- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

When You’re This Hated, Everyone’s a Suspect

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

- Bookshop.org

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Meryl Gordon

- Published May 17, 2022 Updated May 18, 2022

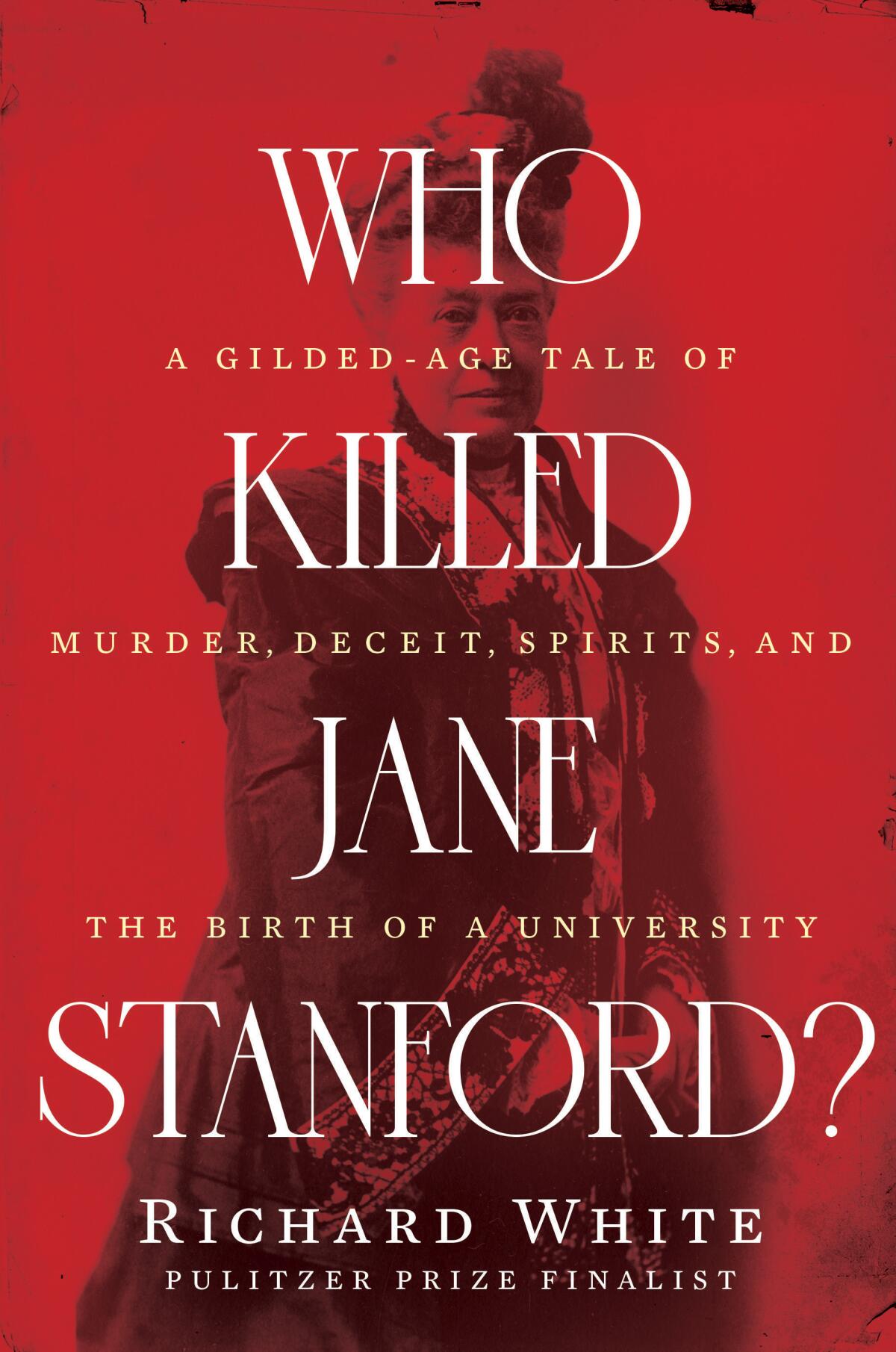

WHO KILLED JANE STANFORD?

A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits, and the Birth of a University

By Richard White

On the evening of Jan. 14, 1905, Mrs. Leland Stanford was at home in her 50-room San Francisco mansion when she took a sip of the bottled water presumably left at her bedside by a member of her staff. She began vomiting and complained that the drink tasted bitter. Although she soon recovered, she requested a chemical analysis and received a shocking report: Strychnine had been found in the Poland Spring bottle. Rather than call the police, she confided in her brother. He contacted the family lawyer, who hired a private investigator.

Fearful that someone was trying to murder her, Jane Stanford, a 76-year-old widow, sailed for Honolulu several weeks later with two trusted employees. At the Moana Hotel, on the night of Feb. 28, she drank bicarbonate mixed with water and became violently ill again. The hotel’s doctor arrived within minutes, but Stanford could not be saved and suffered an agonizing death. The physicians who conducted the autopsy agreed on the cause: strychnine poisoning.

It’s daunting to try to solve a murder that occurred more than a century ago: Witnesses are long gone, and research can take place only in databases and archives. But the circumstances surrounding the death of Jane Stanford, who with her wealthy railroad titan husband, Leland, founded the namesake California university, are so bizarre and tantalizing that it’s no wonder several books have been devoted to the case.

Not least because it remains officially mysterious. Despite investigations in both Honolulu and San Francisco, no one was ever charged with Stanford’s murder. Instead, David Starr Jordan, the president of Stanford, and others staged an elaborate cover-up to cast doubt on the medical evidence and convince both the authorities and the public that her death was due to natural causes. For the beneficiaries of her multimillion-dollar estate — Stanford University, her relatives and two employees — a murder trial was to be avoided at all costs, since it could have resulted in a challenge to her will.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

WHO KILLED JANE STANFORD?

A gilded age tale of murder, deceit, spirits and the birth of a university.

by Richard White ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 17, 2022

An entertaining tale of money, power, and malfeasance.

Historical true-crime tale involving an unsolved murder and the tumultuous early years of a prestigious university.

An award-winning historian and MacArthur and Guggenheim fellow, White became intrigued by the unsolved mystery of the death of Jane Stanford (1828-1905), who, with her husband, railroad magnate Leland Stanford, founded a university to memorialize their dead son. When Jane died suddenly in Honolulu, witness statements and an autopsy indicated poisoning, but by the time her body arrived in San Francisco, the notion of a crime had been quashed. White uses the coverup to create a lively detective story exposing “the politics, power struggles, and scandals of Gilded Age San Francisco,” including those that roiled the Palo Alto campus. Jane was wealthy, impetuous, and domineering. The university, intellectually mediocre and struggling financially, “was for all practical purposes” whatever the Stanford family wanted it to be, and its faculty and administration were harassed by Jane’s “whims, convictions, resentments,” and her ardent belief in spiritualism. She was surrounded by bickering servants, duplicitous lawyers, and rivalrous family members, but university trustee George Crothers, Jane’s confidant and legal adviser, worked assiduously to prevent her from undermining her own interests and the future of the university. He agreed with others that a murder trial “could reveal the controversies within the university, resurrect old scandals, and reveal new ones. All this would embarrass and threaten important people and institutions.” Indeed, White believes that Stanford’s death may have saved the university and certainly the job of its president, David Starr Jordan, whom Jane wanted to fire. “Jordan never mastered Jane Stanford while she lived,” writes the author, “but death made her malleable.” He eulogized her with praise. White identifies many individuals with a motive to poison Jane; advised by his brother, Stephen, a writer of crime fiction, he homes in on one culprit. Although at times White’s impressive findings slow the pace, he fashions an engaging narrative.

