How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

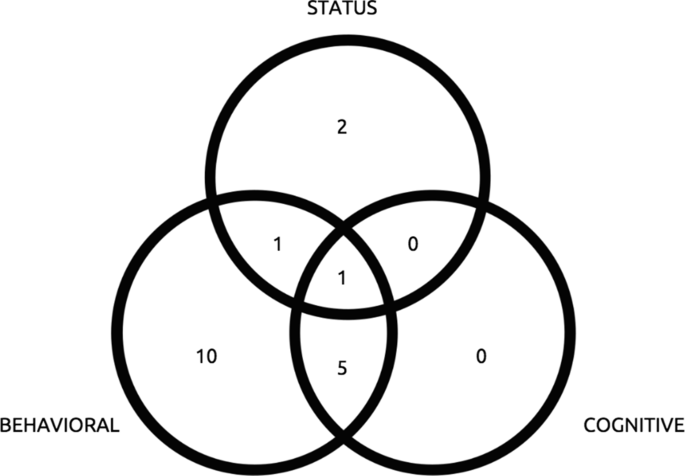

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

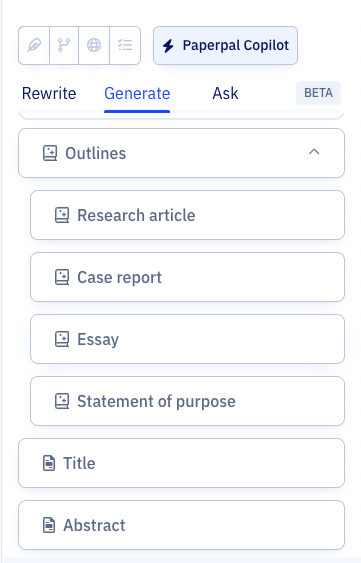

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples.

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

As the saying goes, You only get one chance at a first impression, and research papers are no exception. It’s the first thing people read, so a solid research paper introduction should lay the groundwork for the rest of the paper, answer the early questions a reader has, and make a personal impact—all while being as succinct as possible.

It’s not always easy knowing how to write introductions for research papers, and sometimes they can be the hardest part of the whole paper. So in this guide, we’ll explain everything you need to know, discussing what to include in introductions to research papers and sharing some expert tips so you can do it well.

Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What is a research paper introduction?

A research paper introduction is an essential part of academic writing that explains the paper’s main topic and prepares the reader for the rest of the paper. After reading the introduction, the reader should know what the paper is about, what point it’s trying to make, and why it matters.

For scientific and data-heavy research papers, the introduction has a few more formal requirements, such as briefly describing how the research was conducted. We’ll explain more on those in the next section.

The role of the research paper introduction is to make sure the reader understands all the necessary preliminary information before they encounter the discoveries presented in the body of the research paper. Learning how to write an introduction is an important part of knowing how to write a research paper .

How long should a research paper introduction be?

There are no firm rules on how long a research paper introduction should be. The only guideline is that the length of the introduction should be commensurate with the length of the entire paper. Very long papers may have an introduction that spans more than one page, while short papers can have an introduction of only a paragraph.

What to include in introductions to research papers

Generally speaking, a good research paper introduction includes these parts:

1 Thesis statement

2 Background context

3 Niche (research gap)

4 Relevance (how the paper fills that gap)

5 Rationale and motivation

First, a thesis statement is a single sentence that summarizes the main topic of your paper. The thesis statement establishes the scope of the paper, defining what will and won’t be discussed.

You also want to provide some background , summarizing what the reader needs to know before you present new information. This includes a brief history of the topic and any previous research or writings that your own ideas are built on.

In academic writing, it’s good to explain the paper’s niche, the area of research that your paper contributes to. In formal research papers, you should describe the research gap, a particular area of a topic that either has not been researched or has inadequate research. Informal research papers without original research don’t need to worry much about this.

After establishing the niche, next you explain how your research paper fills that niche—in other words, your paper’s relevance. Why is this paper important? What does it teach us? In a formal research paper introduction, you explain how your paper and research attempt to close the research gap and add the missing data.

