbols representing money, power, and exploitation – highlighting the exploitation of non-Western cultures for profit.

Basquiat was also deeply influenced by jazz music and used it as inspiration for many of his works. In “Horn Players,” he pays homage to legendary jazz musicians like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie while commenting on cultural appropriation and racism within the music industry. The white mask-like faces represent how black artists have been reduced to caricatures or imitations by mainstream media.

Beyond racial issues, Basquiat’s work also delved into broader societal problems such as capitalism, consumerism, and environmental degradation. In “Obnoxious Liberals,” he criticizes the hypocrisy of wealthy liberals who claim to support progressive causes but continue to benefit from a corrupt capitalist system. The painting features an image of a pig wearing a suit – symbolizing the greed and excesses of the upper class.

Despite being created in the 1980s, Basquiat’s social commentary is still relevant today. In fact, his works often foreshadowed many of the issues we face in modern society, such as gentrification, police brutality, income inequality, and cultural appropriation. By analyzing these themes in Basquiat’s art, we can gain a deeper understanding of our present-day realities and continue to challenge them for a better future.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art is known for its bold and expressive style, often featuring a mix of writing, symbols, and figures that seem to tell a story. But what do all these elements mean? In this section, we will delve into the symbolism behind some of Basquiat’s most iconic paintings.

One recurring symbol in Basquiat’s art is the crown. It can be found in many of his works, often depicted as a simple outline or filled in with vibrant colors. The crown represents power and authority, but it also carries deeper connotations for Basquiat. As an artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, he frequently explored themes of colonialism and oppression in his work. The crown can therefore be seen as a commentary on societal structures that limit marginalized communities from attaining true power.

Another prominent symbol in Basquiat’s art is the human skull. This motif appears repeatedly throughout his career and has been interpreted in various ways by critics. Some see it as a reminder of mortality and the fleeting nature of life, while others view it as a reflection on societal violence and injustice. In one particular painting titled “Irony of Negro Policeman,” the skull is placed next to a police officer figure, possibly commenting on systemic racism within law enforcement.

Basquiat was also heavily influenced by African American history and culture, which can be seen through his incorporation of African masks into several pieces. These masks carry significant cultural meaning for Black communities, representing ancestral connection and spiritual protection. By including them in his artwork, Basquiat highlights their importance while also reclaiming them from their appropriation by Western societies.

In addition to symbols imbued with personal significance or social commentary, Basquiat also incorporated references to popular culture into his work. He often included images from comics or cartoons such as Mickey Mouse or Superman alongside more serious subject matter like racial inequality or political corruption. This juxtaposition serves as a commentary on the superficiality of American consumerist culture and its ability to distract from larger societal issues.

Basquiat’s use of symbols and imagery in his art is not limited to specific meanings or interpretations. Instead, he invites viewers to engage with his work and draw their own conclusions. His paintings are meant to provoke thought and spark conversations about important topics. By decoding the symbolism behind his art, we can gain a deeper understanding of Basquiat’s message and appreciate the layers of meaning within each piece.

Recently Viewed

Apply as an artist.

We are happy to give advice If you are interested in a particular artist or would like us to locate works by that artist or would like us to source works for interior design projects.

Follow Artist

Contact artist.

Jean-Michel Basquiat

American Painter

Summary of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat moved from graffiti artist to downtown punk scenester to celebrity art star in only the few short years of his career. This vertiginous rise took him from sleeping on the streets of New York City to being befriended by Andy Warhol and entering into the elite American art world as one of the most celebrated painters of the Neo-Expressionism art movement. Whilst Basquiat died at only 27 of a heroin overdose, he has now become indelibly associated with the surge in interest in downtown artists in New York during the 1980s. His work explored his mixed African, Latinx, and American heritage through a visual vocabulary of personally resonant signs, symbols, and figures, and his art developed rapidly in scale, scope, and ambition as he moved from the street to the gallery. Much of his work referenced the distinction between wealth and poverty, and reflected his unique position as a working-class person of color within the celebrity art world. In the years following his death, the attention to (and value of) his work has steadily increased, with one painting even setting a new record in 2017 for the highest price paid for an American artist's work at auction.

Accomplishments

- Basquiat's work mixed together many different styles and techniques. His paintings often included words and text, his graffiti was expressive and often abstract, and his logos and iconography had a deep historical resonance. Despite his work's "unstudied" appearance, he very skillfully and purposefully brought together a host of disparate traditions, practices, and styles to create his signature visual collage.

- Many of his artworks reflect an opposition or tension between two poles - rich and poor, black and white, inner and outer experience. This tension and contrast reflected his mixed cultural heritage and experiences growing up and living within New York City and in America more generally.

- Basquiat's work is an example of how American artists of the 1980s began to reintroduce and privilege the human figure in their work after the domination of Minimalism and Conceptualism in the international art market. Basquiat and other Neo-Expressionist painters were seen as establishing a dialogue with the more distant tradition of 1950s Abstract Expressionism , and the earlier Expressionism from the beginning of the century.

- Basquiat's work is emblematic of the art world recognition of punk, graffiti, and counter-cultural practice that took place in the early 1980s. Understanding this context, and the interrelation of forms, movements, and scenes in the readjustment of the art world is essential to understanding the cultural environment in which Basquiat made work. Subcultural scenes, which were previously seen as oppositional to the conventional art market, were transformed by the critical embrace and popular celebration of their artists.

- For some critics, Basquiat's rapid rise to fame and equally swift and tragic death by drug overdose epitomizes and personifies the overtly commercial, and hyped-up international art scene of the mid-1980s. For many observers this period was a cultural phenomenon that corresponded negatively with the largely artificial bubble economy of the era, to the detriment of artists personally and the quality of artworks produced.

The Life of Jean-Michel Basquiat

"I wanted to be a star, not a gallery mascot", Basquiat said. His life echoes this rise and struggle, and reveals the important dialogue between authenticity, representation, identity and recognition that is at the heart of understanding his work.

Important Art by Jean-Michel Basquiat

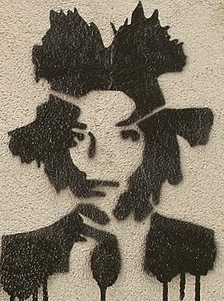

Basquiat began painting graffiti in the late 1970s, often socializing and working alongside other artists of the subculture in the Bronx and Harlem. Graffiti artists often focused on figurative images (cartoonish pictures of animals, people and objects), as well as simple 'tags' - logos or names designed to be a trademark or calling card, which was where Basquiat also began. But Basquiat's graffiti quickly developed in a more abstract direction, with the "SAMO" tag origins quite mysterious and loaded with symbolism. This particular black spray paint tag on a wall is emblematic of the SAMO works that Basquiat and his collaborator Al Diaz made between 1976 and 1980. Quickly applied to public spaces in the street and subway, the SAMO pieces conveyed short, sharp, and frequently anti-materialist messages to passersby. Usually seen as a sign of trespassing and vandalism, graffiti in the hands of Diaz and Basquiat became a tool of artistic "branding", and represents an important stage in the development of Basquiat's work. The concept of SAMO, or "Same Old Shit", was developed during Basquiat's involvement with a drama project in New York, where he conceived a character that was devoted to selling a fake religion. Diaz and Basquiat applied the implicit critique embodied by this snake-oil-salesman figure to the commercial and corporate enterprises that they saw hawking goods in public spaces across their city. They initially began to spray paint the slogans that made up the works across subway trains as a way of "letting off steam" but, as Diaz remembers, they rapidly realized that it fulfilled an important role when they compared the work to more conventional graffiti tags. As Diaz says, "SAMO was like a refresher course because there was a statement being made". After years of collaboration, Diaz and Basquiat chose to signify the end of their joint venture with the three-word announcement "SAMO IS DEAD". Carried out episodically in various cites as a piece of ephemeral graffiti art, the phrase surfaced repeatedly on gritty buildings, particularly those throughout Lower Manhattan, where Basquiat and his collaborators carried out much of their artistic activity.

