The Reporter

New Evidence on the Impacts of Birth Order

What determines a child's success? We know that family matters — children from higher socioeconomic status families do better in school, get more education, and earn more.

However, even beyond that, there is substantial variation in success across children within families. This has led researchers to study factors that relate to within-family differences in children's outcomes. One that has attracted much interest is the role played by birth order, which varies systematically within families and is exogenously determined.

While economists have been interested in understanding human capital development for many decades, compelling economic research on birth order is more recent and has largely resulted from improved availability of data. Early work on birth order was hindered by the stringent data requirements necessary to convincingly identify the effects of birth order. Most importantly, one needs information on both family size and birth order. As there is only a third-born child in a family with at least three children, comparing third-borns to firstborns across families of different sizes will conflate the birth order effect with a family size effect, so one needs to be able to control for family size. Additionally, it is beneficial to have information on multiple children from the same family so that birth order effects can be estimated from within-family differences in child outcomes; otherwise, birth order effects will be conflated with other effects that vary systematically with birth order, such as cohort effects. Large Scandinavian register datasets that became available to researchers beginning in the late 1990s have enabled birth order research, as they contain population data on both family structure and a variety of child outcomes. Here, I describe my research with a number of coauthors, using these data to explore the effects of birth order on outcomes including human capital accumulation, earnings, development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and health.

Birth Order and Economic Success

Almost a half-century ago, economists including Gary Becker, H. Gregg Lewis, and Nigel Tomes created models of quality-quantity trade-offs in child-rearing and used these models to explore the role of family in children's success. They sought to explain an observed negative correlation between family income and family size: if child quality is a normal good, as income rises the family demands higher-quality children at the cost of lower family size. 1

However, this was a difficult model to test, as characteristics other than family income and child quality vary with family size. The introduction of natural experiments, combined with newly available large administrative datasets from Scandinavia, made testing such a model possible.

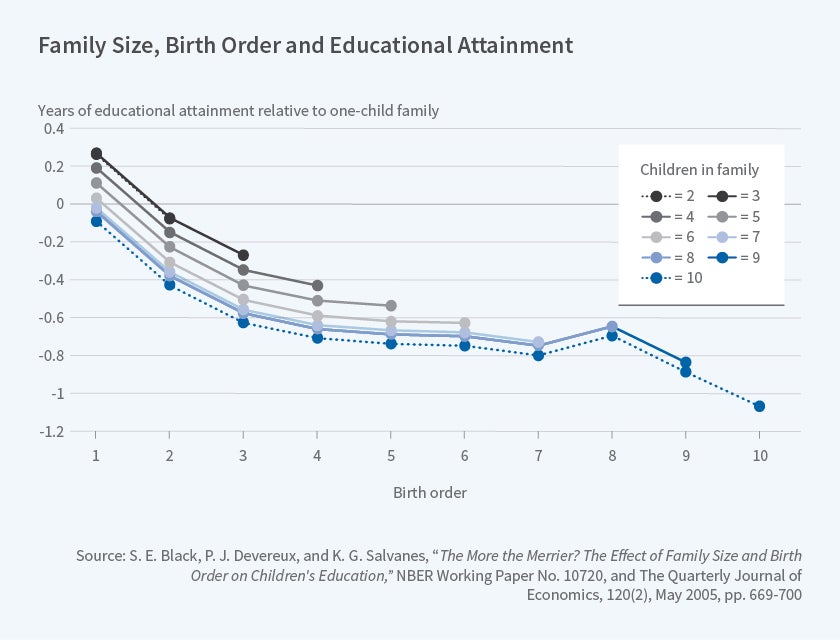

In my earliest work on the topic, Paul Devereux, Kjell Salvanes, and I took advantage of the Norwegian administrative dataset and set out to better understand this theoretical quantity-quality tradeoff. 2 It became clear that child "quality" was not a constant within a family — children within families were quite different, despite the model assumptions to the contrary. Indeed, we found that birth order could explain a large fraction of the family size differential in children's educational outcomes. Average educational attainment was lower in larger families largely because later-born children had lower average education, rather than because firstborns had lower education in large families than in small families. We found that firstborns had higher educational attainment than second-borns who in turn did better than third-borns, and so on. These results were robust to a variety of specifications; most importantly, we could compare outcomes of children within the same families.

To give a sense of the magnitude of these effects: The difference in educational attainment between the first child and the fifth child in a five-child family is roughly equal to the difference between the educational attainment of blacks and whites calculated from the 2000 Census. We augmented the education results by examining earnings, whether full-time employed, and whether one had a child as a teenager as additional outcome variables, and found strong evidence for birth order effects, particularly for women. Later-born women have lower earnings (whether employed full-time or not), are less likely to work full-time, and are more likely to have their first child as teenagers. In contrast, while later-born men have lower full-time earnings, they are not less likely to work full-time [Figure 1].

Birth Order and Cognitive Skills

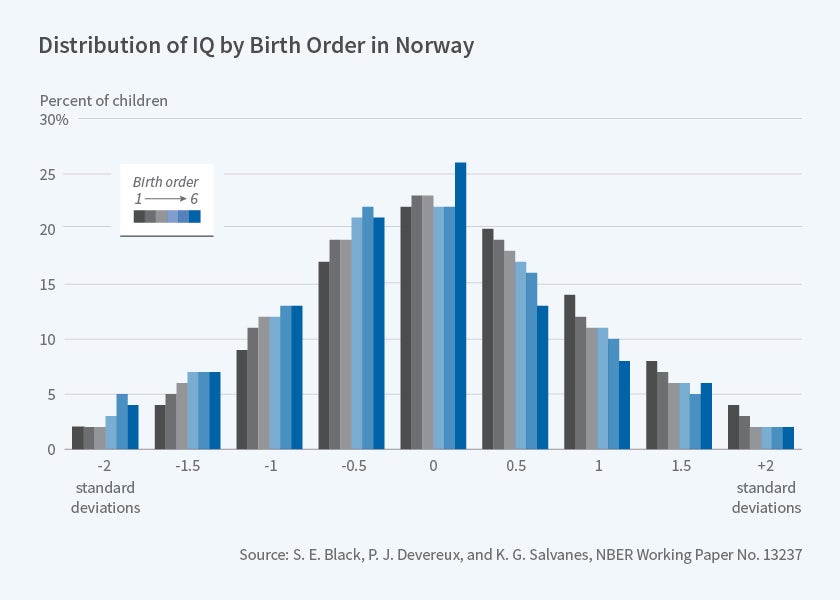

One possible explanation for these differences is that cognitive ability varies systematically by birth order. In subsequent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I examined the effect of birth order on IQ scores. 3

The psychology literature has long debated the role of birth order in determining children's IQs; this debate was seemingly resolved when, in 2000, J. L. Rodgers et al. published a paper in American Psychologist entitled "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence" that referred to the apparent relationship between birth order and IQ as a "methodological illusion." 4 However, this work was limited due to the absence of large representative datasets necessary to identify these effects. We again used population register data from Norway to estimate this relationship.

