- Recent Posts

September 14th, 2016

Are human rights really ‘universal, inalienable, and indivisible’.

4 comments | 165 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

By Leila Nasr*

Following centuries of ongoing revision, repetition and reconceptualisation, international human rights theory and practice continues to grapple with three integral concepts: universality, inalienability, and indivisibility. These concepts are perceived as being essential to its continued validity, yet themselves also embody human rights’ most pressing critiques.

Human Rights as Universal

Universal human rights theory holds that human rights apply to everyone simply by virtue of their being human. The most obvious challenge to the universality factor comes from ‘cultural relativism’, which maintains that universal human rights are neo-imperialistic and culturally hegemonic . While this perspective may be tempting, the relativist argument encompasses a debilitating self-contradiction; by postulating that the only sources of moral validity are individual cultures themselves, one is precluded from making any consistent moral judgements. Further, the cultural relativist in fact makes a universalist judgement in arguing that ‘tolerance’ is the ultimate good to be respected above all. Hence, it is a naturally self-refuting theory that engages universalism in its own rejection of the concept. In a practical sense, the cultural relativist position is foundationally incompatible with human rights, as human rights themselves could not exist if they were stripped of common moral judgement.

And yet, the question remains: even if human rights must be universal in order to remain coherent, what should we do when faced with practices or cultures with which ‘our’ version of human rights clashes? Should we stand idly by when atrocities are committed? Surely not. While universal human rights should not be geographically or culturally ‘flexible’ (so as not to undercut their entire purpose), we must see the continuum of rights and culture as relational, not exclusive.

Along this vein, some have argued that we actually need to see human rights as a culture in and of itself – a collective learning about what is in the best interests of humans around the world. This is because, as cultures are non-homogenous and inherently malleable, so too must be their conceptualisations of human rights. Essentially, human rights must be able to absorb cultural difference.

Further still, other commentators have taken issue with the question itself, noting that dichotomised and uncompromising questions over whether human rights should be universal or not actually tend to “arbitrate the correct form of human existence” . In this way, the ability of human agency to integrate, move between and even override cultures is often overlooked. Instead, he argues that the best way forward is for people remain aware of alternative value systems to be able to freely move in and out of them as per their preference. While this may be seen as too liberal or individualistic (as is a common critique of ‘western’ human rights), it best gets to the core of what the purpose of human rights ought to return to: the human.

Human Rights as Inalienable

By definition, inalienability involves the “ inability of something to be taken from or given away by the possessor ”. While the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence , the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man , and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights repeatedly affirmed that rights were inalienable, it remains today that very few can agree on the meaning of this.

Early philosophers and scholars such as Locke , Mason and Lilburne spoke of natural rights in terms of inherentness, natality and inability to be surrendered, helping later thinkers better conceptualise the core of inalienability by asking who the ‘human’ is in human rights.

Constant debate on this topic has brought out the best and worst in more recent philosophers. For example, one scholar notes that one must contribute to both self and society in an autonomous capacity in order to be a rights-bearing person. He thus doubts whether rights could possibly apply to infants, the “ severely mentally retarded ”, or people in irreversible comas . Thankfully, others have stepped away from crude biological distinctions to conceptually consider the multiplicity of ways in which one might be considered ‘unhuman’ such as through heavily gendered and animal-human power dichotomies [1] . In such cases, victims are often stripped of their personhood and basic rights, revealing the alienability of rights in practice.

Along this vein, Hannah Arendt articulated one of the most timeless perspectives on inalienability on the backdrop of the Holocaust. Noting the lack of tangible access to rights experiences by refugees by virtue of their statelessness, Arendt concluded that the only true right was ‘the right to have rights’ in the sense that modern rights had become linked inextricably to the emancipated national state. Of course, important critiques have been lodged against Arendt, such as that of Jacques Rancière , who finds that humans can never be entirely depoliticised and devoid of rights (even when stateless) as they are inherently political beings by the mere fact of birth. However, while somewhat convincing, Rancière’s critique should easily be dismissed as far too abstract to be of great use in the face of the severe and ultimately tangible human rights violations occurring today.

Given today’s challenges of displacement and statelessness, it therefore seems more helpful to eschew abstract reasoning surrounding inalienability and acknowledge that rights are inseparable from statehood and citizenship in the international human rights system. As Arendt reasoned, “ inalienability has turned out to be unenforceable ”.

Human Rights as Indivisible

Turning to indivisibility, this principle maintains that the implementation of all rights simultaneously is necessary for the full functioning of the human rights system. Beyond discussions of violations, indivisibility is equally the idea that no human right can be fully implemented or realised without fully realising all other rights. Those who fall within the indivisibility camp reason that the enforcement of human rights is arbitrary and incomplete without a commitment to indivisibility, and that anything less than simultaneous implementation of all human rights may fuel dangerous rights prioritisations by governments (i.e. emphasising first or second generation rights while neglecting third generation ones will mean that all rights values suffer).

Issues surrounding the prioritisation and partial fulfilment of human rights are at the core of the indivisibility question. Here, Nickel makes a number of strong arguments against indivisibility by distinguishing the concept from interdependence. For example, an arm and leg are not mutually indispensable (indivisible) because one can function without the other. While they may be interdependent to some extent, they are not indivisible. Conversely, a heart and brain cannot function irrespective of each other, thus making them indivisible by definition. Such is the distinction we must make with human rights, too.

It isn’t necessary for every single right to be fully realised in order for the others to mean anything at all. If this were not the case, it may be terrible news for developing countries; rather, such countries do not automatically enter into conflict with the principle of indivisibility if they prioritise some rights over others along a given timeline in light of available resources. This line of thought is an important critique of others, such as Donnelly , who insists on the centrality of system-wide indivisibility, and whose argument fails to appreciate this indivisibility-interdependency distinction.

It is therefore apparent that some of the most widely accepted and central tenants of human rights – universality, inalienability, and indivisibility – emerge as highly contentious upon close inspection. Yet, rather than undercutting the entire concept of human rights, these critiques simply remind us to continually revaluate our assumptions of rights to make them ever more inclusive and ever more tangible to those who remain on the outside, looking in.

[1] Rorty uses the example of the dehumanization of Bosnian Muslims at the hands of Serbian soldiers during the Bosnian war. He explains that this reduced Bosnian Muslim to an ‘animal-like’, or non-human status relative to his/her oppressor, thus stripping the victim of any relevance in discussions on ‘human’ rights.

