- Research Guides

- CECH Library

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

Writing annotations.

- Introduction

- New RefWorks

- Formatting Citations

- Sample Annotated Bibliographies

An annotation is a brief note following each citation listed on an annotated bibliography. The goal is to briefly summarize the source and/or explain why it is important for a topic. They are typically a single concise paragraph, but might be longer if you are summarizing and evaluating.

Annotations can be written in a variety of different ways and it’s important to consider the style you are going to use. Are you simply summarizing the sources, or evaluating them? How does the source influence your understanding of the topic? You can follow any style you want if you are writing for your own personal research process, but consult with your professor if this is an assignment for a class.

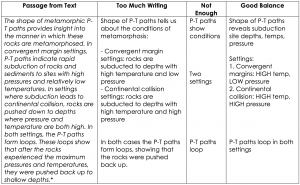

Annotation Styles

- Combined Informative/Evaluative Style - This style is recommended by the library as it combines all the styles to provide a more complete view of a source. The annotation should explain the value of the source for the overall research topic by providing a summary combined with an analysis of the source.

Aluedse, O. (2006). Bullying in schools: A form of child abuse in schools. Educational Research Quarterly , 30 (1), 37.

The author classifies bullying in schools as a “form of child abuse,” and goes well beyond the notion that schoolyard bullying is “just child’s play.” The article provides an in-depth definition of bullying, and explores the likelihood that school-aged bullies may also experience difficult lives as adults. The author discusses the modern prevalence of bullying in school systems, the effects of bullying, intervention strategies, and provides an extensive list of resources and references.

Statistics included provide an alarming realization that bullying is prevalent not only in the United States, but also worldwide. According to the author, “American schools harbor approximately 2.1 million bullies and 2.7 million victims.” The author references the National Association of School Psychologists and quotes, “Thus, one in seven children is a bully or a target of bullying.” A major point of emphasis centers around what has always been considered a “normal part of growing up” versus the levels of actual abuse reached in today’s society.

The author concludes with a section that addresses intervention strategies for school administrators, teachers, counselors, and school staff. The concept of school staff helping build students’ “social competence” is showcased as a prevalent means of preventing and reducing this growing social menace. Overall, the article is worthwhile for anyone interested in the subject matter, and provides a wealth of resources for researching this topic of growing concern.

(Renfrow & Teuton, 2008)

- Informative Style - Similar to an abstract, this style focuses on the summarizing the source. The annotation should identify the hypothesis, results, and conclusions presented by the source.

Plester, B., Wood, C, & Bell, V. (2008). Txt msg n school literacy: Does texting and knowledge of text abbreviations adversely affect children's literacy attainment? Literacy , 42(3), 137-144.

Reports on two studies that investigated the relationship between children's texting behavior, their knowledge of text abbreviations, and their school attainment in written language skills. In Study One, 11 to 12 year-old children reported their texting behavior and translated a standard English sentence into a text message and vice versa. In Study Two, children's performance on writing measures were examined more specifically, spelling proficiency was also assessed, and KS2 Writing scores were obtained. Positive correlations between spelling ability and performance on the translation exercise were found, and group-based comparisons based on the children's writing scores also showed that good writing attainment was associated with greater use of texting abbreviations (textisms), although the direction of this association is not clear. Overall, these findings suggest that children's knowledge of textisms is not associated with poor written language outcomes for children in this age range.

(Beach et al., 2009)

- Evaluative Style - This style analyzes and critically evaluates the source. The annotation should comment on the source's the strengths, weaknesses, and how it relates to the overall research topic.

Amott, T. (1993). Caught in the Crisis: Women in the U.S. Economy Today . New York: Monthly Review Press.

A very readable (140 pp) economic analysis and information book which I am currently considering as a required collateral assignment in Economics 201. Among its many strengths is a lucid connection of "The Crisis at Home" with the broader, macroeconomic crisis of the U.S. working class (which various other authors have described as the shrinking middle class or the crisis of de-industrialization).

(Papadantonakis, 1996)

- Indicative Style - This style of annotation identifies the main theme and lists the significant topics included in the source. Usually no specific details are given beyond the topic list .

Example:

Gambell, T.J., & Hunter, D. M. (1999). Rethinking gender differences in literacy. Canadian Journal of Education , 24(1) 1-16.

Five explanations are offered for recently assessed gender differences in the literacy achievement of male and female students in Canada and other countries. The explanations revolve around evaluative bias, home socialization, role and societal expectations, male psychology, and equity policy.

(Kerka & Imel, 2004)

Beach, R., Bigelow, M., Dillon, D., Dockter, J., Galda, L., Helman, L., . . . Janssen, T. (2009). Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Research in the Teaching of English, 44 (2), 210-241. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784357

Kerka, S., & Imel, S. (2004). Annotated bibliography: Women and literacy. Women's Studies Quarterly, 32 (1), 258-271. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/233645656?accountid=2909

Papadantonakis, K. (1996). Selected Annotated Bibliography for Economists and Other Social Scientists. Women's Studies Quarterly, 24 (3/4), 233-238. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40004384

Renfrow, T.G., & Teuton, L.M. (2008). Schoolyard bullying: Peer victimization an annotated bibliography. Community & Junior College Libraries, 14(4), 251-275. doi:10.1080/02763910802336407

- << Previous: Formatting Citations

- Next: Sample Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2024 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/annotated_bibliography

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

Your browser does not support javascript. Some site functionality may not work as expected.

What is an Annotation?

- Why Do an Annotated Bibliography?

- What Should be Included in the Annotation?

- What Format Should I Use for the Citations?

- Evaluating Sources

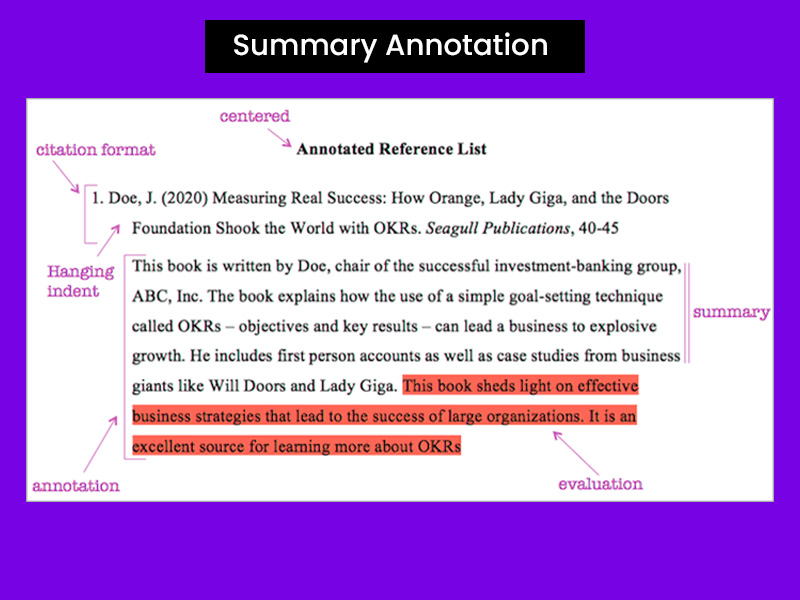

- Summative Annotations

- Evaluative Annotations

- Examples from the Web

- Additional Resources

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- Annotated Bibliographies

Annotated Bibliographies: What is an Annotation?

An annotation summarizes the essential ideas contained in a document, reporting the author's thesis and main points as well as how they relate to your own ideas or thesis. There are two types of annotations: summative and evaluative (see examples under the 'Types of Annotations' tab on this guide). Annotations are typically brief (one paragraph) but may be longer depending on the requirements of your assignment.

If you are creating an annotated bibliography for a class assignment, check with your instructor to determine the citation format, length and the type of annotations you will be writing.

Remember, your annotation should show that you have done more than simply describe what is in the source!

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Why Do an Annotated Bibliography? >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 12:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/bothell/annotatedbibliographies

Quick Links:

Understanding Annotation: A Comprehensive Guide

What is annotation, the purpose of annotation, types of annotation, how to annotate effectively, annotation tools, annotation examples, annotation in different disciplines, annotation vs. abstract, annotation in digital learning, the future of annotation.

Let's take a journey into the world of annotation, a concept that often makes students cringe and researchers sigh. But, don't worry — this guide will help you understand annotation in a simple, friendly, and clear way. Whether you're a newbie or someone who just needs a refresher, this comprehensive guide will provide a clear definition of annotation and its many uses.