To measure IQ, we used the outcomes of standardized cognitive tests administered to Norwegian men between the age of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military. Consistent with our earlier findings on educational attainment but in contrast to the previous work in the literature, we found strong birth order effects on IQ that are present when we look within families. Later-born children have lower IQs, on average, and these differences are quite large. For example, the difference between firstborn and second-born average IQ is on the order of one-fifth of a standard deviation, or about three IQ points. This translates into approximately a 2 percent difference in annual earnings in adulthood.

The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Skills

Personality is another factor that is posited to vary by birth order, a proposition that has been particularly difficult to assess in a compelling way due to the paucity of large datasets containing information on individual personality. In recent work on the topic, Erik Gronqvist, Bjorn Ockert, and I use Swedish administrative datasets to examine this issue. 5

In the economics literature, personality traits are often referred to as non-cognitive abilities and denote traits that can be distinguished from intelligence. 6 To measure "personality" (or non-cognitive skills), we use the outcome of a standardized psychological evaluation, conducted by a certified psychologist, that is performed on all Swedish men between the ages of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military, and which is strongly related to success in the labor market. An individual is given a higher score if he is considered to be emotionally stable, persistent, socially outgoing, willing to assume responsibility, and able to take initiative. Similar to the results for cognitive skills, we find evidence of consistently lower scores in this measure for later-born children. Third-born children have non-cognitive abilities that are 0.2 standard deviations below firstborn children. Interestingly, boys with older brothers suffer almost twice as much in terms of these personality characteristics as boys with older sisters.

Importantly, we also demonstrate that these personality differences translate into differences in occupation choice by birth order. Firstborn children are significantly more likely to be employed and to work as top managers, while later-born children are more likely to be self-employed. More generally, firstborn children are more likely to be in occupations requiring sociability, leadership ability, conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness.

The Effect of Birth Order on Health

Finally, how do these differences translate into later health? In more recent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I analyze the effect of birth order on health. 7 There is a sizable body of literature about the relationship between birth order and adult health; individual studies have typically examined only one or a small number of health outcomes and, in many cases, have used relatively small samples. Again, we use large nationally representative data from Norway to identify the relationship between birth order and health when individuals are in their 40s, where health is measured along a number of dimensions, including medical indicators, health behaviors, and overall life satisfaction.

The effects of birth order on health are less straightforward than other outcomes we have examined, as firstborns do better on some dimensions and worse on others. We find that the probability of having high blood pressure declines with birth order, and the largest gap is between first- and second-borns. Second-borns are about 3 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns; fifth-borns are about 7 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns. Given that 24 percent of this population has high blood pressure, this is quite a large difference. Firstborns are also more likely to be overweight and obese. Compared with second-borns, firstborns are 4 percent more likely to be overweight and 2 percent more likely to be obese. The equivalent differences between fifth-borns and firstborns are 10 percent and 5 percent. For context, 47 percent of the population is overweight and 10 percent is obese. Once again, the magnitudes are quite large.

However, later-borns are less likely to consider themselves to be in good health, and measures of mental health generally decline with birth order. Later-born children also exhibit worse health behaviors. The number of cigarettes smoked daily increases monotonically with birth order, suggesting that the higher prevalence of smoking by later-borns found among U.S. adolescents by Laura M. Argys et al. 8 may persist throughout adulthood and, hence, have important effects on health outcomes.

Possible Mechanisms

Why are adult outcomes likely to be affected by birth order? A host of potential explanations has been proposed across several academic disciplines.

A number of biological factors may explain birth order effects. These relate to changes in the womb environment or maternal immune system that occur over successive births. Beyond biology, parents could have other influences. Childhood inputs, especially in the first years of life, are considered crucial for skill formation. 9 Firstborn children have the full attention of parents, but as families grow the family environment is diluted and parental resources become scarcer. 10 In contrast, parents are more experienced and tend to have higher incomes when raising later-born children. In addition, for a given amount of resources, parents may treat firstborn children differently than second- or later-born children. Parents may use more strict parenting practices toward the firstborn, so as to gain a reputation for "toughness" necessary to induce good behavior among later-borns. 11

There are also theories that suggest that interactions among siblings can shape birth order effects. For example, based on evolutionary psychology, Frank J. Sulloway suggests that firstborns have an advantage in following the status quo, while later-borns — by having incentives to engage in investments aimed at differentiating themselves — become more sociable and unconventional in order to attract parental resources. 12

In each of these papers, we attempted to identify potential mechanisms for the patterns we observed. However, it is here we see the limitations of these large administrative datasets, as for the most part, we lack necessary detailed information on biological factors and on household dynamics when the children are young. However, we do have some evidence on the role of biological factors. Later-born children tend to have better birth outcomes as measured by factors such as birth weight. In our Swedish data, we took advantage of the fact that some children's biological birth order is different from their environmental birth order, due to the death of an older sibling or because their parent gave up a child for adoption. When we examine this subsample, we find that the birth order effect on occupational choice is entirely driven by the environmental birth order, again suggesting that biological factors may not be central.

Also in our Swedish study, we found that firstborn teenagers are more likely to read books, spend more time on homework, and spend less time watching TV or playing video games. Parents spend less time discussing school work with later-born children, suggesting there may be differences in parental time investments. Using Norwegian data, we found that smoking early in pregnancy is more prevalent for first pregnancies than for later ones. However, women are more likely to quit smoking during their first pregnancy than during later ones, and firstborns are more likely to be breastfed. These findings suggest that early investments may systematically benefit firstborns and help explain their generally better outcomes.

In the past two decades, with the increased accessibility of administrative datasets on large swaths of the population, economists and other researchers have been better able to identify the role of birth order in the outcomes of children. There is strong evidence of substantial differences by birth order across a range of outcomes. While I have described several of my own papers on the topic, a number of other researchers have also taken advantage of newly available datasets in Florida and Denmark to examine the role of birth order on other important outcomes, specifically juvenile delinquency and later criminal behavior. 13 Consistent with the work discussed here, later-born children experience higher rates of delinquency and criminal behavior; this is at least partly attributable to time investments of parents.

Researchers

More from nber.

G. Becker, "An Economic Analysis of Fertility," in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries , New York, Columbia University Press, 1960, pp. 209-40; G. Becker and H. Lewis, "Interaction Between Quantity and Quality of Children," in Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital , 1974, pp. 81-90; G. Becker and N. Tomes, "Child Endowments, and the Quantity and Quality of Children," NBER Working Paper 123 , February 1976.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "The More the Merrier? The Effect of Family Composition on Children's Education" NBER Working Paper 10720 , September 2004, and Quarterly Journal of Economics , 120(2), 2005, pp. 669-700.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "Older and Wiser? Birth Order and the IQ of Young Men," NBER Working Paper 13237 , July 2007, and CESifo Economic Studies , Oxford University Press, vol. 57(1), pages 103-20, March 2011.

J. Rodgers, H. Cleveland, E. van den Oord, and D. Rowe, "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence," American Psychologist , 55(6), 2000, pp. 599-612.

S. Black, E. Gronqvist, and B. Ockert, "Born to Lead? The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Abilities," NBER Working Paper 23393 , May 2017.