*Leila Nasr is the Lead Editor of the LSE Human Rights Blog. She can be reached at [email protected].

About the author

In China human rights are not universal because the leaders of the government do not consider all of their fellow citizens as equally fully educated or accomplished human beings.

Does the human rights achieve its intentional peace

Thanks for this literaly I am desperately looking for this topic

1933 film Gabriel In The White House is a must watch on this topic and many others, as it is 100% relevant when discussion 2020 United States and global relationships.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

Rights, exceptions, and the spirit of human rights

June 8th, 2014, international refugee law: definitions and limitations of the 1951 refugee convention, february 8th, 2016, no monkeying around: animals can and will have human rights, october 9th, 2014.

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Human Rights: Samples in 500 and 1500

- Updated on

- Jun 20, 2024

Essay writing is an integral part of the school curriculum and various academic and competitive exams like IELTS , TOEFL , SAT , UPSC , etc. It is designed to test your command of the English language and how well you can gather your thoughts and present them in a structure with a flow. To master your ability to write an essay, you must read as much as possible and practise on any given topic. This blog brings you a detailed guide on how to write an essay on Human Rights , with useful essay samples on Human rights.

This Blog Includes:

The basic human rights, 200 words essay on human rights, 500 words essay on human rights, 500+ words essay on human rights in india, 1500 words essay on human rights, importance of human rights, essay on human rights pdf, what are human rights.

Human rights mark everyone as free and equal, irrespective of age, gender, caste, creed, religion and nationality. The United Nations adopted human rights in light of the atrocities people faced during the Second World War. On the 10th of December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Its adoption led to the recognition of human rights as the foundation for freedom, justice and peace for every individual. Although it’s not legally binding, most nations have incorporated these human rights into their constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. Human rights safeguard us from discrimination and guarantee that our most basic needs are protected.

Also Read: Essay on Yoga Day

Also Read: Speech on Yoga Day

Before we move on to the essays on human rights, let’s check out the basics of what they are.

Also Read: What are Human Rights?

Also Read: 7 Impactful Human Rights Movies Everyone Must Watch!

Here is a 200-word short sample essay on basic Human Rights.

Human rights are a set of rights given to every human being regardless of their gender, caste, creed, religion, nation, location or economic status. These are said to be moral principles that illustrate certain standards of human behaviour. Protected by law , these rights are applicable everywhere and at any time. Basic human rights include the right to life, right to a fair trial, right to remedy by a competent tribunal, right to liberty and personal security, right to own property, right to education, right of peaceful assembly and association, right to marriage and family, right to nationality and freedom to change it, freedom of speech, freedom from discrimination, freedom from slavery, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of movement, right of opinion and information, right to adequate living standard and freedom from interference with privacy, family, home and correspondence.

Also Read: Law Courses

Check out this 500-word long essay on Human Rights.

Every person has dignity and value. One of the ways that we recognise the fundamental worth of every person is by acknowledging and respecting their human rights. Human rights are a set of principles concerned with equality and fairness. They recognise our freedom to make choices about our lives and develop our potential as human beings. They are about living a life free from fear, harassment or discrimination.

Human rights can broadly be defined as the basic rights that people worldwide have agreed are essential. These include the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom from torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the right to health, education and an adequate standard of living. These human rights are the same for all people everywhere – men and women, young and old, rich and poor, regardless of our background, where we live, what we think or believe. This basic property is what makes human rights’ universal’.

Human rights connect us all through a shared set of rights and responsibilities. People’s ability to enjoy their human rights depends on other people respecting those rights. This means that human rights involve responsibility and duties towards other people and the community. Individuals have a responsibility to ensure that they exercise their rights with consideration for the rights of others. For example, when someone uses their right to freedom of speech, they should do so without interfering with someone else’s right to privacy.

Governments have a particular responsibility to ensure that people can enjoy their rights. They must establish and maintain laws and services that enable people to enjoy a life in which their rights are respected and protected. For example, the right to education says that everyone is entitled to a good education. Therefore, governments must provide good quality education facilities and services to their people. If the government fails to respect or protect their basic human rights, people can take it into account.

Values of tolerance, equality and respect can help reduce friction within society. Putting human rights ideas into practice can help us create the kind of society we want to live in. There has been tremendous growth in how we think about and apply human rights ideas in recent decades. This growth has had many positive results – knowledge about human rights can empower individuals and offer solutions for specific problems.

Human rights are an important part of how people interact with others at all levels of society – in the family, the community, school, workplace, politics and international relations. Therefore, people everywhere must strive to understand what human rights are. When people better understand human rights, it is easier for them to promote justice and the well-being of society.

Also Read: Important Articles in Indian Constitution

Here is a human rights essay focused on India.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It has been rightly proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Created with certain unalienable rights….” Similarly, the Indian Constitution has ensured and enshrined Fundamental rights for all citizens irrespective of caste, creed, religion, colour, sex or nationality. These basic rights, commonly known as human rights, are recognised the world over as basic rights with which every individual is born.

In recognition of human rights, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was made on the 10th of December, 1948. This declaration is the basic instrument of human rights. Even though this declaration has no legal bindings and authority, it forms the basis of all laws on human rights. The necessity of formulating laws to protect human rights is now being felt all over the world. According to social thinkers, the issue of human rights became very important after World War II concluded. It is important for social stability both at the national and international levels. Wherever there is a breach of human rights, there is conflict at one level or the other.

Given the increasing importance of the subject, it becomes necessary that educational institutions recognise the subject of human rights as an independent discipline. The course contents and curriculum of the discipline of human rights may vary according to the nature and circumstances of a particular institution. Still, generally, it should include the rights of a child, rights of minorities, rights of the needy and the disabled, right to live, convention on women, trafficking of women and children for sexual exploitation etc.

Since the formation of the United Nations , the promotion and protection of human rights have been its main focus. The United Nations has created a wide range of mechanisms for monitoring human rights violations. The conventional mechanisms include treaties and organisations, U.N. special reporters, representatives and experts and working groups. Asian countries like China argue in favour of collective rights. According to Chinese thinkers, European countries lay stress upon individual rights and values while Asian countries esteem collective rights and obligations to the family and society as a whole.