Graffiti - Location unknown (New York City)

Untitled (Skull)

An example of Basquiat's early canvas-based work, Untitled (Skull) features a patchwork skull that seems almost a pictorial equivalent of the monster from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein - a constructed and sutured sum of incongruent parts. Suspended before a background that suggests aspects of the New York City subway system, the skull is at once a contemporary graffitist's riff on a long Western tradition of self-portraiture, and the "signature piece" of a streetwise bohemian. The expression on the skull-like face is downcast, with the rough stitches suggesting an unhappy combination of constituent parts. The colors used, which mix and swirl together, suggest bruising or wounds to the face, combining with the jagged lines to imply violence or its aftermath. Basquiat's recent past as a curbside peddler, homeless person, and nightclub personality at the time that he created this piece are all equally stamped into the troubled three-quarter profile. Together these characteristics suggest that the piece becomes a world-weary icon of the displaced Puerto-Rican and Haitian immigrant Basquiat seemed to think himself doomed to remain, even while successfully navigating the newly gentrified streets of 1980s SoHo and the art market that took an interest in them.

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas - The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Untitled (Black Skull)

Like a page pulled cleanly from a daily artist's journal, this untitled canvas features an array of Basquiat's personal iconography and recurring symbols set against a black background and smeared patches of bright paint. A white skull juts from the center of the ebony composition, vividly recalling the revered painter's tradition of the memento mori - a reminder of the ephemeral nature of all life and the body's eventual, merciless degeneration. The bone to the right of the canvas could also be read as a phallus, suggesting the representation of Black male sexuality as threatening or primitive (particularly when positioned next to the arrow in the painting). Scales appear directly below the skull, perhaps representing the scales of justice and therefore implying the inequality in treatment of Black men by the police and justice system that is perpetuated to this day. Boldy appropriating images commonly associated with rural African art - a skull, a bone, an arrow - Basquiat modernizes them with his Neo-Expressionist style of thickly applied paint, rapidly rendered subjects, and scrawled linear characters, all of which float loosely across the pictorial field, as though hallucinatory. Basquiat demonstrates in one concise "study" how he is able to carry on an ancient practice of painting "still life" all the while suggesting that the artist's work was relatively effortless, if not completely improvisatory, as in the performance of a jazz musician. Nevertheless, the density of the imagery and its loaded symbolism reveal Basquiat's skill and his ability in composition.

Acrylic, oil stick, and spray paint on canvas - The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Flexible features two of Basquiat's most famous motifs: the griot and the venerable crown. An emaciated black figure stares out from the canvas towards the viewer, its arms creating a closed circuit in what may be a reference to spiritualized energy, a concept which appears in several works featuring the griot . The work also reflects Basquiat's development as an artist and is a synthesis of his influences, with the diagrammatic rendering of the figure's lungs and abdomen reminiscent of the young Basquiat's fascination with anatomical sketches from Gray's Anatomy. Whilst its lack of distinguishing characteristics might imply an "Everyman", the specifically African ethnicity of the figure provides a clear reference to Basquiat's own identity and background. In its color palette and the particular rendering of the human figure through thin limbs and a large head, the influence of the shapes and forms of traditional West African art is apparent. Art historian and Basquiat collaborator Fred Hoffman writes that the image represents a tribal king, one whose "posture, with arms raised and interlocked above his head, conveys confidence and authority, attributes of his heroism. He seems to be crowning himself. Given that the griot is traditionally a kind of wandering philosopher, street performer, and social commentator, it is possible that Basquiat saw himself taking up this role within the New York art world, which nurtured his artistic success but also swiftly exploited it for material profit. The image is painted on wooden slats, which Basquiat asked his assistants to remove from a fence that protected the boundary of his Los Angeles studio. By removing this barrier, Basquiat made the property open, and able to be traversed across freely, perhaps reflecting his empathy and personal experience of the limits of public space as a homeless person in New York.

Acrylic and oil paint stick on wood - Private Collection

Untitled (History of the Black People)

At the center of this painting, Basquiat depicts a yellow Egyptian boat being guided down the Nile River by the god Osiris. Two Nubian masks appear in the left of the image, under the word "NUBA", whilst graffiti-esque tags are scrawled over a silhouetted blackdog, reads "a dog guarding the pharaoh". Other text in the image includes "Memphis [Thebes] Tennessee" "sickle" (repeated several times in the central panel, and directly referencing slave trade), "Hemlock" (in the bottom right corner), "esclave slave esclave") superimposed over a silhouetted black human figure, as well as the Spanish phrases "El gran espectaculo" (along the top of the image), and "mujer" (next to a crudely drawn figure with circular breasts). In this expansive early work, also referred to as The Nile, Basquiat reconstructs the epic history of his own ancestors' arrival on the American continent. This includes references to Egypt and the rest of Africa, as well as more local centers of African-American music in the Southern United States. Rife with visual and textual references to African history, the painting tackles a heady subject within Basquiat's trademark aesthetic. Art historian Andrea Frohne suggests that the painting "reclaims Egypt as African", attempting to undo the revisionist positioning of Ptolemaic Egypt as a precursor to Western Civilisation and instead emphasizing its African identity. This corresponds to attempts within the African-American community to reconnect with a specifically African heritage and history in the 1980s, which may have influenced Basquiat's development of the piece. Curator Dieter Buchhart asserts that "Basquiat was drawing and painting the Black experience in which any person from the African Diaspora could see themselves reflected and drawing attention to both their collective successes and struggles. Basquiat’s African-American men are usually not only ready to struggle but also intent on resistance." Many of Basquiat's late-period works feature similar multi-panel paintings, in the tradition of Renaissance religious triptychs, and canvases with exposed stretcher bars. Often the surfaces of these pieces are virtually consumed by the density of the writing, collage, and varied imagery.

Acrylic paint and oil paint stick on panel - The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

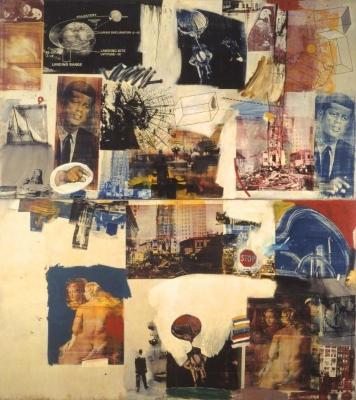

Arm and Hammer II

In this collaborative painting, Basquiat paints over Andy Warhol's trademark reproduction of a corporate logo, in this case for the Arm and Hammer brand of baking soda. Adjusting one of the two reproductions of the logo that appear in the painting to show a Black saxophonist instead of the flexing white arm, Basquiat frames the image with text which reads "Liberty 1955". The insertion of an image of Black creativity within an advertising logo may be an assertion of agency and reclamation of public space by Basquiat. It is also a visual reference to jazz, an African-American musical form that reached new heights of popularity in the 1950s, and an implicit acknowledgement of the repression of Black people that existed despite the music's success and incorporation into American identity. Moreover, the insertion of an image of Black creativity within an advertising logo may be an assertion of agency and reclamation of public space by Basquiat. Typical of their collaboration, Arm and Hammer II demonstrates how Basquiat and Warhol would pass a work between them, like a game of chance happening, free association, and mutual inspiration. Warhol's characteristic employment of corporate logos and advertising copy as shorthand signs for the materialistic modern psyche is frequently overlaid by Basquiat's attempt to deface them in his freehand style, as though he were vainly raising his own fist at a largely invisible, insidious and monolithic monster in the form of corporate America.