Pub Date: May 17, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-324-00433-2

Page Count: 384

Publisher: Norton

Review Posted Online: March 15, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 1, 2022

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HISTORY | TRUE CRIME | HISTORICAL & MILITARY | UNITED STATES

Share your opinion of this book

More by Richard White

BOOK REVIEW

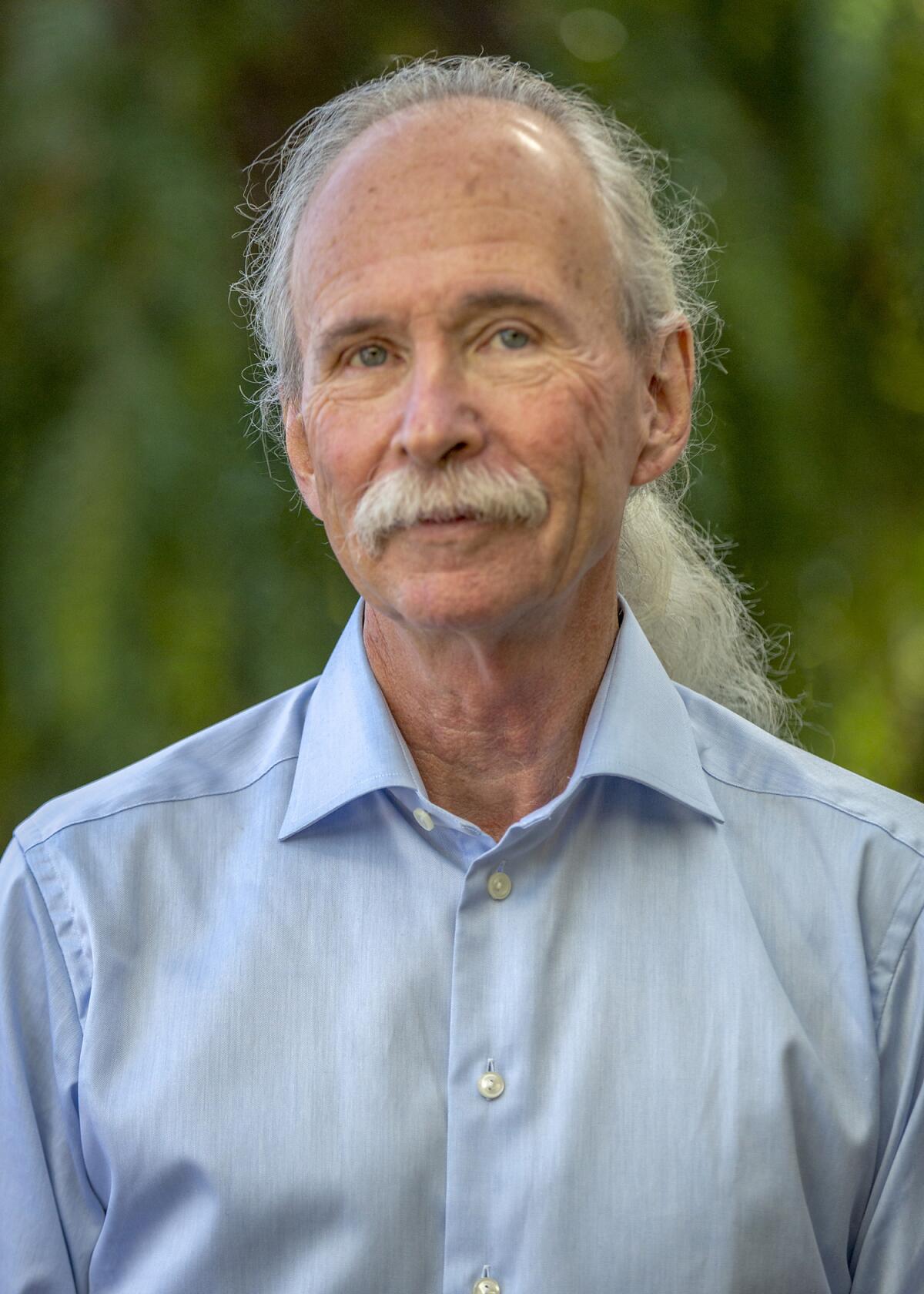

by Richard White ; photographed by Jesse Amble White

by Richard White

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2017

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

National Book Award Finalist

KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

The osage murders and the birth of the fbi.

by David Grann ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 18, 2017

Dogged original research and superb narrative skills come together in this gripping account of pitiless evil.

Greed, depravity, and serial murder in 1920s Oklahoma.

During that time, enrolled members of the Osage Indian nation were among the wealthiest people per capita in the world. The rich oil fields beneath their reservation brought millions of dollars into the tribe annually, distributed to tribal members holding "headrights" that could not be bought or sold but only inherited. This vast wealth attracted the attention of unscrupulous whites who found ways to divert it to themselves by marrying Osage women or by having Osage declared legally incompetent so the whites could fleece them through the administration of their estates. For some, however, these deceptive tactics were not enough, and a plague of violent death—by shooting, poison, orchestrated automobile accident, and bombing—began to decimate the Osage in what they came to call the "Reign of Terror." Corrupt and incompetent law enforcement and judicial systems ensured that the perpetrators were never found or punished until the young J. Edgar Hoover saw cracking these cases as a means of burnishing the reputation of the newly professionalized FBI. Bestselling New Yorker staff writer Grann ( The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: Tales of Murder, Madness, and Obsession , 2010, etc.) follows Special Agent Tom White and his assistants as they track the killers of one extended Osage family through a closed local culture of greed, bigotry, and lies in pursuit of protection for the survivors and justice for the dead. But he doesn't stop there; relying almost entirely on primary and unpublished sources, the author goes on to expose a web of conspiracy and corruption that extended far wider than even the FBI ever suspected. This page-turner surges forward with the pacing of a true-crime thriller, elevated by Grann's crisp and evocative prose and enhanced by dozens of period photographs.

Pub Date: April 18, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-385-53424-6

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: Feb. 1, 2017

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2017

GENERAL HISTORY | TRUE CRIME | UNITED STATES | FIRST/NATIVE NATIONS | HISTORY

More by David Grann

by David Grann

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

IN COLD BLOOD

by Truman Capote ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 7, 1965

"There's got to be something wrong with somebody who'd do a thing like that." This is Perry Edward Smith, talking about himself. "Deal me out, baby...I'm a normal." This is Richard Eugene Hickock, talking about himself. They're as sick a pair as Leopold and Loeb and together they killed a mother, a father, a pretty 17-year-old and her brother, none of whom they'd seen before, in cold blood. A couple of days before they had bought a 100 foot rope to garrote them—enough for ten people if necessary. This small pogrom took place in Holcomb, Kansas, a lonesome town on a flat, limitless landscape: a depot, a store, a cafe, two filling stations, 270 inhabitants. The natives refer to it as "out there." It occurred in 1959 and Capote has spent five years, almost all of the time which has since elapsed, in following up this crime which made no sense, had no motive, left few clues—just a footprint and a remembered conversation. Capote's alternating dossier Shifts from the victims, the Clutter family, to the boy who had loved Nancy Clutter, and her best friend, to the neighbors, and to the recently paroled perpetrators: Perry, with a stunted child's legs and a changeling's face, and Dick, who had one squinting eye but a "smile that works." They had been cellmates at the Kansas State Penitentiary where another prisoner had told them about the Clutters—he'd hired out once on Mr. Clutter's farm and thought that Mr. Clutter was perhaps rich. And this is the lead which finally broke the case after Perry and Dick had drifted down to Mexico, back to the midwest, been seen in Kansas City, and were finally picked up in Las Vegas. The last, even more terrible chapters, deal with their confessions, the law man who wanted to see them hanged, back to back, the trial begun in 1960, the post-ponements of the execution, and finally the walk to "The Corner" and Perry's soft-spoken words—"It would be meaningless to apologize for what I did. Even inappropriate. But I do. I apologize." It's a magnificent job—this American tragedy—with the incomparable Capote touches throughout. There may never have been a perfect crime, but if there ever has been a perfect reconstruction of one, surely this must be it.

Pub Date: Jan. 7, 1965

ISBN: 0375507906

Page Count: 343

Publisher: Random House

Review Posted Online: Oct. 10, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 1965

More by Truman Capote

by Truman Capote

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

‘Who Killed Jane Stanford?’ Solving the cold case of a California founder’s murder

- Copy Link URL Copied!

On the Shelf

'Who Killed Jane Stanford?: A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits and the Birth of a University'

By Richard White Norton: 384 pages, $35 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org , whose fees support independent bookstores.

Jane Stanford was a monstrous mess. The wife of railroad baron Leland Stanford , Jane was rich, duplicitous and convinced that God was whispering in her ear. Of friends and family, she demanded total devotion. Of adversaries, she expected evil opposition — and strategized accordingly.

None of this would have mattered to anyone other than the Stanfords’ relations, business partners, factotums and servants except for the fact that in 1885, Jane and Leland co-founded Stanford University , funding it with Leland’s ill-gotten gains. The gesture was a tribute to their only son, Leland Jr., who died of typhoid fever at age 15. After Leland Sr. died in 1893, Stanford University was Jane’s only love. She ran it like she owned it (which in fact she did). She nearly destroyed it with her whims and schemes until someone had enough and poisoned her — twice. The first round of strychnine, a massive dose of rat poison dissolved in a bottle of Poland Spring water, didn’t work. The second, pure strychnine slipped into a bottle of bicarbonate, did the trick.

Which of Jane Stanford’s many enemies tried to poison her? Which one finally succeeded in 1905, condemning her to a cruel death of excruciating spasms far from home in a Honolulu hotel?

