Fact check: 'Homework' spelled backwards does not translate to 'child abuse' in Latin

The claim: 'Homework' spelled backward means 'child abuse' in Latin

Many words and phrases are known to have different meanings in other languages, and much of the English vocabulary is derived from Latin roots.

Some social media users are claiming that the word "homework" spelled backward has a meaning in the Latin language.

A Feb. 27 Instagram post with almost 18,000 likes features a screenshot of the Google search, "what is homework backwards." The result purportedly reads, "So basically 'Homework' spelled backwards is 'krowemoh' which in Latin translates to child abuse."

The same screenshot included in the Instagram meme also appears in several viral TikToks, and the hashtag #Krowemoh has more than 246,000 views on the platform .

The Google search screenshot that users have used to make the claim is taken from a March 7, 2013, viral post that has recently resurfaced on Twitter, where many users have shared similar versions of the claim.

"I knew that this homework was just a way to abuse children," one Twitter user wrote along with the claim on Jan. 24.

USA TODAY reached out to the Instagram user for comment.

Fact check: Altered image shows rhino horns, elephant tusks dyed pink to deter poaching

'Krowemoh' is not a Latin word

The word "krowemoh" does not exist in Latin. According to Google translate , child abuse in Latin is actually "puer abusus."

A search of "krowemoh" on online Latin - to-English dictionaries results in no matches.

The classical Latin alphabet consists of 23 characters, and the letter W is not one of them. In Latin, the letter U represented a W sound which could only occur only before a vowel, according to Dictionary.com .

European languages that use the Latin alphabet do not use the letters K and W, and they add letters with diacritical marks or pairs of letters that read as one sound, according to Britannica .

Get these in your inbox: We're fact-checking the news and sending it to your inbox. Sign up here to start receiving our newsletter.

The claim that "krowemoh" translates to "child abuse" in Latin was added in January to Urbandictionary.com , a crowdsourced online dictionary of slang words and phrases.

The Urban Dictionary definition of "krowemoh" makes a joke of the word and children having loads of homework assignments.

Fact check: Israel launching 'Green Pass' for COVID-19 vaccinated

Our rating: False

The claim that "homework" spelled backward translates to "child abuse" in Latin is FALSE, based on our research. "Krowemoh" does not exist in the Latin language and the letter W is not part of the Latin alphabet.

Our fact-check sources:

- Google Translate, accessed March 3, English to Latin, 'puer abusus'

- Latin Dictionary, accessed March 3, 'Krowemoh' search

- Latin-Dictionary.net, accessed March 3, 'Krowemoh' search Latin to English

- Latin-English Dictionary, accessed March 3, 'Krowemoh' search Latin to English

- Dictionary.com, accessed March 3, 'What Does the Letter 'U' Have to do with 'W'?'

- Britannica, accessed March 3, Latin alphabet

- Urban Dictionary, Jan. 6, 'Krowemoh'

Thank you for supporting our journalism. You can subscribe to our print edition, ad-free app or electronic newspaper replica here.

Our fact check work is supported in part by a grant from Facebook.

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics Training

- Ethics Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- IFCN Grants

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Does homework spelled backward translate to ‘child abuse’ in Latin?

Scrolling through social media recently, you may have come across the viral claim that the word “homework” spelled backward translates to “child abuse” in Latin. This claim has been everywhere lately, racking up thousands of views across Instagram , Twitter , Reddit and YouTube .

But is “krowemoh” really a Latin word, or just a random jumble of letters? Here’s how we fact-checked it.

Practice click restraint

Taking a closer look at the claim on YouTube. The video is a screen recording of the YouTuber doing a keyword search and clicking on the very first result from Urban Dictionary. Automatically clicking on the first result is not really a great technique for vetting information. Instead, practice a media literacy skill from the Stanford History Education Group called click restraint. This is a web-browsing tactic that involves scanning search results for better sources before deciding which website to visit. Spending a couple of extra seconds looking for credible sources is always worth it in the end.

Head directly to the source of information

Heading over to Urban Dictionary, there are several definitions for “ krowemoh .” The top definition was written by someone with the username Sherli Damelio and was posted on Jan. 6. And here lies the issue with Urban Dictionary as a source — anyone on the internet can submit a definition.

For those who aren’t familiar with Urban Dictionary, it’s a sort of rebellious younger sibling to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. It’s key differences? Instead of professional editors defining the words, Urban Dictionary is fully crowdsourced. The website is also mostly for defining slang words and phrases. So is it a credible source when it comes to Latin? No.

See what other sources are saying

Doing a keyword search on Google brought up several articles debunking this claim, including a fact-check from Snopes . According to Snopes, “krowemoh” is definitely not a Latin word, since the letter W doesn’t exist in the Latin language.

Other ways to fact-check this claim would be to simply find an online Latin dictionary or use the Google Translate tool . The Latin dictionary brought up no results for “krowemoh.” And when consulting Google Translate, the Latin phrase for child abuse is completely different.

Not Legit. There is no truth to the claim that homework spelled backwards translates to “child abuse” in Latin.

Opinion | Donald Trump says there will be no more debates

He and his supporters are making the rounds criticizing debate moderators David Muir and Linsey Davis of ABC News

Fact-checking Donald Trump on the scale and causes of inflation under Biden, Harris

Trump inaccurately claimed Harris cast a vote that ’caused the worst inflation in American history, costing a typical American family $28,000’

How to avoid sanewashing Trump (and other politicians)

Sanewashing is the act of packaging radical and outrageous statements in a way that makes them seem normal. Here’s how reporters can eschew it.

Poynter: When it comes to using AI in journalism, put audience and ethics first

New report distills work from Poynter summit that brought together top journalists, product leaders and tech experts

Opinion | Will there be another presidential debate?