Acrylic and silkscreen on canvas - Gallery Bruno Bischofberger AG

Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper)

Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper) is a collaboration between Basquiat and Andy Warhol, commissioned by Alexandre Iolas, the international art gallerist and collector. Basquiat painted each of ten white punching bags with an image of Jesus, as well as the word “Judge” repeated several times on each bag. The piece was originally intended to be displayed in Milan directly across the street from Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper . Opposite the Renaissance masterpiece, Ten Punching Bags was to function, somewhat playfully, as a "call to arms" for contemporary art against all forms of ideological oppression. Christian readings of the piece were generally (and perhaps surprisingly) very positive, the representation of Jesus as a punching bag corresponding to the concept that he took on the sins of human beings, receiving the punches that they might be free. Reverend Harold T. Lewis wrote that Basquiat's contribution to the work tied the role of Jesus to poverty, suggesting that the iconography both religious and secular added by Basquiat creates a situation where "Jesus the Judge himself is judged by the squalor of urban poverty". Basquiat and Warhol suggested that this piece was among their favorite collaborations, as it represented an effective blend of their respective styles. Both artists made important contributions to the design. Warhol's influence is made clear by the careful color composition and physical installation, which is reminiscent of several of his iconic brand works. Basquiat's expressive renderings of Jesus and signature crown motifs disrupt the clean lines and organized placement however, much like graffiti disrupts the order of corporatized public space.

Acrylic and oil stick on punching bags - The Andy Warhol Museum

Riding with Death

Riding with Death is one of Basquiat's final paintings, and one which can easily be read as representing his inner turmoil and increasing conviction that the racist, classist, and corrupt nature of America in the 1980s was visible everywhere, including in the art world. Painted in the weeks before his death, the bleakness and sadness of the image and its title is only enhanced by the knowledge that the artist's life would come to an end far too soon shortly after its completion. Less cluttered and visually dense than many of his earlier paintings, Riding with Death features a textured brown field onto which Basquiat has depicted an African figure riding a skeleton. The skeleton crawls on all fours towards the left-hand side of the image, whilst the rider, rendered in less detail than the bones on which they sit, writhes or flails its arms. The skull faces the viewer, its cartoonish proportions and broad expression suggesting the gestural graffiti that remained a core stylistic influence on Basquiat's painting. The simplicity of the background and the subject matter are also reminiscent of pre-historic cave art, as well as later African tribal art. The head of the African figure is indistinct, its features obscured by black scribbles apart from a single eye in its forehead. The central figures, although simply framed, are loaded with symbolism. The pair suggest a nihilism or journey towards death that is made more poignant by Basquiat's dependence upon heroin and other drugs at the time of its painting. Although the African figure is riding the skeleton and could therefore be read as being in a position of dominance, the assertive positioning of the skeleton suggests instead that it is in control, perhaps dragging the rider to the far side of the frame. Coupled with the distinction in color between the two (a white skeleton and Black rider), this couple could be read as a metaphor for the repression and destruction of African societies by colonial powers, as well as the inequalities that existed within 1980s America for people of color. This work is an excellent example of the complex meanings Basquiat was able to communicate and suggest through a complex visual language regularly referred to by critics as "primitive" or "naïve". As this poignant image shows, Basquiat's work was in fact highly sophisticated and far more technically accomplished than is often credited.

Acrylic and crayon on canvas - Private Collection

Biography of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn in 1960. His mother, Matilde Andradas was born also born in Brooklyn but to parents from Puerto Rico. His father, Gerard Basquiat, was an immigrant from Port-au-Prince, Haiti. As a result of this mixed heritage the young Jean-Michel was fluent in both French and Spanish as well as English. His early readings of French symbolist poetry in their original language would later be an influence on the artworks that he made as an adult. Basquiat displayed a talent for art in early childhood, learning to draw and paint with his mother's encouragement and often using supplies (such as paper) brought home from his father's job as an accountant. Together Basquiat and his mother attended many museum exhibitions in New York, and by the age of six Jean-Michel was enrolled as a Junior Member of the Brooklyn Museum. He was also a keen athlete, competing in track events at his school.

After being hit by a car while playing in the street at age 8, Basquiat underwent surgery for the removal of his spleen. This event led to his reading the famous medical and artistic treatise, Gray's Anatomy (originally published in 1858), which was given to him by his mother whilst he recovered. The sinewy bio-mechanical images of this text, along with the comic book art and cartoons that the young Basquiat enjoyed, would one day come to inform the graffiti-inscribed canvases for which he became known.

After his parents' divorce, Basquiat lived alone with his father, his mother having been determined unfit to care for him due to her mental health problems. Citing physical and emotional abuse, Basquiat eventually ran away from home and was adopted by a friend's family. Although he attended school sporadically in New York and Puerto Rico, where his father had attempted to move the family in 1974, he finally dropped out of Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn in September 1978, at the age of 17.

Early Training

As Basquiat stated, "I never went to art school. I failed the art courses that I did take in school. I just looked at a lot of things. And that’s how I learnt about art, by looking at it". Basquiat's art was fundamentally rooted in the New York City graffiti scene of the 1970s. After becoming involved in an Upper West Side drama group called Family Life Theater he developed the character SAMO (an acronym for "Same Old Shit"), a man who tried to sell a fake religion to audiences. In 1976, he and an artist friend, Al Diaz, started spray-painting buildings in Lower Manhattan under this nom de plume . The SAMO pieces were largely text based, and communicated an anti-establishment, anti-religion, and anti-politics message. The text of these messages was accompanied by logos and imagery that would later feature in Basquiat's solo work, particularly the three-pointed crown.

The SAMO pieces soon received media attention from the counterculture press, most notably the Village Voice , a publication that documented art, culture, and music that saw itself as distinct from the mainstream. When Basquiat and Diaz had a disagreement and decided to stop working together, Basquiat ended the project with the terse message: SAMO IS DEAD. This message appeared on the facade of several SoHo art galleries and downtown buildings during 1980. After taking note of the declaration, Basquiat's friend and Street Art collaborator Keith Haring staged a mock wake for SAMO at Club 57, an underground nightclub in the East Village.

During this period Basquiat was frequently homeless and forced to sleep at friend's apartments or on park benches, supporting himself by panhandling, dealing drugs, and peddling hand-painted postcards and T-shirts. He frequented downtown clubs however, particularly the Mudd Club and Club 57, where he was known as part of the "baby crowd" of younger attendees (this group also included actor Vincent Gallo). Both clubs were popular hangouts for a new generation of visual artists and musicians, including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf , movie director Jim Jarmusch and Ann Magnusson, all of whom became friends and occasional collaborators with Basquiat. Haring in particular was a notable rival as well as a friend, and the two are often remembered as competing with each other to improve the scope, scale, and ambition of their work. The two both gained recognition at similar points in their careers, progressing in parallel to reach the heights of art world stardom.

Due in part to his immersion in this downtown scene, Basquiat began to gain more opportunities to show his art, and became a key figure in the new downtown artistic movement. For example, he appeared as a nightclub DJ in Blondie's music video Rapture , cementing his cache as a figure within the "new wave" of cool music, art, and film emerging from the Lower East Side. During this time he also formed and performed with his band Gray. Basquiat was critical of the lack of people of color in the downtown scene, however, and in the late 1970s he also began spending time uptown with graffiti artists in the Bronx and Harlem.

After his work was included in the historic Times Square Show of June 1980, Basquiat's profile rose higher, and he had his first solo exhibition in 1982 at the Annina Nosei Gallery in SoHo. Rene Ricard's Artforum article, "The Radiant Child", of December 1981, solidified Basquiat's position as a rising star in the wider art world, as well as the conjunction between the uptown graffiti and downtown punk scenes his work represented. Basquiat's rise to wider recognition coincided with the arrival in New York of the German Neo-Expressionist movement, which provided a congenial forum for his own street-smart, curbside expressionism. Basquiat began exhibiting regularly alongside artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle , all of whom were reacting, to one degree or another, against the recent art-historical dominance of Conceptualism and Minimalism . Neo-Expressionism marked the return of painting and the re-emergence of the human figure in contemporary art making. Images of the African Diaspora and classic Americana punctuated Basquiat's work at this time, some of which was featured at the prestigious Mary Boone Gallery in solo shows in the mid 1980s (Basquiat was later represented by art dealer and gallerist Larry Gagosian in Los Angeles).