Last, mention the rationale and motivation for why you chose this topic for your research. This can be either a personal choice or a practical one, such as researching a topic that urgently needs new information. You can also mention what you hope your research accomplishes—your goals—to round out your motivations.

What to include in introductions to scientific research papers

Scientific research papers, especially if they present original research and new data, have some additional requirements for their introduction:

- Methodology

- Research question or hypothesis

- Literature review (previous research and current literature)

The methodology describes how you conducted your research, including which tools you used or the procedure for your tests. This is to validate your findings, so readers know your data comes from a reliable source.

A research question or hypothesis acts similarly to the thesis statement. A research question is simply the question your research aims to answer, while a hypothesis is your prediction, made before the experiments begin, of what the research will yield. By the end of the paper, your hypothesis will be proven right or wrong.

Given the nature of scientific papers, the background context is more detailed than in other research papers. A literature review explains all the research on your particular topic that’s relevant to your paper. You outline the major writings and other research papers your own research is based on, and discuss any problems or biases those writings have that may undermine their findings.

The literature review is the perfect place for establishing the research gap. Here you can explain in your own words why the current research on your topic is insufficient, and why your own research serves to fill this gap.

If you’re writing a casual paper that relies only on existing research, you don’t need to worry about these.

How to write introductions for research papers

1 use the cars model.

The English scientist John Swales devised a method known as the CARS model to “Create A Research Space” in introductions. Although it’s aimed at scientific papers, this simple, three-step structure can be used to outline any research paper introduction.

- Establishing a territory : Explain the background context of your topic, including previous research.

- Establishing a niche : Explain that one area of your topic is missing information or that the current research is inadequate.

- Occupying a niche : Explain how your research “fills in” that missing information from your topic.

Swales then suggests stating the outcome of the research and previewing the structure of the rest of the paper, although these don’t apply to all research papers, particularly informal ones.

2 Start broad and narrow down

One common mistake in writing research paper introductions is to try fitting in everything all at once. Instead, pace yourself and present the information piece by piece in the most logical order for the reader to understand. Generally that means starting broad with the big picture, and then gradually getting more specific with the details.

For research paper introductions, you want to present an overview of the topic first, and then zero in on your particular paper. This “funnel” structure naturally includes all the necessary parts of what to include in research paper introductions, from background context to the niche or research gap and finally the relevance.

3 Be concise

Introductions aren’t supposed to be long or detailed; they’re more like warm-up acts. Introductions are better when they cut straight to the point—save the details for the body of the paper, where they belong.

The most important point about introductions is that they’re clear and comprehensible. Wordy writing can be distracting and even make your point more confusing, so remove unnecessary words and try to phrase things in simple terms that anyone can understand.

4 Consider narrative style

Although not always suitable for formal papers, using a narrative style in your research paper introduction can help immensely in engaging your reader and “ hooking ” them emotionally. In fact, a 2016 study showed that, in certain papers, using narrative strategies actually improves how often they’re cited in other papers.

A narrative style involves making the paper more personal in order to appeal to the reader’s emotions. Strategies include:

- Using first-person pronouns ( I, we, my, our ) to establish yourself as the narrator

- Describing emotions and feelings in the text

- Setting the scene; describing the time and place of key events to help the reader imagine them

- Appealing to the reader’s morality, sympathy, or urgency as a persuasion tactic

Again, this style won’t work for all research paper introductions, especially those for scientific research. However, for more casual research papers—and especially essays—this style can make your writing more entertaining or at the very least interesting, perfect for raising your reader’s enthusiasm right at the start of your paper.

5 Write your research paper introduction last

Your introduction may come first in a research paper, but a common tip is to wait on writing it until everything else is already written. This makes it easier to summarize your paper, because at that point you know everything you’re going to say. It also removes the urge to include everything in the introduction because you don’t want to forget anything.

Furthermore, it’s especially helpful to write your introduction after your research paper conclusion . A research paper’s introduction and conclusion share similar themes, and often mirror each other’s structure. Writing the conclusion is usually easier, too, thanks to the momentum from writing the rest of the paper, and that conclusion can help guide you in writing your introduction.

Research paper introduction FAQs

For academic writing like research papers, an introduction has to explain the topic, establish the necessary background context, and prepare the reader for the rest of the paper. In scientific research papers, the introduction also addresses the methodology and describes the current research for that topic.