Harris’s team says she’d do another. Trump’s team is trying to spin that as proof that she lost the first one. Trump himself is sending mixed signals.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

Forget What You Heard About What the Word "Krowemoh" Means in Latin

Published May 2 2022, 6:26 p.m. ET

If you're getting your information from memes, you might want to check your sources. For years, there has been a meme going around saying that "krowemoh," which is "homework" spelled backward, translates to a type of abuse in Latin. Recently, the meme has started making the rounds on TikTok , which means it's time for us to step in and set the record straight.

What does "krowemoh" really mean? Does it actually have its roots in Latin? Keep reading to find out.

What does "krowemoh" mean in Latin? Don't believe the TikTok videos.

According to USA Today , "krowemoh" isn't a real word — in Latin or in any other language. It's just the word "homework" spelled backward. Unfortunately for some conspiracy theorists, there's no fancy backstory to the word "homework." It's a compound word that speaks for itself: It's work students are meant to do at home, or at least outside of school.

@xananditax THIS IS VERY SKETCHY. I’m getting out if teachers college. #krowemoh #fyp #MoneyTok #InLove ♬ original sound - Furry Destroyer

Although some sources say that the idea of homework goes as far back as ancient Rome, in America, it was actually banned for some time in California. According to History , there was an anti-homework movement going on in the late 1800s to the early 1900s. This is when the Golden State banned homework for students who weren't in high school.

Until the Cold War, homework was seen as an unpopular education tool in America. The Cold War is when the Space Race was underway and scientists from the Soviet Union were outshining the U.S. Then, Sputnik, the first Earth satellite, was launched by the Soviets in 1957. It made Americans feel as though Soviet schools were better than the ones here and homework became more popular.

Does "krowemoh" mean "child abuse" in Latin?

Despite what you may have heard, "krowemoh" does not mean "child abuse" in Latin. In February 2021, an Instagram account called Chillstonks Memes reposted a screenshot by Spicy Memer . The image was a Google search result that asked "what is homework backwards."

The top result read, "So, basically, 'homework' spelled backwards is 'krowemoh' which in Latin, translates to 'child abuse.'" Now, when you open that Instagram post, you will be met with a warning. The social media platform has flagged the post as "false information," with the image blurred in the back.

Not only did commenters on the original Instagram post call the meme out, one of them went one step further to explain why "krowemoh" wouldn't even be a word in Latin. "'Oh' isn't even a Latin suffix," one person pointed out, while another said that homework itself is the real child abuse. Now, that 's a claim that's hard to deny.

Sundown Towns Still Exist in the U.S.

TikTok's "Coastal Grandmother Aesthetic" Is About Enjoying the Little Things in Life

Marilyn Monroe's Relationship With the Mob, Frank Sinatra, and the Kennedys Was Complicated

Latest FYI News and Updates

- About Distractify

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Connect with Distractify

- Link to Facebook

- Link to Instagram

- Contact us by Email

Opt-out of personalized ads

© Copyright 2024 Engrost, Inc. Distractify is a registered trademark. All Rights Reserved. People may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Offers may be subject to change without notice.

Homework spelled backwards does not mean child abuse in Latin

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

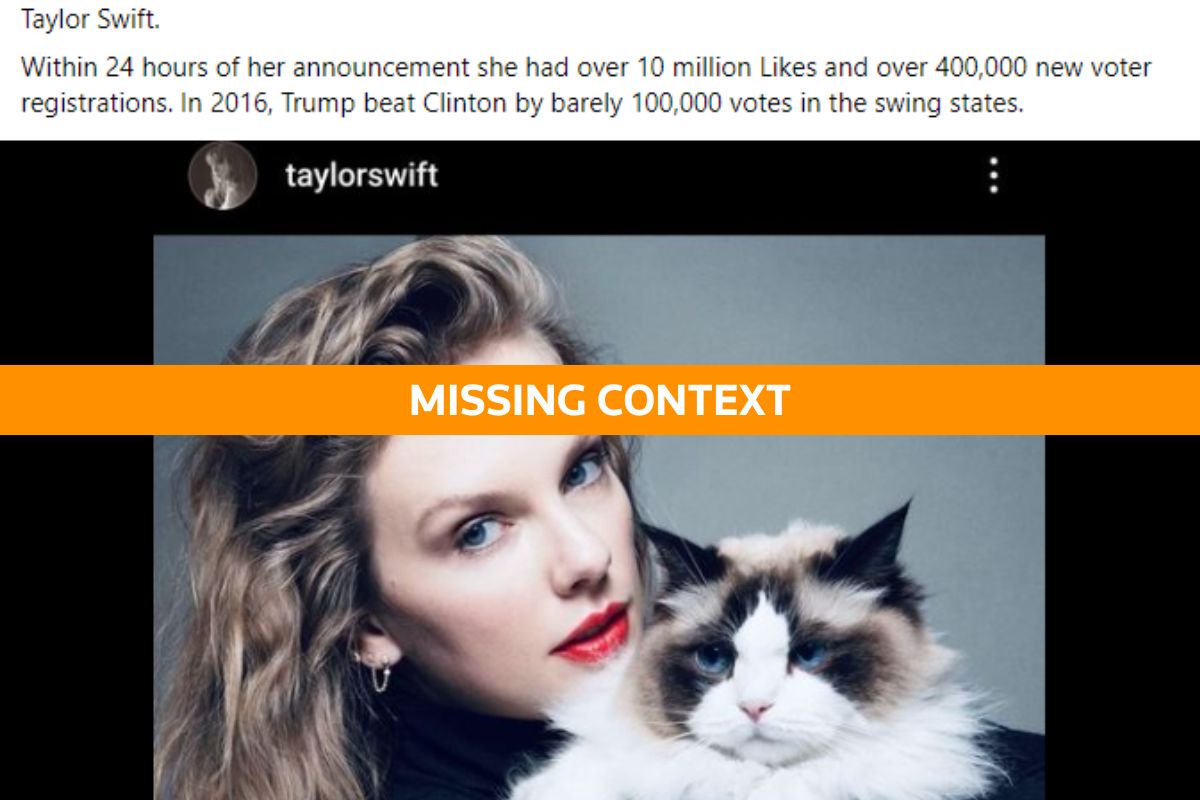

Fact Check: Clicks to Taylor Swift’s voter registration link misinterpreted online

Four hundred thousand people clicked-through from Taylor Swift’s Instagram account to a federal voting information site in 24 hours, but social media posts have misrepresented that number as a tally of new voter registrations.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of homework

Examples of homework in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'homework.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1662, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near homework

Cite this entry.