Mature Period

1982 was a significant year for Basquiat. He opened six solo shows in cities across the world, and became the youngest artist ever to be included in Documenta, the prestigious international contemporary art extravaganza held every five years in Kassel, Germany. During this time, Basquiat created some 200 art works and developed a signature motif: a heroic, crowned black oracle figure. The legendary jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie and boxers Sugar Ray Robinson, and Muhammad Ali were among Basquiat's inspirations for his work during this period. Sketchy and often abstract, the portraits captured the essence rather than the physical likeness of their subjects. The ferocity of Basquiat's technique, with slashes of paint and dynamic dashes of line, was intended to reveal what he saw as his subjects' inner self, their hidden feelings, and their deepest desires. These works also reinforced the intellect and passion of their subjects, rather than being fixated on the fetishized Black male body. Another epic figuration, based on the West African griot , also features heavily in this era of Basquiat's work. The griot propagated community history in West African culture through storytelling and song, and he was typically depicted by Basquiat with a grimace and squinting elliptical eyes fixed securely on the observer. Basquiat's artistic strategies and personal ascendency was in keeping with a wider Black Renaissance in the New York art world of the same era (exemplified by the widespread attention being given at the time to the work of artists such as Faith Ringgold and Jacob Lawrence ).

By the early 1980s, Basquiat had befriended Pop artist Andy Warhol , with whom he collaborated on a series of works from 1984 to 1986, such as Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper) (1985-86). Warhol would often paint first, then Basquiat would layer over his work. In 1985, a New York Times Magazine feature article declared Basquiat the hot young American artist of the 1980s. This relationship became the subject of friction between Basquiat and many of his downtown contemporaries, as it appeared to mark a new interest in the commercial dimension of the art market.

Warhol was also criticized for potential exploitation of a young and fashionable artist of color to boost his own credentials as current and relevant to the newly significant East Village scene . Broadly speaking, these collaborations were not well received by either audiences or critics, and are now often viewed as lesser works of both artists.

Perhaps as a result of the new-found fame and commercial pressure put upon his work, Basquiat was by this point of his life becoming increasingly addicted to both heroin and cocaine. Several friends linked this dependency to the stress of maintaining his career and the pressures of being a person of color in a predominantly white art world. Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his apartment in 1988 at the age of 27.

The Legacy of Jean-Michel Basquiat

In his short life Jean-Michel Basquiat nonetheless came to play an important and historic role in the rise of the downtown cultural scene in New York and Neo-Expressionism more broadly. While the larger public latched on to the superficial exoticism of his work and were captivated by his overnight celebrity, his art, which has often been described inaccurately as "naif" and "ethnically gritty", held important connections to expressive precursors, such as Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly .

A product of the celebrity and commerce-obsessed culture of the 1980s, Basquiat and his work continue to serve for many observers as a metaphor for the dangers of artistic and social excess. Like the comic book superheroes that formed an early influence, Basquiat rocketed to fame and riches, and then, just as speedily, fall back to Earth, the victim of drug abuse and eventual overdose.

The recipient of posthumous retrospectives at the Brooklyn Museum (2005) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (1992), as well as the subject of numerous biographies and documentaries, including Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child (2010), and Julian Schnabel's feature film, Basquiat (1996; starring former friend David Bowie as Andy Warhol), Basquiat and his counter-cultural legacy persist. In 2017, another film Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean Michel Basquiat was released to critical acclaim, also inspiring an exhibition of the same title at the Barbican art gallery in London. His art remains a constant source of inspiration for contemporary artists, and his short life a constant source of interest and speculation for an art industry that thrives on biographical legend.

Alongside his friend and contemporary Keith Haring, Basquiat's art has come to stand in for that particular period of countercultural New York art. Both artists' work is frequently exhibited alongside the other's (most recently in the 2019 exhibition 'Keith Haring I Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines' in Melbourne, Australia), and there have been a number of commercial licenses granted for the reproduction of several of his visual motifs. Recently this has included a range of graphic print shirts at Uniqlo displaying the work of both artists.

The rise in Basquiat's profile since his death has also pushed new artists to make work inspired by or even in direct reference to his work. This includes painters, graffiti and installation artists working within the gallery, but also musicians, poets and filmmakers. Visual artists influenced by Basquiat include David Hewitt, Scott Haley, Barb Sherin, and Mi Be in North America, as well as European and Asian artists such as David Joly, Mathieu Bernard-Martin, Mikael Teo, and Andrea Chisesi, all of whom cite his work as formative to their own development. Musicians such as Kojey Radical, Shabaka Hutchings, and Lex Amor have similarly praised his work as informing their own. These three musical artists in particular appeared alongside others on Untitled , a collaborative compilation released as a tribute to Basquiat in 2019 by London based record label The Vinyl Factory.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art Our Pick By Phoebe Hoban

- Warhol on Basquiat: The Iconic Relationship Told in Andy Warhol’s Words and Pictures Our Pick By Michael Dayton Hermann

- Basquiat’s "Defacement": The Untold Story Our Pick By Chaédria LaBouvier, Nancy Spector, J. Faith Almiron, Greg Tate, Luc Sante, Carlo McCormick, Jeffrey Deitch, Kenny Scharf, Fred Braithwaite, and Michelle Shocked

- Basquiat: Art Masters Series By Julian Voloj

- Basquiat By Leonhard Emmerling

- Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th Street 1979-1980 Our Pick By Nora Burnett Abrams

- Jean-Michel Basquiat. 40th Anniversary Edition Our Pick By Eleanor Nairne and Hans Werner Holzwarth

- Basquiat By Marc Mayer

- Jean-Michel Basquiat By Robert Farris Thompson and Renee Ricard

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's the Time By Dieter Buchhart, Franklin Sirmans, Olivier Berggruen, Glenn O'Brien, and Christian Campbell

- The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews, and Critical Responses By Jordana Moore Saggese

- Basquiat: Boom for Real Our Pick By Dieter Buchhart and Eleanor Nairne

- Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Our Pick By J. Faith Almiron, Dakota DeVos, Hua Hsu, Carlo McCormick, Liz Munsell, and Greg Tate

- Basquiat and the Bayou By Franklin Sirmans, Robert Farris Thompson, and Robert OMeally

- Basquiat: By Himself Our Pick By Dieter Buchhar, Anna Karina Hofbauer, A.K. Hofbauer, L. Jaffe, L. Rideal, D. Buchhart , B. Bischofsberger, N. Cullinan, and M. Halsband

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1981: the Studio of the Street Our Pick By Diego Cortez

- Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Young Fun Our Pick Basquiat's best work. / By Peter Schjeldahl / The New Yorker / APRIL 4, 2005

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child By Stephen Holden / New York Times / July 20, 2010

- The Jean-Michel Basquiat I knew… By Miranda Sawyer / The Guardian / September 3, 2017

- Nationalizing Abject American Artists: Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Jean-Michel Basquiat Our Pick By Julie Codell / Auto/Biography Studies / Summer 2011

- “Why Can’t I Be Both?” Jean-Michel Basquiat and Aesthetics of Black Bodies Reconstituted Our Pick By Anthony B. Pinn / Journal of Africana Religions / 2013

- “Cut and Mix”: Jean-Michel Basquiat in Retrospect Our Pick By Jordana Moore Saggese / Journal of Contemporary African Art / Spring 2011

- Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, filmed in 1986 Our Pick

- The Chaotic Brilliance of Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat - Jordana Moore Saggese Our Pick TED-Ed

- Jean Michel Basquiat / The Radiant Child (2010) (Full-Length Documentary) Our Pick Creatime Diseño Gráfico