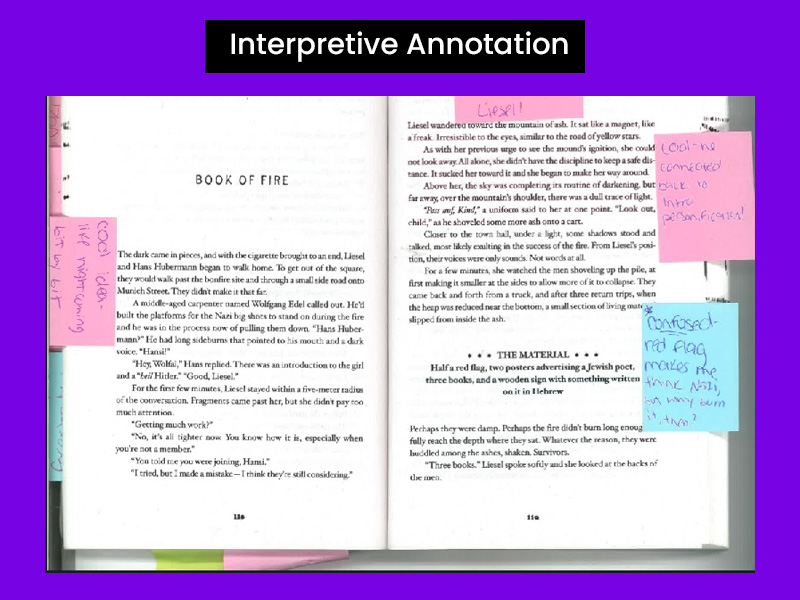

So, what exactly is the definition of annotation? In its simplest form, annotation refers to adding notes or comments to a text or a diagram. It's like having a personal conversation with the author, or making sense of a complex graph. It doesn't stop there, though. The process of annotation is much more than just dropping notes — it's about understanding, interpreting, and engaging with the material. Let's break it down:

- Understanding: Annotations help you to grasp the ideas and concepts presented in the text or diagram. You might underline key phrases or highlight important data points, all in the service of better understanding what you're reading or viewing.

- Interpreting: By providing your own insights or explanations, you're not merely reading or looking at the material, but actively interpreting it. This could be as simple as jotting down "This means..." or "The author is saying..." next to a paragraph.

- Engaging: When you annotate, you're not just a passive reader anymore. You're actively engaging with the material, questioning it, agreeing or disagreeing, even arguing with the author! This active engagement helps to deepen your understanding and retention of the material.

To sum it up, the definition of annotation isn't just about making notes — it's a method to read, understand, interpret, and engage with any piece of content more effectively. And guess what? There's more to annotation than you might think! Stick around as we delve deeper into the purpose, types, and tools of annotation in the following sections.

Now that we've nailed down the definition of annotation, let's talk about why it's so important. Why do teachers, professors, and researchers keep insisting on it? Well, there are several reasons:

- Improves comprehension: Annotating helps you understand the text or diagram better. It's like having a personal guide walking you through a dense forest of words or a complex maze of data. By highlighting and commenting, you can make sense of the material more easily.

- Enhances retention: We've all been there. You read a page, flip it, and — poof! — everything's gone. But with annotation, you can remember more. When you actively engage with the material, you're more likely to remember it. It's like the difference between watching a movie and participating in it.

- Facilitates analysis: Annotation is not just about understanding, but also about analyzing. By adding your own thoughts, insights, and interpretations, you can dig deeper into the material, uncovering layers of meaning that might not be immediately apparent.

- Promotes critical thinking: When you annotate, you're not just accepting information passively — you're actively questioning, evaluating, and critiquing it. This cultivates critical thinking skills, which are crucial in today's information-saturated world.

Remember, the purpose of annotation is not to make your book look like a rainbow or to fill the margins with a clutter of notes. It's about making the material work for you, helping you to understand, remember, analyze, and think critically. So next time someone mentions annotation, don't cringe. Embrace it. It's your secret weapon in the world of learning!

Now that we've got a grip on the definition of annotation and its purpose, it's time to dive into the different types of annotation. You might be thinking, "Wait a minute, there's more than one type?" Yes, indeed! And picking the right one can make a world of difference. So, let's explore:

- Descriptive Annotation: This kind of annotation is like a sneak peek of a movie. It gives an overview of the main points, themes, or arguments without revealing too much. It's like a book cover — enticing enough to draw you in, but not revealing all the secrets.

- Critical Annotation: This type goes a step further. It not only describes the content but also evaluates it. It's like a movie review, discussing the strengths and weaknesses, the relevance of the content, and the author's credibility. It helps you decide whether the material is worth your time.

- Informative Annotation: This annotation is like an all-you-can-eat buffet. It provides a summary of the material, including all the significant findings and conclusions. It's ideal when you need a detailed understanding of the content without having to read the whole thing.

- Reflective Annotation: This type of annotation is a bit more personal. It includes your thoughts, reactions, and reflections on the material. It's like a diary entry, capturing your intellectual journey as you engage with the material.

So, next time you're tasked with annotating, consider the type of annotation that best suits your needs. Remember, the goal is not to make your work harder, but to make it easier and more effective. Happy annotating!

Here you are, equipped with the definition of annotation and an overview of its types. But, how do you do it effectively? Let's break it down:

- Get clear on your purpose: Why are you annotating? Is it to understand better, remember, or critique? Your purpose will guide your annotation process.

- Take a quick preview: Before you start annotating, skim through the material. Get a feel for its structure and main ideas. This way, you'll know what to pay special attention to.

- Be selective: Resist the urge to highlight or underline everything. Limit your annotations to crucial points, unfamiliar concepts, and interesting ideas. The goal is to create signposts that can guide you back to key information when needed.

- Make it meaningful: Don’t just underline or highlight. Write brief notes that summarize, question, or react to the content. This makes your annotations a tool for active learning.

- Use symbols or codes: Develop your own system of symbols or codes to denote different types of information. For example, a question mark could indicate parts you don’t understand, while an exclamation mark could point to surprising or important insights.

Remember, effective annotation is not about how much you mark, but about how well you understand and engage with the material. Keep practicing and refining your approach, and soon you'll become an annotation pro!

So, now that we know how to annotate effectively, let's talk about some tools that can make this process even smoother. These are especially handy if you're dealing with digital content, or if you want to share your annotations with others. Here are some noteworthy ones:

- Pencil and Paper: Sometimes, the old ways are the best ways. Nothing beats the flexibility and simplicity of annotating with a good old-fashioned pencil. You can underline, highlight, make notes in the margin — the possibilities are endless!

- Highlighters: These are great for emphasizing key points in your text. Just remember not to go overboard and turn your page into a rainbow!

- Post-it Notes: If you don't want to write directly on your material, or if you need more space for your thoughts, these little sticky notes can be a lifesaver.

- PDF Annotation Tools: If you're working with digital documents, tools like Adobe Reader, Preview, and others offer built-in annotation features. These can include highlighting, underlining, and adding comments.

- Online Annotation Tools: Websites like Hypothesis and Genius let you annotate web pages and share your annotations with others. They're like social media for readers!

These tools are just the tip of the iceberg. There are many other annotation tools out there, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. So, don't be afraid to experiment and find the ones that work best for you!

Let's put the definition of annotation into real-world scenarios. Here are some examples to help you get a better sense of how annotation works.

- Novels: You're reading a gripping mystery novel and you come across a clue. You underline it and jot down your theories in the margin. That's annotation!

- Textbooks: Remember the last time you studied for an exam? You probably highlighted important information and made notes to help you remember key points. That's annotation too!

- Articles: When reading a long article online, you might use a tool to underline key sections and add your own thoughts. This not only helps you understand the content better but also lets you share your insights with others. Yep, that's annotation.

- Research Papers: If you're conducting research, annotation is your best friend. Underlining important data, writing summaries of complex sections, and noting down your ideas can make the whole process much easier.

- Social Media: Ever added a funny caption to a photo before sharing it with your friends? Guess what? That's annotation too!

As you can see, annotations can be as simple or as complex as you need them to be. They're all about adding extra information to make the original content more useful or meaningful for you. So, next time you're reading something, why not give annotation a try? Who knows, you might discover some fascinating insights!

Now that we've nailed down the definition of annotation, let's see how it's applied across different disciplines. You might be surprised to know that annotation isn't just for the world of literature or academia. Here's how different fields use annotation:

- Sciences: Scientists use annotations to note down observations during experiments. They can also annotate diagrams to explain complex processes.

- Arts: Artists often annotate their sketches with notes about colors, textures, or ideas for future works. Art historians may also use annotations to provide deeper insight into famous paintings or sculptures.

- Computer Science: In the world of coding, annotations can provide extra details about how a piece of code functions. They're like a roadmap for other programmers who might need to understand or modify the code later.