“Homework.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/homework. Accessed 16 Sep. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of homework, more from merriam-webster on homework.

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for homework

Nglish: Translation of homework for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of homework for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about homework

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, 31 useful rhetorical devices, more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

by Jacob Sweet

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

- Mental Health

- Social Policy

Most Popular

- Sign up for Vox’s daily newsletter

- The case against otters: necrophiliac, serial-killing fur monsters of the sea

- The new followup to ChatGPT is scarily good at deception

- America’s long history of anti-Haitian racism, explained

- The Carrie Bradshaws of TikTok

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in The Highlight

From prebiotic sodas to collagen waters, beverages are trying to do the most. Consumers are drinking it up.

Factory-built housing, ADUs, and community land trusts — all at once.

Why the new luxury is flip phones and vinyl LPs

We buy stuff. We throw it away. There’s a system to stop this toxic cycle.

It’s all about getting them comfortable with the unfamiliar.

From hot honey to buffalo ranch, we really, really, really love to make our dry foods wet.

- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

Related resources for this article

- Primary Sources & E-Books

Introduction

A city is a concentrated center of population that includes residential housing and, typically, a wide variety of workplaces, schools, and other permanent establishments as well as a transportation network. The economic, political, and cultural influences of cities are felt in local, national, and global affairs. Cities have long attracted people in search of work, education, and other opportunities to improve their lives.

Because of the great numbers of talented people that they bring together, cities are often centers of invention, artistic creation, tolerance, and social change. However, they can also be a nexus of poverty, overcrowding, violence, and suffering. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, who lived in a society that was still heavily rural, declared, “I am a lover of knowledge, and the men who dwell in the city are my teachers, not the trees or the countryside.” Centuries later, however, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau dubbed cities “the sink of the human race,” and the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley went so far as to call hell a city much like London.

Cities can endure for centuries or even millennia. However, they are a relatively recent invention in human history, dating back only 7,000 to 9,000 years. In ancient and medieval times cities began to appear throughout the world. But until the mid-20th century the vast majority of people continued to live on farms and in villages, unconcerned with the strange and distant life of cities. Since then urban areas have grown explosively, especially in poorer countries. Today cities and towns are home to about half of the world’s people, and most economic, political, and cultural interaction depends on them.

Defining Cities and Towns

There are no perfect definitions for the terms city and town. In general a city may be regarded as a large, relatively permanent concentration of people, as opposed to a military base, a mining camp, and other temporary settlements. A town is a settlement that is similar in nature but generally smaller than a city.

Cities and towns mean different things to people from different backgrounds. To a person in the relatively uninhabited Sahara or the northern tundra of Canada, for example, a settlement of 5,000 would qualify as a small city. However, that place would hardly qualify as a town to a resident of Cairo or Kolkata (Calcutta). In such larger cities 5,000 people can be found in a single neighborhood or school. This article will use the following rule of thumb: villages will be said to hold up to several hundred people, towns from roughly 1,000 to 20,000 people, small cities from 20,000 to 70,000 people, medium-sized cities from 70,000 to 500,000 people, and large cities from 500,000 to several million people.

Yet cities and towns should not be defined on the basis of population alone. Cultural and economic factors are also important, such as the percentage of workers in rural (agricultural) occupations as opposed to manufacturing and service jobs. Many cities and towns function as service centers for the surrounding countryside, but most of their residents live and work in the urban area rather than on nearby farms.

Cities and towns can also be defined in a political or legal manner. In the United States, for instance, a state legislature may charter a city—that is, designate an urban area as a city by writing a law or act of incorporation, called a charter. This charter describes the basic form of the city’s government and its powers. Some cities in the United States have only a few thousand people, while some incorporated villages are much larger. But usually cities are larger than towns or villages. In New Zealand the larger, more prosperous towns are officially called boroughs. In Great Britain the national government writes special acts that give the official title “city” to towns; sometimes the title is granted merely in recognition of a town’s historical identity as the residence of a bishop. Otherwise the title has no special significance in British law.

Urban and Metropolitan Areas

Cities are urban areas, meaning that they are developed and heavily populated, as opposed to rural areas, which are thinly populated countryside. The word urban is derived from the Latin urbs , meaning city. Therefore, the words urbanize and urbanization refer to populations becoming concentrated in cities. The United Nations identifies urban areas as concentrated places of 20,000 or more inhabitants. However, many countries have their own definitions: for instance, the United States defines urban places as those with at least 2,500 inhabitants, and the figure for Iceland is only 200. For the purposes of this article, most towns and cities will be regarded as urban areas.

Sometimes the words metropolitan and urban are used as synonyms, but metropolitan areas are usually larger than urban areas. Technically, a metropolitan area is a large area bound to a city by economics, politics, or other functions. If many residents of a smaller city commute to work (by car or train, for example) in a larger city, the two cities (or two urban areas) might be considered part of the same metropolitan area. For instance, metropolitan Miami—also called Greater Miami—includes North Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and several other cities in southern Florida.

Megalopolis and the “Megacity”

Nightmarish visions of overcrowded, dangerously polluted, skyscraper-ringed cities may seem like the stuff of science fiction. But for hundreds of millions of desperately poor people, these visions have become reality. In the early 21st century there were at least 19 metropolitan areas in the world with more than 10 million people each, and other cities were growing quickly to join their ranks. Some scholars refer to these as megacities, and the problems and challenges facing them are all too real. Meanwhile, several somewhat smaller areas also joined together to form interconnected regions known as conurbations.