It is this mystery that Stanford University emeritus professor Richard White tries to solve in his superb new book, “ Who Killed Jane Stanford? ” White brings the skills of an expert investigator to the task. He’s an acclaimed historian of the American West, and he knows the Stanfords’ deep history like the back of his hand — the corrupt influence of the railroads, the exploitation of immigrants, the criminals and grifters who ran early San Francisco. He taught courses on Jane’s murder at the university, drawing from the work of previous writers, notably Stanford surgeon Robert Cutler , who wrote a book undermining the university’s position that Jane died a natural death.

White writes with clarity, precision and a bone-dry sense of humor. He was aided by his brother Stephen White , an author of crime fiction, in shaping the narrative, and the book sustains momentum through plots, counterplots and diversions. Crucially, White has a lifetime of experience piecing together whole truths from a tattered and incomplete set of sources; some of the best bits in this story come from White observing himself trying to solve the puzzle. Here he considers one suspect’s memoir: “Memoirs convey the meaning of lives and the events that made them, but not necessarily what actually happened…. Bertha Berner lies in her book, but historians, like detectives, not only expect people to lie, they depend on it.… Lies are as revealing as the truth — they just disclose different things.”

How a scholar unearthed the cyanide love triangle that toppled a California arts colony

Catherine Prendergast’s ‘The Gilded Edge’ retells a tragic early 20th century scandal involving Carmel Bohemians from the female victim’s perspective.

Oct. 19, 2021

One of the biggest liars was Jane Stanford herself. She would savagely undercut a rival, and then, as strategic cover, she’d write an admiring letter praising her enemy to the skies. She ordered her servants around — admittedly what one does with servants, but she demanded total obedience. The servants lied in return as self-defense, about both their personal lives and the grift they had going on the side, raking off a percentage from the purchases of antiques they made on Jane’s behalf as her entourage drifted across the globe. Eventually they lied to investigators as well.

Jane hated socialists and the women students of Stanford with their wanton ways (by fin de siècle standards); meanwhile, she indulged herself as only a stratospherically wealthy person of the Gilded Age could. Jane Stanford is so very bad, she is good: When she finally died, two-thirds of the way through the book, I missed her.

There were many other liars, notably the president of Stanford University, David Starr Jordan . “Jordan epitomized pragmatism run amuck,” White writes, in a major understatement. At first Jordan’s lies were the byproducts of bureaucratic infighting, but eventually — fearful that a murder or suicide judgment would jeopardize Jane Stanford’s bequest to the university — he orchestrated a cover-up of her murder that even by today’s jaded standards was jaw-dropping in its preposterousness.

Finally, there were the police of San Francisco . In league with detectives hired by Jordan and other university higher-ups, they lied strategically and consistently, effectively discounting both attempts to murder Stanford by claiming she died of heart failure despite a Honolulu coroner’s jury verdict that she was poisoned. Just the crooked cops in this story would be fodder for a miniseries. Throw in Jane’s wacky spiritualism and lavish outfits, corporate corruption, academic animosities, warring newspapers and more suspects than you’d find in an Agatha Christie novel, and you have enough material for a full season.

Review: How one writer learned to live with her deplorable ancestors

Maud Newton’s “Ancestor Trouble” is more than a family memoir. It’s a journey through the thickets of Ancestry.com, genetics and white accountability.

March 24, 2022

There is even a fitting apocalyptic coda. Jane Stanford built a stone compound at the university as a memorial to her dead husband and son — a gigantic memorial arch, a church, a museum and a mausoleum where Jane would often pray and activate her divine pipeline to “guardian angels” Leland and Leland Jr. (“[God] takes my daily messages to my loved ones gone from earth life,” she wrote a friend. “He is like an operator at the telegraph taking dispatches from his children on earth to his children in Heaven.”) These monuments to adoration, vanity and delusion were heavily damaged in the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. Many of the police records of the investigation, documents that might have revealed the truth of Stanford’s murder, vanished in the catastrophe.

Who killed her? White thinks he knows, and reveals his choice toward the end, but the journey to his conclusion is so absorbing it almost doesn’t matter. “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” shows that the fealty great wealth demands is an enduring cog in history’s gears. And the fact that Stanford University rose from this swamp of murder and conspiracy to become today’s renowned institution? That is perhaps the strangest plot twist of all.

Review: Why a new historical thriller on the Serengeti is better (sorry) than Agatha Christie

Chris Bohjalian’s latest novel, ‘The Lioness,’ features a 1960s Hollywood star’s honeymoon safari that turns into a thrilling psychological game.

May 9, 2022

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

More to Read

The kidnapped heiress who became an ‘urban guerrilla’ and embraced her captors

Aug. 21, 2024

DNA snags suspected serial killer in brutal 1977 slayings in Ventura County

Aug. 9, 2024

A meticulous, pain-filled history of the senseless slaughter at Kent State

Aug. 5, 2024

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Entertainment & Arts

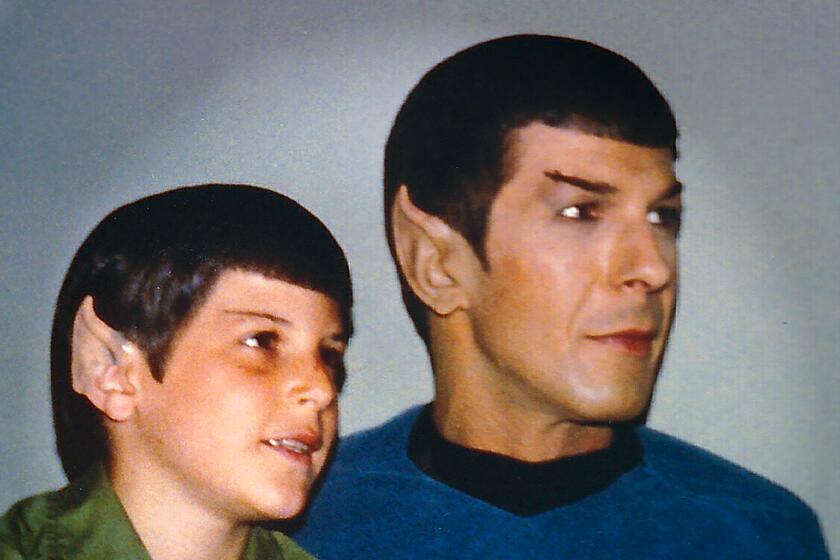

Making peace with Spock: Adam Nimoy on reconciling with his famous father

Aug. 28, 2024

The week’s bestselling books, Sept. 1

Column: A Compton native and academic legend tells his story to a new generation

Aug. 27, 2024

Hell hath no fury like a librarian scorned in the book banning wars

Aug. 22, 2024

A Poisonous Legacy

June 22, 2023 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Who Killed Jane Stanford?: A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits, and the Birth of a University

American Disruptor: The Scandalous Life of Leland Stanford

Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University

Jane Stanford, California, circa 1855

It’s not the crime; it’s the cover-up. Someone murdered Jane Stanford, the cofounder of Stanford University, on Tuesday, February 28, 1905, putting a precisely calibrated dose of pure strychnine in her bicarbonate of soda. The murderer had made an earlier attempt, introducing rat poison into Stanford’s nightstand bottle of Poland Spring water. We can’t be sure who the murderer was, but in Who Killed Jane Stanford? the Stanford University historian turned sleuth Richard White conducts a thorough investigation that includes showing who covered up the murder: David Starr Jordan, the founding president of the university.

Jordan was at least an accessory after the fact. White reaches his own conclusion about who dunnit, but the real interest of his book is his use of the crime and especially the cover-up to lay bare the forces at work in the early days of Stanford. This institution (where I also teach), with its intimate ties to Silicon Valley, its $36 billion endowment, and its outsized prestige—it generally ranks among the top three universities worldwide—has a gothic heritage that might surprise you, as well as some skeletons in the closet that, alas, might not.

American Disruptor: The Scandalous Life of Leland Stanford , a recent book by the journalist Roland De Wolk, offers important background because, although the murder took place after the death of Leland Stanford, Jane’s husband and the other cofounder of the university, his life set the stage for her death. Despite its glorifying title, American Disruptor penetrates the thicket of hagiography surrounding Leland Stanford, the son of a farmer and innkeeper near Albany, revealing him to be a typical American success story: he blundered and swindled his way to wealth, propelling himself upward by the liberal use of other people’s bootstraps.