L. Borghans, A. Duckworth, J. Heckman, and B. ter Weel, "The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits," Journal of Human Resources , 43, 2008, pp. 972-1059.

S. Black, P. Devereux, K. Salvanes, "Healthy (?), Wealthy, and Wise: Birth Order and Adult Health, NBER Working Paper 21337 , July 2015.

L. Argys, D. Rees, S. Averett, and B. Witoonchart, "Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior," Economic Inquiry , 44(2), 2006, pp. 215-33.

F. Cunha and J. Heckman, "The Technology of Skill Formation," NBER Working Paper 12840 , January 2007.

R. Zajonc and G. Markus, "Birth Order and Intellectual Development," Psychological Review , 82(1), 1975, pp. 74-88; R. Zajonc, "Family Configuration and Intelligence," Science , 192(4236), 1976, pp. 227-36; J. Price, "Parent-Child Quality Time: Does Birth Order Matter?" in Journal of Human Resources , 43(1), 2008, pp. 240-65; J.Lehmann, A. Nuevo-Chiquero, and M. Vidal-Fernandez, "The Early Origins of Birth Order Differences in Children's Outcomes and Parental Behavior," forthcoming in Journal of Human Resources .

V. Hotz and J. Pantano, "Strategic Parenting, Birth Order, and School Performance," NBER Working Paper 19542 , October 2013, and Journal of Population Economics , 28(4), 2015, pp. 911-936. ↩

F. Sulloway, Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives , New York, Pantheon Books, 1996.

S. Breining, J. Doyle, D. Figlio, K. Karbownik, J. Roth, "Birth Order and Delinquency: Evidence from Denmark and Florida," NBER Working Paper 23038 , January 2017.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Does Birth Order Shape Your Personality?

Beware the stereotypes

Verywell Mind / Getty Images

What Is Adler’s Birth Order Theory?

First-born child, middle child.

- Impact on Relationships

Debunking Myths and Limitations

Birth order refers to the order a child is born in relation to their siblings, such as whether they are first-born, middle-born, or last-born. You’ve probably heard people joke about how the eldest child is the bossy one, the middle child is the peace-maker, and the youngest child is the irresponsible rebel—but is there any truth to these stereotypes?

Psychologists often look at how birth order can affect development, behavior patterns, and personality characteristics, and there is some evidence that birth order might play a role in certain aspects of personality .

At a Glance

Researchers often explore how birth order, including the differences in parental expectations and sibling dynamics, can affect development and character. According to some researchers, firstborns, middle children, youngest-children, and only child-children often exhibit distinctive characteristics that are strongly influenced by how birth order shapes parental and sibling behaviors.

Early in the 20th century, the Austrian psychiatrist Alfred Adler introduced the idea that birth order could impact development and personality. Adler, the founder of individual psychology, was heavily influenced by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud .

Key points of Adler's birth order theory were that firstborns were more likely to develop a strong sense of responsibility, middleborns a desire for attention, and lastborns a sense of adventure and rebellion.

Adler also notably introduced the concept of the " family constellation ." This idea emphasizes the dynamics that form between family members and how these interactions play a part in shaping individual development.

Adler's birth order theory suggests that firstborns get more attention and time from their parents. New parents are still learning about child-rearing, which means that they may be more rule-oriented, strict, cautious, and sometimes even neurotic .

They are often described as responsible leaders with Type A personalities , a phenomenon sometimes referred to as " oldest-child syndrome ."

"Older siblings, regardless of gender, often feel more deprived or envious since they have experienced having another child divert attention away from them at some point in their lives. They tend to be more success-oriented,” explains San Francisco therapist Dr. Avigail Lev.

Firstborn children are often described as:

- High-achieving (or sometimes even over-achieving )

- Structured and organized

- Responsible

All this extra attention firstborns enjoy changes abruptly when younger siblings come along. When you become an older sibling, you suddenly have to share your parent's attention. You may feel that your parents have higher expectations for you and look to you to set an example for your younger siblings.

Consider the experiences of the oldest siblings, who are frequently tasked with caring for younger siblings. Because they are often expected to help fill the role of caregivers, they may be more nurturing, responsible, and motivated to excel.

Such traits are affected not only by birth order but also by how your position in the family affects your parent's expectations and your relationship with your younger siblings.

Research has found that firstborn kids tend to have more advanced cognitive development , which may also confer advantages when it comes to school readiness skills. However, it's important to remember that being the oldest child can also come with challenges, including carrying the weight of expectations and the burden of taking a caregiver role within the family.

Adler suggested that middle children tend to become the family’s peacemaker since they often have to mediate conflicts between older and younger siblings. Because they tend to be overshadowed by their eldest siblings, middle children may seek social attention outside of the family.

In families with three children, the youngest male sibling is likely to be more passive or easy-going.

Middleborns are often described as:

- Independent

- Peacemakers

- People pleasers

- Attention-seeking

- Competitive

While they tend to be adaptable and independent, they can also have a rebellious streak that tends to emerge when they want to stand apart from their siblings.

" Middle child syndrome " is a term often used to describe the negative effects of being a middle child. Because middle kids are sometimes overlooked, they may engage in people-pleasing behaviors as adults as a way to garner attention and favor in their lives.

While research is limited, some studies have shown that middle kids are less likely to feel close to their mothers and are more likely to have problems with delinquency.

Some research suggests that middle children may be more sensitive to rejection . As a middle child, you may feel like you didn't get as much attention and were constantly in competition with your siblings. You may struggle with feelings of insecurity, fear of rejection, and poor self-confidence .

Lastborns, often referred to as the "babies" of the family, are often seen as spoiled and pampered compared to their older siblings. Because parents are more experienced at this point (and much busier), they often take a more laissez-faire approach to parenting .

Last-born children are sometimes described as:

- Free-spirited

- Manipulative

- Self-centered

- Risk-taking

Adler's theory suggests that the youngest children tend to be outgoing, sociable, and charming. While they often have more freedom to explore, they also often feel overshadowed by their elder siblings, referred to as " youngest child syndrome ."

Because parents are sometimes less strict and disciplined with last-borns, these kids may have fewer self-regulation skills.

"If the youngest of many children is female, she tends to be more coddled or cared for, leading to a greater reliance on others compared to her older siblings, especially in larger families," Lev suggests.

Only children are unique in that they never have to share their parents' attention and resources with a sibling. It can be very much like being a firstborn in many ways. These kids may be doted on by their caregivers, but never have younger siblings to interact with, which may have an impact on development.

Only children are often described as:

- Perfectionistic

- High-achieving

- Imaginative

- Self-reliant

Because they interact with adults so much, only children often seem very mature for their age. If you're an only child, you may feel more comfortable being alone and enjoy spending time in solitude pursuing you own creative ideas. You may like having control and, because of your parents' high expectations, have strong perfectionist tendencies .

How Birth Order Influences Relationships

Birth order may affect relationships in a wide variety of ways. For example, it may impact how you form connections with other people. It can also affect how you behave within these relationships.

Dr. Lev suggests that the effects of birth order can differ depending on gender.