- Geography: Geographers use annotations on maps to highlight specific features or explain certain phenomena. For example, they might annotate a map to show the path of a storm or the spread of a forest fire.

- Business: Business professionals annotate reports and presentations to highlight key points. This helps everyone stay on the same page and understand the main takeaways.

As you can see, no matter the discipline, the power of annotation is universal. It's all about enhancing understanding and fostering communication! So, the next time you're working on a project, why not consider how annotation could help you?

Dealing with academic or professional texts, you've probably come across both annotations and abstracts. But do you know the difference? Many people get confused between the two, but they serve unique roles. Let's clear the air by exploring the definition of annotation versus an abstract:

Annotation: An annotation adds extra information to a text. It could be a comment, explanation, or even a question. Imagine you're reading a complex scientific paper. You might annotate it by jotting down a simpler explanation of a concept in the margins. That's annotation—helping to make the text more accessible and understandable for you.

Abstract: On the other hand, an abstract is a short summary of a document's main points. Think of it as a mini version of the text. If you've ever written a research paper, you've probably had to include an abstract at the beginning. It gives readers a snapshot of what the document covers so they can decide if they want to read the whole thing.

So, in a nutshell, an annotation is more about adding value to the text, while an abstract is about summarizing it. Both have their places and can be super helpful when dealing with complex or lengthy texts. Understanding the difference between the two is another step in mastering the art of reading and writing effectively.

Now, let's shift gears and explore how annotation plays a role in the digital learning space. With the advent of technology, education isn't limited to chalkboards and textbooks anymore. We've moved onto laptops, tablets, and even mobile phones. So, where does the definition of annotation fit in this digital world?

In digital learning, annotation takes on a slightly different form. Instead of scribbling in the margins of a book, you're adding notes to a PDF, highlighting text in an eBook, or leaving comments on a shared document.

Let's say you're studying for a history exam with a friend, and you're both using the same digital textbook. You come across a paragraph that you think is particularly important, so you highlight it and leave a note saying, "Must remember for the exam!" When your friend opens the book on their device, they can see your annotation and benefit from it. This is the power of annotation in digital learning—it promotes collaboration and makes studying a more interactive experience.

And it's not just for students, either. Teachers can use digital annotation to provide feedback on assignments, clarify points in a lecture, or share additional resources. In a world where online learning is becoming the norm, understanding and using digital annotation is a skill worth mastering.

Having explored the definition of annotation in various contexts, it's exciting to imagine where it might head in the future. As we continue to integrate technology into our lives, the role and methods of annotation are likely to evolve with it.

Imagine a world where every bit of text you interact with—be it a digital book, an online article, or even a social media post—can be annotated with your thoughts, questions, or insights. And not just that, imagine those annotations being instantly shareable with anyone around the globe. We're already seeing glimpses of this in digital learning platforms, as we previously discussed.

Moreover, the rise of artificial intelligence might add another layer to annotation. Imagine AI systems that can automatically highlight important parts of a text, suggest resources for further reading, or even generate annotations based on your personal learning style. Now that's a future worth looking forward to!

While we are not there yet, the journey towards that future is already underway. And as we make strides in this direction, the definition of annotation will continue to expand and adapt. It's a fascinating field that underscores the importance of understanding, interpreting, and communicating information in our increasingly interconnected world.

If you're looking to improve your annotation skills and learn more about organizing your creative projects, check out Ansh Mehra's workshop, ' Documentation for Creative People on Notion .' This workshop will provide you with practical tips and techniques for effective annotation, as well as help you develop a comprehensive documentation system for your creative work.

Live classes every day

Learn from industry-leading creators

Get useful feedback from experts and peers

Best deal of the year

* billed annually after the trial ends.

*Billed monthly after the trial ends.

How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography: The Annotated Bibliography

- The Annotated Bibliography

- Fair Use of this Guide

Explanation, Process, Directions, and Examples

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they may describe the author's point of view, authority, or clarity and appropriateness of expression.

The Process

Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research.

First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

Critically Appraising the Book, Article, or Document

For guidance in critically appraising and analyzing the sources for your bibliography, see How to Critically Analyze Information Sources . For information on the author's background and views, ask at the reference desk for help finding appropriate biographical reference materials and book review sources.

Choosing the Correct Citation Style

Check with your instructor to find out which style is preferred for your class. Online citation guides for both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) styles are linked from the Library's Citation Management page .

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th edition, 2019) for the journal citation:

Waite, L., Goldschneider, F., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

This example uses MLA style ( MLA Handbook , 9th edition, 2021) for the journal citation. For additional annotation guidance from MLA, see 5.132: Annotated Bibliographies .

Waite, Linda J., et al. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

Versión española

Tambíen disponible en español: Cómo Preparar una Bibliografía Anotada

Content Permissions

If you wish to use any or all of the content of this Guide please visit our Research Guides Use Conditions page for details on our Terms of Use and our Creative Commons license.

Reference Help

- Next: Fair Use of this Guide >>

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2024 3:36 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

Annotated Bibliographies

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain why annotated bibliographies are useful for researchers, provide an explanation of what constitutes an annotation, describe various types of annotations and styles for writing them, and offer multiple examples of annotated bibliographies in the MLA, APA, and CBE/CSE styles of citation.

Introduction

Welcome to the wonderful world of annotated bibliographies! You’re probably already familiar with the need to provide bibliographies, reference pages, and works cited lists to credit your sources when you do a research paper. An annotated bibliography includes descriptions and explanations of your listed sources beyond the basic citation information you usually provide.

Why do an annotated bibliography?

One of the reasons behind citing sources and compiling a general bibliography is so that you can prove you have done some valid research to back up your argument and claims. Readers can refer to a citation in your bibliography and then go look up the material themselves. When inspired by your text or your argument, interested researchers can access your resources. They may wish to double check a claim or interpretation you’ve made, or they may simply wish to continue researching according to their interests. But think about it: even though a bibliography provides a list of research sources of all types that includes publishing information, how much does that really tell a researcher or reader about the sources themselves?

An annotated bibliography provides specific information about each source you have used. As a researcher, you have become an expert on your topic: you have the ability to explain the content of your sources, assess their usefulness, and share this information with others who may be less familiar with them. Think of your paper as part of a conversation with people interested in the same things you are; the annotated bibliography allows you to tell readers what to check out, what might be worth checking out in some situations, and what might not be worth spending the time on. It’s kind of like providing a list of good movies for your classmates to watch and then going over the list with them, telling them why this movie is better than that one or why one student in your class might like a particular movie better than another student would. You want to give your audience enough information to understand basically what the movies are about and to make an informed decision about where to spend their money based on their interests.

What does an annotated bibliography do?

A good annotated bibliography:

- encourages you to think critically about the content of the works you are using, their place within a field of study, and their relation to your own research and ideas.

- proves you have read and understand your sources.

- establishes your work as a valid source and you as a competent researcher.

- situates your study and topic in a continuing professional conversation.

- provides a way for others to decide whether a source will be helpful to their research if they read it.

- could help interested researchers determine whether they are interested in a topic by providing background information and an idea of the kind of work going on in a field.

What elements might an annotation include?

- Bibliography according to the appropriate citation style (MLA, APA, CBE/CSE, etc.).

- Explanation of main points and/or purpose of the work—basically, its thesis—which shows among other things that you have read and thoroughly understand the source.

- Verification or critique of the authority or qualifications of the author.

- Comments on the worth, effectiveness, and usefulness of the work in terms of both the topic being researched and/or your own research project.

- The point of view or perspective from which the work was written. For instance, you may note whether the author seemed to have particular biases or was trying to reach a particular audience.

- Relevant links to other work done in the area, like related sources, possibly including a comparison with some of those already on your list. You may want to establish connections to other aspects of the same argument or opposing views.

The first four elements above are usually a necessary part of the annotated bibliography. Points 5 and 6 may involve a little more analysis of the source, but you may include them in other kinds of annotations besides evaluative ones. Depending on the type of annotation you use, which this handout will address in the next section, there may be additional kinds of information that you will need to include.

For more extensive research papers (probably ten pages or more), you often see resource materials grouped into sub-headed sections based on content, but this probably will not be necessary for the kinds of assignments you’ll be working on. For longer papers, ask your instructor about their preferences concerning annotated bibliographies.

Did you know that annotations have categories and styles?

Decisions, decisions.

As you go through this handout, you’ll see that, before you start, you’ll need to make several decisions about your annotations: citation format, type of annotation, and writing style for the annotation.