A reluctant student who never graduated from secondary school, Stanford dropped out of, or was expelled from, a succession of schools, one after only a single night, apparently because he disliked dining at the same table as Black students. By spending two years clerking for a lawyer in the hamlet of Port Washington, Wisconsin, he received a certification to practice law in the state and established a reputation there—not as a good lawyer but as a man who could drink anyone under the table. In 1850 he went home to marry Jane Lathrop, the daughter of an Albany merchant, and she returned with him to Port Washington. But his legal career was a bust. What next?

The Gold Rush was on, and Leland’s four brothers were in Gold Country. The eldest had gone as a forty-niner, but now they were operating Stanford Brothers general store in Sacramento, having discovered a mother lode in the miners themselves: as Mark Twain probably never said, don’t dig for gold; sell shovels. In the summer of 1852 Stanford’s father disposed of his shiftless son by paying for his passage around Cape Horn to join his siblings. (Before the transcontinental railroad, the sea voyage was cheaper than the land route.) Upon arrival in California, Leland was sent by his brothers to represent their interests in remote mining outposts. In one, called Michigan City, he bought a saloon with a gambling operation, began marketing whiskey, and got the local board of supervisors to appoint him justice of the peace. The dropout and failure, by the alchemy of the golden frontier, was now a businessman and politician.

Back in Sacramento in 1856, having fetched Jane from Albany, Leland lucked out again: his brothers went on to other things and left him the store. Stanford Brothers was adjacent to the hardware store of Collis Potter Huntington and Mark Hopkins, while nearby Charles Crocker was selling carpets, clothing, and shoes. These men, too, had arrived from the East Coast with the Gold Rush and discovered bilking miners to be a more comfortable method of gold digging. The four joined forces, with Stanford as their front man. Building a railroad became their bigger and better brand of bilking, and the nascent Republican Party their racket.

Calling themselves “the Associates” and known in the press as “the Big Four,” Crocker, Hopkins, Huntington, and Stanford formed the Central Pacific Rail Road Company of California in 1861, with Stanford as its president. For several years they’d been trying to get him into a statewide office on the Republican ticket; they now succeeded in getting him elected governor on Lincoln’s coattails. This victory helped position the Big Four to build the railroad and their fortune, which they did by misappropriating tax funds and land grants, bribing legislators, manipulating press coverage, establishing monopolistic control by covertly acquiring the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, siphoning money into their own pockets, and hiding their profits from shareholders and creditors, notably the United States government. A quarter-century later, when the California Legislature appointed Stanford to the US Senate, his term was overshadowed by the congressional Pacific Railway Commission’s investigation of the railroad companies’ books and accounts, or rather by its outraged attempt at an investigation, given the mysterious disappearance of all the documents, which turned out to have fueled a prehearing bonfire.

Stanford’s railroad companies employed 10,000 to 12,000 Chinese laborers, whom they exploited even more brutally than they did the smaller number of mostly Irish white immigrant workers. To lay the rails and build stations, they displaced Native Americans from their lands: the federal Pacific Railway Act of 1862 undertook to “extinguish as rapidly as may be the Indian titles to all lands falling under the operation of this act.” The journalist and writer Ambrose Bierce called the Big Four the “rail-rogues” and referred to Leland Stanford as “Stealand Landford.”

During his term as governor, as in his business ventures, Stanford promoted white supremacy, partly by continuing a genocidal war against California’s native population. Even in his opposition to the extension of slavery, in keeping with the Republican Party’s populist platform, Stanford trumpeted “the cause of the white man.” He elaborated:

I am in favor of free white American citizens. I prefer free white citizens to any other class or race. I prefer the white man to the negro as an inhabitant of our country. I believe its greatest good has been derived by having all of the country settled by free white men.

Regarding the influx of Chinese immigrants, White says, Stanford had it both ways: as a politician he called them “a degraded and distinct people” who would “exercise a deleterious influence upon the superior race” and favored checking their immigration; meanwhile, they built his fortune.

Leland Jr. was born in 1868, five years after Leland Sr. finished his term as governor and one year before he drove in the “last spike” establishing the first transcontinental railroad by joining the Central Pacific and Union Pacific rails. A late arrival—his mother was almost forty and his father forty-four—Leland Jr. was a coddled princeling. Accompanying his parents on European tours, he met the pope and the leading French painters and collected art and antiquities to found a museum in San Francisco.

In 1884, at age fifteen, while traveling in Florence, Italy, Leland Jr. died of typhoid fever. His parents’ anguish was limitless; the unappealing Stanfords are at their most sympathetic in their grief for their dead child. The night he died, his parents said, he appeared to his father in a dream, inspiring their resolve to build a university in his name: the childless parents would make the children of California their own. There’s no doubting the authenticity of their emotion. There’s also no doubting that the university served the alchemical purpose of transforming an ill-gotten and tenuously held fortune into a golden posterity, a trick so popular among the robber-baron set that Bierce, in his Devil’s Dictionary , defined “restitution” as “the founding or endowing of universities and public libraries by gift or bequest.”

A gothic atmosphere pervades Stanford University’s early history. The family mausoleum, with its three giant marble sarcophagi and bosomy sphinxes, was Leland Sr.’s first priority. He designated no specific sum in his will for the university overall. For the library, he reckoned something like a gentleman’s private collection would suffice, costing “four or five thousand dollars.” But he allocated $100,000 for the mausoleum. Perhaps this showed foresight, since he came to occupy it soon afterward, in 1893.

The following year, the US Department of Justice sued Leland Stanford’s estate for more than $15 million: the thirty-year loans for the construction of the railroad had come due. The government lost the suit and never got repaid, thanks to a Stanford family ally on the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, Jane Stanford and university president David Starr Jordan had to figure out how to maintain and develop the university in strapped and uncertain circumstances. They generally disagreed. Jane saw the university as a monument to the dead, its most important aspect being a museum containing Leland Jr.’s collection and an exact replica of his bedroom with all its original contents. That building collapsed in the earthquake of 1906, the year after Jane’s death; the university’s current art museum still devotes a couple of rooms to reliquary items like Leland Jr.’s baby shoes, some of his toys, and his death mask. Jane also built the Memorial Arch, which like the museum was destroyed in 1906, and the Memorial Church, which was severely damaged and later rebuilt. The arch’s frieze, entitled The Progress of Civilization in America , showed Leland Sr. and Jane crossing the mountains on horseback, indicating the path of the railroad to an obliging locomotive.

Jordan thought faculty salaries more important than gigantic monuments and referred to this period of construction as the “Stone Age.” Adding to the gothic ambience, Stanford arranged séances to converse with her dead son and husband and had the Memorial Church inscribed with a babel of esoteric inscriptions. Leland Sr. had been a Mason, Jane was drawn to spiritualism, and she filled the Memorial Church with symbols of both, including the Masonic God’s eye in the dome and a blizzard of angels transporting Leland Jr. up to heaven.

Spiritualism, or communication with the dead, was popular at the time in America and throughout the British Commonwealth. Queen Victoria, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and President Ulysses S. Grant were spiritualists; William James chaired the Society for Psychical Research’s American division. James appealed to Jordan’s and Jane Stanford’s disparate tastes: while Jordan admired James’s pragmatic philosophy, Stanford liked his dedication to psychic science. They invited him to visit the university, where he ultimately spent a macabre season, arriving ten months after Stanford’s murder and remaining until the great earthquake of April 18, 1906, released him.

Stanford Family Collections

Leland Stanford Jr. riding his pony, Gypsy, Palo Alto, California, 1879; photographs by Eadweard Muybridge

One of Leland Sr.’s brothers, Thomas Welton Stanford, had also become deeply involved in spiritualism, after his wife’s death. Jane visited T.W. Stanford in Australia, where he had emigrated and made a fortune selling Singer sewing machines. He arranged several séances for his sister-in-law during her visit. The two agreed that occult sciences were essential to higher education, and he endowed a fellowship at Stanford University in psychic research. (I was disappointed to learn that T.W.’s endowment is now just part of the psychology department’s general funds, but the university still holds his collection of “apports,” or objects delivered to him by spirits.) Jane also proposed to subordinate the academic departments to the church, for which she would hire a spiritualist minister.

These developments constituted an ever-worsening headache for Jordan, who was laboring to give the university a different profile. Jordan rejected spiritualism and considered mediums frauds. He began publishing articles in popular science magazines ridiculing the claims of spiritualists and psychics.

Jordan, like the Stanfords, came from upstate New York; he was a member of Cornell’s third graduating class in 1872. He then joined the summer school for zoology teachers run by the Harvard creationist naturalist Louis Agassiz on Penikese Island in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, a few months before Agassiz’s fatal stroke. That summer was transformative for young Jordan, who idolized Agassiz and resolved to become an ichthyologist like him. Although Jordan ultimately became an evangelist of evolutionism (with his own eugenic flavor), he never shed his devotion to the staunchly anti-Darwinian Agassiz, who Jordan said showed students “the necessity of going directly to nature, the fountain head—thus teaching us to recognize the truth as truth.”