With the freedom movement the world over after World War II, the end of colonisation also ended the policy of apartheid and thereby the most aggressive violation of human rights. With the spread of education, women are asserting their rights. Women’s movements play an important role in spreading the message of human rights. They are fighting for their rights and supporting the struggle for human rights of other weaker and deprived sections like bonded labour, child labour, landless labour, unemployed persons, Dalits and elderly people.

Unfortunately, violation of human rights continues in most parts of the world. Ethnic cleansing and genocide can still be seen in several parts of the world. Large sections of the world population are deprived of the necessities of life i.e. food, shelter and security of life. Right to minimum basic needs viz. Work, health care, education and shelter are denied to them. These deprivations amount to the negation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Also Read: Human Rights Courses

Check out this detailed 1500-word essay on human rights.

The human right to live and exist, the right to equality, including equality before the law, non-discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth, and equality of opportunity in matters of employment, the right to freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, the right to practice any profession or occupation, the right against exploitation, prohibiting all forms of forced labour, child labour and trafficking in human beings, the right to freedom of conscience, practice and propagation of religion and the right to legal remedies for enforcement of the above are basic human rights. These rights and freedoms are the very foundations of democracy.

Obviously, in a democracy, the people enjoy the maximum number of freedoms and rights. Besides these are political rights, which include the right to contest an election and vote freely for a candidate of one’s choice. Human rights are a benchmark of a developed and civilised society. But rights cannot exist in a vacuum. They have their corresponding duties. Rights and duties are the two aspects of the same coin.

Liberty never means license. Rights presuppose the rule of law, where everyone in the society follows a code of conduct and behaviour for the good of all. It is the sense of duty and tolerance that gives meaning to rights. Rights have their basis in the ‘live and let live’ principle. For example, my right to speech and expression involves my duty to allow others to enjoy the same freedom of speech and expression. Rights and duties are inextricably interlinked and interdependent. A perfect balance is to be maintained between the two. Whenever there is an imbalance, there is chaos.

A sense of tolerance, propriety and adjustment is a must to enjoy rights and freedom. Human life sans basic freedom and rights is meaningless. Freedom is the most precious possession without which life would become intolerable, a mere abject and slavish existence. In this context, Milton’s famous and oft-quoted lines from his Paradise Lost come to mind: “To reign is worth ambition though in hell/Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.”

However, liberty cannot survive without its corresponding obligations and duties. An individual is a part of society in which he enjoys certain rights and freedom only because of the fulfilment of certain duties and obligations towards others. Thus, freedom is based on mutual respect’s rights. A fine balance must be maintained between the two, or there will be anarchy and bloodshed. Therefore, human rights can best be preserved and protected in a society steeped in morality, discipline and social order.

Violation of human rights is most common in totalitarian and despotic states. In the theocratic states, there is much persecution, and violation in the name of religion and the minorities suffer the most. Even in democracies, there is widespread violation and infringement of human rights and freedom. The women, children and the weaker sections of society are victims of these transgressions and violence.

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights’ main concern is to protect and promote human rights and freedom in the world’s nations. In its various sessions held from time to time in Geneva, it adopts various measures to encourage worldwide observations of these basic human rights and freedom. It calls on its member states to furnish information regarding measures that comply with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights whenever there is a complaint of a violation of these rights. In addition, it reviews human rights situations in various countries and initiates remedial measures when required.

The U.N. Commission was much concerned and dismayed at the apartheid being practised in South Africa till recently. The Secretary-General then declared, “The United Nations cannot tolerate apartheid. It is a legalised system of racial discrimination, violating the most basic human rights in South Africa. It contradicts the letter and spirit of the United Nations Charter. That is why over the last forty years, my predecessors and I have urged the Government of South Africa to dismantle it.”

Now, although apartheid is no longer practised in that country, other forms of apartheid are being blatantly practised worldwide. For example, sex apartheid is most rampant. Women are subject to abuse and exploitation. They are not treated equally and get less pay than their male counterparts for the same jobs. In employment, promotions, possession of property etc., they are most discriminated against. Similarly, the rights of children are not observed properly. They are forced to work hard in very dangerous situations, sexually assaulted and exploited, sold and bonded for labour.

The Commission found that religious persecution, torture, summary executions without judicial trials, intolerance, slavery-like practices, kidnapping, political disappearance, etc., are being practised even in the so-called advanced countries and societies. The continued acts of extreme violence, terrorism and extremism in various parts of the world like Pakistan, India, Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Somalia, Algeria, Lebanon, Chile, China, and Myanmar, etc., by the governments, terrorists, religious fundamentalists, and mafia outfits, etc., is a matter of grave concern for the entire human race.

Violation of freedom and rights by terrorist groups backed by states is one of the most difficult problems society faces. For example, Pakistan has been openly collaborating with various terrorist groups, indulging in extreme violence in India and other countries. In this regard the U.N. Human Rights Commission in Geneva adopted a significant resolution, which was co-sponsored by India, focusing on gross violation of human rights perpetrated by state-backed terrorist groups.

The resolution expressed its solidarity with the victims of terrorism and proposed that a U.N. Fund for victims of terrorism be established soon. The Indian delegation recalled that according to the Vienna Declaration, terrorism is nothing but the destruction of human rights. It shows total disregard for the lives of innocent men, women and children. The delegation further argued that terrorism cannot be treated as a mere crime because it is systematic and widespread in its killing of civilians.

Violation of human rights, whether by states, terrorists, separatist groups, armed fundamentalists or extremists, is condemnable. Regardless of the motivation, such acts should be condemned categorically in all forms and manifestations, wherever and by whomever they are committed, as acts of aggression aimed at destroying human rights, fundamental freedom and democracy. The Indian delegation also underlined concerns about the growing connection between terrorist groups and the consequent commission of serious crimes. These include rape, torture, arson, looting, murder, kidnappings, blasts, and extortion, etc.

Violation of human rights and freedom gives rise to alienation, dissatisfaction, frustration and acts of terrorism. Governments run by ambitious and self-seeking people often use repressive measures and find violence and terror an effective means of control. However, state terrorism, violence, and human freedom transgressions are very dangerous strategies. This has been the background of all revolutions in the world. Whenever there is systematic and widespread state persecution and violation of human rights, rebellion and revolution have taken place. The French, American, Russian and Chinese Revolutions are glowing examples of human history.