First of all, you’ll need to decide which kind of citation format is appropriate to the paper and its sources, for instance, MLA or APA. This may influence the format of the annotations and bibliography. Typically, bibliographies should be double-spaced and use normal margins (you may want to check with your instructor, since they may have a different style they want you to follow).

MLA (Modern Language Association)

See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial for basic MLA bibliography formatting and rules.

- MLA documentation is generally used for disciplines in the humanities, such as English, languages, film, and cultural studies or other theoretical studies. These annotations are often summary or analytical annotations.

- Title your annotated bibliography “Annotated Bibliography” or “Annotated List of Works Cited.”

- Following MLA format, use a hanging indent for your bibliographic information. This means the first line is not indented and all the other lines are indented four spaces (you may ask your instructor if it’s okay to tab over instead of using four spaces).

- Begin your annotation immediately after the bibliographic information of the source ends; don’t skip a line down unless you have been told to do so by your instructor.

APA (American Psychological Association)

See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial for basic APA bibliography formatting and rules.

- Natural and social sciences, such as psychology, nursing, sociology, and social work, use APA documentation. It is also used in economics, business, and criminology. These annotations are often succinct summaries.

- Annotated bibliographies for APA format do not require a special title. Use the usual “References” designation.

- Like MLA, APA uses a hanging indent: the first line is set flush with the left margin, and all other lines are indented four spaces (you may ask your instructor if it’s okay to tab over instead of using four spaces).

- After the bibliographic citation, drop down to the next line to begin the annotation, but don’t skip an extra line.

- The entire annotation is indented an additional two spaces, so that means each of its lines will be six spaces from the margin (if your instructor has said that it’s okay to tab over instead of using the four spaces rule, indent the annotation two more spaces in from that point).

CBE (Council of Biology Editors)/CSE (Council of Science Editors)

See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial for basic CBE/CSE bibliography formatting and rules.

- CBE/CSE documentation is used by the plant sciences, zoology, microbiology, and many of the medical sciences.

- Annotated bibliographies for CBE/CSE format do not require a special title. Use the usual “References,” “Cited References,” or “Literature Cited,” and set it flush with the left margin.

- Bibliographies for CSE in general are in a slightly smaller font than the rest of the paper.

- When using the name-year system, as in MLA and APA, the first line of each entry is set flush with the left margin, and all subsequent lines, including the annotation, are indented three or four spaces.

- When using the citation-sequence method, each entry begins two spaces after the number, and every line, including the annotation, will be indented to match the beginning of the entry, or may be slightly further indented, as in the case of journals.

- After the bibliographic citation, drop down to the next line to begin the annotation, but don’t skip an extra line. The entire annotation follows the indentation of the bibliographic entry, whether it’s N-Y or C-S format.

- Annotations in CBE/CSE are generally a smaller font size than the rest of the bibliographic information.

After choosing a documentation format, you’ll choose from a variety of annotation categories presented in the following section. Each type of annotation highlights a particular approach to presenting a source to a reader. For instance, an annotation could provide a summary of the source only, or it could also provide some additional evaluation of that material.

In addition to making choices related to the content of the annotation, you’ll also need to choose a style of writing—for instance, telescopic versus paragraph form. Your writing style isn’t dictated by the content of your annotation. Writing style simply refers to the way you’ve chosen to convey written information. A discussion of writing style follows the section on annotation types.

Types of annotations

As you now know, one annotation does not fit all purposes! There are different kinds of annotations, depending on what might be most important for your reader to learn about a source. Your assignments will usually make it clear which citation format you need to use, but they may not always specify which type of annotation to employ. In that case, you’ll either need to pick your instructor’s brain a little to see what they want or use clue words from the assignment itself to make a decision. For instance, the assignment may tell you that your annotative bibliography should give evidence proving an analytical understanding of the sources you’ve used. The word analytical clues you in to the idea that you must evaluate the sources you’re working with and provide some kind of critique.

Summary annotations

There are two kinds of summarizing annotations, informative and indicative.

Summarizing annotations in general have a couple of defining features:

- They sum up the content of the source, as a book report might.

- They give an overview of the arguments and proofs/evidence addressed in the work and note the resulting conclusion.

- They do not judge the work they are discussing. Leave that to the critical/evaluative annotations.

- When appropriate, they describe the author’s methodology or approach to material. For instance, you might mention if the source is an ethnography or if the author employs a particular kind of theory.

Informative annotation

Informative annotations sometimes read like straight summaries of the source material, but they often spend a little more time summarizing relevant information about the author or the work itself.

Indicative annotation

Indicative annotation is the second type of summary annotation, but it does not attempt to include actual information from the argument itself. Instead, it gives general information about what kinds of questions or issues are addressed by the work. This sometimes includes the use of chapter titles.

Critical/evaluative

Evaluative annotations don’t just summarize. In addition to tackling the points addressed in summary annotations, evaluative annotations:

- evaluate the source or author critically (biases, lack of evidence, objective, etc.).

- show how the work may or may not be useful for a particular field of study or audience.

- explain how researching this material assisted your own project.

Combination

An annotated bibliography may combine elements of all the types. In fact, most of them fall into this category: a little summarizing and describing, a little evaluation.

Writing style

Ok, next! So what does it mean to use different writing styles as opposed to different kinds of content? Content is what belongs in the annotation, and style is the way you write it up. First, choose which content type you need to compose, and then choose the style you’re going to use to write it

This kind of annotated bibliography is a study in succinctness. It uses a minimalist treatment of both information and sentence structure, without sacrificing clarity. Warning: this kind of writing can be harder than you might think.

Don’t skimp on this kind of annotated bibliography. If your instructor has asked for paragraph form, it likely means that you’ll need to include several elements in the annotation, or that they expect a more in-depth description or evaluation, for instance. Make sure to provide a full paragraph of discussion for each work.

As you can see now, bibliographies and annotations are really a series of organized steps. They require meticulous attention, but in the end, you’ve got an entire testimony to all the research and work you’ve done. At the end of this handout you’ll find examples of informative, indicative, evaluative, combination, telescopic, and paragraph annotated bibliography entries in MLA, APA, and CBE formats. Use these examples as your guide to creating an annotated bibliography that makes you look like the expert you are!

MLA Example

APA Example

CBE Example

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bell, I. F., and J. Gallup. 1971. A Reference Guide to English, American, and Canadian Literature . Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Bizzell, Patricia, and Bruce Herzburg. 1991. Bedford Bibliography for Teachers of Writing , 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford Books.

Center for Information on Language Teaching, and The English Teaching Information Center of the British Council. 1968. Language-Teaching Bibliography . Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Engle, Michael, Amy Blumenthal, and Tony Cosgrave. 2012. “How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography.” Olin & Uris Libraries. Cornell University. Last updated September 25, 2012. https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/content/how-prepare-annotated-bibliography.

Gibaldi, Joseph. 2009. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers , 7th ed. New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

Huth, Edward. 1994. Scientific Style and Format: The CBE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers . New York: University of Cambridge.

Kilborn, Judith. 2004. “MLA Documentation.” LEO: Literacy Education Online. Last updated March 16, 2004. https://leo.stcloudstate.edu/research/mla.html.

Spatt, Brenda. 1991. Writing from Sources , 3rd ed. New York: St. Martin’s.

University of Kansas. 2018. “Bibliographies.” KU Writing Center. Last updated April 2018. http://writing.ku.edu/bibliographies .

University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2019. “Annotated Bibliography.” The Writing Center. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/annotatedbibliography/ .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Annotated Bibliography - APA 7th Ed. Style: Definition and Format: Annotated Bibliography

- Definition and Format: Annotated Bibliography

- 4 Steps to Create Your Annotated Bibliography

- Missing Citation Information and Citation Generators

- Template of Annotated Bibliography in APA Format

- Sample Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliographies

A bibliography is a list of all of your sources . (This is different than a Reference List , which includes only the sources you cited in your paper!)

An annotated bibliography includes a summary (or an annotation) for each of your sources . What is an annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography has some similarities to a References page but is more detailed.

The Reference page lists properly formatted citations (or references). However, it is for all the sources ( books, articles, documents, etc.) that you reviewed in preparation for writing the bibliography.

At the end of each citation, add a short paragraph describing each article, book, or other source listed on your References page.

What's included in an annotated bibliography's annotation section?

Your annotation/summary should tell the reader (refer to your assignment):

- A summary: what is the source about?

- Who wrote the source? Is it from a highly qualified source? (Is the author an expert on the topic? Do they work for a government agency (FBI, CDC, etc.), are they a professional journalist, or is it just a personal blog?)

- End the annotation by explaining how and where you will use this source in your paper.