Here are some of the things Agassiz recognized as “truth”: that a divine creator had made each species by direct action, that this same creator had made the human races separately from one another, that only white people descended from Adam and Eve, and that one could see the distinct origins of the human races by contemplating “the submissive, obsequious, imitative negro” and “the tricky, cunning, and cowardly Mongolian.”

Having learned Agassiz’s methods for consulting nature, Jordan got a job transmitting them to high school students in Indianapolis, meanwhile picking up a kind of a medical degree at a short-lived school called Indiana Medical College. He then taught zoology at Indiana University, where he later served as president before Leland and Jane Stanford recruited him in 1891. While Leland personifies the American success story, Jordan typifies a certain heroic image of science that became powerful in tandem with that story. This new science defined itself by its separateness from all other modes of understanding—by its reductionism, instrumentalism, utilitarianism, and pragmatism. It had no time for Greek or Latin, literature or history, speculations or interpretations, or any idea without immediate industrial and economic application. It had little time for books: “Study nature not books” was one of Jordan’s mottoes.

Leland’s populist anti-intellectualism suited Jordan. He liked Leland’s notion that a university should train students for “usefulness in life” and his emphasis on science, placing the humanities in a subservient role, including them merely to show the university’s readiness to compete with the old schools on the East Coast. The Stanford University presidency was also attractive to Jordan because it promised an unusual degree of power: since it was a private institution, he wouldn’t have to worry about a state board of regents, and he wouldn’t even answer to the board of trustees, which was to be “without function during the lifetime of either founder.” He would also have the power to hire and fire faculty.

Jordan’s mode of science and Leland’s mode of business were twin expressions of an aspiring industrial class that envisioned itself elbowing aside a senescent elite mumbling in Greek and Latin. Also like Leland’s business model, Jordan’s science model was gilding over dirty tricks: a veneer of objectivity covered a sinister interior in which science not only reaffirmed every social prejudice but armed it with fearsome new powers.

Progress was Jordan’s guiding theme, whether he was writing about fishes, higher education, moral cleanliness, or racial purity. Take fishes. In some conditions they would progress, but not in others, Jordan explained. Rivers, where fish lived in comparative isolation and had less competition, were “ages behind the seas, so far as progress is concerned.” The best conditions for piscine progress were to be found in the tropics, which served “to intensify fish life, to keep it up to its highest effectiveness,” such that a tropical fish must rid itself “of every character or structure it cannot ‘use in its business.’” As the pathetic, backward river fishes and brilliantly successful tropical business-fishes demonstrated, Jordan explained in his lectures and writings on evolution, natural selection made progress possible but not inevitable. Competition, given the right selective pressures, would bring progress, but a lack of competition or the wrong selective pressures would bring regression and degeneracy.

War was among Jordan’s leading examples of a situation that would lead to regression. He promoted pacifism during the period before World War I, arguing that war impedes progress by producing the survival of the unfit, since the strong young heroes die, leaving the weaklings to procreate. Jordan developed this argument in The Blood of the Nation: A Study of the Decay of Races Through the Survival of the Unfit (1907). The book went through many editions, including an expanded one under the even more sinister title The Human Harvest . Here Jordan lays out his two reciprocal guiding principles: “the blood of a nation determines its history” and “the history of a nation determines its blood.” Of course, he explains, “blood” is figurative, since heredity is carried not in the blood but in the “germ-plasm” (then the current view). “Blood” simply means “race unity.” Jordan’s prose acquires a lilt as he offers examples: “A Jew is a Jew in all ages and climes…. A Greek is a Greek; a Chinaman remains a Chinaman.”

Jordan’s commitment to progress also informed his advocacy of coeducation, though you couldn’t really mistake him for a feminist. A woman must be educated, he argued, in order to produce that pinnacle of social evolution, the “civilized home.” Furthermore, associating with cultivated young women in college would inspire in young men, as Jordan expressed it, “the highest manhood.” Jordan’s eugenic logic didn’t always lead him to creditable ideas such as pacificism or coeducation. He chaired the Committee on Eugenics of the American Breeders Association and cofounded the Human Betterment Foundation, which later provided information and propaganda to Nazi officials. In these capacities, he vigorously advocated forced sterilizations, and his efforts were very successful: over the course of the twentieth century, about 20,000 people in state-run hospitals and other institutions were the victims of forced sterilization in California, and about 60,000 people nationally. (In 2021 California became the third state to begin a reparations program for survivors of state-sponsored sterilization.)

Eugenics programs such as these were the sort of progress through science to which Jordan wanted to dedicate Stanford University. But Jane Stanford kept getting in the way with her psychic sciences and gothic construction projects. In 1900 a crisis occurred that created a rift between Jordan and Stanford and between the sciences and the humanities, and that ultimately assumed formative importance for universities throughout America. Edward Ross, an economics professor and one of the highest-profile members of the Stanford University faculty, angered Stanford in various ways. He criticized Leland in class, telling his students that “a railroad deal is a railroad steal” and that “all great fortunes [are] based on theft.” He lectured against the gold standard and turned the lectures into a widely disseminated pamphlet; Jane Stanford, along with the Republican Party, supported the gold standard. He gave a speech to a group of socialists; she hated socialists. He spoke at the Unitarian Church of Oakland, denouncing private streetcars, which were in Stanford’s stock portfolio, and addressed the United Labor Organizations of San Francisco, attacking “coolie labor,” which had built Leland’s railroad.

Stanford asked Jordan to fire Ross, who like Jordan believed in progress through evolutionary science and in using eugenics to prevent “race degeneration.” Jordan didn’t want to; Harvard president Charles Eliot assured him that doing so would be “a great calamity” for the university’s reputation. But ultimately Jordan had no choice; Stanford forced Jordan to force Ross to resign, saying he had threatened the university’s reputation for “serious conservatism.” The firing set off a landslide. George Howard, a history professor, denounced Ross’s ousting with dramatic flair during a class on the French Revolution and soon afterward resigned, beginning an exodus that Horace Davis, later president of the board of trustees, referred to as the “great secession of 1900–01.” The scandal provoked a nationwide discussion of academic freedom that inspired the creation of the American Association of University Professors in 1915, which in turn established the current system of academic tenure.

Stanford began seriously entertaining the idea of getting rid of Jordan himself, while Jordan started confiding to students how much better things would be once Stanford died. He also began working to fire faculty members he thought disloyal to him. The battle lines formed along disciplinary lines, with the humanities on the anti-Jordan side. The head of the Latin department, Ernest Pease, refused to sign a letter condemning Ross; Jordan fired him. Then Julius Goebel, the head of the German department, complained to Stanford about the disproportionate power and money of the university’s science departments and the weakness of the humanities departments. He explained to her how things worked in German universities, where the Geisteswissenschaften retained their prestige alongside the rising Naturwissenschaften . Goebel proposed a set of reforms to curtail the sciences and strengthen the humanities; in the summer of 1904 Stanford drafted a memorandum supporting them. Jordan began maneuvering to block the reforms. A few months later Stanford was dead, and Jordan fired Goebel.

Which brings us back to Jane Stanford’s murder. On January 14, 1905, someone put rat poison in her bedside bottle of Poland Spring water. When she took a sip before going to sleep, it tasted bitter, and she called for help. Her maid, Elizabeth Richmond, and secretary, Bertha Berner, came running and helped her vomit up the poison. When the maid brought the bottle to be analyzed, it turned out to contain strychnine.

Six weeks later, on February 28, Stanford was at the Moana Hotel in Honolulu during a stopover on her way to Japan when it happened again: she took a dose of bicarbonate of soda at bedtime and soon began to feel very sick. She called for help, and Berner, who was traveling with her, came rushing to her aid, as did her new maid, May Hunt, and a hotel guest staying across the hall. Francis Humphris, a doctor who lived in the hotel, tried to induce vomiting and called another doctor to bring a stomach pump and a third to assist. Stanford was suffering convulsions, exclaiming that she was terribly sick, that her jaws were stiff, that she had been poisoned and was dying. She cried out, “Oh God, forgive me my sins,” then “Is my soul prepared to meet my dear ones?” and finally “This a horrible death to die.” She died in the classic posture of strychnine poisoning victims: knees widely separated, soles of the feet turned inward, insteps arched, toes pointed, eyeballs protruded, pupils dilated, jaws fixed, fingers contracted, thumbs digging into the palms of her hands.