What do you include in an introduction to a research paper?

A good research paper introduction includes:

- Thesis statement

- Background context

- Niche (research gap)

- Relevance (how it fills that gap)

- Rationale and motivation

Scientific research papers with original data should also include the methodology, a literature review, and possibly a research question or hypothesis.

How do you write an introduction for a research paper?

There are a few important guidelines to remember when writing a research paper. Start with a broad overview of the topic and gradually get more specific with the details and how your paper relates. Be sure to keep your introduction as succinct as possible, as you don’t want it to be too long. Some people find it’s easier to write the introduction last, after the rest of the paper is finished.

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper . It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Paper Writing Guides

Research Paper Introduction

Last updated on: Aug 22, 2024

5 Steps to Write an Excellent Research Paper Introduction - With Examples & Tips

By: Betty P.

11 min read

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Jan 12, 2024

When it comes to research papers, an introduction is the first impression that you make on your readers, so it’s important to make it clear and engaging.

When writing a research paper, the introduction presents a unique challenge: A research paper introduction has to be more than just engaging. The main point of the introduction section is to present your research topic clearly and comprehensively. This becomes quite difficult if you don’t know what to include and how to structure it.

This blog will guide you through the process of writing an introduction for a research paper step-by-step. By following these steps, you will be able to write an introduction that sets the tone for your research paper and prepares your readers for what they will learn from it.

Let’s get into it!

On this Page

The Purpose of a Research Paper Introduction

The introduction is the first part of a research paper, where the topic is introduced, and some background and context are provided. As a writer, you need a research paper introduction that has four main goals:

- To inform your readers about the general subject of your paper and why it is important or relevant.

- To provide the necessary background information, your readers need to understand the topic.

- To establish your research question and thesis statement, which are the main points and arguments of your paper.

- To preview the main points and structure of your paper, which are the subtopics and evidence that you are going to present.

A research paper introduction is not just a summary of your paper, but a gateway to lead your readers into your specific topic. Through the introduction, you need to equip your readers with the necessary information for them to navigate and understand your research.

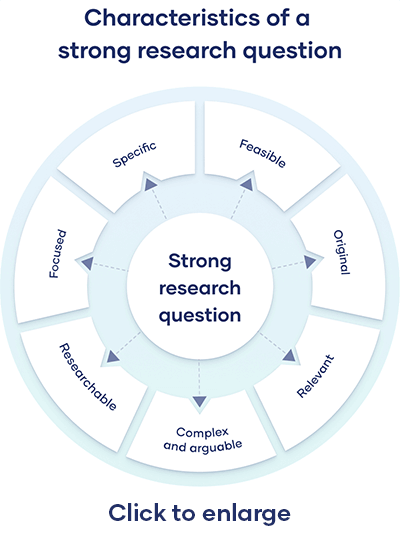

Characteristics of a Good Research Paper Introduction

Here are some qualities that your research paper introduction should possess:

- It should be clear and concise, avoiding unnecessary and irrelevant details.

- It should be engaging and interesting, using a hook or a catchy opening sentence to capture the attention of readers.

- It should follow a clear and logical structure and transition from one idea to another.

- It should be relevant and focused, addressing the specific purpose and scope of the paper

- It should convey the relevance or importance of the topic in light of existing research and discourse.

- It should present the writer’s own voice and original perspective on the topic.

5 Steps for Writing an Excellent Research Paper Introduction

Now that you know what a research paper introduction aims to achieve, let’s get into the steps that will help you fulfill your introduction goals effectively.

Writing your introduction step-by-step will ensure that you cover all the parts of the introduction in the research paper. These include presenting an engaging hook, providing background and context to your topic, presenting your main questions and objectives, and mentioning the structure.

Here are the steps you need to follow:

Step 1: Identify the Purpose and Scope of your Research Paper

Before you start writing your introduction, you need to have a clear idea of what your paper is about and what you want to achieve with it.

That is, before you can dive into writing, you should complete all the prewriting steps, which include:

- Defining your topic

- Craft specific research problems or questions

- Deciding the methods, techniques, and arguments that you will address in your paper.