The term megalopolis, derived from the Greek words meaning “great city,” was proposed by the French geographer Jean Gottmann to describe the nearly continuous, dense population belt on the East coast of the United States that stretches from Boston through metropolitan New York City and Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., an area sometimes called BosWash. The term has since been applied to other vast urban areas that have grown together, engulfing suburbs and other cities. Examples include Greater Mexico City, metropolitan Tokyo-Kawasaki-Yokohama, and Greater São Paulo, Brazil. In western Germany the Ruhr industrial basin has developed into a megalopolis since World War II. These interconnected areas typically have more than 15 million people.

Urban Hierarchies

Because of connections between cities of varying size and importance, a pyramidlike hierarchy of cities exists. At the top of the pyramid are world cities, which are also called world-class cities. World cities have powerful economic, political, and cultural ties to other cities, countries, and world regions, such as major stock markets, the headquarters of banks, and international organizations such as the United Nations or the European Union. New York City, London, and Tokyo are usually considered the main world cities today. Some would broaden the category to include such megacities as São Paulo, Mexico City, and Mumbai (Bombay). Interconnected with the world cities are a few dozen major cities that occupy the next level of the pyramid. These populous and influential urban centers include Rio de Janeiro; Johannesburg, South Africa; Seoul, South Korea; Hong Kong; Miami, Florida; Los Angeles; Berlin; Paris; Frankfurt, Germany; and Milan, Italy. Occupying successively lower levels of the pyramid are large cities of regional or national importance, such as Lagos, Nigeria, and Kuwait City, and large or medium-sized provincial centers, which may be important at the local and national levels because of their factories, government services, or transportation links. At the lowest tier in the global hierarchy are small cities and towns acting as “bedroom community” suburbs or as service centers for rural agricultural and mining areas.

Influences on Urban Growth

Most cities develop gradually from villages and towns as trading markets, university centers, or places of worship. They are generally built in locations that somehow aid them on local, national, and international scales. Such locations make a city more efficient in some way or in many ways, generally by giving it access to natural resources, trade connections, government services, or other advantages.

Key Locations

Cities must, of course, have adequate water and food supplies. Therefore many have been located adjacent to rivers and lakes, and most have been near productive agricultural areas. Rivers in particular have proven vital as sources of freshwater and as an inexpensive means of disposing of sewage (despite ecological damage downstream). New York City; London; Alexandria, Egypt; and Buenos Aires, Argentina, were all established on rivers in productive farming areas and near ocean shipping lanes. The most successful cities have continued to enjoy these advantages, even though food can now be transported over long distances and much of the world’s freshwater now comes from underground aquifers (permeable rock layers that hold water).

Riverside or lakeside locations have encouraged the development of cities also because of the trade opportunities they offer. A waterway provides a means for transporting goods to and from distant populations. A river or lake, however, could also be a potential obstacle to overland transportation. For this reason cities were historically built in places along the water where this obstacle could be overcome. One example of such a place is a river ford, where the river was shallow enough to allow overland travelers to cross with wagons or horses. Ferryboat crossings have also provided vital transportation links. Today bridges have replaced most river fords and ferries, but most river crossings still occur in towns and cities.

Port cities, where maritime freight is transferred to overland shipping, also represent transportation links. Among the large cities known for their harbors are Rotterdam and Amsterdam, both in the Netherlands; Barcelona, Spain; San Francisco; Singapore; Hong Kong; and Genoa, Italy. Coastal ports were key to the growth of the largest cities colonized by Europeans from the 16th to the 19th century, including Lima, Peru; Montevideo, Uruguay; Sydney, Australia; Lagos; and Cape Town, South Africa. In similar ways, canals, railroads, and highway systems have aided urban growth from the Industrial Revolution to the present. Since the 1970s airports have become vital to many cities, particularly those with economies depending largely on tourism.

In early times many cities were aided by locations on an easily defended hill, beside a sheltering bay, or with some other natural defenses. Ancient Rome, Constantinople (now Istanbul), and Jerusalem were built on hills. The old city at the heart of San Juan, Puerto Rico, was surrounded on three sides by water, and the historic center of Paris, Ile de la Cité (Island of the City), was protected by the Seine River.

Other Factors

Some cities were created or developed not from trade or defense but from political decisions. Washington, D.C.; Canberra, Australia; and Brasilia, Brazil, were all planned as national capitals. And throughout the world, there are thousands of cities and towns that have gained money and jobs because they were centers of local or provincial governments.

Some cities garner special claims to fame that help them, in turn, to grow even further. The heart of Florence, Italy, is a museum of Renaissance art and culture. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, has long been famous for its stunningly beautiful coastline and its Carnival celebrations. Since the mid-20th century Hollywood has been called the Motion Picture Capital of the World because of its film and television industries. At the same time, other cities have become so large and diverse that no single description can now define them, including Los Angeles (which surrounds Hollywood), Tokyo, Mexico City, São Paulo, Mumbai, Lagos, Cairo, New York City, Chicago, London, Paris, and Berlin. These and dozens of other large cities offer their inhabitants and visitors an enormous array of services in banking, commerce, education, and culture.

It is important to recognize that the factors that first gave a city its identity may change or disappear later on. For example, Timbuktu, Mali, was once famous in the Islamic world as a center for pilgrims and overland traders, but it lost importance because of its location in an arid region far from any large rivers or lakes. Another example is London, which was a major port for several centuries. Since the mid-20th century its port facilities have moved farther downriver and closer to the sea. Yet the city has continued to thrive as a seat of government and a center of world banking.

History of Urbanization

Cities throughout the world have developed in unique ways, and no single history can account for them all. Yet some general patterns exist in both Western civilization and other cultural traditions. Some patterns hold true for most of the world. As the global population has increased, for instance, so have the number of cities and the percentage of people living in them. This is known as the rate of urbanization.