Witnessing this and knowing of the previous episode of attempted poisoning, the three doctors had no doubt of the cause of death, but they were thorough. They examined the body and kept the bicarbonate of soda, the glass and spoon used to mix it, and some vomit. The next morning they participated in the autopsy, and eight days later, on March 9, the coroner’s jury inquest returned a straightforward verdict: “Death by poison conclusive.”

The next day, Jordan arrived in Honolulu and set about overturning the verdict. He hired his own medical expert, Dr. Ernest C. Waterhouse, who asserted that Stanford had not been poisoned. Rather, she had overeaten at lunch, which had caused gas, which had provoked hysteria, which had brought about a fatal heart attack. Jordan insinuated that the doctors and authorities in Honolulu had fabricated the evidence of poisoning. He smeared Dr. Humphris as incompetent and dishonest, saying the doctor had put the strychnine into the bicarbonate of soda after the fact.

Jordan bolstered his case in Honolulu and San Francisco by promising favors and bribing corrupt investigators, so that Humphris’s astonished protests fell on deaf ears. Jordan’s version of events became the official one and remained so for the next century. * Waterhouse’s reputation was shot, since people in the medical world knew the truth, but no matter: he immediately left Hawaii, and the practice of medicine, for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he planned to cultivate rubber trees. Jordan, who invested in rubber plantations, no doubt promised help as well as payment for Waterhouse’s services. But the rubber venture didn’t work: Waterhouse died decades later as a transient in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. As for who killed Jane Stanford, you’ll have to read the book to find out White’s conclusion, but as you can see, clearly someone did.

What about those skeletons in the closet? To acknowledge that Stanford had been poisoned would have exposed the corruption and illegitimacy of the university’s funding, the whimsical autocracy of its governance, and the incompetence of its founders. Corruption, autocracy, and incompetence skulk here alongside white supremacy in its various guises, from exploitation to genocidal elimination. But there’s also a malignant force less familiar as such, one that doesn’t skulk but declares itself proudly: “science” in Jordan’s mode, the kind that claims to cast off history, culture, and politics in order to go “directly to nature” and speak in nature’s name. The story of Stanford University’s early years reveals the evil in this mode of science and its intimate affiliation with those other evils.

William James encountered this last iniquity—the scientific university in the mode of Leland Stanford and David Starr Jordan—when he arrived for his visit in January 1906 to teach a course in the history of philosophy. “If I can only get through these next 4 months and pocket the $5,000,” he wrote to a friend, “I shall be the happiest man alive.” He had 300 students and 150 guests, and in his own estimation he lectured excellently, but his efforts were wasted: his students didn’t understand basic concepts such as “hypothesis” or “analogy.” He could hardly “aim too low.” While he appreciated the California landscape, James warned that the university’s governing powers had failed to make a sufficient priority of intellectual teaching and scholarship. It was a relief when, on April 18, the earthquake sent him back east early.

The next year James gave an address to the Association of American Alumnae at Radcliffe about the social importance of a college education, arguing that the humanities were its very crux. The humanities, he observed, were nothing less than the “sifting of human creations” and should encompass all teaching on a college campus, including the social and natural sciences: “Any subject will prove humanistic” if only it were taught “historically”—as an integral element of an ever-developing culture and society. To disconnect the sciences from the world of human pursuits and relations, James warned, was to remove all meaning and integrity from the subjects, reducing them to “a sheet of formulas and weights and measures.”

Hope lies in the incongruities of history. Because people like Leland Stanford and David Starr Jordan don’t have the transcendent powers to which they lay claim, things can develop in unpredictable ways. Stanford University, for instance, became the scene of the pivotal case in the foundation of academic freedom and eventually offered the humanistic teaching of all subjects, including the sciences.

Let me then tell you a story to end this poisonous tale with a small taste of antidote. It begins, to be sure, in darkness, in the winter of 2020. Donald Trump has just expanded his travel ban to include people from several more of what he has called “shithole countries.” Given the number of international students and faculty at Stanford, each such Trumpian act causes particular consternation and chaos, and we’re scrambling to see what we can do for our Ph.D. students from the affected countries. But a ray of light in the form of an undergraduate student has entered my office. He’s a history major concentrating in the history of science, writing his honors thesis on the history of eugenics in California. His name is Ben Maldonado (now he’s a Ph.D. student in the history of science at Harvard) and he’s done a prodigious amount of research, partly for his thesis, partly for a column in The Stanford Daily , and partly for a movement he’s founded with other students—the Stanford Eugenics History Project—with the goal of demanding that the psychology building, Jordan Hall, as it is known at this time, be renamed.

Neither Ben nor I would have fallen into Leland Stanford’s or David Starr Jordan’s top category of humans, but to be fair, neither of them falls into ours. “I don’t understand why people don’t want to talk about the history of eugenics at Stanford,” he says to me. “It’s not our fault; we weren’t here then! But now, Stanford is us, so we have to do what we can to make it right.” His logic is unexceptionable, and his means of making things right is historical scholarship. History didn’t fall into Stanford’s or Jordan’s top category of endeavors, but to be fair, their pursuits don’t fall into ours.

The following autumn, the Stanford Eugenics History Project won its cause. The building formerly known as Jordan Hall is now nameless, awaiting a new name. A month later, Trump failed to retain the presidency, and a few months after that, our students from his “shithole countries” got visas and arrived on campus.

Two years later, a visitor to campus stops me as I’m walking to my office. He’s on his way to a colloquium in the psychology department. He too would have fallen into one of Jordan’s categories of inferior humans. In accented English, glancing worriedly at the map on his phone, he asks if I can direct him to Jordan Hall. “Well now,” I tell him, “yes and no! There’s an interesting story there, do you have a minute?” And although he’s probably already late for his meeting, he pauses to listen, with a dawning smile.

June 22, 2023

Fireball Over Siberia

Who Are the Taliban Now?

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Jessica Riskin

In his late writings and correspondence, Charles Darwin was thinking about how mortal beings strive to make what they can of themselves.

March 21, 2024 issue

September 21, 2023 issue

June 25, 2023

Name Dropping

September 21, 2023

Jessica Riskin is the Frances and Charles Field Professor of History at Stanford. She is currently writing a book about the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the history of evolutionary theory. (March 2024)

Incredible though it may seem, this was the official version of events until 2003, when the first revisionist histories appeared. One was by the late Stanford English professor W. Bliss Carnochan, who reexamined Jane Stanford’s death in “The Case of Julius Goebel, Stanford, 1905,” The American Scholar , Vol. 72, No. 3 (Summer 2003). The other was by the late Robert Cutler, a professor of neurology at the Stanford Medical School, who investigated the case and published The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford University Press, 2003). Both Carnochan and Cutler drew the obvious conclusion: that she was poisoned and that Jordan covered it up. White, in his examination of the politics of the cover-up, affirms these earlier, revisionist views of the case. ↩

The Opening Editorial

November 7, 2013 issue

Short Review

July 14, 1977 issue

Mixed Feelings

April 3, 1975 issue

November 25, 1976 issue

New Editions

February 1, 1963 issue

Brief Encounter

December 12, 1963 issue

The She-Pharaoh

July 15, 1999 issue

Short Reviews

October 16, 1975 issue

Save $168 on an inspired pairing!

Get both The New York Review and The Paris Review at one low price.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Type search request and press enter

Book Review: Murder, He Wrote

New and notable.

Reading time min

Background image: Giorgia Virgili

By Susan Wolfe

N early two decades ago, in 2003, professor of neurology and neurological sciences Robert W.P. Cutler published The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford . The book revealed that the forensic evidence pointed not to heart failure, as the official report indicated, but to murder.

The story piqued my curiosity: Who would want to do away with the woman Stanford’s founding myth heralds as the savior of the university established in her son’s memory—and why?

I devoured Cutler’s book and read theories by other Stanford faculty. My interest led me to write about it. That article—titled “ Who Killed Jane Stanford? ”—ran in the September/October 2003 issue of Stanford.

And alumni readers had a lot to say.

“Having family ties that go back to the late 1940s, I thought I was pretty well informed on Stanford lore,” wrote Scott O’Connor, ’79. The Stanford article “sure killed that notion. What an extraordinary story, with eerie undertones.”

Al Floda, MBA ’80, wrote: “I am sitting here shocked, saddened, and horrified at the story of Jane Stanford’s murder. I knew she had died in Hawaii, but I had never heard this take on it. It’s like learning something terribly tragic about the fate of a beloved family member, indeed the ‘mother’ of the Stanford University family.”

In his recent book, Who Killed Jane Stanford? A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits, and the Birth of a University , history professor Richard White delves into the lesser known facts of the founding: The legal scaffolding supporting the nascent university was precarious at best; the vaunted matriarch, beneficent and beloved, sometimes brandished her money as a bludgeon, propelled by the spirit voices of her deceased loved ones.