- Jean-Michel Basquiat's 'Untitled (Skull)’ Our Pick Great Art Explained

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: How A Street Artist Transcended Pop Art Our Pick Soulr

- Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring & Jean-Michel Basquiat | ARTST TLK Our Pick Reserve Channel

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: Interview With His Family Localish

- 'Radiant Child' A Rare Insight Into Basquiat's Mind All Things Considered, NPR

- Basquiat (1996) Our Pick Film directed by Julian Schnabel

- Downtown 81 (1981) Our Pick Striking "lost" film that features Basquiat in lead role

Similar Art

Grand Maitre of the Outsider (1947)

Skyway (1964)

Leda and the Swan (1962)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Bonnie Rosenberg

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Lewis Church

Plus Page written by Lewis Church

Get Your ALL ACCESS Shop Pass here →

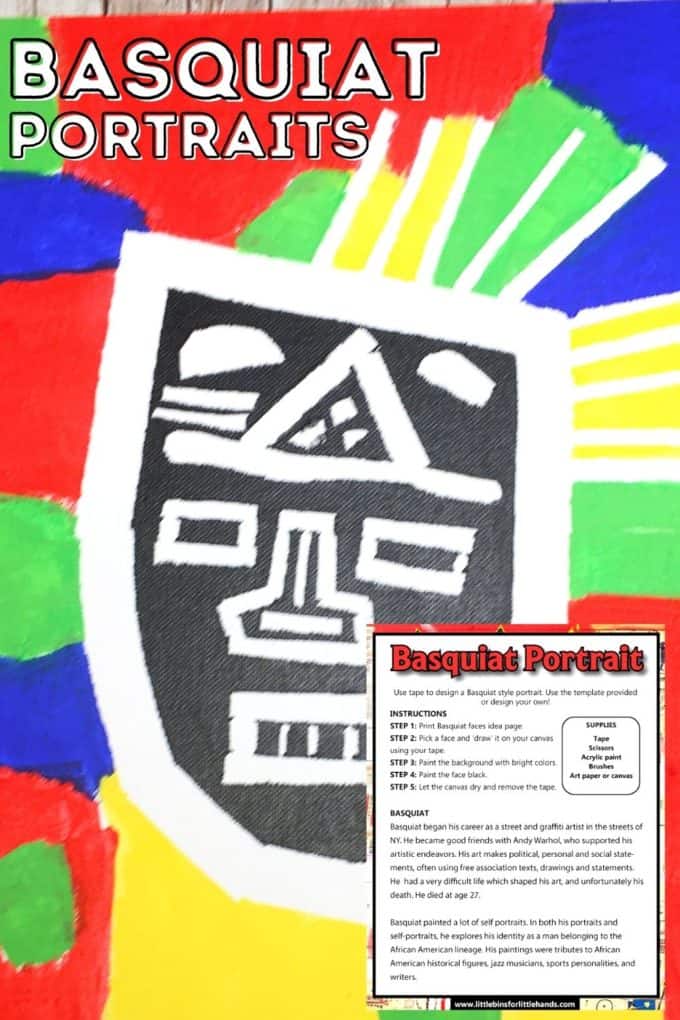

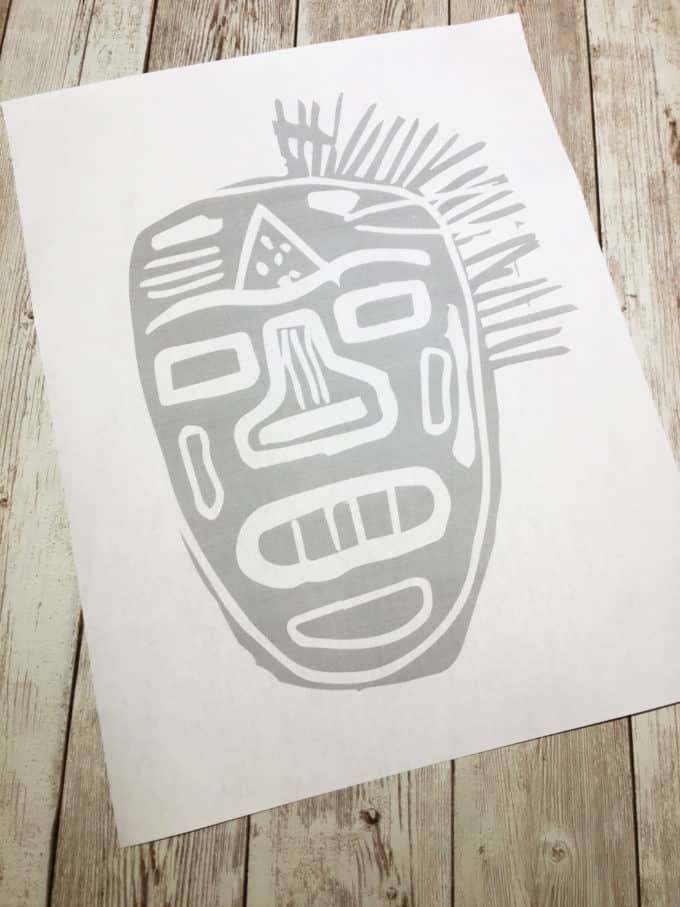

Basquiat Self Portraits Art Project

Create your own funky and colorful self portrait inspired by famous artist , Jean-Michel Basquiat! Basquiat art for kids is also a great way to explore mixed media art with kiddos of all ages. All you need are paints, a sheet of art paper, and some tape to make your own Basquiat art!

BASQUIAT FOR KIDS

Jean-Michel Basquiat began his career as a street and graffiti artist on the streets of New York. He became good friends with famous artist, Andy Warhol, who supported his artistic endeavors. Basquiat’s art often makes political, personal and social statements, using free association texts, drawings and statements. He had a very difficult life which shaped his art, and unfortunately he died aged 27.

Basquiat painted a lot of self portraits. In both his portraits and self portraits, he explores his identity as a man with African-American lineage. His paintings were tributes to African-American historical figures, jazz musicians, sports personalities and writers.

Be inspired by Basquiat’s art, and create your own self portrait with tape and our free Basquiat printable below. Let’s get started!

CLICK HERE TO GRAB YOUR FREE ART PROJECT!

BASQUIAT SELF PORTRAITS

- Acrylic paint

- Art paper or canvas

INSTRUCTIONS:

STEP 1. Print the Basquiat faces ideas page or create your own design.

STEP 2. Pick a face and “draw” it on your canvas or art paper using pieces of tape.

STEP 3. Paint the background with assorted bright colors.

STEP 4. Paint the face black.

STEP 5. Let the paint dry and then remove the tape to reveal your own Basquiat self portrait.

MORE FUN ART ACTIVITIES

Subscribe to receive a free 5-Day STEM Challenge Guide

~ projects to try now ~.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players , 1983, acrylic and oil stick on three canvas panels mounted on wood supports, 243.8 x 190.5 cm ( The Broad Art Foundation ) © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1983 painting Horn Players shows us all the main stylistic features we have come to expect from this renowned American artist. In addition to half-length portraits on the left and right panels of this triptych (a painting consisting of three joined panels), the artist has included several drawings and words—many of which Basquiat drew and then crossed out. On each panel we also notice large swaths of white paint, which seem to simultaneously highlight the black background and obscure the drawings and/or words beneath. Most notable perhaps is the preponderance of repeated words like “DIZZY,” “ORNITHOLOGY,” “PREE” and “TEETH” that the artist has scattered across all three panels of this work.

Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

Despite the seeming disorder of the composition, however, it is clear that the main subjects of Horn Players are two famous jazz musicians—the saxophonist Charlie Parker and the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who Basquiat has depicted in both linguistic and visual portraits. On the left of the canvas, the artist has drawn the figure of Parker, holding his saxophone which emits several hot pink musical notes and distorted waves of sound. We see Dizzy Gillespie in the right panel, who holds a silent instrument alongside his torso. The words “DOH SHOO DE OBEE” that float to the left of the figure’s head call to mind the scat (wordless improvisational) singing Gillespie often performed onstage.