The first war of India’s Independence in 1857 resulted from long and systematic oppression of the Indian masses. The rapidly increasing discontent, frustration and alienation with British rule gave rise to strong national feelings and demand for political privileges and rights. Ultimately the Indian people, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, made the British leave India, setting the country free and independent.

Human rights and freedom ought to be preserved at all costs. Their curtailment degrades human life. The political needs of a country may reshape Human rights, but they should not be completely distorted. Tyranny, regimentation, etc., are inimical of humanity and should be resisted effectively and united. The sanctity of human values, freedom and rights must be preserved and protected. Human Rights Commissions should be established in all countries to take care of human freedom and rights. In cases of violation of human rights, affected individuals should be properly compensated, and it should be ensured that these do not take place in future.

These commissions can become effective instruments in percolating the sensitivity to human rights down to the lowest levels of governments and administrations. The formation of the National Human Rights Commission in October 1993 in India is commendable and should be followed by other countries.

Also Read: Law Courses in India

Human rights are of utmost importance to seek basic equality and human dignity. Human rights ensure that the basic needs of every human are met. They protect vulnerable groups from discrimination and abuse, allow people to stand up for themselves, and follow any religion without fear and give them the freedom to express their thoughts freely. In addition, they grant people access to basic education and equal work opportunities. Thus implementing these rights is crucial to ensure freedom, peace and safety.

Human Rights Day is annually celebrated on the 10th of December.

Human Rights Day is celebrated to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UNGA in 1948.

Some of the common Human Rights are the right to life and liberty, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom from slavery and torture and the right to work and education.

Popular Essay Topics

We hope our sample essays on Human Rights have given you some great ideas. For more information on such interesting blogs, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Sonal is a creative, enthusiastic writer and editor who has worked extensively for the Study Abroad domain. She splits her time between shooting fun insta reels and learning new tools for content marketing. If she is missing from her desk, you can find her with a group of people cracking silly jokes or petting neighbourhood dogs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Search the United Nations

- Member States

Main Bodies

- Secretary-General

- Secretariat

- Emblem and Flag

- ICJ Statute

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Peace and Security

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Aid

- Sustainable Development and Climate

- International Law

- Global Issues

- Official Languages

- Observances

- Events and News

- Get Involved

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

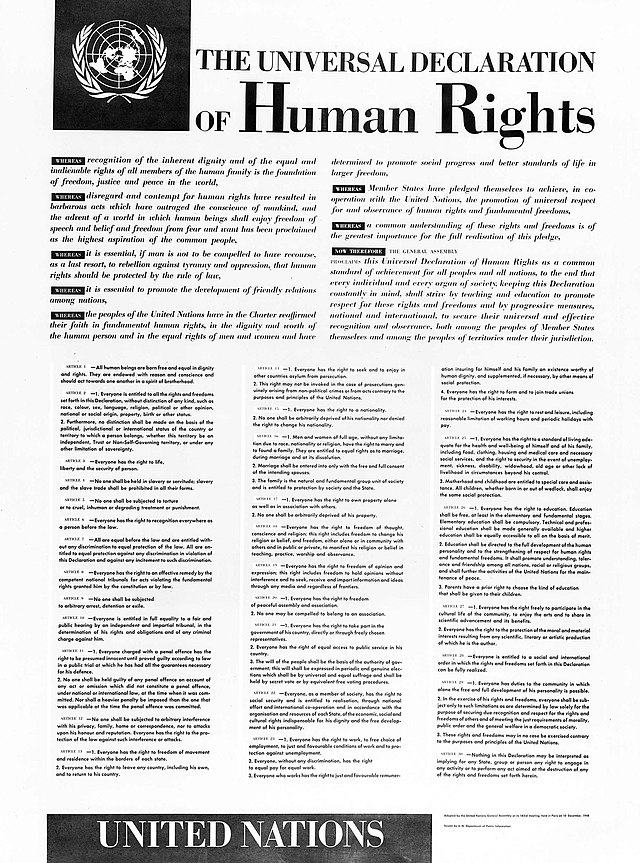

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 ( General Assembly resolution 217 A ) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages . The UDHR is widely recognized as having inspired, and paved the way for, the adoption of more than seventy human rights treaties, applied today on a permanent basis at global and regional levels (all containing references to it in their preambles).

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, therefore,

The General Assembly,

Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

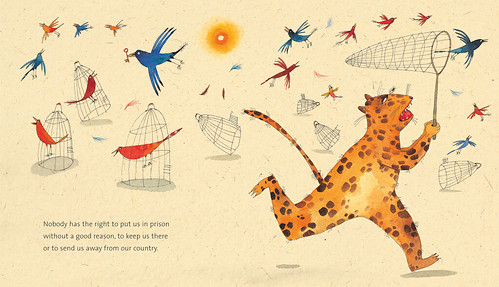

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

- Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

- No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

- Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

- Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

- This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

- Everyone has the right to a nationality.

- No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

- Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

- Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

- The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

- Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

- No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

- No one may be compelled to belong to an association.

- Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

- Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country.

- The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

- Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

- Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

- Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

- Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

- Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

- Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

- Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

- Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

- Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

- Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

- Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

- Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

- In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

- These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

- Text of the Declaration

- History of the Declaration

- Drafters of the Declaration

- The Foundation of International Human Rights Law

- Human Rights Law

2023: UDHR turns 75

What is the Declaration of Human Rights? Narrated by Morgan Freeman.

UN digital ambassador Elyx animates the UDHR

To mark the 75th anniversary of the UDHR in December 2023, the United Nations has partnered once again with French digital artist YAK (Yacine Ait Kaci) – whose illustrated character Elyx is the first digital ambassador of the United Nations – on an animated version of the 30 Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

UDHR Illustrated

Read the Illustrated edition of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UDHR in 80+ languages

Watch and listen to people around the world reading articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in more than 80 languages.