Keep in mind that annotations are supposed to be a brief description of your source. You You're st summarizing the article and then briefly saying how it relates to your paper - if people reading your bibliography want to know more, they can find the work and read it directly.

Format Citations and Annotations

Format citation:.

- Note : When you copy and paste the citation, it may not match; please follow the directions below for proper format.

- Your citations should appear alphabetically by the first character of the citation.

- Your citations should all be FONT : TIMES NEW ROMAN & FONT SIZE: 12

- Instructions how to double space

Format Annotation:

Double-spaced throughout., annotation comes directly after the citation. .

- Set your Annotation back 1” from the left-hand margin (press the tab key on the keyboard).

- Use the third person – do not use “I.

- Examples: “This article discusses…” ; “In this article, the author supports…”: “This book gives a detailed view on…," “The author describes…"

YOUR ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY SHOULD LOOK LIKE THIS:

SAMPLE 2: SAMPLE BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th edition, 2019) for the journal citations:

A Monroe College Research Guide

THIS RESEARCH OR "LIBGUIDE" WAS PRODUCED BY THE LIBRARIANS OF MONROE COLLEGE

- Next: 4 Steps to Create Your Annotated Bibliography >>

- Last Updated: Jun 25, 2024 4:01 PM

- URL: https://monroecollege.libguides.com/annotated_bibliography

- Research Guides |

- Databases |

Annotated Bibliography Guide

Definition and formats.

- Elements of Annotation

An annotated bibliography is a descriptive and evaluative list of citations for books, articles, or other documents. Each citation is followed by a brief paragraph - the annotation - alerting the reader to the accuracy, quality, and relevance of that source.

Composing an annotated bibliography helps a writer to gather one's thoughts on how to use the information contained in the cited sources, and helps the reader to decide whether to pursue the full context of the information you provide.

Annotations vs. Abstracts :

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they expose the author's point of view, clarity and appropriateness of expression, and authority.

Format of the Bibliography

All of the citations in an annotated bibliography should be formatted according to one chosen style such as MLA, APA, CSE or Chicago. See the side box for manuals in the library.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Elements of Annotation >>

- Last Updated: Aug 25, 2024 7:26 PM

- URL: https://campusguides.lib.utah.edu/bibannotations

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography - APA Style (7th Edition)

What is an annotation, how is an annotation different from an abstract, what is an annotated bibliography, types of annotated bibliographies, descriptive or informative, analytical or critical, to get started.

An annotation is more than just a brief summary of an article, book, website, or other type of publication. An annotation should give enough information to make a reader decide whether to read the complete work. In other words, if the reader were exploring the same topic as you, is this material useful and if so, why?

While an abstract also summarizes an article, book, website, or other type of publication, it is purely descriptive. Although annotations can be descriptive, they also include distinctive features about an item. Annotations can be evaluative and critical as we will see when we look at the two major types of annotations.

An annotated bibliography is an organized list of sources (like a reference list). It differs from a straightforward bibliography in that each reference is followed by a paragraph length annotation, usually 100–200 words in length.

Depending on the assignment, an annotated bibliography might have different purposes:

- Provide a literature review on a particular subject

- Help to formulate a thesis on a subject

- Demonstrate the research you have performed on a particular subject

- Provide examples of major sources of information available on a topic

- Describe items that other researchers may find of interest on a topic

There are two major types of annotated bibliographies:

A descriptive or informative annotated bibliography describes or summarizes a source as does an abstract; it describes why the source is useful for researching a particular topic or question and its distinctive features. In addition, it describes the author's main arguments and conclusions without evaluating what the author says or concludes.

For example:

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulties many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a legal nurse consulting business. Pointing out issues of work-life balance, as well as the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, the author offers their personal experience as a learning tool. The process of becoming an entrepreneur is not often discussed in relation to nursing, and rarely delves into only the first year of starting a new business. Time management, maintaining an existing job, decision-making, and knowing yourself in order to market yourself are discussed with some detail. The author goes on to describe how important both the nursing professional community will be to a new business, and the importance of mentorship as both the mentee and mentor in individual success that can be found through professional connections. The article’s focus on practical advice for nurses seeking to start their own business does not detract from the advice about universal struggles of entrepreneurship makes this an article of interest to a wide-ranging audience.

An analytical or critical annotation not only summarizes the material, it analyzes what is being said. It examines the strengths and weaknesses of what is presented as well as describing the applicability of the author's conclusions to the research being conducted.

Analytical or critical annotations will most likely be required when writing for a college-level course.

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulty many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a nurse consulting business. While the article focuses on issues of work-life balance, the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, marketing, and other business issues the author’s offer of only their personal experience is brief with few or no alternative solutions provided. There is no mention throughout the article of making use of other research about starting a new business and being successful. While relying on the anecdotal advice for their list of issues, the author does reference other business resources such as the Small Business Administration to help with business planning and professional organizations that can help with mentorships. The article is a good resource for those wanting to start their own legal nurse consulting business, a good first advice article even. However, entrepreneurs should also use more business research studies focused on starting a new business, with strategies against known or expected pitfalls and issues new businesses face, and for help on topics the author did not touch in this abbreviated list of lessons learned.

Now you are ready to begin writing your own annotated bibliography.

- Choose your sources - Before writing your annotated bibliography, you must choose your sources. This involves doing research much like for any other project. Locate records to materials that may apply to your topic.

- Review the items - Then review the actual items and choose those that provide a wide variety of perspectives on your topic. Article abstracts are helpful in this process.

- The purpose of the work

- A summary of its content

- Information about the author(s)

- For what type of audience the work is written

- Its relevance to the topic

- Any special or unique features about the material

- Research methodology

- The strengths, weaknesses or biases in the material

Annotated bibliographies may be arranged alphabetically or chronologically, check with your instructor to see what he or she prefers.

Please see the APA Examples page for more information on citing in APA style.

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2023 11:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/annotated-bibliography-apa

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Annotated Bibliographies

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Definitions

A bibliography is a list of sources (books, journals, Web sites, periodicals, etc.) one has used for researching a topic. Bibliographies are sometimes called "References" or "Works Cited" depending on the style format you are using. A bibliography usually just includes the bibliographic information (i.e., the author, title, publisher, etc.).

An annotation is a summary and/or evaluation. Therefore, an annotated bibliography includes a summary and/or evaluation of each of the sources. Depending on your project or the assignment, your annotations may do one or more of the following.

For more help, see our handout on paraphrasing sources.

For more help, see our handouts on evaluating resources .

- Reflect : Once you've summarized and assessed a source, you need to ask how it fits into your research. Was this source helpful to you? How does it help you shape your argument? How can you use this source in your research project? Has it changed how you think about your topic?

Your annotated bibliography may include some of these, all of these, or even others. If you're doing this for a class, you should get specific guidelines from your instructor.

Why should I write an annotated bibliography?

To learn about your topic : Writing an annotated bibliography is excellent preparation for a research project. Just collecting sources for a bibliography is useful, but when you have to write annotations for each source, you're forced to read each source more carefully. You begin to read more critically instead of just collecting information. At the professional level, annotated bibliographies allow you to see what has been done in the literature and where your own research or scholarship can fit. To help you formulate a thesis: Every good research paper is an argument. The purpose of research is to state and support a thesis. So, a very important part of research is developing a thesis that is debatable, interesting, and current. Writing an annotated bibliography can help you gain a good perspective on what is being said about your topic. By reading and responding to a variety of sources on a topic, you'll start to see what the issues are, what people are arguing about, and you'll then be able to develop your own point of view.

To help other researchers : Extensive and scholarly annotated bibliographies are sometimes published. They provide a comprehensive overview of everything important that has been and is being said about that topic. You may not ever get your annotated bibliography published, but as a researcher, you might want to look for one that has been published about your topic.

The format of an annotated bibliography can vary, so if you're doing one for a class, it's important to ask for specific guidelines.

The bibliographic information : Generally, though, the bibliographic information of the source (the title, author, publisher, date, etc.) is written in either MLA or APA format. For more help with formatting, see our MLA handout . For APA, go here: APA handout .

The annotations: The annotations for each source are written in paragraph form. The lengths of the annotations can vary significantly from a couple of sentences to a couple of pages. The length will depend on the purpose. If you're just writing summaries of your sources, the annotations may not be very long. However, if you are writing an extensive analysis of each source, you'll need more space.

You can focus your annotations for your own needs. A few sentences of general summary followed by several sentences of how you can fit the work into your larger paper or project can serve you well when you go to draft.

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Reading and Study Strategies

What is annotating and why do it, annotation explained, steps to annotating a source, annotating strategies.