"For instance, in a family with two female siblings, the younger one often appears more confident and empowered, while the older one is more achievement-focused and insecure," she explains.

She also suggests that there is often a notable rivalry between same-sex siblings versus that of mixed-gender siblings. Again, this effect can vary depending on gender. Where an older sister might be less secure and the younger sister more secure, the opposite is often true when it comes to older and younger brothers.

"This could be because older sisters often assume a motherly role, while older brothers might take on more of a bully role. As a result, younger brothers are generally more insecure, whereas younger sisters tend to be more confident than their older siblings," she explains.

Some other potential effects include:

Communication

Birth order can affect how you communicate with others, which can have a powerful impact on relationship dynamics.

- Firstborns and only children are often seen as more direct, which others can sometimes interpret as bossy or controlling.

- Middle children may be less confrontational and more likely to look for solutions that will accommodate everyone.

- Lastborns, on the other hand, may rely more on their sense of humor and charm to guide their social interactions.

Relationship Roles

Birth order may also influence the roles that you take on in a relationship.

- Firstborns, for example, may be more likely to take on a caregiver role. This can be nurturing and supportive, but it can sometimes make partners feel like they are being "parented."

- Middle children are more likely to be flexible and take a more easygoing approach.

- Lastborns may be more carefree and less rigid.

Expectations

What we expect from relationships can sometimes also be influenced by birth order.

- Firstborns often have high expectations of themselves and others, sometimes leading to criticism when people fall short.

- Middle children are more prone to seek balance in relationships and want to make sure that everyone is treated fairly and contributing equally.

- Lastborns may place the burden of responsibility on their partner's shoulders while they take a more laissez-faire approach.

"Generally, older siblings are more likely to be in the scapegoat role, while the youngest siblings often have a more idealized view of the family," Lev explains.

Other Factors Play a Role

How birth order influences interpersonal relationships can also be influenced by other factors. Some of these include personality differences, parenting styles , the parents' relationship with one another, and even the birth order of the parents themselves.

While birth order theory holds a popular position in culture, much of the available evidence suggests that it likely only has a minimal impact on developmental outcomes. In other words, birth order is only one of many factors that affect how we grow and learn.

While some research suggests that there are some small personality differences between the oldest and youngest siblings, researchers have concluded that there are no significant differences in personality or cognitive abilities based on birth order.

Birth order doesn't exist in a vacuum. Genetics, socioeconomic status, family resources, health factors, parenting styles, and other environmental variables influence child development. Other family factors, such as age spacing between siblings, sibling gender, and the number of kids in a family, can also moderate the effects of birth order.

Adler’s birth order theory suggests that the order in which you are born into your family can have a lasting impact on your behavior, emotions, and relationships with other people. While there is some support indicating that birth order can affect people in small ways, keep in mind that it is just one part of the developmental puzzle.

Family dynamics are complex, which means that your relationships with both your parents and siblings are influenced by factors like genetics, environment, child temperament, and socioeconomic status.

In other words, there may be some truth to the idea that firstborns get more attention (and responsibility), that middleborns get less attention (and more independence), and that lastborns get more freedom (and less discipline). But the specific dynamics in your family might hinge more on things like resources and parenting styles than on whether you arrived first, middle, or last.

Individual aspects of your own personality are shaped by many things, but you may find it helpful to reflect on your own experiences in your family and consider the influence that birth order might have had.

Damian RI, Roberts BW. Settling the debate on birth order and personality . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 2015;112(46):14119-14120. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519064112

Luo R, Song L, Chiu I. A closer look at the birth order effect on early cognitive and school readiness development in diverse contexts . Frontiers in Psychology . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.871837

Salmon CA, Daly M. Birth order and familial sentiment . Evolution and Human Behavior . 1998;19(5):299-312. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00022-1

Cundiff PR. Ordered delinquency: the "effects" of birth order on delinquency . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 2013;39(8):1017-1029. doi:10.1177/0146167213488215

Çabuker ND, Batık HESBÇMV. Does psychological birth order predict identity perceptions of individuals in emerging adulthood? International Online Journal of Educational Sciences. 2020;12(5):164–176.

Damian RI, Roberts BW. The associations of birth order with personality and intelligence in a representative sample of U.S. high school students . Journal of Research in Personality . 2015;58:96-105. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2015.05.005

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Does Birth Order Really Determine Personality? Here’s What the Research Says

O ne Friday afternoon at a party, I’m sitting next to a mother of two. Her baby is only a couple of weeks old. They’d taken a long time, she tells me, to come up with a name for their second child. After all, they’d already used their favorite name: it had gone to their first.

On the scale of a human life, it’s small-fry, but as a metaphor I find it significant. I think of the proverbs we have around second times—second choice, second place, second fiddle, eternal second. I think of Buzz Aldrin, always in the shadow of the one who went before him, out there on the moon. I think of my sister and my son: both second children.

I was the first child in our family. I was also fearful of failure, neurotic, a perfectionist, ambitious—undoubtedly to the point of being unbearable. My sister didn’t study as hard and went out more, worked at every trendy bar in town and spent many an afternoon in front of the TV.

I’d long attributed the differences in our characters to the different positions we held in our family. It seemed to me, all things considered, better to be the firstborn: you had to work harder to expand the boundaries your parents set for you, had a greater sense of responsibility, more persistence, and emerged, in the end, more self-confident.

That theory worked in my favor, but during my second pregnancy, I started to feel sorry for my son. Through no fault of his own, he’d missed out on the enviable position of firstborn. It took that sense of pity for me to realize that I could try to uncover the basis of my ideas about the personality traits of first and second children—and whether there was anything to them.

It was 1874, and Francis Galton , an intellectual all-rounder and a half cousin of Charles Darwin, published English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture . In his book, he profiled 180 prominent scientists, and in the course of his research Galton noticed something peculiar: among his subjects, firstborns were overrepresented.

Galton’s observation was the first in a long line of scientific and pseudoscientific publications on the birth-order effect. The greater chance of success for firstborns, in Galton’s view, was because of their upbringing, an explanation that fitted in with the mores of the Victorian era: eldest sons had a greater chance of having their education paid for by their parents, parents gave their eldest sons more attention as well as responsibility, and in families of limited financial resources, parents might care just a little bit better for their firstborns.

Read more: I Raised Two CEOs and a Doctor. These Are My Secrets to Parenting Successful Children

The distribution system at the foundation of this is called primogeniture: the right of the eldest son (or less frequently, the eldest daughter) as heir. Among Portuguese nobility in the 15th and 16th centuries, for example, second- and later-born sons were sent to the front as soldiers more often than firstborn sons. Second and subsequent daughters were more likely than eldest daughters to end up in the convent. In Venice in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was generally the eldest brother who was permitted to marry, after which younger brothers would live with him and his family, dependent and subservient.

Apart from a few royal families, primogeniture is no longer the norm in Western countries. Somewhere in the course of the last century, most residents of industrialized countries became convinced that love, attention, time and inheritance should be divided equally and fairly among our offspring.