“CHAN,” “ORNITHOLOGY,” and “PREE,” Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players (detail), 1983, acrylic and oil stick on three canvas panels mounted on wood supports, 243.8 x 190.5 cm ( The Broad Art Foundation ) © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Many of the words Basquiat has written on the canvas relate specifically to Charlie Parker, but they make sense only for those viewers with some knowledge of the musician’s life. For example, the literal meaning of “ORNITHOLOGY” is “the study of birds,” but this is also the title of a famous composition by Parker, who named the tune (first recorded in 1946) in reference to his own nickname “Bird.” The words “PREE” and “CHAN” that we see written above and below the saxophonist’s portrait refer to Parker’s infant daughter and common-law wife, respectively.

Jean-Michel Basquiat posing next to SAMO graffiti

Basquiat and wordplay

This kind of wordplay is a characteristic that extends across most of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work. One of the most recognizable features of the artist’s more than 2000 paintings and drawings is the overwhelming abundance of written words on the canvas. The art historian Robert Farris Thompson once declared: “It’s as if he were dripping letters.” [1] Before his success as a painter, Basquiat was famous for writing on the walls of lower Manhattan as a teenager when he and a high school friend, Al Diaz, left cryptic messages in spray paint under the name “SAMO” (an acronym for “Same Old Shit”) from 1977 until 1979.

As SAMO, Basquiat and Diaz wrote maxims, jokes, and prophecies in marker and spray paint on subway trains throughout New York City (particularly the “D” train, which ran between downtown Manhattan and Basquiat’s home in Brooklyn), as well as on the walls and sidewalks in the SoHo and Tribeca neighborhoods. Many of the locations where SAMO writings were to be found were in close proximity to prominent art galleries. Combined with these strategic positions, phrases like “SAMO AS AN END TO PLAYING ART” or “SAMO FOR THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE” presented the “SAMO” persona as outside the commercial art world and critical of it. In fact, even after relinquishing the SAMO persona and emerging to the art world as Jean-Michel Basquiat, the artist remained an outsider to the mainstream art world, despite his meteoric rise on the art auction block.

“The Black Picasso”

Basquiat went from “SAMO” to commercial success at warp speed in the early 1980s. He first exhibited (still under the name SAMO) at the Times Square Show—an exhibition in June 1980 that marked the genesis of the eighties art movement. He was later invited to exhibit in New York/New Wave , a group show of sixteen hundred works by 119 artists that opened at P.S. 1 on Valentine’s Day. The show was affectionately called “The Armory Show” of the 1980s.

Almost immediately afterward, the young Basquiat (at this point just 20 years old) was invited to exhibit in his first solo show in Modena, Italy. The gallerist Annina Nosei, who showed more established artists like David Salle and Richard Prince, agreed to represent Basquiat, who had a one-man show at her gallery the next year. That same year, Basquiat had exhibitions in Los Angeles, Zurich, Rome, and Rotterdam and became the youngest artist invited to participate in Documenta 7. By 1983 the average sale price of Basquiat’s work had increased by 600 percent, and his popularity (both in the auction house and in popular culture) persists even today. You can buy his images on shirts and hats from popular retail outlets and his large paintings sell at auction for more than $20 million.

Based on his meteoric success, critics referred to Jean-Michel Basquiat as “the Black Picasso.” The nickname was complicated for Basquiat, who never embraced it, but was nevertheless concerned with his own place within art history. He often relied on textbooks and other sources for his visual material; most biographies of the artist note his reliance on the medical textbook Gray’s Anatomy (a gift from the artist’s mother when Basquiat was hospitalized as a child) for the anatomical drawings and references we see on many of his surfaces. Basquiat also appropriated the work of Leonardo , Édouard Manet , and Pablo Picasso into his own compositions. These appropriations were in part an homage to the great painters Basquiat admired, but they also were a way for Basquiat to rewrite art history and insert himself into the canon.

Pablo Picasso, Three Musicians , 1921, oil on canvas, 200.7 x 222.9 cm ( The Museum of Modern Art )

Looking again at Horn Players , for example, reveals several connections to Picasso’s Three Musicians . Basquiat’s use of the triptych format—a popular device for the artist in this period—echoes the triple subjects of the Picasso image. The figure of Parker in Basquiat’s composition is also reproduced in the same position as the standing figure (playing the clarinet) in Picasso’s work.

Left: Pablo Picasso, Three Musicians (detail), 1921, oil on canvas, 200.7 x 222.9 cm ( The Museum of Modern Art ); right: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players (detail), 1983, acrylic and oil stick on three canvas panels mounted on wood supports, 243.8 x 190.5 cm ( The Broad Art Foundation ) © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

The central panel of Basquiat’s canvas, which does not show a portrait of an identifiable musician like the other two panels, but instead a distorted head with roughly outlined features, suddenly comes into focus via its comparison with Three Musicians . Here Picasso references in paint, his earlier experiments with paper collage especially in rendering the face and head of his central figure, whose jawline dramatically extends beyond what is anatomically possible to create an abstract, bulbous shape. Basquiat’s central figure bears a similar protrusion—this time from the top of the head—which he fills in with hatch marks that are suggestive of the patterning of Picasso’s “collaged” paper. Once again, Basquiat seems to be speaking in code. This time, we are being asked not only to draw upon our knowledge of music history but of modern painting to fully understand his work.

Basquiat’s musicians

Musicians were a popular subject for Basquiat, who himself played briefly in a noise band called Gray—likely a reference to the Gray’s Anatomy textbook. Jazz musicians began to appear in the artist’s paintings around 1982; references to jazz musicians or recordings appear in more than thirty large-format paintings and twenty works on paper. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie are the two musicians who appear most frequently, both as figures in the paintings and through linguistic references to their work. The artist painted canvases with figures playing the trumpet, the saxophone, and the drums. He also devoted several canvases to replicating the labels of jazz records or the discographies of musicians.

Many scholars have connected Basquiat’s interest in jazz to a larger investment in African American popular culture (for example, he also painted famous African American athletes) but an alternative explanation is that the young Basquiat looked to jazz music for inspiration and for instruction, much in the same way that he looked to the modern masters of painting. Parker, Gillespie, and the other musicians of the bebop era infamously appropriated both the harmonic structures of jazz standards, using them as a structure for their own songs, and repeated similar note patterns across several improvisations. Basquiat used similar techniques of appropriation throughout his career as a painter.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson and Renee Ricard, Jean-Michel Basquiat (Gagosian Gallery, 2015).

Bibliography

Basquiat from The Art Story

New York/New Wave exhibition at MoMA PS1 in 1981

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy . We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

LINES, CHAPTERS, AND VERSES: THE ART OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

- Share on Facebook

- Show more sharing options

- Share on WhatsApp

- Print This Page

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share to Flipboard

- Submit to Reddit

- Post to Tumblr

Basquiat’s brand of action painting is not of the type where the movements of the artist’s hand, guided by the impulse of the moment, tend to erase or soften the parts already there. His power lies in bringing a variety of elements into dynamic contact, in leaving be what comes up, in allowing an energetic coexistence. Over time, over a body of work, these coexisting shapes come to compose a kind of family of signs. Favorite images or words—teeth, for example, or the copyright sign—are repeated and amplified from painting to painting to such an extent that they become epic. The oeuvre as a whole comes to involve more than the subjectivity of a single individual’s choices: it becomes a witnessing of major themes of our time. Basquiat’s witnessing, then, is both private and general; his paintings function like a mirror, reflecting what is around them. But the mirror is not passive—it does not reflect indiscriminately. Perhaps the work is less like a mirror than like an eye and a voice: as eye, it observes and interprets life, collecting selected items and organizing them within itself; thus organized, it becomes voice, a clear utterance expressing what has been seen. As voice, it approaches the aural, and many Basquiat paintings feature words that sound in one’s head as one looks at them. Or they evoke a state of music, both imagistically (a picture with a pair of drums and a cymbal is titled Max Roach , 1984, after the great jazz drummer) and through more words, for example the cadenced fall of song titles and names of musicians from consummate recording dates in Discography (One) and (Two) , both 1983. Urgent sound seems to want to break out of or be summoned by these canvases, and the artist has accompanied his painting by work in music, as a performer, dj, and record producer.