As wandering hunter-gatherers and then fishers, people have lived in extended family groups and villages for tens of thousands of years. During this time the total number of people in the world was small but slowly increasing. About 2,000 years ago the entire world had less than 250 million people, and even in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, large cities were rare. The world’s population grew slowly through the Middle Ages, and by 1650 it was about 500 million. The population began to increase dramatically in the late 18th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. There were about 1 billion people in 1800 and about 1.6 billion in 1900, but even then only 14 percent of the population lived in urban areas. By 1900 only a dozen cities, including London, New York City, Paris, and Tokyo, had more than 1 million inhabitants. Thereafter, however, these numbers virtually exploded, so that by the mid-20th century 29 percent of the world’s 2.5 billion people lived in urban areas. In the early 21st century the world’s population was greater than 6.1 billion, and about half dwelled in urban areas, including hundreds of millions in cities with populations greater than 1 million. Urban history—indeed all of human history—has changed in revolutionary ways during the last 200 years alone.

Ancient Civilization

Civilization refers mainly to life in cities and towns—the word actually derives from the Latin civis , meaning “city”—but villages existed first. These precursors of urban settlements appeared by about 10,000 bc in most parts of the world. Larger concentrations of people were not desirable for people who depended so directly on the natural world.

Most villages were probably semipermanent. When the soil around a farming village was exhausted by primitive methods of cultivation, the entire village moved elsewhere. If a village prospered in one place and increased its population, it would have to split into two so that all inhabitants would have enough good soil for farming as well as enough wild game and food-bearing plants.

One of the oldest known ruins of a town is Çatalhüyük in southern Turkey, which may date from before 7000 bc . Other early towns and cities do not appear to have evolved until some 2,000 years later. The earliest large settlements in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) date from 5000 bc or earlier, and cities were developing there by about 3500 bc . Supplied with freshwater by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, these cities grew quickly. By about 3000 bc the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk (Erech) was home to as many as 50,000 people. The urban civilization of the Indus River valley, centered on the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in what is now Pakistan, developed by about 2500 bc . ( See also ancient civilization ; Indus Valley civilization .)

One of the most significant developments that enabled cities to grow and prosper was the division of labor. The larger a population, the greater its needs. Not everyone could be a farmer. Someone had to build homes, granaries, temples, and government structures. Increasingly skilled artisans provided the tools and luxuries for everyday living. Others—often entire families—became specialized as priests, rulers, and warriors.

As life became more complex, forms of trade developed and types of money were invented. This, in turn, required systems of record keeping, leading to the invention of writing . The world’s earliest-known writing systems appeared in ancient Sumer and Egypt. All such early writing was pictographic, meaning that it used pictures to communicate ideas. The written records kept since then have added greatly to our knowledge of past civilizations.

Larger settlements also benefited from technological advancements, including irrigation systems, the domestication of animals and wild grains, and inventions such as the wheel, which greatly enhanced transportation and overland trade. However, not all of these improvements were available throughout the world. For example, horses, cattle, sheep, and wheat were not found in the Americas, and in Africa many large animals could not (and still cannot) be domesticated, such as the zebra, hippopotamus, and rhino. (Elephants could be tamed and trained, in Africa as well as Asia, but never truly domesticated.) This availability of plant and animal resources is one possible explanation for the more rapid spread of cities in Europe and Asia.

Some early cities were commercial centers or rest stops along busy trade routes. Others were religious centers, where people congregated to consult priests and oracles (seers) or to visit places that were supposed to have magical qualities. Religious centers also stimulated long-distance pilgrimages and trade. It is sometimes impossible to tell whether an ancient site developed because of either spiritual or commercial reasons, or whether both were equally important.

Modern ideas about past civilizations are biased by the evidence available. The bias is due, in part, to preferences for studying European and Mediterranean sites (including biblical sites) rather than sites in other regions. Additionally, much evidence has been lost to time. Stone ruins can stand for millennia, but wooden structures burn or rot, and many have not been discovered until relatively recently. An example is Cahokia, a thriving Mississippi Valley trading center that had as many as 20,000 people by ad 1050. Massive, grass-covered mounds still stand on the site, in what is now the state of Illinois, but only traces of wooden buildings have been uncovered.

It is impossible to know exactly how many people lived in the city of Rome at the height of its influence, but estimates vary between 250,000 and 1.6 million. However, most ancient cities were only a fraction of that size. Although the Western Roman Empire eventually lost power and was destroyed in the invasions of Germanic peoples in the 4th and 5th centuries ad , the city of Rome survived, if damaged and diminished. Other Mediterranean and European cities, such as Paris, Marseille, and Naples, met with similar fates. But others were destroyed or completely abandoned, ushering in the end of the so-called classical world and the start of the European Middle Ages. These events went unnoticed elsewhere. Cities continued to thrive in populous regions as diverse as the Middle East, Africa, China, and Mesoamerica. ( See also ancient Greece ; ancient Rome ; city-state .)

Middle Ages

European towns in the Middle Ages developed around the dwelling places of kings, princes, and bishops; around the strongholds of feudal lords; around markets; and as revivals of old Roman sites. But most cities had only a few thousand inhabitants, making them smaller than many of today’s towns and villages. Even prominent cities were limited in size until the 12th and 13th centuries—the so-called high Middle Ages.

In the year 1100 the largest cities south of the Alps—including Florence, Genoa, Milan, Venice, and Naples in Italy as well as Barcelona, Córdoba, Seville, and Granada in Spain—probably had fewer than 25,000 people. But they began to grow dramatically as commercial centers owing to international trade; by the 14th century Venice had about 100,000 inhabitants. There were fewer major cities north of the Alps in 1100. London had only about 10,000 residents and Paris about 25,000. But Paris grew to at least 100,000 by the early 14th century, making it arguably one of the most important cities in Europe. In addition, the cities of the Hanseatic League in northern Europe were successful trading centers.