That’s what my partner and I strive to achieve: equal treatment of our two children. But we can’t get around the fact that first, second and subsequent children have slightly different starting points. The question is what consequences that has, exactly – and how insurmountable they are.

At the start of the 20th century, Alfred Adler, Freud’s erstwhile follower, the one who believed that the arrival of a younger sibling meant the dethronement of the firstborn, introduced the birth-order effect into the domain of personality psychology. According to Adler, the eldest identifies most with the adults in his environment and therefore develops both a greater sense of responsibility and more neuroses. The youngest has the greatest chance of being spoiled and is also, often, more creative. All children in the middle—Adler was a middle child—are emotionally more stable and independent: they’re the peacemakers, used to sharing from the start.

After Galton and Adler, the idea that family position affects personality has been subjected to many a scientific test. These tests generated factoids that undoubtedly still fly across the table at Christmas dinners: that firstborn children are overrepresented as Nobel Prize winners, composers of classical music, and, funnily enough, “prominent psychologists.” Subsequent children, on the other hand, were more likely to have supported the Protestant Reformation and the French Revolution.

There are so many assumptions, there’s so much research, and still there are very few hard conclusions to be drawn.

A friend, the eldest of four, presses into my hands a book that her mother claims to have been all the rage during the 1990s. The title is Brothers and Sisters: The Order of Birth in the Family , and it was written in the mid-20th century by the Viennese pediatrician and anthroposophist Karl König.

What strikes me from the very first pages is the certainty with which König characterizes first, second and third children. For example, he quotes a study that found firstborns to be “more likely to be serious, sensitive,” “conscientious,” and “good” and—this is my favorite—“fond of books.” Later on, these firstborns can become “shy, even fearful,” or they become “self-reliant, independent.” A second child, by contrast, is “placid, easy-going, friendly [and] cheerful”—unless they are “stubborn, rebellious, independent (or apparently so)” and “able to take a lot of punishment.” These typologies most resemble horoscopes, in the sense that it can’t be very hard to recognize yourself – or your children – at least partially in any of them.

By now, studies looking into the birth-order effect number in the thousands. There’s no shortage of popular publications either: titles such as Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives and Birth Order Blues: How Parents Can Help Their Children Meet the Challenges of Birth Order have helped spread the idea that your place in the family determines who you are.

In 2003, two U.S. and two Polish psychologists asked hundreds of participants what they knew about birth order. The majority of respondents were convinced that those born earlier had a greater chance of a prestigious career than those born later, and that those different career opportunities had to do with their specific birth-order-related character traits.

In sum, a century after the possible existence of the birth-order effect was first proposed, it had become common knowledge. That knowledge is now so common, in fact, that it lends itself to satire: “Study Shows Eldest Children Are Intolerable Wankers,” a headline on a Dutch satirical news website quipped in 2018.

Read more: I Was Constantly Arguing With My Child. Then I Learned the “TEAM” Method of Calmer Parenting

There is, however, plenty of criticism of birth-order theories and the associated empirical research. It’s not at all straightforward, critics point out, to know what you’re measuring when you try to unravel the factors that shape an individual human life. It’s also very hard to exclude all the “noise,” as physicists in a laboratory would be able to do more easily. This means that traits we might attribute to a person’s birth order may in fact have more to do with, say, socioeconomic status, the size or ethnicity of the family, or the values of a particular culture.

In the early 1990s, a group of political scientists observed with barely concealed exasperation that birth order had been “linked to a truly staggering range of behaviors.” They tried to debunk the myth that even a person’s political preferences were determined by their position in the family by reviewing studies that addressed, among other things, whether firstborns had “an uncommon tendency to enter into political careers,” were more conservative than those born later, and were more likely to hold political office. Their meta-analysis failed to find consistent patterns—but did find myriad methodological flaws.

There are so many assumptions, there’s so much research, and still there are very few hard conclusions to be drawn, although I suppose the latter is often the case, in the social sciences. They tend to provide more nuance rather than painting things in black and white— and rightly so.

Still, I’d like to know if there’s a counterargument to be made, in response to the certainty with which a friend remarks that second children are always “much more chill” than first children. Or to the way a family member takes it for granted that our son, independent and sociable as he is, is a “typical second child.”

Most Popular from TIME

The end of 2015 saw the publication of two studies in which the methodological shortcomings of previous birth-order research (unrepresentative sample sets, incorrect inferences) were largely obviated. In one of these studies, two U.S. psychologists analyzed data about the personality traits and family position of 377,000 secondary-school pupils in the United States. They did find associations between birth order and personality, but besides being so tiny as to be “statistically significant but meaningless,” as one of the researchers formulated it, they also partially ran counter to those predicted by the prevailing theories. For instance, firstborn children in this data set might be a little more cautious, but they were also less neurotic than later-born children.

The other study looked for associations between personality and birth order in data from the United States, Britain and Germany for a total of more than 20,000 people, comparing children from different families as well as siblings from the same family and correcting for factors such as family size and age. Here, the researchers found no relationship between a person’s place in the family and any personality trait whatsoever.

Other recent studies, conducted mostly by economists, do find an association between birth order and IQ: on average, firstborns score slightly higher on IQ-tests – they also tend to get more schooling. This may be due, researchers speculate, to the fact that parents are able to devote more undivided time and attention to their firstborns when they are very small. It’s an effect that has less to do with innate characteristics and more with parental treatment.

For me, it feels as if my children have been given a little extra wiggle room, a more level playing field. Whoever my son is or will become, his personality has not, or in any case not only, been determined by the coincidental fact of his having arrived second. My relief is conditional, of course—science has a tendency to change its mind.

Even so, the authors of one of those 2015 studies cherish little hope of ridding the world of the belief that birth order determines personality. After all, they wrote in an accompanying piece, it takes forever for academic insights to trickle down to the general public. And we tend to be swayed less by scientific results than by our own personal experiences.

My second child is quicker to anger, I once told another mother in a parenting course. But hadn’t my daughter been just as irascible when she was my son’s age?

One of the reasons belief in the birth-order effect is so persistent, they suggest, is because it’s so easily confused with age. Pretty much everyone can see with their own eyes that older children behave differently from younger children. And there’s a good chance that a first child, when compared with a second child, will appear more cautious and anxious. It’s just that this difference probably has more to do with age than with birth order.

My second child is quicker to anger, I once told another mother in a parenting course. But hadn’t my daughter been just as irascible when she was my son’s age? I’d described my son, who was almost 2 years old at the time, as more emotionally stable. Perhaps what I’d meant is that I can easily discern his emotions: they’re still so close to the surface. He sulks when something doesn’t go his way, bows his head and looks askance when he’s doing something he knows he shouldn’t, throws everything within reach on the floor when he’s angry. When he’s excited, he wags—it doesn’t matter that he lacks a tail. His sister’s feelings have already grown more subtle and complex, and the way they’re expressed has become hard to read, for her own 5-year old self as well as for me.

That difference in age might also be the reason that children from the same family are often assigned specific roles, a Dutch developmental psychologist tells me when I present her with the hypothesis of the two U.S. researchers. That way, even if there are no fixed differences in personality , we might still impose differences in behavior . Parents tell the eldest to be responsible, and the youngest to listen to the eldest. The behavior that follows from this is an expression of that role, not of a person’s character.