- Finally, you should have a research paper outline, so that you can describe the structure at the end of the introduction.

Writing a good introduction will only become possible if you know your research through and through.

Step 2: Introduce the Topic with an Engaging Hook

The first step of writing a research paper introduction is to capture the attention and interest of your readers. You want to make your readers curious and motivated to read your paper.

You can do this by using a hook or a catchy opening sentence, such as a quote, a statistic, a question, a story, or a surprising fact. You can also use a rhetorical device, such as a contrast, a comparison, or a paradox, to create interest and intrigue.

Some points to keep in mind when crafting an engaging opening:

- Keep the hook strictly relevant to your topic.

- It should be directly related to the main premises of your research paper

Here’s an example of an engaging opening for a research paper:

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with more than 3.8 billion users worldwide as of 2020. |

Step 3: Provide some background information and context for your topic.

After you introduce your general subject, you need to give some background information and context for your topic.

This can include the history, significance, current state, or gaps of knowledge of your topic. The point of it is to provide the necessary and essential information readers need to know before getting into your main argument.

You should also explain why your topic is important or relevant for your field or audience. This will help the reader situate your research work within a larger academic discourse.

Let’s continue with the example above:

Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, allow users to create, share, and consume various types of content, such as text, images, videos, and audio. It also enables users to interact with others, form online communities, and express their opinions and emotions. However, social media use also has potential negative effects on mental health, such as increased stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and low self-esteem. Several studies have investigated the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes, but the results are inconsistent and inconclusive . Some studies have found positive associations, some have found negative associations, and some have found no associations or mixed effects. Moreover, most studies have focused on specific platforms, populations, or outcomes, and have used different methods and measures, making it difficult to compare and generalize the findings. |

Step 4: Present your research question & objectives

Your research question is the central question that you want to answer in your paper. All of your subsequent arguments revolve around it and build up to answer that question. Your research question should be clear, concise, and specific.

Moreover, they should also be debatable, meaning that they can be challenged or supported by evidence.

In addition to presenting your main questions in the introduction, you should also lay out your research objectives. That is, explain what you aim to achieve through this research in concrete and quantifiable terms.

Here is an example:

The aim of this paper is to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature on the impact of social media use on mental health. The primary question this paper attempts to answer is this: How does social media use affect mental health outcomes, such as stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and self-esteem, among adults? |

Step 5: Preview the main points and structure of your paper

After you present your research question and thesis statement, you need to preview the main points and structure of your paper.

This means that you need to briefly outline the subtopics that you will cover in your research paper. You should also indicate how you will organize your paper, such as by chronological order, thematic order, or methodological order.

Let’s build upon the example from previous steps to show you how it’s done:

This paper will follow the PRISMA guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The paper will consist of four main sections: Literature Review, Methods, Results, and Discussion. The existing research on the topic will be discussed in the literature review section, along with the gaps that have been left unanswered. In the Methods section, the paper describes the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, quality assessment, and statistical analysis. In the Results section, the paper presents the descriptive and quantitative findings of the literature review and meta-analysis. Finally, the paper interprets and synthesizes the results in the Discussion section, and compares them with previous studies. |

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Here are a few research paper introduction examples that will help put the writing steps in perspective.

First, let us put together the introduction presented above step-by-step. Here’s the complete sample introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with more than 3.8 billion users worldwide as of 2020. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, allow users to create, share, and consume various types of content, such as text, images, videos, and audio. It also enables users to interact with others, form online communities, and express their opinions and emotions. However, social media use also has potential negative effects on mental health, such as increased stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and low self-esteem. Several studies have investigated the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes, but the results are inconsistent and inconclusive . Some studies have found positive associations, some have found negative associations, and some have found no associations or mixed effects. Moreover, most studies have focused on specific platforms, populations, or outcomes, and have used different methods and measures, making it difficult to compare and generalize the findings. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature on the impact of social media use on mental health. The research question is: How does social media use affect mental health outcomes, such as stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and self-esteem, among adults? This paper will follow the PRISMA guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The paper will consist of four main sections: Literature Review, Methods, Results, and Discussion. The existing research on the topic will be discussed in the literature review section, along with the gaps that have been left unanswered. In the Methods section, the paper describes the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, quality assessment, and statistical analysis. In the Results section, the paper presents the descriptive and quantitative findings of the literature review and meta-analysis. Finally, the paper interprets and synthesizes the results in the Discussion section, and compares them with previous studies. |

Check out these introductions as well:

Research papers introduction APA

Quantitative Research Introduction Example

Introduction for a Research Paper Sample

Craft Better Introductions With These Writing Tips

Following the steps and examples above will help you craft a strong and acceptable introduction. However, you can make it even better with the following tips.