Medieval cities attracted a variety of families who tended to move into separate neighborhoods with people of similar backgrounds. The result was the division of cities into “quarters,” or neighborhoods that were largely self-sufficient. Each quarter tended to have its own church or synagogue, markets, water supply, and social institutions. Remnants of the old quarters can still be visited in some cities.

Some towns and cities were centered on castles, and the most successful of them also surrounded themselves with high stone walls. One of the most spectacular surviving walled cities is Ávila, Spain. The remains of walls are also visible in other cities, such as Beijing, China; Istanbul, Turkey; Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany; and Rhodes, on the Greek island of Rhodes.

In nearly all European towns of the Middle Ages, the church steeple was the tallest structure, and most of these could be seen for miles around. Costly and elaborate cathedrals became the crowning architectural achievements of some cities. The most awe-inspiring of these were the soaring, richly decorated Gothic structures, which often took centuries to build.

By today’s standards these medieval cities were neither clean nor particularly attractive. Many had monumental structures and beautiful artwork, but, except for the rulers and wealthy merchants, most of the population lived in poor-quality housing. Streets were little more than footpaths; paving was not introduced until 1184 in Paris, 1235 in Florence, and 1300 in Lübeck, in what is now Germany.

Unhygienic conditions undoubtedly contributed to a devastating epidemic called the plague, or the Black Death , which spread to Europe after afflicting cities in Asia and the Middle East. In the first three years of the epidemic in Europe, between 1348 and 1350, some cities lost at least half of their residents. The population of Siena, Italy, for instance, dropped from about 42,000 to 15,000. More than a third of the population of Europe was wiped out.

Europe suffered additional outbreaks of plague in the 14th century but recovered slowly. In France new market-oriented towns called bastides were established in attempts to generate revenue for the king and to resettle areas that had been depopulated by the plague. Economic progress continued in France, Italy, Germany, Flanders, and England, leading to the growth of industry, trade, and banking that is sometimes called the commercial revolution.

This economic expansion continued through the Renaissance , a period characterized particularly by a flowering of the arts and sciences. The development of international trade and the exchange of ideas across cultures during the Renaissance further expanded the size, importance, and influence of cities. The Renaissance also led to new architectural styles in European cities, particularly in Italy.

Industrial Revolution

The great economic and cultural shift called the Industrial Revolution began in England in the late 18th century and from there spread to other parts of the world. City populations exploded during this period, which marked the transition from mostly agricultural economies to those dominated by machine-based manufacturing.

The Industrial Revolution had its roots in another major transition—the agricultural revolution. Earlier in the 18th century wealthy British landowners had taken advantage of poor peasants with the enclosure movement, in which they fenced off formerly communal lands and turned them over to private ownership. As a result, many poor families were forced to move. Some went to other villages or towns, and others poured into cities. At roughly the same time, farming advancements such as crop rotation and steel plows greatly increased food production, making it possible for much larger concentrations of people to live together. Increased agricultural efficiency also reduced the number of workers needed on farms, making more of them available for industry.

In Britain and the United States in the 19th century many textile factories were built inland along rivers so that water could be used to power their machinery. Some “company towns” for workers grew up around them, one example being Lowell, Massachusetts. After coal-fired steam engines began to replace waterpower, new factories were built in or near existing cities, where great numbers of workers were available.

These factories, in turn, helped spark the rapid growth of cities. In 1801 in England and Wales there were only 106 urban places that had 5,000 inhabitants or more. By 1891 there were 622, with 68 percent of the population. Similar developments soon took place in the United States, as hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers and their families arrived seeking jobs. In 1790 the largest city in the United States was New York City, with about 33,000 residents, followed by Philadelphia with 28,000. During the 19th century New York City’s population multiplied fiftyfold, to 1.5 million, and many other cities also underwent incredible growth. The cities of western and central Europe experienced similar development.

It is important to note that in 1800, the Industrial Revolution had not yet reached Asia. However, Asia already had more than 30 cities with more than 100,000 people, representing almost two thirds of the world’s large-city population. Edo (now Tokyo) was probably the largest city in the world at that time, with more than 1 million people. Among the other major cities were Beijing and Guangzhou (Canton), both in China, and Kolkata, in India.

Smoke, thick and black, covers the town.…300,000 human creatures move ceaselessly through that stunted day. A thousand noises rise endlessly from out of this dark, dank maze….The steps of scurrying crowds, the cranking of wheels grinding against each other, the scream of steam escaping from furnaces, the regular beat of looms, the heavy roll of wagons….Yet out of this stinking drain the most powerful stream of human industry springs to fertilize the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows.

Around the turn of the 20th century most large cities suffered the almost unbearable stench of horse dung and urine as well as human waste and refuse. Coal-burning fireplaces and factories created London’s famous “pea soup” fog. Although this provided a mysterious backdrop for Sherlock Holmes novels, it was a serious health problem.

Advances in transportation sparked changes in city life around this time. In early 19th-century cities dense populations tended to reside within walking distance from factories. The wealthy, however, could afford to take carriages from their suburban homes to the commercial district. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries suburban railroads and horse-drawn streetcars began to encourage the spread of urban areas. However, this type of commuting remained too expensive for working-class people until prices were gradually lowered. Among the suburbs radiating outward, the newest were usually limited to the wealthy. Older, less desirable suburbs were affordable to the middle class, and still older and more rundown districts (from which the middle class was escaping) were generally filled with working-class homes.

Meanwhile, these advances in transportation caused city centers to face traffic jams of wagons, horses, and pedestrians. To alleviate the congestion, large cities such as Paris, Buenos Aires, and New York began to develop subways, elevated trains, and other public transportation systems.

In the 1880s and 1890s a new building method was introduced in Chicago. In steel-cage construction, a steel skeleton, or cage, took the place of stone as the main support for a building. Improvements in elevator technology around this time allowed for quick and efficient movement between floors within these structures. As a result, ever-taller office buildings, department stores, and apartment complexes transformed the skylines of Chicago, New York City, and, eventually, most other cities in the world. And these tall buildings, in turn, created even greater concentrations of workers who commuted by train and subway.