Basquiat seems to see in terms of details from which one can reconstruct or reimagine the system they came from, as geneticists can reconstruct a body from a cell. Sometimes a few forms dominate a composition, attracting the eye from one to the other, taking it across, up, and down the surface. Sometimes these forms are different patches of color, sometimes they’re particularly immediate lines marking out a strong shape such as a head (which usually feels more like a mask than a face), or perhaps they are words with a striking meaning—at any rate, they are the first thing to attract the viewer’s eye. Then a steady parade of surprises may follow as other elements or shapes emerge from the field—collaged papers, figures, smaller groups of words, and so forth—summoned in a dialogue with what is different from themselves. This is the context, too, in which to approach Basquiat’s 1984 collaborations with Andy Warhol and Francesco Clemente—as a production of collective pictures wherein each separate identity asserts itself, whether actively or, paradoxically, passively, each one giving to, taking from, affecting the other.

Basquiat’s line does not seem to me an expressionistic one, for it is a line with a characteristic distinguishable in these times: its attitude is not emotional but critical. A paradigmatic phrase inscribed in one of his paintings— K , 1982—is “disease culture,” and sickness is certainly one of the artist’s themes. Yet the line is proof, for him and for us, of the elasticity and clarity of seeing.

Demosthenes Davvetas is a writer who lives in Paris. He is the author of a number of books, including the novels Oreste and Das Lied Penelopes; most recently he published a conversation between himself and Lucas Samaras, Dialog/dialogue: Lucas Samaras/Demosthenes Davvetas (Zurich: Elisabeth Kaufmann, 1986). He contributes to the daily newspaper Libération.

Most Popular

You may also like.

- United States.

- United Kingdom

- Netherlands

- Salvador Dalí

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Alphonse Mucha

- Claude Monet

- Andy Warhol

- Investing in Art

Breaking Boundaries: The Art Style of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat , an artist whose work continues to resonate and inspire, was a unique figure in the world of modern art. His artistic journey, deeply intertwined with the bustling street culture of New York City in the late 70s and 80s, marked a significant departure from conventional art forms of the time. In this exploration of Basquiat’s art style, we’ll delve into the core elements that make his work stand out, reflecting his individuality, cultural heritage, and the socio-political landscape he navigated.

Table of Contents

The Neo-Expressionism Movement

Basquiat emerged as a pivotal figure in the Neo-Expressionism movement , a style that gained prominence in the late 20th century. Characterized by its raw, emotive, and often unsettling imagery, Neo-Expressionism was a reaction against the conceptual and minimalistic art that preceded it. This movement sought to bring back the human figure, personal emotion, and narrative into the art world. Basquiat’s work epitomizes this with its focus on figurative art and its visceral, emotionally charged nature.

Primitivism and Rawness

One of the most distinctive traits of Basquiat’s art is its primitivist aesthetic. This style often includes a raw, almost childlike quality, echoing the art of indigenous people and ancient civilizations. Basquiat employed a kind of controlled chaos in his work, using a combination of crude, naive doodles and more sophisticated, painterly techniques. This juxtaposition created a powerful visual language that communicated complex themes of identity, history, and socio-political issues.

Text and Symbolism

Text played a crucial role in Basquiat’s art, often interwoven with imagery to create a dense tapestry of meaning. His use of words ranged from single letters and numbers to phrases and cryptic messages. This textual element added a layer of depth to his work, inviting viewers to engage with the painting not just visually but intellectually. The words and symbols in Basquiat’s paintings often referenced his personal experiences, historical figures, and issues of race and class.

Anatomy and Human Figures

Basquiat’s fascination with anatomy is evident in many of his works. Influenced by his early interest in Gray’s Anatomy (a book he was given during a hospital stay), he frequently incorporated skeletal figures and anatomical diagrams into his art. These elements served as metaphors for deeper themes, such as vulnerability, mortality, and the human condition.

The depiction of human figures and faces in his work is raw and expressive, often bordering on the grotesque. This representation underscores the intensity and urgency of Basquiat’s message, reflecting his commentary on humanity and its complexities.

Color and Contrast

Color is another significant aspect of Basquiat’s style. He often used a vibrant palette to create striking contrasts in his works. Bold colors were juxtaposed with black or white spaces, creating a dynamic visual rhythm. His use of color was not just aesthetic but also symbolic, conveying emotions and highlighting the critical themes of his paintings.

The intensity of the hues often served to underscore the powerful messages about race, poverty, and inequality that Basquiat sought to convey.

Integration of Street Art

Basquiat’s roots in graffiti and street art profoundly influenced his style. Starting as a street artist under the pseudonym “ SAMO ,” he brought the spontaneity and rawness of the streets into the fine art gallery. His paintings often retained the energy and immediacy of graffiti, with loose, gestural lines and an impromptu, improvisational feel.

This integration of street art into his work challenged traditional boundaries and definitions of what constituted fine art.

Layering and Collage

Basquiat frequently used a technique of layering and collage in his paintings. He often combined paint with found objects and mixed media, creating textured, multidimensional works. This layering not only added physical depth to his paintings but also imbued them with a rich array of meanings and references. The collage-like approach mirrored the complexity of his themes, reflecting a world full of contradictions, conflicts, and diverse influences.

Cultural References and Personal Iconography

Basquiat’s work is replete with cultural references and personal iconography that speak to his heritage, influences, and the world he inhabited.

He drew inspiration from a wide array of sources, including African art, jazz music, Greek mythology, and contemporary pop culture. This eclectic mix of influences was reflected in the symbols and motifs that recur throughout his work, such as crowns, masks, and heroic figures. These elements served not only as personal markers but also as commentary on broader cultural and historical themes.

Political and Social Commentary

A significant aspect of Basquiat’s art is its potent political and social commentary. He tackled issues such as racism, inequality, and the struggles of marginalized communities. His paintings often portrayed black heroes and figures, challenging the predominantly white narrative of art history and contemporary culture. Basquiat’s art was a powerful platform for expressing his views on social injustices, and his bold, confrontational style served to amplify his message.

Your thoughts matter to us! We’re eager to hear your take on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s distinctive art style and which of his works resonate with you the most.