- Create a Research Space (CARS model)

The CARS model is a framework that can help you structure your introduction, especially in STEM fields. It consists of three rhetorical steps that help you structure your introduction:

Step 1: Establish a research territory by explaining the general topic and its importance, relevance, or state of knowledge.

Step 2: Establish a niche by identifying a gap, problem, question, or challenge in the existing research on the topic.

Step 3: Occupy the niche by stating your research question, thesis statement, purpose, findings, and structure of your paper.

- Use a Funnel Approach

Start with a broad and general introduction of your topic, and then narrow it down to your specific research problem and thesis statement. This will help you to provide a clear and logical structure for your introduction.

- Tailor the Introduction According to the Type of Research

Specific parts of an introduction may vary with different kinds of research. For instance, in scientific research papers, you need to provide a hypothesis instead of research questions. Similarly, in some cases, you need to provide a problem statement or focus on a research problem.

Although the general structure of the introduction remains the same across various types and disciplines, remember that the content must be tailored accordingly. Always keep the conventions and standards of your particular field in mind when working on a research introduction.

- Write the Introduction at the End

Sometimes, it is easier to write the introduction after you have completed the main body and conclusion of your paper.

This way, you will have a clear overview of your paper and its main arguments, and you can tailor your introduction accordingly. You can also avoid repeating or contradicting yourself, and ensure that your introduction matches the tone and style of your paper.

Alternatively, you can write a draft introduction to start your paper. However, you still need to come back and polish this introduction after completing the paper.

- Revise and Edit your Introduction

After you finish writing your introduction, check it for any errors, inconsistencies, or gaps. Make sure that your introduction is coherent, concise, and complete. You can also ask for feedback from your peers, mentors, or professional editors.

Now that you have learned how to write an effective introduction, you are all set to start! With the help of the examples and tips above, you can make your introductions stand out.

Remember, writing a good introduction can help you make a lasting impression on your readers and motivate them to read your paper. So always write it with focus and follow the steps.

If you need more help with your research paper, you can contact MyPerfectPaper.net for professional assistance.

You can buy research papers that are affordable and can help you with any aspect of your research paper. Whether you need help with choosing a topic, writing an introduction, or any other step, we have a team of expert writers to help you out.

So get professional paper writing help today!

Betty is a freelance writer and researcher. She has a Masters in literature and enjoys providing writing services to her clients. Betty is an avid reader and loves learning new things. She has provided writing services to clients from all academic levels and related academic fields.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Writing an Effective Title for Your Research Paper - A Simple Guide

- 7 Steps for Starting a Research Paper Effectively

- How to Write a Research Paper - Steps, Tips & Examples

-13527.jpg)

People Also Read

- compare and contrast essay examples

- college essay topics

- narrative essay writing

- personal statement format

- informative speech outline

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- LEGAL Privacy Policy

© 2024 - All rights reserved

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Research Introduction

Last Updated: December 6, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 2,656,769 times.

The introduction to a research paper can be the most challenging part of the paper to write. The length of the introduction will vary depending on the type of research paper you are writing. An introduction should announce your topic, provide context and a rationale for your work, before stating your research questions and hypothesis. Well-written introductions set the tone for the paper, catch the reader's interest, and communicate the hypothesis or thesis statement.

Introducing the Topic of the Paper

- In scientific papers this is sometimes known as an "inverted triangle", where you start with the broadest material at the start, before zooming in on the specifics. [2] X Research source

- The sentence "Throughout the 20th century, our views of life on other planets have drastically changed" introduces a topic, but does so in broad terms.