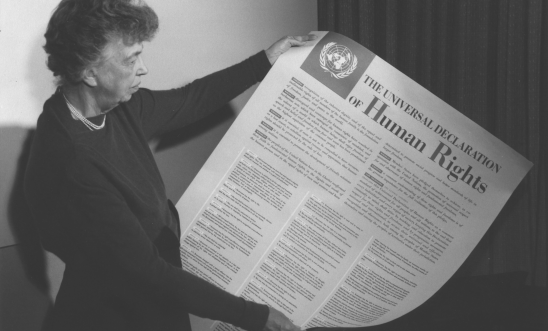

Women Who Shaped the Declaration

Women delegates from various countries played a key role in getting women’s rights included in the Declaration. Hansa Mehta of India (standing above Eleanor Roosevelt) is widely credited with changing the phrase "All men are born free and equal" to "All human beings are born free and equal" in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- Economic and Social Council

- Trusteeship Council

- International Court of Justice

Departments / Offices

- UN System Directory

- UN System Chart

- Global Leadership

- UN Information Centres

Resources / Services

- Emergency information

- Reporting Wrongdoing

- Guidelines for gender-inclusive language

- UN iLibrary

- UN Chronicle

- UN Yearbook

- Publications for sale

- Media Accreditation

- NGO accreditation at ECOSOC

- NGO accreditation at DGC

- Visitors’ services

- Procurement

- Internships

- Academic Impact

- UN Archives

- UN Audiovisual Library

- How to donate to the UN system

- Information on COVID-19 (Coronavirus)

- Africa Renewal

- Ten ways the UN makes a difference

- High-level summits 2023

Key Documents

- Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Statute of the International Court of Justice

- Annual Report of the Secretary-General on the Work of the Organization

News and Media

- Press Releases

- Spokesperson

- Social Media

- The Essential UN

- Awake at Night podcast

Issues / Campaigns

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Our Common Agenda

- The Summit of the Future

- Climate Action

- UN and Sustainability

- Action for Peacekeeping (A4P)

- Global Ceasefire

- Global Crisis Response Group

- Call to Action for Human Rights

- Disability Inclusion Strategy

- Fight Racism

- Hate Speech

- LGBTIQ+ People

- Safety of Journalists

- Rule of Law

- Action to Counter Terrorism

- Victims of Terrorism

- Children and Armed Conflict

- Violence Against Children (SRSG)

- Sexual Violence in Conflict

- Refugees and Migrants

- Action Agenda on Internal Displacement

- Spotlight Initiative

- Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

- Prevention of Genocide and the Responsibility to Protect

- The Rwanda Genocide

- The Holocaust

- The Question of Palestine

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade

- Decolonization

- Messengers of Peace

- Roadmap for Digital Cooperation

- Digital Financing Task Force

- Data Strategy

- Information Integrity

- Countering Disinformation

- UN75: 2020 and Beyond

- Women Rise for All

- Stop the Red Sea Catastrophe

- Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre

The Universality of Human Rights Essay (Critical Writing)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Human’s Rights as the Attribute of Society

The four schools of thoughts: observing the perspectives, natural school: the natural course of events, protest school: opposing the situation, deliberative school: agreeing upon the basics, discourse school: when it is the right time to talk, multiculturalism in different forms, human rights and linguistic diversity, reference list.

In contrast to the other institutions that suggest a single form of the notion existing in the given society, the area of human rights allows to switch the shapes of the very notion of human rights according to the sphere it is applied to. In spite of the fact that the core idea of the human rights remains the same, the form it takes can vary depending on the field of use. The universality of human rights allows them to get into every single part of people’s lives, and this is a subject that needs further exploration.

The way the human rights are interpreted now does not differ from the basic principles set by the founders of democracy. Throughout the centuries, the main idea of human rights remained the same, claiming every single person to have the package of rights that are to be inherent and be an integral part of living a full life of a free man. Set long time ago and representing the range of freedoms that have been proclaimed since the times of the French Revolution, these right still speak of the democracy in motion, demanding the constitutional law and the recognition of a man’s liberty. The situation has not changed much since then, the established rights for life, education, voting and freedom of speech, remain the same.

However, there have been some amendments that presupposed certain improvements, but the basics were left untouched. Nowadays, almost every country can claim that it suggests a full range of the necessary rights and freedoms to its citizens. The democracy principles spread all around the world, and the modern society seems to have all the attributes to be called democratic for recognizing people’s right and freedoms in full. However, it is still curious how the law that outlines the most important points of human rights can convey the idea, and the way this idea can switch its shape as it transgresses from one sphere of analytical and philosophical thinking into another one.

Dembour (2006) defines human rights as the most obvious things that should actually be taken for granted, without clarifying them in such a detailed manner in the set of laws, “One claims a human right in the hope of ultimately creating a society in which such claims will be no longer necessary” (p. 248). The existence of the four schools of human right can explain the fact of these rights switching their shape so suddenly and with such a scale. There four schools consider human rights in absolutely different light. The ideas of different scholars may be considered from the point of view of those four schools of thought. A lot of scholars dwelling upon human rights in the relation to multiculturalism and language refered themselves to one of the Dembour’s schools.

One of the most well-known schools is probably the natural school that considers human rights as they are given, in plain. Presupposing that human rights are something that one has been granted since the day of birth, the followers of this school suggest that the subject under discussion can be valued from the point of view of the plain nature. Eriksen (1996) supports this idea dwelling upon the fact that different nations can exist together on the basis of understanding this idea. Taylor (1994) also supports this idea claiming people with different understanding of human rights may respect each other and perceive them as they are.

The idea that this philosophy conveys is that a person’s rights are the incorporation of the laws of nature and it presupposes that people should act according to their inner understanding of their rights and freedoms. This theory is close to idealism, which is supported by Donelly (2003) who is sure that people have rights “simply because one is a human being” (p. 10).

As opposed to natural school of thought, protest school of thought believes that human rights cannot be considered as a universal notion because they are limited to such concepts as morality, dignity, and moral integrity (Dembour, 2006, p. 236). In particular, the supporters of this concept find some political and intellectual inferences related to human rights. They believe that universality of human rights fails to consider the dignity and individuality of each person. More importantly, the theory suggests that human rights impose a kind of responsibility on each individual.

If to consider human freedom as one of inherent components of human rights, one should be aware of the fact that all freedoms enjoyed by individuals should be deserved first. Indeed, a person takes all existing freedoms for granted finding it unnecessary to fight for them. They agree with the assumption that freedom is an innate right of humans (Denbour, 2006, p. 237). This position also reveals that illusionary possession of the fundamental freedoms should be protected by law.