Do you find his raw, emotive expression captivating, or are you drawn to his bold use of color and symbolism? Share your perspectives and favorite pieces in the comments below. And don’t forget, our blog is a treasure trove of insights on the artistic styles of other legendary figures like Picasso , Dalí , and Da Vinci , among many others. Dive into our rich collection of articles to explore and compare the unique artistic languages of these great masters!”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Current ye ignore me @r *

Leave this field empty

Related Posts

Rembrandt’s Artistic Mastery: A Journey Through His Unique Art Style

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, a towering figure in the world of art, is celebrated not just for his unparalleled skill…

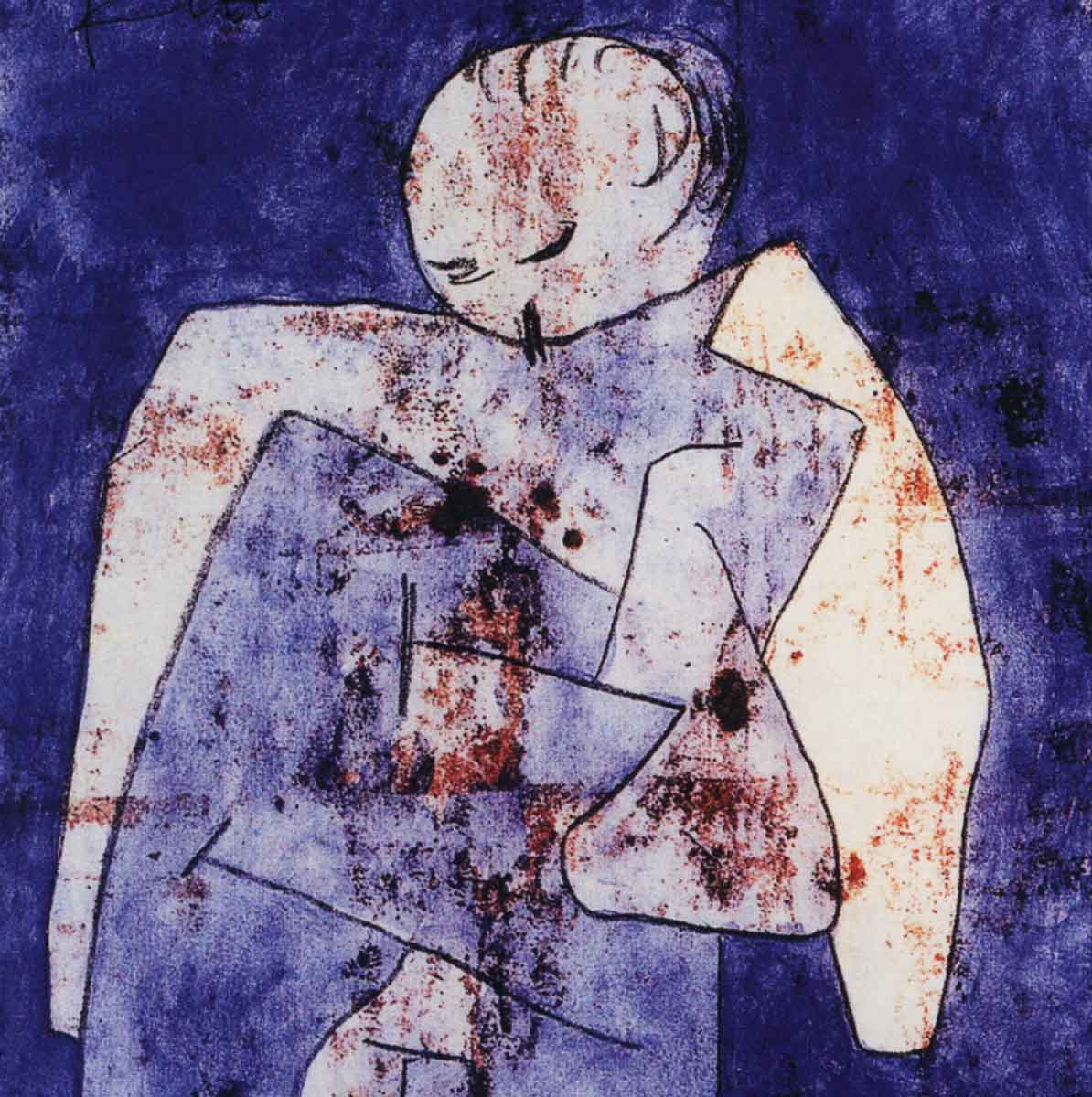

Paul Klee’s Art Style: The Intersection of Expressionism and Abstraction

Paul Klee, a Swiss-German artist, is widely celebrated for his unique artistic style that skillfully intertwines elements of Expressionism, Surrealism,…

The Allure of Art Nouveau: Exploring Gustav Klimt’s Unique Art Style

Gustav Klimt, a mastermind of symbolism and one of the most prominent members of the Vienna Secession movement, revolutionized the…

Art Teacher Smile

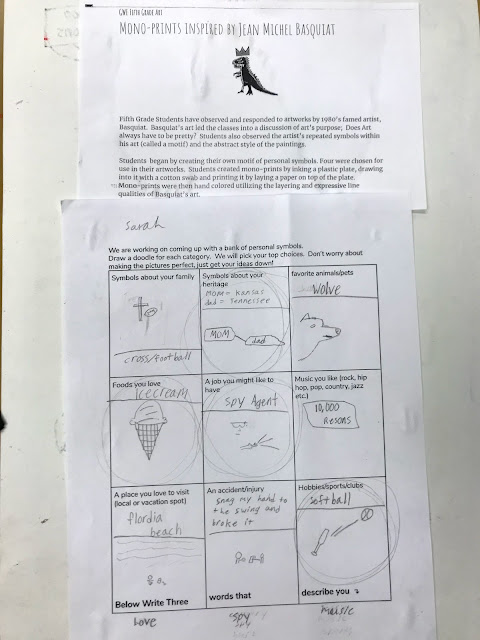

Search this blog, highschool art room: instruction and providing choice to students, basquiat monoprints: personal symbols and creative expression with 5th graders, to encourage creative expression within a guided project can be a challenge for us art teachers. with my fifth graders, i find they’re at an interesting point in their creative expression. they can be very good at consciously synthesizing their observations on another artist’s work with their own ideas. i chose to tackle the work jean-michel basquiat with my fifth graders this past school year and really work with them on the idea of art as emotional expression..

He’s an artist I’ve always wanted to delve into with my elementary students, but had shied away from in the past. I think Basquiat’s work can be very accessible to young artists, but there are certainly elements of his life that are better suited to discuss with older elementary students or middle school age students. The work is both simple and complex and of course, rich in personal meaning to the artist.

Thinking about how to get into Basquiat’s work with my students had me mulling over how to create a lesson from this artist’s work with real and lasting meaning. I’ve found it easy to say, ‘ Art helps you express your feelings!’ . However, designing a lesson that guides students through the process of making a piece focused on personal expression is more challenging.

My goals were:

A class discussion on art as expression. (whew that’s a heavy one maybe we’ll just dip our toes into that.), for students to be able to identify and discuss the style of basquiat’s art, to recognize other influences in basquiat’s art and the overall idea that art can be inspired by many sources high and low. (picasso, graffiti), for student-artists to create and utilize their own personal symbols in their artwork, to create art as an expression of feeling or what student-artists feel is their place in the world, to use color and line in a style that points back to basquiat’s artworks.

I had seen the results of a lesson from Don Masse on Basquiat via Instagram a few months earlier. So I went in search of more info on his approach. You can find his blog post on Basquiat inspired chalk pastel drawings with second graders right here: http://www.shinebritezamorano.com/2018/01/making-meaning-with-jean-michel.html

And talk about one artist being inspired by another! Or in this case teacher… his lesson info was a great jumping off point for me. Thank you, Don! Please take a moment to hop over to shinebritezamorano and follow him on instagram, @shinebritezamorano. In fact, I decided not to reinvent the wheel and use the same essential question and Basquiat artworks as discussion pieces for an introduction to the artist.

I created a google slides presentation where my essential question was the first thing students would see when they came in the room.

Does Art always have to be pretty?

And the follow up question- if it’s not nice to look at, then why are artists making it.

The students all know to say, no, art doesn’t have to be pretty, but the discussion you can get out of fifth graders past that point is very interesting. I want to mention here that this past year I was teaching an interim position at a small title 1 school. Many of the students (as can be true in any school) had challenging home lives past and present. So it was important to me to introduce an artist like Basquiat, who had many struggles throughout his young life and used his art as the ultimate method of expression. To guide my students through the idea that they could use art this same way, as an expression of not only the beautiful parts of their life, but the ugly parts as well, is my honor as an educator.

Students saw photos of the artist at work and learned a little about his life on this first day. I save more on that for a later class. As we examined the three paintings for discussion, we looked for

- Overlapping

- Expressive line