20th and 21st Century Urbanization

Cities have grown rapidly in size since the early 20th century, and especially since the 1940s. In addition, the layouts of cities have reflected the increasing reliance on cars and trucks. American cities in particular saw cars become a pillar of modern culture, and city streets have received funding that might have otherwise been invested in public transportation systems, such as buses and subways. Even East Asian cities, which have traditionally had more bicycle and pedestrian traffic, have begun to experience the congestion and air pollution caused by motorcycles and automobiles.

At the same time, advances in technology—from electricity to building materials—have helped bring about larger and stronger buildings, bridges, tunnels, roads, and rail systems. Greater numbers of workers have become concentrated in skyscrapers and other massive buildings, requiring more buses, trains, and subways to handle the twice-daily tides of commuters. In addition, high-rise buildings have driven up real estate values and rental prices. Many workers have been pushed away from city centers or into more cramped residences as prices have soared.

World War II (1939–45) accelerated the rate of urban change. Following the war bombed-out parts of cities were rebuilt, often with modern buildings and subways alongside restored structures. Meanwhile, postwar economic prosperity encouraged families in the United States to buy automobiles and homes in the sprawling suburbs. Urban sprawl became more notable beginning in the late 20th century, particularly in the United States and in the capital cities of poorer countries. Greater Mexico City, for example, grew in area as its population exploded from about 5 million in 1960 to about 20 million in the early 21st century.

One of the powerful influences on urban development in the early 21st century was globalization, meaning the increasing connections of trade, markets, and ideas throughout the world. While potentially beneficial, globalization encouraged many corporations to close factories in North America and Europe and shift their operations to developing countries where labor was cheaper and environmental laws were loosely enforced. Scholars disagreed on whether these shifts would ultimately prove beneficial or detrimental.

City Government

Cities around the world have a wide variety of governments with different levels of control over their affairs, including property and sales taxes, attracting business investors from other cities and countries, urban planning, and services. Among the services provided by city governments are police forces, court systems, hospitals, road and street maintenance, school systems, fire departments, public housing, environmental monitoring, water supply, sewage systems, and garbage disposal. Many city governments also support museums, libraries, art galleries, and a variety of cultural activities.

One of the world’s most common forms of city government is the mayor-council system. This exists in two types—weak mayor and strong mayor. A weak mayor has few administrative powers; instead the city is generally run by the city council, which is made up of several councillors who are usually elected to represent the different districts or neighborhoods of the city. By contrast, in cities with a strong mayor system, the mayor can veto the council’s acts, prepare the budget, appoint heads of departments and commissions, and generally lead the community.

The city manager system is also widespread. It was originally inspired by business corporations in which a board of directors hires a general manager to oversee operations. In cities using this type of government, residents elect city council members, who, in turn, hire a city manager, pass ordinances (local laws), and decide on taxation. Many of these cities also have an elected mayor, but he or she tends to serve in a ceremonial manner. The city manager is the executive who appoints department heads, coordinates activities, and carries out policies determined by the council.

City Layouts: The Urban Fabric

The easiest way to see the general layout of a city is to fly over it. From above one can see the residential neighborhoods of houses, stores, parks, schools, and playgrounds; banks, department stores, office complexes, hotels, and government buildings in the central city; and factories and industrial parks around the fringes. Sometimes, in very large cities, there are factories and industrial parks near residential areas. Cities must also have public utilities: water and sewage systems, electric power, natural gas, and telephone lines. And there must be streets and other transportation connecting the various places. These elements of cities are patched together into a complex whole that is sometimes called the urban fabric.

Transportation Networks

Streets have always formed the basic transportation grid within cities and towns. Even ancient Roman cities depended on a practical system of streets, including one-way streets to lessen the numbers of traffic jams of chariots, wagons, horses, and pedestrians. From the mid-20th century to the present, the need to move easily within and around cities has led to the construction of new streets and expressways, particularly in the United States.

Public transportation systems such as trains, buses, and subways are considered indispensable, but they struggle to meet the demands placed on them in many urban areas. Because of greater government support, European cities have public transportation systems that are generally superior to those in the United States. Some planners believe that advanced communications such as cell phones and portable computers could replace the need for traditional transportation networks by allowing people to work, study, and shop at home. Yet even though people have increasingly used the Internet for these activities, transportation systems seem to be busier than ever.

Commercial and Residential Districts

Cities often seem to be formed of several districts patched together, and urban zoning laws (which restrict the types of construction, houses, and businesses allowed in some zones of the city) may reinforce the differences among these districts. Historically, most cities have had a “downtown” area, or Central Business District (CBD), where most high-rise office buildings and shops are located. Many CBDs are no longer “central” or concentrated, however, but instead spread out for several square miles in various directions.

Heavy industries are typically located a fair distance from the CBD, depending largely on property values and the transportation network, especially railroads and rivers necessary for moving freight. In many cities old industrial warehouses have been torn down or converted into high-rise apartments and office spaces. Meanwhile, vast new warehouses have been constructed in suburbs with easy access to highways.

Several types of residential neighborhoods tend to be arranged around the city, including working-class housing adjoining old industrial districts, larger and newer housing estates for middle-class residents, and high-value, gated communities and high-rise apartments for upper-middle-class and wealthy residents. Although these neighborhoods are purposely separated in many cities, it is often possible to see an attractive, well-kept block of houses almost adjacent to a dilapidated area.

Recreational Areas and Parks

Although some people can afford to get away on vacations, all city dwellers need “escapes” that are closer to home, whether that means a few hours in a neighborhood park, a Saturday afternoon at an urban beach, or a visit to some other place free of industrial pollution and neon signs. Tree-shaded, grass-covered parks are at a premium in many cities, especially in poorer areas. Also important are views of natural features beyond the city such as mountains, lakes, rivers, and forests.