- Using a Dictionary

- Study Skills

[ Back to resource home ]

[email protected] 509.359.2779

Cheney Campus JFK Library Learning Commons

Stay Connected!

inside.ewu.edu/writerscenter Instagram Facebook

Helpful Links

Software for Annotating

ProQuest Flow (sign up with your EWU email)

FoxIt PDF Reader

Adobe Reader Pro - available on all campus computers

Track Changes in Microsoft Word

What is Annotating?

Annotating is any action that deliberately interacts with a text to enhance the reader's understanding of, recall of, and reaction to the text. Sometimes called "close reading," annotating usually involves highlighting or underlining key pieces of text and making notes in the margins of the text. This page will introduce you to several effective strategies for annotating a text that will help you get the most out of your reading.

Why Annotate?

By annotating a text, you will ensure that you understand what is happening in a text after you've read it. As you annotate, you should note the author's main points, shifts in the message or perspective of the text, key areas of focus, and your own thoughts as you read. However, annotating isn't just for people who feel challenged when reading academic texts. Even if you regularly understand and remember what you read, annotating will help you summarize a text, highlight important pieces of information, and ultimately prepare yourself for discussion and writing prompts that your instructor may give you. Annotating means you are doing the hard work while you read, allowing you to reference your previous work and have a clear jumping-off point for future work.

1. Survey : This is your first time through the reading

You can annotate by hand or by using document software. You can also annotate on post-its if you have a text you do not want to mark up. As you annotate, use these strategies to make the most of your efforts:

- Include a key or legend on your paper that indicates what each marking is for, and use a different marking for each type of information. Example: Underline for key points, highlight for vocabulary, and circle for transition points.

- If you use highlighters, consider using different colors for different types of reactions to the text. Example: Yellow for definitions, orange for questions, and blue for disagreement/confusion.

- Dedicate different tasks to each margin: Use one margin to make an outline of the text (thesis statement, description, definition #1, counter argument, etc.) and summarize main ideas, and use the other margin to note your thoughts, questions, and reactions to the text.

Lastly, as you annotate, make sure you are including descriptions of the text as well as your own reactions to the text. This will allow you to skim your notations at a later date to locate key information and quotations, and to recall your thought processes more easily and quickly.

- Next: Using a Dictionary >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_read_study_strategies

Information Literacy Research Skill Building: What is an Annotation?

- Basic Timeline for Information

- Research Process Podcast

- Library Lingo

- Popular vs Scholarly Sources

- Primary vs Secondary Sources

- Advanced Database Searching

- Advanced Searching Techniques

- Choosing Search Terms video

- Database Evaluation

- Dissertations and Theses

- Identifying Main Concepts

- Citations to Articles

- Journal Title Abbreviations – Finding the Real Title

- Evaluating Sources: The CRAAP Test

- Peer Reviewed Journals, Refereed, and Juried Journals

- Popular vs Scholarly Information

- Article Evaluation Flow Chart

What is an Annotation?

- Most of us are probably more familiar with seeing or writing “summaries” or “abstracts” of articles or information we find. Summaries or abstracts basically rehash the content of the material. Writing annotations, however, require a different approach. Annotations, on the other hand, look at the material a little more objectively. When writing an annotation, you should consider who wrote it and why. Consult the Elements of an Annotation below for more detail.

Elements of an Annotation

- Identification and qualifications of the author: Did a journalist, scientist, politician, professor, or a lay person write the material? What do you know about the person?

- Major thesis, theories and ideas: What is the basic idea the author is trying to convey? What is the message?

- Audience and level of reading difficulty: For whom is the article written? Does the author use simple language? Scientific language? A particular jargon or specialized terms?

- Bias or standpoint of the author in relation to his theme: Does the author have a particular axe to grind, point to make, or something to sell (even if it is an idea)? What does the author have to gain or lose?

- Relationship of the work to other works in the field: Compared to other things you have read about the topic, what does this particular source add to your knowledge? Why is it worthy of inclusion into your project? What purpose does it serve? (This means you have to have already read a number of other materials on the topic before you can accurately annotate something.)

- Conclusions, findings, results : What is your basic assessment of the article based on everything else you know?

- Special features. If the work is long enough (a book or extensive article) you may want to briefly explain how it is organized. If there are indexes, statistical tables, pictures, or a bibliography, your reader will want to know.

- Annotations are short - not over 150 words. Because annotations are usually just a paragraph long, they need to be very succinct and to the point. You shouldn’t feel like you need to add “filler” information, especially if you cover all the annotation elements listed above. Annotations are also written in 3rd person.

Article Annotation Activity

- After you read the annotation, see if you can identify which annotation elements correspond with the bold text you see in the text of the annotation.

- Remember, there is no one correct to annotate an article, as long as most of the seven elements outlined above are addressed. When you evaluate an information source, pick out and make judgments about what you think is important based on how the item relates to your research.

Article Annotation

- Annotation of “Tells of Vaccine to Stop Influenza.” New York Times. October 2, 1918. ProQuest Historical News York Times (1851-2003). Pg. 10: This primary source article was written at the time of the 1918 flu outbreak by a New York Times journalist. It is a basic, unbiased report of information the author received from the U.S. Army. As a NYT’s article, it was written for the public at a basic reading level , and accounts for the development of immunization against the Spanish Flu . This would have been spectacular news at this point in time. The article, it turns out, was not accurate , as no immunization against the flu was ever found. In the second paragraph, there is evidence that Army doctors reporting this information have an interest in consoling the American public from “undue alarm.” This comment by Dr. Copeland, Health Commissioner of New York City, supports the idea that there was great concern in keeping the public confident that the matter was under control – even when the worst of the pandemic was hitting America. ACTIVITY: Look at the text in bold in the annotation above. Try to match each phrase in bold font with one of the seven annotation elements listed on the front of this handout. There may be more than one answer for each phrase you see in bold.

Original Article

- << Previous: Using Information

- Next: Plagiarism >>

- Last Updated: May 19, 2022 1:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.wsu.edu/infolit

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Citing sources

- What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

Published on March 9, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 23, 2022.

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that includes a short descriptive text (an annotation) for each source. It may be assigned as part of the research process for a paper , or as an individual assignment to gather and read relevant sources on a topic.

Scribbr’s free Citation Generator allows you to easily create and manage your annotated bibliography in APA or MLA style. To generate a perfectly formatted annotated bibliography, select the source type, fill out the relevant fields, and add your annotation.

An example of an annotated source is shown below:

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Annotated bibliography format: apa, mla, chicago, how to write an annotated bibliography, descriptive annotation example, evaluative annotation example, reflective annotation example, finding sources for your annotated bibliography, frequently asked questions about annotated bibliographies.

Make sure your annotated bibliography is formatted according to the guidelines of the style guide you’re working with. Three common styles are covered below:

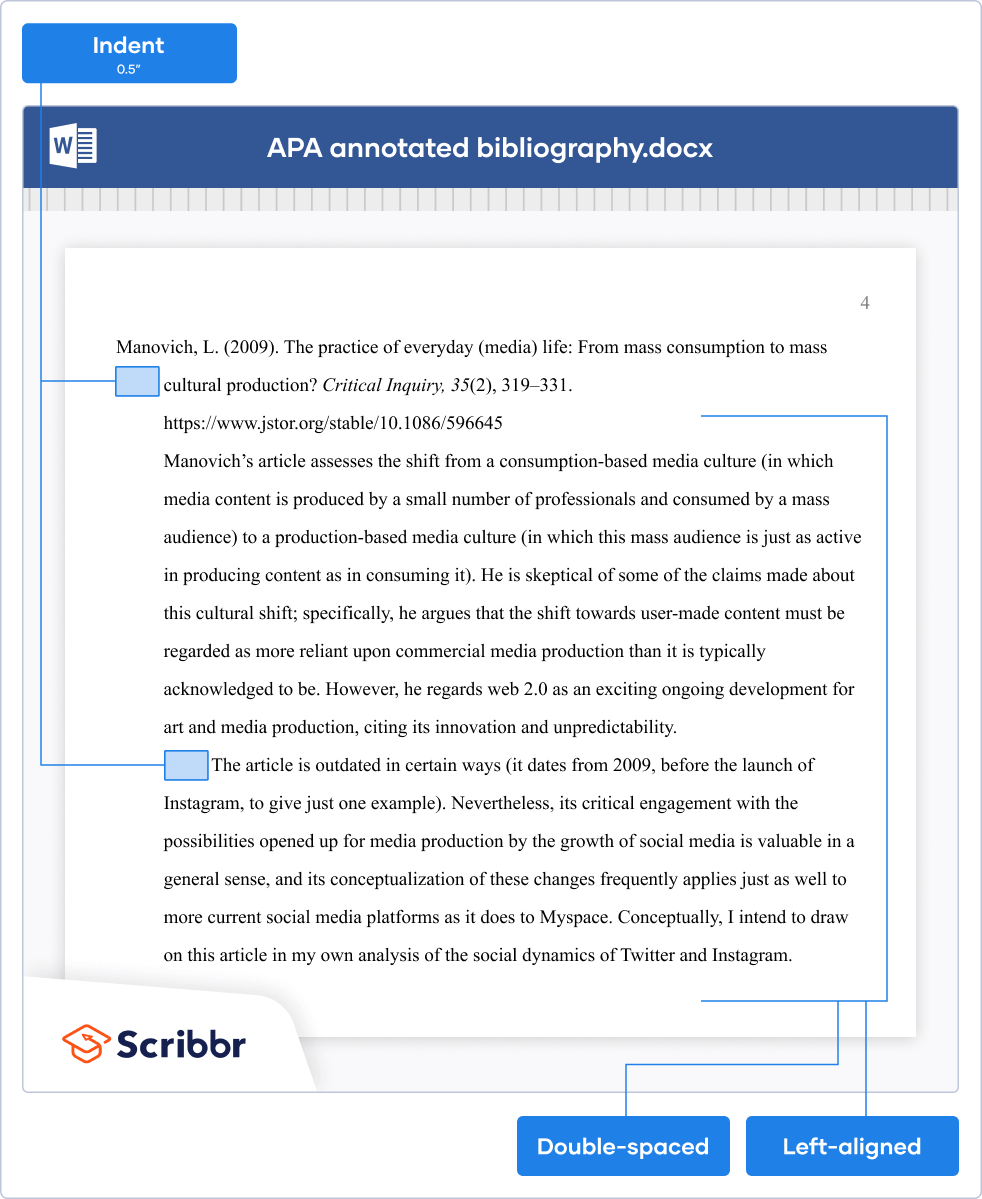

In APA Style , both the reference entry and the annotation should be double-spaced and left-aligned.

The reference entry itself should have a hanging indent . The annotation follows on the next line, and the whole annotation should be indented to match the hanging indent. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

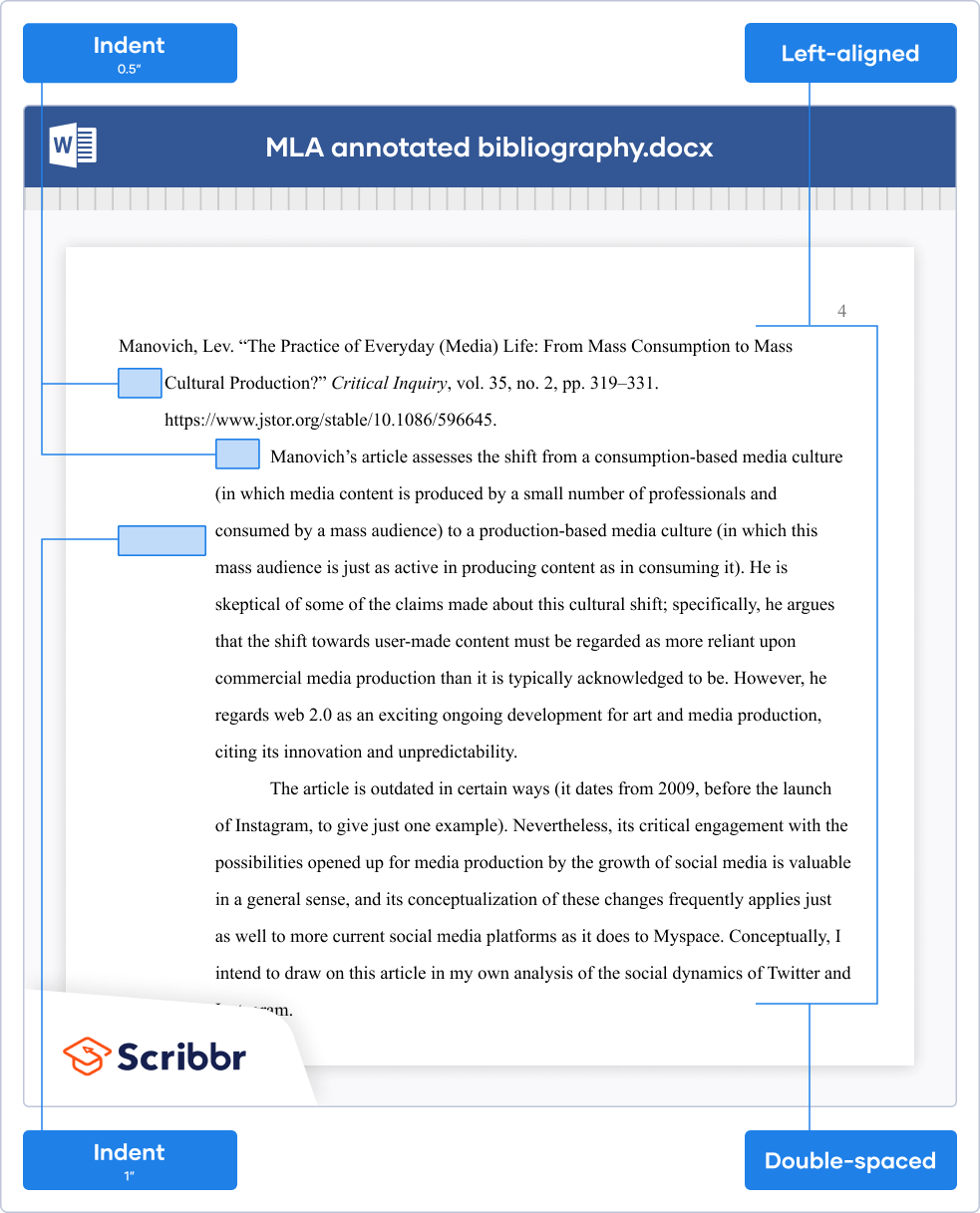

In an MLA style annotated bibliography , the Works Cited entry and the annotation are both double-spaced and left-aligned.

The Works Cited entry has a hanging indent. The annotation itself is indented 1 inch (twice as far as the hanging indent). If there are two or more paragraphs in the annotation, the first line of each paragraph is indented an additional half-inch, but not if there is only one paragraph.