This school of thoughts can be interpreted through visions and outlooks of Varennes (2007). In particular, his point of view is narrowed to the idea that language right should protected on equal basis with human rights because it reveals their identity and responsibility for their culture and country. Hence, Varennes (2007) states, “…the use of a language in private activities can be in breach of existing international human rights such as the rights to private and family right” (p. 117).

Drawing the line between the protest scholars, language right should be protected by law as well. Such a position explains Varennes’ affiliation to this theoretical framework. The problem of linguistic justice is also considered by Patten and Kymlicka (2003) and Wei (2009) who believe that should be linguistic justice because it is an inherent component of human rights.

As compared with natural and protest theoretical framework whose primary concerns are based on a strong belief in human rights, deliberate school of thought are fully loyal to this concept. They conceive human rights as an idealistic conception that exists regardless of human experience. According to this school, “human rights are thus no more than legal and political standards; they not moral, and certainly not religious, standards” (Dembour, 2006, p. 248). Therefore, the limited perception of human rights impels the scholars to believe that this phenomenon is nothing else but adjudication.

While analyzing different ideas and positions, Dembour (2006) concludes that deliberate theorists find human rights beyond political and legal dependence. Rather, they compare them with religion, stating that it is a universal notion existing outside the context of morality, law and politics. Due to the fact that human rights are perceived as something secular, deliberate school of thought subjects this conception to idolatry.

Following the main concepts of deliberate school, Aikman (1995) provides his own vision of linguistic diversity and cultural maintenance that should be preserved irrespective of laws and politics because it is more connected with social needs and socio-cultural environment in the country. More importantly, Boumann (1999) provides the separatist vision of linguistic rights in correlation of his position to its universality. In particular, the scholar beliefs that multiculturalism and human right should be reevaluated and be more connected with ethnic and religious identity, but not political and legal perspectives.

Although Biseth (2008) seems to be more radical in his vision of multiculturalism, the scholar also represents deliberate school of though believing that linguistic diversity is inevitable due to diversity in culture and cultural heritage. In particular, Biseth (2008) stands for equality and universality of human right with regard to linguistic right, which should be perceived as something integral and inherent to a human. In general all the above-presented scholars agree with the necessity to perceive linguistic right as something independent from politics and law.

Dwelling upon discourse school of thought and relating it to the human rights, it is possible to states that Dembour (2006) defined the scholars who belonged to this school as those who, “not only insist that there is nothing natural about human rights, they also question the fact that human rights are naturally good” (p. 251). The representatives of this school are sure that those human rights exist only because people talk about them. Moreover, Dembour (2006) believes that if the notion of human rights does not exist, so there is nothing to fight for and to protect.

Koenig and Guchteneire (2007) believe that due to high rate of migration and international communication human rights became international and there is nothing to discourse about. It is possible to refer Holmarsdottir (2009) to this school of thought as his ideas are closely connected to the ideas presented by Dembour (2006). Holmarsdottir (2009) is sure that there are no human rights which have been given to people since their birth. Only the government can give people their rights. He writes, “a government is considered as having as exclusive right to make and implement policy in the interest of all the people” (Holmarsdottir, 2009, p. 223).

All these ideas and perspectives may be easily considered from the point of view of multiculturalism and language problem in the concept of human rights.

It is important to remember that different cultures presuppose in some cases absolutely dissimilar norms and rules. In this case, human rights policies are not an exception. But, there is the tendency that many counties live in the multicultural society, so different norms and rules should collaborate and be combined. But, it is impossible to provide in the real society. Aikman (1995) states that many indigenous peoples struggle for the right to use their languages on their territory.

The multiculturalism has entered the society of Harakmbut Amazon people so deeply that these people have to fight for the opportunity to use their native language. It is natural that the countries with the same problems create the Declarations where the status of their country is stated as bicultural and it allows people to use their native language. Thus, indigenous peoples have created the draft of the declaration which allows them to use their traditions and culture in the multicultural society they are made to live in. The text of the draft states that peoples who are influenced by other cultures can “revitalise, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, philosophies, writing system and literature” (Aikman, 1995, p. 411).

Baumann (1999) is sure that people can never understand the main idea of multiculturalism and can still see the problem there until they do not rethink the problem. According to Baumann (1999), the multiculturalism should become global “just as environmentalism and feminism need to be global to succeed” (p. 32). Thus, human rights will be followed and there will not be a problem if the whole world is involved into multicultural society. The author also states that the problems in the society are mostly solved by the civil rights which exclude foreigners. Is not it the violation of the principles of the multiculturalism (Baumann, 1999)?

The problems in the multicultural society became extremely debatable. The appearance of different politics within the problem makes it possible to become politically neutral for most people. Thus, the politics of equal dignity is based on the principle that people on the whole Planet should be equally respected. Thus, their human rights should be respected as well. This politics creates the universal human potential. The main idea of this potential is that people should be respected, no matter what ethnical group they belong to or what language they speak. Still, the problem of the relations between people in the multicultural society remains unsolved (Taylor, 1994, p. 41).

While many people dwell upon the importance of the multiculturalism and the culture globalization, Halla (2009) states that globalization of culture has absolutely negative impact on the whole society. It is important to understand that the multiculturalism in the whole world eliminates the uniqueness of the peoples and their cultures. Halla (2009) is sure that multiculturalism reduces people from using their rights to live in the country they were born in. It is really important for elite to maintain multiculturalism in the world society as in this case people are required to buy the western products and goods. On the one hand, the culture globalization has a positive effect (especially in education and in the right of choice). On the other hand, the problem is extremely sharp for small peoples who cannot resist cultural globalization and lose their unique qualities (Halla, 2009).

Dwelling upon multiculturalism and human rights, Eriksen (1996) uses the example of Mauritius. The religious, language and cultural diversity of this community is rather varied and difficult, still people in Mauritius are given an absolute freedom of which religion they may follow (there are four main religions on the island, three of which are subdivided into numerous sects), which subjects to study at school (most core subjects are options, so students are not obligated to learn the things they do not want or do not like due to their cultural or religious preferences), and which language they want to speak. Even though that the main language on the island is English, the cultural languages are spoken and supported by the society (Eriksen, 1996). Thus, the main idea of the said is that multiculturalism which does not violate human rights is the multiculturalism where the peoples with different cultures live on the same territory, but there are no quarrels and problems in the cultural question.