Unfortunately, city planners do not always allow for large amounts of space to be devoted to parks and recreational areas, or when they do, funding is not always available to clean up and preserve the best areas. Often neighborhood committees or other groups of concerned citizens will pressure their city governments to improve the conditions of parks and open spaces near their residences.

The Vertical City

Cities depend as much on vertical space—above and below the ground—as on their land area. City skylines are the panoramic scenes created by rows of the tallest buildings and highest-placed monuments, and these high structures often become symbols of the city itself. Some of the more famous examples are Paris’ Eiffel Tower and Rio de Janeiro’s statue of Christ atop Mount Corcovado.

While tall monuments and skylines may be world famous, their underground counterparts are also vital to cities. Beneath nearly all the streets of most CBDs is a maze of sewers, old freight or maintenance tunnels, communication lines, and subways, which crisscross spaces between the basements of office buildings and department stores. Some cities also have “stacked” levels of streets, the result of building an almost solid layer of streets, sidewalks, and parking spaces a full story above the original street level. An example is Chicago’s Wacker Drive, which has both upper and lower levels open to traffic. Other cities, such as Montreal, have belowground pedestrian “streets” that are thriving commercial centers, particularly during winter months.

Urban Sprawl and Urban Blight

Cities since the 1940s have been rapidly spreading outward and engulfing forests, river valleys, and croplands. Urban sprawl has occurred around the world—in eastern China, the capital cities of Latin America, Egypt’s Nile River valley, western Europe, Japan, and particularly the United States, where suburban growth has outpaced that of the central cities.

The term suburb comes from a Latin word meaning “at the foot of the city,” from a time when a properly defensible city was built on a hill and any spillover of population had to live at the base of the hill. Suburbs are distinct from the large cities they surround, and they may be towns, villages, or cities themselves. They typically have their own local governments and services such as fire departments and school systems.

Although suburbs have existed since ancient times, they grew significantly in number in the United States and Great Britain in the 19th century as wealthier people escaped the congestion of cities to more congenial areas on the edge of the countryside. Most early suburbs were built near railroad stations, but beginning in the 1920s they spread out along new streets and highways as automobiles became more numerous.

In wealthier countries, bulldozers have stripped away fields and forests to make room for row upon row of middle-class and upper-class housing ranging in style from apartment complexes to large, mansionlike homes with spacious yards. Sprawl is also characterized by wide, multilane streets and highways, thousands of streetlights and traffic signals, blacktopped parking lots, and swaths of strip malls, fast-food restaurants, and convenience stores.

In contrast, the suburbs of Latin America, Africa, and other poorer regions have typically been established by impoverished, landless citizens. Millions of these people have set up shantytowns by organizing mass “invasions” of suburban fields and then confronting police who are sent to evict them. They often struggle to obtain basic services such as water and electricity while seeking jobs in the metropolitan area.

Suburbs have become major sources of employment as many companies have set up operations in them. As a result, workers are now as likely to commute to work between suburbs as between a suburb and the central city. Many business investors perceive suburbs as more attractive than central cities because of their generally better-educated and wealthier populations, relative abundance of space, newer schools, and better public services. As investment leaves the inner cities, jobs there are lost, housing values decline, and less tax money is available for schools and city services.

In the United States, the flight to the suburbs reinforced racial divisions and bigotry because many of those remaining in central cities were minorities such as African Americans and Hispanics and most of those departing were whites. As a result, much of what constitutes urban sprawl has been called “white flight.” The zones of urban blight in inner cities are also known as the metropolitan area’s “hollow core.”

A more recent, and more limited, phenomenon in the United States may be referred to as “reverse flight.” Some whites have moved back into cities from the suburbs to cut back their commutes or take advantage of the greater cultural opportunities that cities provide. Most of these people, however, have moved into city areas from which poorer minority residents have been forced by rising property values. As a result, reverse flight has done little to increase racial diversity or improve the blighted areas in which many minorities live.

Environmental Problems

To some people the city represents humanity’s triumph over nature. Certainly it is a radical change of nature. What was once field or forest is covered with pavement and buildings. Natural balances of air, water, soil, and even noise are fundamentally altered. The very existence of large cities, in addition to all the activities that go on in them, has perhaps permanently altered the global environment.

With all of the conveniences of city life, many urban residents forget that cities cannot exist on their own. Some have even naively claimed that all of the world’s people could settle in a single megacity smaller than the state of Texas. But where would these billions of people grow food? Or work? Or dispose of their sewage? Or breathe clean air? They would not have access to enough open space or natural resources, and an environmental and social catastrophe would result. A city has to be understood in the context of its surrounding region.

Cities have the potential to destroy or damage all kinds of plant and animal habitats, but they are particularly threatening to fragile ecosystems such as rainforests. For instance, the city of Manaus includes more than 1 million people in the Amazon rainforest of northern Brazil. In that once pristine ecosystem, fish have nearly disappeared from the river for miles around the city, huge swaths of forest have been destroyed, and the air and water of the area have become heavily polluted. In a similar manner, cities have had major effects on the plant and animal life in deserts, in river valleys, and in highland areas. Countless other cities have affected their surroundings in ways that are hard to measure.

Urban Animal Life

Cities, though made for humans, are home to numerous other creatures that share their built-up spaces. Pets are an obvious example. In North America and Europe alone, hundreds of millions of cats and dogs add to the urban population. Along with these human companions, cities are also the dwelling places of uncounted millions of rats, squirrels, mice, and other rodents as well as vast numbers of insects, the hardiest of which include cockroaches, ants, and termites. Many animals eke out an existence in the labyrinthine subway and sewer pipes beneath the streets, emerging only at night. Others choose more open locations. Spiders, for example, have been known to spin webs outside the windows of the world’s tallest buildings, some 100 stories above the ground. Insect-eating birds (and bird-eating hawks) wheel above the “canyons” created by skyscrapers, and cooing, scavenging pigeons populate city parks and plazas.