I think of the way we tried to prepare my daughter for the arrival of her little brother. How we told her that soon there would be someone who couldn’t do anything at all. She’d be able to explain everything to him, we’d said, because she already knew so much. The prospect had appealed to her. Little did we know we were talking her into a stereotype-perpetuating role.

Of course, all the circumstances in which a child comes into the world—whether they’re born male or female, in war or peace, into relative poverty or exorbitant wealth—end up making a person who they are. But the birth-order effect seems to particularly enthuse and preoccupy us.

Perhaps because it’s so concrete: it’s rather more fun and more satisfying to attribute a baby’s generous smile to the fact that he’s a second child than to a vague interplay of personality and environment, expectations and discernment.

And perhaps that’s also what makes it so tempting to attribute the effect to ourselves. It absolves us for a moment of the responsibility for who we are and the duty to turn ourselves into who we want to become: my being neurotic isn’t my fault, it’s just because I’m the eldest.

My son began to dole out little smiles when he was barely 4 weeks old. They were not just twitches or reflexes, I knew for sure, but outright attempts at contact. He began smiling earlier than his sister had, and this made sense to me: he was the second child, and so the more sociable one, just like my own sister.

It didn’t occur to me in that moment that my interpretation of his smile was founded on stories we’d been passing on for generations. It’s only now that I’m beginning to understand that those stories have a history. And that, without us really realizing it, they might shape our children’s present as well as their future.

Excerpted from Second Thoughts: On Having and Being a Second Child by Lynn Berger. Published by Henry Holt and Company, April 20th 2021. Copyright © 2020 by Lynn Berger English translation copyright © 2020 Anna Asbury. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

| on about: / / Adler The importance of the birth order and its impact on the personality of the child and its future. Why is the birth order so important for the personality of the child? What does the “fight for “ power has to do with the birth order in one given family? What do Adler and Toman say about birth order importance? Adler believed that the true reason for such differences between siblings is the “fight for power”: the desire to control the situation, the desire to be different, to be individual, to stand out from the crowd of other children and to get the love of the parents Birth order Essay Table of contents: 1. Introduction 2. Birth order importance 1. First born children and only children 2. Middle born children 3. Last born children 3. Twin children and other positions. 4. Girls and boy in different birth orders. 5. Conclusion "Whatever your family was, you are". Dr. Kevin Leman 1. Introduction Birth order is rather significant in different cultures all over the world. In some cultures the most preferred position – was and still is the position of the eldest child. Some cultures consider the youngest child to be the dominant one. It goes without saying that the birth order has a lot to do with the further social status of the newborn. The reasons of this social status within and outside the family have a lot of premises. Different positions of birth order create certain differences between children belonging to this or that position. These differences altogether explain why siblings are not alike. The term “siblings” is used to identify children that were born from the same parents or in other words children who are brothers and sisters. The widely spread word-combination “sibling rivalry” may be interpreted as a phenomenon caused directly by the birth order. Alfred Adler was the first to speak about the meaning of the birth order for the future life of a child and the differences between the children in accordance with their birth order. According to the research of Alfred Adler, who was also the founder of individual psychology and the second child in his family1, the birth order of a child is the predictor of his future characteristics and peculiarities [Adler, 1998]. Adler believed that the true reason for such differences between siblings is the “fight for power”: the desire to control the situation, the desire to be different, to be individual, to stand out from the crowd of other children and to get the love of the parents 2. Birth order importance As Walter Toman confirms – the patterns of behavior and reactions are very often defined through their birth order and depend on whether the person was the eldest, middle, the youngest or the only child in the family [Toman, 1993]. Each child in his development imitates certain models of behavior. The first-born will imitate grown-ups, as they his significant close persons, who are the only participants of his social interactions. The second child gets an opportunity to choose whom to imitate. This is primarily due to the fact that the eldest children in the family often actively take part in the process of bringing up younger children so can also become a model. These birth order positions do not simply separate brothers and sisters according to their year of birth, but predict the further lifestyles of these siblings. 2.a. First-born children and only children The first child converts the marriage of two people into a real family. Ordinarily, the parents are young and rather inexperienced and sometimes even not ready for the child. Parents try to dedicate all their free time to their child and to apply as many educational techniques as it is possible, nevertheless these techniques often contradict each other and it may result is the constant anxiety of the child. First-borns are very often over-protected, as their parents make the majority of decisions for them. These children are very parent-oriented; they want to meet expectations of their parents and behave as “small adults”. A standard situation of the first-born and only children is when they are in the center of attention of the adults [Stein, 2003]. As a result they are very confident and organized. They are constantly in a need for parental and social approval and do everything possible to avoid “problematic” situations. The eldest child easily takes responsibility. The only child has a problem sharing anything within his social contacts. Some children remain the only ones for their whole life, put some of them at a point turn into the eldest child. This position changes some characteristics, because the birth of another sibling causes trauma for the first-born. The child does not understand why parents do not pay as much attention at him as they used to do before. Being the first to be born he feels he has the right to have all their attention. First-borns are very determined and become true leaders, as they need to prove the adults that they are the best and the “first place” is still after them. The eldest child is more likely to follow the family traditions and it more conservative. If it is a boy, they may inherit their father’s professions. The problem of the eldest child is that originally being the only child in the family he loses all the advantages of this position and as Adler stated - “power”, when the second child is born. So basically, the first-born children go through two major stages: the child is the only one in the family and is in a privileged position, than the second child is born and the first-born competes for being better. As the result first-borns are emotionally unstable. 2.b. Middle born children The middle child in the begging of his life is the second child in the family. For this child there is always somebody ahead of him. The major goal of the second-born is to overtake the first-born. It is obvious that this type of siblings may have problems with self-determination due to the fact that they are at the same time the older and the younger child. The only exception is when the middle child is the only girl or the only boy in the family. In this case they also occupy a “special” position for their parents. Middle children combine the qualities of the eldest and the youngest child in the family. These children often have troubles finding their true place, because adults forget about them, paying special attention to the eldest child (the smart one) and to the youngest child (the helpless one). Middle siblings learn how to live in harmony with everybody, are often friendly, and make friends without difficulties. They do not feel too guilty for their failures as the fist-born children do but cope easily with any loss. Middle children are capable of seeing each aspect of live from two opposite sides, which results from the ability to live between two other birth order positions and are great negotiators. 2.c. Last-born children The last-born child is carefree, optimistic and ready to taken someone’s protection, care and support. Very often he remains a baby for his family. He does not have to meet the high parental expectations, which the eldest child experiences, because the parents become less demanding to the child’s achievements. He has a lot of people to support him: his parents and his elder brothers or sisters. This exceeding support often spoils this sibling. The major problem the youngest child faces is the lack of self-discipline and difficulties in the sphere of decision-making. The last-born child is often manipulative. He may get offended or try to “enchant” in order to get what he needs. Ass these children get plenty of attention they ordinarily do not have troubles in socialization. The last-born child may have enormous ambitions. The youngest child has two alternatives of developing any relations with the surrounding enviroment, and especially with his brothers and sisters. He needs either to pretend to be a “baby” his whole life, or find a way to overtake the other siblings [Sulloway, 1997]. This type of children is usually very hard to understand, as they seem to completely contradict the other children. They are often very creative. It is believed that the parents will have a more consequent approach to the education of their youngest child than to the eldest or the middle child. As a result he becomes emotionally stable. They break rules easily and are often what people call a “rebel”. Last-born siblings usually make other people laugh and need to be in the center of attention. They do not feel uncomfortable when people look at them – that is why the stage is a perfect place for these children. 3.Twin children and other positions. For twins the position of the eldest or youngest child are also very important and depend on the group of children they were born in. For instance, twins who have an elder sister or an older brother will behave as the youngest children. If the adults emphasize that one of the twins was born earlier, than the position of the eldest and the youngest children are divided automatically. Twins usually tend to communicate with each other than with other children and are less adult-oriented. They major problem for twins is the identity problem. Twin children experience difficulties in separating from each other. The situation when there is only one boy in the family changes the meaning of the positions, because the boy gets a “special” position for being not a girl. In a situation when there are two girls and one boy in the family. No matter what position the only boy occupies he will either always use all possible ways to prove that he is a man or become effeminate [Leman, 1998]. If there are only boys in the family, the youngest one, being a rebel, and trying to be different may also be effeminate. In a situation where there is only one girl among boys in a family the girl gets a lot of “protectors”. The typical reaction to these positions is either very feminine girls or tomboys. If a girl becomes a tomboy she needs to be better than her brothers at least in some activities or physical abilities. 4. Girls and boy in different birth orders The attitude of the adults towards the sex of the child is of a great importance. The majority of the families prefer sons. The older sister very often takes responsibility for bringing up younger children and takes a part of parental functions. In such a position if the youngest child is a boy than he is the one to get the “glory” and high parental expectations. There is also a high probability that the families that have only girls will continue their attempts to give birth to a son, while the families with only sons will stop at a fewer amount of children. A very significant factor to mention is that if the age difference between the children, no matter what sex they are, is more than six years, each of the children will have the traits of the only child and some characteristics of the positions he is close to. For instance, the brother that is ten years elder than his little sister will probably remain the only child but will also have the trait of the first-born child. The more the age difference among the siblings is the less is the probability that they will compete. 5. Conclusion Each child in any family want to ensure his individuality, occupy his own place, a place that is designed for him only. Each child needs to emphasize that his is unique and there is nobody else like him. This is the main reason why birth order has such a big importance – it explains why children are the whey they are according to what they have to overcome to prove that they are unique. So if a senior child who is serious and responsible will be set as an example for the younger one, then the younger child at least from the desire to be different will become noisy, restless and naughty. The birth order does psychologically influence the child. The literature on this topic is wide but it all claims the importance of the birth order for the further life of the child. Alfred Adler was definitely right to say that the desire to be unique is the major leading force for children in the family. So parent would be more democratic and let the children be successful in different fields so they do not compete. It goes without saying that these birth order regularities are not fatal, but only point out some trends of development of the children depending on their order of birth. Knowing these tendencies will help adults to avoid a lot of undesirable consequences to which the mentioned above roles of the children in the family may lead. 1 Alfred Adler is the author of the inferiority complex. | | | PAPER WRITTEN BY PROFESSIONALS Argumentative essay? /page | |

Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — Birth Order — The Importance of Children’s Birth Order in a Family

The Importance of Children’s Birth Order in a Family

- Categories: Birth Order

About this sample

Words: 894 |

Published: Dec 12, 2018

Words: 894 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Table of contents

Analyzes of my birth order, importance of birth order, works cited.

- Adler, A. (1927). The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology. Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Adler, A. (1956). The individual psychology of Alfred Adler: A systematic presentation in selections from his writings. H. L. Ansbacher & R. R. Ansbacher (Eds.). Harper & Row.

- Eckstein, D., & Kaufman, G. (2012). Birth order and personality. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences, 287-305.

- Harris, J. R. (1998). The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do. Simon & Schuster.

- Johnson, S. (2000). Birth Order and Its Implications for Personalities. Family Therapy Magazine, 19(2), 29-33.

- Leman, K. (2010). The Birth Order Book: Why You Are the Way You Are. Revell.

- Stewart, A. E., & Stewart, J. H. (1995). Birth Order: What You Need to Know About Your Children and Their Personalities. Tyndale House Publishers.

- Sulloway, F. J. (1996). Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives. Vintage Books.

- Toman, W. (2014). Family Constellation: Its Effects on Personality and Social Behavior. Springer.

- Vooijs, M., Hagestein, G., & Finkenauer, C. (2016). The impact of birth order on sibling relationships in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 37(5), 675-693.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1453 words

3 pages / 1369 words

2 pages / 796 words

2 pages / 720 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Birth Order

The transition to college is a pivotal moment in a young person's life, marked by newfound independence, academic pursuits, and personal growth. For a middle child, this transition can hold particular significance, often [...]

Birth order, the sequence in which children are born within a family, has long been a subject of fascination and study in psychology and sociology. The concept suggests that the order in which a child is born can influence their [...]

Being the middle child in a family holds a unique position that comes with its own set of dynamics and challenges. The experiences and traits associated with being the middle child have long intrigued psychologists, researchers, [...]

This study aims to investigate whether birth order has any influence on level of self-esteem. A Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale questionnaire was given to each potential participant (n=30) who consent to give their information for [...]

Life begins the minute one egg and one sperm unite at conception. Over the past century technological advancements in science have allowed humanity to take a closer look into our younger selves; specifically, the process of our [...]

Children are unable to dispassionately review their list of physical and psychological characteristics. They are able to see themselves as being good or bad. The development of self-esteem in middle childhood is a crucial [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Birth Order and Personality

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Birth Order and Personality. (2016, Aug 09). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay

"Birth Order and Personality." StudyMoose , 9 Aug 2016, https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). Birth Order and Personality . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay [Accessed: 2 Sep. 2024]

"Birth Order and Personality." StudyMoose, Aug 09, 2016. Accessed September 2, 2024. https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay

"Birth Order and Personality," StudyMoose , 09-Aug-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay. [Accessed: 2-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). Birth Order and Personality . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/birth-order-and-personality-essay [Accessed: 2-Sep-2024]

- Business of Birth: Empowerment at Birth Pages: 2 (520 words)

- Parenthood: Psychology and Birth Order Pages: 3 (807 words)

- A Birth Order Overview And The Life Of a Middle Child Pages: 14 (4176 words)

- How The Birth Order Affects The Education Prowess Of a Middle Child Pages: 5 (1370 words)

- Order Qualifiers and Order Winners for Toyota Pages: 2 (353 words)

- Personality development, the concept that personality is affected Pages: 5 (1464 words)

- Objective Personality Tests: Assessing Personality Traits with Scientific Precision Pages: 2 (535 words)

- Population and Birth Rates in Great Britain Pages: 6 (1656 words)

- Birth Defects Lifestyle Choices and Chronic Effects Pages: 5 (1272 words)

- Steven Paul Jobs: The Birth and Early Life of a Tech Visionary Pages: 38 (11155 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Psychology

Essay Samples on Birth Order

Birth order as one of the main influence of the child's personality.