There are a lot of different forms how multiculturalism may be considered. Still, many people understand this notion as the impact of one culture under another one when the smaller should resists. This understanding is correct as in most cases it is so. Here is one dominant culture which influences the whole society and other nationalities should submit to the requirements provided by other nations. This form of multiculturalism is wrong. People should not be submitted to somebody only because they are stronger or are considered to be more developed. Culture is not an economy or politics, this human facility should not be measured with anything. Thus, if some people have a culture, it should be protected and no one should violate the rights of others calling this multiculturalism.

Still, there is a better form of multiculturalism which is practiced on small islands all over the world. This form of multiculturalism is like a rainbow or a salad, as opposed by Eriksen (1996). The ingredients and elements are in one and the same ‘society’, they are gathered together, but they do not try to take up each other. Living on one and the same territory people do not impose their rights and cultures on others, they just learn to live together, and this is the form of the multiculturalism which should be spread worldwide, when human rights are not violated and human uniqueness is not spoiled.

Without any doubts, the idea of human rights has already touched upon numerous aspects of life: people want to know more about their rights, they want to take as many steps as possible to improve the conditions under which they have to live, and, finally, they want to understand the main idea of their rights and define possibilities. The idea of human rights and its connection to linguistic diversity seems to be a powerful aspect to evaluate the chosen theme from. There is a certain link between language rights and human rights (Varennes, 2007).

It is usually wrong to believe that only some groups of people may have their language rights because any person has his/her own language rights, and those people whose rights are violated by the government in some way have to re-evaluate their status and their possibilities. There were many attempts to advocate language rights, and one of them was supported by the political movement in the middle of the 1960s (Wei, 2000). Still, the question concerning rights remains to be open, and a variety of discussions may take place.

Nowadays, the idea of linguistic diversity is narrowed to several languages which are defined as those with some kind of future. In fact, the power of linguistic diversity is great indeed as any language is considered to be a factor that may contribute to cultural diversity that influences the development of human rights. Linguistic diversity seems to be a serious challenge for the vast majority of democratic polities because language is usually regarded as “the most fundamental tool of communication”; this is why even if the “minorities are not in themselves bearers of collective rights, the transnational legal discourse of human rights does de-legitimize strong policies of language homogenization and clearly obliges states to respect and promote linguistic diversity” (Koenig & Guchteneire, 2007, p. 10).

So, linguistic diversity is the source of controversies, which may be developed on the political background, influence considerably human rights in various contexts, and predetermine “the stability and sustainability of a wide range of political communities” (Patten & Kymlicka, 2003, p. 3). Still, this aspect has to be regulated accordingly because it has a huge impact on the development of the relations between different people. For example, a number of politically motivated conflicts are connected with language rights which have to be established separately from other human rights.

And even the increase of inequalities depends on language rights and prevents the development of appropriate society. In case language rights and other aspects which are based on linguistic diversity do not move in accordance with people’s demands and interests, there is a threat that people can make use of their own assumptions about language policies (Holmarsdottir, 2009), and these assumptions can hardly be correct. However, Biseth (2009) admits that diversity in languages as well as competence in these languages plays an important role in social development, this is why they cannot be neglected but elaborated.

People suffer from a variety of limitations which are based on human inabilities to use their own languages but the necessity to use the official language. Such restrictions lead to people’s inabilities to get appropriate education in accordance with their interests, to participate in political life of the country a person lives in, and even to ask for justice when it is really necessary.

This is why another important aspect that has to be evaluated is how the chosen human rights perspective may influence the promotion of linguistic justice and diversity that is widely spread nowadays. Some researchers say that linguistic rights have to become one of the basic types of the existed human rights. Speakers, who use a dominant language, and linguistic majorities find the existed linguistic human rights an excellent opportunity to express their ideas and their demands. Still, there are many people, the representatives of linguistic minorities, who cannot support the idea of linguistic human rights because only the smallest part of the existed languages has the official status.

It happens that some individuals undergo unfair attitude or are suppressed by the majorities because of the language they use. Taking into consideration this fact, it is possible to say that wrongly introduced linguistic human rights may negatively influence other human rights including the political representation. The outcome of such discontents and misunderstanding is as follows: people are in need of appropriate improvements and formulations which may consider cultural heritage, educational demands, and freedom of speech.

In general, the evaluation of the human rights perspective on linguistic diversity helps to comprehend that there are many weak points in the already existed system that influences and manages a human life. People are eager to create some rules, requirements, and obligations to follow a particular order and to develop appropriate relations. Still, linguistic diversity continues developing and changing human lives. And the main point is that some researchers and scientists still find this diversity an important aspect of life that cannot be changed, and some people cannot understand the importance of this diversity as it considerably restricts human rights.

In conclusion, the question of human rights is constantly discussed in the modern world. There are different opinions on the problem, some people state that human rights even do not exist as the notion (Dembour, 2006), still, most people assure that human rights exist as the duties of the society (Donnelly, 2003). Moreover, the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (UN, 1993) dwells upon the very notion of human rights and the system of international human rights which relate people to the multicultural society where those rights should be followed. The problem stands sharp in the education where students, desiring to study their own languages have to learn others. Moreover, the impact of the dominant language is rather damaging on the others who exists in one society.

It is really important to remember that living in the multicultural society and trying to adopt the cultures and traditions of other dominant nations, many peoples ruin their uniqueness, they become ordinary, forgetting their roots. As the same time, the process of culture globalization leads people to the universality of human rights. This step may be significant in preventing human rights violation in the society.

Aikman, S. (1995). Language, literacy and bilingual education. An Amazon people’s strategies for cultural maintenance. International Journal of Educational Development, 15 (4), 411-422.

Baumann, G. (1999). The Multicultural Riddle: Rethinking National, Ethnic, and Religious Identities . New York: Routledge. Web.

Biseth, H. (2009). Multilingualism and Education for Democracy. International Review of Education, 55 (1), 5-20.

Dembour, M. B. (2006). Who believes in human rights? Reflections on the European Convention . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donnelly, J. (2003). Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Eriksen, T. H. (1996). Multiculturalism, Individualism and Human rights: Romanticism:The Enlightenment and Lesson from Mauritius. In R.Wilson (ed. ) Human rights, Culture and Context, Anthropological Perspective (pp. 49-69). London, Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press 47-17.