“Jane Stanford, a woman supposedly without enemies, cultivated enmity and harvested a bountiful crop,” White writes.

It turns out there were many who had cause to wish her dead.

‘Her first words were predictable. Her last words were surprising. Jane Stanford rarely if ever used the word death . Confronted with death, she spoke its name.’ Stanford history professor Richard White, in Who Killed Jane Stanford? A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits, and the Birth of a University , W.W. Norton

On January 14, 1905, Stanford retired to bed in her San Francisco mansion. On her bed stand, at her request, was a bottle of Poland Spring water. An unusual bitter taste caused her to call out for her personal secretary and her maid, and to force herself to vomit. A chemist’s analysis verified that the water had been spiked with rat poison.

Distraught and traumatized, Stanford decided to travel to Japan, opting for a stopover respite in Honolulu. Shortly before her trip, she divulged to trustee George Crothers that she had lost confidence in then-president David Starr Jordan. Hostility between the two had been growing for years as Stanford meddled in the running of the university, pressing positions that Jordan had refused to execute. She told Crothers she planned to dismiss Jordan upon her return.

She and her travel party set sail for Hawaii on February 15. Two weeks later, on February 28, again at bedtime, she asked her secretary to prepare a bicarbonate of soda to aid her digestion.

Jane Stanford did not live to see the next morning.

A coroner’s autopsy, corroborated by well-regarded physicians, concluded that Jane Stanford came to her painful death by strychnine poisoning. And that might have been that, if not for Jordan.

Upon learning that the university’s benefactor had died, Jordan rushed to Honolulu, ostensibly to escort her body home. Once there, he retained a local doctor to contest the cause of death. One day before her funeral procession in Honolulu, Jordan issued a statement. Referencing the report he’d bought and paid for—but never made public—Jordan proclaimed that Stanford had not been poisoned at all. She had, he said, died of heart failure.

They say the victors write the record books. And so it was that Jordan’s account of her death was the one that went down in history.

While White is not the first to examine the murder of Jane Stanford, his research is the most thorough. An undergraduate course that White taught on research methods, using Stanford’s death as a case study, uncovered a trove of documents. His students’ findings inspired him to pursue the matter further. In his effort, he found missing links, inconsistencies, and questions.

“Preservation of historical records is always imperfect,” White writes, “but rarely have I encountered more documents that have vanished and more collections and reports that have gone missing than in this research.”

Who Killed Jane Stanford? reads like a suspenseful whodunit punctuated by clever, first-person asides from White. In true crime-fiction fashion (guided by his brother, Stephen White, who writes in that genre), he walks the reader through a long list of potential perpetrators, including Stanford’s personal secretary and companion, Bertha Berner; aggrieved faculty and household staff members; and Jordan himself, assessing who had motive, the means, and the opportunity to take Stanford’s life.

Yet White gives us more than a mere mystery: He also explores possible institutional motives for the whitewashing of Jane’s murder.

White portrays Jane and Leland Stanford as having lucked into partnership with the railroad barons who generated the couple’s fortune. The Stanfords’ relative lack of sophistication evidenced itself when it came to drawing up the instruments that would establish and fund the university. In reviewing them, Crothers “discovered that he had barely sampled the rich stew of stupidity, ignorance, and arrogance in the university’s founding documents,” White writes.

A murder investigation would have hampered, if not halted, the distribution of Jane Stanford’s estate, which, at her wishes, went to the university and to many on her household staff—including key suspects. The faulty founding documents would have been scrutinized. Such outcomes would have imperiled the institution, affected the financial futures of the heirs, and mired the young university in scandal.

In a single stroke, Jordan’s phony cause-of-death report brushed all those eventualities away. With no poisoning and no murder, there was no challenge to Stanford’s will, no examination of the university’s legal status, and no threat to Jordan’s position as president.

In 1905, Stanford was “a sleepy, mediocre university,” White writes. Had the death of Jane Stanford been exposed as murder at the time, today’s world-renowned institution might’ve been only a footnote in the history books.

Susan Wolfe , ’81, is a writer in Palo Alto. Email her at [email protected] .

Trending Stories

Law/Public Policy/Politics

Advice & Insights

- Shower or Bath?: Essential Answer

You May Also Like

Why jane stanford limited women’s enrollment to 500.

And what happened next.

Mind Over Major

The case for using college to become more interesting.

Biblio File: What to Read Now — September 2022

New releases that inspire us.

Stanford Alumni Association

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Class Notes

Collections

- Recent Grads

- Mental Health

- After the Farm

- The Stanfords

Get in touch

- Letters to the Editor

- Submit an Obituary

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Code of Conduct

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Non-Discrimination

© Stanford University. Stanford, California 94305.

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

August 30, 2024

- The “digressive purgatory” of grief writing

- Sarah Larson profiles cartoonist Ruben Bolling

- The beginning of the end of alt-lit

Who Killed Jane Stanford? by Richard White

Brendan’s alternate tagline for who killed jane stanford:.

Stanford was ridiculous when it was founded!

Quick synopsis:

The murder of Jane Stanford, one of the founders of Stanford University.

Fun Fact Non-History People Will Like:

Stanford was founded due to the death of the Stanfords’ only child.

Fun Fact for History Nerds:

A line written by the author after explaining multiple ridiculous business decisions by Jane Stanford: “Universities were not supposed to run like this.” I am still laughing.

My Take on Who Killed Jane Stanford:

When is a murder not a murder? When an entire university is at stake, apparently.

In this highly readable true crime book by Richard White, we are introduced to the absolute insanity that is the founding and early years of Stanford University. Leland and Jane Stanford found the university in honor of their young son who passed too soon. After the death of Leland, Jane begins a tyranny over the university with increasing capriciousness that ultimately leads to her murder. White dives deep into the surviving documentation to try and understand how what was very clearly a murder was ultimately deemed natural causes by some authorities.

How can I be so sure Jane Stanford’s poisoning was murder? Because the murderer tried to poison her a month before but failed. You can only believe in so many coincidences.

White writes a wonderful book which is easy to read and will appeal to anyone who loves true crime or even just the absurdity of early Stanford politics.

A great true crime book which will continually surprise you. Read it! Buy it here!

If You Liked This Try:

- Simon Baatz, The Girl in the Velvet Swing

- J. Dennis Robinson, Mystery on the Isle of Shoals

- Hallie Rubenhold, The Five

- Miriam Davis, The Axeman of New Orleans

Brendan Dowd

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Who Killed Jane Stanford?: A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit,... › Customer reviews

Customer reviews.

Who Killed Jane Stanford?: A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits and the Birth of a University

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Top positive review

Top critical review

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later.

From the united states, there was a problem loading comments right now. please try again later..

- ← Previous page

- Next page →

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Weird But True

- Sex & Relationships

- Viral Trends

- Human Interest

- Fashion & Beauty

- Food & Drink

trending now in Lifestyle

Husband suffers bizarre penis infection after dinner and...

Dear Abby: I'm my husband's boss — he won't stop showing up...

Do you know what the 'o' in 'o'clock' stands for? If not, the...

This sleep routine can cut your heart disease risk by 20%: new...

Worse hangovers in your 40s? The answer might surprise you

'Surgery addict' who spent $1M to look like Kim K says butt lift...

Most of the world isn't getting enough of these nutrients:...

The one thing every woman has in her Notes app that would...

‘who killed jane stanford’ new book reveals university founder’s killer.

Jane Stanford’s death was one of the most sensational of the 20th century — and now, more than 100 years later, a new book offers enough proof to call it murder.

Stanford, beloved by her community, survived the deaths of her husband and son while keeping her family’s namesake university afloat with her own money. She seemed like the unlikeliest of murder victims when she died in Hawaii, spasming and vomiting, poisoned by strychnine.

Who would want to kill a generous old lady?

Plenty of people, according to a new book by veteran historian Richard White. There are so many possible suspects in “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” (W.W. Norton) that the book reads like a game of “Clue” — among them, a disgruntled university president, an overworked personal assistant, a recently fired “manservant” and a handful of aggrieved housekeepers.

So, who killed the rich old lady in the Honolulu hotel room with the rat poison?

White scoured the archives in search of answers. “Rarely have I encountered more documents that have vanished and more collections and reports that have gone missing than in this research,” writes White.

Luckily for readers, White has solved the mystery and the record can finally be set straight on this century-old cold case.

(Be warned: Spoilers abound.)

Jane’s husband Leland Stanford made his money in railroads — and according to White, this wasn’t a clean way of building capital. It took a fair share of “lying, cheating, self-dealing and backstabbing.”

The idea for a university came after the death of his son, who died of typhoid before his 16th birthday. According to lore, Leland Stanford Jr. asked his father to start one on his deathbed.