Personality comes from many different things, but a main influencer is from birth order. Children who are first borns and children who are later-borns contrast in how they act majorly because of when they came into this world. It can determine certain aspects of mental...

- Birth Order

- Child Development

- Child Psychology

Literature Review on the Effects of Birth order on a Person’s Personality and Achievements

Character is a one of a kind result of the blend of different attributes and characteristics that have created with assistance of ecological, genetical and social components. The person tends to act, think and feel in a certain way influenced by these factors. Personality of...

- Personality

Effect of Birth Order on Criminality

Introduction Behind every crime large or small question remains the same: why did the criminal do it? To figure out the motivation behind crime, criminal behavior professionals used a variety of resources and techniques to answer this difficult question. They examine the history of crime,...

Association of Various Measures of Empathy and Pro-Social Behaviour with Birth Order

Abstract A survey was conducted to find the effect of birth order and its association with the behaviour of kids. It was carried out among university students to determine if the order of birth had any effect of them being sympathetic to other strangers or...

- Prosocial Behavior

The Influence of Birth Order On Self-Esteem

Abstract This study aims to investigate whether birth order has any influence on level of self-esteem. A Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale questionnaire was given to each potential participant (n=30) who consent to give their information for research purposes with ensured anonymity in which their identity is...

- Self Esteem

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Best topics on Birth Order

1. Birth Order As One Of The Main Influence Of The Child’s Personality

2. Literature Review on the Effects of Birth order on a Person’s Personality and Achievements

3. Effect of Birth Order on Criminality

4. Association of Various Measures of Empathy and Pro-Social Behaviour with Birth Order

5. The Influence of Birth Order On Self-Esteem

- Confirmation Bias

- Self Concept

- Problem Solving

- Human Behavior

- Milgram Experiment

- Psychoanalysis

- Attachment Theory

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

- v.112(46); 2015 Nov 17

Settling the debate on birth order and personality

Rodica ioana damian.

a Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, 77204;

Brent W. Roberts

b Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, 61820

Author contributions: R.I.D. and B.W.R. wrote the paper.

Birth order is one of the most pervasive human experiences, which is universally thought to determine how intelligent, nice, responsible, sociable, emotionally stable, and open to new experiences we are ( 1 ). The debate over the effects of birth order on personality has spawned continuous interest for more than 100 y, both from the general public and from scientists. And yet, despite a consistent stream of research, results remained inconclusive and controversial. In the last year, two definitive papers have emerged to show that birth order has little or no substantive effect on personality. In the first paper, a huge sample was used to test the relation between birth order and personality in a between-family design, and the average effect was equal to a correlation of 0.02 ( 2 ). Now, in PNAS, Rohrer, Egloff, and Schmukle ( 3 ) investigate the link between birth order and personality in three large samples from Great Britain, the United States, and Germany, using both between- and within-family designs. The results show that birth order has null effects on personality across the board, with the exception of intelligence and self-reported intellect, where firstborns have slightly higher scores. When combined, the two studies provide definitive evidence that birth order has little or no substantive relation to personality trait development and a minuscule relation to the development of intelligence.

In the wake of these findings, one may ask why previous findings were inconclusive. To address this question, it is essential to understand the current state of research on birth order and personality, as well as the vital methodological contributions of the Rohrer et al. report ( 3 ).

Why Were Previous Studies of Birth Order Inconclusive?

Over the past two decades, hundreds of studies have produced widely ranging estimates of the effects of birth order on personality traits, falling anywhere between a correlation of 0.40 ( 1 ) and 0 ( 4 ). One possible explanation for these inconsistent findings is the pervasive use of underpowered study designs using nonrepresentative population samples. Regarding the link between birth order and intelligence, the results are much more consistent, possibly because of the large representative samples used ( 5 , 6 ). The Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) study addresses the power issues by using three large representative samples from three different countries. This is notable, because only one previous study ( 2 ) had tested the effect of birth order on

Scientific evidence strongly suggests that birth order has little or no substantive relation to personality trait development and a minuscule relation to the development of intelligence.

personality in a large representative sample (in a between-family context). The Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) study replicates the latter findings, and extends them significantly by investigating cross-national patterns and by being the first study to ever explore within-family effects simultaneously with between-family effects in large representative samples. This study also replicates results on birth order and intelligence that have been previously found in large samples in both between- and within-family designs.

A second reason for the lack of consensus has to do with changing standards on what would be deemed the optimal method for testing birth-order effects on personality. Recently, some have argued that between-family designs were inadequate and that only within-family comparisons were up to the task of testing and revealing the role of birth order on personality. A between-family study design compares the personality traits and intelligence of a cross-section of unrelated people who have different birth ranks. In contrast, a within-family design compares the personality traits and intelligence of first- and laterborn siblings from the same family. Between-family designs have been criticized primarily for not being able to adequately control for between-family differences in sibship size, genetic differences, and specific family practices ( 7 ). Ignoring these sources of variance is likely to produce biased estimates of birth-order effects. For example, sibship size, which represents the total number of siblings present in the family, is an important confound because firstborns (vs. laterborns) are more likely to be “found” in low sibships. Because wealthier more educated parents tend to have fewer children, firstborns tend to be overrepresented among families of a high socioeconomic status, the latter being related to personality and intelligence ( 8 ). Thus, any serious attempt at testing the effects of birth order on personality in a between-family design should statistically control for sibship size, which the study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) does.

The second criticism brought to between-family designs is that they do not reflect the within-family dynamics put forward by the evolutionary niche-finding model, whereby each child is trying to find a niche that has not yet been filled, to receive maximum investment from the parents ( 9 ). The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) also addresses this issue by supplementing their between-family design with a within-family design (using a subsample of siblings from the same datasets).

Although within-family designs of birth order may be considered superior to between-family designs because they can adequately control for some confounding factors and because they reflect the within-family dynamics put forward by the evolutionary model ( 7 ), they also pose some problems. First, within-family designs, as they are currently used, tend to introduce a perfect age confound ( 10 ). Specifically, studies so far have tested all siblings at the same time, which means the firstborn was always older than the laterborns at the time of assessment. Given what we know about personality development and maturation ( 11 ), it is very possible that the firstborn only appears to be more conscientious, for example, because of being older. The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) is the first study to date to ever address this issue when employing a within-family design by using age-adjusted t -scores.

The second criticism brought to within-family studies of birth order and personality is that they may suffer from demand effects or social stereotypes that may inflate the correlations ( 12 ). This problem is enhanced by the fact that the existing within-family research on birth order and personality has been limited by its use of a single rater from each family ( 4 ). Specifically, the single rater compares oneself against one’s siblings, thus increasing the likelihood of perceiving a contrast. The study by Rohrer et al. ( 3 ) addresses this issue by using independent self-reports collected from each sibling. This is only the second study to ever use independent ratings in the within-family context, and the first to do so while using large representative samples.