- It provides the reader with an indication of the content of the essay and encourages them to read on.

- For example, if you were writing a paper about the behaviour of mice when exposed to a particular substance, you would include the word "mice", and the scientific name of the relevant compound in the first sentences.

- If you were writing a history paper about the impact of the First World War on gender relations in Britain, you should mention those key words in your first few lines.

- This is especially important if you are attempting to develop a new conceptualization that uses language and terminology your readers may be unfamiliar with.

- If you use an anecdote ensure that is short and highly relevant for your research. It has to function in the same way as an alternative opening, namely to announce the topic of your research paper to your reader.

- For example, if you were writing a sociology paper about re-offending rates among young offenders, you could include a brief story of one person whose story reflects and introduces your topic.

- This kind of approach is generally not appropriate for the introduction to a natural or physical sciences research paper where the writing conventions are different.

Establishing the Context for Your Paper

- It is important to be concise in the introduction, so provide an overview on recent developments in the primary research rather than a lengthy discussion.

- You can follow the "inverted triangle" principle to focus in from the broader themes to those to which you are making a direct contribution with your paper.

- A strong literature review presents important background information to your own research and indicates the importance of the field.

- By making clear reference to existing work you can demonstrate explicitly the specific contribution you are making to move the field forward.

- You can identify a gap in the existing scholarship and explain how you are addressing it and moving understanding forward.

- For example, if you are writing a scientific paper you could stress the merits of the experimental approach or models you have used.

- Stress what is novel in your research and the significance of your new approach, but don't give too much detail in the introduction.

- A stated rationale could be something like: "the study evaluates the previously unknown anti-inflammatory effects of a topical compound in order to evaluate its potential clinical uses".

Specifying Your Research Questions and Hypothesis

- The research question or questions generally come towards the end of the introduction, and should be concise and closely focused.

- The research question might recall some of the key words established in the first few sentences and the title of your paper.

- An example of a research question could be "what were the consequences of the North American Free Trade Agreement on the Mexican export economy?"

- This could be honed further to be specific by referring to a particular element of the Free Trade Agreement and the impact on a particular industry in Mexico, such as clothing manufacture.

- A good research question should shape a problem into a testable hypothesis.

- If possible try to avoid using the word "hypothesis" and rather make this implicit in your writing. This can make your writing appear less formulaic.

- In a scientific paper, giving a clear one-sentence overview of your results and their relation to your hypothesis makes the information clear and accessible. [10] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- An example of a hypothesis could be "mice deprived of food for the duration of the study were expected to become more lethargic than those fed normally".

- This is not always necessary and you should pay attention to the writing conventions in your discipline.

- In a natural sciences paper, for example, there is a fairly rigid structure which you will be following.

- A humanities or social science paper will most likely present more opportunities to deviate in how you structure your paper.

Research Introduction Help

Community Q&A

- Use your research papers' outline to help you decide what information to include when writing an introduction. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 1

- Consider drafting your introduction after you have already completed the rest of your research paper. Writing introductions last can help ensure that you don't leave out any major points. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Avoid emotional or sensational introductions; these can create distrust in the reader. Thanks Helpful 51 Not Helpful 12

- Generally avoid using personal pronouns in your introduction, such as "I," "me," "we," "us," "my," "mine," or "our." Thanks Helpful 32 Not Helpful 7

- Don't overwhelm the reader with an over-abundance of information. Keep the introduction as concise as possible by saving specific details for the body of your paper. Thanks Helpful 25 Not Helpful 14

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185916

- ↑ https://www.aresearchguide.com/inverted-pyramid-structure-in-writing.html

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/introduction

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/PlanResearchPaper.html

- ↑ https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/wac/writing-an-introduction-for-a-scientific-paper/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/planresearchpaper/

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178846/

About This Article

To introduce your research paper, use the first 1-2 sentences to describe your general topic, such as “women in World War I.” Include and define keywords, such as “gender relations,” to show your reader where you’re going. Mention previous research into the topic with a phrase like, “Others have studied…”, then transition into what your contribution will be and why it’s necessary. Finally, state the questions that your paper will address and propose your “answer” to them as your thesis statement. For more information from our English Ph.D. co-author about how to craft a strong hypothesis and thesis, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Abdulrahman Omar

Oct 5, 2018

Did this article help you?