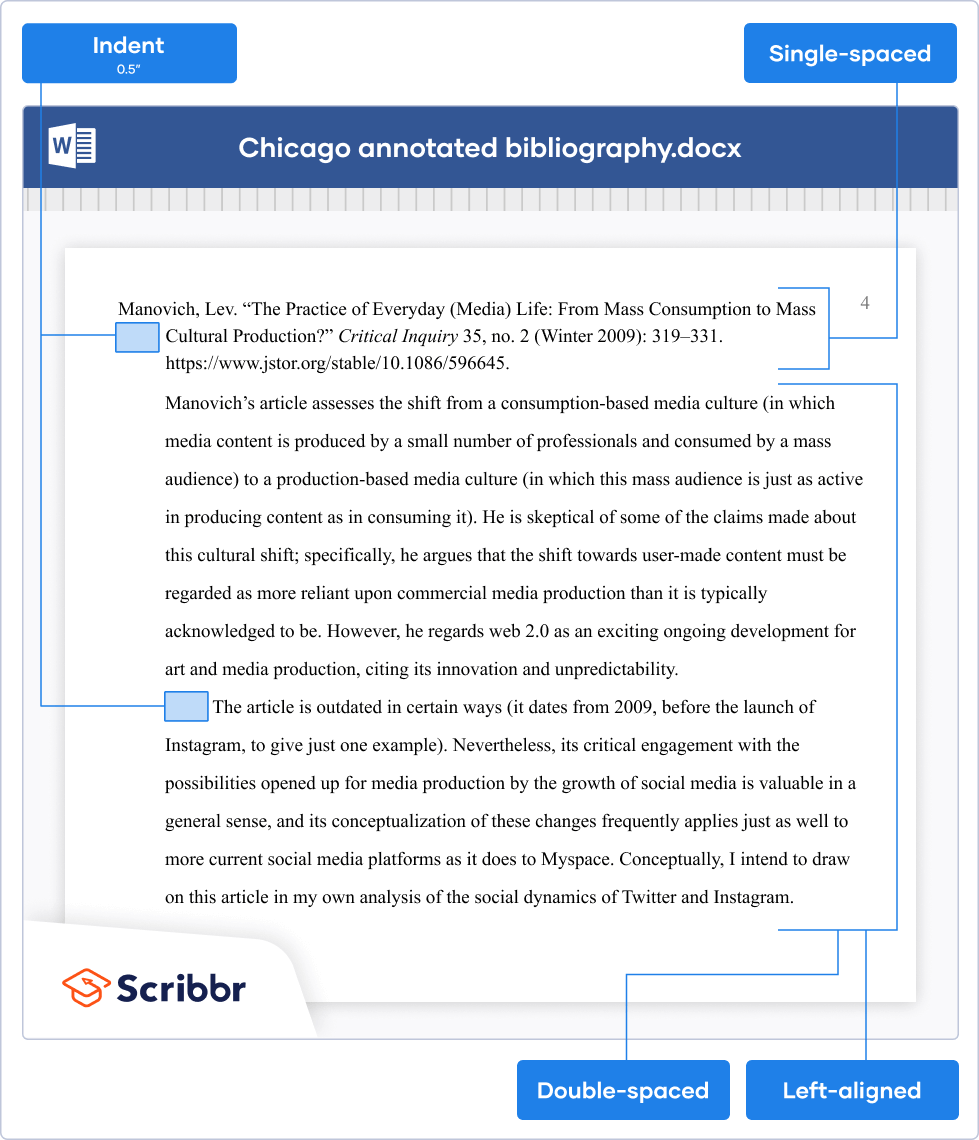

Chicago style

In a Chicago style annotated bibliography , the bibliography entry itself should be single-spaced and feature a hanging indent.

The annotation should be indented, double-spaced, and left-aligned. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

For each source, start by writing (or generating ) a full reference entry that gives the author, title, date, and other information. The annotated bibliography format varies based on the citation style you’re using.

The annotations themselves are usually between 50 and 200 words in length, typically formatted as a single paragraph. This can vary depending on the word count of the assignment, the relative length and importance of different sources, and the number of sources you include.

Consider the instructions you’ve been given or consult your instructor to determine what kind of annotations they’re looking for:

- Descriptive annotations : When the assignment is just about gathering and summarizing information, focus on the key arguments and methods of each source.

- Evaluative annotations : When the assignment is about evaluating the sources , you should also assess the validity and effectiveness of these arguments and methods.

- Reflective annotations : When the assignment is part of a larger research process, you need to consider the relevance and usefulness of the sources to your own research.

These specific terms won’t necessarily be used. The important thing is to understand the purpose of your assignment and pick the approach that matches it best. Interactive examples of the different styles of annotation are shown below.

A descriptive annotation summarizes the approach and arguments of a source in an objective way, without attempting to assess their validity.

In this way, it resembles an abstract , but you should never just copy text from a source’s abstract, as this would be considered plagiarism . You’ll naturally cover similar ground, but you should also consider whether the abstract omits any important points from the full text.

The interactive example shown below describes an article about the relationship between business regulations and CO 2 emissions.

Rieger, A. (2019). Doing business and increasing emissions? An exploratory analysis of the impact of business regulation on CO 2 emissions. Human Ecology Review , 25 (1), 69–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26964340

An evaluative annotation also describes the content of a source, but it goes on to evaluate elements like the validity of the source’s arguments and the appropriateness of its methods .

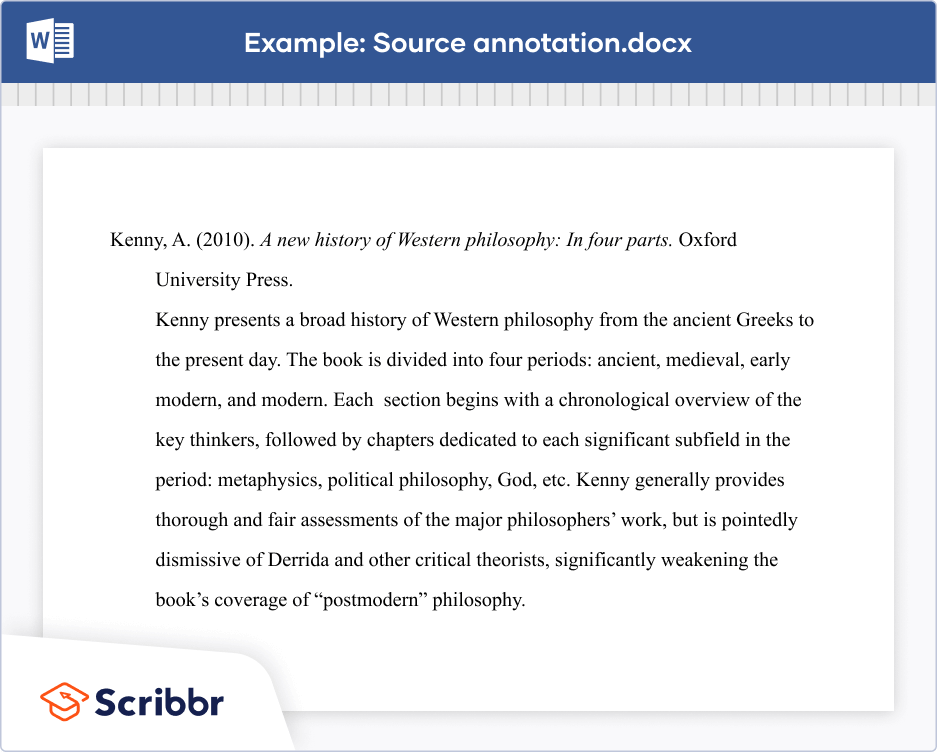

For example, the following annotation describes, and evaluates the effectiveness of, a book about the history of Western philosophy.

Kenny, A. (2010). A new history of Western philosophy: In four parts . Oxford University Press.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

A reflective annotation is similar to an evaluative one, but it focuses on the source’s usefulness or relevance to your own research.

Reflective annotations are often required when the point is to gather sources for a future research project, or to assess how they were used in a project you already completed.

The annotation below assesses the usefulness of a particular article for the author’s own research in the field of media studies.

Manovich, Lev. (2009). The practice of everyday (media) life: From mass consumption to mass cultural production? Critical Inquiry , 35 (2), 319–331. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/596645

Manovich’s article assesses the shift from a consumption-based media culture (in which media content is produced by a small number of professionals and consumed by a mass audience) to a production-based media culture (in which this mass audience is just as active in producing content as in consuming it). He is skeptical of some of the claims made about this cultural shift; specifically, he argues that the shift towards user-made content must be regarded as more reliant upon commercial media production than it is typically acknowledged to be. However, he regards web 2.0 as an exciting ongoing development for art and media production, citing its innovation and unpredictability.

The article is outdated in certain ways (it dates from 2009, before the launch of Instagram, to give just one example). Nevertheless, its critical engagement with the possibilities opened up for media production by the growth of social media is valuable in a general sense, and its conceptualization of these changes frequently applies just as well to more current social media platforms as it does to Myspace. Conceptually, I intend to draw on this article in my own analysis of the social dynamics of Twitter and Instagram.

Before you can write your annotations, you’ll need to find sources . If the annotated bibliography is part of the research process for a paper, your sources will be those you consult and cite as you prepare the paper. Otherwise, your assignment and your choice of topic will guide you in what kind of sources to look for.

Make sure that you’ve clearly defined your topic , and then consider what keywords are relevant to it, including variants of the terms. Use these keywords to search databases (e.g., Google Scholar ), using Boolean operators to refine your search.

Sources can include journal articles, books, and other source types , depending on the scope of the assignment. Read the abstracts or blurbs of the sources you find to see whether they’re relevant, and try exploring their bibliographies to discover more. If a particular source keeps showing up, it’s probably important.

Once you’ve selected an appropriate range of sources, read through them, taking notes that you can use to build up your annotations. You may even prefer to write your annotations as you go, while each source is fresh in your mind.

An annotated bibliography is an assignment where you collect sources on a specific topic and write an annotation for each source. An annotation is a short text that describes and sometimes evaluates the source.

Any credible sources on your topic can be included in an annotated bibliography . The exact sources you cover will vary depending on the assignment, but you should usually focus on collecting journal articles and scholarly books . When in doubt, utilize the CRAAP test !

Each annotation in an annotated bibliography is usually between 50 and 200 words long. Longer annotations may be divided into paragraphs .

The content of the annotation varies according to your assignment. An annotation can be descriptive, meaning it just describes the source objectively; evaluative, meaning it assesses its usefulness; or reflective, meaning it explains how the source will be used in your own research .

A source annotation in an annotated bibliography fulfills a similar purpose to an abstract : they’re both intended to summarize the approach and key points of a source.

However, an annotation may also evaluate the source , discussing the validity and effectiveness of its arguments. Even if your annotation is purely descriptive , you may have a different perspective on the source from the author and highlight different key points.