The Stanfords were far from intellectuals — Leland Stanford was known for using his library as a place to nap — but they followed through and opened Leland Stanford Junior University to men and women in 1891. Two years later, Leland Stanford died. From that point on until Jane Stanford’s death in 1905, the university was hers.

“She commissioned the statue of her family; she built the arch and church. She dedicated the church to Leland Stanford — ‘my husband,’” writes White. Every part of the university from its design to its educational standards reflected back on its benefactress.

“Jane Stanford regarded a classical education as useless and cruel,” writes White. “Graduates of Harvard and Yale, she claimed, were of benefit to no one, including themselves.” Her university would prepare students for their “usefulness in life” as well as the education “of the soul as well as the mind.”

She even successfully combated a legal challenge to the Stanford estate that put university funds in jeopardy. As the wife of the school’s president and a future murderer suspect would later say, Stanford would have “given her life, if necessary, to save the university.”

An apt statement if there ever was one.

The first sign of something amiss came on Jan. 14, 1905.

Jane Stanford went to bed early in one of the 19 bedrooms of her 41,000-square-foot mansion in San Francisco. She was reportedly the wealthiest of all her moneyed neighbors.

Stanford drank from a bottle of Poland Spring Water, which claimed to cure all manners of nervous illnesses and diseases. When Stanford took a sip, she vomited. The water was bitter. She called out for help and a maid named Elizabeth Richmond came. Her personal secretary, Bertha Berner, who slept on the floor above Stanford, followed.

Stanford wretched and spasmed that night, but pulled through. The next day she sent the bottle away to be tested for poison. It came back positive for strychnine — in a readily available and highly bitter form used as rat poison.

This was bewildering to Stanford.

“I did not think anyone wished to hurt me. What would it benefit anyone?”

The reality was that she had made many enemies. Her maid had recently threatened to quit over mistreatment. Another staff member, Ah Wong, held a grudge because Stanford owed him money.

And then there was her personal secretary. Berner had worked with Stanford since the death of Leland Stanford Jr. and the two were close. Stanford considered her relationship with Berner to be “one that cannot be bought, it is God-giving.”

In fact, Berner had nearly walked away from the job several times after quarreling with her boss; one regular source of strife was that Stanford would often not allow Berner to visit her ailing mother. Other arguments involved men. Berner, a young, attractive woman in her thirties had many admirers and an active social life — too active for Stanford’s old-fashioned tastes. When Stanford insisted that Berner live with her in her Nob Hill mansion, it made “her relationship with Mrs. Stanford even more claustrophobic.”

These were just the people under her roof. Others included a “manservant” named Albert Beverly who had traveled with Stanford until he was cut loose for inflating his bills and skimming off the money for himself.

And then there was the friction between Stanford and the university’s president, David Starr Jordan, who disagreed with Stanford on almost everything about the school. Jordan hated the fact that he owed his job to a dead child. He also knew about Stanford’s secret interest in spiritualism, a practice of communing with the dead.

But the thing he hated most was having to follow the orders of (in his words) “one aged woman.”

“She controlled the endowment, the school’s growth, its construction, and its priorities,” writes White. She put her finger on scale on almost every matter pertaining to the day-to-day running of the university: Staffing, coeducation (she was not in favor of educating women with men), even petty things, like the installation of doorstops in the chemistry building.

“Jane Stanford wanted to be loved and admired, but she needed to be obeyed. Obedience was the condition of working for her,” writes White. Jordan was not obsequious enough for Stanford — and he knew his head was on the chopping block.

Despite the long list of possible leads, the San Francisco Police Department was as flummoxed by the poisoning as Stanford was. Berner was cleared of any wrongdoing and the maid Elizabeth Richmond was fired. No arrests were made.

Jane Stanford wanted this scandal to disappear as much as the college and the police department did.

But the story doesn’t end there.

A little over a month later, Stanford died in Hawaii with Bertha Berner by her side.

They were in Hawaii on their way to Japan. Berner, whose mother was seriously ill, did not want to go. “She was not eager to be dragged off to Asia in the company of an imperious and rich woman,” writes White.

Before they left San Francisco, Berner visited a pharmacy and bought three ounces of bicarbonate soda, a treatment for indigestion that Stanford often used.

In Honolulu on Feb. 28, 1905, Stanford had a pleasant picnic before retiring to her room to lie down. She requested the bicarbonate soda, which Berner brought to her. Later she called Berner to her room. “I am so sick,” she said, wracked with spasms. Berner called for a doctor.

White describes the classic symptoms of strychnine poisoning: “Jane Stanford could not swallow. Her jaws were set . . . Spasms overcame her.”

“This is a horrible way to die,” Stanford said before she stopped breathing. When she did, her body went rigid and the soles of her feet turned inward with the insteps arched.

The Hawaii police department, physician and chemist announced that Stanford had been poisoned — this time with a more potent form of strychnine that could only be purchased at a pharmacy.

The press had a field day with the death — producing lurid front pages of the various murder suspects and even floating the idea of suicide thanks to her interest in spiritualism.

‘Jane Stanford wanted to be loved and admired, but she needed to be obeyed. Obedience was the condition of working for her.’ Author and veteran historian Richard White

Meanwhile, the Hawaii side of the investigation continued. They discovered that Berner would receive $15,000 from Stanford’s will. Berner also had a relationship — likely romantic — with manservant Albert Beverly, who had been fired for getting kickbacks that Berner also got a piece of.

But powerful people didn’t want the charges to stick. No one in the administration wanted the University’s dirty laundry aired. University president Jordan became the face of the counter-narrative that Stanford died of “natural causes.” Jordan introduced his own physician who produced “evidence” that showed that Stanford likely died from “angina pectoris,” or overeating. The considerable gas from overeating at lunch “would have created pressure on the heart,” the physician argued with a straight face.

Berner’s account changed, too. Instead of rigid, Stanford was now slumped over. She “passed away peacefully,” Berner said.

Despite a coroner’s report that found poison in her system, Jordan announced that she died from “advanced age, the unaccustomed exertion, a surfeit of unsuitable food, and the unusual exposure of the picnic party.” Detectives dropped the case, as an investigation “would not benefit the estate, the university, or the San Francisco police,” who would be ridiculed for their mishandling of the first poisoning and overshadowed by the inexperienced Hawaiian police.

Jordan worked at Leland Stanford Jr. University for 11 more years. And although a cloud of suspicion hung around Berner, she lived comfortably in Menlo Park thanks to the $15,000 Stanford inheritance. In 1935, Stanford University published Berner’s story called “Mrs. Leland Stanford: An Intimate Account.” The book is riddled with inaccuracies, “wrong in almost every detail” of Stanford’s death, and became key to White’s case against her.

“Berner’s lies and omissions did not spring from forgetfulness,” Write writes. Particularly, Berner’s omission of the pharmacy stop was particularly “critical to the mystery,” White writes.

“Two poisonings, two doses of strychnine, Berner the only person present both times, plus her purchase of the bicarbonate that later contained the poison: all this spells trouble for Bertha Berner,” he writes. This along with their rocky relationship led White to conclude: “I think she was a murderer, but up until the moment of the murder, I can’t help sympathizing with her.”

Along the way, White discovered an unexplored lead: Palo Alto pharmacist PJ Schwab who sold her the bicarbonate soda. Schwab, who had been accused of another financial crime, was located close to Berner’s mother’s house. Berner and Schwab both spoke German and were linked romantically. “He becomes for me the key to the whole mystery. Insert him in the narrative and things start to click into place. He worked in one of the Palo Alto pharmacies and was friendly with Berner. Accused of embezzlement, he was clearly a man willing to take chances and he could have gotten her the poison without leaving a record.”

Now that we can track the murder weapon to Berner is the case closed? Did she act alone?

Not exactly.

White believes that the university’s president was involved — he didn’t poison Stanford, but instead was an “accessory after the fact.”

Jordan convinced Berner to change her description of Stanford’s death to help suit his aims. “Jordan saved Berner because he had to in order to save himself, the will, the trust documents, and ultimately the university,” writes White.

“In an age of surreal conspiracy theories, it is a reminder that conspiracies can be quite real.”

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Fearful that someone was trying to murder her, Jane Stanford, a 76-year-old widow, sailed for Honolulu several weeks later with two trusted employees. At the Moana Hotel, on the night of Feb. 28 ...

An award-winning historian and MacArthur and Guggenheim fellow, White became intrigued by the unsolved mystery of the death of Jane Stanford (1828-1905), who, with her husband, railroad magnate Leland Stanford, founded a university to memorialize their dead son. When Jane died suddenly in Honolulu, witness statements and an autopsy indicated ...