May 9, 2021

Lavanya Gopakumar

Oct 1, 2016

Dengkai Zhang

May 14, 2018

Leslie Mae Cansana

Sep 22, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Starting Your Research Paper: Writing an Introductory Paragraph

- Choosing Your Topic

- Define Keywords

- Planning Your Paper

- Writing an Introductory Paragraph

The Dreaded Introductory Paragraph

Writing the introductory paragraph can be a frustrating and slow process -- but it doesn't have to be. If you planned your paper out, then most of the introductory paragraph is already written. Now you just need a beginning and an end.

| for writing thesis statements. |

Here's an introductory paragraph for a paper I wrote. I started the paper with a factoid, then presented each main point of my paper and then ended with my thesis statement.

Breakdown:

| 1st Sentence | I lead with a quick factoid about comics. | |

| 2nd & 3rd | These sentences define graphic novels and gives a brief history. This is also how the body of my paper starts. | |

| 4rd Sentence | This sentence introduces the current issue. See how I gave the history first and now give the current issue? That's flow. | |

| 5th Sentence | Since I was pro-graphic novels, I gave the opposing (con) side first. Remember if you're picking a side, you give the other side first and then your side. | |

| 6th Sentence | Now I can give my pro-graphic novel argument. | |

| 7th Sentence | This further expands my pro-graphic novel argument. | |

| 8th Sentence | This is my thesis statement. |

- << Previous: Planning Your Paper

- Last Updated: Feb 12, 2024 12:16 PM

- URL: https://libguides.astate.edu/papers

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Looking for research paper introduction examples? Quotes, anecdotes, questions, examples, and broad statements—all of them can be used successfully to write an introduction for a research paper. It’s instructive to see them in action, in the hands of skilled academic writers.

Let’s begin with David M. Kennedy’s superb history, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . Kennedy begins each chapter with a quote, followed by his text. The quote above chapter 1 shows President Hoover speaking in 1928 about America’s golden future. The text below it begins with the stock market collapse of 1929. It is a riveting account of just how wrong Hoover was. The text about the Depression is stronger because it contrasts so starkly with the optimistic quotation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

“We in America today are nearer the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.”—Herbert Hoover, August 11, 1928 Like an earthquake, the stock market crash of October 1929 cracked startlingly across the United States, the herald of a crisis that was to shake the American way of life to its foundations. The events of the ensuing decade opened a fissure across the landscape of American history no less gaping than that opened by the volley on Lexington Common in April 1775 or by the bombardment of Sumter on another April four score and six years later. (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); The ratcheting ticker machines in the autumn of 1929 did not merely record avalanching stock prices. In time they came also to symbolize the end of an era. (David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 10)

Kennedy has exciting, wrenching material to work with. John Mueller faces the exact opposite problem. In Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War , he is trying to explain why Great Powers have suddenly stopped fighting each other. For centuries they made war on each other with devastating regularity, killing millions in the process. But now, Mueller thinks, they have not just paused; they have stopped permanently. He is literally trying to explain why “nothing is happening now.” That may be an exciting topic intellectually, it may have great practical significance, but “nothing happened” is not a very promising subject for an exciting opening paragraph. Mueller manages to make it exciting and, at the same time, shows why it matters so much. Here’s his opening, aptly entitled “History’s Greatest Nonevent”:

On May 15, 1984, the major countries of the developed world had managed to remain at peace with each other for the longest continuous stretch of time since the days of the Roman Empire. If a significant battle in a war had been fought on that day, the press would have bristled with it. As usual, however, a landmark crossing in the history of peace caused no stir: the most prominent story in the New York Times that day concerned the saga of a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest. This book seeks to develop an explanation for what is probably the greatest nonevent in human history. (John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War . New York: Basic Books, 1989, p. 3)

In the space of a few sentences, Mueller sets up his puzzle and reveals its profound human significance. At the same time, he shows just how easy it is to miss this milestone in the buzz of daily events. Notice how concretely he does that. He doesn’t just say that the New York Times ignored this record setting peace. He offers telling details about what they covered instead: “a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest.” Likewise, David Kennedy immediately entangles us in concrete events: the stunning stock market crash of 1929. These are powerful openings that capture readers’ interests, establish puzzles, and launch narratives.