Holmarsdottir, H. (2009). A tale of two countries: language policy in Namibia and South Africa. In H. Holmarsdottir and M. O’Dowd (Eds.). Nordic Voices: Teaching and Researching Comparative and international Education in the Nordic Countries (pp. 221-238). Amsterdam: Sense.

Koenig, M., & Guchteneire, P. d. (2007). Political Governance and Cultural Diversity. In M. Koenig & P. d. Guchteneire (Eds.), Democracy and Human Rights in Multicultural Societies (pp. 3-17). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Patten, A., & Kymlicka, W. (2003). Introduction: Language rights and political theory: Context, issues and approaches. In W. Kymlicka & A. Patten (Eds.), Language rights and political theory (pp. 1-51). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, C. (1994). The Politics of Recognition. In C. Taylor & A. Gutmann (Eds.), Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition (pp. 25-73). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

UN (1993). Vienna Declaration and programme of Action . Web.

Varennes, F. d. (2007). Language Rights as an Integral Part of Human Rights – A Legal Perspective. In M. Koenig & P. d. Guchteneire (Eds.), Democracy and Human Rights in Multicultural Societies (pp. 3-17). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Wei, Li (2000). Dimensions of bilingualism. In Li Wei (Ed.), The Bilingualism Reader (pp. 3-25). London: Routledge.

- Abortion in the Middle East

- The Evolution of Human Rights: France vs. America

- Researching of Racial Appearance in Media

- Challenges for Universal Human Rights

- Social Change Strategies: The Discussion

- Human Rights and Resistance of South Asia

- Cyber Practices and Moral Evaluation

- Domestic Legal Traditions vs. Human Rights: A Global Perspective

- The Issues of Human Rights

- International Justice for Human Rights Violation

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, July 24). The Universality of Human Rights. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universality-of-human-rights/

"The Universality of Human Rights." IvyPanda , 24 July 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/the-universality-of-human-rights/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'The Universality of Human Rights'. 24 July.

IvyPanda . 2020. "The Universality of Human Rights." July 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universality-of-human-rights/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Universality of Human Rights." July 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universality-of-human-rights/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Universality of Human Rights." July 24, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-universality-of-human-rights/.

Accessibility

All popular browsers allow zooming in and out by pressing the Ctrl (Cmd in OS X) and + or - keys. Or alternatively hold down the Ctrl key and scroll up or down with the mouse.

Line height

- Amnesty International UK

What is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

The UDHR is an enduring commitment to prevent the bleakest moments in history from happening again.

'The UDHR is living proof that a global vision for human rights is possible, doable, workable.' Agnes Callamard's keynote address to Amnesty International’s 2023 Global Assembly

When was the UDHR created?

The UDHR emerged from the ashes of war and the horrors of the Holocaust. The traumatic events of the Second World War brought home that human rights are not always universally respected. The extermination of almost 17 million people during the Holocaust, including 6 million Jews, horrified the entire world. After the war, governments worldwide made a concerted effort to foster international peace and prevent conflict. This resulted in the establishment of the United Nations in June 1945.

On 10 December 1948 , the General Assembly of the United Nations announced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) - 30 rights and freedoms that belong to all of us. Seven decades on and the rights they included continue to form the basis for all international human rights law .

On 10 December 2023 we are celebrating the UDHR's 75th anniversary, reflecting on the enduring power of these principles to inspire positive change worldwide.

Who created the UDHR?

In 1948, representatives from the 50 member states of the United Nations came together, with Eleanor Roosevelt (First Lady of the United States 1933-1945) chairing the Human Rights Commission, to devise a list of all the human rights that everybody across the world should enjoy. Her famous 1958 speech captures why human rights are for every one of us, in all parts of our daily lives :

'Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home - so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.' Eleanor Roosevelt, 1958, during a speech at the United Nations called ‘Where Do Human Rights Begin?’

Hansa Mehta was the delegate of India, and the only other female delegate to the Commission. She is credited with changing the phrase "All men are born free and equal" to "All human beings are born free and equal" in the Declaration.

Various delegations contributed to the writing of the Declaration, ensuring the UDHR promised human rights for all, without distinction. The Egyptian delegate confirmed the universality principle, while women delegates from India, Brazil and the Dominican Republic disrupted the proceedings to ensure the gender equality. Other delegations disrupted the attempts by the Belgium, France and UK delegations to weaken provisions against racial discrimination.

'That’s why we celebrate the UDHR, not because of who wrote it into history, but because of those who used it to disrupt history.' Agnes Callamard's keynote address to Amnesty International’s 2023 Global Assembly

Why is the UDHR important?

The UDHR marked an important shift by daring to say that all human beings are free and equal, regardless of colour, creed or religion. For the first time, a global agreement put human beings, not power politics, at the heart of its agenda . Communities, movements and nations across the world took the UDHR disruptive power to drive forward liberation struggles and demands for equality.

Although it is not legally binding, the protection of the rights and freedoms set out in the Declaration has been incorporated into many national constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. All states have a duty, regardless of their political, economic and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights for everyone without discrimination.

Our human rights in the UK

The UDHR has three principles: universality, indivisibility and interdependency

- Universal : this means it it applies to all people, in all countries around the world. There can be no distinction of any kind: including race, colour, sex, sexual orientation or gender identity, language, religion, political or any other opinion, national or social origin, of birth or any other situation

- Indivisible : this means that tking away one right has a negative impact on all the other rights

- Interdependent : this means that all of the 30 articles in the Declaration are equally important. Nobody can decide that some are more important than others.

A summary of the 30 articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The 30 rights and freedoms set out in the UDHR include the right to asylum , the right to freedom from torture , the right to free speech and the right to education . It includes civil and political rights, like the right to life , liberty , free speech and privacy . It also includes economic, social and cultural rights, like the right to social security , health and education .

Buy this illustrated collection for children

What are the UDHR articles?

Article 1 : We are all born free. We all have our own thoughts and ideas and we should all be treated the same way.

Article 2 : The rights in the UDHR belong to everyone, no matter who we are, where we’re from, or whatever we believe.

Article 3 : We all have the right to life, and to live in freedom and safety.

Article 4 : No one should be held as a slave, and no one has the right to treat anyone else as their slave.

Article 5 : No one has the right to inflict torture, or to subject anyone else to cruel or inhuman treatment.