Sociologist James Coleman begins in a completely different way, by posing the basic questions he will study. His ambitious book, Foundations of Social Theory , develops a comprehensive theory of social life, so it is entirely appropriate for him to begin with some major questions. But he could just as easily have begun with a compelling story or anecdote. He includes many of them elsewhere in his book. His choice for the opening, though, is to state his major themes plainly and frame them as a paradox. Sociologists, he says, are interested in aggregate behavior—how people act in groups, organizations, or large numbers—yet they mostly examine individuals:

A central problem in social science is that of accounting for the function of some kind of social system. Yet in most social research, observations are not made on the system as a whole, but on some part of it. In fact, the natural unit of observation is the individual person… This has led to a widening gap between theory and research… (James S. Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990, pp. 1–2)

After expanding on this point, Coleman explains that he will not try to remedy the problem by looking solely at groups or aggregate-level data. That’s a false solution, he says, because aggregates don’t act; individuals do. So the real problem is to show the links between individual actions and aggregate outcomes, between the micro and the macro.

The major problem for explanations of system behavior based on actions and orientations at a level below that of the system [in this case, on individual-level actions] is that of moving from the lower level to the system level. This has been called the micro-to-macro problem, and it is pervasive throughout the social sciences. (Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory , p. 6)

Explaining how to deal with this “micro-to-macro problem” is the central issue of Coleman’s book, and he announces it at the beginning.

Coleman’s theory-driven opening stands at the opposite end of the spectrum from engaging stories or anecdotes, which are designed to lure the reader into the narrative and ease the path to a more analytic treatment later in the text. Take, for example, the opening sentences of Robert L. Herbert’s sweeping study Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society : “When Henry Tuckerman came to Paris in 1867, one of the thousands of Americans attracted there by the huge international exposition, he was bowled over by the extraordinary changes since his previous visit twenty years before.” (Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988, p. 1.) Herbert fills in the evocative details to set the stage for his analysis of the emerging Impressionist art movement and its connection to Parisian society and leisure in this period.

David Bromwich writes about Wordsworth, a poet so familiar to students of English literature that it is hard to see him afresh, before his great achievements, when he was just a young outsider starting to write. To draw us into Wordsworth’s early work, Bromwich wants us to set aside our entrenched images of the famous mature poet and see him as he was in the 1790s, as a beginning writer on the margins of society. He accomplishes this ambitious task in the opening sentences of Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth’s Poetry of the 1790s :

Wordsworth turned to poetry after the revolution to remind himself that he was still a human being. It was a curious solution, to a difficulty many would not have felt. The whole interest of his predicament is that he did feel it. Yet Wordsworth is now so established an eminence—his name so firmly fixed with readers as a moralist of self-trust emanating from complete self-security—that it may seem perverse to imagine him as a criminal seeking expiation. Still, that is a picture we get from The Borderers and, at a longer distance, from “Tintern Abbey.” (David Bromwich, Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth’s Poetry of the 1790s . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 1)

That’s a wonderful opening! Look at how much Bromwich accomplishes in just a few words. He not only prepares the way for analyzing Wordsworth’s early poetry; he juxtaposes the anguished young man who wrote it to the self-confident, distinguished figure he became—the eminent man we can’t help remembering as we read his early poetry.

Let us highlight a couple of other points in this passage because they illustrate some intelligent writing choices. First, look at the odd comma in this sentence: “It was a curious solution, to a difficulty many would not have felt.” Any standard grammar book would say that comma is wrong and should be omitted. Why did Bromwich insert it? Because he’s a fine writer, thinking of his sentence rhythm and the point he wants to make. The comma does exactly what it should. It makes us pause, breaking the sentence into two parts, each with an interesting point. One is that Wordsworth felt a difficulty others would not have; the other is that he solved it in a distinctive way. It would be easy for readers to glide over this double message, so Bromwich has inserted a speed bump to slow us down. Most of the time, you should follow grammatical rules, like those about commas, but you should bend them when it serves a good purpose. That’s what the writer does here.